Abstract

Loss of fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23) causes hyperphosphatemia, extraskeletal calcifications, and early mortality; excess FGF23 causes hypophosphatemia with rickets or osteomalacia. However, FGF23 may not be important during fetal development. FGF23 deficiency (Fgf23 null) and FGF23 excess (Phex null) did not alter fetal phosphorus or skeletal parameters. In this study, we further tested our hypothesis that FGF23 is not essential for fetal phosphorus regulation but becomes important after birth. Although coreceptor Klotho null adults have extremely high FGF23 concentrations, intact FGF23 was normal in Klotho null fetuses, as were fetal phosphorus and skeletal parameters and placental and renal expression of FGF23 target genes. Pth/Fgf23 double mutants had the same elevation in serum phosphorus as Pth null fetuses, as compared with normal serum phosphorus in Fgf23 nulls. We examined the postnatal time courses of Fgf23 null, Klotho null, and Phex null mice. Fgf23 nulls and Klotho nulls were normal at birth, but developed hyperphosphatemia, increased renal expression of NaPi2a and NaPi2c, and reduced renal phosphorus excretion between 5 and 7 days after birth. Parathyroid hormone remained normal. In contrast, excess FGF23 exerted effects in Phex null males within 12 hours after birth, with the development of hypophosphatemia, reduced renal expression of NaPi2a and NaPi2c, and increased renal phosphorus excretion. In conclusion, although FGF23 is present in the fetal circulation at levels that may equal adult values, and there is robust expression of FGF23 target genes in placenta and fetal kidneys, FGF23 itself is not an important regulator of fetal phosphorous metabolism.

Fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23) is a hormone produced by osteocytes and osteoblasts, which acts on distant tissues to regulate the supply of phosphorus at the bone surface (1). Its main actions occur in the kidneys, wherein FGF23 downregulates expression of sodium-phosphate cotransporters 2a and 2c (NaPi2a and NaPi2c) in the proximal renal tubules, thereby increasing excretion of phosphorus (2). FGF23 also inhibits renal expression of 1-α-hydroxylase (Cyp27b1) and increases expression of 24-hydroyxlase (Cyp24a1), which together reduce the circulating concentration of calcitriol (2). Within the intestines, FGF23 reduces dietary phosphorus absorption indirectly through its actions to lower serum calcitriol, and directly by inhibiting expression of NaPi2b (2). The sum of these actions is that serum phosphorus is lowered. FGF23 also acts on the parathyroid glands to inhibit parathyroid hormone (PTH), which contributes to lowering serum calcitriol (3, 4). High serum phosphorus and calcitriol are potent stimuli for FGF23 synthesis and release, whereas PTH modestly stimulates FGF23 (3, 4). A phosphorus-sensing receptor is likely expressed by osteoblasts and osteocytes to explain the responsiveness of FGF23 to changes in serum phosphorus; a candidate sensor in eukaryotic cells has recently been identified (5).

Genetic disorders that lead to loss or excess of FGF23 have illuminated the physiological importance of this phosphotrophic hormone. Loss of FGF23 activity reduces urine phosphorus excretion, increases serum calcitriol, and increases intestinal phosphorus absorption, thereby leading to hyperphosphatemia, extraskeletal calcifications, and early mortality (6–8). Despite PTH’s actions to lower serum phosphate by suppressing renal NaPi2a and NaPi2c expression, PTH is unable to correct hyperphosphatemia caused by absence of FGF23, perhaps due to the effect of high serum calcitriol to suppress PTH. Loss of FGF23’s coreceptor Klotho leads to a similar phenotype of hyperphosphatemia and reduced renal phosphorus excretion, confirming the critical role of Klotho to mediate FGF23’s actions to regulate phosphate metabolism (6–9). Excess FGF23 activity causes the opposing effects of increased renal phosphorus excretion, low calcitriol, normal to low PTH, and low intestinal phosphorus absorption, thereby leading to hypophosphatemia, myopathy, and impaired mineralization of bone (rickets or osteomalacia) (6, 8, 9).

The preceding summary refers to established actions of FGF23 in young and adult humans and mice. In contrast, normal fetal phosphorus metabolism shows significant differences from the adult (10). Mammalian fetuses are hyperphosphatemic; human fetuses have cord blood phosphorus concentrations approximately 0.5 mmol/l higher than the maternal value (10). Phosphorus is actively transported across the placenta and this likely contributes to its high concentration in the fetal circulation (10). In turn, phosphorus regulates endochondral bone development by inducing apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes (11, 12) and by being laid down in osteoid before calcium binds to it (11, 13, 14). Consequently, high or low serum phosphorus will conceivably disrupt the formation and mineralization of the endochondral skeleton in utero. PTH and PTH-related protein (PTHrP) each regulate phosphorus to some extent, as we have previously reported that loss of parathyroids, or the genes encoding either PTH or PTHrP, lead to an increase in fetal serum phosphorus above normal values (15–18). However, neither PTH or PTHrP regulate placental phosphorus transport (10). Calcitriol may not be an important regulator of fetal phosphorus metabolism because serum phosphorus, PTH, skeletal development, and mineralization were normal in fetuses that lacked the vitamin D receptor (19, 20).

Because FGF23 plays an important role in regulating phosphorus metabolism in children and adults, it was expected to be of similar importance during fetal development. FGF23 is predominantly expressed in fetal rat osteoblasts, as well as in thymus, liver, and kidney (21); we have also found a low level of expression in murine placenta (22). Intact FGF23 concentrations range from equal to or lower than the maternal concentration in wild-type (WT) fetuses (22, 23), whereas limited data have shown low intact but high C-terminal FGF23 concentrations in human cord blood (24–26). Murine fetal kidneys and placenta each abundantly express Klotho, FGF receptor subtypes 1 through 4, and the main targets of FGF23 action that include NaPi2a, NaPi2b, NaPi2c, Cyp27b1, and Cyp24a1 (22). Human trophoblasts express Cyp27b1, Cyp24a1, and Klotho, whereas cord blood levels of soluble Klotho are about sixfold higher than adult and neonatal values (10, 25).

Surprisingly, we found that loss of FGF23 (in Fgf23 null fetuses, a model of hereditary hyperphosphatemic tumor calcinosis) and excess FGF23 (in Phex null male fetuses, a model of X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets) each failed to disturb key physiological parameters of phosphorus homeostasis (22). These included serum phosphorus, calcium, PTH, renal excretion of phosphorus into amniotic fluid, placental phosphorus transport, skeletal morphology, skeletal content of phosphorus, and expression of NaPi2a, NaPi2b, NaPi2c, and Cyp27b1 within placenta and kidneys (22). Loss of FGF23 did cause a modest 40% reduction in renal expression of Cyp24a1 but no change in serum calcitriol, whereas high levels of FGF23 in Phex mutants caused an increase in placental and renal Cyp24a1 expression and a modest reduction in serum calcitriol (22). However, these changes in gene expression were minor in the context that whole animal phosphorus metabolism and skeletal development appeared undisturbed. A second group independently confirmed that high levels of FGF23 in Phex null male fetuses caused no change in fetal serum phosphorus, despite increased renal and placental expression of Cyp24a1 and reduced calcitriol (23). The resilience of the fetal-placental unit to obtain phosphorus was evident by comparing offspring of WT mothers mated to Phex null males and Phex+/− mothers mated to WT males; the low serum phosphorus in Phex+/− mothers did not affect serum phosphorus or FGF23 level in the respective fetal genotypes (22).

