Abstract

The orexin-A/hypocretin-1 and orexin-B/hypocretin-2 are neuropeptides synthesized by a cluster of neurons in the lateral hypothalamus and perifornical area. Orexin neurons receive a variety of signals related to environmental, physiological and emotional stimuli, and project broadly to the entire CNS. Orexin neurons are “multi-tasking” neurons regulating a set of vital body functions, including sleep/wake states, feeding behavior, energy homeostasis, reward systems, cognition and mood. Furthermore, a dysfunction of orexinergic system may underlie different pathological conditions. A selective loss orexin neurons was found in narcolepsia, supporting the crucial role of orexins in maintaining wakefulness. In animal models, orexin deficiency lead to obesity even if the consume of calories is lower than wildtype counterpart. Reduced physical activity appears the main cause of weight gain in these models resulting in energy imbalance. Orexin signaling promotes obesity resistance via enhanced spontaneous physical activity and energy expenditure regulation and the deficiency/dysfunction in orexins system lead to obesity in animal models despite of lower calories intake than wildtype associated with reduced physical activity. Interestingly, orexinergic neurons show connections to regions involved in cognition and mood regulation, including hippocampus. Orexins enhance hippocampal neurogenesis and improve spatial learning and memory abilities, and mood. Conversely, orexin deficiency results in learning and memory deficits, and depression.

Keywords: orexin, obesity, emotional stress, narcolepsy

Introduction

Orexin A and B are excitatory hypothalamic neuropeptides playing a relevant role in different physiologic functions such as sleep/wake rhythms and thermoregulation, control of energy metabolism, cardiovascular responses, feeding behavior, and spontaneous physical activity (SPA).

At the end of the last century, Sakurai et al. (1998) firstly described Hypocretins 1 and 2 as regulators of feeding and appetite behavior, produced in a specific hypothalamic region (Edwards et al., 1999; Haynes et al., 2000, 2002).

More recent studies focused the attention on the role of the orexins in mood and emotional regulation, energetic homeostasis, reward mechanisms, drug addiction, arousal system, and sleep and wakefulness (Peyron et al., 2000; Thannickal et al., 2000; Hara et al., 2001; Yamanaka et al., 2003a; Harris et al., 2005; Narita et al., 2006). However, the function of orexins in metabolism pathways are far to be completely understood.

The orexin/hypocretin system

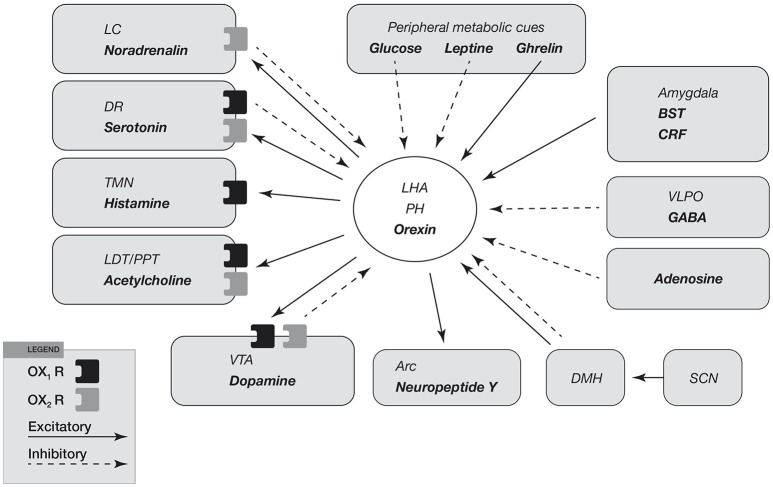

In Mammals, orexin A and orexin B are synthesized in the lateral hypothalamic and perifornical areas (Peyron et al., 1998; Nambu et al., 1999), starting from a common polypeptide precursor (prepro-orexin) through proteolytic processing (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of orexin system. Orexin A and orexin B are derived from a common precursor peptide, prepro-orexin. The actions of orexins are mediated via two G protein-coupled receptors named orexin-1 (OX1R) and orexin-2 (OX2R) receptors. OX1R is selective for orexin A, whereas OX2R is a non-selective receptor for both orexin A and orexin B. OX1R is coupled exclusively to the Gqsubclass of heterotrimeric G proteins, whereas OX2R couples to Gi/oand/or Gq.

