Abstract

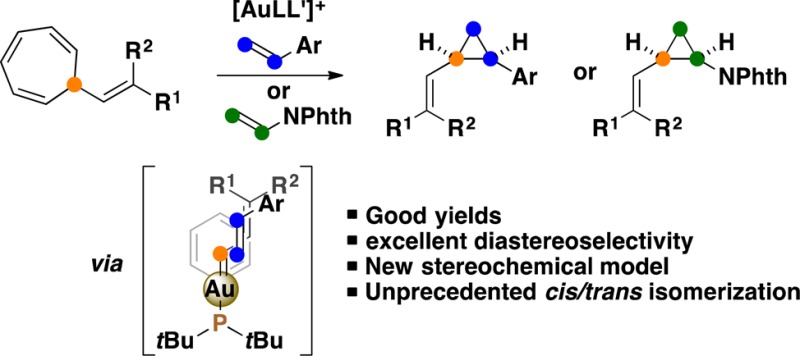

A highly stereoselective gold(I)-catalyzed cis-vinylcyclopropanation of alkenes has been developed. Allylic gold carbenes, generated via a retro-Buchner reaction of 7-alkenyl-1,3,5-cycloheptatrienes, react with alkenes to form vinylcyclopropanes. The gold(I)-catalyzed retro-Buchner reaction of these substrates proceeds by simple heating at a temperature much lower than that required for the reaction of 7-aryl-1,3,5-cycloheptatrienes (75 °C vs 120 °C). A newly developed Julia–Kocienski reagent enables the synthesis of the required cycloheptatriene derivatives in one step from readily available aldehydes or ketones. On the basis of mechanistic investigations, a stereochemical model for the cis selectivity was proposed. An unprecedented gold-catalyzed isomerization of cis- to trans-cyclopropanes has also been discovered and studied by DFT calculations.

Keywords: cyclopropanation, vinylcyclopropanes, gold catalysis, retro-Buchner reaction, cycloheptatrienes

Introduction

Vinylcyclopropanes are common motifs in natural products1 and active pharmaceuticals.2 Moreover, vinylcyclopropanes are of particular interest as synthetic intermediates3 because of their rich downstream chemistry, undergoing rearrangements to cyclopentenes,4 (3 + n) and (5 + n) cycloadditions,5 or other transition-metal-catalyzed transformations,6 providing ready access to molecular complexity.

Methods for the stereoselective cyclopropanation of alkenes by formal carbene transfer usually require directing groups and rely on the use of organometallic reagents or diazoalkanes,7−9 which are hydrolytically unstable, pyrophoric, or potentially explosive. Recent efforts have led to the development of safer ways to access metal carbenes from stable precursors.10 Thus, among others, metal carbenes or carbenoids have been generated from α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds,11 tosyl hydrazones,12 triazoles,13 cyclopropenes,14 and propargyl ethers15 or esters,16 as well as from alkynes by oxidative processes.17 However, highly stereoselective methods for the synthesis of vinylcyclopropanes that do not rely on the use of diazo reagents remain scarce.18 In general, diastereopure vinylcyclopropanes are accessed in a stepwise manner through derivatization of functionalized cyclopropane building blocks, by either Wittig olefination19 or metal-catalyzed cross-couplings.20,21

Metal-catalyzed reactions of styryldiazoacetates efficiently give rise to 1-styrylcyclopropane-1-carboxylates.22−24 However, the synthesis of simple vinylcyclopropanes not bearing ester groups requires the use of alkenyldiazomethanes, which are much less stable since they can easily give rise to pyrazoles25,26 or undergo dimerization to form trienes.27 This instability has been partially circumvented by performing the cyclopropanation under metal-free conditions with flow-generated alkenyldiazalkanes.28

We recently discovered that highly electrophilic gold(I) complexes are able to cleave two-carbon bonds of norcaradienes, which are in equilibrium with more stable cycloheptatrienes,29 to form in situ gold(I) carbenes.30−32 Starting from readily available 7-aryl substituted cycloheptatrienes, the retrocyclopropanation (decarbenation) reaction leads to aryl-substituted gold(I) carbenes, which undergo cyclopropanation with alkenes,30b intramolecular Friedel–Crafts-type reactions,30c and [4 + 1] cycloadditions with methylenecyclopropanes or cyclobutenes.30d In contrast to aryl derivatives, 7-alkynyl-1,3,5-cycloheptatrienes undergo cycloisomerization reactions at low temperature with gold(I) or gold(III) catalysts to give indenes via stabilized barbaralyl cations.33,34

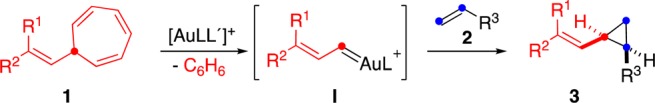

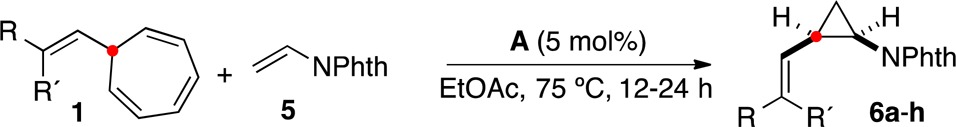

The gold(I)-catalyzed retro-Buchner reaction requires relatively high temperatures (ca. 120 °C) for the efficient cleavage of the cyclopropane ring of norcaradienes,30b,30c,30d which results in low stereoselectivity in the subsequent trapping of the generated aryl-substituted gold(I) carbenes with alkenes.30b We envisaged that the retro-Buchner reaction of 7-alkenyl-1,3,5-cycloheptatrienes 1 would take place with gold(I) under milder conditions to form more stabilized α,β-unsaturated gold(I) carbenes I,35 which could react with alkenes 2 to give rise to vinylcyclopropanes 3 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Vinylcyclopropanation via Retro-Buchner Reaction of Alkenylcycloheptatrienes 1.

Here, we report the scope of this gold(I)-catalyzed vinylcyclopropanation that proceeds at moderate temperatures and for the first time allows preparing vinylcyclopropanes 3 with very good cis stereoselectivities. In contrast to the case for alkenyldiazomethanes, the required alkenylcycloheptatrienes 1 are perfectly stable compounds that can be obtained from commercially available tropylium salts or by a new procedure based on the Julia–Kocienski reaction. We have also found that cis-configured cyclopropanes can undergo isomerization to form trans-cyclopropanes by a reversible carbon–carbon bond cleavage promoted by gold(I).

