Abstract

Objective

To clarify the magnitude and nature of the relationship between divorce and risk for alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Method

In a population-based Swedish sample of married individuals (n=942,366), we examined the association between divorce or widowhood and risk for first registration for AUD. AUD was assessed using medical, criminal and pharmacy registries.

Results

Divorce was strongly associated with risk for first AUD onset in both men (HR=5.98, 95% CI, 5.65–6.33) and women (HR=7.29, 6.72–7.91). We estimated the HR for AUD onset given divorce in discordant monozygotic twins to equal 3.45 and 3.62 in men and women, respectively. Divorce was also associated with an AUD recurrence in those with AUD registrations before marriage. Furthermore, widowhood increased risk for AUD in men (HR=3.85, 2.81–5.28) and women (HR=4.10, 2.98–5.64). Among divorced individuals, remarriage was associated with a large decline in AUD in both sexes: males 0.56, 0.62–0.64 and females 0.61, 0.55–0.69. Divorce produced a greater increase in first AUD onset in those with a family history of AUD or with prior externalizing behaviors.

Conclusions

Spousal loss through divorce or bereavement is associated with a large enduring increased AUD risk. This association likely reflects both causal and non-causal processes. That the AUD status of the spouse alters this association highlights the importance of spouse characteristics for the behavioral health consequences of spousal loss. The pronounced elevation in AUD risk following divorce or widowhood, and the protective effect of remarriage against subsequent AUD, speaks to the profound impact of marriage on problematic alcohol use.

In epidemiological samples, divorce is consistently associated with levels of alcohol consumption and risk for alcohol use disorder (AUD) (1–3). Divorced individuals consume more alcohol (4) and in more harmful patterns (5) than married individuals. Compared to married individuals, divorcees are more likely to have a lifetime or last-year AUD diagnosis (1), to engage in alcohol-related risky behaviors (5), and to have higher alcohol-related mortality (6).

However, the causes of the divorce-AUD association are likely complex and remain poorly understood. The association could result from confounding factors including social class, genetic liability, and personality traits which predispose to both AUD (1;7;8) and divorce (9–11). This association could also arise from a causal pathway from AUD –> divorce as suggested by longitudinal studies showing that heavy drinking individuals have an increased risk for divorce (12;13). Finally, a range of prior evidence suggests a causal divorce –> AUD pathway. For example, marriage is associated with a many benefits including spousal monitoring and moderating of one another’s health-related behaviors (14). Divorce prospectively predicts increases in drinking (4;15;16). A recent Swedish longitudinal and co-relative study showed strong protective effects of first marriage on subsequent AUD risk that, based on results from a co-relative design, were likely to be largely causal (17).

In this report, we take a complementary analytic approaches to clarify the nature of the divorce-AUD association. We specifically explore:

Association in a longitudinal cohort design between divorce and subsequent risk for AUD.

Addition to aim 1 of spouse AUD status and key confounding variables.

Co-relative analyses examining differences in risk for AUD in pairs of relatives concordant for marriage and discordant for divorce or timing of divorce.

Fine scale examination of the temporal association, among married individuals, between divorce and first AUD registration.

Association between remarriage after divorce and subsequent risk for AUD.

Application of approaches 1 and 2 to the association between widowhood and risk for AUD. Widowhood provides an important discriminant test for understanding the association between spousal loss and AUD since spousal loss by death is likely to have fewer potential confounds than divorce.

In understanding better the nature of the causal association between divorce and AUD, we hope to inform avenues for prevention or intervention for AUD and problem drinking more broadly (18;19).

METHODS

We linked nationwide Swedish registers via the unique 10-digit identification number assigned at birth or immigration to all Swedish residents. The identification number was replaced by a serial number to ensure anonymity. The details of our sources used to create this dataset are outlined in the appendix.

Sample

We included individuals born in Sweden between 1960 and 1990 who were both married and residing with their spouse, in or after 1990, with no AUD registration prior to marriage. For the co-relative analysis, we identified full-sibling and cousin pairs from the multigeneration Register born within three years of each other, and monozygotic (MZ) twin pairs from the Swedish Twin Register (20).

Measures

For our method of identification of AUD, see the appendix. As a measure for socioeconomic status, we used parents’ highest education, categorized as low (compulsory school), mid (upper secondary school), or high (university). Early externalizing behavior (EB) was defined as registration before age 19 for criminal behavior or drug abuse using previous definitions (21;22). As a measure of familial risk, we assessed whether the individual had one or more parents, full- and half-siblings, or cousins with an AUD registration.

We identified divorce and widowhood by the married status variable in the Total Population Register. Remarriage was defined as first registration of marriage after first registration of divorce or widowhood.

Statistical methods

We utilized a Cox Proportional Hazard model to estimate the risk of AUD as a function of divorce or widowhood. As marital status could change over time, we included the predictor variable as a time dependent covariate and when estimating the association with divorce, we censored at death, death of spouse, remarriage, migration or end of follow- up (year 2008) whichever came first. When modelling the effect of widowhood, we censored if divorce preceded the death of the spouse. In our Cox model, we tested the proportionality assumption – that the change in risk for AUD with versus without divorce is constant over the follow-up period. We adjusted for year of birth, EB, parental education, familial risk of AUD, and AUD in spouse. We further investigated whether AUD in the spouse affected the association with divorce by including their interaction.

