Abstract

Dopamine is a catecholamine that acts both as a neurotransmitter and as a hormone, exerting its functions via dopamine (DA) receptors that are present in a broad variety of organs and cells throughout the body. In the circulation, DA is primarily stored in and transported by blood platelets. Recently, the important contribution of DA in the regulation of angiogenesis has been recognized. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that DA inhibits angiogenesis through activation of the DA receptor type 2. Overproduction of catecholamines is the biochemical hallmark of pheochromocytoma (PCC) and paraganglioma (PGL). The increased production of DA has been shown to be an independent predictor of malignancy in these tumors. The precise relationship underlying the association between DA production and PCC and PGL behavior needs further clarification. Herein, we review the biochemical and physiologic aspects of DA with a focus on its relations with VEGF and hypoxia inducible factor related angiogenesis pathways, with special emphasis on DA producing PCC and PGL.—Osinga, T. E., Links, T. P., Dullaart, R. P. F., Pacak, K., van der Horst-Schrivers, A. N. A., Kerstens, M. N., Kema, I. P. Emerging role of dopamine in neovascularization of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma.

Keywords: angiogenesis, hypoxia-inducible factor, VEGF

Pheochromocytoma (PCC) and paraganglioma (PGL) are rare neuroendocrine tumors derived from chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla and paraganglia, respectively (1). PCC and PGL can be diagnosed by the demonstration of their increased catecholamine production, preferentially by measurement of their free or unconjugated O-methylated metabolites [i.e., metanephrine, normetanephrine, and 3-methoxytyramine (3-MT)] in plasma or urine. Until recently, the biochemical diagnosis of PCC and PGL was based mainly on demonstrating overproduction of norepinephrine (NE) or epinephrine or their respective metabolites, with no special interest in DA. As early as 1956, it was shown that increased synthesis of DA is associated with the malignant behavior of both tumors (2). The relevance of these early observations was only recently substantiated by the finding of a strong association between increased tumor DA production and germline mutations of the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) subunit B (SDHB) gene in malignant PGLs (3–5).

In 1957, Arvid Carlsson (6) demonstrated that DA is a neurotransmitter in the brain, and not merely a precursor for NE, as had been assumed earlier. Subsequently, it became evident that DA has widespread effects in the human body (Table 1). More recent studies showed major effects of DA on inhibiting angiogenesis and (tumor) neovascularization. These insights shed new light on DA metabolism in relation to tumor angiogenesis and potentially constitute important new targets for treatment (7–9). However, the precise relationship underlying the association between DA production and PCC and PGL behavior needs further clarification. In this review, we discuss the roles of DA with special focus on its relations with VEGF and HIF-related angiogenesis pathways, with particular emphasis on DA production by PCC/PGL.

TABLE 1.

Overview of DA synthesis, storage, secretion and function in various tissues of the body

| Tissues | Synthesis | Storage | Secretion | Target organ/ cell | Receptor type | Function | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central nervous system | ||||||||

| Brain | X | X | X | X | D1- and D2-like family DAT | Cognition, motor control, emotion, pain perception, sexual behavior, food intake and reward systems | 11, 12, 39, 139 | |

| Hypothalamus and pituitary gland | X | D2, D4, DAT | Inhibition of prolactin secretion | 92, 140 | ||||

| Peripheral tissues | ||||||||

| Adrenal gland | ||||||||

| Medulla | X | X | X | X | D1- and D2-like family | D1-like: stimulation of E and NE release; D2-like: inhibition of E and NE release | 39 | |

| Cortex | X | D1- and D2-like family | D1-like: unknown; D2-like: inhibition of aldosterone secretion | 39 | ||||

| APUD cells | ||||||||

| Retina | X | D1 and D4, DAT | Light-adaptive retinal processes | 18, 39 | ||||

| Heart | X | X | D4 | Unknown | 39 | |||

| Exocrine pancreas | X | X | X | X | D5 and DAT | Possible protection of gastric and intestinal mucosa against injury | 141 | |

| Endocrine pancreas | Xa | X | X | X | D1- and D2-like family, DAT | Inhibition of insulin secretion from β-cells | 141, 142 | |

| Blood vessels | X | D1- and D2-like family | Inhibition of NE release, vasodilatation | 39 | ||||

| Gastrointestinal tract | X | X | D1- and D2-like family, DAT | Stomach: relaxation, delayed emptying; colon: relaxation, stimulatory effect on sigmoid | 20, 92, 143, 144 | |||

| Kidney | X | X | D1- and D2-like family, DAT | D1-like: stimulate secretion of renin. D2-like: renal vasodilatation, diuresis, and natriuresis | 39, 92, 145, 146 | |||

| Endothelial cells | X | X | X | D2, D3 and D4 | Inhibiting VEGF-2 receptor phosphorylation | 73, 147 | ||

| Peripheral nervous system | ||||||||

| Sympathetic ganglia | X | X | X | X | D2-like family and DAT | Inhibition of NE release | 39 | |

| Bone marrow | ||||||||

| EPCs | X | D2 | Unknown | 148, 149 | ||||

| Blood cells | ||||||||

| Platelets | X | DAT (passive diffusion) | Transport of DA throughout the body; Inhibiting histamine induced vWF secretion | 150–152 | ||||

| Innate immune system | ||||||||

| Monocytic-dendritic cells | X | X | D1- and D2-like family | Releases DA on interaction with naive CD4+ T cells | 153, 154 | |||

| Neutrophils | X | X | D1 and D2 | Phagocytic inhibition, inhibition of TNF-α | 153, 154 | |||

| NK cells | X | D1- and D2-like family, DAT | D1-like: enhance NK cell cytotoxicity; D2-like: attenuate NK cell cytotoxicity | 153–157 | ||||

| Adaptive immune system | ||||||||

| T lymphocytes | X | X | D1- and D2-like family, DAT | D1-like: reduce IFN-γ production; D2-like: attenuate lymphocyte proliferation, reduce IFN-γ and IL-4 production, resulting in differentiation of naive Th0- to Th2-cells | 150, 153–157 | |||

| B lymphocytes | X | X | D2, D3 and D5 | Influences IgM and IgG secretion | 153, 158, 159 | |||

Most of the results described in this table are extracted from in vivo and in vitro studies. The D1-like family includes D1 and D5 DA receptors; the D2-like family includes D2, D3 and D4 DA receptors. aSynthesis inside the β cells.

PHYSIOLOGY OF DOPAMINE

Physiologic functions of DA

DA synthesis and storage take place in a variety of organs (Table 1). In the brain, DA is involved in several processes, such as cognition, motion control, emotion, pain perception, sexual behavior, food intake, and rewarding processes (10–12). DA does not cross the blood–brain barrier, keeping dopaminergic signaling in the brain functionally separated from peripheral DA actions (13). Peripheral DA-secreting tissues can be categorized into 2 groups according to the pathway of DA biosynthesis. The first group includes tissues such as the adrenal medulla and peripheral sympathetic nerves that take up tyrosine. The second group consists of cell systems that actively take up l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (l-DOPA) which is then decarboxylated to DA inside the cell (Fig. 1) (11, 14, 15). Cells that take up l-DOPA were previously designated amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation (APUD) cells (14).

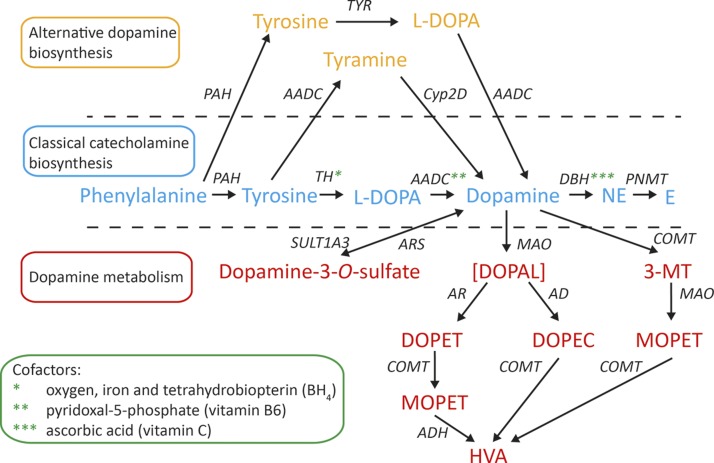

Figure 1.

Biosynthesis and metabolism of DA. DA is deaminated by MAO to DOPAL, which is metabolized to DOPAC by AD and to DOPET by AR. DOPET is metabolized by COMT to MOPET. DOPAC and MOPET are metabolized to HVA, the end product of DA metabolism. PAH, phenylalanine hydroxylase.

By binding to the different DA receptors that are present in a variety of organs, DA can elicit a broad range of physiologic effects. These are also summarized in Table 1.

DA synthesis

The primary precursor for the catecholamine biosynthesis is tyrosine, which is either absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract from protein-rich foods or formed after hydroxylation of the essential amino acid, phenylalanine (16, 17). The conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine occurs in the brain, liver, adrenal medulla, and peripheral sympathetic nerves (17). In the cytosol of catecholaminergic neurons and the adrenal medulla, tyrosine is converted to l-DOPA by the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH; EC 1.14.16.2) (Fig. 1). The hydroxylation of tyrosine by TH is the rate-limiting step in DA biosynthesis (18, 19). Conversion of l-DOPA to DA is catalyzed by the enzyme aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC; EC 4.1.1.28). Depending on the presence and activity of DA, β-hydroxylase (DBH; EC 1.14.17.1) and phenylethanolamine-N-methyltransferase (PNMT, EC 2.1.1.28), DA can be further converted to NE and epinephrine, respectively (18). The total amount of DA that is converted into NE is tissue-specific and varies between 50 and 90% (20). For example, in the heart and the sympathetic nerves, ∼90% of the DA located in storage vesicles is converted into NE (20, 21). In contrast, in the human omentum > 50% of the DA is metabolized to NE (20, 22). Cofactors in the DA synthesis pathway are molecular oxygen (O2), reduced iron (Fe2+), tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), and pyridoxal-5-phosphate (vitamin B6), as depicted in Figure 1 (23).