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of New Alkenylcycloheptatrienes

Alkenylcycloheptatrienes 1 can be obtained by the reaction of alkenyllithium or Grignard reagents with tropylium salts.30b,36 In addition, we have found that alkenyl trifluoroborates can also be used as softer nucleophiles, which allow performing the addition reaction at room temperature in DMF.37

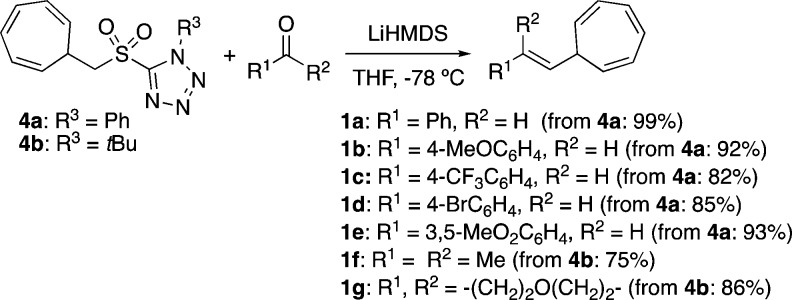

To further extend the scope of the cyclopropanation reaction by increasing the structural diversity on the alkenyl cycloheptatrienes, we also considered applying an olefination reaction as the ideal method considering the wide availability of aldehydes and ketones. Therefore, we prepared the bench-stable Julia–Kocienski reagents 4a,b (Scheme 2).38 These reagents allowed access to a wider variety of alkenylcycloheptatrienes in one step with excellent yields from commercially available carbonyl compounds. Aromatic aldehydes afforded the desired cycloheptatrienes 1a–e with exclusive E selectivity from the lithium salt of 4a at −78 °C. Although poor results were observed for ketones, due to the competing enolization, switching to the bulkier tetrazole 4b led to cycloheptatrienes 1f,g in good yields from acetone or cyclohexanone.

Scheme 2. Formation of 7-Alkenyl-1,3,5-cycloheptatrienes 1a–g via Julia–Kocienski Reaction.

Development of the Vinylcyclopropanation Reaction

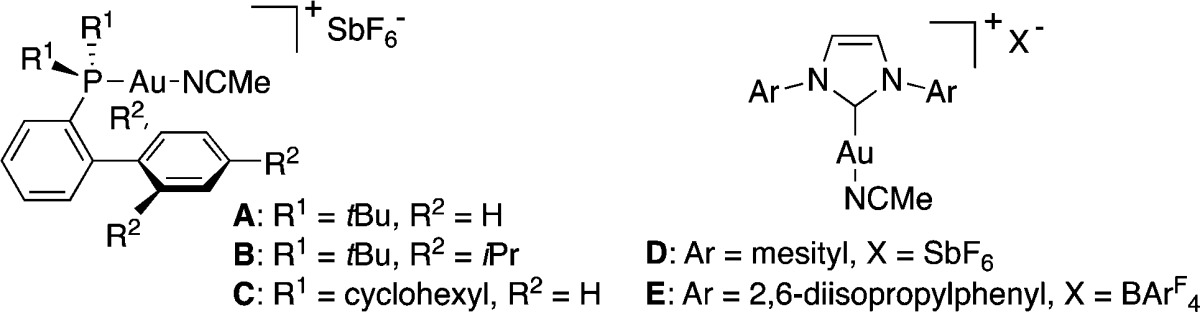

We started by reinvestigating the reaction conditions required to perform the retro-Bucher/cyclopropanation using trans-styrylcycloheptatriene 1a (Table 1). In contrast with the initial conditions (120 °C, 1,2-dichloroethane),30b we found that the reaction of 1a with styrene 2a proceeds smoothly at 75 °C using ethyl acetate as the solvent in the presence of [(Johnphos)Au(MeCN)]SbF6 (A) as catalyst (Table 1, entry 1). While the reaction in 1,2-dichloroethane proceeded in slightly lower yield, much lower catalytic activity was observed in toluene or THF (Table 1, entries 2–4). Increasing or decreasing the steric parameters of the ligand using complexes B and C (Table 1, entries 5 and 6) or changing to NHC-gold(I) complexes D and E had deleterious effects on the reaction outcome (Table 1, entries 7 and 8). When cycloheptatriene 1a was used in excess, small quantities of an inseparable bis-cyclopropane were formed as a result of the cyclopropanation of product 3a. The transformation proved to be robust, as similar yields were obtained when the reaction was performed in commercial ethyl acetate containing small amounts of water.

Table 1. Retro-Buchner/Cyclopropanation To Form 3a.