In this study, we further tested our hypothesis that FGF23 is not essential for fetal phosphorus regulation but becomes important after birth. We did so by first examining Klotho null fetuses: If an FGF family member compensates for loss of FGF23 during fetal development, then fetuses lacking the essential coreceptor Klotho should display disturbances in phosphorus metabolism that are not found in Fgf23 null fetuses. Conversely, if our prior findings in Fgf23 null fetuses mean that FGF23 is not required for fetal phosphorus metabolism, then Klotho null fetuses should display normal parameters of phosphorus metabolism. We created Fgf23/Pth double-mutants to determine if loss of FGF23 potentiated the effect of hypoparathyroidism to cause hyperphosphatemia and reduced skeletal mineral content. We then determined the postnatal time frame in which loss of FGF23 or Klotho, or high levels of FGF23, begin to disturb serum phosphorus, renal phosphorus excretion, serum PTH, and renal expression of NaPi2a or NaPi2c.

Materials and Methods

Animal husbandry

The engineering of Fgf23, Klotho, and Pth gene deletion models have been previously described (27–29). C57BL/6-PhexHyp-2J/J (Phex) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Fgf23, Klotho, and Phex mice were kept in a C57BL/6 background, whereas Pth mice were maintained in a Black Swiss background. Each colony was maintained by breeding heterozygous-deleted mice together, and periodically back-crossed to the respective parent strain. Genotyping of Fgf23, Phex, Klotho, and Pth fetuses was done by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on DNA extracted from tail clips using previously described primer sequences (22, 28, 30, 31). The Phex genotyping required 3 separate reactions including sex determination, as previously detailed (22). Doubly-heterozygous mice (Fgf23+- / Pth+/−) were generated by cross-breeding heterozygotes from the respective colonies.

Mice were mated overnight; the presence of a vaginal mucus plug on the morning after mating marked embryonic day (ED) 0.5. Normal gestation is 19 days. Fetal analyses were done at ED 18.5 unless otherwise specified. Adult mice were given a standard chow (1% calcium, 0.75% phosphorus) diet and water ad lib. The Institutional Animal Care Committee of Memorial University of Newfoundland approved all procedures involving live animals.

Chemical and hormone assays

Serum and amniotic fluid were collected using methods previously described (15, 32). Calcium and phosphorus were analyzed using colorimetric assays (Sekisui Diagnostics PEI Inc., Charlottetown, PE, Canada). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were used to measure PTH 1-34 (Immutopics, San Clemente, CA), calcitriol (Immunodiagnostic Systems Ltd., Boldon, Tyne and Wear, UK), and intact FGF23 (Kainos, Japan). Any values that appeared to be below the assay sensitivity were reset to values that equaled the respective assay’s detection limit.

Placental phosphorus transfer

We used an adaptation of the placental calcium transport methodology (22, 32). Briefly, on ED 17.5 pregnant dams were given an intracardiac injection of 50 µCi 32P and 50 µCi 51Cr-EDTA (EDTA is passively transferred and serves as a blood diffusional marker). Five minutes later, the fetuses were removed and later solubilized. The 32P and 51Cr activity within each fetus was separately measured using a liquid scintillation counter and a γ-counter, respectively. Each fetal 32P/51Cr value was normalized within its litter to the mean heterozygous value in order that the aggregate results from different litters could be analyzed. The 32P activity alone was also analyzed after normalizing within each litter.

Fetal ash and skeletal mineral assay

As previously described (16), intact fetuses (ED 18.5) were reduced to ash in a furnace (500°C ×24 hours). A Perkin Elmer 2380 Atomic Absorption Flame Spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer, Guelph, ON, Canada) assayed the calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium content of the ash.

Histology

Undecalcified fetal tibias were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, dehydrated in graded alcohol series, and embedded in paraffin. Von Kossa staining was performed on 5-μm deparaffinized sections using 1% aqueous silver nitrate solution, 45 minutes of exposure to bright light, and counter stain of 2% methyl green.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (qPCR)

Kidneys and placentas were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was purified using the RNeasy Mini Lipid Kit for kidneys and the RNeasy Midi Lipid Kit for placentas (Qiagen, Toronto, ON, Canada). RNA quantity and quality was confirmed with the Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). We used TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays (with the manufacturer’s predesigned primers and probes for optimal amplification) and Fast Advanced Master Mix from Applied BioSystems (ABI)/Life Technologies (Burlington, ON, Canada) to determine expression of Cyp27b1, Cp24a1, Fgf23, Klotho, and FGF receptors 1 through 4 (Fgfr1-Fgfr4). Details of conditions and cycle times have been previously reported (17, 33, 34). Briefly, cDNA was synthesized using the Taqman® High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (ABI), and singleplex qPCR reactions were run in triplicate on the ViiA™ 7 Real-Time PCR System (ABI) (17, 19). The minimum sample size was 5 for each genotype (WT and null). Relative expression was determined from the threshold cycle (CT) normalized to the reference genes.

Microarray

RNA was analyzed at The Centre for Applied Genomics, Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, ON, Canada) using the Mouse Gene ST 1.0 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Raw data were normalized in R version 3.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the robust multiarray average algorithm (35). Differentially expressed genes were identified using the local-pooled-error test (36). False discovery rate (37) was set at 0.01 such that genes with adjusted P values < 0.01 were considered to be statistically significant.

Neonatal studies

Neonatal studies were carried out after spontaneous deliveries on postnatal days 1 (less than 12 hours after birth), 3, 5, 7, and 10 in pups obtained from Fgf23+/− and Klotho+/− dams, whereas day 10 was omitted for pups obtained from Phex+/− mothers. Serum was collected into a capillary tube after incising the neck, similar to fetal blood collection. The pelvis was opened to reveal the bladder, which was removed intact and transferred to a clean 0.6 mL tube. Within that tube, the bladder was pierced to free the urine; the bladder tissue was then discarded. The kidneys were harvested and snap frozen. Kidneys and urine were analyzed from the days in which serum phosphorus first became abnormal in the respective colonies.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using StatPlus:Mac Professional 2009, Build 6.0.3 (AnalystSoft Inc, Vancouver, BC, Canada). Analysis of variance was used for analysis of biochemical, transport, and ash data, with a post hoc test to determine which pairs of means differed significantly. Data are reported as mean ± standard error. The qPCR data were analyzed by the comparative CT method (ΔCT) (38), with 2-tailed probabilities reported as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Phenotype of Klotho null fetuses

