Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the association between migraine and body composition status as estimated based on body mass index and WHO physical status categories.

Methods:

Systematic electronic database searches were conducted for relevant studies. Two independent reviewers performed data extraction and quality appraisal. Odds ratios (OR) and confidence intervals (CI) were pooled using a random effects model. Significant values, weighted effect sizes, and tests of homogeneity of variance were calculated.

Results:

A total of 12 studies, encompassing data from 288,981 unique participants, were included. The age- and sex-adjusted pooled risk of migraine in those with obesity was increased by 27% compared with those of normal weight (odds ratio [OR] 1.27; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.16–1.37, p < 0.001) and remained increased after multivariate adjustments. Although the age- and sex-adjusted pooled migraine risk was increased in overweight individuals (OR 1.08; 95% CI 1.04, 1.12, p < 0.001), significance was lost after multivariate adjustments. The age- and sex-adjusted pooled risk of migraine in underweight individuals was marginally increased by 13% compared with those of normal weight (OR 1.13; 95% CI 1.02, 1.24, p < 0.001) and remained increased after multivariate adjustments.

Conclusions:

The current body of evidence shows that the risk of migraine is increased in obese and underweight individuals. Studies are needed to confirm whether interventions that modify obesity status decrease the risk of migraine.

Both migraine and obesity are conditions associated with substantial personal and societal burdens.1 As obesity is a potentially modifiable risk factor, the relationship between migraine and obesity has been a focus of research interest for the last decade.1–3 Although several studies support that obesity is associated with an increased risk of migraine, results are inconsistent with regards to included populations, how obesity status is categorized, and other features of individual study design and conduct, and the conclusions drawn.1,4

In the extant literature of studies examining the migraine–obesity association, population inclusion criteria have varied by important modifiers of both disorders, most notably age and sex. While some studies included adults of all ages,5–7 others were limited to younger3,8,9 or older10–12 populations, whereas others stratified by age (e.g., <50 and ≥50 years).13,14 Likewise, some studies included both men and women (combined or stratified),1 whereas others were limited to only women.3,9–12

The operational definition of exposure and outcome categories has also varied substantially across studies. Although most studies reported using the WHO physical status categories,15 some compared obese individuals (body mass index [BMI] ≥30) with those who were nonobese (e.g., underweight, overweight, and normal weight combined [BMI <30]),12,14 others compared obese (BMI ≥30) with normal weight (BMI 18.5–29.9) individuals,3,13 whereas others compared those in partial obesity grades (e.g., BMI 30–34.9, BMI 35–39.9, BMI ≥40) with normal weight individuals6,7,9 (table e-1 at Neurology.org).

Prior research from our team, utilizing 2 distinct populations, demonstrated that the association between migraine and obesity was greater in younger (<50–55 years) than older individuals and women than men.13,14 Given these findings, we hypothesized that age and sex are important covariates for the migraine–obesity association and that differences in the strength of this association across studies were likely attributable to differences in study methodology, particularly in regards to age, sex, and obesity status categorization, across the included populations. Thus, we conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the pooled risk of migraine by body composition status as characterized by the WHO physical status categories and the influence of age and sex on this relationship.

METHODS

Information sources and study selection.

This meta-analysis was conducted according to guidelines of Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology.16 Systematic searches of peer-reviewed, published research articles indexed in PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science, BIOSIS, and Science Direct from inception until February 2016 were undertaken using key search terms related to obesity and migraine. Key search terms included “migraine and obesity,” “migraine and body mass index,” “migraine and BMI,” “headache and obesity,” “headache and body mass index,” and “headache and BMI.” One reviewer (H.L.N.) performed initial eligibility screening by assessing titles and abstracts of all results. Following initial screening, 2 reviewers (H.L.N., B.G.) independently reviewed full-text copies of potentially eligible articles. Disagreement was resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (B.L.P.).

Eligibility criteria.

Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) full-length articles published in peer-reviewed journals; (2) observational studies (prospective cohort, retrospective cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional); (3) reported quantitative summaries on the relationship between BMI and migraine (e.g., counts, prevalence, odds ratios [ORs]); (4) evaluated study participants ≥18 years of age at time of outcome assessment; (5) utilized comparison group without the exposure or outcome; and (6) utilized the WHO physical status categories for non-Asian populations. Exclusion criteria were (1) non-human studies; (2) non-English language; (3) case series or case reports; (4) review articles or letters to the editor; and (5) multiple reports from the same cohort. Study authors were contacted to request additional data in all cases where studies fulfilled all inclusion and exclusion criteria except for use of the WHO physical status categories for non-Asian populations.

Study appraisal and evaluation of risk of bias.

