Abstract

Mammalian Na+/Ca2+ exchangers, NCX1 and NCX3, generate splice variants, whereas NCX2 does not. The CBD1 and CBD2 domains form a regulatory tandem (CBD12), where Ca2+ binding to CBD1 activates and Ca2+ binding to CBD2 (bearing the splicing segment) alleviates the Na+-induced inactivation. Here, the NCX2-CBD12, NCX3-CBD12-B, and NCX3-CBD12-AC proteins were analyzed by small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass-spectrometry (HDX-MS) to resolve regulatory variances in the NCX2 and NCX3 variants. SAXS revealed the unified model, according to which the Ca2+ binding to CBD12 shifts a dynamic equilibrium without generating new conformational states, and where more rigid conformational states become more populated without any global conformational changes. HDX-MS revealed the differential effects of the B and AC exons on the folding stability of apo CBD1 in NCX3-CBD12, where the dynamic differences become less noticeable in the Ca2+-bound state. Therefore, the apo forms predefine incremental changes in backbone dynamics upon Ca2+ binding. These observations may account for slower inactivation (caused by slower dissociation of occluded Ca2+ from CBD12) in the skeletal vs the brain-expressed NCX2 and NCX3 variants. This may have physiological relevance, since NCX must extrude much higher amounts of Ca2+ from the skeletal cell than from the neuron.

Introduction

The properties of Ca2+-binding proteins that participate in Ca2+-dependent regulation of distinct cell-signaling pathways are controlled by tissue-specific expression and alternative splicing of closely related genes1. The isoform-dependent and alternative splicing-dependent modification of Ca2+-binding regulatory domains are especially important for Ca2+-transporting proteins operating in excitable tissues1–3, since feedback interactions of Ca2+ with allosteric regulatory domains dynamically modulate the Ca2+-transport rates in accordance with dynamic changes in cellular Ca2+ oscillations (e.g., in cardiomyocytes during the action potential)1, 3–5. Despite the fundamental importance of this issue, the structure-dynamic determinants governing the isoform-dependent and alternative splicing-dependent modification of regulatiory specificity in Ca2+-binding domains remain poorly understood2, 6.

Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) proteins serve as a major route for Ca2+ extrusion from cells3, 4. In mammals, three gene isoforms (SLC8A1, SLC8A2, and SLC8A3) of NCX proteins (NCX1, NCX2, and NCX3) and their splice variants are expressed in a tissue-specific manner, while exhibiting distinct regulatory phenotypes (Fig. 1)7–10. The activity of NCX proteins is “secondarily” modulated by cytosolic Na+ and Ca2+ 8–10. In mammals, an increase in cytosolic [Na+] usually inactivates NCX, whereas an increase in cytosolic [Ca2+] usually activates NCX3, 4, 6. However, the appearance of these regulatory modes as well as their strength and duration vary in an isoform and splice variant-dependent manner, since the regulatory features of a given isoform/splice variant must match the tissue-specific contributions of NCX to the dynamic handling of Ca2+ homeostasis in distinct cell-types7, 9, 11. For example, in some isoforms and splice variants, an increase in the cytosolic [Ca2+] can alleviate Na+-dependent inactivation, whereas in others, Ca2+ cannot alleviate Na+-dependent inactivation, or the regulatory mode of Na+-dependent inactivation does not exist at all7, 9, 11, 12.

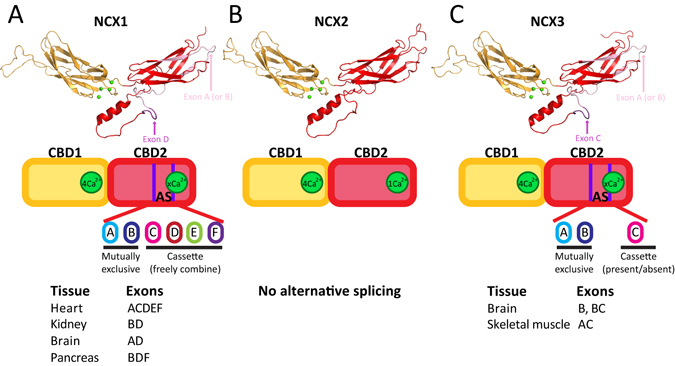

Figure 1.

Structure and alternative splicing of NCX-CBD12 isoforms. The models of NCX1-CBD12-AD (brain splice variant) (A), NCX2-CBD12 (B), and NCX3-CBD12-AC (C) are presented as cartoons. CBD1 is in orange and CBD2 is in red. Four Ca2+ ions bound to CBD1 are presented as green spheres. The alternative splicing schemes of NCX1 (A), NCX2 (B), and NCX3 (C) are presented below the models.

NCX1 is universally distributed, practically in every mammalian cell, although the NCX1 splice variants are selectively expressed in a tissue-specific manner (Fig. 1A)8, 10. Alternative splicing of NCX1 results in at least 17 splice variants, where either exon A or exon B (mutually exclusive exons) can be freely combined with cassette exons (C, D, E, and F) (Fig. 1A)3, 4, 8, 10. In general, exon-A-containing NCX1 splice variants are mainly expressed in excitable tissues (e.g., cardiomyocytes, neurons), whereas exon-B-containing NCX1 splice variants are mainly expressed in non-excitable tissues (e.g., pancreas, kidney) (Fig. 1A)3, 4, 8, 10. NCX2 is predominantly expressed in the brain and spinal cord, but it can also be found in the gastrointestinal tract and kidney tissues. NCX2 does not undergo alternative splicing (Fig. 1B). NCX3 is predominantly expressed in the brain and skeletal muscle, but it can also be found in osseous tissue and the immune system8, 10, 11, 13. Alternative splicing of NCX3 results in at least 5 splice variants and involves the expression of either exon A or exon B (mutually exclusive exons) in the presence or absence of an additional exon C (Fig. 1C)8, 10, 11, 13. Exon-A-containing NCX3 splice variants are mainly expressed in skeletal muscle, whereas exon-B-containing NCX3 splice variants are mainly expressed in the brain (Fig. 1C)11.

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic NCX proteins contain ten transmembrane helices (TM1–10), where the ion-binding pocket selectively binds either one Ca2+ or three Na+ ions and transports them in separate steps14–17. Eukaryotic (but not prokaryotic) NCX proteins contain a large cytosolic loop between TM5 and TM6, mainly composed of two Ca2+-binding domains, CBD1 and CBD218. The two CBDs form a head-to-tail attached two-domain tandem (termed CBD12) through a very short interdomain linker (Fig. 1)18, 19. The Ca2+-dependent activation of NCX1 results from Ca2+ binding to CBD112, whereas the Ca2+-dependent alleviation of Na+-induced inactivation results from Ca2+ binding to CBD212, 20, 21. Notably, the Na+-dependent inactivation of NCX is due to Na+ interaction with the ion-transport domains of NCX and not with CBD1222, 23, although Ca2+ binding to NCX1-CBD2 somehow relieves the Na+-induced inactivation via propagation of an allosteric signal over a large distance from CBD12 to transport domains6.

