We would like to admit that if we were purists, it would prove to be a difficult task to choose between the terms “epidemic” and “hyperendemic” to describe the current alarming situation of increased incidence as well as the prevalence of superficial dermatophytosis in India. For both terms, it would be essential to have comparative epidemiological data of the past and the present, and sadly, we are lacking in both. There is a dire need for well-designed studies as well as more solid evidence for various issues pertaining to the dermatophytosis scenario in India.[1]

It is an indisputable fact that there is an increase in the prevalence of dermatophytosis over the past 4–5 years across the country. Comparison of studies done on superficial fungal infections in cities such as Kolkata, Ahmedabad, and Chennai during different time frames have revealed an increasing trend of dermatophytosis.[2,3,4,5,6,7] We, however, need larger epidemiological studies to further bolster our nationwide observation of the alarming increase in its incidence as well as the prevalence.[1] Dermatophytosis has undergone a sea change in its clinical pattern in the past few years. The standard treatment recommendations which we have been following from the Western and Indian literature are no longer valid or even realistic[8,9,10] [Table 1]. In a country like India, where there is a paucity of original studies of dermatophytosis and its treatment, it is becoming amply clear that experience-based treatment of dermatophytosis is ruling the roost and is proving to be more effective than the standard guidelines provided in current literature that one often considers most valid and evidence based. While environmental factors, erratic use of topical and oral antifungal agents, increased prevalence of Trichophyton mentagrophytes infections causing inflammatory lesions and probably a growing resistance to antifungal agents may play an important role, one of the most formidable enemies that we have encountered in the recent times is the irrational fixed drug combination (FDC) creams containing a steroid, antifungal, and antibacterial with three to five molecules in the product.[1,11]

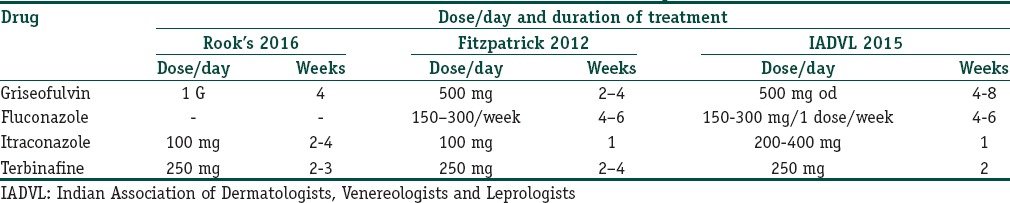

Table 1.

Treatment schedule of tinea corporis

There are many proponents of topical FDCs containing an antifungal and corticosteroid. An important article highlighting the conclusions of an expert panel meeting on topical treatment of superficial dermatophytoses written after reviewing numerous meta-analyses arrived at some conclusions supporting these combination creams. The authors of this seminal article concluded that adding topical corticosteroid to a topical antifungal agent in the beginning of the therapy can mitigate bothersome inflammation, reduce secondary colonisation with bacteria and enhance the efficacy of the antifungal drug. All the five authors practice in European countries where laws controlling the production and sales of drugs are stringent and are implemented. Therefore, this publication though comprehensive and erudite is not entirely relevant in the Indian context. The authors have specifically mentioned that the corticosteroid may be added in the initial part of the treatment and improper use of the combination creams may lead to both failure of treatment and adverse reactions.[12,13] Both points are very relevant for India. Topical corticosteroids used in combination with antifungal agents are very often potent molecules like clobetasol propionate, they are available over the counter and are grossly abused which includes buying over the counter and applying at will for weeks, months and sometimes years.[1,11,14,15,16,17,18,19] This leads to chronic, treatment resistant dermatophytosis which is causing a havoc in India.

This editorial is aimed at highlighting what seems a significant putative role of these FDCs in the dramatic increase in the number of chronic, recurrent, refractory cases of superficial dermatophytosis that we are encountering for the past 4–5 years. A significant temporal association has also been observed between the free availability of irrational FDCs and the epidemic proportion superficial dermatophytosis has assumed.

We have categorized this editorial into an elaboration on changing clinical patterns of tinea corporis and tinea cruris which are the most frequently encountered, the effect of freely available irrational FDC creams, the current drug control policies of the government, which the errant companies are taking advantage of and finally some recommendations based on our own experiences and those of several key opinion leaders from India.

Changing Clinical Patterns

There is a veritable epidemic of steroid modified tinea in India. Topical antifungals used for this condition are most often in combination with potent topical steroids and antibacterials.[1,11] Such formulations account for about 50% of the sales of all topical steroids. The most common combination in India at present is clobetasol propionate, ornidazole, ofloxacin, and terbinafine.[1,11] This speaks volumes about the inadequate understanding of the drug control authorities of India who grant permissions to companies manufacturing them. They cost a mere fraction of pure antifungal creams and hence are very popular. They are often bought over the counter, suggested and sold by the pharmacist or prescribed by the general practitioners. Moreover, they are used erratically, often only for symptom control and that too without any instructions or supervision. People often stop using them when the itching and redness are mitigated and begin to apply again when the symptoms reappear.