Information from each study was compiled using a data extraction sheet that included first author name, publication year, sample country origin, study design, sample size, study population characteristics (e.g., age, sex), and method of migraine and obesity classification. The risk of bias in individual studies was evaluated based on a modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cross-sectional studies (table e-2; ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp).17,18 Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plots and by the Egger test.

Statistical analyses.

OR and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were used as measures of association. If a study did not report ORs, but reported the frequency of migraine according to WHO physical status categories based on the BMI, ORs were calculated, and the corresponding author was contacted for unpublished data whenever possible. Given that the included studies differed with regard to population samples, methods of exposure and outcome ascertainment, and potential confounders adjusted for, the ORs were pooled using the random effects model that included between-study heterogeneity.19–21 The pooled estimates were consistent when analyses were repeated using a fixed-effects model. In addition, sensitivity analyses were conducted. The first sensitivity analysis consisted of omitting one study at a time and recalculating the pooled ORs for the remainder of those studies in the meta-analysis and that showed that no single study substantially influenced the pooled estimates. Second, sensitivity analyses excluding the study with the largest sample size from the multivariate adjusted OR summary analysis were conducted. Third, sensitivity analyses were conducted to compare outcome and exposure ascertainment methods (self-report vs non–self-report). Finally, sensitivity analyses excluding the low-quality studies (i.e., <7/10 on the NOS) were planned but not needed as the NOS score was ≥7 for all included studies. ORs and 95% CIs are reported for the relationship of obesity status with migraine on forest plots, with I2 statistics, to evaluate heterogeneity. Due to variations in level of adjustment for confounding across studies, we conducted separate analyses for unadjusted, sex- and age-adjusted, and multivariate adjusted studies. The list of adjustment variables for each study included in the meta-analyses is indicated in table e-3.

RESULTS

Studies retrieved.

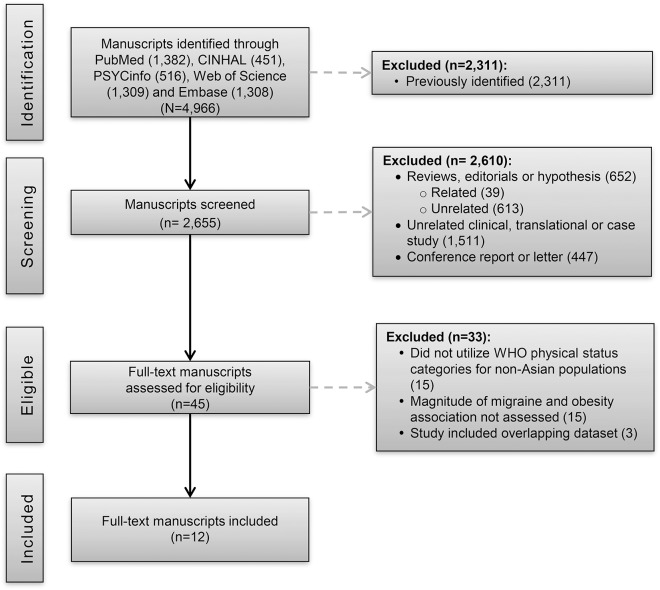

Figure 1 shows the study selection process and literature search results. The systematic search yielded 4,966 references, of which 2,655 were unique. The title and abstract reviews rejected 2,610 references, yielding 45 candidate abstracts. A subsequent full-text review rejected 33 of these references, yielding 12 candidate studies.2,3,5,6,9,12–14,22–25 Each was reviewed and selected for data extraction.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart of systematic literature review and article identification.

Study characteristics.

