Abstract

Applied nitrogen (N) fertilizer significantly increases the leaf yield. However, most N is not utilized by the plant, negatively impacting the environment. To date, little is known regarding N utilization genes and mechanisms in the leaf production. To understand this, we investigated transcriptomes using RNA-seq and amino acid levels with N treatment in tea (Camellia sinensis), the most popular beverage crop. We identified 196 and 29 common differentially expressed genes in roots and leaves, respectively, in response to ammonium in two tea varieties. Among those genes, AMT, NRT and AQP for N uptake and GOGAT and GS for N assimilation were the key genes, validated by RT-qPCR, which expressed in a network manner with tissue specificity. Importantly, only AQP and three novel DEGs associated with stress, manganese binding, and gibberellin-regulated transcription factor were common in N responses across all tissues and varieties. A hypothesized gene regulatory network for N was proposed. A strong statistical correlation between key genes’ expression and amino acid content was revealed. The key genes and regulatory network improve our understanding of the molecular mechanism of N usage and offer gene targets for plant improvement.

Introduction

Nitrogen (N) is an essential element in biological systems, including DNA, proteins, and amino acids. N utilization efficiency (NUE) is the key issue in N usage in plants though the definition of NUE may differ. In agriculture, NUE can be simply calculated as the ratio of gained biomass or produce with supplied N to that without supplied N. However, NUE in plants is very low1. More than half of active N is lost2, which results in considerable threats to our environment via water pollution and biodiversity changes. The excessive N in the environment costs at least 100 million dollars per year in the European Union3. Therefore, increasing global attention to reduce N emission has risen, and a 20% improvement of NUE by 2020 was proposed3. One of the best solutions to this problem is to make full use of or to engineer NUE genes3, 4.

The inorganic ammonium and nitrate are the two major sources of mineral N in soil. To date, the N uptake in some plants is known to be regulated by the ammonium transporter gene AMT, the nitrate transporter gene NRT, and the aquaporin protein gene AQP 5–8. Multiple AMT and NRT homologous genes may exist in some plant species5, 9. In Arabidopsis, eleven homologous NRT genes were identified but they play very different roles including nitrate inducible, repressible or constitutive9. AMT expression is dependent on N signal in roots and spatial arrangement10 while NRT expression is regulated by the N signal of the whole plant in Arabidopsis 11. A reciprocal regulation between homologs of AMT or NRT and between AMT and NRT was reported9, 11, 12. Nitrate can enhance the uptake of ammonium while the latter will repress the uptake of nitrate in rice13, 14. However, the reverse is true in tea root15. AQP has been found to involve in water transportation by upregulating its gene expression in supplied N source in poplar16, rice17 and barley7. N uptake is also associated with phytohormones such as cytokinins, abscisic acid and auxin18, or transcription factors osDOF18 in rice19.

Tea is the most popular non-alcoholic natural beverage in the world. Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntzes is widely grown in more than 52 countries as an important commercial crop for leaf production, from which tea is made. China and India produce the most tea, with 1.9 million and 1.2 million metric tons of tea in 2013, respectively, according to statistics at http://www.statista.com. Nitrogen fertilizer is critical for increasing the tea leaf production in farming, which is also true for other crops20. N fertilizer is widely applied in tea farming. However, less than one quarter of applied N can be used by the wooden tea crop, meaning that the remaining will potentially be returned to the environment21. Therefore, the improvement of NUE in tea plant may be the key to these problems.

To date, few studies were published on kinetics or physiology of N uptake in tea. Most tea varieties prefer ammonium than nitrate at the N uptake rate15, the kinetics of N absorption, content of free amino acid, biomass and the related enzymes in the N assimilation22–24. A recent study showed that in tea roots, nitrate inhibits ammonium uptake while ammonium increases the uptake of nitrate in the early stage15. However, little is known regarding NUE genes in tea.

Amino acids are important storage compounds of N in plants4. After the uptake of active form of N, the glutamine (Gln) synthetase gene (GOGAT) and glutamic acid (Glu) synthetase gene (GS) play roles in N assimilation into amino acids in plants5. Higher glutamine concentration in roots represses the AMT and NRT expression in Arabidopsis 14, 25. In tea, Glu and theanine are the major amino acids. The high amount of theanine, a tea specific amino acid, is usually used as an index of good tea quality. Theanine is mainly synthesized in the roots26, and is then transferred to the aerial part of the plant. In general, theanine accounts for approximately 1–2% of the dry weight of tea leaves27, and accounts for approximately 60–70% of the total amount of free amino acids in tea26. However, the gene encoding theanine synthetase is still unclear by now. We discovered a tea variety Baojinghuangjin tea 1# (HJ) with higher levels of amino acids and a higher leaf yield than the common used variety Fudingdabaicha (FD) after applying N fertilizer28, suggesting that the variety HJ has a higher NUE. Therefore, HJ will be an ideal tea variety to be investigated for gene candidates responsible for NUE compared to other teas.

RNA-seq technology has been widely used in biological studies to sensitively discover transcripts on a single-nucleotide level and to quantify gene expression levels. For example, RNA-seq is a powerful approach for discovering key gene candidates in Populus 29, Tabacum 30, Arabidopsis thaliana and wheat31, 32. In C. sinensis, RNA-seq analysis has revealed some known genes in the secondary metabolic pathways, such as theanine biosynthesis33, and stresses, such as cold34, shade35 and drought36, 37. However, the key genes that control NUE in tea plant have not been reported. Because the whole tea plant genome sequence is not currently publicly available, we used RNA-seq to de novo identify NUE genes in this study.

In this study, we focused on NUE, especially on the genes responsible for N uptake from soil by roots and N assimilation into amino acids in tea plants. We used Illumina RNA-seq technology and amino acid measurement to identify genes and their regulation network associated with N transport and assimilation in response to ammonium fertilizer in the tea crop. Transcriptome analysis was conducted on both the leaves and roots with or without N treatment from two tea varieties, HJ and FD. In total, more than 100 million paired-end RNA-seq reads were generated, and approximately 20,000 unigenes were obtained by de novo assembly. The tea plant genes AMT, AQP, GS and GOGAT were identified as differentially expressed in the regulation of N uptake and cross talk in a network manner, with tissue specificity. Most importantly, we identified three novel genes differentially regulating N use in all tissues across tea varieties with predicted functions in stress, manganese binding and gibberellin (GA) regulated transcription factors. Combining with gene regulation and amino acid content, we found a strong correlation in statistics between gene expression and amino acid content. The shared and specific genes on NUE in tea plant can be applied to NUE improvement in tea and other plants.

