Abstract

Previous studies suggest that bone loss and fracture risk are associated with higher inflammatory milieu, potentially modifiable by diet. The primary objective of this analysis was to evaluate the association of the dietary inflammatory index (DII), a measure of the inflammatory potential of diet, with risk of hip, lower-arm, and total fracture using longitudinal data from the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study and Clinical Trials. Secondarily, we evaluated changes in bone mineral density (BMD) and DII scores. DII scores were calculated from baseline food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) completed by 160,191 participants (mean age 63 years) without history of hip fracture at enrollment. Year 3 FFQs were used to calculate a DII change score. Fractures were reported at least annually; hip fractures were confirmed by medical records. Hazard ratios for fractures were computed using multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazard models, further stratified by age and race/ethnicity. Pairwise comparisons of changes in hip BMD, measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry from baseline, year 3, and year 6 were analyzed by quartile (Q1 = least inflammatory diet) of baseline DII scores in a subgroup of women (n = 10,290). Mean DII score improved significantly over 3 years (p < 0.01), but change was not associated with fracture risk. Baseline DII score was only associated with hip fracture risk in younger white women (HR Q4,1.48; 95% CI, 1.09 to 2.01; p = 0.01). There were no significant associations among white women older than 63 years or other races/ethnicities. Women with the least inflammatory DII scores had less loss of hip BMD (p = 0.01) by year 6, despite lower baseline hip BMD, versus women with the most inflammatory DII scores. In conclusion, a less inflammatory dietary pattern was associated with less BMD loss in postmenopausal women. A more inflammatory diet was associated with increased hip fracture risk only in white women younger than 63 years.

Keywords: NUTRITION, OSTEOPOROSIS, FRACTURE RISK ASSESSMENT, EPIDEMIOLOGY, MENOPAUSE

Introduction

Chronic inflammation is associated with increased risk of several age-related diseases, including osteoporosis and fragility fractures.(1–3) Higher levels of serum inflammatory markers predict bone loss and increased bone resorption in older adults.(3) More important, data from large, prospective epidemiological studies(1) indicate that higher serum inflammatory markers are associated with greater risk of fractures in older women and men. These studies offer compelling evidence that chronic inflammation is related to adverse skeletal outcomes.

Dietary components have been shown to modify inflammation through both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mechanisms.(4–6) However, a single food or nutrient may not be sufficient to reduce fracture risk in postmenopausal women.(7,8) Describing the functional effects of combinations of foods as they are eaten by free-living humans and as they describe inflammation has proven to be effective at predicting disease outcomes.(9) Previous research has shown that the overall dietary pattern or diet quality may be more relevant to disease risk than intake of individual foods or nutrients.(10–12) Diet quality, as measured by various instruments, has been associated with markers of inflammation such as C-reactive protein (CRP).(13–15) Additionally, a growing body of research suggests that higher-quality dietary patterns are favorably associated with bone mineral density (BMD)(16–18) and fracture risk(19) in older adults. However, it is unknown if a dietary pattern that is associated with more inflammation will increase fracture risk in older adults.

The Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) was developed to assess the overall quality of the diet on a continuum from maximally anti-inflammatory to maximally pro-inflammatory.(14,20) This index was created by assigning a score for each food and constituent (eg, nutrients and other parameters, including flavonoids) reported to positively or negatively affect levels of specific inflammatory markers (interleukin-1β [IL-1β], IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNFα], and CRP) using the available evidence from over 1900 relevant peer-reviewed journal articles. The DII was designed to quantify the overall effect of diet on inflammation, using weighted scores based on quality of study design, type of study (eg, cell, animal, human) and number of published articles for each food component–inflammatory biomarker relationship that comprise the DII. An important unique design feature of the DII is that it is not dependent on recommendations of intake or findings from single population means. Rather, it is based on results published in scientific literature and then standardized to global values of intake for all DII food parameters. Recently, the DII has been updated to incorporate studies published from 2007 to 2010.(20) The DII has been assessed relative to biomarkers of inflammation: using high-sensitivity CRP in a longitudinal study of healthy adults(21) and using CRP, TNFα receptor 2 (TNF-R2) and IL-6 in a subset of participants in the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) Observational Study (WHI-OS).(22) Specifically, in the WHI validation study, a higher inflammatory score on the DII predicted higher serum IL-6 and higher TNF-R2 (beta estimate, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.38; p for trend <0.0001 and beta estimate, 81.43; 95% CI, 19.15 to 143.71; p for trend = 0.004, respectively). The DII also has been used in several large cohorts, including the WHI, to investigate relationships between diet quality related to inflammation and various outcomes, including metabolic syndrome, asthma, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer.(9,23–26) There has been one recent report of a beneficial association with BMD of the lumbar spine and a less inflammatory DII score in a small, cross-sectional cohort of Iranian women(27); thus far, no one has investigated the impact of the DII in relation to longitudinal changes in BMD or fracture, the final, debilitating clinical outcome of osteoporosis.

The primary objective of this analysis was to evaluate the association of an inflammatory diet pattern, as represented by baseline DII score, with risk of fracture (defined as hip, lower-arm, and total fracture) using longitudinal data from the WHI. We also tested for effect modification by age and race/ethnicity, as well as by calcium intake. Our secondary objectives were (1) to examine the association of change in DII scores from baseline to year 3 with risk of fractures and (2) to examine the relation of DII score to changes in BMD over 6 years of follow-up. Because fractures were one of the main outcome measures when the WHI was originally designed, and nutritional data as well as BMD data were collected in a large subset of the cohort,(28) this offers a unique opportunity to examine exposure to an inflammatory diet pattern and risk of fracture and explore underlying mechanistic pathways involving BMD.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

The WHI is the largest study of postmenopausal women's health ever undertaken in the United States. The focus of the WHI is on prevention and control of common diseases impacting older women, including osteoporotic fractures. Details of the study design and methods have been published.(28) Briefly, ethnically and racially diverse women (n = 161,808) between 50 and 79 years of age were enrolled between 1993 and 1998. Of these, 68,132 women joined one or more of the three randomized clinical trials (CT): (1) placebo-controlled hormone therapy (HT) trials with estrogen alone or estrogen plus progestin; (2) a low-fat dietary modification (DM) trial compared with usual diet; and (3) a calcium plus vitamin D supplement (CaD) trial compared with placebo. Women who were not eligible or interested in the clinical trials (n = 93,676) enrolled in the observational study (OS). Procedures were reviewed and approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee at each of the 40 participating clinical centers nationwide, at which participants provided written informed consent. The study population for this analysis included women from both the OS and CT who completed a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) at baseline from which a DII score was calculated (n = 161,595). We excluded women who reported history of hip fracture at baseline (n = 1404). A total of 160,191 participants constituted the analytic dataset. BMD data for this analysis were from the subgroup of 10,290 OS and CT women who had serial measurements at baseline, year 3, and year 6. The BMD cohort was oversampled for ethnic/racial minorities and, therefore, is not representative of WHI as a whole.

