Abstract

Pituitary FSH regulates ovarian and testicular function. Activins stimulate FSHβ subunit (Fshb) gene transcription in gonadotrope cells, the rate-limiting step in mature FSH synthesis. Activin A-induced murine Fshb gene transcription in immortalized gonadotropes is dependent on homolog of Drosophila mothers against decapentaplegic (SMAD) proteins as well as the forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 (FOXL2). Here, we demonstrate that FOXL2 synergizes with SMAD2, SMAD3, and SMAD4 to stimulate murine Fshb promoter-reporter activity in heterologous cells. Moreover, SMAD3-induction of Fshb promoter activity or endogenous mRNA expression is dependent upon endogenous FOXL2 in homologous cells. FOXL2/SMAD synergy requires binding of both FOXL2 and SMAD3 or SMAD4 to DNA. Of three putative forkhead-binding elements identified in the murine Fshb promoter, only the most proximal is absolutely required for activin A induction of reporter activity in homologous cells. Additionally, mutations to the minimal SMAD-binding element adjacent to the proximal forkhead-binding element abrogate activin A or FOXL2/SMAD3 induction of reporter activity. In contrast, a mutation that impairs an adjacent PBX1/PREP1 (pre-B cell leukemia transcription factor 1–PBX/knotted-1 homeobox-1) binding site does not alter activin A-stimulated promoter activity in homologous cells. Collectively, these and previous data suggest a model in which activins stimulate formation of FOXL2-SMAD2/3/4 complexes, which bind to the proximal murine Fshb promoter to stimulate its transcription. Within these complexes, FOXL2 and SMAD3 or SMAD4 bind to adjacent cis-elements, with SMAD3 brokering the physical interaction with FOXL2. Because this composite response element is highly conserved, this suggests a general mechanism whereby activins may regulate and/or modulate Fshb transcription in mammals.

FSH, a product of gonadotrope cells of the anterior pituitary gland, regulates granulosa and Sertoli cell functions in the ovary and testes, respectively. Perturbations in FSH synthesis, secretion, and/or action lead to impaired reproductive function and, in some cases, infertility (1–7). FSH is a dimeric glycoprotein comprised of α- and β-subunits. The latter, known as FSHβ (or FSHB), determines biologic specificity and is rate limiting in production of the mature hormone. FSH synthesis and secretion are regulated by peptide, protein, and steroid hormones from the brain, pituitary, and gonads. Arguably, intrapituitary activins are the most potent stimulators of FSH production, at least in rodents (8).

Activins are members of the TGFβ superfamily and signal in gonadotrope cells to increase Fshb subunit transcription (9). Canonical activin signaling involves binding of the ligand to complexes of type I and type II serine-threonine receptor kinases. The type I receptors then phosphorylate intracellular effector molecules, homolog of Drosophila mothers against decapentaplegic (SMAD)2 and SMAD3, which partner with SMAD4, accumulate in the nucleus, and regulate target gene transcription (10). Previously, we and others showed that activins signal via SMAD2, SMAD3, and SMAD4 to stimulate Fshb promoter-reporter activity in the immortalized murine gonadotrope cell line LβT2 (11–13). The rat and murine promoters possess a proximal 8-basepair (bp) palindromic SMAD-binding element (SBE) that is required for maximal induction by activins or overexpressed SMADs (at −266/−259 in mouse, with +1 representing the start of transcription) (14–17). Activin responsive Fshb promoters from other species, including pig and sheep, however, lack this SBE, indicating that it is not absolutely required for the activin response (18–22). Indeed, even in the rodent promoters, mutations to the 8-bp SBE inhibit the response to long-term activin treatment (i.e. 24 h) by no more than 50% (14–17).

The search for additional activin response elements in the Fshb promoter initially focused on minimal (i.e. 4 bp) SBEs, comprised of the sequence GTCT or its reverse complement AGAC. In the murine promoter, mutations in two such sequences, the so-called −153 and −120 sites, significantly impaired both activin A- and SMAD3-stimulated activity in LβT2 cells (16, 23). Mutation of the −120 site (GTCT→GTAG) was particularly disruptive. Although both sites appear to mediate activin- and SMAD3-induced promoter activity, to be bona fide SBEs, they must actually bind SMAD proteins. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) using probes containing either the −153 or −120 site demonstrated phosphorylated SMAD2/3 binding to the latter, but not the former with nuclear extracts from LβT2 cells (16). However, we showed weak binding to a probe containing the −153 site using recombinant SMAD3 or SMAD4 mothers against decapentaplegic homology 1 (MH1) domains (see supplemental figure 2A in Ref. 20). Weak SMAD binding may be explained by the low affinity of the proteins for minimal SBEs and their requirement for higher affinity DNA-binding cofactors to stabilize their interactions with DNA (24, 25).

Recently, the forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 (FOXL2) emerged as an important SMAD3 DNA-binding cofactor mediating activin-induction of Fshb transcription in immortalized gonadotropes. We demonstrated that FOXL2 binds to a cis-element [hereafter forkhead-binding element (FBE)] in close proximity to a minimal SBE at −160/−157 in the porcine Fshb promoter (analogous to the −153 site in mouse) (20). Further, mutation of this FBE or knockdown of FOXL2 with short interfering RNA (siRNA) abrogated activin A-induced reporter activity. More recently, we showed that SMAD3 binds to the adjacent SBE in a FOXL2-dependent manner and that binding of both proteins via their respective sites is required for their synergistic activation of porcine Fshb promoter activity (21). FOXL2 binds only weakly to the corresponding promoter region in mouse (26), likely because of 2-bp differences in the FBE between mouse and pig. Indeed, we showed that substituting the porcine basepairs into the murine promoter dramatically increased both FOXL2 binding and activin A-stimulated reporter activity in homologous cells (20). Nonetheless, knockdown of FOXL2 in LβT2 cells attenuates activin A-stimulated murine Fshb promoter-reporter activity as well as induction of endogenous Fshb mRNA levels by overexpressed activin receptor-like kinase (ALK)4-T206D (ALK4TD), a constitutively active form of the activin type I receptor (20). These data suggested that FOXL2 might act elsewhere in the murine promoter. We identified a more proximal FBE that is conserved in both the murine and porcine promoters. Mutations in this site, which blocked FOXL2 binding, greatly attenuated activin A-induced porcine and murine Fshb promoter-reporter activities. Importantly, this FBE is situated just 3′ of the −120 SBE (−131/−128 in pig), and in the case of the porcine promoter, FOXL2 and SMAD3 cooperatively activate transcription through this composite element (21).

Whether FOXL2 and SMAD function via the corresponding elements in the murine promoter to synergistically regulate transcription is not yet known. Although this seems the most likely possibility, other observations challenge this idea. First, a cis-element for the homeodomain transcription factors pre-B cell leukemia transcription factor 1 (PBX1) and PBX/knotted-1 homeobox-1 (PREP1) was localized just 5′ of the −120 site, and PBX1/PREP1 were argued to potentiate SMAD binding to the adjacent minimal SBE (23). Second, additional forkhead (FOXL2) binding sites were recently reported in the murine Fshb promoter; and one located about 350 bp 5′ of the transcription start site was suggested to mediate FOXL2 actions independently of SMADs (26). Here, we endeavored to: 1) define a mechanism for FOXL2/SMAD synergistic activation of murine Fshb transcription, 2) clarify the roles of the different FOXL2 binding sites in the murine Fshb promoter, and 3) determine the relative importance of FOXL2 vs. PBX1/PREP1 binding to the proximal promoter in mediating the activin response.

