Abstract

Oil palm is the most productive oil crop in the world and composes 36% of the world production. However, the molecular mechanisms of hybrids vigor (or heterosis) between Dura, Pisifera and their hybrid progeny Tenera has not yet been well understood. Here we compared the temporal and spatial compositions of lipids and transcriptomes for two oil yielding organs mesocarp and endosperm from Dura, Pisifera and Tenera. Multiple lipid biosynthesis pathways are highly enriched in all non-additive expression pattern in endosperm, while cytokinine biosynthesis and cell cycle pathways are highly enriched both in endosperm and mesocarp. Compared with parental palms, the high oil content in Tenera was associated with much higher transcript levels of EgWRI1, homolog of Arabidopsis thaliana WRINKLED1. Among 338 identified genes in lipid synthesis, 207 (61%) has been identified to contain the WRI1 specific binding AW motif. We further functionally identified EgWRI1-1, one of three EgWRI1 orthologs, by genetic complementation of the Arabidopsis wri1 mutant. Ectopic expression of EgWRI1-1 in plant produced dramatically increased seed mass and oil content, with oil profile changed. Our findings provide an explanation for EgWRI1 as an important gene contributing hybrid vigor in lipid biosynthesis in oil palm.

Introduction

Hybrid vigor, or heterosis, refers to the superior performance of hybrid progeny relative to their inbred parents1–4. Heterosis in plants of diverse species is associated with many superior agronomic characteristics, including larger plant stature, increased biomass, growth rate, grain yield, and tolerance to abiotic stresses. These heterosis is frequently found in cereal crops such as maize (Zea mays) and rice (Oryza sativa), mainly as hybrids, and many other crops including bread wheat (Triticum aestivum), upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), and few in oil crop e.g. canola or rape seed (Brassica napus), are grown as allopolyploids. Heterosis has been widely used by breeding program to improve crop yield and resistance significantly. Despite being widely exploited for many decades, the mechanisms underlying heterosis still remain poorly understood esp. for high energy content oil crop5. Most of the earlier efforts focused on genetic analysis of the modes of gene action. Many observations point to the likelihood that the diverse genetic and molecular mechanisms at a large number of genes are responsible for hybrid vigor in any heterotic parental pair. A few classical genetic concepts were previously considered to explain hybrid vigor and the most accepted hypothesis are dominance, the over-dominance and epistatic effects6. Recently, it was suggested that a combination of different genetic principles might best explain the mechanism of hybrid vigor7,8. However, identifying the specific molecular mechanisms that are responsible for the phenotypic differences between the hybrid and inbred parents remains a challenge, although successes in other plants have been achieved, such as the demonstration of heterosis in yield by the effects of a single gene Single Flowering Truss in tomato9.

In recent years, study of heterosis has been approached to the level of the gene products such as transcripts and the regulation of their expression. Available technologies have enabled addressing the biological concerns at the genomic scales, the proteome, the metabolome and especially transcriptome. Various mechanisms may be involved in RNA expression regulation including genetic or epigenetic factors, such as chromosomal structure, DNA sequence diversity, and DNA methylation6.

The use of hybrid have been highly promoted in oil crops yield including rape seed10–12, soybean13 and most important oil palm14. Oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq) originates from tropical Africa and it was imported into South Asia where industrial plantations started about 100 years ago. Oil palm is now the most productive oil (triacylglycerol, TAG) crop in the world with an average oil yield of 5–7 tons per hectare15 and contributes about 36% of world oil production. In addition to triglycerides, palm oil also contains high levels of carotenoids and vitamin E, which are believed to counter the ravages of chronic diseases such as heart disease and cancer and to delay aging15.

Almost all modern, commercial planting material consists of Tenera palms by crossing of Dura and Pisifera. Crossing Dura and Pisifera to give the hybrid progeny fruit type improved partition of dry matter within the fruit, resulting in a more than 30% increase in oil yield per tree. With the progress of genome sequencing project for parental Dura16 and Pisifera15, it is possible to underpin the molecular mechanisms of hybrid vigor of Tenera. Therefore, this model will be used to understand heterosis in lipid biosynthesis for oil crop. A few efforts of genome-wide gene identification for oil biosynthesis have been done14–19. Despite its obvious scientific and economic interest, literature and molecular resources available for oil palm remain elusive, esp. for the molecular mechanism of hybrid vigor in oil yield is still scarce. Aside from the SHELL gene that developmentally controls cell type differentiation20, the heterosis in lipid biochemical synthesis and the molecular clues are largely unknown. Furthermore, the chemical and biochemical basis of oil yield heterosis need to be further characterized.

Presently, knowledge of TAG accumulation in plants is mostly based on studies of oil seeds. Sucrose as the main source of carbon for storage oil synthesis in higher plants, is converted to pyruvate via glycolysis in non-green tissues. Pyruvate is the main precursor for the acetyl-CoA molecules destined to fatty acid synthesis. Plastid pyruvate kinase (PK), pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), and acetyl-CoA carboxylase are considered as key enzymes for fatty acid synthesis and are regulated by transcription factors in oil seeds, including WRINKLED1 (WRI1)21–26.

We have recently identified some candidate gene responsible for tree height in oil palm27. We also sequenced Dura genome and did resequencing on elites’ trees16. With the whole genome sequence availability, we here try to globally survey the transcriptome of the two inbred lines Dura and Pisifera in comparison to their F1-progeny Tenera in an unbiased approach via RNA-seq. To identify features specific to high oil production in non-seed tissues such as oil palm mesocarp, we first identified the key lipid biosynthesis stage and generated several billion reads for the mesocarp. At the same time, we did parallel work for seed part of the endosperm. By choosing the particular stages, we intended to identify transcriptional patterns and regulators possibly determining the processes leading to heterosis for the lipid traits. Moreover, we carried out transgenic analysis to identify candidate key genes to be responsible for hybrid vigor in oil biosynthesis of oil palm. The focus of this temporal and comparative analysis was to gain insight into factors responsible for this dramatic difference in carbon partitioning. In addition, a better understanding of oil accumulation in fruits may present strategies for engineering oil accumulation in other vegetative tissues.

