Abstract

The Escherichia coli lac operon is regulated by a positive feedback loop whose potential to generate an all-or-none response in single cells has been a paradigm for bistable gene expression. However, so far bistable lac induction has only been observed using gratuitous inducers, raising the question about the biological relevance of bistable lac induction in the natural setting with lactose as the inducer. In fact, the existing experimental evidence points to a graded rather than an all-or-none response in the natural lactose uptake system. In contrast, predictions based on computational models of the lactose uptake pathway remain controversial. Although some argue in favor of bistability, others argue against it. Here, we reinvestigate lac operon expression in single cells using a combined experimental/modeling approach. To this end, we parameterize a well-supported mathematical model using transient measurements of LacZ activity upon induction with different amounts of lactose. The resulting model predicts a monostable induction curve for the wild-type system, but indicates that overexpression of the LacI repressor would drive the system into the bistable regime. Both predictions were confirmed experimentally supporting the view that the wild-type lac induction circuit generates a graded response rather than bistability. More interestingly, we find that the lac induction curve exhibits a pronounced maximum at intermediate lactose concentrations. Supported by our data, a model-based analysis suggests that the nonmonotonic response results from saturation of the LacI repressor at low inducer concentrations and dilution of Lac enzymes due to an increased growth rate beyond the saturation point. We speculate that the observed maximum in the lac expression level helps to save cellular resources by limiting Lac enzyme expression at high inducer concentrations.

Introduction

The lactose utilization system of Escherichia coli is encoded by the lac operon, which consists of a regulatory promoter-operator region and three structural genes lacZYA (1). Whereas the gene products of lacY and lacZ are involved in uptake and cleavage (metabolism) of lactose (lacY encodes lactose permease, lacZ encodes β-galactosidase; Fig. 1) the function of the transacetylase LacA is less clear (2). Induction of the lac operon by lactose or by the well-studied gratuitous inducers IPTG and TMG is controlled by the lactose repressor LacI. In the absence of lactose, lac gene expression is strongly repressed by LacI through formation of a DNA loop, which preferably occurs between the main operator (O1) and one of the auxiliary operators (O2 and O3) (3) (Fig. 1). If present, lactose is actively transported into the cell by lactose permease (1). Intracellular lactose is metabolized by LacZ in two distinct reactions: The disaccharide is either cleaved into the monosaccharides glucose and galactose, which are used for cell growth, or it is converted into its isomer allolactose, which represents the natural inducer of the lac operon (2). Through sequestration of the LacI repressor, allolactose prevents binding of the repressor to the operator sites.

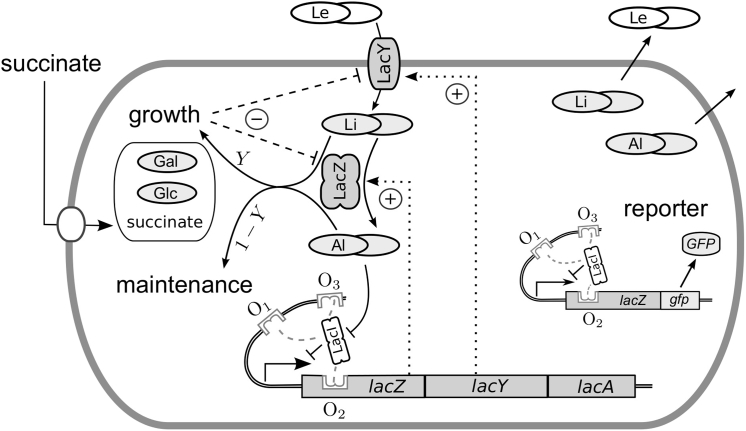

Figure 1.

Scheme of lactose metabolism, gene expression, and model setup. Cells grown on succinate are induced with different amounts of lactose (Le). Internalized lactose (Li) is converted into allolactose (Al). Sequestering of LacI repressor by allolactose induces the synthesis of LacY and LacZ and creates a positive feedback loop (dotted lines). Both lactose and allolactose are also used for growth and maintenance so that an increased uptake rate also increases the dilution rate of the lac enzymes which weakens the positive feedback loop. Cells contain a GFP reporter under the control of a native lac promoter.

Because both enzymes, LacY and LacZ, are involved in the generation of the inducer of their own synthesis, there exists a positive feedback loop in the lac regulatory system that may potentially lead to bistability (4). However, because lactose is also actively metabolized, increased levels in the amount of LacY and LacZ do not only lead to the production of more inducer molecules, but also increase the growth rate, which, in turn, leads to a faster dilution of the Lac enzymes as well as of the inducer. Theoretical studies have shown that this negative feedback may substantially weaken the positive feedback loop (5, 6), which has contributed to the prevailing opinion that bistability is unlikely to be observed in the natural lactose utilization system (5, 7, 8). Consistent with this argument, bistable induction behavior has so far only been observed using artificial inducers, such as TMG (9, 10) or IPTG (11, 12), where lac gene induction is essentially decoupled from cell growth: although uptake of gratuitous inducers is still catalyzed by LacY, they are not metabolized by LacZ. Instead, internalized TMG and IPTG induce lac gene expression through direct binding to the LacI repressor.

In addition to control by LacI, lac operon expression is also controlled by carbon catabolite repression (13). The transcriptional activator complex CRP-cAMP is necessary for efficient transcription of the lac operon, and it has been suggested to enhance DNA looping (14). Its concentration is kept low in the presence of glucose, the preferred substrate of E. coli. In addition, glucose becomes phosphorylated while entering the cell through a sequence of reactions mediated by the PEP-dependent phosphotransferase system (PTS). In the course of this process the glucose-specific PTS protein IIAGlc becomes dephosphorylated, which then binds to LacY and inhibits the uptake of lactose, a process termed “inducer exclusion”.

Even though several theoretical studies came to the conclusion that bistability would be unlikely to occur if lactose is the only galactosidic carbon source in the medium, it remains controversial what to expect in the presence of lactose and glucose. Whereas some authors argue in favor of bistability (5, 15, 16), others argue against it (6, 17). Interestingly, Savageau (6) has derived a design principle, which summarizes, in a mechanism-independent manner, the conditions under which bistability may exist in the natural lactose utilization system. From his analysis, it follows that glucose-mediated effects such as catabolite repression and inducer exclusion make it more difficult to satisfy the conditions required to generate bistability. The design principle also indicates that the natural lac circuit is protected from bistability by the fact that the inducer is an intermediate of the inducible pathway, but that alternative fates of the intermediate, such as LacY-independent excretion from the cell, may promote bistability. Another prediction of the Savageau design principle is that the likelihood of bistability can be increased by increasing the effective cooperativity with which the inducer affects the transcription rate of lac genes. Consistent with this prediction, Narang and Pilyugin (5) argue that DNA looping, which is known to increase the cooperativity of repressor-operator interactions, is essential to overcome the attenuating effect of growth rate-dependent dilution and to promote bistability. Together, these results suggest that if the natural lactose utilization system exhibits bistability, the probability to observe it experimentally is largest in the absence of glucose. Conversely, if bistability is not observed in the natural system, increasing repressor-operator cooperativity through overexpression of LacI could be one means to drive the natural system into a regime where it may exhibit bistability.