Second, we used a co-relative design to estimate the effect of divorce when adjusting for unmeasured familial confounding. MZ twins share 100% of their genes identical by descent and full-siblings and cousins on average 50% and 12.5%, respectively. MZ twins and siblings typically share their rearing environment. In the co-relative analyses each pair is treated as a strata and the HR (hazard ratio) represent the increased risk of divorce given the familial confounding shared within pairs. Only pairs concordant for marriage, and discordant for both divorce and AUD, or the timing of divorce and AUD, contributed to the estimates. We did not have enough such MZ pairs to obtain stable estimates on their own. We therefore built a model where we include MZ twins, full-siblings and cousins, and also added the population, treated as one stratum. By assuming that the parameters in the Cox regression (the log of HRs) depend linearly on the genetic resemblance, we obtained estimates for all relative pairs including MZ twins. We compared the fit of this model to a saturated model including a parameter for each relative group by Akaike’s Information Criteria where a lower number indicates a better balance of explanatory power and parsimony (23).

To visualize how the risk of AUD changes around the year of divorce and widowhood, we plotted the proportion of individuals at risk (not censored) at that time point who had an AUD onset at that time. To make a comparison with the non-divorced (or non-widowed), that group’s time of AUD onset was centered on the mean age of divorce (or widowhood) for the corresponding married population. Given the modest number of observations (especially for widowhood), we “smoothed” the curves by presenting 3 year moving averages to all points except the zero point – the year of divorce or widowhood.

Finally, we tested whether a family history of AUD or a history of EB prior to age 18 modified the impact of divorce on AUD risk using estimates from an Aalen’s Additive regression model (24), adjusted for birth year and parental education.

RESULTS

Divorce

Our main cohort included 942,366 individuals born between 1960 and 1990, and married 1990 or thereafter with no AUD registration prior to marriage (table 1). The average age at marriage was around 30 and AUD onset 8 to 9 years later (table 1). During our follow-up period, 16% of men and 17% of women were divorced, and 1.1% of men and 0.5% of women were registered for AUD. As seen in table 2, using a Cox proportional hazard model with divorce as a time-dependent covariate with birth year as a control variable, divorce was strongly associated with the subsequent onset of AUD in both men (HR=5.98, 95% CI, 5.65–6.33) and women (HR=7.29, 6.72–7.91). Adding three key potential confounders, which on their own substantially predicted AUD risk (low parental education, prior deviant behavior and family history of AUD), produced modest decreases in the observed associations with divorce for men (HR= 5.09, 4.81–5.39) and women (6.31, 5.82–6.86). In both males and females, divorce had a much stronger association with risk for future AUD if the spouse did not have a lifetime history of AUD than if they had such a history: males − 6.05 (5.71–6.41) vs. 2.07 (1.71–2.52); females − 7.88 (7.20–8.62) vs. 2.38 (2.02–2.81).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Divorce and Widowhood in Individuals Born between 1960 and 1990 and Married in or after 1990 with no Alcohol Use Disorder Registration Prior to Marriage

| Divorce | Widowhood | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| Number of individuals | 443,684 | 498,682 | 443,684 | 498,682 |

| Age at marriage, mean (SD) | 30.7 (4.9) | 29.0 (4.8) | 30.7 (4.9) | 29.0 (4.8) |

| Age at AUD, mean (SD) | 38.9 (6.3) | 38.3 (6.5) | 38.9 (6.3) | 38.3 (6.5) |

| Age at divorce/death of spouse, mean (SD) |

35.6 (7.0) | 34.2 (5.8) | 38.2 (5.2) | 36.9 (5.9) |

| Age of spouse at divorce/death, mean (SD) |

34.2 (6.1) | 37.4 (6.8) | 38.1 (6.6) | 42.0 (8.0) |

| Length of marriage before divorce or death of spouse, mean (SD) |

7.0 (4.3) | 7.2 (4.4) | 8.1 (5.2) | 8.3 (5.2) |

| Not divorced/widowed, no AUD | 370,054 (83.40%) |

409,825 (82.20%) |

437,281 (98.56%) |

494,045 (99.07%) |

| Not divorced/widowed, AUD | 3,755 (0.85%) | 1,641 (0.33%) | 5,339 (1.20%) | 2,303 (0.46%) |

| Divorced/Widowed, no AUD | 65,123 (14.68%) | 84,580 (16.94%) | 1,008 (0.23%) | 2,273 (0.46%) |

| Divorced/Widowed, AUD during marriage |

1,601 (0.36%) | 681 (0.14%) | 17 (0.00%) | 19 (0.00%) |

| Divorced/Widowed, AUD after divorce/widowhood |

3,151 (0.71%) | 1,955 (0.39%) | 39 (0.01%) | 42 (0.01%) |

| At least one relative with AUD | 114,618 (25.83%) |

133,664 (26.80%) |

114,618 (25.83%) |

133,664 (26.80%) |

Table 2.

Cox Proportional Hazard Model Estimates of Risk for Alcohol Use Disorder after Divorce in Males and Females

| Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divorce | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Divorce | 5.98 (5.65, 6.33) | 5.09 (4.81, 5.39) | 7.29 (6.72, 7.91) | 6.31 (5.82, 6.86) |

| Birth year | 1.01 (1.01, 1.02) | 1.01 (1.01, 1.02) | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) | 1.03 (1.02, 1.03) |

| Parental education (mid vs. low) |

0.86 (0.81, 0.91) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.07) | ||

| Parental education (high vs. low) |

0.72 (0.68, 0.77) | 0.78 (0.71, 0.86) | ||

| Early Deviant Behavior | 2.87 (2.69, 3.05) | 3.47 (3.04, 3.96) | ||

| AUD in relative | 1.99 (1.89, 2.09) | 2.27 (2.10, 2.44) | ||

| AIC | 144,931.57 | 143,050.40 | 69,625.137 | 68,803.505 |

| Widowhood | ||||

| Widowhood | 3.85 (2.81, 5.28) | 3.41 (2.49, 4.68) | 4.10 (2.98, 5.64) | 3.64 (2.64, 5.00) |