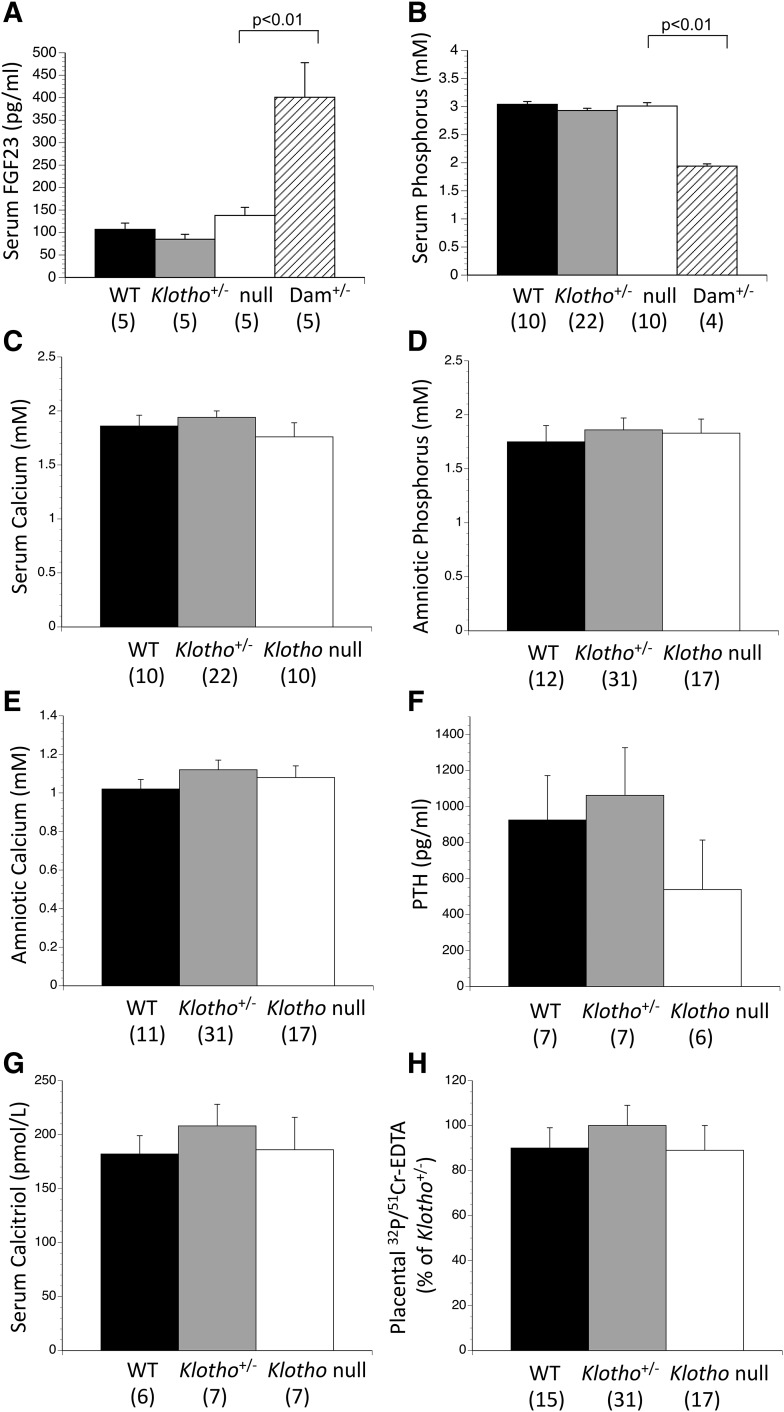

Loss of a receptor or coreceptor (such as Klotho) can lead to a compensatory increase in the concentration of the ligand; a >1,000-fold increase in intact FGF23 has been reported in postnatal Klotho null mice (3, 39, 40). However, we found that intact FGF23 was no different among WT, Klotho+/−, and Klotho null fetuses [Fig. 1(A)]. The intact FGF23 value in WT fetuses was ∼25% of the maternal value, and is similar to what we have observed in prior studies in the inbred C57BL/6 background (22). Conversely, in the outbred Black Swiss background, fetal intact FGF23 levels were similar to maternal values (22).

Figure 1.

Loss of Klotho does not disturb fetal phosphorus, PTH, calcitriol, or placental phosphorus transport. In contrast to the very high intact FGF23 concentrations that have been found in postnatal (young and adult) Klotho null mice, (A) Klotho null fetuses had normal serum intact FGF23. Klotho null fetuses showed no disturbances in (B) serum phosphorus and (C) calcium, (D) amniotic fluid phosphorus and (E) calcium, (F) serum PTH, or (G) serum calcitriol. (H) Placental transport of 32P at 5 minutes was normal when corrected for 51Cr-EDTA diffusion or when 32P was analyzed alone (not shown). The numbers of observations are indicated in parentheses. mM, mmol/L.

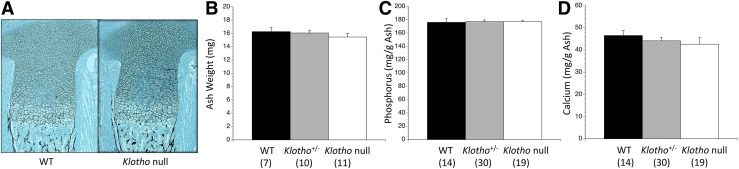

Loss of Klotho did not alter serum phosphorus and calcium, and amniotic fluid phosphorus and calcium [Fig. 1(B–E)]. Similarly there was no change in PTH or calcitriol [Fig. 1(F) and 1(G)]. Placental phosphorus transport, expressed as the activity of 32P/51Cr accumulated in each fetus after 5 minutes, was no different among the fetal genotypes [Fig. 1(H)]. WT and Klotho null fetuses were indistinguishable by visual appearance at birth and could only be identified by PCR genotyping, which also maintained the blinding of the experiments and subsequent analyses. The tibias had normal lengths, morphology, and mineralization pattern at the microscopic level [Fig. 2(A)]. The mineral content was quantified by reducing intact fetuses to ash and then measuring the mineral content of that residue. There were no differences in skeletal ash weight, phosphorus, calcium, or (not shown) magnesium content [Fig. 2(B–D)].

Figure 2.

Skeletal parameters are normal in Klotho null fetuses. (A) Klotho null tibias showed normal endochondral development with no alteration in the lengths or cellular morphology of the cartilaginous or boney compartments, and a normal distribution of mineral (black stain due to von Kossa). Fetuses were reduced to ash and the mineral content of that ash was then assayed. On ED 18.5, Klotho null fetuses had normal (B) ash weight as well as ash content of (C) phosphorus, (D) calcium, and magnesium (not shown). The numbers of observations are indicated in parentheses.

