Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

The role of beta cell microRNA (miR)-21 in the pathophysiology of type 1 diabetes has been controversial. Here, we sought to define the context of beta cell miR-21 upregulation in type 1 diabetes and the phenotype of beta cell miR-21 overexpression through target identification.

Methods

Islets were isolated from NOD mice and mice treated with multiple low doses of streptozotocin, as a mouse model of diabetes. INS-1 832/13 beta cells and human islets were treated with IL-1β, IFN-γ and TNF-α to mimic the milieu of early type 1 diabetes. Cells and islets were transfected with miR-21 mimics or inhibitors. Luciferase assays and polyribosomal profiling (PRP) were performed to define miR-21–target interactions.

Results

Beta cell miR-21 was increased in in vivo models of type 1 diabetes and cytokine-treated cells/islets. miR-21 overexpression decreased cell count and viability, and increased cleaved caspase 3 levels, suggesting increased cell death. In silico prediction tools identified the antiapoptotic mRNA BCL2 as a conserved miR-21 target. Consistent with this, miR-21 overexpression decreased BCL2 transcript and B Cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) protein production, while miR-21 inhibition increased BCL2 protein levels and reduced cleaved caspase 3 levels after cytokine treatment. miR-21-mediated cell death was abrogated in 828/33 cells, which constitutively overexpress Bcl2. Luciferase assays suggested a direct interaction between miR-21 and the BCL2 3′ untranslated region. With miR-21 overexpression, PRP revealed a shift of the Bcl2 message towards monosome-associated fractions, indicating inhibition of Bcl2 translation. Finally, overexpression in dispersed human islets confirmed a reduction in BCL2 transcripts and increased cleaved caspase 3 production.

Conclusions/interpretation

In contrast to the pro-survival role reported in other systems, our results demonstrate that miR-21 increases beta cell death via BCL2 transcript degradation and inhibition of BCL2 translation.

Keywords: Animal – mouse, Basic science, Beta cell signal transduction, Cell lines, Islets, Islet degeneration and damage

Introduction

microRNAs (miRNAs) are short, non-coding RNAs that classically inhibit gene expression by increasing mRNA degradation or directly inhibiting mRNA translation [1]. Many studies have identified miRNAs as key regulators of beta cell development, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) and beta cell dysfunction [2–10]. Global expression profiling performed in human and rodent islets subjected to proinflammatory cytokine stress and viral infection as models of type 1 diabetes has demonstrated marked changes in miRNA expression patterns [6, 7, 11]. These findings suggest that beta cell miRNAs may also contribute to the activation of intrinsic beta cell stress pathways that act to augment or even initiate beta cell dysfunction and death during the development of type 1 diabetes [12]. miRNA 21 (miR-21) is an NFκB-dependent miRNA that has been shown to be induced during the evolution of type 1 diabetes [13–15]. This miRNA has been well characterised in other cell types, and has been classically been labelled an ‘oncomiR’ in cancer cells, due to the inhibition of tumour suppressor genes, which produces pro-survival effects [16–18]. However, the role of miR-21 in beta cells has been less clear, with conflicting data regarding pro-survival vs proapoptotic effects [13, 14, 19]. Using human islets and cell line models of type 1 diabetes, we sought here to define the context of beta cell miR-21 upregulation and the phenotype of beta cell miR-21 overexpression by novel target identification. Our findings demonstrate an interaction between beta cell miR-21 and the antiapoptotic mRNA BCL2, resulting in dual effects on BCL2 transcript abundance as well as Bcl2 translation.

Methods

Animals, islets and cell culture

Eight-week-old male C57BL6/J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were treated with normal saline (154 mmol/l NaCl) or streptozotocin (STZ) administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 35 mg/kg per day for 5 days to model type 1 diabetes. Blood glucose level was measured via tail vein nick using an Alphatrak glucometer (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA). Pancreatic islets were isolated by collagenase digestion 1 week after initiation of STZ, as previously described [20]. Eight-week-old female NOD mice (Jackson Laboratories), also used as an animal model of type 1 diabetes, were followed weekly for the onset of diabetes (blood glucose >11.1 mmol/l), at which point islets were isolated for analysis. Non-diabetic NOD mice were followed until 20 weeks of age to rule out the development of diabetes and then euthanised for islet isolation. Islets were also isolated from age-matched CD1 mice (Jackson Laboratories). Animals were maintained within the Indiana University Laboratory Animal Resource Center under pathogen-free conditions and protocols approved by the institutional animal care and use committee, in accordance with the Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals [21].

INS-1 832/13 and 828/33 cells were obtained from C. Newgard, Duke University, NC, USA and are commonly used by many investigators in the field [22, 23]. To ensure reproducibility, we adhere to standard culture techniques between all laboratory members and experiments. Cells were only used between passages 8 and 30 and the authenticity of the cell line was verified through maintenance of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. INS-1 mycoplasma testing was performed to ensure negative status. INS-1 832/13 and 828/33 cells or cadaveric human islets from non-diabetic donors (obtained from the Integrated Islet Distribution Program, exempt from Institutional Review Board approval) were cultured as described [23, 24] and treated with a cytokine mix consisting of 5ng/ml IL-1β, 100ng/ml IFN-γ and 10ng/ml TNF-α for 6, 24 or 48 h. Cells were also treated with high glucose (25 mmol/l) or tunicamycin (300nmol/l) for 24 h.

Transfection

INS-1 832/13 and 828/33 cells were seeded into a 12-well plate at a density of 4×105 cells/well and treated for 48 h with miR-21 5p (accession no. MI0000569) mimic used at a concentration of 45 pmol (Qiagen, Düsseldorf, Germany), or 100 pmol locked nucleic acid (LNA) inhibitor (Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark), or negative controls (Qiagen, Exiqon) that had been complexed with 3 μl Lipofectamine 3000 and 100 μl Opti-MEM (both from Thermo Fisher, Grand Island, NY, USA). Relative miR-21 expression after transfection is shown in the electronic supplementary material [ESM] Fig. 1.

