Abstract

Implementation studies are often poorly reported and indexed, reducing their potential to inform initiatives to improve healthcare services. The Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) initiative aimed to develop guidelines for transparent and accurate reporting of implementation studies. Informed by the findings of a systematic review and a consensus-building e-Delphi exercise, an international working group of implementation science experts discussed and agreed the StaRI Checklist comprising 27 items. It prompts researchers to describe both the implementation strategy (techniques used to promote implementation of an underused evidence-based intervention) and the effectiveness of the intervention that was being implemented. An accompanying Explanation and Elaboration document (published in BMJ Open, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013318) details each of the items, explains the rationale, and provides examples of good reporting practice. Adoption of StaRI will improve the reporting of implementation studies, potentially facilitating translation of research into practice and improving the health of individuals and populations.

Summary box

Underpinning the 27 item StaRI Checklist is the concept of dual strands describing (a) the strategies used to promote implementation and (b) the intervention being implemented

The expectation is that the authors will clarify both (a) how they anticipate that the strategies employed are likely to promote implementation and (b) explain the underpinning premise of why implementation of the intervention may be expected to improve healthcare or health outcomes

Unlike most reporting standards that apply to a specific research methodology, the StaRI Statement and accompanying Checklist refers to the broad range of study designs employed in implementation science

The requirement for extensive description of context, implementation strategies, and interventions, as well as reporting a broad range of effectiveness, process, and health economic outcomes, will challenge journals operating strict word limits for research papers and may require (innovative) solutions and use of supplementary online materials

Globally, healthcare systems are struggling to deliver the benefits of research to their populations.1 w1-w3 Increasingly, it is recognised that translation from “bench to bedside to community”w4 is often ineffective and inefficient. The scientific community needs to focus on how effective interventions are disseminated and implemented across the spectrum of contexts and settings in order to improve individual and population health.w5 Against this background, implementation science has emerged as an important discipline for developing the evidence base on how to translate research findings into routine care.1 2 3 4

Implementation studies are, however, often poorly reported and indexed, making it difficult to find, reproduce, or synthesise the evidence from relevant studies.5 More specific criticisms include poor (or absent) descriptions of conceptual frameworks underpinning the research,5 6 inadequate description of context, and incomplete information about how the intervention was promoted and implemented (or not) in the different settings.6 w6 w7 Similar concerns with, for example, the reporting of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) led to the introduction of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist,w8 with evidence of subsequent improvement in reporting standards.w9-w11 There have been calls for the development of similar standards for transparent and accurate reporting of implementation studies.5 6 7 The Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) initiative aimed to address this need.

Scope and relationship with other reporting standards

Implementation science encompasses a broad range of methodologies applicable to improving the dissemination, implementation, and scaling up of effective behavioural, clinical, healthcare, public health, global health, and educational interventions8 (or discontinuation of ineffective or harmful practicesw12) with a view to improving quality of care and health outcomes. Although this document is set within the context of healthcare and population health, there are parallels in other domains (such as educational initiatives).9 w13 The StaRI Statement and Checklist may thus have resonance outside healthcare.

