Abstract

Background

Neck dissection for laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) patients could provide complementary prognostic information for AJCC N staging, like lymph node ratio (LNR). The aim of this study was to develop effective nomograms to better predict survival for LSCC patients treated with neck dissection.

Results

2752 patients were identified and randomly divided into training (n = 2477) and validation (n = 275) cohorts. The 3- and 5-year probabilities of cancer-specific mortality (CSM) were 30.1% and 37.2% while 3- and 5-year death resulting from other causes (DROC) rate were 6.2% and 11.3%, respectively. 13 significant prognostic factors including LNR for overall (OS) and 12 (except race) for CSS were enrolled in the nomograms. Concordance index as a commonly used indicator of predictive performance, showed the nomograms had superiority over the no-LNR models and TNM classification (Training-cohort: OS: 0.713 vs 0.703 vs 0.667, CSS: 0.725 vs 0.713 vs 0.688; Validation-cohort: OS: 0.704 vs 0.690 vs 0.658, cancer-specific survival (CSS): 0.709 vs 0.693 vs 0.672). All calibration plots revealed good agreement between nomogram prediction and actual survival.

Materials and Methods

We identified LSCC patients undergoing neck dissection diagnosed between 1988 and 2008 from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Optimal cutoff points were determined by X-tile program. Cumulative incidence function was used to analyze cancer-specific mortality (CSM) and death resulting from other causes (DROC). Significant predictive factors were used to establish nomograms estimating overall (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS). The nomograms were bootstrapped validated both internally and externally.

Conclusions

Comprehensive nomograms were constructed to predict OS and CSS for LSCC patients treated with neck dissection more accurately.

Keywords: laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, nomogram, overall survival, cancer-specific survival, lymph node ratio

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, there are estimated 13430 new cases diagnosed with laryngeal cancer in 2016 and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) accounts for the vast majority of all laryngeal malignancies [1, 2]. In patients with LSCC, particularly for supraglottic area with abundant lymphatic network, there is a relatively high incidence of macro- or micrometastases, and involvement of even one lymph node might lead to a 50% reduction in survival time [3, 4]. Currently it’s hard to detect these micrometastases by non-invasive methods [5, 6]. As a result, NCCN guideline recommends neck dissection for LSCC patients who are at risk for occult lymph node metastases in order to examine and remove the potential nodal focus [7]. Besides, neck dissection could also determine the necessity of adjuvant therapy and provide important predictive and prognostic information like lymph node ratio (LNR), which was defined as the number of pathologically positive nodes divided by the total counts of examined lymph nodes.

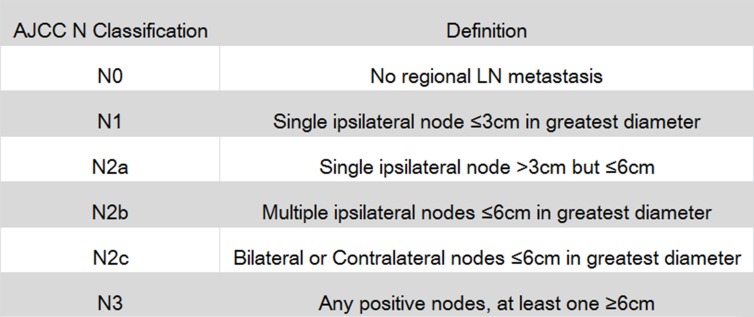

Integrating information on regionally metastatic burden with the extent of neck dissection, prognostic value of LNR for LSCC patients has been verified by several previous studies with large sample size [8–11]. However, AJCC N staging only provides information on maximal size, number and laterality of metastatic lymph nodes (Figure 1). Therefore, LNR can be used as a supplementary factor for N staging to describe lymph node status. In addition, AJCC T classification for laryngeal cancer was merely based on range of tumor invasion, combination of T staging and tumor size is also likely to better reflect tumor status from different aspects.

Figure 1. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) N staging for laryngeal cancer.

LN is short for lymph node.

There is a growing trend to use nomogram for cancer prognosis, specific nomograms have been successfully built for estimating survival, recurrence or local control for many cancer types [12–15]. Egelmeer et al have constructed nomograms for laryngeal cancer patients, however, the patients enrolled in that study only included patients treated with radiotherapy alone and whether those patients underwent neck dissection was unclear [16]. To the best of our knowledge, for LSCC patients, especially for those who underwent neck dissection, nomograms which make full use of available prognostic factors to predict survival have not been reported yet. Therefore in this study, we aimed to develop more practical and effective models for estimating OS and CSS for LSCC patients treated with neck dissection, in order to assist clinicians in predicting LSCC patient’s individualized survival.

RESULTS

Patient baseline characteristics

A total of 2752 LSCC patients treated with neck dissection diagnosed between 1988 and 2008 were identified from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. We randomly allocated 2477 patients into the training cohort and other 275 in the validation cohort.

For the training cohort, the median follow-up time until censoring or death was 58 months (Range: 1–311 months) and the median age was 60 years old (Range: 24–96). Of these 2477 patients in the training cohort, 79.7% were male and 73.5% were white. We also observed that primary tumor in 57.3% of patients who received neck dissection arose from supraglottis, 53% were staged N0 while more than 60% were staged T3 and T4. Besides of neck dissection, 33.1% of enrolled patients received only cancer-directed surgery (30.3%) or only radiotherapy (2.8%) while the others (66.9%) underwent both of the treatment modalities. (Note: information on chemotherapy was not accessible in SEER database.) Results of neck dissection showed that the median of node examination counts was 25 (Range: 1–89) and the median of LNR was 0.019 (Range: 0–1), respectively. By the cutoff date of follow-up, 1159 patients (46.8%) had died from primary cancer and 612 (28.7%) died from other causes (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of patients.

| Characteristic | All patients | Training cohort | Validation cohort | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2752 | n = 2477 | n = 275 | ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Categorical variables | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 569 | 20.7 | 503 | 20.3 | 66 | 24.0 |

| Male | 2183 | 79.3 | 1974 | 79.7 | 209 | 76.0 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 2019 | 73.4 | 1820 | 73.5 | 199 | 72.4 |

| Black | 617 | 22.4 | 547 | 22.1 | 70 | 25.5 |

| Other1 | 116 | 4.2 | 110 | 4.4 | 6 | 2.2 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1380 | 50.1 | 1254 | 50.6 | 126 | 45.8 |

| Unmarried2 | 1372 | 49.9 | 1223 | 49.4 | 149 | 54.2 |

| Grade | ||||||

| Well differentiated | 257 | 9.3 | 237 | 9.6 | 20 | 7.3 |

| Moderately differentiated | 1568 | 57.0 | 1426 | 57.6 | 142 | 51.6 |

| Poorly differentiated | 888 | 32.3 | 794 | 32.1 | 94 | 34.2 |

| Undifferentiated | 39 | 1.4 | 20 | 0.8 | 19 | 6.9 |

| Site | ||||||

| Glottis | 855 | 31.1 | 773 | 31.2 | 82 | 29.8 |

| Supraglottis | 1576 | 57.3 | 1418 | 57.2 | 158 | 57.5 |

| Subglottis | 93 | 3.4 | 84 | 3.4 | 9 | 3.3 |

| Overlapping lesion | 228 | 8.3 | 202 | 8.2 | 26 | 9.5 |

| Cancer-directed surgery | ||||||

| No cancer-directed surgery | 85 | 3.1 | 70 | 2.8 | 15 | 5.5 |

| Local excision/destruction3 | 459 | 16.7 | 403 | 16.3 | 56 | 20.4 |

| Total/Radical laryngectomy | 2208 | 80.2 | 2004 | 80.9 | 204 | 74.2 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||||