Calculation of the DII

The development of the original DII and the revised version have been described.(10,16) Briefly, to develop the latest DII, scientific literature published through 2010 was reviewed for relationships between food components or “parameters” and specific inflammatory markers. Positive or negative values were assigned to each article based on the effect of the food parameter on inflammation (ie, +1 = pro-inflammatory relationship, 0 = no significant relationship with inflammatory marker, –1 = anti-inflammatory relationship). Articles were weighted by quality of study design and type of study (eg, cell study = 3, human experimental = 10). An inflammatory effect score for each food parameter was calculated based on the number of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory articles and adjusted based on the total weighted number of articles. To avoid over or under estimation of any one food parameter on overall score, an individual's dietary intake was standardized to mean intakes from a global composite dataset created for this purpose and converted to percentiles for calculation of an overall DII score.(16) The DII was designed to assess the overall inflammatory potential of the diet; it was not intended for use in evaluating individual food components included in the index and relationship of those individual components with health outcomes.

In this analysis, the DII was calculated for each participant based on 32 food components (Table 1) obtained from the WHI FFQ responses that assessed usual food intake in the previous 3 months and data on use of the following dietary supplements: iron, magnesium, niacin, riboflavin, selenium, thiamine, beta carotene, zinc, folic acid, and vitamins A, C, D, E, B6, and B12.(29) The original DII contained 45 food components, but the following components were not available in the WHI FFQ: ginger, turmeric, garlic, oregano, pepper, rosemary, eugenol, saffron, flavan-3-ol, flavones, flavonols, flavonones, and anthocyanidins.(22) Because these components are typically consumed in small quantities in most of the population, previous studies, including the WHI, indicate that their absence has virtually no effect on DII scores.(21,22) DII scores for the baseline WHI FFQ were used for primary analyses in this research. DII scores computed from FFQ data in year 3 of WHI also were used to secondarily examine change in dietary pattern in relation to fracture risk. In order to examine relationships between different levels of DII scores and outcomes of interest, we divided the DII into quartiles with the following cut points: Q1: –7.05 to ≤ –2.81; Q2: > –2.81 to ≤ –1.21; Q3: > –1.21 to ≤ 1.49; and Q4: >1.49 to 5.78. A higher range of DII scores (eg, Q4) represents a more inflammatory diet pattern.

Table 1.

Components of the Dietary Inflammatory Index Available in the WHI Food Frequency Questionnaire

| DII component | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Alcohol, g |

| 2 | Vitamin B12, μg |

| 3 | Vitamin B6, mg |

| 4 | Beta carotene, μg |

| 5 | Caffeine, g |

| 6 | Carbohydrate, g |

| 7 | Cholesterol, mg |

| 8 | Energy, kcal |

| 9 | Total fat, g |

| 10 | Fiber, g |

| 11 | Folic acid, mg |

| 12 | Iron, mg |

| 13 | Magnesium, mg |

| 14 | MUFA, g |

| 15 | Niacin, mg |

| 16 | Omega 3, g |

| 17 | Omega 6, g |

| 18 | Onion, g |

| 19 | Protein, g |

| 20 | PUFA, g |

| 21 | Riboflavin, mg |

| 22 | Saturated fat, g |

| 23 | Selenium, mg |

| 24 | Thiamin, mg |

| 25 | Trans fat, g |

| 26 | Vitamin A, μg |

| 27 | Vitamin C, mg |

| 28 | Vitamin D, μg |

| 29 | Vitamin E, mg |

| 30 | Zinc, mg |

| 31 | Green tea/black tea, g |

| 32 | Isoflavones, mg |

WHI = Women's Health Initiative; DII = Dietary inflammatory index; MUFA = monounsaturated fatty acid; PUFA = polyunsaturated fatty acid.

Fracture and BMD ascertainment

Data on incident fractures were self-reported by participants on a health update questionnaire, collected every 6 months, either at clinic visit or by mail or phone for women in the CTs. OS participants completed the questionnaires by mail or phone annually. Proxy interviews were conducted for women who missed clinic visits or were unable to complete questionnaires alone. Medical records (radiology, surgery reports) were requested for all hip fractures in the entire WHI cohort, and for all fractures reported in the clinical trials and at the three BMD centers. Total fractures were defined as all fractures except those of fingers, toes, ribs, sternum/chest, skull/face, and cervical vertebrae. Hip fractures were centrally adjudicated by trained and blinded physicians. There was 96% agreement between central and local adjudication of hip fractures.(30) Additionally, 81% of self-reported lower-arm/wrist fractures and 71% of all single-site fractures were confirmed in a subset of WHI participants (n = 6652) after an average of 4.3 years of follow-up(31); however, validity of self-reported clinical spine fractures was relatively low (51%) in this same subset, therefore, we chose not to include spine fractures as an outcome in this analysis.

BMD of the total hip, lumbar spine (L2-L4), and total body was measured in women at three participating US clinical centers (Birmingham, AL; Tucson/Phoenix, AZ; and Pittsburgh, PA) using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (QDR 2000, 2000+, or 4500 W; Hologic Inc, Bedford, MA, USA). BMD data were obtained by certified technicians using standard protocols(32) at baseline randomization and at annual visits in years 3, 6, and 9. WHI quality assurance protocols included routine spine and hip phantoms and a random sample review. Calibration phantoms between the three clinical sites were in close agreement (interscanner variability <1.5% for the spine, <4.8% for the hip, and <1.7% for linearity).(32,33)

Covariate measurement

Covariates, selected based on previously defined impact on fracture risk, BMD, or inflammation, included age, race/ethnicity, CT participation, parental history of fracture, personal history of fracture at 55 years or older, smoking status (current, never, past), physical activity (recreational activity assessed by questionnaire and expressed as Metabolic Equivalents), geographical region, treated diabetes, female hormone use, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or corticosteroid use, total calcium intake (diet plus supplements) at baseline, randomization to CaD treatment arm, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and baseline weight and height. We did not include dietary variables such as alcohol and personal vitamin D supplement use as covariates because they were included as part of the DII calculation.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics by baseline DII quartiles were performed using ANOVA for continuous variables and chi square test for categorical variables. We used Cox proportional hazards regression model to determine the association between DII quartiles at baseline and risk of fracture at various sites (total fracture, lower-arm fracture, and hip fracture). Three models were examined: unadjusted, age- and race-adjusted, and a fully adjusted model, which included all covariates described in Covariate measurement. In order to examine the effect of energy intake on fracture risk, analyses were repeated with a modified DII score that did not include energy, and then models were adjusted for total energy intake (kcal/day). Results did not change appreciably; therefore, results of analyses using the original DII score with daily energy intake included are shown. We also evaluated the relationship of the DII to fracture outcomes using a continuous scale. Among women who experienced fracture, follow-up duration was defined as time to first fracture. For women who did not experience fracture during the follow-up period (ie, through September 30, 2010), follow-up duration was defined as time until last follow-up visit, or death, whichever came first.

