Abstract

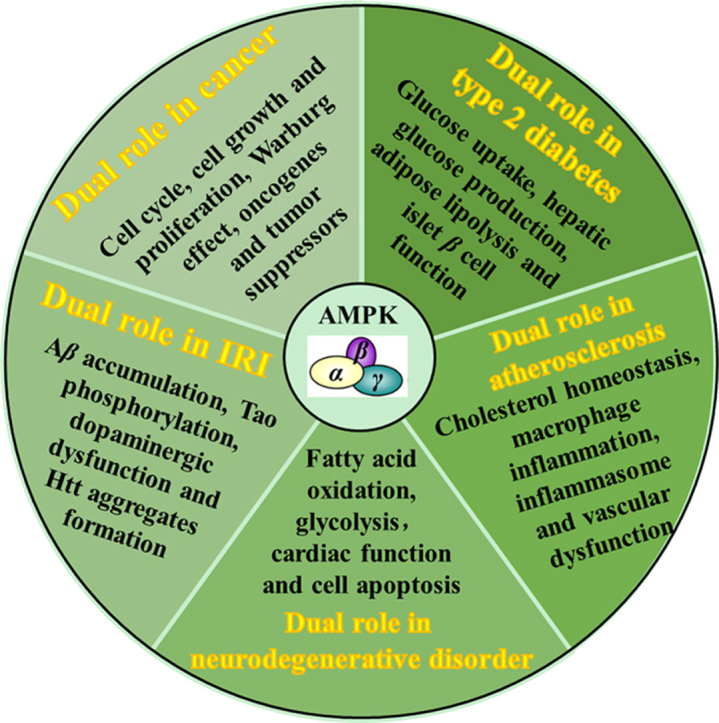

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), known as a sensor and a master of cellular energy balance, integrates various regulatory signals including anabolic and catabolic metabolic processes. Accompanying the application of genetic methods and a plethora of AMPK agonists, rapid progress has identified AMPK as an attractive therapeutic target for several human diseases, such as cancer, type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and neurodegenerative disease. The role of AMPK in metabolic and energetic modulation both at the intracellular and whole body levels has been reviewed elsewhere. In the present review, we summarize and update the paradoxical role of AMPK implicated in the diseases mentioned above and put forward the challenge encountered. Thus it will be expected to provide important clues for exploring rational methods of intervention in human diseases.

KEY WORDS: AMPK, Cancer, Type 2 diabetes, Atherosclerosis, Myocardial ischemia, Neurodegenerative disease

Graphical abstract

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) has been identified as an attractive therapeutic target for cancer, type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and neurodegenerative disease. This review summarizes and updates the paradoxical role of AMPK implicated in these human diseases and put forward the challenge encountered.

1. Introduction

Since 1973, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) has been first known as an inhibitory factor of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR) and acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase (ACC) in the presence of ATP. The responsible agents were later shown to be kinases and subsequently named as HMGCR kinase and ACC kinase 3, respectively1, 2. With the progress of successful purification of this kinase, it was not until 1989 when the name AMPK was finally adopted as it can be allosterically regulated by AMP3. Besides key regulatory enzymes controlling sterol and fatty acid synthesis, two other enzymes that catalyze important steps in lipolysis and glycogen synthesis (hormone-sensitive triglyceride lipase and glycogen synthase) were subsequently reported as substrates for AMPK4, 5. The physiological role of AMPK gradually surfaced. In the meantime, the recognition of nucleotides, AMP, ADP and ATP, as allosteric regulators of AMPK activity deepened the understanding of the physiological significance of AMPK3. The current view is that AMPK, the cellular energy sensor, is activated following cellular stress like hypoxia, starvation, glucose deprivation or muscle contraction which can increase the ratio of ADP:ATP or AMP:ATP. In order to restore cellular energy balance, the highly active enzyme integrates hormonal and nutrients signals which will promote catabolism (fatty acid oxidation and glycolysis) and inhibit anabolism (fatty acid, cholesterol, triglycerides and protein, etc.). Apart from these canonical functions, AMPK is confirmed to be involved in cell growth, development, longevity and cell polarity6. Additional AMPK activating factors include liver kinase B1 (LKB1), calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase β (CaMKKβ) and transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase (TAK-1). LKB1 has been proposed to phosphorylate AMPK when the ratio of AMP:ATP is upregulated. However, AMPK can still be excited by CaMKKβ during intracellular Ca2+ release or by TAK-1 in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines or apoptosis-inducing agent, even when no change in nucleotides are detected7, 8, 9, 10. The detailed information regarding structure, activity regulation and pharmacological agonists of AMPK have recently been reviewed11. In this article, we will focus on the association between AMPK and a variety of human diseases, including cancer, type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and neurodegenerative disorder.

2. The role of AMPK in human diseases

2.1. AMPK in cancer

Cancer is fundamentally a disease of tissue growth regulation failure, which can be driven by dysregulation of several cell cycle components. Apart from these alterations, increased catabolic glucose metabolism was observed in proliferating cells. It is a necessity for tumor cells to overcome the significant energy challenge in the initiation of uncontrolled proliferation; otherwise, they die due to energy deficiency. In the mid-1950s, Warburg12 discovered that tumor cells still survive in the absence of oxygen by glycolysis, and later it was referred as “Warburg effect”. The metabolic switch towards the Warburg effect not only supplies the biogenetic source but also confers important metabolic intermediates for cell growth13. Presently, this peculiar metabolic shift is universally recognized as a hallmark for tumor cells. Progress in identification of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes makes the targeting of this metabolic switch a viable new approach for cancer treatments.

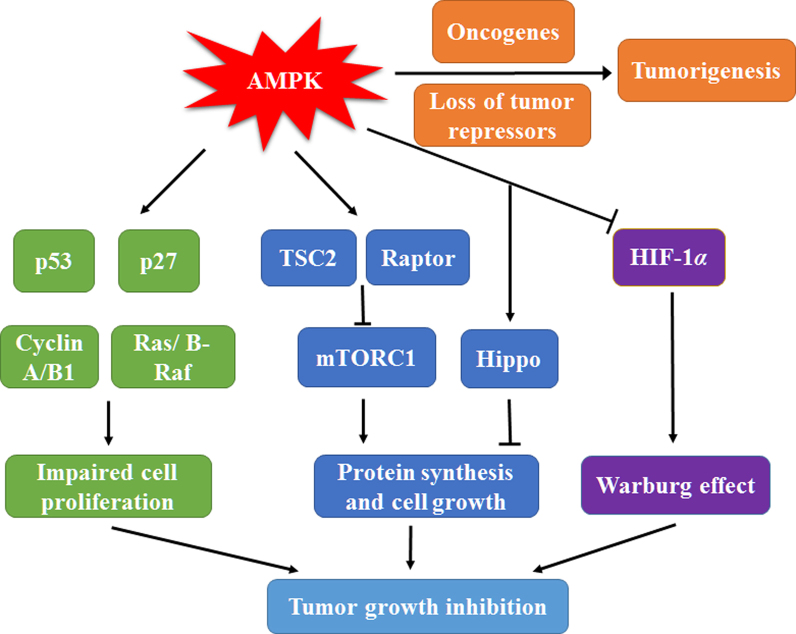

It has been proposed that AMPK is closely related to the regulation of the cell cycle because AMPK activation stimulates phosphorylation and activation of tumor suppressor p53, stabilization of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 and reduction of key cell cycle regulators like cyclin A and cyclin B114, 15, 16. Oncogenic BRAF repressing LKB1 and AMPK activity accelerates melanoma cell proliferation17. On the other hand, AMPK activation blocks the progression of keratinocyte cell cycle via phosphorylation of B-Raf18. A recent study revealed that CAMKKβ-induced AMPK activation also induces cell cycle arrest19. Apart from the regulatory effect on cell cycle checkpoints, AMPK suppresses the anabolic processes required for rapid cell growth. These processes include mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)-dependent protein biosynthesis induced by direct phosphorylation of the tumor suppressor TSC2 and the regulatory-associated protein raptor20, and de novo biosynthesis of fatty acid and cholesterol caused by inactivating ACC1, HMGCR and lipogenic transcription factors sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs)21, 22. More recent genetic researches showed that the growth-suppressive action of AMPK may be mediated by the Hippo pathway23, 24, 25. Furthermore, Faubert et al.26, 27 provided evidence to demonstrate that AMPK is a negative controller of the Warburg effect using models with genetic deletion of either LKB1 or AMPKα1. AMPK activation promotes mitochondrial biosynthesis and expression of oxidative enzymes and thus attenuates the glycolytic pathway by inhibiting the transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α). Genetic ablation of AMPKα1 accelerates Myc-induced lymphomagenesis, suggesting that the absence of AMPK may enhance oncogene activity to boost tumorigenesis26. Thus, AMPK can be classified as a metabolic tumor suppressor (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) plays a double-edged role in cancer. AMPK stimulation promotes activation of tumor repressor p53, increases cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27, decreases cyclin A and cyclin B1, and suppresses ras and B-raf signaling pathway, resulting in cell cycle arrest and impaired cell proliferation. AMPK can induce phosphorylation of TSC2 and raptor to suppress mTOCR1 dependent protein synthesis and activate Hippo pathway to inhibit cell growth. The reduced HIF-1α transcription activity mediated by AMPK activation leads to the block of Warburg effect and the decreased energy supply, contributing to inhibition of tumor cell growth in further. Thus, AMPK may exert its anticancer activities through multiple approaches mentioned above. However, AMPK may also cooperate with either oncogenes or loss of tumor repressors to promote tumorigenesis.