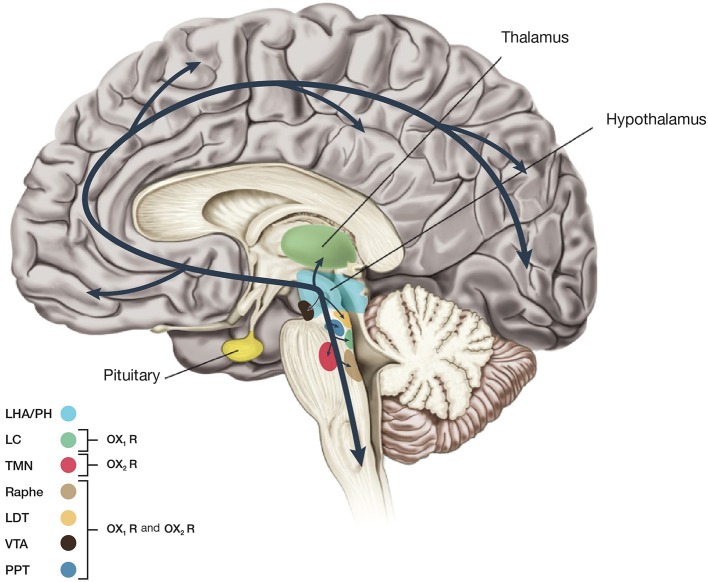

Orexin A is a neuropeptide composed of 33 amino acids with an amino(N)-terminal pyroglutamyl residue, two intra-chain disulphide bonds and carboxy (C)-terminal amidation, while Orexin B is a linear neuropeptide sized 28 amino acids, C-terminally amidated. The N-terminal portion presents more variability, whilst the C-terminal portion is similar between the two subtypes. The orexins activity is modulated by their specific receptors (OX1R, OX2R). OX1R presents higher affinity for orexin A than B and transmits signals throughout the G-protein class activating a cascade that leads to an increase in intracellular calcium concentration. By contrast, OX2R binds the two subtypes of orexin with similar affinities, probably associated to a G inhibitory protein class (Xu et al., 2013). These differences seem to suggest different physiological roles for OX1R and OX2R (Trivedi et al., 1998). Different physiological roles of OX1R and OX2R seem to be supported by the observation that mRNAs receptors show complementary distribution patterns (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Schematic drawing showing main projections of orexin neurons. This figure summarizes predicted orexinergic projections in the human brain. Please note that distributions of orexin fibers and receptors (OX1R, OX2R) are predicted from the results of studies on rodent brains since most histological studies on the orexin system have been carried out in mice and rats. Circles show regions with strong receptor expression and dense orexinergic projections. Orexin neurons originating in the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) and posterior hypothalamus (PH) regulate sleep and wakefulness and the maintenance of arousal by sending excitatory projections to the entire CNS, excluding the cerebellum, with particularly dense projections to monoaminergic, and cholinergic nuclei in the brain stem and hypothalamic regions including the locus coeruleus (LC, containing noradrenaline), tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN, containing histamine), raphe nuclei (Raphe, containing serotonin), and laterodorsal/pedunclopontine tegmental nuclei (LDT/PPT), containing acetylcholine). Orexin neurons also have links with the reward system through the ventral tegmental area (VTA, containing dopamine) and with the hypothalamic nuclei that stimulate feeding behavior.

- OX1R is distributed in prefrontal and infralimbic cortex (IL), hippocampus (CA2), amygdala, stria terminalis bed nucleus (BST), PVT, anterior hypothalamus, dorsal raphe (DR), ventral tegmental area (VTA), locus coeruleus (LC), and laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (LDT)/pedunculopontine nucleus (PPT) (Trivedi et al., 1998; Lu et al., 2000);

- OX2R is distributed in amygdala, TMN, Arc, dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (DMH), paraventricular nucleus (PVN), LHA, BST, PVT, DR, VTA, LDT/PPT, CA3 in the hippocampus, and medial septal nucleus (Lu et al., 2000).

Modulation of orexin neurons

Electrophysiological studies on transgenic mice have identified several neurotransmitters and neuromodulators influencing the activation or inhibition in orexin neurons activity. Specifically, GABA (Xie et al., 2006), noradrenaline and serotonin seem to inhibit the activity of orexin neurons (Yamanaka et al., 2003b), as dopamine acts through activation of α2-adrenoceptors (Yamanaka et al., 2006). Moreover, agonists of ionotropic glutamate receptors tend to excite orexin neurons, while glutamate antagonists inhibit their activity (Li et al., 2002) indicating that glutamatergic neurons can tonically activate orexin neurons. Cholecystokinin, neurotensin, oxytocin, and vasopressin enhance orexin neurons activity (Tsujino et al., 2005; Tsunematsu et al., 2008) by modulation of adenosine and CO2 concentrations (Liu and Gao, 2007; Williams et al., 2007).

Sleep/wake regulation

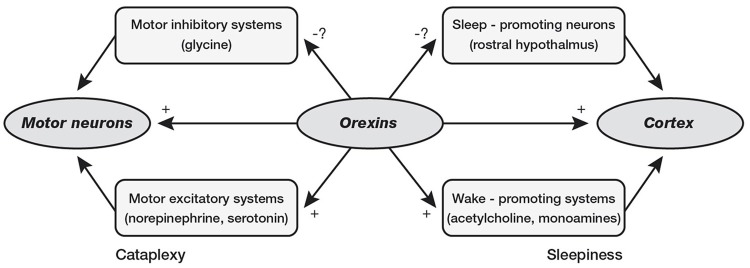

Interestingly, orexin system seems to be crucial for maintenance of wakefulness state, as demonstrated by narcolepsy caused by orexin deficiency in Human and Animals (Chemelli et al., 1999; Lin et al., 1999). Narcolepsy is a neurological disease affecting ~1 in 2,000 individuals in the United States (Mignot, 1998), characterized by chronic daytime sleepiness, sleep attacks, and possibility of cataplexy, hypnagogic hallucinations and sleep paralysis. These symptoms are not necessary to be present all together and narcolepsy may be identified and diagnosed by standard polysomnography (PSG) at all ages, including childhood. Narcolepsy is the results of orexin-containing neurons loss, which tend to increase their activity during wakefulness activating aminergic nuclei such as locus coeruleus, raphe nuclei, and tuberomamillary nucleus with maintaining wake state and preventing of inappropriate transitions into sleep, particularly REM sleep phases (Saper et al., 2001; España and Scammell, 2011). Narcolepsy is usually classified into two subtypes: (a) Narcolepsy with cataplexy (type 1); and (b) Narcolepsy without cataplexy (type 2). On the other hand, the orexin in sleep/wake regulation and pathophysiology of narcolepsy may be not limited to the activation/deactivation of cataplexic phenomena and/or sleep attacks. In fact, affected children and adolescents present specific cognitive impairments (Posar et al., 2014), which pinpoint the close relationship between sleep and cognition (Esposito and Carotenuto, 2014). Moreover, probably due to the same role in sleep modulation, orexin seems to be also involved in the pathogenesis of migraine (Rainero et al., 2008) as suggested by the link between NREM sleep instability and risk of cognitive impairments and behavioral problems (McCoy and Strecker, 2011; Bruni et al., 2012; Colonna et al., 2015; Carotenuto et al., 2016, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Loss of orexin signaling could cause cataplexy by reducing activity in motor excitatory systems of brainstem or by providing less suppression of the motor inhibitory systems. Loss of orexin could cause sleepiness by reducing activity in the cholinergic and monoaminergic arousal systems or by reducing inhibition of sleep-promoting neurons in the rostral hypothalamus (preoptic area).