Multiple imputations using discriminant function method were performed in order to assess the impact of the large amount of missing responses to questions about personal and parental history of fracture. The same imputed data sets (n = 10) were used in fitting both Cox models and linear mixed regression models. All p values are two-sided, and 95% CIs are provided to indicate precision and statistical significance. SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used in all analyses.

We tested the assumption that the hazard ratio of the primary predictor remained constant over time by introducing a cross-product term for DII*log (time) into the statistical model. The proportionality assumption was not violated. For all models, there were no significant two-way interactions with any of the covariates and DII quartiles. Tests for linear trend were performed using standard orthogonal contrasts. We examined effect modification by stratifying according to calcium intake (because of the large difference in calcium intake between women in different quartiles of the DII) and by age and race (because of changing direction of association in some Cox models when these covariates were included). In addition, we performed several sensitivity analyses: (1) excluding women in the treatment arm of the DM clinical trial; (2) excluding women who fractured after the end date (2005) of the original WHI studies; and (3) excluding women in the treatment arm of the HT trial or those using medications known to affect bone.

To address our secondary aims, a paired t test was used to compare the baseline DII score versus DII score at year 3. Cox models were used to determine the association between change in DII quartiles and risk of fracture at various sites, using the same covariates as in the fracture models. Incident fractures occurring before year 3 were excluded from the change in DII analysis. Linear mixed regression models were fitted with DII quartiles as predictors and BMD (percent change from baseline: [(follow-up BMD – baseline BMD)/baseline BMD]*100) as the primary outcome to examine the association of DII score to change in BMD over time. This allowed us to normalize all BMD data to baseline. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons.

Results

Participant characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the study population by quartiles (Q) of the DII score are reported in Table 2. WHI participants were 50 to 79 years old at enrollment; average age of participants in this sample was 63 years old. A total of 47,974 incident fracture cases, including 3837 centrally adjudicated hip fracture cases were identified in the CT and OS as of September 30, 2010. Mean ± SD length of follow-up was 11.4 ± 3.3 years. The range of DII scores in the study population at baseline was from –7.0 to 5.8, with a mean ± SD of –0.7 ± 2.7; a lower number indicates a less inflammatory dietary pattern. Compared to Q1, women in Q4 (a more inflammatory diet) were younger, more likely to be black or Hispanic, be current smokers, be treated for diabetes, report less physical activity and fewer falls, have lower total calcium intake, and a higher BMI (BMI Q1: 27.25 versus Q4: 28.86 kg/m2). Fewer women in Q4 were taking female hormones and fewer reported a family history of fractures or a personal fracture at ≥55 years of age.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants by Dietary Inflammatory Index Score

| Demographics | Total (n) | Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT participant, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 92694 | 26535 (66) | 23184 (58) | 22004 (55) | 20971 (52) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 67412 | 13449 (34) | 16815 (42) | 18054 (45) | 19094 (48) | |

| Total | 160106 | 39984 | 39999 | 40058 | 40065 | |

| Age, n (%) | ||||||

| <63 years | 75811 | 17737 (44) | 18041 (45) | 19257 (48) | 20776 (52) | <0.0001 |

| >63 years | 84295 | 22247 (56) | 21958 (55) | 20801 (52) | 19289 (48) | |

| Total | 160106 | 39984 | 39999 | 40058 | 40065 | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 132072 | 34814 (87) | 34539 (87) | 33042 (83) | 29677 (74) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 14512 | 1994 (5) | 2744 (7) | 3585 (9) | 6189 (15) | |

| Hispanic | 6417 | 925 (2) | 1258 (3) | 1688 (4) | 2546 (6) | |

| Asian/Pacific | 4166 | 1571 (4) | 804 (2) | 1009 (3) | 782 (2) | |

| Other | 2531 | 594 (1) | 557 (1) | 632 (2) | 748 (2) | |

| Total | 159698 | 39898 | 39902 | 39956 | 39942 | |

| Parental fracture, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 89209 | 21884 (59) | 22005 (60) | 22442 (61) | 22878 (63) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 58402 | 15283 (41) | 14965 (40) | 14594 (39) | 13560 (37) | |

| Total | 147611 | 37167 | 36970 | 37036 | 36438 | |

| Fracture ≥55 years old, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||||

| No | 102620 | 25970 (83) | 25810 (83) | 25580 (85) | 25260 (86) | |

| Yes | 19256 | 5320 (17) | 5122 (17) | 4675 (15) | 4139 (14) | |

| Total | 121876 | 31290 | 30932 | 30255 | 29399 | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||||

| Never smoked | 80570 | 19913 (50) | 20257 (51) | 20313 (51) | 20087 (51) | |

| Past smoker | 66426 | 17983 (46) | 16747 (42) | 16462 (42) | 15234 (39) | |

| Current smoker | 11015 | 1581 (4) | 2499 (6) | 2771 (7) | 4164 (11) | |

| Total | 158011 | 39477 | 39503 | 39546 | 39485 | |

| Physical activity, n (%)a | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0–3 | 43626 | 7003 (18) | 10400 (26) | 11370 (28) | 14853 (37) | |

| >3 to <11.75 | 55437 | 12560 (31) | 14046 (35) | 14458 (36) | 14373 (36) | |

| ≥11.75 | 60864 | 20390 (51) | 15502 (39) | 14185 (35) | 10787 (27) | |

| Total | 159927 | 39953 | 39948 | 40013 | 40013 | |

| Region, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||||

| Northeast | 36461 | 9257 (23) | 9364 (23) | 9049 (23) | 8791 (22) | |

| South | 41482 | 8954 (22) | 9883 (25) | 10405 (26) | 12240 (31) | |

| Midwest | 35241 | 8261 (21) | 9021 (23) | 9166 (23) | 8793 (22) | |

| West | 46922 | 13512 (34) | 11731 (29) | 11438 (29) | 10241 (26) | |

| Total | 160106 | 39984 | 39999 | 40058 | 40065 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||||

