Abstract

Aberrant expression of androgen receptor (AR) coregulators has been linked to progression of prostate cancers to castration resistance. Using the repressed transactivator yeast two-hybrid system, we found that TATA binding protein-associated factor 1 (TAF1) interacted with the AR. In tissue microarrays, TAF1 was shown to steadily increase with duration of neoadjuvant androgen withdrawal and with progression to castration resistance. Glutathione S-transferase pulldown assays established that TAF1 bound through its acetylation and ubiquitin-activating/conjugating domains (E1/E2) directly to the AR N terminus. Coimmunoprecipitation and ChIP assays revealed colocalization of TAF1 and AR on the prostate-specific antigen promoter/enhancer in prostate cancer cells. With respect to modulation of AR activity, overexpression of TAF1 enhanced AR activity severalfold, whereas small interfering RNA knockdown of TAF1 significantly decreased AR transactivation. Although full-length TAF1 showed enhancement of both AR and some generic gene transcriptional activity, selective AR coactivator activity by TAF1 was demonstrated in transactivation experiments using cloned N-terminal kinase and E1/E2 functional domains. In keeping with AR coactivation by the ubiquitin-activating and -conjugating domain, TAF1 was found to greatly increase the cellular amount of polyubiquitinated AR. In conclusion, our results indicate that increased TAF1 expression is associated with progression of human prostate cancers to the lethal castration-resistant state. Because TAF1 is a coactivator of AR that binds and enhances AR transcriptional activity, its overexpression could be part of a compensatory mechanism adapted by cancer cells to overcome reduced levels of circulating androgens.

TAF1 is an androgen receptor coactivator whose overexpression in advanced prostate cancers may be part of a compensatory mechanism to overcome castration levels of androgens.

The androgen receptor (AR) plays a crucial role in the growth and development of prostate cancer (1, 2). In the absence of androgens, the AR exists in the cytoplasm as a transcriptionally inactive multiplex of chaperones (3). Upon androgen binding, it undergoes a conformational change, forms homodimers, and is translocated into the nucleus where it binds cognate response elements upstream of target genes (4, 5). The AR recruits coregulator proteins, chromatin-remodeling complexes (6, 7, 8) and also components of the general transcription machinery including transcription factor IIF (TFIIF) (9) and TFIIH (10), that ultimately results in initiation and elongation of transcription.

The AR is a member of the steroid receptor family that shares common functional domains and structures (11, 12). This family of receptors has 1) a ligand-binding domain (LBD) located in the C-terminal region, 2) a hinge region, 3) a centrally located DNA-binding domain (DBD), and 4) an N-terminal domain (NTD). Among members of this family, the NTD has the highest degree of amino acid sequence variability, suggesting that this region has a major role in AR-specific transcription regulation (13, 14, 15, 16). To identify novel NTD-interacting proteins, we employed the Tup1 repressed transactivator (RTA) yeast two-hybrid system (17), which has previously been used by our laboratory to identify l-dopa decarboxylase and cyclin G-associated kinase as AR-interacting proteins (18, 19). Using this system, TATA-binding protein (TBP)-associated factor 1 (TAF1) was identified as a previously unreported AR-interacting protein.

TAF1 (formerly referred to as TAF II250 or CCG1) is part of the TFIID complex, which consists of TBP and approximately 15 TAFs. TAFs, including TAF1, mediate activator-dependent transcription in a promoter- and tissue-specific manner (20, 21, 22). The TAF1 gene contains 38 exons that span 98 kb of genomic DNA on chromosome X and encode an approximately 6-kb mRNA. The TAF1 protein possesses intrinsic protein kinase activity (23), histone acetyltransferase activity (HAT) (24), and ubiquitin-activating and -conjugating activity (E1/E2) (25). The TAF1 kinase is bipartite, consisting of N- and C-terminal kinase domains (NTK and CTK, respectively). TAF1 is capable of autophosphorylation as well as specific phosphorylation of TFIIF (23), p53 (26), and Mdm2 protooncogene (27). TAF1 also binds and modulates transcriptional activity of proteins such as c-Jun (28), Mdm2 (29), and cyclin D1 (30), which are known to influence AR activity and hence prostate cancer progression (31, 32, 33).

In the present study, the expression of TAF1 was assessed in prostate cancer tissue at different stages of androgen withdrawal by neo-adjuvant hormone therapy (NHT) using tissue microarray analysis. The result showed that increased TAF1 expression was associated with duration of NHT, suggesting a crucial role for TAF1 in castration-resistant (CR) prostate cancer. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assays were performed and confirmed that TAF1 binds to the NTD of AR through the E1/E2 and HAT domains. In addition, we demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays that TAF1 and AR bind in the nucleus and associate with the androgen response element (ARE) in the proximal/enhance promoter of the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) gene in the presence of androgen. We also found that TAF1 acts as a coactivator and enhances AR transcriptional activity through its NTK and E1/E2 domains without influencing the general transcriptional activity of a non-androgen-responsive promoter. By using in-cell and in-tube ubiquitination assays, our findings also suggest that TAF1 can ubiquitinate AR.

Results

TAF1 expression increases with prolonged hormone treatment and with progression to CR prostate cancer

Recent evidence suggests that AR-specific gene regulation may occur as a consequence of interactions with unique coregulatory proteins (34). Because the NTD of AR is the least conserved nuclear receptor domain, protein interactions in this region may dictate receptor-specific coregulation capacity. To identify novel AR-interacting proteins, the NTD of AR was used as bait in the RTA yeast two-hybrid system (17) to screen a LNCaP prostate carcinoma cell line cDNA library. The RTA system allows for screening with a bait protein that has intrinsic transactivation function, such as the NTD of AR (19). We have identified several clones that code for AR-interacting proteins, one of which was the COOH terminus of TAF1 (amino acids 1118-1893, bp 3406-6138; GenBank accession no. NM 004606).

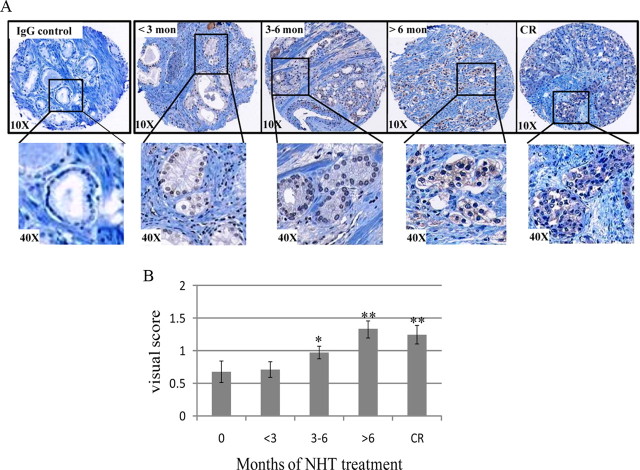

We next wanted to identify whether TAF1 has a role in advanced prostate cancer. The expression profile of TAF1 during disease progression was assessed in patients who had undergone varying lengths of NHT before radical prostatectomy or autopsy, using NHT tissue microarrays (18, 35). Each NHT array is comprised of 336 tumor biopsies, which were obtained from triplicate cores of 112 tumors. A control tissue microarray slide was incubated with normal IgG, as described in Materials and Methods. Staining intensity was scored visually by a pathologist on a scale from 0–3, ranging from no staining (score 0) to very intense staining (score 3) (18, 36). Figure 1A shows representative histology pictures of four test groups (<3 months NHT, 3–6 months NHT, >6 months NHT, and CR state), and Fig. 1B shows visual scoring analysis of the whole NHT array. Interestingly, we found the longer the NHT treatment, the higher the level of TAF1 protein. TAF1 expression of individual cores was compared between the different treatment groups, and its level was found to be significantly higher in the 3–6 months NHT over the untreated group (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, there was an additional increase in TAF1 expression with longer NHT and with CR progression. Thus, increased levels of TAF1 expression are associated with progression to CR and may have potential clinical value as a biomarker or a therapeutic target for advanced prostate cancer.

Fig. 1.

Tissue microarray analysis TAF1 expression in prostate cancer. A, A NHT tissue microarray was stained with an antibody that recognizes TAF1 (Abcam) or rabbit IgG (negative control). Staining intensity was scored from 0–3 by a pathologist. Slides were visualized under ×10 magnification, and further magnification (×40) of delineated areas is shown. B, Visual score of samples with TAF1 staining intensity of 0–3 is given for each treatment group. *, Significant difference over 0 months; **, significant difference over 3–6 months.