To test these ideas, we employed a combined experimental and computational modeling approach that indicates the natural lactose system operates near, but not in, the bistable regime. Through overexpression of LacI we could observe bimodal distributions of cells in a culture, which suggests that LacI overexpression, indeed, leads to bistable induction behavior—in agreement with previous theoretical predictions. Noticeably, in the absence of bistability the stimulus-response curve of LacZ induction exhibits a pronounced maximum at intermediate lactose concentrations, which can be rationalized using our computational model.

Materials and Methods

Choice of parameter values: lactose import

To describe lactose uptake into the cell, we consider LacY-mediated influx as well as lactose excretion due to leak fluxes. The LacY permease is a galactoside:H+ symporter that utilizes the proton-motive force (PMF) to actively pump lactose and protons (1:1 stoichiometry) into the cell (18). We model the import of lactose by a saturable function of the following form (5):

| (M1) |

where VL and KL denote the turnover number of LacY and the half-saturation constant, respectively. The former has been measured in EDTA-treated cells as (19) or, rewritten in relative mass units (see Table S1), is given as follows:

The value of the half-saturation constant has been reported to depend on the PMF. In membrane vesicles, its value lies between 85 and 200 μM (19, 20). However, as the PMF decreases, the value of the half-saturation constant increases up to 14 mM (19). Because the value determined for vesicles might not be appropriate to describe the situation in cells, we left KL as a free parameter to be determined by fitting the model to experiments. In that way we obtained KL = 0.68 g/L or ≈ 2 mM, which lies halfway between 0.2 and 14 mM. To convert the unit of into g/L (as required for Eq. 1), we have used the following relation:

where is measured in μM, and mL denotes the molar mass of lactose (see Table S1).

Efflux of lactose and allolactose

Measurements of the lactose uptake rate suggest that part of the internalized lactose is again excreted by the cell due to the presence of leak fluxes (18). For the nonmetabolizable inducer TMG, an excretion rate of ke− = 60/h has been reported (21). Another study showed that more than half of the products of the LacZ-catalyzed reaction (i.e., glucose, galactose, and allolactose) can be observed in the medium in <60 min after addition of lactose (22), suggesting that the excretion rates of allolactose and TMG are comparable (although the mechanism by which allolactose leaves the cell is unknown). Due to the structural similarity between lactose and allolactose, we use the same value for the excretion rate constant (ke− = 60/h) for both substrates.

Inducer exclusion

The glucose, which is produced as part of the LacZ-mediated metabolization of lactose and allolactose, negatively regulates Lac enzyme expression by two mechanisms: 1) catabolite repression (by inactivation of cAMP synthase) and 2) inducer exclusion (through dephosphorylation of the PTS enzyme IIAGLC). According to previous studies, inducer exclusion appears to be the more dominant mechanism by which lac gene expression is downregulated (23, 24). Therefore, we decided to include this mechanism, albeit in a simplified manner. To this end, we first note that intracellularly produced glucose becomes phosphorylated by IIAGLC in a phosphotransfer reaction, during the course of which IIAGLC is dephosphorylated. Unphosphorylated IIAGLC then binds to LacY, acting as an uncompetitive inhibitor (25, 26), which suggests modifying the expression for the import rate in Eq. M1 as follows:

| (M2) |

To relate the concentration of IIAGLC to quantities in our model we assume, for simplicity, a linear relation between glucose levels and [IIAGLC] and, similarly, for the relation between glucose and intracellular lactose. The latter assumption is justified by the fact that in simulations the intracellular lactose concentration never exceeded the Km value for LacZ.

Under these assumptions, we may rewrite Eq. M2 in the following form:

| (M3) |

which describes the inhibition of the LacY-mediated import of lactose in an effective manner. In Eq. M3, the parameter Ki denotes an apparent inhibition constant to be determined by fitting the model to experiments.

Repressor-inducer interaction

Allolactose binds to each of the four subunits of the LacI repressor, which are assumed to be identical. The corresponding equilibrium constant has been measured as = 1.7 × 106 M−1 (27). Given a cell volume of Vcell = 10−15 L, the equilibrium constant can be written in terms of relative mass units as follows:

LacZ synthesis

In our model, transcription occurs if either all three operator sites are repressor-free, or if only O2 is bound by a repressor molecule. The probability for transcription is given by the expression in Eq. 6. At full induction a maximal number of five LacZ tetramers can be produced per second (28), so that VZ is given by the following:

Conversion of lactose into allolactose and glucose/galactose

Using lactose as a substrate, LacZ may either generate glucose and galactose to sustain growth or it may generate the inducer allolactose. Experiments have shown that at sufficiently low lactose concentrations, both processes occur at approximately equal rates (29) that can be described by a Michaelis-Menten rate as being of the following form:

| (M4) |

where and are given by and (30). Using that 1 Unit (U) corresponds to the amount of substrate (in μmol) that can be converted by 1 mg of protein per minute, we can rewrite in the following form:

or, in relative mass units, as

Similarly, rewriting the Michaelis-Menten constant in relative mass units yields the following:

Conversion of allolactose into glucose and galactose

LacZ can also use allolactose as a substrate (30). In that case, glucose and galactose are the main products while the reverse reaction (formation of lactose) does not seem to occur at an appreciable rate. The dynamics of this reaction is also described by a Michaelis-Menten rate of the following form:

| (M5) |

with = 49.6 U/mg and = 1.2 mM. Rewriting these parameters in terms of relative mass units yields the following:

and

In Eqs. M4 and M5, we have neglected possible competition effects that may exist between the LacZ substrates, lactose and allolactose, as they do not seem to affect the results of our study. For example, assuming competitive inhibition as done by Dreisigmeyer et al. (8) yields the same values for the estimated parameters Y, KL, and Ki as without competition.

Growth yield on lactose

For the E. coli strain NCM3722, You et al. (31) reported a growth yield in minimal medium on lactose of Y = 150 gram dry weight (gdw)/mol or Y ≈ 0.44 gdw/gL. However, in our experiments lactose is co-utilized with succinate (Fig. S3), making it difficult to evaluate the contribution of lactose utilization to the total biomass production. Due to this uncertainty, we left the growth yield Y as a free parameter to be estimated by comparing model predictions with experiments. In that way we obtained the value Y ≈ 0.092 gdw/gL, which indicates that a substantial portion of the imported lactose is, again, excreted either in the form of lactose and allolactose (as described by ke−) or in the form galactose and glucose as observed in Huber et al. (22). Because the latter two metabolites are not explicitly considered in our model, their excretion is effectively accounted for in the maintenance term ∼(1–Y) in Eq. 10.

Parameter estimation

To estimate the three free parameters in our model, Y, KL, and Ki, we have used the freely available Data 2 Dynamics software package (32). The model was simultaneously fitted to the transient lactose induction curves shown in Fig. 2 as well as to the growth curves shown in Fig. S1. To compare model predictions with the induction curves, we have assumed that the measured LacZ activity (A) is proportional to the LacZ concentration in the cell, i.e., A = a0 + a1[LacZ], where a0 accounts for basal LacZ activity due to measurement noise. We have estimated these parameters together with the three main model parameters above and obtained the following values:

which have been used to generate the plots in Fig. 2. To relate our model predictions for the cell density to the measurements shown in Fig. S1, we have used the relation 1 optical density (OD) = 5 × 1011 cells/L, i.e., 1 OD corresponds to a cell density of c = 0.15 gdw/L.