For human islet dispersion and transfection, after 4 h of routine incubation at 37°C, islets were suspended in 4 ml of Accutase solution (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) with 100 units of DNase I (Millipore) in a thermal mixer at 37°C, 1000 rev/min for 10 min, followed by the addition of 10 ml of culture medium. Dispersed cells were collected by centrifugation at 200 g for 3 min, and then resuspended in culture medium and seeded into 12-well tissue culture plates (Falcon, Tewksbury, MA, USA). Dispersed cells from 200 islets were transfected with 23 pmol of either negative control miRNA or miR-21 mimic using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent as described above. Cleaved caspase 3 ELISA (ThermoFisher) was performed on transfected human islets as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Reporter assays

Luciferase assays were performed using a Gaussia luciferase/secreted alkaline phosphatase dual reporter system (GeneCopoeia, Rockville, MD, USA). Plasmids containing the cloned wild-type human BCL2 3′ untranslated region (UTR) or a mutated 3′ UTR (positions 710–716 or 720–726) downstream of a secreted Gaussia luciferase reporter, driven by an SV40 promoter, and a secreted alkaline phosphatase reporter driven by a CMV promoter were generated by GeneCopoeia. INS-1 cells were seeded in a 12-well plate and then treated with 1μg of plasmid DNA complexed with 3 μl of Lipofectamine 3000 (in 100 μl Opti-MEM) for 24 h. Cells were then trypsinised and reseeded, followed by transfection with a miR-21 mimic or negative control, as above, for 24 h. A dual reporter luciferase assay kit (GeneCopoeia) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions to quantify luciferase activity in 10 μl of medium. Results were normalised to secreted alkaline phosphatase activity measured using a SpectraMax M5 multiwell plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Cell counting and immunofluorescence

Cell counting was performed using 20 μl of trypsinised and resuspended INS-1 cells on a Cellometer (Nexcelom Bioscience, Lawrence, MA, USA). Live/dead staining was performed with acridium orange/propidium iodide dye (AOPI; Nexcelom Bioscience) mixed 1:1 with suspended cells after trypsinisation. Fluorescence detection of the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in INS-1 cells was performed using CellROX Deep Red Reagent (ThermoFisher) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were imaged on a LSM 700 fluorescent confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss, Göttingen Germany), and fluorescence intensity was assessed as mean signal per well using ZEN 2011 image processing software (Zeiss).

Quantitative real-time PCR

RNA isolation and reverse transcription was performed using miRNeasy and miScript II RT kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using the miScript SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) and a Mastercycler ep realplex instrument (Eppendorf, Hauppage, NY, USA). Relative RNA levels were established against the invariant small nuclear RNA RNU6-1 for miRNAs and β-actin for mRNA species, using the comparative Ct method [25]. RNA primer sequences are listed in ESM Table 1.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described [26]. Bound primary antibodies were detected with donkey anti-mouse or donkey anti-rabbit antibodies. Antibody characteristics are detailed in ESM Table 2. Immunoreactivity was visualised using fluorometric scanning on an Odyssey imaging system and quantified by LI-COR software (both from LI-COR Biotech, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Functional and translation assays

GSIS was assayed as previously described [27]. Supernatants were collected and assayed using a radioimmunometric assay for insulin (Millipore). Values were normalised to the total insulin content of the islet fraction. Polyribosomal profiling (PRP) experiments were performed on INS-1 cell lysates as previously described [28]. Total RNA was reverse transcribed and qPCR was performed using SYBR Green methodology as above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 6.00 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Student’s t tests were used for comparison between the treatment and control groups. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post test for multiple comparisons was used when comparing more than two groups. For all analyses, a p value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

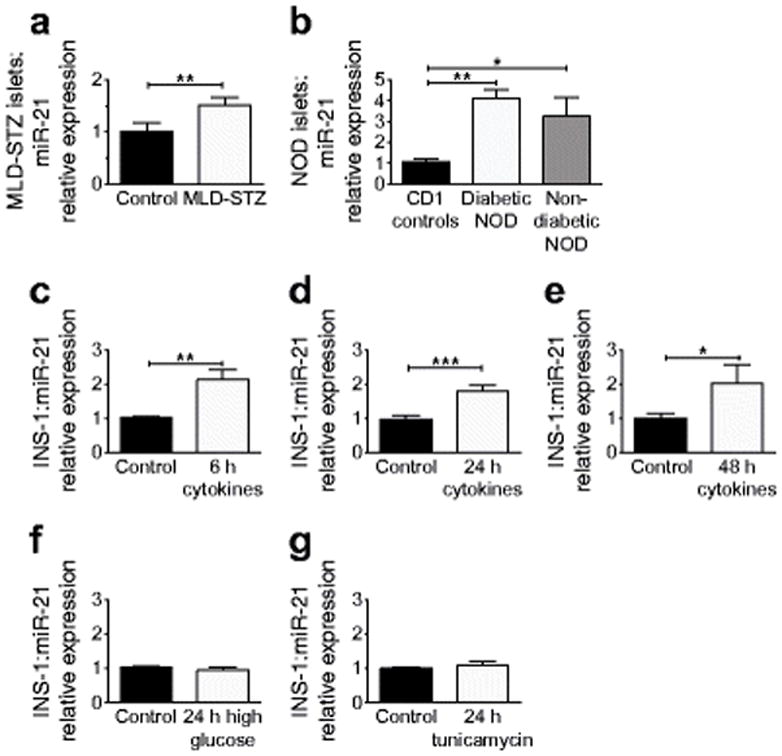

In order to determine whether inflammation present during the development of type 1 diabetes was responsible for induction of beta cell miR-21, several models of type 1 diabetes were utilised. Islets were isolated from two in vivo mouse models of type 1 diabetes: mice treated with multiple low-dose STZ (MLD-STZ) (obtained 1 week after treatment initiation) and NOD mice (at the time of onset of diabetes). Mice treated with MLD-STZ had increased islet miR-21 expression relative to saline-injected controls (Fig. 1a), while islets from diabetic NOD mice demonstrated an even more pronounced increase in miR-21 expression compared with CD1 controls (Fig. 1b). Interestingly, islets from non-diabetic NOD mice also exhibited increased miR-21 expression. Next, INS-1 832/13 cells were treated with a cytokine mix for 6, 24 and 48 h, and significantly increased miR-21 expression was observed at all time points (Fig. 1c–e). To define whether this effect on miR-21 could be related to other components of the diabetic milieu, INS-1 cells were treated with 25mM glucose, to induce glucotoxicity and oxidative stress, or 300 nm tunicamycin for 24 h, to induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (Fig. 1f,g). Verification of treatment effects are shown in ESM Fig. 2. Neither condition increased miR-21 expression, suggesting that miR-21 was upregulated specifically in response to proinflammatory signalling and not in response to hyperglycaemia or ER stress.