Results

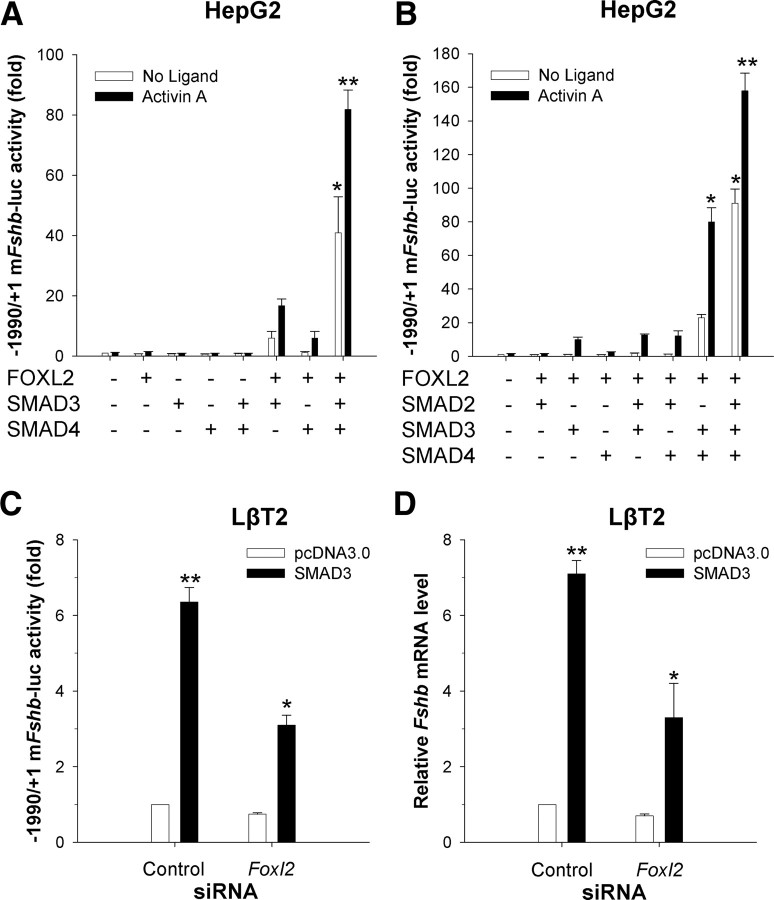

FOXL2 and SMADs synergistically regulate murine Fshb transcription

We previously established roles for endogenous FOXL2 and SMAD proteins in activin A induction of murine and porcine Fshb transcription in homologous gonadotrope cells (LβT2) (11, 13, 15, 20, 21). We further established that FOXL2 confers activin responsiveness to the porcine Fshb promoter in heterologous cells (e.g. HepG2 or CHO; note that these cells were selected based on their activin responsiveness and lack of endogenous FOXL2 expression). This effect was potentiated by SMAD3 overexpression, which had no effect on its own (20, 21), suggesting that although necessary for Fshb transcription, SMAD3 alone is not sufficient. Here, we again employed the heterologous HepG2 model to establish necessity and sufficiency for FOXL2 and SMAD proteins in murine Fshb transcriptional regulation. In contrast to our observations with the porcine promoter, overexpression of FOXL2 alone in HepG2 cells had no effect on the murine Fshb promoter (−1990/+1) in the presence or absence of activin A. This interspecies difference might stem from the presence of a unique high affinity FOXL2 binding site (FBE2) in pig (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org). Likewise, expression of SMAD2, SMAD3, or SMAD4 alone or in combination with one another had no effect in the absence of FOXL2 (Fig. 1A) (21). However, coexpression of FOXL2 and SMAD3 conferred both ligand-independent and ligand-dependent activation of murine Fshb reporter activity (Fig. 1A). This effect was significantly enhanced in the presence of overexpressed SMAD4.

Fig. 1.

FOXL2 and SMADs synergistically regulate the murine Fshb promoter activity. A, HepG2 cells were transfected with the −1990/+1 murine Fshb-luc reporter and different combinations of FOXL2, SMAD3, and SMAD4. Cells were then treated overnight with activin A. Relative reporter activity from three independent experiments (mean + sem, n = 3) is shown. Data were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey of the significant interaction. B, HepG2 cells were transfected as in A, except SMAD2 was an added variable. Data are from three independent experiments (n = 3) and were analyzed as in A. C, LβT2 cells were transfected with the −1990/+1 murine Fshb-luc reporter along with control or Foxl2 siRNA (5 nm final) plus pcDNA3 or SMAD3 expression vector. The data represent means of three independent experiments (n = 3) and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc of the significant interaction. D, LβT2 cells in six-well plates were transfected with control or Foxl2 siRNA along with pcDNA3 or SMAD3 expression vector. Relative endogenous Fshb mRNA expression was assessed by qRT-PCR. The data are the mean (+sd) of replicate samples and were log transformed before analysis (one-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc). The experiment was performed two additional times with similar results (data not shown). Here, and in subsequent figures, bars with asterisks differ significantly from those without asterisks, and bars with different numbers of asterisks differ from one another.

We reported previously that activin A regulates murine Fshb promoter activity via SMAD2, in addition to SMAD3 and SMAD4 in homologous cells (11, 15), although this has been disputed by others (14, 17). Here, using the heterologous HepG2 cell system, we further established a role for SMAD2 in murine Fshb transcription. Although ineffective on its own or with FOXL2, SMAD2 potentiated SMAD3/4-FOXL2 activation of the murine Fshb promoter in HepG2 cells (Fig. 1B). This result is analogous to what we reported previously in homologous LβT2 cells (which express FOXL2 endogenously), where the combination of SMAD2/3/4 more potently stimulated promoter activity than did the combination of SMAD3/4. Collectively, these data indicate that the cooperative actions of FOXL2 and SMADs are sufficient to stimulate murine Fshb transcription in heterologous cells.

Importantly, these cooperative actions were also observed in homologous cells. Overexpressed SMAD3 stimulates murine Fshb promoter activity in LβT2 cells (11, 15, 16, 26). Here, this response was attenuated after knock down of endogenous FOXL2 expression by RNA interference (Fig. 1C). We previously reported impaired activin A-stimulated murine Fshb promoter activity in cells cotransfected with the same Foxl2 siRNA (see supplemental figure 6A in Ref. 20). The Foxl2 siRNA also attenuated SMAD3-stimulated, but not basal, endogenous Fshb mRNA expression in LβT2 cells (Fig. 1D). The Foxl2 siRNA used in these experiments was validated previously (20), and we confirmed here that it did not inhibit SMAD3 overexpression (data not shown). The poor transfection efficiency of LβT2 cells (∼5–10%) precludes an accurate assessment of the extent of knockdown in transfected cells. Therefore, it is unclear at present whether the residual SMAD3 response reflects incomplete suppression of FOXL2 expression or FOXL2-independent actions of SMAD3. Collectively, these data indicate that SMAD3 induction of the murine Fshb gene in homologous cells was at least partly dependent upon endogenous FOXL2.

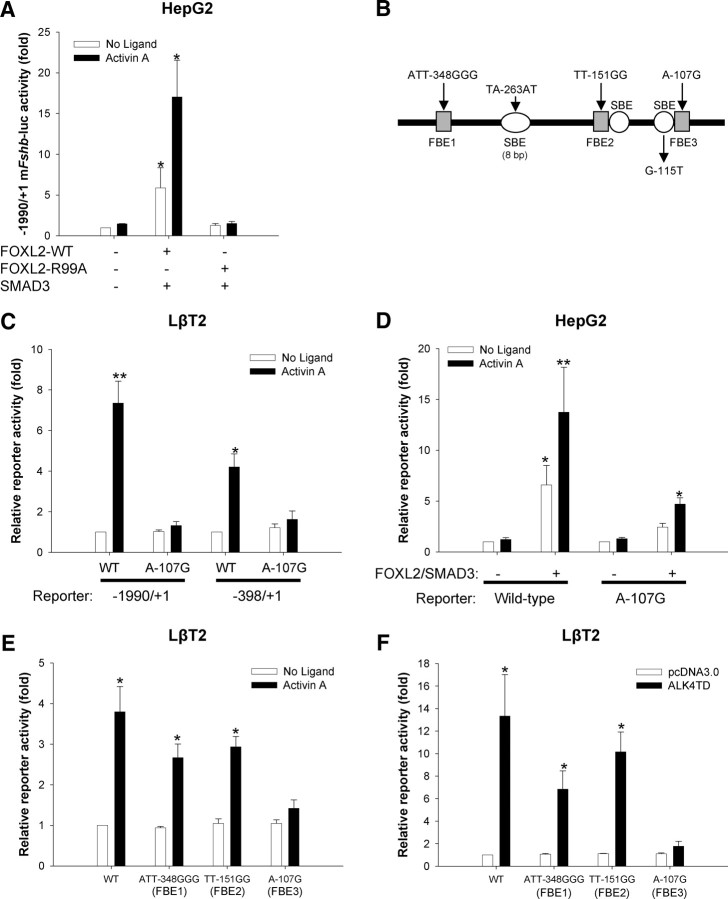

FOXL2 regulates murine Fshb transcription via a proximal FBE

We next examined whether FOXL2 must bind DNA to mediate its effects on murine Fshb transcription. We transfected HepG2 cells with a murine Fshb reporter, SMAD3, and either wild-type (WT) or DNA-binding-deficient (R99A, see Ref. 21) forms of FOXL2. Again, SMAD3 and FOXL2-WT synergistically regulated promoter activity in the presence or absence of activin A (Fig. 2A). In contrast, SMAD3 and FOXL2-R99A had no effect with or without activin A. Similarly, in homologous LβT2 cells, the Foxl2 siRNA impaired activin A-induced murine Fshb promoter activity, and this response was rescued by cotransfection of an siRNA-resistant form of FOXL2-WT but not FOXL2-R99A (Supplemental Fig. 2). These data suggest that FOXL2 must bind DNA directly to mediate its effects on the murine Fshb promoter.

Fig. 2.

