Abstract

The spines of flowering plants are thought to function primarily in defence against mammalian herbivores; however, we previously reported that feeding by Manduca sexta caterpillars on the leaves of horsenettle plants (Solanum carolinense) induces increased development of internode spines on new growth. To determine whether and how spines impact caterpillar feeding, we conducted assays with three Solanaceous plant species that vary in spine numbers (S. carolinense, S. atropurpureum and S. aethiopicum) and also manipulated spine numbers within each species. We found that M. sexta caterpillars located experimentally isolated target leaves much more quickly on plants with experimentally removed spines compared with plants with intact spines. Moreover, it took caterpillars longer to defoliate species with relatively high spine numbers (S. carolinense and particularly S. atropurpureum) compared with S. aethiopicum, which has fewer spines. These findings suggest that spines may play a significant role in defence against insect herbivores by restricting herbivore movement and increasing the time taken to access feeding sites, with possible consequences including longer developmental periods and increased vulnerability or apparency to predators.

Keywords: defence, herbivores, spines, Manduca sexta, Solanaceae

1. Introduction

Plants have evolved diverse defence and tolerance mechanisms against herbivory, some of which occur constitutively, while others are expressed only or more strongly in response to feeding damage [1–3]. Extensive research has explored chemical plant defences, including those that act directly against feeding herbivores as well as indirect defences mediated by recruitment of herbivores’ natural enemies [4,5]. Somewhat less attention has been paid to structural adaptations, including the waxy plant cuticle, trichomes, spines and thorns, which can act as a first line of defence against herbivory [2,6,7]. Furthermore, work that has explored these structures has focused heavily on trichomes [6–9], while relatively few studies have explored the defensive functions of internode and leaf spines, despite their widespread prevalence in flowering plants [6].

Most studies addressing the defensive functions of spines have focused on their role in deterring mammalian herbivores [10–12]. For example, Acacia seyal trees suffered more extensive mammalian herbivory on branches from which spines were experimentally removed, and also exhibited more damage-induced spine growth on lower branches accessible to mammalian herbivores [12]. Recently, we documented the induction of increased internode spine numbers (as well as trichome numbers) in the herbaceous perennial weed Solanum carolinense (horsenettle) following feeding by Manduca sexta (tobacco hornworm) caterpillars [6]. Furthermore, we found that the constitutive and induced expression of these defence traits was influenced by genotypic variation and by inbreeding, with reduced numbers of internode spines in inbred relative to outbred progeny, accompanying other apparently deleterious effects of inbreeding on a wide range of defence traits [6,13–18]. Consistent with these effects of inbreeding, we also documented increased performance of M. sexta caterpillars on inbred plants [17,18]. This previous work did not directly explore whether or how the observed changes in plant spines influenced caterpillars; however, we hypothesized that spines may influence the ability of caterpillars to move about the plant—M. sexta caterpillars frequently change location on their host plants during development, feeding on different leaves in feeding cycles [19]—and thereby impact overall feeding performance.

Building on these observations, the current study explored the efficacy of internode spines in defence against Lepidopteran larvae. The consistent variation in spine numbers between inbred and outbred genotypes of S. carolinense provides a useful tool for this investigation; however, as noted above, inbred and outbred genotypes also vary in many other defence traits, making it difficult to isolate the effects of any single factor. We mitigated this difficulty to some extent by designing assays focused explicitly on the effects of spines on caterpillar movement (e.g. by measuring time taken to reach target leaves). In addition, we explored the effects of spines via two additional approaches: first by comparing caterpillar performance on Solanum species exhibiting natural variation in spine numbers and second by manipulating spine numbers experimentally.