Results

De novo assembly of C. sinensis transcripts

We treated two C. sinensis varieties, HJ and FD, with ammonium and extracted mRNA from young leaf tissues and tender roots with and without ammonium treatment (Fig. 1). The transcriptomes of these samples were then examined using RNA-seq technology. A total of 100,232,165 and 102,115,437 clean reads were generated from the tissues of HJ and FD, respectively. Then, the reads were de novo assembled into transcripts by using Trinity software (version 201308)38. We obtained very similar total numbers of unigenes: 194,519 and 198,118, in HJ and FD, respectively. The average lengths of the unigenes were 528 and 510 bp in HJ and FD, respectively (Table S1). The RNA-seq reads and the assembly are publicly available at NCBI under the master accession number SRP077092.

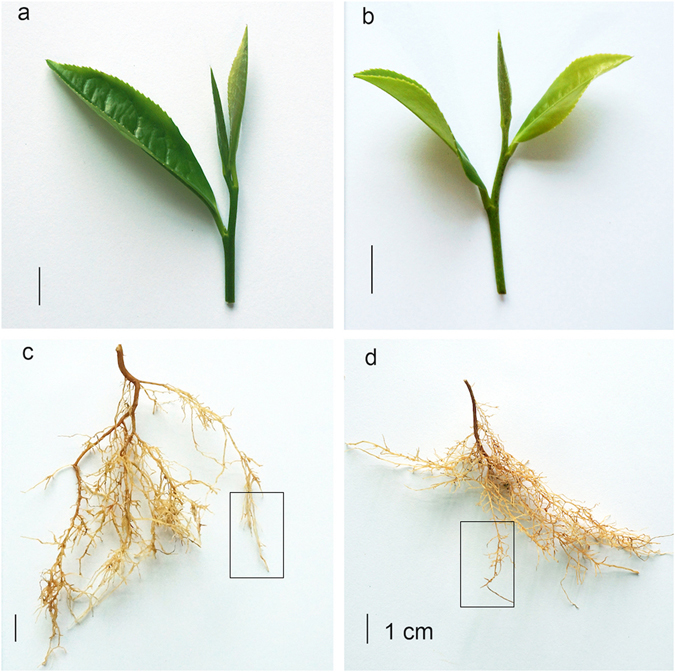

Figure 1.

C. sinensis tea leaf and root samples. Images show the used tea samples without ammonium treatment. (a,b) are the representative leaves of the C. sinensis varieties HJ and FD. Only the buds and leaves were used in the study. (c,d) are the representative roots of the C. sinensis varieties HJ and FD. The boxed roots represent the types of roots used for analysis.

Gene functional annotation

The unigenes were annotated by similarity searching (E-value ≤ 10−10 for Pfam, E-value ≤ 10−5 for others) against the following databases: NR, Swiss-Prot, GO, COG, KOG, and KEGG. A total of 86,856 (44.65%) and 82,305 (41.54%) unigenes were annotated in the HJ and FD, respectively (Table S2).

Based on sequence homology, 60,544 (31.12%) unigenes of HJ were distributed among three main GO categories: cellular component (16 functional groups, dominated by ‘cell part’ and ‘cell’), molecular function (17 functional groups, dominated by ‘catalytic activity’ and ‘binding’), and biological process (20 functional groups, dominated by ‘metabolic process’ and ‘cellular process’) (Fig. S1). For FD, 52,026 (26.26%) unigenes were also classified by GO, and the subgroup numbers and dominant terms of each category were the same as those in HJ. In both varieties, more unigenes were classified in biological process than in either of the other two classes.

To further analyze the functions of unigenes in C. sinensis, 19,389 and 18,157 unigenes in HJ and FD were annotated by the KEGG Automatic Annotation Server, respectively. These unigenes were enriched in 118 KEGG pathways. In total, 6,765 (34.89%) and 6,329 (34.86%) unigenes were found in metabolism pathways in HJ and FD, respectively. In HJ, 1,639 (8.45%) unigenes were enriched in the pathways of amino acid metabolism compared to 1,627 (8.96%) unigenes in FD (Fig. S2).

Differentially expressed genes in response to ammonium

The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were measured according to the RNA-seq reads’ abundance and were normalized to fragments per kilobase length per million reads (FPKM). After ammonium treatment, 1,997/635 DEGs were up/down-regulated in the roots while 3,596/306 DEGs were up/down-regulated in the leaves of HJ. Meanwhile, 4,195/345 DEGs were up/down-regulated in the roots while 220/223 DEGs were up/down-regulated in the leaves of FD (Table 1). More DEGs were found in the leaves than in the roots of HJ, while the reverse was true in FD (Table 1). The difference of DEGs may account for the different genetically inherited regulation, including N use efficiency, in the FD and HJ tea varieties.

Table 1.

The regulation of differentially expressed genes after ammonium treatment.

| Roots | Leaves | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| up | down | total | up | down | total | |

| C. sinensis variety HJ | 1,997 | 635 | 2,632 | 3,596 | 306 | 3,902 |

| C. sinensis variety FD | 4,195 | 345 | 4,540 | 220 | 223 | 443 |

The data show the numbers of DEGs after ammonium treatment compared to the blank control. The definition of DEGs was set as more than a two-fold change in FPKM in the RNA-seq data. The phrase up, down, and total represent up, down, and total regulated expression, respectively.

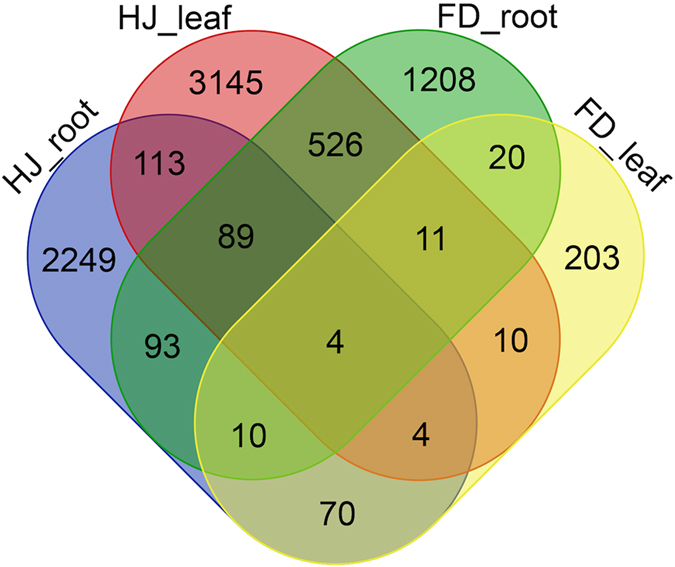

To compare expression differences in response to ammonium treatment in both varieties, we BLASTed DEGs in one variety against the unigene assembly of the other variety reciprocally to find the homologous genes and then assessed whether the genes were DEGs in the other variety. After comparing the DEGs in the same tissues, we found 196 common DEGs in the roots and 29 common DEGs in the leaves of both varieties (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The differentially expressed genes in the roots and leaves of the Camellia HJ and FD in response to ammonium. The number of DEGs between the leaves and roots of two C. sinensis varieties in response to ammonium treatment are shown in this diagram. The phrases HJ_root, HJ_leaf, FD_root and FD_leaf represent the roots or leaves of the HJ variety and the roots or leaves of the FD variety, respectively.