NMR18 and X-ray crystallography20, 24 studies revealed that CBD1 and CBD2 share a similar structure, exhibiting an immunoglobulin-like β-sandwich structure with seven antiparallel β-strands (Fig. 1). CBD1 contains four Ca2+ binding sites, capable of high-affinity Ca2+ sensing (Kd < 1 µM) in all NCX orthologs, isoforms, and splice variants6, 21, 24–26. The Ca2+ binding sites of CBD1 are located at its C-terminal tip, near the CBD1-CBD2 interface (Fig. 1)19, 24. In contrast, the number of Ca2+ binding sites at CBD2 varies from zero to three, depending on the specific ortholog, isoform, and splice variant (Fig. 1)21, 25, 26. The affinity for Ca2+ binding at CBD2 is rather low, ranging from ~5 to ~200 μM21, 23, 25, 26. Notably, alternative splicing of NCX (described in detail above) takes place only at CBD2 and involves the Ca2+ binding sites18, 21. Therefore, in A-exon-containing NCX1 variants, CBD2 binds two Ca2+ ions, whereas in B-exon-containing NCX1 variants, CBD2 does not bind Ca2+ ions (Fig. 1A)21, 25. Since Ca2+ binding to CBD2 alleviates Na+-induced inactivation, this effect of Ca2+ is only observed in A-exon-containing NCX1 variants7, 12, 21. In NCX2, CBD2 binds only one Ca2+ ion with very low affinity (Fig. 1B)21, 26. Since NCX2 does not exhibit any Na+-dependent inactivation, the Ca2+-dependent alleviation of Na+-induced inactivation is functionally irrelevant with NCX29. In NCX3, A-exon-containing variants do not bind Ca2+ ions at CBD2, whereas B-exon-containing variants bind three Ca2+ ions at CBD2 (Fig. 1C)26. Intriguingly, NCX3-AC (which does not bind Ca2+ at CBD2) was shown to exhibit less Na+-dependent inactivation compared with NCX3-B (which does bind Ca2+ at CBD2) in electrophysiological studies11.

Recent studies using diverse biophysical, biochemical, and structural methods have identified synergistic interactions between the CBDs that shape the dynamic range and kinetic features of Ca2+-dependent regulation in splice variants of NCX1, thereby providing the insights into the mechanisms underlying CBD interactions in isolated CBD12 and full-size NCX118–21, 24–32. These studies have shown that the isolated preparations of CBD12 largely represent the Ca2+ sensitivity and kinetics of Ca2+-dependent regulation in their matching of full-size NCX isoforms and splice variants7, 25, 30. Therefore, isolated CBD12 serves as an ideal model for investigating the structure-dynamic mechanisms underlying the allosteric regulation specificities in NCX isoforms and splice variants. The interactions between CBD1 and CBD2 in the context of CBD12 results in increased affinity for Ca2+ at CBD1 and slow dissociation of an “occluded” Ca2+ ion from CBD125, 27. In addition, alternative splicing at CBD2 not only affects the Ca2+ binding affinity and capacity at CBD2—it also affects the Ca2+ interactions with CBD1, establishing up to 50-fold differences both in the Ca2+ binding affinity and Ca2+ off-rates in the cardiac (ACDEF), brain (AD), and kidney (BD) splice variants of NCX125, 27. Using 45Ca2+ equilibrium binding and stopped-flow kinetic assays, we have recently demonstrated that NCX2 and NCX3 also exhibit alternative-splicing dependent synergistic interactions between the CBDs, similarly to NCX126. NCX3-CBD12 splice variants exhibit similar Ca2+ affinity at CBD1, but the dissociation rate of the occluded Ca2+ ion is ~10-fold slower in skeletal muscle (AC) than in the brain (B) variants26. These differences in Ca2+ binding affinity and the Ca2+ off-rates at the primary allosteric sensor (CBD1) may have physiological relevance for diversifying regulatory responses in full-size NCX variants expressed in a tissue-specific manner1–3, 6.

X-ray crystallography revealed that Ca2+ binding to CBD1 results in Ca2+ occlusion and tethering of CBD1 and CBD2 through the formation of a hydrogen-bonded salt-bridge network at the two-domain interface, yielding a more stable structure6, 19. The crystallographic structures of CBD12 variants of NCX1, exhibiting different regulatory properties, show nearly identical interdomain angles between CBD1 and CBD2 and thus, global CBD alignment does not seem to shape regulatory specificities in NCX1 splice variants6, 19. In line with this notion, small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) studies revealed that Ca2+ binding and occlusion at CBD1 of NCX1-CBD12 splice variants induces a shift towards narrowly distributed elongated conformations, as predicted by the population shift mechanism28. This population shift of conformational states is essential for regulation, thereby representing a common mechanism for NCX1 splice variants regardless of their regulatory specificity28. Finally, hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass-spectrometry (HDX-MS) analyses of NCX1-CBD12 splice variants have shown that Ca2+ binding to all tested variants mainly rigidifies the backbone dynamics of CBD2 (and not that of CBD1), where the alternative splicing of CBD2 secondarily modifies the strength and expansion of rigidification throughout CBD229, 31. Importantly, the Ca2+-induced effects on CBD2 backbone dynamics correlate well with the regulatory specificity found in the matching splice variants of full-size NCX1s29, 31.

Thus far, NCX1 splice variants share a common mechanism for the initial decoding of the regulatory signal upon Ca2+ occlusion and tethering of CBDs (i.e., through the population shift mechanism), whereas alternative splicing of CBD2 controls the propagation and strength of Ca2+-dependent rigidification and thereby, diversifies the regulatory response28, 29, 31. Currently it is unclear to what extent (if at all) the above-described mechanisms are also valid for NCX2 and NCX3 splice variants and how the exons control the CBD dynamics as related to shaping the regulatory specificity in a given isoform/splice variant. To overcome this gap, here we analyzed the apo and Ca2+-bound forms of isolated NCX2-CBD12, NCX3-CBD12-AC, and NCX3-CBD12-B proteins with SAXS19, 28, 29 and HDX-MS29, 31 in order to identify their conformational dynamics and the effect of alternative splicing. The present analysis reveals a general mechanism for regulatory coupling associated with Ca2+ interactions with regulatory CBD domains of NCX1, NCX2, and NCX3 isoforms and their splice variants, where the dynamic effects of alternative splicing on conformational dynamics of the two-domain regulatory tandem (CBD12) control the contributions of a given isoform/splice variant to dynamic handling of cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations in distinct cell types.