Figure 2.

Parameter estimation. Cells grown on succinate are induced with increasing amounts of lactose and the transient change in LacZ activity has been measured (symbols). Error bars represent SD from three independent experiments. The solid lines represent the best (least square) fit of the model equations ((1), (2), (3), (4), (5), (6)). The corresponding parameter values are shown in Table 2.

Computation of the two-parameter bifurcation diagram

The two-parameter bifurcation diagram in Fig. 3 C has been computed using MATCONT—a freely available software package for numerical bifurcation analysis (33). To this end, we used the external lactose concentration [Le] and the LacI overexpression factor (ρI) as independent parameters. The latter can be introduced through the parameters αi (i = 1, 2, 3), (j = 1, 2), and κ2 in the expression for PS in Eq. 6. According to the mechanistic model described in Narang (34), these parameters describe unary (α1, , κ2), binary (α2,), and ternary (α3) repressor-operator interactions and are, thus, proportional to the first, second, and third power of the LacI concentration as follows:

Figure 3.

Model predictions: nonmonotonic response and bistability. (A) For the wild-type strain (AM1) the LacZ induction curve is predicted to occur in a monostable manner, but it exhibits a pronounced maximum at [Le] ≈ 120 μM (dotted line). (B) Near the dotted line (same as in A) the LacZ synthesis rate (solid line, Eq. 6) saturates whereas the specific growth rate (dashed line, Eq. 7) begins to increase, which rationalizes the occurrence of the maximum in (A). (C) Two-parameter bifurcation diagram depicting the region (shaded area) where lac operon expression is predicted to occur in a bistable manner. (D) Sample stimulus-response curve at ρI = 40 exhibits two stable steady states (solid lines) separated by two saddle-node bifurcations (SN1 and SN2) from an unstable steady state (dashed line) at intermediate lactose concentrations. For comparison, the stimulus-response curve from (A) is shown as a thin solid line (note the logarithmic y scale in D).

Hence, we have multiplied and κ2 by ρI; α2 and by ; and α3 by to account for relative changes in the expression level of LacI repressor.

Strains, plasmids, and growth media

Strains used in this study are the reporter strain AM1 (11), carrying an additional copy of the lac promoter region including all three operator sites and controlling the expression of a LacZ′-Gfp fusion protein. By transforming AM1 with the medium copy number plasmid (ColE1 origin) pRR48c (35) encoding lacIq, we obtained the strain DZ2 with strongly elevated lacI copy number. For low increase of LacI copy number, lacI including its own promoter was PCR amplified from chromosomal DNA of LJ110 (36) and fused into the low copy vector pCS26 (∼10 copies/cell) (37) using the Gibson Assembly Cloning Kit from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA), thereby deleting the NotI fragment and hence the lux genes. This plasmid was transformed into AM1 giving rise to strain DZ3.

Strains were grown either in LB0 medium (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl) or in chemically defined phosphate-buffered minimal medium (38) with 0.2 g/L succinate. DZ2 was grown in the presence of ampicillin (10 μg/mL) and DZ3 was grown in the presence of kanamycin (25 μg/mL).

Growth conditions and media for lac operon induction experiments

For determination of lac operon induction by enzymatic assay, single colonies grown on LB0 agar plates (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl, 12 g/L agar) were inoculated for 3–5 h in LB0 liquid medium. Precultures were diluted by 1:100 in minimal medium supplemented with 0.2% (w/v) succinate and cultivated in shake flasks overnight. The overnight cultures were washed three times with minimal medium without carbon source and were used to inoculate the main cultures with an initial OD of 0.1 at 420 nm (corresponding to ∼5 × 107 cells/mL). After ∼1 h of cultivation, cell suspensions were induced by adding the corresponding lactose concentrations. Samples for β-galactosidase assays and for determination of cell density as well as supernatants were taken every 30 min.

Cultivations for microscopy analysis were conducted similarly. To ensure that lactose concentrations were not significantly depleted at the end of the cultivations, these experiments were performed with very low initial cell densities (200–500 cells/mL). This resulted in very low cell numbers also, at the end of the experiment. Cell numbers in this case were determined by plating culture aliquots on LB0 plates and counting of the colonies grown. Lactose levels at the beginning and at the end of the experiments were measured to verify that the lactose concentration did not drop below 95 or 90% of the initial concentration (Fig. S2).

To investigate hysteresis effects, we additionally differentiated our overnight cultures in uninduced and preinduced precultures. Uninduced overnight cultures were incubated in minimal medium plus 0.2% (w/v) succinate. For preinduced overnight cultures, lactose was added to 3 mM in addition to 0.2% (w/v) succinate. Overnight cultures were washed three times, and finally inoculated as described above. Samples were taken at the time points indicated. To stop gene expression at the time point of harvest, chloramphenicol was added to 25 μg/mL.

Fluorescence microscopy

To measure lac operon gene expression at the single cell level, 15–50 mL from the cultures were harvested and centrifuged for 15 min at 4500 rpm and 4°C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in the return flow thoroughly. For 50 mL, only ∼20 mL were removed and the remaining suspension was centrifuged again. The suspension was transferred into a microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged again for 10 min at 4°C and at maximum speed. The supernatant was discarded except for 50 μL. The pellet was resuspended in the rest volume. Samples were applied to the microscope slides covered with 1% agarose and the fluorescence intensity was measured with an AxioImager M1 Microscope equipped with an AxioCam MRm CCD Camera (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Monochrome photographs were taken in the fluorescence channel (excitation: BP 470/40, beamsplitter: FT495, emission: BP 525/50) and with phase contrast. Cell boundaries were determined from the phase contrast images by using the software AxioVision (Carl Zeiss). The mask generated was used for measuring GFP fluorescence in the fluorescence image. Fluorescence values were determined as the average fluorescence of the whole cell in arbitrary units. For each experiment, images of ∼300–600 cells were collected. Images were analyzed using AxioVision.

To compare the stimulus-response curves depicted in Fig. 3, A and D with the mean GFP levels computed from the fluorescence distributions in Fig. 4, we have assumed that the mean GFP level is linearly related to the LacZ concentration as

| (M6) |

where [LacZ]min ([LacZ]max) denote the minimum (maximum) of the respective LacZ stimulus-response curve. The basal GFP level, g0, as well as the dynamic range, g1, were directly obtained from the measured average GFP levels leaving the overexpression factor ρI as the only free parameter for the fit in Fig. 5 B. In that way, we have obtained the following values (Fig. 5 A): g0 = 220 au, g1 = 600 au; and (Fig. 5 B): g0 = 92 au, g1 = 78 au.

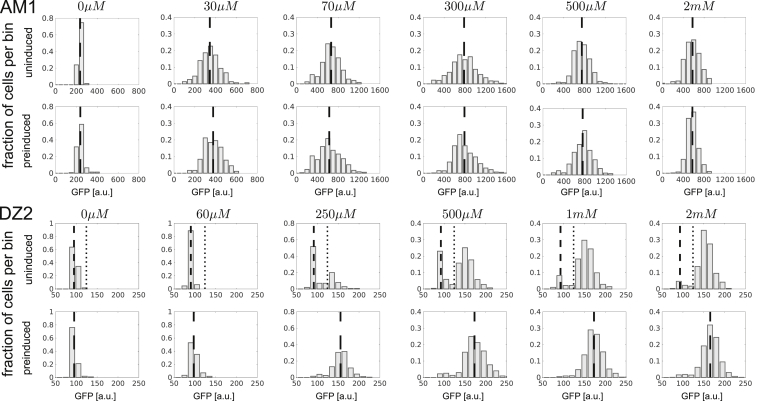

Figure 4.

