Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM) is a highly aggressive and lethal form of primary brain cancer. Numerous barriers exist to the effective treatment of GBM including the tightly controlled interface between the blood stream and central nervous system termed the ‘neurovascular unit’, a narrow and tortuous tumor extracellular space containing a dense meshwork of proteins and glycosaminoglycans, and genomic heterogeneity and instability. A major goal of GBM therapy is achieving sustained drug delivery to glioma cells while minimizing toxicity to adjacent neurons and glia. Targeted nanotherapeutics have emerged as promising drug delivery systems with the potential to improve pharmacokinetic profiles and therapeutic efficacy. Some of the key cell surface molecules that have been identified as GBM targets include the transferrin receptor, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein, αvβ3 integrin, glucose transporter(s), glial fibrillary acidic protein, connexin 43, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), EGFR variant III, interleukin-13 receptor α chain variant 2, and fibroblast growth factor-inducible factor 14. However, most targeted therapeutic formulations have yet to demonstrate improved efficacy related to disease progression or survival. Potential limitations to current targeted nanotherapeutics include: (i) adhesive interactions with non-target structures, (ii) low density or prevalence of the target, (iii) lack of target specificity, and (iv) genetic instability resulting in alterations of either the target itself or its expression level in response to treatment. In this review, we address these potential limitations in the context of the key GBM targets with the goal of advancing the understanding and development of targeted nanotherapeutics for GBM.

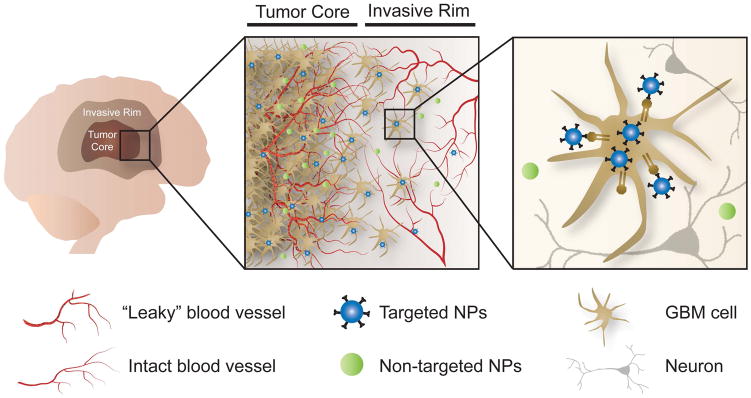

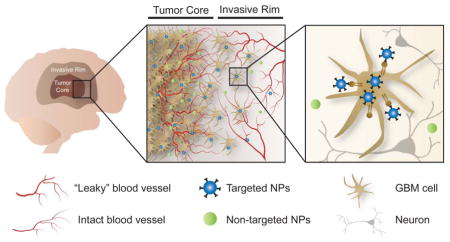

Graphical Abstract

In an effort to overcome barriers to treatment of GBM, targeted nanotherapeutics have emerged as promising drug delivery systems with the potential to improve pharmacokinetic profiles and therapeutic efficacy.

1. Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common form of primary adult brain cancer, taking more than 15,000 lives in the USA each year [1]. GBM represents the highest grade of glioma (grade IV) in the World Health Organization classification scheme and is a highly invasive solid tumor. GBM cell infiltration into the surrounding brain parenchyma renders a complete surgical resection unfeasible without producing significant neurological injury [2]. Residual glioma cells at the tumor margins therefore frequently result in tumor recurrence and are an important target for novel therapies [3–4].

The current standard of care for patients with GBM has slowly evolved over the course of several decades. In the early 1960s, systemic corticosteroids were shown to have a dramatic impact on patients’ quality of life by reducing peri-tumoral edema, thereby ameliorating neurological symptoms stemming from mass effect [5]. Shortly thereafter, whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) became recognized as an effective adjuvant therapy. Although WBRT enabled average patient survival to double from 6 to 12 months [6], the dose was limited by potential toxicity to central nervous system (CNS) cells. As a result, standard radiotherapy regimens now involve intensity modulated radiation therapy delivered in fractionated doses (2 Gy daily) for a total dose of 60 Gy [7–8].

An interstitial, local drug delivery strategy was developed in the 1970s using non-inflammatory, biodegradable polymers that can incorporate biochemically active macromolecules [9]. The FDA approved interstitial wafers comprised of poly [1,3-bis-(p-carboxyphenoxy propane)-co-(sebacic anhydride)] loaded with 3.8% carmustine for the treatment of recurrent high grade glioma in 1996 and primary high grade glioma in 2004 [10–14]. The carmustine interstitial wafers (CIW) are implanted along the borders of the resection cavity following surgery, increasing the delivery of the alkylating agent to the residual tumor cells. CIW is associated with an ~2 month increase in median survival (13.9 months vs. 11.6 months) and a 29% reduction in the risk of death over the course of 30 months [13].

In an effort to complement the beneficial effects of corticosteroids and radiation therapy, systemic chemotherapeutic agents were also studied during the 1990s. DNA alkylating agents, in particular carmustine, improved median survival by ~2 months and became widely utilized in the treatment of GBM despite significant systemic side effects including myelosuppression and pulmonary toxicity [15]. In the 2000s, however, focus shifted to temozolomide (TMZ), which can be delivered in oral rather than intravenous form. In 2005, Stupp et al. [16] established the superiority of surgery and combined chemoradiation therapy with TMZ over surgery and radiation alone. This approach became the new standard of care for patients with GBM.

Despite these advances, GBM is still associated with a median survival of less than 15 months [2, 16]. Recently, investigators have conducted genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses of GBM specimens in order to identify actionable therapeutic targets [17]. These studies have identified several constitutively activated receptor tyrosine kinases and intracellular signaling nodes that likely drive major aspects of GBM pathobiology [17–18]. Nevertheless, in the case of both chemotherapeutic agents and molecularly-targeted drugs, a series of significant physical and biological barriers limit the effective treatment of GBM.

2. Barriers to GBM Treatment

The anatomy and physiology of the CNS present several barriers to therapeutic drug delivery to the brain [2]. Therapeutic agents must cross the BBB, avoid clearance via the glial-lymphatic system (GLS) [19], and move through the electrostatically charged and anisotropic extracellular space (ECS) found between brain cells [20]. Intra-tumoral heterogeneity, cancer stem cells (CSCs), and genetic instability are additional obstacles to the successful treatment of GBM. The development and utilization of targeted nanotherapeutics may be a promising strategy for overcoming these barriers to GBM treatment.

2.1 Neurovascular Unit – Blood Brain Barrier

The BBB is a physio-anatomic interface that protects and separates the CNS from the external environment and other body components. The BBB is formed primarily by the specialized tight junctions that join cerebral endothelial cells, in addition to a thick basement membrane and astrocytic end-processes [21]. These components form the neurovascular unit, the integrity of which is tightly regulated by interactions with adjacent pericytes [22–23]. The BBB controls the trafficking of most molecules, including therapeutic agents, to and from the brain. With the exception of small (< 400 Da) and relatively lipophilic molecules, the BBB limits entry to ~98% of all drugs [24]. Therefore, systemically administered chemotherapies reach the brain in low concentrations, resulting in reduced efficacy and potentially significant systemic side effects.

Importantly, the microvascular proliferation associated with GBM results in abnormal, “leaky” blood vessels, producing disruption of the BBB at the tumor core and allowing the intra-tumoral accumulation of systemically delivered molecules (see Section 3.1) [25–29]. Despite evidence that particles as large as 100 nm in diameter can accumulate in regions with a disrupted BBB [30], several groups have suggested that this capability is restricted to smaller particles (< 20 nm in diameter) [31–32]. Moreover, although the BBB is altered in the tumor core, it remains largely intact in regions where tumor cells have infiltrated healthy brain parenchyma, thereby hindering drug delivery to the cells that are largely responsible for tumor recurrence after initial surgical resection [33].