To understand the network pathways involved by the 196 common DEGs in roots, we mapped these DEGs against the known pathways of Arabidopsis and poplar in KEGG database, respectively. Results showed the DEGs were mapped into more pathways of poplar (43 pathways) than Arabidopsis (36 pathways), indicating ammonium responses in tea plant was more similar to poplar tree than Arabidopsis (Table S4). The pathways were distributed rather scattered, suggesting ammonium treatment affected the functions of multiple pathways. The top three DEGs-enriched pathways were the pathway of biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides, and biosynthesis of cofactor and vitamins (Fig. S3). The most affected pathway was biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (Fig. S3). To overview of these pathways, we highlighted the node, where DEGs mapped, in the pathway in the black color and provided the link to the pathway gene in poplar and Arabidopsis (Table S4).

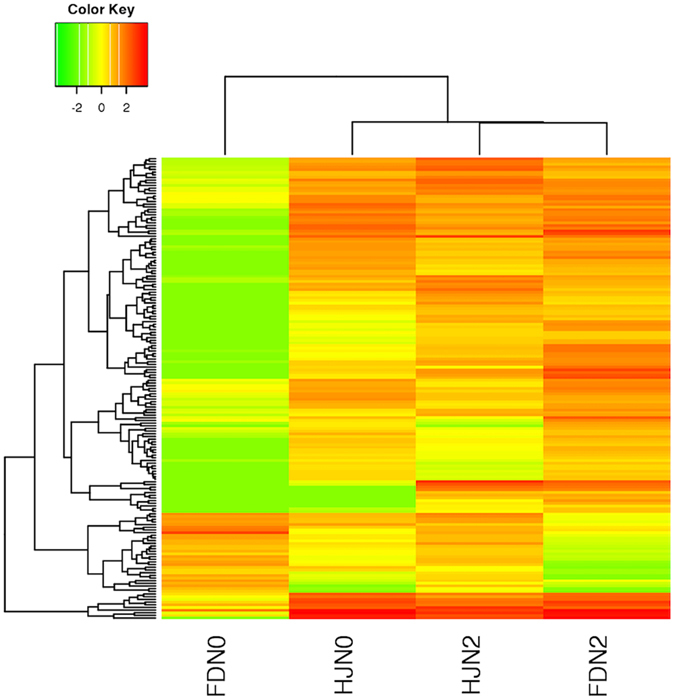

Four shared DEGs were identified in both the leaves and roots across both varieties after treatment (Fig. 2), of which the predicted functions were annotated as “stress response (stress),” “manganese binding ion (Mn), nutrition storage,” “transcription factor (TF), a gibberellin regulated protein” and “aquaporin protein encoded by AQP” (Table S3). We further research for any homologs of these four genes and did not find any homolog in the sequence data of unigenes and transcript spliced isoforms. This finding suggested that the four key shared genes were responsible for common ammonium responses. To our knowledge, this study describes the first time that this set of four genes was discovered in response to ammonium in tea plant. The cluster of DEG expression patterns in roots revealed a high similarity between the HJ variety before ammonium control and FD after ammonium treatment (Fig. 3), indicating that the HJ variety had a higher N response, meaning a higher NUE in HJ than FD.

Figure 3.

The expression patterns of shared differentially expressed genes in the roots of Camellia. The heatmap represents the relative expression levels of 196 common DEGs in the roots of the Camellia varieties HJ and FD. Expression levels were determined in FPKM using RNA-seq and were log2-transformed. The tree diagram represents the similarity between the four samples or between the common genes. “HJN0” and “FDN0” represent C. sinensis HJ/FD treated with 0 g of (NH4)2SO4 (the control), and “HJN2” “FDN2” represent C. sinensis HJ/FD treated with 22 g (NH4)2SO4.

Of the common DEGs, 14 unigenes were identified as N response candidates, as these genes were annotated as ammonium-, or glutamine- or nitrate-related genes. The nitrogen response related genes (N gene) included AMT, NRT, AQP and GS (Table 2), which are known to be involved in ammonium transport and assimilation into amino acids in other plants4.

Table 2.

Differentially expressed genes shared in two Camellia varieties.

| Tissue | Gene ID | Annotated function |

|---|---|---|

| Root | c124953.graph_c1 | ammonium transporter (AMT) |

| c112070.graph_c0 | nitrate transporter (NRT) | |

| c95905.graph_c0 | aquaporin protein (AQP) | |

| c94357.graph_c0 | glutamine synthetase (GS) | |

| Leaf | c95905.graph_c0 | aquaporin protein (AQP) |

| c123483.graph_c 0 | nitrate transporter (NRT) |

DEGs were involved in the process of the transport and assimilation of ammonium in both Camellia varieties. The gene ID is the name of the unigene in the assembly of the Camellia variety HJ.