Reaction Scope

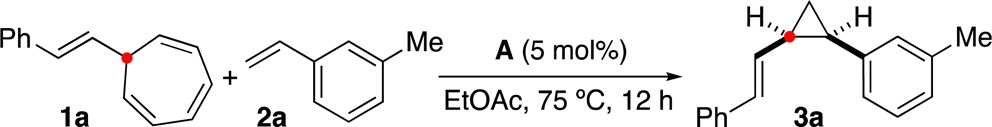

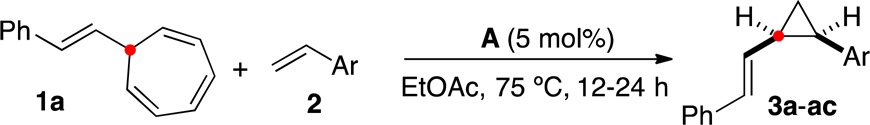

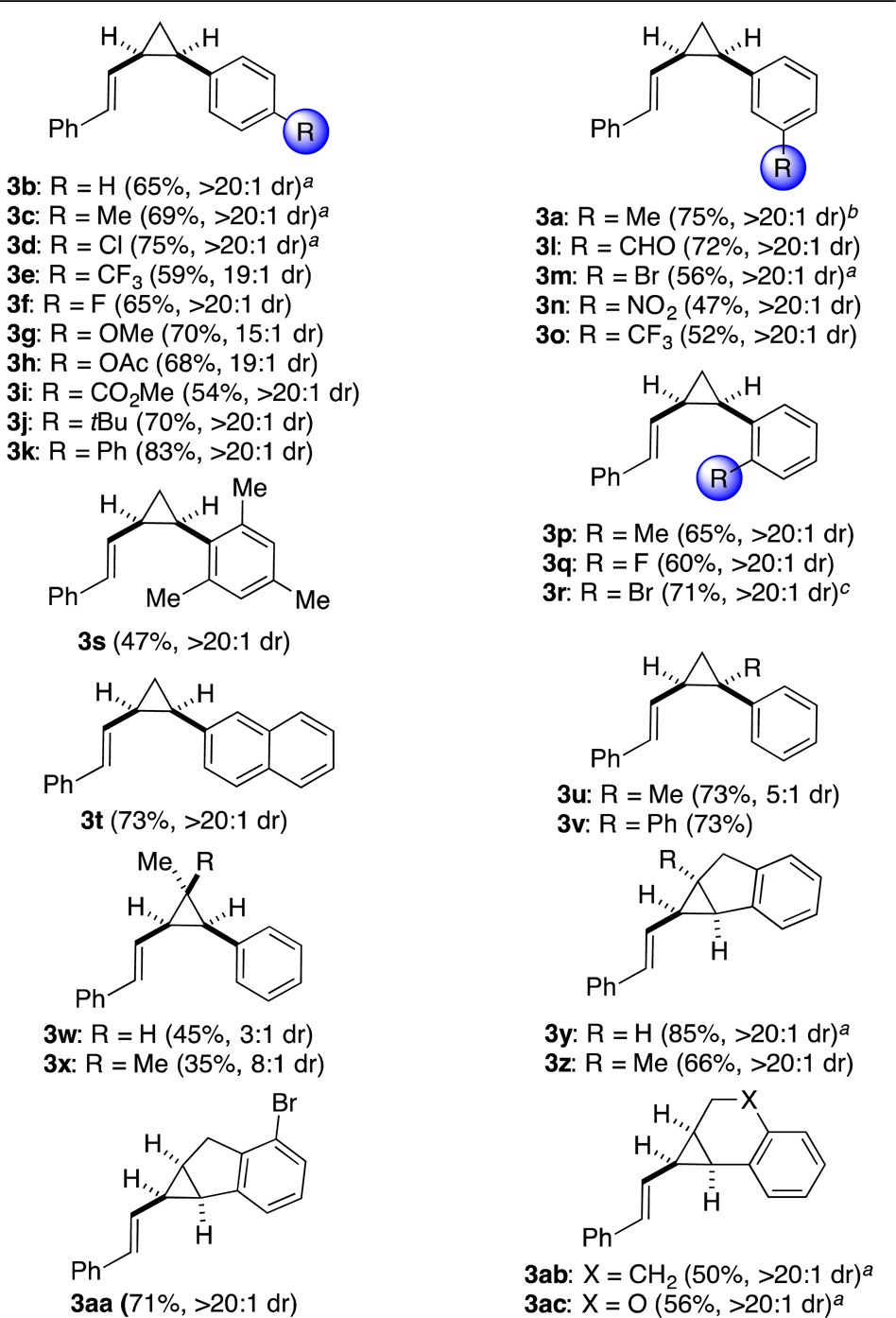

The intermolecular reaction of cycloheptatriene 1a with a variety of para-, meta-, and ortho-substituted styrenes gave the corresponding cis-substituted cyclopropanes 3a–t in moderate to high yields and with excellent cis selectivities (from 15:1 to more than 20:1) (Table 2). In general, electron-rich arenes were slightly better substrates for the reaction and led to higher yields of 3a,c,g,j, whereas electron-poor arenes reacted more slowly, leading to lower yields of 3e,i,n,o. Functional groups such as aldehydes (3l), esters (3h,i), and nitro groups (3n) were well tolerated, as were aryl halides (3d,f,m,q,r). However, traces or low yields of cyclopropanes were observed with non-aryl-substituted alkenes.

Table 2. Synthesis of cis-Arylcyclopropanes 3a–ac from 1ad.

2 equiv of styrene used.

Relative configuration confirmed by X-ray diffraction.

3 equiv of styrene used.

General conditions unless specified otherwise: cycloheptatriene 1 (0.25 mmol), styrene 2 (0.375 mmol), and A (0.0125 mmol, 5 mol %) in EtOAc (1 mL) at 75 °C for 12–24 h.

Disubstituted α-styrenes reacted efficiently to give cyclopropanes 3u,v, albeit with a lower stereoselectivity in the former case. Adding one (3w) or two (3x) substituents to the β-position of the styrene resulted in a decrease in the yield. On the other hand, when cyclic alkenes such as indenes, 1,2-dihydronaphthalene, and 2H-chromene were used, endo-tricycles 3y–ac were obtained essentially as single diastereomers in 50–85% yields.

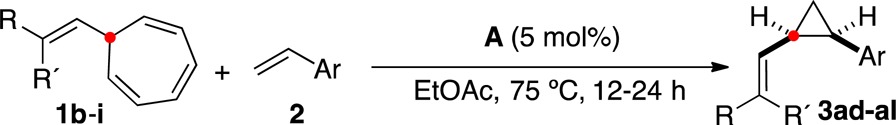

Similarly, alkenylcycloheptatrienes 1b–i gave rise to vinyl cyclopropanes 3ad–al with good to excellent cis selectivities (from 6:1 to more than 20:1) (Table 3).

Table 3. Synthesis of cis-Arylcyclopropanes with Cycloheptatrienes 1b–i.

Relative configuration confirmed by X-ray diffraction.