Feeding behaviors and energy homeostasis

Orexin A seems to regulate feeding behaviors and energy expenditure as evidenced by the intracerebroventricular (icv) injection of orexins effects during the light period, which induces feeding behavior in rodents and zebrafishes, probably for a direct action on lateral hypothalamic area containing neurons modulated by glucose concentration. In fact, the high concentrations of glucose and leptin tend to hyperpolarize orexinergic neurons, while low concentrations of glucose and ghrelin depolarize them. Therefore, the orexinergic system discriminate physiological variation in glucose levels due to meals modulating in this way energy balance according to food intake (Monda et al., 2008; Messina et al., 2014). Moreover, transgenic mice with gradual and then loss of hypothalamic orexin-containing neurons show feeding abnormalities and dysregulation in energy homeostasis determining obesity despite the reduction of food intake/calories. Interestingly, it has been reported an increased prevalence of obesity in narcoleptic subjects in all ages (Yokobori et al., 2011).

Shiuchi et al. (2009) observed that the regulation mediated by orexinergic system on muscle glucose metabolism is due to activation of β2-adrenergic signaling and consequently peripheral energy expenditure. A persistent wake-state mediated by orexins could also be important for food intake motivation. When facing reduced food availability, animals adapt with a longer awake period, revolutionizing their normal pattern of activity (Viggiano et al., 2009). During starvation the activation of orexin neurons mediated by low leptin and glucose levels, might modulate their activity according to energy expenditure and stores to maintain wakefulness, whilst orexin neuron-ablated mice fail to respond to fasting with increased wakefulness and activity (Viggiano et al., 2010; Messina et al., 2013; Chieffi et al., 2017; Villano et al., 2017). These data confirm that orexin neurons mediate energy balance and arousal, maintaining a consolidated state of wakefulness in hungry animals in order to promote alertness.

The role of orexin system in obesity

Obesity is a complex multifactorial condition lowering health quality and many effects such as metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, sleep apnea syndrome, and reduced in life expectancy (Must et al., 1999). In the last decades, the incidence of obesity has increased both in children and adults worldwide (Flegal et al., 2010). Environmental and genetic factors cause large variations among human susceptibility to obesity. Physical activity and the so called “non-exercise induced thermogenesis” (NEAT) are factors determining this variability and susceptibility. The term NEAT includes all types of energy expenditure not associated with formal exercise, such as standing and fidgeting (Levine, 2002). A complementary concept to that of NEAT is the spontaneous physical activity (SPA) describing any type of physical activity not qualified as voluntary exercise. Together NEAT and SPA are hereditable but not interchangeable, because NEAT refers to energy expenditure while SPA describes the types of physical activity resulting in NEAT. Therefore, SPA induces an important variability in sensitivity to obese subject that spend less time standing than leans (Levine et al., 2005). Orexin signaling would promote obesity resistance via enhanced SPA and energy expenditure regulation and the deficiency/dysfunction in orexins system lead to obesity in animal models despite of lower calories intake than wildtype associated with reduced physical activity. On the other hand, the body weight regulation seems to be complex according to the lack of orexin neurons. In 2012, Perez-Leighton et al. (2012) highlighted the protective role of intratecal administration orexin A against obesity in mice models.

Orexin A has also been discovered to promote SPA and NEAT as effect of administration into specific cerebral areas (i.e., rostral LH, hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, nucleus accumbens, locus coeruleus, dorsal raphe nucleus, tuberomamillary nucleus, substantia nigra, Hara et al., 2005). In this light, orexinergic neurotransmission may be an interesting and new pharmacologic target for obesity therapy (Zink et al., 2014). Low levels of orexin in CNS and peripheral tissues were found in animal models of obesity diet-induced (Hara et al., 2005), and adipose tissue in obese humans subjects showed lower concentrations of orexin and reduced in its receptors activity (Hara et al., 2005). A study conducted by Levin et al. (1997) on Sprague Dawley rats showed that models fed with a high-fat diet gained no more weight than chow-fed controls. Obesity prone (OP) and obesity resistant (OR) models present different profiles in weight gaining despite of no differences in energy intake (Levin et al., 1997; Messina et al., 2015; Messina A. et al., 2016). The OR group showed lower body weight and fat mass on a low-fat diet and gain less weight when fed with high-fat diet than OP group. Furthermore, OR rats lean group suggest that the negative caloric benefit of OXA-induced SPA appears to outweigh the positive calories due to OXA-induced hyperphagia (Levin et al., 1997; Carotenuto et al., 2010; Esposito et al., 2013). OXA action on SPA had a longer duration when compared with that above food intake (Carotenuto et al., 2011; Bellini et al., 2013); OR rats have higher endogenous SPA thus reflecting their higher sensitivity to SPA- promoting stimuli such as lower caloric intake. By contrast OP rats displayed lower SPA endogenous levels after a high-fat diet administration if compared to their OR group counterpart (Levin et al., 1997; Esposito et al., 2012a). Conversely, obesity tends to increase also the prevalence of migraine in all ages of life (Esposito et al., 2012b; Verrotti et al., 2012, 2015).