However, several groups have recently reported that diverse variety of tumor repressors or proto-oncogenes negatively regulate AMPK activity. The absence of the tumor repressor gene folliculin (FLCN) in association with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome (BHD) confers tumorigenesis through activation of AMPK28, 29. Likewise, AMPK stimulation was found to be indispensable for the proliferation of astrocytic tumor cells or the growth of experimental human breast cancer tumor30, 31. Besides, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), a melanoma oncoprotein, is regulated by AMPK to maintain cell viability32. The requirement of AMPK for prostate cancer progression and colon tumor cell survival has also been recently reported33, 34. It seems that there are two faces of AMPK in tumorigenesis. In established solid tumors, AMPK activation can provide metabolic adaptive responses to maintain energy supply, although inhibition of AMPK is beneficial in earlier phases of tumor growth. It is worth noting that AMPKα2 has been reported to selectively suppress Ras-induced mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) transformation and reduce the growth of human mammary epithelial cells (HMECs)35, 36. However, two more recent reviews have pointed out that the PRKAA1 gene encoding α1 is often amplified whereas the PRKAA2 gene encoding α2 is more frequently mutated in human cancers37, 38. Thus, the two catalytic subunit isoforms may play divergent roles in cancer.

In consideration of the aforementioned role of AMPK in tumorigenesis, pharmacological activation of AMPK may exert beneficial effects on cancer. Indeed, pharmacological activation of AMPK by biguanides or A769662 to Pten+/− mice remarkably inhibits tumorigenesis39. Subsequently, numerous studies have obtained similar results showing that AMPK agonists can inhibit cancer cell growth and proliferation40, 41, 42. In clinic, a significant reduction in the incidence of cancers in subjects taking metformin compared with other antidiabetic drugs was found by meta-analysis43. However, several groups have recently challenged the role of AMPK in the protective effect of these compounds on tumorigenesis. They pointed out that A769662, widely acknowledged as direct AMPK agonist, may actually accelerate tumor cell proliferation in response to metabolic stress. Additionally, those indirect AMPK agonists prevent tumor cell proliferation and mTOR activity in an AMPK-independent manner44, 45, 46. Biguanides, a group of classic anti-diabetic drugs, was later recognized as potential anti-cancer agents. In fact, they are inhibitors of the mitochondrial respiratory chain and have recently been found to preferentially kill various cancer stem cells, which are dependent on mitochondrial metabolism47, 48. In the context of inhibition of proliferation, the upregulation of AMPK activity occurs as an adaptive response to protect cells from the toxicity of biguanides since the mortality increases in cells without LKB1, a critical upstream kinase of AMPK and once known as a tumor repressor49. Further, in the mouse model of colon carcinoma or non-small cell lung cancer with a defective LKB1/AMPK pathway, the rate of tumor growth declines following treatment with biguanides50, 51. Thus, it would be promising to combine biguanides with AMPK inhibitors in the treatment of established solid tumors.

2.2. AMPK in type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes (formerly named noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus or adult-onset diabetes) is a metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia and abnormal lipid metabolism in the context of decreased insulin sensitivity of peripheral tissue and inadequate insulin secretion by islet beta cells. It has been agreed that overnutrition, inactivity and consequential obesity are the primary cause of type 2 diabetes in genetically predisposed individuals. Regular exercise and proper dietary are thought to be first steps to manage the disease. The beneficial effects of exercise may be at least partly mediated by AMPK activation, consistent with a critical role of AMPK in regulating glucose metabolism52.

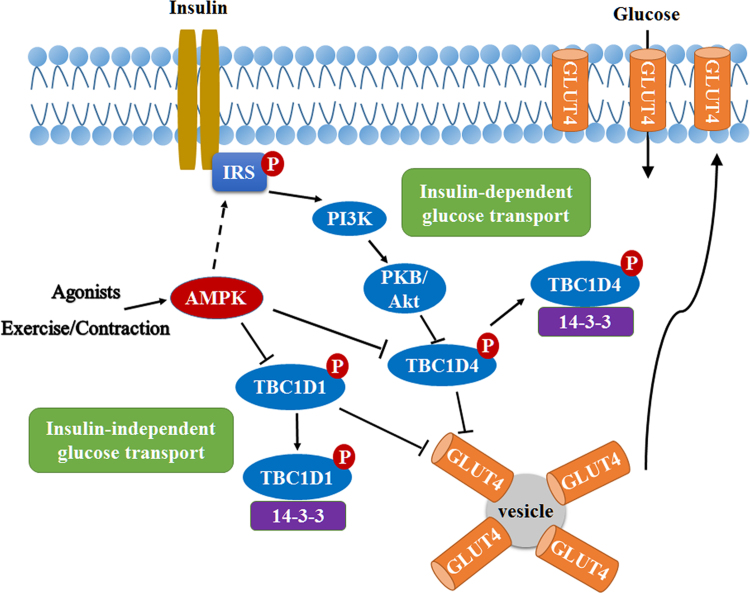

The above mentioned insulin-insensitive peripheral tissues mainly consist of skeletal muscle, liver and fat. Among them, skeletal muscle constitutes around 80% of insulin-stimulated glucose disposal53. It has been reported that AMPK activation by chronic administration of metformin enhances insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in mouse soleus muscle54. One explanation may be that AMPK activation enhances insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) Ser789 phosphorylation and subsequent phosphoinositide 3 kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/PKB) signaling pathway55, 56. However, in vivo evidence to support this is lacking, since either AMPKβ1β2 muscle knockout mice or mice overexpressing AMPKα2 kinase-dead (KD) in muscle have normal insulin-stimulated glucose transport57, 58. The relationship between AMPK and insulin-independent stimulation of glucose uptake has attracted significant interest. AMPK agonists can stimulate glucose uptake in resting skeletal muscle, and genetic techniques confirmed that these effects are indeed mediated by AMPK59, 60, 61. Moreover, it has also been found that AMPKα2β2γ3 heterotrimer is mainly activated in skeletal muscle52. Although there are significant contradictory reports regarding the role of AMPK in exercise-induced glucose transport, results in muscle-specific AMPKβ1/AMPKβ2 double knockout mice have argued convincingly that AMPK is implicated in glucose transport in response to exercise or muscle contraction57. When AMPK is activated by exercise or contraction, both Rab GTPase-activating protein TBC1D4 (also known as AS160) and TBC1D1 are phosphorylated and inactivated. Nevertheless, TBC1D1 plays a more pivotal role. The phosphorylated form can recruit scaffolding protein 14-3-3 and allow GLUT4 storage vesicles transport to plasma membrane62, 63 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Regulation of glucose uptake in muscle by AMPK. AMPK activation by exercise or muscle contraction or agonists can phosphorylate Rab GTPases TBC1D4 and TBC1D1, increase 14-3-3 binding and subsequent dissociation from GLUT4, which promotes glucose uptake through increasing translocation of GLUT4 to plasma membranes. On the other hand, the insulin-mediated glucose uptake includes insulin receptor and insulin receptor substrate phosphorylation, PI3K/Akt activation and then phosphorylation of TBC1D4. AMPK may participate in the phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 in vitro but there is few in vivo evidence to support this.