Fig. 1.

Beta cell miR-21 production is induced in models of inflammation and type 1 diabetes. miR-21 expression was analysed in: islets from (a) mice treated with MLD-STZ or controls treated with saline (n=5) or (b) diabetic and non-diabetic NOD mice (n=7, n=3, respectively) compared with CD1 controls (n=5), (c–e) INS-1 cells treated with cytokine mix for 6, 24 or 48 h (n=5–9), and (f) INS-1 cells treated with high glucose (25 mmol/l) or (g) tunicamycin (300 nmol/l) for 24 h (n=5–6). *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001

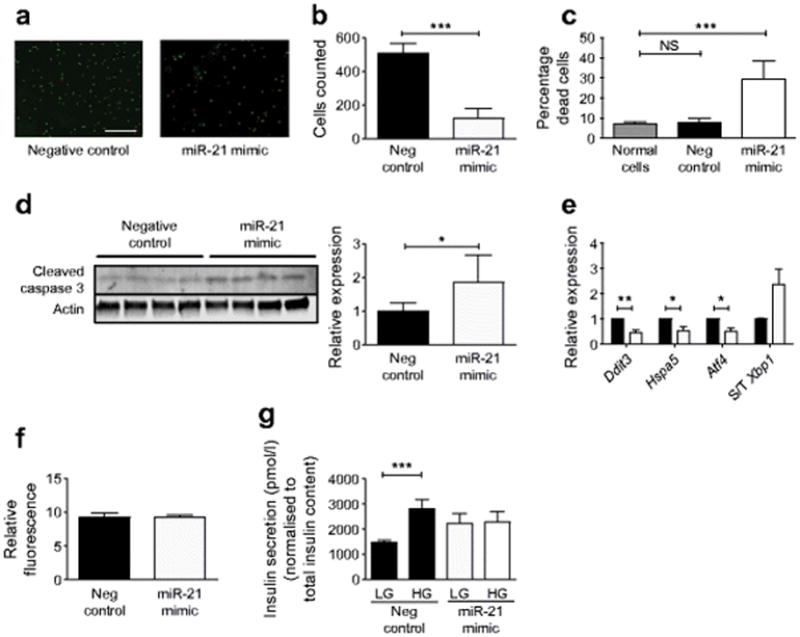

To define the phenotypic effects of increased miR-21 expression, INS-1 832/13 beta cells were transfected with an miR-21 mimic. After 48 h, INS-1 cells with miR-21 overexpression were significantly less confluent than cells transfected with a negative control (Fig. 2a, b), prompting live/dead staining with AOPI (Fig. 2a,c). AOPI staining revealed a significant increase in the percentage of dead INS-1 cells in response to miR-21 overexpression. To ascertain whether activation of intrinsic death pathways was involved, immunoblotting for cleaved caspase 3 was performed (Fig. 2d). A significant increase in cleaved caspase 3 protein levels confirmed a role for apoptosis in this phenotype. To explore activation of other intrinsic stress pathways, we quantified the expression of ER-stress-associated mRNAs in transfected cells. Interestingly, reduced expression of mRNAs encoding C/EBP homologous protein (Chop), the binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP)/glucose regulated protein 78, and activating transcription factor 4 (Atf4) (Fig. 2e) was observed. To assay for the presence of oxidative stress, we performed staining for ROS generation and were unable to detect any differences in transfected cells (Fig. 2f), suggesting that miRNA-21 decreased cell survival independently of ER and oxidative stress. To understand the effect of miR-21 upregulation on beta cell function, GSIS was performed in INS-1 cells transfected with a miR-21 mimic. In contrast to cells transfected with the negative control miRNA, INS-1 cells overexpressing miR-21 showed a blunted insulin secretory response to stimulation with high glucose concentrations (Fig. 2g).

Fig. 2.

miR-21 overexpression increases INS-1 beta cell apoptosis and decreases GSIS. INS-1 cells were transfected with a miR-21 mimic for 48 h to increase miR-21 activity. (a) Viability staining with AOPI, with green staining (AO) representing all cells, and red staining (PI) representing compromised membranes. Scale bar, 400 μm. (b) Total cells and (c) percentage of dead cells were analysed. (d) Immunoblot for cleaved caspase-3. (e) Relative expression of ER stress transcripts was quantified with qPCR: black bars, control cells; white bars, mimic. (f) ROS generation was quantified using CellROX Deep Red Fluorescent Reagent. (g) After miR-21 mimic transfection, GSIS was assayed in response to low (2.5 mmol/l) and high (15 mmol/l) glucose concentrations, and normalised to the total insulin content of the cell lysate. Neg, negative. S/T Xbp1, spliced/total Xbp1. n=4–9. *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001