| No radiotherapy | 838 | 30.5 | 751 | 30.3 | 87 | 31.6 |

| Receive radiotherapy | 1914 | 69.5 | 1726 | 69.7 | 188 | 68.4 |

| AJCC T status | ||||||

| T1 | 322 | 11.7 | 288 | 11.6 | 34 | 12.4 |

| T2 | 755 | 27.4 | 700 | 28.3 | 55 | 20.0 |

| T3 | 404 | 14.7 | 346 | 14.0 | 58 | 21.1 |

| T4a | 1175 | 42.7 | 1049 | 42.3 | 126 | 45.8 |

| T4b | 98 | 3.6 | 94 | 3.8 | 4 | 1.5 |

| AJCC N status | ||||||

| N0 | 1300 | 47.2 | 1165 | 47.0 | 135 | 49.1 |

| N1 | 420 | 15.3 | 372 | 15.0 | 48 | 17.5 |

| N2a | 119 | 4.3 | 108 | 4.4 | 11 | 4.0 |

| N2b | 573 | 20.8 | 534 | 21.6 | 39 | 14.2 |

| N2c | 292 | 10.6 | 255 | 10.3 | 37 | 13.5 |

| N3 | 48 | 1.7 | 43 | 1.7 | 5 | 1.8 |

| AJCC M status | ||||||

| M0 | 2691 | 97.8 | 2424 | 97.9 | 267 | 97.1 |

| M1 | 61 | 2.2 | 53 | 2.1 | 8 | 2.9 |

| Continuous variables | ||||||

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||

| Median (Range) | 60 (24–96) | 60 (24–96) | 60 (25–85) | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||||

| Median (Range) | 3.0 (0.1–23.0) | 3.0 (0.1–23.0) | 3.1 (0.2–10.0) | |||

| Number of LN examined | ||||||

| Median (Range) | 25 (1–89) | 25 (1–89) | 27 (1–89) | |||

| Number of positive LNs | ||||||

| Median (Range) | 1 (0–58) | 1 (0–58) | 1 (0–17) | |||

| Lymph node ratio | ||||||

| Median (Range) | 0.019 (0–1) | 0.019 (0–1) | 0.017 (0–1) | |||

1Including American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian/Pacific Islander.

2Including patients who are never married, divorced, separated or widowed.

3Local destruction includes photodynamic therapy, electrocautery, cryosurgery, laser ablation, etc.

SEER 1988–2008.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of the validation cohort were also listed in Table 1. Follow-up time ranged from 1 to 189 months (Median: 50) and 205 (74.5%) patients had died before the last follow-up, in which 132 (48.0%) were due to cancer.

Optimal cutoff values of LNR and Tumor size

In order to construct nomograms, we need to stratify the continuous variables in Table 1 into several categories. X-tile program, a practical tool for cut-point optimization, was used to determine the optimal cutoff values for tumor size and LNR by the minimal P-value approach [17].

Just as the method of Imre’s and Ryu’s studies, when calculating cutoff values for LNR, we only included patients with positive lymph nodes (N+) [18, 19]. Based on overall survival, the program identified optimal LNR cutoff point for node-positive patients as 0.14, the optimal tumor size cutoffs for the entire training cohort (including both node-negative and node-positive patients) were 3.0 and 4.0 cm (Figures 2 and 3). While based on cancer-specific survival which was another primary endpoint of our interest, X-tile identified optimal LNR cut-point for node-positive patients as 0.12, while the optimal tumor size cutoffs for the entire cohort were 3.0 and 3.9 cm (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). For the purpose of a unified standard, we adopted optimal cutoffs of LNR and tumor size based on OS, as X-tile utilized Kaplan-Meier method for analysis, which was more suitable for estimating overall survival.

Figure 2. X-tile analysis identifying optimal LNR cutoffs based on OS.

X-tile analysis was conducted on patients with positive lymph nodes in the training cohort (n = 1312), these 1312 patients in the training cohort was equally divided into training (n = 656) and validation sets (n = 656). X-tile plots of training sets are shown in the left panels, the “lock” symbol in the left panel means optimal cutoffs have been determined, a histogram (middle panels) and a Kaplan-Meier plot (right panels) was performed based on these cutoffs. P values were determined by using the cut-point defined in the training set and applying it to the validation set. Optimal LNR cut-point was determined as 0.14 based on OS (χ2 = 55.675, P < 0.001). As the X axis could only show one decimal place, so we added a text annotation “Cutoff value = 0.14” in the middle panel.

Figure 3. X-tile analysis identifying optimal tumor size cutoffs based on OS.

X-tile analysis was conducted on the training cohort of our study (n = 2477), these 2477 patients in the training cohort was equally divided into training (n = 1238) and validation sets (n = 1239). X-tile plots of training sets are shown in the left panels, the “lock” symbol in the left panel means optimal cutoffs have been determined, a histogram (middle panels) and a Kaplan-Meier plot (right panels) was performed based on these cutoffs. P values were determined by using the cut-point defined in the training set and applying it to the validation set. Optimal tumor size cut-points were identified as 30mm and 40mm based on OS (χ2 = 59.83, P < 0.001).

Consequently, the entire training cohort was divided into ≤ 3 cm, 3.1–4 cm and > 4 cm groups by tumor size. Those node-positive patients were divided into 0.01–0.14 group and > 0.14 group by LNR. When combined with node-negative patients, the entire training cohort was divided into LNR = 0, LNR 0.01–0.14 and LNR > 0.14 groups. Patients’ age at diagnosis was also stratified by ten-year age groups. Table 2 summarized baseline information on age, LNR and tumor size after categorization.

Table 2. Baseline information on age, tumor size and LNR after setting up optimal cutoff values.

| Characteristic | All patients | Training cohort | Validation cohort | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2752 | n = 2477 | n = 275 | ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||

| < 45 | 190 | 6.9 | 171 | 6.9 | 19 | 6.9 |

| 45–54 | 617 | 22.4 | 560 | 22.6 | 57 | 20.7 |

| 55–64 | 1039 | 37.8 | 929 | 37.5 | 110 | 40.0 |

| 65–74 | 676 | 24.6 | 607 | 24.5 | 69 | 25.1 |

| ≥ 75 | 230 | 8.4 | 210 | 8.5 | 20 | 7.3 |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||||

| ≤ 3 | 1475 | 53.6 | 1320 | 53.3 | 155 | 56.4 |

| 3.1–4 | 701 | 25.5 | 637 | 25.7 | 64 | 23.3 |

| > 4 | 576 | 20.9 | 520 | 21.0 | 56 | 20.4 |

| Lymph node ratio | ||||||

| 0 | 1310 | 47.6 | 1175 | 47.4 | 135 | 49.1 |

| 0.01–0.14 | 889 | 32.3 | 805 | 32.5 | 84 | 30.5 |

| > 0.14 | 553 | 20.1 | 497 | 20.1 | 56 | 20.4 |

SEER 1988–2008.