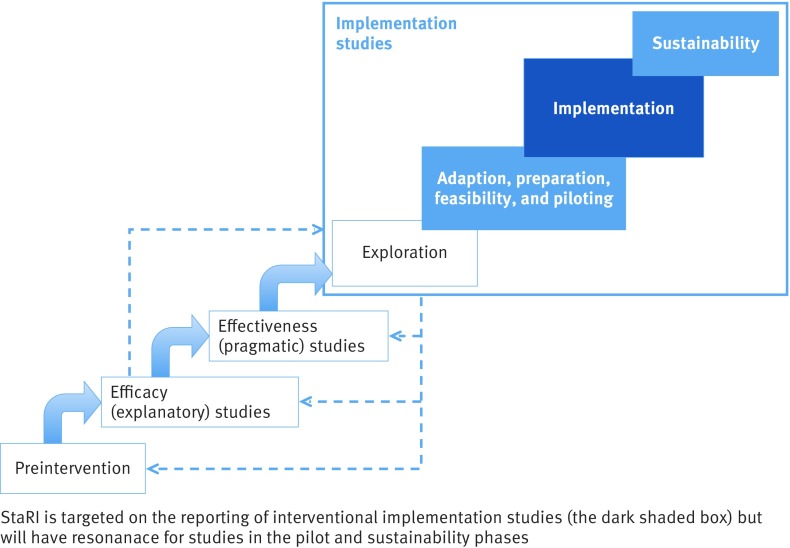

Understanding of the position that implementation studies hold in the science of developing, evaluating, disseminating, and implementing healthcare interventions has been evolving over recent years. The UK Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework for Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions10 emphasises the need to disseminate and implement findings of complex interventions trials but offers no advice on how to achieve this. PRECIS-2 conceives trial design on an “explanatory-pragmatic” spectrum11 but does not project beyond pragmatic trials to implementation in routine practice. Neither of these frameworks addresses the need for research to explore how interventions shown to be effective in trials require adaptation if they are to align with the routines of practice and be successfully implemented into “usual care” settings.12 w14-w17 Implementation science undertakes studies that explore healthcare contexts, develop and evaluate strategies for implementing effective interventions that address local realities, can be implemented at scale and are potentially sustainable.2 w18 Proposed frameworks have added an “implementation cycle” to complement the MRC’s complex intervention cycle,13 or extended a linear spectrum (see fig 1).7 14 Others have emphasised the potential overlap between effectiveness and implementation research and described “hybrid” designs.15

Fig 1 Positioning of implementation studies and the focus of StaRI reporting standards (adapted from fig 12.1. in Brownson et al8)

The StaRI Statement and Checklist are intended to improve reporting of implementation studies, employing a range of study designs to develop and evaluate implementation strategies with the aim of enhancing adoption and sustainability of effective interventions.16 Implementation studies may be distinguished from quality improvement reports that describe system level initiatives, typically in the context of a specific problem within a specific healthcare system,16 w19 and the World Health Organisation guidelines, which focus on improving reporting of their fieldwork.w20

Methods

We followed the methodology described in the Developing Health Research Reporting Guidelines.w21 Our full protocol is available on the EQUATOR website.w22 After a systematic literature review, we recruited international multidisciplinary experts (including healthcare researchers, journal editors, healthcare professionals and managers, methodologists, guideline developers, patient organisations, and funding bodies) to participate in an e-Delphi exercise.17 Of 66 experts approached, 23 contributed suggestions for the Checklist, 20 completed the first scoring round, and 19 completed the second scoring round. Of 47 potential items, 35 reached the a priori level of consensus for inclusion—that is, 80% agreement with priority scores 7, 8, or 9—and 19 items achieved 100% agreement. All these items, with their final priority scores, were taken forward as candidate items for inclusion in the StaRI Checklist.

In April 2015, we convened a two-day consensus working group in London attended by 15 international delegates (UK or Europe=11, US or Canada=4) drawn from multiple disciplines. Delegates included healthcare researchers (n=9), journal editors (n=6), healthcare professionals (n=8) and managers (n=1), methodologists (n=4), guideline developers (n=2), and funding bodies (n=2) (several participants had more than one role). This group discussed the candidate items and agreed the first draft of the StaRI Checklist. The discussions were informed by the outcome of the e-Delphi exercise (see appendix 1 for the e-Delphi results as provided to the workshop delegates), but items were also considered in the context of other published reporting standards and the wider literature, and the working group’s expertise in implementation science. After general discussion on key defining concepts (informed by points raised in the e-Delphi17), each candidate item was considered in turn. Agreement was reached by discussion rather than by consensus scoring. The initial draft statement and documents were subsequently developed iteratively by email discussion.

