Abstract

We have developed a locus-specific DNA target preparation method for highly multiplexed single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping called MARA (Multiplexed Anchored Runoff Amplification). The approach uses a single primer per SNP in conjunction with restriction enzyme digested, adapter-ligated human genomic DNA. Each primer is composed of common sequence at the 5′ end followed by locus-specific sequence at the 3′ end. Following a primary reaction in which locus-specific products are generated, a secondary universal amplification is carried out using a generic primer pair corresponding to the oligonucleotide and genomic DNA adapter sequences. Allele discrimination is achieved by hybridization to high-density DNA oligonucleotide arrays. Initial multiplex reactions containing either 250 primers or 750 primers across nine DNA samples demonstrated an average sample call rate of ∼95% for 250- and 750-plex MARA. We have also evaluated >1000- and 4000-primer plex MARA to genotype SNPs from human chromosome 21. We have identified a subset of SNPs corresponding to a primer conversion rate of ∼75%, which show an average call rate over 95% and concordance >99% across seven DNA samples. Thus, MARA may potentially improve the throughput of SNP genotyping when coupled with allele discrimination on high-density arrays by allowing levels of multiplexing during target generation that far exceed the capacity of traditional multiplex PCR.

INTRODUCTION

Long before the completion of the human genome sequence, it was clear that sites of genetic variation could be used as markers to identify disease segregation patterns among families (1). This approach led to the identification of a number of genes involved in rare, monogenic disorders. With the complete sequence now available (2,3), attention has turned to the challenge of identifying common disease genes. Although multiple sources of genetic variation occur among individuals, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are emerging as the marker of choice for genetic association studies due to their abundance, stability and relative ease of scoring. Additionally, the ongoing international effort to build a haplotype map will identify a standard set of common-allele SNPs that are expected to provide the framework for new genome-wide studies designed to identify the underlying genetic basis of complex diseases, pathogen susceptibility and differential drug responses (4). Owing to these wide-ranging applications, there is still a need for the development of robust, flexible, cost-effective technology platforms for scoring SNP genotypes in large numbers of samples.

There are a multitude of genotyping methodologies for SNPs that have been described over the years (5–7). These approaches can vary in terms of how alleles are discriminated, e.g. the use of nucleic acid hybridization with short oligonucleotide probes alone or in combination with enzymes such as DNA polymerases or DNA ligases. Additionally, these approaches can vary in the nature of both the assay formats and labeling and detection strategies. However, many currently used approaches share a common feature in that there is a requirement for an amplification of the region harboring the polymorphism prior to actual genotyping. PCR significantly increases the copy number of the sequence to be genotyped, thereby effectively reducing the complexity of the target sequences and improving the ability to differentiate correct and incorrect genotype calls. Traditionally, standard multiplex PCR is difficult to design and enable at levels beyond several dozen loci per reaction (8). Even with careful optimization of input reagents (9) and efforts to minimize non-specific primer dimers (10), multiplex PCR is not a routine laboratory technique. A number of alternative approaches to standard multiplex PCR have been described over the years. These include the use of universal primer sequences added to the ends of locus-specific sequences (11), the use of PCR suppression in which one target-specific primer is used in conjunction with a primer common to adapters present on all DNA fragments (12,13) and the use of acrylamide spheres with covalently attached primers for solid-phase PCR amplification (14). While these methods do improve multiplexing levels as compared with standard approaches, none of the described methods has demonstrated reactions >100-plex and thus are still of moderate utility for a high-throughput SNP genotyping setting. New methods, such as molecular inversion probe genotyping, in which probes over 100 nt in length are used in combination with enzymatic single base extension and ligation, have demonstrated genotyping at 1000-plex with high accuracy (15) but involves a complex protocol with multiple steps. While genotyping approaches have been described using unamplified human genomic DNA, such as the invasive cleavage reaction on microspheres (16), it is limited in practice by the requirement for large quantities (25 μg) of input genomic DNA and, therefore, is not well suited for high-throughput analysis. Thus, one of the continuing challenges in SNP genotyping is the development of molecular methods capable of amplifying locus-specific SNPs in a highly multiplexed manner.