| No | 150475 | 37829 (95) | 37845 (95) | 37496 (94) | 37305 (93) | |

| Yes | 9521 | 2127 (5) | 2130 (5) | 2533 (6) | 2731 (7) | |

| Total | 159996 | 39956 | 39975 | 40029 | 40036 | |

| Female hormones, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||||

| No | 52008 | 11205 (29) | 12177 (31) | 13396 (34) | 15230 (39) | |

| Yes | 103955 | 27991 (71) | 26860 (69) | 25499 (66) | 23605 (61) | |

| Total | 155963 | 39196 | 39037 | 38895 | 38835 | |

| Number of falls, n (%) | ||||||

| None | 103686 | 25601 (66) | 26008 (67) | 25774 (67) | 26303 (69) | <0.0001 |

| 1 time | 30742 | 8119 (21) | 7819 (20) | 7673 (20) | 7131 (19) | |

| 2 times | 12734 | 3373 (9) | 3236 (8) | 3179 (8) | 2946 (8) | |

| 3 or more times | 6402 | 1781 (5) | 1553 (4) | 1566 (4) | 1502 (4) | |

| Total | 153564 | 38874 | 38616 | 38192 | 37882 | |

| NSAIDs, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||||

| No | 129523 | 32289 (81) | 31786 (79) | 32510 (81) | 32938 (82) | |

| Yes | 30581 | 7693 (19) | 8213 (21) | 7548 (19) | 7127 (18) | |

| Total | 160104 | 39982 | 39999 | 40058 | 40065 | |

| Corticosteroids, n (%) | 0.874 | |||||

| No | 159005 | 39720 (99) | 39716 (99) | 39782 (99) | 39787 (99) | |

| Yes | 1101 | 264 (1) | 283 (1) | 276 (1) | 278 (1) | |

| Total | 160106 | 39984 | 39999 | 40058 | 40065 | |

| Calcium (mg), n (%)b | <0.0001 | |||||

| <800 | 56720 | 3532 (9) | 8878 (22) | 14624 (37) | 29686 (74) | |

| 800 to <1200 | 38827 | 8539 (21) | 11208 (28) | 12558 (31) | 6522 (16) | |

| ≥1200 | 64559 | 27913 (70) | 19913 (50) | 12876 (32) | 3857 (10) | |

| Total | 160106 | 39984 | 39999 | 40058 | 40065 | |

| BMI (kg/m2), n (%) | <0.0001 | |||||

| <18.5 | 1352 | 422 (1) | 313 (1) | 331 (1) | 286 (1) | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 54019 | 15830 (40) | 13792 (35) | 12812 (32) | 11585 (29) | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 54900 | 13417 (34) | 13809 (35) | 13830 (35) | 13844 (35) | |

| 30.0–34.9 | 29280 | 6239 (16) | 7214 (18) | 7613 (19) | 8214 (21) | |

| 35.0–39.9 | 11993 | 2412 (6) | 2858 (7) | 3218 (8) | 3505 (9) | |

| ≥40 | 6330 | 1181 (3) | 1447 (4) | 1700 (5) | 2002 (5) | |

| DII score, mean ± SDc | −3.8 ± 0.7 | −2.1 ± 0.4 | 0.08 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | <0.0001 | |

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 71.7 ± 16.3 | 73.3 ± 16.6 | 74.2 ± 17.0 | 75.0 ± 17.4 | <0.0001 | |

| Height (cm), mean ± SD | 162.2 ± 6.5 | 161.8 ± 6.6 | 161.7 ± 6.7 | 161.2 ± 6.7 | <0.0001 |

Baseline dietary inflammatory index score: quartile 1, least inflammatory; quartile 4, most inflammatory.

CT = clinical trial assignment; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; DII = Dietary Inflammatory Index.

Recreational activity in metabolic equivalents (METS).

Calcium intake from diet plus supplements; 72% of women reported calcium supplement use.

The range of DII scores in the study population was −7.0 to 5.8 at baseline.

DII and fracture outcomes

Table 3 details Cox proportional hazard ratios (HRs) for risk of fracture at various skeletal sites based on quartiles of the DII at baseline. Women with high DII (more inflammatory) scores had a significantly higher risk of hip fracture in models adjusted for age and race (Q4 HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.23; p for linear trend 0.02); however, the association was no longer significant after multivariable adjustment. Conversely, in fully adjusted models for lower-arm fracture and total fracture, risk decreased by 8% (p for linear trend 0.02) and 5% (p for linear trend <0.01), respectively, in women with the most inflammatory diet. Similar results were seen when risk of fracture by DII score was evaluated on a continuous scale. Results are shown in Supporting Table 1. We found no evidence of interaction or mediation by any of the covariates in the model. Although we controlled for multiple covariates in our statistical models, we did not include falls because falls are in the causal pathway for fractures. However, we did test for an association of DII score and risk of falls, and found a 7% lower risk in women with the most inflammatory score (HR Q4 vs Q1, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.92 to 0.95; p for trend <0.001).

Table 3.

Cox Proportional Hazard Ratios for Association Between Baseline DII and Risk of Fracture in WHI

| Variables | Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | p linear trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | −3.63 (−4.22 to −3.19) | −2.10 (−2.46 to −1.70) | 0.07 (−0.62 to 0.77) | 2.98 (2.22 to 3.86) | |

| Cutoff points | [−7.05, −2.81] | [−2.81, −1.21] | [−1.21, 1.49] | [1.49, 5.78] | |

| Hip fracture | |||||

| Non-cases, n (%) | 39,000 (97.54) | 38,976 (97.44) | 39,087 (97.58) | 39,189 (97.81) | |

| Hip fracture, n (%) | 984 (2.46) | 1023 (2.56) | 971 (2.42) | 876 (2.19) | |

| Unadjusted HR, 95% CIa | 1 | 1.04 (0.96–1.14) | 0.98 (0.90–1.07) | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) | 0.042 |

| Age-, race-adjusted HR, 95% CIb | 1 | 1.06 (0.97–1.15) | 1.06 (0.97–1.15) | 1.12 (1.02–1.23) | 0.017 |

| Multivariable-adjusted HR, 95% CIc | 1 | 1.03 (0.95–1.13) | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 1.02 (0.92–1.14) | 0.709 |

| Lower arm fracture | |||||

| Non-cases, n (%) | 37,208 (93.06) | 37,369 (93.42) | 37,511 (93.64) | 38,739 (94.19) | |

| Lower arm fracture, n (%) | 2776 (6.94) | 2630 (6.58) | 2547 (6.36) | 2326 (5.81) | |

| Unadjusted HR, 95% CIa | 1 | 0.95 (0.90–1.00) | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) | 0.86 (0.81–0.91) | <0.001 |

| Age-, race-adjusted HR, 95% CIb | 1 | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) | 0.94 (0.90–1.00) | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) | 0.028 |

| Multivariable-adjusted HR, 95% CIc | 1 | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) | 0.94 (0.89–1.00) | 0.92 (0.86–0.98) | 0.016 |

| Total fracture | |||||

| Non-cases, n (%) | 28,803 (72.30) | 29,050 (72.97) | 29,278 (73.51) | 30,075 (75.64) | |

| Total fracture, n (%) | 11,037 (27.70) | 10,759 (27.03) | 10,550 (26.49) | 9687(24.36) | |

| Unadjusted HR, 95% CIa | 1 | 0.98 (0.95–1.00) | 0.95 (0.93–0.98) | 0.89 (0.87–0.92) | <0.001 |

| Age-, race-adjusted HR, 95% CIb | 1 | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.98 (0.95–1.00) | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | 0.031 |

| Multivariable-adjusted HR, 95% CIc | 1 | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 0.95 (0.92–0.98) | 0.002 |

Baseline Dietary Inflammatory Index Score: quartile 1, least inflammatory; quartile, 4 most inflammatory.