Results

Hybrid vigor in lipid biosynthesis in oil palm

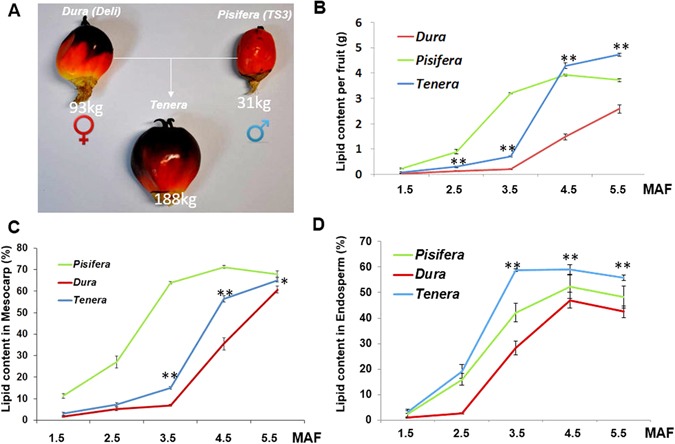

As an initial step to know whether there is hybrid vigor of lipid biosynthesis in oil palm, we firstly performed the analysis for the fertile fruit yield per tree per year. Figure 1A indicates that fruit biomass amount has clear heterosis over both of parents as shown by a much higher fruit biomass amount produced in Tenera than parental oil palms Dura and Pisifera. Due to extremely low fertile fruit ratio for Pisifera (only less 10% VS 70% for Dura and Tenera), the low fruit yield palm Pisifera is not commercially used in oil palm plantation except to provide pollen for generating the hybrid progeny Tenera. Further analysis on key lipid traits, for example lipid content per fruit (Fig. 1B), lipid content in mesocarp and endosperm (Fig. 1C and D), strongly suggest that Tenera has heterosis in lipid related traits, including heterosis over both of parents in trait of lipid yield per fruit, and heterosis over previous used variety Dura in traits of lipids content in both lipid yield tissues (mesocarp and endosperm) as indicated in final mature fruit stages (5.5 months after fertilization). Mesocarp of Pisifera commences rapid lipid biosynthesis and accumulation at very early stage, as highly as 10% of total lipid content at 1.5 months after fertilization (MAF), 2 months ahead of Tenera, which is one month ahead of Dura at 4.5 MAF (Fig. 1C). Microscopy of 4.5 MAF oil palm mesocarp showed, most notably, cells with numerous and more obvious oil droplets were observed in Tenera than in Dura (Supplementary Figure S1A and B). There is no obvious cell size difference between mesocarp of Dura and Tenera (Supplementary Figure S1A and B).

Figure 1.

Heterosis in lipid biosynthesis observed in Tenera crossed by Pisifera and Dura. (A) Fruits of three African oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) varieties, Dura (Deli), Pisifera (TS3), and the hybrid progeny tree (#53). Mean total fertile fruit weight per year (kilogram) per tree was recorded below of each variety. Yield data of 4th and 5th years after planting were analyzed. (B) Lipid content for fruit of Dura, Pisifera and Tenera during fruit development stages. Fruit developmental stages were recorded as Months after Fertilization, MAF. Values are mean total lipid amount of mesocarp and endosperm (gram) ± SD (n = 6) (Student’s t-test). Asterisks in all panels indicate significant differences between Tenera and Dura (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). (C) Mesocarp lipid content of Dura, Pisifera and Tenera. Values are mean total lipid amount of mesocarp (% dry weight) ± SD (n = 3) (Student’s t-test). (D) Endosperm lipid content of Dura, Pisifera and Tenera. Values are mean total lipid amount of endosperm (% dry weight) ± SD (n = 3) (Student’s t-test).

Similarly, heterosis is also found in endosperm. Earlier rapid lipid biosynthesis is taken place in endosperm of Tenera and lipid content in endosperm was also found to be much higher in Tenera than in Dura (Fig. 1D). Consistent with a lipid content drop in late stage of endosperm, the secondary cell wall was enhanced (Supplementary Figure S1C), as compared with early stage, indicating carbon redistribution in endosperm in later developing stage (Supplementary Figure S1D). By further detailed dissecting of 5 different stages ripening fruits, key periods for rapid lipid biosynthesis were identified as 3.5 MAF for mesocarp and 2.5 MAF for endosperm (Fig. 1C and D). We then used RNAseq samples of these five stages from Dura and Tenera to further underpin how lipid traits heterosis happens in oil palm hybrid.

Transcriptome profiling analysis

In this study, 24 samples, around 20 million RNA seq reads per sample, with 101 bp pair-end, were obtained for 5 stages of three oil palm mesocarp and 3 stages of three oil palm endosperms respectively (Supplementary Dataset S1). After de-novo assembly of these reads, 96,062 isoforms and 59,078 unigenes, with total 106,097,832 bp and GC content of 44.43% were identified. The N50 is 1,884 bps. 41.7% of genes were highly similar (BLASTX E-value < 1e-3) to Arabidopsis thaliana proteins. Contigs were annotated on the basis of Arabidopsis thaliana proteins since it is by far the best-annotated proteome among the plant kingdom.

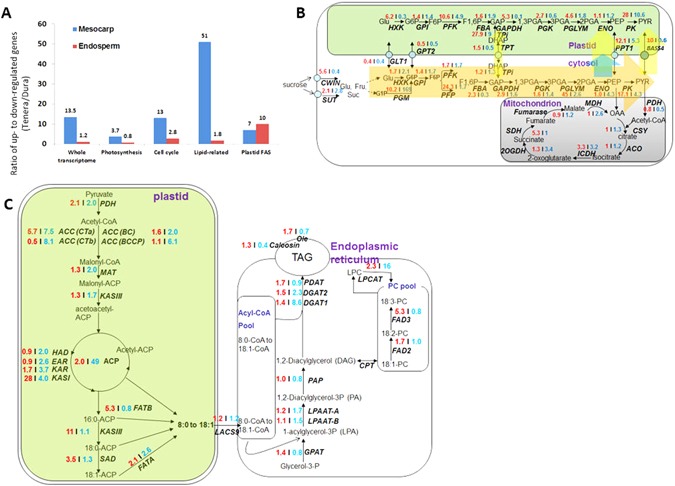

We have identified the key periods for rapid lipid biosynthesis as 3.5 MAF for mesocarp and 2.5 MAF for endosperm (Fig. 1). Here we focused on these two stages for comparative transcriptome analysis to understand the molecular basis of lipid heterosis in oil palm. Astonish difference was identified between mesocarps of Dura and Tenera, as there is a much higher ratio (13.5:1) of upregulated expression gene than downregulated expression gene (Fig. 2A), from whole transcriptome view as a basis of 59,078 genes in total. Intriguingly, compared with other categories such as photosynthesis and cell cycle, it is clear that the lipid-related categorized genes are highly enriched in unregulated genes as indicated by the ratio of up-regulated to down-regulated genes as 51, giving a good explanation why Tenera has heterosis in lipid related traits.

Figure 2.

