Abstract

Osteoporosis is a global public health problem affecting more than 200 million people worldwide. We previously showed that treatment with α-1 antitrypsin (AAT), a multifunctional protein with antiinflammatory properties, mitigated bone loss in an ovariectomized mouse model. However, the underlying mechanisms of the protective effect of AAT on bone tissue are largely unknown. In this study, we investigated the effect of AAT on osteoclast formation and function in vitro. Our results showed that AAT dose-dependently inhibited the formation of receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL)-induced osteoclasts derived from mouse bone marrow macrophage/monocyte (BMM) lineage cells and the RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cell line. To elucidate the possible mechanisms underlying this inhibition, we tested the effect of AAT on the gene expression of cell surface molecules, transcription factors and cytokines associated with osteoclast formation. We showed that AAT inhibited macrophage colony–stimulating factor (M-CSF)–induced cell surface RANK expression in osteoclast precursor cells. In addition, AAT inhibited RANKL-induced TNF-α production, cell surface CD9 expression and dendritic cell–specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP) gene expression. Importantly, AAT treatment significantly inhibited osteoclast-associated mineral resorption. Together, these results uncover new mechanisms for the protective effects of AAT and strongly support the notion that AAT has therapeutic potential for the treatment of osteoporosis.

INTRODUCTION

Bone homeostasis is maintained by the mutual function of bone-resorbing hematopoietic lineage–derived osteoclasts (OCs) and mesenchymal stem cell–derived bone-forming osteoblasts (1). The balance between osteoclasts and osteoblasts is important for normal skeletal formation and function. Therefore, recruitment, proliferation and differentiation of these two types of cells are critical to maintain the normal physiology of bone (2). Osteoclast formation is a normal aspect of skeletal morphogenesis and remodeling; however, disproportionate osteoclast proliferation and activation can lead to excessive bone resorption. This can subsequently lead to chronic systemic bone diseases such as osteoporosis, which is a serious public health problem affecting an estimated 34 million Americans and causing 2 million fractures annually (3,4). Strategies to inhibit excessive osteoclast formation and/or function have proven to have therapeutic usefulness for the treatment of osteoporosis (1). However, the use of currently available drugs is limited due to their side effects, including osteonecrosis of the jaw, which can be caused by nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates, the most commonly used antiresorptive drugs, and denosumab, a monoclonal antibody inhibitor of RANKL (1,5).

OCs are large multinucleated cells. Differentiation of OCs is regulated by receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-B ligand (RANKL) and macrophage colony–stimulating factor (M-CSF) from osteoblasts and stromal cells in the bone marrow environment (6–8). RANKL plays a critical role in the development, survival and activity of OCs. M-CSF contributes to proliferation, survival, and differentiation of early precursors. Arai et al. (9) identified the early and late stages of osteoclast precursor (OCP) cells and demonstrated that in both the early and late stage of OCP cells, M-CSF stimulates the expression of RANK. RANK on the surface of OCP interacts with RANKL and recruits TNF receptor–associated factor (TRAF) family proteins such as TRAF6, which is an adapter molecule. These TRAF family proteins, especially TRAF6, activate NF-κB and MAP kinases (MAPKs). Activation of NF-κB and MAPKs eventually activates c-Fos, PU.1 and NFATc1, all of which are essential for osteoclast differentiation (10,11). Among these factors, NFATc1 is considered a master switch for regulating terminal differentiation of OCs (12). During OC differentiation, OCP cells fuse with one another to form multinuclear mature osteoclasts. This fusion requires expression of cell fusion–promoting proteins by OCP cells. Several cell fusion–promoting proteins have been identified, including dendritic cell–specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP), CD9 and Atp6v0d2, and they are also stimulated by RANKL-RANK signaling pathways (13,14). RANKL also plays an important role in OC activation (15). RANK-RANKL binding on mature OCs triggers internal structural changes and results in secretion of protons and lytic enzymes into a sealed extracellular resorption compartment. Cathepsin K (CatK) is an enzyme responsible for degradation of bone collagen matrices. Acidification of the resorption compartment is important for the activation of CatK. Secretion of protons by the vacuolar H+-ATPase leads to activation of CatK (16,17). Therefore, RANK-RANKL signaling is essential for osteoclast formation and activation (18), and the discovery of the RANK signaling pathway has provided insight into the mechanisms of osteoclastogenesis and activation of bone resorption (17). Inhibition of RANK expression in OCP cells could be one logical approach to inhibit excessive osteoclast formation and activation.

During inflammation, several proinflammatory cytokines are produced. These messenger molecules not only perpetuate inflammation but also, in turn, stimulate osteoclast formation and thus bone resorption, leading to osteoporosis and increased fracture rate (19,20). In these scenarios, different proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6, have been shown to be capable of stimulating increased levels of RANKL/CSF-1–induced osteoclastogenesis (19). Studies have shown that TNF-α induced by RANKL promotes osteoclastogenesis in vitro by modulating RANK signaling pathways.

Human α-1 antitrypsin (AAT) is a protease inhibitor with cytoprotective and antiinflammatory properties. It inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced secretion of TNF-α and IL-1β, and enhances the production of antiinflammatory IL-10 from human monocytes (21). In inflammation-related disease models, including type 1 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis, AAT showed therapeutic potential (22–26). In addition, AAT inhibited the activity of NF-κB, which is important for the gene expression of proinflammatory cytokines (27). Recently, we showed that AAT protein and gene therapies reduced bone loss in an ovariectomized mouse model (28). We also showed that mesenchymal stem cells expressing AAT ameliorate bone loss in osteoporotic mice (29). The goal of this study was to test the effect of AAT on RANKL-induced osteoclast formation and function, and to elucidate the possible underlying mechanism of these effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Cells

Six-week-old C57BL/6 mice and TNF-α receptor (TNFR1 and TNFR2) deficient C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and housed in specific pathogen-free conditions under a 12 h light/dark cycle at the University of Florida animal care facility. All procedures were performed according to University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Murine leukemic monocyte macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA).

Reagents and Antibodies

Minimum essential medium, α modification (MEM-α) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and penicillin/streptomycin were purchased from Corning (Manassas, VA, USA). Recombinant murine RANKL and M-CSF were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). For tartrate resistance acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining, a leukocyte acid phosphatase kit was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. AAT (Prolastin C, Telecris Biotherapeutics, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) was used. Anti-mouse CD265 (RANK) phycoerythrin (PE) conjugated antibody, anti-mouse CD9 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated antibody and 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) viability staining solution were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti–DC-STAMP antibody clone 1A2 was purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-10 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were purchased from Peprotech.