Constructive feedback on a penultimate draft of the StaRI Statement from colleagues working internationally in the field of implementation science, healthcare researchers, clinicians, and patients was used to help shape the final version of the paper. In addition, we presented the concepts to and sought feedback from several workshops, conference discussions, and implementation project steering groups.

Defining concepts

There are two defining concepts underpinning the StaRI Statement and Checklist. The first is the dual strands of describing, on the one hand, the implementation strategy and, on the other, the clinical, healthcare, global health, or public health intervention being implemented.3 w23 For example, an implementation strategy (staff training, changes to invitation letters and appointment systems, development of computer templates, ongoing audit, etc) might support an intervention (such as offering the option of telephone consultations) with the aim of improving access to routine asthma care.w24 These strands are represented as two columns in the Checklist (see table 1). The primary focus of implementation science is the implementation strategy,w25 and the expectation is that the items in column 1 will always be fully completed with details of how the intervention was implemented and the impact measured as an implementation outcome. The second strand (column 2) expects authors to complete items about the impact of the intervention on the health of the target population. This may be measured as a health outcome, or it may be more appropriate to cite robust evidence to support known beneficial effects of the intervention on health of individuals or populations (such as reducing smoking prevalence). Even when evidence is strong, the possibility that the impact of an intervention may be attenuated when it is implemented in routine practice needs to be considered. Although all items are worthy of consideration, not all items will be applicable to, or feasible in, every study; a fully completed StaRI Checklist may thus include a number of “not applicable” items.

Table 1.

Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies: the StaRI Checklist of items to be reported

| Checklist item | Implementation strategy | Intervention† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | 1 | Identification as an implementation study, and description of the methodology in the title and/or keywords | |

| Abstract | 2 | Identification as an implementation study, including a description of the implementation strategy to be tested, the evidence-based intervention being implemented, and defining the key implementation and health outcomes | |

| Introduction | 3 | Description of the problem, challenge, or deficiency in healthcare or public health that the intervention being implemented aims to address | |

| 4 | The scientific background and rationale for the implementation strategy (including any underpinning theory, framework, or model, how it is expected to achieve its effects, and any pilot work) | The scientific background and rationale for the intervention being implemented (including evidence about its effectiveness and how it is expected to achieve its effects) | |

| Aims and objectives | 5 | The aims of the study, differentiating between implementation objectives and any intervention objectives | |

| Methods: description | 6 | The design and key features of the evaluation (cross referencing to any appropriate methodology reporting standards) and any changes to study protocol, with reasons | |

| 7 | The context in which the intervention was implemented (consider social, economic, policy, healthcare, organisational barriers and facilitators that might influence implementation elsewhere) | ||

| 8 | The characteristics of the targeted “site(s)” (locations, personnel, resources, etc) for implementation and any eligibility criteria | The population targeted by the intervention and any eligibility criteria | |

| 9 | A description of the implementation strategy | A description of the intervention | |

| 10 | Any subgroups recruited for additional research tasks, and/or nested studies are described | ||

| Methods: evaluation | 11 | Defined pre-specified primary and other outcome(s) of the implementation strategy, and how they were assessed. Document any pre-determined targets | Defined pre-specified primary and other outcome(s) of the intervention (if assessed), and how they were assessed. Document any pre-determined targets |

| 12 | Process evaluation objectives and outcomes related to the mechanism(s) through which the strategy is expected to work | ||

| 13 | Methods for resource use, costs, economic outcomes, and analysis for the implementation strategy | Methods for resource use, costs, economic outcomes, and analysis for the intervention | |

| 14 | Rationale for sample sizes (including sample size calculations, budgetary constraints, practical considerations, data saturation, as appropriate) | ||

| 15 | Methods of analysis (with reasons for that choice) | ||

| 16 | Any a priori subgroup analyses (such as between different sites in a multicentre study, different clinical or demographic populations) and subgroups recruited to specific nested research tasks | ||

