Abstract

Saponins are secondary metabolites that are widely distributed in plants. There are two major saponin precursors in soybean: soyasapogenol A, contributing to the undesirable taste, and soyasapogenol B, some of which have health benefits. It is important to control the ratio and content of the two major saponin groups to enhance the appeal of soybean as a health food. The structural diversity of saponin in the sugar chain composition makes it hard to quantify the saponin content. We measured the saponin content in soybean by removing the sugar chain from the saponin using acidic hydrolysis and detected novel quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for saponin content. Major QTLs in the hypocotyl were identified on chromosome 5 near the SSR marker, Satt 384, while those in the cotyledon were on chromosome 6 near Sat_312, which is linked to the T and E1 loci. Our results suggest that saponin contents in the hypocotyl and cotyledon are controlled by different genes and that it is difficult to increase the beneficial group B saponin and to decrease the undesirable group A saponin at the same time.

Keywords: Glycine max [L] Merr., saponin content, QTL, recombinant inbred line, hydrolysis

Introduction

Soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.) is an important commercial crop in many countries, and it is an excellent source of seed oil, protein, and functional substances such as isoflavone, saponin, and lecithin (Imai 2015). Worldwide soy consumption has continually increased because of soy’s nutritional properties and the functional characteristics of the compounds it contains.

Saponins are a secondary plant metabolite that includes triterpene glycosides, which are found in many plant species. The saponins have been shown to have several biological activities such as anticancer and anticholesterol activities (Güçlü-Üstündag and Mazza 2007). It was reported that saponins show inhibitory effects against HIV infectivity (Vlietinck et al. 1998) and the AIDS virus (Nakashima et al. 1989), and other effects such as possible cholesterol-binding, growth retarding, and anticarcinogenic activities (Gurfinkel and Rao 2003).

Sg-1, Sg-3, Sg-4, Sg-5, and Sg-6 have been identified as genes involved in saponin biosynthesis. Two co-dominant alleles, Sg-1a and Sg-1b for phenotypes of saponin Aa and Ab, respectively, control the sugar residue at the C-22 terminal position. Sg-1 is located on chromosome 7 (Sayama et al. 2012). Sg-3 and Sg-4, which control the sugar chain composition at C-3 sugar moieties in soyasapogenols A and B, are located on chromosomes 10 and 1, respectively (Takada et al. 2012). A mutant line, which lacked group A saponins, was caused by sg-5, which is located on chromosome 15 (Takada et al. 2013). Sg-6 controls monodesmosides with one sugar chain at the C-3 hydroxyl position of their respective soyasapogenols (Krishnamurthy et al. 2014).

Over 20 chemical structures of saponins have been determined from soybeans and soy products (Kim et al. 2012, Rupasinghe et al. 2003, Tantry and Khan 2013). There are two major saponin precursors: soyasapogenol A, contributing to the undesirable taste, and soyasapogenol B, some of which have health benefits (Rupasinghe et al. 2003). It is important to control the ratio and content of the two major saponin groups to enhance the appeal of soybean as a health food. Several saponin components make it difficult to quantify saponin contents. Some studies developed simplified methods in which all saponin contents were measured by converting into aglycones with acid hydrolysis (Hubert et al. 2005, Rupasinghe et al. 2003), but there are no reports about QTLs for amount of saponin contents. Moreover, effects of genotypes and environments on group B saponin concentration were reported (Seguin et al. 2014), using early maturing genotypes grown at high latitudes. Further knowledge regarding genetic control of saponin contents and environmental effects on saponin contents of various genotypes is required.

In this study, we cultivated a series of recombinant inbred lines (RILs) in the same year at three different locations and measured saponin as the contents of soyasapogenol A and B using acid hydrolysis. Chromosomal regions responsible for the saponin contents and the effects of growing conditions on the saponin content were also discussed. The results of this study will provide a basic understanding of genetic control for the group A and B saponin contents of soybean in multiple environments.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

Ninety-three RILs (F14) from the cross between ‘Peking’ and ‘Tamahomare’ soybean varieties (PT-RILs), which were developed using the single-seed descent method, were used in this study. Our preliminary study showed that the saponin contents from progeny of the cross between Peking and Tamahomare varied despite being almost the same levels in the parent plants. They were planted together with their parental varieties in fields in 2008 at three locations: Kyoto (Sowing date, 29 June; latitude, 35°01′N; elevation above sea level, 90 m), Nagano (Sowing date, 1 June; latitude, 36°06′N; elevation above sea level, 750 m), and Tsukuba (Sowing date, 15 June; latitude, 36°02′N; elevation above sea level, 25 m), in Japan. This field experiment was conducted using a randomized block design with two replications, and each plot contained 10 plants. N, P2O5, and K2O were applied as basal fertilizers in quantities of 20, 60, and 70 kg/ha, respectively. Plant spacing was 10 × 30 cm. The 100-seed weight of PT-RIL seeds (40 seeds per line) that were cultivated in Kyoto was measured. The flowering times were calculated as the number of days from sowing to flowering in Kyoto.

