Abstract

Introduction: Cancer cells are critically correlated with lipid molecules, particularly fatty acids, as structural blocks for membrane building, energy sources, and related signaling molecules. Therefore, cancer progression is in direct correlation with fatty acid metabolism. The aim of this study was to investigate the potential effects of common chemotherapeutic agents on the lipid metabolism of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) cells, with a focus on alterations in cellular fatty acid contents.

Methods: Human HepG2 and SW480 cell lines as HCC and CRC cells were respectively cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with non-toxic doses of 5-fluorouracil and doxorubicin for 72 hours. Oil Red O dye was used to estimate intracellular lipid vacuole intensity. Fatty acid analysis of isolated membrane phospholipids and cytoplasmic triglycerides (TG) was performed by gas-liquid chromatography (GLC) technique.

Results: Oil red O staining represented significantly higher lipid accumulation and density in cancer cells after exposure to the chemotherapeutic agents as compared to non-treated control cells. Doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil treatment promoted the channeling of saturated fatty acids (SFAs) from phospholipids to triglyceride pool in both HepG2 (+5.91% and +8.50%, P < 0.05, respectively) and SW480 (+37.41% and +5.73%, P < 0.05, respectively) cell lines. However, total polyunsaturated fatty acid content was inversely shifted from TG to phospholipid fraction after doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil incubation of HepG2 (+58.89% and +29.13%, P < 0.05, respectively) and SW480 (+19.20% and +14.65%, P < 0.05, respectively) cells.

Conclusion: Our data showed that common chemotherapeutic agents of HCC and CRC can induce significant changes in cellular lipid accumulation and distribution of fatty acids through producing highly saturated and unsaturated lipid droplets and membrane lipids, respectively. These metabolic side effects may be associated with gastrointestinal cancers treatment failure.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Doxorubicin, Fatty acids, Fluorouracil, Lipid droplets

Introduction

Fatty acids as a major constituent of lipids are important in multiple cellular processes including membrane fluidity, differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis.1-5 De novo synthesis of fatty acids and their incorporation to different cellular lipids are catalyzed by different metabolic pathways, which are essential for lipid storage and providing precursors for structural components. Therefore, exact regulation of fatty acid metabolism is a crucial part of normal cell biology. Accordingly, imbalance in fatty acid synthesis and their distribution obviously lead to cellular abnormalities.6 Despite significant therapeutic impacts of chemotherapy as the first line treatment for most cancer diseases, metabolic side effects and toxicity are the main limitations of chemotherapeutic agents administration in cancer therapy.7 Many in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies have found that polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) improve chemotherapy responses and effectiveness in different human cancers.8 Senkal et al9 reported a higher serum levels of 18 carbon acyl-ceramide, a minor lipid precursor, after doxorubicin (Dox) chemotherapy in patients with carcinoma. However, the effects of chemotherapeutic drugs on fatty acid distribution in triglycerides (TG) and phospholipids as major cellular lipids still remain unclear. Doxorubicin, as a chemotherapeutic agent, is widely used in the treatment of different malignancies including colorectal cancer (CRC) through intercalating DNA molecules.10 The 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is another common anti-tumor drug for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), acting as a thymidylate synthase inhibitor.11 Because no study has yet revealed the effects of chemotherapeutic agents on cellular fatty acid composition, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of Dox and 5-FU on intracellular accumulation of the neutral lipid triglyceride and the fatty acid composition in HCC and CRC cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

HepG2 and SW-480 from human HCC and CRC cell lines, respectively, were obtained from Pasteur Institute, Tehran, Iran, and grown in L-glutamine rich RPMI-1640 medium (Life Technologies, Waltham, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Atocel, ATSS-265, Budapest, Hungry) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (10 000 U/mL penicillin, 10 mg/mL streptomycin) (Sigma-Aldrich, P4333, Munich, Germany) at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. Then, cells were sub-cultured in 6- and 24-well plates in the following experiments at a logarithmic growth phase for 72 hours.