| Results | 17 | Proportion recruited and characteristics of the recipient population for the implementation strategy | Proportion recruited and characteristics (if appropriate) of the recipient population for the intervention |

| 18 | Primary and other outcome(s) of the implementation strategy | Primary and other outcome(s) of the intervention (if assessed) | |

| 19 | Process data related to the implementation strategy mapped to the mechanism by which the strategy is expected to work | ||

| 20 | Resource use, costs, economic outcomes, and analysis for the implementation strategy | Resource use, costs, economic outcomes, and analysis for the intervention | |

| 21 | Representativeness and outcomes of subgroups including those recruited to specific research tasks | ||

| 22 | Fidelity to implementation strategy as planned and adaptation to suit context and preferences | Fidelity to delivering the core components of intervention (where measured) | |

| 23 | Contextual changes (if any) which may have affected outcomes | ||

| 24 | All important harms or unintended effects in each group | ||

| Discussion | 25 | Summary of findings, strengths and limitations, comparisons with other studies, conclusions and implications | |

| 26 | Discussion of policy, practice and/or research implications of the implementation strategy (specifically including scalability) | Discussion of policy, practice and/or research implications of the intervention (specifically including sustainability) | |

| General | 27 | Include statement(s) on regulatory approvals (including, as appropriate, ethical approval, confidential use of routine data, governance approval), trial or study registration (availability of protocol), funding, and conflicts of interest | |

*Implementation strategy refers to how the intervention was implemented.

†Intervention refers to the healthcare or public health intervention that is being implemented.

Note: A key concept is the dual strands of describing (a) the implementation strategy and (b) the clinical, healthcare, or public health intervention that is being implemented. These strands are represented as two columns in the checklist. The primary focus of implementation science is the implementation strategy (column 1) and the expectation is that this will always be completed. The evidence about the impact of the intervention on the targeted population should always be considered (column 2) and either health outcomes reported or robust evidence cited to support a known beneficial effect of the intervention on the health of individuals or populations. While all items are worthy of consideration, not all items will be applicable to or feasible within every study.

The second concept is that, unlike most reporting standards that apply to a specific research methodology, StaRI applies to the broad range of research methodologies employed in implementation science (for example, cluster RCTs, controlled clinical trials, interrupted time series, cohort, case study, before and after studies, as well as mixed methods for quantitative or qualitative assessments).3 Authors are referred to other reporting standards for advice on reporting specific methodological features—for example, randomisation in cluster RCTs,w26 matching criteria in cohort studies,w27 or addressing reflexivity in qualitative research.w28

The StaRI Checklist

The StaRI Checklist comprises 27 items, of which 10 items expect authors to consider the dual strands of the implementation strategy and the intervention (see table 1). Details about each of the Checklist items is provided in the accompanying Explanation and Elaboration document published in BMJ Open.18 Appendix 2 is a version of the Checklist for completion by authors submitting an implementation paper. It is strongly recommended that authors using the StaRI Checklist read the detailed document that explains the rationale for each item and provides examples of good practice.

Three overarching components are emphasised in the Checklist:

The expectation is that authors have an explicit hypothesis (we use the term “logic pathway”) that spans both how the implementation strategy is expected to work and the mechanism by which the intervention is expected to improve healthcare (see Explanation and Elaboration document18 for a table of alternative terminologies and a link to a detailed description of “logic models”). This logic pathway should reflect the rationale presented in the introduction, determine the approach to implementation, dictate implementation, health, and process outcomes, and provide insights into why and how the implementation strategy and intervention worked (or not).