Several strategies have been explored for delivering therapeutic agents across the BBB (for a comprehensive review, see [34]), including: (i) disrupting the BBB via osmotic agents, chemical agents, and mechanical methods [32, 34–35], (ii) enhancing transcellular transport, and (iii) hijacking receptors and/or transporters that are involved in the endogenous receptor-mediated transcytosis (RMT) pathway [2, 36–42]. As an alternative to crossing the BBB, local delivery strategies have been explored in order to bypass the BBB entirely and deliver therapeutic agents directly to the site of interest in the brain parenchyma [9]. Examples of these local delivery strategies include CIW (See Section 1) and convection-enhanced delivery (CED). In CED, the therapeutic agent is delivered via a continuous infusion under pressure [43]. This approach results in bulk flow of the infusate, producing larger volumes of distribution than diffusion alone. Nevertheless, CED faces several challenges, including suboptimal catheter placement, backflow along the catheter, leakage into the subarachnoid space and/or ventricles, and limited drug distribution due to the physical constraints – primarily the mesh spacing, tortuosity, and electrostatic interactions – of the brain ECS (See Section 2.2) [44]. Consequently, novel delivery techniques must be partnered with innovative engineering strategies in order to maximize the movement of nanotherapeutic agents within brain tissue.

2.2 The Glial-Lymphatic System and the Brain Extracellular Space

Dispersion within brain tissue results from a balance between the rate of clearance from the brain and the rate of movement and partitioning in cells and spaces through the parenchyma. A variety of clearance mechanisms exist. Along with active transport by efflux transporters [45] and enzymatic breakdown, a paravascular GLS drainage system has been recently identified whereby interstitial solutes, waste products, and therapeutic agents (including nanoparticles) are cleared from the brain parenchyma [19]. Particulate drug formulation is an established approach to encapsulate and shield drugs from clearance, degradation, or undesired partitioning within tissues, and thus may allow an effective drug concentration to be maintained in the brain for a prolonged time [2, 10, 34]. This therapeutic mechanism is further aided by targeting drugs directly to tumor cells, such that off-target toxicities are minimized and relatively high drug concentrations are maintained in the malignant cells.

Therapeutic agents that escape these various clearance mechanisms move through the parenchyma within the spaces that exist between cellular structures, termed the “extracellular” or “interstitial” space [46]. Approximately 10–20% of the total brain volume consists of the ECS, which contains an anisotropic, complex network of ionically charged extracellular matrix (ECM) components within extracellular fluid [47]. The efficient movement of therapeutic agents through the ECS is hindered by the narrow width of these spaces, high degree of tortuosity, and electrostatic interactions with charged regions of the ECS. These characteristics of the brain ECS are a critical obstacle in the ability of therapeutic agents to disperse effectively within the brain and reach invasive GBM cells [2, 48]. Recently, nanoparticle surface modifications have been proposed as a means of overcoming the limitations posed by the brain ECS. In particular, coating the surface of targeted nanoparticles with hydrophilic polymers allows the particles to diffuse through the ECS more rapidly than non-coated nanoparticles [49–50]. This results in improved dispersion within the brain parenchyma and may contribute to the therapeutic efficacy of surface coated targeted nanoparticles.

2.3 Intratumoral Molecular Heterogeneity and Cancer Stem Cells

GBM is not a single, uniform disease, but rather is characterized by genetic heterogeneity and instability, and cellular pleomorphism [51]. In a landmark study, Verhaak et al. [52] identified four transcriptional profiles, each representing a unique GBM subtype with distinct features: classical (epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-driven), proneural (platelet derived growth factor (PDGF)-driven), mesenchymal (neurofibromatous type I (NF1)-driven), and neural. Genomic profiling has revealed that not only are different tumors driven by distinct signaling networks, but that even within a single tumor, geographic heterogeneity and genetic diversity are the rule rather than the exception [53–54]. For example, cells that constitute the tumor core demonstrate different molecular and genetic profiles than the invasive cells that have migrated to distant regions [55–56]. Genetic diversity and instability allows the tumor to respond to selective pressures in the form of therapeutic agents by facilitating the emergence of resistant clones that proliferate and serve as a source of tumor recurrence [54, 57–58].

GBM CSCs, a particular subset of GBM cells with stem cell-like properties, are thought to play a major role in therapeutic resistance [59–60]. These CSCs display unique properties, including a propensity for long term self-renewal [57]. CSCs demonstrate greater resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy than non-CSCs, due in part to the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins, efflux transporters, and enhanced DNA repair molecules [61]. Therapies that are ineffective against stem cells therefore allow the tumor to re-form via the proliferation and differentiation of CSCs. Consequently, combination treatments that simultaneously target multiple transcriptional networks and various cell populations including CSCs are necessary to effectively prevent resistant clonal populations from re-establishing the tumor [59]. Such combination treatments may include targeted nanoparticles, which have the potential to deliver multiple therapeutic agents in a sustained fashion and over a more protracted time course. The ability to achieve higher, albeit safe, doses of drugs for prolonged periods may contribute to the destruction of CSCs that otherwise survive systemic chemotherapy.

3. Tumor-Targeted Nanotherapeutics

In an effort to overcome these barriers to treatment of GBM, nanomedicine has emerged as a promising approach. A variety of nanocarriers, including liposomes, polymers, inorganic materials, and viruses have been studied as a means of delivering a wide range of therapeutic payloads [62]. Relative to conventional drug delivery systems, nanocarriers offer significant advantages, including increased drug solubility, extended circulation half-life and stability, and the ability to selectively target the tumor, thereby reducing side effects while delivering more potent treatments [63]. Tumor-targeted nanotherapy may be accomplished by either passive and/or active targeting (Figure 1). A detailed description of the nanoparticle types used for GBM therapy [48, 64–66], physical modalities such as ultrasound to achieve brain delivery and penetration [67–70], and alternate routes of administration including intranasal route [2, 66, 71–72] can be found in several other excellent reviews.

Figure 1.

Passive versus active tumor targeting. In an effort to overcome barriers to treatment of GBM, nanotherapeutics designed for either passive or active tumor targeting have emerged as a promising approach. Although the BBB is altered in the tumor core, it remains largely intact in regions where tumor cells have infiltrated healthy brain parenchyma, thereby hindering systemic therapeutic delivery to the invasive GBM cells that are largely responsible for tumor recurrence after initial surgical resection. Actively targeted nanotherapeutics - designed to kill those GBM cells left behind after surgical resection, but not healthy human brain cells - have the potential to improve pharmacokinetic profiles and therapeutic efficacy.

3.1 Passive Targeting

Systemically delivered nanotherapeutics achieve passive tumor targeting through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. The tumor vasculature is highly permeable due to extensive endothelial cell proliferation, a deficiency of pericytes, and abnormalities in the basement membrane of the vessel [73]. Intravenously administered nanoparticles extravasate through these leaky gaps into the tumor tissue, where they accumulate in the tumor bed due to dysfunctional lymphatic drainage [74]. Extravasation and retention depends primarily on the physical properties of the nanoparticles, including size, shape, surface charge and hydrophobicity. Nanoparticles < 400 nm in size routinely extravasate and accumulate in the interstitial space [75–76]. However, the nanoparticle size requirement for EPR-mediated delivery to intracranial tumors has not been evaluated in detail. In one study, Householder et al. [77] observed that systemically administered ~200 nm camptothecin-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles accumulated in GL261 tumors in C57BL/6 albino mice at 10-fold higher levels compared to healthy brain. These nanoparticles were effective in slowing the growth of intracranial GL261 tumors, providing a significant survival benefit compared to mice receiving saline or free camptothecin. In another study by Kafa et al. [78], functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes with a needle-like shape and flexible structure were shown to passively accumulate in the brain following systemic administration. Further, Ambruosi et al. [79] investigated the biodistribution of doxorubicin (Dox)-loaded poly(butyl-2-cyano[3-(14)C]acrylate) (PBCA) nanoparticles (270 ± 30 nm in diameter) and Dox-loaded polysorbate 80-coated PBCA nanoparticles in glioblastoma 101/8 cell-bearing rats after intravenous injection. The nanoparticles accumulated in the tumor site and in the contralateral hemisphere.. The accumulation in tumor was 2-fold more in the case of polysorbate 80-coated nanoparticles compared to non-coated nanoparticles. Nevertheless, blood vessel permeability is rarely homogenous throughout the tumor, resulting in poor control over the diffusion of a nanotherapeutic agent through these fenestrations and spread into the tumor mass. Moreover, the EPR effect may be diminished in brain tumors due to the impedance of diffusion by the brain ECS and by elevated interstitial pressure Therefore, although nanoparticles can passively accumulate within tumors, alternative strategies such as active targeting may be required for significant improvements in drug delivery to GBM tumor cells.