Results

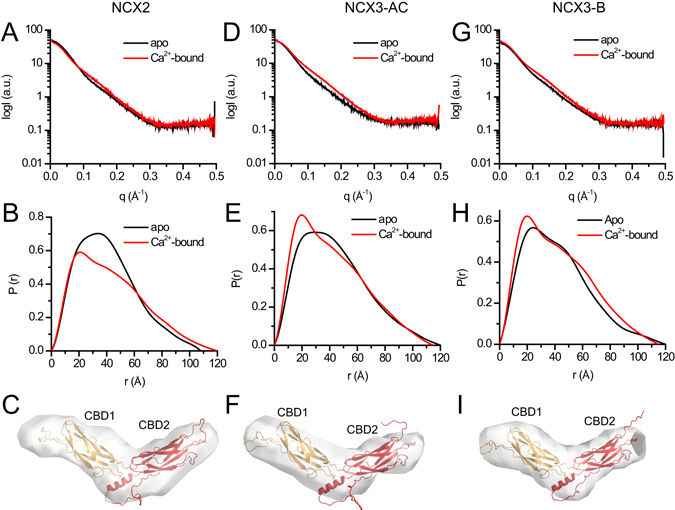

Global SAXS parameters of CBD12 proteins

To determine the low-resolution structure-dynamic features of NCX-CBD12 isoforms in solution as well as to resolve the effect of ligand binding on the global conformational states, SAXS was used (Fig. 2, Table 1)33. In all the examined proteins (NCX2-CBD12, NCX3-CBD12-AC, and NCX3-CBD12-B), the Ca2+-bound form exhibited similar Rg and Dmax values, with PDDF, which represents an elongated conformation (Table 1, Fig. 2B,E,H). The Porod volumes of all the Ca2+-bound proteins were similar and matched the volume predicted for a monomeric protein, as previously shown for NCX1-CBD12 (Table 1)28. However, in the apo form, the Porod volume matched a volume that is intermediate between a dimer and a monomer (Table 1). Therefore, we pursued further modelling only for the Ca2+-bound forms. All three proteins examined here, display similar, elongated molecular envelopes (Fig. 2C,F,I). The CBD12 homology models, based on the crystal structure of NCX1-CBD12-E454K, fit well in the molecular envelopes in all proteins examined here (Fig. 2C,F,I). Taking this into account, along with the low normalized shape discrepancy (NSD) of the models (Table 1) and the features observed in the PDDFs of all three proteins in the Ca2+-bound state (Fig. 2B,E,H), it can be assumed that NCX2-CBD12, NCX3-CBD12-AC, and NCX3-CBD12-B exhibit a very similar elongated conformation in a relatively rigid state in solution33.

Figure 2.

Ab-initio modelling of CBD12 from NCX2 and NCX3. (A,D,G) Experimental SAXS curves of CBD12 from NCX2 (A), NCX3-AC (D), and NCX3-B (G) in the presence (red) and absence (black) of Ca2+. (B,E,H) Paired-distance distribution functions of CBD12 from NCX2 (B), NCX3-AC (E), and NCX3-B (H) in the presence (red) and absence (black) of Ca2+ as determined using GNOM. (C,F,I) Ab-initio model of CBD12 from NCX2 (C), NCX3-C (F), and NCX3-B (I) in solution in the presence of Ca2+. The homology model of CBD12 was fit into the molecular envelope using SUPCOMB. CBD1 and CBD2 are presented as orange and red cartoons, respectively.

Table 1.

.

| Sample | NCX2-CBD12 | NCX2-CBD12-AC | NCX2-CBD12-B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand | 10 mM Ca2+ | 10 mM EDTA | 10 mM Ca2+ | 10 mM EDTA | 10 mM Ca2+ | 10 mM EDTA |

| Data collection parameters | ||||||

| Beamline | ESRF BM29 | |||||

| Beam geometry (mm2) | 0.5 × 0.5 | |||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0 | |||||

| Q range (Å−1) | 0.0025–0.5 | |||||

| Exposure time per frame (seconds)1 | 1 | |||||

| Concentration range (mg/ml) | 1.5–10 | 1.5–11.5 | 1.5–11.25 | |||

| Temperature (°C) | 5 | |||||

| Structural parameters | ||||||

| Rg (Å) [from P(r)]2 | 34.9 ± 0.01 | 32.5 ± 0.007 | 33.9 ± 0.006 | 35.0 ± 0.01 | 34.1 ± 0.007 | 33.5 ± 0.01 |

| Rg (Å) (from Guinier)2 | 32.6 ± 0.1 | 31.5 ± 0.2 | 32 ± 0.1 | 36.2 ± 0.4 | 32.9 ± 0.1 | 33.5 ± 0.3 |

| Dmax (Å)3 | 120 ± 12 | 108 ± 11 | 115 ± 12 | 120 ± 12 | 115 ± 12 | 120 ± 12 |

| Porod volume [from P(r)] (103 Å3) | 45.9 | 70.0 | 39.5 | 72.5 | 40.5 | 56.3 |

| NSD4 | 0.85 ± 0.04 | NA | 0.81 ± 0.05 | NA | 0.81 ± 0.05 | NA |

| χ2 (EOM) | 1.5 | NA | 0.65 | NA | 0.66 | NA |

| Software employed | ||||||

| Primary data reduction | AUTOMAR | |||||

| Data processing | PRIMUS | |||||

| Modelling | DAMMIF, EOM | |||||

1Ten frames were measured for each sample. 2±S.E. 3±10% (estimated range). 4NSD, normalized shape discrepancy for DAMMIF calculation.

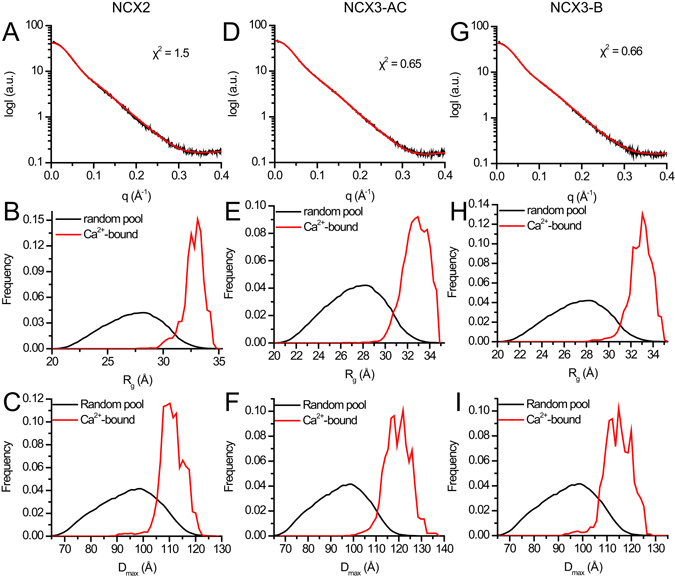

Ensemble optimization method (EOM) SAXS analysis of CBD12 proteins

To further assess the conformational distributions of the examined proteins, we performed EOM analysis (Fig. 3). The advantage of EOM analysis is that it can describe the conformational distribution of a molecule instead of representing the molecule using global parameters that do not account for conformational heterogeneity28, 34. The selected ensembles fit the experimental data well, as judged by the low χ2 values (Table 1). In all three proteins tested here (NCX2-CBD12, NCX3-CBD12-AC, and NCX3-CBD12-B), the conformational distributions are narrow (Fig. 3B,E,H) and biased towards the most elongated conformations (Fig. 3C,F,I), thereby implying a rigid and elongated conformation of Ca2+-bound species for all CBD12 variants in solution. Notably, the effect of Ca2+ results from binding to CBD1 and not CBD2, since NCX3-CBD12-AC exhibits these properties despite the fact that it does not bind Ca2+ at CBD226. These features of NCX2-CBD12, NCX3-CBD12-AC, and NCX3-CBD12-B are somewhat similar to mammalian NCX1-CBD12 splice variants analyzed previously28. Taken together, the data supports the notion that Ca2+-binding to the primary (high-affinity) sensor of the CBD12 tandem either in NCX1, NCX2, or NCX3 results in a Ca2+-induced population shift of preexisting conformational states, where more elongated conformational states become more populated (Fig. 3)28.

Figure 3.