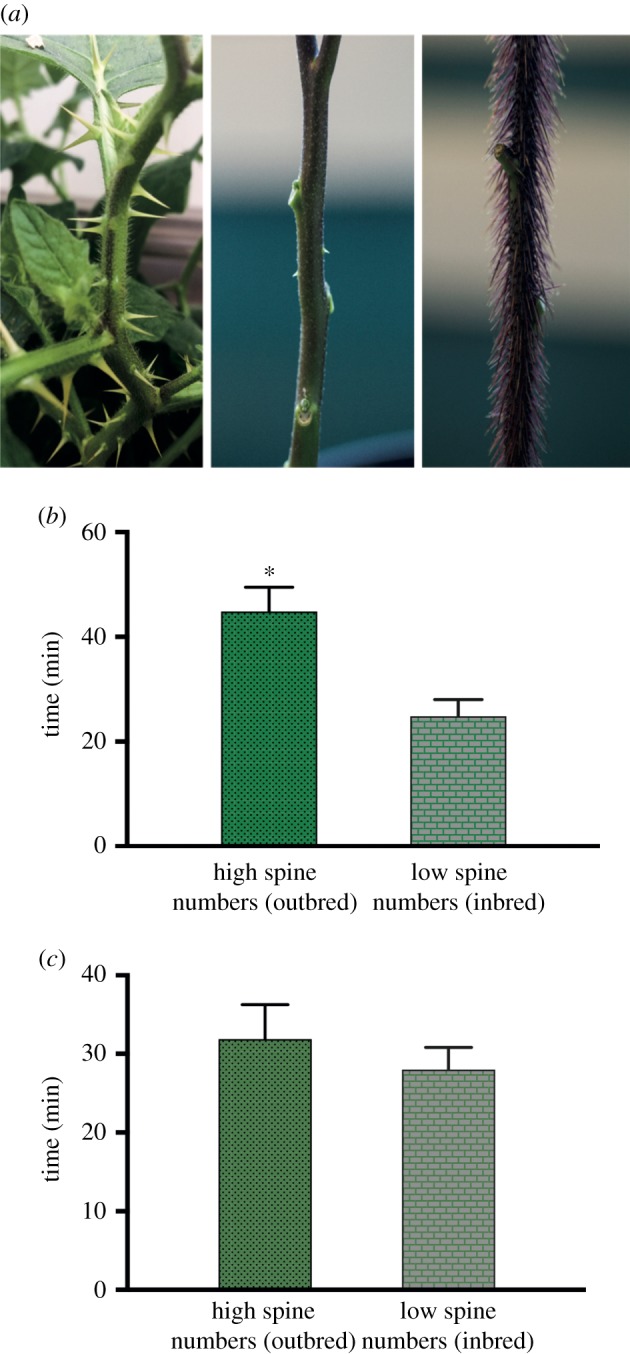

This study employed three wild species from the Solanum subgenus Leptostemonum (spiny solanums), including: S. carolinense, the focus of our previous work; S. aethiopicum (Ethiopian nightshade), which exhibits much lower spine numbers than S. carolinense; and S. atropurpureum (purple devil), which exhibits very high numbers of internode spines (figure 1a). As in our previous studies, M. sexta, a Solanaceae specialist that readily feeds on all three species, was the focal herbivore. In addition to measuring time taken to reach target leaves and initiate feeding on plants varying in spine numbers (breeding type or experimental manipulation; S. carolinense) we also measured the time taken by caterpillars to completely defoliate plants (S. aethiopicum, S. carolinense and S. atropurpureum), selecting this metric in preference to more commonly reported measures such as leaf area consumed per unit time, because preliminary experiments suggested it was an effective way to assess the effects of spines on caterpillars' ability to move about the plant to access leaf tissue.

Figure 1.

(a) Variation in internode spines on three Solanum species: Solanum carolinense, S. aethiopicum and S. atropurpureum. (b) Results of unpaired t-tests on time spent by third-instar M. sexta on high and low spine numbers S. carolinense plants to locate leaf. (c) Results of unpaired t-tests on time spent by third-instar M. sexta on S. carolinense plants to locate leaf after manipulating the spine numbers to be the same.

We note that none of the assays employed provides a perfect way to isolate the effects of spines on herbivore performance. Experimental removal of spines, for example, may result in induction of chemical plant defences—although we note that such induction is expected to work in opposition to the hypothesized effects of spine removal on caterpillar performance. Meanwhile, plant species and genotypes that exhibit natural variation in spine numbers also vary in other traits that may impact herbivores. Our approach was, therefore, to investigate the effects of spines on caterpillar performance (and specifically on their ability to navigate the host plant) using a range of approaches in hopes of revealing a consistent overall pattern of effects, which is indeed evident in the results described below.