The expression levels of N genes in response to ammonium

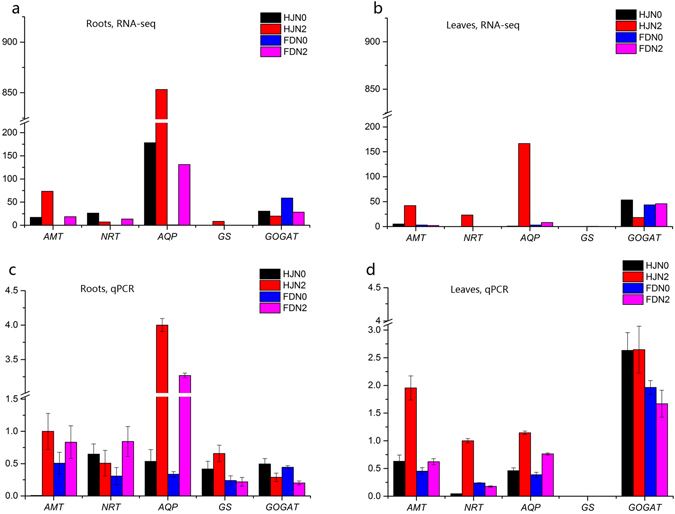

We further analyzed the expression levels in FPKM of N-related genes identified between the two varieties of C. sinensis (Fig. 4). Different regulation patterns of N genes were found in the two varieties. In the control, the expression levels of AMT, NRT and GS was very low while that of AQP was high (Fig. 4a,b). Ammonium induced an increase in AMT, GS and AQP expression levels in both tissues of both varieties (Fig. 4a,b). NRT expression displayed distinct patterns in different tissues of the two varieties. NRT was very lowly expressed in the leaves in the controls of both varieties. After ammonium treatment, NRT expression was significantly induced in the leaves of HJ. In the roots, NRT expression was decreased in HJ but induced in FD. Ammonium also down-regulated the Glu synthetase gene GOGAT expression except in the leaves of FD (Fig. 4a,b), indicating an inhibition of NH4 + by product from its catalysis Gln to Glu. To validate the RNA-seq results, we used the RT-qPCR to examine these key gene expression levels in the roots and leaves of HJ and FD (Fig. 4c,d). In HJ and FD, the trend of expressions of the five genes were similar to the results from RNA-seq data in leaves and roots of tea plant.

Figure 4.

The expression levels of nitrogen associated in Camellia in response to ammonium. (a) The expression levels of genes in FPKM in RNA-seq data in the roots. (b) The expression levels of genes in FPKM in RNA-seq data in the leaves. (c) The relative expression levels of genes in the roots confirmed by RT-qPCR. (d) The expression levels of genes in the leaves confirmed by RT-qPCR. “HJN0” “FDN0” represent C. sinensis HJ/FD treated with 0 g of (NH4)2SO4 (the control). “HJN2” “FDN2” represent C. sinensis HJ/FD treated with 22 g of (NH4)2SO4. AMT, NRT, AQP, GS and GOGAT, representing the genes of the ammonium transporter, nitrate transporter, aquaporin protein, glutamine synthetase, and glutamic acid synthetase, respectively.

Regulation network of amino acid content in response to ammonium input

Comparing the N-associated metabolites with the N genes is interesting. We measured the amounts of total amino acid, theanine and Glu in the tea leaves (Table 3). Before ammonium treatment, similar amounts of total amino acids were detected in both varieties, but higher amounts of theanine (P < 0.05) and Glu (P < 0.01) were present in the HJ variety compared to FD (Table 3). After treatment, HJ contained significantly higher (P < 0.001) amounts of total amino acids, Glu and theanine compare to FD (Table 3). The major amino acid in HJ tea leaves was theanine, accounting for nearly 70% of the amino acids before treatment and approximately 60% after treatment (Table 3). The relatively decreased percentage of theanine after treatment indicated a higher additive increase of the other amino acids.

Table 3.

The amino acid content in Camellia leaves before and after ammonium treatment.

| C. sinensis variety HJ | C. sinensis variety FD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N0 (mg·g−1) | N2 (mg·g−1) | N0 (mg·g−1) | N2 (mg·g−1) | |

| Glutamic acid (Glu) (percentage) | 4.54 ± 0.12** (10.07%) | 6.20 ± 0.10*** (9.21%) | 3.94 ± 0.15 (8.89%) | 2.99 ± 0.09 (5.21%) |

| Theanine (percentage) | 31.74 ± 0.55* (70.39%) | 40.12 ± 0.54*** (59.59%) | 29.84 ± 0.71 (67.36%) | 35.11 ± 0.38 (61.23%) |

| Total amino acids | 45.09 ± 0.63 | 67.33 ± 0.46*** | 44.3 ± 0.50 | 57.34 ± 0.29 |

The above table shows the content of amino acids in the tea leaves of HJ and FD. N0 represents the control of C. sinensis HJ/FD, and N2 represents the C. sinensis HJ/FD treated with (NH4)2SO4. The percentage is the amount of amino acids relative to total amino acids. *, **, and *** represent statistical t-test P values less than significance levels 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively, in the HJ variety compared to the FD variety at the same N condition.

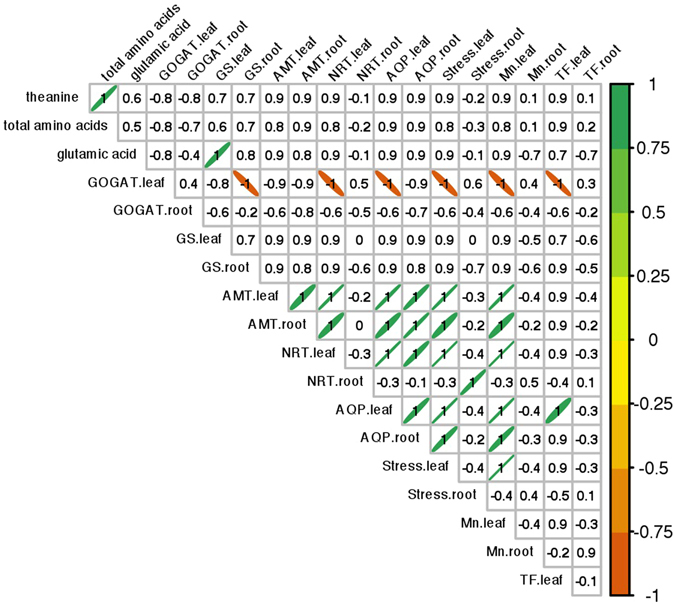

To understand the DE gene expression and their impact on amino acid content, we analyzed the correlation between amino acids and gene expression levels using Pearson correlation statistics. An obvious NUE regulatory network was identified (Fig. 5). The content of theanine positively correlated to the total amount of amino acids, and GS expression positively correlated to Glu in leaves (coefficient = 1, P < 0.05), with the highest coefficient of 1 suggesting the strongest correlation effect. Gene AMT expression positively co-expressed with NRT, AQP, and the remaining three common DEGs in both leaves and roots (Fig. 5). NRT genes in the leaves co-expressed with AQP, the stress gene and the Mn gene identified in this study, while NRT only correlated with the stress gene in roots. AQP positively correlated with the common genes associated with stress and Mn in leaves and roots while also co-expressed with TF in leaves. GOGAT expression in leaves was negatively correlated to NRT, AQP and three common DEG expression levels in leaves (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5). GOGAT expression in leaves was also negatively correlated to GS expression in roots, which may be a remote regulation caused by Gln transferring between the roots and leaves.