EOM analyses of CBD12 from NCX2 and NCX3. (A,D,G) Experimental SAXS curve and EOM fit of CBD12 from NCX2 (A), NCX3-AC (D), and NCX3-B (G) in the presence of Ca2+. (B,E,H) Random Rg pool (black line) and EOM-selected ensemble (red line) distributions of NCX2-CBD12 (B), NCX3-CBD12-AC (E), and NCX3-CBD12-B (H). (C,F,I) Random Dmax pool (black line) and EOM-selected ensemble (red line) distributions of NCX2-CBD12 (C), NCX3-CBD12-AC (F), and NCX3-CBD12-B (I).

Effect of alternative splicing on HDX profiles in NCX3-CBD12

The SAXS analysis, described above, revealed similar behavior in all NCX-CBD12 isoforms and splice variants tested here, exhibiting a rigid and elongated conformation in the presence of Ca2+ (Figs 2 and 3). Therefore, it remains unclear how Ca2+-dependent NCX regulation is diversified between the different isoforms and splice variants. To better understand the differential conformational dynamics of NCX-CBD12 isoforms and splice variants, the isolated preparations of NCX2-CBD12 and NCX3-CBD12 proteins were analyzed in the apo and Ca2+-bound states by HDX-MS29, 31.

The identified peptic peptides that were used for HDX-MS analysis are shown in Figure S1. The deuterium uptake levels of each protein in the apo state (Figure S2A,C, and E) or in the Ca2+-bound state (Figures S2B,D, and F) are overlaid on the protein structures as color-coded heat maps. It is not feasible to directly compare the deuterium exchange levels between proteins with different sequences because amino acid side chains affect the deuterium uptake rates and different peptic peptides are generated. Therefore, a comparison between NCX2-CBD12 and NCX3-CBD12 variants is not feasible, whereas a comparison between NCX3-CBD12-AC and NCX3-CDB12-B is possible within regions with the same sequences (i.e., outside the alternative splicing regions).

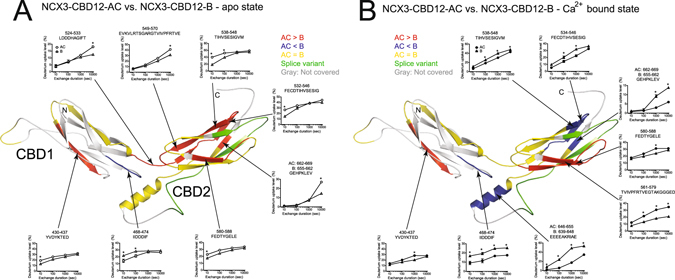

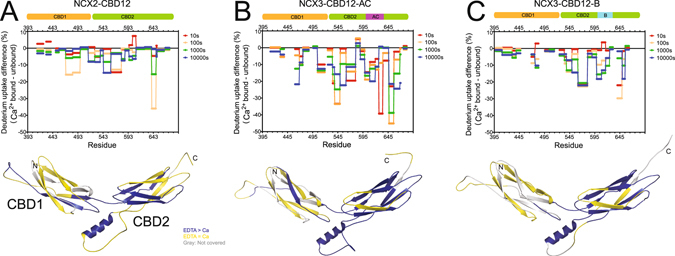

To characterize the effect of alternative splicing on the structural dynamics of NCX3-CBD12, we compared the deuterium exchange levels of NCX3-CBD12-AC and NCX3-CDB12-B using peptic peptides denoted as blue bars in Figure S1B. In both the apo and Ca2+-bound states, a few regions of the backbone dynamics considerably differ (Fig. 4) despite the predicted structural similarity and the similar global behavior of the analyzed proteins in solution (Figs 1, 2 and 3). In the apo state, NCX3-CBD12-AC exhibits a higher deuterium uptake than does NCX3-CBD12-B in CBD1, CBD1-CBD2 linker, and CBD2 (Fig. 4A, red regions). On the other hand, the CBD1 EF loop (peptide 468–474), which participates in forming the Ca2+-binding sites and interacts with the α-helical region of CBD219, exhibits less uptake in NCX3-CBD12-AC as compared with NCX3-CBD12-B (Fig. 4A, blue region). This result reveals that the alternative splicing segment (Fig. 1, located on CBD2) affects the folding stability of CBD12 in the apo state and thus, may predefine distinct conformational responses of CBDs to Ca2+-binding in a given splice variant6, 29, 31.

Figure 4.

Effect of alternative splicing on the conformational dynamics of NCX3-CBD12. Deuterium uptake differences between NCX3-AC and NCX3-B in the apo form (A) or in the Ca2+-bound form (B) are color-coded onto the model of NCX3-AC. Regions with similar deuterium uptake are yellow, regions with higher deuterium uptake in NCX3-AC are red, and regions with higher deuterium uptake in NCX3-B are blue. The alternative splicing region is in green and regions not covered by the detected peptic peptides are in gray. The uptake plots of the indicated peptic peptides are presented. Error bars represent SEM, * indicated p < 0.05 as analyzed by t-test.

Ca2+ binding alters the backbone dynamic differences between the two NCX3-CBD12 variants (Fig. 4B). The deuterium uptake levels within the CBD1-CBD2 linker and nearby regions of CBD2 become similar between NCX3-CBD12-AC and NCX3-CDB12-B (Fig. 4B, yellow regions). The CBD1-CBD2 linker is rigidified to a similar extent in both splice variants (Fig. 4B), consistent with similar conformational distributions observed in the EOM SAXS analysis (Fig. 3); the NCX3-CBD12-AC linker is no longer more dynamic than the NCX3-CBD12-B linker upon Ca2+ binding.

The α-helical region of CBD2 [peptides 646–655 (AC) or 639–648 (B)], adjacent to the CBD1 Ca2+-binding sites, exhibits markedly lower deuterium uptake in NCX3-CBD12-AC as compared with NCX3-CBD12-B in the Ca2+-bound state (Fig. 4B). In addition, the C-terminal tip of CBD2 [peptides 538–548, 534–546, 662–669 (AC) and 655–662 (B)] exhibits a lower deuterium uptake in NCX3-CBD12-AC compared with NCX3-CBD12-B in the Ca2+-bound state (Fig. 4B). This finding is especially peculiar in light of a previous analysis demonstrating that NCX3-CBD12-AC lacks the capacity for Ca2+ binding at CBD2, whereas NCX3-CBD12-B binds three Ca2+ ions at the C-terminal tip of CBD230, 34. Overall, the effect of Ca2+ binding on backbone rigidification is more marked in NCX3-CBD12-AC as compared with NCX3-CBD12-B (Fig. 4), which may account for the observed differences in the dissociation kinetics of occluded Ca2+ at the interface of CBD1 and CBD2 in NCX3 splice variants26.

HDX profiles of NCX2-CBD12 and NCX3-CBD12

Although a direct comparison of deuterium uptake levels between NCX2-CBD12 and NCX3-CBD12 variants is not feasible, we can compare the regions affected by Ca2+ binding.