We also examined the expression of Klotho and FGF23 target genes in placentas and kidneys from WT and Klotho null fetuses. WT placentas and kidneys showed robust expression of Klotho that was absent in respective Klotho null tissues (Table 1). NaPi2a, NaPi2b, NaPi2c, Cyp27b1, Cyp24a1, and Fgfr1–Fgfr4 were each expressed within placentas, with NaPi2b displaying the most abundant expression (lower CT value) among the sodium-phosphate cotransporters. No differences were evident between WT and Klotho null placentas in any of these genes (Table 1). A very low level of expression of Fgf23 (near the limit of detection) was evident in WT and Klotho null placentas; we previously confirmed this as a true signal by comparing WT to Fgf23 null placentas (22). There were also no differences in any of the FGF23 target genes that were well expressed by WT and Klotho null kidneys (Table 1). Unlike the prior finding that Fgf23 null kidneys had decreased expression of Cyp24a1, it was normal in Klotho null kidneys.

Table 1.

Fgf23 and FGF23 Target Gene Expression in Placentas and Kidneys From WT and Klotho Null Fetuses

| Gene | Placenta |

Fetal Kidneys |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Klotho Null | P Value | WT | Klotho Null | P Value | |

| Fgf23 | 1.00 ± 0.25 | 1.00 ± 0.22 | 0.917 | Undetectable | Undetectable | N/A |

| Klotho | 1.00 ± 0.22 | Undetectable | 0.000 | 1.00 ± 0.11 | Undetectable | 0.000 |

| NaPi2a | 1.00 ± 0.23 | 1.00 ± 0.38 | 0.825 | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 1.20 ± 0.20 | 0.109 |

| NaPi2b | 1.00 ± 0.08 | 0.90 ± 0.24 | 0.559 | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 0.673 |

| NaPi2c | 1.00 ± 0.16 | 1.10 ± 0.15 | 0.431 | 1.00 ± 0.30 | 1.20 ± 0.30 | 0.258 |

| Cyp24a1 | 1.00 ± 0.20 | 0.80 ± 0.36 | 0.364 | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 1.10 ± 0.30 | 0.537 |

| Cyp27b1 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 0.90 ± 0.00 | 0.379 | 1.00 ± 0.30 | 1.20 ± 0.70 | 0.614 |

| Fgfr1 | 1.00 ± 0.08 | 1.20 ± 0.33 | 0.341 | 1.00 ± 0.20 | 1.20 ± 0.10 | 0.225 |

| Fgfr2 | 1.00 ± 0.14 | 1.10 ± 0.19 | 0.284 | 1.00 ± 0.20 | 1.20 ± 0.10 | 0.080 |

| Fgfr3 | 1.00 ± 0.21 | 1.00 ± 0.27 | 0.881 | 1.00 ± 0.30 | 1.20 ± 0.10 | 0.323 |

| Fgfr4 | 1.00 ± 0.18 | 1.20 ± 0.27 | 0.217 | 1.00 ± 0.20 | 1.10 ± 0.10 | 0.610 |

Parameters that showed statistically significant differences between the 2 genotypes are shown in bold text.

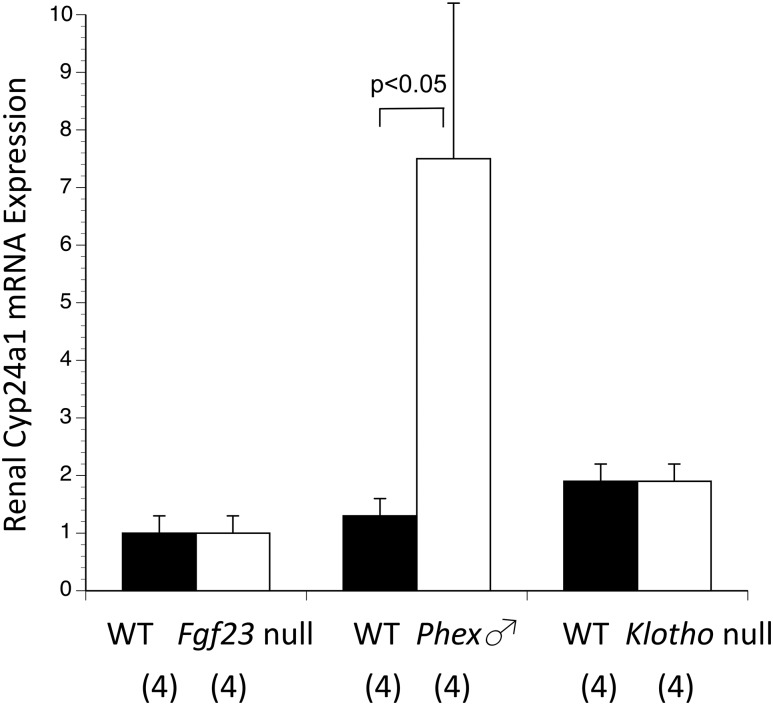

Because the Fgf23 null kidneys had previously shown a modest reduction in Cyp24a1 expression by qPCR that reached the threshold of statistical significance, while Phex null male kidneys (and placentas) had shown the opposite effect of increased Cyp24a1 expression, we repeated the qPCR analysis using all genotypes on 1 plate. This used a larger sample size of fresh kidneys from Fgf23 null, Klotho null, and Phex null male fetuses, and corresponding WT kidneys from within the same litters. Cyp24a1 expression was once again significantly increased in Phex null male kidneys, but unchanged in Fgf23 null and Klotho null kidneys (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Expression of Cyp24a1 among kidneys of the 3 null genotypes vs corresponding WT. Cyp24a1 expression was normal in Fgf23 null and Klotho null fetal kidneys, but significantly increased in Phex null male fetal kidneys. To compare all 6 different genotypes, all values were normalized to the WT placentas from the Fgf23 colony. The numbers of observations are indicated in parentheses.

Microarray on Fgf23 and Phex null male placentas

To further confirm that loss of FGF23 or high levels of FGF23 did not importantly alter placental gene expression (apart from changes in Cyp24a1 expression), genomewide microarray analyses were carried out on Fgf23 null and Phex null male placentas, and compared with WT placentas. No significant changes in gene expression were noted between Phex null male and WT placentas, or between Fgf23 null and WT placentas.

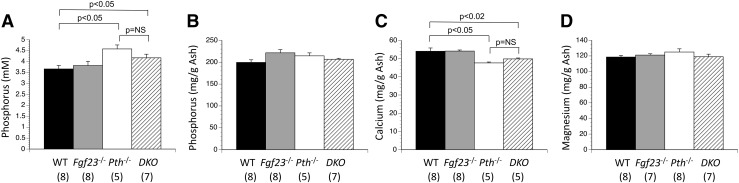

Fgf23/Pth double-mutants

To determine if loss of FGF23 potentiates loss of PTH to cause hyperphosphatemia and reduced skeletal mineral content, Fgf23+-/Pth+/− mice were mated together to create pregnancies containing WT, Pth null, Fgf23 null, and Fgf23/Pth double mutant fetuses. Serum phosphorus was increased by the absence of PTH (Pth nulls), but simultaneous deletion of FGF23 in the double mutants did not alter serum phosphorus any further [Fig. 4(A)]. Similarly, skeletal calcium content was reduced by absence of PTH, but not further altered by the superimposed absence of FGF23 [Fig. 4(B–D)].