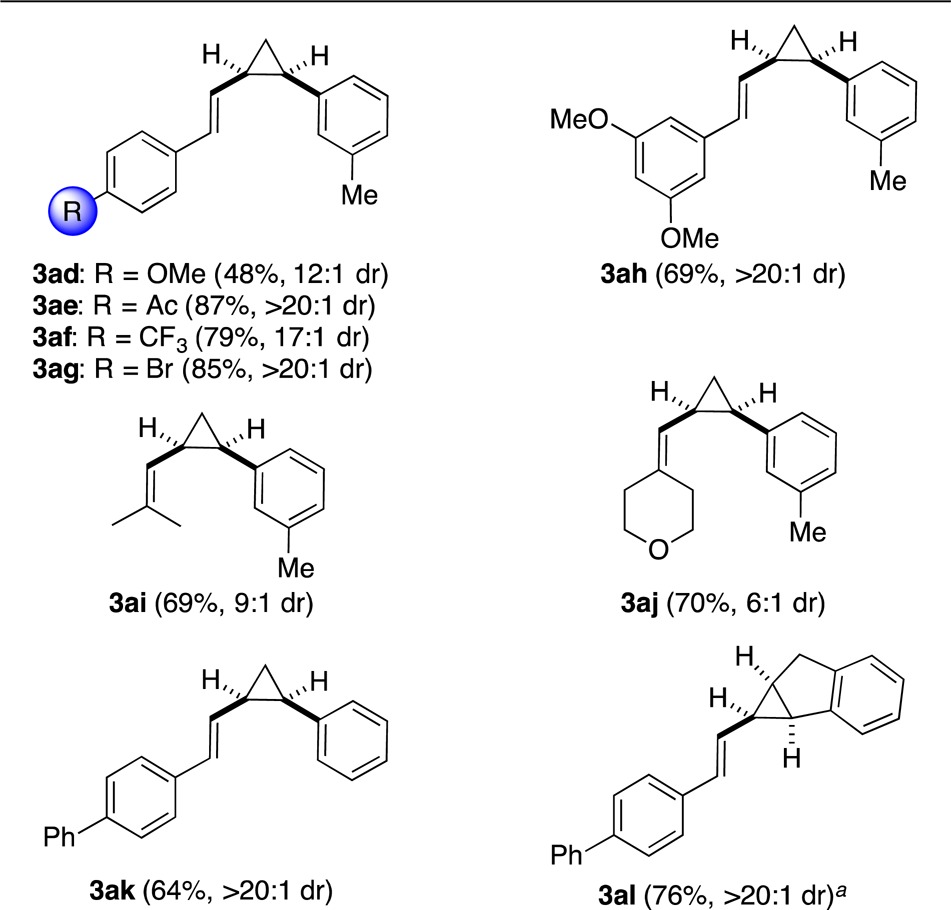

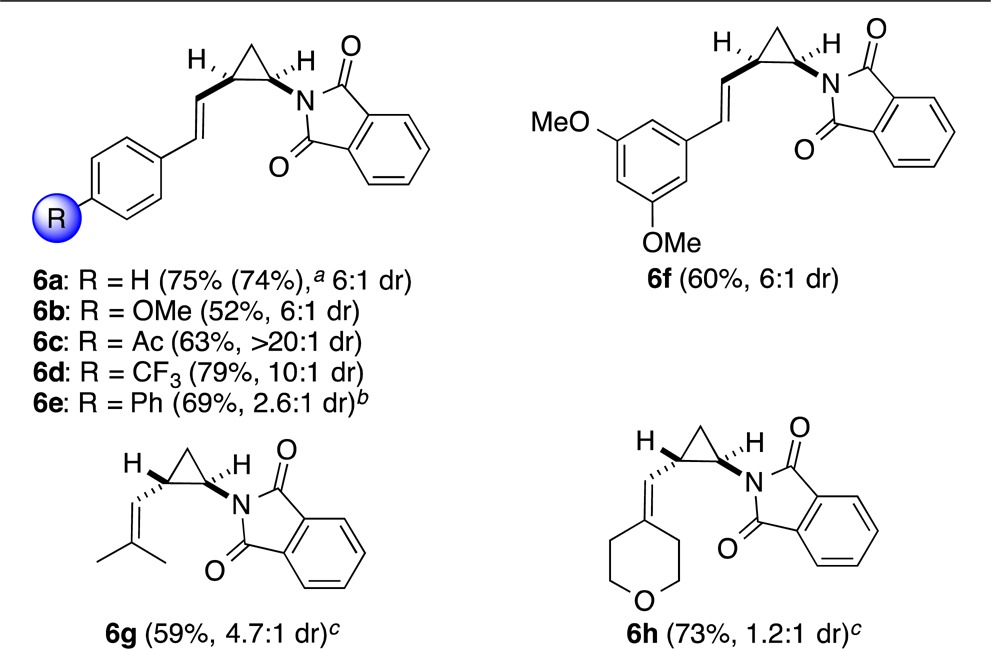

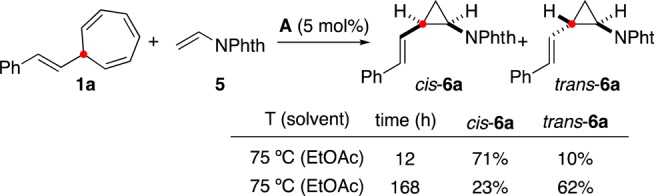

N-Vinylphthalimide (5) was also cyclopropanated to give products 6a–h (Table 4). The robustness of the method was further demonstrated by the synthesis of 6a on a multigram scale with identical high yield and similar diastereoselectivity (7:1 cis:trans). In general, lower cis stereoselectivities were observed using 5 as the alkene, with the exception of 6c, and in the cases of 6g,h the trans derivatives were obtained as the major isomers.

Table 4. Synthesis of N-Protected Aminocyclopropanes 6a–h from N-Vinylphthalimide (5).

Isolated yield for reaction on 10 mmol scale, 2.1 g isolated with 7:1 d.r. See the Supporting Information for details.

Relative configuration (both cis and trans) confirmed by X-ray diffraction.

Major isomer depicted.

Application to the Synthesis of Diverse Cyclopropanes

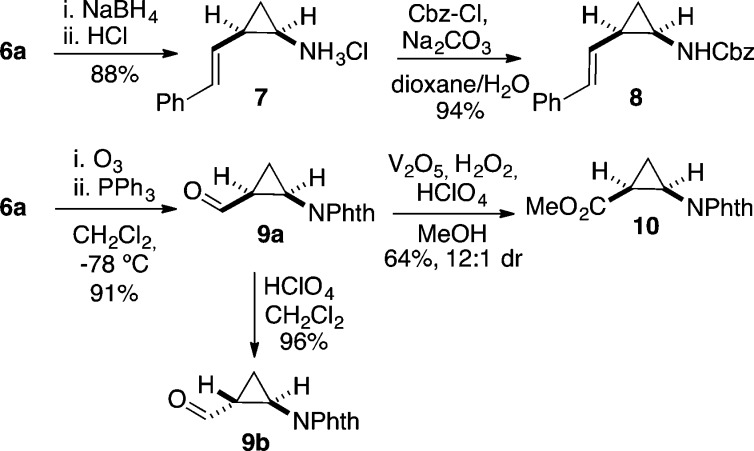

The phthalimido protecting group of 6a could be readily removed by treatment with NaBH4 followed by addition of dry HCl to form the amine hydrochloride 7,39 which could be conveniently reprotected to form carbamate 8 (Scheme 3). Considering the importance of sterically constrained β-amino acids,40,41 we developed a simple access to such building blocks containing a cyclopropane ring. Thus, ozonolysis of 6a followed by reductive workup yielded cis-aldehyde 9a. Subsequent formation of the ester proved challenging, as this push–pull substituted cyclopropane was prone to undergo opening under basic conditions, leading to the corresponding dihydrofuran. Acidic conditions, on the other hand, led to complete epimerization of the aldehyde, affording trans-cyclopropane 9b. Finally, methyl ester 10 could be obtained by oxidation with hydrogen peroxide and vanadium oxide in methanol under mildly acidic conditions.42

Scheme 3. Deprotection of the Phthalimide and Oxidative Cleavage.

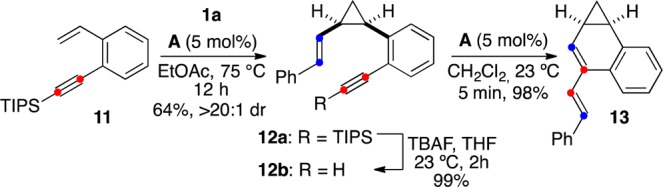

Gold(I)-catalyzed enyne cycloisomerizations are able to rapidly build up chemical complexity.43 We wondered whether it would be possible to selectively cyclopropanate a 1,5-enyne to generate a new 1,7-enyne, which would then be cycloisomerized with the same gold(I) catalyst. To demonstrate this concept, 1,5-enyne 11 was first converted with remarkable chemo- and diastereoselectivity into cis-cyclopropane 12a by reaction with cycloheptatriene 1a in the presence of catalyst A (Scheme 4). After desilylation, 1,7-enyne 12b was cleanly transformed by catalyst A at room temperature to furnish cyclopropyldiene 13 by a single cleavage rearrangement cascade.44

Scheme 4. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Cyclopropanation and 1,7-Enyne Cyclization.

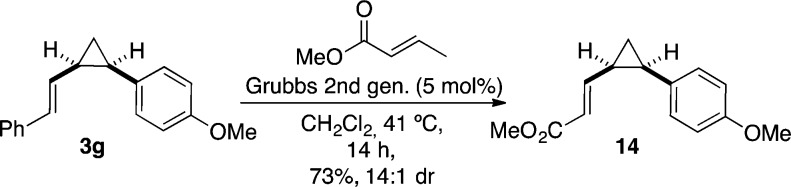

Finally, in order to access substrates bearing electron-withdrawing functional groups at the alkene that would otherwise be beyond the scope of our method, the feasibility of using cross-metathesis on styrylcyclopropanes was investigated. Apart from ring-closing metathesis45 or cross-metathesis on terminal vinylcyclopropanes,46 only a single example of a comparable reaction has been reported.47 It is also important to note that cis–trans isomerization of cyclopropanes has been observed under the conditions of ring-closing metathesis in the presence of Grubbs carbenes via expansion of the intermediate cyclopropylruthenium(II) carbenes to form ruthenacyclopentenes.45d However, using the second-generation Grubbs catalyst,48 cross-metathesis of 3g with methyl crotonate proceeded smoothly to form cis-14 without erosion of the diastereoselectivity (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5. Cross Metathesis of Vinylcyclopropane 3g.