To better envisage the Ca2+-dependent changes in backbone dynamics, we plotted the difference in deuterium uptake as a function of residue at different deuterium uptake durations, and the Ca2+-induced deuterium uptake changes were also color-coded onto the CBD12 model structures (Figs 5 and S3). When examining the effect of Ca2+-binding, all three tested proteins exhibit markedly reduced deuterium uptake throughout CBD1 and CBD2 (Figs 5 and S3). This is true even for NCX3-CBD12-AC, which does not bind Ca2+ at CBD226. This supports the notion that occupation of the high-affinity primary sensor at CBD1 in NCX2 and NCX3 plays a key role in Ca2+-dependent stabilization of CBD2 due to conformational stabilization of the two-domain interface and the interdomain linker upon Ca2+ binding and occlusion at the primary sensor at CBD1. A similar structure-dynamic module was suggested for NCX1-CBD12 splice variants based on the HDX-MS analysis29, 31.

Figure 5.

Effect of Ca2+ binding on NCX2-CBD12 and NCX3-CBD12 dynamics. Deuterium uptake differences between the Ca2+-bound form and the apo form as a function of residue at different time points as indicated are plotted for NCX2-CBD12 (A), NCX3-CBD12-AC (B), and NCX3-CBD12-B (C). The data are also qualitatively depicted on the models of NCX2-CBD12 (A), NCX3-CBD12-AC (B), and NCX3-CBD12-B (C). Regions with lower deuterium uptake in the Ca2+-bound form are in blue, regions with similar deuterium uptake in the Ca2+-bound form and apo form are in yellow, and regions not covered by the detected peptic peptides are in gray.

The interdomain CBD1-CBD2 linker (peptide 513–525 in NCX2 and 524–533 in NCX3) exhibits lower deuterium uptake upon Ca2+-binding in all three proteins analyzed here (Figs 5 and S3). This evidence is consistent with the rigid conformations observed in the EOM SAXS analysis (Fig. 2). Similarly to NCX1-CBD12 splice variants29, 31, the presently analyzed NCX2 and NCX3 splice variants also exhibit the rigidification of the two-domain interface (including the CBD1-CBD2 linker) upon Ca2+ binding, meaning that all NCX1, NCX2, and NCX3 isoform/splice variants, tested until now, share a common mechanism for the initial decoding of regulatory Ca2+ signals.

Notably, in all the examined proteins, the α-helical region at the domain’s interface (in the vicinity of the alternative splicing segment, Fig. 1) (peptide 639–647 in NCX2 and 646–655 in NCX3) exhibits lower deuterium uptake in the Ca2+-bound state (Figs 5 and S3). This could be important for exon-controlled stabilization of Ca2+-dependent CBD tethering, which in turn, affects the strength of Ca2+ binding and the off-rates of occluded Ca2+ dissociation from CBD1.

Discussion

Functional contributions of NCX2 and NCX3 variants to physiological and pathological settings have been documented13, 34, while underscoring the importance of tissue-specific expression and regulatory diversities exhibited by these isoforms and splice variants3, 4, 6, 9, 11. The goal of the present work was to determine the structure-dynamic basis underlying the previously reported regulatory diversities in an isolated CBD12 model and full-size NCX variants in order to formulate the principal mechanism underlying the regulatory diversity in NCX proteins. To this end, the NCX2-CBD12, NCX3-CBD12-AC, and NCX3-CBD12-B proteins were analyzed here by using SAXS and HDX-MS techniques.

As summarized above, the diversity in allosteric regulation of NCX proteins is puzzling at first glance. Some basic mechanisms seem to apply to all isoforms and splice variants, that is, the synergistic interactions between CBD1 and CBD2 are manifested as increased affinity and slower Ca2+ dissociation kinetics at CBD125, 26. On the other hand, these interactions are clearly modified by alternative splicing to fulfill specific physiological needs in distinct cell types25, 26. In addition, distinct NCX variants exhibit different regulatory responses to Ca2+ and Na+-dependent regulation despite having high homology and predicted structural similarity6. For example, in NCX1, variants that are capable of Ca2+ binding at CBD2 exhibit Ca2+-dependent alleviation of Na+-induced inactivation, whereas in NCX3, NCX3-CBD12-AC, which does not bind Ca2+ at CBD2, exhibits less Na+-induced inactivation as compared with NCX3-CBD12-B11, 26. NCX2 differs from the rest NCX variants in that that it does not undergo alternative splicing and it does own to the Na+-induced inactivation. The results presented here, taken together with extensive previous studies of NCX1 splice variants6, 18, 19, 21, 25, 28, 29, 31, 32, may provide a conceptual framework to resolve a common mechanistic platform and disparities owned by distinct isoform-splice variants.

First and foremost, CBD1 and CBD2 act as Ca2+ sensors. Therefore, their binding affinity and kinetics must correlate with the dynamic properties of Ca2+ signaling in a given tissue1, 2. In this respect, the importance of alternative splicing is straightforward: NCX1 (NCX1-AD) and NCX3 (NCX3-B, NCX3-BC) splice variants expressed in the brain, as well as NCX2, exhibit faster Ca2+ dissociation kinetics from CBD12 compared with NCX1 and NCX3 splice variants expressed in muscles (NCX1-ACDEF in cardiac muscle and NCX3-AC in skeletal muscle)25, 26. This is in line with the prolonged Ca2+ transients and action potential durations in muscles compared with neurons4, 5, 26. These hallmark features, assigned to Ca2+ interactions with CBD1 and CBD2, strictly correlate with characteristic regulatory modes ascribed to matching (full-size) NCX variants4, 7, 9, 11, 13, 25, 26. The equilibrium and kinetic parameters measured in isolated NCX1-CBD12-ACDEF preparations25 were successfully applied to computer-aided dynamic modeling of allosteric activation of the cardiac NCX1 (ACDEF) during the action and resting potentials, thereby providing indispensable information on the dynamic contributions of NCX in handling the Ca2+-dependent Ca2+-release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, the Ca2+-spark appearance, and duration within local sub-cellular compartments and the fine-tuning of excitation-contraction coupling in cardiomyocytes35. Similar applications for computer-aided modeling are straightaway required for clarifying the partial contributions of multiple NCX isoforms and their splice variants to the dynamic handling of dynamic Ca2+ swings in neuronal tissues. The emerging working hypothesis is that specific conformational variances, raised by exons, diversify the affinity/off-rates of Ca2+ at CBD1 (for controlling the Ca2+-dependent allosteric activation) and the affinity/capacity of Ca2+ binding to CBD2 (for controlling the Ca2+-dependent alleviation of Na+-induced inactivation)25, 26.

In NCX1, both the brain (AD) and cardiac muscle (ACDEF) splice variants bind Ca2+ at CBD2, to alleviate Na+-induced inactivation. The ability to counteract Na+-induced inactivation is of major importance in excitable tissues where large Na+ fluxes (through the voltage-sensitive Na+-channels) occur at the initial stage of cell depolarization. NCX2 (expressed in the brain) lacks the Na+-induced inactivation, whereas in NCX3 the Na+-induced inactivation can be counteracted by increased levels of cytosolic Ca2+, but to varying degrees9, 11. It was previously proposed that an electrostatic switch at CBD2 underlies the alleviation of Na+-induced inactivation upon Ca2+ binding, but this proposal cannot account for the regulatory properties of NCX2 (where the Ca2+ binding affinity at CBD2 is extremely low) or for regulatory features of NCX3-AC9, 11, 21, 26. However, the data presented here may resolve the principal structural platform for the dynamic regulation of NCXs, as well as it can pinpoint the exon-governed fine shaping in the backbone dynamics that may account for regulatory diversity.