The cutaneous inflammatory response that the skin mounts to resist and limit the fungal infection is majorly suppressed by topical as well as systemic steroids. However, this effect of topical steroids is said to be more profound than with the other routes. Concomitantly, there is local suppression of T-cell mediated immune response to the dermatophyte. It is this “double trouble” that is most likely responsible for the altered patterns seen increasingly in the past few years. This temporary suppression of the host-induced inflammation leads to ineffective elimination of the dermatophyte, and the process becomes chronic and also widespread. At times, the borders of lesions become unclear resulting in ill-defined and bizarre-shaped lesions. The dermatophyte continues its centrifugal march albeit without adequate central clearing. This phenomenon leads to lesions that insidiously increase in size, adopt unusual shapes including tinea pseudoimbricata, eczematous lesions in the center, etc.

It is a common observation that severity of changes in the clinical pattern correlates with the duration of the abuse of topical steroids. The following are observations regarding the most common patterns occurring in India, namely, tinea cruris and tinea corporis: the classic description of lesion of tinea corporis or tinea cruris being circinate with an active erythematous well-defined border and central clearing is no longer valid [Figure 1]. We are seeing an increasing number of atypical presentations, cases that have been vitiated by topical steroids due to the adverse reactions over the treated and surrounding areas and many patients with chronic, recurrent, widespread lesions, many of whom do not respond to standard protocols of therapy. This trend is evident both in private practice as well as in large teaching hospitals. A tertiary care academic department in North India reported a prevalence of about 5%–10% of all new cases, many presenting with recurrent, chronic dermatophytosis with varied clinical presentations.[14]

Figure 1.

Scaly patch with an erythematous edge

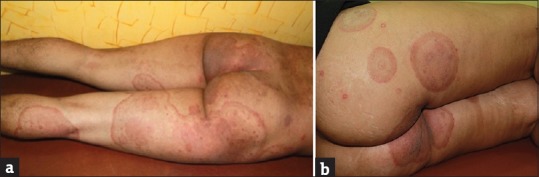

We are seeing larger sized and greater number of lesions in individual patients [Figure 2a and b]. It is now more common to see patients with more than one lesion of tinea in more than one anatomical location. Tinea cruris et corporis is getting more common.

Figure 2.

(a and b) Large sized, erythematous patches with active border over the gluteal regions and legs

We are seeing more women with active tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea corporis et tinea cruris. These women often present secondary to the index case that is most often a male. Fashion trends are changing, and tight fitting clothing such as figure hugging denims, leggings, and jeggings are increasingly preferred by youngsters who do not pay heed to practical aspects like their nonsuitability to our hot and humid climate. This could explain the increased prevalence of tinea cruris and tinea corporis not only in overweight but also in otherwise hygiene conscious, young, slim women with no other risk factors. A large number of women present with a submammary location of the infection that involves the inframammary fold more than the skin of the breasts. This underscores the role of friction and maceration resulting from moisture of perspiration. We are also seeing more children with dermatophytosis [Figure 3]. In the past, tinea capitis was considered to be the most common fungal infection occurring in children.[10] Tinea cruris and few small lesions of tinea corporis were uncommonly seen in infants and toddlers being handled by mothers and grandmothers suffering from tinea corporis with lesions on the trunk. In contrast, it is not uncommon now, to see children present with large-sized lesions and involvement of multiple sites. This can be explained by the increased spore load in the families by virtue of multiple family members being affected or perhaps an increased virulence and infectivity of the organism. It is also an indicator of the easy transmissibility of the dermatophyte. The role of fomites seems to be highlighted in the case of children because sharing of beds, linen, and clothing is all too common in them. In the author's experience, obese children are afflicted more. We are seeing a similarity between superficial dermatophytosis and scabies in that both show a distinct familial tendency. This underscores the importance of eliciting a careful family history during all visits. The importance of an untreated and undocumented affected family member being a constant source of reinfection that is often mistaken for treatment failure is being widely recognized in India. The practice of sharing the prescription of one family member with others for the purpose of symptom relief is common, which can also lead to clinical resistance.

Figure 3.