| Birth year | 1.01 (1.01, 1.02) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.02) | 1.04 (1.03, 1.05) | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) |

| Parental education (mid vs. low) |

0.85 (0.79, 0.91) | 1.00 (0.90, 1.10) | ||

| Parental education (high vs. low) |

0.70 (0.66, 0.75) | 0.76 (0.69, 0.84) | ||

| Early Deviant Behavior | 3.42 (3.19, 3.66) | 4.50 (3.87, 5.24) | ||

| AUD in relative | 2.12 (2.01, 1.24) | 2.41 (2.22, 2.62) | ||

| AIC | 133,332.64 | 131,306.28 | 58,823.054 | 58,024.198 |

We then examined the divorce-AUD association in cousins and full-sibling pairs both of whom were married and who were discordant for divorce and compared the results with those observed in the general population (table 3; Appendix table 1). In males, a moderate decline in the association was seen in discordant relative pairs compared to that observed in the general population with a stronger decline in siblings than cousins. In females, the association was very similar in cousins and the general population but considerably lower in full-siblings. In both sexes, the number of informative monozygotic (MZ) twin pairs were too few to provide stable estimates. We then fitted these results to our genetic co-relative model described above, which produced a better fit in both males and females than the saturated model. Using this model, we estimated HRs for the divorce-AUD association in married MZ twin pairs discordant for divorce for males and females as 3.45 (1.70–7.03) and 3.62 (1.29–10.18), respectively. As the large CIs suggest, these estimates were similar across the sexes but were not precisely known.

Table 3.

Observed and Predicted Hazard Ratios (and 95% Confidence Intervals) for the Onset of Alcohol Use Disorder after Divorce In Married Individuals with no Alcohol Use Disorder Prior to Marriage in the General Population and in Co-relative Pairs Discordant for Divorce.

| Sex | Akaike’s Information Criterion |

Monozygotic twins |

Full siblings | Cousins | Population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Observed | 146,930.35 | NA | 4.64 (3.13, 6.75) | 5.45 (4.21, 7.06) | 6.01 (5.68, 6.36) |

| Predicted from Model | 146,928.40 | 3.45 (1.70, 7.03) | 4.55 (3.20, 6.48) | 5.60 (5.09, 6.16) | 6.00 (5.68, 6.35) | |

| Females | Observed | 70,599.741 | NA | 4.67 (2.67, 8.15) | 7.23 (4.94, 10.60) | 7.44 (6.86, 8.07) |

| Predicted from Model | 70,596.954 | 3.62 (1.29, 10.18) | 5.19 (3.11, 8.68) | 6.81 (5.92, 7.83) | 7.45 (6.88, 8.08) |