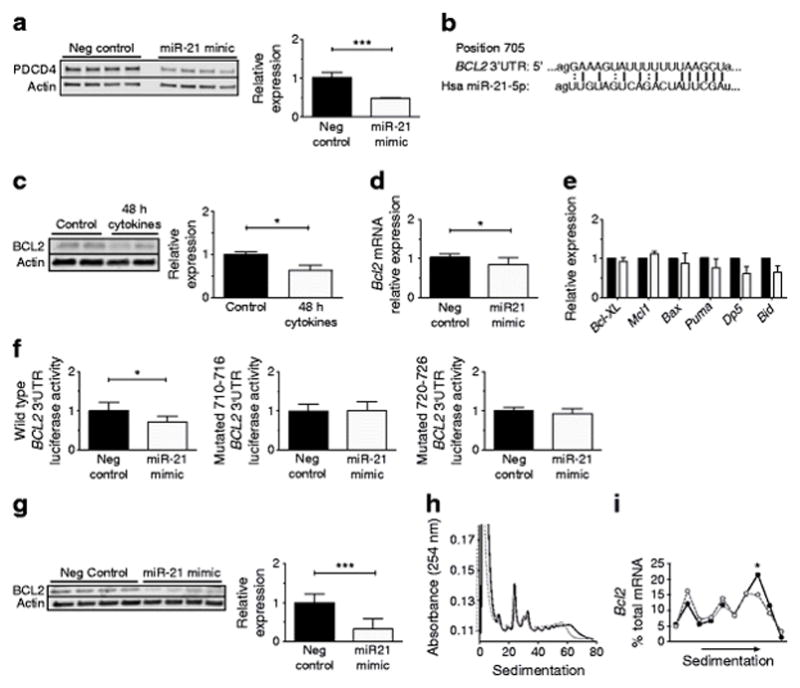

Because the proapoptotic mRNA of the gene encoding programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) has previously been confirmed as a target of beta cell miR-21, immunoblotting for PDCD4 was performed. Our results confirmed reduced PDCD4 protein levels that were consistent with effective miR-21 overexpression (Fig. 3a) [19]. However, our observation that miR-21 overexpression increased beta cell death was at odds with a predicted pro-survival effect of reduced PDCD4. Based on this, we turned to in silico prediction tools to identify other potential miR-21 targets to explain the proapoptotic phenotype of beta cell miR-21 overexpression [29, 30]. We found that the 3′ UTR of the mRNA encoding the antiapoptotic protein B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) was a predicted target for miR-21, with a predicted binding site that was well conserved among vertebrate species [30, 31]. Figure 3b depicts predicted sites of interaction between the human BCL2 3′ UTR and miR-21. Identical consequential pairing regions are predicted at position 704–710 of the mouse Bcl2 3′ UTR and 699–705 of the rat Bcl2 3′ UTR [31].

Fig. 3.

miR-21 reduces BCL2 levels via directly targeting the BCL2 3′ UTR, resulting in reduced mRNA levels and reduced translation of Bcl2 transcripts. (a) After miR-21 mimic transfection into INS-1 cells, immunoblotting was performed for PDCD4 (n=4). (b) Predicted binding sites of miR-21 within BCL2 3′ UTR. (c) Immunoblot for BCL2 after inflammatory cytokine treatment (n=6). (d) Bcl2 mRNA levels after mimic transfection (n=8). (e) mRNA expression of other BCL2 family members (n=4; black bars, control; white bars, mimic). Bcl-XL is also known as Bcl2l1. (f) Luciferase assay was performed on INS-1 cells expressing wild-type or mutated BCL2 3′ UTR and then transfected with a miR-21 mimic (n=4). (g) Immunoblot for BCL2 after miR-21 mimic transfection (n=8). (h, i) PRP analysis was performed after miR-21 mimic transfection (n=3). Solid line, control; dashed line, mimic. (h) Representative global profile. (i) Aggregate data of individual profiles for Bcl2 mRNA. Neg, negative. *p≤0.05; ***p≤0.001

Supporting this prediction, BCL2 protein levels were reduced in parallel with increased miR-21 levels after 48 h of cytokine treatment (Fig. 3c). To verify this relationship, qPCR was performed to assess relative Bcl2 transcript quantity on INS-1 832/13 cells transfected with a miR-21 mimic (Fig. 3d). This analysis revealed decreased transcript levels, consistent with mRNA degradation. In contrast, no significant change in the abundance of transcripts of other BCL2 family members that would be expected to impact apoptosis were detected (Fig. 3e). To determine whether a direct interaction occurred between miR-21 and the BCL2 3′ UTR, INS-1 cells were transfected with plasmids containing a luciferase reporter driven by the wild-type human BCL2 3′ UTR, or BCL2 3′ UTRs that had been mutated at two different sites included in the predicted miR-21 binding region, positions 710–716 or positions 720–726 (Fig. 3f). Cells were then transfected with either the miR-21 mimic or a negative control. Consistent with a direct interaction of miR-21 and the BCL2 3′ UTR, miR-21 overexpression reduced the luciferase activity of INS-1 cells expressing the wild-type BCL2 3′ UTR plasmid. However, no effect of miR-21 overexpression was present in INS-1 cells transfected with mutated 3′ UTR plasmids.

To confirm a miR-21-mediated effect on protein levels, immunoblots for BCL2 protein were performed on INS-1 cells after miR-21 mimic transfection. This analysis demonstrated reduced levels of BCL2 protein with miR-21 overexpression (Fig. 3g). To understand whether the miR-21-mediated reductions in BCL2 protein occurred exclusively through mRNA degradation as shown in Fig. 3d vs direct inhibition of translation, PRP experiments were performed to ascertain the translation status of Bcl2 mRNA. Although no global changes in mRNA translation were seen (Fig. 3h), INS-1 cells overexpressing miR-21 revealed a shift of Bcl2 transcripts towards monosome-associated fractions, and away from the polysome-associated fractions, indicating a reduction in active Bcl2 translation (Fig. 3i). These results suggest that both mRNA degradation and translational inhibition contribute to miR-21-mediated reductions in BCL2 protein levels.