DII = Dietary Inflammatory Index; WHI, Women's Health Initiative; IQR = interquartile range; CT = clinical trial assignment; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; CaD = calcium plus vitamin D supplement.

Includes DII only.

Includes age, race, and DII.

Includes age, race, DII (baseline), CT, parental history of fracture, personal history of fracture at age 55 years or older, smoking, physical activity, region, diabetes, female hormone use, NSAID use, total calcium intake, randomization arm in CaD trial, corticosteroid use (screening), inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, weight, and height. Imputed values were used for covariates “parental history of fracture” and “personal history of fracture at age 55 years or older” because of the large number of missing values.

Because of the large difference in calcium consumption between women in highest and lowest DII quartiles, we stratified women by daily calcium intake from diet plus supplements and then constructed fully adjusted Cox models to determine the association of DII quartiles and fracture by strata (Supporting Table 2). Risk for lower-arm fracture decreased significantly only for women who were consuming at least 1200 mg of calcium per day and had a more pro-inflammatory DII score (Q4 HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.76 to 1.00; p for linear trend 0.05); a similar, but nonsignificant association was noted for total fracture risk. In contrast, there was a trend toward increased risk of hip fracture in women consuming a more inflammatory dietary pattern plus at least 1200 mg of calcium per day, but this association did not reach statistical significance (Q4 HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.45; p for linear trend 0.12). No statistically significant interaction was observed for calcium and the DII in any of the fracture models (calcium*DII interaction p values: 0.14 hip, 0.43 lower-arm, 0.78 total fracture).

To further investigate the influence of consuming an inflammatory diet on fracture risk in younger versus older women of varying races, we stratified our sample by median age (63 years) and race/ethnicity (white versus other). Results of fully adjusted Cox models are presented in Table 4. Risk for hip fracture significantly increased in women in the most inflammatory diet quartile who were younger than 63 years and white (Q4 HR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.09 to 2.01; p for linear trend 0.01); a similar direction of association was seen in women younger than 63 years old of other races/ethnicities consuming more inflammatory diets, but confidence intervals were wide and there was no significant linear trend (Q4 HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 0.42 to 4.12; p for linear trend 0.51). In contrast, there was no evidence of association in older women, with the exception that a statistically significant linear trend (p = 0.03) toward a very modest decreased risk of total fractures was observed in women consuming more inflammatory diets who were 63 years or older and white, though none of the individual HRs in upper quartiles were less than 0.95 or statistically significant.

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazard Ratios for Association Between Baseline DII and Risk of Fracture Stratified by Age and Race/Ethnicity

| Variables | Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 HR (95% CI) | Quartile 3 HR (95% CI) | Quartile 4 HR (95% CI) | p linear trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hip fracture | |||||

| Age <63 years, Race = white | 1 | 1.28 (0.99–1.66) | 1.30 (0.99–1.71) | 1.48 (1.09–2.01) | 0.014 |

| Age <63 years, Race = other | 1 | 1.37 (0.46–4.02) | 1.95 (0.71–5.32) | 1.32 (0.42–4.12) | 0.512 |

| Age ≥63 years, Race = white | 1 | 1.01 (0.91–1.12) | 0.94 (0.84–1.05) | 0.94 (0.83–1.07) | 0.267 |

| Age ≥63 years, Race = other | 1 | 1.00 (0.60–1.63) | 1.03 (0.63–1.70) | 0.70 (0.40–1.60) | 0.248 |

| Lower arm fracture | |||||

| Age <63 years, Race = white | 1 | 0.94 (0.85–1.04) | 0.93 (0.84–1.03) | 0.90 (0.80–1.01) | 0.087 |

| Age <63 years, Race = other | 1 | 0.97 (0.70–1.33) | 0.89 (0.65–1.21) | 0.84 (0.60–1.16) | 0.260 |

| Age ≥63 years, Race = white | 1 | 0.96 (0.89–1.04) | 0.93 (0.85–1.00) | 0.95 (0.89–1.04) | 0.254 |

| Age ≥63 years, Race = other | 1 | 1.00 (0.75–1.33) | 1.08 (0.81–1.44) | 0.93 (0.68–1.28) | 0.812 |

| Total fracture | |||||

| Age <63 years, Race = white | 1 | 0.95 (0.90–0.99) | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) | 0.95 (0.90–1.01) | 0.194 |

| Age <63 years, Race = other | 1 | 1.12 (0.96–1.30) | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) | 1.00 (0.85–1.16) | 0.897 |

| Age ≥63 years, Race = white | 1 | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 0.96 (0.93–1.00) | 0.95 (0.91–3.67) | 0.030 |

| Age ≥63 years, Race = other | 1 | 0.98 (0.85–1.13) | 1.06 (0.92–1.22) | 0.96 (0.82–1.12) | 0.906 |

Baseline Dietary Inflammatory Index Score: quartile 1, least inflammatory; quartile 4, most inflammatory. Models include: DII (baseline), CT, parental history of fracture, personal history of fracture at age 55 years or older, smoking, physical activity, region, diabetes, female hormone use, NSAID use, total calcium intake, randomization arm in CaD trial, corticosteroid use (screening), inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, weight, and height. (Note: Imputed values were used for covariates “parental history of fracture” and “personal history of fracture at age 55 years or older” because of a large number of missing values.) Number of women in each stratum: Age <63 years, Race = white: n = 59,723; Age <63 years, Race = other: n = 15,690; Age ≥63 years, Race = white: n = 71,919; Age ≥63 years, Race = other: n = 11,992.

To account for possible changing composition of dietary intake or changes in the food supply related to fortified foods over the follow-up period, we analyzed change in DII scores from baseline to year 3 in relation to fracture risk. The mean change in DII scores over the 3-year period was small, but statistically significant, and in the anti-inflammatory direction (mean change in DII score, –0.4 ± 2.4; p < 0.01). There were no significant associations with change in DII scores and fracture risk at any skeletal site. Data are available in Supporting Table 3.

To further investigate the association of DII scores to fracture risk in subgroups within WHI, we conducted several sensitivity analyses. Results were essentially unchanged when models excluded women in the dietary treatment arm of the DM trial or those who fractured after 2005, the end date of the original WHI studies. Similarly, we controlled for randomization arm to the CaD trial and found no significant changes in results (data not shown). However, when we excluded women who reported taking bone-active medications (female hormones, bisphosphonates, corticosteroids, or selective estrogen receptor modulators) at baseline or those in the active treatment arm of the HT clinical trial, magnitude of risk for hip fracture increased to 15% in women consuming the most inflammatory diet (Q4 multivariable HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.94 to 1.42), although this was not statistically significant (p for linear trend 0.35). In contrast, women in the highest quartile of DII scores had a 13% decreased risk of lower-arm fractures (Q4 HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77 to 0.99; p for linear trend 0.04), and an 8% lower total fracture risk (Q4 HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86 to 0.98; p for linear trend 0.01). Results are available in Supporting Table 4.