TAF1 interacts with the N terminus of AR mainly through its HAT and E1/E2 domains

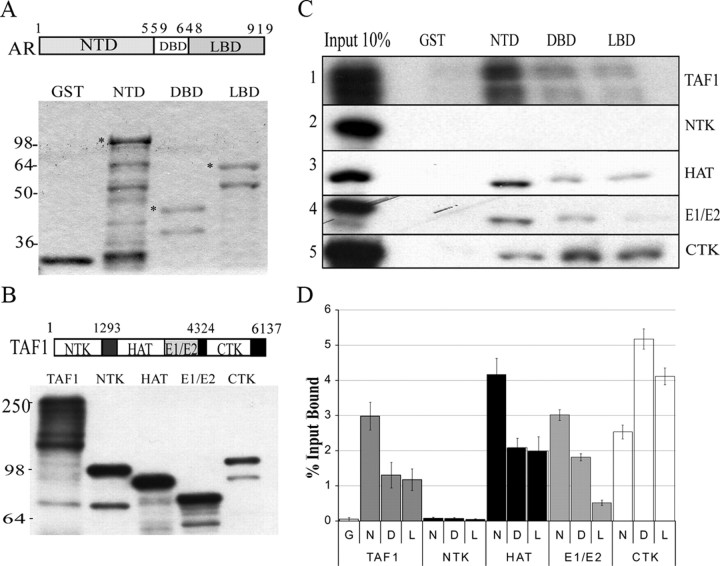

To confirm the AR/TAF1 interaction and to determine the domains involved, GST pulldown assays were performed using GST-fusion protein with AR/NTD1-559, DBD541-665, or LBD649-919 (Fig. 2). Purified GST-AR domains were verified for purity and concentration by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining (Fig. 2A). Equimolar amounts of nondegraded protein were determined for each of the GST protein products (asterisk in Fig. 2A) and used in pulldown assays to assess relative TAF1 binding to AR domains, as described before (19). Radiolabeled TAF1 and TAF1 truncated domains were generated in vitro and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography (Fig. 2B). The presence of multiple bands for radiolabeled proteins is due to the presence of several ATG sites within human TAF1 cDNA. Radiolabeled TAF1 (Fig. 2B, lane 1) was allowed to interact with GST protein or GST-AR fragments bound to agarose beads. As shown in Fig. 2C (top row), TAF1 did not interact with GST alone (lane 2), whereas it did bind to all domains of AR (lanes 3–5), with the strongest interaction being with the NTD of AR (lane 3).

Fig. 2.

TAF1 binds AR through HAT and E1/E2 domains in vitro. A, GST-fused AR domains were expressed in E. coli BL21 and purified using glutathione beads. Fusion protein-bound beads were eluted with sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. The eluent in each case was run alongside known amounts of BSA (ranging from 250–1000 ng) to generate a standard curve for protein concentrations. Equimolar amounts of nondegraded proteins (*) were used in GST pulldown assays. B, 35S-Radiolabeled TAF1 and its domains [N-terminal kinase (NTK), histone acetylation (HAT), ubiquitin activating/conjugating (E1/E2), and C terminal kinase (CTK)] were generated using in vitro transcription/translation kit and autoradiographed. C, GST pulldown assay. Equal volumes of 35S-labeled TAF1, 35S-labeled NTK, 35S-labeled HAT, 35S-labeled E1/E2, and 35S-labeled CTK were incubated with GST-AR fragments bound to agarose beads. GST alone coupled to agarose beads was used as negative control. D, Dried gels were also analyzed using a phosphorimaging screen. Quantity One software was used to obtain data (counts/mm2) for radiolabeled protein bands. All pulldowns were done in triplicate, normalized as a function of the percent input bound, and averaged. D, DBD; G, GST; L, LBD; N, NTD.

GST pulldown experiments were repeated with radiolabeled TAF1 domains (NTK, HAT, E1/E2, and CTK proteins; Fig. 2B) to identify domains essential for interaction between TAF1 and AR (Fig. 2C, rows 2–5). All domains except the NTK of TAF1 bind to GST fusion AR proteins with different affinities. We performed the above pulldown assay repeatedly with two more independent experiments and calculated an average percentage of total input bound to the GST-AR domains ([CNT*mm2, counts/mm2] bound/[CNT*mm2] input), as described in Materials and Methods. A summary of the quantified GST pulldown data (percentage of the input bound) for these TAF1 truncations and the full-length protein is shown in Fig. 2D. Similar to the full-length protein, HAT and E1/E2 domains interact most strongly with the NTD of AR, but the HAT domain binds this region with 1.5 times higher affinity. Although the CTK domain was originally identified as binding to the N terminus of AR by the RTA assays, this domain interacts more strongly to the DBD and LBD domains of AR. Taken together, these data demonstrate that TAF1 interacts directly with AR, confirming our RTA screening result. In addition, mapping the interaction domains of TAF1 and AR suggests that the HAT, E1/E2, and CTK domains of TAF1 are all involved in binding to AR. The pattern of binding of HAT and E1/E2 domains is similar to that seen with full-length TAF1, suggesting TAF1/AR interaction through these domains.

TAF1 interacts with AR within a prostate cancer cell line

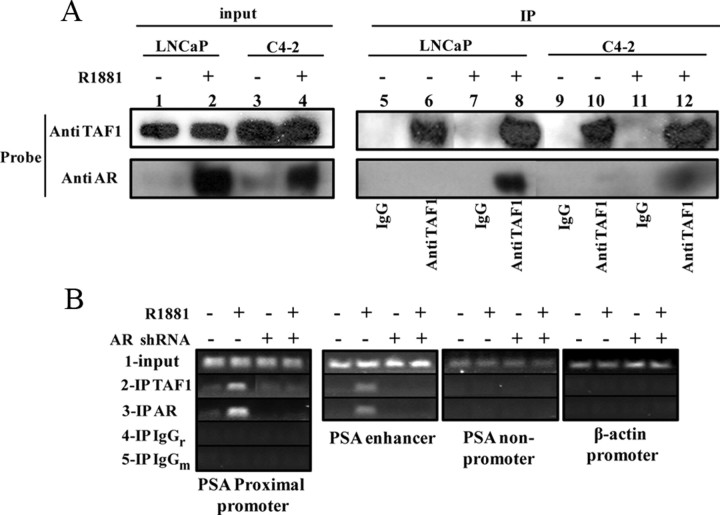

Human TAF1 protein has a molecular weight of 250,000 and is ubiquitously expressed in normal tissues, with highest expression levels in the spleen and testes (37). TAF1 is expressed in nuclei of all prostate cancer cell lines including LNCaP and C4-2 cells (data not shown). Because there are strong interactions between TAF1 and AR in vitro, using co-IP assays, these cells were used to confirm TAF1/AR interaction and to compare the pattern of TAF1/AR complex between androgen-dependent (LNCaP) and CR (C4-2) prostate cancer cells. LNCaP and C4-2 cells were respectively transfected with HA-TAF1 and treated with or without 1 nm of the synthetic androgen R1881. Using the Active Motif co-IP kit, 1 mg of nuclear extracts of cells [calculated by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay] were subjected to IP with an anti-TAF1 antibody and analyzed by Western blot for TAF1 and AR (Fig. 3A, top and bottom, respectively). As shown on the left (10% of total protein), the levels of TAF1 expression are the same in the presence or absence of hormone in both cell lines. In contrast, there is not much AR in the nuclear extracts of the LNCaP cells in the absence of hormone, whereas the total amount of nuclear AR is increased upon androgen treatment (lane 2 relative to lane 1, bottom). For the C4-2 cells, although there is an increase in the level of nuclear AR after androgen induction, we also observe a low level of nuclear AR in hormone- depleted conditions (lane 4 relative to lane 3, bottom), suggesting the presence of functional AR in hormone-depleted conditions. Upon IP of TAF1, the AR is coimmunoprecipitated with TAF1 in the presence of androgen in both cells, with the relatively stronger interaction within LNCaP cells (lane 8 compared with lane 12, bottom). Together, these results indicate that TAF1 and AR are in a complex within LNCaP and C4-2 cells in the presence of androgen.

Fig. 3.

TAF1 interacts with AR within a prostate cancer cell line. A, LNCaP or C4-2 cells were transiently transfected with HA-TAF1, grown in 5% CSS for 24 h and then treated with or without 1 nm R1881 (synthetic androgen) for 4 h. Nuclear proteins were extracted and TAF1 was immunoprecipitated (IP) followed by Western blot analysis, probing with anti-AR or -TAF1 antibodies. B, LN-shRNAAR or LN-shRNASC cells were grown in CSS for 24 h and then treated with DOX for 48 h followed by 4 h with or without 1 nm R1881 induction. Cells were then cross-linked and DNA sheared, and then the protein/DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated with anti-TAF1 or anti-AR and the promoter of the PSA proximal/enhancer were PCR amplified. The nonpromoter region of PSA and β-actin primers were used as negative controls for TAF1-enriched protein/DNA complexes. IgGm, Mouse IgG; IgGr, rabbit IgG.