Apart from this classic biosynthetic pathway, there are 2 alternative pathways for DA synthesis that have been demonstrated by a series of in vivo experiments in animals. One is a cytochrome P450–mediated pathway that has been demonstrated in rats. In this pathway, decarboxylation precedes hydroxylation; thus, tyrosine is decarboxylated to tyramine by AADC, which is then hydroxylated to DA by cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) in the liver (Fig. 1) (24, 25). Another DA biosynthetic pathway involves tyrosinase (TYR; EC 1.14.18.1), a key enzyme in melanin biosynthesis, which also converts tyrosine to l-DOPA (26). In TH-knockout mice, TYR contributes to catecholamine biosynthesis in the brain and peripheral cells of the heart that normally synthesize catecholamines via TH (27). In addition, albino mice lacking both TYR and TH still appear to have some source of catecholamine secretion (27). It is not clear whether this residual DA is produced via the CYP2D6 pathway or by another unknown route. These pathways have not yet been investigated in humans but could be of interest (e.g., for patients with TH deficiency, a rare disorder resulting in cerebral catecholamine deficiency) (28).

Cellular DA transport

Dopamine storage and release

After its synthesis or reuptake, DA is transported from the cytosol into storage vesicles by vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT)-1 and -2 (Fig. 2). VMAT-1 is preferentially expressed in neuroendocrine cells, including chromaffin and enterochromaffin cells, whereas VMAT-2 is also found in cells of the central and peripheral nervous system (29). The driving force for vesicular monoamine transport is provided by an ATP-dependent vesicular membrane proton pump that maintains an H+-electrochemical gradient between cytoplasm and granule matrix. For DA to be transported into the vesicle by VMAT, an H+-electron is exchanged (30–32). Exercise may cause disruption of this gradient by hypoxia or ischemia, resulting in a rapid release of catecholamines from storage vesicles into the cytoplasm (30, 33). In patients with a PCC, plasma concentrations of epinephrine, NE, and DA are increased after an exercise test and are associated with reduced pH levels (34). In addition, postexercise levels of epinephrine and the epinephrine:DA ratio are elevated in patients with a PCC compared to healthy controls (33). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that an increased production of lactate is accompanied by a higher release of NE in the brain, and it has been suggested that combination contributes to the positive effects of exercise on well-being (35). Recently, an alternative pathway for brain NE release was described that involves lactate produced by astrocytes (35). It is not yet clear whether this effect is receptor mediated or a direct effect of a lactate-induced decrease in pH.

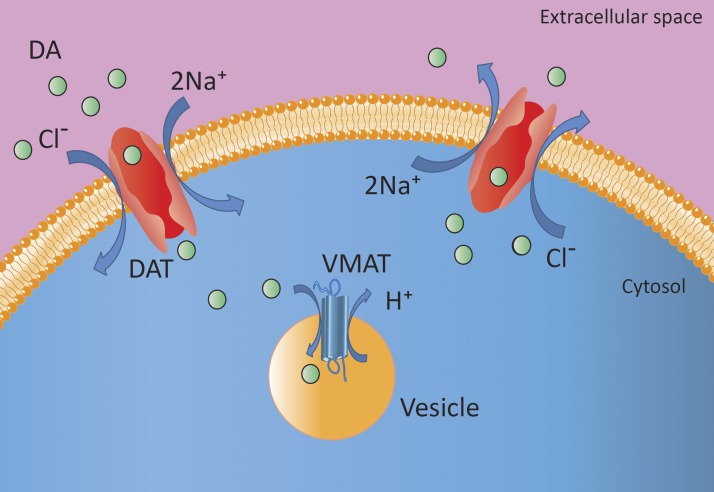

Figure 2.

Uptake and storage of DA from the extracellular milieu into the vesicle of neuronal and non-neuronal cells. The DAT transports DA into the neuronal or non-neuronal cell. In the cytoplasm, DA is taken up into storage vesicles via VMAT. It is presumed that, when DA binds to DAT, together with Na+ and Cl−, they promote a change in the conformation of DAT from a primarily outward-facing to a predominantly inward-facing transporter. In sympathetic nerves, DA can also be released by exocytosis (38).

Dopamine reuptake

Acting both as a neurotransmitter and a hormone, DA has autocrine and paracrine functions as well as endocrine and exocrine functions. Cellular uptake of DA is facilitated by the DA transporter (DAT) and is coupled to the NA+/K+-ATPase-dependent Na+ transport across the cell membrane (Fig. 2) (36). DAT function requires the sequential binding and cotransport of 2 Na+ ions and 1 Cl− ion (37). It can act as an outward-facing transporter oriented either toward the synaptic cleft or circulation thereby facilitating diffusion into the cell, or it can act as an inward-facing transporter, thus facilitating DA diffusion out of the cell (38). The primary function of DAT as an outward-facing transporter is to remove DA from the synaptic cleft or circulation, thereby terminating the actions of DA and recycling DA for reuse. Subsequently, DA enters storage vesicles through VMAT to remain available for exocytosis.

The number of outward-facing DATs is regulated by the amount of DA in the synaptic cleft or circulation. In cases of acutely elevated DA concentrations, DAT is recruited to the cell membrane (38). Continuous presence of DA desensitizes DAT activity by decreasing the number of DATs on the cell membrane. DAT activity is terminated through a process involving invagination of the transporter into membrane pits, which are subsequently internalized into endosomal vesicles (38).

Dopamine receptors

Cytoplasmic vesicles store DA until an action potential triggers its release through exocytosis. Tissue-specific response is mediated through specific DA receptors which are GPCRs expressed in various tissues and cells (Table 1). Five subtypes of DA receptors have been identified (D1–D5). These subtypes can be divided into 2 families: the D1-like family (D1 and D5) and the D2-like family (D2, D3, and D4) (39–41). D1-like receptors are coupled to Gαs proteins and stimulate adenylyl cyclase and the activity of PKA. In contrast, D2-like receptors are coupled to Gαi/o protein and inhibit both adenylyl cyclase and PKA (Fig. 3) (39). Initially, it was thought that monomers or homodimers of DA receptors were involved in the DA signal transduction pathway. It has been demonstrated, however, that there is a great diversity of signaling and functioning of DA receptors. D1- and D2-like receptors can form heterodimers resulting in the activation or inhibition of different signal transduction pathways. For example, the DA D1-D2 receptor heterodimer couples to Gαq which activates phospholipase C, resulting in production of inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). In turn, IP3 results in mobilization of intracellular calcium and DAG in the activation of PKC. In addition, DA receptors may heterodimerize with other receptors (e.g., for ghrelin or adenosine) or regulate G-protein independent signaling pathways (42).

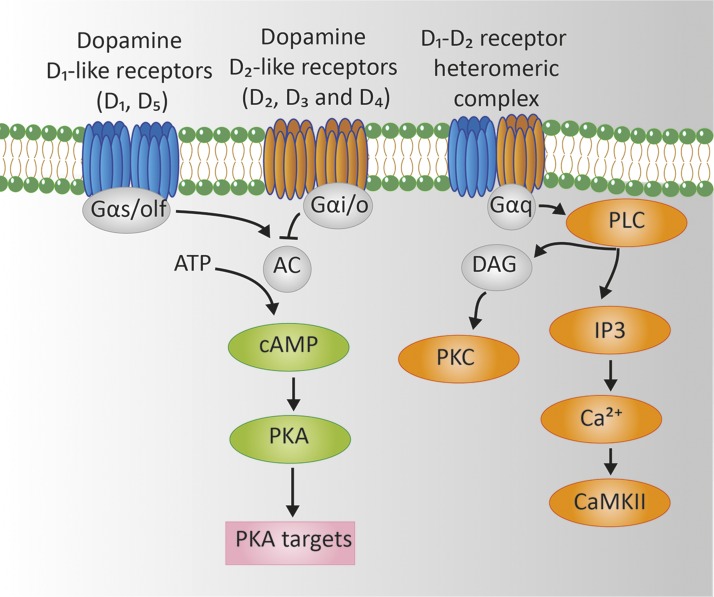

Figure 3.

Signaling networks regulated by DA in D1-like receptors, D2-like receptors and D1-D2 receptor heteromers. DA D1-like family and D2-like family receptor homodimers signal through Gαs/olf and Gαi/o protein to regulate cyclic AMP through adenylyl cyclase (AC) activity. D1-like receptors activate AC through Gαs/olf, thereby increasing intracellular cAMP and stimulating PKA. D2-like receptors inhibit AC though Gαi/o, thereby suppressing cAMP and inhibiting PKA. The DA D1-D2 receptor heterodimer signals through Gαq, phospholipase C, resulting in increased production of IP3 with mobilization of intracellular calcium and of DAG with subsequent activation of PKC (41, 42).

After exocytosis, DA is either retrieved through reuptake into the secreting cell by the DAT (Fig. 2), as discussed earlier, or is inactivated by one of the enzymes described in the next section.

Dopamine metabolism

There are 3 enzymes involved in the metabolism of DA: monoamine oxidase (MAO-A or -B; EC 1.4.3.4), catechol-O-methyltransferase (soluble or membrane bound COMT; EC 2.1.1.6), and sulfotransferase type 1A3 (SULT type 1A3; EC 2.8.2.1). MAO is located in sympathetic nerves and in the adrenal gland. COMT is mainly present in the brain and adrenal gland, whereas SULT type 1A3 is predominantly expressed in non-neuronal cells. MAO catalyzes the first step of a 2-step reaction (Fig. 1) (43). MAO-A preferentially oxidizes biogenic amines such as serotonin, NE, and epinephrine. DA is metabolized equally by MAO-A and -B (44), which convert DA to the acidic metabolites 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) or 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol (DOPET) via the unstable aldehyde intermediate metabolite 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL) (18, 19, 45). DA and DOPET lack a β-hydroxyl group in contrast to NE and epinephrine. The absence of the β-hydroxyl group favors oxidation by aldehyde dehydrogenase (AD). Therefore, DA is preferentially metabolized to DOPAC (18). The second step of the inactivation is the O-methylation of DOPAC to homovanillic acid (HVA) (Fig. 1). A substantial portion of HVA (35–50%) is excreted in urine. The remaining part is eliminated from the circulation by the liver (22, 46).