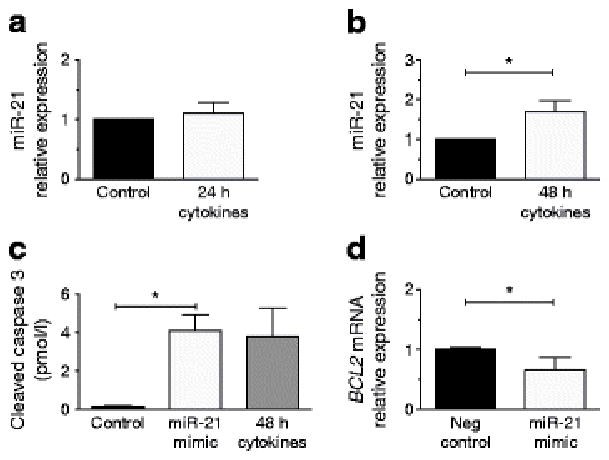

To validate the relevancy of our findings in a human model, human islets were treated with a mix of proinflammatory cytokines for 24 and 48 h. Similar to the results obtained in rodent beta cell lines and islets, we observed a significant increase in miR-21 expression at the 48 h time point (Fig. 4b). To confirm a direct role of miR-21 on BCL2 and apoptosis in human islets, we transfected miR-21 mimics into dispersed islets. Consistent with our findings above, we observed that miR-21 overexpression led to an increase in cleaved caspase 3 (measured using ELISA) and a reduction in BCL2 expression (Fig. 4c,d).

Fig. 4.

Human islet miR-21 is increased by inflammatory cytokine treatment and increases apoptosis in association with reduced BCL2 expression. (a, b) miR-21 expression was quantified after human islets were treated with a cytokine mix for 24 and 48 h. (c) Cleaved caspase 3 was quantified using ELISA in dispersed human islets after miR-21 mimic transfection. A 48 h treatment with cytokine mix was also included as a positive control. (d) BCL2 transcripts were quantified after mimic transfection. Neg, negative. n=3–4. *p≤0.05

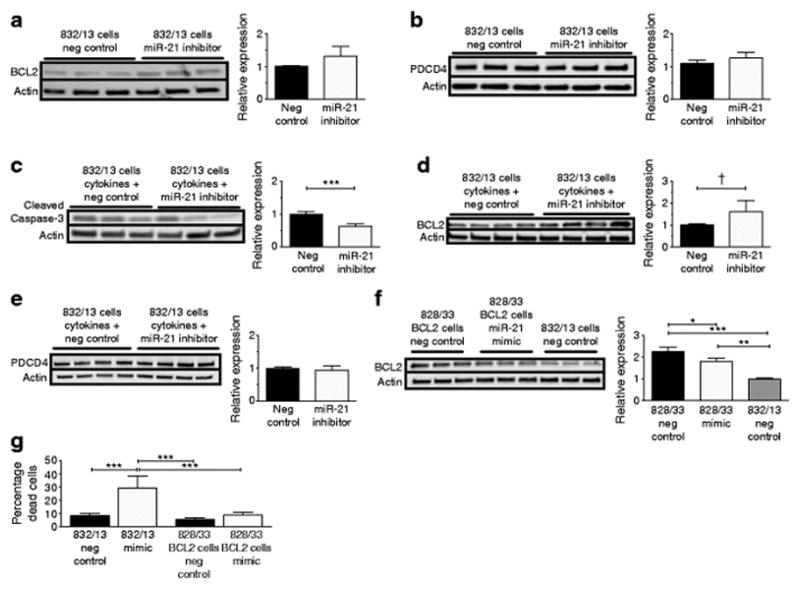

Finally, to define effects of miR-21 inhibition, INS-1 cells were transfected with a miR-21 inhibitor for 48 h (Fig. 5a,b). At baseline, a trend towards increased BCL2 levels was present (Fig. 5a), while PDCD4 levels were unchanged (Fig. 5b). To determine whether miR-21 inhibition had a protective effect against proinflammatory cytokines, INS-1 cells were treated for 16 h with a proinflammatory cytokine mix. Interestingly, in combination with cytokine treatment, miR-21 inhibition reduced cleaved caspase 3 levels compared with negative controls (Fig. 5c). Here, there was a trend towards increased BCL2 levels in cells pretreated with the miR-21 inhibitor (Fig. 5d). Again, no differences were present in PDCD4 levels (Fig. 5e).

Fig. 5.

miR-21 inhibition reduces cytokine-induced cleaved caspase 3 production, while BCL2 overexpression reduces miR-21-mediated apoptosis. (a, b) miR-21 LNA inhibitor was transfected into INS-1 832/13 (wild-type) beta cells for 48 h to inhibit miR-21 activity. Immunoblots for (a) BCL2 and (b) PDCD4 were performed. (c–e) After miR-21 inhibitor treatment, INS-1 832/13 cells were treated with 16 h of cytokine mix, and immunoblots were performed for (c) cleaved caspase 3, (d) BCL2, and (e) PDCD4. (f, g) INS-1 828/33 cells, which constitutively overexpress BCL2, were transfected with a miR-21 mimic for 48 h. (f) Immunoblot for BCL2. (g) Percentage dead cells. Neg, negative. n=3–5. *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001, †p=0.052

In order to ascertain the contribution of BCL2 inhibition to the pro-death effects of miR-21, we transfected INS-1 828/33 cells, which constitutively overexpress Bcl2, with a miR-21 mimic [23]. BCL2 levels were decreased by the miR-21 mimic. However, BCL-2 production remained higher than levels observed in the wild-type INS-1 cells (Fig. 5f). Consistent with this, the percentage of dead cells (assessed by AOPI staining, quantified in Fig. 5g) was significantly lower in BCL2-overproducing INS-1 cells compared with wild-type INS-1 cells transfected with the mimic.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated increased beta cell miR-21 expression in response to cytokines and inflammation, specifically via activation of NFκB signalling [13, 15, 19]. Consistent with other cell types, beta cell miR-21 has been confirmed to target the tumour suppressor PDCD4 [15, 19]. Knockout of islet PDCD4 protected against beta cell death and development of diabetes in NOD mice and after treatment with high-dose STZ, suggesting that miR-21-mediated inhibition of PDCD4 could potentially have a pro-survival effect [19]. However, others have shown that miR-21 overexpression via transfection demonstrated no improvement in beta cell survival [13]. More recent work reported increased beta cell apoptosis after stable lentiviral miR-21 overexpression. However, the authors did not observe concurrent reductions in PDCD4 with miR-21 overexpression, or identify a mechanism explaining the potential proapoptotic effects of miR-21 [14], leaving a number of unresolved controversies regarding the effect of miR-21 on beta cell survival and function.