3.2 Active Targeting

Active nanotherapeutic targeting involves the recognition of cell surface receptors preferentially expressed on GBM tumor cells relative to non-neoplastic brain cells. Identifying an overexpressed target, selecting a highly specific targeting moiety, and designing a suitable delivery system all impact the efficacy of targeted nanomedicine [73]. Nanoparticle surfaces can be decorated via chemical conjugation to a wide variety of targeting ligands such as monoclonal antibodies, peptides, aptamers, growth factors, and hormones [80]. Target-specific ligands increase the nanoparticle affinity for the antigens or receptors that are over-expressed on the target cells [75, 81]. Upon binding the target, nanoparticles can be internalized via receptor-mediated endocytosis thereby promoting cellular uptake and increasing the therapeutic efficacy of the payload. Additionally, active targeting can be employed to treat metastatic cells that have traveled away from the primary tumor site, as these cells may also be expressing the receptors of interest [75, 82]. Over the years, several targets have been identified that are overexpressed on GBM tumor cells and studied for the active targeting of therapeutic nanoparticles (see Table 1). Some examples of these targets are discussed in the following sections.

Table 1.

| Target | Targeting Moiety | Nanocarrier | Payload | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transferrin receptor | Transferrin | PEG-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) polymersome | Doxorubicin | Pang et al. 2011 |

| Transferrin | PEG-G4 poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimer | Doxorubicin | Li et al. 2012 | |

| Transferrin | Self-assembling PEGylated nanoparticlea | Zoledronic Acid | Porru et al. 2014 | |

| Anti-transferrin receptor single chain antibody fragment (TfRscFV) | scL (immunoliposome nanocomplex) | wtp53 plasmid | Kim et al. 2014, Kim et al. 2015 | |

| Transferrin | Polysorbate 80 coated PLGA nanoparticle | Methotrexate | Jain et al. 2015 | |

| TfRscFV | scL (immunoliposome nanocomplex) | Temozolomide | Kim et al. 2015 | |

| Lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) | Lactoferrin | PEG-PCL | Doxorubicin | Pang et al. 2010 |

| αvβ3 integrin | Cyclic arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) peptide | Poly(trimethylene carbonate)-based micellar nanoparticulate system | Paclitaxel | Jiang et al. 2011, Jiang et al. 2013 |

| GFAP | GFAP mAb | PEGylated liposome | N/Ab | Chekhonin et al. 2012 |

| Cx43 | Recombinant E2 extracellular loop of Cx43 mAb | PEGylated liposome | N/Ab | Chekhonin et al. 2012 |

| Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) | EGFR | Silica shell gold nanoparticle | Near-infrared surface enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) tagsc | Diaz et al. 2013 |

| EGFR variant III (EGFRvIII) | EGFRvIII mAb | Iron oxide nanoparticle | N/Ad | Hadjipanayis et al. 2010 |

| Cetuximab (EGFR and EGFRvIII mAb) | Iron oxide nanoparticle | N/Ad | Bouras et al. 2015 | |

| Anti-EGFRvIII single domain antibody | Near-infrared quantum dot | N/Ac | Fatehi et al. 2014 | |

| IL-13Rα2 | IL-13 | Liposomal nanovesicle | Doxorubicin | Madhankumar et al. 2006, 2009 |

| Fn14 | Fn14 mAb | PEGylated polystyrene-based nanoparticle | N/Ab | Schneider et al. 2015 |

Based on calcium/phosphate nanoparticles and cationic liposomes.

Therapeutic payloads have not yet been incorporated.

Used as an optical tracking agent rather than as a therapeutic agent.

The antibody inhibits EGFR cell signaling. Thus the targeting moiety is intrinsically therapeutic, and a separate payload is not used.

3.2.1 Transferrin Receptor (TfR)

Transferrin is responsible for the regulation and distribution of circulating iron, which is required for various biological processes including DNA synthesis, cellular metabolism and proliferation [83]. TfRs are expressed on the luminal membrane of cerebral endothelial cells, and have therefore been employed in delivering therapeutic agents across the BBB via the RMT pathway [84]. Several studies have also demonstrated increased expression of the TfR on metastatic and drug resistant tumors [83]. A correlation between increased TfR expression and the tumor grade has been determined in a variety of tumor types, including glioma [85]. Both transferrin itself and anti-TfR antibodies have been conjugated to nanocarriers to actively target GBM cells in preclinical models [26]. TfR-targeted biodegradable nanoparticles have been observed to internalize into glioma cells (e.g. F98, C6, U373MG cells) via transferrin-mediated endocytosis, have significantly increased nanoparticle stability, accumulate within brain tissue in vivo, and inhibit tumor growth in vivo (e.g. C6 and U87 glioma models) compared to unencapsulated therapeutic agents (e.g. TMZ, DOX, methotrexate, p53 gene) or non-targeted versions of the therapeutic agents [86–94]. For example, Tf-targeted DOX-loaded polymersomes exhibited a 2.5-fold decrease in tumor volume compared to a non-targeted version and 5-fold decrease compared to free DOX in a U87 orthotopic brain tumor model [88]. Several transferrin-conjugated nano-based drug delivery systems for the encapsulation of anticancer therapeutic compounds have progressed into human clinical trials [95].

3.2.2 Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein (LRP)

Similarly to the transferrin receptor, both cerebral endothelial cells and glioma cells overexpress LRP. LRP mediates the transcytosis of various ligands across the BBB including lactoferrin (Lf), melanotransferrin, receptor associated protein and Angiopep-2 peptide [27]. In particular, Lf has the potential to serve as both a BBB and glioma targeting ligand, thereby enhancing the amount of drug delivered to tumor cells. A novel nanocarrier drug delivery system was designed using biodegradable polymerosomes conjugated with Lf on the surface. The polymerosomes served as carriers for both Dox and tetrandine (Tet) (Lf-PO-Dox/Tet) [27]. Lf-PO-Dox/Tet demonstrated increased cellular uptake, strong cytotoxicity against C6 glioma cells, and enhanced in vivo efficacy with a 3-fold decrease in tumor volume compared to the non-targeted formulations in a C6 intracranial rat tumor model. Additionally, in vivo imaging indicated that near-infrared dye-labeled Lf-PO entered the brain and accumulated at the tumor site 3.6 times higher than the non-targeted formulation. These results suggest a potential role for Lf-PO-Dox/Tet in the targeted therapy of gliomas.

3.2.3 αvβ3 Integrin

Integrins are ECM receptors that are expressed on the brain microvasculature and mediate the connections between cellular and matrix components in both physiological and disease states [96]. Integrins are known as regulators of angiogenesis and apoptosis, and are also involved in cellular adhesion and migration, as well as in the recognition of brain tumor cells versus astrocytes [97]. Studies have shown that αvβ3 integrin is highly overexpressed by the brain tumor vascular bed but is minimally expressed on normal blood vessels [98], resulting in clinical trials testing integrin antagonists as antiangiogenic agents for GBM patients [99–102]. Additionally, many integrin receptors bind to the tripeptide sequence Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD), which is present in various ECM proteins such as fibronectin, vitronectin, collagen, and fibrinogen [97]. Therefore, RGD-conjugated nanoparticles may be capable of effective BBB transport, brain tissue penetration, and tumor targeting for effective drug delivery. RGD-conjugated nanoparticles are rapidly internalized by endothelial cells via the αvβ3 integrin receptor [100–101, 103]. Recently, one group developed a multicomponent, chain-like nanoparticle composed of three iron oxide nanospheres and one drug-loaded liposome linked chemically into a linear chain-like assembly to effectively penetrate brain tumors [104]. They found that vascular targeting of nanochains to the αvβ3 integrin receptor of CNS-1 cells resulted in an 18.6-fold greater drug dose administered to brain tumors compared to standard chemotherapy. In vivo efficacy studies conducted in two different mouse orthotopic models of GBM, the CNS-1 and 9L glioma models, illustrated how enhanced targeting by the nanochain facilitated widespread site-specific drug delivery as indicated by a 2.6-, 3.2-, and 6-fold higher deposition in brain tumors than non-targeted nanochains, targeted liposomes, and non-targeted liposomes, respectively. Another group generated a cyclic RGD peptide-functionalized micelle encapsulating paclitaxel (cRGDyK-NP/PTX) for targeted drug delivery. This nanoparticle formulation showed the strongest penetration and accumulation in 3D U87MG glioma spheroids, and produced microtubule stabilization in U87 glioma cells in vitro. Furthermore, cRGDyK-NP/PTX resulted in increased homing specificity to glioma tumors in vivo, and produced longer mean survival times(MST) in mice bearing intracranial gliomas as indicated by a 1.2- and 1.5-fold longer MST than non-targeted NP/PTX and free taxol, respectively [28].