In recent years, a growing body of evidence has suggested an updated view of allosteric regulation in proteins. More specifically, a greater importance is given to changes in protein dynamics and conformational distributions rather than to global conformational transitions36, 37, 38–42. The accumulating evidence raises several important points. Protein rigidity seems to serve as a common communication route between distant sites in proteins, resulting in structural coupling between the regulatory regions (e.g., CBD12) and the effector site (e.g., the ion-transport domain)42. Moreover, in some instances, allosteric interactions are mediated only by dynamic changes, without having any gross effects on the protein conformation36, 38, 39. In other cases, the population shift mechanism describes a shift in the protein ensemble of conformations towards active states, where no obvious global conformational change is observed37. These observations were recently formulated into a unified model of allostery, based on thermodynamics, the structure, and the free energy landscape of the population shift41. According to this general model, the allosteric mechanism in a specific protein requires three elements41, allowing us to formulate a general scheme for NCX isoforms and regulation of splice variants.

First, the active conformation responsible for allosteric regulation is required41. This conformation is provided by the crystal structure of NCX1-CBD12-AD-E454K19, which also allows us to model NCX2-CBD12 and NCX3-CBD12 in the Ca2+-bound conformation. The molecular envelopes calculated here (Fig. 2) verify the relevance of these homology models to the global conformations of Ca2+-bound CBD12 isoforms. The EOM analyses performed previously for NCX1-CBD12 and performed here for NCX2-CBD12 and NCX3-CBD12 are in line with the unified model, whereby the allosteric event (Ca2+ binding) does not create any new conformational states but instead, only shifts the population among the existing states, towards more stable elongated conformations (Fig. 3)28.

Second, a set of interacting residues is required41. This set of residues is clearly depicted in the crystal structure of NCX1-CBD12-AD-E454K, where a network of hydrogen-bonded salt bridges and hydrophobic interactions between the α-helical region of CBD2 and F450 from NCX1 form the interdomain interface19. Notably, the two-domain interface is extremely well conserved among all isoform splice variants, so the use of a crystal structure of NCX1-CBD12-AD-E454K as a universal model is highly justified. According to this model, the mutations of interacting residues must uncouple the regulatory function of CBDs. This prediction has been experimentally demonstrated by showing a lack of Ca2+ occlusion and reduced binding affinity of Ca2+ in several mutations of residues contributing to the stabilization of the two-domain interface, including the interdomain linker (e.g., G503), the hydrophobic core (e.g., F450), and salt bridge elements (e.g., R532 or D565) tethering CBDs upon Ca2+ binding6, 19, 23–29. For example, the structural evidence revealed by HDX-MS demonstrates the reduced Ca2+-dependent CBD2 rigidification in the F450G mutant, thereby confirming the general model for Ca2+-dependent tethering of CBDs and the rigidification of the two-domain interface19, 29. Consistent with this statement, this residue is highly conserved among NCX orthologs19 and F472 in NCX2-CBD12 and F474 in NCX3-CBD12 (corresponding to F450 in NCX1-CBD12) show reduced deuterium uptake upon Ca2+ binding (Figs 4 and 5). Moreover, the accumulating HDX-MS data on NCX1-CBD12, NCX2-CBD12, and NCX3-CBD12 proteins depict the allosteric stabilization within CBD2 upon Ca2+ binding at CBD1 (Figs 4 and 5) through the population shift mechanism, shared by all tested isoform/splice variants6, 28, 29, 31. Thus, the CBD2 isoforms and splice variants dynamically shape the initial decoding of regulatory signal upon Ca2+ binding and thus, the signal message undergoes a transformation toward further propagation of allosteric signal. The underlying mechanisms of signal propagation from the CBDs to the target sites of ion-transport domains remain to be discovered.

Finally, one should consider whether ligand binding at the regulatory site stabilizes the active conformation, destabilizes the inactive conformation, or does both simultaneously43. This question is not fully resolved with NCX proteins because a structure of apo-CBD12 is lacking. However, EOM studies of NCX1-CBD12 splice variants show that the active conformations are also sampled in the absence of Ca2+, but with a lower frequency28. The Ca2+-bound crystal structure also demonstrates how the presence of Ca2+ “locks” the two domains in an elongated conformation19. Thus, the Ca2+-dependent stabilization of the one or more “active conformation states” can explain (at least partially) the mechanism by which the ligand binding modulates the activity of NCX proteins.

Having this general mechanism in mind, it can be concluded that different NCX isoforms and splice variants share a similar “active” conformation, which becomes highly populated upon Ca2+ binding (Figs 2 and 3)19, 28, 29. A very limited number of major “conformational state(s)” display some clear and highly conserved interdomain interactions between residues, although the complete dynamic response in CBD2 is different among distinct isoforms and splice variants29, 31. The present (Figs 3, 4 and 5) and previous HDX-MS analyses of the different CBD12 proteins29, 31 underscore a general concept according to which the rigidity and allosteric capacity strictly correlate42. Intriguingly, the disparate isoforms have different means to control the rigidity of CBD2. That is, in NCX1, alternative splicing using A-exon acts by allowing Ca2+ binding at CBD2, which in turn, increases the rigidity of CBD225, 29. In NCX3, the mere presence of exon A results in increased response to regulatory Ca2+ binding at CBD1 (Fig. 4). The concept described here is further supported from previous analyses of CBD12 splice variants from CALX, a Drosophila melanogaster NCX ortholog, which exhibits anomalous Ca2+-dependent regulation. In line with the general mechanism described here, Ca2+ binding to CBD1 in CALX1.1 does not rigidify CBD2 and indeed, the intact (full-size) CALX1.1 responds to the regulatory Ca2+ binding in a negative mode, thereby exhibiting inhibition rather than activation29.

Comparison of HDX-MS profiles of NCX2-CBD12, NCX3-CBD12-AC, and NCX3-CBD12-B (Figs 4, 5 and S2) revealed that in NCX3, the B and AC exons differentially stabilize CBD1 folding in the apo state; thus NCX3-CBD12-B is less dynamic than is NCX3-CBD12-AC. However, these differences are not prominent in the Ca2+-bound states, meaning that Ca2+ binding results in greater rigidification of NCX3-CBD12-AC and therefore the apo form predefines the incremental effect of Ca2+ binding. The greater dynamic effect may explain the reduced Na+-dependent inactivation. Similarly, in NCX1-CBD12 proteins, A-exon-containing variants in which Ca2+ can alleviate Na+-dependent inactivation exhibit greater rigidification of CBD2 (aided by Ca2+-binding). Therefore, the observed deviations in the conformational dynamics of the NCX1 and NCX3 splice variants (Fig. 4) adequately match the CBD2-controlled regulatory variances observed in full-size NCX1 and NCX3 splice variants29, 31. Although NCX2-CBD12 cannot be directly compared to NCX1-CBD12 and NCX3-CBD12, it also undergoes significant rigidification upon Ca2+ binding (Fig. 4).