Apart from impaired glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, the excessive release of glucose into the circulation by liver is another contributor to hyperglycemia. Dysregulated hepatic glucose production is mainly caused by abnormal gluconeogenesis and elevated plasma glucagon levels. Metformin, a widely used anti-diabetic agent, was first found to inhibit gluconeogenesis through the signaling pathway of LKB164. However, whether AMPK plays a key role in the reduction of hepatic glucose output by biguanides is quite controversial. Foretz et al.65 showed that metformin suppresses gluconeogenesis via a decrease in hepatic energy state independent of LKB1/AMPK pathway by genetic loss-of-function experiments. Subsequently, other groups also found that the inhibition of glucose output by metformin is attributed to the reduced hepatic glucagon signaling and declining mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase activity66, 67. Conversely, Fullerton et al.68 reported that metformin-induced AMPK activation and ACC phosphorylation play crucial roles in lipid-induced insulin resistance. It seems that the acute effect of metformin on hepatic glucose output may be AMPK-independent, whereas the longer-term effects (which are probably more relevant to therapy of humans with metformin) are AMPK-dependent. Subsequently, Cao et al.69 suggested that a low concentration of metformin inhibited gluconeogenic gene expression via AMPK without increasing the AMP/ATP ratio in primary hepatocytes. Furthermore, the increase in the net phosphorylation of AMPK Thr172 is caused by metformin-mediated increment in formation of the AMPK complex70. More recently, a small-molecule AMPK activator 991 was demonstrated to antagonize hepatic glucagon signaling via AMPK-induced cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 4B (PDE4B) activation71.

Adipose tissue is the main resource for plasma free fatty acids (FFAs) and abundant FFA accumulation in skeletal muscle, liver and adipocytes can drive insulin resistance via diacylglycerol (DAG) accumulation and protein kinase C (PKC) activation72, 73. AMPK activation in adipocytes inhibits lipogenesis due to increased phosphorylation of ACC and decreased expression of lipogenic genes including stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1), fatty acid synthase (FAS) and ACC1, which are under control of transcription factor SREBP-1c74, 75. On the other hand, the inactivation of ACC contributes to decreased malonyl-CoA and thus the attenuated inhibition of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1), a critical enzyme for fatty acid oxidation in mitochondria. Although acute treatment of AICAR in adipocytes was found to attenuate fatty acid oxidation, which is associated with reduced fatty acid uptake76, chronic activation of AMPK-stimulated fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial biogenesis74, 77. The role of AMPK in lipolysis is paradoxical. Exercise was reported to promote lipolysis in an AMPK-dependent fashion stimulated by adrenaline in adipocytes78. The pro-lipolytic action of AMPK was suggested to be closely associated with increased ATGL phosphorylation79. In contrast, mice deficient in AMPKα1 revealed a phenotype of smaller adipocytes with increased lipolysis. The anti-lipolytic effect of AMPK was demonstrated to act on hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) by blocking its translocation to the lipid droplet80. It seems that acute activation of AMPK suppresses adipose lipolysis and thereby decreasing serum fatty acid concentration, whereas prolonged activation promotes lipolysis74. A recent study demonstrated that nicotine acts on adipose tissue to accelerate lipolysis and induce insulin resistance through activating AMPKα281. However, the overall impact of AMPK on lipolysis still remains controversial.

The fourth contributor to Type 2 diabetes is the decline in numbers of normally functioning islet β cells, which is concurrent with dysregulated glucose-induced insulin secretion. Granot and other groups82, 83 first showed that genetic deletion of LKB1 in pancreatic beta cells dramatically increased insulin secretion in response to glucose and improved glucose tolerance; dramatic changes in β cell mass and polarity were also seen in vivo. Subsequently, two groups independently reported that LKB1 and AMPK may play different roles in the control of insulin secretion from islet β cells84, 85. In these studies, AMPK deficiency both in pancreatic β cell and hypothalamic neurons displayed defective insulin secretion and glucose-intolerance. Recently, Kone and his colleagues86 reconfirmed the above results through developing new models without AMPK deletion in the brain. One possible mechanism involves promotion of AMPK-dependent KATP channel trafficking, alleviation of endoplasmic reticulum stress and reduction of lipid accumulation via autophagy stimulation87, 88, 89. Thus, AMPK activation seems to have beneficial effect on islet β cells. Indeed, administration of AICAR protects against glucolipotoxicity-induced impaired β-cell function90. However, mice with the Arg299Gln γ2-specific mutation develop dysregulated β-cell function and obesity due to sustained activation of AMPK throughout all tissues91.

Any AMPK activator that crosses the blood–brain barrier would be likely to have adverse effects on food intake because hypothalamic AMPK plays a critical role in the regulation of feeding behavior. This process is suggested closely associated with the expression of orexigenic neuropeptide Y (NPY)/agouti-related protein (AgRP) and anorexigenic proopiomelanocortin-α (POMC)92. Either pharmacological activation or expressing constitutively active AMPK in hypothalamus increased food intake, whereas expressing dominant-negative (DN) AMPK in hypothalamus decreased the expression of NPY and AgRP93, 94. Claret et al.95 reported that mice with AMPKα2 deletion in proopiomelanocortin (POMC)-expressing neurons develop obesity due to increased food intake and decreased energy expenditure. On the contrary, mice with AMPKα2 defective in agouti-related protein (AgRP)-expressing neurons maintain their lean phenotype, suggesting there is a close relationship between AMPK and the activation of these neurons. A recent study pointed out that hypothalamic AMPK regulates neuropeptide expression through induction of autophagy96.

2.3. AMPK in atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a slow, progressive disease with accumulated cholesterol, triglyceride, immune cells and fibrin in the intima of coronary and larger arteries, which constitutes plaque. The plaque may gradually plug these arteries causing many other cardiovascular diseases including myocardial infarction and stroke. Solid evidence implicates AMPK in atherosclerosis through modulation of macrophage cholesterol homeostasis, inflammation and vascular dysfunction.

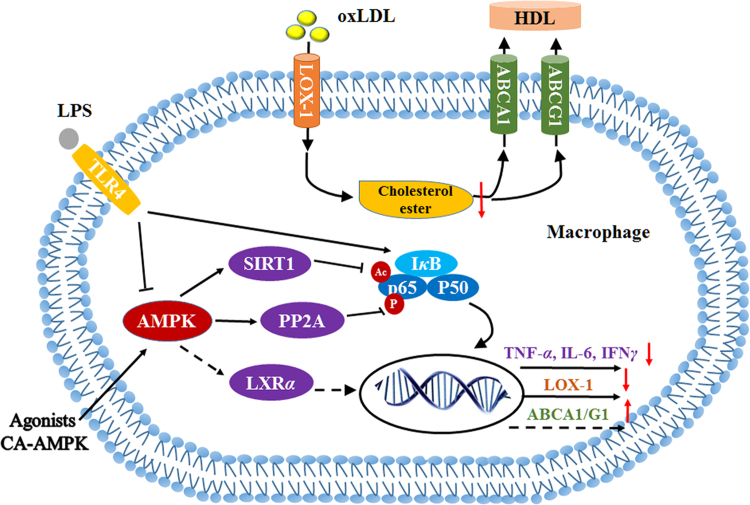

Imbalance of macrophage cholesterol homeostasis is of great importance to atherosclerotic progression. This is mostly because plaque formation requires monocyte infiltration, resulting in generation of vast proinflammatory factors and chemokines, and further development into atherogenic foam cells caused by excessive uptake of modified low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles. AMPK has been shown to prevent cholesterol accumulation in macrophages through promoting cholesterol efflux to high-density lipoprotein (HDL), causing a marked decrease in atherosclerotic plaque in ApoE–/– mice97, 98. The beneficial effect of AMPK may be related to the upregulation of ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 1 (ABCG1) and ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) gene expression accompanying with increased liver X receptor α (LXRα) expression (Fig. 3). Recently, our results also found out that AMPK predominates in macrophage uptake of cholesterol mediated by oxidized LDL (oxLDL) through downregulation of lectin like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (LOX-1) expression99. Similar results were obtained by several other groups with AICAR or berberine100, 101. The underlying mechanism is probably the decreased Ser536 phosphorylation of nuclear transcription factor NF-κB p65 induced by enhanced protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) activity99 (Fig. 3). The PP2A B56γ subunit can be directly phosphorylated at Ser298 and Ser336 by AMPK102. Nevertheless, recent studies from Zou׳s group demonstrated that there was no difference between macrophage-specific AMPK deficiency in ApoE–/– mice and corresponding ApoE–/– mice in western diet–induced atherosclerotic plaque formation and plaque instability, which robustly questions the role of macrophage AMPK in atherosclerosis103, 104.

Figure 3.