In contrast to sympathetic nerves, which contain only MAO, adrenal chromaffin cells contain both MAO and COMT (18). COMT in chromaffin cells is mainly present as the membrane-bound form, with a much higher affinity for catecholamines than the soluble form found in most other organs, such as the liver and kidneys. As a result, DA in the adrenal gland is first O-methylated by COMT to 3-MT (18, 45). Subsequently, 3-MT is further metabolized by MAO to HVA (Fig. 1).

In addition, DA may also be metabolized by what has been called a third catecholamine system (47). In this proposed system, DA, synthesized from decarboxylation of l-DOPA in non-neuronal cells such as gastrointestinal cells, could act locally as an autocrine-paracrine effector and could undergo inactivation by sulfoconjugation before entry into the bloodstream (47). DA and its metabolites are metabolized to sulfate conjugates by SULT1A3. The enzyme SULT1A3 has a particular high affinity for DA, and 3-MT and is found in high concentrations in the cytosol of gastrointestinal cells, which therefore represent a major source of sulfate conjugates (30). SULT1A3 can also be found in blood platelets, lungs, kidneys, and brain (47). Arylsulfatases (ARSs) located in the lysosome and in the endoplasmic reticulum can reverse the sulfation through hydrolysis of sulfate esters (48).

In general, sulfation is an inactivating mechanism and a means of detoxification of certain substances (48). Thus, sulfation of DA may be thought of as part of a gut–blood barrier by detoxifying catecholamines that enter the gastrointestinal lumen after ingestion of catecholamine-rich food products (e.g., fruits, tomatoes, nuts, potatoes, and beans) as well as endogenously produced DA (49). Theoretically, this system also functions as a buffering system, reversibly deactivating DA to DA-3-O-sulfate if DA concentrations are too high, and converting DA-3-O-sulfate back to DA if needed.

INTERACTION BETWEEN DA AND ANGIOGENESIS

Normal angiogenesis

Angiogenesis is an important adaptive process to guarantee a continuous supply of nutrients and disposal of waste products, such as during embryogenesis or repair of damaged blood vessels. In addition, angiogenesis is a vital process in preventing hypoxic situations, caused by exercise or impaired blood supply, for example. Angiogenesis is mediated by circulating HIFs (e.g., HIF-α and -β). There are 3 different HIF-α isoforms—HIF-1α, -2α, and -3α—with HIF-1α and -2α being most sensitive to oxygen tension, and 3 HIF-β isoforms: HIF-1β, -2β and -3β (50–52). Under normoxic conditions, HIF-α is rapidly degraded by the prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) proteins that promote the interaction with the von Hippel Lindau tumor suppressor protein (pVHL) with the E3 ligase complex (Fig. 4). This process leads to ubiquitination of HIF-α (52, 53). A second pathway of HIF-α inactivation is hydroxylation of an asparagine residue (Asn803) in the C-terminal transactivation domain of HIF-α by factor-inhibiting HIF-1 (FIH-1) (52–54).

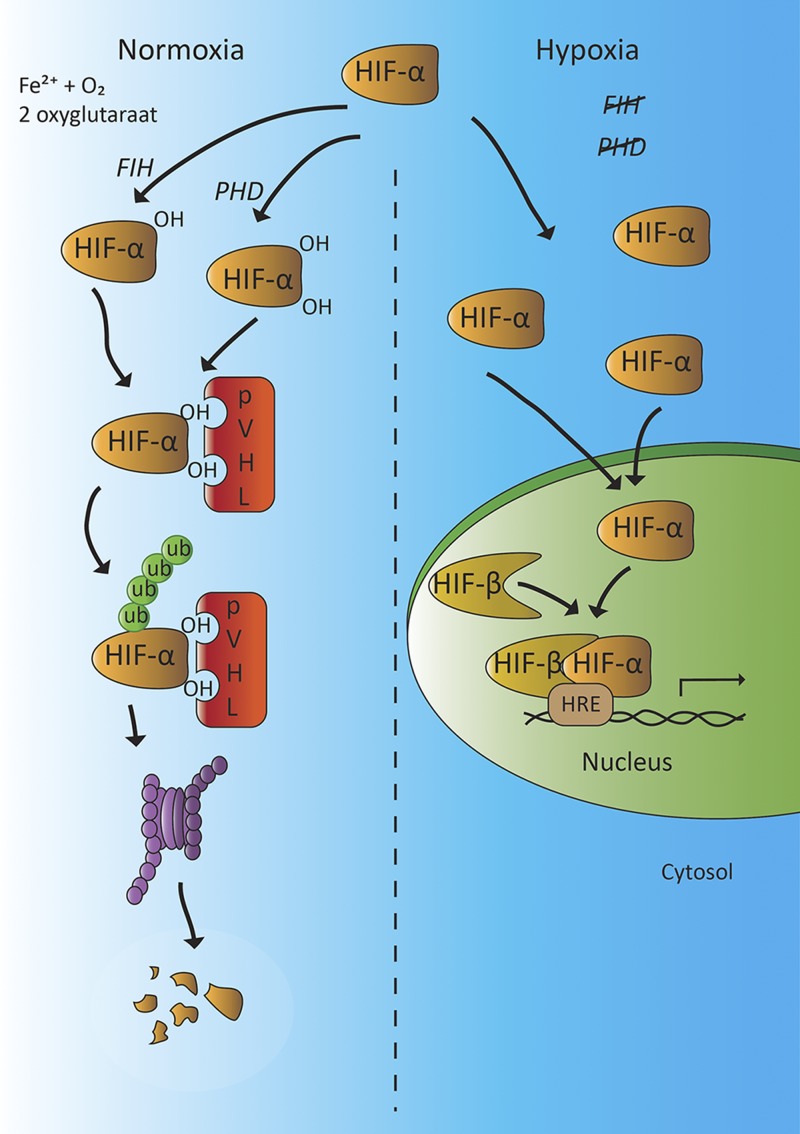

Figure 4.

Activity of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-α under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. When tissue oxygen concentration is normal, HIF-α is hydroxylated by the oxygen-sensitive PHD domain proteins or FIH-1, promoting the interaction with pVHL. This process targets HIF-α for ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, resulting in proteolytic degradation. When tissue oxygen concentration is low, the activities of PHD and FIH are reduced and degradation of HIF-α is impaired. The ensuing elevation of HIF-α levels allow the formation of an active transcription complex with HIF-β. This HIF-α/β complex binds to the HRE on the promoter region of certain genes of target cells (e.g., those encoding VEGF, VPF, and TH). In patients with a VHL gene mutation, the interaction between pVHL and hydroxylated HIF-α is disrupted, which reduces the ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of HIF-α and causes HIF-α accumulation, which mimics a hypoxic state (51–53).

In hypoxic conditions, HIF-α is stabilized and forms an active transcription factor complex with HIF-β in the nucleus of the cell (Fig. 4). This HIF complex (HIF-α/HIF-β heterodimer) binds in the nuclei of surrounding cells in a paracrine-autocrine manner to the promoter region of target genes, such as those encoding VEGF and vascular permeability factor (VPF). VEGF and VPF stimulate angiogenesis by binding to the VEGF-2 receptor on vascular endothelial tissue, which enhances microvascular permeability and endothelial proliferation and induces the proliferation and migration of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from the bone marrow to the site of action (55–58). These series of events contribute to the development of new blood vessels in response to hypoxia. In this process, DA acts as an important regulator by exerting negative feedback control through inhibition of VEGF.

DA, tumor angiogenesis, and tumor growth

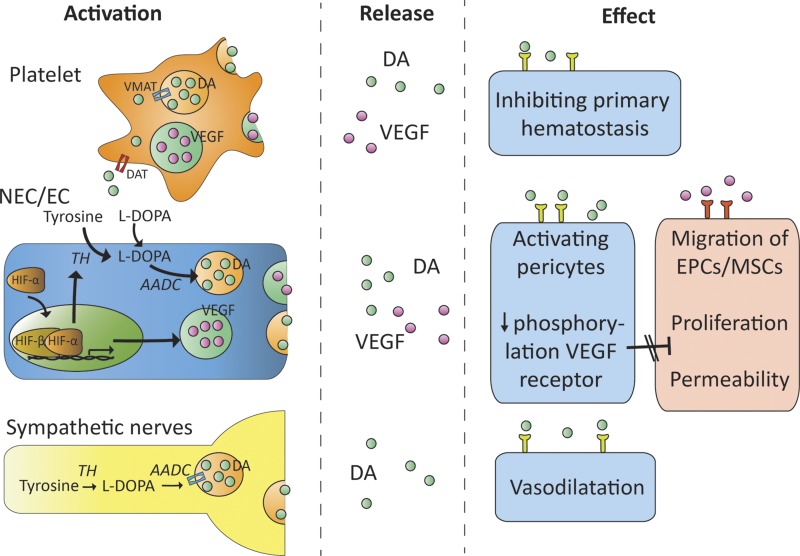

Activation of the DA D2 receptor inhibits the proangiogenic effects of VEGF and VPF by preventing phosphorylation of the VEGF-2 receptor (Fig. 5) (58, 59). In 1978, it was shown that administration of DA improved survival of B-16 melanoma mice compared with nontreated controls (60). In addition, tumor endothelial cells (ECs) collected from B-16 melanoma tumor-bearing mice with ablated peripheral dopaminergic nerves had strikingly more VEGF-2 receptor phosphorylation compared to B-16 tumor-bearing mice with intact peripheral dopaminergic nerves (61). Moreover, VEGF-2 receptor phosphorylation was found to be markedly upregulated in B-16 tumor ECs collected from DA D2-receptor knockout mice (58, 60).

Figure 5.

DA release and proposed actions of DA and VEGF in various tissues. DA and VEGF are released from activated platelets and neuroendocrine cells (NECs)/hypoxic ECs. DA can also be released by sympathetic nerves after excitation. DA inhibits the phosphorylation (i.e., activation) of the VEGF-2 receptor through activation of the D2 receptor. As a result, proliferation and migration of EPCs and MSCs from the bone marrow are inhibited (54–57).