The half maximal inhibitory concentration assay

Cytotoxic effects of 5-FU (Sigma Aldrich, F6627, Munich, Germany) and Dox (Sigma Aldrich, D1515, Munich, Germany) were assessed using 1-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-3,5-diphenylformazan (MTT) assay (Sigma Aldrich, M2003, Munich, Germany). Briefly, 15×103 HepG2 and SW480 cells were seeded in three 96-well plates and were exposed to various concentrations of 5-FU and Dox including 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 μg/mL. In order to prevent drug inactivation, drugs were renewed every 24 hours. After 24, 48 and 72 hours, the medium was discarded and MTT solution at a final concentration of 5 mg/mL was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 4 hours. DMSO (100 μL) was then added to stop the reaction and the optical density was measured using an ELlSA reader (BioTeck, Vinooski, VT, USA) in 570 nm wavelength. The viability of cells was evaluated relative to theoretical absorbance. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Drug treatment

A total of 106 cells were seeded in 6-well plates for each treatment. A non-toxic dose of chemotherapeutic agents as determined by MTT assay including 5-FU and Dox were added to HepG2 and SW-480 culture media for 72 hours at a dose of 2 μg/mL. Drugs were re-treated every 24 hours in order to minimize drug inactivation effect. At 72 hours time point, cells were trypsinized and collected for fatty acid analysis.

Oil Red O staining

A total of 150 000 HepG2 and SW480 cells were cultured and treated in 24-well plates as described above. Oil Red O dye (Merck Millipore, 105230) was used for lipid vacuoles staining. An amount of 0.3% in isopropanol (Merck Millipore, 109634, Massachusetts, USA) of Oil Red O stock was prepared and filtered by 0.4 μm pore syringe filter. For cellular staining, 3 parts of stock solution were mixed with 2 parts of deionized water. Culture medium was removed from each well and cells were washed and rinsed with 1X PBS. Cells then were fixed for 20 minutes in paraformaldehyde 4% (Merck, 818715, Darmstadt, Germany) and washed twice using PBS. Then, Oil Red O dye was added to the wells and incubated for 15 minutes. Finally, the dye was removed from each well and cells were washed with PBS in order to exclude the excess dye. Images were acquired by a light inverted microscope (Labomed, LB-290).

Total lipid extraction

Cellular total lipids were extracted according to Bligh & Dyer protocol.12 Briefly, collected cells were suspended in 1 mL distilled water and 3.75 mL of chloroform/methanol (MeOH) (1:2) solution (Merck, 102445 and 107018, respectively). After centrifugation at 3000 RPM for 5 minutes, the supernatant was recovered and 1.25 mL of chloroform and distilled water were added and the solution was mixed vigorously. After following centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 5 minutes, the chloroform phase (lower phase) containing extracted lipids was recovered and used for further experiments.

Triglyceride and membrane phospholipid isolation

For extraction of TG and membrane phospholipids (PL), chloroform phase containing total lipid was vaporized in 37°C water bath under a flow of nitrogen gas and the total lipid concentrate was transferred to silica gel thin layer chromatography (TLC) plate (Merck, 105553, Darmstadt, Germany). TLC plates with samples were located in a chromatography tank containing a mobile phase composed of hexane/diethyl ether/glacial acetic acid (90:10:3) (Merck, 104374, 100921, 100056, respectively) for 90 minutes. After this time, the rate of flow of PL and TG was determined according to standards. Specified fraction regions were scratched and transferred into screw cap glass tubes for direct transesterification (see Supplementary file, Figs. S1 and S2).

Direct transesterification (methylation)

Lipid extracts were subjected to direct transesterification according to Lepage et al method.13 Briefly, 2 mL of MeOH/Hexane (4:1) solution containing 50 μg/mL of internal standard (Tridecanoate, 13:0) (Sigma Aldrich, 91558, Munich, Germany) was added to the extracts. Then, 200 μL of acetyl chloride (Merck, 822252, Darmstadt, Germany) was also added and the tubes were incubated at 100°C for 1 hour in a tightly closed system. After acid catalysis step, 5 mL of 6% potassium bicarbonate (Merck, 104852, Darmstadt, Germany) was added to the tubes and mixed. Then hexane phase (upper phase) was recovered for gas-liquid chromatography (GLC) analysis.