Saponin extraction

Ten seeds from each line and variety were separated into hypocotyl and cotyledon, powdered using a Multibead shocker (Yasui Kikai, Japan), and then dipped in a 10-fold volume (v/w) of aqueous 70% ethanol containing 0.1% acetic acid for 48 h at room temperature. The supernatant was mixed with hydrochloric acid at a final concentration of 0.1 N, followed by hydrolysis at 80°C for 6 h using a dry bath incubator (Nippon Genetics, Japan). The saponins in the extracts were transferred to aglycone soyasapogenol A and B.

Detection and quantification of saponin components by high-performance liquid chromatography

Hydrolysis extracts (10 μl), filtered with a 0.45-μm filter, were analyzed using a reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a YAM-Pack ODS-AM303 (YMC, Japan) and a thermostat up to 40°C. Saponins were separated under isocratic conditions of a 65% acetonitrile solution containing 0.1% acetic acid at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min, and the eluant was monitored at 210 nm. Soyasapogenol A (P2303) and B (P2304), as standards, were purchased from Tokiwa phytochemical (Japan).

Linkage map construction and quantitative trait locus analysis for saponin contents

In accordance with Sayama et al. (2009), we reconstructed the linkage map using F14 plants using 256 polymorphic SSR (simple sequence repeat) markers with MAPMAKER/EXE v. 3.0 software (Lander et al. 1987). QTL analysis was performed using the R/QTL package (Broman et al. 2003). The likelihood odds (LOD) thresholds were calculated using 1000 permutations.

Results

Saponin contents

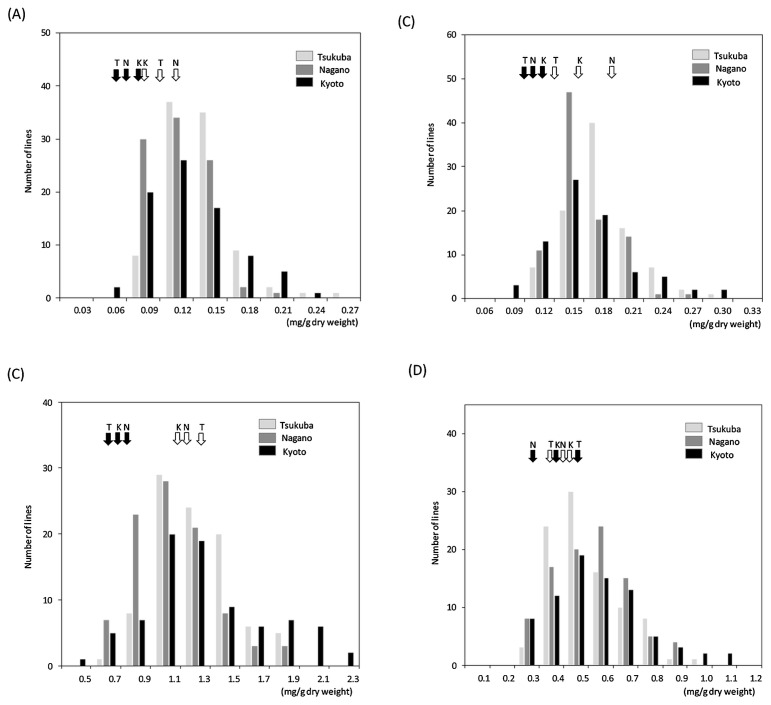

The hypocotyl and cotyledon saponin concentrations were measured in 93 PT-RILs harvested at the three locations. The saponin contents exhibited a wide variation both in the cotyledons and hypocotyls (Fig. 1). The saponin contents in Peking were greater than those in Tamahomare, except for group B saponins in the hypocotyl from Tsukuba (Table 1). Saponin content variation in PT-RILs was significantly greater than the difference between parental lines at all locations (Fig. 1). Transgressive segregation results indicate that both parental lines had alleles at different loci involved in saponin contents.

Fig. 1.