Mechanistic Investigations

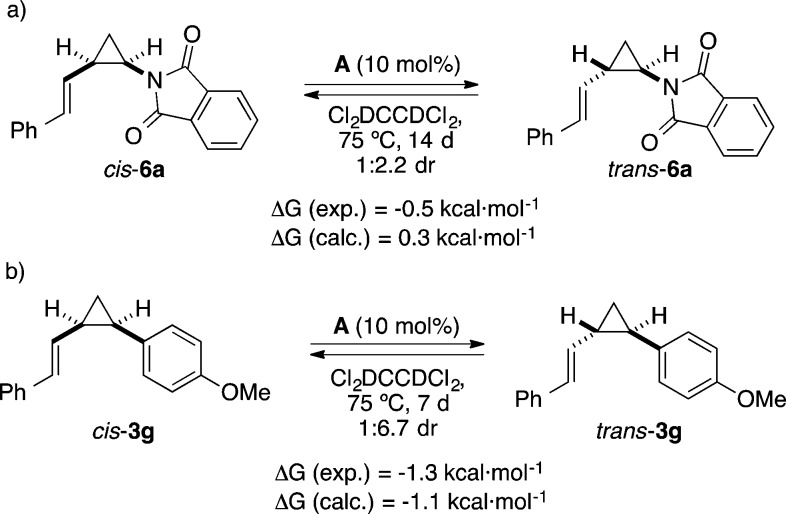

The usually high cis stereoselectivities observed in this study are in contrast with the seemingly erratic stereoselectivities observed before in the cyclopropanation from arylcycloheptatrienes that had to be performed at higher temperatures (120 °C, 1,2-dichloroethane).30b At the same time, we were interested in the lower selectivity observed in the cyclopropanation of N-vinylphthalimide (5) (Table 4). Intriguingly, lower diastereoselectivities were observed when those reactions were performed for longer reaction times. The progress of the reaction between 1a and 5 followed by 1H NMR revealed a fast consumption of the cycloheptatriene 1a along with the formation of cis-6a, which was then followed by a slow isomerization of cis-6a to from trans-6a, until an equilibrium was reached (Scheme 6). Performing the reaction at 120 °C in iPrOAc allowed for the isolation of trans-6a in a synthetically relevant yield of 55%. When pure cis-6a was heated with catalyst A in EtOAc at 75 °C for 132 h, a 1.6:1 mixture of trans-6a and cis-6a was obtained. No isomerization was observed in the absence of the gold(I) catalyst, which excludes a radical background reaction.49−51

Scheme 6. cis–trans Isomerization of Vinylcyclopropanes.

Yields determined by 1H NMR (diphenylmethane as internal standard).

We examined theoretically the complete reaction pathways for the formation of 3b and 6a,g by DFT calculations at the M06/6-31G(d)/M06/6-311+G(2d,p) (C, H, N, O, P) and SDD (Au) levels, taking into account the solvent effect (SMD = dichloromethane) and employing JohnPhos as the phosphine ligand.52

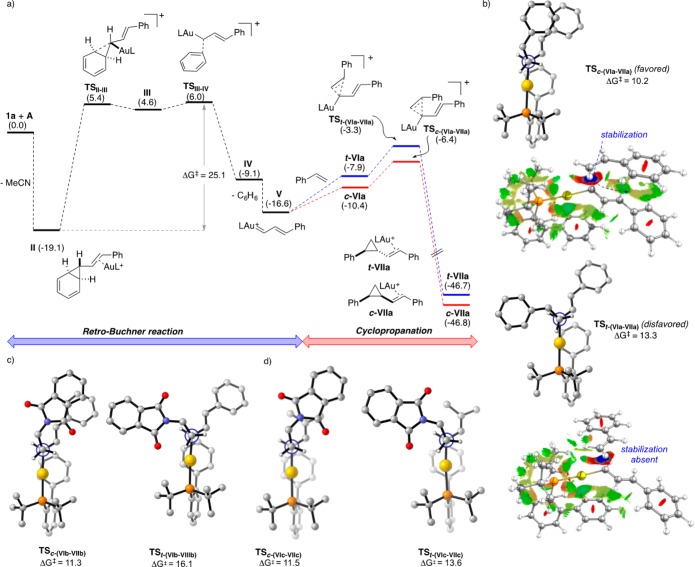

The reaction to form 3b starts with the retro-Buchner reaction of 1a, which involves the stepwise cleavage of two C–C bonds in complex II (Figure 1a). The cleavage of the second bond determines the activation barrier for the generation of gold(I) carbene V, which was calculated to be 25.1 kcal mol–1,53 corresponding to the experimentally estimated value of 27 kcal mol–1.54,55 The cyclopropanation of styrene by V proceeds through an asynchronous concerted mechanism, with an energy difference of 3.1 kcal mol–1 between the cis and trans pathways (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Calculated energies for the gold(I)-catalyzed retro-Buchner reaction and cyclopropanation reaction using SMD(CH2Cl2)-M06/6-311+G(2d,p), SDD(Au, ζf = 1.05)//SMD(CH2Cl2)-M06/6-31G(d), SDD(Au) at the standard state ([Au] = Au-JohnPhos). For the full PES see the Supporting Information. Energies are given in kcal mol–1. (b–d) Newman projections of the cyclopropanation transition states (most hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity) and color-filled RDG isosurface for TS(VIa-VIIa) (isovalue set to 0.5): (blue) areas of attraction (covalent bonding); (green) vdW interaction; (red) areas of repulsion (steric and ring effects).

The cyclopropanations of alkene 5 also favor the cis product,52 through closely similar transition states (Figure 1c,d). Electronic noncovalent interactions, namely π–π interactions in the cis-TS and the lack thereof in the trans-TS, provide an explanation for the preferred formation of cis products56 since the interplanar distances and stabilization energies for the cis-TS are within the typical range for such stabilizing interactions (3.6 Å, 5 kcal mol–1).57 Additionally, calculations corroborate that dispersion interactions are responsible for a significant stabilization of the cis transition states (Table 5, compare rows 2 and 3 for PBE and PBE-D3(BJ) functionals, respectively). Finally, the color-filled reduced density gradient (RDG) isosurface identified the weak van der Waals interactions (in green) between the π systems (Figure 1b).52,58 Remarkably, even in the case of TSc-(VIc-VIIc) (Figure 1d) lacking the phenyl substituent at the carbene, π–π interactions between the alkene and the phthalimide result in the stabilization of the cis-TS.

Table 5. Calculation of Difference in Activation Energies (ΔΔE) between cis- and trans-Cyclopropanationa.

| functional | TSt-(VIa-VIIa) – TSc-(VIa-VIIa) | TSt-(VIb-VIIIb) – TSc-(VIb-VIIb) | TSt-(VIc-VIIc) – TSc-(VIc-VIIc) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M06 | 3.1 | 5.8 | 3.9 |

| PBE | 1.3 | 1.7 | 0.7 |

| PBE-D3(BJ) | 3.2 | 6.0 | 3.7 |

Values given in kcal mol–1.

The calculated mechanisms reveal a unified stereomodel for all three reactions, explaining the diastereoselectivity in the cyclopropanation step, which we consider relevant for other gold-catalyzed cyclopropanation reactions.14a,16b,30b Our model distinguishes itself from a previous proposal16b by considering noncovalent interactions to explain the high diastereoselectivity of the reaction and also takes into account the steric bulk of the phosphine ligand, which forces the substrates to adopt a particularly rigid geometry.