Figure 5.

Correlations between amino acid content and gene expression in the Camellia leaves. This diagram shows the correlations between amino acid contents in leaves and gene expression levels. The gene name followed by “.leaf” or “.root” included i) four shared DEGs associated with stress, manganese (Mn), transcript factors (TF) and AQP in both the roots and leaves of two Camellia varieties, ii) differentially expressed N uptake genes AMT and NRT, and iii) Glu metabolism pathway genes GS and GOGAT. The number in each cell represents the coefficient. The significant (P < 0.05) correlations were marked with an ellipse, and the direction denotes a positive or negative correlation.

Discussion

Due to the concern regarding the impact of active N runoff from our environment3, the NUE is a hot topic. The NUE includes N uptake and assimilation into plants, and the current key step is to discover NUE genes4 and their potential variants. Although tea is the most popular beverage, little has been known about NUE genes until recently. Luckily, several genes for N usage in plants have been reported independently in model plants, such as Arabidopsis and rice, and were reviewed by ref. 4. The genes AMT, AQP and NRT play roles in N uptake in roots5–8, and the GS gene is important in N assimilation in leaves5. In this study, we used RNA-seq to investigate the N genes based on expression changes in response to ammonium (NH4 +), a typical preferred active N, in the wooden crop tea. We identified more than 2000 DEGs in response to NH4 + in two different tissues, leaves and roots, of tea plants. These DEGs, including previously reported genes, provided candidate gene resources for further investigating ammonium transport and assimilation in tea and other plants.

Currently, several RNA-seq-based reports on C. sinensis mainly focus on the metabolisms i.e. theanine metabolism33, 39, 40, and stress response such as cold34, 41. Those studies contributed some gene sequences in tea plant and identified some preliminary candidate genes. In contrast to those studies, we designed the N studies before and after ammonium treatment in the roots and leaves of two tea varieties: a recently identified variety HJ with a higher N response and a widely-grown variety FD with an average N response. After several years of investigation, we have confirmed that the HJ variety has a higher free amino acid content in the spring tea leaves compared to other tea plant after applying ammonium. The higher amino acid content indicates a higher quality of tea in the industry. The interesting phenotype encouraged us to investigate the N genes in HJ with the aim for higher NUE gene variants. After comparing the genes’ responses in the roots and leaves of each variety, we identified shared DEGs: 196 in the roots plus 29 in the leaves, with a variety of specific DEGs in response to ammonium during tea leaf production (Fig. 2). This finding suggested that ammonium induced more gene responses in roots than in leaves in the tea varieties.

The DEG expression patterns explained the different NUE and growth stages of the tea varieties HJ and FD. There were more DEGs in the leaves of HJ compared to its roots while there were fewer DEGs in the FD leaves than in the FD roots in response to NH4 + (Table 1). This difference may be due to genetic variance or different leaf starting stages in the early spring. Previous research showed that HJ was an early sprouting tea variety. The stage of one spread leaf and a bud was 5–7 days earlier than FD28. Therefore, our treatment was set to two weeks so that both varieties produced one bud and two leaves after the treatment to reduce the difference caused by leaf developmental stages. However, the greater expression of DEGs in the leaves of HJ compared to FD may still partially result from the earlier leaf development in HJ compared to FD (Table 1).

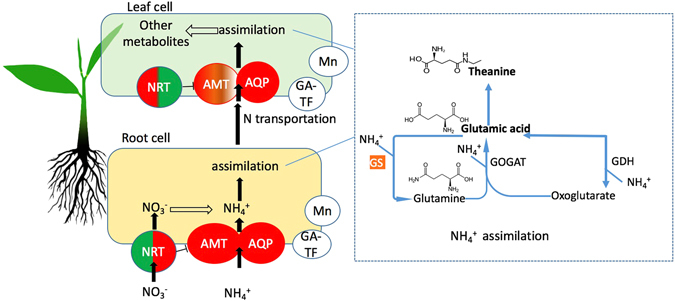

We identified the tea homologs of N genes reported in other plants. To illustrate the gene regulation, we proposed a regulation network (Fig. 6) by adding our new finding to previous understanding4. AMT is an ammonium transporter in plants5, 6, 42, 43. In this study, after ammonium treatment, the AMT gene was differentially up-regulated in the roots of both tea varieties. This result suggested a common AMT induction by NH4 + in the roots of tea plants. However, in the leaves, AMT was up-regulated (8-folds) in HJ while it was unchanged in FD. This difference in AMT level may result from genetic variance of AMT or its regulation, which accounts for the higher NUE in HJ.

Figure 6.

Nitrogen uptake, assimilation in roots and leaves of tea plant. Black and blue arrows represent the movement of ammonium and metabolite pathway, respectively. AMT, NRT, AQP, GS and GOGAT, represent the genes of the ammonium transporter, nitrate transporter, aquaporin protein, glutamine synthetase, and glutamic acid synthetase, respectively. Mn and GA-TF represent new identified manganese binding protein and gibberellin related transcript factors, respectively. Colors shading the protein show the up-regulated (red) or down-regulated (green) expression. Presence of both red and green colors shows varied regulation between the tea variety HJ and FD.

The NRT gene, known for specific nitrate44 and auxin45 uptake, was down-regulated in the roots and up-regulated in the leaves of HJ after ammonium treatment. In contrast, in FD, NRT was up-regulated in the roots of FD while it was unchanged in leaves. It was reported that ammonia increases the uptake of nitrate in tea roots15, but it lasts for a very short time. Our results are from two weeks adaptation to ammonium instead of less than hour in previous publication15. We proposed that this result could be caused by the reciprocal repression of NRT and AMT 12, 46. The higher AMT expression in HJ indicated a stronger repression of NRT, leading to decreased NRT expression in the HJ roots (Table 3, Fig. 4). Alternatively, a higher N uptake suggests a higher conversion to other forms of N, i.e. NO3 − through metabolism, which requires increased NO3 − transportation, meaning also increasing NRT expression. We speculated that the bio-directional regulations dynamically controlled NRT expression, which explained the net increase of NRT in FD roots and HJ leaves because relatively low AMT had less of a repressive effect on NRT (Table 3, Fig. 4). The difference of NRT expression in roots and leaves was also affected by long-distance transport of N. It is possible that NRT expression may also be affected by allelic differences and/or different gene regulation efficiencies between the HJ and FD varieties.