Consistent with other studies, we found that beta cell miR-21 was induced by multiple in vitro and in vivo models of inflammation and type 1 diabetes, including cytokine treatment of human islets, islets from mice treated with MLD-STZ, and NOD mouse islets. Moreover, we ruled out contributions from ER stress or hyperglycaemia associated with development of diabetes. The elevation of miR-21 in non-diabetic NOD islets is an interesting finding, and is consistent with inflammatory induction of miR-21 expression, as NOD–severe combined immunodeficiency mice exhibit islet macrophage and dendritic cell infiltration, increased TNF-α signalling and intrinsic islet dysfunction, despite the absence of hyperglycaemia [32, 33]. Of note, and consistent with islet miR-21 expression, we were unable to detect differences in islet Bcl2 mRNA between diabetic and non-diabetic NOD mice (data not shown).

We endeavoured first to clarify the effects of miR-21 on beta cell survival, and second to identify a beta cell miR-21 target to explain these effects. In INS-1 beta cells, our results revealed that miR-21 overexpression, induced using a miR-21 mimic, led to a clear increase in cell death, despite reductions in PDCD4 protein levels. Correspondingly, inhibition of miR-21 was able to reduce cleaved caspase 3 production after cytokine treatment. Differences in our data and previous work may have several explanations, but are mostly likely due to differences in the method, dose and effectiveness of miR-21 manipulation in the target cells. However, we verified that our system resulted in effective miR-21 overexpression by ensuring significant suppression of PDCD4, a verified beta cell miR-21 target. Furthermore, identification of a target that explains the proapoptotic phenotype lends credibility to our system and findings.

Based on in silico prediction tools, we identified the BCL2 3′ UTR as a highly conserved miR-21 binding site. BCL2, a member of the antiapoptotic BCL2-like-protein subgroup of the BCL2 protein family, is involved in regulating the permeabilisation of the mitochondrial outer membrane and apoptosis [34]. When bound to BH3-only ‘activator’ proteins, BCL2-like proteins are able to render activator proteins latent. However, when the interaction between BCL2-like proteins and activator proteins is disrupted, activator proteins are released into the cytoplasm, where they induce a conformational change and activation of proapoptotic Bax-like proteins. This ultimately leads to pore formation in the outer mitochondrial membrane and release of proapoptotic proteins into the cytosol [34, 35]. Because of BCL2’s pro-survival properties, miR-21-mediated reductions in the stability of BCL2 mRNA and suppression of BCL2 translation could explain the proapoptotic phenotype we observed in beta cells [36, 37].

Although BCL2’s 3′ UTR has a predicted miR-21 binding site, reduced BCL2 levels have not been typically identified as an effect of miR-21. On the contrary, in other cell types, miR-21 overexpression has been associated with increased BCL2 protein levels [38–40]. Treatment of breast cancer cells with oestrogen receptor agonists was associated with reductions of miR-21 expression and increased BCL2 mRNA and protein levels, suggesting a potential inhibitory interaction. However, these results could also be explained by a direct effect of oestrogen agonists on BCL2 production [41]. In contrast, our data support a direct interaction between miR-21 and the BCL2 3′ UTR in beta cells, and provide direct evidence of the effect of miR-21 on BCL2 mRNA levels as well as translation. Moreover, we confirmed the link between miR-21 overexpression, reductions in BCL2 and increased apoptosis in human islets. This novel report of miR-21 inhibition of BCL2 may explain the unusual proapoptotic phenotype of miR-21 seen in the beta cell. Indeed, overproduction of BCL2 was able to reduce miR-21-mediated death in INS-1 cells.

There are several limitations to our study. BCL2 overproduction has previously been shown to protect against cytokine-induced apoptosis in beta cell lines and islets ex vivo. However, in vivo BCL2 overproduction delayed but was unable to fully prevent the development of diabetes in NOD mice [36, 42, 43]. Although these data suggest that beta cell BCL2 overproduction may be partially protective, diabetes prevention in this model may require combinatorial approaches with a second intervention, such as immune modulation. Similarly, as previous work has suggested that loss of BCL2 in isolation may not be sufficient to induce apoptosis, key methodological differences in time frame and/or method of BCL2 reduction may explain our observed effects [44, 45].

Finally, BCL2 inhibition has recently been shown to increase beta cell mitochondrial metabolism and GSIS [44]. Because miR-21-induced reductions in BCL2 might be expected to increase GSIS, our findings of decreased GSIS with miR-21 overexpression are not likely to be directly due to reduced BCL2 levels [44]. Our results are probably related to the progression of apoptosis and cell death present in a high percentage of cells, with subsequent degranulation and alterations in function. Alternatively, downregulation of other suggested miR-21 target mRNAs, such as Pclo, which encodes a protein important for cyclic AMP potentiation of insulin secretion, may lead to effects on insulin secretion independent of the effects of miR-21 on cell survival [15]. Further investigation of other miR-21 target mRNAs is needed to fully understand the in vivo relevance of changes in beta cell miR-21 expression.

In conclusion, our results suggest a novel role for miR-21 in the beta cell through the induction of apoptosis via BCL2 mRNA degradation and inhibition of BCL2 mRNA translation. These findings provide an important insight into the role of inflammation-induced elevations in beta cell miR-21 during the development of diabetes. Future work will use in vivo beta cell-specific models to study the effects of miR-21 over- and underexpression in order to define whether modulation of beta cell miR-21 levels might represent a potential target for strategies aimed at reducing beta cell death in diabetes.