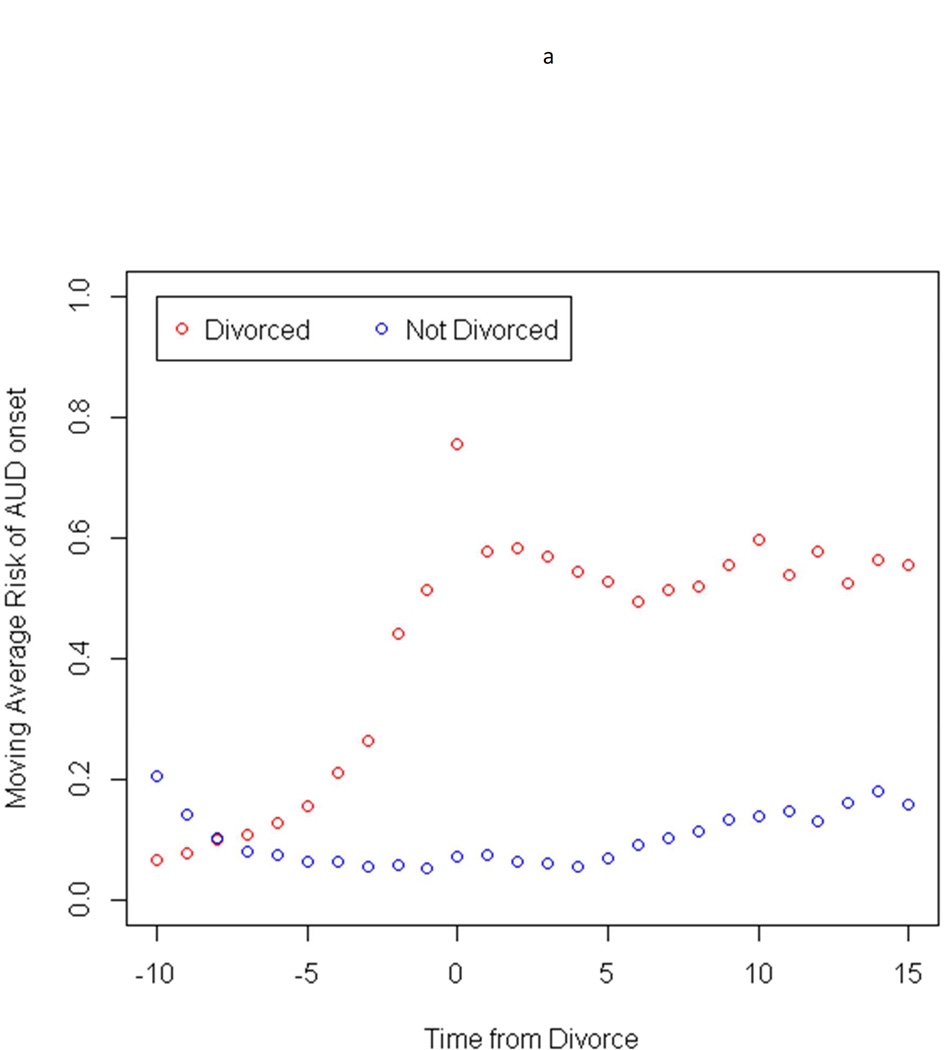

Figure 1a depicts, in males married between the ages of 18 and 25 (mean age at divorce of 32), the prevalence of first AUD registration in the year of the divorce (the zero point in the X-axis) or years earlier and later (red dots) compared to the base rate of AUD registration in the married population with no divorce (blue dots). Between 10 and 7 years prior to the divorce, rates of AUD onset are lower or similar for those with and without a future divorce. Then the rate of AUD registration begins to climb in those with a future divorce peaking in the year of the divorce. The rate of AUD onset then remains substantially elevated for the next 15 years among those who do not remarry – until the end of our observation period. Figure 1b presents the same analysis on an independent cohort of men married between the ages of 25 and 32 with the mean age at divorce of 39. The pattern of results is similar to that seen in figure 1a.

Figure 1.

a – The temporal relationship between divorce and the moving yearly prevalence of first onset of AUD in males (red dots) who were married between the ages of 18 and 25. For each pair, the time of divorce was given the value of zero. The figure also shows (blue dots) the rate of AUD onsets in stably married males whose average age at the zero point matches the age of the divorced sample. All date points, except at age zero, represent a three year rolling average. Therefore, the plotted risk at one time point is the weighted average of the observation at that time point plus the one before and one after. The exception is the estimate at time 1 or −1 which is the weighted average only of time 1 (or −1) and 2 (or−2) and does not include the value at time 0.

b – The temporal relationship between divorce and the yearly prevalence of first onset of AUD in males (red dots) who were married between the ages of 26 and 35. See legend to figure 1a for further methodological details.

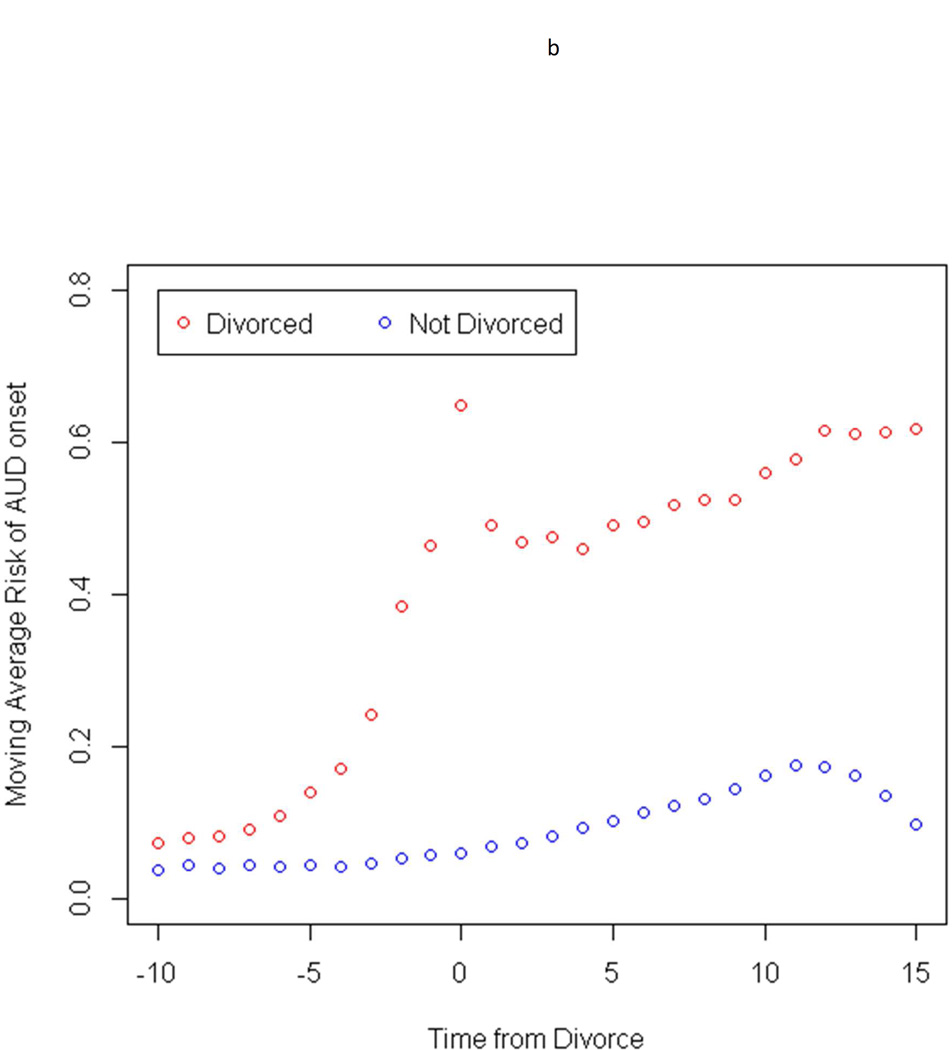

Figure 2a presents results in females married between the ages of 18 and 25 (mean age at divorce of 32). Here the increase in AUD risk occurs only about 3 years prior to the divorce. We see a peak of risk in the year of divorce with the risk remaining elevated for the next 15 years among those who do not remarry. Figure 2b presents a quite similar pattern of results in a different cohort of women married between the ages of 25 and 32 with the mean age at divorce of 36. All four of these figures – showing an increased rate of first AUD registration preceding divorce – suggests that a proportion of the total AUD-Divorce relationship in the population arises from AUD predisposing to future divorce.