Gas-liquid chromatography analysis

Extracted fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were subjected to GLC analysis using a Buck Scientific 610 system (East Norwalk, USA) and separated on a TR-CN100 capillary column (60 m × 0.25 m × 0.2 µM) (Teknokroma, Spain). Flame ionization detector was used for detection and characterization of fatty acids according to a standard mix of FAMEs. Helium was used as the carrier gas. The oven temperature was programmed from 190°C to 210°C at the rate of 1°C/min and then maintained stable for 20 minutes. Peak retention times and areas of standard chromatograms were generated by injecting known standards. The area under curve for each FAME was calculated using Peak Simple 3.59 software (SRI instrument, Torrance, USA) (Supplementary file, Figs. S3 and S4). Fatty acid data were presented as percentage change relative to control cells.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 3 separate experiments done in triplicate. Comparison of means between groups was performed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Tukey’s tests. P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The half maximal inhibitory concentration

Cytotoxic effect of 5-FU on HepG2 and SW480 cells initially were evaluated using a standard MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 1, cell viability was decreased dose and time dependently. Based on the resulting equation, the half inhibitory concentrations 50 (IC50) of Dox and 5-FU for 72-hour time point in HepG2 and SW480 were 3.8, 4.1 and 3.1, 4.4 μg/mL, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 5-fluorouracil and doxorubicin on HepG2 and SW480 cells (viable cells as a percentage of control). Cell viability was decreased dose- and time-dependently after 5-fluorouracil and doxorubicin exposure. IC50 was calculated according to every time point equation. For drug inactivity prevention, drugs were renewed every 24 hours. Cell viability is presented as percentage of viable cells versus control.

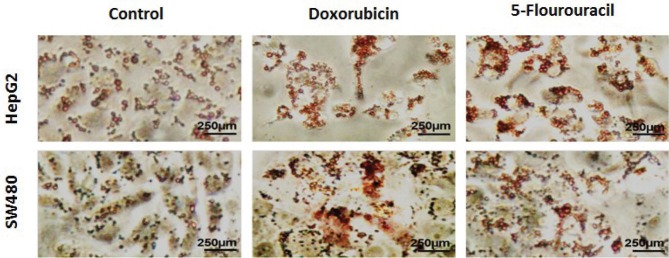

Oil Red O staining showed lipid accumulation in gastrointestinal cancer cells following treatment with chemotherapeutic agents

To investigate cellular lipid content, HepG2 and SW480 cultured cells were analyzed using Oil Red O staining after 72 hours exposure to Dox and 5-FU drugs. As shown in Fig. 2, significant increases in number and density of intracellular lipid droplets were observed in both GI cancer cells.

Fig. 2.

Photomicrographs of lipid accumulation in HepG2 and SW480 cells prepared by Oil Red O staining after treatment with non-toxic concentrations of doxorubicin (2 μg/mL) and 5-fluorouracil (2 μg/mL) for 72 hours. The magnitude scale was 250 μm.

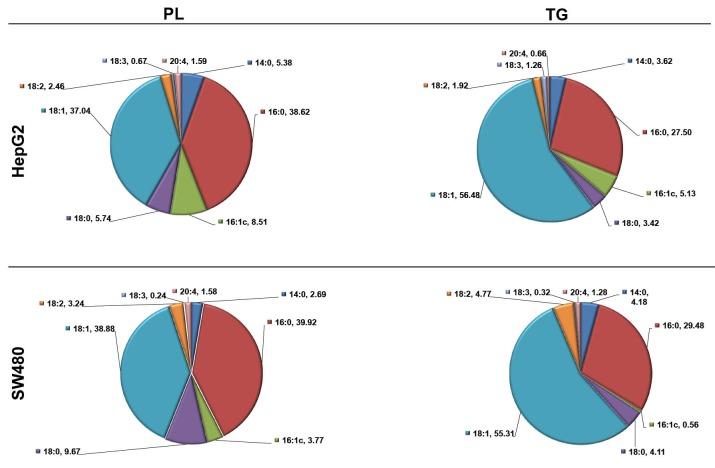

Fatty acid profile of HepG2 and SW480 cells according to lipid fraction type following drug treatments

Fig. 3 shows fatty acid composition of PL and TG fractions in HepG2 and SW480 cells. In both cells palmitic acid and oleic acid were the major cellular fatty acids in TG (27.50% and 29.47%; 56.48% and 55.30%, respectively) and PL (38.62% and 39.92%; 37.04% and 38.88%, respectively) fractions.

Fig. 3.

Composition of fatty acids in HepG2 and SW480 cells according to the lipid fraction. TG, triglyceride; PL, phospholipid; 14:0, myristic acid; 16:0, palmitic acid; 16:1, palmitoleic acid; 18:0, stearic acid; 18:1, oleic acid; 18:2, linoleic acid; 18:3, linolenic acid; 20:4, Arachidonic acid. Data are presented as a percentage of total fatty acid.