Transcriptome pattern differs between two oil biosynthesis tissues in oil palm. (A) The ratio of up- to down-regulated genes when compared the transcription level of Tenera against Dura in mesocarp and endosperm. The gene expression level of their respective key stage (2.5 MAF for endosperm, 3.5 MAF for mesocarp) were used to compare. Assumed at least 2 folds change as up- or down-regulated genes. Whole transcriptome and some specific categorized pathways are listed out. Plastid FAS refers to the pathway of fatty acid synthesis in plastid. Noticed that genes of lipid related or plastid FAS are highly upregulated in mesocarp and endosperm of Tenera respectively. (B) Transcripts patterns for enzymes involved in glysolysis reactions for Dura and Tenera. Values in red indicate the fold increase in reads of mesocarp of Tenera to that of Dura at 3.5 MAF. Values in blue indicate the fold increase in reads of endosperm of Tenera to that of Dura at 2.5 MAF. Samples collected from different tissues for Dura, Pisifera and Tenera (#53) were used for transcriptome analysis. Orange arrow indicates the cytosolic glycolytic process is the major carbon flow increased in Tenera compared with Dura both in mesocarp and endosperm, as deduced by the fold increase in reads. Light yellow arrows indicate the major increased cytosol-to-plastid carbon flow for mesocarp. Light blue arrow indicates the major increased cytosol-to-plastid carbon flow for endosperm. (C) Transcripts patterns for enzymes involved in plastidial and extraplasidial reactions for Dura and Tenera. Values in red indicate the fold increase in reads of mesocarp of Tenera to that of Dura at 3.5 MAF. Values in blue indicate the fold increase in reads of endosperm of Tenera to that of Dura at 2.5 MAF. Samples collected from different tissues for Dura, Pisifera and Tenera (#53) were used for transcriptome analysis. Reads for enzymes with multiple isoforms were summed. For details on abbreviations, annotations, and transcriptome levels at each samples, see Dataset S1. 16:0, palmitic acid; 18:0, stearic acid; 18:1, oleic acid, 18:2, Linoleic acid; 18:3, linolenic acid. For details on abbreviations, annotations, and transcription levels at each stage, see Supplemental Dataset S1.

Lipid biosynthesis pathway genes exhibit hybrid vigor in endosperm but not significantly in mesocarp

To determine relative expression levels of genes in hybrids as compared to their parental inbred lines and to identify genes displaying expression levels that differ from additivity, eight gene expression classes were defined (Table 1) based on similar classifications published previously8,28,29. First, for any given gene, differential expression values in the hybrid relative to the parental inbred lines displaying the lower (low-parent, LP) and higher (high-parent, HP) expression levels, were estimated by fold change (Table 1). According to this classification scheme, 10,801 (endosperm) or 11,574 (mesocarp) genes were expressed in hybrid at least higher than one of the parental values (class 2, 5, 6, Table 1). Class 4 represents the largest class, containing 70% genes of the total that do not exhibit differential expression among the parents and hybrids. Furthermore, 1,107 (endosperm) and 230 (mesocarp) genes exhibited low-parent expression levels in the hybrid (class 7 and 8).

Table 1.

Gene number in each group.

| Class | Expression pattern | Endosperm | Mesocarp | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total gene num | Non-additive gene num | Total gene num | Non-additive gene num | ||

| 1 | LP < H < HP | 459 | 223 | 404 | 181 |

| 2 | LP < H = HP | 8,040 | 8,040 | 6,904 | 6,904 |

| 3 | LP = H < HP | 5,211 | 0 | 4512 | 0 |

| 4 | LP = H = HP | 41,500 | 6,015 | 42,358 | 13,082 |

| 5 | LP < HP < H | 2,478 | 2,478 | 3,794 | 3,794 |

| 6 | LP = HP < H | 283 | 283 | 876 | 876 |

| 7 | H < LP < HP | 464 | 0 | 116 | 0 |

| 8 | H < LP = HP | 643 | 0 | 114 | 0 |

| Total | 59,078 | 17,039 | 59,078 | 24,837 | |

LP: low parent, H: hybrid (Tenera), HP: high parent; <, > means at least two fold change (FC); = means the fold change is small than 2.

Within these classes, a subset of genes displayed nonadditive gene expression, i.e., expression levels in a hybrid that were significantly different from the average of the parental values (MPV: mid-parent value). A significant higher portion of genes in mesocarp showed nonadditive expression pattern, indicating a remarkable expression changes have taken place in mesocarp than seed organ endosperm (Table 1). We further analyzed whether lipid biosynthesis pathways are enriched in nonadditive expression gene by whole genome analysis. Though there is no enrichment on lipid biosynthesis in all non-additive genes showed in Table 1, but multiple lipid biosynthesis pathways are found to be highly enriched in endosperm (Supplementary Table S1), but not so significantly in mesocarp (Supplementary Table S2).

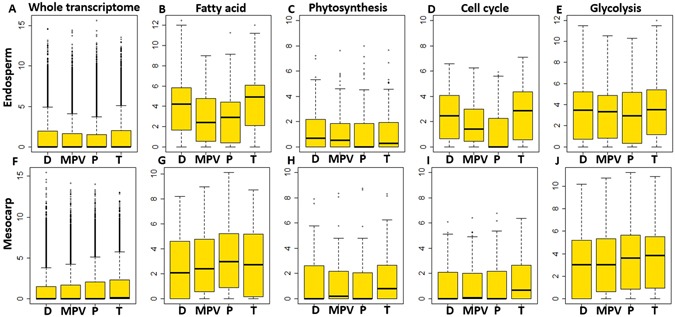

A detailed analysis between additive and nonadditive gene expression based on whole genome or individual pathway data generated similar conclusion for both endosperm and mesocarp (significant difference between Tenera and MPV by t-test analysis) (Fig. 3). Interestingly, cytokinine biosynthesis and cell cycle genes pathways are highly non-additive or displayed better than parents in both endosperm and mesocarp, explaining the confirmed rapid developing phenotype in hybrid by hyperactivity of cell proliferation phytohormone cytokinine (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 and Fig. 3). Furthermore, photosynthesis genes exhibited hybrid vigor in mesocarp, whereas endosperm exhibited an even lower than MPV level in a hybrid (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Heterosis, additive and non-additive gene expression. The midparent value (MPV) is equal to (Dura + Pisifera)/2, respectively. The gene expression based on the whole transcriptome and each pathways in Endosperm (A–E) or mesocarp (F–J) were boxploted. D, P, T in x-axis represents Dura, Pisifera and Tenera. Y-axis represents normalized expression level.

Expression pattern of genes involved in glycolysis and fatty acid biosynthesis

The expression of glycolysis genes is highly upregulated in mesocarp of Tenera against these of Dura. As shown in Fig. 2B, glycolysis, esp. the cytosolic pathway genes are highly expressed (Supplementary Figure S2). The carbon flow enhancing by presumed sucrose importing into developing fruits from photosynthetic organs (such as leaves), takes the highway in cytosol to biosynthesis more PEP and pyruvate, which are further served as substrates and transported into plastid for plastidial fatty acid synthesis. The genes encoding the cytosol-to-plastid transporters, which located in plastid membrane, POLYPRENYLTRANSFERASE 1 (PPT1) and BILE ACID: SODIUM SYMPORTER FAMILY PROTEIN 4 (BASS4) starting from the endosperm part, a relatively higher portion of genes are upregulated in fatty acid biosynthesis compared with the whole transcriptome level (1.8 VS 1.2). Only two subcategories Plastidial Fatty Acid Synthesis and extra Plastidial Phospholipid Synthesis are highly enriched (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Figure S4). On the contrary in mitochondria, the expression of genes encoded for enzymes in citric acid cycle, sharing the same substrate (pyruvate) with lipid biosynthesis, are at a similar level between Dura and Tenera on two tissues (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Figure S2).