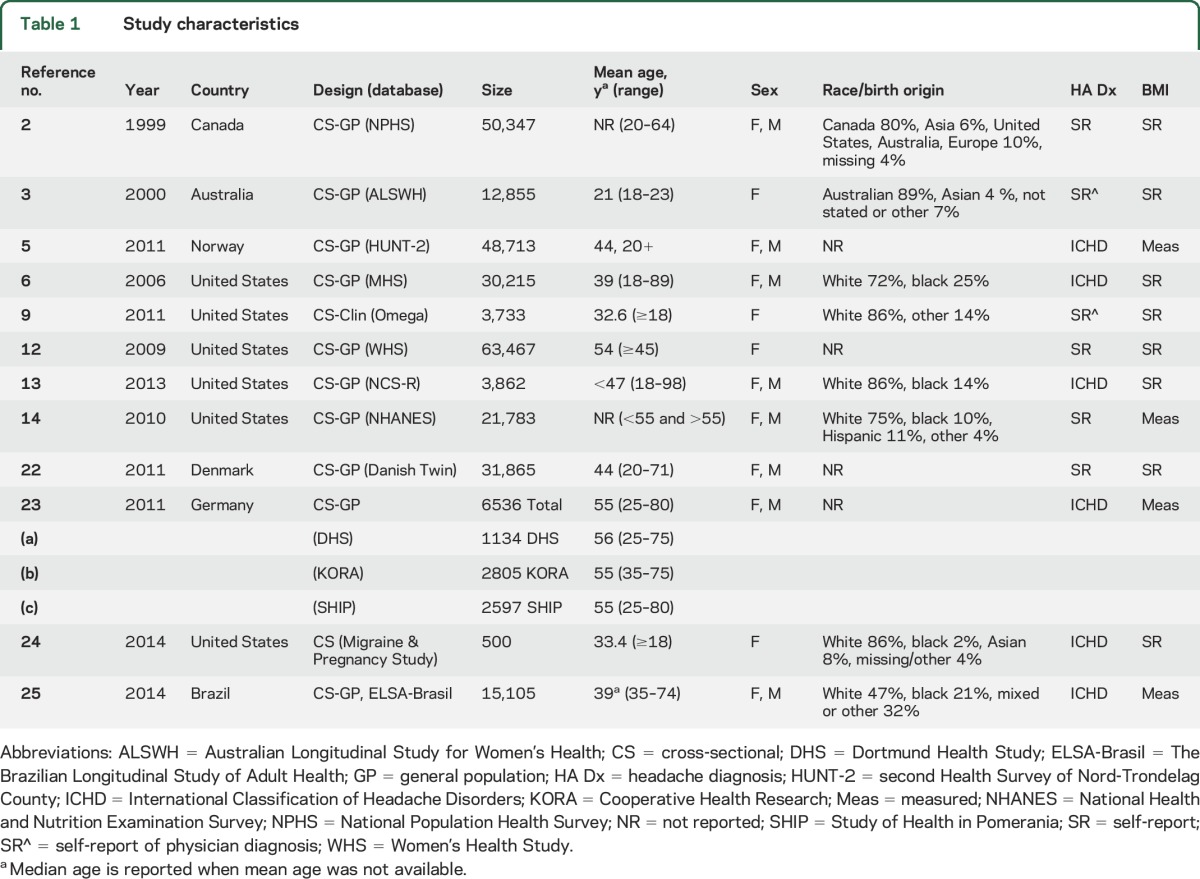

Study characteristics are shown in table 1. Twelve studies with data from 288,981 unique participants were included. Age ranged between 18 and 98 years. Two studies included predominantly older participants (mean participant age >50 years12,23) and the rest predominantly younger participants (n = 10). Five studies reported sex-stratified analyses,5,6,13,14,22 2 studies adjusted for sex only as a classic confounder,2,23 4 studies were conducted in women alone,3,9,12,24 and 1 study included both sexes did not adjust or stratify for sex.25 The majority of the studies utilized self-reported height and weight to estimate obesity status (n = 82,3,6,9,12,13,22,24) and half utilized self-report of non–International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) classification of migraine (n = 62,3,9,12,14,22). The modified Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment scores for all studies ranged between 7 and 10 out of 10 total points (table e-2).

Table 1.

Study characteristics

Association between obesity (BMI ≥30) and migraine.