Factors associated with OS in the training cohort

Of the 2477 patients in the training cohort, in the univariate analysis, all the demographics and tumor characteristics in Table 1 were associated with OS (P < 0.05) and no multicollinearity was observed among the variables (all VIFs < 5). These variables were included in the multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model. Furtherly in the multivariate analysis, all the included characteristics remained significant for OS according to Wald test (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall survival in the training cohort.

| Characteristic | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | HR (95%CI) | P | P (Wald test) | |

| Age at diagnosis | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| < 45 | 0.314 (0.244–0.405) | < 0.001 | ||

| 45–54 | 0.433 (0.361–0.520) | < 0.001 | ||

| 55–64 | 0.556 (0.470–0.657) | < 0.001 | ||

| 65–74 | 0.781 (0.659–0.926) | 0.004 | ||

| ≥75 | Reference | |||

| Gender | < 0.001 | 0.038 | ||

| Female | Reference | |||

| Male | 1.132 (1.007–1.272) | 0.038 | ||

| Race | 0.020 | 0.005 | ||

| White | Reference | |||

| Black | 1.125 (1.005–1.259) | 0.040 | ||

| Other | 0.757 (0.597–0.959) | 0.021 | ||

| Marital status | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Married | Reference | |||

| Unmarried | 1.294 (1.176–1.423) | < 0.001 | ||

| Grade | < 0.001 | 0.043 | ||

| Well differentiated | Reference | |||

| Moderately differentiated | 1.020 (0.861–1.208) | 0.804 | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 1.134 (1.037–1.249) | 0.015 | ||

| Undifferentiated | 1.685 (1.017–2.791) | 0.043 | ||

| Site | 0.011 | 0.040 | ||

| Glottis | Reference | |||

| Supraglottis | 1.124 (0.936–1.351) | 0.211 | ||

| Subglottis | 1.186 (0.992–1.417) | 0.056 | ||

| Overlapping lesion | 1.301 (1.180–1.419) | < 0.001 | ||

| Cancer-directed surgery | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| No cancer-directed surgery | Reference | |||

| Local excision/destruction | 0.599 (0.444–0.808) | 0.001 | ||

| Total/Radical laryngectomy | 0.770 (0.581–1.020) | 0.069 | ||

| Radiotherapy | 0.005 | < 0.001 | ||

| No radiotherapy | Reference | |||

| Receive radiotherapy | 0.790 (0.706–0.884) | < 0.001 | ||

| AJCC T status | < 0.001 | 0.031 | ||

| T1 | Reference | |||

| T2 | 1.124 (0.949–1.330) | 0.175 | ||

| T3 | 1.154 (0.945–1.408) | 0.161 | ||

| T4a | 1.288 (1.083–1.531) | 0.004 | ||

| T4b | 1.338 (0.991–1.806) | 0.057 | ||

| AJCC N status | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| N0 | Reference | |||

| N1 | 1.222 (0.562–2.649) | 0.612 | ||

| N2a | 1.732 (0.786–3.816) | 0.173 | ||

| N2b | 1.554 (0.721–3.352) | 0.261 | ||

| N2c | 1.969 (0.913–4.246) | 0.084 | ||

| N3 | 2.044 (0.902–4.633) | 0.087 | ||

| AJCC M status | < 0.001 | |||

| M0 | Reference | |||

| M1 | 1.931 (1.364–2.734) | < 0.001 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | < 0.001 | 0.005 | ||

| ≤ 3 | Reference | |||

| 3.1–4 | 1.171 (1.046–1.310) | 0.006 | ||

| > 4 | 1.177 (1.041–1.331) | 0.009 | ||

| Lymph node ratio | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | Reference | |||

| 0.01–0.14 | 1.137 (0.530–2.441) | 0.741 | ||

| > 0.14 | 1.606 (0.750–3.439) | 0.223 | ||

Abbreviations: HR: Hazard Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval.

1Including American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian/Pacific Islander.

2Including patients who are never married, divorced, separated or widowed.

3Local destruction includes photodynamic therapy, electrocautery, cryosurgery, laser ablation, etc.

(n = 2477).

Cancer-specific mortality, competing risks and multivariate analysis for CSS

Cumulative incidence function (CIF), which was an unbiased way for analyzing cause-specific incidence when competing risk exists, was used to estimate cancer-specific mortality (CSM) and deaths resulting from other causes (DROC), as appropriate. The 3- and 5-year cumulative incidences of cancer-specific mortality (CICSM) were 30.1% and 37.2%, respectively, and the 3- and 5-year cumulative incidences of DROC were 6.2% and 11.3%, respectively. Gray’s test showed that all the variables, except race, proved to be associated with CSM (P < 0.05). We also observed that in patients of each subgroup except those ≥ 75 years old, CSM estimated by Kaplan-Meier method was quite close to the results by CIF, indicating that the low incidence of competing risks played a very slight interfering role in the Kaplan-Meier estimates for CSS (Table 4).

Table 4. 3- and 5-year cumulative incidences of death in the training cohort.

| Characteristic | Cumulative Incidence of CSM | CSM by Kaplan-Meier estimates | Cumulative Incidence of DROC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-year | 5-year | P | 3-year | 5-year | 3-year | 5-year | P | |

| All patients | 30.1% | 37.2% | 31.1% | 39.5% | 6.2% | 11.3% | ||

| Age at diagnosis | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| < 45 | 23.2% | 29.4% | 23.9% | 30.4% | 3.8% | 6.8% | ||

| 45–54 | 27.6% | 33.9% | 28.1% | 35.1% | 3.4% | 7.7% | ||

| 55–64 | 29.6% | 36.2% | 30.4% | 37.9% | 4.8% | 9.1% | ||

| 65–74 | 32.6% | 41.2% | 34.1% | 44.7% | 8.7% | 15.3% | ||

| ≥75 | 37.7% | 46.3% | 40.9% | 52.9% | 15.4% | 23.0% | ||

| Gender | 0.035 | 0.376 | ||||||

| Female | 24.6% | 33.9% | 25.6% | 36.3% | 7.2% | 9.8% | ||

| Male | 31.4% | 38.0% | 32.5% | 40.2% | 6.0% | 11.7% | ||

| Race | 0.160 | 0.258 | ||||||

| White | 29.4% | 36.4% | 30.4% | 38.5% | 6.4% | 11.4% | ||

| Black | 31.9% | 40.0% | 33.4% | 42.8% | 6.8% | 11.9% | ||

| Other | 31.5% | 37.2% | 31.9% | 38.0% | 1.9% | 6.5% | ||

| Marital status | 0.008 | 0.046 | ||||||

| Married | 26.5% | 33.7% | 27.2% | 35.5% | 5.5% | 10.0% | ||

| Unmarried | 33.7% | 40.8% | 35.2% | 43.6% | 7.1% | 12.8% | ||

| Grade | < 0.001 | 0.018 | ||||||

| Well differentiated | 20.1% | 24.8% | 20.8% | 26.3% | 7.5% | 14.4% | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 28.1% | 35.6% | 29.0% | 37.6% | 5.5% | 10.2% | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 36.3% | 43.6% | 37.9% | 46.7% | 7.2% | 12.2% | ||