Reward system

Orexin system seems to play a unified role in coordinating motivational activation under numerous behavioral conditions (James et al., 2016) as showed, for example, by its involving in alcohol use and drug-addiction (Martin-Fardon et al., 2016; Walker and Lawrence, 2016). Recent studies focused their attention on reward system modulation by orexin system. Treating narcoleptic patients with amphetamine-like drugs (Di Bernardo et al., 2014) did not lead to addiction to these drugs (Monda et al., 2014). Wild-type mice are more susceptible to developing morphine dependence in comparison with orexin knockout mice (Chieffi et al., 2014b). Furthermore, reward brain circuits in humans affected by narcolepsy were identified as abnormal (Viggiano et al., 2014) However, the mismatch between predicted reward and reward subsequently received was significantly higher in Parkinson's disease (PD) compared to narcoleptic, independent of reward magnitude and valence as showed by cataplexy that may be triggered by both positive and negative emotions (Mensen et al., 2015).

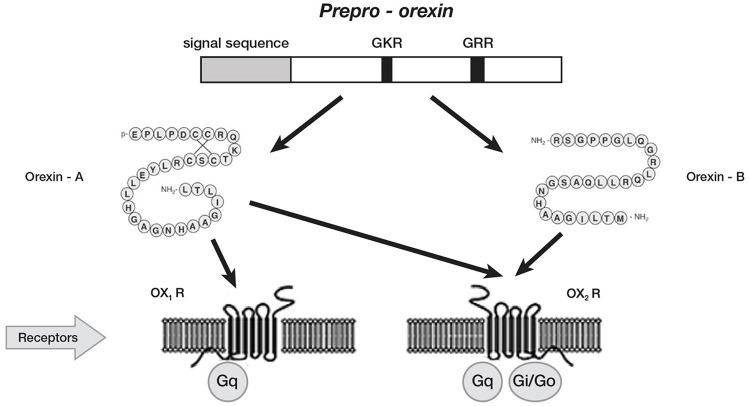

Regulatory mechanisms at the base of reward system are shown in Figure 4. It seems to be clear that orexin neurons modulate reward system and play a predominant role in mechanisms of drug addiction. Many reports suggest a critical role of orexin signaling in neural plastic effects at glutamatergic synapses in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Input and output of orexin neurons at interface of sleep, stress, reward, and energy homeostasis. Orexin neurons in the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) and posterior hypothalamus (PH) are placed to provide a link among limbic system, energy homeostasis, brainstem and other systems. Arrows show excitatory projections and broken arrows inhibitory projections. Gray semicircles indicate OX1R and black semicircles indicate OX2R. Neurotransmitters/modulators are underlined. LC, DR, and TMN are wake-active regions, VLPO is sleep-active region, and LDT/PPT is REM-active region. Orexin neurons promote wakefulness through monoaminergic nuclei that are wake-active. Stimulation of dopaminergic centers by orexins modulates reward systems (VTA). Peripheral metabolic signals influence orexin neuronal activity to coordinate arousal and energy homeostasis. Stimulation of neuropeptide Y neurons by orexin increases food intake. The SCN, the central body clock, sends input to orexin neurons via the DMH. Input from the limbic system (amygdala and BST) might be important to regulate the activity of orexin neurons upon emotional stimuli to evoke emotional arousal or fear-related responses. Abbreviations: BST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; VLPO, ventrolateral preoptic area; LC, locus ceruleus; DR, dorsal raphe; TMN, tuberomammillary nucleus; LDT, laterodorsal tegmental nucleus; PPT, pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus; VTA, ventral tegmental area; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus; DMH, dorsomedial hypothalamus; Arc, arcuate nucleus.

Links with brain

Animal studies suggest that orexinergic system may enhance hippocampal neurogenesis influencing learning and memory processes. In 2004, Wayner et al. (2004) reported that local dentate gyrus perfusion with orexin-A in anesthetized rats enhanced long-term potentiation (LTP) strengthen the link between structural and functional hippocampal plasticity. Moreover, Wayner et al. (2004) showed that LTP enhancement may be blocked in SB-334867 pre-treated rats SB-334867, a specific Ox1R antagonist (Wayner et al., 2004). The effects of dentate gyrus-OX1Rs antagonization on LTP occurred also in freely moving rats impairing spatial memory in Morris water maze (Wayner et al., 2004). Some studies examined the effects of the administration of orexin-A in rats treated with Pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) (Zhao et al., 2014). PTZ induces seizures resulting in the hippocampal atrophy, learning and memory deficits and decrease of cerebrospinal fluid-level of orexin-A (Coppola et al., 2010), while the intracerebroventricular injection of orexin-A in PTZ-kindled rats tend to attenuate these impairments, enhancing neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus (Zhao et al., 2014). Interestingly, in rats treated with orexin-A more than 50% of newborn cells differentiated into neurons, whereas only approximately 30% of the newborn cells differentiated into neurons in the control group (Zhao et al., 2014).

Moreover, Orexin-A seems to be implicated in social memory, the ability to distinguish and remember familiar from novel conspecifics (Yang et al., 2013). Yang et al. (2013) reported that orexin/ataxin-3-transgenic (AT) mice, in which orexin neurons degenerate by 3 months of age, displayed deficits in long-term social memory. Nasal administration of exogenous orexin-A restored social memory and enhanced synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus (Yang et al., 2013). A decrease of Orexin-A was found in animal models of depression and its intracerebroventricular administration reduced depression symptoms and increases the number of cells in the dentate gyrus (Arendt et al., 2013). Then, it is possible that the enhancement of cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus by orexin-A might have an antidepressive-like effect.