DII and BMD

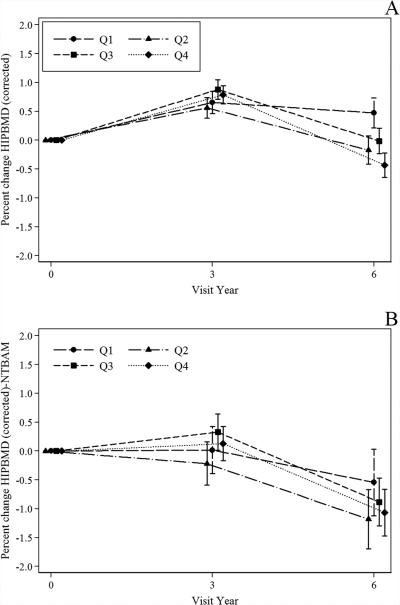

Percent change in total hip BMD was analyzed by pairwise comparisons of Q4 versus Q1 baseline DII scores over 6 years of follow-up. There were 8303 women who had baseline hip BMD and complete covariate data included in these analyses. After multivariable adjustment, women with the least inflammatory dietary pattern (Q1) had a more positive overall change in hip BMD (p for linear trend <0.001) (Fig. 1A). When BMD was evaluated by visit year, women in Q1 had lower mean hip BMD at baseline, but lost less BMD at the hip by year 6 than women with the most inflammatory dietary pattern. Similar results were seen in subgroup analysis of approximately 3275 women with BMD data who were not on bone-active medications (ie, corticosteroids, bisphosphonates, SERMS, female hormones, or randomization to HT treatment arm) at the baseline visit (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Percent change in hip BMD from baseline to year 6 in WHI participants. (A) Pairwise comparisons of % change in hip BMD by DII Q1 versus Q4 for baseline (n = 8303) through years 3 (n = 7681) and 6 (n = 6532). There was a significant difference in change in hip BMD at year 6 (Q1 < loss of BMD than Q4; p ≤ 0.0001); p for linear trend <0.001. Adjusted for, age, race, DII (baseline), CT, parental history of fracture, smoking, physical activity, geographic region, diabetes, NSAID use, total calcium intake change (from baseline to year 3), weight and height, IBD and RA, corticosteroid use (baseline), female hormone use. Linear mixed effect model was used to compare Q1 and Q4; adjusted for multiple comparisons. Tests for linear trend were performed using standard orthogonal contrasts. (B) Women in these analyses were not randomized to treatment in WHI hormone therapy trials and reported no current use of any of the following bone-active medications at baseline: estrogen, estrogen + progestin, bisphosphonates, corticosteroids, or selective estrogen receptor modulators. Pairwise comparisons of % change in hip BMD by DII Q1 versus Q4 for baseline (n = 3255) through years 3 (n = 2557) and 6 (n = 2320). There was a significant difference in change in hip BMD at year 6 (Q1 < loss of BMD than Q4; p = 0.013). p for linear trend <0.001. Linear mixed effect model was used to compare Q1 and Q4; adjusted for multiple comparisons. Model includes: age, race, DII (baseline), CT, parental history of fracture, smoking, physical activity, region, diabetes, NSAID use, total calcium intake, randomization arm in CaD trial, weight and height, IBD and RA. Tests for linear trend were performed using standard orthogonal contrasts. BMD = bone mineral density; CaD = calcium plus vitamin D supplement; CT = clinical trial assignment; DII = dietary inflammatory index; IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; NTBAM = not taken bone-active medication; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; Q = quartile; WHI = Women's Health Initiative.

Discussion

This large prospective study examined the association of an inflammatory dietary pattern, as measured by the DII, with risk of fracture and changes in BMD in postmenopausal women who were part of the WHI. This is the first investigation of the DII and fracture outcomes and changes in BMD. Women with the lowest DII scores (least inflammatory diet) lost significantly less BMD at the hip over 6 years of follow-up compared to women with the most inflammatory diet pattern. Additionally, in women who were younger than 63 years and white, a higher DII score was associated with increased risk of hip fracture.. Conversely, risk of total fracture and lower-arm fracture was modestly lower in women with the most inflammatory DII scores. After stratification analysis by age and race, this trend was observed only for total fractures in white women who were 63 years or older.

A higher-quality diet has been associated with lower inflammation(13,14,22) and lower fracture risk(34) in older adults. Diet quality, as measured by mean baseline DII scores in our sample of WHI women, was similar to other cohorts of older women and men in the United States(21,35) and varied widely, similar to a previous analysis of WHI participants.(26) In our analysis, DII score decreased slightly over the initial 3 years of WHI enrollment, indicating a small shift toward a less inflammatory diet during the study period. Nevertheless, we found no association with change in DII scores and fracture outcomes. Our results are somewhat similar to those reported from the WHI-DM trial, in which there was no difference in fracture risk between controls and women in the intervention group, who were deliberately changing their diet.(36) Changes in diet patterns that include foods known to reduce bone turnover,(18) as well as foods to lower inflammation, may be required to alter fracture risk in postmenopausal women.

DII and fracture outcomes

Compared to women in the lowest quartile (Q1) of DII scores, women in our sample with the most pro-inflammatory DII scores (Q4) had a 12% higher risk of hip fracture in minimally adjusted models. However, this association was no longer statistically significant after multivariable adjustment. Further stratification by age and race/ethnicity revealed an increased risk of hip fracture in white women younger than 63 years with the most inflammatory DII scores, and a similar, though nonsignificant direction of association, in younger women of other races/ethnicities. This suggests that a high-quality, less inflammatory diet may be especially important in reducing hip fracture risk in younger women. A healthy, nutrient-dense dietary pattern was associated with lower risk of fragility fractures in Chinese men and women,(34) but unlike our study, older Chinese women seemed to obtain particular benefit to bone from a healthy diet. This could be related to differences in instruments used to assess diet quality, as well as population characteristics. We hypothesized that a more inflammatory DII score would increase risk of fracture. We found evidence of this only in relation to hip fracture risk in younger women, particularly those who were white. There could be several reasons for these results. First, it could be that the benefits of a less inflammatory dietary pattern for bone health are overshadowed by the much greater risk for fracture produced by aging. Robbins and colleagues(37) have shown in previous work within WHI that age is by far the strongest predictor of hip fracture. Second, previous WHI results suggest that levels of inflammatory markers are a stronger predictor of hip fracture risk in white women compared to other races and ethnicities.(2) Third, our power to detect relationships between diet and fracture outcomes was greatest for white women because 82% of women in our sample were white. Finally, the dietary intake of minority women, particularly certain Hispanic populations, may not have been well captured by the WHI FFQ.(38)

Some nutrients known to be important to bone health, particularly calcium, are not included in the DII because of lack of evidence of a relation with inflammation.(20) Other diet quality indices that include dairy products has been associated with beneficial trends in risk of hip fractures in a Chinese cohort(34) and in the WHI,(39) suggesting that more than just inflammatory potential needs to be considered when examining diet and bone relationships. To account for this, we adjusted for calcium intake and assignment to the active group of the CaD trial in our statistical models, and examined associations stratified by calcium intake. Only in women consuming at least 1200 mg/day of calcium plus a less inflammatory diet, was there a trend toward lower hip fracture risk, further supporting the importance of an overall healthy dietary pattern for skeletal benefit in postmenopausal women.