Osteoclast Formation

Murine osteoclasts were generated from BMM lineage cells as described previously (30). Briefly, femurs and tibiae were removed aseptically from 6-to 7-wk-old C57BL/6 male mice and dissected free of adhering tissues. The bone ends were cut off with scissors and the marrow cavities were flushed with 3 mL of MEM-α through one end of the bone using a sterile 27-gauge needle. The bone marrows were filtered with 70 μm nylon mesh filter (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), centrifuged to collect the pellet and treated with 1–2 mL of NH4Cl solution (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) to lysis of red blood cells. The bone marrow cells were then washed once with MEM-α, suspended in MEM-α supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and cultured in 20 × 106 cells/100 mm diameter cell culture dish with M-CSF (100 ng/mL) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 16 h. During that time, BMMs and their precursors can survive as nonadherent cells (31), which are called early-stage OCP cells. Nonadherent cells were harvested and cultured for another 3 d in medium containing M-CSF (100 ng/mL). Then, floating cells were removed by pipetting, and attached cells, which we considered late-stage OCP cells, were collected by scraping. To generate osteoclasts, late-stage OCP cells were cultured with RANKL (100 ng/mL) and M-CSF (50 ng/mL) for an additional 3 d in 96-well cell culture plate (2 × 104 cells/0.25 mL/well) or 24-well plate (1 × 105 cells/0.5 mL/well). Since generating osteoclasts from BMM cells requires 7 d, we added different concentrations of AAT (0.5, 1 and 2 mg/mL) at different time points to investigate its effect on osteoclast formation and function. We named our studies Experiments 1–3. In Exp-1, AAT was added from d 0–7; in Exp-2, AAT was added from d 4–7; and in Exp-3, AAT was added from d 0–4. A procedure similar to that mentioned above was used to generate osteoclasts from TNF-α receptor (TNFR1 and TNFR2) deficient C57BL/6 mice, and in this case, AAT was added according to Exp-2 (d 4–7). To generate osteoclasts from the RAW 264.7 cell line, cells were cultured in MEM-α medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin with RANKL (100 ng/mL) in 96-well cell culture plate (8 × 103 cells/0.25 mL/well) or 24-well plate (30 × 103 cells/0.5 mL/well) with or without AAT in different concentrations (0.5, 1 and 2 mg/mL) for 6 d. Old media was replaced with fresh media containing RANKL (100 ng/mL) on d 3 (31).

TRAP Staining

Osteoclasts were generated as described above. To determine the TRAP+ osteoclasts, cells were washed with PBS, fixed with cold 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100. TRAP+ cells were detected using a leukocyte acid phosphatase kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. The positive cells for TRAP staining contain red granular material in cells. TRAP+ multinuclear cells containing ≥3 nuclei were considered multinuclear osteoclast cells (MNCs). The cells were examined under a microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted fluorescence microscope using Axicam MRc5) and counted.

Resorption Pit Assay

For resorption pit assays, we performed two different experiments. First, we generated the osteoclasts using M-CSF and RANKL on a 96-well osteo assay surface plate (Corning, NY, USA) as described above and treated them with different concentrations of AAT (0.5, 1 and 2 mg/mL) from d 0–7. Cells were removed using 10% bleach and resorption pits were photographed with a microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted fluorescence microscope using Axicam MRc5) and analyzed with Image J version 1.50b software. In another experiment, we first generated osteoclast cells on 96-well tissue culture plate using M-CSF and RANKL as described above. At d 6 of osteoclast induction, the cells were then plated on the 96-well osteo assay surface plate and allowed to settle for 2 h, then incubated with different concentrations of AAT (0.5, 1 and 2 mg/mL) for an additional 3 d. Cells were removed using 10% bleach and resorption pits were photographed and analyzed with Image J software.

Detection of Cytokines

Osteoclast cells were generated as described above. During osteoclast generation, the culture medium was collected and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min at 25°C to remove any dead cells. The concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-10 were determined using murine ELISA development kits following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Flow cytometry analysis was carried out with FACSCalibur CellQuest Pro version 5.2.1 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and data were analyzed using FCS Express version 4 software (Denovo) at the University of Florida Flow Cytometry Core. Antibodies used in this study were PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD265 (RANK) antibody, FITC conjugated anti-mouse CD9 antibody and anti-mouse DC-STAMP antibody. For staining of intracellular DC-STAMP, cells were permeabilized and stained using the cytofix/cytoperm kit (BD Bioscience). Dead cells stained with 7-AAD viability staining solution were excluded from the analysis. A gate was set of living cells and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was compared with unstained cells.

Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction

To quantify gene expression levels, total RNA was extracted from cultured cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Complementary DNA was synthesized from total RNA using reverse transcriptase (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and subjected to real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Results were normalized to the gene expression levels of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in the same sample. The fold-change ratios between test and control samples were calculated. The following primers were used: for NFATc1, 5′-CCG TCC AAG TCA GTT TCT ATG T-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTC CGT GGG TTC TGT CTT TAT-3′ (reverse); for cFos, 5′-GAA TCC GAA GGG AAC GGA ATA A-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCT CCG CTT GGA GTG TAT CT-3′ (reverse); for GAPDH, 5′-TGC ACC ACC AAC TGC TTA G-3′ (forward), and 5′-GGA TGC AGG GAT GAT GTT C-3′ (reverse); for NFκB, 5′-TACAAGCTGGCTGGTGGGGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTCGCGGGTCTCA GGACCTT-3′ (reverse); for RANK, 5′-CAC AGA CAA ATG CAA ACC TT G-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTG TTC TGG AAC CAT CTT CCT CC-3′ (reverse); for DC-STAMP, 5′-TCCTCCATGAACAA ACAGTTCCAA-3′ (forward) and 5′ AGACGTGGTTTAGGAATGCAG CTC-3′ (reverse); and for cathepsin K, 5′TCAGAAGATGACGGGACTCA-3′ (Forward) and 5′-TCTTGAGTTGGCC CTCCA-3′ (reverse).