3.2.4 D-Glucose Transporter (GLUT)

GLUT facilitates the transport of D-glucose from the blood to the brain and has been found to be overexpressed in brain microvessels as well as in brain tumor cells; thus, GLUT targeting may be useful not only for enhanced delivery across the BBB but also for the targeted treatment of glioma cells [29]. In a recent study, Jiang et al. [105] constructed a dual-targeted drug delivery system by employing 2-deoxy-D-glucose as a targeting moiety with paclitaxel-loaded nanoparticles (DGlu-NP). In vivo fluorescent imaging indicated that DGlu-NP had high specificity and efficiency, resulting in a ~900-fold RG-2 glioma tumor fluorescence intensity increase. In vivo efficacy was significantly enhanced as indicated by a MST of 38 days for DGlu-NP compared to 31 and 32 days for taxol and non-targeted PTX-loaded NPs, respectively. Their results indicate that DGlu-NP could be a potential dual-targeted vehicle for glioma therapy.

3.2.5 Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP) and Connexin 43 (Cx43)

The peritumoral zone of high grade-gliomas is the region where perivascular and perineural invasion of glioma cells into normal brain tissue occurs [2–3]. This zone is surrounded, on the side of normal tissue, by a thick bank consisting of reactive astrocytes that express GFAP, an astrogial marker [106]. Both reactive astrocytes and the most rapidly migrating glioma cells are also positive for Cx43 [107]. Cx43 is an integral membrane protein that forms hexamers (connexons), which in turn form gap junctions permitting both cell adhesion and the exchange of different intracellular messengers [108]. Heterologous gap junctions between glioma cells and GFAP-positive astrocytes have been shown to play a role in the active migration of Cx43-positive glioma cells to the peritumoral zone [107, 109]. Cx43-positive C6 glioma cells also have higher migration capacity than Cx43-negative C6 cells [110]. Thus, both GFAP and Cx43 are promising targets for suppressing tumor invasion and for targeted delivery of therapeutics to the peritumoral zone. One group studied PEGylated liposomes conjugated to either GFAP or Cx43 monoclonal antibodies in a C6 intracranial glioma model [106]. Fluorescent-labeled liposomal particles were detected at the periphery of the glioma, where the target antigens were overexpressed. Furthermore, dynamic T1 MRI of rats injected with paramagnetic liposomes carrying anti-Cx43 showed distinct accumulation of the paramagnetic contrast agent at the periphery of the glioma. These data suggest that GFAP and Cx43 antibody decorated liposomal particles may achieve targeted delivery of diagnostic and therapeutic drugs to the peritumoral invasion zone of high-grade gliomas.

3.2.6 Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR)

EGFR is a receptor tyrosine kinase and amplification of the EGFR gene is a frequent genetic aberration associated with malignant glioma, with a frequency of about 50% [111]. Amplification and/or mutation of the EGFR gene is also found in breast, lung, and prostate cancers [112–113]. EGFR-specific inhibitors have been approved for use in patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma and are currently in clinical trials for GBM [114] However, many GBM patients do not respond to these therapies and those that do eventually show progression [115]. Consequently, efforts have been made to utilize EGFR-targeted nanotherapeutics to treat GBM. Kaluzova et al. [116] investigated the therapeutic targeting effect of cetuximab-iron-oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) against EGFR-expressing glioma stem cells (N08-74, N08-30, and N08-1002) and GBM tumor non-stem cells (U87MG and LN229). Cetuximab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to the extracellular domain of the human EGFR and has been used as a free drug to treat GBM [117]. Cetuximab-IONPs bound to EGFR-expressing GBM cells with a 60-fold increase compared to cetuximab alone [116]. Furthermore, greater binding to EGFR, inhibition of EGFR signaling, and internalization of the cetuximab-IONPs and EGFR lead to apoptosis of human EGFR-positive GBM cells [116]. In another study, Diaz et al. [118] used PEG-coated gold nanoparticles to visualize and target the tumor using an anti-EGFR antibody coating. This resulted in enhanced U251 and BT2012035 cell uptake of nanoparticles in vitro and successful delivery of nanoparticles in vivo in a 9L rat glioma model following BBB disruption using image-guided transcranial focused ultrasound.

3.2.7 Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Variant III (EGFRvIII)

EGFRvIII protein is expressed in some malignant gliomas but not in the normal brain [119]. The EGFR gene mutation encoding this variant consists of an in-frame deletion within the region encoding the extracellular domain of EGFR that splits a codon and produces a novel glycine at the fusion junction [120]. EGFRvIII is a constitutively active tyrosine kinase that enhances tumorigenicity and tumor cell migration and results in radiation and chemotherapy resistant tumor cells [121]. These properties make EGFRvIII a valuable target for antiglioma therapy. Hadjipanayis et al. [122] used 10 nm IONPs conjugated to a purified antibody that selectively binds EGFRvIII for therapeutic targeting as well as MRI contrast enhancement imaging in vitro and in vivo. The bioconjugated EGFRvIIIAb-IONPs resulted in a 2-fold decrease in GBM cell survival and a greater antitumor effect after treatment of U87MG EGFRvIII-expressing cells in comparison to GBM cells that did not express this protein (U87wtEGFR). The authors note, however, a pronounced antitumor effect of free IONPs within GBM cells, which may be due to the nonspecific uptake of the nanoparticles by the tumor cells. In another study, the same group investigated whether cetuximab-IONP treatment could increase GBM cell radiosensitivity [123]. Cetuximab-IONPs produced a 2- and 3-fold GBM antitumor effect in vitro compared to cetuximab or IONPs alone, respectively, and improved overall survival in vivo following treatment with nanoparticles and radiation therapy.

3.2.8 Interleukin-13 Receptor α Chain Variant 2 (IL13Rα2)

Another highly studied protein for GBM targeting is IL13Rα2, a tumor-restricted plasma membrane receptor overexpressed in GBM, meningiomas, peripheral nerve sheath tumors, and other peripheral tumors [124]. IL-13Rα2 is overexpressed in many GBM tumors but not in normal brain tissue [124–125]. IL13Rα2 serves as a protective “decoy” receptor that sequesters IL13, a cytokine secreted by activated T cells that elicits pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory immune responses [126], and prevents it from inducing apoptosis [127]. Madhankumar et al. described the use of human IL13-conjugated liposomes, which efficiently bind to brain cancer cells that overexpress IL13Rα2, as a potential therapy for GBM [128]. Conjugating the liposomes with human IL13 allowed for specific binding to U87 and U251 GBM cells and uptake of the liposomes via endocytosis. The IL13-liposomes served as delivery systems for Dox, allowing for a 2-fold enhanced cytotoxicity and increased accumulation and retention of the drug in cells. There was also a 1.5-fold higher tumor growth inhibition in mice bearing subcutaneous glioma tumors using IL13-liposomes compared with non-targeted liposomes. Madhankumar et al. [129] also used IL13-conjugated Dox-loaded liposomes to treat mice bearing U87 glioma cell intracranial tumors. Mice treated with IL13-targeted liposomes had a 5-fold reduction in the intracranial tumor volume and 4 out of 7 animals survived more than 200 days after tumor implantation, compared to the 35 day survival of mice treated with untargeted liposomes. The results from both studies indicate that Dox-loaded IL13-conjugated liposomes are a feasible nanoparticle drug delivery vehicle for GBM therapy [128–129].

4. Fibroblast Growth Factor-Inducible 14 (Fn14): An Emerging Therapeutic Target for GBM

4.1 Fn14 Expression in GBM Tumors and Invading GBM Cells

Fn14, a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (see Figure 2), is an emerging molecular target for GBM and other cancers [130–132]. While the Fn14 gene is not commonly mutated in GBM, the gene transcription and protein levels are consistently increased in most GBMs and these changes appear to be most significant at the invasive tumor margin [133]. As a GBM tumor target, Fn14 offers advantages over the other cell surface receptors described above because: (i) there is minimal expression in normal brain whereas most GBM tumors (~70–85%) are Fn14-positive [133], (ii) Fn14 overexpression has been confirmed in both the stationary and invasive glioma cell populations [133–134], and (iii) Fn14 undergoes constitutive receptor internalization, which could facilitate therapeutic agent delivery [135]. Previous studies have shown that Fn14 is minimally expressed in the normal human brain but highly expressed in GBM (Figure 3), including glioma cells within the invasive rim region [133–134, 136]. Furthermore, Fn14 gene expression levels increase with glioma grade and correlate inversely with patient survival [133]. Our recent analysis of the TCGA GBM database indicated that maximal Fn14 overexpression occurs in mesenchymal subtype tumors with lowest expression detected in IDH1 mutant tumors ([137] and unpublished results). These findings differentiate Fn14 from other GBM targets and indicate that Fn14 may be an optimal surface molecule for targeting therapeutics to invasive GBM cells.