Including the first enzyme complex of conversion pyruvate to fatty acids, PDH, 12 genes encoded for fatty acid synthesis (FAS) enzymes were, on average, 8-fold higher in endosperm of Tenera than that of Dura (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Figure S3). These expression data together with lipid content data indicated a closely coordinated expression during oil synthesis in seed tissue, and a pattern also noted in Arabidopsis thaliana and other seeds. The largest individual difference was noted for ketoacryl-acyl carrier protein (ACP), for which the expression was about 50-fold higher in Tenera relative to Dura. Contrary to highly expression of FAS related genes in endosperm, the level of FAS transcripts only mildly increased in Tenera than in Dura in mesocarp, except ketoacyl ACP synthase I (KASI), which encodes the key enzyme for fatty acid elongation, with an increase of 28-fold in Tenera (Fig. 2C). The mild increased expression of FAS genes is correlated with moderate lipid content shown in Fig. 1C. In contrast to a weak increase in FAS, the genes encoded for enzymes to determinate fatty acid profile/composition were, on average, 5-fold higher in mesocarp of Tenera than that of Dura, esp. for the ketoacyl ACP synthase II (KASII), which encodes the enzyme to convert C16 to C18, with an increase of 11-fold in Tenera. Since the expression changes were found in key genes for fatty acid composition determination, we deduced a higher C18:C16 ratio in Tenera. Gas chromatographic analysis showed that a much higher C18:C16 ratio in mesocarp of Tenera (1.60) than that of in Dura (1.28), consistent with the much higher KASII expression level found in mesocarp of Tenera (Fig. 2C). The desaturated to saturated fatty acid ratio was also increased in mesocarp of Tenera (1.23) than that of in Dura (1.0) (Supplementary Table S4). The higher C18:C16 level and higher desaturated fatty acid are the two key breeding targets for healthier palm oil by reducing “bad lipid” saturated palmitic acid (C16:0) level. The highly expression of FATTY ACID DESATURASE 3 (FAD3), encoding enzyme to synthesis α-linolenic acid C18:3 and longer fatty acid, are highly expressed in Tenera, fitting well with higher C18:3 and further derivate fatty acids in Tenera (3.6% Vs 0.7% in Dura) (Supplementary Table S4). In sharp contrast to the expression patterns for plastidial fatty acid enzymes, the TAG assembly in most enzymes showed similar level in both of endosperm and mesocarp of Tenera and Dura, except the two DAG:acyl-CoA acyltransferase (DGAT1 and DGAT2) that catalyse the last (acyl-CoA dependent) acylation step to TAG, with 8.6-fold and 2.3-fold of Dura in endosperm respectively (Fig. 2C).

PC-Related Enzymes Showed heterosis between Tenera and Dura

Beside of the plastidial fatty acid and glycolysis pathways, the Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane based polar phosphatidylchoilne (PC) synthesis pathway was also of highly ectopic expression in Tenera (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S5 and Supplementary Figure S4). Several studies have demonstrated the importance of PC metabolism and acyl editing in the process of TAG assembly, which proceed via either the methylation or nucleotide pathway. Bourgis et al. have shown that PC-Related enzymes show higher transcriptome level than the date palm major for sugar biosynthesis18, which suggest that PC-related enzymes might have some important functions on carbon partitioning. Consistently, by using our transcriptome data, we found out that most of the genes encoding PC-related enzymes were higher in Tenera, as compared to Dura, especially in mesocarp, such as choline kinase (CK), choline-phosphate cytidylyltransferase (CCT) and long-chain acyl-CoA synthesis (LACS) (Supplementary Figure S4). Furthermore, the mutation of phosphatidylcholine:diacylglycerolcholine phosphotransferase (PDCT) gene in Arabidopsis reduced polyunsaturated fatty acids linoleic acid 18:2 and 18:3 level accompanied with increased 18:1 level. We observed the enhanced expression of two PDCT genes (PDCT1 and PDCT2) in Tenera, which may explain the reverse trend of fatty acid composition change (higher poly- VS lower monosaturated fatty acid), compared with that of Dura in both mesocarp and endosperm (Supplementary Figure S2, Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). Hence, our data suggest that phospholipid and methylation pathway may play important roles in lipid heterosis between Tenera and Dura.

In summary, the expression pattern for most of the genes in lipid biosynthesis pathway is consistent with metabolite profiling analysis. Enhanced expression of genes in glycolysis and lipid biosynthesis pathways may be one of the fundamental reasons for the lipid heterosis of Tenera over its parental.