Determination of Cathepsin K Activity

Cathepsin K activity was determined by using a cathepsin K drug discovery kit (BML-AK430; Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with GraphPad Prism5 software, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Student t test was used to compare two samples. The data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and values of P <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

All supplementary materials are available online at www.molmed.org.

RESULTS

AT Inhibited RANKL-Induced Osteoclast Formation in a Dose-Dependent Manner

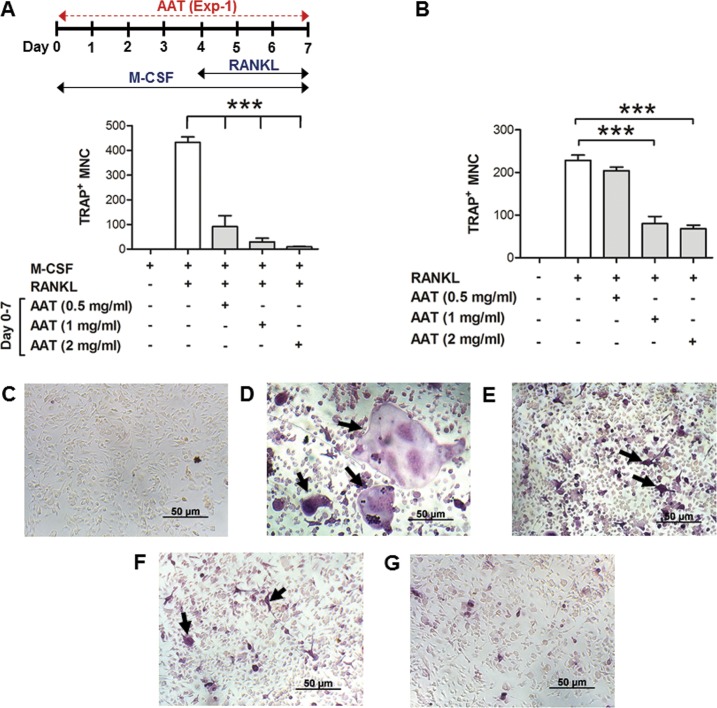

In this study, we isolated BMM cells from C57BL/6 mice and generated late-stage OCP cells with M-CSF for 4 d (from d 0–4). The late-stage OCP cells were further stimulated with RANKL and M-CSF for an additional 3 d (from d 4–7). We added different concentrations of AAT from d 0–7 (Exp-1 in Figure 1A). The cells were stained for TRAP activity and the total number of TRAP+ MNCs was counted. AAT significantly reduced the number of TRAP+ MNCs in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 1A, C–G). These results indicate that AAT inhibited the formation of RANKL-induced mature multinuclear OCs. We performed similar experiments using RAW 264.7 cells. To induce OCs, we cultured RAW 264.7 cells with RANKL for 6 d (31). We added different concentrations of AAT from d 0–6. Results from this study also show that AAT dose-dependently inhibited TRAP+ multinuclear OC formation (Figure 1B). Together, the results from these two cell systems demonstrate that AAT inhibited RANKL-induced OC formation.

Figure 1.

AAT inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclast formation. (A) TRAP+ multinuclear cells. MNCs (cell number/well of 96-well cell culture plate) derived from BMM cells. Top diagram, experimental design. Different concentrations of AAT were added during RANKL-induced osteoclast formation (Exp-1, d 0–7). (B) TRAP+ MNCs (cell number/well of 96-well cell culture plate) derived from RAW 264.7 cells. Here, osteoclasts were generated with RANKL for 6 d with or without different concentrations of AAT as indicated. (C–G) Representative images of TRAP+ MNCs shown in (A): (C) M-CSF only (considered as negative control); (D) RANKL + M-CSF (considered as positive control); (E) RANKL + M-CSF + AAT (0.5 mg/mL); (F) RANKL + M-CSF + AAT (1 mg/mL); (G) RANKL + M-CSF + AAT (2 mg/mL). Values are means ± SEM of at least triplicate samples. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ***P <0.0001. Scale bar, 50 μm. The arrow indicates multinuclear osteoclast cells.

Effect of AAT on Early-and Late-stage OCP Cells

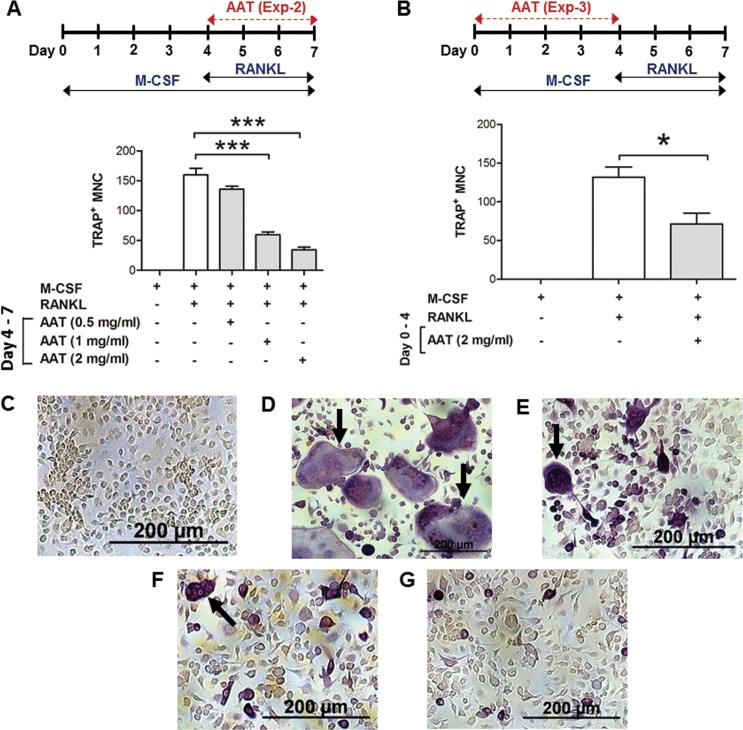

To dissect the possible mechanisms by which AAT inhibits osteoclast formation, we performed two additional sets of experiments. In one set of experiments (Exp-2 in Figures 2A, C–G), we added AAT to late-stage OCP cells from d 4–7 during osteoclast formation. As shown in Figure 2A, this AAT treatment significantly inhibited TRAP+ MNC formation. In another set of experiments (Exp-3), we added AAT only from d 0–4 during osteoclast formation. We found that AAT treatment of early-stage OCP cells (from d 0–4) also significantly decreased the number of TRAP+ MNCs (Figure 2B). These results clearly demonstrate that AAT inhibited M-CSF–induced differentiation of early-stage OCP cells into late-stage OCP cells.