AQP encodes a water channel protein for water and ammonia (NH3) transportation4, 47. We found that AQP expression was significantly up-regulated (5- to 20- fold) in all tissues after ammonium treatment (Fig. 4). Accumulated NH4 + in plant cells will lead to ammonium toxicity1. The observed up-regulation of AQP in both the leaves and roots in both tea varieties may function to buffer the toxicity of NH4 + by water uptake to maintain an osmotic balance. The AQP channel is an alternative way for plants to take up N in the NH3 format48, 49, which is supported by a recently revealed structural function of the AQP protein47 and was demonstrated as in barley roots7. AQP expression in HJ was higher (greater than 8-fold) compared with that of FD in both tissues in the control and the treatment groups, indicating a higher N uptake capability through AQP in HJ. This finding also accounts for the observed higher NUE in HJ compared to FD. Previous studies showed that some mineral nutrients such as P and Ca were up-taken by AQP8. Interestingly, we found the co-occurrences of both increased expression of ion Mn binding gene and increased N up taking, which will be further analyzed in the subsequent investigation.

In this study, we identified four common DEGs in both the leaves and roots across tea varieties in response to ammonium. One gene is AQP, discussed above. The remaining three genes are not well characterized. However, from the conserved sequences of the predicted amino acids of these genes, we predicted their functions as “stress response,” “manganese binding nutrition storage” and “transcription factor, a gibberellin regulated protein.” It is rational for genes to act in “stress response” and “nutrition storage” because NH4 + acts as a type of toxic stress and is also an essential element of nutrition. NH4 + induces hormone-related responses1, so one identified gene functioning as “transcription factor, a gibberellin regulated protein” will also be interesting for NUE. Few transcription factors, i.e., ZmDof1 in maize50, in N responses have been previously identified, and we have found a new one herein. Further studies will focus on the function of these common novel genes. Of course, some specific DEGs which expression change were exclusively in either FD or HJ variety may be potential candidates to interpret the difference in response to ammonium. In addition, the difference of root phenotype may contribute the difference in response to ammonium though we did not found extremely different change by eyes. We did identify several genes, which were related to root morphology, from the DEGs list such as the c119942.graph_c3 (Germin-like protein in roots, auxin, up-regulated), c126564.graph_c2 (transcription factor, a gibberellin regulated protein, selected in this article), c108112.graph_c0 (root cap, up-regulated).

The analysis of amino acid content revealed a higher N assimilation into amino acids in the leaves of HJ variety compared to FD after N-fertilizer input (Table 3). This was consistent with the significantly upregulated expression patterns of N uptake genes AMT, AQP and NRT in leaves, suggesting that these genes play import roles in N use efficiency. Previously study showed that the NH4 + uptaken is then assimilated into Gln by glutamine synthetase gene GS through Gln-Glu metabolizing cycles (Fig. 6) in roots, and then transported to leaves51, 52. The GS expression can be induced by the increased ammonium53 and that is consistent in our study. Our finding revealed that a strong positive correlation of GS gene expression with Glu level was in leaves. This suggested that GS expression in leaves plays major role in controlling dynamic level of Glu in leaves. We found that GOGAT expression was negatively correlated with the expression of NRT, AQP and three common DEG in leaves with ammonium supply. This may be a feedback repression of high NH4 + amount on the expression of GOGAT which also functions as to release NH4 + from Gln. Taken together, low expression of GOGAT and the higher expression of AMT, AQP, NRT and GS work together to promoting the NH4 + uptake and assimilation into amino acids. The higher expression levels of AMT and GS genes in HJ compared to FD (Fig. 4) suggested a higher capability of ammonium uptake and higher N assimilation in HJ than FD. The Glu content in the HJ variety increased while FD displayed a downward trend after N fertilizer treatment (Table 3). This result could be explained as a balance between Glu generation and its use as a substrate in other metabolism pathways, such as the theanine synthesis pathway53. Therefore, theanine and Glu content are regulated by both N transporter genes and additional genes, such as GS and GOGAT.

Conclusion

Our study revealed that many DEGs control N usage efficiency in the tea plant Camellia sinensis for active N resources in the soil. The two C. sinensis varieties with different NUEs result from different and four shared genes’ expression in the roots and leaves. The AMT, AQP, NRT, GOGAT and GS genes are the key shared DEGs acting together to regulate ammonium uptake and assimilation. Some of the genes are directly correlated with N use in tea leaves. Future research on the role of the identified three novel common DEG N-responsive genes will be the first priority in elucidating the mechanism of high N use efficiency in plants. The study improved the understanding of the molecular regulations of NUE, and provided direct gene references for engineering and guiding the breeding selection of high nitrogen-efficient varieties of C. sinensis.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Cuttings from two Camellia tea varieties, HJ and FD, were propagated for new tea plants and grown to tea industrial size over 3 years. All of the plants were grown in the same experimental field at GPS coordinates 113°4′30.168″E and 28°12′20.580″N, and under the same conditions at the Hunan Tea Research Institute, in Changsha, China. HJ is much higher tea plant than FD. As the leaves and bud are considered, tea plant HJ has a much faster growing speed than FD.

Ammonium treatment

Four propagated plants of each variety were treated with 22 g of (NH4)2SO4 (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent co., LTD, cat# 10002918, Shanghai, China) per 14.5 kg of dry soil, a commonly used range during farming, and four plants were used as experimental controls without (NH4)2SO4 treatment22. The available nitrogen amount in this soil used is 94.7 mg per kg dry weight. The treatment was conducted at the stage when the bud was 1–2 mm long and no new spread leaf was present at the top of a branch, two weeks after this point (in April 2014), the bud would spread into a new leaf. Leaves and roots were collected separately on the 15th day after treatment. Leaf samples included the bud, the 1st leaf and the 2nd leaf positioned from the top to bottom, and young absorbing roots such as the latest and the second latest lateral roots were sampled (Fig. 1). Tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until processing. Two repeated experiments were performed. The relative water content in the growing soil was 50–70%.

RNA extraction and sequencing

Samples from the two repeats were pooled and ground into powder in a mortar using liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted from 80–120 mg of powder using a TIANGEN RNAprep Pure kit (TIANGEN, catalog # DP441) with our optimized procedures (pending patent CN104694531 A). The quality and quantity of total RNA were characterized on a 1% agarose gel and examined with a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). The RNA integrity number (RIN) was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Santa Clara, CA, USA). If the RIN was greater than 8.0, the RNA was used for subsequent Illumina library preparation.

mRNA was enriched from 15 μg of total RNA using an NEBNext poly (A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (NEB, cat# E7490L) and AMPure® XP Beads (Beckman Coulter, Inc., cat# A63881). mRNA was cleaved into short fragments in buffer and was then indexed. The sequencing library was prepared using an NEBNext mRNA Library Prep Master Mix Set for Illumina (NEB, cat# E6110L) and NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (NEB, cat# E7500). The library was then subjected to qPCR-based quantification using a Quantification Kit-Illumina GA Universal (Kapa, cat# KK4824). Paired-end 125-bp sequencing was performed for the qualified library on a HiSeq 2500 machine.