Figure 4.

Serum phosphorus and skeletal mineral content in Fgf23/Pth double mutant fetuses. (A) Loss of PTH caused the expected increase in serum phosphorus, whereas superimposed loss of FGF23 in double-mutants (DKO) had no effect. Loss of PTH reduced skeletal (C) calcium but not (B) phosphorus or (D) magnesium content, whereas loss of FGF23 did not affect any of these parameters. The numbers of observations are indicated in parentheses. mM, mmol/L.

Postnatal studies in Fgf23, Phex, and Klotho null pups

Because Fgf23 null, Klotho null, and Phex null male fetuses each displayed normal phosphorus parameters immediately prior to birth, we investigated when the mutants become abnormal after birth.

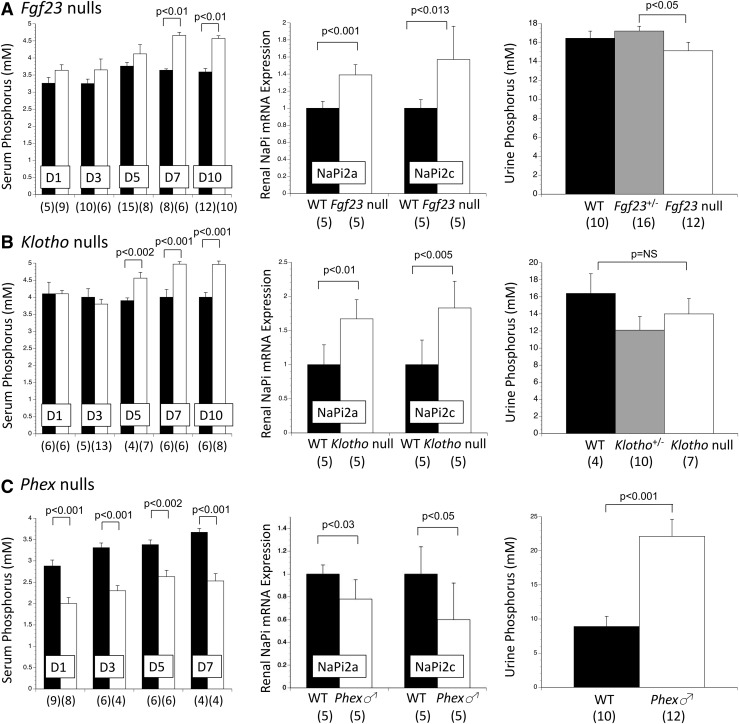

In Fgf23 null pups, serum phosphorus became significantly increased by day 7 after delivery [Fig. 5(A), left panel]. This development was accompanied on that same day by a significant increase in renal NaPi2a and NaPi2c expression [Fig. 5(A), middle panel], and a modest but significant reduction in renal phosphorus excretion [Fig. 5(A), right panel]. PTH did not differ between genotypes at any time point [Fig. 6(A)].

Figure 5.

Postnatal changes in serum phosphorus, renal expression of sodium-phosphate cotransporters, and urine phosphorus excretion among Fgf23, Klotho, and Phex mutant colonies. (A) After an interval of normal serum phosphorus, Fgf23 null mice became hyperphosphatemic by day 7 after birth (left panel), and on that day renal expression of NaPi2a and NaPi2c (middle panel) were significantly increased, whereas renal phosphorus excretion (right panel) was modestly but significantly reduced. (B) Klotho null mice developed hyperphosphatemia by day 5 after birth (left panel), and this coincided with increased renal expression of NaPi2a and NaPi2c (middle panel), and a trend for reduced renal phosphorus excretion (right panel). In contrast to the delayed effects that loss of FGF23 and Klotho have on postnatal phosphorus metabolism, (C) the effects of high levels of FGF23 in Phex null males are shown. Reduced serum phosphorus developed within 12 hours after birth (left panel), accompanied by reduced renal expression of NaPi2a and NaPi2c (middle panel), and increased renal phosphorus excretion (right panel). In all 3 mutant models, there was no change in renal NaPi2b expression at any time point (not shown). The numbers of observations are indicated in parentheses. mM, mmol/L.

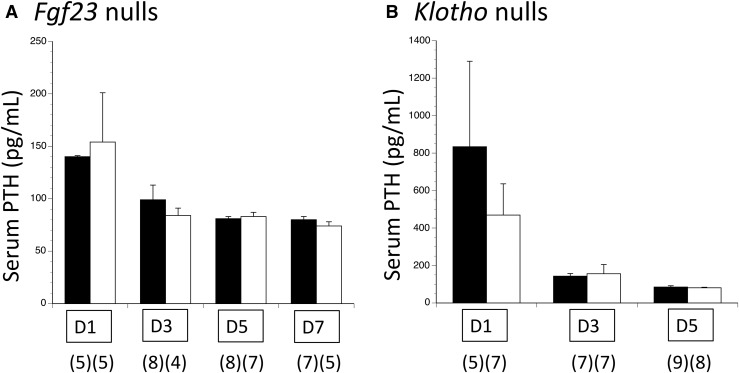

Figure 6.

Postnatal changes in serum PTH in Fgf23 and Klotho mutant colonies. With (A) Fgf23 nulls and (B) Klotho nulls, the slow emergence of hyperphosphatemia was not accompanied by any compensatory increase in PTH. The numbers of observations are indicated in parentheses. mM, mmol/L.

In Klotho null pups serum phosphorus became significantly elevated by day 5 postnatal [Fig. 5(B), left panel], accompanied that same day by increased renal expression of NaPi2a and NaPi2c [Fig. 5(B), middle panel]. There was a nonsignificant trend for reduced urine phosphorus excretion at this time point [Fig. 5(B), right panel]; this relative difference persisted on days 7 and 10 (not shown). PTH did not differ between genotypes at any time point [Fig. 6(A)].

Conversely in Phex null male pups, which have markedly increased circulating FGF23 (22), phosphorus metabolism became abnormal within approximately 12 hours of delivery (i.e., on day 1 postnatal). The changes included reduced serum phosphorus, reduced renal expression of NaPi2a and NaPi2c, and significantly increased renal phosphorus excretion [Fig. 5(C)]

In all 3 mutant models, NaPi2b expression persisted in neonatal kidneys but was unaltered compared with respective WT (not shown).

Discussion

In our prior study we rigorously tested FGF23’s potential role in fetal phosphorus regulation by comparing its absence to its excess, specifically Fgf23 null and Phex null male fetuses and placentas, as well as their respective WT littermates. We found that neither loss of FGF23 nor increased circulating concentrations of FGF23 caused any significant disturbances in phosphorus metabolism, apart from a modest reduction in renal Cyp24a1 expression in Fgf23 null fetuses that did not alter serum calcitriol, and a significant increase in renal Cyp24a1 expression that led to a small decrease in serum calcitriol in Phex null male fetuses.