Supplementary Material

ESM Fig. 1 miR-21 expression after miR-21 mimic transfection. Relative expression of miR-21 was quantified in (a) INS-1 cells and (b) human islets after 48 hour transfection with miR-21 mimics. n=4 *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01

ESM Fig. 2 Verification of treatment effects for tunicamycin and high glucose. (a) Effective treatment of INS-1 cells with tunicamycin (white bars) compared to controls (black bars) was verified via qPCR, revealing increased expression of ER stress genes. n=4. (b) Oxidative stress induction by high glucose treatment was verified using fluorescent detection of ROS generation. Representative images are shown. (c) Fluorescence quantification. n=3. *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01

ESM Table 1. Primer Sequences

ESM Table 2. Antibody Table

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge P. Fueger of Indiana University (Department of Pediatrics) and C. Newgard of Duke University, NC, USA (Departments of Medicine and Pharmacology and Cancer Biology) for their generous donation of INS-1 828/33 cells, and the Indiana University Center for Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases’ Islet and Physiology Core for assistance with islet isolation. We also thank Y. Gu (Pediatrics, Indiana University) for technical assistance. Some of the data included in this manuscript were previously presented in abstract form at the Midwest Islet Club, the Combined Annual Meeting of the American Federation for Medical Research/Central Society for Clinical and Translational Research, the Pediatric Endocrine Society meeting, and the 76th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, in 2016.

Funding

This manuscript was also supported by funding from NIDDK K08DK103983 to EKS, a Pediatric Endocrine Society Clinical Scholar Award to EKS, a pilot and feasibility award within the Center for Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases NIH/NIDDK Grant Number P30 DK097512, funding by Indiana University Health and the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute to EKS, funded in part by Grant no. KL2TR001106 and Grant no. UL1TR001108, NIH Grant no. 32DK064466 to AL, 1F32DK104501-01A1 to EA-B, and NIH grant R01 DK093954, VA Merit Award I01BX001733 and JDRF SRA-2014-41-Q-R (to CEM). This study used core services provided by the Diabetes Research Center grant P30 DK097512 to Indiana University School of Medicine.

Abbreviations

- AOPI

Acridium orange/propidium iodide

- Atf4

Activating transcription factor 4

- BCL2

B cell lymphoma 2

- BiP

Binding immunoglobulin protein

- Chop

C/EBP homologous protein

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- GSIS

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- LNA

Locked nucleic acid

- miR-21

miRNA 21

- miRNA

microRNA

- MLD-STZ

Multiple low-dose streptozotocin

- PDCD4

Programmed cell death 4

- PRP

Polyribosomal profiling

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- STZ

Streptozotocin

- UTR

Untranslated region

Footnotes

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

EKS conceived and designed the experiments, acquired and analysed the data, and drafted and revised the manuscript. AL acquired and analysed the data and revised the manuscript. EAB the conceived experiments, acquired and analysed the data, and revised the manuscript. TK conceived and designed the experiments, and revised the manuscript. XT contributed to concept and design, acquired and analysed the data, and revised the manuscript. CEM contributed to conception and design, interpreted/analysed the data, and drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published. EKS is responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole.