Estimates for the number of SNPs that need to be genotyped for whole genome association studies using large population-based samples may range from 100 000 to 1 000 000 depending on whether haplotype tagging SNPs (htSNPs) or random, evenly spaced SNPs are used (4,17,18). In order to leverage the power of SNPs in genetic studies, novel target preparation methods need to be developed that, when combined with methods for allele discrimination, allow rapid and accurate genotypic information at a fraction of the cost of current approaches. High-density arrays provide a method for allele discrimination and have been used successfully for SNP discovery and genotyping with target preparations ranging from locus-specific multiplex PCR (19) to single primer assays which reproducibly amplify a subset of the human genome (20–23). These arrays use photolithography to synthesize hundreds of thousands of different probe sequences in a highly parallel manner to defined addressable locations on a glass substrate (24–26).

In this report, we describe the development of a target preparation method for highly multiplexed SNP genotyping termed MARA (Multiplexed Anchored Runoff Amplification) that is combined with allele discrimination based on hybridization of DNA target to high-density oligonucleotide arrays. We have evaluated MARA reactions at primer multiplex levels between 250- and 4300-plex. At levels of multiplexing over 1000-plex, >75% of the input oligonucleotides generate DNA target such that the targeted SNPs show a call rate and concordancy of >95 and 99%, respectively, across a panel of DNA samples. These results suggest that MARA may serve as a target preparation method for highly multiplexed locus-specific SNP genotyping that far exceeds the capacity of standard traditional multiplex PCR. When coupled with a method for allelic discrimination such as high-density array hybridization, this method provides access to large numbers of locus-specific SNPs in a single reaction and thus may facilitate the use of SNPs in genome-wide association studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotide design and synthesis

Locus-specific oligonucleotides were designed using Primer 3 (27). All oligonucleotides contained 23 bases of common sequence at the 5′ end (T3 promoter: 5′-AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGA-3′) followed by ∼25 bases of locus-specific sequence at the 3′ end. Primers were designed using the July 2003 human reference sequence based on NCBI Build 34 that was produced by the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Operon Biotechnologies (Alameda, CA), de-salted, normalized to a concentration of either 200 μm (p502 primers) or 300 μm (chr21 primers) with TE (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA) and stored at −20°C. All oligonucleotides <50 bases were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Universal primers [high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) purified] used in secondary PCR amplifications were T3 (5′-AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGA-3′) and T7 (5′-GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC-3′). Oligonucleotides designed as MseI adapters were 5′-GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAGCGTGGTCGCGGCCGAGGT-3′ (PAGE purified) and 5′-pTAACCTCGGC-NH2-3′ (HPLC purified). Oligonucleotides designed as Sau3AI adapters were 5′-GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAGCGTGGTCGCGGCCGAGGT-3′ (PAGE purified) and 5′-pGATCACCTCGGC-NH2-3′ (HPLC purified). Oligonucleotides designed as adapters were resuspended in TE at 100 μM and annealed to one another in a 20 μl reaction containing 900 pmol of each strand, 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2 and 30 mM NaCl. Reactions were capped with mineral oil, heated at 95°C for 5 min in a heat block and allowed to slowly cool to room temperature over 1 h.

Genomic DNA

All genomic DNA samples were purchased from NIGMS Human Genetic Cell Repository, Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, NJ). DNA samples used for MARA (p502 array) were NA10848, NA12671, NA12672, NA04477, NA04479, NA05995, NA07057, NA10830 and NA10831. DNA samples used for MARA (chr21 array) came from the DNA Polymorphism Discovery Resource (PD24) panel (28) and included NA15215, NA15223, NA15245, NA15236, NA15510, NA15213 and NA15590. DNA samples comprising the two trios were NA12455, NA12456 and NA12457 (Family 1356), and NA10838, NA10839 and NA 11997 (Family 1420).

MARA

Genomic DNA (100 ng) was digested with MseI (NEB) or Sau3AI (NEB) in a 20 μl reaction for 6 h at 37°C. MseI digestions were performed in 1× NEBuffer 2 (50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.9 at 25°C), 100 μg/ml BSA, with 5 U MseI. Sau3AI digestions were performed in 1× NEBuffer Sau3AI (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Bis Tris Propane–HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.0 at 25°C), 100 μg/ml BSA, with 6 U Sau3AI. Both enzyme digestions were heat inactivated at 65°C for 20 min. Adapters were ligated to genomic DNA in 20 μl reactions containing 100 ng of restriction enzyme digested genomic DNA in 1× T4 DNA ligase buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP and 25 μg/ml BSA], 0.1 μM adapters and 320 U T4 DNA ligase for 8 h at 16°C. Reactions were heat inactivated at 65°C for 10 min.