Figure 2.

a – The temporal relationship between divorce and the yearly prevalence of first onset of AUD in females (red dots) who were married between the ages of 18 and 25. See legend to figure 1a for further methodological details.

b – The temporal relationship between divorce and the yearly prevalence of first onset of AUD in females (red dots) who were married between the ages of 26 and 35. See legend to figure 1a for further methodological details.

Our sample contained 9,204 males and 3,835 females with a registration for AUD prior to first marriage among whom, controlling for birth year, divorce was associated with an increased risk of AUD relapse: HRs=3.20 (2.86– 3.59) and 3.56 (2.75, 4.60), respectively.

Remarriage after Divorce

Our sample contained 86,698 males and 120,013 females who divorced, out of whom 22,874 women and 33,232 males remarried, at a mean age of 37.6 (4.9) and 35.8 (5.4), respectively. A Cox proportional hazard model with re-marriage as a time-dependent covariate demonstrated a substantial decline in risk for first AUD registration in both males (0.56, 0.52–0.64) and females (0.61, 0.55–0.69).

Widowhood

Given the relatively young age of the sample, during our follow-up period, only 0.24% of men (n=1,064) and 0.47% of women (n=2,334) were widowed with an average age of widowhood around 40 (table 1). Using a Cox proportional hazard model with death of spouse as a time-dependent covariate and controlling only for year of birth, widowhood was associated with an increased risk for a subsequent first onset of AUD in both men (HR=3.85 (2.81–5.28)) and women (HR=4.10 (2.98–5.64)) (appendix figures 1a and 1b). Adding the same confounders used above for divorce produced modest attenuations in these associations: Male – 3.41 (2.49–4.68); Females – 3.64 (2.64–5.00). In females only, widowhood had a stronger association with risk for future AUD if the spouse did not versus did have a lifetime history of AUD: 3.69 (2.61–5.22) versus 1.17 (0.52–2.65). Widowhood was too rare to permit co-relative analyses.