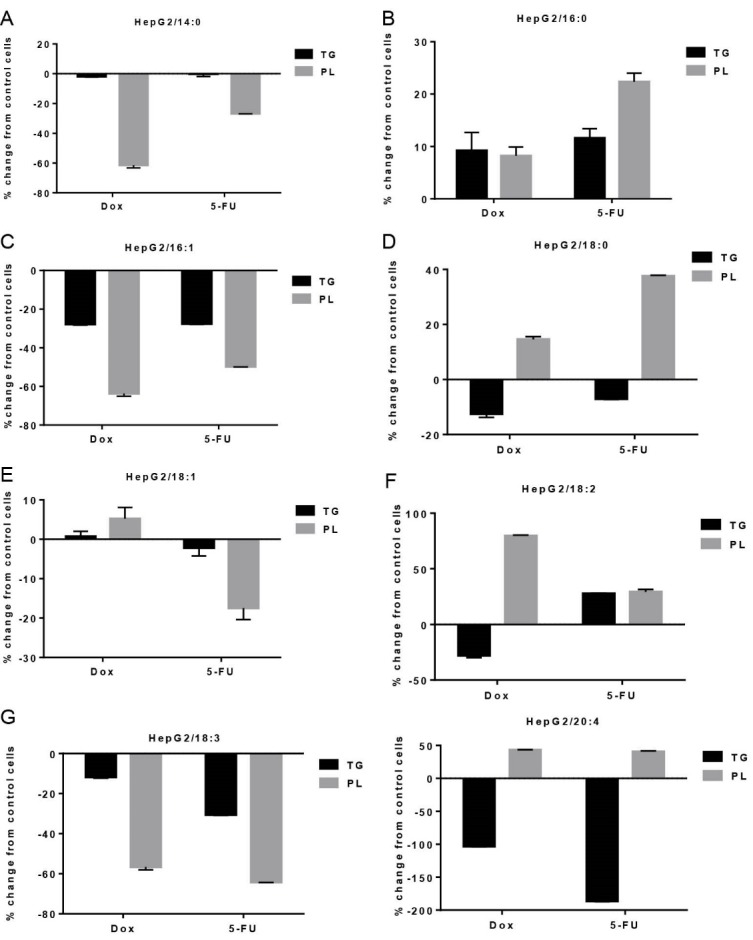

Chemotherapy altered fatty acid distribution between phospholipids and triglycerides in GI cancer cells

HepG2 cells

As shown in Fig. 4B, there was a significant increase in palmitic acid after Dox and 5-FU treatment in both TG (+9.21% and +11.57 %, P<0.05, respectively) and PL (+8.21% and +22.32%, P<0.05, respectively) fractions. A significant decrease in oleic acid only in PL fraction was observed after 5-FU treatment (-17.47%, P<0.05, Fig. 4E). However, a shift of linoleic acid from TG to PL pool was also observed after Dox chemotherapy (-79.57%, P<0.05, Fig. 4F). Both chemotherapeutic agents induced a shift from TG to PL fraction in stearic acid (-12.45% and -7.04%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 4D) and arachidonic acid (-50.78% and -65.07%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 4H). Significant decreases in myristic acid (-61.35% and -26.79%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 4A) and palmitoleic acid (-63.72% and -49.79%, P<0.05, respectively) were also observed in the PL fraction after exposure to chemotherapeutic agents. Linolenic acid was also significantly decreased in both TG and PL fractions after treatment with Dox and 5-FU (-11.79% and -30.57%; -56.64% and -64.21%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 4G).

Fig. 4.

Effects of non-toxic doses of doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil on individual fatty acid distribution between triglyceride (TG) and phospholipids (PL) fractions in HepG2 cells. Data are presented as percent change from control, mean ± SD, n = 3. 14:0, myristic acid; 16:0, palmitic acid; 16:1, palmitoleic acid; 18:0, stearic acid; 18:1, oleic acid; 18:2, linoleic acid; 18:3, linolenic acid; 20:4, arachidonic acid.

After Dox and 5-FU treatment saturated fatty acids (SFA) were mainly increased in TG fraction (+5.91% and +8.50%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 5A). However, a shift of SFAs to membrane PL was also observed in HepG2 cells after 5-FU treatment (+18.78%, P<0.05, Fig. 5A). Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) were decreased mainly in PL fractions (-7.65% and -23.51%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 5B). In contrast, PUFA were only increased in membrane phospholipid fraction (+58.89% and +29.13%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 5C) and decreased in cellular TGs (-26.50% and -7.32%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 5C) after Dox and 5-FU treatment.