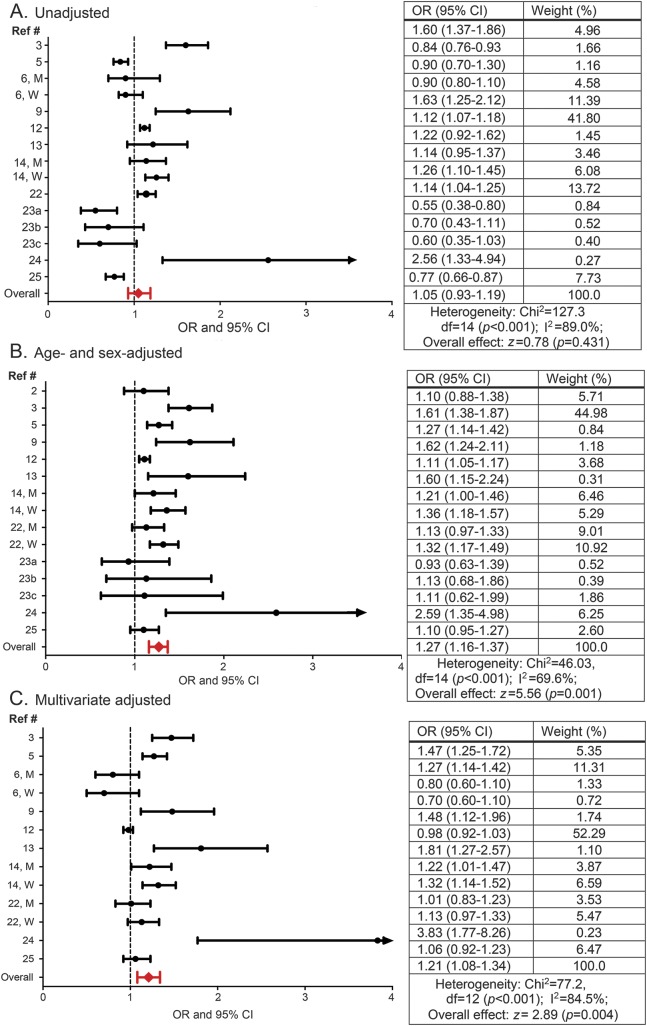

The OR of migraine for obese as compared with normal weight individuals ranged from 0.55 (95% CI 0.38–0.8023) to 2.56 (95% CI 1.33–4.9425) for unadjusted, from 0.93 (95% CI 0.63–1.3923) to 2.59 (95% CI 1.35–4.9824) for age- and sex-adjusted, and from 0.70 (95% CI 0.60–1.106) to 3.83 (95% CI 1.77–8.2624) for multivariate adjusted models (figure 2). In pooled estimates, the OR of migraine in obese compared with normal weight individuals was 1.05 (95% CI 0.93–1.19) in the unadjusted model, 1.27 (1.16–1.37) in the age- and sex-adjusted model, and 1.21 (95% CI 1.08–1.34) in the multivariate adjusted model (figure 2). Approximately 84.5% of the variability between studies' measures of association was due to the presence of heterogeneity (I2 statistic, p < 0.001). A sensitivity analysis was done excluding the study with the largest sample size12 from the multivariate adjusted OR summary analysis. In this sensitivity analysis, the multivariate OR for the remaining studies (OR 1.22; 95% CI 1.08–1.37) was similar to the multivariate adjusted pooled OR for the complete dataset. Finally, visual inspection of the funnel plot did not show evidence of a significant publication bias, confirmed by the Egger test for publication bias (H0: intercept = 2.17; p value = 0.06).

Figure 2. Association between migraine and obesity.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each individual study evaluating the association between migraine and obesity as well as the pooled (i.e., overall) OR and CI for these studies when (A) unadjusted, (B) adjusted for age and sex, and (C) multivariate adjusted for age (reference 6 did not include age in multivariate adjusted models), sex (when possible sex-stratified results are presented), and additional variables as conducted by the individual studies. See table e-3 for complete list of these variables.

Association between overweight (BMI 25–29.9) status and migraine.