Frequency distribution of the saponin contents in PT-RILs. (A) Group A saponin contents in cotyledon, (B) Group A saponin contents in hypocotyl, (C) Group B saponin contents in cotyledon, (D) Group B saponin contents in hypocotyl. White and black arrows indicate the mean of saponin contents for ‘Peking’ and ‘Tamahomare’, respectively. ‘T’, ‘N’, and ‘K’ upside arrows indicate ‘Tsukuba’, ‘Nagano’, and ‘Kyoto’, respectively.

Table 1.

Distribution of saponin contents in the parental cultivars and the RIL population

| Parents | RILs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Peking (mg/g) | Tamahomare (mg/g) | Range (mg/g) | Mean(mg/g) | CV (%) | |

| Tsukuba | |||||

|

| |||||

| Group A saponin in cotyledon | 0.108 ± 0.018 | 0.065 ± 0.004 | 0.079–0.241 | 0.125 | 24.6 |

| Group A saponin in hypocotyl | 1.396 ± 0.179 | 0.750 ± 0.095 | 0.730–1.915 | 1.306 | 19.7 |

| Group B saponin in cotyledon | 0.140 ± 0.035 | 0.110 ± 0.018 | 0.095–0.282 | 0.166 | 20.7 |

| Group B saponin in hypocotyl | 0.420 ± 0.028 | 0.480 ± 0.104 | 0.204–0.920 | 0.493 | 29.0 |

|

| |||||

| Nagano | |||||

|

| |||||

| Group A saponin in cotyledon | 0.130 ± 0.001 | 0.070 ± 0.001 | 0.062–0.207 | 0.107 | 23.6 |

| Group A saponin in hypocotyl | 1.270 ± 0.039 | 0.890 ± 0.151 | 0.650–1.957 | 1.138 | 23.4 |

| Group B saponin in cotyledon | 0.199 ± 0.048 | 0.124 ± 0.023 | 0.097–0.265 | 0.157 | 56.6 |

| Group B saponin in hypocotyl | 0.460 ± 0.036 | 0.389 ± 0.030 | 0.230–0.854 | 0.505 | 28.8 |

|

| |||||

| Kyoto | |||||

|

| |||||

| Group A saponin in cotyledon | 0.099 ± 0.002 | 0.096 ± 0.005 | 0.047–0.307 | 0.125 | 45.8 |

| Group A saponin in hypocotyl | 1.259 ± 0.108 | 0.854 ± 0.024 | 0.576–2.394 | 1.372 | 30.1 |

| Group B saponin in cotyledon | 0.152 ± 0.022 | 0.132 ± 0.024 | 0.065–0.470 | 0.165 | 44.6 |

| Group B saponin in hypocotyl | 0.497 ± 0.013 | 0.432 ± 0.069 | 0.210–1.252 | 0.578 | 61.9 |

CV: coefficient of variation.

Values in parents are the means ± standard deviations.

QTL mapping

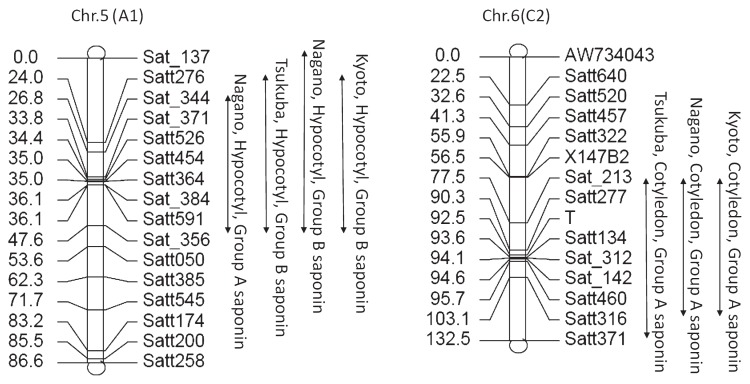

The simple interval mapping method and the composite interval method for R/QTL were used to calculate and analyze the QTL (Table 2, Fig. 2). The principal QTL for the hypocotyl saponin contents was detected on chromosome 5 and that for cotyledon saponin contents was detected on chromosome 6 using both methods. Alleles with increasing effect for QTLs on chromosomes 5 and 6 were the Peking type and the Tamahomare type, respectively. For the group A saponin of hypocotyls and the group B saponin of cotyledons in Tsukuba and Kyoto, no QTLs were detected using a simple interval mapping method. Similarly, no QTLs for the group A saponin of hypocotyl and cotyledon in Kyoto and for the group B saponin of cotyledons in Tsukuba and Kyoto were detected using the composite interval mapping method. Phenotypic variance explained by the QTL for the group B saponin of hypocotyls on chromosome 5 ranged from 18.8% in Kyoto to 44.2% in Nagano. Phenotypic variance explained by the QTL for the group A saponin of cotyledons on chromosome 6 ranged from 15.5% in Kyoto to 27.7% in Tsukuba.