References

- 1.Ameres SL, Zamore PD. Diversifying microRNA sequence and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:475–488. doi: 10.1038/nrm3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynn FC, Skewes-Cox P, Kosaka Y, McManus MT, Harfe BD, German MS. MicroRNA expression is required for pancreatic islet cell genesis in the mouse. Diabetes. 2007;56:2938–2945. doi: 10.2337/db07-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poy MN, Eliasson L, Krutzfeldt J, et al. A pancreatic islet-specific microRNA regulates insulin secretion. Nature. 2004;432:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature03076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacovetti C, Abderrahmani A, Parnaud G, et al. MicroRNAs contribute to compensatory beta cell expansion during pregnancy and obesity. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:3541–3551. doi: 10.1172/JCI64151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latreille M, Hausser J, Stutzer I, et al. MicroRNA-7a regulates pancreatic beta cell function. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:2722–2735. doi: 10.1172/JCI73066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osmai M, Osmai Y, Bang-Berthelsen CH, et al. MicroRNAs as regulators of beta-cell function and dysfunction. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32:334–349. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KW, Ho A, Alshabee-Akil A, et al. Coxsackievirus B5 Infection Induces Dysregulation of microRNAs Predicted to Target Known Type 1 Diabetes Risk Genes in Human Pancreatic Islets. Diabetes. 2016;65:996–1003. doi: 10.2337/db15-0956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tugay K, Guay C, Marques AC, et al. Role of microRNAs in the age-associated decline of pancreatic beta cell function in rat islets. Diabetologia. 2016;59:161–169. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3783-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filios SR, Shalev A. beta-Cell MicroRNAs: Small but Powerful. Diabetes. 2015;64:3631–3644. doi: 10.2337/db15-0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez-Valverde SL, Taft RJ, Mattick JS. MicroRNAs in beta-cell biology, insulin resistance, diabetes and its complications. Diabetes. 2011;60:1825–1831. doi: 10.2337/db11-0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grieco FA, Sebastiani G, Juan-Mateu J, et al. MicroRNAs miR-23a-3p, miR-23b-3p and miR-149-5p Regulate the Expression of Pro-Apoptotic BH3-Only Proteins DP5 and PUMA in Human Pancreatic Beta Cells. Diabetes. 2017;66:100–112. doi: 10.2337/db16-0592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkinson MA, Bluestone JA, Eisenbarth GS, et al. How does type 1 diabetes develop?: the notion of homicide or beta-cell suicide revisited. Diabetes. 2011;60:1370–1379. doi: 10.2337/db10-1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roggli E, Britan A, Gattesco S, et al. Involvement of microRNAs in the cytotoxic effects exerted by proinflammatory cytokines on pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2010;59:978–986. doi: 10.2337/db09-0881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Backe MB, Novotny GW, Christensen DP, Grunnet LG, Mandrup-Poulsen T. Altering beta-cell number through stable alteration of miR-21 and miR-34a expression. Islets. 2014;6:e27754. doi: 10.4161/isl.27754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bravo-Egana V, Rosero S, Klein D, et al. Inflammation-Mediated Regulation of MicroRNA Expression in Transplanted Pancreatic Islets. Journal of transplantation. 2012;2012:723614. doi: 10.1155/2012/723614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frampton AE, Castellano L, Colombo T, et al. Integrated molecular analysis to investigate the role of microRNAs in pancreatic tumour growth and progression. Lancet. 2015;385(Suppl 1):S37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60352-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haghpanah V, Fallah P, Tavakoli R, et al. Antisense-miR-21 enhances differentiation/apoptosis and reduces cancer stemness state on anaplastic thyroid cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;37:1299–1308. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3923-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagenaar TR, Zabludoff S, Ahn SM, et al. Anti-miR-21 Suppresses Hepatocellular Carcinoma Growth via Broad Transcriptional Network Deregulation. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;13:1009–1021. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruan Q, Wang T, Kameswaran V, et al. The microRNA-21-PDCD4 axis prevents type 1 diabetes by blocking pancreatic beta cell death. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:12030–12035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101450108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stull ND, Breite A, McCarthy R, Tersey SA, Mirmira RG. Mouse islet of Langerhans isolation using a combination of purified collagenase and neutral protease. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2012 doi: 10.3791/4137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garber JC, Barbee RW, Bielitzki JT, et al. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. The National Academic Press, Washington DC. 2011;8:220. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hohmeier HE, Newgard CB. Cell lines derived from pancreatic islets. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2004;228:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tran VV, Chen G, Newgard CB, Hohmeier HE. Discrete and complementary mechanisms of protection of beta-cells against cytokine-induced and oxidative damage achieved by bcl-2 overexpression and a cytokine selection strategy. Diabetes. 2003;52:1423–1432. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.6.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kono T, Ahn G, Moss DR, et al. PPAR-gamma activation restores pancreatic islet SERCA2 levels and prevents beta-cell dysfunction under conditions of hyperglycemic and cytokine stress. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:257–271. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakrabarti SK, James JC, Mirmira RG. Quantitative assessment of gene targeting in vitro and in vivo by the pancreatic transcription factor, Pdx1. Importance of chromatin structure in directing promoter binding. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:13286–13293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111857200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson JS, Kono T, Tong X, et al. Pancreatic and duodenal homeobox protein 1 (Pdx-1) maintains endoplasmic reticulum calcium levels through transcriptional regulation of sarco-endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2b (SERCA2b) in the islet beta cell. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:32798–32810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.575191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sims EK, Hatanaka M, Morris DL, et al. Divergent compensatory responses to high-fat diet between C57BL6/J and C57BLKS/J inbred mouse strains. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;305:E1495–E1511. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00366.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatanaka M, Maier B, Sims EK, et al. Palmitate induces mRNA translation and increases ER protein load in islet beta-cells via activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Diabetes. 2014;63:3404–3415. doi: 10.2337/db14-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Betel D, Wilson M, Gabow A, Marks DS, Sander C. The microRNA.org resource: targets and expression. Nucleic acids research. 2008;36:D149–D153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam J-W, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife. 2015;4:e05005. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahlen E, Dawe K, Ohlsson L, Hedlund G. Dendritic cells and macrophages are the first and major producers of TNF-alpha in pancreatic islets in the nonobese diabetic mouse. J Immunol. 1998;160:3585–3593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tersey SA, Nishiki Y, Templin AT, et al. Islet beta-cell endoplasmic reticulum stress precedes the onset of type 1 diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse model. Diabetes. 2012;61:818–827. doi: 10.2337/db11-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinou JC, Youle RJ. Mitochondria in apoptosis: Bcl-2 family members and mitochondrial dynamics. Dev Cell. 2011;21:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gurzov EN, Eizirik DL. Bcl-2 proteins in diabetes: mitochondrial pathways of beta-cell death and dysfunction. Trends in cell biology. 2011;21:424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iwahashi H, Hanafusa T, Eguchi Y, et al. Cytokine-induced apoptotic cell death in a mouse pancreatic beta-cell line: inhibition by Bcl-2. Diabetologia. 1996;39:530–536. doi: 10.1007/BF00403299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabinovitch A, Suarez-Pinzon W, Strynadka K, et al. Transfection of human pancreatic islets with an anti-apoptotic gene (bcl-2) protects beta-cells from cytokine-induced destruction. Diabetes. 1999;48:1223–1229. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.6.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, Yan L, Zhang W, et al. miR-21 inhibitor suppresses proliferation and migration of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells through down-regulation of BCL2 expression. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:3478–3487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dong J, Zhao Y-P, Zhou L, Zhang T-P, Chen G. Bcl-2 upregulation induced by miR-21 via a direct interaction is associated with apoptosis and chemoresistance in MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells. Archives of medical research. 2011;42:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Si M, Zhu S, Wu H, Lu Z, Wu F, Mo Y. miR-21-mediated tumor growth. Oncogene. 2007;26:2799–2803. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wickramasinghe NS, Manavalan TT, Dougherty SM, Riggs KA, Li Y, Klinge CM. Estradiol downregulates miR-21 expression and increases miR-21 target gene expression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Nucleic acids research. 2009;37:2584–2595. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allison J, Thomas H, Beck D, et al. Transgenic overexpression of human Bcl-2 in islet beta cells inhibits apoptosis but does not prevent autoimmune destruction. Int Immunol. 2000;12:9–17. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y, Rabinovitch A, Suarez-Pinzon W, et al. Expression of the bcl-2 gene from a defective HSV-1 amplicon vector protects pancreatic beta-cells from apoptosis. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:1719–1726. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.14-1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luciani DS, White SA, Widenmaier SB, et al. Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL suppress glucose signaling in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2013;62:170–182. doi: 10.2337/db11-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aharoni-Simon M, Shumiatcher R, Yeung A, et al. Bcl-2 Regulates Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling and a Redox-Sensitive Mitochondrial Proton Leak in Mouse Pancreatic β-Cells. Endocrinology. 2016;157:2270–2281. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ESM Fig. 1 miR-21 expression after miR-21 mimic transfection. Relative expression of miR-21 was quantified in (a) INS-1 cells and (b) human islets after 48 hour transfection with miR-21 mimics. n=4 *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01

ESM Fig. 2 Verification of treatment effects for tunicamycin and high glucose. (a) Effective treatment of INS-1 cells with tunicamycin (white bars) compared to controls (black bars) was verified via qPCR, revealing increased expression of ER stress genes. n=4. (b) Oxidative stress induction by high glucose treatment was verified using fluorescent detection of ROS generation. Representative images are shown. (c) Fluorescence quantification. n=3. *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01

ESM Table 1. Primer Sequences

ESM Table 2. Antibody Table