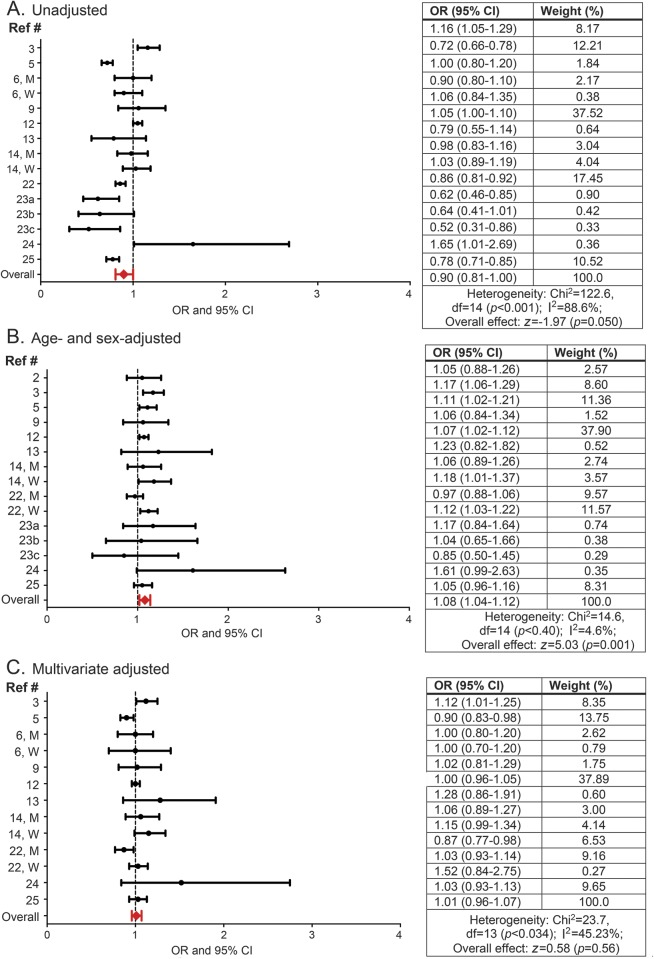

The OR of migraine for overweight as compared with normal weight individuals ranged from 0.52 (95% CI 0.31–0.8623) to 1.65 (95% CI 1.01–2.6924) for unadjusted, from 0.85 (95% CI 0.50–1.4523) to 1.61 (95% CI 0.99–2.6324) for age- and sex-adjusted, and from 0.87 (95% CI 0.77–0.9822) to 1.52 (95% CI 0.84–2.7524) for multivariate adjusted models (figure 3). In pooled estimates, the OR of migraine in overweight compared with normal weight individuals was 0.90 (95% CI 0.81–1.00) in the unadjusted model, 1.08 (1.04–1.12) in the age- and sex-adjusted model, and 1.01 (0.96–1.07) in the multivariate adjusted model (figure 3). Approximately 45.2% of the variability between studies' measures of association was due to heterogeneity assessed through the statistic I2 (p = 0.034) in multivariate adjusted model. In a sensitivity analysis excluding the study with the largest sample size,12 the multivariate OR for the remaining studies (OR 1.02; 95% CI 0.96–1.08) was similar to the multivariate adjusted pooled OR for the complete dataset.

Figure 3. Association between overweight status and migraine.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each individual study evaluating the association between overweight status and migraine as well as the pooled (i.e., overall) OR and CI for these studies when (A) unadjusted, (B) adjusted for age and sex, and (C) multivariate adjusted for age (reference 6 did not include age in multivariate adjusted models), sex (when possible sex-stratified results are presented), and additional variables as conducted by the individual studies. See table e-3 for complete list of these variables.

Association between underweight (BMI <18.5) status and migraine.

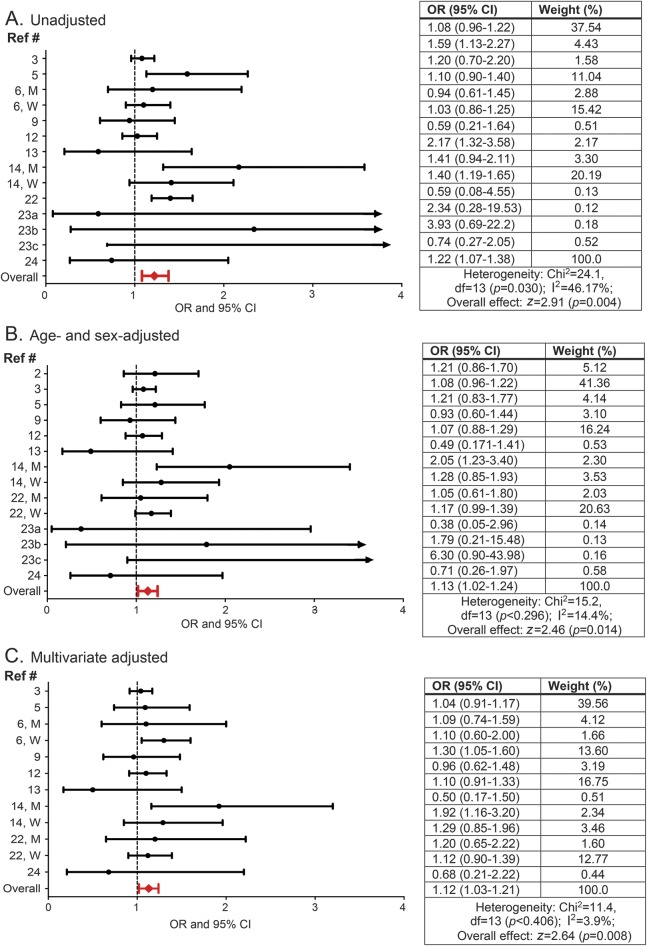

The OR of migraine for underweight individuals compared with normal weight ranged from 0.59 (95% CI 0.21–1.6413) to 3.93 (95% CI 0.69–22.2023) for unadjusted, from 0.38 (95% CI 0.05–2.9623) to 6.30 (95% CI 0.90–43.9823) for age- and sex-adjusted, and from 0.50 (95% CI 0.17–1.5013) to 1.92 (95% CI 1.16–3.2014) for multivariate adjusted models (figure 4). In pooled estimates, the OR of migraine in underweight individuals as compared with normal weight individuals was 1.22 (95% CI 1.07–1.38) in the unadjusted model, 1.13 (1.02–1.24) in the age- and sex-adjusted model, and 1.12 (1.03–1.21) in the multivariate adjusted model, with no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 3.9%, p = 0.40; figures 2 and 3). In a sensitivity analysis excluding the study with the largest sample size,12 the multivariate OR for the remaining studies (OR 1.13; 95% CI 1.02–1.25) was similar to the multivariate adjusted pooled OR for the complete dataset.