2. Material and methods

(a). Plant materials

Solanum carolinense plants were produced via controlled pollination of flowers from a set of 16 maternal plants collected near State College, PA, USA, with self- and cross-pollinations resulting in inbred and outbred progeny; for more details, see [6,14,15]. Previous work on this population has shown that both physical and chemical defences are compromised by inbreeding [6,14–18,20]. Seeds from three randomly selected maternal families were grown under greenhouse conditions and transplanted into 6″ pots after 20 days (two to four true-leaf stage). Seeds of S. atropurpureum and S. aethiopicum, donated by Zürich Botanisher Garten, Zürich, Switzerland, were grown similarly. Experimental plants, selected from a large nursery six to eight weeks after transplanting, were of similar size and growth stage.

(b). Insects

Manduca sexta eggs were obtained from Carolina Biological Supply (Burlington, NC, USA) and from the Max Plank Institute for Chemical Ecology (Jena, Germany). Caterpillars were reared in a growth chamber on a wheat-germ–based artificial diet (Frontier Agricultural Sciences, NE, USA). Third-instar caterpillars were used for all experiments. For each experiment, the caterpillars used were from a single batch of eggs and were of similar size.

(c). Time to reach target leaves

To examine the effects of spine numbers on caterpillars' ability to traverse the stem to reach leaves, we removed all leaves except the youngest fully developed one from 40 outbred and 26 inbred S. carolinense plants (10–15 genets each from three maternal families) with varying spine densities but otherwise similar size and form. Mean spine numbers on these plants were assessed, and a single third-instar caterpillar was placed at soil level and allowed to climb up the stem to find the leaf. Time taken to reach the leaf was recorded. Next, we selectively removed spines from the experimental plants to obtain pairs of inbred and outbred plants with uniform spine numbers and repeated the same bioassay with new caterpillars. (To avoid potential bias some spines were removed from inbred as well as outbred plants.) Spines were carefully removed with a sharp razor blade, avoiding damage to the stem epidermis and we confirmed that each plant pair (inbred and outbred) had an equal number and similar distribution of spines. Following spine removal, plants were returned to the growth chamber then used for experiments within a few hours to minimize any physiological effects of the manipulation.

(d). Time to whole-plant defoliation

To further explore the effect of spines on caterpillar movement and performance, we assessed the time required for M. sexta caterpillars to completely defoliate plants of three Solanaceous species that exhibit natural variation in spine numbers (S. carolinense, S. atropurpureum and S. aethiopicum), both with intact spines and with all spines experimentally removed (N = 15 intact and 15 spines removed for each species). We paired intact and manipulated plants, placed seven third-instar caterpillars on each plant and monitored the plants several times each day. Because caterpillars on S. atropurpureum fell off the plants frequently, we manually placed them back onto the plants to ensure continuous feeding; however, we also ran a similar assay with S. atropurpureum (comparing plants with intact versus removed spines) in which caterpillars that fell off the plant were not replaced (N = 6 pairs).

(e). Spine weight

To quantify differences in spines among our three focal species, we collected all spines from eight plants of each species, dried them at 100°C for 24 h, then weighed them to determine spine weight per plant.

(f). Statistical analyses

Data from the target-leaf assay were analysed via unpaired t-tests. Data from experiments with manipulated spine numbers were analysed with paired t-tests. Time-to-defoliate experiments were analysed via two-way ANOVA, with time as the response variable and plant species and treatment (spines intact or spines removed) as the factors, followed by post hoc pairwise comparisons between intact- and removed-spine pairs for each species. Spine weight was analysed via one-way ANOVA, with weight as the response variable and plant species as factor, followed by post hoc comparisons. All data were subjected to appropriate transformations to meet normality assumptions. Analyses were carried out using the statistical software Graph Pad Prism (La Jolla, CA, USA).

3. Results

(a). Time to reach target leaves

Manduca sexta caterpillars took significantly longer to reach target leaves on outbred S. carolinense plants (unpaired t-tests; t = 2.33, d.f. = 64, p = 0.022; figure 1b), which, as expected, had significantly higher spine numbers compared with inbred plants (unpaired t-tests; t = 3.38; d.f. = 64, p = 0.001; electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Although inbred and outbred plants are also expected to differ in other defence traits, manipulation of spine numbers eliminated differences in the time required for caterpillars to reach the target leaf (paired t-tests; t = 0.527, d.f. = 25, p = 0.602; figure 1c), consistent with the hypothesis that spine number was responsible for the effects observed in the previous assay.