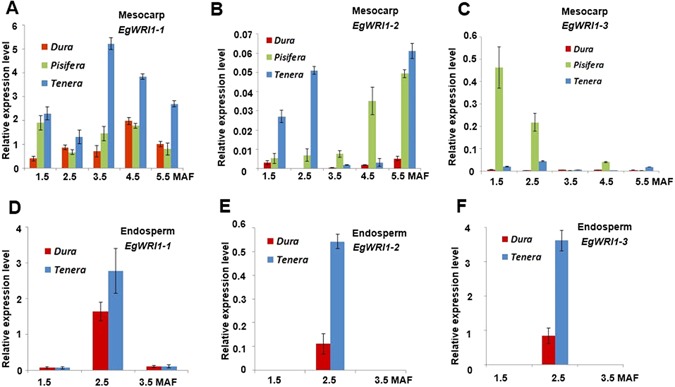

WRI1 transcription factors genes upregulated in Tenera than parental palms

Since there are many lipid biosynthesis genes upregulated in both tissues of Tenera compared with Dura, we suspected that some master regulators such as transcriptional factor may be involved in the transcriptional regulation of lipid heterosis. Three paralogs of the WRINKLED1 (WRI1) transcription factor were identified from our own and other published transcriptome data14,18. Here, we performed real-time quantitative RT-PCR to analyse the expression profile of three WRI1 genes in various tissues at different developing stages by designing gene specific primers shared by EgWRI1-1 and EgWRI1-2. As shown in Fig. 4, the expression of all there WRI1 coincided well with the oil biosynthesis in mesocarp and endosperm (Fig. 1). In general, all three WRI1 genes showed higher expression level in endosperm than in mesocarp. EgWRI1-1 gene expression is the highest, specifically at 3.5 MAF mesocarp and 2.5 MAF endosperm of Tenera. The expression level of EgWRI1-2 is only 1% of that of EgWRI1-1 in Tenera. EgWRI1-3 is highly expressed in early stages (1.5 to 2.5 MAF) of mesocarp of Pisifera, which suggested that the early rapid lipid biosynthesis accumulation may due to the early expression of EgWRI1-1 and EgWRI1-3 in mesocarp of Pisifera (Fig. 4). In almost all the stages we tested, three WRI1 genes are higher expression in Tenera than Dura, suggesting a strong transcription activity of this lipid biosynthesis master transcription factor may be one of the reasons to explain highly expressed lipid biosynthesis pathway genes, by which lipid heterosis took place in Tenera, both in mesocarp and endosperm tissues. The mechanisms why all three WRI1 genes are highly expressed in Tenera are still unknown. However, several groups have found that WRI1 can use AW motif to regulate other lipid related genes19,22,23. Among 338 identified genes in lipid synthesis by our transcriptome data, 207 (61%) has shown to contain WRI1 specific binding AW motif, same with previous findings22. This may also be one of the reasons to explain the important functions of WRI1 in oil yield of oil palm (Supplementary Dataset S1). In addition, we also tried to find some other upstream transcription factor genes, which might be correlation with WRI1’s expression, such as LEAFY COTYLEDON1 and PICKLE, but failed.

Figure 4.

Relative expression of three WRI1 genes (EgWRI1-1, -2, -3) in mesocarp (A–C) and endosperm (D–F). The data was presented as means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

WR1-1 and WRI-3 increase oil content and quality in transgenic plants

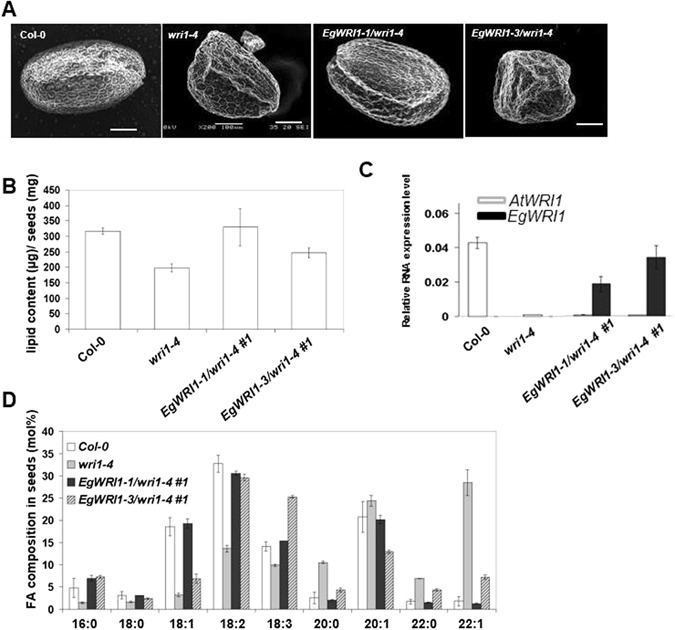

To further investigate the function of WRI1 paralogs in planta, complementary experiments were carried out in Arabidopsis. Due to the high sequence similarity between EgWRI1-1 and EgWRI1-2, and EgWRI1-2 was further exclude due to much lower expression level in various tissues and developing stages, we chose EgWRI1-1 and EgWRI1-3 to do transgenic work in Arabidopsis. Homozygous Arabidopsiswri1-4 mutants were transformed with EgWRI1-1 or EgWRI1-3 cDNA21, the expression of which was driven by the seed-specific oil palm Oleosin promoter. For each construct, 5 independent primary transformants were selected and propagated; the progeny of T3 lines were subjected to detailed analyses. A microscopic observation of mature dry seeds showed a complete reversion of the wrinkled seed phenotype usually observed in the wri1-4 mutant background (Fig. 5A). Fatty acid analyses confirmed the ability of only EgWRI1-1 but not EgWRI1-3 to restore the defect in not only fatty acid quantity but also fatty acid profile previously described in wri1-4 seeds (Fig. 5B,D) with an even lower transgene expression level than EgWRI1-3 (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Functional analysis of EgWRI1-1 and EgWRI1-3 in Arabidopsiswri1-4 mutant background. (A) Images of mature seeds of the wild type (ecotype Columbia-0 [Col-0]), mutant (wri1-4), complemented mutant with oil palm Oleosin promoter (EgOle:EgWRI1-1/wri1-4), and non-complemented mutant (EgOle:EgWRI1-3/wri1-4). Size bar: 100 µm. (B–D) Analysis of seed oil traits of Col-0, wri1-4, wri1-4 lines complemented with similar expression level of EgWRI1-1 or EgWRI1-3. Seed oil content (B) and fatty acid (FA) composition (D) were analyzed. (C) The expression level of both AtWRI1 and oil palm WRI1 (EgWRI1/EgWRI3) in complementary lines were measured by qRT-PCR. Error bars correspond to the SD calculated from three technical replicates per pool of 100 seeds.

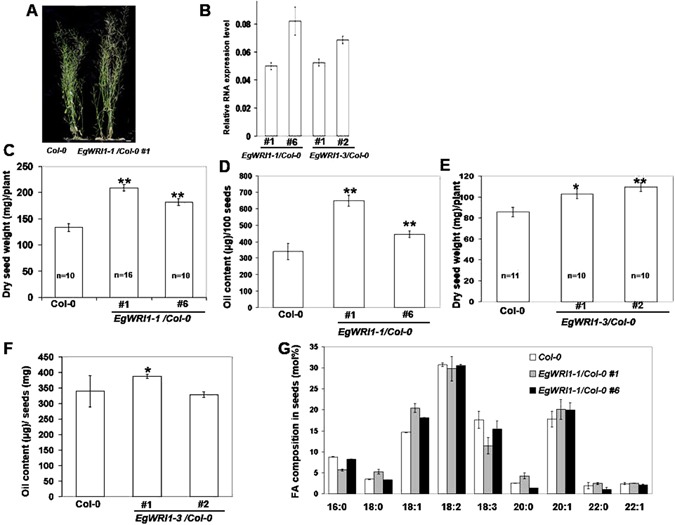

We further generated transgenic Arabidopsis plants at WT background which expressed either EgWRI1-1 or EgWRI1-3 to test whether ectopic expression of these genes can produce more lipid than WT plants. Figure 6 showed that the ectopic expression of EgWRI1-1 not only increase oil content but also produce more biomass and dry seed weight per plant, while EgWRI1-3 showed much weaker effect on oil yield increasing. The ectopic of EgWRI1-1 also changed seed oil profile, as a significantly higher level of oleic acid level were observed in EgWR11-1 overexpression lines. No effect of the expression of EgWRI1-3 on fatty acid composition has been found in EgWRI1-3 overexpression lines (Supplementary Figure S5).