| Undifferentiated | 40.4% | 45.5% | 40.8% | 48.2% | 7.3% | 22.3% | ||

| Site | 0.016 | 0.388 | ||||||

| Glottis | 26.3% | 32.9% | 27.2% | 34.8% | 7.2% | 11.4% | ||

| Supraglottis | 31.2% | 38.5% | 32.6% | 41.2% | 7.6% | 12.0% | ||

| Subglottis | 33.8% | 40.3% | 33.9% | 41.1% | 3.6% | 8.1% | ||

| Overlapping lesion | 36.6% | 47.5% | 36.5% | 48.5% | 1.4% | 8.4% | ||

| Cancer-directed surgery | < 0.001 | 0.324 | ||||||

| No cancer-directed surgery | 46.2% | 57.9% | 47.4% | 62.3% | 5.9% | 11.6% | ||

| Local excision/destruction | 20.9% | 28.2% | 21.4% | 29.5% | 5.0% | 8.3% | ||

| Total/Radical laryngectomy | 31.3% | 38.3% | 32.5% | 40.7% | 6.6% | 11.9% | ||

| Radiotherapy | < 0.001 | 0.041 | ||||||

| No radiotherapy | 26.8% | 32.3% | 28.1% | 34.6% | 7.9% | 13.5% | ||

| Receive radiotherapy | 31.5% | 39.4% | 32.4% | 41.5% | 5.6% | 10.4% | ||

| AJCC T status | < 0.001 | 0.071 | ||||||

| T1 | 21.0% | 26.9% | 21.6% | 28.3% | 6.0% | 9.5% | ||

| T2 | 26.1% | 33.0% | 27.5% | 35.7% | 8.3% | 13.9% | ||

| T3 | 24.4% | 33.5% | 24.7% | 35.0% | 4.2% | 9.3% | ||

| T4a | 34.9% | 41.8% | 36.1% | 44.0% | 5.8% | 11.2% | ||

| T4b | 53.7% | 63.4% | 56.2% | 67.1% | 4.7% | 6.9% | ||

| AJCC N status | < 0.001 | 0.002 | ||||||

| N0 | 16.3% | 23.3% | 16.8% | 24.2% | 4.6% | 10.0% | ||

| N1 | 29.1% | 35.9% | 30.6% | 38.8% | 8.1% | 14.6% | ||

| N2a | 42.2% | 48.8% | 46.4% | 54.5% | 11.2% | 15.0% | ||

| N2b | 43.3% | 51.2% | 45.5% | 54.9% | 7.1% | 11.4% | ||

| N2c | 55.7% | 64.1% | 59.5% | 69.5% | 7.1% | 11.1% | ||

| N3 | 51.7% | 63.3% | 54.5% | 68.4% | 8.9% | 11.3% | ||

| AJCC M status | < 0.001 | 0.187 | ||||||

| M0 | 29.3% | 36.5% | 30.3% | 38.7% | 6.3% | 11.4% | ||

| M1 | 67.7% | 71.6% | 72.7% | 77.3% | 6.9% | 6.9% | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | < 0.001 | 0.425 | ||||||

| ≤ 3 | 24.8% | 32.6% | 22.5% | 31.0% | 5.3% | 10.2% | ||

| 3.1–4 | 33.3% | 39.9% | 30.7% | 39.3% | 7.1% | 13.1% | ||

| > 4 | 39.5% | 45.7% | 41.5% | 48.9% | 7.9% | 12.2% | ||

| Lymph node ratio | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 16.5% | 23.5% | 17.0% | 24.5% | 4.6% | 10.0% | ||

| 0.01–0.14 | 33.0% | 41.4% | 34.6% | 44.0% | 9.1% | 14.2% | ||

| > 0.14 | 54.9% | 61.5% | 57.2% | 65.1% | 5.9% | 9.8% | ||

Abbreviations: CSM: cancer-specific mortality; DROC: death resulting from other causes.

P*: P value calculated by Gray’s test.

(n = 2477).

Owing to the limited interference effect of competing risks, Cox proportional hazards model rather than sub-distribution competing risks model was used to conduct multivariate analysis for CSS and build nomograms (Reasons for choosing Cox model was discussed furtherly in Discussion section). Furtherly, all the significant variables in the univariate test in Table 4 were confirmed to be independent prognostic factors for CSS in multivariate analysis (Table 5).

Table 5. Multivariate analysis of cancer-specific survival in the training cohort.

| Characteristic | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P value | P (Wald test) | |

| Age at diagnosis | < 0.001 | ||

| < 45 | 0.448 (0.324–0.619) | < 0.001 | |

| 45–54 | 0.612 (0.485–0.772) | < 0.001 | |

| 55–64 | 0.712 (0.573–0.885) | 0.002 | |

| 65–74 | 0.908 (0.726–1.134) | 0.394 | |

| ≥75 | Reference | ||

| Gender | 0.046 | ||

| Female | Reference | ||

| Male | 1.152 (1.005–1.326) | 0.046 | |

| Site | 0.041 | ||

| Glottis | Reference | ||

| Supraglottis | 1.042 (0.829–1.309) | 0.726 | |

| Subglottis | 1.058 (0.849–1.318) | 0.617 | |

| Overlapping lesion | 1.291 (1.174–1.420) | < 0.001 | |

| Marital status | 0.001 | ||

| Married | Reference | ||

| Unmarried | 1.214 (1.077–1.368) | 0.001 | |

| Grade | 0.036 | ||

| Well differentiated | Reference | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 1.253 (0.979–1.602) | 0.073 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 1.385 (1.070–1.792) | 0.013 | |

| Undifferentiated | 1.730 (0.862–3.474) | 0.123 | |

| Cancer-directed surgery | 0.005 | ||

| No cancer-directed surgery | Reference | ||

| Local excision/destruction | 0.576 (0.406–0.817) | 0.002 | |

| Total/Radical laryngectomy | 0.706 (0.511–0.977) | 0.035 | |

| Radiotherapy | 0.001 | ||

| No radiotherapy | Reference | ||

| Receive radiotherapy | 0.780 (0.674–0.902) | 0.001 | |

| AJCC T status | 0.001 | ||

| T1 | Reference | ||

| T2 | 1.205 (0.958–1.515) | 0.111 | |

| T3 | 1.388 (1.068–1.804) | 0.014 | |

| T4a | 1.517 (1.202–1.914) | < 0.001 | |

| T4b | 1.713 (1.191–2.466) | 0.004 | |

| AJCC N status | < 0.001 | ||

| N0 | Reference | ||

| N1 | 1.259 (0.502–3.155) | 0.623 | |

| N2a | 2.128 (0.837–5.409) | 0.113 | |

| N2b | 1.757 (0.706–4.373) | 0.226 | |

| N2c | 2.414 (0.970–6.004) | 0.058 | |

| N3 | 2.375 (0.903–6.250) | 0.081 | |

| AJCC M status | < 0.001 | ||

| M0 | Reference | ||

| M1 | 2.054 (1.389–3.038) | < 0.001 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.045 | ||

| ≤ 3 | Reference | ||

| 3.1–4 | 1.099 (0.952–1.270) | 0.198 | |

| > 4 | 1.191 (1.023–1.386) | 0.025 | |

| Lymph node ratio | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | Reference | ||

| 0.01–0.14 | 1.159 (0.469–2.862) | 0.749 | |

| > 0.14 | 1.850 (0.751–4.555) | 0.181 | |

Abbreviations: HR: Hazard Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval. (n = 2477).