Figure 2.

Effect of AAT on early-and late-stage OCP cells. (A) TRAP+ multinuclear cells, MNCs (cell number/well of 96-well cell culture plate) derived from BMM cells. Here, different concentrations of AAT as indicated were added from d 4–7 during osteoclast formation according to Exp-2. (B) TRAP+ MNCs (cell number/well of 96-well cell culture plate) derived from BMM cells. Here, AAT (2 mg/mL) was added from d 0–4 during osteoclast formation according to Exp-3. (C–G) Representative images of TRAP+ MNCs shown in (A): (C) M-CSF only (considered as negative control); (D) RANKL + M-CSF (considered as positive control); (E) RANKL + M-CSF + AAT (0.5 mg/mL); (F) RANKL + M-CSF + AAT (1 mg/mL); (G) RANKL + M-CSF + AAT (2 mg/mL). Values are means ± SEM of at least triplicate samples. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. *P <0.05, ***P <0.0001. Scale bar = 200 μm. The arrow indicates multinuclear osteoclast cells.

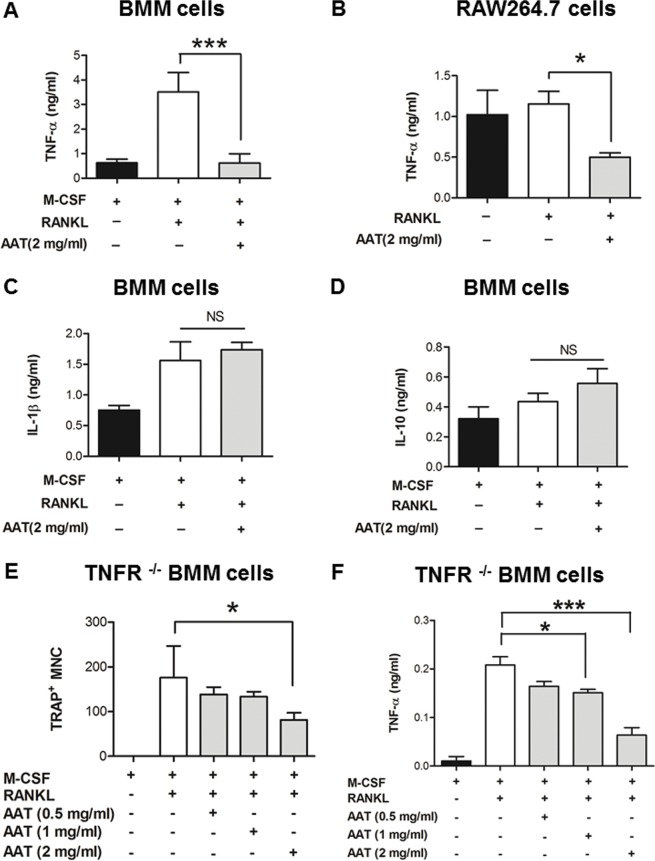

AAT Inhibited RANKL-Induced TNF-α Secretion During Late-stage Osteoclast Formation

To understand the mechanisms underlying the effect of AAT on late-stage OCP cells, we tested the effect of AAT on RANKL-induced cytokine production from d 4–7 during osteoclast formation. Our results show that AAT significantly reduced RANKL-induced TNF-α secretion during osteoclast formation using two cell systems (Figures 3A, B). However, AAT did not have a significant effect on IL-1β or IL-10 (Figures 3C, D).

Figure 3.

AAT inhibits RANKL-induced TNF-α production during osteoclast formation. (A) TNF-α concentrations in the culture medium of osteoclast cells derived from BMM cells. Here, AAT (2 mg/mL) was added from d 4–7 according to Exp-2 (which is diagrammatically mentioned in Figure 2A). (B) TNF-α concentrations in the culture medium of osteoclast cells derived from RAW267.4 cells. Here, AAT (2 mg/mL) was added during RANKL-induced osteoclast formation (d 0–6). (C–D) The concentrations of IL-1β and IL-10 in BMM cell– derived osteoclast culture medium (n = 6). (E) TRAP+ MNCs (cell number/well of 96-well cell culture plate) derived from BMM cells of TNF-α receptor knockout mice (TNFR1-/- and TNFR2-/-). Here, AAT was added from d 4–7 according to Exp-2 during osteoclast generation. (F) The concentration of TNF-α in the culture medium of osteoclast cells derived from TNF-α receptor knockout mouse BMM cells according to Exp-2. Values are means ± SEM of at least triplicate samples. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.0001; NS = nonsignificant.

A recent study has shown that AAT can significantly reduce the binding of TNF-α to TNF-α receptors (TNFR1 and TNFR2) (32). It has also been reported that RANKL induces TNF-α production (33), which stimulates RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis by an autocrine mechanism in vitro. Based on this information, we tested whether inhibition of TNF-α played a critical role in AAT-mediated inhibition of osteoclast formation. We generated osteoclasts using BMM cells from a TNF-α receptor (TNFR1 and TNFR2) deficient mouse. Our results show that inhibition of osteoclast formation required a higher dose of AAT (2 mg/mL) (Figure 3E) and that AAT significantly decreased the TNF-α level (Figure 3F). These results suggest that other pathways may be involved in the inhibition of RANKL-induced osteoclast formation.