An antiangiogenic effect of DA has also been suggested in preclinical models with human cancers. In vivo results with mice bearing ovarian cancer suggested that DA reduces chronic stress-mediated cancer growth in ovarian carcinoma (62). DA and TH were absent in both human and rat gastric cancer tissue, in contrast to normal human and rat stomach tissues (9). In addition, a low dose of DA significantly reduced tumor angiogenesis in human tumor ECs expressing DA D2 receptors by inhibiting VEGF-2 receptor phosphorylation. In line with this evidence, DA treatment of mice after xenotransplantation of human gastric cancer resulted in a 3-fold decrease in tumor diameter compared to that in nontreated mice (9). In vivo and in vitro experiments have shown that the DA D2-receptor agonist bromocriptine partially inhibited growth of human small-cell lung cancer (63, 64).

Recently, high expression of DA D2 receptors was demonstrated in CD133+ non–small-cell lung cancer cells, the activation of which significantly inhibited the proliferation and invasiveness of these cells in vitro (65). In addition, it was hypothesized that the expression of DA D1 en D2 receptors in small-cell lung cancer inhibited immune cell responses without affecting tumor growth (66).

Apart from the inhibitory effects of DA on tumor growth, it also increases the efficacy of anticancer drugs. Conceivably, the mechanism underlying this beneficial effect of DA may involve improvement of vessel morphology and function by acting on pericytes and ECs. Impaired blood flow in the tumor vascular bed caused by structurally and functionally abnormal blood vessels hinders the delivery of chemotherapeutic agents and also aggravates tumor hypoxia. DA acts through the D2 receptor present in these cells to up-regulate the expression of angiopoietin 1 in pericytes and the expression of the zinc finger transcriptional factor, Krüppel-like factor-2 (KLF2) in tumor ECs, resulting in significantly enhanced drug delivery of anticancer drugs to the vascular bed of the tumor (67). In addition, DA treatment significantly decreased vascular permeability and microvessel density in tumor tissue in preclinical models (68). These results were confirmed by in vivo studies showing that DA treatment increased vessel stabilization through activation of the D2 receptor in prostate and colon cancer–bearing mice (67). In vitro results have demonstrated that binding of DA to the D1 receptor enhances vessel stabilization by increasing pericyte migration to tumor ECs. Both DA and a DA D1 agonist increased platinum concentration in tumor xenografts after cisplatin administration (69). It has also been shown that DA treatment significantly improves the efficacy of commonly used anticancer drugs, such as doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil, in mice with human tumor-bearing colon cancer or breast cancer (68). Expression of DA D1 receptors was found in 30% of patients with primary breast carcinomas and was associated with larger tumors, higher tumor grades, node metastasis, and shorter patient survival. However, in vitro activation of the D1-receptor/cGMP/protein kinase G pathway suppressed cell viability, inhibited invasion and induced apoptosis (70). It seems counterintuitive that increased D1-receptor expression correlates positively with advanced disease, whereas D1-receptor activation results in apoptosis. The explanation for this observation is speculative.

Thus, administration of DA and dopaminergic drugs may decrease tumor growth by inhibiting angiogenesis through inhibition of VEGF-2 receptor phosphorylation and by improving the delivery of anticancer drugs at the site of the tumor.

DA and coagulation

In addition to the inhibiting actions of DA on hypoxia-driven angiogenesis, DA also exerts a certain degree of inhibition when angiogenesis is activated by the coagulation system. DA and VEGF are stored in dense granules and α-granules of circulating platelets (Fig. 4) (71, 72). After injury of a blood vessel, von Willebrand Factor (vWF) promotes platelet aggregation and platelet adhesion to the subendothelial tissue, resulting in the release of DA and VEGF. DA inhibits the histamine-induced vWF secretion by ECs, thereby inhibiting primary homeostasis (73). In concordance, treatment with DA D2-, D3-, and D4-receptor agonists inhibited histamine-induced vWF secretion (73). Furthermore, DA receptor antagonists are associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events (74).

Several studies have shown enhanced platelet activation in patients with cancer (75, 76). Tumor cells induce platelet activation and aggregation by direct cell–cell contact or by releasing platelet-stimulating factors, such as ADP, thrombin, and vWF. These factors form a bridge between tumor cells and platelets, upon which platelets become activated with release of several substances including DA and VEGF (75, 76).

DA SYNTHESIS AND HYPOXIA ARE LINKED IN PCC AND PGL

Paraganglia and adrenal medulla are dopaminergic, oxygen-sensitive organs

Sympathetic and parasympathetic paraganglia share the same embryological origin. Both derive from the neuronal plate, which later develops into the neural crest (77). Sympathetic paraganglia contain chromaffin cells, whereas parasympathetic paraganglia consist of glomus cells. The sympathetic and parasympathetic paraganglia as well as the adrenal medulla contain chief or type 1 cells and sustentacular cells, also called type 2 cells. Type 1 cells have neurosecretory granules with catecholamines that can be released upon stimulation (78). Type 1 cells are sensitive to the partial pressure of oxygen and release catecholamines in response to hypoxia. The stimulation of catecholamines by type 1 cells in response to hypoxia has been extensively studied in the carotid body. Hypoxia reduces conductance of the oxygen sensitive potassium channels in the cell membrane of type 1 cells (79). As a result, depolarization occurs which is followed by opening of voltage-gated calcium channels and enhanced calcium influx into the cell and neurotransmitter secretion by type 1 cells. The release of DA stimulates the respiratory center causing hyperventilation. Research in rabbit carotid bodies has shown that DA blocks the activity of calcium channels, thereby inhibiting further neurotransmitter release, making it part of an autocrine negative feedback loop (80). This mechanism of oxygen sensing based on the inhibition of membrane potassium channel activity has also been demonstrated in the adrenal medulla and PC12 cells (a cell line derived from PCC of rat adrenal medulla) (81, 82).

Hypoxia enhances the transcription of TH as well as the stability of TH mRNA, the key enzyme in catecholamine biosynthesis (81, 82). This effect of hypoxia is mediated by the HIF complex, which binds to the hypoxia-responsive element (HRE) in the proximal region of the TH promoter of PC12 cells (83, 84). Moreover, hypoxia was shown to induce HIF-mediated TH mRNA expression in rat mesencephalic cultures (85). Injection of desferrioxamine, an iron chelator that also induces the accumulation of HIF-1α, caused TH gene expression in rats (86). In addition, it has been found that neuronal precursor cells of HIF-1α-knockout mice showed less dopaminergic differentiation and a decrease in expression of dopaminergic marker molecules, such as TH and AD of 41 and 61%, respectively (87). Furthermore, in vivo results in chicken embryos showed that TH is also regulated by HIF-2α (88).These observations indicate that both HIF-1α and -2α could promote TH gene transcription and DA biosynthesis (81, 89). Transcription of the TH gene is indirectly also regulated by pVHL through its effects on the concentration of HIFs (83).

In addition to these in vitro and in vivo results, hypoxia-mediated catecholamine release has also been described in the human fetus (90, 91). Innervation of the adrenal medulla is immature or absent at birth (91). The hypoxia-mediated catecholamine release by adrenomedullary type 1 cells in the neonate plays a critical role in the ability to survive stressors occurring around delivery and the transition to extrauterine life (91). This mechanism is lost after birth, simultaneous with the maturation of the sympathetic nerves innervating the adrenal medulla (91).

The carotid bodies of rats living at high altitude were shown to contain TH and DA levels that were 6 and 43 times higher, respectively, than those in age-matched rats at sea level (92). In addition, the carotid bodies of these rats contained more chemosensitive cells and fibroblasts and more blood vessels (92). In humans, carotid body tumors were estimated to be ∼10 times more frequent in a population living at high altitudes than in a population at sea level due prolonged and severe hypoxia which caused hyperplasia of the chemoreceptor tissue (93). In summary, parasympathetic and sympathetic paraganglia are oxygen-sensitive organs, responding to hypoxia with the release of DA, which in turn stimulates the respiratory center.

PCC and PGL are highly associated with hypoxia

Currently, ∼35% of PCCs and PGLs are considered to be hereditary (94). PCCs can be part of other hereditary tumor syndromes, including multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 2, von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome, and von Recklinghausen’s disease, with mutations in RET, VHL, and neurofibromatosis (NF) genes, respectively (95). More recently, mutations of the genes for SDH subunit A, B, C, or D; SDH complex assembly factor 2 (SDHAF2) (96); transmembrane protein 127 (TMEM127) (97); Myc-associated factor X (MAX) (98); Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene (H-RAS) (99); Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene (K-RAS) (100); fumarate hydratase (FH) (101); kinesin family member 1B transcript variant β (KIF1BB) (102); isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) (103); PHD1 (104) and PHD2 (105, 106); and HIF-2A (107–109) have been identified as a possible cause of PCC and PGL. In recent years, detailed information has been gained on the pathophysiology of these mutations (110). Transcriptomic studies have identified 2 main molecular pathways that underlie development of these tumors: one in which the hypoxic pathway is activated [cluster 1; SDHx and SDHAF2 genes (cluster 1A) and VHL (cluster 1B)] and another in which the MAPK and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathways are activated (cluster 2: RET, NF1, TMEM127, and MAX) (94, 110–113).