Table 2.

Summary of the QTL for saponin contents detected in PT-RILs

| Simple Interval Mapping method | Marker Interval flanking QTL peak (marker position cM) | Chromosome (linkage group) | Highest LOD | Marker with highest LOD (marker position cM) | Alleles with increasing effect | Additive effect | Explained phenotypic variance (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypocotyl | Group A saponin | Tsukuba | Not detected | ||||||

| Nagano | Sat_344 ( 26.8)–Sat_356 (47.6) | 5 (A1) | 5.0 | Sat_384 (36.1) | Peking | 0.24 | 21.9 | ||

| Kyoto | Not detected | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Group B saponin | Tsukuba | Satt276 (24.0)– Sat_356 (47.6) | 5 (A1) | 4.9 | Sat_384 (36.1) | Peking | 0.14 | 22.0 | |

| Nagano | Sat_137 (0.0)– Sat_356 (47.6) | 5 (A1) | 11.8 | Satt364 (35.0) | Peking | 0.20 | 44.2 | ||

| Kyoto | Satt276 (24.0)– Sat_356 (47.6) | 5 (A1) | 4.2 | Satt526 (34.4) | Peking | 0.12 | 18.8 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Cotyledon | Group A saponin | Tsukuba | Sat_213 (77.5)– Satt371 (132.5) | 6 (C2) | 6.4 | T (92.5) | Tamahomare | 0.03 | 27.7 |

| Nagano | Sat_213 (77.5)– Satt316 (103.1) | 6 (C2) | 5.1 | Sat_312 (94.1) | Tamahomare | 0.02 | 22.3 | ||

| Kyoto | Satt302 (81.4)– Sat_218 (98.3) | 12 (H) | 3.0 | Sat_175 (91.8) | Peking | 0.05 | 13.8 | ||

| Kyoto | Sat_213 (77.5)– Satt316 (103.1) | 6 (C2) | 3.4 | Sat_312 (94.1) | Tamahomare | 0.05 | 15.5 | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| Group B saponin | Tsukuba | Not detected | |||||||

| Nagano | Satt590 (0.0)– Satt567 (20.9) | 7 (M) | 3.4 | Satt150 (3.7) | Peking | 0.02 | 15.5 | ||

| Kyoto | Not detected | ||||||||

| Composite Interval Mapping method | Marker Interval flanking QTL peak (marker position cM) | Chr. (linkage group) | Highest LOD | Marker with highest LOD (marker position cM) | Alleles with increasing effect | Additive effect | Explained phenotypic variance (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypocotyl | Group A saponin | Tsukuba | Sat_344 (26.8)–Sat_356 (47.6) | 5(A1) | 3.1 | Sat_384 (36.1) | Peking | 0.17 | 9.2 |

| Tsukuba | Sct_067 (15.6)–Satt424 (56.5) | 8 (A2) | 3.7 | I (49.2) | Peking | 0.07 | 17.0 | ||

| Nagano | Sat_344 (26.8)–Sat_356 (47.6) | 5 (A1) | 4.7 | Sat_384 (36.1) | Peking | 0.24 | 14.6 | ||

| Kyoto | Not detected | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Group B saponin | Tsukuba | Sat_344 (26.8)–Sat_356 (47.6) | 5 (A1) | 6.9 | Sat_384 (36.1) | Peking | 0.14 | 24.8 | |

| Tsukuba | Sat_092 (37.1)–Satt397 (52.9) | 17 (D2) | 4.2 | Satt669 (50.3) | Tamahomare | 0.07 | 11.2 | ||

| Nagano | Sat_344 (26.8)–Sat_356 (47.6) | 5 (A1) | 14.1 | Sat_371 (33.8) | Peking | 0.20 | 39.9 | ||

| Kyoto | Sat_344 (26.8)–Sat_356 (47.6) | 5 (A1) | 4.0 | Sat_371 (33.8) | Peking | 0.12 | 23.7 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Cotyledon | Group A saponin | Tsukuba | Satt277 (90.3)–Satt460 (95.7) | 6 (C2) | 5.7 | Satt134 (93.6) | Tamahomare | 0.03 | 22.0 |

| Nagano | Sat_213 (77.5)–Satt316 (103.1) | 6 (C2) | 7.4 | Sat_312 (94.1) | Tamahomare | 0.02 | 22.2 | ||

| Kyoto | Not detected | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Group B saponin | Tsukuba | Not detected | |||||||

| Nagano | Satt590 (0.0)–Satt567 (20.9) | 7 (M) | 4.3 | Satt150 (3.7) | Peking | 0.05 | 5.1 | ||

| Kyoto | Not detected | ||||||||

Fig. 2.