Tinea faciei in a child

We are seeing an increasing number of lesions with multiple concentric circles. It has also been described as “tinea pseudoimbricata” because it is reminiscent of tinea imbricata characterized by multiple concentric rings and has been explained to be occurring due to partial immune response. It has been seen in persons with immune suppression and those applying corticosteroids.[20] This has been described in India too, after associating its appearance with the use of topical corticosteroid combinations.[21] The authors have suggested that this is included as a manifestation of tinea incognito or rather steroid modified tinea induced by erratic use of antifungal and topical steroids combinations. The formation of concentric circles can be explained by the topical corticosteroid induced local immunosuppression and also its anti-inflammatory effect. The centrifugal spread of dermatophytosis is because of the cell-mediated immunity clearing the fungus in the center of the lesion and the dermatophyte moving radially further out at a rate that is faster than the rate of shedding of the outer corneocytes to survive.[22] It is felt that use of TCS, especially intermittently, would lead to suppression of inflammation and therefore promote survival of the dermatophyte which spreads centrifugally but also remains in the center due to inadequate clearance. If this happens repeatedly, it would lead to multiple active borders with intermittent clearing in areas where the organism has been cleared forming circles concentrically leading to “tinea pseudoimbricata.” Although one of us (Verma) has used the terms “tinea incognito” and “tinea pseudoimbricata” in previous publications, we find the following two terms easier and more accurate. Looking carefully at lesions of tinea pseudoimbricata, one observes that the lesions do not always have multiple concentric rings, but very commonly two rings and those too are not always complete. Perhaps the term “double-edged tinea” which is an important clinical pointer to the diagnosis of corticosteroid modified tinea is more appropriate and easier to comprehend for primary care physicians [Figure 4a and 4b]. There is also a difference between the terms “tinea incognito” and “steroid modified tinea.” We feel the term, “tinea incognito” should be used only in cases where the disease is rendered unrecognizable due to its altered appearance, most commonly due to topical corticosteroids.[23] However, in most cases of superficial dermatophytosis in which topical steroids and their irrational combinations have been used, it is possible to recognize the fungal infection. Therefore, “steroid modified tinea” is a more appropriate term.[23] And finally, it is pointed out that, grammatically the phrase “tinea incognito” is incorrect and should actually be “tinea incognita.”[23]

Figure 4.

(a and b) Classic “Double edged tinea” in the groins and lower abdomen

As mentioned earlier, a large number of lesions do not show central clearing. Instead, there are eczematized areas, within the lesions of tinea cruris and tinea corporis [Figure 5]. As explained in the pathogenesis of tinea pseudoimbricata, the central eczematization could possibly be due to inadequate clearing of the dermatophytes, owing to topical steroid application, and the inflammatory response that the viable dermatophytes would produce in those areas.

Figure 5.

Eczematous patch within a lesion of tinea corporis

We see arciform lesions, an increasing number of multiple annular lesions of various sizes showing confluence, the dumbbell-shaped tinea formed by the juxtaposition of two large annular lesions with eczematized centers and at times a curious clustering of multiple small annular lesions with active erythematous pustular borders [Figure 6a–c]. Some lesions show pustular borders [Figure 6d]. The latter has been attributed to a probable higher virulence of the organism promoting a stronger inflammatory response.

Figure 6.

(a) Multiple erythematous annular and arciform lesions with pustules in the periphery, adjacent to a large scaly patch. (b) Multiple annular lesions with erythematous borders showing confluence. (c) “Dumb-bell shaped tinea” formed by confluence of two large lesions. (d) Tinea genitalis lesion with pustular border

A distinct variant of dermatophytosis which seems to have been partially obscured and buried under the more visible rubble of tinea cruris is male genital tinea. There have been earlier reports of genital tinea written over two decades ago, in which Indian authors have observed it frequently whereas there have been scattered reports of the entity from West.[24,25,26,27,28] There has been a paucity of recent literature from India on genital dermatophytosis barring one written by the author and Vasani which describes the current increase in male genital tinea against the backdrop of steroid abuse.[15] Genital dermatophytosis is observed to be seen more commonly in males and occurs more commonly on the penis rather than the scrotum. It is almost always accompanied by tinea cruris or tinea cruris et corporis treated by irrational FDCs.[15] When it occurs in women, it usually affects the mons pubis and labia majora. While annular lesions with classic active borders may be seen on the penile shaft, some variants like areas of ill-defined scaly lesions and powdery scaling are also seen [Figure 7a and b]. Often, these patients have lesions on the base of the penis that are hidden by pubic hair as well as on the perineum and scrotum [Figure 7c]. The lateral aspects of the shaft too may be affected [Figure 7d]. This makes it essential to examine the penis by lifting it away from the scrotum which too may be affected uncommonly. The patient should be preferably in a reclining position so that the perineal lesions, often extensions of tinea cruris, do not get missed. Not explaining this to the patient often results in inadequate treatment because of the skipped areas. The untreated genitoperineal lesions become a nidus of a chronic infection unresponsive to conventional treatment.

Figure 7.

(a and b) Scaly patch over the shaft of penis. (c) The lateral aspects of the shaft too may be affected. (d) Ill-defined patch over the base of the penis

More number of tinea faciei are being seen. Most of these patients have an infection of other body areas such as tinea corporis or tinea cruris. Many of these cases of tinea faciei are probably true examples of tinea incognita because it is often difficult to appreciate the active borders of these lesions [Figure 8]. However, the pinna of the affected side is often involved as has been reported in tinea capitis in children as “ear sign.”[29]

Figure 8.