AMPK participates in regulation of macrophage cholesterol homeostasis and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated production of inflammation factors. AMPK activation by various agonists (A769662, salicylic acid and AICAR, etc.) or overexpressing constitutively active AMPK upregulates the expression of cholesterol transporter ABCA1 or ABCG1, which may be related to increased expression of nuclear transcription factor LXRα, resulting in accumulated cholesterol efflux to mature HDL. In the meantime, increased PP2A activity stimulated by AMPK causes p65 dephosphorylation and subsequent decreased expression of scavenger receptor LOX-1, resulting in reduced oxLDL uptake and cholesterol accumulation in further. In addition, LPS stimulation can downregulate AMPK activity in macrophage. AMPK activation by pharmacological agonists blocks LPS-stimulated increase of secretary proinflammatory factors by SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of p65.

Simultaneously, AMPK seems to participate in inflammatory cytokine release in macrophages, since reduced AMPK activity was found in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated macrophages105. Accordingly, either activating AMPK in macrophages by pharmacological agonists or constitutive expression of active AMPK attenuates LPS-induced proinflammatory factors, whereas the level of anti-inflammatory cytokine increases, which may be mediated by the reduced acetylation and transcription activity of NF-κB induced by Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1)106, 107, 108 (Fig. 3). Moreover, AMPK-mediated activation of nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome was demonstrated to be involved in both saturated fatty acid–induced inflammation in macrophages and the anti-inflammatory effect of monounsaturated fatty acid109, 110. Likewise, the NLRP3 inflammasome can also be activated by crystalline cholesterol, an endogenous risk in atherosclerotic progression111. However, whether AMPK can regulate this process remains to be addressed.

Vascular dysfunction is acknowledged as an early stage in atherosclerosis and is mainly caused by infiltration of immune cells in the vascular wall, inflammation, oxidative stress, impaired NO bioavailability and endothelial cell apoptosis. All these contributors may be concurrent with a reduction of AMPK activity in aortic endothelium112. Consequently, activating vascular AMPK, then altering all above contributors, is probably an effective way to maintain cardiovascular health. It has been demonstrated that expressing constitutively active AMPK in cultured human aortic endothelial cells inhibit TNFα-stimulated leukocyte adhesion associated with reduced monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1) secretion113. AMPK activation by adiponectin reverses palmitate-induced ROS production and following mitogen-activated protein kinase p38-mediated apoptosis in endothelial cells114. Metformin was found to reduce oxidative stress, increase NO bioavailability and restore endothelial function through activation of AMPK/peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor δ (PPARδ) pathway115. Several other direct or indirect AMPK agonists were also verified to enhance vascular function in succession116. In addition, activation of AMPK promotes vasorelaxation in an endothelium and NO-independent manner, suggesting a direct effect of AMPK on vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) apart from endothelium117. Recently, two papers from Zou׳s laboratory were published in succession which revealed that specific AMPKα1 knockout in mouse VSMC promoted western diet–induced aortic calcification while specific AMPKα2 deletion in mouse VSMC induced VSMC phenotypic switching and therefore affected atherosclerotic plaque stability103, 104.

2.4. AMPK in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury

Myocardial ischemia is mainly caused by an interruption in the coronary blood supply, resulting in detrimental effects such as cardiomyocyte death and cardiac dysfunction. Prompt reperfusion restores myocardial blood flow and oxygen supply, but the process of reperfusion brings about myocardial injury as well. The combination of injury incurred during acute myocardial ischemia and reperfusion following ischemia is therefore named ischemia/reperfusion injury. During ischemia, deficiency of oxygen results in increasing anaerobic metabolism, that is increasing glycolytic pathway instead of oxidative phosphorylation118. Although reperfusion of the myocardium can temporally maintain cardiomyocyte viability, metabolic alteration happens since glucose oxidation recovers much slower than fatty acid (FA) oxidation119. These alterations, including increased lactate production, proton generation and decreased intracellular pH, can destroy cardiac efficiency and function120, 121, 122.

It has been suggested that AMPK is activated during ischemia and reperfusion due to the depletion of ATP and the increased activity of AMPK kinases123. AMPK facilitates the delivery of fatty acids via increased cardiac lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity and increased CD36 expression in membrane124, 125. The availability of fatty acids accelerates rates of their utilization, which is also promoted by AMPK activation due to decreased ACC activity, thus reducing malonyl-CoA levels. Enhanced fatty acid oxidation during ischemia and reperfusion suppresses glucose oxidative phosphorylation, which is detrimental to the ischemic myocardium122. Metabolic and pharmacological activation of AMPK promotes GLUT4 translocation to the sarcolemmal membrane62, whereas glucose uptake remains unchanged despite the AMPK activation after ischemia126. AMPK can also increase phosphofructokinase-2 phosphorylation, resulting in enhanced glycolysis during ischemia127.

It seems that ischemia-induced AMPK activation is harmful to the heart due to the stimulation of fatty acid oxidation or the glycolytic pathway instead of glucose oxidation. Chang et al.128 suggested that berberine exerted cardioprotective effects by depressing AMPK activity in ischemic areas of rat heart, whereas AMPK was activated in the non-ischemic areas. In fact, AMPK is more like an adaptive response to satisfy the need of ischemic myocardium for ATP and protect the heart from oxygen deprivation. Brief periods of ischemia preconditioning have been confirmed to provide significant protection to the heart from ischemic injury. AMPK is shown to be involved in the setting of ischemic preconditioning and promotes glucose uptake129. Considerable evidence demonstrates that AMPK stimulation prevents post-ischemic cardiac dysfunction and cell apoptosis upon reperfusion. For example, when isolated hearts from an AMPKα2 kinase dead transgenic mice suffered ischemia attack, cardiac function declined, implying that AMPK activation is necessary for the heart to withstand an ischemia insult130. Besides, treatment with A769662 prior or during ischemia diminishes the cardiac infarct size and decreases myocardial necrosis in an animal model131, 132. It has been suggested that adiponectin prevents the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury in an AMPK and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) dependent manner133. Recently,some physiologically secreted factors and stress-inducible proteins, such as follistatin-like 1, C1q/TNF related protein 9, antithrombin, omentin and sestrin 2, have also been discovered to benefit the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury by stimulating cardiac AMPK134, 135, 136, 137, 138.

2.5. AMPK in neurodegenerative disorder

Life-threatening, incurable diseases such as Alzheimer׳s disease (AD), Parkinson׳s disease (PD) and Huntington׳s disease (HD) are well-known examples of neurodegenerative disorder, defined as a progressive loss of neuronal structure and function. AD is the most familiar dementia, featuring senile plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, primarily caused by accumulation of misfolding Aβ peptides and tau hyperphosphorylation in cortical and hippocampal brain regions139. PD is generally recognized as neurodegenerative motor impairment. PD pathology includes a lack of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and clumps of α-synuclein, also called Lewy body. One of the main contributors to PD is mitochondrial dysfunction associated with a mutated gene140. HD is an age-related disorder involved in both movement and cognizance, induced by CAG triplet repeat expansion in exon 1 of the Htt gene. The major pathological change is the severe decrease of neurons used to synthesize enkephalin and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)141.

In mouse models of AD, PD or HD, pathological activation of brain AMPK has been demonstrated141, 142, 143, consistent with the hypothesis that AMPK plays a key role in the development of senile dementia. However, many other reports have shown that AMPK seems to be a double-edged sword, either aggravating or alleviating neurodegeneration under different circumstances.

In AD, it is well established that AMPK is an important modulator of Aβ generation. Resveratrol prevents Aβ accumulation through promotion of autophagy induced by AMPK activation and mTOR inhibition144. Similar results were acquired with another AMPK agonist AICAR145. Such effects may be associated with changes of neuronal cholesterol and sphingomyelin contents and APP distribution in membrane139. In addition, Greco et al.146 identified that AMPK activation is related to the effect of leptin in neuronal cells, including reduction of tau phosphorylation which could lead to neurofibrillary tangles. On the contrary, some studies pointed out that AMPK inhibition by compound C could improve long-term potentiation (LTP) and alleviate impairments induced by amyloid beta147. Moreover, chronic treatment with metformin was reported to have beneficial effects in females but to enhance memory dysfunction in males, suggesting that the effect of AMPK activation on neuronal cells may be gender-dependent148.

In PD, AMPK activation mitigates dopaminergic dysfunction in Drosophila models149. The neuroprotective effect of ghrelin, a gut hormone, during calorie restriction was mediated by the AMPK signaling pathway150. On the contrary, inhibition of AMPK by compound C in SH-SY5Y cells supplemented with MPP resulted in neuronal cell death143. It was suggested that AMPK cooperates with parkin, an important modulator to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis, which explains why AMPK activation may be beneficial in PD151. However, Kim et al.152 reported that PARP triggers the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons through activation of AMPK as well, adding the complexity of the roles for AMPK in PD.