Activin A and FOXL2 regulate murine Fshb promoter activity via a proximal FBE. A, HepG2 cells were transfected and treated as in Fig. 1A, except here, SMAD3 was used in combination with WT or DNA-binding-deficient (R99A) forms of FOXL2. The data represent means of three experiments (+sem, n = 3) and were log transformed before analysis. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc comparisons. B, Schematic representation of the proximal murine Fshb promoter. Gray boxes reflect the approximate positions of three forkhead or FOXL2 binding elements (FBE). White circles or ovals represent the approximate positions of 4- or 8-bp SBEs. The relative positions of mutations introduced into reporter constructs and/or EMSA probes are shown. C, LβT2 cells were transfected with WT or A-107G mutant −1990/+1 or −398/+1 murine Fshb-luc reporters. Cells were then treated with activin A for 24 h. The data represent mean (+sem) relative reporter activity of three independent experiments (n = 3). Data for the different length reporters were analyzed in separate two-way ANOVAs followed by Tukey post hoc analysis of the significant interactions. D, HepG2 cells were transfected and treated as in A with either WT or A-107G mutant forms of the −1990/+1 murine Fshb-luc reporter plus/minus SMAD3 and FOXL2. The data represent the means of four independent experiments (n = 4, +sem). Log transformed data were subjected to three-way ANOVA (reporter x SMAD3/FOXL2 x activin A) followed by a Tukey post hoc test for pairwise comparisons. E, LβT2 cells were transfected and treated as in C with the indicated WT or mutant −398/+1 murine Fshb-luc reporter constructs. Relative promoter activity from four independent experiments (n = 4, mean + sem) is shown. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (reporter x ligand) followed by Tukey post hoc of the significant interaction. F, LβT2 cells were transfected and treated as in E, except ALK4TD was used in place of activin A. The data reflect the mean (+sem) of three independent experiments (n = 3) and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc comparison.

At least three distinct FBE have been identified or described in the proximal murine Fshb promoter, two corresponding to sites that we previously characterized in the porcine promoter and a third more distal site at about −350 bp relative to the transcription start site (20, 21, 26). These are presented as FBE1, FBE2, and FBE3 (in the 5′ to 3′ direction) in Fig. 2B. We previously reported that FOXL2 binds FBE3 and that the point mutation A-107G both blocks this binding and abrogates activin A-stimulated activity of a −355/+1 murine Fshb promoter-reporter in LβT2 cells (20). Here, when introduced into longer reporters [−398/+1 (to ensure inclusion of the entirety of FBE1) and −1990/+1], the same mutation again inhibited activin A-stimulated transcription in LβT2 cells (Fig. 2C). The A-107G mutation also inhibited activin A/FOXL2/SMAD3-stimulated promoter activity in HepG2 cells (Fig. 2D).

We next explored potential roles for FBE1 and FBE2. After confirming FOXL2 binding to FBE1 (data not shown), we introduced a mutation in FBE1 reported to impair FOXL2 binding and activin A responsiveness (ATT-348GGG) (26). In our hands, this mutation caused a small impairment in the activin A response of the −398/+1 murine Fshb promoter-reporter, but the effect was not statistically significant (Fig. 2E). When introduced into the full-length −1990/+1 reporter, the ATT-348GGG mutation caused a more obvious impairment in the activin A response, but this again failed to reach statistical significance (Supplemental Fig. 3A). The FBE3, but not FBE1, site mutation also significantly impaired reporter activity induced by the constitutively active activin type I receptor, ALK4TD (Fig. 2F).

The FBE2 site corresponds to the high affinity FOXL2 binding element first identified in the porcine promoter. We previously reported, using LβT2 nuclear extracts, that FOXL2 did not bind to this part of the murine promoter in EMSA (see supplemental figure 7 in Ref. 20). More recently, FOXL2 binding to this part of the murine promoter was observed when using extracts from COS-1 cells overexpressing the protein (26). Having defined the basepairs mediating FOXL2 binding to FBE2 in the porcine gene (20), we introduced a mutation (TT-151GG) into the −398/+1 murine promoter that would be predicted to disrupt FOXL2 binding to this site should any binding actually occur. As with the ATT-348GGG mutation in FBE1, this caused a small, but nonsignificant reduction in activin A-induced reporter activity (Fig. 2E). Similar results were observed when ALK4TD was used in place of activin A (Fig. 2F). Corpuz et al. (26) introduced an alternative mutation (TTT-141GGG) in a site presumed, although not actually shown, to mediate FOXL2 binding in the vicinity (3′) of FBE2. We therefore examined the effects of the same mutation in the context of the −398/+1 murine Fshb reporter and observed no significant impairments in activin A- or ALK4TD-stimulated activity (Supplemental Fig. 3, B and C).

Collectively, the data suggest that FOXL2 must bind DNA directly to mediate activin-induced murine Fshb transcription and does so predominantly via FBE3.

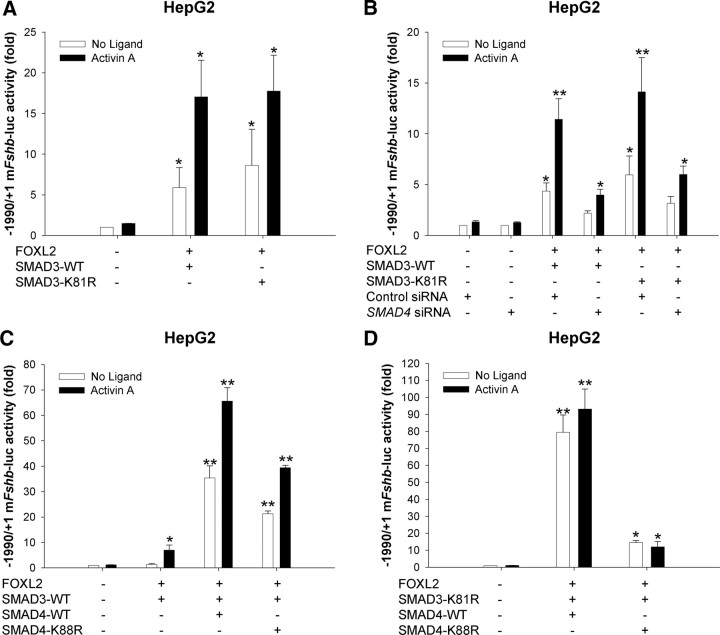

SMAD3 or SMAD4 must bind DNA to functionally synergize with FOXL2

We previously showed that SMAD3 and SMAD4 DNA-binding activity is critical for their induction of murine Fshb promoter activity in LβT2 cells (13, 15). We next examined the role of SMAD DNA binding in FOXL2/SMAD synergism. We cotransfected HepG2 cells with the −1990/+1 murine Fshb promoter-reporter, FOXL2-WT, and either SMAD3-WT or SMAD3-K81R. The latter is DNA-binding deficient (15, 21). SMAD3-K81R was as effective as SMAD3-WT in stimulating −1990/+1 and −398/+1 reporter activity with FOXL2 in the presence or absence of activin A (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. 4A), suggesting that SMAD3 need not bind DNA to synergize with FOXL2 in heterologous HepG2 cells. We next asked whether endogenous SMAD4, which both binds DNA and interacts with SMAD3, might play a necessary role in the SMAD3/FOXL2 synergism. We transfected HepG2 cells with the 2-kb Fshb reporter, FOXL2-WT, SMAD3-WT or SMAD3-K81R, and either control or SMAD4 siRNA. We previously validated this siRNA for use in both LβT2 and HepG2 cells (13, 21). Knockdown of SMAD4 significantly impaired the stimulatory effects of FOXL2 with either form of SMAD3 (Fig. 3B), confirming a role for endogenous SMAD4.

Fig. 3.

SMAD must bind DNA to synergistically regulate murine Fshb expression with FOXL2. A, HepG2 cells were transfected with the −1990/+1 murine Fshb-luc reporter and the indicated combinations of FOXL2 and WT or DNA-binding-deficient SMAD3 (K81R). Cells were then treated with activin A for 24 h. Relative reporter activity from three independent experiments (mean ± sem, n = 3) was analyzed by two-way ANOVA (of log- transformed data). Note that the data from the control and FOXL2 plus SMAD3-WT conditions are the same as from Fig. 2A, because the experiments were run in parallel. B, HepG2 cells were transfected as in A, with the exception that control or SMAD4 siRNA were also included as indicated. The data from three independent experiments (n = 3) were averaged (±sem) and log transformed before three-way ANOVA (siRNA x SMAD3 x activin A). C, HepG2 cells were transfected as in A with FOXL2, SMAD3, and either WT or DNA-binding-deficient (K88R) SMAD4. The results reflect the means (±sem) of three independent experiments (n = 3). Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (activin A x SMAD4). D, HepG2 cells were transfected as in C, except SMAD3–K81R was used in place of SMAD3-WT. Data are from three experiments (n = 3) and were analyzed by ANOVA (Tukey post hoc).

To determine the necessity for SMAD4 binding to DNA, we compared the effects of WT and DNA-binding-deficient SMAD4 (K88R) (27). When cotransfected with FOXL2 and SMAD3-WT, SMAD4-K88R could still synergistically enhance −1990/+1 and −398/+1 reporter activity in the presence or absence of activin A. Although the effects appeared to be impaired relative to those seen with SMAD4-WT, the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 3C and Supplemental Fig. 4B) and might have derived from slightly lower SMAD4-K88R expression in HepG2 cells (Supplemental Fig. 5). These data suggested that SMAD3 binding to DNA may be sufficient when SMAD4 cannot bind. Indeed, when cotransfected with the DNA-binding-deficient SMAD3-K81R, SMAD4-K88R could no longer synergistically regulate murine −1990/+1 or −398/+1 Fshb promoter activity in HepG2 cells in the presence or absence of activin A (Fig. 3D and Supplemental Fig. 4C). These data are consistent with our previous observations in LβT2 cells, where DNA-binding-deficient SMAD3 failed to stimulate murine Fshb transcription unless coexpressed with SMAD4-WT but not SMAD4-K88R (15). Overall, these data suggest that either SMAD3 or SMAD4 must bind DNA to stimulate murine Fshb promoter activity in synergy with FOXL2. The data further show that SMAD4's role in regulation of the Fshb promoter is not limited to its DNA-binding activity.