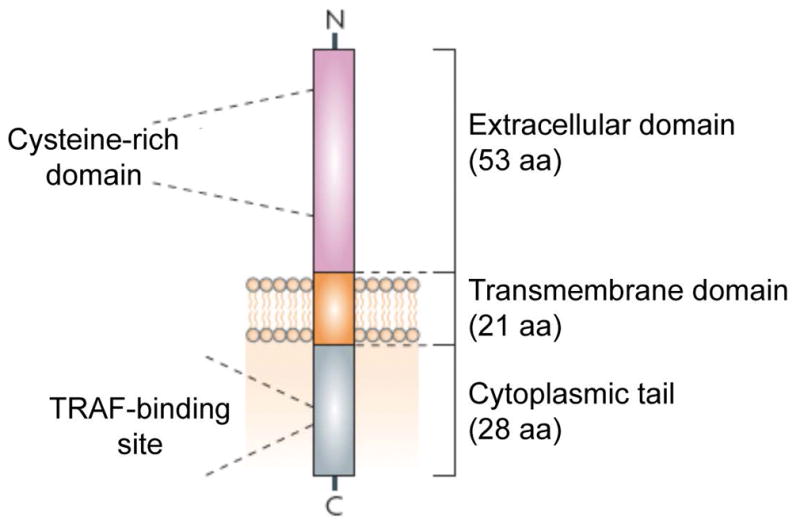

Figure 2.

A schematic representation of the human Fn14 protein is shown. Mature human Fn14 is 102 amino acids (aa) in length, with a predicted molecular mass of 10,925 daltons and a theoretical isoelectric point of 8.24. Abbreviation: TRAF, TNF receptor associated factor. Reprinted from Winkles [130] with permission from the Nature Publishing Group.

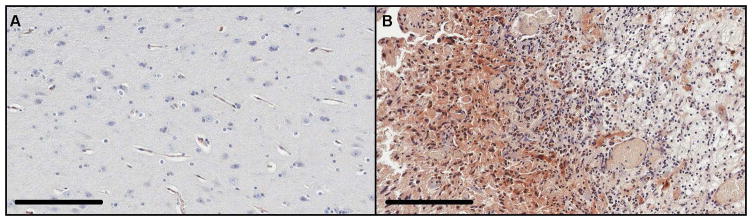

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical analysis of Fn14 protein expression in normal human brain and GBM tissue. Non-neoplastic brain tissue from a 31 year old male epilepsy patient (A) and tumor tissue from a 77 year old female patient with a right parietoccipital GBM (B) was immunostained using an anti-Fn14 antibody. Fn14 protein (brown stain) was detected in glioma cells but not in non-neoplastic tissue. Scale bar = 200 μm.

4.2 Fn14-Targeted, Tissue-Penetrating Nanotherapeutics

Regardless of passive or active targeting, nanoparticles must diffuse through the brain tissue and travel long distances in pursuit of invasive glioma cells. A major hurdle in nanoparticle diffusion in brain tissue is the barrier properties of the ECS. Thorne et al. [46] reported that the brain ECS has several fluid filled pores through which particles can diffuse. They analyzed in vivo diffusion of quantum dots and dextrans through brain ECS and reported that the nanoparticles must be approximately 30–70 nm in diameter or smaller to move through the brain interstitium. The diffusion also depends heavily on the surface properties of the nanoparticles. Low molecular weight hydrophilic PEG is often used to modify nanoparticle surfaces to provide stealth properties (i.e., increase blood circulation time). PEG also helps nanoparticles diffuse through the tissue microenvironment. Nance et al. [50] formulated densely PEG-coated polystyrene nanoparticles (114 nm) and observed that these particles could move much better through brain tissue compared to non-coated nanoparticles (>100 nm). Thus, via surface modification such as PEG coating, the upper limit of the nanoparticle size can be increased for the diffusion of larger nanoparticles to carry more quantities of payload.

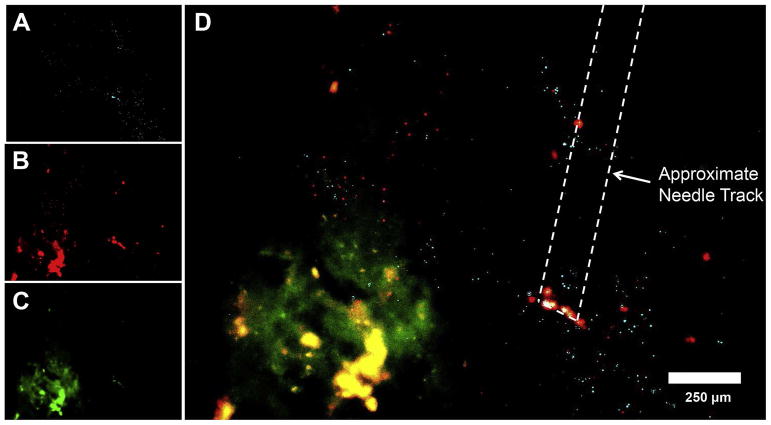

In 2015, Schneider et al. [49, 138] reported the successful engineering of model, polystyrene nanoparticles with both minimal non-specific binding and an active tumor-targeting function. A dense low molecular weight PEG surface coating was employed in order to increase nanoparticle penetration into the brain tissue and the nanoparticles were targeted to Fn14-positive U87 glioma cells by attaching an Fn14 monoclonal antibody named ITEM4 to the PEG chains. Fn14-targeted brain tissue penetrating nanoparticles were able to: (i) selectively bind to recombinant Fn14 but not brain ECM proteins in surface plasmon resonance-based BiaCore assays, (ii) exhibit increased association with Fn14-positive cells in comparison to Fn14-negative cells, and (iii) rapidly diffuse within the brain tissue, even when the PEGylated surface is decorated with the high molecular weight antibody molecules. In addition, when administered intracranially, the Fn14-targeted penetrating nanoparticles showed improved tumor cell co-localization in mice bearing human U87 GBM xenografts compared to non-targeted penetrating nanoparticles (see Figure 4). It is anticipated that nanoparticle formulations of this type might prove more successful than “conventional” nanoparticles in delivering cytotoxic agents to the invading glioma cell population while sparing normal healthy brain cells. Additional work is needed to determine if the knowledge gained in this initial proof-of-concept study can be translated to the development of drug-loaded, biodegradable nanoparticles that can be tested for therapeutic efficacy in invasive patient derived xenograft and transgenic models of GBM.

Figure 4.

In vivo distribution of non-targeted and Fn14-targeted polystyrene nanoparticles 24 hours following intracranial injection into a mouse bearing a U87/GFP cell intracranial tumor.. Representative distribution of (A) non-targeted PEG-coated nanoparticles (light blue), (B) ITEM4-conjugated PEG-coated nanoparticles (red), and (C) GFP-expressing U87 tumors (green) in mouse striatum using fluorescence microscopy. (D) Merged image where co-localization between ITEM4-conjugated PEG-coated nanoparticles and GFP-expressing U87 tumor cells is shown in yellow. Reprinted from Schneider et al. [49] with permission from Elsevier.

5. Future Perspectives

Glioblastoma (GBM) is a highly aggressive and lethal disease, largely due to the invasive nature of malignant glioma cells, which limits complete surgical removal of the tumor tissue and sufficient dosing of adjuvant therapies. Recent information related to GBM treatment barriers highlight the challenges related to key disease features; in particular, brain-invading tumor cells and genetic heterogeneity and instability. The realization that these key barriers limit efficacy has underscored the need for new therapeutic strategies that can provide sustained drug concentrations and effectively target the brain invading GBM cells. Targeted nanotherapeutics - designed to kill those GBM cells left behind after surgical resection, but not healthy human brain cells - have emerged as promising drug delivery systems with the potential to improve pharmacokinetic profiles and therapeutic efficacy. In addition, this particle-based approach will allow flexibility in changing the therapeutic agent and/or combining various therapeutic agents (multi-modal action) to tailor the treatment strategy to individual patient tumors in future applications.