It was especially highlighted in HD that overactivation of AMPK by high-dose AICAR in striatal neurons facilitated neuronal loss and formation of Htt aggregates141. The underlying mechanism may be related to AMPK as sensor of oxidative stress to elicit neuronal atrophy153. However, Vazquez-Manrique et al.154 suggested that treatment of HD with metformin may be protective. A potential explanation of the controversial results was that AMPK activation may be beneficial in the onset of HD.

3. Conclusions and perspectives

AMPK has evolved to sense diversified energy and metabolic stress such as produced by hormones, cytokines, growth factors, sheer stress, hypoxia, some xenobiotics, etc. Simultaneously, it may help organisms to survive sudden or chronic stress through regulating a great assay of downstream targets involving glucose, fatty acids, cholesterol and amino acid metabolism, glucose transport, mitochondrial function, cell growth, etc. The evidence to date indicates that AMPK is implicated in various human diseases. In the early stage, AMPK was suggested as a prime drug target for type 2 diabetes since several agonists displayed dramatic therapeutic potential in this disease. Later, it was exciting to discover the beneficial effect of metformin on cancer. Thus, the role of AMPK in tumorigenesis draws significant attention. In addition, other human diseases like atherosclerosis, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and neurodegenerative disorder are all closely related to metabolism and inflammation processes in which AMPK has been identified to be a critical contributor. However, further studies are required to investigate the underlying molecular mechanisms. Noteworthy, a paradoxical role of AMPK was observed in these diseases. There are four possible reasons. First, indirect AMPK agonists such as AICAR and biguandes were used in most studies to demonstrate the beneficial effects of AMPK activation, even though the direct agonist A769662 may exert its effects in an AMPK-independent way under certain circumstances. Second, it should be noted that LKB1 has at least 13 other substrates other than AMPK155. When referring to the knockout of LKB1 in mice, some observed phenomena may be mediated by other targets but not AMPK. Third, the widely used AMPK inhibitor, compound C, has also been reported to be highly nonspecific156. Fourth, AMPK is such a sensitive sensor to various stresses and its multi-subunit structure and complicated activity regulatory mechanism bring complexity to understanding the role of AMPK in these diseases. Therefore, appropriate genetic models and tissue- or isomer-specifically direct AMPK agonists are desperately needed to differentiate the functions of AMPK in these human diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (NSFC, Grant Nos. 81273514, 91539126 and 81302827) and grants from Innovation Engineering of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (No. 125161015000150013).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

Contributor Information

Fengzhong Wang, Email: wangfengzhong@sina.com.