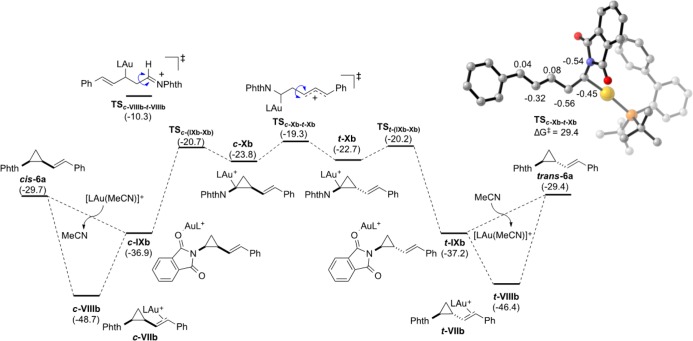

For the subsequent isomerization of the cis-cyclopropanes to the corresponding trans isomers, we identified two transition states with a linear carbocationic structure resulting from the cleavage of the C1–C2 bond (Figure 2).59 As expected, the stability of the transition states depends on the stabilization of the carbocation. For the most favorable pathway, natural bond orbital analysis showed that the positive charge is stabilized as an allylic carbocation in TSc-Xb-t-Xb, resulting in an activation barrier of 29.4 kcal mol–1, which agrees well with the experimentally determined value of 29 kcal mol–1.54 The alternative regioisomeric cleavage of the cyclopropane requires a much higher activation energy (38.4 kcal mol–1) through TSc-VIIIb-t-VIIIb, where the positive charge is stabilized through participation of the nitrogen lone pair leading to an iminium-like structure, as demonstrated by natural population analysis.

Figure 2.

Calculated energies for the gold-catalyzed cis–trans isomerization and NPA charges of TScXb-t-Xb (hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity). Computational details are identical with those in Figure 1. Energies are given in kcal mol–1. For the full PES see the Supporting Information.

In analogy to the isomerization pathway of cis-6a, a linear, carbocationic transition state with a relatively low activation energy of 25.9 kcal mol–1 was also identified for the isomerization of cyclopropane cis-6g.52

The isomerization reaction of a phthalimide-substituted cyclopropane such as 6a was found to be more general (Scheme 7).60 Thus, for example, p-methoxy-substituted substrate cis-3g could be isomerized to form trans-3g by heating in the presence of gold(I) complex A.

Scheme 7. Experimental and Theoretical Determination of the cis–trans Equilibration of Cyclopropanes 3g and 6a(37).

Conclusions

We have developed a highly cis selective gold-catalyzed cyclopropanation for the formation of vinylcyclopropanes and vinylaminocyclopropanes using stable and readily available 7-alkenyl-1,3,5-cycloheptatrienes as the source of the reactive metal carbenes. Remarkably, the decarbenation takes place at 75 °C, under conditions much milder than those required for other cycloheptatrienes. Our method allows for the preparation of diversely functionalized cis-cyclopropanes in diastereomerically pure form. Combined experimental and computational investigations of the reaction mechanism led to a refined stereochemical model for the cyclopropanation, in which stabilizing π–π interactions account for the excellent cis selectivity. In addition, the mechanism of an unprecedented gold(I)-catalyzed cis–trans isomerization of cyclopropanes has been elucidated, which also allows for the preparation of trans-cyclopropanes. With a more clear understanding of the selectivity-determining elements, we are currently pursuing the development of enantioselective cyclopropanation reactions based on the retro-Buchner reaction.

Acknowledgments

We thank the European Research Council (Advanced Grant No. 321066), MINECO/FEDER, UE (CTQ2016-75960-P), MINECO-Severo Ochoa Excellence Acreditation 2014-2018 (SEV-2013-0319), the AGAUR (2014 SGR 818), and CERCA Program/Generalitat de Catalunya for financial support. We also thank Yahui Wang for additional work on the synthesis of cycloheptatrienes from trifluoroborate salts, Imma Escofet for work on the isomerization of 1,2-diarylcyclopropanes, Dr. Andrey I. Konovalov for his assistance with the DFT calculations and helpful discussions, and the ICIQ X-ray diffraction unit.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acscatal.7b00737.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Donaldson W. A. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 8589–8627. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)00777-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Faust R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2251–2253. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wessjohann L. A.; Brandt W. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 1625–1648. 10.1021/cr0100188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Chen D. Y. K.; Pouwer R. H.; Richard J.-A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4631–4642. 10.1039/c2cs35067j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Hiratsuka T.; Suzuki H.; Minami A.; Oikawa H. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 1076–1079. 10.1039/C6OB02675C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Talele T. T. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 8712–8756. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bajaj P.; Sreenilayam G.; Tysagi V.; Fasan R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 16110–16114. 10.1002/anie.201608680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tang P.; Qin Y. Synthesis 2012, 44, 2969–2984. 10.1055/s-0032-1317011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kulinkovich O. G.Cyclopropanes in Organic Synthesis; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2015. [Google Scholar]; c Ganesh V.; Chandrasekaran S. Synthesis 2016, 48, 4347–4380. 10.1055/s-0035-1562530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Baldwin J. E. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 1197–1212. 10.1021/cr010020z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hudlický T.; Kutchan T. M.; Naqvi S. M. Organic Reactions 1985, 33, 247–335. 10.1002/0471264180.or033.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Hudlický T.; Reed J. W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4864–4876. 10.1002/anie.200906001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Jiao L.; Yu Z.-X. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 6842–6848. 10.1021/jo400609w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fumagalli G.; Stanton S.; Bower J. F. Chem. Rev. 2017, 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin M.; Rubina M.; Gevorgyan V. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 3117–3179. 10.1021/cr050988l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Davies H. M. L.; Antoulinakis E. G. Org. React. 2001, 57, 1–326. 10.1002/0471264180.or057.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Lebel H.; Marcoux J.-F.; Molinaro C.; Charette A. B. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 977–1050. 10.1021/cr010007e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Benoit G.; Charette A. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1364–1376. 10.1021/jacs.6b09090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Lévesque É.; Laporte S. T.; Charette A. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 837–841. 10.1002/anie.201608444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto A.; Fructos M. R.; Díaz-Requejo M. M.; Pérez P. J.; Pérez-Galán P.; Delpont N.; Echavarren A. M. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 1790–1793. 10.1016/j.tet.2008.10.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Methylene transfer from diiodomethane by photoredox catalysis:del Hoyo A. M.; Herraiz A. G.; Suero M. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1610–1613. 10.1002/anie.201610924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia M.; Ma S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9134–9166. 10.1002/anie.201508119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Motherwell W. B.; Roberts L. R. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1992, 1582–1583. 10.1039/c39920001582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Motherwell W. B.; Roberts L. R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 1121–1124. 10.1016/0040-4039(94)02410-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Aggarwal V. K.; de Vicente J.; Bonnert R. V. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 2785–2788. 10.1021/ol0164177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Adams L. A.; Aggarwal V. K.; Bonnert R. V.; Bressel B.; Cox R. J.; Shepherd J.; de Vicente J.; Walter M.; Whittingham W. G.; Winn C. L. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 9433–9440. 10.1021/jo035060c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhang J.-L.; Chan P. W. H.; Che C.-M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 8733–8737. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.09.157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Wang Y.; Wen X.; Cui X.; Wojtas L.; Zhang X. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1049–1052. 10.1021/jacs.6b11336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies H. M. L.; Alford J. S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5151–5162. 10.1039/C4CS00072B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Bauer J. T.; Hadfield M. S.; Lee A.-L. Chem. Commun. 2008, 6405–6407. 10.1039/b815891f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b González M. J.; González J.; López L. A.; Vicente R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 12139–12143. 10.1002/anie.201505954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Miege F.; Meyer C.; Cossy J. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4144–4147. 10.1021/ol101741f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Miege F.; Meyer C.; Cossy J. Chem. - Eur. J. 2012, 18, 7810–7822. 10.1002/chem.201200566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Archambeau A.; Miege F.; Meyer C.; Cossy J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1021–1031. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Qian D.; Zhang J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 677–698. 10.1039/C4CS00304G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogo H.; Iwasawa N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 10057–10060. 10.1002/anie.201604371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Miki K.; Ohe K.; Uemura S. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 8505–8513. 10.1021/jo034841a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Johansson M. J.; Gorin D. J.; Staben S. T.; Toste F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 18002–18003. 10.1021/ja0552500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sperger C. A.; Tungen J. E.; Fiksdahl A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2011, 3719–3722. 10.1002/ejoc.201100291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Iqbal N.; Sperger C. A.; Fiksdahl A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 907–914. 10.1002/ejoc.201201328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhang L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 877–888. 10.1021/ar400181x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zheng Z.; Wang Z.; Wang Y.; Zhang L. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 4448–4458. 10.1039/C5CS00887E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Vasu D.; Hung H.-H.; Bhunia S.; Gawade S. A.; Das A.; Liu R.-S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 6911–6914. 10.1002/anie.201102581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Schulz J.; Jasik J.; Gray A.; Roithová J. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 9827–9834. 10.1002/chem.201601634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Of the aforementioned methods,16 greater than 15:1 cis:trans stereoselectivity was only achieved in a few selected examples.