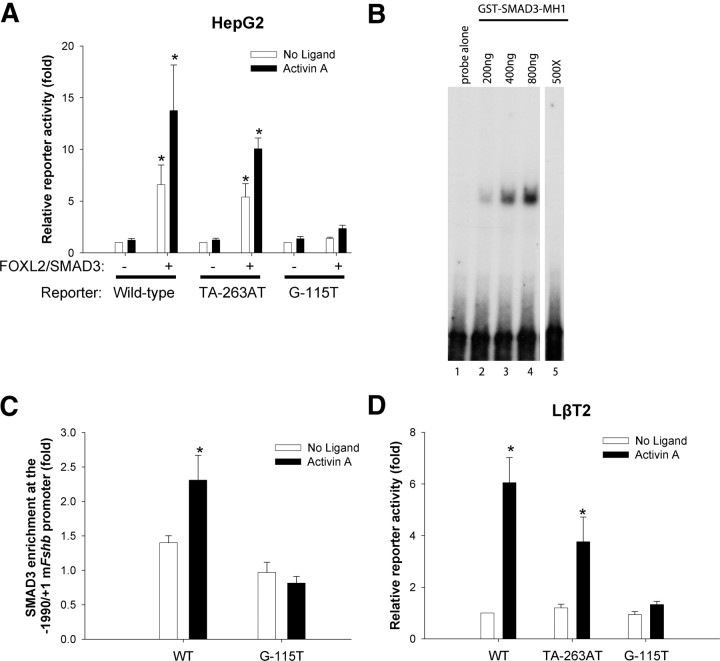

SMADs regulate murine Fshb via a cis-element adjacent to FBE3

SMAD2, SMAD3, and SMAD4 regulate murine Fshb transcription in homologous cells, in part, via an 8-bp SBE at −266/−259 (see Fig. 2B) (15). To determine whether the functional synergism between SMADs and FOXL2 in heterologous cells was similarly dependent on the 8-bp SBE, we compared the effects of SMAD3/FOXL2 coexpression on WT and TA-263AT mutant Fshb reporters in HepG2 cells. The latter mutation blocks SMAD binding to the 8-bp SBE (15) and, here, attenuated SMAD3/FOXL2 effects, particularly in the presence of activin A; but, this was not statistically significant (Fig. 4A). These data indicated that SMAD3 can act independently of the 8-bp SBE to regulate murine Fshb, at least in heterologous cells.

Fig. 4.

An SBE adjacent to FBE3 mediates FOXL2/SMAD3 and activin A-induced murine Fshb promoter activity. A, HepG2 cells were transfected and treated as described in Fig. 2D with WT or the indicated mutant −1990/+1 murine Fshb-luc reporters. Data are means of four independent experiments (n = 4). Note that the data for the WT reporter are the same as those from Fig. 2D, because the analyses were run concurrently. B, EMSA using a WT radiolabeled −132/−92 probe containing the 4-bp SBE at −115/−112 and increasing concentrations of recombinant SMAD3-MH1 domain. In lane 5, 500× unlabeled homologous probe was included along with 800-ng recombinant protein. This lane is from the same gel and exposure, but intervening lanes were removed for purposes of presentation. Free probe appears at the bottom. C, LβT2 cells were transfected with WT or G-115T mutant murine −1990/+1 Fshb-luc reporters and stimulated where indicated with 1 nm activin A for 1 h. After ligand treatment, cells were cross-linked and harvested. Sonicated chromatin was immunoprecipitated with IgG or SMAD3 antibody. Input and precipitated DNA were analyzed by qPCR using primers specific to the proximal murine Fshb promoter. The qPCR signal was normalized within each condition as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent the mean (+sem) of the enrichment observed for each condition normalized to the nonspecific (IgG) condition in six independent experiments. D, LβT2 cells were transfected with the indicated −1990/+1 murine Fshb-luc reporters and treated with activin A for 24 h. Data are means (+sem) of four independent experiments (n = 4) and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (reporter x activin A).

Adjacent to FBE3 is a candidate 4-bp SBE (GTCT at −115/−112; the so-called −120 site) that might broker SMAD responses. To determine whether this element can bind SMAD, we first examined binding to a double-stranded probe containing the putative SBE [−132/−92; note that the same probe was erroneously labeled −130/−91 in Ref. 20 (see figure 6A)] in EMSA using nuclear extracts from activin A treated or untreated LβT2 cells. However, we failed to detect any induced complexes, nor did we observe supershifted or disrupted complexes when SMAD3 or SMAD4 antibodies were included in the binding reactions (data not shown). We recently reported binding of SMAD3 to an SBE adjacent to FBE2 in the porcine promoter, but this required coexpression of FOXL2 and activation of the activin signaling pathway (with ALK4TD) (21). Using a similar overexpression approach here, we again failed to detect SMAD3 or SMAD4 binding to the −132/−92 probe (data not shown).

We previously demonstrated SMAD3 binding to a low affinity SBE in the murine promoter using recombinant SMAD3-MH1 domain (20). Here, we observed the appearance of a single slower mobility complex relative to free −132/−92 probe when recombinant SMAD3-MH1 was included in the EMSA reaction (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 1 and 2). The intensity of the complex increased as more protein was inputted into the binding reaction (lanes 2–4). The binding was specific as it was competed by inclusion of 500-fold excess unlabeled homologous probe (lane 5). When we introduced a point mutation (G-115T) at the first position of the putative SBE in the −132/−92 probe, we failed to detect SMAD3-MH1 binding (data not shown). Importantly, we further showed that the same mutation did not significantly impair FOXL2 binding (Supplemental Fig. 6A). Although these data suggest that SMAD3 can bind the putative SBE in vitro, we next determined whether SMAD3 is recruited to this site in living cells using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). LβT2 cells were transfected with either WT or G-115T mutant Fshb promoter-reporters and then treated with activin A for 1 h. Activin A enhanced SMAD3 recruitment to the WT Fshb, but not the mutant, promoter (Fig. 4C). Although there was a trend for reduced SMAD3 recruitment to the mutant promoter under basal (no ligand) conditions, this was not statistically significant. These data suggest that the element at −115/−112 is a bona fide SBE and that SMAD3 is recruited after activin A treatment.

We next examined functional relevance of the −115/−112 SBE. When introduced into the −1990/+1 murine Fshb reporter, the G-115T mutation abrogated the synergistic effects of SMAD3 and FOXL2 in HepG2 cells (Fig. 4A). Similarly, in homologous LβT2 cell, the mutation almost completely blocked induction by activin A (Fig. 4D) or SMAD3 (Supplemental Fig. 6B). In the case of the activin A response, the inhibitory effect of the G-115T mutation was even more dramatic than that of the TA-263AT mutation (Fig. 4D). Collectively, these data suggest that the GTCT at −115/−112 is a functional SBE mediating the cooperative actions of SMAD and FOXL2 on murine Fshb promoter activity.