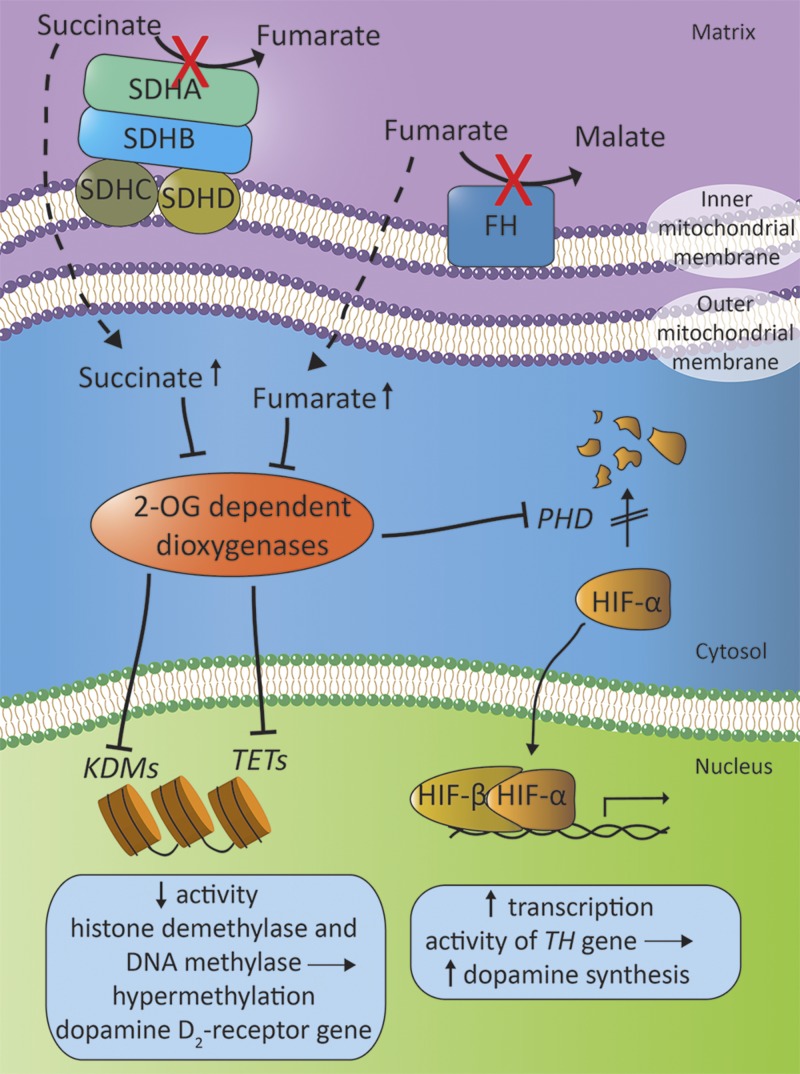

Cluster 1 mutations in PCC and PGL are associated with HIF-α stabilization and DA synthesis

Recently, a biochemical link between SDHx-related mutations and VHL has been found. In patients with a VHL gene mutation, the interaction between pVHL and hydroxylated HIF-α is disrupted, which reduces the ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of HIF-α (Fig. 4). This effect results in an accumulation of HIF-α, mimicking a hypoxic state (Fig. 6) (114, 115). The SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD genes encode for the 4 SDH subunits that, together, form mitochondrial complex II, which is bound to the inner mitochondrial membrane. SDHA and -B are the catalytic subunits and SDHC and -D are the anchor subunits. Complex II creates the link between the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Krebs cycle) and the mitochondrial electron transport chain. It catalyzes the conversion of succinate into fumarate and transfers the generated electrons to ubiquinone. A pathogenic SDHx mutation causes an enzyme deficiency, which results in an elevated intracellular concentration of succinate. Succinate directly inhibits the activity of 2-oxyglutarate-dependent dioxygenases such as PHD. As a result, a pseudohypoxic state is created that is related to decreased degradation of HIF-α.

Figure 6.

Proposed mechanism of the interplay between mitochondrial complex II and FH in the stabilization of the HIF-α signaling pathway. Mitochondrial complex II, located on the inner mitochondrial membrane, consists of SDH-proteins and catalyzes the conversion of succinate to fumarate. FH, another mitochondrial enzyme, converts succinate to malate. In the case of a mutation in one of the SDH subunits (SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, or SDHD gene mutations) or FH genes, the intracellular concentration of succinate and fumarate rise, resulting in inhibition of 2-oxyglutarate-dependent dioxygenases, including PHD, KDMs, and the TET enzymes, and leading to HIF-stimulated increase of transcription of the gene encoding TH, and to hypermethylation of the DA D2-receptor gene (81, 83, 89, 111, 115, 160).

FH is a mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of fumarate to malate as part of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Germline mutations in FH predispose to hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer, but have recently also been linked to PCC (116). A decrease in FH activity results in the accumulation of fumarate. Similar to succinate, fumarate is a competitive inhibitor of the 2-oxyglutarate-dependent dioxygenases and may thus lead to stabilization of HIF-α (117).

PCC and PGL and DA production

We recently documented the presence of catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes in parasympathetic head and neck PGL tissues (118). Elevated levels of 3-MT in plasma or urine have been found in 19–28% of patients with head and neck PGL (119–121). In addition, we have recently demonstrated a higher concentration of DA in platelets from patients with head and neck PGL, compared with healthy controls (122).

An increased plasma-free 3-MT was demonstrated in 72% percent of patients with an SDHB mutation and 67% of patients with an SDHD mutation (123). This increase in DA production may be explained by an enhanced TH gene transcription related to increased HIF-α activity. In the same study, only 17% of patients with VHL disease were found to have an elevated plasma-free 3-MT concentration, despite the fact that degradation of HIF-α was also decreased in these patients. It is unclear how the difference in plasma 3-MT concentration between SDHx and VHL-related PGL tumors can be explained.

Malignant PCCs and PGLs are associated with DA production

PCCs and PGLs are predominantly benign tumors, but malignancy may occur in up to 10% of all PCCs and PGLs (124). Malignancy is defined as local invasion or the presence of metastases of chromaffin tissue at sites where no chromaffin tissue is expected (1). In general, the risk of malignancy is higher in extra-adrenal tumors larger than 5 cm than in smaller intra-adrenal tumors (125, 126). Recent investigations show that the risk of malignant disease is particularly increased in tumors caused by an SDHB mutation (3, 126–128). Currently, there are no sufficiently reliable diagnostic markers for malignancy, but large tumor size, extra-adrenal tumor location, elevated plasma 3-MT concentration, and the presence of an SDHB mutation have been identified as independent risk factors (3–5). Thus, despite the suggestion of an increase in DA biosynthesis, patients with SDHB gene mutations are at risk for developing multiple and more malignant PGLs in the head and neck, thorax, and abdominal region (3, 126).

DA in malignant PCC/PGL

As previously described, DA inhibits angiogenesis in preclinical models. It was described that DA inhibits phosphorylation of the VEGF-receptor type and exerts several other antiproliferative effects. It was shown that malignant PCCs and PGLs give rise to increased plasma 3-MT concentrations. In the next section, we discuss several mechanisms by which tumors might adapt to the presence of DA.

Adaptation to high DA levels in carcinomas

Malignant tumors may still grow despite the local production of DA with its antitumoral effects, which is plausible, given that tumor growth is a process that is the result of deviations in several processes (129). It seems that tumors adapt to the effects of DA by reducing the DA concentration in tumors by limiting the perivascular innervations and by decreasing the number of DA receptor binding sites (7, 8). In malignant human stomach tissue, the presence of the DA D2 receptor has been confirmed, but the concentration of DA binding sites decreases compared to those in normal and benign tumor tissue (7). These results were confirmed in malignant human colon tissue (8). There is also evidence that tissues immediately adjacent to growing tumors lack perivascular innervations. In particular, nerves showing positive immunostaining for TH are absent (130). Normally, perivascular nerve fibers surrounding the interlobular blood vessels in human liver contain TH. In colorectal liver metastases, however, perivascular nerves are absent (130, 131). A similar loss of perivascular nerves has been observed in colorectal cancer (132). These observations suggest that the tumor itself may influence neural integrity in perivascular plexuses, perhaps by secretion of an inhibitory factor (132).

Adaptation to high DA levels in malignant PCC and PGL

The relationship of low DA content and DA receptor density with malignancy has been established in human stomach and colon tissue, but little is known about the pathophysiologic role of DA in the tumor behavior of PCC and PGL (7, 8, 133). PCC and PGL give rise to increased production of DA, and these tumors express DA D2-receptors, given that D2-receptor mRNA has been found in these tumors (134–136). The mean levels of D2-receptor mRNA are significantly higher in PCC than in PGL. D2-receptor mRNA levels seem to vary across the different hereditary tumor syndromes. D2-receptor mRNA levels are lowest in tumors from patients with a VHL mutation, intermediate in tumors from patients with an SDHx mutation, and highest in tumors from patients with MEN type 2 syndrome or those without a germline mutation. However, statistical significance was not reached because of the low number of cases (135). The increased succinate concentrations in SDHx-related PCC and PGL may cause DNA hypermethylation of the gene encoding the DA D2 receptor through inhibition of the histone lysine demethylases (KDMs) and the ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes, as has been shown in SDH-knockout mice (137, 138). It is currently unknown whether there is a decrease in DA receptor density or perivascular dopaminergic innervations in human PCC/PGL. Other mechanisms may be involved whereby malignant PCC and PGL escape from the antiproliferative effects of DA. It has been suggested that succinate acts as a competitive inhibitor of histone and DNA methylases and could thereby enhance the hypermethylation of the PNMT gene (112, 137). A reduced expression of PNMT could lead to a dedifferentiated catecholamine secretory profile, with predominant secretion of norepinehrine and DA. Together with the aforementioned upregulated of TH transcription, this explanation could be an additional one for the predominantly dopaminergic secretion that is frequently seen in these tumors. Future research is needed to further elucidate the possible pathophysiological role of DA in the development of PCC and PGL and to establish whether it is a determinant of malignant behavior in these neuroendocrine tumors.

Borcherding et al. (70) hypothesized several mechanisms to explain the counterintuitive positive correlation between DA signaling and malignant behavior observed in vitro in human breast cancer cells, such as changes in the role of the D1 receptor and the cGMP apoptotic pathway during tumor progression and metastatic stages of the disease. Mechanisms similar to these may also be applicable in malignant PCC and PGL. Future research is needed to further unravel this enigma.