Tinea incognita – tinea faciei

There are said to be more number of cases of adult tinea capitis, and these have been found to be an extension from the face or the neck and is termed as “glabrous type of tinea capitis” which is the most common type of tinea capitis in adults [Figure 9].

Figure 9.

Glabrous type of tinea capitis in an adult

We are seeing more numbers of erythrodermic variants of tinea corporis, where there is widespread involvement of body surface with variable erythema with profuse scaling. Most of these patients are immunocompetent.

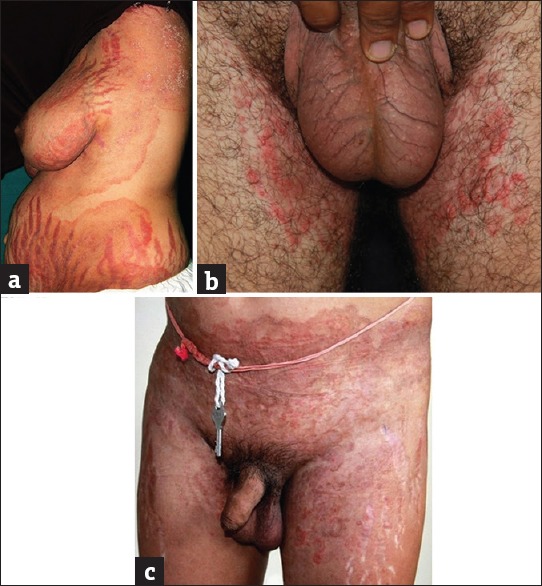

Many of the presentations enumerated above have accompanying stigmata of topical steroid abuse within the lesions of dermatophytosis as well as in their vicinity. The most frequently seen side effects in steroid modified tinea are striae, hypopigmentation, atrophy, and telangiectasias [Figure 10a–c]. Among these, it is the striae that show the starkest appearance. Never before have we seen so many dramatic presentations of striae induced by topical steroids. They sometimes appear as early as 3–4 weeks of application of FDCs containing antifungals, antibacterials, and potent steroid molecules such as clobetasol propionate. Once formed, a minority of them get inflamed, edematous, and even ulcerated with superadded bacterial infections. Moreover, it is frustrating to see patients continuing to apply the same preparations to the striae leading to a vicious cycle. Many patients are seen with superadded irritant contact dermatitis.

Figure 10.

(a) Extensive striae against a backdrop of active tinea. (b) Thinning of the scrotal skin with telangiectasia resulting from steroid application over the crural areas seen. Hypopigmentation over both the thighs also seen. (c) Skin atrophy and striae seen along with active, erythematous tinea corporis and tinea cruris due to the topical steroid abuse

An under-discussed fact is the financial burden that superficial dermatophytosis imposes on the patient and family. Often there are multiple family members affected, and for effective treatment, every member has to visit a dermatologist and buy drugs out of their own pocket. This is often a deterrent to many people for financial reasons who buy drugs only for one member and experiment with them for other members by taking self-treatment for short durations which further compounds the problem.

Changing Scenario of Dermatophytes

In the recent years, there seems to be an epidemiological transformation of dermatophytes in India. Although many studies done across India have found Trichophyton rubrum, to be the most common organism, the prevalence is much less compared to the past. In all these studies, Trichophyton mentagrophytes has emerged as the co-dominant pathogen with an increased prevalence in comparison to what was seen in the past.[2,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] A decline in the occurrence of the downy form of T rubrum has also been observed.[39] Recent mycological studies undertaken across the country have demonstrated Trichophyton mentagrophytes to be the predominant causative organism.[33,35,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] This organism has been found to exhibit a rapid growth in the primary culture within 5–7 days.[39] This change may be responsible for the widespread and inflammatory lesions that T. mentagrophytes is associated with. This change also affects the way we view the role of fomites in transmission of tinea. In an interesting study, T. rubrum survived for < 12 weeks on a towel while T. mentagrophytes survived for >25 weeks on towels.[47] This fact highlights the importance of disinfection of clothes which could be best done by washing in hot water at 60°C and drying in sunlight, as sunlight is considered to be the most effective disinfectant for dermatophytes.[48]

Many consider antifungal resistance to be the most important cause for the treatment failure of dermatophytosis. To understand the reality, it is essential for us to consider few facts about antifungal resistance, the occurrence of which has to be considered independently for each antifungal class and for each fungal genus. Antifungal resistance is broadly classified into microbiological resistance and clinical resistance. Microbiological resistance refers to nonsusceptibility of a fungus to an antifungal agent as determined by in vitro susceptibility testing, in which the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) exceeds the susceptibility breakpoint for that organism. Microbiological resistance can be primary or secondary resistance. Primary or the intrinsic resistance occurs naturally among certain fungi without prior exposure to the drug as is the resistance of Candida krusei to fluconazole and Cryptococcus neoformans to echinocandins. Secondary or the acquired resistance which develops among previously susceptible strains after exposure to the antifungal agent is usually dependent on altered gene expression. This is illustrated by fluconazole resistance among Candida albicans and C. neoformans species. Clinical resistance is the failure to eliminate a fungal infection despite the administration of an antifungal agent which may or may not demonstrate MIC's in the resistance range for that organism. Clinical resistance may be due to a combination of factors related to the host, the pathogen or the antifungal agent. There have been few isolated reports of resistance of dermatophytes to griseofulvin and terbinafine.[49]