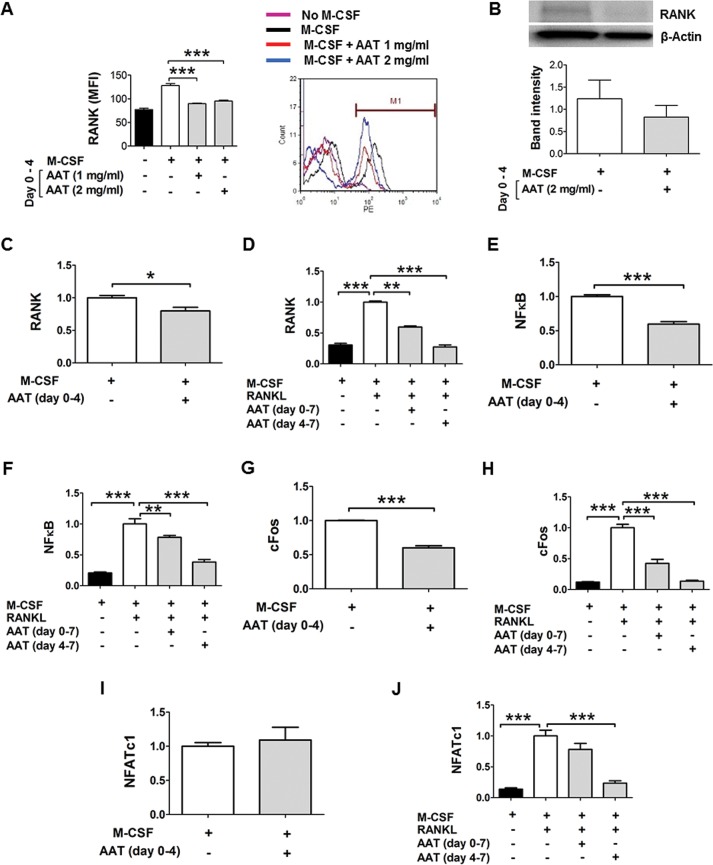

AAT Inhibited M-CSF–Induced RANK and Related Gene Expression in Early-stage and Late OCP Cells

To understand the possible mechanism underlying the effect of AAT on early-stage OCP cells, we tested the effect of AAT on M-CSF–induced RANK expression in early-stage OCP cells. We treated the BMM cells with M-CSF from d 0–4 with or without AAT. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that AAT treatment significantly decreased cell surface RANK levels at d 4 (Figure 4A). We confirmed these results in a similar experiment by Western blot analysis (Figure 4B). We also showed that AAT treatment significantly reduced RANK gene expression in both early (Figure 4C) and late stages of the induction (Figure 4D). To further understand the mechanism underlying the inhibition of RANK by AAT, we tested the effect of AAT treatment on the gene expression of transcription factors that contribute to RANK gene expression by quantitative RT-PCR. First, we showed that AAT treatment significantly inhibited NF-k B gene expression (Figures 4E, F). Since M-CSF–induced cFos plays an essential role in the upregulation of RANK expression (34), we tested the effect of AAT on M-CSF–induced cFos gene expression. Results from these experiments show that AAT significantly downregulated M-CSF–induced (Figure 4G) and RANKL-induced (Figure 4H) cFos mRNA levels. We also detected NFATc1 mRNA levels and showed that AAT treatment (2 mg/mL) significantly decreased NFATc1 gene expression (Figures 4I, J). These results demonstrate that AAT has inhibitory effects on M-CSF–induced RANK receptors and related gene expression in early-stage OCP cells.

Figure 4.

AAT inhibits RANK and related gene expression in OCP cells. BMM cells were treated with M-CSF for 4 d in the presence or absence of AAT as indicated and stimulated by RANKL (Day 4–7). (A) Cell surface RANK receptors detected by flow cytometry expression. Left panel, the mean fluorescence intensity of cell surface RANK receptor levels at d 4. (Right panel) The representative flow cytometry histogram (n = 5). (B) Western blot analysis for detection of total RANK protein at d 4. (Upper panel) Representative image of Western blot. (Lower panel) RANK protein band intensities of four individual experiments. Band intensity was analyzed with Image J software. (C–J) Relative gene expression (mRNA) levels (fold changes) detected by quantitative real-time PCR. (C) RANK at d 4. (D) RANK at d 7. (E) NFk B at d 4. (F) NFk B at d 7. (G) cFos at d 4. (H) cFos at d 7. (I) NFATc1 at d 4. (J) NFATc1 at d 7. Values are means ± SEM of at least triplicate samples. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Student t test was used to compare two samples. *P <0.05, **P <0.001, ***P <0.0001.

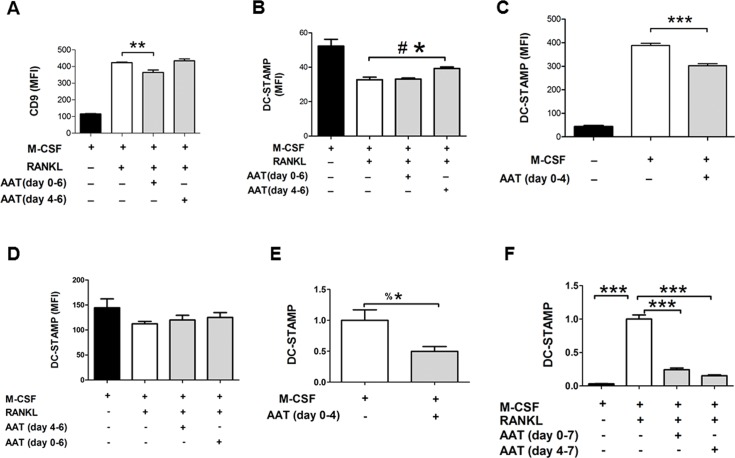

AAT Inhibited RANKL-Induced CD9 Expression and DC-STAMP Gene Expression in OCP Cells

Since cell surface levels of CD9 and internalization of DC-STAMP are critical for cell-cell fusion and they are RANK/RANKL interaction dependent (13), we investigated the effect of AAT on cell surface CD9 and DC-STAMP during RANKL-induced osteoclast formation by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 5A, AAT treatment from d 0–6 significantly decreased cell surface CD9 expression, while AAT treatment from d 4–6 did not. As CD9 expression is RANK/RANKL interaction dependent (13), these data suggest that the decrease in CD9 expression was related to inhibition of RANK due to AAT treatment started from d 0 (Figure 4A). In similar experiments, we also tested the effect of AAT on DC-STAMP cell surface expression. As shown in Figure 5B and Supplementary Figure S1, AAT treatment from d 4–6 resulted in significantly more cell surface DC-STAMP, while AAT treatment from d 0–6 did not change the level of cell surface DC-STAMP compared with the control (M-CSF plus RANKL). In addition, we tested intracellular DC-STAMP levels by permeabilizing the cells prior to flow cytometry, and observed no significant effect from AAT treatment (Figure 5D, Supplementary Figure S2). We next tested cell surface DC-STAMP levels and gene expression at 4 d after M-CSF induction (without RANKL treatment). As shown in Figures 5C and E, AAT significantly inhibited DC-STAMP expression at this stage. Similarly, inhibition of DC-STAMP gene expression was also observed in late OCP cells (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

AAT inhibits RANKL-induced CD9 and DC-STAMP expression. Osteoclast cells were generated by treating the BMM cells with M-CSF (d 0–4) and RANKL (d 4–6 or 7). Cells were treated with AAT (2 mg/mL) at the indicated time frame. (A) Cell surface CD9 levels (mean fluorescence intensity) detected by flow cytometry at d 6. (B) Cell surface DC-STAMP detected by flow cytometry at d 6. (C) Cell surface DC-STAMP detected at d 4. (D) Intracellular DC-STAMP was detected by flow cytometry at d 6 after permeabilizing the cells. (E) DC-STAMP mRNA was detected by qPCR. (F) DC-STAMP mRNA was detected by qPCR at d 7. Values are means ± SEM of at least triplicate samples. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. **P <0.001, ***P <0.0001, Student t test was used to compare two samples. #* = P <0.05 using Student t test. %* = P <0.05 using one-tail Student t test.