CONCLUSIONS

DA has widespread effects throughout the human body. It is stored and secreted from many different organs and is part of a negative feedback loop for angiogenesis. It counteracts the actions of HIF-α and VEGF by blocking the phosphorylation of the VEGF-2 receptor. DA-mediated activation of the D2 receptor inhibits EC proliferation, vascularization, and tumor growth. Neoplasms may circumvent the actions of DA by reducing sympathetic nervous activity or by lowering the concentration of DA D2-receptor binding sites. Until now, little has been known about the role of DA in the development and progression of catecholamine secreting PCC and PGL. Although there is an increased DA synthesis and secretion in patients with SDHB- and SDHD-related PCC and PGL, the tumors are more often multifocal and behave more aggressively. SDHx-related gene mutations in PCC and PGL may be associated with a decreased concentration of D2-receptors, but further research is needed to further clarify the relationship between DA and tumorigenesis of PCC and PGL.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank B. Otterson (U.S. National Institutes of Health Library) and Dr. E. G. E. de Vries (University Medical Center Groningen) for providing comments on the manuscript. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- 3-MT

3-methoxytyramine

- AADC

aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase

- AD

aldehyde dehydrogenase

- APUD

amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation

- AR

aldehyde reductase

- ARS

arylsulfatases

- BH4

tetrahydrobiopterin

- COMT

catechol-O-methyltransferase

- CYP2D6

cytochrome P450 2D6

- DA

dopamine

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- DBH

dopamine β-hydroxylase

- DOPAC

3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid

- DOPAC

3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid

- DOPAL

3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde

- DOPET

3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol

- EC

endothelial cell

- EPC

endothelial progenitor cell

- FH

fumarate hydratase

- FIH

factor-inhibiting HIF

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- HRE

hypoxia-response element

- HVA

homovanillic acid

- IP3

inositol triphosphate

- KDM

histone lysine demethylase

- l-DOPA

l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine

- MAO

monoamine oxidase

- MEN

multiple endocrine neoplasia

- MOPET

4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenylethanol

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cell

- NE

norepinephrine

- NEC

neuroendocrine cell

- NF

neurofibromatosis

- PCC

pheochromocytoma

- PGL

paraganglioma

- PHD

prolyl hydroxylase

- PNMT

phenylethanolamine-N-methyltransferase

- pVHL

von Hippel Lindau tumor suppressor protein

- SDH

succinate dehydrogenase

- SDHAF2

succinate dehydrogenase complex assembly factor 2

- SULT

sulfotransferase

- TET

ten-eleven translocation

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- TMEM127

transmembrane protein 127

- TYR

tyrosinase

- VHL

von Hippel-Lindau

- VMAT

vesicular monoamine transporter

- VPF

vascular permeability factor

- vWF

von Willebrand Factor

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T. E. Osinga, T. P. Links, M. N. Kerstens, and I. P. Kema designed the figures; T. E. Osinga, T. P. Links, and I. P. Kema developed the concept and design of the review; and all authors participated in manuscript preparation, writing, and editing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lenders J. W. M., Eisenhofer G., Mannelli M., Pacak K. (2005) Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet 366, 665–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mcmillan M. (1956) Identification of hydroxytyramine in a chromaffin tumour. Lancet 268, 284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenhofer G., Lenders J. W. M., Siegert G., Bornstein S. R., Friberg P., Milosevic D., Mannelli M., Linehan W. M., Adams K., Timmers H. J. L. M., Pacak K. (2012) Plasma methoxytyramine: a novel biomarker of metastatic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma in relation to established risk factors of tumour size, location and SDHB mutation status. Eur. J. Cancer 48, 1739–1749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenhofer G., Tischler A. S., de Krijger R. R. (2012) Diagnostic tests and biomarkers for pheochromocytoma and extra-adrenal paraganglioma: from routine laboratory methods to disease stratification. Endocr. Pathol. 23, 4–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blank A., Schmitt A. M., Korpershoek E., van Nederveen F., Rudolph T., Weber N., Strebel R. T., de Krijger R., Komminoth P., Perren A. (2010) SDHB loss predicts malignancy in pheochromocytomas/sympathethic paragangliomas, but not through hypoxia signalling. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 17, 919–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlsson A. (1959) The occurrence, distribution and physiological role of catecholamines in the nervous system. Pharmacol. Rev. 11, 490–493 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basu S., Dasgupta P. S. (1997) Alteration of dopamine D2 receptors in human malignant stomach tissue. Dig. Dis. Sci. 42, 1260–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basu S., Dasgupta P. S. (1999) Decreased dopamine receptor expression and its second-messenger cAMP in malignant human colon tissue. Dig. Dis. Sci. 44, 916–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakroborty D., Sarkar C., Mitra R. B., Banerjee S., Dasgupta P. S., Basu S. (2004) Depleted dopamine in gastric cancer tissues: dopamine treatment retards growth of gastric cancer by inhibiting angiogenesis. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 4349–4356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salamone J. D., Correa M. (2012) The mysterious motivational functions of mesolimbic dopamine. Neuron 76, 470–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubí B., Maechler P. (2010) Minireview: new roles for peripheral dopamine on metabolic control and tumor growth: let’s seek the balance. Endocrinology 151, 5570–5581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schultz W. (2007) Multiple dopamine functions at different time courses. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30, 259–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pardridge W. M. (2007) Blood-brain barrier delivery. Drug Discov. Today 12, 54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearse A. G. E. (1969) The cytochemistry and ultrastructure of polypeptide hormone-producing cells of the APUD series and the embryologic, physiologic and pathologic implications of the concept. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 17, 303–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein D. S., Holmes C. (2008) Neuronal source of plasma dopamine. Clin. Chem. 54, 1864–1871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kopin I. J. (1964) Storage and metabolism of catecholamines: the role of monoamine oxidase. Pharmacol. Rev. 16, 179–191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagatsu T. (1973) Biochemistry of Catecholamines: The Biochemical Method, University Park Press, Baltimore, MD, USA [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenhofer G., Kopin I. J., Goldstein D. S. (2004) Catecholamine metabolism: a contemporary view with implications for physiology and medicine. Pharmacol. Rev. 56, 331–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson R. (1980) Tumours That Secrete Catecholamines: Their Detection and Clinical Chemistry, Wiley, Chichester, UK [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenhofer G., Aneman A., Friberg P., Hooper D., Fåndriks L., Lonroth H., Hunyady B., Mezey E. (1997) Substantial production of dopamine in the human gastrointestinal tract. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 82, 3864–3871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenhofer G., Esler M. D., Meredith I. T., Dart A., Cannon R. O. III, Quyyumi A. A., Lambert G., Chin J., Jennings G. L., Goldstein D. S. (1992) Sympathetic nervous function in human heart as assessed by cardiac spillovers of dihydroxyphenylglycol and norepinephrine. Circulation 85, 1775–1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisenhofer G., Åneman A., Hooper D., Holmes C., Goldstein D. S., Friberg P. (1995) Production and metabolism of dopamine and norepinephrine in mesenteric organs and liver of swine. Am. J. Physiol. 268, G641–G649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhar M. J., Minneman L., Muly E. C. (2006) Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects, Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiroi T., Imaoka S., Funae Y. (1998) Dopamine formation from tyramine by CYP2D6. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 249, 838–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bromek E., Haduch A., Gołembiowska K., Daniel W. A. (2011) Cytochrome P450 mediates dopamine formation in the brain in vivo. J. Neurochem. 118, 806–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sánchez-Ferrer A., Rodríguez-López J. N., García-Cánovas F., García-Carmona F. (1995) Tyrosinase: a comprehensive review of its mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1247, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rios M., Habecker B., Sasaoka T., Eisenhofer G., Tian H., Landis S., Chikaraishi D., Roffler-Tarlov S. (1999) Catecholamine synthesis is mediated by tyrosinase in the absence of tyrosine hydroxylase. J. Neurosci. 19, 3519–3526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willemsen M. A., Verbeek M. M., Kamsteeg E. J., de Rijk-van Andel J. F., Aeby A., Blau N., Burlina A., Donati M. A., Geurtz B., Grattan-Smith P. J., Haeussler M., Hoffmann G. F., Jung H., de Klerk J. B., van der Knaap M. S., Kok F., Leuzzi V., de Lonlay P., Megarbane A., Monaghan H., Renier W. O., Rondot P., Ryan M. M., Seeger J., Smeitink J. A., Steenbergen-Spanjers G. C., Wassmer E., Weschke B., Wijburg F. A., Wilcken B., Zafeiriou D. I., Wevers R. A. (2010) Tyrosine hydroxylase deficiency: a treatable disorder of brain catecholamine biosynthesis. Brain 133, 1810–1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wimalasena K. (2011) Vesicular monoamine transporters: structure-function, pharmacology, and medicinal chemistry. Med. Res. Rev. 31, 483–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pacak K., Lenders J. W. M., Eisenhofer G. (2007) Pheochromocytoma Diagnosis, Localization, and Treatment, Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA, USA [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schuldiner S., Shirvan A., Linial M. (1995) Vesicular neurotransmitter transporters: from bacteria to humans. Physiol. Rev. 75, 369–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parsons S. M. (2000) Transport mechanisms in acetylcholine and monoamine storage. FASEB J Exp. Biol. 14, 2423–2434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Telenius-Berg M., Adolfsson L., Berg B., Hamberger B., Nordenfelt I., Tibblin S., Welander G. (1987) Catecholamine release after physical exercise: a new provocative test for early diagnosis of pheochromocytoma in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. Acta Med. Scand. 222, 351–359 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Podolin D. A., Munger P. A., Mazzeo R. S. (1991) Plasma catecholamine and lactate response during graded exercise with varied glycogen conditions. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 71, 1427–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang F., Lane S., Korsak A., Paton J. F. R., Gourine A. V., Kasparov S., Teschemacher A. G. (2014) Lactate-mediated glia-neuronal signalling in the mammalian brain. Nat. Commun. 5, 3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torres G. E., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2003) Plasma membrane monoamine transporters: structure, regulation and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caron M. G., Gainetdinov R. R. (2010) Role of dopamine transporters in neuronal homeostasis. In Dopamine Handbook (Iversen L., Iversen S., Dunnett S., Bjorklund A., eds.), pp. 88–99, Oxford University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen R., Furman C. A., Gnegy M. E. (2010) Dopamine transporter trafficking: rapid response on demand. Future Neurol. 5, 123–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Missale C., Nash S. R., Robinson S. W., Jaber M., Caron M. G. (1998) Dopamine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 78, 189–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perreault M. L., Hasbi A., O’Dowd B. F., George S. R. (2014) Heteromeric dopamine receptor signaling complexes: emerging neurobiology and disease relevance. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 156–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beaulieu J. M., Gainetdinov R. R. (2011) The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 63, 182–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.George S. R., Kern A., Smith R. G., Franco R. (2014) Dopamine receptor heteromeric complexes and their emerging functions. Prog. Brain Res. 211, 183–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Molinoff P. B., Axelrod J. (1971) Biochemistry of catecholamines. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 40, 465–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Grimsby, J., Chen, K., Wang, L. J., Lan, N. C., and Shih, J. C. (1991) Human monoamine oxidase A and B genes exhibit identical exon-intron organization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 88, 3637–3641 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kopin I. J. (1985) Catecholamine metabolism: basic aspects and clinical significance. Pharmacol. Rev. 37, 333–364 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Änggård E., Lewander T., Sjöquist B. (1974) Determination of homovanillic acid turnover in man. Life Sci. 15, 111–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldstein D. S., Swoboda K. J., Miles J. M., Coppack S. W., Åneman A., Holmes C., Lamensdorf I., Eisenhofer G. (1999) Sources and physiological significance of plasma dopamine sulfate. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84, 2523–2531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coughtrie M. W. H., Sharp S., Maxwell K., Innes N. P. (1998) Biology and function of the reversible sulfation pathway catalysed by human sulfotransferases and sulfatases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 109, 3–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kema I. P., Schellings A. M., Meiborg G., Hoppenbrouwers C. J., Muskiet F. A. (1992) Influence of a serotonin- and dopamine-rich diet on platelet serotonin content and urinary excretion of biogenic amines and their metabolites. Clin. Chem. 38, 1730–1736 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keith B., Johnson R. S., Simon M. C. (2011) HIF1α and HIF2α: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 9–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaelin W. G. Jr., Ratcliffe P. J. (2008) Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol. Cell 30, 393–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaelin W. G. (2005) Proline hydroxylation and gene expression. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 115–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zimna A., Kurpisz M. (2015) Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in physiological and pathophysiological angiogenesis: applications and therapies. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 549412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Majmundar A. J., Wong W. J., Simon M. C. (2010) Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol. Cell 40, 294–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferrara N., Gerber H. P., LeCouter J. (2003) The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat. Med. 9, 669–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pradeep C. R., Sunila E. S., Kuttan G. (2005) Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF receptors in tumor angiogenesis and malignancies. Integr. Cancer Ther. 4, 315–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoffmann B. R., Wagner J. R., Prisco A. R., Janiak A., Greene A. S. (2013) Vascular endothelial growth factor-A signaling in bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells exposed to hypoxic stress. Physiol. Genomics 45, 1021–1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Basu S., Nagy J. A., Pal S., Vasile E., Eckelhoefer I. A., Bliss V. S., Manseau E. J., Dasgupta P. S., Dvorak H. F., Mukhopadhyay D. (2001) The neurotransmitter dopamine inhibits angiogenesis induced by vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor. Nat. Med. 7, 569–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sarkar C., Chakroborty D., Basu S. (2013) Neurotransmitters as regulators of tumor angiogenesis and immunity: the role of catecholamines. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 8, 7–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wick M. M. (1978) Dopamine: a novel antitumor agent active against B-16 melanoma in vivo. J. Invest. Dermatol. 71, 163–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Basu S., Sarkar C., Chakroborty D., Nagy J., Mitra R. B., Dasgupta P. S., Mukhopadhyay D. (2004) Ablation of peripheral dopaminergic nerves stimulates malignant tumor growth by inducing vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 64, 5551–5555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moreno-Smith M., Lu C., Shahzad M. M. K., Pena G. N., Allen J. K., Stone R. L., Mangala L. S., Han H. D., Kim H. S., Farley D., Berestein G. L., Cole S. W., Lutgendorf S. K., Sood A. K. (2011) Dopamine blocks stress-mediated ovarian carcinoma growth. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 3649–3659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ishibashi M., Fujisawa M., Furue H., Maeda Y., Fukayama M., Yamaji T. (1994) Inhibition of growth of human small cell lung cancer by bromocriptine. Cancer Res. 54, 3442–3446 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Senogles S. E. (2007) D2 dopamine receptor-mediated antiproliferation in a small cell lung cancer cell line, NCI-H69. Anticancer Drugs 18, 801–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roy S., Lu K., Nayak M. K., Bhuniya A., Ghosh T., Kundu S., Ghosh S., Baral R., Dasgupta P. S., Basu S. (2016) Activation of D2 dopamine receptors in CD133+ve cancer stem cells in non-small cell lung carcinoma inhibits proliferation, clonogenic ability and invasiveness of these cells. [E-pub ahead of print] J. Biol. Chem. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cherubini E., Di Napoli A., Noto A., Osman G. A., Esposito M. C., Mariotta S., Sellitri R., Ruco L., Cardillo G., Ciliberto G., Mancini R., Ricci A. (2016) Genetic and functional analysis of polymorphisms in the human dopamine receptor and transporter genes in small cell lung cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 231, 345–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chakroborty D., Sarkar C., Yu H., Wang J., Liu Z., Dasgupta P. S., Basu S. (2011) Dopamine stabilizes tumor blood vessels by up-regulating angiopoietin 1 expression in pericytes and Kruppel-like factor-2 expression in tumor endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20730–20735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sarkar C., Chakroborty D., Chowdhury U. R., Dasgupta P. S., Basu S. (2008) Dopamine increases the efficacy of anticancer drugs in breast and colon cancer preclinical models. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 2502–2510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moreno-Smith M., Lee S. J., Lu C., Nagaraja A. S., He G., Rupaimoole R., Han H. D., Jennings N. B., Roh J. W., Nishimura M., Kang Y., Allen J. K., Armaiz G. N., Matsuo K., Shahzad M. M. K., Bottsford-Miller J., Langley R. R., Cole S. W., Lutgendorf S. K., Siddik Z. H., Sood A. K. (2013) Biologic effects of dopamine on tumor vasculature in ovarian carcinoma. Neoplasia 15, 502–510 IN14–IN15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Borcherding D. C., Tong W., Hugo E. R., Barnard D. F., Fox S., LaSance K., Shaughnessy E., Ben-Jonathan N. (2016) Expression and therapeutic targeting of dopamine receptor-1 (D1R) in breast cancer. Oncogene 35, 3103–3113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Da Prada M., Picotti G. B. (1979) Content and subcellular localization of catecholamines and 5-hydroxytryptamine in human and animal blood platelets: monoamine distribution between platelets and plasma. Br. J. Pharmacol. 65, 653–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Italiano J. E. Jr., Richardson J. L., Patel-Hett S., Battinelli E., Zaslavsky A., Short S., Ryeom S., Folkman J., Klement G. L. (2008) Angiogenesis is regulated by a novel mechanism: pro- and antiangiogenic proteins are organized into separate platelet alpha granules and differentially released. Blood 111, 1227–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zarei S., Frieden M., Rubi B., Villemin P., Gauthier B. R., Maechler P., Vischer U. M. (2006) Dopamine modulates von Willebrand factor secretion in endothelial cells via D2-D4 receptors. J. Thromb. Haemost. 4, 1588–1595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zornberg G. L., Jick H. (2000) Antipsychotic drug use and risk of first-time idiopathic venous thromboembolism: a case-control study. Lancet 356, 1219–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bambace N. M., Holmes C. E. (2011) The platelet contribution to cancer progression. J. Thromb. Haemost. 9, 237–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prandoni P., Falanga A., Piccioli A. (2005) Cancer and venous thromboembolism. Lancet Oncol. 6, 401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shtukmaster S., Schier M. C., Huber K., Krispin S., Kalcheim C., Unsicker K. (2013) Sympathetic neurons and chromaffin cells share a common progenitor in the neural crest in vivo. Neural Dev. 8, 12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kliewer K. E., Wen D. R., Cancilla P. A., Cochran A. J. (1989) Paragangliomas: assessment of prognosis by histologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural techniques. Hum. Pathol. 20, 29–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ureña J., Fernández-Chacón R., Benot A. R., Alvarez de Toledo G. A., López-Barneo J. (1994) Hypoxia induces voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry and quantal dopamine secretion in carotid body glomus cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 10208–10211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Benot A. R., López-Barneo J. (1990) Feedback inhibition of Ca2+ currents by dopamine in glomus cells of the carotid body. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2, 809–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Czyzyk-Krzeska M. F., Furnari B. A., Lawson E. E., Millhorn D. E. (1994) Hypoxia increases rate of transcription and stability of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 760–764 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Czyzyk-Krzeska M. F., Bayliss D. A., Lawson E. E., Millhorn D. E. (1992) Regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in the rat carotid body by hypoxia. J. Neurochem. 58, 1538–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schnell P. O., Ignacak M. L., Bauer A. L., Striet J. B., Paulding W. R., Czyzyk-Krzeska M. F. (2003) Regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase promoter activity by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein and hypoxia-inducible transcription factors. J. Neurochem. 85, 483–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Millhorn D. E., Raymond R., Conforti L., Zhu W., Beitner-Johnson D., Filisko T., Genter M. B., Kobayashi S., Peng M. (1997) Regulation of gene expression for tyrosine hydroxylase in oxygen sensitive cells by hypoxia. Kidney Int. 51, 527–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leclere N., Andreeva N., Fuchs J., Kietzmann T., Gross J. (2004) Hypoxia-induced long-term increase of dopamine and tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA levels. Prague Med. Rep. 105, 291–300 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nguyen M. V. C., Pouvreau S., El Hajjaji F. Z., Denavit-Saubie M., Pequignot J. M. (2007) Desferrioxamine enhances hypoxic ventilatory response and induces tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in the rat brainstem in vivo. J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 1119–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Milosevic J., Maisel M., Wegner F., Leuchtenberger J., Wenger R. H., Gerlach M., Storch A., Schwarz J. (2007) Lack of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha impairs midbrain neural precursor cells 20 involving vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. J. Neurosci. 27, 412–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Favier J., Kempf H., Corvol P., Gasc J. M. (1999) Cloning and expression pattern of EPAS1 in the chicken embryo: colocalization with tyrosine hydroxylase. FEBS Lett. 462, 19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Johansen J. L., Sager T. N., Lotharius J., Witten L., Mørk A., Egebjerg J., Thirstrup K. (2010) HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibition increases cell viability and potentiates dopamine release in dopaminergic cells. J. Neurochem. 115, 209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thompson R. J., Jackson A., Nurse C. A. (1997) Developmental loss of hypoxic chemosensitivity in rat adrenomedullary chromaffin cells. J. Physiol. 498, 503–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Salman S., Buttigieg J., Nurse C. A. (2014) Ontogeny of O2 and CO2//H+ chemosensitivity in adrenal chromaffin cells: role of innervation. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 673–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Joseph V., Pequignot J. M. (2003) Neurochemical processes involved in acclimatization to long-term hypoxia. In Oxygen Sensing: Responses and Adaptation to Hypoxia (Lahiri S., Semenza G. L., Prabhakar N. R., eds.), pp. 482–502, Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, Basel: [Google Scholar]