Standard antifungal susceptibility tests (AST) for the molds are generally cumbersome to perform than the antibacterial susceptibility tests. Hence, they are best performed by reference laboratories. At present, standard guidelines have been proposed by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), United States and European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) for in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing of dermatophytes. Broth microdilution method of AST recommended by CLSI and EUCAST is presently accepted as the standard method of testing. MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of an antifungal agent that will inhibit the visible growth of microorganism. Although antifungal resistance is usually correlated with increased MIC, MIC values do not always correlate with clinical response to antifungal drugs. The discordance between the in vivo and in vitro resistance in candidiasis has been illustrated by the “90–60 rule,” which states that that infections due to susceptible strains respond to appropriate therapy in 90% of cases, whereas infections due to resistant strains respond in approximately 60% of patients. Breakpoints also termed as interpretive criteria are used to denote susceptibility and resistance to antifungal agents, as the outcome of AST. They are categorized as susceptible, intermediate, and resistant. However, till now, the breakpoints have not been defined for the dermatophytes due to lack of data on the clinical correlation, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies, or epidemiological cutoff MIC values.[49,50] Hence, experts opine that it is logical to not to use the term, “resistant” in the absence of these definitive criteria for dermatophytes.[39] With this background, increase in the MIC values of isolates to terbinafine, fluconazole, and griseofulvin observed in various studies does not imply that there is an absolute resistance, instead this only warrants the use of adequate or higher dosage of these drugs or a longer duration of treatment to get the clinical response. Current scenario calls for standardized antifungal susceptibility studies across the country to know the pattern and any increase in MIC of the antidermatophyte drugs, pending recognition of definitive interpretive breakpoints for dermatophytes by the CLSI. The above reiterates the observations and exhortations made in the recent editorial in the IJDVL regarding the dire need for more studies and a stronger evidence base’ for the epidemiology, mycology and treatment recommendations of the current epidemic of superficial dermatophytosis in India.[51]

The Indiscriminate Use of Topical Corticosteroid Combinations and Lax Government Policies

Topical steroids of all strengths, alone or in combination with other molecules, have always, for all practical purposes, been sold over the counter because of nebulous laws open to different interpretations.[1] The Drug Controller General of India (DCGI) finally paid heed to the constant exhortations and recommendations of Indian Association of Dermatologists, Venereologists and Leprologists (IADVL) in August 2016 and included most major topical steroid molecules as Schedule H drugs meaning they legally cannot be sold over the counter and without a valid prescription of a medical practitioner. However, the Gazette notification to this effect issued in the third quarter of 2016 has still not been implemented and all topical steroids continue to be sold freely in the market. The DCGI, in another welcoming step also banned many major irrational and easily available topical FDCs containing an antifungal, steroid, and antibacterial molecule.[52,53] Unfortunately, the pharmaceutical industries have succeeded in bringing a stay order in a high court of India and they continue to be manufactured and sold with impunity. It is worth noting that no major developing nation, let alone developed nations, has been able to obtain licenses to manufacture so many irrational FDCs. A fine example of this category of topical drugs is the highest selling FDC containing clobetasol, ofloxacin, ornidazole and terbinafine.[11] Numerous other combinations which are essentially permutations and combinations of a topical antifungal, an antibacterial, and a steroid molecule, are freely available in the market and have become the bane of Indian dermatologists. The DCGI and state licensing authorities have also issued permissions to manufacture scientifically irrational products with a high potential to induce antifungal resistance such as itraconazole powder, itraconazole cream, topical amphotericin B, and oral FDCs containing terbinafine and itraconazole. These permissions stand out as especially irrational and potentially a public health threat considering the fact that the World Health Organization (WHO) is making concerted efforts to combat antimicrobial resistance (AMR). We would like to quote two relevant key facts from the fact sheet updated by WHO as recently as September 2016. (1) “AMR is an increasingly serious threat to global public health that requires action across all government sectors and society.” (2) “The cost of health care for patients with resistant infections is higher than care for patients with nonresistant infections due to longer duration of illness, additional tests, and use of more expensive drugs.“[54] All new drugs and their combinations are required by law to furnish their safety and efficacy data to the DCGI. One wonders if data pertaining to such dubious FDCs have been presented at all and if so, on what grounds and with what understanding of dermatology has the Central Drug Standards Control Organization (CDSCO) approved them. It is common knowledge that quite often state licensing authorities issue permissions without the knowledge or consent of the DCGI, a reflection of pervasive bad governance and corruption in a system that deals directly with the health of the people.