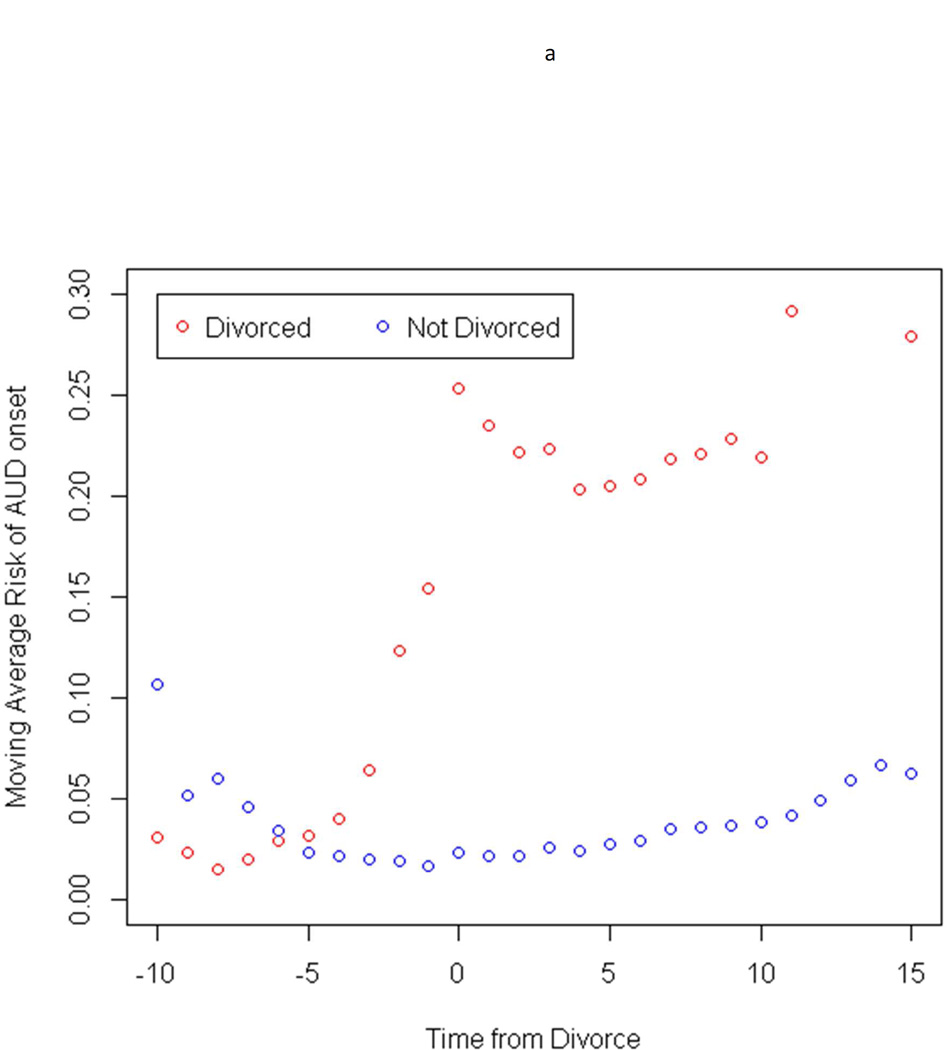

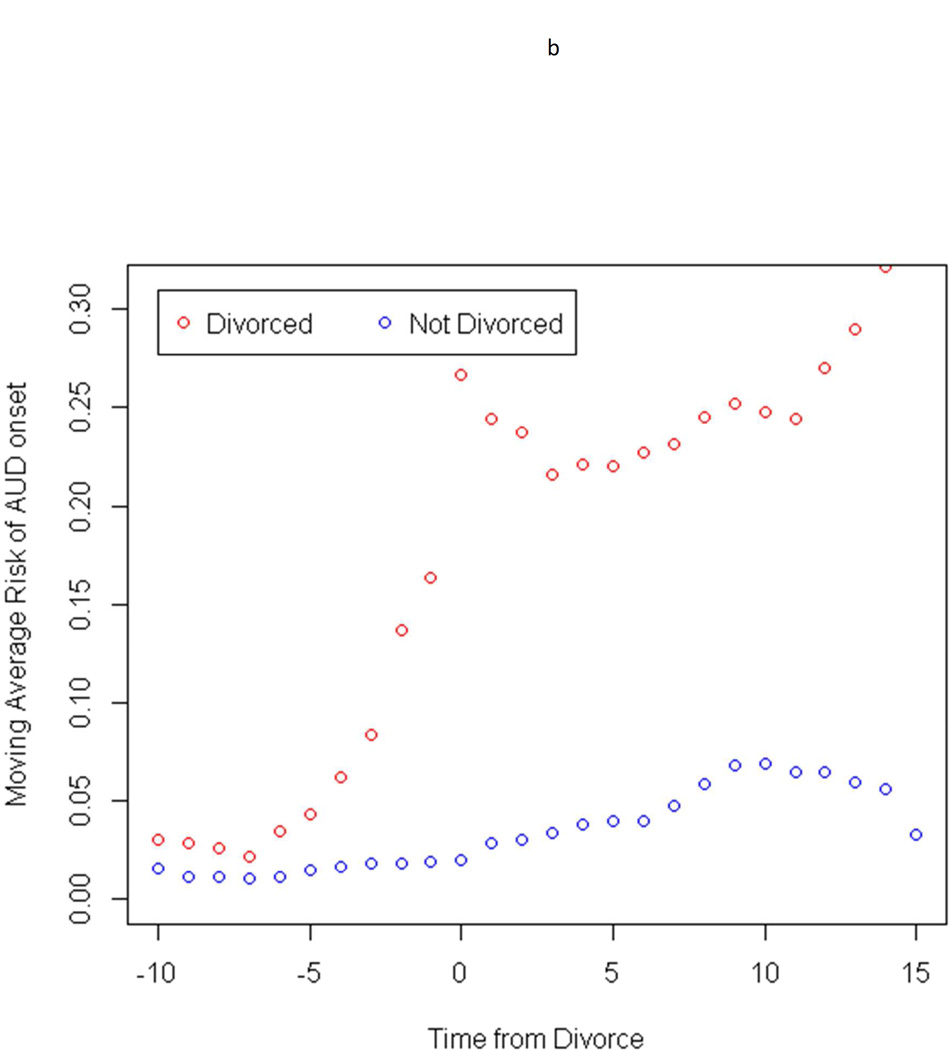

Modifiers

In males and females, the yearly increased risk for AUD onset after divorce was 0.24 and 0.10, respectively, in those without a family history of AUD, and was significantly higher (both p<0.0001) -- 0.51% and 0.25% -- in those with a family history (appendix figures 2a and 2b). In those without externalizing behavior prior to age 18, the yearly increased AUD risk after divorce was 0.29 and 0.15 in males and females, and increased significantly (both p<0.0001) to 0.75 and 0.39 in those with an externalizing history prior to marriage (appendix figures 3a and 3b).

DISCUSSION

The goal of these analyses was to clarify the magnitude and nature of the association between divorce and onset of AUD. To do so, we performed seven sets of analyses that we examine in turn.

Our first goal was to quantify, among individuals with no AUD prior to marriage, the prospective relationship between divorce and subsequent onset of AUD. We found strong associations, with the rates of first onset of AUD increasing after divorce around 6-fold in men and over 7-fold in women. Our results are comparable with two prior prospective studies in both sexes. In a Dutch general population sample, divorce predicted a strong excess of subsequent alcohol abuse (OR=3.9) (16). In a longitudinal study from a Michigan HMO, the risk ratio for “alcohol disorder symptoms” after divorce was substantially elevated (6.6) (25). While these prospective analyses, which document a robust association in the Swedish population between divorce and AUD onset, are consistent with a causal impact of divorce on AUD, it is plausible that a range of confounding variables might be responsible for some or all of this observed association.

Our second set of analyses therefore added to our predictive models three potentially key confounding variables that all robustly predicted risk for AUD: SES of rearing, predisposition to externalizing psychopathology and familial risk for AUD. Their addition modestly attenuated the prior associations with HRs by ~ 15%.

Our third set of analyses used a complementary approach to clarifying the sources of the divorce AUD association. Instead of specifying individual confounders to be controlled statistically, the co-relative approach – in which we compare the risk for AUD in pairs of married relatives discordant for divorce – controls for all familial confounding traits and behaviors. This is a powerful approach because the vast majority of human behavioral traits are correlated in family members (26) and the individual traits need not be specified or even known. For causal inference, the most informative relative pair is married monozygotic (MZ) twins where one has divorced and the other has not as these twins share all their genes at conception and are reared in the same environment. Such twins were too rare even in our large Swedish samples to generate stable statistical estimates. However, we developed a simple model in which the results across a range of pairs of relatives including MZ twins can be estimated from observed data. In males, we found, as expected, that the observed HR between divorce and AUD was highest in the general population, modestly lower in discordant cousins and moderately lower still in discordant full-siblings. From these results we could predict, in a model which fitted the data well, that the HR for AUD in married MZ pairs discordant for divorce declined 42% from that in the general population. The results from females were similar with a slightly greater decline in the divorce-AUD association from the population to discordant MZ twins of 51%. This pattern is consistent with the interpretation that the association between divorce and AUD is in part causal and in part due to confounding familial factors, the latter of which was previously shown in a study of Australian twins (27).