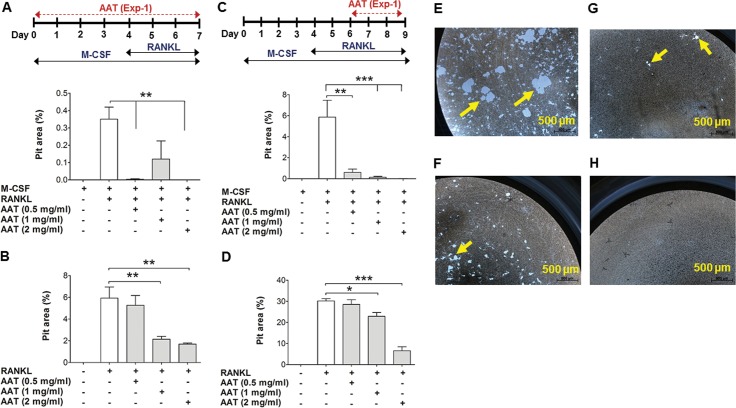

AAT Inhibited RANKL-Induced Bone Resorption by Osteoclasts

To investigate the effect of AAT on osteoclast function, we generated osteoclasts from BMM and RAW 264.7 cells on a bone biomimetic synthetic surface (96-well osteo assay surface plates). In this system, we added different concentrations of AAT during osteoclast formation from d 0–7. Results from these experiments show that AAT significantly reduced the resorption pit area (Figures 6A, B). In another set of experiments, we first generated osteoclast cells from both BMM and RAW 264.7 cells. The generated osteoclasts were harvested and plated on 96-well osteo assay surface plates with RANKL and M-CSF. After seeding the cells, we added different concentrations of AAT and cultured the cells for 3 d. Our results show that AAT dose-dependently reduced the osteoclast-associated resorption pit area (Figures 6C, D). Together, these data clearly demonstrate that AAT inhibited osteoclast function (bone resorption).

Figure 6.

AAT dose-dependently inhibits osteoclast function. (A) Percentage of pit area resorbed by osteoclast cells derived from BMM cells. Osteoclast cells were generated on 96-well osteo assay surface plate using M-CSF (d 0–7) and RANKL (d 4–7). Different concentrations of AAT as indicated were added from d 0–7 according to Exp-1 (which is diagrammatically mentioned in Figure 1A). (B) Percentage of pit area resorbed by osteoclast cells derived from RAW 264.7 cells. Cells were treated with RANKL (d 0–6) on 96-well osteo assay surface plate. Different concentration of AAT as indicated were added from d 0–6. (C) Percentage of pit area resorbed by osteoclast cells derived from BMM cells. Here, BMM cells were first treated with M-CSF (d 0–6) and RANKL (d 4–6) on tissue culture plate without AAT. At d 6, generated osteoclast cells were harvested, plated on 96-well osteo assay surface plate and treated with M-CSF, RANKL and different concentrations of AAT for an additional 3 d. (D) Percentage of pit area resorbed by osteoclast cells from RAW 264.7 cells. Cells were treated with RANKL (d 0–6) on tissue culture plate without AAT. Generated osteoclasts were harvested at d 6, plated on 96-well osteo assay surface plate and treated with RANKL and different concentrations of AAT for an additional 3 d. (E–H) Representative images of pits documented in (C): (E) RANKL + M-CSF (considered as positive control); (F) RANKL + M-CSF + AAT (0.5 mg/mL); (G) RANKL + M-CSF + AAT (1 mg/mL); (H) RANKL + M-CSF + AAT (2 mg/mL). Values are means ± SEM of at least triplicate samples. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. *P <0.05, **P <0.001, ***P <0.0001. Scale bar = 500 μm; yellow arrow indicates resorption pit.

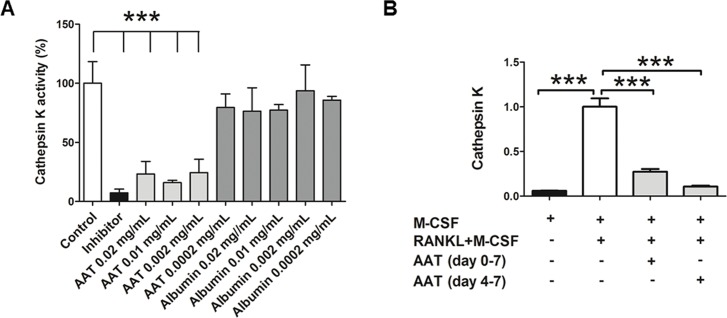

AAT Inhibited CatK Activity and RANKL-Induced CatK Gene Expression

Since CatK plays a critical role in bone resorption, we tested the effect of AAT on CatK activity. As shown in Figure 7A, AAT directly inhibited CatK activity at very low concentration conditions, while albumin as a control did not. In addition, we showed that AAT treatment significantly inhibited RNAKL-induced CatK gene expression (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

AAT inhibits CatK activity and gene expression. (A) Percentage of inhibition of CatK activity by AAT determined by CatK drug discovery kit. (B) Effect of AAT treatment (2 mg/mL) on CatK gene expression (fold changes of CatK mRNA expression) was determined by qPCR. Values are means ± SEM of at least triplicate samples. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. ***P <0.0001.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown for the first time that AAT efficiently inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclast formation and bone resorption. We have demonstrated that AAT reduces M-CSF– induced RANK receptor expression and downregulates M-CSF–induced regulatory gene expression (NF-κB and cFos). We have also shown that AAT inhibits RANKL-induced TNF-α production, CD9 expression and DC-STAMP gene expression, and CatK gene expression and activity. Together, our results uncover novel mechanisms underlying the protective effect of AAT on bone loss and indicate that AAT has therapeutic potential for the treatment of osteoporosis. AAT is a Food and Drug Administration– approved drug and is generally considered safe for the treatment of α-1 antitrypsin deficiency disease (35,36). Considering that all currently used antiresorptive drugs for the treatment of osteoporosis have side effects (5,37), the safety profile of AAT could make it an appealing candidate for the treatment of osteoporosis.