In the current study, we examined whether loss of FGF23’s coreceptor Klotho alters fetal-placental phosphorus metabolism. We found that Klotho null fetuses had normal serum phosphorus, calcium, PTH, calcitriol, and amniotic fluid content of phosphorus and calcium. Skeletal lengths and morphology, mineralization, ash weight, and ash content of phosphorus, calcium, and magnesium, were all normal. Placental 32P phosphorus transport was no different among the fetal genotypes. Apart from confirming absence of Klotho in Klotho null placentas and kidneys, qPCR revealed no changes in relative expression of potential FGF23 target genes (NaPi2a, NaPi2b, NaPi2c, Cyp27b1, Cyp24a1, and Fgfr1–Fgfr4) in placentas or kidneys of Klotho null compared with WT. We also examined Fgf23/Pth double mutant fetuses and found that whereas loss of PTH had its previously established effect to cause hyperphosphatemia and reduced skeletal calcium content (17), loss of FGF23 had no effect, either alone or in combination with loss of PTH. Collectively, these findings confirm that neither FGF23 nor Klotho are required to regulate fetal phosphorus homeostasis, placental phosphorus transport, or skeletal development. This is in sharp contrast to the critical role that FGF23 plays in regulating phosphorus and skeletal metabolism in the adult and child.

We further investigated all 3 models (Fgf23 null, Klotho null, and Phex null male) to determine when absence or excess of FGF23’s actions begin to cause detectable disturbances in phosphorus outcomes. Fgf23 null and Klotho null pups showed consistent results of normal serum and urine phosphorus for several days after birth. By day 5 postnatal in Klotho nulls, and day 7 postnatal in Fgf23 nulls, the serum phosphorus became increased, whereas the urine phosphorus showed a slight decrease that was statistically significant in Fgf23 nulls but not significant in Klotho nulls. Due to small obtainable urine volumes it was not possible to measure the creatinine concentration; the lack of correction for creatinine likely increased the variability of urine phosphorus results. This apparent reduction in renal phosphorus excretion was accompanied in both genotypes by increased renal expression of NaPi2a and NaPi2c, which was not present at ED 18.5. There was no compensatory increase by PTH when FGF23 or Klotho was absent.

In contrast to the slow emergence of hyperphosphatemia in Fgf23 null and Klotho null pups, excess FGF23 in Phex null males caused a reduction in serum phosphorus and a significant increase in urine phosphorus within 12 hours after birth. This was accompanied by reduced renal expression of NaPi2a and NaPi2c, as compared with no difference 24 hours earlier (ED 18.5). The early onset of the Phex null male phenotype shows that the neonatal kidneys are responsive to FGF23. The delayed onset of the Fgf23 null and Klotho null phenotypes was not due to compensatory secondary hyperparathyroidism.

The similar phenotype of Fgf23 null and Klotho null fetuses supports that Klotho mediates the actions of FGF23 as it does in adults, and that no other FGF family members compensate for absence of FGF23 during fetal life. Klotho nulls appeared to have an earlier onset of hyperphosphatemia (day 5 vs day 7) but whether this is a real or chance difference from the Fgf23 null phenotype is not certain; day 6 postnatal was not assessed. A possible difference in the fetal phenotype between the 2 models was the earlier finding of modestly reduced expression of Cyp24a1 in Fgf23 null in fetal kidneys (22), as compared with its normal expression in Klotho null kidneys. This might be an indication of a Klotho-independent action of FGF23 to regulate renal Cyp24a1 expression in utero. However, upon repeat assessment with new placentas from WT and Fgf23 nulls, and a larger sample size, we found Cyp24a1 expression was not reduced. Therefore, it appears that neither the absence of FGF23 or Klotho alter the expression of Cyp24a1, which is consistent with the lack of change in serum calcitriol in both genotypes.

Neonatal phosphorus metabolism was not extensively investigated in prior rodent studies. One report found that Fgf23 null pups were hyperphosphatemic on day 10 (41), and we have established that the disturbance begins by day 7. Phex null male mice were found to have normal serum phosphorus but increased PTH over the first 48 hours after birth, after which phosphorus became low and PTH normalized (42). We have found that within 12 hours after birth, excess FGF23 in Phex null male fetuses causes low serum phosphorus, increased renal phosphorus excretion, and reduced expression of NaPi2a and NaPi2c. Immediately prior to birth, serum phosphorus, renal phosphorus excretion into amniotic fluid, and renal expression of NaPi2a and NaPi2c, are all normal in Phex null male fetuses (22).

There have been no systematic studies of serum phosphorus or urine phosphorus excretion in human babies that are homozygous for mutations that lead to loss of biologically active FGF23 or Klotho; this is because their autosomal recessive inheritance leads to unexpected, sporadic appearance of affected offspring. However, the condition has presented as early as 18 days after birth with a calcific mass and hyperphosphatemia (43, 44). Whether serum phosphorus is normal at birth is not known but our studies in Fgf23 and Klotho null fetal mice suggest that phosphorus will be normal in cord blood of babies that have null mutations in FGF23, KLOTHO, and other genetic causes of hyperphosphatemic tumor calcinosis. In the opposite condition of FGF23 excess, such as occurs in X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets (XLH) due to a null mutation in PHEX, a positive family history of the condition has led to earlier diagnosis of affected babies. XLH can be diagnosed during the first year when family history leads to early detection of hypophosphatemia (45); otherwise, sporadic cases present later at 2 or 3 years of age with skeletal abnormalities (bowing of the long bones, growth failure, or short stature) (46–48). In 4 reported cases in which a family history of XLH led to early surveillance, serum phosphorus was low in all 4 between 2 and 6 weeks of age (45). Tubular reabsorption of phosphorus was reduced at 9 days of age in 1 affected baby but normal until 6 months in the others (45). Radiographic evidence of rickets began to appear between 3 and 6 months of age (45). These human data are consistent with phosphorus metabolism being normal at birth in XLH, as it is in Phex null male mice.

In the experiments reported in this paper, the pregnant mouse was heterozygous for the mutation, which conceivably could potentially influence the fetal phenotype. In our prior study (22) we also studied WT mothers and found that neither the maternal serum phosphorus (reduced in Phex+/− mothers and modestly increased in Fgf23+/− mothers) nor the maternal genotype (WT, Fgf23+/−, or Phex+/−) influenced the fetal serum phosphorus or fetal FGF23 concentration.

Why does loss of FGF23 or Klotho, or excess FGF23, fail to significantly alter fetal parameters of renal phosphorus excretion, serum phosphorus, placental phosphorus transport, and skeletal phosphorus content? A key factor is the placenta’s role to actively transport phosphorus and other minerals from the maternal circulation. This function is clearly not dependent upon FGF23, because neither loss of FGF23 nor Klotho altered placental phosphorus transport or the expression of any of the sodium-phosphate cotransporters. Postnatally, FGF23 acts primarily on the kidneys and to a lesser extent on the intestines to regulate phosphorus metabolism. But during fetal development the kidneys and intestines provide only a trivial route for mineral exchange, through amniotic fluid that is swallowed, absorbed, and then excreted again by the kidneys. Any phosphorus excreted by the fetal kidneys can be recycled after swallowing the amniotic fluid, and the magnitude of flux of phosphorus across the fetal kidneys is dwarfed by the magnitude of phosphorus exchange across the placenta. Additional studies have demonstrated that fetal kidneys have reduced glomerular filtration rate and blood flow compared with the neonate, and that maturational changes in these parameters after birth lead to an improved ability to reabsorb and excrete minerals (10).