Figure 4. Association between underweight status and migraine.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each individual study evaluating the association between underweight status and migraine as well as the pooled (i.e., overall) OR and CI for these studies when (A) unadjusted, (B) adjusted for age and sex, and (C) multivariate adjusted for age (reference 6 did not include age in multivariate adjusted models), sex (when possible sex-stratified results are presented), and additional variables as conducted by the individual studies. See table e-3 for complete list of these variables.

Sensitivity analysis.

When restricting analyses to those studies that used ICHD migraine diagnoses vs self-report, the overall effect size by the pooled estimates did not materially change (figure e-1). In addition, although inferences are limited by the small number of studies that included measured BMI, when restricting analyses to those studies that used self-reported vs measured BMI, the effect sizes remained similar (figure e-2).

DISCUSSION

Individually, both migraine prevalence and the disease risk associated with obesity are greatest in those of reproductive age and attenuate with advancing age.1,15,26–28 In this meta-analysis of 12 studies involving a total of 288,981 individuals, we found that obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and underweight (BMI < 18.5) status are associated with an increased risk of migraine, and that age and sex are important covariates for the increased risk. Although the crude risk of migraine (i.e., when not adjusting for age and sex) was not increased in those with obesity, the combined pooled effect after adjusting for age and sex alone demonstrated a 27% increased risk of migraine in those with obesity, which remained significant after multivariate adjustments. This finding substantiates the data demonstrating an association between obesity and an increased risk of migraine and emphasizes the importance of age and sex as covariates.1 While this increased risk is moderate (being of similar magnitude to the risk associated with ischemic heart disease29,30 and bipolar disorders31), the recognition of this risk is important given that obesity is a potentially modifiable disease risk factor for migraine. Further, it supports the need for research to determine whether interventions to reduce obesity decrease the risk of migraine. Limited data in uncontrolled studies suggest that morbidly obese episodic and chronic migraineurs who undergo bariatric surgery have a reduction in monthly frequency and headache severity 3 to 6 months after surgery.32–35 In addition, although several well-designed aerobic exercise trials have demonstrated efficacy for reducing headache days and pain severity in those with migraine, it remains unclear as to whether this is related to the exercise itself or as a result of weight loss.32

We also found that being underweight (BMI < 18.5) was associated with a small increased risk of migraine. After adjusting for age and sex, the risk of migraine in underweight individuals was increased by 13% and remained significant after multivariate adjustments. While less controversial than the association between migraine and obesity, likely due to the low prevalence of individuals with underweight body composition, a similar finding was reported in only 26,22 of the 12 studies included in the meta-analysis. Taken together with obesity-related migraine risk, this finding supports that both excessive and insufficient adipose tissue is associated with an increased risk of the migraine.

A prior meta-analysis evaluating obesity status and the association with migraine in a total of 247,828 unique individuals similarly reported an increased risk of migraine in individuals with obesity and those who were underweight.36 However, the risk of migraine was somewhat less in those with obesity (14%) and somewhat more in underweight (21%) individuals than we found in the current meta-analysis. While the majority of the articles included in both meta-analyses were similar, several differences are of note. First, we excluded studies that did not use WHO physical status categories for non-Asian populations and those that only utilized BMI as a continuous variable. The prior meta-analysis included individuals from an exclusively Asian population (for which different BMI cutoffs portend similar disease risk compared with non-Asian populations) and populations that did not strictly utilize WHO physical status categories for non-Asian populations. In addition, in the current meta-analysis we excluded populations from overlapping datasets. Finally, wherever possible, we contacted authors for additional data if not presented in the article and thus were able to include large populations that were unable to be fully included in the prior meta-analysis (e.g., second Health Survey of Nord-Trondelag County [HUNT-2], Women's Health Study, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health).3,5,11,12,14

Mechanisms for the association between migraine and body composition are not fully known. Since the mid-1990s, adipose tissue has been increasingly viewed as an endocrine organ that actively secretes a wide range of bioactive signaling molecules that have autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine functions, including adipiocytokines (e.g., adiponectin), proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., interleukin [IL]–6, tumor necrosis factor–α), sex hormones, and others.37 With changes in body composition (increases and decreases), the production and secretion of these molecules from adipocytes changes.

Age and sex differences in the distribution and metabolic function of adipocytes from adipose tissue have also been described and likely contribute to the age and sex differences in the association of obesity and underweight body composition with migraine.1 Human data support that several of these obesity-related signaling molecules are altered in those with migraine at baseline when pain-free (e.g., adiponectin, resistin) and during acute migraine pain (adiponectin, IL-6).32 Further, recent animal data have demonstrated that obesity is associated with both an augmented basal and acute trigeminovascular response to stimulation and may be capable of priming the trigeminovascular system to be responsive to otherwise innocuous stimuli.38,39 Finally, it is also possible other factors such as changes in physical activity, medications, the presence of comorbidities (e.g., depression), or other medical conditions contribute to the relationship between migraine and obesity and underweight status.