Establishment and validation of the nomograms

By a backward stepwise method based on the smallest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), all the significant factors in multivariate analysis were incorporated to develop nomograms predicting 3- and 5-year OS and CSS (Figure 4). Detailed scores of each nomogram predictor were presented in Table 6.

Figure 4.

Nomograms estimating 3- and 5-year (A) overall survival (B) cancer-specific survival of LSCC patients treated with neck dissection. Instructions of the nomograms: First, each characteristic of an individual patient is located on the corresponding axis, we can draw a vertical line from that variable to the points scale to obtain its point (or look up Table 6). Second, we need to add up the points of each characteristic to obtain a total point, then draw a vertical line from the Total Points Scale to the 3- and 5-year OS or CSS scale to get the estimated probabilities of survival.

Table 6. Detailed scores of each predictor in the nomograms.

| Characteristic | OS nomogram | CSS nomogram |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| < 45 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 45–54 | 2.8 | 3.5 |

| 55–64 | 4.9 | 5.3 |

| 65–74 | 7.9 | 8.0 |

| ≥ 75 | 10.0 | 9.1 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Male | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| Race | ||

| White | 2.4 | |

| Black | 3.4 | Not included |

| Other | 0.0 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Unmarried | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Grade | ||

| Well differentiated | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Moderately differentiated | 0.2 | 2.5 |

| Poorly differentiated | 1.1 | 3.7 |

| Undifferentiated | 4.5 | 6.2 |

| Site | ||

| Glottis | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Supraglottis | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Subglottis | 1.5 | 0.6 |

| Overlapping lesion | 2.3 | 2.9 |

| Cancer-directed surgery | ||

| No cancer-directed surgery | 4.4 | 6.3 |

| Local excision/destruction | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total/Radical laryngectomy | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| No radiotherapy | 2.1 | 2.8 |

| Receive radiotherapy | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| AJCC T status | ||

| T1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| T2 | 1.0 | 2.1 |

| T3 | 1.2 | 3.7 |

| T4a | 2.2 | 4.7 |

| T4b | 2.5 | 6.1 |

| AJCC N status | ||

| N0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| N1 | 1.7 | 2.6 |

| N2a | 4.8 | 8.6 |

| N2b | 3.8 | 6.4 |

| N2c | 5.9 | 10.0 |

| N3 | 6.2 | 9.8 |

| AJCC M status | ||

| M0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| M1 | 5.9 | 8.3 |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||

| ≤ 3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 3.1–4 | 1.4 | 1.1 |

| > 4 | 1.5 | 2.0 |

| Lymph node ratio | ||

| 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.01–0.14 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| > 0.14 | 4.1 | 7.0 |

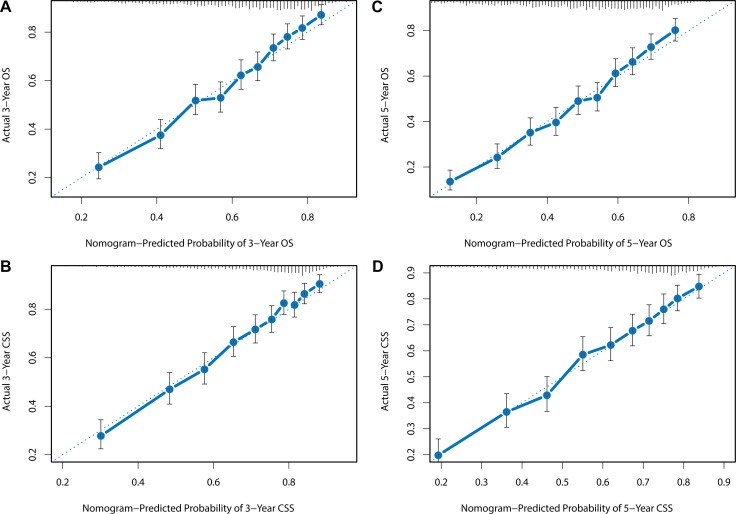

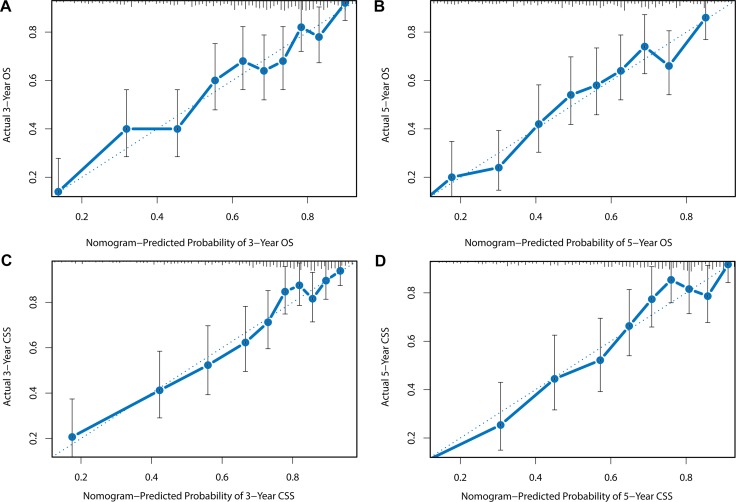

The nomograms were validated by bootstrap resampling internally and externally. Harrell’s Concordance-indexes (C-index), as an indicator of predictive abilities, were compared among nomogram models, no-LNR models (including all the variables in the nomograms except LNR) and TNM models (including only TNM status). As shown in Table 7, in the internal validation via training cohort, the nomogram models possessed higher C-indexes (OS: 0.713; CSS: 0.725) than no-LNR model (OS: 0.703; CSS: 0.713) and TNM model (OS: 0.667; CSS: 0.688). In the validation cohort for external validation, similarly, nomogram model (OS: 0.704; CSS: 0.709) still demonstrated superiority over no-LNR model (OS: 0.690; CSS: 0.693) and TNM model (OS: 0.658; CSS: 0.672). C-index and AIC of each model were presented in Table 7. Internal and external calibration plots for OS and CSS also showed good agreement between nomogram prediction and observed outcomes (Figures 5 and 6).

Table 7. Predictive ability of different prediction models.

| Predicting models | Harrell’s C-index | AIC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal validation | Overall survival | ||

| TNM classification | 0.667 | 26193.53 | |

| No-LNR model | 0.703 | 25971.86 | |

| Nomogram model | 0.713 | 25946.89 | |

| Cancer-specific survival | |||

| TNM classification | 0.688 | 16491.48 | |

| No-LNR model | 0.713 | 16419.76 | |

| Nomogram model | 0.725 | 16385.39 | |

| External validation | Overall survival | ||

| TNM classification | 0.658 | 6096.82 | |

| No-LNR model | 0.690 | 6075.84 | |

| Nomogram model | 0.704 | 6052.44 | |

| Cancer-specific survival | |||

| TNM classification | 0.672 | 3948.56 | |

| No-LNR model | 0.693 | 3947.39 | |

| Nomogram model | 0.709 | 3921.78 | |

Abbreviations: AIC: Akaike Information Criterion.