Fig. 5.

5. Effects of non-toxic doses of doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil on fatty acid distribution between triglyceride (TG) and phospholipids (PL) fractions in HepG2 cells. A: saturated fatty acids (SFA), B: monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and C: polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). Data are presented as percent change from control, mean ± SD, n = 3.

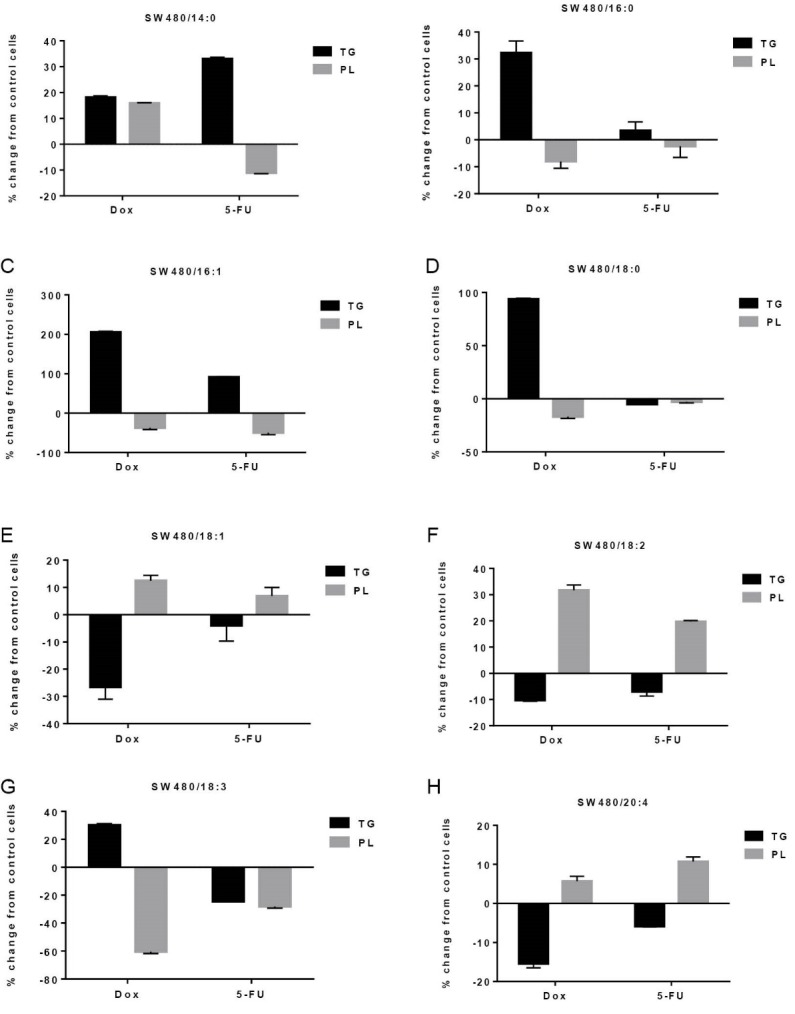

SW480 cells

As shown in Fig. 6, after Dox and 5-FU treatment significant increases in SFAs of TG fraction including myristic acid (+18.17% and +33.07%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 6A), palmitic acid (+32.30%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 6B) and stearic acid (+93.63%, P<0.05, Fig. 6D) were observed. Both Dox and 5-FU induced a shift from PL (-3723% and -49.64%, P<0.05, respectively) to TG (+205.56% and +91.84%, P<0.05, respectively) in palmitoleic acid (Fig. 6C). Inversely, oleic acid (+12.47%, P<0.05 and +6.83%, P>0.05, respectively, Fig. 6E), linoleic acid (+31.68% and +19.72%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 6F) and arachidonic acid (+5.69% and 10.71%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 6H) shifted from TG to PL fraction upon exposure to chemotherapeutic agents. 5-FU treatment resulted a significant decrease in linolenic acid in Both PL (-28.03%, P<0.05) and TG (-24.31%, P<0.05) fractions (Fig. 6G). However, Dox treatment caused a significant decrease and increase of linolenic acid in PL (-60.48%, P<0.05) and TG (+30.22%, P<0.05), respectively (Fig. 6G).

Fig. 6.