Because TAF1 and AR interact in the nucleus and TAF1 is an essential player in the transcriptional activity of a number of genes (38), we used ChIP assays to investigate whether TAF1 can bind to the promoter/enhancer of the PSA and whether this binding is through AR (Fig. 3B). LNCaP cells that stably express either doxycycline (DOX)-inducible short hairpin RNA (shRNA) of the AR (LN-shRNAAR) or DOX-inducible scrambled shRNA (LN-shRNASC) were used as described before (39). Cells were grown in charcoal-stripped serum (CSS) and treated with DOX for 48 h followed by 4 h treatment with or without R1881. DNA and proteins were then cross-linked, lysed, sonicated, and then immunoprecipitated with anti-TAF1 antibody (row 2), AR (row 3), or an equivalent amount of normal rabbit/mouse IgG as negative controls (rows 4 and 5, respectively). The DNA was purified and used as a template for PCR of the PSA proximal promoter (first panel from left) and the enhancer (second panel). The result indicates that TAF1, like AR, binds with the PSA promoter/enhancer in the presence of androgen. This binding seems to be mainly AR dependent because when the AR is knocked down, there is no detectable PCR product at the enhancer and just faint bands at the proximal promoter. To determine whether the binding of TAF1 to the PSA promoter is specific, the purified DNA obtained after TAF1 IP was subjected to PCR for a nonpromoter region of the PSA promoter (third panel) as well as for β-actin promoter (fourth panel). The absence of detectable PCR products in these regions indicate that TAF1 binding to the PSA promoter was promoter and sequence specific. Together, our ChIP assay results suggest that TAF1 and AR associate at the PSA promoter/enhancer when the AR is transcriptionally active.

TAF1 enhances transcriptional activity of the AR

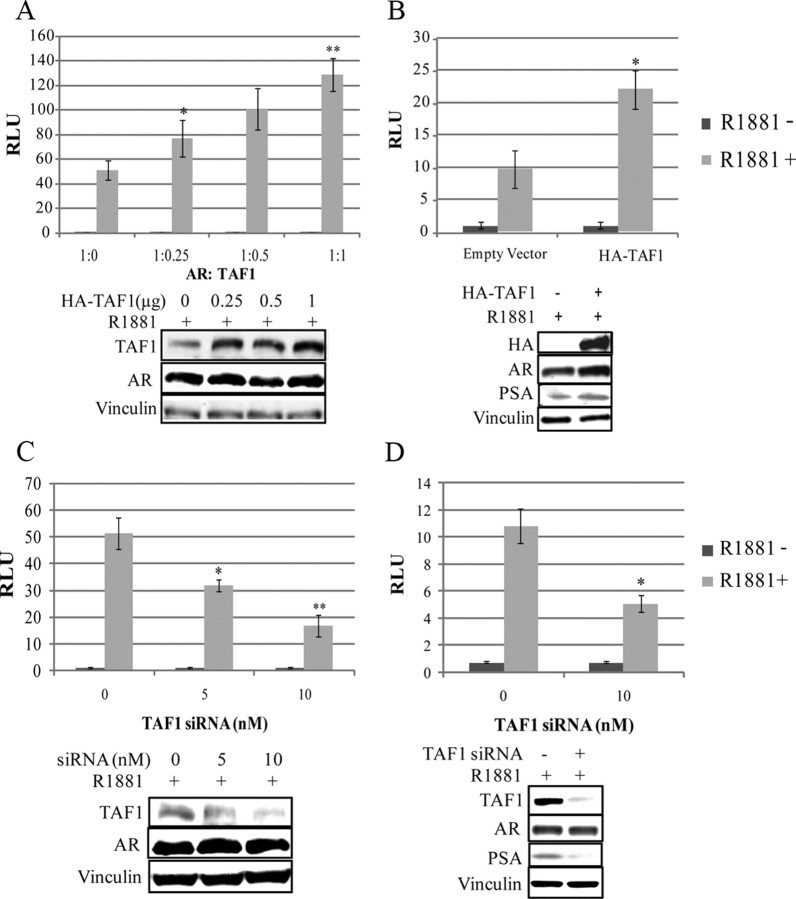

To determine the impact of AR-TAF1 interaction on AR transcriptional activity within cells, transient transfection assays were carried out in PC3 cells, which were cotransfected with increasing amounts of full-length TAF1 expression vector (pHA-TAF1), a constant amount of full-length AR expression vector, along with the pARR3tk-Luc reporter plasmid. Transfected cells were stimulated with 1 nm R1881or vehicle for 24 h and analyzed for luciferase activity (Fig. 4A). In the absence of exogenous TAF1, AR activity in PC3 cells was increased by 50-fold (±7) with the addition of androgen (1 nm R1881). Increasing amounts of TAF1 enhanced AR transactivation by up to an additional 2.6-fold (±0.5) (P < 0.005) in a dose-dependent manner when overexpressed in the presence of hormone. To confirm the results, LNCaP cells, which contain AR, were also transfected with pHA-TAF1 and the PSA-Luc reporter. Again, TAF1 could enhance AR transcriptional activity up to 2.3-fold (±0.7) in the presence of hormone (Fig. 4B). To further explore the role of TAF1 in AR-mediated transcription, these transactivation assays were repeated as described above except small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes were added to knock down endogenous TAF1 protein (Fig. 4, C and D). Decreasing the amount of endogenous TAF1 suppressed AR transactivation in the presence of hormone in a dose-dependent manner by 3-fold (±0.6) (P < 0.005) in AR-transfected PC3 cells using a pARR3tk-Luc reporter and by 2.1-fold (±0.3) in LNCaP cells using the PSA-Luc reporter. Western blot analysis confirmed that TAF1 protein levels were modulated in accordance with increasing levels of its expression construct or siRNA duplexes (Fig. 4). In addition, TAF1 protein levels are directly related to the endogenous PSA expression in LNCaP cells (Fig. 4, B and D). Together, these results suggest that the expression level of TAF1 correlates with AR activity.

Fig. 4.

TAF1 modulates AR transactivation. PC3 cells were cotransfected with 1.5 μg/well full-length AR (pAR6) and 0.2 μg/well pARR3-tk-Luc reporter, 0.1 μg/well pRLtk-Renilla, and increasing amounts of pHA-TAF1 (A) or increasing amounts of TAF1 siRNA duplexes (C). LNCaP cells were cotransfected with 1 μg/well pPSA-Luc, 0.1 μg/well pRLtk-Renilla, and 1 μg/well pCS2+HA-hTAF1 (B) or 10 nm TAF1 siRNA duplexes (D). Transfected cells were grown in the presence or absence of 1 nm R1881 for 24 h (A and B) or 48 h (C and D) before harvesting for luciferase assay and Western blot analysis. Luciferase units (RLU) are expressed relative to protein values for each sample (protein normalization was used due to TAF1, causing an increase in Renilla luciferase). All luciferase values are given as the mean (±sem) of triplicate readings. Graphs are representative of the three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 compared with empty vector control; **, P < 0.05 compared with *.

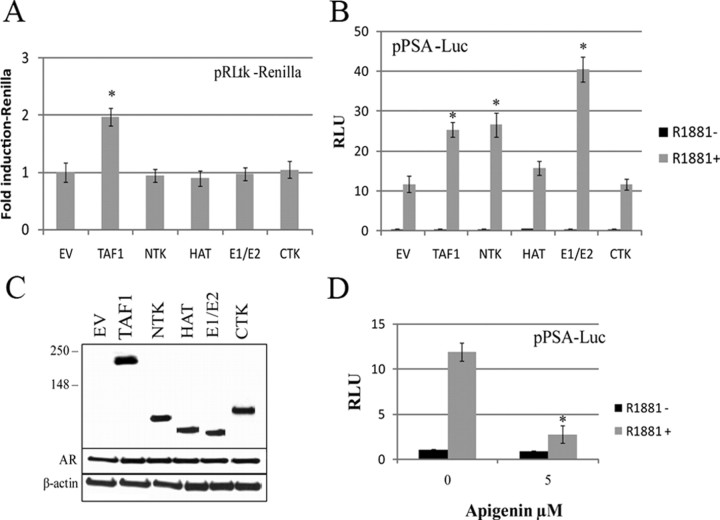

AR transcriptional activity is significantly enhanced by NTK or E1/E2

Because TAF1 is a member of the general transcription machinery complex, it is not surprising that it exerts its influence on promoters of different genes. In our transactivation assays, we found that increasing or decreasing TAF1 levels also resulted in increased or decreased thymidine kinase-renilla activity (pRLtk-Renilla). To differentiate the effect of TAF1 on AR from TAF1’s general effects on transcription and to determine which TAF1 domains are specifically involved in AR activation, we created expression vectors of the TAF1 domains and repeated the transfection experiments in LNCaP cells using the PSA-Luc reporter. In contrast to full-length TAF1, none of the individual TAF1 domains had any effect on the generic renilla construct with its pRLtk promoter, implying that general transcription is not affected (Fig. 5A). By comparison, although HAT and CTK domains had no significant effect on AR activity, NTK and the E1/E2 domains of TAF1 did enhance AR activity in an androgen-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). NTK significantly enhanced AR transactivation by 2.4-fold (±0.5), which is almost as much as the full-length TAF1. However, E1/E2 domain had an even greater effect, enhancing AR activity over 3.4-fold (±0.6). Figure 5C shows the relative expression levels of full-length TAF1 or its individual domains to AR and β-actin proteins.