The balance between fidelity to, and adaptation of, the implementation strategy and intervention is of particular interest in implementation science. Fidelity refers to the degree of adherence to the described implementation strategy and intervention; adaptation is the degree to which users modify the strategy and intervention during implementation to suit the local needs (see table 2 for further description and examples). Insufficient fidelity to the “active ingredients” of an intervention may dilute effectiveness,w29 whereas insufficient adaptation or tailoring to local context may inhibit effective implementation.19 An approach to reporting these apparently contradictory concepts is to define the core components of an intervention (ideally related to the logic pathway) to which fidelity is expected, and those aspects that may be adapted by local sites to aid implementation.19 w30

Successful implementation of an intervention into practice is a planned, facilitated process involving the interplay between individuals, intervention or new ways of working, and context to promote evidence-informed practice.20 A rich description of the context is critical to enable the reader to assess the external validity of the reported study,w18 and to decide how the context in the study compares to their situation and whether the implementation strategy can be directly transposed or will need adapting.w31 Similarly, social, political, and economic context influence the “entrenched practices” that hinder evidence-based de-implementation of unproven practices or interventions.w12 w32

Table 2.

Terminology: definitions and illustration

| Terminology | Definition | Illustration using a study implementing supported self management for asthma |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation science | The scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of evidence-based interventions into practice and policy and hence improve health4 | Improving implementation in routine practice of evidence-based supported self management for asthma |

| Implementation strategy | Methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of an under-utilised intervention15 w26 | A programme of professional training, templates for reviews, access to resources, facilitation, audit, and feedback |

| Intervention | The evidence-based practice, programme, policy, process, or guideline recommendation that is being implemented8 | Provision of asthma self management in routine asthma reviews, including completion of action plans |

| Implementation outcome | Process or quality measure to assess the impact of the implementation strategyw24 | Proportion of people with asthma who have an action plan |

| Health outcome | Patient-level health outcomes for a clinical intervention, such as symptoms or mortality; or population-level health status or indices of system function for a system/ organisational-level intervention15 | Proportion of people with asthma requiring unscheduled care for asthma or patient reported asthma control |

| Logic pathway | The way(s) in which the implementation strategy and intervention are hypothesised to operate | An organisation that prioritises self management encourages or enables trained professionals to provide asthma action plans; self management improves asthma outcomes |

| Fidelity | The degree of adherence to the described implementation strategy and/or the degree to which an intervention is implemented as prescribed in the original protocolw29 | Uptake of professional training, utilisation of review templates (implementation fidelity), and assessment of adequacy of education and completion of action plans (intervention fidelity) |

| Adaptation | The degree to which the strategy and intervention are modified by users during implementation to suit local needs19 | Use (or not) of telehealth to deliver reviews or provide action plans. Different professionals (doctors, nurses, pharmacists) with primary responsibility for self management education |

Discussion

Implementation science is an emerging and rapidly evolving field. The StaRI Statement and Checklist should therefore be seen as an evolving document, and potentially a catalyst for discussing and defining how implementation studies are conceived, planned, and reported.5

We hope that the concept of dual strands will resonate with researchers designing and reporting implementation science studies. We appreciate that the distinction will not always be as unambiguous as it seems in the StaRI checklist, but we suggest that considering the design and evaluation of implementation studies in these two strands is helpful and aids clarity of study design and reporting. We also recognise that not all studies will measure health outcomes, though consideration of the ultimate goal of improving health through implementing an evidence-based intervention would seem a reasonable requirement. Feedback on this underpinning concept will be valuable for future iterations of the StaRI Statement and Checklist.

There are two practical challenges for the application of StaRI that warrant discussion. First, implementation science uses diverse methodologies that need to be accommodated in the reporting standards. One option is to incorporate relevant items from other checklists, but this may be perceived as limiting the methodological options. StaRI therefore advises authors to consult methodological checklists for reporting design-specific aspects of their chosen study design. By doing this, we have implicitly prioritised the concept underpinning implementation studies, though this should not be interpreted as undermining the rigour of reporting the chosen study design.

The second challenge is the requirement for extensive description of context, implementation strategies, and interventions as well as reporting a broad range of primary effectiveness, process, health, economic, and implementation outcomes.w25 This requirement will stimulate debate about word counts, supplementary material, and additional publications in order to accommodate journal requirements, author needs, and reader preferences. This tension is further discussed in the Explanation and Elaboration document,18 and some practical approaches are suggested for summarising information in tables or figures. We look forward to learning how authors and journals work with these challenges and the (innovative) solutions that they adopt (such as appendices, supplementary online files, and additional publications).