In contrast to our hypothesis, we found a modestly lower risk of lower-arm and total fractures in women with the most inflammatory DII scores. After stratification by age and race/ethnicity, this trend was significant only in older white women. We have found this same, unexpected, inverse direction of association in other analyses of anti-inflammatory dietary components and risk for lower-arm or total fractures in WHI.(7,40) It is possible that this linear trend may be related to increased risk of falls accompanying a more active lifestyle in women eating a healthy diet. Indeed, we did find that women with the least inflammatory DII scores were more physically active and were at slightly greater risk of falls. In other large studies that have included women, more physical activity in the perimenopausal and postmenopausal period has been associated with greater risk of wrist fractures resulting from falls.(41,42) Furthermore, when we stratified our sample by calcium intake, only in women consuming at least 1200 mg/day of calcium plus a less inflammatory diet was lower-arm fracture risk significantly increased. That risk increased in women with the healthiest dietary pattern and highest calcium intake supports our speculation that lower-arm fractures are influenced by non-dietary factors, such as falls accompanying physical activity.

DII and BMD

In our analysis, women with the least inflammatory dietary pattern (Q1 of DII) had lower mean hip BMD at baseline. Baseline BMD represents an accumulation of years of changes in bone, but the baseline FFQ from which the DII was calculated reflects a measure of usual intake over the previous 3 months, which may not accurately represent previous long-term dietary exposure. Additionally, more women in the lowest quartile of the DII were older, white, and had lower BMI, which may have increased risk for lower BMD. However, despite these risk factors, a less inflammatory dietary pattern appeared to offer some protection from loss of BMD at the hip over 6 years of follow-up. It is possible that our results were influenced by regression toward the mean, but this seems unlikely because our sample size was large and BMD values were normally distributed. Our results are similar to the only other analysis of the DII and BMD to date, a cross-sectional study of 160 postmenopausal Iranian women, from which researchers reported that a less inflammatory DII score was associated with significantly higher BMD of the lumbar spine, and a nonsignificantly higher BMD of the femoral neck.(27)

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the prospective design, the large and well-established cohort of geographically and racially/ethnically diverse women, central adjudication of hip fracture, availability of serial measures of BMD in a subset of the sample, and testing of outcomes in relation to longitudinal change in DII score. This study also had several limitations. This was an observational study of postmenopausal women; generalizability of the results is limited to this high-risk group. The OS and CT cohorts had different follow-up schedules (CT every 6 months, OS annually); therefore, precision of follow-up data may differ for outcomes. Lower-arm fractures and a portion of total fractures were self-reported, which could result in misclassification error, although, as previously discussed, agreement between self-report and adjudicated fracture outcomes was high. Although the DII was designed to assess the overall inflammatory potential of the diet, it is possible that an individual food component or small number of components may primarily drive the association with fracture risk. Data from FFQs were used to derive DII scores; self-reported dietary data have known measurement error. For women who were part of the DM trial, which excluded women with fat intake of <32% of kcal at baseline, the measure of % energy from fat (a component of the DII) calculated from the baseline FFQ, was upwardly biased due to regression to the mean; lowering fat intake was a goal of the intervention group,(43) and women eligible for entry into the DM had reported energy intake values that were 160 kcal/day lower than expected energy intake values when compared to ineligible women (ie, those reporting >32% calories as fat).(44) Thus, we conducted sensitivity analyses excluding women in the treatment arm of the DM trial. Also, the DII did not include calcium, a key nutrient in bone health, therefore we adjusted for calcium in statistical models. Finally, no data were available for some specific dietary supplements that may affect inflammation (eg, fish oil).

Conclusions

Postmenopausal women with a less inflammatory DII score had lower hip BMD at baseline, but lost less BMD at the hip over 6 years compared to women consuming a more inflammatory diet. Consuming a more inflammatory diet was associated with increased risk of hip fracture in younger white women. Further research is warranted to confirm these findings among more diverse populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The WHI program is funded by the NIH, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) through contracts HHSN268201100046C, HHSN268201100001C, HHSN268201100002C, HHSN268201100003C, and HHSN268201100004C. Kellie Weinhold, Fred Tabung, Nitin Shivappa, and Short List of WHI Investigators: WHI Program Office (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA): Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller. Clinical Coordinating Center (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA): Garnet Anderson, Ross Prentice, Andrea LaCroix, and Charles Kooperberg. Investigators and Academic Centers: (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA) JoAnn E. Manson; (MedStar Health Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC, USA) Barbara V. Howard; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA, USA) Marcia L. Stefanick; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA) Rebecca Jackson; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ, USA) Cynthia A. Thomson; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA) Jean Wactawski-Wende; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL, USA) Marian Limacher; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA, USA) Jennifer Robinson; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) Lewis Kuller; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) Sally Shumaker; (University of Nevada, Reno, NV, USA) Robert Brunner; (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA) Karen L. Margolis. Women's Health Initiative Memory Study: (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) Mark Espeland.

Authors’ roles: TSO, SES, JRH, and RDJ designed research; VY analyzed data; TSO, VY, SES, YM, JRH, ML, YMR, KJ, WL, MS, JC, JWW, and RDJ wrote the manuscript; TSO and RDJ had primary responsibility for final content.

Footnotes

Public clinical trial registration: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00000611. Women's Health Initiative (WHI).