- Feldman K. S.; Simpson R. E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 6985–6988. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)93404-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Mauleón P.; Krinsky J. L.; Toste F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4513–4520. 10.1021/ja900456m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhou S.-M.; Yan Y.-L.; Deng M.-Z. Synlett 1998, 1998, 198–200. 10.1055/s-1998-863093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Zhou S.-M.; Deng M.-Z. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 3951–3954. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)00490-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Ty N.; Pontikis R.; Chabot G. G.; Devillers E.; Quentin L.; Bourg S.; Florent J.-C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 1357–1366. 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson L. W.; Lucas E. L.; Tollefson E. J.; Jarvo E. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 14006–14011. and references therein 10.1021/jacs.6b07567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Davies H. M. L.; Cantrell W. R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 6509–6512. 10.1016/0040-4039(91)80206-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Davies H. M. L.; Huby N. J. S.; Cantrell W. R.; Olive J. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 9468–9479. 10.1021/ja00074a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Davies H. M. L.; Bruzinski P. R.; Lake D. H.; Kong N.; Fall M. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 6897–6907. 10.1021/ja9604931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Müller P.; Bernardinelli G.; Allenbach Y. F.; Ferri M.; Flack H. D. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 1725–1728. 10.1021/ol049554n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Denton J. R.; Davies H. M. L. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 787–790. 10.1021/ol802614j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Qin C.; Boyarskikh V.; Hansen J. H.; Hardcastle K. I.; Musaev D. G.; Davies H. M. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 19198–19204. 10.1021/ja2074104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iridium-catalyzed cyclopropanation with vinyldiazolactone:Ichinose M.; Suematsu H.; Katsuki T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 3121–3123. 10.1002/anie.200805527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intermolecular vinyl cyclopropanation via Rh-catalyzed addition of boryl derivatives to strained alkenes:; a Miura T.; Sasaki T.; Harumashi T. M.; Murakami M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2516–2517. 10.1021/ja0575326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tseng N.-W.; Mancuso J.; Lautens M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 5338–5339. 10.1021/ja060877j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tseng N.-W.; Lautens M. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 2521–2526. 10.1021/jo900039g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hurd C. D.; Lui S. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1935, 57, 2656–2657. 10.1021/ja01315a097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Brewbaker J. L.; Hart H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 711–715. 10.1021/ja01031a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Salomon R. G.; Salomon M. F.; Heyne T. R. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 756–760. 10.1021/jo00894a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alkenyldiazoalkanes can be trapped by benzoic acid at low temperatures:; a Rendina V. L.; Kingsbury J. S. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 1181–1185. 10.1021/jo202214e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wommack A. J.; Kingsbury J. S. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 10573–10587. 10.1021/jo401377a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Meijere A.; Schulz T.-J.; Kostikov R. R.; Graupner F.; Mur T.; Bielfeldt T. Synthesis 1991, 1991, 547–560. 10.1055/s-1991-26514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roda N. M.; Tran D. N.; Battilocchio C.; Labes R.; Ingham R. J.; Hawkins J. M.; Ley S. V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 2550–2554. 10.1039/C5OB00019J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara O. A.; Maguire A. R. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 9–40. 10.1016/j.tet.2010.10.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Solorio-Alvarado C. R.; Echavarren A. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11881–11883. 10.1021/ja104743k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Solorio-Alvarado C. R.; Wang Y.; Echavarren A. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 11952–11955. 10.1021/ja205046h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Correction:; Solorio-Alvarado C. R.; Wang Y.; Echavarren A. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 2529–2529. 10.1021/jacs.6b11935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wang Y.; McGonigal P. R.; Herlé B.; Besora M.; Echavarren A. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 801–809. 10.1021/ja411626v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wang Y.; Muratore M. E.; Rong Z.; Echavarren A. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 14022–14026. 10.1002/anie.201404029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Related gold(I)-promoted retro-cyclopropanations have also been shown to occur in the gas phase:; a Batiste L.; Fedorov A.; Chen P. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 3899–3901. 10.1039/c0cc00086h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fedorov A.; Chen P. Organometallics 2010, 29, 2994–3000. 10.1021/om100224h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Fedorov A.; Batiste L.; Bach A.; Birney D. M.; Chen P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12162–12171. 10.1021/ja2041699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Generation of gold(I) carbenes in solution from a gold(I) imidazolium sulfone salt:Ringger D. H.; Chen P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4686–4689. 10.1002/anie.201209569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonigal P. R.; de León C.; Wang Y.; Homs A.; Solorio-Alvarado C. R.; Echavarren A. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 13093–13096. 10.1002/anie.201207682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer S.; Echavarren A. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11178–11182. 10.1002/anie.201606101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- We have also proposed the intermediacy of α,β-unsaturated gold(I) carbenes in other gold(I)-catalyzed transformations:; a Jiménez-Núñez E.; Raducan M.; Lauterbach T.; Molawi K.; Solorio C. R.; Echavarren A. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6152–6155. 10.1002/anie.200902248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gaydou M.; Miller R. E.; Delpont N.; Ceccon J.; Echavarren A. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 6396–6399. 10.1002/anie.201302411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Carreras J.; Livendahl M.; McGonigal P. R.; Echavarren A. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 4896–4899. 10.1002/anie.201402044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Calleja P.; Pablo Ó.; Ranieri B.; Gaydou M.; Pitaval A.; Moreno M.; Raducan M.; Echavarren A. M. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 13613–13618. 10.1002/chem.201602347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Jutz C.; Voithenleitner F. Chem. Ber. 1964, 97, 29–48. 10.1002/cber.19640970106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Minegishi S.; Kamada J.; Takeuchi K. I.; Komatsu K.; Kitagawa T. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 2003, 3497–3504. 10.1002/ejoc.200300245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- See the Supporting Information for experimental details.