Fig. 5.

NTK and E1/E2 of TAF specifically enhance AR transactivation. LNCaP cells were cotransfected with either pHA-TAF1 or one of its four domains (pV5-NTK, pV5-HAT, V5-E1/E2, or pV5-CTK) (1 μg/well) and the pPSA-Luc and pRLtk-Renilla. Empty vector (EV; 1 μg/well) was used as a control. Transfected cells were grown in the presence or absence of 1 nm R1881 for 24 h before harvesting for luciferase assay. A, Fold induction of renilla units in the presence of R1881 vs. the empty vector plotted for TAF1 or its individual domains. B, Luciferase units were normalized to protein plotted for PSA-luciferase. *, P < 0.05 compared with empty vector control. C, Western blot analysis for AR, β-actin, empty vector (EV), TAF1, NTK, HAT, E1/E2, and CTK. D, LNCaP cells were cotransfected with the pPSA-Luc and pRLtk-Renilla. Transfected cells were treated with or without 1 nm R1881 and 5 μm apigenin or vehicle for 24 h before harvesting for luciferase assay. Luciferase units were normalized to protein, and fold induction of luciferase activity was plotted against vehicle treatment.

Because NTK enhances AR transactivation, we tested the effect of apigenin, a TAF1 protein kinase inhibitor (26, 27), on AR transcriptional activity. Using the 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium assay, we found that apigenin at 5 μm does not affect LNCaP cell viability (data not shown). This concentration was then used to treat LNCaP cells transfected with the PSA-Luc reporter. As shown in Fig. 5D, AR activity is suppressed up to 4.3-fold (±0.6) in the presence of apigenin. We next tested whether TAF1 could phosphorylate AR, using in vitro kinase assays. TAF1 pulled down from HeLa cells with antibody was incubated with affinity-purified FLAG-AR protein from HeLa-AR cells (39) in the presence of [γ32P]ATP. Although we were able to show TAF1 autophosphorylates, consistent with reports by others (23) (data not shown), we could not detect AR phosphorylation by TAF1.

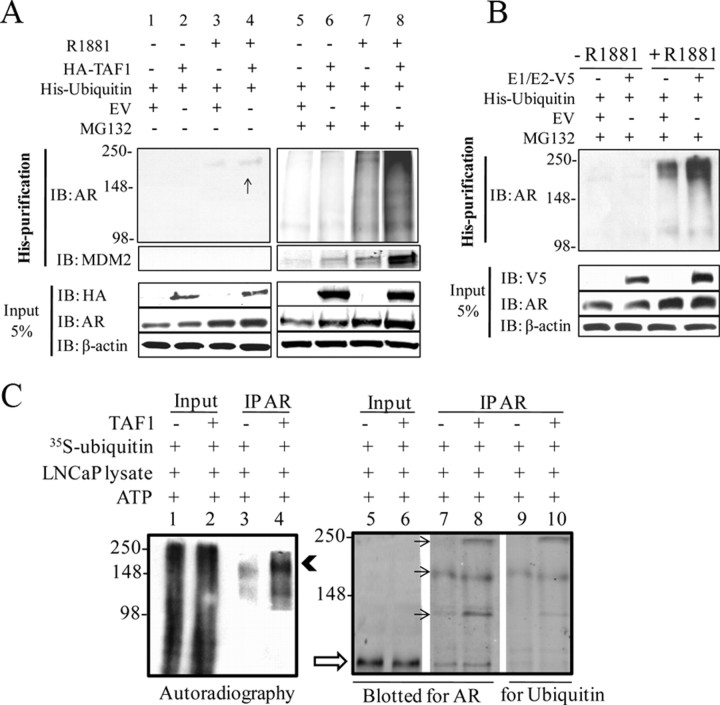

AR is ubiquitinated by TAF1

Because NTK does not bind to AR and the CTK and HAT domains do not enhance AR transcriptional activity, we focused on the E1/E2 domain, which binds to AR and has the most profound effect on its transactivation. Ubiquitination is a posttranslational modification that mediates the covalent conjugation of ubiquitin to protein substrates. The functional role of ubiquitination was originally considered to be the targeting of proteins to the proteasome for degradation. However, it is now known that ubiquitination regulates many other processes in the cell, including membrane trafficking, DNA repair, and transcription (40). AR is also a direct target for mono- and polyubiquitination (32, 41). To address whether TAF1 can ubiquitinate AR, LNCaP cells were cultured in 5% CSS medium for 24 h and then cotransfected with pHis6-Ubiquitin and either pHA-TAF1 or empty vector. Cells were then treated with 5% CSS medium with or without 1 nm R1881 followed by 6 h treatment with vehicle or MG132, a proteasome inhibitor. To show the His-ubiquitin conjugated status of AR in the presence and absence of MG132, after saving 5% input (Fig. 6A, lower panels), His- conjugated proteins were purified followed by a Western blot with antibody against AR. Figure 6A (lanes 1 and 2) shows that in the absence of MG132 and hormone, there is no His-conjugated AR. However, very faint bands appear in the presence of hormone and are slightly higher with overexpression of TAF1 (lane 4 vs. 3). Lanes 5–8 show the same order of experiments in the presence of proteasome inhibitor. As expected, there is no ubiquitination of AR in the absence of hormone, whereas the total amount of polyubiquitinated AR is increased with MG132 and R1881 treatment when TAF1 is overexpressed (lane 8 vs. 7). Because Mdm2 (an E3 ligase) is involved in the polyubiquitination and consequently degradation of AR (32), we wanted to see whether the Mdm2 protein could also be detected in this set of experiments. Hence, the same membrane was blotted with antibody against Mdm2. As shown in Fig. 6A (middle panels), the more ubiquitinated AR, the more Mdm2 within the protein complex. This suggests that through overexpression of TAF1, either the Mdm2 protein is also being ubiquitinated and targeted for degradation or TAF1 induces ubiquitination of AR through Mdm2.

Fig. 6.

TAF1 ubiquitinates AR. A, LNCaP cells were transfected with 2 μg pHis6-ubiquitin and either 6 μg pHA-TAF1 or empty vector. Cells were then treated with 5% CSS RPMI with or without 1 nm R1881 followed by 10 μm MG132 or vehicle for 6 h. After harvesting and lysing the cells in RIPA buffer, 5% of cell lysate was used as an input (lower panels), and the remainder was mixed with 50 μl Ni2+-NTA-agarose beads. The mixture was rotated at 4 C for 3 h and then affinity pulled down followed by Western blot analysis for AR and Mdm2 (upper and middle panels). The input was immunoblotted (IB) for HA, AR, and β-actin. The arrow shows the polyubiquitinated AR in the absence of MG132 and when TAF1 is overexpressed. B, Experiments were designed as above, except cells were transfected with the plasmid (p) V5 E1/E2 domain instead of the full-length protein. C, Nuclear extracts of HeLa cells were subjected to IP using antibody against TAF1 or IgG. LNCaP cell lysate was incubated with 1 mm ATP, [35S]ubiquitin in the absence (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9) or presence of TAF1 IP (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10) in HEMG buffer. After 1 h incubation at room temperature, AR was immunoprecipitated followed by autoradiography (left) and Western blot for AR and ubiquitin (right). Lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6 are input (5%) from LNCaP lysate before IP of AR. The solid arrowhead and arrows show ubiquitin-conjugated AR. The open arrow shows nonubiquitinated AR.

Given that the E1/E2 domain of TAF1 enhances AR activity, we wanted to know whether this domain could also ubiquitinate AR in LNCaP cells under the same conditions as described above, except that the truncated E1/E2 of TAF1 was transfected instead of the full-length protein. Figure 6B shows a substantial increase in the level of ubiquitinated AR once the E1/E2 is expressed in the presence of MG132 and R1881 (lane 4 vs. 3). Together, these experiments indicate that TAF1 can ubiquitinate AR, and its E1/E2 domain is sufficient to accomplish this.