Fluorescence distributions of AM1 and DZ2 after 17 h steady-state growth. Lactose concentrations are indicated above the panels. For AM1, GFP distributions are unimodal for all concentrations whereas DZ2 (uninduced) exhibits bimodal distributions in the range between 250 μM and 2 mM. Uninduced (preinduced) cells were grown in the presence of 0.2% succinate (plus 3 mM lactose) before they were resuspended into medium with defined lactose concentration as indicated above the panel. For AM1 (preinduced, uninduced) and DZ2 (preinduced), the long-dashed line indicates the mean GFP level of the total population. For DZ2 (uninduced), the short-dashed line indicates the mean GFP level of off-cells that have remained uninduced after 17 h. The dotted line marks the threshold GFP level for off-cells. Incubation time for AM1 (500 μM and 2 mM) was 10 h.

Figure 5.

Comparison of stimulus-response curves with mean GFP expression levels. In (A), symbols denote mean GFP levels as indicated by the long-dashed lines in Fig. 4 (AM1). In (B), circles correspond to mean GFP levels as indicated by the long-dashed lines in Fig. 4 (DZ2, preinduced). In contrast, square symbols denote the mean GFP levels computed from the off-cell population marked by short-dashed lines in Fig. 4 (DZ2, uninduced). Model predictions (solid lines, same as in Fig. 3, A and D) were linearly scaled according to Eq. M6 (see Materials and Methods). Error bars represent SD from at least two independent experiments.

Note that the basal GFP level is markedly different between AM1 and DZ2 , which partially explains the substantially higher dynamic range for AM1 . The remaining factor of ∼3.2 indicates that growth effects or other regulatory processes due to LacI overexpression exist that are not captured by our model.

β-galactosidase assay

For measuring the β-galactosidase activity, cells were harvested by centrifugation and the pellet was resuspended in 50 mM phosphate buffer (34 mM Na2HPO4, 16 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.2). The OD at 650 nm was adjusted to ∼0.2. Finally three aliquots were frozen at −20°C. The activity of β-galactosidase was determined similar to Miller (39). Cell suspensions were thawed on ice and 10 μL of toluene was added to 500 μL of sample. After an incubation time of 5 min at 37°C and vigorous shaking, 25 μL of 20 mM o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside was added to the mixture. The chemical reaction was stopped by the addition of 750 μL 0.2 mM Na2CO3 as soon as the sample turned yellow and the reaction time was noted. To remove cell debris, the sample was centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 rpm. Finally, absorption at 420 nm was measured against water. To calculate the β-galactosidase activity, we used the following equation:

with OD420 nm as the absorbance at 420 nm, OD650 nm as the absorbance at 650 nm, VA as the volume of the reaction mix (mL), t as the reaction time (min), ε as the extinction coefficient for ortho-Nitrophenol at (E420 = 4500/M cm), d as the length of the light path, and Ap as the amount of protein used. The amount of protein was estimated by determining the optical density at 650 nm (1 OD at 650 nm corresponds to 0.25 mg/mL protein).

Determination of lactose and succinate concentrations

Lactose and succinate concentrations in the supernatants were measured by using appropriate enzyme kits (Lactose/Galactose Assay Kit; Megazyme, Wicklow, Ireland, and Succinic Acid Kit; R-Biopharm, Darmstadt, Germany). Samples were prepared by centrifugation of 1 mL cell suspension at 13,000 rpm and 4°C for 1 min. The supernatant was collected and frozen at −20°C. The measurements were carried out in microtiter plates according to the manufacturer’s descriptions.

Results

Model choice and model description

To study the effect of growth rate-dependent dilution on the induction of the lac operon and the emergence of bistability, we employed a modified version of a model proposed by Narang and Pilyugin (5). The reasons for this choice are twofold. First, the model has been formulated in such a way that it is readily applicable to describe experiments in growing cell cultures. Specifically, it naturally incorporates the dependence of the growth rate on the Lac enzyme concentrations due to LacY-mediated uptake of lactose and LacZ-mediated lactose metabolism. Second, to describe repressor-operator interactions, the model also properly accounts for DNA-looping states such that the expression for the synthesis rate of the Lac enzymes may exhibit sufficient nonlinearity to overcome the growth rate-dependent dilution effect and, thus, may potentially allow for bistability. One limitation of the Narang-Pilyugin model is that the conversion of lactose into biomass has been assumed to be independent of LacZ. Because inducer production and lactose utilization rely on the presence of LacZ, we have included this dependence in our model, which consists of the following five ordinary differential equations (see Materials and Methods for details):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Here, all concentrations and parameters are expressed with respect to the cell dry weight (Tables 1 and 2). Equation 1 describes the LacY-mediated uptake of extracellular lactose (Le), inhibition of LacY due to inducer exclusion, and efflux of internalized lactose (Li) due to leak fluxes (18). Both terms in Eq. 1 are proportional to the cell density (c). The factor of 2 in Eq. 2 accounts for the fact that the LacZ-mediated conversion of lactose into allolactose (Al) and biomass (B) occurs at approximately equal proportions (29). The last two terms in Eq. 2 describe dilution of intracellular lactose due to excretion (ke−) or cell growth. The second term in Eq. 3 accounts for the fact that allolactose also acts as a substrate for LacZ (30). The last two terms in Eq. 3 have a similar meaning to those in Eq. 2.

Table 1.

Variable Names and Units

| Name | External Lactose Concentration | Intracellular Lactose Concentration | Intracellular Allolactose Concentration | Intracellular LacZ Concentration | Cell Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | [Le] | [Li] | [A1] | [LacZ] | C |

| Unit |

gdw = gram dry weight (3 × 10−13g) in gX, where X = L, A, Z indicates the species to which it refers.

Table 2.

Model Parameters

| Name | Value | Reference | Name | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VL | (20) | κ2 | 0.38 | (34) | |

| KL | 0.68 gL/L (≈2 mM) | estimated | α1 | 31 | (34) |

| Ki | estimated | 1420 | (34) | ||

| Vlac | (30) | α2 | 19 | (34) | |

| Klac | (30) | 322 | (34) | ||

| Val | (30) | α3 | 3 | (34) | |

| Kal | (30) | Y | estimated | ||

| VZ | (28) | ke− | (21) | ||

| Ka | (27) | μb | measured |

gX/gdw denotes gram of species X = L, A, Y, Z per gram dry weight (see Table 1).