Interestingly, physical exercise produces an increase of orexin-A level in cerebrospinal fluid of rats, dogs and cats, and in plasma of humans (Messina G. et al., 2016). Note that the orexin-A rapidly cross the blood-brain barrier, probably by simple diffusion, having a high degree of lipophilicity. Furthermore, physical exercise is (a) an effective tool for enhancing cognitive performance and regulating mood and (b) produced morphological and functional changes of brain regions that play central roles in successful everyday functioning, such as frontal and temporal cortices, and the hippocampus located in the inner (medial) region of the temporal lobe. The frontal lobe is important for cognitive function (Iavarone et al., 2007; Chieffi et al., 2009, 2012; Boscia et al., 2015), the temporal lobe for memory function (Chieffi et al., 2004, 2014a, 2015; Marra et al., 2013; Franco et al., 2014). The factors most likely involved in exercise-induced hippocampal neurogenesis are the microcirculation and the production of neurotrophic factors such as the BDNF, VEGF, and IGF-1 (Cotman et al., 2007). Another putative factor that might contribute to the beneficial effects of exercise is the orexin-A.

Concluding remarks

Orexin is necessary for healthy life because of the important and relevant homeostatic functions controlled and organized directly or not. Orexin role is not only limited to the brain areas, because it involved also in metabolic regulation.

Author contributions

AM, VM, AV, IV, MR: conceived the study, participated in its design, and wrote the manuscript. FP, DT, MS, NF, FN, LC, EN: contributed to the conception and design. SC, MC, VD, GC, MPM, DI, MM, GM: drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content. DI revised grammar and English form; GM: final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer IS declared a shared affiliation, though no other collaboration, with several of the authors MC, FP, MR to the handling Editor, who ensured that the process nevertheless met the standards of a fair and objective review.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- SPA

spontaneous physical activity

- OX1R

orexin receptor 1

- OX2R

orexin receptor 2

- IL

infralimbic cortex

- CA2

hippocampus CA2 area

- BST

stria terminalis bed nucleus

- PVT

paraventricular thalamus

- DR

dorsal raphe

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

- LC

locus coeruleus

- LDT

laterodorsal tegmental nucleus

- PPT

pedunculopontine nucleus

- TMN

tuberomammillary nucleus

- Arc

arcuate nucleus

- DMH

dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus

- LHA

Lateral hypothalamic area

- BST

bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

- PVT

paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus

- GABA

gamma-aminobutyric acid

- CO2

carbon dioxide

- PSG

standard polysomnography

- NREM

Non-Rapid eyes movement

- ICV

intracerebroventricular

- NEAT

non-exercise induced thermogenesis

- SPA

spontaneous physical activity

- LH

lateral hypothalamus

- CNS

central nervous system

- OP

obesity prone

- OR

obesity resistant

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- PTZ

Pentylenetetrazol

- AT

orexin/ataxin-3-transgenic

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- IGF-1

insuline-like growth factor.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by grants of “Section of Human Physiology and Unit of Dietetic and Sport Medicine and Department of Experimental Medicine,” Università degli Studi della Campania “L. Vanvitelli”.