The normally low concentrations of intact FGF23 in fetal mice of the C57BL/6 background may also be contributing to why absence of FGF23 or Klotho has no effect; in other words, low concentrations of FGF23 in normal fetal mice may imply that FGF23 is relatively unimportant for fetal mineral homeostasis. However, we found that fetal mice in the Black Swiss background have intact FGF23 concentrations equal to the maternal value (22), and another study found fetal intact FGF23 concentrations to equal maternal values in the C57BL/6 background (23). Moreover low levels of FGF23 in normal fetuses aren’t the sole explanation for why FGF23’s absence has no effect, because absence of Klotho did not disturb fetal serum FGF23 concentrations, whereas it led to 1000- to 5000-fold higher levels in neonates and adults (3, 39, 40). Taken together with the fact that high levels of FGF23 did not disturb fetal phosphorus parameters but begin to do so within 12 hours after birth, it is clear that the fetal-placental unit is unresponsive to FGF23 or loss of Klotho. The microarray studies in placentas of WT, Fgf23 null, and Phex null male placentas revealed no evidence of compensatory changes in phosphate-regulating or other genes. The lack of change in the phosphotrophic hormone PTH is further evidence that compensatory changes do not occur during fetal development when FGF23 or Klotho are absent, or when FGF23 excess is present. In a real sense, the fetus does not care about the loss of FGF23 signaling, nor about excess FGF23 signaling, whereas the neonate is adversely affected.

Our experiments do not rule out the potential importance of the sodium-phosphate cotransporters in regulating placental phosphorus transport, because their expression was normal in Klotho null, Fgf23 null, and Phex null male placentas. Instead, factors other than FGF23 must be regulating their expression during normal fetal development. Napi2b null mice die at midgestation (49), but whether this is due in part to altered placental phosphorus transport is unknown.

Overall, our results confirm that absence of Klotho or FGF23 do not disturb fetal phosphorus metabolism, nor does excess FGF23 significantly affect fetal phosphorus metabolism either (apart from a modest reduction in serum calcitriol). It is only after birth that disturbances in FGF23 signaling begin to significantly alter phosphorus homeostasis. Excess FGF23 exerts its effects as early as 12 hours after birth, whereas loss of Klotho or FGF23 have no effect until 5 to 7 days after birth. Our results predict that human babies with abnormalities of FGF23 signaling will be normal at birth, with disturbances in phosphorus metabolism beginning over the days to weeks or months after birth.

In conclusion, although intact FGF23 is present in the fetal circulation at levels that range from low to equal to adult values, and there is robust expression of FGF23 target genes in placenta and kidneys, FGF23 itself is not an important regulator of fetal phosphorous metabolism. Instead, factors other than FGF23 must dominate to regulate the transport of phosphorus across the placenta, and the expression of the sodium-phosphate cotransporters. The magnitude of phosphorus delivery across the placenta may override any effects that absence of FGF23 or Klotho, or excess of FGF23, might otherwise have on fetal kidneys. It is in the hours to days after loss of the placental phosphorus pump that FGF23 becomes an important regulator of renal phosphorus excretion and intestinal phosphorus absorption.

Acknowledgments

Presented in part at the Fourth Joint Meeting of the European Calcified Tissue Society and International Bone and Mineral Society, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015, and the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, Atlanta, Georgia, 2016.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grants 133413 and 126469), the Research and Development Corporation of Newfoundland (Grant 5404.1145.102), and the Discipline of Medicine at Memorial University (all to C.S.K.) and the National Institutes of Health (Grant DK097105 to B.L.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- CT

- threshold cycle

- Cyp24a1

- 24-hydroyxlase

- Cyp27b1

- 1-α-hydroxylase

- ED

- embryonic day

- FGF23

- fibroblast growth factor-23

- NaPi2a

- sodium-phosphate cotransporter 2a

- NaPi2c

- sodium-phosphate cotransporter 2c

- PCR

- polymerase chain reaction

- PTH

- parathyroid hormone

- PTHrP

- PTH-related protein

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative reverse transcription–PCR