In Eq. 4, we have the following:

| (6) |

which represents the probability for lac gene transcription (34). VZ denotes the maximal rate of protein synthesis summarizing the effects of both transcription and translation. Here, changes of the gene copy number (as a function of the growth rate) are not considered, as they are negligible for the range of growth rates considered in our study (40). The expression for PS has been derived under the assumption that transcription can occur if either all operator sites are repressor-free or if only O2 is bound by a LacI repressor. This is consistent with the finding that LacI binding to O2 has essentially no effect on the transcriptional activity (3). In Eq. 6, Ka denotes the equilibrium constant for inducer-repressor binding whereas the αi account for all operator-repressor states in which either one (α1), two (α2), or all three (α3) operator sites are occupied by LacI. The parameter describes operator-repressor states where one repressor molecule is simultaneously bound to any two of the three operator sites forming a DNA loop. Similarly, accounts for operator-repressor states in which two repressor molecules are bound to any two of the three operator sites and, in addition, one of the repressor molecules forms a DNA loop with the remaining free operator site. Finally, κ2 = K2 × LacIT denotes the equilibrium constant for LacI binding to the O2 site rescaled by the total repressor concentration (LacIT). Also, note that κ2 < α1 = κ1 + κ2 + κ3, where κi = Ki × LacIT denote the rescaled equilibrium binding constants with respect to operator site Oi. Further details concerning the derivation of the expression in Eq. 6 can be found in Narang (34).

The dynamics of LacY is not explicitly modeled because LacY and LacZ are cotranslated from the same polycistronic mRNA. Measurements of the respective translation rates have shown that, to a good approximation, the two proteins are produced in a fixed ratio of 2:1 (LacY/LacZ) (28). Assuming that LacY and LacZ are not actively degraded but only diluted by cell growth, their concentrations can be related via the following:

| (7) |

where mpY and mpZ denote the relative mass fractions of LacY and LacZ, with respect to the total cell dry weight, respectively (Table S1).

Equation 5 describes the production of biomass (B) other than that contributed by Li, A1, and LacZ. Because the synthesis of LacZ is already accounted for in Eq. 4, a corresponding term has to be subtracted from the total synthesis rate of biomass. The first term in Eq. 5 describes biomass production due to growth on succinate whereas Y denotes the growth yield on lactose. Because all intracellular concentrations are expressed in terms of relative mass units (g/gdw) the total cell dry weight is determined by the following relation:

| (8) |

By adding up (2), (3), (4), (5) and using Eq. 8, one obtains an equation for the cell density that reads as follows:

| (9) |

where the specific growth rate μ is given by the following:

| (10) |

Thus, in the absence of lactose in the external medium, the specific growth rate is determined by the basal growth rate on succinate. However, when lactose is present, μ is increased by the net rate of lactose uptake, which is given by the lactose import rate reduced by losses due to excretion and maintenance (5). Note that because μ ∼ [LacY] ∼ [LacZ], the total dilution rate of the Lac enzymes is μ × [LacY] ∼ [LacZ]2, which is the growth rate-dependent dilution effect mentioned above.

Parameter estimation

To validate the model described by (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7), (8), (9), (10), we fixed all but three parameters at their experimentally known values (Table 2). For the remaining three parameters (i.e., the growth yield on lactose (Y), the half-saturation constant for lactose import (KL), and the inhibition constant for LacY (Ki )), either no literature value has been available or a large uncertainty existed in its value (Materials and Methods). To estimate these parameters for our E. coli strain (AM1, see below) we used cells growing exponentially in minimal medium on succinate (μb = 0.33/h) and applied increasing amounts of lactose. The resulting transient changes of LacZ activity were measured together with the growth rate and subsequently used to fit the model (Figs. 2 and S1). The estimated parameter values for Y, KL, and Ki are listed together with those of the fixed parameter values in Table 2. Note that the LacY inhibition constant Ki is one order-of-magnitude smaller than the Michaelis-Menten constants (Klac and Kal) for the LacZ-catalyzed reactions, indicating that the negative feedback due to inducer exclusion becomes effective well before LacZ is saturated. The other two parameters are discussed in the Materials and Methods.

The natural lactose utilization system exhibits a nonmonotonic response curve

Having a well-parameterized model, we were first interested whether the induction of the lac operon would be predicted to occur in a monostable or in a bistable manner. As Fig. 3 A shows, the stimulus-response curve of LacZ induction is monostable. In addition, it exhibits a pronounced maximum at intermediate lactose concentrations. To understand the origin of this maximum at the level of our computational model, one has to consider that lactose is used for both LacZ induction and cell growth, and that the relative contributions of these two processes, which determine the steady state level of LacZ, vary depending on the external lactose concentration. Indeed, at low inducer concentrations, positive changes in the allolactose concentration mainly increase the LacZ synthesis rate, whereas the specific growth rate remains approximately constant (Fig. 3 B). As a result, the LacZ activity rises as a function of the external lactose concentration. However, as more lactose is pumped into the cell, all LacI binding sites eventually become occupied by inducer molecules so that the LacZ synthesis rate saturates. Any additional allolactose is either excreted or converted into glucose and galactose, which then leads to an increased growth rate. This line of reasoning is supported by direct measurement of the specific growth rate at different lactose concentrations in the medium (Fig. S2 A). Hence, at high inducer concentrations, the dilution term in Eq. 4 becomes dominant, so that increasing the extracellular lactose concentration beyond the point where the intracellular allolactose concentration becomes saturating for LacZ synthesis leads to a reduction of LacZ activity and, thereby, to a maximum in the induction curve. Note that such a nonmonotonic behavior would not be expected to occur if the lac operon is induced with gratuitous inducers such as TMG or IPTG, as they do not affect the growth rate in our model.

To test these predictions, we analyzed lac operon induction in single cells. To this end, we employed the GFP reporter strain AM1 (11), which contains one additional copy of the lac promoter-operator region (Fig. 1). To keep the O2 binding site (in addition to O1 and O3), the first codons of lacZ were fused to gfpmut3.1, resulting in a LacZ-GFP fusion protein, which has been integrated at the attachment site of phage80. As only one additional promoter-operator region was inserted, we regard lac operon regulation to be basically unchanged in AM1 compared to the wild-type.

The AM1 strain was tested for induction of the lac operon after growth in batch cultures with 0.2% succinate by adding varying levels of lactose ranging from 0 to 2 mM. We have chosen succinate as a background substrate for two reasons. First, it allows for growth of induced as well as uninduced cells independent of the induction status of the lac operon. Second, succinate does not interfere significantly with lac operon induction as it does not elicit catabolite repression or inducer exclusion. We have also checked that both substrates are taken up concurrently (Fig. S3). To ensure that the lactose concentration in the medium would remain approximately constant during the subsequent growth phase, cells were inoculated to a very low cell density (≤10−5 OD), similar to what was done in Ozbudak et al. (10). In this way, we could achieve nearly steady-state conditions for up to 17 h of growth (Fig. S2 B). The minimal length of the growth phase has been chosen based on model simulations suggesting that lac induction would reach a steady state after 5–10 h, depending on the lactose concentration in the medium. At the end of the growth phase (10–17 h), cells were sampled and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy.

As shown in Fig. 4 (AM1), the resulting single-cell GFP distributions were unimodal for all lactose concentrations tested, which confirms previous reports by other groups (10, 41). As the extracellular lactose concentration is increased the population-averaged GFP level first rises gradually up to a maximum at [Le] ≈ 150 μM, from which it gradually declines as [Le] is further increased. Assuming a linear relationship between LacZ activity and GFP expression, the measured average GFP levels can be mapped to the stimulus-response curve depicted in Fig. 3 A (Materials and Methods). The resulting curve (Fig. 5 A) has a similar shape to the measured GFP levels, supporting our model prediction that the LacZ activity exhibits a maximum at intermediate lactose concentrations.