Effects of non-toxic doses of doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil on individual fatty acid distribution between triglyceride (TG) and phospholipids (PL) fractions in SW480 cells. Data are presented as percent change from control, mean±SD, n=3. 14:0, myristic acid; 16:0, palmitic acid; 16:1, palmitoleic acid; 18:0, stearic acid; 18:1, oleic acid; 18:2, linoleic acid; 20:4, arachidonic acid.

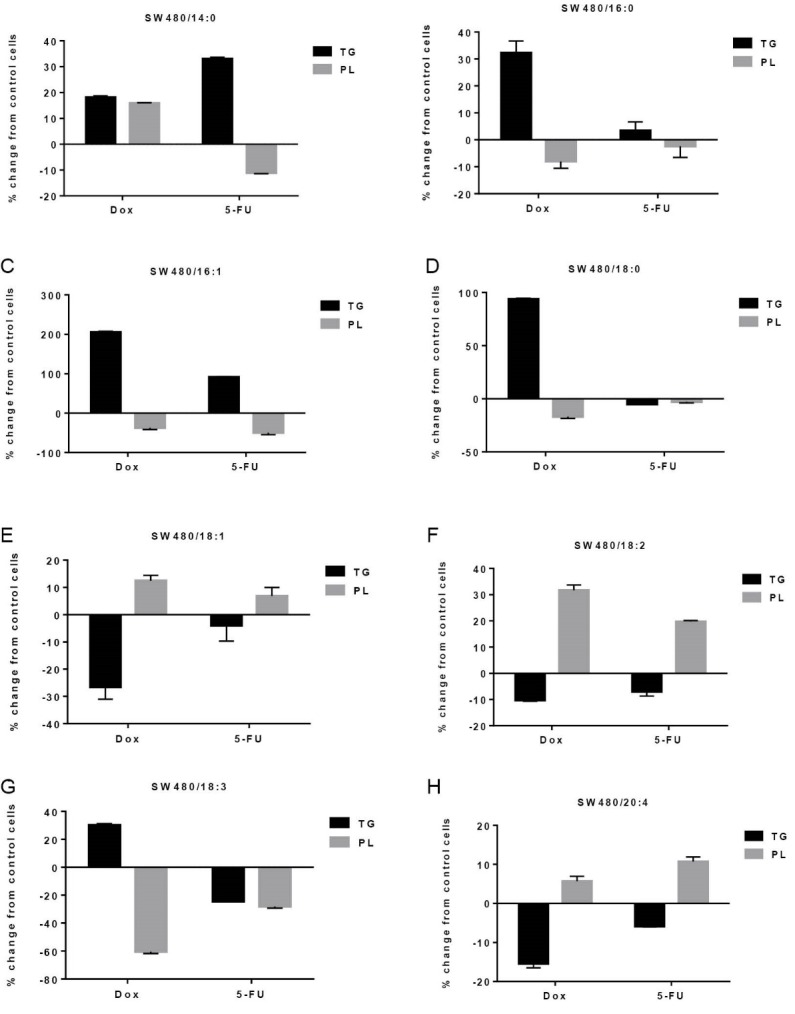

Changes in main groups of fatty acids are shown in Fig. 7. Both chemotherapeutic agents induced a SFA shift from PL to TG fraction (+37.41% and +5.73%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 7A) while MUFA (+8.02% and +1.83%, P>0.05, respectively, Fig. 7B) and PUFA (+19.20% and 14.65%, P<0.05, respectively, Fig. 7C) shifted from TG to PL.

Fig. 7.

Effects of non-toxic doses of doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil on fatty acid distribution between triglyceride (TG) and phospholipids (PL) fractions in SW480 cells. A: saturated fatty acids (SFA), B: monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and C: polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). Data are presented as percent change from control, mean±SD, n=3.