Genomic locations of QTL for saponin contents on chromosome 5 and chromosome 6 using simple interval mapping method.

Relationships with agronomic traits

We investigated seed weight and flowering time to reveal relationships between the saponin contents and other agronomic traits. QTLs for seed weight and flowering time were located near locus I on chromosome 8 and near Satt134 on chromosome 6, respectively (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Fig. 1). The QTL for flowering time was in the same chromosomal region as the QTL for the group A saponin of the cotyledon on chromosome 6.

Discussion

Beta-amyrin-derived oleanane-type triterpenoid saponins are synthesized in soybean seeds (Sawai and Saito 2011). Glycosylation of the terminal sugar results in generation of various kinds of saponin. Therefore, it was difficult to measure the total saponin contents in soybean. We simplified mea surement of the saponin contents using conversion to aglycone, such as soyasapogenol A and B, by acidic hydrolysis to remove sugar residues (Rupasinghe et al. 2003). The RIL population showed transgressive segregation and some QTLs for saponin contents, which have not been reported previously, were identified on the same regions among the three locations.

The major QTL for the group A saponin of cotyledon was located on chromosome 6 near Satt134. The T locus, which controls seed coat pigmentation, and the E1 locus, which controls flowering and maturation time (Xia et al. 2012), are located close to the region on chromosome 6. A gene located near E1 and T would affect accumulation of the group A saponin. A fine mapping study using a residual heterozygous line for this chromosomal region may resolve the relationships between saponin contents and the E1 or T loci.

Saponin contents in the hypocotyl was located on chromosome 5, in which no QTLs for seed weight and flowering time were detected. QTLs for group A saponin contents in hypocotyls from Nagano and Tsukuba overlapped with the QTLs for group B saponin contents in the hypocotyl. This indicates that group A and B saponin contents in the hypocotyl are controlled by the same gene or closely linked genes on chromosome 5 in the population crossed between Peking and Tamahomare, suggesting that it is difficult to increase the beneficial group B saponin and to decrease the undesirable group A saponin at the same time.

QTL analysis showed a tendency toward a greater phenotypic variance that is explained by the QTL in Tsukuba and Nagano compared with those in Kyoto. Temperature during plant growth in Kyoto was higher than in Nagano and Tsukuba in general. Seguin et al. (2014) reported that high temperatures reduced the group B saponin concentration, but our results did not show a significant reduction, suggesting that Peking and Tamahomare saponin contents were not sensitive to higher temperatures. Soybean genotypes evaluated by Seguin were only early maturing genotypes (maturity groups I to 00), while we used two genotypes adopted in more temperate regions, suggesting sensitivity to temperature is different among maturity groups. QTLs with higher LOD scores were detected in Tsukuba and Nagano but not in Kyoto, while we could not reveal the interaction between saponin contents and growing temperature.

Yoshikawa et al. (2010) evaluated the effects of temperature on isoflavone contents using PT-RILs. They found a weak negative correlation between isoflavone contents and temperature during the maturation period. Tsukamoto et al. (1993) also reported that isoflavone contents were decreased at higher temperatures. However, the saponin contents might be not influenced by environmental conditions.

In conclusion, we cultivated the same material at three different locations and compared the saponin contents. Transgressive segregation indicated that both parents harbor alleles at different loci involved in saponin contents. Two stable QTLs across multiple environments were detected for the saponin contents, QTLs on chromosome 6, linked with the T and E1 loci, are associated with saponin contents in the cotyledon and QTLs on chromosome 5 with saponin contents in the hypocotyl.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to NARO Institute of Crop Science (NICS) and to Nagano Vegetable and Ornamental Crops Experiment Station for cultivating the plant material. The authors are grateful to Dr. Sayama (NARO) for helpful discussions.