Commonly Employed Treatment Measures

We are seeing a sea change in the prescription patterns of dermatologists in private practice as well as in academic departments. The accepted guidelines of western books do not hold true anymore. We are using higher doses of oral antifungals for a longer time and these tend to benefit the patients more. Similarly, we have observed that even topical antifungal creams need to be applied for a longer duration. Stopping the oral or topical therapy before 3 weeks is often associated with a reappearance of preexisting lesions or even new lesions in other areas. Hundreds of brands of oral as well as topical antifungal drugs are available in India. We have observed that many cheaper brands made by relatively obscure companies often do not have satisfactory efficacy when compared to well-known brands of reputed companies. It would be worthwhile doing a study of bioavailability of various brands. It is also frightening to see how drug companies manage to obtain permission to introduce newer antifungal formulations such as fluconazole powder, itraconazole powder as well as cream and amphotericin B gel. Weight-based dosing of terbinafine and occasionally of itraconazole instead of a blanket recommendation of terbinafine 250 mg for 15 days and itraconazole 100 mg for 15 days or 200 mg for 7 days is found to be more beneficial[8,9,10] [Table 1]. Even the older antifungal agents such as Griseofulvin given in a dosage of 500 mg twice a day for 6 weeks or fluconazole in a dose of 150 mg thrice weekly for 8 weeks seem to lead to a good clinical outcome in patients with recalcitrant dermatophytosis. However, it is important to perform baseline liver and renal function tests and a periodic monitoring whenever one contemplates the use of systemic antifungals in a higher dosage, always remembering the drug-drug interactions, especially in patients who are on multiple drugs. The recommendations given by three of the most popularly read textbooks of dermatology in India given in Table 1 do not seem relevant in today's scenario. We need treatment guidelines based on Indian experiences that are backed up by our own studies. A large number of dermatologists vouch for the inadequacy of 100 mg of itraconazole for 2-4 weeks and are administering 200 mg of the drug for 3-4 weeks or more and have observed good clinical response.

Newer topical antifungals such as eberconazole and sertaconazole are found to be more efficacious compared to the older azoles like clotrimazole probably because they exert better anti-inflammatory effect.[55,56] The uncomfortable truth is that all these changes in pattern of prescriptions are happening, even if to the benefit of the patient, without a simple potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination in most patients especially in the case of private practitioners who form the majority of caregivers. Although it is thought to be essential in many countries, it is not practical because it is time consuming and most often the doctors do not have trained assistants to do this. While the initial diagnosis of dermatophytosis does not warrant KOH examination unless in doubt, there is a need for performing the test before extending the treatment with the newer oral antifungals beyond 1 month, in case of partial resolution.

The following are measures found to be beneficial by most:

Strict avoidance of any antifungal preparation, wherein a steroid is added. Strong counseling highlighting the obvious perils of these FDCs is mandatory

Stressing on the importance of regularity of medication and adherence to the advice of the physician. The topical antifungals should be applied 2 cm beyond the margin of the lesion for at least 2 weeks beyond clinical resolution. We call this recommendation of applying topical antifungals 2 cm beyond the margin, twice a day for 2 weeks beyond clinical resolution “The rule of Two”

Advice against wearing tight garments such as jeans, leggings, and jeggings

Wearing loose, cotton garments

Discouraging sharing of bed linen if feasible, towels and clothes. Regular washing of towels and bed linen

Taking regular showers. Wearing clothes only after thoroughly drying the body

Washing clothes and bed linen in hot water and then sunning them. Sunlight is known to destroy dermatophytes. In the absence of sunlight, ironing the clothes would be beneficial too

Drying of clothes inside out. Wearing well dried inner garments after about 3–4 days of washing if ironing is not possible

Washing infected clothes separately

Instructing patients with tinea cruris to wear “boxer shorts” instead of the tight fitting ones that hug the groin and cut into it

Removing waistband, wristband, etc.

Preferring nonocclusive footwear

Dusting, wet mopping or vacuuming the house followed by cleaning with detergent so as to reduce the spore load in the immediate environment

Explaining all this is time-consuming, however, it is vital to ensure the compliance and to enhance the awareness levels of the patient. We could issue pamphlets or use posters to ensure the strict adherence to all these measures.