Our fourth set of analyses examined closely the temporal patterning of onsets of AUD with respect to the time of divorce. Looking at two cohorts married at ages 18–25 and 26–35 separately in males and females, we saw broadly similar patterns. Not unexpectedly, an increased risk for AUD onset began a few years prior to the divorce, which is consistent with marital dissolution reflecting a process rather than just a discrete event (28). But in both sexes and in both age groups, the risk for AUD increased substantially in the year of the divorce and remained elevated for many years in those who did not remarry. Fifth, we showed that in individuals with an AUD registration prior to marriage, divorce increased the risk for an AUD relapse although with a smaller effect size than for a first onset.

Our sixth set of analyses followed up on our previous examination of the substantial reduction in risk for onset of AUD in single individuals who marry for the first time (17). We reasoned that if the association between marital status and AUD risk was truly causal, remarriage after divorce should also convey protective effects. This was indeed what we found although the protective effect of marriage was more modest than that found previously in single individuals both in males (0.56 versus 0.41) and females (0.61 versus 0.27) (17).

Finally, since drinking problems can themselves contribute to divorce, we wanted to examine how another form of spousal loss – widowhood – would impact AUD risk. Given the relative youth of our sample, widowhood was rare but was nonetheless strongly associated with an increased risk for AUD in both males and females. This is consistent with previous findings showing that bereavement is associated with prospective increases in drinking (29) and excess alcohol-related mortality (30). These associations were weaker than seen with divorce in both sexes but also attenuated less with the addition of covariates. This would be the expected pattern if the proportion of the association between spousal loss and AUD due to causal factors was greater for widowhood than divorce. While the data was sparse, the temporal pattern of the onset of AUD in association with widowhood was consistent with an association that was largely driven by causal and long-lasting effects (appendix figures 1a and 1b).

We found, in both sexes, a much larger effect on risk for AUD of divorce when the spouse did not versus did have a history of AUD. We saw a similar effect with widowhood but only in females. These results suggest that it is not only the state of matrimony and the associated social roles that are protective against AUD (31). Rather, they are consistent with the importance of direct spousal interactions where one individual monitors and tries to control his or her spouse’s drinking (14). A non-AUD spouse is likely to be much more effective at such control than a spouse with AUD.

Limitations

These results should be interpreted in the context of three potentially important methodological limitations. First, we detected subjects with alcohol use disorder from medical, legal and pharmacy records, and so did not require respondent cooperation or accurate recall. Compared to structured interviews, however, this method surely produces both false negative and false positive diagnoses. Given that the population prevalence of AUD in our sample is considerably lower than that found in interview surveys (1;32) (including in next-door Norway) (33), false negative diagnoses are likely much more common and severity of cases more severe. The validity of our AUD definition is supported by the high rates of concordance observed across our ascertainment methods (34).

Second, our examination of the temporal patterning of spousal loss and AUD onsets with respect to the time of divorce did not account for leftward censoring, that for some couples, the time between marriage and divorce was short. We re-ran all our analyses only on the subgroup of spouses married at least 5 years prior to divorce with only very modest changes in the pattern of results.

Third, our choice of cohort (born 1960–1990, married after 1989, studied till 2008) was a compromise that maximized our sample of married individuals (missing a few with early marriage) who subsequently divorced (missing a few with late divorce.)

Conclusions

Our results should be interpreted in the context of our prior study in the same population showing that first marriage is associated with a substantial reduction in AUD that appears to be largely causal in nature (35). In complementary analyses, we here show that spousal loss through divorce or bereavement is associated with a large and enduring increase in risk for AUD, associations that appear to arise from both causal and non-causal processes. The AUD status of the spouse altered the association between divorce and AUD, and widowhood and AUD (women only), highlighting the importance of spouse characteristics for the behavioral health consequences of spousal loss. Those with high familial risk and a personal history of externalizing behaviors were more sensitive to the pathogenic effects of divorce. The pronounced elevation in AUD risk following divorce or widowhood, and the protective effect of both first marriage and remarriage against subsequent AUD speaks to the profound impact of marriage on problematic alcohol use and the importance of clinical surveillance for AUD among divorced or widowed individuals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the grants R01AA023534 and K01AA024152 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the Swedish Research Council (K2012-70X-15428-08-3), the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (In Swedish: Forte; Reg.nr: 2013-1836), the Swedish Research Council (2012-2378; 2014-10134) and FORTE (2014-0804) as well as ALF funding from Region Skåne.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Reference List