(b). Time to defoliation

Consistent with our initial expectations, S. atropurpureum had the highest spine weight (0.144 ± 0.008; means and s.e.) followed by S. carolinense (0.093 ± 0.003) and S. aethiopicum (0.022 ± 0.001; figure 2a). This pattern was reflected in the time taken to defoliate plants, with caterpillars taking longest to defoliate S. atropurpureum (even when caterpillars that fell from the plant were replaced) followed by S. carolinense and then S. aethiopicum (two-way ANOVA: F = 33.35, p < 0.000; electronic supplementary material, table S1). Furthermore, for both S. carolinense and S. atropurpureum, experimental removal of spines resulted in a significant decrease in the time to defoliation, whereas no significant effect of spine removal was observed for S. aethiopicum, the species with the lowest spine weight (two-way ANOVA: F = 8.99, p = 0.004; figure 2b; electronic supplementary material, table S1). When the (numerous) caterpillars that fell from intact S. atropurpureum plants were not replaced, we observed a dramatic effect in which plants with spines removed were completely defoliated within 24 h, while intact plants suffered less than 50% defoliation over the same period.

Figure 2.

(a) Results of one-way ANOVA on total spine weight of three Solanum species, (b) Results of two-way ANOVA on time to defoliate by M. sexta third-instar caterpillars on three Solanum species with intact spines or spines removed experimentally.

4. Discussion

Our findings clearly demonstrate spines can act as an effective defence against caterpillar feeding by restricting caterpillar movement, and in at least some cases by displacing caterpillars from the plant entirely. The dense spines of S. atropurpureum, for example, were particularly effective at disrupting feeding by M. sexta caterpillars, which typically move between leaves between bouts of feeding [19]. Furthermore, while variation in other traits between the plant species and genotypes employed here may be expected to influence herbivore performance, the consistent and complementary results observed across our different experiments (with respect to variation in spine numbers) confirm that spines are playing an important role. For example, differences in caterpillar performance observed in experiments comparing (unmanipulated) inbred and outbred S. carolinense plants disappeared when the spine numbers of outbred plants were manipulated to be similar to those of inbred plants.

In Solanaceae, glandular and non-glandular trichomes, along with toxic secondary metabolites, are the most studied modes of defence [6,7]. The current findings suggest that spines can also play an important role in pre-ingestive defence, as do trichomes [9,10,15], by preventing and/or delaying access to vulnerable plant parts (electronic supplementary material, video S1). In addition to potentially displacing caterpillars from the plant, such effects may benefit plants by reducing the amount of damage incurred during the time required for the implementation of induced defences or by slowing the development of herbivores and consequently increasing the vulnerability of early developmental stages to predation or other sources of mortality [21]. Furthermore, even where caterpillars have completed development, the effects of spines on caterpillar growth rates may impact moulting, pupation and adult size or quality, with potential implications for dispersal or mating success [18]. The significant variation in spine numbers observed among the three species tested probably reflect different overall strategies against herbivory, a topic we are currently exploring.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Scott Diloreto, Erica Smyers and Aisling Ryan for plant and insect care.

Data accessibility

Data available from the Dryad http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.4781n [22].

Authors' contributions

R.R.K. and M.C.M. designed the study; R.R.K. collected and analysed data and drafted the manuscript. S.B.H. collected data and contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. M.C.M. and C.M.D.M. supervised the research and contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. All authors approve publication and agree to be accountable for this work.