To assess whether TAF1 is able to directly ubiquitinate AR, an in vitro ubiquitination assay was performed (42). As an abundant source of endogenous TAF1, HeLa cells were subjected to pulldown with anti-TAF1 antibodies and immobilized on agarose beads. As a source for AR and E3 ligases, these proteins were extracted from LNCaP cells and incubated with radiolabeled ubiquitin, 10 nm ATP, and TAF1 or mock IP (negative control) at room temperature. After 60 min, AR was immunoprecipitated and subjected to autoradiography (Fig. 6C, left) and Western blot analysis for AR and ubiquitin (Fig. 6C, right). Lanes 1 and 2 are 5% of inputs after incubation with ATP and ubiquitin in the absence or presence of TAF1, respectively. They show a smear of 35S-ubiquitinated proteins, indicating in vitro ubiquitination has occurred. In the absence of TAF1, after AR antibody pulldown, two separate faint bands can be seen (lane 3) implying 35S-ubiquitinated AR. However, in the presence of TAF1, there is a profound increase in the amount of radiolabeled AR (lane 4, arrowhead), indicating that TAF1 plays a role in the extent of ubiquitination of AR. Lanes 5–10 show a Western blot of the same experiment. Lanes 5 and 6 are 5% of inputs before IP of AR (open arrow shows nonubiquitinated AR). Lanes 7 and 8 are IPs of AR after incubation with ATP and radiolabeled ubiquitin. The presence of multiple bands with higher molecular weight than AR protein suggests ubiquitination of AR that is enhanced in the presence of TAF1 (lanes 7 and 8). Although the amounts of polyubiquinated AR at the level of the second arrow are similar in the presence or absence of TAF1, the total amount of polyubiquitinated AR is higher in the presence of TAF1, when considering the first and third bands. To confirm these bands were ubiquitin-conjugated AR, the same membrane was blotted with ubiquitin antibody showing the same corresponding high molecular weight bands (lanes 9 and 10). Accordingly, the presence of TAF1 increases the amount of ubiquitinated AR (lane 8 vs. 7 and lane 10 vs. 9), confirming involvement of TAF1 in AR ubiquitination. Overall, these results validate our in vivo data and highlight the direct role of TAF1 in the ubiquitination of AR.

Discussion

Many possible molecular mechanisms responsible for the development of CR prostate cancer have been proposed. Most involve retention of AR expression (43). The up-regulation of AR-target genes and overexpression of AR at the protein and mRNA levels support the notion that AR activity is altered in CR states (44, 45, 46, 47). There are a variety of molecular alterations that could lead to continued or amplified AR signaling after surgical or medical castration. However, the most commonly occurring mechanisms for progression to CR are likely to be epigenetic, involving ligand-independent (or ligand-reduced) activation of AR through autocrine production of active androgens in the cancer cells, convergence of cell signaling pathways, and/or altered activity and expression of AR coregulators (43, 45, 48, 49, 50, 52). With respect to signaling pathways, several growth factors and cytokines including IGF-I, epidermal growth factor, keratinocyte growth factor, and IL-6 have been implicated, with some evidence that their activity is mediated directly or indirectly through participation of kinases such as MAPK, protein kinase A, and protein kinase C (52, 53, 55, 56). Using a shRNA interference to knock down AR, we reported that about 75% of ligand-independent AR-transcriptional activity ascribed to these factors required the direct participation of AR (6). In addition to phosphorylation, changes in other posttranslational modifications of AR such as acetylation (58) and sumoylation (59) may also play a major role in ligand-independent activation of AR and development of CR. Furthermore, the levels of androgens that persist in the prostate after castration (60) may be sufficient to activate AR under conditions of aberrant expression of specific coactivator proteins (1). Hence, an understanding of coregulator protein functions is required for a full comprehension of AR transactivation in both normal and neoplastic prostate cells.

The proteins that directly bind nuclear receptors to modulate receptor-mediated transcription are called coregulators. They differ from the general and specific transcription factors in that they do not affect the basal rate of transcription and typically do not bind to DNA (34). Using the RTA yeast two-hybrid system, TAF1 was identified as a novel AR-NTD-interacting protein (19), and this direct interaction is confirmed with full-length TAF1, using GST pulldown assays (Fig. 2C). We also find that TAF1 expression levels were increased in prostate cancer patients who underwent NHT treatment for more than 3 months (Fig. 1). Mapping of the TAF1 and AR interacting domains shows that the HAT and E1/E2 domains bind strongly to AR-NTD, mimicking the full-length TAF1. The CTK domain that was originally isolated by the RTA system interacts with all AR domains but most strongly with the AR-DBD. In contrast, NTK does not have affinity for any AR domains, further indicating the specificity of these interactions (Fig. 2, C and D). It has been reported by others that the N terminus of TAF1 binds to the concave surface of TBP and consequently inhibits TBP/TATA box contact, hence repressing transcription (28, 62). However, binding of activators, such as c-Jun with the N terminus of TAF1 releases this inhibition, resulting in transcription initiation (63). Accordingly, the ability of TAF1 to interact with AR through multiple domains other than NTK suggests that TAF1 may play a role in modulating AR folding, and one can speculate that upon interaction with AR, the NTK release from the concave surface of TBP will initiate transcription. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that upon overexpression of TAF1 in both PC3 and LNCaP cells in the presence of nuclear AR (hormone-induced activation), AR activity is increased (Fig. 4, A and B), whereas siRNA knockdown of TAF1 suppresses AR activity (Fig. 4, C and D).

Co-IP assays demonstrate that the interaction between AR and TAF1 occurs in the nuclear extracts of LNCaP and C4-2 cells in the presence of ligand-activated receptor (Fig. 3A). Although the AR seems to be more associated with TAF1 in LNCaP cells, this could be explained by the lower amount of the nuclear AR in C4-2 cells under this experimental condition (Fig. 3A, lane 4 vs. lane 2). The association of TAF1 and AR in both androgen-dependent and CR prostate cancer cells, plus the fact that TAF1 expression level is increased in patients undergoing androgen ablation therapy, suggest that TAF1 may interact with AR and enhance receptor activity even when there are low levels of circulating androgens. Because TAF1 is a component of the general transcription machinery within the TFIID complex and directly associates with AR to modulate AR activity, we explored whether TAF1 binds to the PSA promoter/enhancer. Using ChIP assays with LNCaP cells, we found that TAF1 is associated with AREs in the proximal/enhancer promoters of the PSA gene, and this association is AR dependent because knocking down AR would make the PCR products undetectable at the enhancer and significantly decrease them at the proximal promoter (Fig. 3B). This observation strongly suggests that TAF1 is a novel coactivator of AR that binds to the PSA enhancer through AR.

The essential nature of TAF1 can be attributed to its broad requirement during RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription (64). Indeed, about 18% of hamster cell line genes are TAF1 dependent (38, 65). In our studies, we also found that TAF1 can modulate the transcription of non-androgen-responsive reporters. To show the specificity of TAF1 on AR, various domains of TAF1 were tested for their inability to modulate non-androgen-responsive reporters in transient transfection assays (Fig. 5A). Although TAF1 is a component of the transcriptional machinery and is able to modulate pRLtk-Renilla, none of its individual domains influence this non-androgen-responsive promoter. However, TAF1 through its NTK and E1/E2 domains appears to be a coactivator of AR, enhancing AR transcription (Fig. 5B).

The AR is a substrate for phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination (6, 32, 41, 66, 67), and this makes AR a potential substrate for TAF1, which possesses all of the above enzymatic activities. We did not determine whether TAF1 can acetylate AR because no significant changes on AR activity are seen in transfection assays when the HAT domain is overexpressed (Fig. 5B). The NTK appears to be involved, because apigenin, a TAF1 kinase inhibitor (26, 27), can suppress AR transcriptional activity by 4.3-fold (Fig. 5C), but we are unable to show AR phosphorylation by TAF1, which suggests that TAF1 either induces phosphorylation or ubiquitination of intermediate proteins to enhance AR activity.

It has been reported that TAF1 can mono-ubiquitinate histone 1 (H1) (42) and is involved in polyubiquitination of p53 (26, 27). Because E1/E2 has the most profound effect on AR activity, we also sought to determine whether ubiquitination of AR can be increased as a consequence of TAF1 overexpression. Interestingly, in the presence of proteasome inhibitor and expression of His-ubiquitin, TAF1 enhances the total amount of ubiquitinated AR within a prostate cancer cell line (Fig. 6A, lane 8 vs. 7). In addition, the E1/E2 domain alone is able to increase the total amount of ubiquitinated AR (Fig. 6B). This supports our transactivation data (Fig. 5B), in which the E1/E2 domain enhances AR activity more than 3-fold. Furthermore, TAF1 can ubiquitinate AR even in the absence of proteasome inhibitor within the cells (Fig. 6A, lane 4) and in vitro (Fig. 6C). Because the majority of TAF1-induced polyubiquitinated AR is accumulated after the proteasome inhibition and because polyubiquitinated AR is not functional (32, 68), there are at least three possible mechanisms that could explain how TAF1 enhances AR transcriptional activity. First, TAF1 can polyubiquitinated AR through lysine 48, causing proteasome degradation of AR mainly through Mdm2 (Fig. 6, A and B). This would induce AR turnover and consequently enhance AR transcriptional activity. Although we could not detect any significant changes of the AR expression level by TAF1 using cycloheximide at different time points (data not shown), this remains to be further investigated. Second, TAF1 may induce AR polyubiquitination on other lysine sites, such as K6 or K27, as recently reported by Xu et al. (69) with the ring finger protein 6 and AR. They found that this type of AR polyubiquitination does not lead to AR degradation, as in the case of Mdm2. In contrast, it can enhance AR activity through modulation of AR binding proteins/chromatin, as has been shown with p53 and Met4 polyubiquitination (70, 71). These alternative mechanisms will be explored further in future studies. The third explanation could be that TAF1 may affect AR either through ubiquitination or phosphorylation of a cofactor, such as the possibility of Mdm2 ubiquitination by TAF1 (Fig. 6A).