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Disclosures

JRH owns controlling interest in Connecting Health Innovations LLC (CHI), a company planning to license the right to his invention of the dietary inflammatory index from the University of South Carolina in order to develop computer and smart phone applications for patient counseling and dietary intervention in clinical settings. The remaining authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cauley JA, Danielson ME, Boudreau RM, et al. Inflammatory markers and incident fracture risk in older men and women: the Health Aging and Body Composition Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(7):1088–95. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbour KE, Boudreau R, Danielson ME, et al. Inflammatory markers and the risk of hip fracture: the Women's Health Initiative. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(5):1167–76. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding C, Parameswaran V, Udayan R, Burgess J, Jones G. Circulating levels of inflammatory markers predict change in bone mineral density and resorption in older adults: a longitudinal study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1952–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao G, Etherton TD, Martin KR, West SG, Gillies PJ, Kris-Etherton PM. Dietary {alpha}-linolenic acid reduces inflammatory and lipid cardiovascular risk factors in hypercholesterolemic men and women. J Nutr. 2004;134(11):2991–7. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.11.2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esmaillzadeh A, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Azadbakht L, Hu FB, Willett WC. Dietary patterns and markers of systemic inflammation among Iranian women. J Nutr. 2007;137(4):992–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma Y, Hebert JR, Li W, et al. Association between dietary fiber and markers of systemic inflammation in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Nutrition. 2008;24(10):941–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orchard TS, Larson JC, Alghothani N, et al. Magnesium intake, bone mineral density, and fractures: results from the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(4):926–33. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.067488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ing SW, Orchard TS, Lu B, et al. TNF receptors predict hip fracture risk in the WHI study and fatty acid intake does not modify this association. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(9):3380–7. doi: 10.1210/JC.2015-1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabung FK, Steck SE, Liese AD, et al. Association between dietary inflammatory potential and breast cancer incidence and death: results from the Women's Health Initiative. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(11):1277–85. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicklas TA, Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Berenson G. Eating patterns, dietary quality and obesity. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(6):599–608. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2001.10719064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu FB. Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13(1):3–9. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200202000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heroux M, Janssen I, Lam M, et al. Dietary patterns and the risk of mortality: impact of cardiorespiratory fitness. Int J Epidemiol. 2010 Feb;39(1):197–209. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fung TT, McCullough ML, Newby PK, et al. Diet-quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1):163–73. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavicchia PP, Steck SE, Hurley TG, et al. A new dietary inflammatory index predicts interval changes in serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. J Nutr. 2009;139(12):2365–72. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.114025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boynton A, Neuhouser ML, Wener MH, et al. Associations between healthy eating patterns and immune function or inflammation in overweight or obese postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(5):1445–55. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardcastle AC, Aucott L, Fraser WD, Reid DM, Macdonald HM. Dietary patterns, bone resorption and bone mineral density in early post-menopausal Scottish women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(3):378–85. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedone C, Napoli N, Pozzilli P, et al. Dietary pattern and bone density changes in elderly women: a longitudinal study. J Am Coll Nutr. 2011;30(2):149–54. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2011.10719954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunn CA, Weber JL, McGill AT, Kruger MC. Increased intake of selected vegetables, herbs and fruit may reduce bone turnover in post-menopausal women. Nutrients. 2015;7(4):2499–517. doi: 10.3390/nu7042499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langsetmo L, Hanley DA, Prior JC, et al. Dietary patterns and incident low-trauma fractures in postmenopausal women and men aged ≥ 50 y: a population-based cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(1):192–9. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.002956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, Hussey JR, Hebert JR. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(8):1689–96. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013002115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, et al. A population-based dietary inflammatory index predicts levels of C-reactive protein in the Seasonal Variation of Blood Cholesterol Study (SEASONS). Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(8):1825–33. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013002565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabung FK, Steck SE, Zhang J, et al. Construct validation of the dietary inflammatory index among postmenopausal women. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(6):398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wirth MD, Burch J, Shivappa N, et al. Association of a Dietary Inflammatory Index with inflammatory indices and metabolic syndrome among police officers. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(9):986–9. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood LG, Shivappa N, Berthon BS, Gibson PG, Hebert JR. Dietary inflammatory index is related to asthma risk, lung function and systemic inflammation in asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(1):177–83. doi: 10.1111/cea.12323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wirth MD, Burch J, Shivappa N, et al. Dietary inflammatory index scores differ by shift work status: NHANES 2005 to 2010. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(2):145–8. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabung FK, Steck SE, Ma Y, et al. The association between dietary inflammatory index and risk of colorectal cancer among postmenopausal women: results from the Women's Health Initiative. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(3):399–408. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0515-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shivappa N, Hébert J, Karamati M, Shariati-Bafghi S-E, Rashidkhani B. Increased inflammatory potential of diet is associated with bone mineral density among postmenopausal women in Iran. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55(2):561–8. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-0875-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Women's Health Initiative Study Group Design of the Women's Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. The Women's Health Initiative Study Group. Controlled Clin Trials. 1998;19(1):61–109. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Tinker LF, Carter RA, Bolton MP, Agurs-Collins T. Measurement characteristics of the Women's Health Initiative food frequency questionnaire. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9(3):178–87. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curb JD, McTiernan A, Heckbert SR, et al. Outcomes ascertainment and adjudication methods in the Women's Health Initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9 Suppl):S122–8. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Z, Kooperberg C, Pettinger MB, et al. Validity of self-report for fractures among a multiethnic cohort of postmenopausal women: results from the Women's Health Initiative observational study and clinical trials. Menopause. 2004;11(3):264–74. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000094210.15096.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Cauley JA, McGowan J. The Women's Health Initiative calcium-vitamin D trial: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9 Suppl):S98–106. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(7):669–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeng FF, Xue WQ, Cao WT, et al. Diet-quality scores and risk of hip fractures in elderly urban Chinese in Guangdong, China: a case-control study. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(8):2131–41. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2741-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wirth MD, Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, Hebert JR. The dietary inflammatory index is associated with colorectal cancer in the National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons Diet and Health Study. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(11):1819–27. doi: 10.1017/S000711451500104X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McTiernan A, Wactawski-Wende J, Wu L, et al. Low-fat, increased fruit, vegetable, and grain dietary pattern, fractures, and bone mineral density: the Women's Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(6):1864–76. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robbins J, Aragaki AK, Kooperberg C, et al. Factors associated with 5-year risk of hip fracture in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2007;298(20):2389–98. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Tinker LF, Neuhouser ML, et al. Women's Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial: update and application of biomarker calibration to self-report measures of diet and physical activity. In: Balakrishnan N, editor. Methods and applications of statistics in clinical trials: concepts, principles, trials, and designs. Vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ: 2014. pp. 931–44. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haring B, Crandall CJ, Wu C, et al. Dietary patterns and fractures in postmenopausal women: results from the Women's Health Initiative. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):645–52. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orchard TS, Cauley JA, Frank GC, et al. Fatty acid consumption and risk of fracture in the Women's Health Initiative. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(6):1452–60. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelsey JL, Browner WS, Seeley DG, Nevitt MC, Cummings SR. Risk factors for fractures of the distal forearm and proximal humerus. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(5):477–89. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rikkonen T, Salovaara K, Sirola J, et al. Physical activity slows femoral bone loss but promotes wrist fractures in postmenopausal women: a 15 -year follow-up of OSTPRE study. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(11):2332–40. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ritenbaugh C, Patterson RE, Chlebowski RT, et al. The Women's Health Initiative Dietary Modification trial: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9 Suppl):S87–97. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hebert JR, Patterson RE, Gorfine M, Ebbeling CB, St Jeor ST, Chlebowski RT. Differences between estimated caloric requirements and self-reported caloric intake in the Women's Health Initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9):629–37. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.