In general, the Ca2+-bound forms of all the tested variants of NCX2-CBD12 and NCX3-CBD12 exhibit more rigid backbone dynamics in comparison with the respective apo-forms (Fig. 5). The Ca2+-dependent effects are especially remarkable at the α-helical region of CBD2, which from one side is in proximity with the high-affinity sensor of CBD1 (at the two-domain interface) and on the other side, neighbors the splicing segment at CBD2 (Fig. 1). This mode of Ca2+-dependent conformational modulation is consistent with rigidification of the two-domain interface upon Ca2+-binding to CBD1, where the tethering of CBDs (through the formation of an interdomain salt-bridge network) stabilizes Ca2+ occlusion at high-affinity sites of CBD1, thereby allowing a further transformation and propagation of the allosteric signal. Similar conclusions were drawn for Ca2+-dependent rigidification of the α-helix in NCX1-CBD12 variants29. Therefore, accumulating evidence strongly supports a general mechanism for the examined NCX1, NCX2, and NCX3 variants, according to which Ca2+-binding stabilizes the interdomain linker, the hydrophobic interface between the CBDs, and the nearby α-helix/FG-loop segment on CBD2 next to the splicing segment9, 25, 28, 29, 31. It is quite obvious that the Ca2+-dependent rigidification of the two-domain interface detected by HDX-MS and SAXS techniques is coupled with the Ca2+ occlusion and two-domain tethering of CBDs, which further stabilizes the active conformation in all tested isoform/splice variants of CBD12 proteins19, 23, 25–32, 44. The experimental methods described here may be used in future studies to resolve the role of alternative splicing in shaping the allosteric regulation of many protein families.

Methods

Overexpression and purification of CBD proteins

The DNA constructs of rat NCX2-CBD12, NCX3-CBD12-AC, and NCX3-CBD12-B were cloned into the pET28a vector, confirmed by sequencing and expressed in E. coli Rosetta2 (DE3) competent cells (Novagen) as described26. Overexpressed proteins were purified on a TALON-superflow (GE healthcare) column followed by size exclusion chromatography on FPLC by using a Superdex 200 column (GE healthcare)26. The purity of the finally purified protein preparations was >95%, as judged by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were concentrated, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until their usage for SAXS or HDX-MS experiments.

Homology modeling of NCX-CBD12 isoforms

The models of NCX2-CBD12, NCX3-CBD12-AC, and NCX3-CBD12-B were generated based on the crystal structure of NCX1-CBD12-E454K (PDB 3US9)19. MODELLER was used to generate the models45.

SAXS Data Collection and Analysis

SAXS data were measured at the beamline BM29 of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF), Grenoble, France. Data were collected at 4 °C with the X-ray beam at wavelength λ = 1.0 Å, and the distance from the sample to detector (PILATUS 1 M, Dectris Ltd) was 2.867 meters, covering a scattering vector range (q = 4πsinθ/λ) from 0.0025 to 0.5 Å−1. Ten frames of two-dimensional images were recorded for each buffer or sample, with an exposure time of 2 sec per frame. The 2D images were reduced to one-dimensional scattering profiles and the scattering of the buffer was subtracted from the sample profile using the software at the site. The buffers contained 100 mM KCl, 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.2, and either 10 mM CaCl2 or 10 mM EDTA. To account for possible inter-particle effects, each sample was measured at four concentrations: ~10, ~5, ~2.5, and ~1.5 mg/mL. In the presence of such effects, the lowest concentration curve was merged with a higher concentration curve at q ~ 0.2 Å−1 to prevent distortion of the low-angle data while preserving a high signal-to-noise ratio at the higher angles, which are far less sensitive to interparticle effects33. The experimental radius of gyration (R g) was calculated from data at low q values in the range of qR g < 1.3, according to the Guinier approximation: lnI(q) ≈ ln(I(0)) − R g 2 q 2/3 using PRIMUS46. The Dmax values and the Porod volume were derived from the paired-distance distribution function (PDDF or P(r)) calculated using GNOM47. Ab initio shape reconstructions were performed with the ATSAS software suite, using scattering data of the q range between 0.02 and 0.30 Å−1 47.

Ensemble optimization method (EOM) analysis

NCX2-CBD12, NCX3-CBD12-AC, and NCX3-CBD12-B were modelled with MODELLER45, based on the crystal structure of NCX1-CBD12-E454K (PDB 3US9)19. Unstructured residues at the N- and C-termini of CBD1 and CBD2 and the large flexible FG-loop of CBD2 were truncated. The software RANCH48 was used to generate a pool of 10,000 stereochemically feasible structures with a random CBD1-CBD2 linker, N- and C-termini, and a CBD2 FG-loop. These pools were used as input for GAJOE48, which selects an ensemble with the best fit to the experimental data using a genetic algorithm: 50 ensembles of 20 orientations each were “crossed” and “mutated” for 1,000 generations and the process was repeated 50 times.

Deuterium exchange for HDX-MS experiments

Purified proteins were prepared at a concentration of 100 µM in a buffer composed of 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 100 mM KCl, 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol either with 1.42 mM EDTA or 10 mM CaCl2. The HDX reaction was initiated by mixing 2ul of protein samples with 28 µL of D2O buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pD 7.2, 100 mM KCl, 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol) containing 1.42 mM EDTA, or 10 mM CaCl2 for 10 sec, 100 sec, 1,000 sec, or 10,000 sec at 4 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding 30 µl of ice-cold quench buffer (0.1 M NaH2PO4, 1 M guanidine, 20 mM TCEP, pH 2.01). For non-deuterated (ND) samples, 2 µl of protein samples were mixed with 28 µl of H2O buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 100 mM KCl, 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol), and 30 µl of ice-cold quench buffer was added.

Mass spectrometry, peptide identification, and HDX-MS data processing

The quenched samples were digested and analyzed by the HDX-UPLC-ESI-MS system (Waters) as previously described29. Mass-spectral analyses were performed with a Xevo G2 Quadruple-time of fly (Q-TOF) equipped with a standard electrospray ionization (ESI) source in MSE mode in positive ion mode. All setting conditions for the system were reported previously49. Identification and HDX-MS data processing of peptic peptides were performed by ProteinLynx Global Server 2.4 (Waters) and DynamX 2.0 (Waters) as previously described31. All of the data were derived from at least three independent experiments, and the statistical significance was analyzed by t-test.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation Grant #825/14 to D.K. and the National Research Foundation of Korea, Grant [NRF-2012R1A5A2A28671860 and NRF-2015R1A1A1A05027473] to K.Y.C. The financial support of the Fields Estate foundation to D.K. is highly appreciated. This work was performed by Y.A., R.G., and Y.T. in fulfillment of the M.D. thesis requirements of the Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University.

Author Contributions

M.G., K.Y.C., and D.K. designed the experiments. M.G., S.Y.L., Y.A., R.G., Y.T., R.S., and Y.H. conducted the experiments. M.G., S.Y.L., K.Y.C., and D.K. analyzed the data and prepared the figures. M.G., K.Y.C., and D.K. wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Moshe Giladi and Su Youn Lee contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01102-x

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ka Young Chung, Email: kychung2@skku.edu.

Daniel Khananshvili, Email: dhanan@post.tau.ac.il.