To exclude hysteresis effects, we have repeated the induction experiments with preinduced precultures. To this end, overnight cultures were grown in the presence of 3 mM lactose before they were washed, diluted, and resuspended into fresh medium containing the same lactose concentration as used before. However, we could not observe any qualitative difference between precultures grown in the presence or in the absence of lactose, both at the level of the GFP distributions (Fig. 4, AM1) as well as for the average GFP levels (Fig. 5 A). Together these observations support previous results according to which the natural lactose utilization system operates in the monostable regime.

The natural lactose utilization system operates close to a bistable region

The finding that the LacZ induction curve is monostable indicates that in the natural lactose utilization system, the cooperativity of repressor-operator interactions due to DNA-looping is not sufficient to overcome the attenuating effect of the growth rate-dependent dilution of the Lac enzymes (5). However, it has been argued that the cooperativity generated by DNA-looping can be substantially increased through overexpression of LacI repressor (34). In addition, lacI overexpression reduces the basal LacZ expression level which, according to the Savageau design principle (6), should also favor the emergence of bistability. To test these predictions, we first computed a two-parameter bifurcation diagram with the external lactose concentration on the x axis and the fold change overexpression level of LacI on the y axis (see Materials and Methods). The resulting diagram indicates that the natural lac system (ρI = 1) operates close to a bistable region (Fig. 3 C, shaded region), which extends from ρI ≳ 3.5 and [Le] ≳ 10 μM toward higher lactose concentrations. For low overexpression factors, the bistable region is extremely narrow, making it unlikely to observe bistability experimentally. However, as ρI increases beyond 20 the bistable region substantially increases as well. For example, at ρI = 40, two stable steady states coexist in the region 35 μM ≤ [Le] ≤ 811 μM (Fig. 3 D). As expected due to the increased lac gene repression, the basal LacZ expression level is substantially reduced compared to AM1. However, the nonmonotonic behavior of the stimulus-response curve is still visible in the upper stable branch of the bistable induction curve, albeit to a much lesser extent.

To experimentally test whether increasing the repressor level would lead to a bistable lac operon induction, we transformed AM1 with plasmid pRR48. This plasmid carries the lacIq allele (35) and the ColE1 replicon (∼20–50 copies per cell) and hence is expected to elevate the LacI copy number substantially. In contrast to AM1, no induction could be achieved with lactose concentrations below 250 μM, whereas the same concentration was sufficient to fully induce AM1 (Fig. 4, AM1). In addition, the dynamic range of lac operon expression as well as the maximal growth rate at saturating lactose concentrations appeared to be reduced (Table 3). Comparable results were obtained by Bhogale et al. (42) for induction of a similar strain with TMG. For lactose concentrations equal to or larger than 250 μM, we observed history-dependent induction behavior as it typically occurs in connection with bistability (Fig. 4, DZ2). Whereas cells from precultures grown in the absence of lactose exhibited bimodal distributions in the range between 250 μM and 2 mM, the distributions of cells from precultures grown in the presence of lactose were found to be unimodal. Moreover, as the lactose concentration is increased, the fraction of cells in the uninduced state (below the dotted line) gradually decreased while, at the same time, the fraction of induced cells increased accordingly.

Table 3.

Comparing AM1 and DZ2

| AM1 | DZ2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Specific growth rate μ at [Le] = 0 μM | 0.33/h | 0.2/h |

| Specific growth rate at highest lactose concentration | 0.81/h ([Le] = 4 mM) | 0.42/h ([Le] = 2 mM) |

| Dynamic range (〈ΔGFP〉) | 2.73 | 0.85 |

〈ΔGFP〉 = (〈GFP〉max − 〈GFP〉min)/〈GFP〉min (see Eq. M6). Growth rates were interpolated from cell numbers (determined by plating) at the beginning and at the end of a 17 h experiment.

We expected that the history-dependent effects at the distribution level would result in a hysteresis curve similar to that in Fig. 3 D. We reasoned that the mean GFP level computed from preinduced precultures should coincide with the upper stable branch of the hysteresis curve, whereas the lower stable branch should be identified with the mean GFP level of off-cells (Fig. 4, DZ2, uninduced), i.e., cells that have not yet been induced after 17 h. One inherent uncertainty of such a procedure comes from the fact that the exact location of the bifurcation points (denoted by SN1 and SN2 in Fig. 3 D) cannot be directly inferred from the GFP distributions in Fig. 4. However, one would expect that the left bifurcation point (SN1) lies below the concentration for which bimodal distributions first appear ([Le] = 250 μM in our case). The reason is that the transition to the induced state is a stochastic process driven by fluctuations in the operator occupancy of the LacI repressor (42, 43). To become induced, fluctuations have to drive the cells beyond the unstable branch of the hysteresis curve (Fig. 3 D, dashed line), which typically occurs only if the inducer concentration is sufficiently increased beyond the left bifurcation point (10). Also, the location of bifurcation points might be shifted in the presence of fluctuations (44). For example, in the case of an autoactivating gene circuit, it has been shown that noise has a stabilizing effect on the lower stable steady state so that the right bifurcation point is moved toward higher values of the bifurcation parameter (45). Applied to our situation, this suggests that the location of the right bifurcation point (SN2) is actually below 1–2 mM, assuming that the range of bistability as predicted by our deterministic model is narrower than that observed experimentally.

To compare the hysteresis curve computed from the model with the mean GFP levels (Fig. 5 B), we assumed a linear relation between LacZ activity and GFP expression, leaving the overexpression factor ρI as the only free parameter (Materials and Methods). Whereas the shape of the upper stable branch of the hysteresis curve was largely insensitive to the particular value of ρI, the extent of the bistable region was highly variable, extending from 31 μM ≤ [Le] ≤ 353 μM at ρI = 30 to 39 μM ≤ [Le] ≤ 2000 μM at ρI = 50 (Fig. S4). Hence, both values would be consistent with the expectation that the left bifurcation point lies below [Le] = 250 μM. However, as ρI increases, the maximum in the response curve becomes less pronounced. Best agreement with the upper stable branch is obtained for ρI = 40 (Fig. 5 B). Here, the response curve exhibits a mild decline at high lactose concentrations whereas the right bifurcation point (SN2) lies below 1 mM. Note, however, that the estimate of ρI is only approximate, and might be affected by further factors, e.g., a spatially inhomogeneous distribution of LacI repressor inside the cell (46).

A lower overexpression factor leads to a downshift of the bistable regime

According to the two-parameter bifurcation diagram depicted in Fig. 3 C, lowering the LacI overexpression factor ρI should narrow the bistable region and shift it toward lower lactose concentrations. To test this model prediction, we constructed a second strain denoted by “DZ3”. In that strain lacI (with its natural promoter) was cloned onto a low copy number plasmid, so that (compared to DZ2) a moderate elevation of the LacI copy number of 5–10 was expected. According to Fig. 3 C, a 10-fold increase of the LacI copy number should result in bistability in the range 20 μM ≤ [Le] ≤ 40 μM. However, at such low concentrations we have only observed unimodal fluorescence distributions independent of the growth history of the population. Instead, bimodal distributions were observed for uninduced cells in the range between 80 μM ≤ [Le] ≤ 100 μM (Fig. S4). The corresponding value for the LacI overexpression factor ρI ≈ 17 (Fig. 3 C) indicates that in DZ3, the LacI copy number was slightly larger (∼2×) than expected. Together, these results support the model prediction that lowering the overexpression factor narrows the bistable regime, and shifts it toward lower inducer concentrations.