References

- Arendt D. H., Ronan P. J., Oliver K. D., Callahan L. B., Summers T. R., Summers C. H. (2013). Depressive behavior and activation of the orexin/hypocretin system. Behav. Neurosci. 127, 86–94. 10.1037/a0031442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini B., Arruda M., Cescut A., Saulle C., Persico A., Carotenuto M. (2013). Headache and comorbidity in children and adolescents. J. Headache Pain. 14:79. 10.1186/1129-2377-14-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscia F., Passaro C., Gigantino V., Perdonà S., Franco R., Portella G. (2015). High levels of GPR30 protein in human testicular carcinoma in situ and seminomas correlate with low levels of estrogen receptor-beta and indicate a switch in estrogen responsiveness. J. Cell. Physiol. 230, 1290–1297. 10.1002/jcp.24864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni O., Kohler M., Novelli L., Kennedy D., Lushington K., Martin J., et al. (2012). The role of NREM sleep instability in child cognitive performance. Sleep 35, 649–656. 10.5665/sleep.1824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carotenuto M., Esposito M., Cortese S., Laino D., Verrotti A. (2016). Children with developmental dyslexia showed greater sleep disturbances than controls including problems initiating and maintaining sleep. Acta Paediatr. 105, 1079–1082. 10.1111/apa.13472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carotenuto M., Esposito M., Pascotto A. (2010). Migraine and enuresis in children: an unusual correlation? Med. Hypotheses 75, 120–122. 10.1016/j.mehy.2010.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carotenuto M., Esposito M., Precenzano F., Castaldo L., Roccella M. (2011). Cosleeping in childhood migraine. Minerva Pediatr. 63, 105–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemelli R. M., Willie J. T., Sinton C. M., Elmquist J. K., Scammell T., Lee C., et al. (1999). Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell 98, 437–451. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81973-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieffi S., Conson M., Carlomagno S. (2004). Movement velocity effects on kinaesthetic localization of spatial positions. Exp. Brain Res. 158, 421–426. 10.1007/s00221-004-1916-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieffi S., Iachini T., Iavarone A., Messina G., Viggiano A., Monda M. (2014a). Flanker interference effects in a line bisection task. Exp. Brain Res. 232, 1327–1334. 10.1007/s00221-014-3851-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieffi S., Iavarone A., Iaccarino L., La Marra M., Messina G., De Luca V., et al. (2014b). Age-related differences in distractor interference on line bisection. Exp. Brain Res. 232, 3659–3664. 10.1007/s00221-014-4056-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieffi S., Iavarone A., La Marra M., Messina G., Dalia C., Viggiano A., et al. (2015). Vulnerability to distraction in schizophrenia. J Psychiatry 18, 228 10.4172/Psychiatry.1000228 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chieffi S., Iavarone A., Viggiano A., Monda M., Carlomagno S. (2012). Effect of a visual distractor on line bisection. Exp. Brain Res. 219, 489–498. 10.1007/s00221-012-3106-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieffi S., Messina G., Villano I., Messina A., Esposito M., Monda V., et al. (2017). Exercise influence on hippocampal function: possible involvement of orexin-A. Front. Physiol. 8:85. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieffi S., Secchi C., Gentilucci M. (2009). Deictic word and gesture production: their interaction. Behav. Brain Res. 203, 200–206. 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna A., Smith A. B., Pal D. K., Gringras P. (2015). Novel mechanisms, treatments, and outcome measures in childhood sleep. Front. Psychol. 6:602. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola G., Arcieri S., D'Aniello A., Messana T., Verrotti A., Signoriello G., et al. (2010). Levetiracetam in submaximal subcutaneous pentylentetrazol-induced seizures in rats. Seizure 19, 296–299. 10.1016/j.seizure.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman C. W., Berchtold N. C., Christie L. A. (2007). Exercise builds brain health: key roles of growth factor cascades and inflammation. Trends Neurosci. 30, 464–472. 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bernardo G., Messina G., Capasso S., Del Gaudio S., Cipollaro M., Peluso G., et al. (2014). Sera of overweight people promote in vitro adipocyte differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 5:4. 10.1186/scrt393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C. M. B., Abusnana S., Sunter D., Murphy K. G., Ghatei M. A., Bloom S. R. (1999). The effect of the orexins on food intake: comparison with neuropeptide Y, melanin-concentrating hormone and galanin. J. Endocrinol. 160, R7–R12. 10.1677/joe.0.160R007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- España R. A., Scammell T. E. (2011). Sleep neurobiology from a clinical perspective. Sleep 34, 845–858. 10.5665/SLEEP.1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito M., Carotenuto M. (2014). Intellectual disabilities and power spectra analysis during sleep: a new perspective on borderline intellectual functioning. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 58, 421–429. 10.1111/jir.12036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito M., Pascotto A., Gallai B., Parisi L., Roccella M., Marotta R., et al. (2012a). Can headache impair intellectual abilities in children? an observational study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 8, 509–513. 10.2147/NDT.S36863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito M., Roccella M., Parisi L., Gallai B., Carotenuto M. (2013). Hypersomnia in children affected by migraine without aura: A questionnaire-based case-control study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 9, 289–294. 10.2147/NDT.S42182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito M., Verrotti A., Gimigliano F., Ruberto M., Agostinelli S., Scuccimarra G., et al. (2012b). Motor coordination impairment and migraine in children: a new comorbidity? Eur. J. Pediatr. 171, 1599–1604. 10.1007/s00431-012-1759-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal K. M., Carroll M. D., Ogden C. L., Curtin L. R. (2010). Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA 303, 235–241. 10.1001/jama.2009.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco R., Zappavigna S., Gigantino V., Luce A., Cantile M., Cerrone M., et al. (2014). Urotensin II receptor determines prognosis of bladder cancer regulating cell motility/invasion. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 33:48. 10.1186/1756-9966-33-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara J., Beuckmann C. T., Nambu T., Willie J. T., Chemelli R. M., Sinton C. M., et al. (2001). Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity. Neuron 30, 345–354. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00293-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara J., Yanagisawa M., Sakurai T. (2005). Difference in obesity phenotype between orexin-knockout mice and orexin neuron-deficient mice with same genetic background and environmental conditions. Neurosci. Lett. 380, 239–242. 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.01.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris G. C., Wimmer M., Aston-Jones G. (2005). A role for lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward seeking. Nature 437, 556–559. 