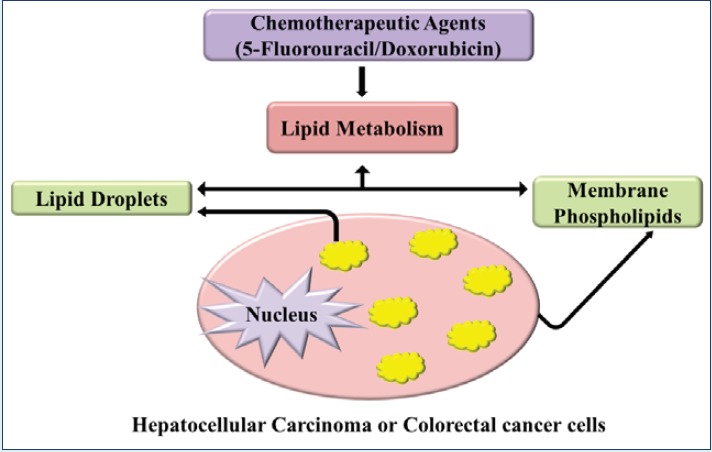

Discussion

Cancer is the second cause of death worldwide after cardiovascular diseases. Despite some successful achievements in cancer treatments, cytotoxic therapies with available chemotherapeutic agents have clinical limitations, leading to treatment failure, cancer relapse and clinically short overall survival in patients.14 Cancer cells undergo major changes in terms of lipid metabolism. In these highly proliferating cells, carbon atoms must be incorporated into fatty acid synthesis for membrane formation and signaling molecules production instead of energy production.5 Recent studies have considered membrane fluidity as an important factor for cancer cell invasion and metastasis.15 In addition, it has been previously reported that membrane of cancer cells with higher potential of metastasis has a lower cholesterol/phospholipid ratio and higher unsaturated PL increasing membrane fluidity.16 Previous studies have indicated that tumor cells have higher ability for agglutination relative to normal cells through affecting lateral mobility and distribution of lectin receptor complexes such as concanavalin A. This difference of ability is attributed to differences in the arrangement capability of membrane receptors with increased membrane fluidity.15 In general, n6-PUFAs have pro-inflammatory roles.17 Different studies have declared the roles of n6-PUFAs in tumor growth and metastasis.18 In this study, fatty acid analysis of PL and TG fractions in HepG2 and SW480 cell lines showed a relatively higher amount of n6-PUFAs including linoleic acid and arachidonic acid. Furthermore, fatty acid changes after Dox and 5-FU treatment showed an increase in PUFA content of membrane PL in both cell lines. This selective incorporation of PUFAs into PLs may profoundly increase membrane fluidity. There are several enzymes that regulate the fine distribution of fatty acids among cellular lipids.16 Chemotherapeutic agents may differently alter the activity of these enzymes. For instance, arachidonic acid is only incorporated in membrane PL during fatty acid remodeling due to acyl-CoA: lysophospholipid acyltransferase in mammalian cells.19 Similarly, a large portion of stearic acid is also shifted into PL pool in the remodeling process.19 In HepG2 cells, a shift of SFAs to PL was also observed. Rysmon et al20 reported that shift from lipid uptake to de novo lipogenesis leads to increased saturated and monounsaturated membrane lipids in cancer cells protecting them from oxidative damages via decreased lipid peroxidation. In a related study, increased concentration of 18 carbon acyl-ceramide, a sphingosine alcohol mainly bound to stearic acid was observed after gemcitabine and Dox chemotherapy in a mice xenograft model of human cancer.21 Ceramide is a sphingolipid precursor and quantitatively is a minor cellular lipid. In the present study, lipid accumulation and global fatty acid composition of PL and TG fractions, as major cellular lipids, were analyzed after chemotherapy. Recent studies have revealed that lipid droplets are biosynthesized during inflammation and cancer, and participate in different cellular processes including cell metabolism, eicosanoid formation and proliferation.22 Here, we showed an increase in the number and density of lipid droplets and a shift of SFAs from PL to TG pool after drug treatment in GI cancer cell lines, indicating that chemotherapeutic drug treatment could increase saturated lipid droplets. Future experiments with migration assay and activity measurement of enzymes responsible for fatty acids re-distribution may improve explanation of these chemotherapeutic side effects.

Conclusion

Fatty acid storage and distribution are two main aspects of cellular lipid balance, and are important in different cell processes. Our data revealed that common chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil could potentially trigger cancer cell invasion and metastasis through increasing lipid accumulation and membrane fluidity. Therefore, novel therapeutic strategies that target fatty acid distribution may improve efficiency and attenuate side effects of chemotherapy in liver and GI cancers.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed as part of the PhD Dissertation (Thesis No.: 131/216). This study was supported by Liver and Gastrointestinal Diseases Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Grant #: 131/216). Authors would like to acknowledge Stem Cell Research Center and Department of Biochemistry and Clinical Laboratories, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for their great help.

Ethical issues

There is none to be declared.

Conflict of interests

There is no potential conflict of interests.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file 1 contains Figs. S1-S4.

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

√ Common chemotherapeutic agents may induce important effects on the metabolism of fatty acids in gastrointestinal cancer cells.

What is new here?