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) assay

1–2 μg total RNAs were used for reverse transcription by FastQuant RT kit (TIANGEN, catalog # KR106). 1 μL RT product was used as template in the subsequent step. The cDNA was diluted to 200 ng/μL was used for the qPCR with SuperReal PreMix Plus (TIANGEN, catalog # FP205) on the Bio-Rad CFX96 realtime system. Three technical replicates were applied for the relative gene expression analysis. Reactions were performed at 95 °C for 15 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, and 60 °C for 32 s. β-actin was used as reference for qPCR data analysis. All primers for RT-qPCR are listed in Table S5.

Transcript assembly, annotation and expression analysis

Raw reads generated from the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform were preprocessed to a clean adaptor sequence. Reads with >5% unknown bases were filtered out, and low-quality reads (>20% of the bases with a quality score of 10) were removed. The remaining reads, called clean reads, from the same variety were combined and de novo assembled using Trinity software (version 201308)54 to construct transcripts. Clean reads were mapped back to check the transcript quality, and poorly supported transcripts were filtered out as previously described54. Unigenes were defined as the longest sequence in the assembly cluster called a component in Trinity54. Unigenes were then searched using BLAST with an E-value threshold of E-5 against the NR (NCBI non-redundant protein sequences), Swiss-Prot, GO (Gene Ontology), COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups), KOG (euKaryotic Orthologous Groups), and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) databases, and against the Pfam database by HMMER with an E-value of 1E-10. The RNA-seq reads and the assembly are publicly available at NCBI under the master accession number SRP077092.

Amino acid detection and measurement

The leaf samples were fixed with boiling water steam for 90 sec, dried at 60 °C and then ground into a fine powder. In total, 5.0 g of powder was boiled in 100 ml of water for 15 min to extract amino acids, and the supernatant was then filtered through absorbent cotton. Two additional runs of extractions from the residue of the same powder were performed in 100 ml and 50 ml water. All of the extracted filtrate was merged and cooled to room temperature. The merged filtrate was then filtered through a 0.45-μm membrane, and the filtered liquid was collected for free amino acid detection using an amino acid analyzer (Hitachi, L-8800, Japan) according to the method described in China National Stand GB/T 5009.124-2003.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Meng Li at Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for his consultation in part of the bioinformatics analysis. Project supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (Grant No.2016JJ2074), the Innovation Team of the Hunan Academy of Agricultural Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and the Kunming Institute of Botany.

Author Contributions

X.W. and S.L. designed the study. F.X. and W.L. prepared the experiments. W.L., M.Z. and F.X. conducted the experiments. F.X. and W.L. provided the photos for the experiments. F.X., L.Z. and H.L. revised part of the paper. X.W. and W.L. analyzed the data. W.L. and X.W. prepared the manuscript. W.L., S.L. and X.W. participated in the discussion.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Wei Li and Fen Xiang contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01949-0

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Saijun Li, Email: hnhjhlsj@126.com.