FBE3 is necessary but not sufficient for FOXL2/SMAD3-mediated transcription

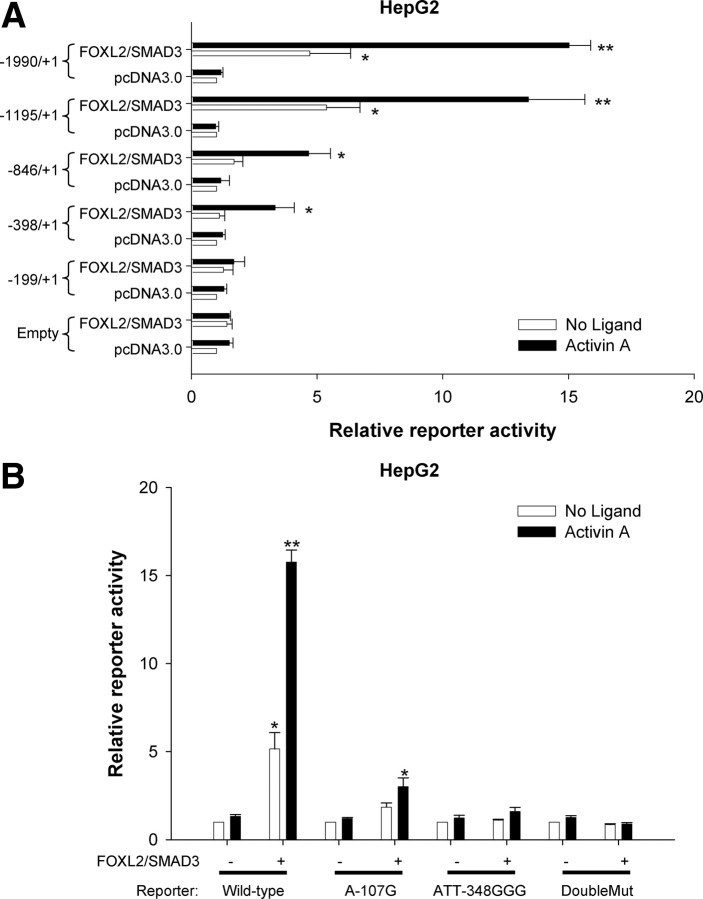

As shown in Fig. 2D, the A-107G mutation (in FBE3) greatly attenuated the effects of activin A, SMAD3, and FOXL2 on reporter activity in HepG2 cells. The residual activity might reflect incomplete blockade of FOXL2 binding by the mutation and/or the contribution of other cis-elements to the response. To address the latter possibility, we compared the effects of activin A/SMAD3/FOXL2 on promoter-reporters of different lengths (truncated from the 5′ end). Truncation from −1990 to −1195 did not appreciably alter the ligand-dependent or ligand-independent effects of SMAD3/FOXL2 (Fig. 5A). Further truncation to −846 abrogated the ligand-independent effect, whereas ligand-dependent activation remained intact. This pattern of activity was also observed when the promoter was truncated to −398. Further truncation to −199 completely blocked both activin A-dependent and activin A-independent promoter activation. Similar results were observed in LβT2 cells transfected with SMAD3 and treated with activin A (Supplemental Fig. 7). These data suggested that the SBE/FBE3 element (which is intact in the −199/+1 construct) is necessary, but not sufficient, for activin A-induced promoter activity. The putative FBE2/SBE element is also contained within the −199/+1 reporter and therefore was also insufficient for the response (see also Fig. 2). In contrast, the FBE1 site exists in the interval between −398 and −199 and therefore might play a role. To test this possibility, we introduced the A-107G (FBE3 site) and ATT-348GGG (FBE1 site) mutations into the −1990/+1 reporter alone and in combination and examined their effects on activin A/SMAD3/FOXL2-mediated promoter activity in HepG2 cells (Fig. 5B). Both mutations significantly impaired the ligand-dependent response (WT, 15.8-fold; A-107G, 3-fold; and ATT-348GGG, 1.6-fold). When both mutations were present, the response was completely blocked (0.9-fold). Similarly, in LβT2 cells, the combination of the two mutations completely abrogated the activin A response (Supplemental Fig. 3A). These data suggest that both FBE3 and FBE1 contribute to activin A/SMAD3/FOXL2-mediated promoter activity.

Fig. 5.

FBE3 is necessary but not sufficient for activin A/FOXL2/SMAD3-stimulated Fshb transcription. A, HepG2 cells were transfected with the indicated murine Fshb-luc reporters or with the empty reporter vector, pGL3-Basic. Cells were cotransfected with pcDNA3.0 or a combination of FOXL2 and SMAD3. Finally, cells were treated or not with 1 nm activin A overnight in serum-free conditions. The data were derived from four independent experiments (mean + sem, n = 4). Statistics were performed separately for each reporter using two-way ANOVA (FOXL2/SMAD3 x activin A). Note that the data for the −1990/+1 and −1195/+1 reporters were log transformed before analysis. B, HepG2 cells were transfected and treated as described in Fig. 2D with WT or the indicated mutant −1990/+1 murine Fshb-luc reporters. Data are means of three independent experiments (n = 3). DoubleMut refers to a construct containing both the A-107G and ATT-348GGG mutations.

The FOXL2, but not PBX1/PREP1, binding site is required for activin A-induced promoter activity

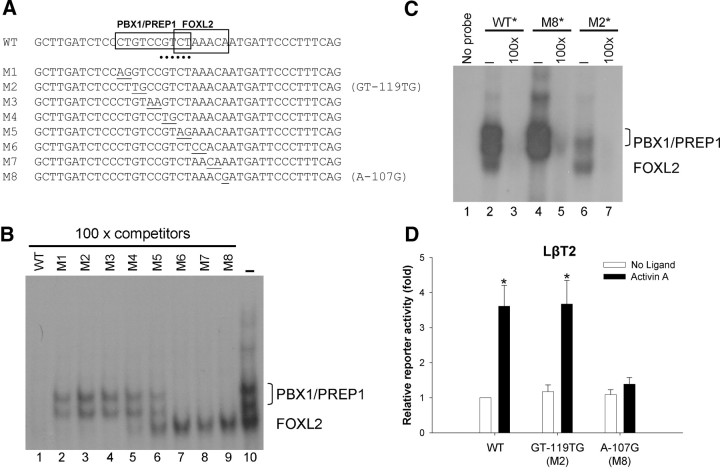

Although our data suggested that FOXL2 binding to FBE3 is critical for activin A induction of murine Fshb promoter activity, others have suggested an essential role for PBX1/PREP1 binding within the same promoter region (23). To clarify the relative roles of the different transcription factor binding sites, we first mapped nucleotides mediating FOXL2 vs. PBX1/PREP1 binding using EMSA (see probe sequences in Fig. 6A). As shown in Fig. 6B, incubation of LβT2 nuclear extracts with the −132/−92 probe led to the formation of three specific complexes (compare lanes 1 and 10). We showed previously, by supershift experiments, that the fastest migrating of the complexes contains FOXL2 and confirmed that again here (see figure 7C in Ref. 20) (data not shown). The other two complexes strongly resembled the PBX1/PREP1 doublet reported to bind this region of the ovine and murine promoters (23). Indeed, these two complexes (but not FOXL2) were supershifted by a PREP1 antibody (Supplemental Fig. 8A). We next used scanning block mutations (Fig. 6A) in competitor −132/−92 probes to define nucleotides mediating PBX1/PREP1 vs. FOXL2 binding. Probes bearing mutations 1 (M1) through M5 (M1–M5) failed to compete completely for the PBX1/PREP1 complexes, suggesting that nucleotides −121/−112 were required for PBX1/PREP1 binding. These basepairs correspond to −136/−127 of the ovine promoter and −136/−125 was previously suggested to mediate PBX1/PREP1 binding therein (23). In contrast, competitor probes M5–M8 (and M4 to a lesser extent) failed to compete for the FOXL2 complex, suggesting that nucleotides −113/−107 mediated FOXL2 binding. To further confirm these results, we radiolabeled mutant probes M2 and M8 and examined their abilities to bind the different proteins relative to the WT probe. As predicted by the competitor results, probe M2 (GT-119TG) retained the ability to bind FOXL2 but showed a significant impairment in PBX1/PREP1 binding (Fig. 6C, compare lanes 2 and 6). In contrast, probe M8 (A-107G) failed to bind FOXL2 as previously reported (20), but could still bind PBX1/PREP1 (Fig. 6C, lanes 2 and 4). We next introduced the M2 and M8 mutations in the context of a murine Fshb promoter-reporter and examined their effects on activin A-stimulated activity in LβT2 cells. We again observed abrogation of the activin A response in the reporter bearing the M8 (A-107G) mutation (Fig. 6D), which blocks FOXL2 binding to FBE3. In contrast, the M2 mutation (GT-119TG), which attenuated PBX1/PREP1 binding, had no effect on activin A-stimulated reporter activity (Fig. 6D). These data suggest that the FOXL2, but not PBX1/PREP1, binding site is required for activin A induction of the murine Fshb promoter in homologous cells.

Fig. 6.

The FBE3, but not PBX1/PREP1, cis-element is required for activin A-induced Fshb promoter activity. A, Sequences of WT and mutant (M) −132/−92 DNA probes used in EMSA (only the sense strand is shown). At the top, the basepairs mediating PBX1/PREP1 or FOXL2 binding are boxed and labeled. The basepairs modified in the eight mutant probes are underlined. The relative position of the SBE at −115/−112 is indicated with a dashed line. B, EMSA with the radiolabeled −132/−92 WT probe and LβT2 nuclear extracts. The three prominent DNA/protein complexes observed in the absence of competitor DNA are seen in lane 10 and labeled at the right. WT and the eight mutant probes (see A) were used as unlabeled competitors (at 100-fold molar excess) in the analysis (lanes 1–9). Free probe was run off the gel. C, The EMSA was repeated as in B using radiolabeled WT (lanes 2 and 3), M8 (lanes 4 and 5), and M2 (lanes 6 and 7) probes. Specificity of binding was assessed using 100-fold molar excess of the corresponding unlabeled probe (lanes 3, 5, and 7). D, Reporter assays were performed as described in Fig. 2E with WT or mutant −355/+1 murine Fshb-luc constructs. Data reflect the means (+sem) of three independent experiments (n = 3) and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and pair-wise comparisons (Tukey) of the significant interaction.

Discussion

We and others previously demonstrated that activins signal via SMAD proteins and the forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 to regulate Fshb gene expression in gonadotrope cells. Here, we show that SMAD and FOXL2 work in concert to regulate murine Fshb via an activin responsive cis-element containing binding sites for both SMAD and FOXL2. This element is conserved in mammals and therefore may define a common mechanism across species. The data further suggest that, in contrast to an earlier report (23), a proximal PBX1/PREP1 binding site may not play a significant role in activin A induction of murine Fshb expression.