The Future and the Challenges

We need to recognize and appreciate the fact that there is a lack of documentation and evidence in almost every problematic aspect that we have witnessed regarding this frightening epidemic of superficial dermatophytosis in India. The way forward are large-scale systematic studies proving the association of topical steroids, especially the combinations and chronic widespread dermatophytosis, which is indeed a daunting task for operational reasons. We are just beginning to explore the resistance patterns, if any, by antifungal susceptibility testing. We need to delve into more genetic aspects and immunological aspects that are known to lead to chronic widespread dermatophytosis (CWD). However, while doing so, it is abundantly clear that the menace of topical steroids has to be minimized. The easy availability of TCS and combinations containing TCS and antifungals has to be controlled stringently. Topical steroids and their combinations need to be sold as “prescription only” aka “Schedule H” drugs. The government will most likely face resistance from pharmaceutical companies, but the rule has to be strictly implemented with punitive measures for defaulters. Only then, shall we see a decline in steroid modified tinea and many cases of chronic widespread dermatophytosis. The CDSCO in New Delhi and all state licensing authorities need to actively take the wise counsel of an expert panel of dermatologists before issuing licenses to new FDCs. They need to summarily revoke the licenses given so far. IADVL has initiated concerted efforts to educate public, chemists and medical practitioners about this issue. The association has also made several representations to the DCGI and other senior bureaucrats in the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Irrational FDCs and formulations are also exported to many developing countries. It is highly unfortunate that the pharmaceutical industry, one of the major players globally in manufacturing as well as exports is responsible for this chaotic situation which could have been easily avoided.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

References

- 1.Verma SB. Sales, status, prescriptions and regulatory problems with topical steroids in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:201–3. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.132246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grover WC, Roy CP. Clinico-mycological profile of superficial mycosis in a hospital in North-East India. Med J Armed Forces India. 2003;59:114–6. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(03)80053-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das K, Basak S, Ray S. A study on superficial fungal infection from West Bengal: A brief report. J Life Sci. 2009;1:51–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nawal P, Patel S, Patel M, Soni S, Khandelwal N. A study of superficial mycosis in tertiary care hospital. Natl J Integr Res Med. 2012;3:95–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chudasama V, Solanki H, Vadasmiya M, Javadekar T. A study of superficial mycosis in tertiary care hospital. Int J Sci Res. 2014;3:222–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannan P, Janaki C, Selvi GS. Prevalence of dermatophytes and other fungal agents isolated from clinical samples. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2006;24:212–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narasimhalu CR, Kalyani M, Somendar S. A cross-sectional, clinico-mycological research study of prevalence, aetiology, speciation and sensitivity of superficial fungal infection in Indian patients. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 2016;7:324. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hay RJ, Ashbee HR. Fungal infections. In: Griffiths CE, Barker J, Bleiker T, Chalmers R, Creamer D, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 9th ed. II. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell; 2016. p. 945. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schieke SM, Garg A. Superficial fungal infection. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffel DJ, Wolff K, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. II. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012. p. 2294. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manjunath Shenoy M, Suchitra Shenoy M. Superficial fungal infections. In: Sacchidanand S, Oberoi C, Inamdar AC, editors. IADVL Textbook of Dermatology. 4th ed. I. Mumbai: Bhalani Publishing House; 2015. pp. 459–516. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verma SB. Topical steroid misuse in India is harmful and out of control. BMJ. 2015;351:h6079. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaller M, Friedrich M, Papini M, Pujol RM, Veraldi S. Topical antifungal-corticosteroid combination therapy for the treatment of superficial mycoses: Conclusions of an expert panel meeting. Mycoses. 2016;59:365–73. doi: 10.1111/myc.12481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaller M. Dermatomycoses and inflammation: The adaptive balance between growth, damage, and survival. J Mycol Med. 2015;25:e44–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dogra S, Uprety S. The menace of chronic and recurrent dermatophytosis in India: Is the problem deeper than we perceive? Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:73–6. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.178100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verma SB, Vasani R. Male genital dermatophytosis – Clinical features and the effects of the misuse of topical steroids and steroid combinations – An alarming problem in India. Mycoses. 2016;59:606–14. doi: 10.1111/myc.12503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lahiri K, Coondoo A. Topical and steroid damaged/dependent face(TSDF): An entity of cutaneous pharmacodependence. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:265–72. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.182417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rathi SK, D’Souza P. Rational and ethical use of topical corticosteroids based on safety and efficacy. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:251–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.97655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saraswat A. Ethical use of topical corticosteroids. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:469–72. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.139877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar S, Goyal A, Gupta YK. Abuse of topical corticosteroids in India: Concerns and the way forward. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2016;7:7–15. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.179364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim SP, Smith AG. “Tinea pseudoimbricata”: Tinea corporis in a renal transplant recipient mimicking the concentric rings of tinea imbricata. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:332–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verma S, Hay RJ. Topical steroid-induced tinea pseudoimbricata: A striking form of tinea incognito. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:e192–3. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hay RJ, Ashbee HR. Mycology. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. II. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 1657–749. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verma SB. A closer look at the term ‘tinea incognito’ – A factual as well as grammatical inaccuracy. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:219–20. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_84_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szepietowski JC. Tinea of the penis: A rare location of the dermatophyte infection. Nouv Dermatol. 1998;17:571–3. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romano C, Ghilardi A, Papini M. Nine male cases of tinea genitalis. Mycoses. 2005;48:202–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2005.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prohic A, Krupalija-Fazlic M, Sadikovic TJ. Incidence and etiological agents of genital dermatophytosis in males. Med Glas (Zenica) 2015;12:52–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vora NS, Mukhopadhyay AK. Incidence of dermatophytosis of penis and scrotum. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 1994;60:89–91. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta R, Banerjee U. Tinea of the penis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1992;58:99–101. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agarwal US, Mathur D, Mathur D, Besarwal RK, Agarwal P. Ear sign. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:105–6. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.126064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rani U, Saigal RK, Kanta S, Krishnan R. Study of dermatophytosis in Punjabi population. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1983;26:243–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singla B, Malhotra R, Walia G. Mycological study of dermatophytosis in 100 clinical samples of skin hair and nail. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;5:763–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aggarwal A, Arora U, Khanna S. Clinical and mycological study of superficial mycoses in Amritsar. Indian J Dermatol. 2002;47:218–20. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kansra S. Prevalence of dermatophytoses and their antifungal susceptibility in a tertiary care hospital of North India. Int J Sci Res. 2016;5:450–3. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh UK, Nath P. Fungal flora in the superficial infections of the skin and nails at Lucknow. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1981;24:189–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan MS, Khan N. A study of fungal isolates from superficial mycoses cases attending IIMS & R, Lucknow. Int J Life Sci Sci Res. 2016;2:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghosh RR, Ray R, Ghosh TK, Ghosh AP. Clinico-mycological profile of dermatophytosis in a tertiary care hospital in West Bengal, an Indian scenario. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2014;3:655–66. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar K, Kindo AJ, Kalyani J, Anandan S. Clinico-mycological profile of dermatophytic skin infections in a tertiary care center – A cross sectional study. Sri Ramachandra J Med. 2007;1:12–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramaraj V, Vijayaraman RS, Rangarajan S, Kindo AJ. Incidence and prevalence of dermatophytosis in and around Chennai, Tamilnadu, India. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016;4:695–700. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miskeen AK, Uppulri P. Dermatophytosis. In: Tahiliani S, editor. Mycoscope. New Delhi: IJCP Publications Ltd; 2016. pp. 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaur I, Thakur K, Sood A, Mahajan VK, Gupta PK, Chauhan S, et al. Clinico-mycological profile of clinically diagnosed cases of dermatophytosis in North India: A prospective cross-sectional study. Int J Health Sci Res. 2016;6:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kainthola A, Gaur P, Dobhal A, Sundriyal S. Prevalence of dermatophytoses in rural population of Garhwal Himalayan Region, Uttarakhand, India. Int Res J Med Sci. 2014;2:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agarwal US, Saran J, Agarwal P. Clinico-mycological study of dermatophytes in a tertiary care centre in Northwest India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:194. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.129434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noronha TM, Tophakhane RS, Nadiger S. Clinico-microbiological study of dermatophytosis in a tertiary-care hospital in North Karnataka. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:264–7. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.185488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumaran G, Jeya M. Clinico-mycological profile of dermatophytic infections. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2014;5:(B)1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhatia VK, Sharma PC. Epidemiological studies on dermatophytosis in human patients in Himachal Pradesh, India. Springerplus. 2014;3:134. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jain S, Sharma V. Clinicomycological study of dermatophytes in Solan. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2015;4:190–3. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khanjanasthiti P, Srisawat P. Germination and survival of dermatophyte spores in various environmental conditions. Chiang Mai Med. 1984;23:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amichai B, Grunwald MH, Davidovici B, Shemer A. Sunlight is saidc to be the best of disinfectants: The efficacy of sun exposure for reducing fungal contamination in used clothes. Isr Med Assoc J. 2014;16:431–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kanafani ZA, Perfect JR. Resistance to antifungal agents: Mechanisms and clinical impact. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:120–8. doi: 10.1086/524071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Melhem MS, Bonfietti LX, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. Susceptibility test for fungi: Clinical and laboratorial correlations in medical mycology. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2015;57(Suppl 19):57–64. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652015000700011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Panda S, Verma S. The menace of dermatophytosis in India: The evidence that we need. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:281–4. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_224_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. [Last accessed on 2017 Apr 09]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs194/en/

- 53.Pande S. Steroid containing fixed drug combinations banned by government of India: A big step towards dermatologic drug safety. Indian J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;2:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Report of Expert Committee on Evaluation of Cases of Fixed Dose Combinations(FDCs) Except Vitamins and Mineral Preparations Categorized Under Category ‘b’ i.e. FDC's Requiring Further Deliberation with Subject Experts. Section 16. [Last accessed on 2016 May 27]. Available from: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/writereaddata/1fdc27-5-2016.pdf .

- 55.Jerajani HR, Janaki C, Kumar S, Phiske M. Comparative assessment of the efficacy and safety of sertaconazole (2%) cream versus terbinafine cream (1%) versus luliconazole (1%) cream in patients with dermatophytoses: A pilot study. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:34–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.105284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moodahadu-Bangera LS, Martis J, Mittal R, Krishnankutty B, Kumar N, Bellary S, et al. Eberconazole – Pharmacological and clinical review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:217–22. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.93651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]