Funding

This research was supported by the start-up grant for C.M.D.M. from ETH, Zürich.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Howe GA, Jander G. 2008. Plant immunity to insect herbivores. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 41–66. ( 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092825) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gish M, De Moraes CM, Mescher MC. 2015. Herbivore-induced plant volatiles in natural and agricultural ecosystems: open questions and future prospects. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 9, 1–6. ( 10.1016/j.cois.2015.04.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strauss SY, Agrawal AA. 1999. The ecology and evolution of plant tolerance to herbivory. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14, 179–185. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01576-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Moraes CM, Lewis WJ, Paré PW, Alborn HT, Tumlinson JH. 1998. Herbivore-infested plants selectively attract parasitoids. Nature 393, 570–573. ( 10.1038/31219) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heil M. 2001. Extrafloral nectar production of the ant-associated plant, Macaranga tanarius, is an induced, indirect, defensive response elicited by jasmonic acid. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 1083–1088. ( 10.1073/pnas.031563398) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kariyat RR, Balogh CM, Moraski RP, De Moraes CM, Mescher MC, Stephenson AG. 2013. Constitutive and herbivore-induced structural defenses are compromised by inbreeding in Solanum carolinense (Solanaceae). Am. J. Bot. 100, 1014–1021. ( 10.3732/ajb.1200612) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanley ME, Lamont BB, Fairbanks MM, Rafferty CM. 2007. Plant structural traits and their role in anti-herbivore defence. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 8, 157–178. ( 10.1016/j.ppees.2007.01.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valverde PL, Fornoni J, Nunez-Farfan J. 2001. Defensive role of leaf trichomes in resistance to herbivorous insects in Datura stramonium. J. Evol. Biol. 14, 424–432. ( 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00295.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medeiros L, Moreira GR. 2002. Moving on hairy surfaces: modifications of Gratiana spadicea larval legs to attach on its host plant Solanum sisymbriifolium. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 102, 295–305. ( 10.1046/j.1570-7458.2002.00950.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myers JH, Bazely DR. 1991. Thorns, spines, prickles and hairs: are they stimulated by herbivory and do they deter herbivores? In Phytochemical induction by herbivores (eds Tallamy W, Raupp MJ), pp. 325–344. New York, NY: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper SM, Owen-Smith N. 1986. Effects of plant spinescence on large mammalian herbivores. Oecologia 68, 446–455. ( 10.1007/bf01036753) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milewski AV, Young TP, Madden D. 1991. Thorns as induced defenses: experimental evidence. Oecologia 86, 70–75. ( 10.1007/bf00317391) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kariyat RR, Mauck KE, De Moraes CM, Stephenson AG, Mescher MC. 2012. Inbreeding alters volatile signaling phenotypes and influences tri-trophic interactions in horsenettle (Solanum carolinense L.). Ecol. Lett. 15, 301–309. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01738.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kariyat RR, Mena-Alí J, Forry B, Mescher MC, De Moraes CM, Stephenson AG. 2012. Inbreeding, herbivory, and the transcriptome of Solanum carolinense . Entomol. Exp. Appl. 144, 134–144. ( 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2012.01269.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kariyat RR, Smith JD, Stephenson AG, De Moraes CM, Mescher MC. 2017. Non-glandular trichomes of Solanum carolinense deter feeding by Manduca sexta caterpillars and cause damage to the gut peritrophic matrix. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20162323 ( 10.1098/rspb.2016.2323) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delphia CM, Rohr JR, Stephenson AG, De Moraes CM, Mescher MC. 2009. Effects of genetic variation and inbreeding on volatile production in a field population of horsenettle. Int. J. Plant Sci. 170, 12–20. ( 10.1086/593039) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delphia CM, De Moraes CM, Stephenson AG, Mescher MC. 2009. Inbreeding in horsenettle influences herbivore resistance. Ecol. Entomol. 34, 513–519. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2311.2009.01097.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Portman SL, Kariyat RR, Johnston MA, Stephenson AG, Marden JH. 2015. Cascading effects of host plant inbreeding on the larval growth, muscle molecular composition, and flight capacity of an adult herbivorous insect. Funct. Ecol. 29, 328–337. ( 10.1111/1365-2435.12358) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds SE, Yeomans MR, Timmins WA. 1986. The feeding behaviour of caterpillars (Manduca sexta) on tobacco and on artificial diet. Physiol. Entomol. 11, 39–51. ( 10.1111/j.1365-3032.1986.tb00389.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portman SL, Kariyat RR, Johnston MA, Stephenson AG, Marden JH. 2015. Inbreeding compromises host plant defense gene expression and improves herbivore survival. Plant Signal. Behav. 10, e998548 ( 10.1080/15592324.2014.998548) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zalucki MP, Clarke AR, Malcolm SB. 2002. Ecology and behavior of first-instar larval Lepidoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 47, 361–393. ( 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145220) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kariyat RR, Hardison SB, De Moraes CM, Mescher MC. 2017. Data from: Plant spines deter herbivory by restricting caterpillar movement. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.4781n) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Kariyat RR, Hardison SB, De Moraes CM, Mescher MC. 2017. Data from: Plant spines deter herbivory by restricting caterpillar movement. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.4781n) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the Dryad http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.4781n [22].