Figure 6.

Functional analysis of EgWRI1-1 and EgWRI1-3 in WT Arabidopsis background. (A) Images of mature plants of the wild type (Col-0) and EgWRI1-1 expression line Size bar: 10 mm.(B) The expression level of EgWRI1-1 or EgWRI1-3 in seeds of overexpression Arabidopsis lines.(C and E) Dry seed weight of each plant for Col-0, two EgWRI1-1 expression lines (C) and two EgWRI1-3 expression lines (E). Plants number used was indicated. (D and F) Seed oil content for Col-0, two EgWRI1-1 expression lines (D) and two EgWRI1-3 expression lines (F). (G) Fatty Acid (FA) composition was analyzed for Col-0 and two EgWRI1-1 expression lines.

Discussion

Oil palm is the most productive oil-bearing crop. Over-represented genes in lipids metabolism and glycolysis are expressed differentially in mesocarp and endosperm of Tenera, accounting for the lipid heterosis and the different properties of palm mesocarp and endosperm oils. Due to non-additive variation, the heterosis observed in this research can be various in different combinations of parents.

Although heterosis has been widely exploited in plant breeding and plays an important role in agriculture30–33, the molecular and genetic mechanisms underlying the phenomenon remain poorly understood. Differential gene expression between a hybrid and its parents may be associated with heterosis. Hence, in this study, we used RNA-seq to compare the temporal and spatial change of lipids compositions and transcriptomes during the development of oil palm fruits for oil palm hybrid Tenera and its parents Dura and Pisifera. In comparison between Tenera and Dura, a much higher ratio (13.5:1) of up-regulated to down-regulated expression gene was observed in this transcriptome data, implying that the increased efficiency of a subset of transcripts were responsible for the heterosis between Tenera and its parental lines.

Comparison of significant differential gene with QTLs for oil yield of oil palm

QTL provide links between genotype and phenotype for complex traits, and QTL analysis had been widely used to study heterosis in other crops7,34. These significant differential genes between Tenera and its parents are derived from the heterozygosis of the combined hybrid genomes and may be potentially associated with phenotypic changes in the hybrid. Although QTL analysis is still very limited because of the narrow number of markers35,36, We are still able to identify single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) based on our sequencing data. After mapping SNPs to gene locus, a lot of allele specific genes were identified (Supplementary Figure S6A). If we focus on the fatty acid related groups, the portion is larger (Supplementary Figure S6B), implying that lipid heterosis in Tenera may be largely due to dominance, especially on the difference in allele frequency between the parental lines.

Marker-assisted breeding is a powerful tool for shortening the breeding generation time. Several papers have described the important traits with molecular markers development and application in oil palm breeding program27,37. These identified genes shown non-addictive effect in this report could be further used to develop molecular markers for oil traits mapping and elite tree characterization.

Some other genes also exhibit hybrid vigor in Tenera

WRI1 genes are not supposed to control TAG assembly steps. However, DGAT1 and DGAT2 are highly expressed in endosperm of Tenera, correlated with higher expression of WRI1 genes in out studies. By generating transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plants to express EgDGAT1 and EgDGAT2, DGAT1 ectopic expression in Arabidopsis thaliana can produce higher oil content than WT control (Supplementary Figure S7). Three acyl-acyl carrier protein thioesterase paralogs (EgFATB1, EgFATB2 and EgFATB3) have been reported to increase not only oil yield but also oil profile. We generated transgenic plants to express EgFATB1 or EgFATB2. Instead of increase oil yield, we observed a reduction of plant biomass by expression of EgFATB1 (Supplementary Figure S8). All saturated fatty acid composition (C16:0, C18:0, C20:0 and C22:0) are increased in EgFATB1 and EgFATB2, indicating both of them are important for saturated fatty acid biosynthesis and are good candidates to be manipulated to improve oil trait in the future.

Networking but not dominance genes contributes to heterosis

Over-representation of additive expression in heterosis, the additive distribution of transcriptome in elite hybrids, and the low level or additively of intermediates suggest that there is an additively balance network regulating the heterosis between hybird and its parental lines. Fu et al. found that the germination-related hormone signal transduction, the abscisic acid and gibberellin regulation networks may contribute seed heterosis in maize38. Zhang et al. observed that coexistence of multiple gene actions cause oil rape improvement in Brassica39. Similarly, in our study, we also identified one important transcription factor WRI1 and lipid related genes showing additive mode in hybrid Tenera, which implies heterosis regulation every node of the gene regulation network in a hybrid.

Tissue-specific pattern variation in heterosis

By comparing the allelic expression ratios in mesocarp and endosperm of F1 hybrid plants, we were able to test for expression variation among different tissues. Lipid biosynthesis pathway genes exhibited hybrid vigor in endosperm but not in mesocarp. However, glycolysis did not show the similar pattern. The most likely explanation for the different additively and nonadditively pattern among different tissues is that there are tissue-specific effects on their relative expression levels during crossing and evolution. This finding is similar to studies of the homoeologous genes in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) polyploids, in which genes derived from the A and D subgenomes show different relative expression levels among different tissue types40. Some people indicated that it may be due to the allele variations that caused these different regulatory expression patterns28.

In summary, heterosis as a complex phenomenon, involves numerous component phenotypes, including quantitative and qualitative variations. Our data provides a key explanation to dissect the genetic basis of heterosis for oil yield in hybrid Tenera, comparing with its parental Pisifera and Dura. By combining lipid and transcriptome profiling, an additive expression pattern, including overdominant, dominant and nondominant effect may be the major manifestation of heterosis for oil yield in Tenera. Further work should address these selection networks for hybrid in a system level.

Methods

Oil palm plant material and field data collection

Mother palm population Dura (Deli), father palm population Pisifera (TS3, AVROS) and the crossing population Tenera oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) trees used in this research were planted in plantation of Wilmar International, South Sumatra (Palembang, Indonesia). The management and field yield data of the three populations was carried out following the standard protocol of Wilmar International. Dura fruits were harvested from trees from a Dura parent of Deli origin (Dura A), within the same self-progeny of a single tree. Pisifera fruits were harvested from trees from a Tenera X Pisifera parent of TS3 (African AVROS origin) within the same self-progeny of a selfed population. For each stage of development for Dura and Pisifera, at three independent bunches were tagged and harvested on three distinct individuals of the same genotype. For Tenera samples, two bunches of each developmental stage fruits of the tree #53 were tagged. Ten spikelets were then collected from each bunch and all undamaged fruits withdrawn from each of the ten spikelets were randomly sampled. Mesocarp and endosperm of each fruit were separated and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Bioinformatics and transcriptome data analyses