Discussion

The all-or-none induction of the E. coli lac operon has been a paradigmatic example for bistability in gene regulatory networks for many decades. However, so far bistability has been experimentally demonstrated only for induction with gratuitous inducers such as TMG (9, 10, 47) or IPTG (11, 12), but not for induction with the natural inducer lactose. In fact, based on theoretical analysis of the lac circuit architecture, Savageau (6) argued that bistability is unlikely to occur in the natural lactose utilization system, but that overexpression of the LacI repressor would favor the emergence of bistability.

In this study, we have tested and confirmed this prediction by combining single cell analysis with deterministic computational modeling. To this end, we analyzed lac operon induction by lactose in E. coli cells, both in a wild-type-derived GFP-containing reporter strain (AM1) and in mutants overexpressing the LacI repressor to different extents (DZ2 and DZ3). In this sense, our experiments can be viewed as opposite to those conducted by Ozbudak et al. (10), who showed that TMG-induced lac operon expression can be driven from a bistable into a monostable regime by successive dilution of LacI repressor. Guided by the computational model, our results support the view that lac operon induction in the wild-type strain is graded (monostable) rather than all-or-none (bistable), which is consistent with the Savageau design principle as well as with previous experimental analysis of lactose-induced lac operon expression in E. coli (41).

In contrast, GFP expression in DZ2 and DZ3 was bimodal after 17 h of steady-state growth. According to our model, the range of lactose concentrations over which bistability is predicted to occur should become larger and shift toward higher lactose concentrations as the LacI overexpression factor increases. Qualitatively, this is indeed what we have observed: for DZ2 (strong lacI overexpression), we obtained bimodal distributions in the range of lactose concentrations between 250 μM and 2 mM, whereas DZ3 (moderate lacI overexpression) yielded bimodal distributions in the range between 80 μM and 100 μM. However, especially in DZ2, both the growth rate at saturating lactose levels and the dynamic range of GFP expression were substantially reduced compared to AM1 (Table 3). In addition, induction by lactose appears to be a fast process occurring within only approximately two cell generations (Fig. 2). Hence, at least at the conditions tested, with succinate as an alternative carbon source, one would not expect a significant growth advantage for E. coli to operate the lactose utilization system in the bistable regime following, for example, a bet-hedging strategy. The latter is believed to be beneficial if the response rate of a system is comparable to or lower than the rate with which environmental changes occur (48).

Possible mechanisms behind the nonmonotonic response

Even though the LacZ induction curve of AM1 is monostable, it exhibits a pronounced maximum at intermediate lactose concentrations at ∼150 μM (Figs. 3 A and 5 A). Interestingly, a similar maximum in the response curve of LacZ expression has recently been observed by Afroz et al. (41), although no attempt has been made to explain this effect. Our model-based analysis suggests that the maximum arises from the saturation of LacI repressor by allolactose at low inducer concentrations and the growth rate-dependent dilution effect, which provides a negative feedback at high inducer concentrations (Fig. 3 B). Clearly, such a nonmonotonic response cannot occur with gratuitous inducers such as TMG and IPTG, as these do not increase the growth rate. To obtain a maximum at intermediate lactose levels, one also has to require that the inducer concentration, which leads to saturation of the LacI repressor, should be low enough not to saturate the catabolic enzymes such that increasing the lactose level beyond the repressor saturation point can still increase the growth rate—a condition that seems to be satisfied for the lactose utilization system. Moreover, it seems likely that this condition also holds in other repressor-mediated sugar uptake systems, as the number of repressor molecules is typically much lower than that of the catabolic enzymes.

The Lac protein expression maximum might also be reasoned in the connection between lactose metabolism and the glucose-PTS, which provides an alternative negative feedback mechanism to reduce lac gene expression at high lactose concentrations. Indeed, when lactose uptake rates are low, only small amounts of intracellular glucose are produced from the LacZ-mediated cleavage of lactose into galactose and glucose. However, this small amount of glucose might not be sufficient to provoke significant dephosphorylation of the PTS proteins. The situation becomes different at [Le] ≈ 150 μM when enough allolactose is produced to fully saturate LacI so that further increases of the extracellular lactose concentration lead to an increased production of intracellular glucose that can be phosphorylated by the PTS (49, 50). Concomitantly, the concentration of dephosphorylated IIAGlc increases, thereby mediating inducer exclusion through inhibitive binding to LacY (23). The same effect will also promote catabolite repression by reducing the availability of the cAMP•CRP complex, as phosphorylated IIAGlc is necessary to activate adenylate cyclase (13). In our model we have only considered inducer exclusion as the more dominant effect in downregulating lac gene expression at high inducer concentrations (23, 24). However, the maximum in the LacZ response curve persists even in the absence of inducer exclusion (Ki → ∞), suggesting that both inducer exclusion and catabolite repression are not necessary to explain the occurrence of the maximum.

At present, we can only speculate about the physiological significance of the observed maximum in the Lac enzyme expression. An obvious purpose would be to avoid unnecessary LacZ and LacY synthesis when extracellular lactose levels become too high and hence to balance lactose uptake rates with central metabolism. In this respect it is interesting to note that a similar maximum in the induction curve has been observed for growth on N-acetylglucosamine, whose uptake is also mediated by a PTS (41). In contrast, uptake of non-PTS substrates (such as galactose) exhibited a monotonous induction curve, which may suggest that the PTS-mediated feedback on the expression of catabolic enzymes might be a general mechanism to limit the expression of these enzymes at high substrate concentration.

Author Contributions

D.Z. performed and evaluated wet lab experiments. D.S. was involved in model setup and data analysis. R.S. designed and performed the modeling work and wrote the manuscript. K.B. designed and performed wet lab experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrea Focke for excellent technical assistance.

D.Z. and the experimental work have been funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through priority program No. 1617.

Editor: Nathalie Balaban.

Footnotes

Dominique Zander and Daniel Samaga contributed equally to this work.

Five figures and one table are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)30387-9.

Contributor Information

Ronny Straube, Email: rstraube@mpi-magdeburg.mpg.de.