Conclusion

The StaRI Statement is registered with the EQUATOR Network (www.equator-network.org), and the Checklist (for completion by authors) is freely available from bmj.com (appendix 2). We invite editors of all journals publishing implementation research to consider requiring submission of a StaRI Checklist, and authors reporting their implementation studies to use the Checklist. In the future we would like to work with authors as they apply the Checklist to their papers, “road testing” the standards and enabling iterative development.

Previously published reporting guidelines have been instrumental in improving reporting standards,6 w8-w10 and our hope is that StaRI will achieve a similar improvement in the reporting of implementation strategies that will facilitate translation of effective interventions into routine practice, ultimately to benefit the health of individuals and populations.

Linked information

StaRI website. www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/stari-statement/

Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research (EQUATOR). www.equator-network.org/

Consolidated Framework For Implementation Research (CFIR). www.cfirguide.org/imp.html

Logic models. www.wkkf.org/resource-directory/resource/2006/02/wk-kellogg-foundation-logic-model-development-guide

Dissemination and implementation models in Health Research and Practice. www.dissemination-implementation.org/index.aspx

Process evaluation of complex interventions. www.ioe.ac.uk/MRC_PHSRN_Process_evaluation_guidance_final(2).pdf

Reach Effectiveness Adoption Implementation Maintenance (RE-AIM). www.re-aim.hnfe.vt.edu

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1: e-Delphi results as provided to the workshop delegates

Appendix 2: Version of StaRI Checklist for completion by authors submitting an implementation paper

Supplementary references w1–w32

Members of the the StaRI Group are: Melanie Barwick, Chris Carpenter, Peter Craig, Sandra Eldridge, Eleni Epiphaniou, Gonzalo Grandes Odriozola, Chris Griffiths, Martin Gulliford, Jo Rycroft-Malone, Paul Meissner, Brian Mittman, Elizabeth Murray, Anita Patel, Gemma Pearce, Hilary Pinnock, Aziz Sheikh, and Steph Taylor.

Members of the PRISMS team (Eleni Epiphaniou, Gemma Pearce, and Hannah Parke) supported the underpinning literature work, and the e-Delphi exercise was handled by ClinVivo. We thank colleagues (implementation science experts, healthcare researchers, clinicians, PhD students) who reviewed the penultimate draft of the StaRI statement and provided a reality check and constructive feedback: Helen Ashdown, David Chambers, Louise Craig, Clarisse Dibao-Dina, Peter Hanlon, Roger Jones, Rachel Jordan, Chris del Mar, Brian McKinstry, Susan Morrow, John Ovretveit, David Price, Kamran Siddiqui, Rafael Stelmach, Paul Stephenson, Shaun Treweek, Bryan Weiner. We also thank Melissa Goodbourn and Allison Worth, who arranged feedback from the Edinburgh Clinical Research Facility Patient Advisory Panel (Stephanie Ashby, Alison Williams), and Steven Towndrow who coordinated feedback from the Patient and Public Involvement representatives of the NIHR CLAHRC North Thames (Ben Wills-Eve, Rahila Bashir, Julian Ashton, Colleen Ewart, Karen Williams).

Contributors: HP initiated the idea for the study and with ST led the development of the protocol, securing of funding, study administration, workshop, and writing of the paper. AS, CG, and SE advised on the development of the protocol and data analysis. All authors participated in the StaRI international working group along with GP, BM, MG. HP wrote the initial draft of the paper, to which all the authors contributed. HP is the study guarantor.