In conclusion, our results suggest that TAF1 is a coactivator of AR that binds and differentially enhances AR transcriptional activity most likely through ubiquitination of AR. Accordingly, an increase in TAF1 expression during NHT therapy for advanced prostate cancer, especially with treatment extended over 6 months, could be a compensatory mechanism adapted by cancer cells to overcome lack of circulating androgens.

Materials and Methods

NHT tissue microarrays and immunohistochemistry

Archival formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human prostate tumor specimens were used to construct a human prostate cancer tissue microarray of hormone-naive, NHT-treated, and CR samples as described before (18, 36). Briefly, a total of 112 samples were obtained from radical prostatectomy, transurethral resections, or warm autopsy. Specimens were chosen so as to represent various treatment durations of androgen withdrawal therapy ranging from no treatment (n = 21), less than 3 months (n = 21), 3–6 months (n = 28), more than 6 months (n = 28), and CR tumors (n = 14). Cancer sites in donor paraffin blocks were identified by a pathologist (L.F.) using matching hematoxylin and eosin reference slides, and the tissue microarray was constructed in triplicate cores, each 0.6 mm in diameter. For staining, tissue sections mounted on the slides were deparaffinized by xylene, rehydrated through ethanol washes, and then permeabilized in a solution of 0.02% Triton X-100. Slides were then steamed in citrate buffer (pH 6), cooled for 30 min, washed in PBS, and incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min to promote antigen retrieval. After blocking in 3% BSA for 30 min, slides were then incubated overnight with anti-TAF1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA; ab17360) or IgG as a negative control at a working dilution of 1/2000 in 1% BSA. The following day, the slides were washed extensively with PBS and developed using the LSAB+ kit detection system (Dako Corp., Mississauga, Canada). Nova Red chromogen was applied, and hematoxylin counterstaining was performed (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA).

Plasmid construction

pCS2+HA-hTAF1, kindly given by Dr. R. Tjian (University of California) and Dr. Wong (University of Washington), was used as a template to subclone four TAF1 fragments (NTK52-1441, HAT1442-3102, E1/E22215-3777, and CTK4252-5730) into pcDNA3.1-V5/His expression vectors (TOPO1-TA Expression Kit; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The following primers were used to PCR amplify each domain of TAF1: the NTK domain, forward 5′-CACCATGGGACCCGGCTGCGATTTG-3′ and reverse 3′-AGTCATGCTAGAAGGAAGCC AGCC-5′; the HAT domain, forward 5′-CACCATGAATGCGATGGCTTACAATGTT-3′ and reverse 3′-AC GAAGGTCTGCATCTGTTCCTGT-5′; the E1/E2 domain, forward 5′-CACCATGGTAAAGAACTATT ATAAACGG-3′ and reverse 3′-TCGCATCTCTTCCCGATGTTGTTC-5′; and the CTK domain, forward 5′-CACCA TGGACCCTATGGTGACGCTGTCG-3′ and reverse 3′-TTCATCAGAGTCCAAGTCACTGTC-5′. The full-length human AR (pcDNA3.1-hAR) and GST-fusion constructs of AR were also generated as described before (18).

GST pulldown assay

GST fusion proteins of various AR domains (NTD1–559, DBD541–665, and LBD649–919) were expressed in the BL21 cells Escherichia coli strain, purified, and immobilized onto glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) (18, 19). Purified GST-AR domains were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining to ensure equimolar amounts of each fusion protein were used, as described before (19). Using the Quick Coupled T7 TNT in vitro transcription/translation kit (Promega Corp., Madison, WI), [35S]methionine-labeled human full-length TAF1 and the four truncated TAF1 peptides were generated and incubated with equimolar amounts of GST-AR fusion proteins that were precoupled to glutathione-agarose beads. GST alone was used as a negative control to assess nonspecific interactions of radiolabeled proteins. Binding reactions were carried out for 2 h at 4 C in GST-binding buffer [20 mm HEPES (pH 7.6), 150 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA and 0.05% Nonidet P-40]. GST-beads were then washed four times with ice-cold binding buffer, resuspended in protein sample buffer [400 mm Tris Cl (pH 8.8), 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 5% β-mercaptoethanol], and then resolved by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and analyzed by autoradiography. Dried gels were also analyzed using a phosphorimaging screen. Quantity One software was used to obtain [CNT*mm2] data for radiolabeled protein bands. All pulldowns were done in triplicate, and the average [CNT*mm2] was normalized as percent input bound.

Cell culture

LNCaP human prostate cancer cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen). The CR C4-2 cells, originally derived from LNCaP cells (51), and LNCaP cells that stably express DOX-inducible shRNA against AR (LN-shRNAAR) or scrambled shRNA (LN-shRNAsc) (57) were also grown in 5% FBS-RPMI. PC3 human prostate cancer cells (ATCC) and HeLa cervical cancer cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS. All cells were maintained at 37 C in 5% CO2.

Co-IP and Western blot

LNCaP or C4-2 cells were plated on 10-cm dishes and grown to 70% confluency. Cells were then transfected with pCS2+HA-TAF1 vector (6 μg/dish) using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 16 h incubation with transfection mix at 37 C, medium was changed to 5% CSS RPMI and incubated for another 24 h to deplete cells of bioavailable hormone. Cells were then treated with or without 1 nm R1881 for another 4 h before harvest. Using an Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA) co-IP kit, nuclear proteins were extracted and then incubated with deoxyribonuclease according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Nuclear extracts (0.1 mg, 10%) as quantified by BCA assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) was saved as inputs, and 1 mg nuclear proteins was then incubated with a mouse monoclonal anti-TAF1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; 63B) or with an equivalent amount of normal mouse IgG (negative control) overnight. Recombinant protein A/G-agarose (Santa Cruz) beads were used to immunoprecipitate antibody-protein complexes. Beads were washed four times with Active Motif washing buffer (150 mm NaCl, 1% detergent) and then resuspended in 2× SDS sample buffer. Associated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA) as described before (19). Membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline [20 mm Tris/HCl (pH 7.6), 140 mm NaCl] before incubation with the appropriately diluted primary antibody. AR and TAF1 were detected using mouse monoclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz; AR-441 and TAF1-63B, respectively). Blots were developed using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and the ECL chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Biosciences, Arlington Heights, IL).

ChIP assay

LN-shRNAAR or LN-shRNAsc cells were grown in 5% CSS RPMI for 24 h and then treated with 1 μg/ml DOX for another 48 h followed or not by 1 nm R1881 for 4 h. Cells were subsequently cross-linked with paraformaldehyde and sonicated to achieve a DNA smear of 200-1000 bp. ChIP assay was performed using EZ ChIP kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) on the β-actin and PSA genes, as previously described (54). For PCR, 2 μl of 50 μl DNA extraction was used in 25 cycles of amplification. The primer sequences were as follows: the proximal promoter of the PSA forward 5′-TCTGCCTTTGTCCCCTAGAT-3′ and reverse 3′-AACCTTCATTCCCCAGGACT-5′, the enhancer promoter of PSA forward 5′-CCTCCCAGGTTCAAGTGATT-3′ and reverse 3′-GCCTGTAATCCCAGCACTTT-5′, the nonpromoter region of PSA forward 5′-CTGTGCTTGGAGTTTACCTGA-3′ and reverse 3′-GCAGAGGTTGCAGTGAGCC-5′, and β-actin primers forward 5′-TC CTCCTCTTCCTCAATCTCG-3′ and reverse 3′-AAGGCAACTTTCGGAACGG-5′. AR-C-19 and TAF1-63B antibodies (Santa Cruz) were used for ChIP.

Transcriptional assays

Cells were seeded in six-well plates and, for PC3 cells, grown to 90% confluency. Using Lipofectin reagent (Invitrogen). Cells were cotransfected with increasing amounts of pHA-hTAF1, 1.5 μg/well full-length AR (pAR6), 0.2 μg/well pARR3-tk-Luc, and 0.1 μg/well pRLtk-Renilla. For LNCaP cells, cells were cotransfected at 70% confluency with 1 μg/well pPSA-Luc (−6100/+12; gift from Dr. J. Trapman, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands) and 1 μg/well pHA-TAF1 in addition to pRLtk-Renilla as mentioned above. The total amount of DNA was adjusted to 3 μg/well using vector (pCS2+). Cells were incubated with the transfection mix for 16 h at 37 C and subsequently replenished with 5% CSS RPMI containing 1 nm R1881 or vehicle alone. Transfected cells were cultured for an additional 24 h before harvesting for luciferase and Western blot analysis. For siRNA-mediated TAF1 reduction, two 21-nucleotide siRNA duplexes with 3′-dTdT overhangs corresponding to TAF1 mRNA (5′-AAGACCCAAACAACCCCGCAT-3′ and 5′-AACTACGACTACGCTCCACCA-3′) (26) were synthesized and purchased from Applied Biosystems (Ambion, Austin, TX) together with control siRNA. At 40% confluency, PC3 or LNCaP cells were cotransfected with 5 and/or 10 nm siRNA duplexes, pRLtk-Renilla and pARR3tk-Luc or pPSA-Luc as described above, except cells were allowed to grow for 48 h in 5% CSS medium with or without 1 nm R1881. Luciferase activity was normalized to protein concentration as quantified by BCA protein assay. Each assay was done in triplicate, and experiments were repeated at least three times.