To date, three FBEs have been identified in the proximal murine Fshb promoter. The data presented here strongly suggest that only the most proximal of the three (referred to as FBE3 in this communication) is absolutely required for activin A induction of murine Fshb promoter-reporters in homologous LβT2 cells. The most distal of the three sites [called FBE1 here and −350 previously (26)] appears to play a modulatory rather than necessary role for the activin response in LβT2 cells in our hands. The third site (FBE2) plays no observable role in mouse (Fig. 2). FOXL2 must bind FBE3 to mediate its effects, but its binding alone is insufficient for trans-activation of the murine Fshb promoter (Fig. 1). Instead, FOXL2 stimulates promoter activity in concert with SMAD2, SMAD3, and SMAD4, which act via an adjacent SBE (at −115/−112) (Fig. 4). We previously showed that FOXL2 interacts with SMAD3 and promotes SMAD3 binding to an SBE adjacent to FBE2 in the porcine promoter (21). We therefore hypothesized that FOXL2 might similarly broker SMAD binding to the SBE adjacent to FBE3 in the murine promoter. However, we have been unsuccessful thus far in demonstrating this experimentally. Although the data presented show that SMAD3 can bind the SBE at −115/−112 in vitro and ex vivo (Fig. 4, B and C; also, see Ref. 16), the nature of the assays used here precludes an assessment of the extent to which this is impacted/facilitated by concomitant FOXL2 binding. Nonetheless, we observe that SMAD activation of promoter activity requires SMAD3 or SMAD4 DNA-binding activity (Fig. 3), an intact FBE3 (Fig. 2D), and FOXL2 with DNA-binding activity (Fig. 2A). The data further show that SMAD activity (in heterologous cells) depends more on the SBE at −115/−112 than the 8-bp SBE at −266/−259 (Fig. 4A). Overexpression analyses suggest that either SMAD3 or SMAD4 can broker SMAD complex binding to DNA (Fig. 3). Previous observations similarly indicate that SMAD4 must possess DNA-binding activity to mediate activin A induction of a murine Fshb reporter in homologous LβT2 cells (13). Collectively, the extant data suggest a model in which activins stimulate the formation of SMAD2/3/4 complexes that accumulate in the nucleus, interact with FOXL2 via SMAD3, and bind via FOXL2 and SMAD3 or SMAD4 to adjacent cis-elements in the proximal promoter. This binding then stimulates transcription via currently undetermined mechanisms. Whether FOXL2 is constitutively bound or induced to bind DNA is not yet clear. In some ChIP assays, we observed activin A-stimulated enrichment of FOXL2 at the proximal murine Fshb promoter. However, the results from these analyses were not sufficiently robust or reproducible to include here.

Although conserved, the extent to which the composite SBE/FBE3 site plays a role in other species awaits further analysis. Activin A induction of Fshb promoter activity has been most thoroughly investigated in mouse, rat, sheep, pig, and human (see review in Ref. 28). An alignment of the corresponding sequences across these species shows a high degree of conservation (Supplemental Fig. 9). The core FOXL2 binding site 5′-TAAACA-3′ is identical across all species, except sheep, where a cytosine replaces the thymine at the first position. The effect of this substitution on FOXL2 binding has not been reported (to our knowledge). However, a previous study that identified PBX1/PREP1 binding to the corresponding part of the ovine promoter did not observe a complex with the characteristic mobility of FOXL2 using LβT2 nuclear extracts in EMSA (23). This suggests that FOXL2 binding to the ovine promoter might be of lower affinity than to other species. We previously demonstrated FOXL2 binding to FBE3 in the porcine and human promoters (20). In the former case this binding is critical for maximal activin A-stimulated promoter activity (21). In our experience, human promoter-reporters show poor activin responsiveness in LβT2 cells (15, 20, 29). Therefore, it has been difficult to assess the extent to which FBE3 might play a role in regulation of human FSHB transcription. A recent report showed modest activin A induction and constitutively active ALK7 induction of human FSHB promoter activity in LβT2 cells and that both responses were abrogated by mutations in two presumptive FBEs (referred to as −223 and −164 sites) (26). The latter of the two sites, which corresponds to FBE2, binds FOXL2 with low affinity relative to the pig promoter, as we previously reported (20). In fact, substitution of a single basepair from the porcine FBE2 into the human promoter (C-165T) dramatically increases both FOXL2 binding affinity and activin A induction of a human FSHB reporter in LβT2 cells. With respect to the −223 site, the existing data must be interpreted with some caution. That is, the specific basepairs mediating FOXL2 binding were not shown, nor was it established if the mutations introduced actually disrupted FOXL2 binding. It is also important to note that the role of the FBE3 site was not examined in Ref. 26. Thus, more work is needed to establish functional roles for SBE/FBE3 in humans and other species (i.e. rats and sheep).

Although the data demonstrate a necessary role for the composite SBE/FBE3 site in activin A induction of the murine Fshb promoter in homologous cells (LβT2), as well as in the synergistic actions of activin A/SMAD3/FOXL2 in heterologous cells (HepG2) (Figs. 1–4), they also show that this element may not be sufficient for the response. Previous work from others and our lab shows limited, if any, effects of activin A treatment on promoter activity of reporter constructs terminating at about 250 bp upstream of the transcription start site (15, 16, 26). Similarly, here, truncation of the reporter from −398 to −199 abolished the effects of activin A/SMAD3/FOXL2 or activin A/SMAD3 on transcription in HepG2 and LβT2 cells, respectively, despite the fact that the SBE/FBE3 element (−115/−107) is located well within the −199 reporter. The 5′ deletion data in Fig. 5A highlight the importance of sequences between both −398/−199 and −1195/−846 in HepG2 cells. In the former case, we observed that FBE1 (at −348) plays a critical role for SMAD3/FOXL2 actions in HepG2 cells (Fig. 5B). In contrast, FBE1 appears less critical for the activin A response in LβT2 cells, at least when SBE/FBE3 is intact (Fig. 2E). The basis for the discrepancy is not clear at present. Certainly, it may demonstrate that the reconstitution system we developed in heterologous cells does not fully recapitulate regulatory mechanisms in homologous cells. Alternatively or in addition, it may suggest that activin A induction of murine Fshb promoter activity in homologous cells may also involve SMAD3/FOXL2-independent mechanisms. Indeed, knocking down either of these proteins in LβT2 cells typically results in a 50% reduction in activin A induction of the murine Fshb promoter (11, 15, 20). The heterologous system, by its very design, is limited to assessing the effects of SMAD and FOXL2 and may be quite accurate in this regard. For example, the FBE1 site mutation, although having a relatively minimal effect on the activin A response (Fig. 2E), strongly impairs SMAD3-induced promoter activity in LβT2 cells (26) (data not shown). Thus, although the SBE/FBE3 element might be a general integrator of activin signaling via SMAD, FOXL2, and currently unidentified pathways/proteins, FBE1 might be important principally for the SMAD/FOXL2 component of the response. Future investigations are needed to identify SMAD/FOXL2-independent mechanisms underlying activin-regulated Fshb expression (e.g. Ref. 19). Similarly, more work is needed to establish how the promoter sequence between −1195 and −846 contributes to the activin A and/or SMAD3/FOXL2 responses, although this region might be more relevant in heterologous than homologous cells.

Previous data suggested that PBX1/PREP1 binding to the proximal ovine and murine Fshb promoters, in the vicinity of the composite SBE/FBE3 site, might be critical for activin A-regulated transcription (23). Although the data convincingly demonstrated PBX1/PREP1 binding to this part of the promoter (which we confirmed here), functional roles for the PBX1/PREP1 proteins themselves were not definitively established (e.g. by knocking down protein expression). In addition, the promoter mutation introduced into the ovine and murine promoters (GTCT→GTAG), which significantly inhibited activin A induction, would be predicted to affect SMAD and FOXL2 in addition to PBX1/PREP1 binding (e.g. see mutation M5 in Fig. 6B). Therefore, it was unclear whether the previously observed inhibitory effects were attributable to disrupted PBX1/PREP1, SMAD, and/or FOXL2 binding. Here, we defined specific basepairs mediating PBX1/PREP1, SMAD, and FOXL2 binding. The data demonstrate that mutations specifically disrupting SMAD (Fig. 4) or FOXL2 (Figs. 2 and 6), but not PBX1/PREP1 (Fig. 6), binding impaired activin A-regulated promoter activity. Because PBX1/PREP1 proteins were neither knocked down here nor in the previous report (23), we cannot definitively rule in or out a role for these proteins in activin A-stimulated Fshb promoter activity. However, the data clearly show that PBX1/PREP1 binding to this part of the promoter is dispensable for activin A induction of promoter activity (i.e. because the M2 mutation in Fig. 6, C and D, which affects PBX1/PREP1, but neither SMAD nor FOXL2 binding, had no effect on the activin A response). Instead, the inhibitory effect of the CT to AG mutation previously attributed to impaired PBX1/PREP1 binding more likely reflects disruption of SMAD and/or FOXL2 binding. Based on all of these data, we suggest that FOXL2 and SMAD, but not PBX1/PREP1, must bind to this part of the murine Fshb promoter to mediate the activin response.