- WT

- wild-type

- XLH

- X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets

References

- 1.Silver J, Naveh-Many T. FGF23 and the parathyroid glands. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25(11):2241–2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimada T, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki Y, Muto T, Hino R, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Nakahara K, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(3):429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuan Q, Sato T, Densmore M, Saito H, Schüler C, Erben RG, Lanske B. FGF-23/Klotho signaling is not essential for the phosphaturic and anabolic functions of PTH. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(9):2026–2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergwitz C, Jüppner H. Regulation of phosphate homeostasis by PTH, vitamin D, and FGF23. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:91–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wild R, Gerasimaite R, Jung JY, Truffault V, Pavlovic I, Schmidt A, Saiardi A, Jessen HJ, Poirier Y, Hothorn M, Mayer A. Control of eukaryotic phosphate homeostasis by inositol polyphosphate sensor domains. Science. 2016;352(6288):986–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hori M, Shimizu Y, Fukumoto S. Minireview: fibroblast growth factor 23 in phosphate homeostasis and bone metabolism. Endocrinology. 2011;152(1):4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsell R, Jonsson KB. The phosphate regulating hormone fibroblast growth factor-23. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2010;200(2):97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drezner MK. Phosphorus homeostasis and related disorders. In: Bilezikian JP, Raisz LG, and Martin TJ, eds. Principles of Bone Biology. 3rd ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2008:465–486. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alizadeh Naderi AS, Reilly RF. Hereditary disorders of renal phosphate wasting. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6(11):657–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovacs CS. Bone development and mineral homeostasis in the fetus and neonate: roles of the calciotropic and phosphotropic hormones. Physiol Rev. 2014;94(4):1143–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabbagh Y, Carpenter TO, Demay MB. Hypophosphatemia leads to rickets by impairing caspase-mediated apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(27):9637–9642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donohue MM, Demay MB. Rickets in VDR null mice is secondary to decreased apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Endocrinology. 2002;143(9):3691–3694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang R, Lu Y, Ye L, Yuan B, Yu S, Qin C, Xie Y, Gao T, Drezner MK, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ. Unique roles of phosphorus in endochondral bone formation and osteocyte maturation. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(5):1047–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omelon S, Georgiou J, Henneman ZJ, Wise LM, Sukhu B, Hunt T, Wynnyckyj C, Holmyard D, Bielecki R, Grynpas MD. Control of vertebrate skeletal mineralization by polyphosphates. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovacs CS, Manley NR, Moseley JM, Martin TJ, Kronenberg HM. Fetal parathyroids are not required to maintain placental calcium transport. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(8):1007–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovacs CS, Chafe LL, Fudge NJ, Friel JK, Manley NR. PTH regulates fetal blood calcium and skeletal mineralization independently of PTHrP. Endocrinology. 2001;142(11):4983–4993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simmonds CS, Karsenty G, Karaplis AC, Kovacs CS. Parathyroid hormone regulates fetal-placental mineral homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(3):594–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simmonds CS, Kovacs CS. Role of parathyroid hormone (PTH) and PTH-related protein (PTHrP) in regulating mineral homeostasis during fetal development. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2010;20(3):235–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovacs CS, Woodland ML, Fudge NJ, Friel JK. The vitamin D receptor is not required for fetal mineral homeostasis or for the regulation of placental calcium transfer in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289(1):E133–E144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieben L, Stockmans I, Moermans K, Carmeliet G. Maternal hypervitaminosis D reduces fetal bone mass and mineral acquisition and leads to neonatal lethality. Bone. 2013;57(1):123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshiko Y, Wang H, Minamizaki T, Ijuin C, Yamamoto R, Suemune S, Kozai K, Tanne K, Aubin JE, Maeda N. Mineralized tissue cells are a principal source of FGF23. Bone. 2007;40(6):1565–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma Y, Samaraweera M, Cooke-Hubley S, Kirby BJ, Karaplis AC, Lanske B, Kovacs CS. Neither absence nor excess of FGF23 disturbs murine fetal-placental phosphorus homeostasis or prenatal skeletal development and mineralization. Endocrinology. 2014;155(5):1596–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohata Y, Yamazaki M, Kawai M, Tsugawa N, Tachikawa K, Koinuma T, Miyagawa K, Kimoto A, Nakayama M, Namba N, Yamamoto H, Okano T, Ozono K, Michigami T. Elevated fibroblast growth factor 23 exerts its effects on placenta and regulates vitamin D metabolism in pregnancy of Hyp mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(7):1627–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takaiwa M, Aya K, Miyai T, Hasegawa K, Yokoyama M, Kondo Y, Kodani N, Seino Y, Tanaka H, Morishima T. Fibroblast growth factor 23 concentrations in healthy term infants during the early postpartum period. Bone. 2010;47(2):256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohata Y, Arahori H, Namba N, Kitaoka T, Hirai H, Wada K, Nakayama M, Michigami T, Imura A, Nabeshima Y, Yamazaki Y, Ozono K. Circulating levels of soluble alpha-Klotho are markedly elevated in human umbilical cord blood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(6):E943–E947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ali FN, Josefson J, Mendez AJ, Mestan K, Wolf M Cord blood ferritin and fibroblast growth factor-23 levels in neonates. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(4):1673–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sitara D, Razzaque MS, Hesse M, Yoganathan S, Taguchi T, Erben RG, Jüppner H, Lanske B. Homozygous ablation of fibroblast growth factor-23 results in hyperphosphatemia and impaired skeletogenesis, and reverses hypophosphatemia in Phex-deficient mice. Matrix Biol. 2004;23(7):421–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, Ohyama Y, Kurabayashi M, Kaname T, Kume E, Iwasaki H, Iida A, Shiraki-Iida T, Nishikawa S, Nagai R, Nabeshima YI. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390(6655):45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miao D, He B, Karaplis AC, Goltzman D. Parathyroid hormone is essential for normal fetal bone formation. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(9):1173–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakatani T, Sarraj B, Ohnishi M, Densmore MJ, Taguchi T, Goetz R, Mohammadi M, Lanske B, Razzaque MS. In vivo genetic evidence for klotho-dependent, fibroblast growth factor 23 (Fgf23) -mediated regulation of systemic phosphate homeostasis. FASEB J. 2009;23(2):433–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan Q, Sitara D, Sato T, Densmore M, Saito H, Schüler C, Erben RG, Lanske B. PTH ablation ameliorates the anomalies of Fgf23-deficient mice by suppressing the elevated vitamin D and calcium levels. Endocrinology. 2011;152(11):4053–4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovacs CS, Lanske B, Hunzelman JL, Guo J, Karaplis AC, Kronenberg HM. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) regulates fetal-placental calcium transport through a receptor distinct from the PTH/PTHrP receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(26):15233–15238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodrow JP, Sharpe CJ, Fudge NJ, Hoff AO, Gagel RF, Kovacs CS. Calcitonin plays a critical role in regulating skeletal mineral metabolism during lactation. Endocrinology. 2006;147(9):4010–4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirby BJ, Ardeshirpour L, Woodrow JP, Wysolmerski JJ, Sims NA, Karaplis AC, Kovacs CS. Skeletal recovery after weaning does not require PTHrP. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(6):1242–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4(2):249–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jain N, Thatte J, Braciale T, Ley K, O’Connell M, Lee JK. Local-pooled-error test for identifying differentially expressed genes with a small number of replicated microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(15):1945–1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bai X, Dinghong Q, Miao D, Goltzman D, Karaplis AC. Klotho ablation converts the biochemical and skeletal alterations in FGF23 (R176Q) transgenic mice to a Klotho-deficient phenotype. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296(1):E79–E88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan Q, Sato T, Densmore M, Saito H, Schüler C, Erben RG, Lanske B. Deletion of PTH rescues skeletal abnormalities and high osteopontin levels in Klotho-/- mice. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(5):e1002726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimada T, Kakitani M, Yamazaki Y, Hasegawa H, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Tomizuka K, Yamashita T. Targeted ablation of Fgf23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(4):561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bai X, Miao D, Goltzman D, Karaplis AC. Early lethality in Hyp mice with targeted deletion of Pth gene. Endocrinology. 2007;148(10):4974–4983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slavin RE, Wen J, Barmada A. Tumoral calcinosis—a pathogenetic overview: a histological and ultrastructural study with a report of two new cases, one in infancy. Int J Surg Pathol. 2012;20(5):462–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Polykandriotis EP, Beutel FK, Horch RE, Grünert J. A case of familial tumoral calcinosis in a neonate and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(8):563–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moncrieff MW. Early biochemical findings in familial hypophosphataemic, hyperphosphaturic rickets and response to treatment. Arch Dis Child. 1982;57(1):70–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carpenter TO. The expanding family of hypophosphatemic syndromes. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012;30(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santos F, Fuente R, Mejia N, Mantecon L, Gil-Peña H, Ordoñez FA. Hypophosphatemia and growth. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28(4):595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ekpebegh CO, Blanco-Blanco E. Familial hypophosphataemic rickets affecting a father and his two daughters: a case report. West Afr J Med. 2010;29(4):271–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shibasaki Y, Etoh N, Hayasaka M, Takahashi MO, Kakitani M, Yamashita T, Tomizuka K, Hanaoka K. Targeted deletion of the tybe IIb Na(+)-dependent Pi-co-transporter, NaPi-IIb, results in early embryonic lethality. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381(4):482–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]