- a Blakemore P. R.; Cole W. J.; Kocieński P. J.; Morley A. Synlett 1998, 1998, 26–28. 10.1055/s-1998-1570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kocieński P. J.; Bell A.; Blakemore P. R. Synlett 2000, 365–366. 10.1055/s-2000-6536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Aïssa C. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 360–363. 10.1021/jo051693a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alford J. S.; Davies H. M. L. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 6020–6023. 10.1021/ol3029127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Koglin N.; Zorn C.; Beumer R.; Cabrele C.; Bubert C.; Sewald N.; Reiser O.; Beck-Sickinger A. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 202–205. 10.1002/anie.200390078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gnad F.; Poleschak M.; Reiser O. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 4277–4280. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Lang M.; De Pol S.; Baldauf C.; Hofmann H.-J.; Reiser O.; Beck-Sickinger A. G. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 616–624. 10.1021/jm050613s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Urman S.; Gaus K.; Yang Y.; Strijowski U.; Sewald N.; De Pol S.; Reiser O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 3976–3978. 10.1002/anie.200605248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kraus G. A.; Kim H.; Thomas P. J.; Metzler D. E.; Metzler C. M.; Taylor J. E. Synth. Commun. 1990, 20, 2667–2673. 10.1080/00397919008051475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Bubert C.; Cabrele C.; Reiser O. Synlett 1997, 1997, 827–829. 10.1055/s-1997-5747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Beumer R.; Bubert C.; Cabrele C.; Vielhauer O.; Pietzsch M.; Reiser O. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 8960–8969. 10.1021/jo005541l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath R.; Patel B. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 577–579. 10.1021/ol990383+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Jiménez-Núñez E.; Echavarren A. M. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 3326–3350. 10.1021/cr0684319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Obradors C.; Echavarren A. M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 902–912. 10.1021/ar400174p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Dorel R.; Echavarren A. M. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9028–9072. 10.1021/cr500691k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello N.; Rodríguez C.; Echavarren A. E. Synlett 2007, 2007, 1753–1758. 10.1055/s-2007-984502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Examples of cross-metathesis of terminal vinylcyclopropanes:; a Itoh T.; Mitsukura K.; Ishida N.; Uneyama K. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 1431–1434. 10.1021/ol000047p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Itoh T.; Ishida N.; Mitsukura K.; Uneyama K. J. Fluorine Chem. 2001, 112, 63–68. 10.1016/S0022-1139(01)00487-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Tsantrizos Y. S.; Ferland J.-M.; McClory A.; Poirier M.; Farina V.; Yee N. K.; Wang X.-J.; Haddad N.; Wei X. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006, 691, 5163–5171. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2006.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Zeng X.; Wei X.; Farina V.; Napolitano E.; Xu Y.; Zhang L.; Haddad N.; Yee N. K.; Grinberg N.; Shen S.; Senanayake C. H. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 8864–8875. 10.1021/jo061587o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Shu C.; Zeng X.; Hao M.-H.; Wei X.; Yee N. K.; Busacca C. A.; Han Z.; Farina V.; Senanayake C. H. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 1303–1306. 10.1021/ol800183x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Farina V.; Zeng X.; Wei X.; Xu Y.; Zhang L.; Haddad N.; Yee N. K. C.; Senanayake H. Catal. Today 2009, 140, 74–83. 10.1016/j.cattod.2008.07.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Hohn E.; Paleček J.; Pietruszka J.; Frey W. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 2009, 3765–3782. 10.1002/ejoc.200900414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Vriesen M. R.; Grover H. K.; Kerr M. A. Synlett 2014, 25, 428–432. 10.1055/s-0033-1340460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Examples of ring-closing metathesis of non-terminal alkenylcyclopropanes:; a Lloyd-Jones G. C.; Murray M.; Stentiford R. A.; Worthington P. A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 2000, 975–985. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Lloyd-Jones G. C.; Wall P. D.; Slaughter J. L.; Parker A. J.; Laffan D. P. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 11402–11412. 10.1016/j.tet.2006.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verbicky C. A.; Zercher C. K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 8723–8727. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)01568-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A. K.; Choi T.-L.; Sanders D. P.; Grubbs R. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 11360–11370. 10.1021/ja0214882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For discussions on diradical trans–cis isomerization of divinylcyclopropanes in the context of the divinylcyclopropane–cycloheptadiene rearrangement:; a Hudlicky T.; Fan R.; Reed J. W.; Gadamasetti K. G. Organic Reactions 1992, 41, 1–133. 10.1002/0471264180.or041.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Krüger S.; Gaich T. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 163–193. 10.3762/bjoc.10.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thermal cis–trans isomerization of 1,2-diarylcyclopropanes occurs at high temperatures (>200 °C):; a Crawford R. J.; Lynch T. R. Can. J. Chem. 1968, 46, 1457–1458. 10.1139/v68-240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Baldwin J. E. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1988, 31–32. 10.1039/c39880000031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Mechanism:Getty S. J.; Davidson E. R.; Borden W. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 2085–2093. 10.1021/ja00032a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For other types of E/Z isomerizations in cyclopropane derivatives bearing carbonyl substituents:; a Ortiz de Montellano P. R.; Dinizo S. E. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 4323–4328. 10.1021/jo00416a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Sasaki T.; Eguchi S.; Ohno M. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1980, 53, 1469–1470. 10.1246/bcsj.53.1469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Feit B. A.; Elser R.; Melamed U.; Goldberg I. Tetrahedron 1984, 40, 5177–5180. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)91267-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Marcoux D.; Goudreau S. R.; Charette A. B. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 8939–8955. 10.1021/jo902066y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Yamaguchi K.; Kazuta Y.; Abe H.; Matsuda A.; Shuto S. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 9255–9262. 10.1021/jo0302206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Xu X.; Zhu S.; Cui X.; Wojtas L.; Zhang X. P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11857–11861. 10.1002/anie.201305883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The cyclopropanation is exemplified here in detail by the formation of 3b and the cis–trans isomerization by the isomerization for 6a. See the Supporting Information for the additional pathways and full theoretical details.

- The calculated value lies in the same range as the barrier of 23.3 kcal mol–1 calculated for 7-phenylcycloheptatriene.28c

- On the basis of the initial rates, we experimentally estimated an activation barrier of ΔG⧧ = 27 kcal mol–1 for the retro-Buchner reaction and of ΔG⧧ = 29 kcal mol–1 for the cis–trans isomerization. See the Supporting Information for experimental details.

- The activation barrier for the retro-Buchner reaction of 1g in the formation of 8g is determined by the first C–C bond cleavage, which was calculated to be 28.5 kcal mol–1.50

- Soriano E.; Marco-Contelles J. Chem. - Eur. J. 2008, 14, 6771–6779. 10.1002/chem.200800305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a For a discussion of π–π interactions and a comparison of interplanar distances and stabilization energies, see the following review:Salonen L. M.; Ellermann M.; Diederich F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 4808–4842. 10.1002/anie.201007560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b For a recent example that highlights the importance of π–π interactions in stabilizing transition states, see:Seguin T. J.; Wheeler S. E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15889–15893. 10.1002/anie.201609095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. R.; Keinan S.; Mori-Sánchez P.; Contreras-García J.; Cohen A. J.; Yang W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6498–6506. 10.1021/ja100936w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A related cyclopropane isomerization has been calculated by our group, although that process was not experimentally observed:Pérez-Galán P.; Herrero-Gómez E.; Hog D. T.; Martin N. J. A.; Maseras F.; Echavarren A. M. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 141–149. 10.1039/C0SC00335B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 1,2-Diarylcyclopropanes also undergo gold(I)-catalyzed cis–trans isomerization. See the Supporting Information for details.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.