Xuewen Wang, Email: wangxuewen@mail.kib.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Esteban R, Ariz I, Cruz C, Moran JF. Review: Mechanisms of ammonium toxicity and the quest for tolerance. Plant Science. 2016;248:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulvaney RL, Khan SA, Ellsworth TR. Synthetic nitrogen fertilizers deplete soil nitrogen: a global dilemma for sustainable cereal production. Journal of environmental quality. 2009;38:2295–2314. doi: 10.2134/jeq2008.0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutton MA, et al. Too much of a good thing. Nature. 2011;472:159–161. doi: 10.1038/472159a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAllister CH, Beatty PH, Good AG. Engineering nitrogen use efficient crop plants: the current status. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2012;10:1011–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2012.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludewig U, Neuhauser B, Dynowski M. Molecular mechanisms of ammonium transport and accumulation in plants. Febs Letters. 2007;581:2301–2308. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loque D, von Wiren N. Regulatory levels for the transport of ammonium in plant roots. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2004;55:1293–1305. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coskun D, Britto DT, Li M, Becker A, Kronzucker HJ. Rapid ammonia gas transport accounts for futile transmembrane cycling under NH3/NH4+ toxicity in plant roots. Plant Physiology. 2013;163:1859–1867. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.225961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang M, et al. The Interactions of aquaporins and mineral nutrients in higher plants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016;17:1229. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamoto MV, John J, Glass Anthony DM. Regulation of NRT1 and NRT2 gene families of Arabidopsis thaliana: responses to nitrate provision. Plant & Cell Physiology. 2003;44:304–317. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan L, et al. The organization of high-affinity ammonium uptake in Arabidopsis roots depends on the spatial arrangement and biochemical properties of AMT1-type transporters. The Plant Cell. 2007;19:2636–2652. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gansel X, Muños S, Tillard P, Gojon A. Differential regulation of the NO3− and NH4+ transporter genes AtNrt2.1 and AtAmt1.1. Arabidopsis: relation with long-distance and local controls by N status of the plant. The Plant Journal. 2001;26:143–155. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camanes G, Bellmunt E, Javier GA, Pilar GA, Cerezo M. Reciprocal regulation between AtNRT2.1 and AtAMT1.1 expression and the kinetics of NH4+ and NO3- influxes. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2012;169:268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kronzucker HJ, Siddiqi MY, Glass ADM, Kirk GJD. Nitrate-ammonium synergism in rice. a subcellular flux analysis. Plant Physiology. 1999;119:1041–1046. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.3.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glass AD, et al. The regulation of nitrate and ammonium transport systems in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2002;53:855–864. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.370.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruan L, et al. Characteristics of NH4+ and NO3− fluxes in tea (Camellia sinensis) roots measured by scanning ion-selective electrode technique. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:38370. doi: 10.1038/srep38370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hacke UG, et al. Influence of nitrogen fertilization on xylem traits and aquaporin expression in stems of hybrid poplar. Tree physiology. 2010;30:1016–1025. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpq058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishikawa-Sakurai J, Hayashi H, Murai-Hatano M. Nitrogen availability affects hydraulic conductivity of rice roots, possibly through changes in aquaporin gene expression. Plant and Soil. 2014;379:289–300. doi: 10.1007/s11104-014-2070-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pavlíková D, Neuberg M, ŽIžKová E, Motyka V, Pavlík M. Interactions between nitrogen nutrition and phytohormone levels in Festulolium plants. Plant Soil & Environment. 2012;58:367–372. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Y, Yang W, Wei J, Yoon H, An G. Transcription factor OsDOF18 controls ammonium uptake by inducing ammonium transporters in rice roots. Mol Cells. 2017;40:178–185. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2017.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novoa R, Loomis RS. Nitrogen and plant production. Plant & Soil. 1981;58:177–204. doi: 10.1007/BF02180053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CF, Lin JY. Estimating the gross budget of applied nitrogen and phosphorus in tea plantations. Sustainable Environment Research. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang YY, Li XH, Ratcliffe RG, Ruan JY. Characterization of ammonium and nitrate uptake and assimilation in roots of tea plants. Russian Journal of Plant Physiology. 2013;60:91–99. doi: 10.1134/S1021443712060180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruan J, Gerendás J, Härdter R, Sattelmacher B. Effect of nitrogen form and root-zone pH on growth and nitrogen uptake of tea (Camellia sinensis) plants. Annals of Botany. 2007;99:301–310. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcl258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruan J, Gerendás J, Härdter R, Sattelmacher B. Effect of root zone pH and form and concentration of nitrogen on accumulation of quality-related components in green tea. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2007;87:1505–1516. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rawat SR, Silim SN, Kronzucker HJ, Siddiqi MY, Glass AD. AtAMT1 gene expression and NH4+ uptake in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana: evidence for regulation by root glutamine levels. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology. 1999;19:143–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng WW, Ogita S, Ashihara H. Biosynthesis of theanine (γ-ethylamino-l-glutamic acid) in seedlings of Camellia sinensis. Phytochemistry Letters. 2008;1:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2008.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li P, Wan XC, Zhang ZZ, Li J, Shen ZJ. A novel assay method for theanine synthetase activity by capillary electrophoresis. Journal of Chromatography B-Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences. 2005;819:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang XS, et al. The breeding of early budding, high amino acid content and high quality new green-tea cultivar Baojing Huangjincha 1. Tea Communication. 2012;39:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu SF, et al. Ptr-miR397a is a negative regulator of laccase genes affecting lignin content in Populus trichocarpa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:10848–10853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308936110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, Bennetzen JL. Current status and prospects for the study of Nicotiana genomics, genetics, and nicotine biosynthesis genes. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2015;290:11–21. doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-0989-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gegas VC, et al. A genetic framework for grain size and shape variation in wheat. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1046–1056. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.074153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li AL, et al. mRNA and small RNA transcriptomes reveal insights into dynamic homoeolog regulation of allopolyploid heterosis in nascent hexaploid wheat. The Plant Cell. 2014;26:1878–1900. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.124388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi CY, et al. Deep sequencing of the Camellia sinensis transcriptome revealed candidate genes for major metabolic pathways of tea-specific compounds. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:131. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang XC, et al. Global transcriptome profiles of Camellia sinensis during cold acclimation. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:415–415. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu QJ, Chen ZD, Sun WJ, Deng TT, Chen MJ. De novo sequencing of the leaf transcriptome reveals complex light-responsive regulatory networks. Camellia sinensis cv. Baijiguan. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2016;7:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang WD, et al. Transcriptomic analysis reveals the molecular mechanisms of drought-stress-induced decreases in Camellia sinensis leaf quality. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2016;7:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu SC, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of tea plant responding to drought stress and recovery. PLos One. 2016;11:1–21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grabherr MG, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li CF, et al. Global transcriptome and gene regulation network for secondary metabolite biosynthesis of tea plant (Camellia sinensis) BMC Genomics. 2015;16:1–21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-16-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tai YL, et al. Transcriptomic and phytochemical analysis of the biosynthesis of characteristic constituents in tea (Camellia sinensis) compared with oil tea (Camellia oleifera) BMC Plant Biology. 2015;15:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0574-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y, et al. Identification and characterization of cold-responsive microRNAs in tea plant (Camellia sinensis) and their targets using high-throughput sequencing and degradome analysis. BMC Plant Biology. 2014;14:1–18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lima JE, Kojima S, Takahashi H, von Wiren N. Ammonium triggers lateral root branching in Arabidopsis in an ammonium transporter 1;3-dependent manner. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3621–3633. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.076216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogato A, et al. Characterization of a developmental root response caused by external ammonium supply in Lotus japonicus. Plant Physiology. 2010;154:784–795. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.160309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsay YF, Schroeder JI, Feldmann KA, Crawford NM. The herbicide sensitivity gene CHL1 of Arabidopsis encodes a nitrate-inducible nitrate transporter. Cell. 1993;72:705–713. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90399-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krouk G, et al. Nitrate-regulated auxin transport by NRT1.1 defines a mechanism for nutrient sensing in plants. Developmental Cell. 2010;18:927–937. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang R, Guegler K, Labrie ST, Crawford NM. Genomic analysis of a nutrient response in Arabidopsis reveals diverse expression patterns and novel metabolic and potential regulatory genes induced by nitrate. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1491–1509. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.8.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirscht A, et al. Crystal structure of an ammonia-permeable aquaporin. PLos Biology. 2016;14:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dynowski M, Mayer M, Moran O, Ludewig U. Molecular determinants of ammonia and urea conductance in plant aquaporin homologs. FEBS Letters. 2008;582:2458–2462. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jahn TP, et al. Aquaporin homologues in plants and mammals transport ammonia. FEBS Letters. 2004;574:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurai T, et al. Introduction of the ZmDof1 gene into rice enhances carbon and nitrogen assimilation under low-nitrogen conditions. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2011;9:826–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kokyo O, Kato T, Huilian X. Transport of nitrogen assimilation in xylem vessels of green tea plants fed with NH4+-N and NO3−-N. Pedosphere. 2008;18:222–226. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(08)60010-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rana NK, Mohanpuria P, Kumar V, Yadav SK. A CsGS is regulated at transcriptional level during developmental stages and nitrogen utilization in Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze. Molecular Biology Reports. 2010;37:703–710. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9559-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wan, X. C. & Xia, T. Secondary Metabolism of tea Plant (Science Press, 2015).

- 54.Haas BJ, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature Protocols. 2013;8:1494–1512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.