Primary MARA 250- and 750-plex reactions were carried out in a thermal cycler in a total volume of 25 μl containing 20 ng adapter-ligated genomic DNA, 250 μM of each dNTP (dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP), 1× GeneAmp PCR Gold Buffer (15 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1.25 U AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems) and 1.25 U Perfect Match PCR Enhancer (Stratagene). The final concentration of each locus-specific primer was 0.16 μM (250-plex) and 0.05 μM (750-plex). Primary MARA 4365-plex reactions were carried out in a total volume of 60 μl containing 60 ng adapter-ligated genomic DNA, 250 μM of each dNTP (dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP), 1× GeneAmp PCR Gold Buffer (15 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.025 μM of each locus-specific oligonucleotide, 1.25 U AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems) and 1.25 U Perfect Match PCR Enhancer (Stratagene). Primary MARA ∼1100-plex (x4) reactions were performed in four separate reactions as described for 4365-plex, and subsequently reactions were pooled prior to the secondary PCR. Conditions for primary MARA amplifications were as follows: 1 cycle of 95°C for 7 min, followed by 18 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 68°C for 2.5 min (−0.5°C per cycle) and 72°C for 60 s. The annealing and elongation times were increased to 5 and 2 min, respectively, per cycle for 4365-plex MARA. An enrichment step was carried out only on the 250-plex reactions following the primary reaction. T7 primer was added to the primary reactions to a final concentration of 1 μM, and the reactions underwent 1 PCR cycle using the following conditions: 95°C for 2 min, 55°C for 30 s and 72°C for 2 min. The reactions were passed over Sephadex G-25 columns, and ExoI reactions were carried out in a total volume of 50 μl in 1× Exonuclease I buffer [67 mM Glycine-KOH (pH 9.5), 6.7 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol] and 10 U Exonuclease I (NEB) for 30 min at 37°C, followed by heat inactivation at 80°C for 20 min. Reactions were purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit, and eluted in 30 μl of EB buffer.

Secondary amplification reactions for MARA 250- and 750-plex were carried out in a total volume of 100 μl containing 250 μM of each dNTP (dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP), 1× GeneAmp PCR Gold Buffer (15 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.8 μM T3 primer, 0.8 μM T7 primer and 5 U AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems). Secondary reactions used an aliquot of the primary reactions as template: 1 μl (250-plex) or 1 μl of 1:125 dilution (750-plex). Conditions for secondary amplifications were as follows: 1 cycle of 95°C for 7 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 55°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s, followed by 72°C for 7 min. Negative control reactions were carried out as described above, except that no locus-specific primers were used during the primary MARA reaction.

Secondary amplification reactions for MARA 1100-plex (x4) and 4365-plex were carried out in a total volume of 100 μl containing 250 μM of each dNTP (dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP), 1× Titanium Taq PCR Buffer [40 mM Tricine–KOH (pH 8.0 at 25°C), 16 mM KCl, 3.5 mM MgCl2 and 3.75 μg/ml BSA], 0.8 μM T3 primer, 0.8 μM T7 primer and 1 μl Titanium Taq DNA Polymerase (BD Biosciences Clontech). Secondary reactions used a 0.1 μl aliquot of the primary reaction as template. Secondary PCR for the 1100- and 4365-plex chr21 MARA also contained 1 M betaine (29,30). Conditions for secondary amplifications were as follows: 1 cycle of 95°C for 7 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 55°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s, followed by 72°C for 7 min.

Whole genome sampling assay (WGSA)

The assay is performed as described previously (21). DNA samples were hybridized to an array (p502) used in the development of the WGSA assay. This predecessor array used the same probe sequences and tiling strategy to generate genotype calls as the commercially available Affymetrix Gene Chip® 10K Mapping Xba_131 Array, and washing, staining and scanning for all samples were performed with the protocol as specified in the manufacturer's instructions (Affymetrix).

MARA Chr 21 genotype calls

Genotype calls were made using a likelihood based algorithm called the Dynamic Model (DM), which uses a P-value based confidence score to make genotype calls. This algorithm is currently used in the Affymetrix GeneChip® Mapping 100K Set and has been extensively validated (GeneChip Human Mapping 100K Set Data Sheet; http://www.affymetrix.com). The confidence score can be adjusted to allow genotyping calls to be made with either greater accuracy or higher call rates. DM has the ability to accurately genotype SNPs with low minor allele frequencies (<5%) in the absence of any predetermined SNP information (i.e. clustering patterns derived from a reference set).