References

- 1.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCue HV, Haynes LP, Burgoyne RD. The diversity of calcium sensor proteins in the regulation of neuronal function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a004085. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khananshvili D. Sodium-calcium exchangers (NCX): molecular hallmarks underlying the tissue-specific and systemic functions. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:43–60. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1405-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaustein MP, Lederer WJ. Sodium/calcium exchange: its physiological implications. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:763–854. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giladi M, Tal I, Khananshvili D. Structural features of ion transport and allosteric regulation in sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX) proteins. Front Physiol. 2016;7:30. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyck C, et al. Ionic regulatory properties of brain and kidney splice variants of the NCX1 Na(+)-Ca(2+) exchanger. J Gen Physiol. 1999;114:701–711. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.5.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kofuji P, Lederer WJ, Schulze DH. Mutually exclusive and cassette exons underlie alternatively spliced isoforms of the Na/Ca exchanger. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5145–5149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linck B, et al. Functional comparison of the three isoforms of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX1, NCX2, NCX3) Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C415–423. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.2.C415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quednau BD, Nicoll DA, Philipson KD. Tissue specificity and alternative splicing of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger isoforms NCX1, NCX2, and NCX3 in rat. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C1250–1261. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.4.C1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michel LY, et al. Function and regulation of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger NCX3 splice variants in brain and skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:11293–11303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.529388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ottolia M, Nicoll DA, Philipson KD. Roles of two Ca2+-binding domains in regulation of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32735–32741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.055434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michel LY, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Towards understanding the role of the Na(2)(+)-Ca(2)(+) Exchanger Isoform 3. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;168:31–57. doi: 10.1007/112_2015_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khananshvili D. Distinction between the two basic mechanisms of cation transport in the cardiac Na(+)-Ca2+ exchange system. Biochemistry. 1990;29:2437–2442. doi: 10.1021/bi00462a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liao J, et al. Structural insight into the ion-exchange mechanism of the sodium/calcium exchanger. Science. 2012;335:686–690. doi: 10.1126/science.1215759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marinelli F, et al. Sodium recognition by the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in the outward-facing conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E5354–5362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415751111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren X, Philipson KD. The topology of the cardiac Na(+)/Ca(2)(+) exchanger, NCX1. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;57:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hilge M, Aelen J, Vuister GW. Ca2+ regulation in the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger involves two markedly different Ca2+ sensors. Mol Cell. 2006;22:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giladi M, et al. A common Ca2+-driven interdomain module governs eukaryotic NCX regulation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Besserer GM, et al. The second Ca2+-binding domain of the Na+ Ca2+ exchanger is essential for regulation: crystal structures and mutational analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18467–18472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707417104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilge M, Aelen J, Foarce A, Perrakis A, Vuister GW. Ca2+ regulation in the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger features a dual electrostatic switch mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14333–14338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902171106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilgemann DW, Matsuoka S, Nagel GA, Collins A. Steady-state and dynamic properties of cardiac sodium-calcium exchange. Sodium-dependent inactivation. J Gen Physiol. 1992;100:905–932. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.6.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyman L, Mikhasenko H, Hiller R, Khananshvili D. Kinetic and equilibrium properties of regulatory calcium sensors of NCX1 protein. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6185–6193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicoll DA, et al. The crystal structure of the primary Ca2+ sensor of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger reveals a novel Ca2+ binding motif. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21577–21581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giladi M, et al. Dynamic features of allosteric Ca2+ sensor in tissue-specific NCX variants. Cell Calcium. 2012;51:478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tal I, Kozlovsky T, Brisker D, Giladi M, Khananshvili D. Kinetic and equilibrium properties of regulatory Ca(2+)-binding domains in sodium-calcium exchangers 2 and 3. Cell Calcium. 2016;59:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giladi M, Boyman L, Mikhasenko H, Hiller R, Khananshvili D. Essential role of the CBD1-CBD2 linker in slow dissociation of Ca2+ from the regulatory two-domain tandem of NCX1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28117–28125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.127001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giladi M, Hiller R, Hirsch JA, Khananshvili D. Population shift underlies Ca2+-induced regulatory transitions in the sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX) J Biol Chem. 2013;288:23141–23149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.471698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giladi M, Lee SY, Hiller R, Chung KY, Khananshvili D. Structure-dynamic determinants governing a mode of regulatory response and propagation of allosteric signal in splice variants of Na+/Ca2+ exchange (NCX) proteins. Biochem J. 2015;465:489–501. doi: 10.1042/BJ20141036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.John SA, Ribalet B, Weiss JN, Philipson KD, Ottolia M. Ca2+-dependent structural rearrangements within Na+-Ca2+ exchanger dimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1699–1704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016114108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SY, et al. Structure-dynamic basis of splicing-dependent regulation in tissue-specific variants of the sodium-calcium exchanger. FASEB J. 2016;30:1356–1366. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-282251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salinas RK, Bruschweiler-Li L, Johnson E, Bruschweiler R. Ca2+ binding alters the interdomain flexibility between the two cytoplasmic calcium-binding domains in the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32123–32131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.249268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koch MH, Vachette P, Svergun DI. Small-angle scattering: a view on the properties, structures and structural changes of biological macromolecules in solution. Q Rev Biophys. 2003;36:147–227. doi: 10.1017/S0033583503003871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sisalli MJ, Annunziato L, Scorziello A. Novel cellular mechanisms for Neuroprotection in Ischemic Preconditioning: A View from inside organelles. Front Neurol. 2015;6:115. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chu L, Greenstein JL, Winslow RL. Modeling Na+-Ca2+ exchange in the heart: Allosteric activation, spatial localization, sparks and excitation-contraction coupling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;99:174–187. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Popovych N, Sun S, Ebright RH, Kalodimos CG. Dynamically driven protein allostery. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:831–838. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laskowski RA, Gerick F, Thornton JM. The structural basis of allosteric regulation in proteins. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1692–1698. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kern D, Zuiderweg ER. The role of dynamics in allosteric regulation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:748–757. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tzeng SR, Kalodimos CG. Dynamic activation of an allosteric regulatory protein. Nature. 2009;462:368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature08560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodey NM, Benkovic SJ. Allosteric regulation and catalysis emerge via a common route. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:474–482. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsai CJ, Nussinov R. A unified view of “how allostery works”. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rader AJ, Brown SM. Correlating allostery with rigidity. Mol Biosyst. 2011;7:464–471. doi: 10.1039/C0MB00054J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nussinov R, Tsai CJ. Allostery in disease and in drug discovery. Cell. 2013;153:293–305. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Giladi M, Friedberg I, Fang X, Hiller R, Wang YX, Khananshvili D. G503 is obligatory for coupling of regulatory domains in NCX proteins. Biochemistry. 2012;51:7313–7320. doi: 10.1021/bi300739z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eswar N, Eramian D, Webb B, Shen MY, Sali A. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;426:145–159. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Konarev PV, Volkov VV, Sokolova AV, Koch MHJ, Svergun DI. PRIMUS: a Windows PC-based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. J Appl Crystallogr. 2003;36:1277–1282. doi: 10.1107/S0021889803012779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Svergun DI. Determination of the regularization parameter in indirect-transform methods using perceptual criteria. J Appl Crystallogr. 1992;25:495–503. doi: 10.1107/S0021889892001663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tria G, Mertens HD, Kachala M, Svergun DI. Advanced ensemble modelling of flexible macromolecules using X-ray solution scattering. IUCrJ. 2015;2:207–217. doi: 10.1107/S205225251500202X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim DK, Yun Y, Kim HR, Seo MD, Chung KY. Different conformational dynamics of various active states of beta-arrestin1 analyzed by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. J Struct Biol. 2015;190:250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.