Funding: The StaRI initiative and workshop were funded by contributions from the Asthma UK Centre for Applied Research (AC-2012-01); Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates (PCRCA_08_01); the Centre for Primary Care and Public Health, Queen Mary University of London; and with contributions in kind from the PRISMS team (NIHR HS&DR Grant 11/1014/04). ST was (in part) supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) North Thames at Bart’s Health NHS Trust. AS is supported by the Farr Institute. The funding bodies had no role in the design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: research grants from Chief Scientist Office (HP), Asthma UK (AS, HP, ST), Farr Institute (AS), NIHR HS&DR (HP, ST), NIHR CLAHRC (ST) for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; CC is deputy editor-in-chief for Academic Emergency Medicine and on the editorial boards for the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society and Annals of Internal Medicine's ACP Journal Club and serves as paid faculty for Emergency Medical Abstracts, JR-M is director of the NIHR HS&DR Programme, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Disclaimers: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Provenance of the paper: The StaRI Checklist was informed by the findings of a literature review and an e-Delphi exercise, an international consensus workshop, and the subsequent email correspondence among members of the StaRI Group. The international authors contributed expertise on clinical practice, public health, knowledge exchange, implementation science, complex interventions, and a range of methodologies including quantitative and qualitative evaluations.

References

- 1.Chalkidou K, Anderson G. Comparative Effectiveness Research: International Experiences and Implications for the United States . www.nihcm.org/pdf/CER_International_Experience_09.pdf.

- 2.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 pmid:19664226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters DH, Adam T, Alonge O, Agyepong IA, Tran N. Implementation research: what it is and how to do it. BMJ 2013;347:f6753.pmid:24259324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foy R, Sales A, Wensing M, et al. Implementation science: a reappraisal of our journal mission and scope. Implement Sci 2015;10:51 10.1186/s13012-015-0240-2 pmid:25928695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, Pearce G, et al. Implementing supported self-management for asthma: a systematic review and suggested hierarchy of evidence of implementation studies. BMC Med 2015;13:127 10.1186/s12916-015-0361-0 pmid:26032941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rycroft-Malone J, Burton CR. Is it time for standards for reporting on research about implementation?Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2011;8:189-90. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00232.x pmid:22123028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neta G, Glasgow RE, Carpenter CR, et al. A Framework for Enhancing the Value of Research for Dissemination and Implementation. Am J Public Health 2015;105:49-57. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302206 pmid:25393182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, eds. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science into practice.Oxford University Press, 2012. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199751877.001.0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barwick M, Barac R, Akrong LM, Johnson S, Chaban P. Bringing evidence to the classroom: exploring educator notions of evidence and preferences for practice change. Int J Educ Res 2014;2:1-15 10.12735/ier.v2i4p01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. MRC, 2008. mrc.ac.uk/complexinterventionsguidance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ 2015;350:h2147 10.1136/bmj.h2147 pmid:25956159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 2004;82:581-629. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x pmid:15595944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, Taylor SJC. Phase IV implementation studies. The forgotten finale to the complex intervention methodology framework. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11(Suppl 2):S118-22. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201308-259RM pmid:24559024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lansdverk J, Brown CH, Chamberlain P, et al. Chapter 12: Design and analysis in dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, eds. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science into practice. Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012;50:217-26. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 pmid:22310560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol 2015;3:32 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9 pmid:26376626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, Sheikh A, et al. Developing standards for reporting implementation studies of complex interventions (StaRI): a systematic review and e-Delphi. Implement Sci 2015;10:42 10.1186/s13012-015-0235-z pmid:25888928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. for the StaRI Group. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI): Explanation and Elaboration document. BMJ Open 2017. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: how “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be?BMJ 2004;328:1561-3. 10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1561 pmid:15217878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Chandler J, et al. The role of evidence, context, and facilitation in an implementation trial: implications for the development of the PARIHS framework. Implement Sci 2013;8:28 10.1186/1748-5908-8-28 pmid:23497438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: e-Delphi results as provided to the workshop delegates

Appendix 2: Version of StaRI Checklist for completion by authors submitting an implementation paper

Supplementary references w1–w32