Purification of His-tagged ubiquitin conjugates

LNCaP cells, grown in 5% CSS RMPI for 24 h, were cotransfected with 2 μg plasmid expressing His-tagged ubiquitin (pHis6-ubiquitin; ATCC) and 6 μg pHA-TAF1, pV5-E1/E2, or empty vector using Lipofectin reagent. After 16 h, the medium was changed to 5% CSS RPMI with or without 1 nm R1881 for 24 h followed by 6 h treatment with 10 μm MG132 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) or vehicle. Cells were then scraped and lysed in 1 ml RIPA buffer [150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mm Tris/HCl (pH 8)]. Five percent of the cell lysate was used as input, and the remainder was mixed with 50 μl Ni2+-NTA-agarose beads (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) as described before (58). The mixture was allowed to rotate at 4 C for 3 h, and a magnet holder was used to pull down His6-ubiquitinated conjugates. Beads were then washed four times with RIPA buffer and resuspended in 2× SDS sample buffer. Associated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and blotted for antibodies against AR (Santa Cruz; AR-441), Mdm2 (Santa Cruz), hemagglutinin (Covance, Quebec, Canada), V5 (Invitrogen), and β-actin (Sigma).

Ubiquitination assay

Nuclear proteins of HeLa cells were extracted as described elsewhere (61). Briefly, HeLa cells were harvested into cold PBS, and approximately 107 cells were pelleted and resuspended in 500 μl cold hypotonic buffer [10 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.9) at 4 C, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride]. The cells were incubated on ice for 10 min, and then vortexed for 10 sec. The sample was centrifuged, the supernatant discarded, and the pellet resuspended in 100 μl hypertonic buffer [20 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.9), 25% glycerol, 420 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride] and incubated on ice for 20 min for high-salt extraction. The supernatant fraction, which contains nuclear proteins, was subjected to IP using antibody against TAF1 or IgG, and a modified in-solution ubiquitination assay was performed (42). Briefly, 1 mg protein of the whole-cell lysate from LNCaP cells was incubated in HEMG buffer [final concentration: 25 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 8.0), 12.5 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm EDTA, 400 mm KCl, 10% glycerol] containing 1 mm ATP and 5 μl [35S]ubiquitin in the presence of immunoprecipitated TAF1 or control mouse IgG. After rotating for 1 h at room temperature, AR was immunoprecipitated and subjected to autoradiography or Western blot analysis with antibodies against AR (Santa Cruz; N-20) and ubiquitin (Santa Cruz; Ubi-1).

Statistical analysis

Student’s t test (two sided) was used for statistical analysis of transactivation assays and GST pulldown assays. Wilcoxon rank test was used for tissue microarray analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Bell for his assistance with statistical analysis of the NHT-tissue microarray data and Dr. M. Cox for critical discussion of this work.

NURSA Molecule Pages:

Ligands: R1881;

Nuclear Receptors: AR.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute Contract Grant 17421 and by a trainee award grant from the U.S. Department of Defense Contract Grant W81XWH-07-1-0131 (PC060161).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online February 24, 2010

Abbreviations: AR, Androgen receptor; ARE, androgen response element; BCA, bicinchoninic acid; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CNT*mm2, counts/mm2; CR, castration-resistant; CSS, charcoal stripped serum; CTK, C-terminal kinase; DBD, DNA-binding domain; DOX, doxycycline; E1/E2, ubiquitin-activating/conjugating domain; FBS, fetal bovine serum; GST, glutathione S-transferase; HAT, histone acetylation; IP, immunoprecipitation; LBD, ligand-binding domain; NHT, neo-adjuvant hormone therapy; NTD, N-terminal domain; NTK, N-terminal kinase; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; RTA, Tup1 repressed transactivator; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA; TAF1, TBP-associated factor 1; TBP, TATA-binding protein; TFIID, transcription factor IIF.

References

- 1.Heinlein CA, Chang C2004. Androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Endocr Rev 25:276–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Litvinov IV, De Marzo AM, Isaacs JT2003. Is the Achilles’ heel for prostate cancer therapy a gain of function in androgen receptor signaling? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:2972–2982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW1994. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem 63:451–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinlein CA, Chang C2002. Androgen receptor (AR) coregulators: an overview. Endocr Rev 23:175–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horwitz KB, Jackson TA, Bain DL, Richer JK, Takimoto GS, Tung L1996. Nuclear receptor coactivators and corepressors. Mol Endocrinol 10:1167–1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu M, Wang C, Reutens AT, Wang J, Angeletti RH, Siconolfi-Baez L, Ogryzko V, Avantaggiati ML, Pestell RG2000. p300 and p300/cAMP-response element-binding protein-associated factor acetylate the androgen receptor at sites governing hormone-dependent transactivation. J Biol Chem 275:20853–20860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gnanapragasam VJ, Leung HY, Pulimood AS, Neal DE, Robson CN2001. Expression of RAC 3, a steroid hormone receptor co-activator in prostate cancer. Br J Cancer 85:1928–1936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Yeh S, Wu G, Hsu CL, Wang L, Chiang T, Yang Y, Guo Y, Chang C2001. Identification and characterization of a novel androgen receptor coregulator ARA267-α in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem 276:40417–40423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choudhry MA, Ball A, McEwan IJ2006. The role of the general transcription factor IIF in androgen receptor-dependent transcription. Mol Endocrinol 20:2052–2061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavery DN, McEwan IJ2008. Functional characterization of the native NH2-terminal transactivation domain of the human androgen receptor: binding kinetics for interactions with TFIIF and SRC-1a. Biochemistry 47:3352–3359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans RM1988. The steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science 240:889–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy AK, Chatterjee B1995. Androgen action. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 5:157–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agoulnik IU, Weigel NL2006. Androgen receptor action in hormone-dependent and recurrent prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem 99:362–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang CS, Kokontis J, Liao ST1988. Structural analysis of complementary DNA and amino acid sequences of human and rat androgen receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:7211–7215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lubahn DB, Joseph DR, Sullivan PM, Willard HF, French FS, Wilson EM1988. Cloning of human androgen receptor complementary DNA and localization to the X chromosome. Science 240:327–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trapman J, Klaassen P, Kuiper GG, van der Korput JA, Faber PW, van Rooij HC, Geurts van Kessel A, Voorhorst MM, Mulder E, Brinkmann AO1988. Cloning, structure and expression of a cDNA encoding the human androgen receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 153:241–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirst M, Ho C, Sabourin L, Rudnicki M, Penn L, Sadowski I2001. A two-hybrid system for transactivator bait proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:8726–8731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray MR, Wafa LA, Cheng H, Snoek R, Fazli L, Gleave M, Rennie PS2006. Cyclin G-associated kinase: a novel androgen receptor-interacting transcriptional coactivator that is overexpressed in hormone refractory prostate cancer. Int J Cancer 118:1108–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wafa LA, Cheng H, Rao MA, Nelson CC, Cox M, Hirst M, Sadowski I, Rennie PS2003. Isolation and identification of l-dopa decarboxylase as a protein that binds to and enhances transcriptional activity of the androgen receptor using the repressed transactivator yeast two-hybrid system. Biochem J 375:373–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albright SR, Tjian R2000. TAFs revisited: more data reveal new twists and confirm old ideas. Gene 242:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martel LS, Brown HJ, Berk AJ2002. Evidence that TAF-TATA box-binding protein interactions are required for activated transcription in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol 22:2788–2798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verrijzer CP, Tjian R1996. TAFs mediate transcriptional activation and promoter selectivity. Trends Biochem Sci 21:338–342 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dikstein R, Ruppert S, Tjian R1996. TAFII250 is a bipartite protein kinase that phosphorylates the base transcription factor RAP74. Cell 84:781–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizzen CA, Yang XJ, Kokubo T, Brownell JE, Bannister AJ, Owen-Hughes T, Workman J, Wang L, Berger SL, Kouzarides T, Nakatani Y, Allis CD1996. The TAFII250 subunit of TFIID has histone acetyltransferase activity. Cell 87:1261–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pham AD, Sauer F2000. Ubiquitin-activating/conjugating activity of TAFII250, a mediator of activation of gene expression in Drosophila Science 289:2357–2360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li HH, Li AG, Sheppard HM, Liu X2004. Phosphorylation on Thr-55 by TAF1 mediates degradation of p53: a role for TAF1 in cell G1 progression. Mol Cell 13:867–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allende-Vega N, McKenzie L, Meek D2008. Transcription factor TAFII250 phosphorylates the acidic domain of Mdm2 through recruitment of protein kinase CK2. Mol Cell Biochem 316:99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lively TN, Ferguson HA, Galasinski SK, Seto AG, Goodrich JA2001. c-Jun binds the N terminus of human TAFII250 to derepress RNA polymerase II transcription in vitro. J Biol Chem 276:25582–25588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Léveillard T, Wasylyk B1997. The MDM2 C-terminal region binds to TAFII250 and is required for MDM2 regulation of the cyclin A promoter. J Biol Chem 272:30651–30661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siegert JL, Rushton JJ, Sellers WR, Kaelin Jr WG, Robbins PD2000. Cyclin D1 suppresses retinoblastoma protein-mediated inhibition of TAFII250 kinase activity. Oncogene 19:5703–5711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cai C, Hsieh CL, Shemshedini L2007. c-Jun has multiple enhancing activities in the novel cross talk between the androgen receptor and Ets variant gene 1 in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Res 5:725–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaughan L, Logan IR, Neal DE, Robson CN2005. Regulation of androgen receptor and histone deacetylase 1 by Mdm2-mediated ubiquitylation. Nucleic Acids Res 33:13–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Narayanan BA, Narayanan NK, Davis L, Nargi D2006. RNA interference-mediated cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition prevents prostate cancer cell growth and induces differentiation: modulation of neuronal protein synaptophysin, cyclin D1, and androgen receptor. Mol Cancer Ther 5:1117–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heemers HV, Tindall DJ2007. Androgen receptor (AR) coregulators: a diversity of functions converging on and regulating the AR transcriptional complex. Endocr Rev 28:778–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wafa L2007. Identification and characterization of proteins that interact with the androgen receptor to modulate its activity. In: Pathology and laboratory medicine. Vancouver: University of British Columbia; 185–210