√ Common chemotherapeutic agents of gastrointestinal cancers can induce production of highly saturated lipid droplets and unsaturated membrane lipids.

References

- 1.Ibarguren M, López DJ, Escribá PV. The effect of natural and synthetic fatty acids on membrane structure, microdomain organization, cellular functions and human health. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1838:1518–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahimi Y, Mehdizadeh A, Nozad Charoudeh H, Nouri M, Valaei K, Fayezi S. et al. Hepatocyte differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells is modulated by stearoyl‐CoA desaturase 1 activity. Dev Growth Differ. 2015;57:667–74. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fritsche KL. The science of fatty acids and inflammation. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:293–301. doi: 10.3945/an.114.006940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockett BD, Salameh M, Carraway K, Morrison K, Shaikh SR. n-3 PUFA improves fatty acid composition, prevents palmitate-induced apoptosis, and differentially modifies B cell cytokine secretion in vitro and ex vivo. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1284–97. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M000851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Currie E, Schulze A, Zechner R, Walther TC, Farese RV. Cellular fatty acid metabolism and cancer. Cell Metab. 2013;18:153–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan DI, Vogel HJ. Current understanding of fatty acid biosynthesis and the acyl carrier protein. Biochem J. 2010;430:1–19. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morland SL, Martins KJ, Mazurak VC. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation during cancer chemotherapy. J Nutr Intermed Metab 2016.

- 8.Silva JdAP, de Souza Fabre ME, Waitzberg DL. Omega-3 supplements for patients in chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy: A systematic review. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:359–66. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saddoughi SA, Garrett-Mayer E, Chaudhary U, O'Brien PE, Afrin LB, Day TA. et al. Results of a phase II trial of gemcitabine plus doxorubicin in patients with recurrent head and neck cancers: serum c18-ceramide as a novel biomarker for monitoring response. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6097–105. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye P, Xing H, Lou F, Wang K, Pan Q, Zhou X. et al. Histone deacetylase 2 regulates doxorubicin (Dox) sensitivity of colorectal cancer cells by targeting ABCB1 transcription. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77:613–21. doi: 10.1007/s00280-016-2979-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uchibori K, Kasamatsu A, Sunaga M, Yokota S, Sakurada T, Kobayashi E. et al. Establishment and characterization of two 5-fluorouracil-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:1005–10. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bligh E. Extraction of lipids in solution by the method of Bligh & Dyer. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–7. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lepage G, Roy CC. Direct transesterification of all classes of lipids in a one-step reaction. J Lipid Res. 1986;27:114–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Eliseo D, Velotti F. Omega-3 fatty acids and Cancer cell cytotoxicity: implications for multi-targeted cancer therapy. J Clin Med. 2016;5:15. doi: 10.3390/jcm5020015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ajdžanović V, Mojić M, Maksimović-Ivanić D, Bulatović M, Mijatović S, Milošević V. et al. Membrane fluidity, invasiveness and dynamic phenotype of metastatic prostate cancer cells after treatment with soy isoflavones. J Membr Biol. 2013;246:307–14. doi: 10.1007/s00232-013-9531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherbet G. Membrane fluidity and cancer metastasis. Pathobiology. 1989;57:198–205. doi: 10.1159/000163526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patterson E, Wall R, Fitzgerald G, Ross R, Stanton C. Health implications of high dietary omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Nutr Metab. 2012;2012:539426. doi: 10.1155/2012/539426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torosian MH, Charland SL, Lappin JA. Differential effects of w-3 and w-6 fatty acids on primary tumor growth and metastasis. Int J Oncol. 1995;7:667–72. doi: 10.3892/ijo.7.3.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Digel M, Ehehalt R, Stremmel W, Füllekrug J. Acyl-CoA synthetases: fatty acid uptake and metabolic channeling. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;326:23–28. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-0003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baenke F, Peck B, Miess H, Schulze A. Hooked on fat: the role of lipid synthesis in cancer metabolism and tumour development. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6:1353–63. doi: 10.1242/dmm.011338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Senkal CE, Ponnusamy S, Rossi MJ, Sundararaj K, Szulc Z, Bielawski J. et al. Potent antitumor activity of a novel cationic pyridinium-ceramide alone or in combination with gemcitabine against human head and neck squamous cell carcinomas in vitro and in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:1188–99. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.101949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bozza PT, Viola JP. Lipid droplets in inflammation and cancer. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2010;82:243–50. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file 1 contains Figs. S1-S4.