There are several limitations of this meta-analysis. Half (n = 6) of the included studies utilized non-ICHD criteria and the self-report of migraine, thus introducing potential recall bias. In addition, over half (n = 8) of the included studies utilized self-report of body mass index to estimate obesity status. Previous research has shown that individuals with migraine are more likely to underestimate their BMI.40

This type of differential misclassification of exposure (i.e., underestimation of BMI) has been reported to bias the measure of association closer to the null. Thus, the reported measures of association may be stronger than presented in the current meta-analysis. Finally, the disease risk of obesity varies across races, with differing BMI categories holding similar disease risk for Asian and non-Asian populations. Although we excluded studies utilizing predominantly or exclusively Asian populations and we categorized obesity status based on the physical status for non-Asian populations, some studies that were included in the current meta-analysis did include a small percentage (<9%) of Asian individuals in their cohorts. Given that the disease risk in Asian populations is increased at lower BMI categories than for non-Asian populations, it is possible that their inclusion may have slightly attenuated our current findings.

There are several strengths of the current meta-analysis. First, we were able to include data from over 288,000 unique individuals. In addition, we utilized uniform and consistent obesity status categories based on the WHO physical status categories for non-Asian populations and found that the migraine risk is not equivalent in overweight (nonsignificant) and obese (significant) individuals vs normal weight. This is consistent with prior research demonstrating that the migraine risk increases with increasing obesity status from normal to overweight to obese.13 It also underscores the importance of using uniform obesity status categories in migraine research. For example, comparing normal weight individuals (BMI18.5–24.9) with the combined group of overweight and obese individuals (including BMI 25–40+) may yield findings that are attenuated or even negative vs when compared with only obese [BMI ≥30] individuals. As such, the sensitivity of the studies can be improved by disaggregating the combined groups into obese and overweight groups. Finally, in cases where studies met all inclusion criteria except for the BMI categories, we attempted to contact authors for additional information and for which all but 2 contacted authors responded. Most notably, this allowed us to include data from the HUNT-2 study, which utilized both ICHD migraine criteria to categorize migraine and measured height and weight for BMI.

The current study substantiates that obesity and underweight status are associated with an increased risk of migraine, and that age and sex are important covariates of this association. These data suggest that clinicians treating migraine patients should be aware of this association. Further research to better understand the mechanisms underlying this association has the potential to advance our understanding of migraine and lead to the development of targeted therapeutic strategies based on obesity status.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the study authors who provided additional data on their studies, including Drs. Berger, Fitgerald, Holder, Kurth, Qiu, Rist, Rosso, Williams, Winsvold, and Winter.

GLOSSARY

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- HUNT-2

second Health Survey of Nord-Trondelag County

- ICHD

International Classification of Headache Disorders

- IL

interleukin

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- OR

odds ratio

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Bizu Gelaye: manuscript design, primary authorship of manuscript, data analysis, data interpretation, approval of final manuscript. Simona Sacco: data interpretation, revision of manuscript for intellectual content, approval of final manuscript. Wendy J. Brown: data interpretation, revision of manuscript for intellectual content, approval of final manuscript. Haley Nitchie: data interpretation, revision of manuscript for intellectual content, approval of final manuscript. Raffaele Ornello: data interpretation, revision of manuscript for intellectual content, approval of final manuscript. B. Lee Peterlin: manuscript conception and design, authorship of manuscript, data interpretation, revision of manuscript for intellectual content, approval of final manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURE

B. Gelaye has consulted for Egalet Corporation for a project unrelated to the current manuscript. S. Sacco, W. Brown, H. Nitchie, and R. Ornello report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. B. Peterlin: funding by NIH/NINDS (grant #K23-NS078345); serves on the editorial boards for Neurology® and as an associate editor for Headache. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chai NC, Scher AI, Moghekar A, Bond DS, Peterlin BL. Obesity and headache: part I: a systematic review of the epidemiology of obesity and headache. Headache 2014;54:219–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilmore J. Body mass index and health [in English, French]. Health Rep 1999;11:31–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown WJ, Mishra G, Kenardy J, Dobson A. Relationships between body mass index and well-being in young Australian women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000;24:1360–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans RW, Williams MA, Rapoport AM, Peterlin BL. The association of obesity with episodic and chronic migraine. Headache 2012;52:663–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winsvold BS, Hagen K, Aamodt AH, Stovner LJ, Holmen J, Zwart JA. Headache, migraine and cardiovascular risk factors: the HUNT study. Eur J Neurol 2011;18:504–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bigal ME, Liberman JN, Lipton RB. Obesity and migraine: a population study. Neurology 2006;66:545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford ES, Li C, Pearson WS, Zhao G, Strine TW, Mokdad AH. Body mass index and headaches: findings from a national sample of US adults. Cephalalgia 2008;28:1270–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robberstad L, Dyb G, Hagen K, Stovner LJ, Holmen TL, Zwart JA. An unfavorable lifestyle and recurrent headaches among adolescents: the HUNT study. Neurology 2010;75:712–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vo M, Ainalem A, Qiu C, Peterlin BL, Aurora SK, Williams MA. Body mass index and adult weight gain among reproductive age women with migraine. Headache 2011;51:559–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattsson P. Migraine headache and obesity in women aged 40–74 years: a population-based study. Cephalalgia 2007;27:877–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winter AC, Wang L, Buring JE, Sesso HD, Kurth T. Migraine, weight gain and the risk of becoming overweight and obese: a prospective cohort study. Cephalalgia 2012;32:963–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winter AC, Berger K, Buring JE, Kurth T. Body mass index, migraine, migraine frequency and migraine features in women. Cephalalgia 2009;29:269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterlin BL, Rosso AL, Williams MA, et al. Episodic migraine and obesity and the influence of age, race, and sex. Neurology 2013;81:1314–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterlin BL, Rosso AL, Rapoport AM, Scher AI. Obesity and migraine: the effect of age, gender and adipose tissue distribution. Headache 2010;50:52–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry: report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1995;854:1–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting: Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available at: ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed January 17, 2017.

- 18.Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med 2015;8:2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:25. 2288-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bax L, Yu LM, Ikeda N, Moons KG. A systematic comparison of software dedicated to meta-analysis of causal studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le H, Tfelt-Hansen P, Skytthe A, Kyvik KO, Olesen J. Association between migraine, lifestyle and socioeconomic factors: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Headache Pain 2011;12:157–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winter AC, Hoffmann W, Meisinger C, et al. Association between lifestyle factors and headache. J Headache Pain 2011;12:147–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frederick IO, Qiu C, Enquobahrie DA, et al. Lifetime prevalence and correlates of migraine among women in a Pacific Northwest pregnancy cohort study. Headache 2014;54:675–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos IS, Goulart AC, Passos VM, Molina Mdel C, Lotufo PA, Bensenor IM. Obesity, abdominal obesity and migraine: a cross-sectional analysis of ELSA-Brasil baseline data. Cephalalgia 2015;35:426–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Itallie TB, Lew EA. Health implications of overweight in the elderly. Prog Clin Biol Res 1990;326:89–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niedziela J, Hudzik B, Niedziela N, et al. The obesity paradox in acute coronary syndrome: a meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:801–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andersen KK, Olsen TS. The obesity paradox in stroke: lower mortality and lower risk of readmission for recurrent stroke in obese stroke patients. Int J Stroke 2015;10:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sacco S, Ornello R, Ripa P, et al. Migraine and risk of ischaemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Neurol 2015;22:1001–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurth T, Winter AC, Eliassen AH, et al. Migraine and risk of cardiovascular disease in women: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2016;353:i2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minen MT, Begasse De Dhaem O, Kroon Van Diest A, et al. Migraine and its psychiatric comorbidities. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87:741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chai NC, Bond DS, Moghekar A, Scher AI, Peterlin BL. Obesity and headache: part II–potential mechanism and treatment considerations. Headache 2014;54:459–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bond DS, Vithiananthan S, Nash JM, Thomas JG, Wing RR. Improvement of migraine headaches in severely obese patients after bariatric surgery. Neurology 2011;76:1135–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novack V, Fuchs L, Lantsberg L, et al. Changes in headache frequency in premenopausal obese women with migraine after bariatric surgery: a case series. Cephalalgia 2011;31:1336–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gunay Y, Jamal M, Capper A, Eid A, Heitshusen D, Samuel I. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass achieves substantial resolution of migraine headache in the severely obese: 9-year experience in 81 patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013;9:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ornello R, Ripa P, Pistoia F, et al. Migraine and body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Headache Pain 2015;16:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterlin BL, Rapoport AM, Kurth T. Migraine and obesity: epidemiology, mechanisms, and implications. Headache 2010;50:631–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rossi HL, Lara O, Recober A. Female sex and obesity increase photophobic behavior in mice. Neuroscience 2016;331:99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marics B, Peitl B, Varga A, et al. Diet-induced obesity alters dural CGRP release and potentiates TRPA1-mediated trigeminovascular responses. Cephalalgia Epub 2016 Jun 14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Katsnelson MJ, Peterlin BL, Rosso AL, Alexander GM, Erwin KL. Self-reported vs measured body mass indices in migraineurs. Headache 2009;49:663–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]