Looking ahead at the future, we believe that cellular and molecular studies focused on understanding the GBM microenvironment, and in particular the invasive rim region, will provide crucial information for designing novel GBM-specific nanotherapeutics. Additionally, understanding mechanisms affecting the movement and diffusion kinetics of nanotherapeutics in normal as well as tumor tissue is vital for designing surface properties of nanotherapeutics to make particles travel long distances. These important pieces of information will help us select the best molecular targets as well as design the nanotherapeutic formulations that can reach those targets for effective GBM therapy. Currently, some potentially impactful nanotherapeutics are under clinical trials. For example, one Phase II clinical trial is currently looking into the effects of combined TMZ and intravenously administered targeted p53 gene therapy (SGT-53), which is a cationic liposome encapsulating a normal human wild type p53 DNA sequence, in patients with confirmed GBM recurrence or progression (NCT02340156). Another study, which is currently in the Phase I stage, is evaluating the safety and tolerability of EGFR(V)-EDV-Dox in order to establish the best dose level to be used in future studies (NCT02766699). EGFR(V)-EDV-Dox is a bacterially derived minicell which packages a toxic payload, Dox, into a 400nm particle that can target specific cancer cells using bispecific antibodies (BsAb). The study will later examine the body’s immune response to EGFR(V)-EDV-Dox and assess if it is effective in the treatment of patients with recurrent GBM. A third study, which was a Phase I clinical trial completed in 2014, looked into the effects of nanoliposomal CPT-11 in patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas (NCT00734682). The investigators hypothesized that this new formulation of CPT-11 would increase survival in patients with recurrent gliomas because CPT-11 is encapsulated into a liposome particle, thereby reducing toxicities from the drug. Although it is hoped that these trials will lead to promising new therapies for GBM, additional studies are warranted to identify the best particle-drug formulations that may ultimately make a significant impact on patients with this devastating disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health [K25EB018370 (A.J.K.), K08NS09043 (G.F.W.), R01CA177796 (N.L.T.)], an NIGMS Initiative for Maximizing Student Development Grant (R25GM55036 (J.G.D.)), an American Medical Association Foundation Seed Grant (D.S.H.), an Institutional Research Grant (IRG-97-153-10) from the American Cancer Society (A.J.K. and G.F.W.), a Research Scholar Grant (RSG-16-012-01) from the American Cancer Society (G.F.W.), an Elsa U. Pardee Foundation Research Grant (A.J.K. and J.A.W.), an American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists Foundation New Investigator Grant Award (A.J.K.).