We investigated the effect of AAT on osteoclast formation and found that AAT treatment (from d 0–7) inhibited osteoclast formation efficiently. Further analysis showed that late AAT treatment (d 4–7) inhibited osteoclast formation and RANKL-induced TNF-α secretion, while early AAT treatment (d 0–4) inhibited osteoclast formation by inhibiting M-CSF–induced RANK expression. We showed by MTT assay that this efficient inhibition was not due to cell apoptosis (data not shown). These findings clearly demonstrate that AAT inhibited osteoclast formation by multiple mechanisms.

TNF-α is produced by many types of cells, including monocytes/macrophages, osteoblasts and various cancer cells, and is involved in inflammatory tissue destruction, particularly bone resorption (5). RANKL induction of osteoclastogenesis is accompanied by a rapid and transient increase in TNF-α mRNA and TNF-α release in the precursor cell, which can act as an autocrine factor in osteoclastogenesis (33,38). In the present study, we showed that AAT reduced RANKL-induced TNF-α production. One possible mechanism is that AAT inhibits ADAM17, also known as a TNF-α– converting enzyme, which cleaves and releases soluble TNF-α (39). A recent study by Bergin et al. (32) showed that AAT can reduce the binding of TNF-α to its receptors (TNFR1 and TNFR2). Since TNF-α can self-regulate its gene expression (33), blocking the binding of TNF-α to its receptors by AAT may also contribute to inhibition of TNF-α production. We also tested the effect of AAT in cells without TNF-α receptors (TNFR1 and TNFR2) and showed that a higher dose of AAT effectively inhibited osteoclast formation, indicating that blocking TNF-α receptors is not the only mechanism for the function of AAT. In fact, AAT can enter the target cells and directly interact with cellular proteins (40).

As the RANK-RANKL interaction is indispensable for osteoclast formation (18) and M-CSF induces RANK expression in early-stage osteoclast precursors, we focused on AAT effects on RANK expression. We found a significant inhibitory effect of AAT on M-CSF–induced RANK expression in early-stage OCP cells. A recent study has shown that cFos, a transcription factor, is essential for upregulation of RANK expression in osteoclast precursor cells (34). Another study showed that M-CSF upregulated cFos expression in mature osteoclasts, at least in part via transcriptional activation of the fos gene (41). Therefore, M-CSF–induced cFos expression in OCP cells is believed to play a critical role in RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. In our study, we showed that AAT inhibited M-CSF–induced cFos mRNA expression. It is possible that downregulation of cFos gene expression by AAT leads to a reduction of RANK expression on the cell surface. It has also been reported that RANKL-induced expression of NFATc1, a master regulator of osteoclast differentiation, is tightly regulated by cFos (42). In the present study, we observed a reduction of NFATc1 gene expression. Together, these data suggest that AAT inhibits osteoclast differentiation by reducing cell surface RANK expression via downregulation of the cFos gene and NF-κB gene expression.

Since the RANKL-RANK interaction plays an important role in the expression of a set of cell fusion–related cell surface proteins, including CD9 and DC-STAMP, AAT-mediated reduction of RANK can consequently lead to a reduction of CD9 and DC-STAMP. Indeed, we showed that early AAT treatment significantly reduced CD9 cells (Figure 5A). Similarly, we showed that early AAT treatment (without RANKL) also inhibited cell surface DC-STAMP levels (Figure 5C). However, we observed no or a minor effect of AAT in the condition that RANKL presents (Figures 5B, D). It is possible that RANKL-induced cell surface DC-STAMP quickly internalized as the cells fused and underwent degradation, while our methods of detection were not able to show the complex dynamics. Nonetheless, our results show that AAT clearly inhibited RANKL-induced DC-STAMP gene expression (Figure 5E). These results support our hypothesis.

To test the effects of AAT on osteoclast function, we performed pit formation studies. We generated osteoclasts on osteo assay surface plates and found a significant reduction of pit formation with AAT treatment. It is possible that the inhibitory effect of AAT on osteoclast formation led to smaller areas of pit formation. To rule out this possibility, we first generated osteoclasts and then tested the effect of AAT on their mineral resorption. Our studies show a significant reduction of pit formation in the AAT-treated group. In addition, we show that AAT inhibited the activity and gene expression of CatK. These results clearly demonstrate that AAT has an inhibitory effect on bone resorption by mature osteoclasts.

CONCLUSION

In summary, our studies provide the following novel findings: (1) AAT efficiently inhibits osteoclast formation; (2) AAT reduces M-CSF–induced expression of regulatory genes (NF-κB and cFos); (3) AAT inhibits M-CSF–induced cell surface RANK receptor expression; (4) AAT inhibits RANKL-induced TNF-α production, CD9 expression and DC-STAMP gene expression; (5) AAT inhibits osteoclast-associated bone mineral resorption; and (6) AAT inhibits the enzymatic activity and gene expression of CatK. These findings provide novel mechanisms for the protective effect of AAT on bone and strongly support that AAT has therapeutic potential for the treatment of osteoporosis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

EME is a visiting scholar from Zagazig University and is supported by a scholarship from the Egyptian government. We thank Dr. Jay Cao (US Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Research Service’s Grand Forks Human Nutrition Research Center) for his assistance with part of the gene expression studies and suggestions regarding induction of osteoclast formation.

This work was supported by a grant from the University of Florida.

Footnotes

Online address: http://www.molmed.org

Disclosure

The authors declare they have no competing interests as defined by Molecular Medicine or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and discussion reported in this paper.

Cite this article as: Akbar MA, et al. (2017) α-1 antitrypsin inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclast formation and functions. Mol. Med. 23:57–69.