Twenty-four RNA libraries were prepared and sequenced by Illumina HiSeq2000, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Around 20 million RNAseq reads of 101 bp length were generated from mesocarp and kernel samples respectively. The quality of the generated sequence was checked by FASTQC [http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/]. Trinity41 was used for de novo assembly of the raw reads to generate unigenes. Totally 59,078 unigenes was got with around 96,062 isoforms [Supplementary Data Set S1. The Arabidopsis thaliana protein annotation database (TAIR 10) was used to the function annotation, with at least one hit in BLASTX search with E-value < = 1e−3. RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization)42 was used for abundance estimation for assembled transcripts to measure the expression level.. Information on data files containing function annotation and temporal expression is provided in Supplementary Data Set S1. ANOVA-test was used to statistical analysis for the additive and non-additive expression between different groups.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and light microscopy

Dry Arabidopsis seeds were collected and visualized under a scanning electron microscope (JSM-6360LV, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). For Light microscopy, mesocarp and endosperm discs were excised from fresh oil palm fruit and fixed overnight in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 as described before43. The sample discs were rinsed three times in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 15 min each, and were then post-fixed in 1% (w/v) aqueous OsO4 for 1 hr. Tissues were dehydrated in an ethanol series and embedded in Spurr’s resin. Semi-thin sections with thickness of 500 nm were stained in 0.1% toluidine blue and photographed with a Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Transgenic plasmids construction, transgenic Arabidopsis lines generation and growth conditions

The pBA-002 and pCAMBIA1300-derived vectors were used for all vector construction in this report44. The complete open reading frame of EgFATB1, EgFATB2, EgDGAT1, EgDGAT2, EgWRI1-1, and EgWRI1-3 was amplified by PCR using the primer pairs list in Supplementary Table S4. We used Arabidopsis thaliana wild type (Col-0) and homozygous Arabidopsis wri1-4 mutants (Col-0 background) as start plant materials. Sterilized seeds were incubated on Murashige and Skoog medium at 4 °C for 3 d and transferred to long-day conditions for growth (16 h of L/8 h of D). Transgenes were introduced into plants by Agrobacterium tumefaciens–mediated infiltration using the Arabidopsis floral dip method45. For seed mass analysis, seed mass of each plant was determined by weighing mature dry seeds collected from one whole plant.

Lipid content analysis

To analyse the lipid content in oil palm, individual tissue and each stage of development, lipid analyses were performed in triplicate (from three different extractions) using a completely random experimental design. Each extraction is from materials of at least 3 fruits samples. The dry mesocarp and endosperm part were grinded to fine powder and the lipids were extracted with hexane three times. The weight of the total lipid was determined and the total lipid content was recorded as the ratio of total lipid to dried endosperm or mesocarp weight (lipid content, %). Total lipid content in one year for one tree was calculated as (lipid content, %) * average year endosperm or mesocarp yield per tree (Kg, based on the yield data of trees of 4th and 5th years after germination). The data were presented as means ± standard deviations.

For Arabidopsis seeds fatty acid analysis, total lipid was extracted and transmethylated from 100 dry Arabidopsis seeds as Li et al. described46. FAMEs were generated as described before47 and separated by GC and detected using GC Agilent 7890 coupled with 5975 C MS (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The data were presented as means ± standard deviations.

RNA extraction, quantitative RT-PCR and RNAseq analysis

Total RNA was extracted from all kinds of samples by grinding to fine powder in liquid nitorigen and extracted with RNeasy plant mini kits (Qiagen) or plant RNA purification reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), following with DNAse treatment48. Quantitative RT-PCR for the genes in this study (Supplementary Table S6) was performed as method described before49. Ubiquitin was used as an internal control to normalize gene expression levels. Primers were listed in Supplementary Table S6.

TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kits v2 was used to generating mRNA-focused libraries from total RNA according to the protocol instruction.

Accession numbers

The RNA-seq data supporting this study are available in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ: http://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/) under accession number DRA001857

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Gang Wang, Xiyuan Jiang, KharMeng Ng for their invaluable assistance with experiments. We thank YuLin Jiang for the revise of our manuscript. This research was funded by Wilmar International. JY and YWS were supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Strategic Priority Research Program Grant NO. XDB11040300 and Natural Science Foundation of China NSFC31522046, 31672001). JJ was partially supported by a Singapore Ministry of Education Tier-2 grant (MOE2009-T2-2-004), Encode of Tobacco genome (902016AA0390) and Parallel variation calling tools (902015CA0250).

Author Contributions

Y.J., J.J.J., G.H.Y. and N.H.C. designed the study. Y.J. supervised the experiments of oil palm fruits sampling and RNA extraction. R., Y.A., C.H.L., A.S., N.R. and Y.J. collected plant samples, and did RNA preparation of oil palm tissues and related lab work. J.Y., Y.W.S. and J.Q. designed and conducted the experiments on RNA-seq, qRT-PCR, transgenic Arabidopsis plant generation and oil related traits measurement. J.J. and L.S.W. performed bioinformatics analysis of the sequencing data. Y.J., J.J., Y.G.H. and N.H.C. wrote the manuscript and all authors read and approved the final version.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jingjing Jin and Yanwei Sun contributed equally.

Change history

10/25/2018

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has been fixed in the paper.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-00438-8