SEER 1988–2008.

Figure 5.

Internal calibration plots for (A) 3-year OS, (B) 5-year OS, (C) 3-year CSS, (D) 5-year CSS. The diagonal dashed line in each plot represents perfect match between nomogram prediction (x-axis) and actual observed survival (y-axis). The training cohort was divided into 10 groups with equal sample size for internal validation. Closer distances between the fit line and the diagonal line indicate higher prediction accuracy.

Figure 6.

External calibration plots for (A) 3-year OS, (B) 5-year OS, (C) 3-year CSS, (D) 5-year CSS. The diagonal dashed line in each plot represents perfect match between nomogram prediction (X-axis) and actual observed survival (Y-axis). The validation cohort was divided into 10 groups with equal sample size for external validation. Closer distances between the fit line and the diagonal line indicate higher prediction accuracy.

It’s easy and comprehensible to predict survival by nomograms which possess a user-friendly interface. Based on an individual patient’s information, we can look up Table 6 to obtain the point of each prognostic factor, and then add up the points and predict survival by the corresponding survival probabilities of the total points. Take this example, for a married 60 year-old white man, he was diagnosed with well-differentiated T4aN1M0 glottis squamous cell carcinoma with a primary tumor of 2.5 cm in greatest diameter, he didn’t undergo cancer-directed surgery but received radiotherapy, neck dissection showed 5% of examined lymph nodes had signs of metastasis. In summary, he got 17.8 and 22.2 points in OS and CSS nomograms, respectively, corresponding to an estimated 56% 5-year OS rate and 65% 5-year CSS rate. In the same manner, we could also predict a relatively short-term 3-year survival rate with the nomograms.

DISCUSSION

Cancer prognosis has proved to be closely related to different aspects of factors, such as demographics, tumor characteristics and treatment conditions. AJCC TNM status, which has been the most widely used system for outcome estimation, however, is not sufficient to satisfy current need. Nomogram, considered to be a graphical depiction of prediction model, gives oncologists an opportunity to combine different tumor prognostic factors together, thus to help us assess the risk of failure more precisely [20, 21].

Regardless of surgery or radiotherapy as treatment for primary tumor, neck dissection is recommended for LSCC patients with potential node involvement [7]. LNR information obtained from neck dissection could also help improve our understanding of node metastasis in depth. Published nomograms developed in Ju’s and Shen’s studies focused on prognosis of squamous cell carcinoma of all sites of head and neck based on SEER database with large sample size, however, patients included in their studies didn’t necessarily need to receive neck dissection thus information on LNR of these patients was not available to be incorporated into the nomograms. Moreover, as characteristics of tumors from different sites of head and neck may vary greatly, it might not be most appropriate to use the same predictive tool to estimate prognosis of different head and neck cancer. When we predicted survival of LSCC patients treated with neck dissection, for these reasons above, the nomograms in Ju’s and Shen’s researches were not able to achieve the best predictive performance [22, 23]. Consequently, in terms of necessity, we established more comprehensive nomograms to predict survival of LSCC patients who underwent neck dissection and they proved to be more accurate than previous models as well as conventional TNM staging systems. Since SEER program is comprised of 18 cancer registries covering thousands of hospitals and nearly 30% of total population across the nation, heterogeneity of the data allowed the models to be broadly used for decision-making in clinical practice.

Through univariate Log-rank test and multivariate Cox analysis, independent predictive factors for OS were identified. When we selected the variables to build nomograms, backward stepwise methods were used to determine the smallest AIC value in order to minimize the information loss. With regard to CSS, according to Fine and Gray, an overestimation of failure is expected due to the existing competing risks when Kaplan-Meier and Cox proportional hazards analysis were applied [24]. However, in the comparison between Kaplan-Meier estimates and the CIF means, very close CSM results suggested the relative low incidence of competing risks in our study might not be a critical consideration. In view of Cox models’ high interpretability by nomogram and comparability with previous literatures, just as the method of Valentini’s research and some other prior studies [25–27], we still adopted a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model for CSS analysis.

In our study, we validated some clinicopathological factors as important prognostic indicators for both OS and CSS in the multivariate analysis, including sociodemographic factors like age at diagnosis, gender, marital status; tumor characteristics such as primary site, grade, TNM status, tumor size and lymph node ratio; as well as treatment conditions like surgery and radiotherapy. As shown in our nomograms, age at diagnosis revealed strong impact on OS and CSS. In average, compared with a patient less than 45 years old, 5-year OS and CSS rates were reduced by 35% and 20% for those over 75, even if they had the same exposure to other risk factors. Age was also proved to be an important predictive and prognostic factor in some previous studies. Ampil et al confirmed that age was a prognostic factor in T4 laryngeal carcinoma [28], Kowalski et al also proved age as an important prognostic factor in T3N0-1 glottic or transglottic cancer [29]. In another study of 945 cases in Sweden, Reizenstein et al reported that elderly laryngeal cancer patients received higher proportion of palliative care rather than radical treatment and thus to have a much higher never-free-from-tumor rate, which might be a potential reason for their increased risk of mortality [30]. In our study, male patients were found to have a significantly greater risk of both overall and cancer-specific mortality compared with female. It has been reported by Shan SJ et al that male head and neck cancer patients were relatively more reluctant to undergo follow-up screening than female [31]. Besides, according to Sharp et al ’s research based on a large national cancer database in Ireland, smoking at diagnosis is an independent prognostic factor for cancer-specific survival in head and neck cancer and proportion of current smokers at diagnosis in male patients was much higher than in female [32]. These reasons could partly explain why gender was an independent prognostic and predictive factor for cancer-specific survival. According to our research, marriage demonstrated a significant protective effect, relationship between marital status and cancer outcomes was also certified in many cancer types [33–36], the role of spousal support in behavior change, psychological regulation and treatment compliance might be potential mechanisms [37, 38]. Previous literatures reported that African American people were generally in a lower social class, and possessed worse socioeconomic conditions and living habits, thus to have a higher risk for comorbidities, this could reasonably explain why race was only statistically significantly associated with OS, but not CSS (P = 0.160) in the univariate analysis of our study [39–43]. It’s also noteworthy that in the CSS nomogram, N staging had the greatest effect on CSS and in particular, LNR made an even bigger contribution than T categories to both OS and CSS, indicating that nodal status had a stronger influence on prognosis than status of primary tumor, which was in consistence with the opinion by Ferlito et al [5].