Literature Cited

- Broman, K.W., Wu, H., Sen, Ś. and Churchill, G.A. (2003) R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics 19: 889–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güçlü-Üstündag, Ö. and Mazza, G. (2007) Saponins: properties, applications and processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 47: 231–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurfinkel, D.M. and Rao, A.V. (2003) Soyasaponins: the relationship between chemical structure and colon anticarcinogenic activity. Nutr. Cancer 47: 24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert, J., Berger, M. and Dayde, J. (2005) Use of a simplified HPLC-UV analysis for soyasaponin B determination: study of saponin and isoflavone variability in soybean cultivars and soy-based health food products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53: 3923–3930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai, S. (2015) Soybean and processed soy foods ingredients, and their role in cardiometabolic risk prevention. Recent Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 7: 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.H., Ro, H.M., Kim, S.L., Kim, H.S. and Chung, I.M. (2012) Analysis of isoflavone, phenolic, soyasapogenol, and tocopherol compounds in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill] germplasms of different seed weights and origins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60: 6045–6055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy, P., Tsukamoto, C., Takahashi, Y., Hongo, Y., Singh, R.J., Lee, J.D. and Chung, G. (2014) Comparison of saponin composition and content in wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. and Zucc.) before and after germination. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 78: 1988–1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander, E.S., Green, P., Abrahamson, J., Barlow, A., Daly, M.J., Lincoln, S.E. and Newburg, L. (1987) MAPMAKER: an interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic linkage maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics 1: 174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima, H., Okubo, K., Honda, Y., Tamura, T., Matsuda, S. and Yamamoto, N. (1989) Inhibitory effect of glycosides like saponin from soybean on the infectivity of HIV in vitro. AIDS 3: 655–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupasinghe, H.P., Jackson, C.J., Poysa, V., Berardo, C.D., Bewley, J.D. and Jenkinson, J. (2003) Soyasapogenol A and B distribution in soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) in relation to seed physiology, genetic variability, and growing location. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51: 5888–5894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawai, S. and Saito, K. (2011) Triterpenoid biosynthesis and engineering in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayama, T., Nakazaki, T., Ishikawa, G., Yagasaki, K., Yamada, N., Hirota, N., Hirata, K., Yoshikawa, T., Saito, H., Teraishi, M.et al. (2009) QTL analysis of seed-flooding tolerance in soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.). Plant Sci. 176: 514–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayama, T., Ono, E., Takagi, K., Takada, Y., Horikawa, M., Nakamoto, Y., Hirose, A., Sasama, H., Ohashi, M., Hasegawa, H.et al. (2012) The Sg-1 glycosyltransferase locus regulates structural diversity of triterpenoid saponins of soybean. Plant Cell 24: 2123–2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguin, P., Chennupati, P., Tremblay, G. and Liu, W. (2014) Crop management, genotypes, and environmental factors affect soyasaponin B concentration in soybean. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62: 7160–7165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada, Y., Tayama, I., Sayama, T., Sasama, H., Saruta, M., Kikuchi, A., Ishimoto, M. and Tsukamoto, C. (2012) Genetic analysis of variations in the sugar chain composition at the C-3 position of soybean seed saponins. Breed. Sci. 61: 639–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada, Y., Sasama, H., Sayama, T., Kikuchi, A., Kato, S., Ishimoto, M. and Tsukamoto, C. (2013) Genetic and chemical analysis of a key biosynthetic step for soyasapogenol A, an aglycone of group A saponins that influence soymilk flavor. Theor. Appl. Genet. 126: 721–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tantry, M.A. and Khan, I.A. (2013) Saponins from Glycine max Merrill (soybean). Fitoterapia 87: 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, C., Kikuchi, A., Harada, K., Kitamura, K. and Okubo, K. (1993) Genetic and chemical polymorphisms of saponins in soybean seed. Phytochemistry 34: 1351–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlietinck, A.J., Bruyne, T.D., Apers, S. and Pieters, L.A. (1998) Plant-derived leading compounds for chemotherapy of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Planta Med. 64: 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Z., Watanabe, S., Yamada, T., Tsubokura, Y., Nakashima, H., Zhai, H., Anai, T., Sato, S., Yamazaki, T., Lü, S.et al. (2012) Positional cloning and characterization reveal the molecular basis for soybean maturity locus E1 that regulates photoperiodic flowering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: E2155–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, T., Okumoto, Y., Ogata, D., Sayama, T., Teraishi, M., Terai, M., Toda, T., Yamada, K., Yagasaki, K., Yamada, N.et al. (2010) Transgressive segregation of isoflavone contents under the control of four QTLs in a cross between distantly related soybean varieties. Breed. Sci. 60: 243–254. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.