References

- 1.Baron R, Hesse E. Update on bone anabolics in osteoporosis treatment: rationale, current status, and perspectives. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97:311–25. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JW, et al. Alisol-B, a novel phyto-steroid, suppresses the RANKL-induced osteoclast formation and prevents bone loss in mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;80:352–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Troen BR. Molecular mechanisms underlying osteoclast formation and activation. Exp. Gerontol. 2003;38:605–14. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(03)00069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nanes MS, Kallen CB. Osteoporosis. Sem. Nucl. Med. 2014;44:439–50. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimachi K, Kajiya H, Nakayama S, Ikebe T, Okabe K. Zoledronic acid inhibits RANK expression and migration of osteoclast precursors during osteoclastogenesis. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2011;383:297–308. doi: 10.1007/s00210-010-0596-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suda T, Takahashi N, Martin TJ. Modulation of osteoclast differentiation. Endocr. Rev. 1992;13:66–80. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-1-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacey D, et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93:165–76. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasuda H, et al. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arai F, et al. Commitment and differentiation of osteoclast precursor cells by the sequential expression of c-Fms and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB (RANK) receptors. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:1741–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.12.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishida N, et al. Large Scale Gene Expression Analysis of Osteoclastogenesis in Vitro and Elucidation of NFAT2 as a Key Regulator. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:41147–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson RS, Spiegelman BM, Papaioannou V. Pleiotropic effects of a null mutation in the c-fos proto-oncogene. Cell. 1992;71:577–86. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90592-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takayanagi H, et al. Induction and activation of the transcription factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) integrate RANKL signaling in terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:889–901. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xing L, Xiu Y, Boyce BF. Osteoclast fusion and regulation by RANKL-dependent and independent factors. World J. Orthop. 2012;3:212–22. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v3.i12.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kukita T, et al. RANKL-induced DC-STAMP is essential for osteoclastogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:941–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burgess TL, et al. The ligand for osteoprotegerin (OPGL) directly activates mature osteoclasts. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145:527–38. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.3.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blair HC, Teitelbaum SL, Ghiselli R, Gluck S. Osteoclastic bone resorption by a polarized vacuolar proton pump. Science. 1989;245:855–57. doi: 10.1126/science.2528207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003;423:337–42. doi: 10.1038/nature01658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wada T, Nakashima T, Hiroshi N, Penninger JM. RANKL-RANK signaling in osteoclastogenesis and bone disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2006;12:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mundy GR. Osteoporosis and inflammation. Nutr. Rev. 2007;65:S147–51.. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romas E, Gillespie MT. Inflammation-induced bone loss: can it be prevented? Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2006;32:759–73. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janciauskiene SM, et al. The discovery of alpha1-antitrypsin and its role in health and disease. Respir. Med. 2011;105:1129–39. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu YQ, et al. Alpha(1)-antitrypsin gene therapy modulates cellular immunity and efficiently prevents type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006;17:625–34. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma H, et al. Intradermal alpha1-antitrypsin therapy avoids fatal anaphylaxis, prevents type 1 diabetes and reverses hyperglycaemia in the NOD mouse model of the disease. Diabetologia. 2010;53:2198–2204. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1829-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song S, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated alpha-1 antitrypsin gene therapy prevents type I diabetes in NOD mice. Gene Ther. 2004;11:181–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grimstein C, et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin protein and gene therapies decrease autoimmunity and delay arthritis development in mouse model. J. Transl. Med. 2011;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grimstein C, et al. Combination of alpha-1 antitrypsin and doxycycline suppresses collagen-induced arthritis. J. Gene Med. 2010;12:35–44. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shapiro L, Pott GB, Ralston AH. Alpha-1-antitrypsin inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1. FASEB J. 2001;15:115–22. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0311com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akbar MA, et al. Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Gene Therapy Ameliorates Bone Loss in Ovariectomy-Induced Osteoporosis Mouse Model. Hum. Gene Ther. 2016;27:679–86. doi: 10.1089/hum.2016.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akbar MA, et al. Transplantation of Adipose Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell (ATMSC) Expressing Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Reduces Bone Loss in Ovariectomized Osteoporosis Mice. Hum. Gene Ther. 2016;28:179–89. doi: 10.1089/hum.2016.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Kobayashi Y, Suda T. Generation of osteoclasts in vitro, and assay of osteoclast activity. Methods Mol. Med. 2007;135:285–301. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-401-8_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collin-Osdoby P, Yu X, Zheng H, Osdoby P. RANKL-mediated osteoclast formation from murine RAW 264.7 cells. Methods Mol. Med. 2003;80:153–66. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-366-6:153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergin DA, et al. The circulating proteinase inhibitor alpha-1 antitrypsin regulates neutrophil degranulation and autoimmunity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6:217ra211. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou W, Hakim I, Tschoep K, Endres S, Bar-Shavit Z. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediates RANK ligand stimulation of osteoclast differentiation by an autocrine mechanism. J. Cell. Biochem. 2001;83:70–83. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arai A, et al. Fos plays an essential role in the upregulation of RANK expression in osteoclast precursors within the bone microenvironment. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:2910–17. doi: 10.1242/jcs.099986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrache I, Hajjar J, Campos M. Safety and efficacy of alpha-1-antitrypsin augmentation therapy in the treatment of patients with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Biologics. 2009;3:193–204. doi: 10.2147/btt.2009.3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohanka M, Khemasuwan D, Stoller JK. A review of augmentation therapy for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2012;12:685–700. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.676638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hough F, et al. The safety of osteoporosis medication. S. Afr. Med. J. 2014;104:279–82. doi: 10.7196/samj.7505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zou W, Amcheslavsky A, Takeshita S, Drissi H, Bar-Shavit Z. TNF-α expression is transcriptionally regulated by RANK ligand. J. Cell. Physiol. 2005;202:371–78. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergin DA, et al. alpha-1 Antitrypsin regulates human neutrophil chemotaxis induced by soluble immune complexes and IL-8. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:4236–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI41196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang B, et al. α1-Antitrypsin protects β-cells from apoptosis. Diabetes. 2007;56:1316–23. doi: 10.2337/db06-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao GQ, Itokawa T, Paliwal I, Insogna K. CSF-1 induces fos gene transcription and activates the transcription factor Elk-1 in mature osteoclasts. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2005;76:371–78. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-0099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song I, et al. Regulatory mechanism of NFATc1 in RANKL-induced osteoclast activation. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2435–40. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.