Inevitably, potential limitations in our study should be taken into consideration. First, important therapies like chemotherapy were not accessible in SEER database and SEER no longer recorded the type or regions of neck dissection after 2003, besides, extracapsular spread (ECS) as an important prognostic factor for laryngeal cancer patients with positive lymph nodes, wasn’t recorded in SEER database as well. Consequently these factors couldn’t be recruited in the nomograms. Second, during the 20 years between 1988 and 2008, compared to all the LSCC patients registered in SEER database, those who underwent neck dissection were relatively small (less than 3000), causing a lack of patients in some subgroups, like there were only 20 patients in undifferentiated grade subgroup, which probably reduced accuracy. Third, SEER didn’t collect information on some important common-recognized laboratory prognostic indices like SCC-Ag expression, EGFR or VEGF mutation [44, 45], they could furtherly improve the predictive performance if incorporated. Fourth, in addition to LNR, positive nodes count and log odds of positive lymph nodes (LODDS) were also potential prognostic indicators provided by neck dissection, further comparisons of their prognostic capabilities were required. Moreover, the nomograms should be validated by prospective research on account of the retrospective nature of our study.

In conclusion, we constructed and validated nomograms estimating overall and cancer-specific survival of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma patients treated with neck dissection using a large, population-based dataset. These nomograms exhibited high degree of applicability and accuracy, outperforming predictive models in previous literatures as well as TNM staging system. By these predictive tools, it will be more effective to assist clinicians in identifying patients with high risk of mortality and making more precise survival evaluation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source and inclusion criteria

All the data was obtained from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, which collects information of cancer patients in 18 registries, covering approximately 30% of total U.S population. The database includes some important demographic, diagnostic and treatment information of cancer patients, such as primary sites, morphology, stage, surgery, radiotherapy, grade and patients’ vital status. (http://www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat software (Version 8.3.2) was used to extract information from the database.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) Diagnosed with LSCC as its first and only malignancy. 2) The ICD-O-3 site codes were limited to C32.0 (glottis), C32.1 (supraglottis), C32.2 (subglottis), and C32.8 (overlapping lesion) according to SEER classification. It’s worth noting that C32.3 (Laryngeal cartilage) and C32.9 (NOS) were not included because the number of eligible patients was too small (less than 10). 3) Histological type was limited to squamous cell carcinoma (8052, 8070-8078, 8083-8084, 8094, 8560) according to ICD-O-3 histological codes, as appropriate. 4) Underwent neck dissection with definite counts of examined and positive lymph nodes. 5) Diagnosed between 1988 and 2008 to ensure an adequate follow-up length, as the follow-up cutoff date of currently available SEER data was 12/31/2013. 6) Known survival months after diagnosis and known cause of death. 7) Older than 18 years old. 8) Definite information on race, TNM status, grade, surgery, radiotherapy and tumor size. 9) Active follow-up. 10) Excluded if the diagnosis was obtained by death certificate or autopsy only.

Statistical analysis for OS and CSS

The entire group of enrolled patients (n = 2752) was randomly divided into a training cohort (n = 2477) and a validation cohort (n = 275) in order to develop and validate nomograms. Patients’ 13 important clinicopathological factors including age at diagnosis, race, gender, marital status, site, grade, TNM status, surgery, radiotherapy, tumor size and lymph node ratio were used to conduct the univariate and multivariate analysis. Optimal cutoffs of tumor size and LNR were determined by X-tile program. Age at diagnosis was grouped by ten years, we combined patients less than 45 years old into one single group because only 15 patients were less than 35, similarly, those older than 75 years old were put into the same group as only 10 individuals in the training cohort were beyond 85.

One of our primary endpoints of interest was OS, defined as the time from diagnosis to death from all possible causes, patients who were alive at the time of last follow-up were counted as censored observations. Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank tests were used to identify the significant factors associated with OS. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were constructed to analyze the independent effect of significant factors in the univariate log-rank test and present the hazard ratios of different variables.

Another primary endpoint of our interest was CSS, measured as the time from diagnosis to death attributed to LSCC, patients who were alive at the time of last follow-up were counted as censored observations. Cumulative incidence function (CIF) was used to evaluate cancer-specific mortality (CSM) and death resulting from other causes (DROC) which was regarded as competing risks. CIF results of CSM in each subgroup were compared with those calculated by Kaplan-Meier estimates, a Cox regression model was used to conduct multivariate analysis and build a nomogram as it was easy to interpret, compare and comprehend [25, 26].

Construction and validation of the nomograms

Nomograms were constructed based on Cox proportional hazards regression model to predict 3- and 5-year OS and CSS. To minimize the information loss, a backward stepwise method was used to recruit the independent prognostic factors into the construction of the nomograms until the minimal AIC value occurred.

Via the training cohort and the validation cohort, both internal and external nomogram validations were conducted. Performance of these predictive models was assessed by Harrell’s concordance-index (C-index), which was similar to area under curve (AUC), but proved to be more suitable for censored data [46]. C-index ranges from 0.5 to 1.0, 0.5 means total chance while 1.0 stands for prefect matching [12]. We also assessed the predictive performance by calibration plot, which was quantified by the comparison between nomogram-predicted survival with observed survival. Bootstraps with 1000 resample were used to conduct these activities [14].

Kaplan-Meier estimates, multivariate Cox regression and log-rank test were analyzed using statistical software IBM SPSS, version 22 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Cumulative incidence function (CIF), Gray’s test, nomogram construction, validation and calibration were performed in R version 3.3.1 (http://www.r-project.org/) with rms [47] and cmprsk [48] packages. All P values were two-sided and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Ethics statement

Our study was approved by Shanghai Cancer Center Ethical Committee. We do not need informed patient consent for the data released by the SEER database.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS FIGURES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND FUNDING

The authors of this study acknowledge the contribution of SEER database and the 18 registries supplying cancer research information.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions

XS and QHJ conceived and designed this study. XS and WPH performed the analyses. XS and WPH prepared all the tables and figures. XS wrote the main manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marur S, Forastiere AA. Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Update on Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerezo L, Millan I, Torre A, Aragon G, Otero J. Prognostic factors for survival and tumor control in cervical lymph node metastases from head and neck cancer. A multivariate study of 492 cases. Cancer. 1992;69:1224–1234. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820690526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfister DG, Spencer S, Brizel DM, Burtness B, Busse PM, Caudell JJ, Cmelak AJ, Colevas AD, Dunphy F, Eisele DW, Foote RL, Gilbert J, Gillison ML, et al. Head and Neck Cancers, Version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13:847–855. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferlito A, Rinaldo A, Silver CE, Robbins KT, Medina JE, Rodrigo JP, Shaha AR, Takes RP, Bradley PJ. Neck dissection for laryngeal cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.06.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferlito A, Partridge M, Brennan J, Hamakawa H. Lymph node micrometastases in head and neck cancer: a review. Acta Otolaryngol. 2001;121:660–665. doi: 10.1080/00016480152583584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Guidelines. Head and Neck Cancer. Version 1. 2016 Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck_blocks.pdf.