In summary, we describe a composite SMAD and FOXL2 binding element in the proximal Fshb promoter that is required for activin A induction of murine Fshb transcription. Given the conservation of this promoter region, it seems likely that it functions to mediate activin stimulation of Fshb/FSHB in many, if not most, mammalian species. Indeed, previous data from both our and other labs are consistent with this hypothesis. More work is needed to define how FOXL2/SMAD complex binding to this response element modifies chromatin structure and promotes transcription initiation. In addition, in vivo data are required to confirm the roles of FOXL2 and its binding site(s) in activin-regulated Fshb expression beyond the cell line models used here.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

T4 polynucleotide kinase, fetal bovine serum, gentamycin, Platinum SYBR Green quantitative PCR (qPCR) SuperMix-UDG, TRIzol reagent, Plus reagent, Lipofectamine, and Lipofectamine 2000 were all from Invitrogen (Burlington, Ontario, Canada); 5× passive lysis buffer was from Promega (Madison, WI). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Deoxynucleotide triphosphates were from Wisent, Inc. (St-Bruno, Quebec, Canada). [γ-32P] ATP was from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA). Protease inhibitor tablets (complete Mini) were purchased from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). Aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin, phenylmethylsulphonylfluoride, DL-dithiothreitol, l-glutathione, isopropyl thio-β-D-galactoside, anti-FLAG (F7425), and β-actin (ACTB, A5316) antibodies were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Protein A/G PLUS-agarose (sc-2003), PREP1 (sc-25282X), and SMAD3 (sc-8332X) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Glutathione sepharose 4B beads were from Amersham Biosciences (Uppsala, Sweden). Foxl2 (siGENOME D-043309-02), Smad4 (siGENOME D-040687-02), and control (siGENOME nontargeting siRNA#5; D-001210-05) were from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO).

Constructs

The murine WT −1990/+1 Fshb-luc, −1195/+1 Fshb-luc, and mutant −1990/+1 Fshb-luc reporters (A-107G, TA-263AT) and untagged-mouse SMAD3 expression vector were described previously (11). The WT and A-107G −355/+1 Fshb-luc reporters, FLAG-murine FOXL2, and FLAG-FOXL2 siRNA resistant expression vectors were described in Ref. 20. The WT murine −199/+1 Fshb-luc was described in Ref. 30. The murine WT −846/+1 Fshb-luc and −398/+1 Fshb-luc reporters and SMAD4-K88R expression vector were described in Ref. 15. The siRNA-resistant SMAD4 expression vector was described in Ref. 29. The FLAG-FOXL2-R99A expression vector was described in Ref. 21. HA-murine FOXL2 (from Colin Clay, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO) (31), HA-rat ALK4TD and FLAG-human SMAD2 (from Teresa Woodruff, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL) (11), FLAG-human SMAD3 (from Yan Chen, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN) (11), FLAG-murine SMAD4 and FLAG-human SMAD3-K81R (from C. H. Heldin, The Ludwig Institute, Uppsala, Sweden) (27), glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-SMAD3-MH1 (from Bert Vogelstein, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) (32) expression constructs were all described previously. All novel mutant reporters described here were generated using the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and the primers indicated in Supplemental Table 1. The sequences of all constructs were verified (the McGill University and Genome Quebec Innovation Centre). It should be noted that the putative SBEs (AGAC and GTCT) characterized as the −153 and −120 sites (16, 23) are actually positioned at −148/−145 and −115/−112 relative to the start of transcription but are referred to here as −153 and −120 for purposes of consistency. We previously mapped the start of transcription by 5′ RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) of cDNA from LβT2 cells (11) and are therefore confident in the numbering scheme used here.

Cell culture, transfections, and reporter assays

LβT2 cells (gift from Pamela Mellon, University of California, San Diego, CA) were cultured at 37 C/5% CO2 in DMEM with 4.5 g/liter glucose (Multicell; Wisent, Inc.). HepG2 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured at 37 C/5% CO2 Eagle's minimum essential media with Earle's balanced salt, nonessential amino acids, and sodium pyruvate (Multicell; Wisent, Inc.). CHO cells (gift from Patricia Morris, Population Council, New York, NY) were cultured at 37 C/5% CO2 in DMEM/F-12 Ham's media (1:1) with 2.5 nm l-glutamine, 15 nm HEPES, and 14 nm sodium bicarbonate from HyClone (South Logan, UT).

For reporter assays, LβT2 cells were seeded in 48-well culture dishes at 0.75 × 105 cells per well. HepG2 cells were seeded in 48-well plates at 2.5 × 104 cells per well. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 as described previously (20, 30, 33). Briefly, for reporter assays in 48-well plates, 225 ng of the reporter along with 4.15 ng of FOXL2 and/or 25 ng of the indicated SMAD expression constructs were transfected per well. ALK4TD was cotransfected at 10 ng per well where indicated. In RNA interference experiments, siRNA (5 nmol/liter) were transfected along with other constructs. DNA was balanced across the treatments with empty vector. Cells were changed into serum-free media 24 h after transfection, and in some experiments, cells were stimulated or not with 1 nm recombinant human activin A (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Cells were harvested approximately 48 h after transfection and luciferase assays performed as described previously (13).

Recombinant protein expression

BL21 cells expressing GST-SMAD3-MH1 were grown in 2YT media for 2 h and then induced with 0.1 mm of isopropyl thio-β-D-galactoside for 4 h at 37 C. Bacterial cultures were then sonicated and the soluble fraction purified over glutathione sepharose beads. The purified recombinant GST-SMAD3-MH1 was then eluted with GST elution buffer [20 mm l-glutathione, and 50 mm Tris (pH 8)].

Western blotting

HepG2 cells in 10-cm dishes were transfected as indicated and whole-cell extracts prepared in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors. Samples were processed for Western blotting as described previously (11).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

LβT2 or HepG2 nuclear proteins were extracted as previously described (20, 33). EMSA were performed using previously described procedures with minor modifications (15, 20, 27). Briefly, nuclear proteins (3–5 μg) or recombinant protein (0–800 ng) were incubated at room temperature with 100 fmol of 32P-ATP end-labeled double-stranded probes corresponding to −132/−92 of the murine Fshb promoter in 25 mmol/liter HEPES (pH 7.2), 150 mmol/liter KCl, 5 mmol/liter dithiothreitol, 12.5% glycerol, and 1 μg of salmon sperm DNA for 30 min. In competition experiments, reactions were assembled at room temperature and incubated for 10 min with 100- to 500-fold excess unlabeled (cold) competitor before the addition of the radiolabeled probe. Gels were run for 3 h at 4 C, dried, and exposed to x-ray film. Sequences of the oligonucleotide probes are indicated Supplemental Table 1 and Fig. 6A.

Real-time RT-PCR

LβT2 cells were seeded in six-well plates (1 × 106 cells per well) and transfected with 1 μg/well pcDNA3.0 or SMAD3 in the presence of 5 nmol/liter (final concentration) control or Foxl2 siRNA with Lipofectamine/Plus for 6 h as indicated. Cells were then cultured in complete media for 48 h before extraction of total RNA using TRIzol as described previously (11). Reverse transcription followed by real-time qPCR was performed in triplicate using SYBR green qPCR master mix as described in Ref. 33. Fshb mRNA expression was determined using the relative standard curve method and quantified by calculating the ratio of Fshb/Rpl19 mRNA as previously described (20). Each condition was performed in duplicate and the experiment repeated three times.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

LβT2 cells in 10-cm dishes were transfected with the murine −1990/+1 Fshb-luc WT or G-115T mutant construct and treated for 1 h with 1 nmol/liter activin A. After treatment, formaldehyde was added to a final concentration of 1.42% and cross-linking performed for 10 min at room temperature. The cross-linking reaction was quenched with 125 mmol/liter glycine for 5 min. Cells were then lysed in 500 μl lysis buffer [1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1 mmol/liter EDTA, 50 nmol/liter Tris-HCl (pH 8), and protease inhibitors]. The lysates were sonicated with six 5-sec pulses at power 0.5 using a Misonix Sonicator 3000 (Misonix, Farmingdale, NY). The sonicated chromatin was spun for 10 min at 10,000 × g to pellet cellular debris. The protocol was adapted from the Fast ChIP protocol described in Refs. 34, 35. Half of the preblocked A/G-agarose bead slurry was used for preclearing with the sonicated chromatin for 30 min at 4 C. Beads were pelleted at 2000 × g for 1 min at 4 C. One percent of the volume of precleared chromatin was removed and kept as “input.” The remaining chromatin was divided in two and each half incubated for 30 min in an ultrasonic bath (Bransonic B1200-4) at 4 C with 5-μg anti-SMAD3 antibody or normal rabbit IgG. Next, 20 μl of the preblocked protein A/G-agarose bead slurry were added to each sample and allowed to rotate with for 45 min at 4 C. Beads were sequentially washed with low salt buffer [0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mmol/liter EDTA, 20 nmol/liter Tris (pH 8), and 150 mmol/liter NaCl], high salt buffer [0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mmol/liter EDTA, 20 nmol/liter Tris (pH 8), and 500 mmol/liter NaCl], and low salt buffer again. DNA was isolated with Chelex-100 resin, reverse cross-linked at 95 C, and subsequently digested with 20 μg of proteinase K. Immunoprecipitation products and input samples were analyzed in triplicate by real-time qPCR with SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix using a Corbett Rotor-Gene 6000 instrument. For quantification, the calculated chromatin concentration (determined with the ΔΔCt method) obtained with anti-SMAD3 or IgG condition was normalized with the input chromatin specific for each condition, then the SMAD3 fold enrichment was obtained by dividing the SMAD3 condition by the nonspecific condition.