- 36.Wafa LA, Palmer J, Fazli L, Hurtado-Coll A, Bell RH, Nelson CC, Gleave ME, Cox ME, Rennie PS2007. Comprehensive expression analysis of l-dopa decarboxylase and established neuroendocrine markers in neoadjuvant hormone-treated versus varying Gleason grade prostate tumors. Hum Pathol 38:161–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang PJ, Page DC2002. Functional substitution for TAFII250 by a retroposed homolog that is expressed in human spermatogenesis. Hum Mol Genet 11:2341–2346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Brien T, Tjian R2000. Different functional domains of TAFII250 modulate expression of distinct subsets of mammalian genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:2456–2461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Read JT, Rahmani M, Boroomand S, Allahverdian S, McManus BM, Rennie PS2007. Androgen receptor regulation of the versican gene through an androgen response element in the proximal promoter. J Biol Chem 282:31954–31963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miranda M, Sorkin A2007. Regulation of receptors and transporters by ubiquitination: new insights into surprisingly similar mechanisms. Mol Interv 7:157–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burgdorf S, Leister P, Scheidtmann KH2004. TSG101 interacts with apoptosis-antagonizing transcription factor and enhances androgen receptor-mediated transcription by promoting its monoubiquitination. J Biol Chem 279:17524–17534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belz T, Pham AD, Beisel C, Anders N, Bogin J, Kwozynski S, Sauer F2002. In vitro assays to study protein ubiquitination in transcription. Methods 26:233–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taplin ME, Balk SP2004. Androgen receptor: a key molecule in the progression of prostate cancer to hormone independence. J Cell Biochem 91:483–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, Baek SH, Chen R, Vessella R, Rosenfeld MG, Sawyers CL2004. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med 10:33–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rennie PS, Nelson CC1998. Epigenetic mechanisms for progression of prostate cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 17:401–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sirotnak FM, She Y, Khokhar NZ, Hayes P, Gerald W, Scher HI2004. Microarray analysis of prostate cancer progression to reduced androgen dependence: studies in unique models contrasts early and late molecular events. Mol Carcinog 41:150–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tilley WD, Lim-Tio SS, Horsfall DJ, Aspinall JO, Marshall VR, Skinner JM1994. Detection of discrete androgen receptor epitopes in prostate cancer by immunostaining: measurement by color video image analysis. Cancer Res 54:4096–4102 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Locke JA, Guns ES, Lubik AA, Adomat HH, Hendy SC, Wood CA, Ettinger SL, Gleave ME, Nelson CC2008. Androgen levels increase by intratumoral de novo steroidogenesis during progression of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res 68:6407–6415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohler JL2008. A role for the androgen-receptor in clinically localized and advanced prostate cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 22:357–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sadar MD, Hussain M, Bruchovsky N1999. Prostate cancer: molecular biology of early progression to androgen independence. Endocr Relat Cancer 6:487–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thalmann GN, Anezinis PE, Chang SM, Zhau HE, Kim EE, Hopwood VL, Pathak S, von Eschenbach AC, Chung LW1994. Androgen-independent cancer progression and bone metastasis in the LNCaP model of human prostate cancer. Cancer Res 54:2577–2581 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ueda T, Mawji NR, Bruchovsky N, Sadar MD2002. Ligand-independent activation of the androgen receptor by interleukin-6 and the role of steroid receptor coactivator-1 in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem 277:38087–38094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Culig Z, Hobisch A, Cronauer MV, Radmayr C, Trapman J, Hittmair A, Bartsch G, Klocker H1994. Androgen receptor activation in prostatic tumor cell lines by insulin-like growth factor-I, keratinocyte growth factor, and epidermal growth factor. Cancer Res 54:5474–5478 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shang Y, Myers M, Brown M2002. Formation of the androgen receptor transcription complex. Mol Cell 9:601–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nazareth LV, Weigel NL1996. Activation of the human androgen receptor through a protein kinase A signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 271:19900–19907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sadar MD1999. Androgen-independent induction of prostate- specific antigen gene expression via cross-talk between the androgen receptor and protein kinase A signal transduction pathways. J Biol Chem 274:7777–7783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng H, Snoek R, Ghaidi F, Cox ME, Rennie PS2006. Short hairpin RNA knockdown of the androgen receptor attenuates ligand-independent activation and delays tumor progression. Cancer Res 66:10613–10620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rodriguez MS, Desterro JM, Lain S, Midgley CA, Lane DP, Hay RT1999. SUMO-1 modification activates the transcriptional response of p53. EMBO J 18:6455–6461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poukka H, Karvonen U, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ2000. Covalent modification of the androgen receptor by small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 (SUMO-1). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:14145–14150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mohler JL, Gregory CW, Ford 3rd OH, Kim D, Weaver CM, Petrusz P, Wilson EM, French FS2004. The androgen axis in recurrent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 10:440–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andrews NC, Faller DV1991. A rapid micropreparation technique for extraction of DNA-binding proteins from limiting numbers of mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 19:2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kokubo T, Swanson MJ, Nishikawa JI, Hinnebusch AG, Nakatani Y1998. The yeast TAF145 inhibitory domain and TFIIA competitively bind to TATA-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol 18:1003–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lively TN, Nguyen TN, Galasinski SK, Goodrich JA2004. The basic leucine zipper domain of c-Jun functions in transcriptional activation through interaction with the N terminus of human TATA-binding protein-associated factor-1 (human TAFII250). J Biol Chem 279:26257–26265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wassarman DA, Sauer F2001. TAFII250: a transcription toolbox. J Cell Sci 114:2895–2902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Irvin JD, Pugh BF2006. Genome-wide transcriptional dependence on TAF1 functional domains. J Biol Chem 281:6404–6412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou ZX, Kemppainen JA, Wilson EM1995. Identification of three proline-directed phosphorylation sites in the human androgen receptor. Mol Endocrinol 9:605–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu Z, Becklin RR, Desiderio DM, Dalton JT2001. Identification of a novel phosphorylation site in human androgen receptor by mass spectrometry. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 284:836–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin HK, Altuwaijri S, Lin WJ, Kan PY, Collins LL, Chang C2002. Proteasome activity is required for androgen receptor transcriptional activity via regulation of androgen receptor nuclear translocation and interaction with coregulators in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem 277:36570–36576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu K, Shimelis H, Linn DE, Jiang R, Yang X, Sun F, Guo Z, Chen H, Li W, Chen H, Kong X, Melamed J, Fang S, Xiao Z, Veenstra TD, Qiu Y2009. Regulation of androgen receptor transcriptional activity and specificity by RNF6-induced ubiquitination. Cancer Cell 15:270–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kaiser P, Flick K, Wittenberg C, Reed SI2000. Regulation of transcription by ubiquitination without proteolysis: Cdc34/SCF(Met30)-mediated inactivation of the transcription factor Met4. Cell 102:303–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Le Cam L, Linares LK, Paul C, Julien E, Lacroix M, Hatchi E, Triboulet R, Bossis G, Shmueli A, Rodriguez MS, Coux O, Sardet C2006. E4F1 is an atypical ubiquitin ligase that modulates p53 effector functions independently of degradation. Cell 127:775–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]