References

- 1.Goff SA, Zhang Q. Heterosis in elite hybrid rice: speculation on the genetic and biochemical mechanisms. Current opinion in plant biology. 2013;16:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schnable PS, Springer NM. Progress toward understanding heterosis in crop plants. Annual review of plant biology. 2013;64:71–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li D, et al. Gene expression analysis and SNP/InDel discovery to investigate yield heterosis of two rubber tree F1 hybrids. Scientific reports. 2016;6:24984. doi: 10.1038/srep24984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu X, Li R, Li Q, Bao H, Wu C. Comparative transcriptome analysis among parental inbred and crosses reveals the role of dominance gene expression in heterosis in Drosophila melanogaster. Scientific reports. 2016;6:21124. doi: 10.1038/srep21124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longin CF, et al. Hybrid breeding in autogamous cereals. TAG. Theoretical and applied genetics. Theoretische und angewandte Genetik. 2012;125:1087–1096. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1967-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen ZJ. Genomic and epigenetic insights into the molecular bases of heterosis. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2013;14:471–482. doi: 10.1038/nrg3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lippman ZB, Zamir D. Heterosis: revisiting the magic. Trends in genetics: TIG. 2007;23:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paschold A, et al. Complementation contributes to transcriptome complexity in maize (Zea mays L.) hybrids relative to their inbred parents. Genome research. 2012;22:2445–2454. doi: 10.1101/gr.138461.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krieger U, Lippman ZB, Zamir D. The flowering gene SINGLE FLOWER TRUSS drives heterosis for yield in tomato. Nature genetics. 2010;42:459–463. doi: 10.1038/ng.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi J, Li R, Zou J, Long Y, Meng J. A dynamic and complex network regulates the heterosis of yield-correlated traits in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) PloS One. 2011;6:e21645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radoev M, Becker HC, Ecke W. Genetic analysis of heterosis for yield and yield components in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) by quantitative trait locus mapping. Genetics. 2008;179:1547–1558. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.089680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X, et al. Gene expression profiles associated with intersubgenomic heterosis in Brassica napus. TAG. Theoretical and applied genetics. Theoretische und angewandte Genetik. 2008;117:1031–1040. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0842-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bi Y, et al. Heterosis and combining ability estimates in isoflavone content using different parental soybean accessions: wild soybean, a valuable germplasm for soybean breeding. PloS one. 2015;10:e0114827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dussert S, et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis of three oil palm fruit and seed tissues that differ in oil content and fatty acid composition. Plant physiology. 2013;162:1337–1358. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.220525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh R, et al. Oil palm genome sequence reveals divergence of interfertile species in Old and New worlds. Nature. 2013;500:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin J, et al. Draft genome sequence of an elite Dura palm and whole-genome patterns of DNA variation in oil palm. DNA research: an international journal for rapid publication of reports on genes and genomes. 2016;23:527–533. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsw036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shearman JR, et al. Transcriptome analysis of normal and mantled developing oil palm flower and fruit. Genomics. 2013;101:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bourgis F, et al. Comparative transcriptome and metabolite analysis of oil palm and date palm mesocarp that differ dramatically in carbon partitioning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:12527–12532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106502108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tranbarger TJ, et al. Regulatory mechanisms underlying oil palm fruit mesocarp maturation, ripening, and functional specialization in lipid and carotenoid metabolism. Plant physiology. 2011;156:564–584. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.175141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh R, et al. The oil palm SHELL gene controls oil yield and encodes a homologue of SEEDSTICK. Nature. 2013;500:340–344. doi: 10.1038/nature12356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baud S, Wuilleme S, To A, Rochat C, Lepiniec L. Role of WRINKLED1 in the transcriptional regulation of glycolytic and fatty acid biosynthetic genes in Arabidopsis. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology. 2009;60:933–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maeo K, et al. An AP2-type transcription factor, WRINKLED1, of Arabidopsis thaliana binds to the AW-box sequence conserved among proximal upstream regions of genes involved in fatty acid synthesis. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology. 2009;60:476–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma W, et al. Wrinkled1, a ubiquitous regulator in oil accumulating tissues from Arabidopsis embryos to oil palm mesocarp. PloS One. 2013;8:e68887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu XL, Liu ZH, Hu ZH, Huang RZ. BnWRI1 coordinates fatty acid biosynthesis and photosynthesis pathways during oil accumulation in rapeseed. Journal of integrative plant biology. 2014;56:582–593. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grimberg A, Carlsson AS, Marttila S, Bhalerao R, Hofvander P. Transcriptional transitions in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves upon induction of oil synthesis by WRINKLED1 homologs from diverse species and tissues. BMC plant biology. 2015;15:192. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0579-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Y, et al. Ectopic Expression of WRINKLED1 Affects Fatty Acid Homeostasis in Brachypodium distachyon Vegetative Tissues. Plant physiology. 2015;169:1836–1847. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee M, et al. A consensus linkage map of oil palm and a major QTL for stem height. Scientific reports. 2015;5:8232. doi: 10.1038/srep08232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Springer NM, Stupar RM. Allele-specific expression patterns reveal biases and embryo-specific parent-of-origin effects in hybrid maize. The Plant cell. 2007;19:2391–2402. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoecker N, et al. Comparison of maize (Zea mays L.) F1-hybrid and parental inbred line primary root transcriptomes suggests organ-specific patterns of nonadditive gene expression and conserved expression trends. Genetics. 2008;179:1275–1283. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.088278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ge X, et al. Transcriptomic profiling of mature embryo from an elite super-hybrid rice LYP9 and its parental lines. BMC plant biology. 2008;8:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song GS, et al. Comparative transcriptional profiling and preliminary study on heterosis mechanism of super-hybrid rice. Molecular plant. 2010;3:1012–1025. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei G, et al. A transcriptomic analysis of superhybrid rice LYP9 and its parents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:7695–7701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902340106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhai R, et al. Transcriptome analysis of rice root heterosis by RNA-Seq. BMC genomics. 2013;14:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia AA, Wang S, Melchinger AE, Zeng ZB. Quantitative trait loci mapping and the genetic basis of heterosis in maize and rice. Genetics. 2008;180:1707–1724. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.082867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh R, et al. Mapping quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for fatty acid composition in an interspecific cross of oil palm. BMC plant biology. 2009;9:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ting NC, et al. SSR mining in oil palm EST database: application in oil palm germplasm diversity studies. Journal of genetics. 2010;89:135–145. doi: 10.1007/s12041-010-0053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cros D, Denis M, Bouvet JM, Sanchez L. Long-term genomic selection for heterosis without dominance in multiplicative traits: case study of bunch production in oil palm. BMC genomics. 2015;16:651. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1866-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fu Z, et al. Proteomic analysis of heterosis during maize seed germination. Proteomics. 2011;11:1462–1472. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, et al. Transcriptome Analysis of Interspecific Hybrid between Brassica napus and B. rapa Reveals Heterosis for Oil Rape Improvement. International Journal of Genomics. 2015;2015:11. doi: 10.1155/2015/230985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams KL. Evolution of duplicate gene expression in polyploid and hybrid plants. The Journal of heredity. 2007;98:136–141. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esl061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grabherr MG, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Bo, Dewey Colin N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(1):323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ye J, Qu J, Bui HT, Chua NH. Rapid analysis of Jatropha curcas gene functions by virus-induced gene silencing. Plant biotechnology journal. 2009;7:964–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ye J, et al. Geminivirus Activates ASYMMETRIC LEAVES 2 to Accelerate Cytoplasmic DCP2-Mediated mRNA Turnover and Weakens RNA Silencing in Arabidopsis. PLoS pathogens. 2015;11:e1005196. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li R, et al. Virulence factors of geminivirus interact with MYC2 to subvert plant resistance and promote vector performance. The Plant cell. 2014;26:4991–5008. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.133181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y, Beisson F, Pollard M, Ohlrogge J. Oil content of Arabidopsis seeds: the influence of seed anatomy, light and plant-to-plant variation. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:904–915. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qu J, et al. Development of marker-free transgenic Jatropha plants with increased levels of seed oleic acid. Biotechnology for biofuels. 2012;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qu J, Ye J, Fang R. Artificial microRNA-mediated virus resistance in plants. Journal of virology. 2007;81:6690–6699. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02457-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qu J, et al. Dissecting functions of KATANIN and WRINKLED1 in cotton fiber development by virus-induced gene silencing. Plant physiology. 2012;160:738–748. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.198564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.