Statistical analysis

All reporter experiments were repeated between three and five times (as indicated in the figure legends), with all treatments performed in triplicate. The data represent means (+sem) of independent experiments, such that n equals the number of experiments in each case. Statistical analyses were done as indicated in figure legends using Systat 10.2 (Systat, Chicago, IL). Significance was assessed relative to P < 0.05. In all panels with histograms, bars with asterisks differed significantly from those without asterisks. In addition, bars with different numbers of asterisks (e.g. * vs. **) differed from one another.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jérôme Fortin, Vikas Kumar, and Carlis Rejon for discussion and constructive feedback on an earlier draft of the manuscript; and Dr. Y. Chen, Dr. C. Clay, Dr. C.H. Heldin, Dr. P. Mellon, Dr. P. Morris, Dr. B. Vogelstein, and Dr. T. Woodruff for sharing reagents.

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant MOP 89991 (to D.J.B.). D.J.B. and S.T. hold a Chercheur-Boursier (Senior) and a doctoral fellowship, respectively, from the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ALK

- Activin receptor-like kinase

- ALK4TD

- ALK4-T206D

- bp

- basepair

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- FBE

- forkhead-binding element

- FOXL2

- forkhead transcription factor FOXL2

- GST

- glutathione-S-transferase

- M1

- mutation 1

- MH1

- Mad homology 1

- PBX1

- pre-B cell leukemia transcription factor 1

- PREP1

- PBX/knotted-1 homeobox-1

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- SBE

- SMAD-binding element

- SDS

- sodium dodecyl sulfate

- siRNA

- short interfering RNA

- SMAD

- homolog of Drosophila mothers against decapentaplegic

- WT

- wild type.

References

- 1. Abel MH , Wootton AN , Wilkins V , Huhtaniemi I , Knight PG , Charlton HM. 2000. The effect of a null mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene on mouse reproduction. Endocrinology 141:1795–1803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aittomäki K , Lucena JL , Pakarinen P , Sistonen P , Tapanainen J , Gromoll J , Kaskikari R , Sankila EM , Lehväslaiho H , Engel AR , Nieschlag E , Huhtaniemi I , de la Chapelle A. 1995. Mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene causes hereditary hypergonadotropic ovarian failure. Cell 82:959–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dierich A , Sairam MR , Monaco L , Fimia GM , Gansmuller A , LeMeur M , Sassone-Corsi P. 1998. Impairing follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) signaling in vivo: targeted disruption of the FSH receptor leads to aberrant gametogenesis and hormonal imbalance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:13612–13617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kumar TR , Wang Y , Lu N , Matzuk MM. 1997. Follicle stimulating hormone is required for ovarian follicle maturation but not male fertility. Nat Genet 15:201–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Layman LC , Lee EJ , Peak DB , Namnoum AB , Vu KV , van Lingen BL , Gray MR , McDonough PG , Reindollar RH , Jameson JL. 1997. Delayed puberty and hypogonadism caused by mutations in the follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene. N Engl J Med 337:607–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Layman LC , Porto AL , Xie J , da Motta LA , da Motta LD , Weiser W , Sluss PM. 2002. FSH β gene mutations in a female with partial breast development and a male sibling with normal puberty and azoospermia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:3702–3707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matthews CH , Borgato S , Beck-Peccoz P , Adams M , Tone Y , Gambino G , Casagrande S , Tedeschini G , Benedetti A , Chatterjee VK. 1993. Primary amenorrhoea and infertility due to a mutation in the β-subunit of follicle-stimulating hormone. Nat Genet 5:83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matzuk MM , Kumar TR , Bradley A. 1995. Different phenotypes for mice deficient in either activins or activin receptor type II. Nature 374:356–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weiss J , Guendner MJ , Halvorson LM , Jameson JL. 1995. Transcriptional activation of the follicle-stimulating hormone beta-subunit gene by activin. Endocrinology 136:1885–1891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abe Y , Minegishi T , Leung PC. 2004. Activin receptor signaling. Growth Factors 22:105–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bernard DJ. 2004. Both SMAD2 and SMAD3 mediate activin-stimulated expression of the follicle-stimulating hormone β subunit in mouse gonadotrope cells. Mol Endocrinol 18:606–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suszko MI , Balkin DM , Chen Y , Woodruff TK. 2005. Smad3 mediates activin-induced transcription of follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene. Mol Endocrinol 19:1849–1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang Y , Libasci V , Bernard DJ. 2010. Activin A induction of follicle-stimulating hormone β subunit transcription requires SMAD4 in immortalized gonadotropes. J Mol Endocrinol 44:349–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gregory SJ , Lacza CT , Detz AA , Xu S , Petrillo LA , Kaiser UB. 2005. Synergy between activin A and gonadotropin-releasing hormone in transcriptional activation of the rat follicle-stimulating hormone-β gene. Mol Endocrinol 19:237–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lamba P , Santos MM , Philips DP , Bernard DJ. 2006. Acute regulation of murine follicle-stimulating hormone β subunit transcription by activin A. J Mol Endocrinol 36:201–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McGillivray SM , Thackray VG , Coss D , Mellon PL. 2007. Activin and glucocorticoids synergistically activate follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene expression in the immortalized LβT2 gonadotrope cell line. Endocrinology 148:762–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Suszko MI , Lo DJ , Suh H , Camper SA , Woodruff TK. 2003. Regulation of the rat follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit promoter by activin. Mol Endocrinol 17:318–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Su P , Shafiee-Kermani F , Gore AJ , Jia J , Wu JC , Miller WL. 2007. Expression and regulation of the β-subunit of ovine follicle-stimulating hormone relies heavily on a promoter sequence likely to bind Smad-associated proteins. Endocrinology 148:4500–4508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Safwat N , Ninomiya-Tsuji J , Gore AJ , Miller WL. 2005. Transforming growth factor β-activated kinase 1 is a key mediator of ovine follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit expression. Endocrinology 146:4814–4824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lamba P , Fortin J , Tran S , Wang Y , Bernard DJ. 2009. A novel role for the forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 in activin A-regulated follicle-stimulating hormone β subunit transcription. Mol Endocrinol 23:1001–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lamba P , Wang Y , Tran S , Ouspenskaia T , Libasci V , Hébert TE , Miller GJ , Bernard DJ. 2010. Activin A regulates porcine follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit transcription via cooperative actions of SMADs and FOXL2. Endocrinology 151:5456–5467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. West BE , Parker GE , Savage JJ , Kiratipranon P , Toomey KS , Beach LR , Colvin SC , Sloop KW , Rhodes SJ. 2004. Regulation of the follicle-stimulating hormone β gene by the LHX3 LIM-homeodomain transcription factor. Endocrinology 145:4866–4879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bailey JS , Rave-Harel N , McGillivray SM , Coss D , Mellon PL. 2004. Activin regulation of the follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene involves Smads and the TALE homeodomain proteins Pbx1 and Prep1. Mol Endocrinol 18:1158–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Attisano L , Silvestri C , Izzi L , Labbé E. 2001. The transcriptional role of Smads and FAST (FoxH1) in TGFβ and activin signalling. Mol Cell Endocrinol 180:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shi Y , Wang YF , Jayaraman L , Yang H , Massagué J , Pavletich NP. 1998. Crystal structure of a Smad MH1 domain bound to DNA: insights on DNA binding in TGF-β signaling. Cell 94:585–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Corpuz PS , Lindaman LL , Mellon PL , Coss D. 2010. FoxL2 Is required for activin induction of the mouse and human follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit genes. Mol Endocrinol 24:1037–1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morén A , Itoh S , Moustakas A , Dijke P , Heldin CH. 2000. Functional consequences of tumorigenic missense mutations in the amino-terminal domain of Smad4. Oncogene 19:4396–4404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bernard DJ , Fortin J , Wang Y , Lamba P. 2010. Mechanisms of FSH synthesis: what we know, what we don't, and why you should care. Fert Steril 93:2465–2485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang Y , Fortin J , Lamba P , Bonomi M , Persani L , Roberson MS , Bernard DJ. 2008. Activator protein-1 and smad proteins synergistically regulate human follicle-stimulating hormone β-promoter activity. Endocrinology 149:5577–5591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ho CC , Bernard DJ. 2009. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 signals via BMPR1A to regulate murine follicle-stimulating hormone β subunit transcription. Biol Reprod 81:133–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ellsworth BS , Burns AT , Escudero KW , Duval DL , Nelson SE , Clay CM. 2003. The gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor activating sequence (GRAS) is a composite regulatory element that interacts with multiple classes of transcription factors including Smads, AP-1 and a forkhead DNA binding protein. Mol Cell Endocrinol 206:93–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zawel L , Dai JL , Buckhaults P , Zhou S , Kinzler KW , Vogelstein B , Kern SE. 1998. Human Smad3 and Smad4 are sequence-specific transcription activators. Mol Cell 1:611–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lamba P , Khivansara V , D'Alessio AC , Santos MM , Bernard DJ. 2008. Paired-like homeodomain transcription factors 1 and 2 regulate follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit transcription through a conserved cis-element. Endocrinology 149:3095–3108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nelson JD , Denisenko O , Bomsztyk K. 2006. Protocol for the fast chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) method. Nat Protoc 1:179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nelson JD , Denisenko O , Sova P , Bomsztyk K. 2006. Fast chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. Nucleic Acids Res 34:e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]