- 8.Reinisch S, Kruse A, Bredell M, Lubbers HT, Gander T, Lanzer M. Is lymph-node ratio a superior predictor than lymph node status for recurrence-free and overall survival in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma? Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1912–1918. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3634-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang YL, Li DS, Wang Y, Wang ZY, Ji QH. Lymph node ratio for postoperative staging of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma with lymph node metastasis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ampil FL, Caldito G, Ghali GE. Can the lymph node ratio predict outcome in head and neck cancer with single metastasis positive-node? Oral Oncol. 2014;50:e18–20. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen CC, Lin JC, Chen KW. Lymph node ratio as a prognostic factor in head and neck cancer patients. Radiat Oncol. 2015;10:181. doi: 10.1186/s13014-015-0490-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun W, Jiang YZ, Liu YR, Ma D, Shao ZM. Nomograms to estimate long-term overall survival and breast cancer-specific survival of patients with luminal breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:20496–20506. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao J, Yuan P, Wang L, Wang Y, Ma H, Yuan X, Lv W, Hu J. Clinical Nomogram for Predicting Survival of Esophageal Cancer Patients after Esophagectomy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26684. doi: 10.1038/srep26684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Li J, Xia Y, Gong R, Wang K, Yan Z, Wan X, Liu G, Wu D, Shi L, Lau W, Wu M, Shen F. Prognostic nomogram for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after partial hepatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1188–1195. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.5984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kutikov A, Egleston BL, Wong YN, Uzzo RG. Evaluating overall survival and competing risks of death in patients with localized renal cell carcinoma using a comprehensive nomogram. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:311–317. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egelmeer AG, Velazquez ER, de Jong JM, Oberije C, Geussens Y, Nuyts S, Kremer B, Rietveld D, Leemans CR, de Jong MC, Rasch C, Hoebers F, Homer J, et al. Development and validation of a nomogram for prediction of survival and local control in laryngeal carcinoma patients treated with radiotherapy alone: a cohort study based on 994 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2011;100:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camp RL, Dolled-Filhart M, Rimm DL. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7252–7259. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imre A, Pinar E, Dincer E, Ozkul Y, Aslan H, Songu M, Tatar B, Onur I, Ozturkcan S, Aladag I. Lymph Node Density in Node-Positive Laryngeal Carcinoma: Analysis of Prognostic Value for Survival. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155:797–804. doi: 10.1177/0194599816652371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryu IS, Roh JL, Cho KJ, Choi SH, Nam SY, Kim SY. Lymph node density as an independent predictor of cancer-specific mortality in patients with lymph node-positive laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma after laryngectomy. Head Neck. 2015;37:1319–1325. doi: 10.1002/hed.23750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balachandran VP, Gonen M, Smith JJ, DeMatteo RP. Nomograms in oncology: more than meets the eye. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e173–180. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71116-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shariat SF, Karakiewicz PI, Suardi N, Kattan MW. Comparison of nomograms with other methods for predicting outcomes in prostate cancer: a critical analysis of the literature. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4400–4407. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ju J, Wang J, Ma C, Li Y, Zhao Z, Gao T, Ni Q, Sun M. Nomograms predicting long-term overall survival and cancer-specific survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7:51059–51068. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen W, Sakamoto N, Yang L. Cancer-specific mortality and competing mortality in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a competing risk analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:264–271. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3951-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valentini V, van Stiphout RG, Lammering G, Gambacorta MA, Barba MC, Bebenek M, Bonnetain F, Bosset JF, Bujko K, Cionini L, Gerard JP, Rodel C, Sainato A, et al. Nomograms for predicting local recurrence, distant metastases, and overall survival for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer on the basis of European randomized clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3163–3172. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang ZY, Luo QF, Yin XW, Dai ZL, Basnet S, Ge HY. Nomograms to predict survival after colorectal cancer resection without preoperative therapy. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:658. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2684-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanrahan EO, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Giordano SH, Rouzier R, Broglio KR, Hortobagyi GN, Valero V. Overall survival and cause-specific mortality of patients with stage T1a,bN0M0 breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4952–4960. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ampil FL, Nathan CO, Caldito G, Lian TF, Aarstad RF, Krishnamsetty RM. Total laryngectomy and postoperative radiotherapy for T4 laryngeal cancer: a 14-year review. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kowalski LP, Batista MB, Santos CR, Scopel A, Salvajolli JV, Torloni H. Prognostic factors in T3,N0-1 glottic and transglottic carcinoma. A multifactorial study of 221 cases treated by surgery or radiotherapy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:77–82. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890130069011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reizenstein JA, Bergstrom SN, Holmberg L, Linder A, Ekman S, Blomquist E, Loden B, Holmqvist M, Hellstrom K, Nilsson CO, Brattstrom D, Bergqvist M. Impact of age at diagnosis on prognosis and treatment in laryngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2010;32:1062–1068. doi: 10.1002/hed.21292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shan SJ, Zahurak M, Khan Z, Califano JA. Reluctance to undergo follow-up screening for head and neck cancer is associated with income, gender, and tobacco use. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2010;72:266–271. doi: 10.1159/000310353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharp L, McDevitt J, Carsin AE, Brown C, Comber H. Smoking at diagnosis is an independent prognostic factor for cancer-specific survival in head and neck cancer: findings from a large, population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:2579–2590. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Q, Gan L, Liang L, Li X, Cai S. The influence of marital status on stage at diagnosis and survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:7339–7347. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J, Gan L, Wu Z, Yan S, Liu X, Guo W. The influence of marital status on the stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival of adult patients with gastric cancer: a population-based study. Oncotarget. 2017;8:22385–22405. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He XK, Lin ZH, Qian Y, Xia D, Jin P, Sun LM. Marital status and survival in patients with primary liver cancer. Oncotarget. 2016 Aug;5 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11066. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi RL, Qu N, Lu ZW, Liao T, Gao Y, Ji QH. The impact of marital status at diagnosis on cancer survival in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. Cancer Med. 2016;5:2145–2154. doi: 10.1002/cam4.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, Mendu ML, Koo S, Wilhite TJ, Graham PL, Choueiri TK, Hoffman KE, Martin NE, Hu JC, Nguyen PL. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3869–3876. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inverso G, Mahal BA, Aizer AA, Donoff RB, Chau NG, Haddad RI. Marital status and head and neck cancer outcomes. Cancer. 2015;121:1273–1278. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin JY, Truong MT. Racial disparities in laryngeal cancer treatment and outcome: A population-based analysis of 24,069 patients. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:1667–1674. doi: 10.1002/lary.25212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boen C. The role of socioeconomic factors in Black-White health inequities across the life course: Point-in-time measures, long-term exposures, and differential health returns. Soc Sci Med. 2016;170:63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jamal A, Agaku IT, O’Connor E, King BA, Kenemer JB, Neff L. Current cigarette smoking among adults--United States, 2005–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1108–1112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delker E, Brown Q, Hasin DS. Alcohol Consumption in Demographic Subpopulations: An Epidemiologic Overview. Alcohol Res. 2016;38:7–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zonderman AB, Mode NA, Ejiogu N, Evans MK. Race and Poverty Status as a Risk for Overall Mortality in Community-Dwelling Middle-Aged Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1394–1395. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lionello M, Staffieri A, Marioni G. Potential prognostic and therapeutic role for angiogenesis markers in laryngeal carcinoma. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012;132:574–582. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2011.652308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lara PC, Cuyas JM. The role of squamous cell carcinoma antigen in the management of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer. Cancer. 1995;76:758–764. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950901)76:5<758::aid-cncr2820760508>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harrell FE, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15:361. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harrell FE., Jr rms: Regression modeling strategies. 2016 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rms R package version 5.0–0.

- 48.Gray B. cmprsk: Subdistribution analysis of competing risks. 2014 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cmprsk R package version 2.2–7.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.