- 1.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B, Hasin DS. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Aug 1;72(8):757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Walters EE, Forthofer MS. The social consequences of psychiatric disorders, III: probability of marital stability. Am J Psychiatry. 1998 Aug;155(8):1092–1096. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilsnack SC, Klassen AD, Schur BE, Wilsnack RW. Predicting onset and chronicity of women's problem drinking: a five-year longitudinal analysis. Am J Public Health. 1991 Mar;81(3):305–318. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.3.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Power C, Rodgers B, Hope S. Heavy alcohol consumption and marital status: disentangling the relationship in a national study of young adults. Addiction. 1999 Oct;94(10):1477–1487. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941014774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halme JT, Seppa K, Alho H, Pirkola S, Poikolainen K, Lonnqvist J, Aalto M. Hazardous drinking: prevalence and associations in the Finnish general population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008 Sep;32(9):1615–1622. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agren G, Romelsjo A. Mortality in alcohol-related diseases in Sweden during 1971–80 in relation to occupation, marital status and citizenship in 1970. Scand J Soc Med. 1992 Sep;20(3):134–142. doi: 10.1177/140349489202000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verhulst B, Neale MC, Kendler KS. The heritability of alcohol use disorders: a meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychol Med. 2015 Aug 29;45(5):1061–1072. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sher KJ, Trull TJ, Bartholow BD, Vieth A. Personality and Alcoholism: Issues, Methods, and Etiological Processes. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. Second. NY: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 54–105. 1-57230-410-3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kandel DB, Davies M, Karus D, Yamaguchi K. The consequences in young adulthood of adolescent drug involvement. An overview. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986 Aug;43(8):746–754. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aughinbaugh A, Robles O, Sun H. Marriage and Divorce: Patterns by Gender, Race, and Educational Attainment. [October 2013] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2013 Monthly Labor Review. 10-21-2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGue M, Lykken D. Genetic influence on risk of divorce. Psychol Sci. 1992;3(6):368–373. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ostermann J, Sloan FA, Taylor DH. Heavy alcohol use and marital dissolution in the USA. Soc Sci Med. 2005 Dec;61(11):2304–2316. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cranford JA. DSM-IV alcohol dependence and marital dissolution: evidence from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014 May;75(3):520–529. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Umberson D. Gender, marital status and the social control of health behavior. Soc Sci Med. 1992 Apr;34(8):907–917. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90259-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Temple MT, Fillmore KM, Hartka E, Johnstone B, Leino EV, Motoyoshi M. A meta-analysis of change in marital and employment status as predictors of alcohol consumption on a typical occasion. Br J Addict. 1991 Oct;86(10):1269–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Overbeek G, Vollebergh W, de GR, Scholte R, de KR, Engels R. Longitudinal associations of marital quality and marital dissolution with the incidence of DSM-III-R disorders. J Fam Psychol. 2006 Jun;20(2):284–291. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kendler KS, Lönn SL, Salvatore J, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Effect of Marriage on Risk for Onset of Alcohol Use Disorder: A Longitudinal and Co-relative Analysis in a Swedish National Sample. AJP. 2016 May 16; doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15111373. ([epub]) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johansson P. The Social Costs of Alcohol in Sweden 2002. Stockholm: Stockholm University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Vaus D, Gray M, Qu L, Stanton D. The economic consequences of divorce in six OECD countries: Research Report No. 31. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies; 2015. Report No.: No. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lichtenstein P, Sullivan PF, Cnattingius S, Gatz M, Johansson S, Carlstrom E, Bjork C, Svartengren M, Wolk A, Klareskog L, de FU, Schalling M, Palmgren J, Pedersen NL. The Swedish Twin Registry in the third millennium: an update. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006 Dec;9(6):875–882. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kendler KS, Larsson Lönn S, Morris NA, Sundquist J, Långström N, Sundquist K. A Swedish National Adoption Study of Criminality. Psychol Med. 2014;44(9):1913–1925. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kendler KS, Sundquist K, Ohlsson H, Palmer K, Maes H, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Genetic and familial environmental influences on the risk for drug abuse: a national Swedish adoption study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012 Jul;69(7):690–697. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akaike H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika. 1987;52:317–332. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holt JD, Prentice RL. Survival analyses in twin studies and matched pair experiments. Biometrika. 1974;61(1):17. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Alcohol disorders in young adulthood: effects of transitions into adult roles. J Health Soc Behav. 1996 Dec;37(4):339–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polderman TJ, Benyamin B, de Leeuw CA, Sullivan PF, van BA, Visscher PM, Posthuma D. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat Genet. 2015 Jul;47(7):702–709. doi: 10.1038/ng.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waldron M, Heath AC, Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Martin NG. Alcoholic marriage: later start, sooner end. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011 Apr;35(4):632–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wheaton B. Life Transitions, Role Histories, and Mental-Health. Am Soc Rev. 1990 Apr;55(2):209–223. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perreira KM, Sloan FA. Life events and alcohol consumption among mature adults: a longitudinal analysis. J Stud Alcohol. 2001 Jul;62(4):501–508. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martikainen P, Valkonen T. Mortality after the death of a spouse: rates and causes of death in a large Finnish cohort. Am J Public Health. 1996 Aug;86(8):1087–1093. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.8_pt_1.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamaguchi K, Kandel DB. On the Resolution of Role Incompatibility - A Life Event History Analysis of Family Roles and Marijuana Use. Amer J Sociol. 1985;90(6):1284–1325. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994 Jan;51(1):8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kringlen E, Torgersen S, Cramer V. A Norwegian psychiatric epidemiological study. AJP. 2001 Jul;158(7):1091–1098. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kendler KS, Ji J, Edwards AC, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. An Extended Swedish National Adoption Study of Alcohol Use Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Jan 7;72(3):211–218. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kendler KS, Lonn SL, Salvatore J, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Effect of Marriage on Risk for Onset of Alcohol Use Disorder: A Longitudinal and Co-Relative Analysis in a Swedish National Sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2016 May 16; doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15111373. May 16([epub]):appiajp201615111373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.