- 93.Saldana M. J., Salem L. E., Travezan R. (1973) High altitude hypoxia and chemodectomas. Hum. Pathol. 4, 251–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gimenez-Roqueplo A. P., Dahia P. L. M., Robledo M. (2012) An update on the genetics of paraganglioma, pheochromocytoma, and associated hereditary syndromes. Horm. Metab. Res. 44, 328–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Freiburg-Warsaw-Columbus Pheochromocytoma Study Group (2002) Germ-line mutations in nonsyndromic pheochromocytoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 1459–1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hao H. X., Khalimonchuk O., Schraders M., Dephoure N., Bayley J. P., Kunst H., Devilee P., Cremers C. W. R. J., Schiffman J. D., Bentz B. G., Gygi S. P., Winge D. R., Kremer H., Rutter J. (2009) SDH5, a gene required for flavination of succinate dehydrogenase, is mutated in paraganglioma. Science 325, 1139–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Qin Y., Yao L., King E. E., Buddavarapu K., Lenci R. E., Chocron E. S., Lechleiter J. D., Sass M., Aronin N., Schiavi F., Boaretto F., Opocher G., Toledo R. A., Toledo S. P., Stiles C., Aguiar R. C., Dahia P. L. M. (2010) Germline mutations in TMEM127 confer susceptibility to pheochromocytoma. Nat. Genet. 42, 229–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Comino-Méndez I., Gracia-Aznárez F. J., Schiavi F., Landa I., Leandro-García L. J., Letón R., Honrado E., Ramos-Medina R., Caronia D., Pita G., Gómez-Graña A., de Cubas A. A., Inglada-Pérez L., Maliszewska A., Taschin E., Bobisse S., Pica G., Loli P., Hernández-Lavado R., Díaz J. A., Gómez-Morales M., González-Neira A., Roncador G., Rodríguez-Antona C., Benítez J., Mannelli M., Opocher G., Robledo M., Cascón A. (2011) Exome sequencing identifies MAX mutations as a cause of hereditary pheochromocytoma. Nat. Genet. 43, 663–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Crona J., Delgado Verdugo A., Maharjan R., Stålberg P., Granberg D., Hellman P., Björklund P. (2013) Somatic mutations in H-RAS in sporadic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma identified by exome sequencing. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98, E1266–E1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hrasćan R., Pećina-Slaus N., Martić T. N., Colić J. F., Gall-Trošelj K., Pavelić K., Karapandža N. (2008) Analysis of selected genes in neuroendocrine tumours: insulinomas and phaeochromocytomas. J. Neuroendocrinol. 20, 1015–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Castro-Vega L. J., Buffet A., De Cubas A. A., Cascón A., Menara M., Khalifa E., Amar L., Azriel S., Bourdeau I., Chabre O., Currás-Freixes M., Franco-Vidal V., Guillaud-Bataille M., Simian C., Morin A., Letón R., Gómez-Graña A., Pollard P. J., Rustin P., Robledo M., Favier J., Gimenez-Roqueplo A. P. (2014) Germline mutations in FH confer predisposition to malignant pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 2440–2446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Schlisio S., Kenchappa R. S., Vredeveld L. C. W., George R. E., Stewart R., Greulich H., Shahriari K., Nguyen N. V., Pigny P., Dahia P. L. M., Pomeroy S. L., Maris J. M., Look A. T., Meyerson M., Peeper D. S., Carter B. D., Kaelin W. G. Jr (2008) The kinesin KIF1Bbeta acts downstream from EglN3 to induce apoptosis and is a potential 1p36 tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 22, 884–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gaal J., Burnichon N., Korpershoek E., Roncelin I., Bertherat J., Plouin P. F., de Krijger R. R., Gimenez-Roqueplo A. P., Dinjens W. N. (2010) Isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations are rare in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 1274–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yang C., Zhuang Z., Fliedner S. M. J., Shankavaram U., Sun M. G., Bullova P., Zhu R., Elkahloun A. G., Kourlas P. J., Merino M., Kebebew E., Pacak K. (2015) Germ-line PHD1 and PHD2 mutations detected in patients with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma-polycythemia. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 93, 93–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Astuti D., Ricketts C. J., Chowdhury R., McDonough M. A., Gentle D., Kirby G., Schlisio S., Kenchappa R. S., Carter B. D., Kaelin W. G. Jr., Ratcliffe P. J., Schofield C. J., Latif F., Maher E. R. (2010) Mutation analysis of HIF prolyl hydroxylases (PHD/EGLN) in individuals with features of phaeochromocytoma and renal cell carcinoma susceptibility. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 18, 73–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ladroue C., Carcenac R., Leporrier M., Gad S., Le Hello C., Galateau-Salle F., Feunteun J., Pouysségur J., Richard S., Gardie B. (2008) PHD2 mutation and congenital erythrocytosis with paraganglioma. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 2685–2692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhuang Z., Yang C., Lorenzo F., Merino M., Fojo T., Kebebew E., Popovic V., Stratakis C. A., Prchal J. T., Pacak K. (2012) Somatic HIF2A gain-of-function mutations in paraganglioma with polycythemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 922–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lorenzo F. R., Yang C., Ng Tang Fui M., Vankayalapati H., Zhuang Z., Huynh T., Grossmann M., Pacak K., Prchal J. T. (2013) A novel EPAS1/HIF2A germline mutation in a congenital polycythemia with paraganglioma. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 91, 507–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pacak K., Jochmanová I., Prodanov T., Yang C., Merino M. J., Fojo T., Prchal J. T., Tischler A. S., Lechan R. M., Zhuang Z. (2013) New syndrome of paraganglioma and somatostatinoma associated with polycythemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 1690–1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dahia P. L. M., Ross K. N., Wright M. E., Hayashida C. Y., Santagata S., Barontini M., Kung A. L., Sanso G., Powers J. F., Tischler A. S., Hodin R., Heitritter S., Moore F., Dluhy R., Sosa J. A., Ocal I. T., Benn D. E., Marsh D. J., Robinson B. G., Schneider K., Garber J., Arum S. M., Korbonits M., Grossman A., Pigny P., Toledo S. P., Nosé V., Li C., Stiles C. D. (2005) A HIF1alpha regulatory loop links hypoxia and mitochondrial signals in pheochromocytomas. PLoS Genet. 1, e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jochmanová I., Zhuang Z., Pacak K. (2015) Pheochromocytoma: gasping for air. Horm. Cancer 6, 191–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Favier J., Amar L., Gimenez-Roqueplo A. P. (2015) Paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma: from genetics to personalized medicine. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 11, 101–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shah U., Giubellino A., Pacak K. (2012) Pheochromocytoma: implications in tumorigenesis and the actual management. Minerva Endocrinol. 37, 141–156 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Eisenhofer G., Huynh T. T., Pacak K., Brouwers F. M., Walther M. M., Linehan W. M., Munson P. J., Mannelli M., Goldstein D. S., Elkahloun A. G. (2004) Distinct gene expression profiles in norepinephrine- and epinephrine-producing hereditary and sporadic pheochromocytomas: activation of hypoxia-driven angiogenic pathways in von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 11, 897–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Welander J., Söderkvist P., Gimm O. (2011) Genetics and clinical characteristics of hereditary pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 18, R253–R276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Menko F. H., Maher E. R., Schmidt L. S., Middelton L. A., Aittomäki K., Tomlinson I., Richard S., Linehan W. M. (2014) Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam. Cancer 13, 637–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Adam J., Yang M., Soga T., Pollard P. J. (2014) Rare insights into cancer biology. Oncogene 33, 2547–2556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Osinga T. E., Korpershoek E., de Krijger R. R., Kerstens M. N., Dullaart R. P. F., Kema I. P., van der Laan B. F. A. M., van der Horst-Schrivers A. N. A., Links T. P. (2015) Catecholamine synthesizing enzymes are expressed in parasympathetic head and neck paraganglioma tissue. Neuroendocrinology 101, 289–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Van Duinen N., Steenvoorden D., Kema I. P., Jansen J. C., Vriends A. H. J. T., Bayley J. P., Smit J. W. A., Romijn J. A., Corssmit E. P. M. (2010) Increased urinary excretion of 3-methoxytyramine in patients with head and neck paragangliomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 209–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Van Duinen N., Corssmit E. P. M., de Jong W. H. A., Brookman D., Kema I. P., Romijn J. A. (2013) Plasma levels of free metanephrines and 3-methoxytyramine indicate a higher number of biochemically active HNPGL than 24-h urinary excretion rates of catecholamines and metabolites. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 169, 377–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Van Der Horst-Schrivers A. N. A., Osinga T. E., Kema I. P., Van Der Laan B. F. A. M., Dullaart R. P. F. (2010) Dopamine excess in patients with head and neck paragangliomas. Anticancer Res. 30, 5153–5158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Osinga T. E., van der Horst-Schrivers A. N., van Faassen M., Kerstens M. N., Dullaart R. P., Peters M. A., van der Laan B. F., de Bock G. H., Links T. P., Kema I. P. (2016) Dopamine concentration in blood platelets is elevated in patients with head and neck paragangliomas. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 54, 1395–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Eisenhofer G., Lenders J. W., Timmers H., Mannelli M., Grebe S. K., Hofbauer L. C., Bornstein S. R., Tiebel O., Adams K., Bratslavsky G., Linehan W. M., Pacak K. (2011) Measurements of plasma methoxytyramine, normetanephrine, and metanephrine as discriminators of different hereditary forms of pheochromocytoma. Clin. Chem. 57, 411–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kimura N., Chetty R., Capella C., Young W. F., Koch C. A., Lam K. Y., DeLellis R. A., Kawashima A., Komminoth P., Tischler A. S. (2004) Extra-adrenal paraganglioma: carotid body, jugulotympanic, vagal, laryngeal, aortico-pulmonary. In Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Endocrine Organs (DeLellis R. A., Lloyed R. V., Heitz P. U., Eng C., eds.) pp. 159–161, IARC Press, Lyon, France [Google Scholar]