References

- 1.Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant Gliomas in Adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(5):492–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodworth GF, et al. Emerging Insights into Barriers to Effective Brain Tumor Therapeutics. Frontiers in Oncology. 2014;4 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gladson CL, Prayson RA, Liu WM. The Pathobiology of Glioma Tumors. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease. 2010;5(1):33–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nabors LB, et al. Central Nervous System Cancers, Version 2.2014. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2014;12(11):1517–1523. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galicich JH, French LA, Melby JC. Use of dexamethasone in treatment of cerebral edema associated with brain tumors. J Lancet. 1961;81:46–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibamoto Y, et al. Supratentorial malignant glioma: an analysis of radiation therapy in 178 cases. Radiother Oncol. 1990;18(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(90)90018-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker MD, et al. Randomized comparisons of radiotherapy and nitrosoureas for the treatment of malignant glioma after surgery. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(23):1323–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198012043032303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stupp R, et al. High-grade glioma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(Suppl 3):iii93–101. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langer R, Folkman J. Polymers for the sustained release of proteins and other macromolecules. Nature. 1976;263(5580):797–800. doi: 10.1038/263797a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brem H, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of safety and efficacy of intraoperative controlled delivery by biodegradable polymers of chemotherapy for recurrent gliomas. The Polymer-brain Tumor Treatment Group. Lancet. 1995;345(8956):1008–12. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90755-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brem H, et al. The safety of interstitial chemotherapy with BCNU-loaded polymer followed by radiation therapy in the treatment of newly diagnosed malignant gliomas: phase I trial. J Neurooncol. 1995;26(2):111–23. doi: 10.1007/BF01060217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valtonen S, et al. Interstitial chemotherapy with carmustine-loaded polymers for high-grade gliomas: a randomized double-blind study. Neurosurgery. 1997;41(1):44–8. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199707000-00011. discussion 48–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westphal M, et al. A phase 3 trial of local chemotherapy with biodegradable carmustine (BCNU) wafers (Gliadel wafers) in patients with primary malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2003;5(2):79–88. doi: 10.1215/S1522-8517-02-00023-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westphal M, et al. Gliadel wafer in initial surgery for malignant glioma: long-term follow-up of a multicenter controlled trial. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006;148(3):269–75. doi: 10.1007/s00701-005-0707-z. discussion 275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart LA. Chemotherapy in adult high-grade glioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 12 randomised trials. Lancet. 2002;359(9311):1011–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stupp R, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cloughesy TF, Cavenee WK, Mischel PS. Glioblastoma: From Molecular Pathology to Targeted Treatment. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease. 2014;9(1):1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huse JT, Holland E, DeAngelis LM. Glioblastoma: Molecular Analysis and Clinical Implications. Annual Review of Medicine. 2013;64(1):59–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-100711-143028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iliff JJ, et al. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid β. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4(147):147ra111–147ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sykova E, Nicholson C. Diffusion in Brain Extracellular Space. Physiological Reviews. 2008;88(4):1277–1340. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pardridge WM. The blood-brain barrier: Bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRX. 2005;2(1):3–14. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S, et al. The role of pericytes in blood-brain barrier function and stroke. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(25):3653–62. doi: 10.2174/138161212802002706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armulik A, et al. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature. 2010;468(7323):557–61. doi: 10.1038/nature09522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Obermeier B, Daneman R, Ransohoff RM. Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Med. 2013;19(12):1584–1596. doi: 10.1038/nm.3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groothuis DR. The blood-brain and blood-tumor barriers: A review of strategies for increasing drug delivery. Neuro-Oncology. 2000;2(1):45–59. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/2.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tortorella S, Karagiannis TC. Transferrin Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis: A Useful Target for Cancer Therapy. The Journal of Membrane Biology. 2014;247(4):291–307. doi: 10.1007/s00232-014-9637-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pang Z, et al. Lactoferrin-Conjugated Biodegradable Polymersome Holding Doxorubicin and Tetrandrine for Chemotherapy of Glioma Rats. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2010;7(6):1995–2005. doi: 10.1021/mp100277h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang X, et al. Integrin-facilitated transcytosis for enhanced penetration of advanced gliomas by poly(trimethylene carbonate)-based nanoparticles encapsulating paclitaxel. Biomaterials. 2013;34(12):2969–2979. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorin F, et al. Perinecrotic glioma proliferation and metabolic profile within an intracerebral tumor xenograft. Acta Neuropathologica. 2004;107(3):235–244. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0803-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chertok B, et al. Iron oxide nanoparticles as a drug delivery vehicle for MRI monitored magnetic targeting of brain tumors. Biomaterials. 2008;29(4):487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarin H, et al. Physiologic upper limit of pore size in the blood-tumor barrier of malignant solid tumors. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2009;7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muldoon LL, et al. Chemotherapy Delivery Issues in Central Nervous System Malignancy: A Reality Check. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(16):2295–2305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.9861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tate MC, Aghi MK. Biology of angiogenesis and invasion in glioma. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6(3):447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hersh DS, et al. Evolving Drug Delivery Strategies to Overcome the Blood Brain Barrier. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(9):1177–93. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666151221150733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joshi S, et al. Inconsistent blood brain barrier disruption by intraarterial mannitol in rabbits: implications for chemotherapy. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2011;104(1):11–19. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0466-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duffy KR, Pardridge WM. Blood-Brain-Barrier Transcytosis of Insulin in Developing Rabbits. Brain Research. 1987;420(1):32–38. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dehouck B, et al. A new function for the LDL receptor: Transcytosis of LDL across the blood-brain barrier. Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;138(4):877–889. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.4.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fishman JB, et al. Receptor-mediated transcytosis of transferrin across the blood-brain barrier. J Neurosci Res. 1987;18(2):299–304. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490180206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pardridge WM, Buciak JL, Friden PM. Selective transport of an anti-transferrin receptor antibody through the blood-brain barrier in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;259(1):66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin SU, et al. Transferrin-antibody fusion proteins are effective in brain targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(7):2820–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu YJ, et al. Boosting brain uptake of a therapeutic antibody by reducing its affinity for a transcytosis target. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(84):84ra44. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clark AJ, Davis ME. Increased brain uptake of targeted nanoparticles by adding an acid-cleavable linkage between transferrin and the nanoparticle core. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(40):12486–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517048112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bobo RH, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery of macromolecules in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(6):2076–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kunwar S, et al. Phase III randomized trial of CED of IL13-PE38QQR vs Gliadel wafers for recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12(8):871–81. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henson JW, Cordon-Cardo C, Posner JB. P-glycoprotein expression in brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 1992;14(1):37–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00170943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thorne RG, Nicholson C. In vivo diffusion analysis with quantum dots and dextrans predicts the width of brain extracellular space. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(14):5567–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509425103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolak DJ, Thorne RG. Diffusion of macromolecules in the brain: implications for drug delivery. Mol Pharm. 2013;10(5):1492–504. doi: 10.1021/mp300495e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tzeng SY, Green JJ. Therapeutic nanomedicine for brain cancer. Therapeutic Delivery. 2013;4(6):687–704. doi: 10.4155/tde.13.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schneider CS, et al. Minimizing the non-specific binding of nanoparticles to the brain enables active targeting of Fn14-positive glioblastoma cells. Biomaterials. 2015;42:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nance EA, et al. A Dense Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Coating Improves Penetration of Large Polymeric Nanoparticles Within Brain Tissue. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4(149):149ra119–149ra119. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brennan C, et al. Glioblastoma Subclasses Can Be Defined by Activity among Signal Transduction Pathways and Associated Genomic Alterations. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(11):e7752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verhaak RGW, et al. Integrated Genomic Analysis Identifies Clinically Relevant Subtypes of Glioblastoma Characterized by Abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(1):98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patel AP, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science. 2014;344(6190):1396–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1254257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parker NR, et al. Molecular heterogeneity in glioblastoma: potential clinical implications. Front Oncol. 2015;5:55. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aubry M, et al. From the core to beyond the margin: a genomic picture of glioblastoma intratumor heterogeneity. Oncotarget. 2015;6(14):12094–109. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gill BJ, et al. MRI-localized biopsies reveal subtype-specific differences in molecular and cellular composition at the margins of glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(34):12550–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405839111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramirez YP, et al. Glioblastoma multiforme therapy and mechanisms of resistance. Pharmaceuticals. 2013;6(12):1475–1506. doi: 10.3390/ph6121475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sampson JH, et al. Immunologic escape after prolonged progression-free survival with epidermal growth factor receptor variant III peptide vaccination in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(31):4722–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.6963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jackson M, Hassiotou F, Nowak A. Glioblastoma stem-like cells: at the root of tumor recurrence and a therapeutic target. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36(2):177–185. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stopschinski BE, Beier CP, Beier D. Glioblastoma cancer stem cells--from concept to clinical application. Cancer Lett. 2013;338(1):32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim S-S, et al. The Clinical Potential of Targeted Nanomedicine: Delivering to Cancer Stem-like Cells. Mol Ther. 2014;22(2):278–291. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jose Alonso M. Nanomedicines for overcoming biological barriers. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2004;58(3):168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jain KK. Advances in the field of nanooncology. BMC Medicine. 2010;8:83–83. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beduneau A, Saulnier P, Benoit J-P. Active targeting of brain tumors using nanocarriers. Biomaterials. 2007;28(33):4947–4967. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pourgholi F, et al. Nanoparticles: Novel vehicles in treatment of Glioblastoma. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2016;77:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alam MI, et al. Strategy for effective brain drug delivery. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2010;40(5):385–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jenne JW. Non-invasive transcranial brain ablation with high-intensity focused ultrasound. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2015;36:94–105. doi: 10.1159/000366241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.D’Amico RS, Kennedy BC, Bruce JN. Neurosurgical oncology: advances in operative technologies and adjuncts. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2014;119(3):451–463. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1493-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cohen-Inbar O, Xu Z, Sheehan JP. Focused ultrasound-aided immunomodulation in glioblastoma multiforme: a therapeutic concept. Journal of Therapeutic Ultrasound. 2016;4(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40349-016-0046-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burgess A, Hynynen K. Noninvasive and Targeted Drug Delivery to the Brain Using Focused Ultrasound. ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 2013;4(4):519–526. doi: 10.1021/cn300191b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Phukan K, et al. Nanosized Drug Delivery Systems for Direct Nose to Brain Targeting: A Review. Recent Patents on Drug Delivery & Formulation. 2016;10(2):156–164. doi: 10.2174/1872211310666160321123936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pardridge WM. Blood-brain barrier delivery. Drug Discovery Today. 