10.1038/nature04071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes A. C., Chapman H., Taylor C., Moore G. B., Cawthorne M. A., Tadayyon M., et al. (2002). Anorectic, thermogenic and anti-obesity activity of a selective orexin-1 receptor antagonist in ob/ob mice. Regul. Pept. 104, 153–159. 10.1016/S0167-0115(01)00358-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes A. C., Jackson B., Chapman H., Tadayyon M., Johns A., Porter R. A., et al. (2000). A selective orexin-1 receptor antagonist reduces food consumption in male and female rats. Regul. Pept. 96, 45–51. 10.1016/S0167-0115(00)00199-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iavarone A., Patruno M., Galeone F., Chieffi S., Carlomagno S. (2007). Brief report: error pattern in an autistic savant calendar calculator. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 37, 775–779. 10.1007/s10803-006-0190-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James M. H., Mahler S. V., Moorman D. E., Aston-Jones G. (2016). Decade of orexin/hypocretin and addiction: where are we now? Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1007/7854_2016_57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin B. E., Dunn-Meynell A. A., Balkan B., Keesey R. E. (1997). Selective breeding for diet-induced obesity and resistance in Sprague-Dawley rats. Am. J. Physiol. 273, R725–R730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine J. A. (2002). Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT). Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 16, 679–702. 10.1053/beem.2002.0227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine J. A., Lanningham-Foster L. M., McCrady S. K., Krizan A. C., Olson L. R., Kane P. H., et al. (2005). Interindividual variation in posture allocation: possible role in human obesity. Science 307, 584–586. 10.1126/science.1106561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Gao X. B., Sakurai T., van den Pol A. N. (2002). Hypocretin/Orexin excites hypocretin neurons via a local glutamate neuron-A potential mechanism for orchestrating the hypothalamic arousal system. Neuron 36, 1169–1181. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01132-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., Faraco J., Li R., Kadotani H., Rogers W., Lin X., et al. (1999). The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell 98, 365–376. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81965-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. W., Gao X. B. (2007). Adenosine inhibits activity of hypocretin/orexin neurons by the A1 receptor in the lateral hypothalamus: a possible sleep-promoting effect. J. Neurophysiol. 97, 837–848. 10.1152/jn.00873.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X. Y., Bagnol D., Burke S., Akil H., Watson S. J. (2000). Differential distribution and regulation of OX1 and OX2 orexin/hypocretin receptor messenger RNA in the brain upon fasting. Horm. Behav. 37, 335–344. 10.1006/hbeh.2000.1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra L., Cantile M., Scognamiglio G., Perdonà S., La Mantia E., Cerrone M. (2013). Deregulation of HOX B13 expression in urinary bladder cancer progression. Curr. Med. Chem. 20, 833–839. 10.2174/0929867311320060008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fardon R., Cauvi G., Kerr T. M., Weiss F. (2016). Differential role of hypothalamic orexin/hypocretin neurons in reward seeking motivated by cocaine versus palatable food. Addict. Biol. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/adb.12441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy J. G., Strecker R. E. (2011). The cognitive cost of sleep lost. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 96, 564–582. 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensen A., Poryazova R., Huegli G., Baumann C. R., Schwartz S., Khatami R. (2015). The roles of dopamine and hypocretin in reward: a electroencephalographic study. PLoS ONE 10:e0142432. 10.1371/journal.pone.0142432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina A., De Fusco C., Monda V., Esposito M., Moscatelli F., Valenzano A., et al. (2016). Role of the orexin system on the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis. Front. Neural Circuits 10:66. 10.3389/fncir.2016.00066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina G., Dalia C., Tafuri D., Monda V., Palmieri F., Dato A., et al. (2014). Orexin-A controls sympathetic activity and eating behavior. Front. Psychol. 5:997. 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina G., De Luca V., Viggiano A., Ascione A., Iannaccone T., Chieffi S., et al. (2013). Autonomic nervous system in the control of energy balance and body weight: personal contributions. Neurol. Res. Int. 2013:639280. 10.1155/2013/639280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina G., Di Bernardo G., Viggiano A., De Luca V., Monda V., Messina A., et al. (2016). Exercise increases the level of plasma orexin A in humans. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 27, 611–616. 10.1515/jbcpp-2015-0133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina G., Monda V., Moscatelli F., Valenzano A. A., Monda G., Esposito T., et al. (2015). Role of Orexin system in obesity. Biol. Med. 7:248 10.4172/0974-8369.1000248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mignot E. (1998). Genetic and familial aspects of narcolepsy. Neurology 50, S16–S22. 10.1212/WNL.50.2_Suppl_1.S16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monda M., Messina G., Scognamiglio I., Lombardi A., Martin G. A., Sperlongano P., et al. (2014). Short-term diet and moderate exercise in young overweight men modulate cardiocyte and hepatocarcinoma survival by oxidative stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014:131024. 10.1155/2014/131024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monda M., Viggiano A., Viggiano A., Mondola R., Viggiano E., Messina G., et al. (2008). Olanzapine blocks the sympathetic and hyperthermic reactions due to cerebral injection of orexin A. Peptides 29, 120–126. 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Must A., Spadano J., Coakley E. H., Field A. E., Colditz G., Dietz W. H. (1999). The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity aviva. JAMA 282, 1523–1529. 10.1001/jama.282.16.1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambu T., Sakurai T., Mizukami K., Hosoya Y., Yanagisawa M., Goto K. (1999). Distribution of orexin neurons in the adult rat brain. Brain Res. 827, 243–260. 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01336-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M., Nagumo Y., Hashimoto S., Narita M., Khotib J., Miyatake M., et al. (2006). Direct involvement of orexinergic systems in the activation of the mesolimbic dopamine pathway and related behaviors induced by morphine. J. Neurosci. 26, 398–405. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2761-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Leighton C. E., Boland K., Teske J. A., Billington C., Kotz C. M. (2012). Behavioral responses to orexin, orexin receptor gene expression, and spontaneous physical activity contribute to individual sensitivity to obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 303, E865–E874. 10.1152/ajpendo.00119.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C., Faraco J., Rogers W., Ripley B., Overeem S., Charnay Y., et al. (2000). A mutation in a case of early onset narcolepsy and a generalized absence of hypocretin peptides in human narcoleptic brains. Nat. Med. 6, 991–997. 10.1038/79690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C., Tighe D. K., van den Pol A. N., de Lecea L., Heller H. C., Sutcliffe J. G., et al. (1998). Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J. Neurosci. 18, 9996–10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posar A., Pizza F., Parmeggiani A., Plazzi G. (2014). Neuropsychological findings in childhood narcolepsy. J. Child Neurol. 29, 1370–1376. 10.1177/0883073813508315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainero I., De Martino P., Pinessi L. (2008). Hypocretins and primary headaches: neurobiology and clinical implications. Expert Rev. Neurother. 8, 409–416. 10.1586/14737175.8.3.409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T., Amemiya A., Ishii M., Matsuzaki I., Chemelli R. M., Tanaka H., et al. (1998). Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell 92, 573–585. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80949-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper C. B., Chou T. C., Scammell T. E. (2001). The sleep switch: hypothalamic control of sleep and wakefulness. Trends Neurosci. 24, 726–731. 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)02002-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiuchi T., Haque M. S., Okamoto S., Inoue T., Kageyama H., Lee S., et al. (2009). Hypothalamic orexin stimulates feeding-associated glucose utilization in skeletal muscle via sympathetic nervous system. Cell Metab. 10, 466–480. 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannickal T. C., Moore R. Y., Nienhuis R., Ramanathan L., Gulyani S., Aldrich M., et al. (2000). Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy. Neuron 27, 469–474. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00058-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi P., Yu H., MacNeil D. J., Van der Ploeg L. H., Guan X. M. (1998). Distribution of orexin receptor mRNA in the rat brain. FEBS Lett. 438, 71–75. 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01266-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujino N., Yamanaka A., Ichiki K., Muraki Y., Kilduff T. S., Yagami K. I. (2005). Cholecystokinin activates orexin/hypocretin neurons through the cholecystokinin A receptor. J. Neurosci. 25, 7459–7469. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1193-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunematsu T., Fu L. Y., Yamanaka A., Ichiki K., Tanoue A., Sakurai T., et al. (2008). Vasopressin increases locomotion through a V1a receptor in orexin/hypocretin neurons: implications for water homeostasis. J. Neurosci. 28, 228–238. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3490-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrotti A., Carotenuto M., Altieri L., Parisi P., Tozzi E., Belcastro V., et al. (2015). Migraine and obesity: metabolic parameters and response to a weight loss programme. Pediatr. Obes. 10, 220–225. 10.1111/ijpo.245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrotti A., Di Fonzo A., Agostinelli S., Coppola G., Margiotta M., Parisi P. (2012). Obese children suffer more often from migraine. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 101, e416–e421. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02768.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viggiano A., Chieffi S., Tafuri D., Messina G., Monda M., De Luca B. (2014). Laterality of a second player position affects lateral deviation of basketball shooting. J. Sports Sci. 32, 46–52. 10.1080/02640414.2013.805236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viggiano A., Nicodemo U., Viggiano E., Messina G., Viggiano A., Monda M., et al. (2010). Mastication overload causes an increase in O 2 - production into the subnucleus oralis of the spinal trigeminal nucleus. Neuroscience 166, 416–421. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viggiano A., Vicidomini C., Monda M., Carleo D., Carleo R., Messina G., et al. (2009). Fast and low-cost analysis of heart rate variability reveals vegetative alterations in noncomplicated diabetic patients. J. Diabetes Complicat. 23, 119–123. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2007.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villano I., Messina A., Valenzano A., Moscatelli F., Esposito T., Monda V., et al. (2017). Basal forebrain cholinergic system and orexin neurons: effects on attention. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 11:10. 10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker L. C., Lawrence A. J. (2016). The role of orexins/hypocretins in alcohol use and abuse. Curr. Top Behav. Neurosci. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1007/7854_2016_55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayner M. J., Armstrong D. L., Phelix C. F., Oomura Y. (2004). Orexin-A (Hypocretin-1) and leptin enhance LTP in the dentate gyrus of rats in vivo. Peptides 25, 991–996. 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. H., Jensen L. T., Verkhratsky A., Fugger L., Burdakov D. (2007). Control of hypothalamic orexin neurons by acid and CO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10685–10690. 10.1073/pnas.0702676104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X., Crowder T. L., Yamanaka A., Morairty S. R., LeWinter R. D., Sakurai T. (2006). GABA(B) receptor-mediated modulation of hypocretin/orexin neurones in mouse hypothalamus. J. Physiol. 574, 399–414. 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T. R., Yang Y., Ward R., Gao L., Liu Y. (2013). Orexin receptors: multi-functional therapeutic targets for sleeping disorders, eating disorders, drug addiction, cancers and other physiological disorders. Cell. Signal. 25, 2413–2423. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka A., Beuckmann C. T., Willie J. T., Hara J., Tsujino N., Mieda M., et al. (2003a). Hypothalamic orexin neurons regulate arousal according to energy balance in mice. Neuron 38, 701–713. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00331-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka A., Muraki Y., Ichiki K., Tsujino N., Kilduff T. S., Goto K., et al. (2006). Orexin neurons are directly and indirectly regulated by catecholamines in a complex manner. J. Neurophysiol. 96, 284–298. 10.1152/jn.01361.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka A., Muraki Y., Tsujino N., Goto K., Sakurai T. (2003b). Regulation of orexin neurons by the monoaminergic and cholinergic systems. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 303, 120–129. 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00299-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Zou B., Xiong X., Pascual C., Xie J., Malik A., et al. (2013). Hypocretin/orexin neurons contribute to hippocampus-dependent social memory and synaptic plasticity in mice. J. Neurosci. 33, 5275–5284. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3200-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokobori E., Kojima K., Azuma M., Kang K. S., Maejima S., Uchiyama M., et al. (2011). Stimulatory effect of intracerebroventricular administration of orexin A on food intake in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Peptides 32, 1357–1362. 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Xue Zhang R., Tang S., Yan Ren Y., Xia Yang W., Liu X., et al. (2014). Orexin-A-induced ERK 1/2 activation reverses impaired spatial learning and memory in pentylenetetrazol-kindled rats via OX1R-mediated hippocampal neurogenesis. Peptides 54, 140–147. 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink A. N., Perez-Leighton C. E., Kotz C. M. (2014). The orexin neuropeptide system: physical activity and hypothalamic function throughout the aging process. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 8:211. 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]