Katja Bettenbrock, Email: bettenbrock@mpi-magdeburg.mpg.de.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Mueller-Hill B. deGruyter; Berlin, Germany: 1996. The Lac Operon: A Short History of a Genetic Paradigm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adhya S. The lac and gal operons today. In: Lin E.C.C., Lynch A.S., editors. Regulation of Gene Expression in Escherichia coli. Chapman & Hall; Boston, MA: 1996. pp. 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oehler S., Eismann E.R., Müller-Hill B. The three operators of the lac operon cooperate in repression. EMBO J. 1990;9:973–979. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffith J.S. Mathematics of cellular control processes. II. Positive feedback to one gene. J. Theor. Biol. 1968;20:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(68)90190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narang A., Pilyugin S.S. Bistability of the lac operon during growth of Escherichia coli on lactose and lactose+glucose. Bull. Math. Biol. 2008;70:1032–1064. doi: 10.1007/s11538-007-9289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savageau M.A. Design of the lac gene circuit revisited. Math. Biosci. 2011;231:19–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Hoek M.J.A., Hogeweg P. In silico evolved lac operons exhibit bistability for artificial inducers, but not for lactose. Biophys. J. 2006;91:2833–2843. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.077420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dreisigmeyer D.W., Stajic J., Wall M.E. Determinants of bistability in induction of the Escherichia coli lac operon. IET Syst. Biol. 2008;2:293–303. doi: 10.1049/iet-syb:20080095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novick A., Weiner M. Enzyme induction as an all-or-none phenomenon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1957;43:553–566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.43.7.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozbudak E.M., Thattai M., van Oudenaarden A. Multistability in the lactose utilization network of Escherichia coli. Nature. 2004;427:737–740. doi: 10.1038/nature02298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marbach A., Bettenbrock K. lac operon induction in Escherichia coli: systematic comparison of IPTG and TMG induction and influence of the transacetylase LacA. J. Biotechnol. 2012;157:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maloney P.C., Rotman B. Distribution of suboptimally induces -D-galactosidase in Escherichia coli. The enzyme content of individual cells. J. Mol. Biol. 1973;73:77–91. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Postma P.W., Lengeler J.W., Jacobson G.R. Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 1993;57:543–594. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.543-594.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhlman T., Zhang Z., Hwa T. Combinatorial transcriptional control of the lactose operon of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:6043–6048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606717104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yildirim N., Mackey M.C. Feedback regulation in the lactose operon: a mathematical modeling study and comparison with experimental data. Biophys. J. 2003;84:2841–2851. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70013-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santillán M., Mackey M.C., Zeron E.S. Origin of bistability in the lac operon. Biophys. J. 2007;92:3830–3842. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Hoek M., Hogeweg P. The effect of stochasticity on the lac operon: an evolutionary perspective. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Booth I.R., Mitchell W.J., Hamilton W.A. Quantitative analysis of proton-linked transport systems. The lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Biochem. J. 1979;182:687–696. doi: 10.1042/bj1820687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright J.K., Riede I., Overath P. Lactose carrier protein of Escherichia coli: interaction with galactosides and protons. Biochemistry. 1981;20:6404–6415. doi: 10.1021/bi00525a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright J.K., Overath P. Purification of the lactose:H+ carrier of Escherichia coli and characterization of galactoside binding and transport. Eur. J. Biochem. 1984;138:497–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb07944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kepes A. Kinetic studies on galactoside permease of Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1960;40:70–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(60)91316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huber R.E., Lytton J., Fung E.B. Efflux of β-galactosidase products from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1980;141:528–533. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.2.528-533.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inada T., Kimata K., Aiba H. Mechanism responsible for glucose-lactose diauxie in Escherichia coli: challenge to the cAMP model. Genes Cells. 1996;1:293–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.24025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogema B.M., Arents J.C., Postma P.W. Inducer exclusion by glucose 6-phosphate in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;28:755–765. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seok Y.J., Sun J., Peterkofsky A. Topology of allosteric regulation of lactose permease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:13515–13519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sondej M., Weinglass A.B., Kaback H.R. Binding of enzyme IIAGlc, a component of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system, to the Escherichia coli lactose permease. Biochemistry. 2002;41:5556–5565. doi: 10.1021/bi011990j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barkley M.D., Riggs A.D., Burgeois S. Interaction of effecting ligands with lac repressor and repressor-operator complex. Biochemistry. 1975;14:1700–1712. doi: 10.1021/bi00679a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kennell D., Riezman H. Transcription and translation initiation frequencies of the Escherichia coli lac operon. J. Mol. Biol. 1977;114:1–21. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huber R.E., Kurz G., Wallenfels K. A quantitation of the factors which affect the hydrolase and transgalactosylase activities of β-galactosidase (E. coli) on lactose. Biochemistry. 1976;15:1994–2001. doi: 10.1021/bi00654a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huber R.E., Wallenfels K., Kurz G. The action of β-galactosidase (Escherichia coli) on allolactose. Can. J. Biochem. 1975;53:1035–1038. doi: 10.1139/o75-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.You C., Okano H., Hwa T. Coordination of bacterial proteome with metabolism by cyclic AMP signalling. Nature. 2013;500:301–306. doi: 10.1038/nature12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raue A., Schilling M., Timmer J. Lessons learned from quantitative dynamical modeling in systems biology. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dhooge A., Govaerts W., Kuznetsov Y. MATCONT: a MATLAB package for numerical bifurcation analysis of ODEs. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 2003;29:141–164. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Narang A. Effect of DNA looping on the induction kinetics of the lac operon. J. Theor. Biol. 2007;247:695–712. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Studdert C.A., Parkinson J.S. Insights into the organization and dynamics of bacterial chemoreceptor clusters through in vivo crosslinking studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15623–15628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506040102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kremling A., Bettenbrock K., Gilles E.D. The organization of metabolic reaction networks. III. Application for diauxic growth on glucose and lactose. Metab. Eng. 2001;3:362–379. doi: 10.1006/mben.2001.0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bjarnason J., Southward C.M., Surette M.G. Genomic profiling of iron-responsive genes in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium by high-throughput screening of a random promoter library. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:4973–4982. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.16.4973-4982.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanaka S., Lerner S.A., Lin E.C. Replacement of a phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase by a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-linked dehydrogenase for the utilization of mannitol. J. Bacteriol. 1967;93:642–648. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.2.642-648.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller J.H. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor Press, NY: 1992. A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klumpp S., Zhang Z., Hwa T. Growth rate-dependent global effects on gene expression in bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:1366–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Afroz T., Biliouris K., Beisel C.L. Bacterial sugar utilization gives rise to distinct single-cell behaviours. Mol. Microbiol. 2014;93:1093–1103. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhogale P.M., Sorg R.A., Berg J. What makes the lac-pathway switch: identifying the fluctuations that trigger phenotype switching in gene regulatory systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:11321–11328. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi P.J., Cai L., Xie X.S. A stochastic single-molecule event triggers phenotype switching of a bacterial cell. Science. 2008;322:442–446. doi: 10.1126/science.1161427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scott M., Hwa T., Ingalls B. Deterministic characterization of stochastic genetic circuits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7402–7407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610468104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weber M., Buceta J. Stochastic stabilization of phenotypic states: the genetic bistable switch as a case study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuhlman T.E., Cox E.C. Gene location and DNA density determine transcription factor distributions in Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2012;8:610. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohn M., Horibata K. Inhibition by glucose of the induced synthesis of the beta-galactoside-enzyme system of Escherichia coli. Analysis of maintenance. J. Bacteriol. 1959;78:601–612. doi: 10.1128/jb.78.5.601-612.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thattai M., van Oudenaarden A. Stochastic gene expression in fluctuating environments. Genetics. 2004;167:523–530. doi: 10.1534/genetics.167.1.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nuoffer C., Zanolari B., Erni B. Glucose permease of Escherichia coli. The effect of cysteine to serine mutations on the function, stability, and regulation of transport and phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:6647–6655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bettenbrock K., Fischer S., Gilles E.-D. A quantitative approach to catabolite repression in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:2578–2584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.