2007;12(1–2):54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Danhier F, Feron O, Preat V. To exploit the tumor microenvironment: Passive and active tumor targeting of nanocarriers for anti-cancer drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release. 2010;148(2):135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A New Concept for Macromolecular Therapeutics in Cancer Chemotherapy: Mechanism of Tumoritropic Accumulation of Proteins and the Antitumor Agent Smancs. Cancer Research. 1986;46(8):6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wadajkar AS, Menon JU, Nguyen KT. Polymer-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Reviews in Nanoscience and Nanotechnology. 2012;1(4):284–297. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yuan F, et al. Vascular Permeability in a Human Tumor Xenograft: Molecular Size Dependence and Cutoff Size. Cancer Research. 1995;55(17):3752–3756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Householder KT, et al. Intravenous delivery of camptothecin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles for the treatment of intracranial glioma. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2015;479(2):374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kafa H, et al. The interaction of carbon nanotubes with an in vitro blood-brain barrier model and mouse brain in vivo. Biomaterials. 2015;53:437–452. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ambruosi A, et al. Biodistribution of polysorbate 80-coated doxorubicin-loaded [14C]-poly(butyl cyanoacrylate) nanoparticles after intravenous administration to glioblastoma-bearing rats. Journal of Drug Targeting. 2006;14(2):97–105. doi: 10.1080/10611860600636135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cho K, et al. Therapeutic Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery in Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14(5):1310–1316. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bamrungsap S, et al. Nanotechnology in therapeutics: a focus on nanoparticles as a drug delivery system. Nanomedicine. 2012;7(8):1253–1271. doi: 10.2217/nnm.12.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marcucci F, Lefoulon Fo. Active targeting with particulate drug carriers in tumor therapy: fundamentals and recent progress. Drug Discovery Today. 2004;9(5):219–228. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02988-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brandsma ME, Jevnikar AM, Ma S. Recombinant human transferrin: beyond iron binding and transport. Biotechnol Adv. 2011;29(2):230–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dufès C, Al Robaian M, Somani S. Transferrin and the transferrin receptor for the targeted delivery of therapeutic agents to the brain and cancer cells. Ther Deliv. 2013;4(5):629–40. doi: 10.4155/tde.13.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Prior R, Reifenberger G, Wechsler W. Transferrin receptor expression in tumours of the human nervous system: relation to tumour type, grading and tumour growth fraction. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1990;416(6):491–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01600299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chang J, et al. Transferrin adsorption onto PLGA nanoparticles governs their interaction with biological systems from blood circulation to brain cancer cells. Pharm Res. 2012;29(6):1495–505. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0624-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu G, et al. Transferrin-modified Doxorubicin-loaded biodegradable nanoparticles exhibit enhanced efficacy in treating brain glioma-bearing rats. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2013;28(9):691–6. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2013.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pang Z, et al. Enhanced intracellular delivery and chemotherapy for glioma rats by transferrin-conjugated biodegradable polymersomes loaded with doxorubicin. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22(6):1171–80. doi: 10.1021/bc200062q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li Y, et al. A dual-targeting nanocarrier based on poly(amidoamine) dendrimers conjugated with transferrin and tamoxifen for treating brain gliomas. Biomaterials. 2012;33(15):3899–908. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Porru M, et al. Medical treatment of orthotopic glioblastoma with transferrin-conjugated nanoparticles encapsulating zoledronic acid. Oncotarget. 2014;5(21):10446–59. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jain A, et al. Surface engineered polymeric nanocarriers mediate the delivery of transferrin-methotrexate conjugates for an improved understanding of brain cancer. Acta Biomater. 2015;24:140–51. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim SS, et al. Encapsulation of temozolomide in a tumor-targeting nanocomplex enhances anti-cancer efficacy and reduces toxicity in a mouse model of glioblastoma. Cancer Lett. 2015;369(1):250–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim SS, et al. A nanoparticle carrying the p53 gene targets tumors including cancer stem cells, sensitizes glioblastoma to chemotherapy and improves survival. ACS Nano. 2014;8(6):5494–514. doi: 10.1021/nn5014484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim SS, et al. A tumor-targeting p53 nanodelivery system limits chemoresistance to temozolomide prolonging survival in a mouse model of glioblastoma multiforme. Nanomedicine. 2015;11(2):301–11. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.van der Meel R, et al. Ligand-targeted particulate nanomedicines undergoing clinical evaluation: current status. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(10):1284–98. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Baeten KM, Akassoglou K. Extracellular matrix and matrix receptors in blood-brain barrier formation and stroke. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;71(11):1018–39. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mattern RH, et al. Glioma cell integrin expression and their interactions with integrin antagonists: Research Article. Cancer Ther. 2005;3A:325–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Brooks PC, Clark RA, Cheresh DA. Requirement of vascular integrin alpha v beta 3 for angiogenesis. Science. 1994;264(5158):569–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7512751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Reardon DA, et al. Cilengitide: an integrin-targeting arginine-glycine-aspartic acid peptide with promising activity for glioblastoma multiforme. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17(8):1225–35. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.8.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Danhier F, et al. Targeting of tumor endothelium by RGD-grafted PLGA-nanoparticles loaded with paclitaxel. J Control Release. 2009;140(2):166–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Reddy GR, et al. Vascular targeted nanoparticles for imaging and treatment of brain tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(22):6677–86. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Phuphanich S, Brat DJ, Olson JJ. Delivery systems and molecular targets of mechanism-based therapies for GBM. Expert Rev Neurother. 2004;4(4):649–63. doi: 10.1586/14737175.4.4.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kiessling F, et al. RGD-labeled USPIO inhibits adhesion and endocytotic activity of alpha v beta3-integrin-expressing glioma cells and only accumulates in the vascular tumor compartment. Radiology. 2009;253(2):462–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2532081815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Peiris PM, et al. Treatment of Invasive Brain Tumors Using a Chain-like Nanoparticle. Cancer Res. 2015;75(7):1356–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jiang X, et al. Nanoparticles of 2-deoxy-D-glucose functionalized poly(ethylene glycol)-co-poly(trimethylene carbonate) for dual-targeted drug delivery in glioma treatment. Biomaterials. 2014;35(1):518–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.09.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chekhonin VP, et al. Targeted delivery of liposomal nanocontainers to the peritumoral zone of glioma by means of monoclonal antibodies against GFAP and the extracellular loop of Cx43. Nanomedicine. 2012;8(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Oliveira R, et al. Contribution of gap junctional communication between tumor cells and astroglia to the invasion of the brain parenchyma by human glioblastomas. BMC Cell Biol. 2005;6(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schulz R, et al. Connexin 43 is an emerging therapeutic target in ischemia/reperfusion injury, cardioprotection and neuroprotection. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;153:90–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bates DC, et al. Connexin43 enhances glioma invasion by a mechanism involving the carboxy terminus. Glia. 2007;55(15):1554–64. doi: 10.1002/glia.20569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lin JH, et al. Connexin 43 enhances the adhesivity and mediates the invasion of malignant glioma cells. J Neurosci. 2002;22(11):4302–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04302.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Padfield E, Ellis HP, Kurian KM. Current Therapeutic Advances Targeting EGFR and EGFRvIII in Glioblastoma. Front Oncol. 2015;5:5. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Taylor TE, Fa FB, Cavenee WK. Targeting EGFR for Treatment of Glioblastoma: Molecular Basis to Overcome Resistance. Current Cancer Drug Targets. 2012;12(3):197–209. doi: 10.2174/156800912799277557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yarden Y, Pines G. The ERBB network: at last, cancer therapy meets systems biology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(8):553–63. doi: 10.1038/nrc3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tebbutt N, Pedersen MW, Johns TG. Targeting the ERBB family in cancer: couples therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(9):663–73. doi: 10.1038/nrc3559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Huang HS, et al. The enhanced tumorigenic activity of a mutant epidermal growth factor receptor common in human cancers is mediated by threshold levels of constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation and unattenuated signaling. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(5):2927–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kaluzova M, et al. Targeted therapy of glioblastoma stem-like cells and tumor non-stem cells using cetuximab-conjugated iron-oxide nanoparticles. Oncotarget. 2015;6(11):8788–806. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Eller JL, et al. Activity of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody C225 against glioblastoma multiforme. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(4):1005–13. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200210000-00028. discussion 1013–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Diaz RJ, et al. Focused ultrasound delivery of Raman nanoparticles across the blood-brain barrier: potential for targeting experimental brain tumors. Nanomedicine. 2014;10(5):1075–87. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Frederick L, et al. Diversity and frequency of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in human glioblastomas. Cancer Res. 2000;60(5):1383–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Batra SK, et al. Epidermal growth factor ligand-independent, unregulated, cell-transforming potential of a naturally occurring human mutant EGFRvIII gene. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6(10):1251–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sampson JH, et al. An epidermal growth factor receptor variant III-targeted vaccine is safe and immunogenic in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(10):2773–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hadjipanayis CG, et al. EGFRvIII antibody-conjugated iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic resonance imaging-guided convection-enhanced delivery and targeted therapy of glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2010;70(15):6303–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bouras A, Kaluzova M, Hadjipanayis CG. Radiosensitivity enhancement of radioresistant glioblastoma by epidermal growth factor receptor antibody-conjugated iron-oxide nanoparticles. J Neurooncol. 2015;124(1):13–22. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1807-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Debinski W, et al. Receptor for interleukin 13 is a marker and therapeutic target for human high-grade gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(5):985–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Debinski W, et al. Receptor for interleukin 13 is abundantly and specifically over-expressed in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Oncol. 1999;15(3):481–6. doi: 10.3892/ijo.15.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.McKenzie AN, et al. Interleukin 13, a T-cell-derived cytokine that regulates human monocyte and B-cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(8):3735–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hsi LC, et al. Silencing IL-13Rα2 promotes glioblastoma cell death via endogenous signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10(7):1149–60. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Madhankumar AB, et al. Interleukin-13 receptor-targeted nanovesicles are a potential therapy for glioblastoma multiforme. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(12):3162–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Madhankumar AB, et al. Efficacy of interleukin-13 receptor-targeted liposomal doxorubicin in the intracranial brain tumor model. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(3):648–54. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Winkles JA. The TWEAK-Fn14 cytokine-receptor axis: discovery, biology and therapeutic targeting. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(5):411–25. doi: 10.1038/nrd2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Cheng E, et al. TWEAK/Fn14 Axis-Targeted Therapeutics: Moving Basic Science Discoveries to the Clinic. Front Immunol. 2013;4:473. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Perez JG, et al. The TWEAK receptor Fn14 is a potential cell surface portal for targeted delivery of glioblastoma therapeutics. Oncogene. 2016;35(17):2145–55. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Tran NL, et al. Increased fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14 expression levels promote glioma cell invasion via Rac1 and nuclear factor-kappaB and correlate with poor patient outcome. Cancer Res. 2006;66(19):9535–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Fortin SP, et al. Cdc42 and the guanine nucleotide exchange factors Ect2 and trio mediate Fn14-induced migration and invasion of glioblastoma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10(7):958–68. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Gurunathan S, et al. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14 (Fn14) expression levels via ligand-independent lysosomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(19):12976–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.563478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Tran NL, et al. The human Fn14 receptor gene is up-regulated in migrating glioma cells in vitro and overexpressed in advanced glial tumors. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(4):1313–21. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63927-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Perez JG, et al. The TWEAK receptor Fn14 is a potential cell surface portal for targeted delivery of glioblastoma therapeutics. Oncogene. 2016;35(17):2145–2155. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Schneider CS, et al. Surface plasmon resonance as a high throughput method to evaluate specific and non-specific binding of nanotherapeutics. J Control Release. 2015;219:331–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]