Haibo Zhu, Email: zhuhaibo@imm.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Beg Z.H., Allmann D.W., Gibson D.M. Modulation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase activity with cAMP and wth protein fractions of rat liver cytosol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973;54:1362–1369. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(73)91137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson C.A., Kim K.H. Regulation of hepatic acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:378–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carling D., Clarke P.R., Zammit V.A., Hardie D.G. Purification and characterization of the AMP-activated protein kinase. Copurification of acetyl-CoA carboxylase kinase and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase kinase activities. Eur J Biochem. 1989;186:129–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garton A.J., Campbell D.G., Carling D., Hardie D.G., Colbran R.J., Yeaman S.J. Phosphorylation of bovine hormone-sensitive lipase by the AMP-activated protein kinase. A possible antilipolytic mechanism. Eur J Biochem. 1989;179:249–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carling D., Hardie D.G. The substrate and sequence specificity of the AMP-activated protein kinase. phosphorylation of glycogen synthase and phosphorylase kinase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1012:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(89)90014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dasgupta B., Chhipa R.R. Evolving lessons on the complex role of AMPK in normal physiology and cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37:192–206. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Y., Atasoy D., Su H.H., Sternson S.M. Hunger states switch a flip-flop memory circuit via a synaptic AMPK-dependent positive feedback loop. Cell. 2011;146:992–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srivastava A.K., Qin X., Wedhas N., Arnush M., Linkhart T.A., Chadwick R.B. Tumor necrosis factor-α augments matrix metalloproteinase-9 production in skeletal muscle cells through the activation of transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1)-dependent signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35113–35124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705329200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamas P., Hawley S.A., Clarke R.G., Mustard K.J., Green K., Hardie D.G. Regulation of the energy sensor AMP-activated protein kinase by antigen receptor and Ca2+ in T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1665–1670. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrero-Martin G., Hoyer-Hansen M., Garcia-Garcia C., Fumarola C., Farkas T., Lopez-Rivas A. TAK1 activates AMPK-dependent cytoprotective autophagy in TRAIL-treated epithelial cells. EMBO J. 2009;28:677–685. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grahame Hardie D. Regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase by natural and synthetic activators. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warburg O. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science. 1956;124:269–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levine A.J., Puzio-Kuter A.M. The control of the metabolic switch in cancers by oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Science. 2010;330:1340–1344. doi: 10.1126/science.1193494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones R.G., Plas D.R., Kubek S., Buzzai M., Mu J., Xu Y. AMP-activated protein kinase induces a p53-dependent metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2005;18:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang J., Shao S.H., Xu Z.X., Hennessy B., Ding Z., Larrea M. The energy sensing LKB1-AMPK pathway regulates p27kip1 phosphorylation mediating the decision to enter autophagy or apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:218–224. doi: 10.1038/ncb1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rattan R., Giri S., Singh A.K., Singh I. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside inhibits cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in vivovia AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39582–39593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507443200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng B., Jeong J.H., Asara J.M., Yuan Y.Y., Granter S.R., Chin L. Oncogenic B-RAF negatively regulates the tumor suppressor LKB1 to promote melanoma cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2009;33:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen C.H., Yuan P., Perez-Lorenzo R., Zhang Y., Lee S.X., Ou Y. Phosphorylation of BRAF by AMPK impairs BRAF-KSR1 association and cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2013;52:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fogarty S., Ross F.A., Vara Ciruelos D., Gray A., Gowans G.J., Hardie D.G. AMPK causes cell cycle arrest in LKB1-deficient cells via activation of CAMKK2. Mol Cancer Res. 2016;14:683–695. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-15-0479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gwinn D.M., Shackelford D.B., Egan D.F., Mihaylova M.M., Mery A., Vasquez D.S. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scaglia N., Tyekucheva S., Zadra G., Photopoulos C., Loda M. De novo fatty acid synthesis at the mitotic exit is required to complete cellular division. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:859–868. doi: 10.4161/cc.27767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murtola T.J., Syvala H., Pennanen P., Blauer M., Solakivi T., Ylikomi T. The importance of LDL and cholesterol metabolism for prostate epithelial cell growth. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeRan M., Yang J., Shen C.H., Peters E.C., Fitamant J., Chan P. Energy stress regulates hippo-YAP signaling involving AMPK-mediated regulation of angiomotin-like 1 protein. Cell Rep. 2014;9:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mo J.S., Meng Z., Kim Y.C., Park H.W., Hansen C.G., Kim S. Cellular energy stress induces AMPK-mediated regulation of YAP and the Hippo pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:500–510. doi: 10.1038/ncb3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang W., Xiao Z.D., Li X., Aziz K.E., Gan B., Johnson R.L. AMPK modulates Hippo pathway activity to regulate energy homeostasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:490–499. doi: 10.1038/ncb3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faubert B., Boily G., Izreig S., Griss T., Samborska B., Dong Z. AMPK is a negative regulator of the Warburg effect and suppresses tumor growth in vivo. Cell Metab. 2013;17:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faubert B., Vincent E.E., Griss T., Samborska B., Izreig S., Svensson R.U. Loss of the tumor suppressor LKB1 promotes metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells via HIF-1α. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:2554–2559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312570111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan M., Gingras M.C., Dunlop E.A., Nouet Y., Dupuy F., Jalali Z. The tumor suppressor folliculin regulates AMPK-dependent metabolic transformation. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2640–2650. doi: 10.1172/JCI71749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Possik E., Jalali Z., Nouet Y., Yan M., Gingras M.C., Schmeisser K. Folliculin regulates ampk-dependent autophagy and metabolic stress survival. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rios M., Foretz M., Viollet B., Prieto A., Fraga M., Costoya J.A. AMPK activation by oncogenesis is required to maintain cancer cell proliferation in astrocytic tumors. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2628–2638. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laderoute K.R., Calaoagan J.M., Chao W.R., Dinh D., Denko N., Duellman S. 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) supports the growth of aggressive experimental human breast cancer tumors. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:22850–22864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.576371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borgdorff V., Rix U., Winter G.E., Gridling M., Muller A.C., Breitwieser F.P. A chemical biology approach identifies AMPK as a modulator of melanoma oncogene MITF. Oncogene. 2014;33:2531–2539. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tennakoon J.B., Shi Y., Han J.J., Tsouko E., White M.A., Burns A.R. Androgens regulate prostate cancer cell growth via an AMPK-PGC-1α-mediated metabolic switch. Oncogene. 2014;33:5251–5261. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher K.W., Das B., Kim H.S., Clymer B.K., Gehring D., Smith D.R. AMPK promotes aberrant PGC1β expression to support human colon tumor cell survival. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:3866–3879. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00528-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fox M.M., Phoenix K.N., Kopsiaftis S.G., Claffey K.P. AMP-activated protein kinase α 2 isoform suppression in primary breast cancer alters AMPK growth control and apoptotic signaling. Genes Cancer. 2013;4:3–14. doi: 10.1177/1947601913486346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phoenix K.N., Devarakonda C.V., Fox M.M., Stevens L.E., Claffey K.P. AMPKα2 suppresses murine embryonic fibroblast transformation and tumorigenesis. Genes Cancer. 2012;3:51–62. doi: 10.1177/1947601912452883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ross F.A., MacKintosh C., Hardie D.G. AMP-activated protein kinase: a cellular energy sensor that comes in 12 flavours. Febs J. 2016;283:2987–3001. doi: 10.1111/febs.13698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monteverde T., Muthalagu N., Port J., Murphy D.J. Evidence of cancer-promoting roles for AMPK and related kinases. FEBS J. 2015;282:4658–4671. doi: 10.1111/febs.13534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang X., Wullschleger S., Shpiro N., McGuire V.A., Sakamoto K., Woods Y.L. Important role of the LKB1–AMPK pathway in suppressing tumorigenesis in PTEN-deficient mice. Biochem J. 2008;412:211–221. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosilio C., Lounnas N., Nebout M., Imbert V., Hagenbeek T., Spits H. The metabolic perturbators metformin, phenformin and AICAR interfere with the growth and survival of murine PTEN-deficient T cell lymphomas and human T-ALL/T-LL cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2013;336:114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-Masry O.S., Brown B.L., Dobson P.R. Effects of activation of AMPK on human breast cancer cell lines with different genetic backgrounds. Oncol Lett. 2012;3:224–228. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buzzai M., Jones R.G., Amaravadi R.K., Lum J.J., DeBerardinis R.J., Zhao F. Systemic treatment with the antidiabetic drug metformin selectively impairs p53-deficient tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6745–6752. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu C., Guo Y., Su Y., Zhang X., Luan H., Zhang X. Cordycepin activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) via interaction with the γ1 subunit. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:293–304. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vincent E.E., Coelho P.P., Blagih J., Griss T., Viollet B., Jones R.G. Differential effects of AMPK agonists on cell growth and metabolism. Oncogene. 2015;34:3627–3639. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nair V., Sreevalsan S., Basha R., Abdelrahim M., Abudayyeh A., Rodrigues Hoffman A. Mechanism of metformin-dependent inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and Ras activity in pancreatic cancer: role of specificity protein (Sp) transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:27692–27701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.592576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu X., Chhipa R.R., Pooya S., Wortman M., Yachyshin S., Chow L.M. Discrete mechanisms of mTOR and cell cycle regulation by AMPK agonists independent of AMPK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E435–E444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311121111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janzer A., German N.J., Gonzalez-Herrera K.N., Asara J.M., Haigis M.C., Struhl K. Metformin and phenformin deplete tricarboxylic acid cycle and glycolytic intermediates during cell transformation and NTPs in cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:10574–10579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409844111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Honjo S., Ajani J.A., Scott A.W., Chen Q., Skinner H.D., Stroehlein J. Metformin sensitizes chemotherapy by targeting cancer stem cells and the mTOR pathway in esophageal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2014;45:567–574. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hemminki A., Markie D., Tomlinson I., Avizienyte E., Roth S., Loukola A. A serine/threonine kinase gene defective in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Nature. 1998;391:184–187. doi: 10.1038/34432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Algire C., Amrein L., Bazile M., David S., Zakikhani M., Pollak M. Diet and tumor LKB1 expression interact to determine sensitivity to anti-neoplastic effects of metformin in vivo. Oncogene. 2011;30:1174–1182. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shackelford D.B., Abt E., Gerken L., Vasquez D.S., Seki A., Leblanc M. LKB1 inactivation dictates therapeutic response of non-small cell lung cancer to the metabolism drug phenformin. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:143–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Birk J.B., Wojtaszewski J.F. Predominant α2/β2/γ3 AMPK activation during exercise in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2006;577:1021–1032. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.120972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DeFronzo R.A., Tripathy D. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32 Suppl 2:S157–S163. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kristensen J.M., Treebak J.T., Schjerling P., Goodyear L., Wojtaszewski J.F. Two weeks of metformin treatment induces AMPK-dependent enhancement of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in mouse soleus muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;306:E1099–E1109. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00417.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chopra I., Li H.F., Wang H., Webster K.A. Phosphorylation of the insulin receptor by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) promotes ligand-independent activation of the insulin signalling pathway in rodent muscle. Diabetologia. 2012;55:783–794. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2407-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jakobsen S.N., Hardie D.G., Morrice N., Tornqvist H.E. 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylates IRS-1 on Ser-789 in mouse C2C12 myotubes in response to 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46912–46916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O׳Neill H.M., Maarbjerg S.J., Crane J.D., Jeppesen J., Jorgensen S.B., Schertzer J.D. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) β1β2 muscle null mice reveal an essential role for AMPK in maintaining mitochondrial content and glucose uptake during exercise. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16092–16097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105062108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beck Jorgensen S., O׳Neill H.M., Hewitt K., Kemp B.E., Steinberg G.R. Reduced AMP-activated protein kinase activity in mouse skeletal muscle does not exacerbate the development of insulin resistance with obesity. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2395–2404. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1483-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barnes B.R., Marklund S., Steiler T.L., Walter M., Hjalm G., Amarger V. The 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase γ3 isoform has a key role in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in glycolytic skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38441–38447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steinberg G.R., O׳Neill H.M., Dzamko N.L., Galic S., Naim T., Koopman R. Whole body deletion of AMP-activated protein kinase β2 reduces muscle AMPK activity and exercise capacity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:37198–37209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brunmair B., Staniek K., Gras F., Scharf N., Althaym A., Clara R. Thiazolidinediones, like metformin, inhibit respiratory complex I: a common mechanism contributing to their antidiabetic actions? Diabetes. 2004;53:1052–1059. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cartee G.D. Roles of TBC1D1 and TBC1D4 in insulin- and exercise-stimulated glucose transport of skeletal muscle. Diabetologia. 2015;58:19–30. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3395-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frosig C., Pehmoller C., Birk J.B., Richter E.A., Wojtaszewski J.F. Exercise-induced TBC1D1 Ser237 phosphorylation and 14-3-3 protein binding capacity in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2010;588:4539–4548. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.194811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shaw R.J., Lamia K.A., Vasquez D., Koo S.H., Bardeesy N., Depinho R.A. The kinase LKB1 mediates glucose homeostasis in liver and therapeutic effects of metformin. Science. 2005;310:1642–1646. doi: 10.1126/science.1120781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Foretz M., Hebrard S., Leclerc J., Zarrinpashneh E., Soty M., Mithieux G. Metformin inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis in mice independently of the LKB1/AMPK pathway via a decrease in hepatic energy state. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2355–2369. doi: 10.1172/JCI40671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miller R.A., Chu Q., Xie J., Foretz M., Viollet B., Birnbaum M.J. Biguanides suppress hepatic glucagon signalling by decreasing production of cyclic AMP. Nature. 2013;494:256–260. doi: 10.1038/nature11808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Madiraju A.K., Erion D.M., Rahimi Y., Zhang X.M., Braddock D.T., Albright R.A. Metformin suppresses gluconeogenesis by inhibiting mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase. Nature. 2014;510:542–546. doi: 10.1038/nature13270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fullerton M.D., Galic S., Marcinko K., Sikkema S., Pulinilkunnil T., Chen Z.-P. Single phosphorylation sites in Acc1 and Acc2 regulate lipid homeostasis and the insulin-sensitizing effects of metformin. Nat Med. 2013;19:1649–1654. doi: 10.1038/nm.3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cao J., Meng S., Chang E., Beckwith-Fickas K., Xiong L., Cole R.N. Low concentrations of metformin suppress glucose production in hepatocytes through AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) J Biol Chem. 2014;289:20435–20446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.567271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meng S., Cao J., He Q., Xiong L., Chang E., Radovick S. Metformin activates AMP-activated protein kinase by promoting formation of the αβγ heterotrimeric complex. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:3793–3802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.604421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johanns M., Lai Y.C., Hsu M.F., Jacobs R., Vertommen D., Van Sande J. AMPK antagonizes hepatic glucagon-stimulated cyclic AMP signalling via phosphorylation-induced activation of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 4B. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10856. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rainero E., Cianflone C., Porporato P.E., Chianale F., Malacarne V., Bettio V. The diacylglycerol kinase α/atypical PKC/β1 integrin pathway in SDF-1α mammary carcinoma invasiveness. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Turban S., Hajduch E. Protein kinase C isoforms: mediators of reactive lipid metabolites in the development of insulin resistance. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gaidhu M.P., Fediuc S., Anthony N.M., So M., Mirpourian M., Perry R.L. Prolonged AICAR-induced AMP-kinase activation promotes energy dissipation in white adipocytes: novel mechanisms integrating HSL and ATGL. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:704–715. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800480-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Y., Xu S., Mihaylova M.M., Zheng B., Hou X., Jiang B. AMPK phosphorylates and inhibits SREBP activity to attenuate hepatic steatosis and atherosclerosis in diet-induced insulin-resistant mice. Cell Metab. 2011;13:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gaidhu M.P., Fediuc S., Ceddia R.B. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside-induced AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation inhibits basal and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, lipid synthesis, and fatty acid oxidation in isolated rat adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25956–25964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gaidhu M.P., Frontini A., Hung S., Pistor K., Cinti S., Ceddia R.B. Chronic AMP-kinase activation with AICAR reduces adiposity by remodeling adipocyte metabolism and increasing leptin sensitivity. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:1702–1711. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M015354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Koh H.J., Hirshman M.F., He H., Li Y., Manabe Y., Balschi J.A. Adrenaline is a critical mediator of acute exercise-induced AMP-activated protein kinase activation in adipocytes. Biochem J. 2007;403:473–481. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ahmadian M., Abbott M.J., Tang T., Hudak C.S., Kim Y., Bruss M. Desnutrin/ATGL is regulated by AMPK and is required for a brown adipose phenotype. Cell Metab. 2011;13:739–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Daval M., Diot-Dupuy F., Bazin R., Hainault I., Viollet B., Vaulont S. Anti-lipolytic action of AMP-activated protein kinase in rodent adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25250–25257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wu Y., Song P., Zhang W., Liu J., Dai X., Liu Z. Activation of AMPKα2 in adipocytes is essential for nicotine-induced insulin resistance in vivo. Nat Med. 2015;21:373–382. doi: 10.1038/nm.3826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Granot Z., Swisa A., Magenheim J., Stolovich-Rain M., Fujimoto W., Manduchi E. LKB1 regulates pancreatic β cell size, polarity, and function. Cell Metab. 2009;10:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fu A., Ng A.C., Depatie C., Wijesekara N., He Y., Wang G.S. Loss of Lkb1 in adult β cells increases β cell mass and enhances glucose tolerance in mice. Cell Metab. 2009;10:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sun G., Tarasov A.I., McGinty J.A., French P.M., McDonald A., Leclerc I. LKB1 deletion with the RIP2.Cre transgene modifies pancreatic β-cell morphology and enhances insulin secretion in vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E1261–E1273. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00100.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sun G., Tarasov A.I., McGinty J., McDonald A., da Silva Xavier G., Gorman T. Ablation of AMP-activated protein kinase α1 and α2 from mouse pancreatic β cells and RIP2.Cre neurons suppresses insulin release in vivo. Diabetologia. 2010;53:924–936. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1692-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kone M., Pullen T.J., Sun G., Ibberson M., Martinez-Sanchez A., Sayers S. LKB1 and AMPK differentially regulate pancreatic β-cell identity. FASEB J. 2014;28:4972–4985. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-257667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang L., Khambu B., Zhang H., Yin X.M. Autophagy in alcoholic liver disease, self-eating triggered by drinking. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39 Suppl 1:S2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bachar-Wikstrom E., Wikstrom J.D., Ariav Y., Tirosh B., Kaiser N., Cerasi E. Stimulation of autophagy improves endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:1227–1237. doi: 10.2337/db12-1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Park S.H., Ryu S.Y., Yu W.J., Han Y.E., Ji Y.S., Oh K. Leptin promotes KATP channel trafficking by AMPK signaling in pancreatic β-cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:12673–12678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216351110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim J.W., You Y.H., Ham D.S., Yang H.K., Yoon K.H. The paradoxical effects of AMPK on insulin gene expression and glucose-induced insulin secretion. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117:239–246. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yavari A., Stocker C.J., Ghaffari S., Wargent E.T., Steeples V., Czibik G. Chronic activation of γ2 AMPK induces obesity and reduces β cell function. Cell Metab. 2016;23:821–836. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Varela L., Horvath T.L. Leptin and insulin pathways in POMC and AgRP neurons that modulate energy balance and glucose homeostasis. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:1079–1086. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Andersson U., Filipsson K., Abbott C.R., Woods A., Smith K., Bloom S.R. AMP-activated protein kinase plays a role in the control of food intake. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12005–12008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Minokoshi Y., Alquier T., Furukawa N., Kim Y.B., Lee A., Xue B. AMP-kinase regulates food intake by responding to hormonal and nutrient signals in the hypothalamus. Nature. 2004;428:569–574. doi: 10.1038/nature02440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Claret M., Smith M.A., Batterham R.L., Selman C., Choudhury A.I., Fryer L.G. AMPK is essential for energy homeostasis regulation and glucose sensing by POMC and AgRP neurons. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2325–2336. doi: 10.1172/JCI31516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Oh T.S., Cho H., Cho J.H., Yu S.W., Kim E.K. Hypothalamic AMPK-induced autophagy increases food intake by regulating NPY and POMC expression. Autophagy. 2016:1–17. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1215382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fullerton M.D., Ford R.J., McGregor C.P., LeBlond N.D., Snider S.A., Stypa S.A. Salicylate improves macrophage cholesterol homeostasis via activation of AMPK. J Lipid Res. 2015;56:1025–1033. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M058875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li D., Wang D., Wang Y., Ling W., Feng X., Xia M. Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase induces cholesterol efflux from macrophage-derived foam cells and alleviates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:33499–33509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.159772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen B., Li J., Zhu H. AMP-activated protein kinase attenuates oxLDL uptake in macrophages through PP2A/NF-κB/LOX-1 pathway. Vasc Pharmacol. 2016;85:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Namgaladze D., Kemmerer M., von Knethen A., Brune B. AICAR inhibits PPARγ1 during monocyte differentiation to attenuate inflammatory responses to atherogenic lipids. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;98:479–487. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Huang Z., Dong F., Li S., Chu M., Zhou H., Lu Z. Berberine-induced inhibition of adipocyte enhancer-binding protein 1 attenuates oxidized low-density lipoprotein accumulation and foam cell formation in phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-induced macrophages. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;690:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim K.Y., Baek A., Hwang J.E., Choi Y.A., Jeong J., Lee M.S. Adiponectin-activated AMPK stimulates dephosphorylation of AKT through protein phosphatase 2A activation. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4018–4026. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cai Z., Ding Y., Zhang M., Lu Q., Wu S., Zhu H. Ablation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase α1 in vascular smooth muscle cells promotes diet-induced atherosclerotic calcification in vivo. Circ Res. 2016;119:422–433. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ding Y., Zhang M., Zhang W., Lu Q., Cai Z., Song P. AMP-activated protein kinase alpha 2 deletion induces VSMC phenotypic switching and reduces features of atherosclerotic plaque stability. Circ Res. 2016;119:718–730. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Steinberg G.R., Michell B.J., van Denderen B.J., Watt M.J., Carey A.L., Fam B.C. Tumor necrosis factor α–induced skeletal muscle insulin resistance involves suppression of AMP-kinase signaling. Cell Metab. 2006;4:465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jeong H.W., Hsu K.C., Lee J.W., Ham M., Huh J.Y., Shin H.J. Berberine suppresses proinflammatory responses through AMPK activation in macrophages. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E955–E964. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90599.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wolf A.M., Wolf D., Rumpold H., Enrich B., Tilg H. Adiponectin induces the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-1RA in human leukocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323:630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yang Z., Kahn B.B., Shi H., Xue B.Z. Macrophage alpha1 AMP-activated protein kinase (α1AMPK) antagonizes fatty acid-induced inflammation through SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:19051–19059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wen H., Gris D., Lei Y., Jha S., Zhang L., Huang M.T. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:408–415. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Finucane O.M., Lyons C.L., Murphy A.M., Reynolds C.M., Klinger R., Healy N.P. Monounsaturated fatty acid–enriched high-fat diets impede adipose NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IL-1β secretion and insulin resistance despite obesity. Diabetes. 2015;64:2116–2128. doi: 10.2337/db14-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Duewell P., Kono H., Rayner K.J., Sirois C.M., Vladimer G., Bauernfeind F.G. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464:1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Weikel K.A., Cacicedo J.M., Ruderman N.B., Ido Y. Glucose and palmitate uncouple AMPK from autophagy in human aortic endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2015;308:C249–C263. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00265.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ewart M.A., Kennedy S. AMPK and vasculoprotection. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;131:242–253. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kim J.E., Song S.E., Kim Y.W., Kim J.Y., Park S.C., Park Y.K. Adiponectin inhibits palmitate-induced apoptosis through suppression of reactive oxygen species in endothelial cells: involvement of cAMP/protein kinase A and AMP-activated protein kinase. J Endocrinol. 2010;207:35–44. doi: 10.1677/JOE-10-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cheang W.S., Tian X.Y., Wong W.T., Lau C.W., Lee S.S., Chen Z.Y. Metformin protects endothelial function in diet-induced obese mice by inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress through 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:830–836. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fullerton M.D., Steinberg G.R., Schertzer J.D. Immunometabolism of AMPK in insulin resistance and atherosclerosis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;366:224–234. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Miyabe M., Ohashi K., Shibata R., Uemura Y., Ogura Y., Yuasa D. Muscle-derived follistatin-like 1 functions to reduce neointimal formation after vascular injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:111–120. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Oliver M.F., Opie L.H. Effects of glucose and fatty acids on myocardial ischaemia and arrhythmias. Lancet. 1994;343:155–158. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lopaschuk G.D., Wambolt R.B., Barr R.L. An imbalance between glycolysis and glucose oxidation is a possible explanation for the detrimental effects of high levels of fatty acids during aerobic reperfusion of ischemic hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;264:135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lopaschuk G.D. Alterations in fatty acid oxidation during reperfusion of the heart after myocardial ischemia. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:11A–16AA. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Liu Q., Docherty J.C., Rendell J.C., Clanachan A.S., Lopaschuk G.D. High levels of fatty acids delay the recovery of intracellular pH and cardiac efficiency in post-ischemic hearts by inhibiting glucose oxidation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:718–725. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01803-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Liu B., el Alaoui-Talibi Z., Clanachan A.S., Schulz R., Lopaschuk G.D. Uncoupling of contractile function from mitochondrial TCA cycle activity and MVO2 during reperfusion of ischemic hearts. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H72–H80. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.1.H72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Altarejos J.Y., Taniguchi M., Clanachan A.S., Lopaschuk G.D. Myocardial ischemia differentially regulates LKB1 and an alternate 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:183–190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pulinilkunnil T., Puthanveetil P., Kim M.S., Wang F., Schmitt V., Rodrigues B. Ischemia-reperfusion alters cardiac lipoprotein lipase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Habets D.D., Coumans W.A., Voshol P.J., den Boer M.A., Febbraio M., Bonen A. AMPK-mediated increase in myocardial long-chain fatty acid uptake critically depends on sarcolemmal CD36. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;355:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Omar M.A., Fraser H., Clanachan A.S. Ischemia-induced activation of AMPK does not increase glucose uptake in glycogen-replete isolated working rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1266–H1273. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01087.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Marsin A.S., Bertrand L., Rider M.H., Deprez J., Beauloye C., Vincent M.F. Phosphorylation and activation of heart PFK-2 by AMPK has a role in the stimulation of glycolysis during ischaemia. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1247–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00742-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Chang W., Zhang M., Li J., Meng Z., Xiao D., Wei S. Berberine attenuates ischemia-reperfusion injury via regulation of adenosine-5′-monophosphate kinase activity in both non-ischemic and ischemic areas of the rat heart. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2012;26:467–478. doi: 10.1007/s10557-012-6422-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Nishino Y., Miura T., Miki T., Sakamoto J., Nakamura Y., Ikeda Y. Ischemic preconditioning activates AMPK in a PKC-dependent manner and induces GLUT4 up-regulation in the late phase of cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:610–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Russell R.R., 3rd, Li J., Coven D.L., Pypaert M., Zechner C., Palmeri M. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates ischemic glucose uptake and prevents postischemic cardiac dysfunction, apoptosis, and injury. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:495–503. doi: 10.1172/JCI19297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kim A.S., Miller E.J., Wright T.M., Li J., Qi D., Atsina K. A small molecule AMPK activator protects the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Paiva M.A., Rutter-Locher Z., Goncalves L.M., Providencia L.A., Davidson S.M., Yellon D.M. Enhancing AMPK activation during ischemia protects the diabetic heart against reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H2123–H2134. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00707.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Shibata R., Sato K., Pimentel D.R., Takemura Y., Kihara S., Ohashi K. Adiponectin protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through AMPK- and COX-2–dependent mechanisms. Nat Med. 2005;11:1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/nm1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Morrison A., Chen L., Wang J., Zhang M., Yang H., Ma Y. Sestrin2 promotes LKB1-mediated AMPK activation in the ischemic heart. FASEB J. 2015;29:408–417. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-258814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ma Y., Wang J., Gao J., Yang H., Wang Y., Manithody C. Antithrombin up-regulates AMP-activated protein kinase signalling during myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113:338–349. doi: 10.1160/TH14-04-0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kambara T., Shibata R., Ohashi K., Matsuo K., Hiramatsu-Ito M., Enomoto T. C1q/tumor necrosis factor-related protein 9 protects against acute myocardial injury through an adiponectin receptor I-AMPK-dependent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:2173–2185. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01518-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ogura Y., Ouchi N., Ohashi K., Shibata R., Kataoka Y., Kambara T. Therapeutic impact of follistatin-like 1 on myocardial ischemic injury in preclinical models. Circulation. 2012;126:1728–1738. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.115089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kataoka Y., Shibata R., Ohashi K., Kambara T., Enomoto T., Uemura Y. Omentin prevents myocardial ischemic injury through AMP-activated protein kinase- and Akt-dependent mechanisms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2722–2733. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Cai Z., Yan L.J., Li K., Quazi S.H., Zhao B. Roles of AMP-activated protein kinase in Alzheimer׳s disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2012;14:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s12017-012-8173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Corti O., Lesage S., Brice A. What genetics tells us about the causes and mechanisms of Parkinson׳s disease. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:1161–1218. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ju T.C., Chen H.M., Lin J.T., Chang C.P., Chang W.C., Kang J.J. Nuclear translocation of AMPK-α1 potentiates striatal neurodegeneration in Huntington׳s disease. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:209–227. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201105010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Mairet-Coello G., Courchet J., Pieraut S., Courchet V., Maximov A., Polleux F. The CAMKK2-AMPK kinase pathway mediates the synaptotoxic effects of Aβ oligomers through Tau phosphorylation. Neuron. 2013;78:94–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Choi J.S., Park C., Jeong J.W. AMP-activated protein kinase is activated in Parkinson׳s disease models mediated by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Vingtdeux V., Giliberto L., Zhao H., Chandakkar P., Wu Q., Simon J.E. AMP-activated protein kinase signaling activation by resveratrol modulates amyloid-β peptide metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9100–9113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.060061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Won J.S., Im Y.B., Kim J., Singh A.K., Singh I. Involvement of AMP-activated-protein-kinase (AMPK) in neuronal amyloidogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;399:487–491. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Greco S.J., Sarkar S., Johnston J.M., Tezapsidis N. Leptin regulates tau phosphorylation and amyloid through AMPK in neuronal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;380:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Ma T., Chen Y., Vingtdeux V., Zhao H., Viollet B., Marambaud P. Inhibition of AMP-activated protein kinase signaling alleviates impairments in hippocampal synaptic plasticity induced by amyloid β. J Neurosci. 2014;34:12230–12238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1694-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.DiTacchio K.A., Heinemann S.F., Dziewczapolski G. Metformin treatment alters memory function in a mouse model of Alzheimer׳s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44:43–48. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Ng C.H., Guan M.S., Koh C., Ouyang X., Yu F., Tan E.K. AMP kinase activation mitigates dopaminergic dysfunction and mitochondrial abnormalities in Drosophila models of Parkinson׳s disease. J Neurosci. 2012;32:14311–14317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0499-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Bayliss J.A., Lemus M.B., Stark R., Santos V.V., Thompson A., Rees D.J. Ghrelin-AMPK signaling mediates the neuroprotective effects of calorie restriction in Parkinson׳s disease. J Neurosci. 2016;36:3049–3063. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4373-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]