RESULTS

MARA

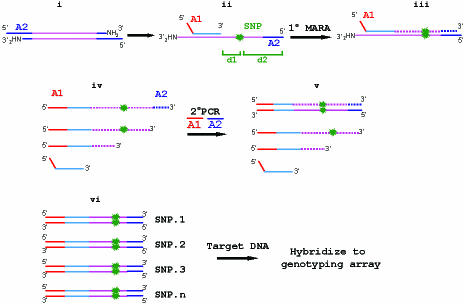

MARA is a method designed to generate locus-specific DNA target sequences in a highly multiplexed manner. An overview is shown in Figure 1. Each biallelic nucleotide is targeted with a single oligonucleotide primer that contains common sequence at the 5′ end (designated A1) followed by locus-specific sequence (∼25 bases) at the 3′ end. Each SNP requires a minimum of one primer which can either anneal to the top strand (reverse primer) or bottom strand (forward primer) of the genomic DNA target. The design of each oligonucleotide (and thus the location of the annealing site) is constrained by several parameters: (i) probe sequences tiled on the array (16 bases flanking the SNP on either side) are excluded from use in the primers and must not contain the restriction enzyme recognition sequence used to digest genomic DNA in MARA; (ii) the total length of the extension product [which is the sum of the distance of the primer annealing site to the SNP (d1 in Figure 1) and the distance of the SNP to the end of the adapter-ligated restriction fragment (d2 in Figure 1)] is >100 bases and <750 bases. After the primer anneals to the target and is elongated during the first cycle, the adapter sequences ligated to the genomic DNA are incorporated into the new extension product provided that elongation is complete through the end of the restriction fragment. Subsequent cycles of amplification are carried out over a range of annealing temperatures. A secondary amplification step is then carried out using an aliquot of the primary MARA reaction as template. Universal primers are used in the secondary amplification that anneal to common sites present in all full-length amplification products and thus secondary amplification is independent of the sequence of the individual locus-specific amplicons generated in the primary MARA reactions. The 100–750 bp size range helps to limit any variation in amplification efficiencies among the varying templates due to product length differences. Importantly, MARA does not require absolute specificity of primer annealing and elongation since target recognition and allele discrimination is achieved through hybridization to high-density arrays. Following the secondary amplification, the preparation of MARA target DNA for hybridization follows standard procedures in that the target DNA is enzymatically fragmented and 3′-biotin end-labeled with DNase I and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase (TdT), respectively.

Figure 1.

MARA (i) Human genomic DNA (pink) is digested to completion with a restriction enzyme and ligated to adapters (blue). The 3′ amino block helps to prevent background genomic DNA amplification. (ii) A MARA forward primer (containing common sequence A1) is shown annealing to the bottom strand of DNA upstream of a SNP (green symbol). (iii) The primary MARA reaction involves multiple cycles of primer annealing and extension, which can lead to a full-length extension product (dashed line) that has copied the adapter sequence (A2) from the genomic DNA template. (iv) At the completion of cycling, the reaction may contain unused primers as well as a mixture of both full-length extension products and truncated extension products that do not contain the copied A2 adapter. An enrichment step was used in the MARA 250-plex reactions following the primary reaction. One cycle of PCR with primer A2 converts full-length amplification products (which contain an A2 primer annealing site) into double-strand DNA, while incomplete products lacking the A2 primer annealing site are not converted into a double-stranded product. Exonuclease I digestion removes single strand products, while double-strand products are resistant to digestion. This step enriches for full-length products generated by the primary reaction, but cannot discriminate between products derived from specific and non-specific primer–target DNA annealing (v) The first cycle of secondary PCR allows primer A2 to convert full-length extension products (which contain an A2 primer annealing site) into double-stranded DNA, while partial extension products lacking the A2 primer annealing site are not converted into a double-stranded product. (vi) Subsequent cycles of secondary PCR with universal A1 and A2 primers amplify all full-length products derived from the first round locus-specific reaction. Target DNA is prepared for hybridization by enzymatic fragmentation with DNase I and end-labeling with TdT and biotin-ddATP.

MARA 250-plex

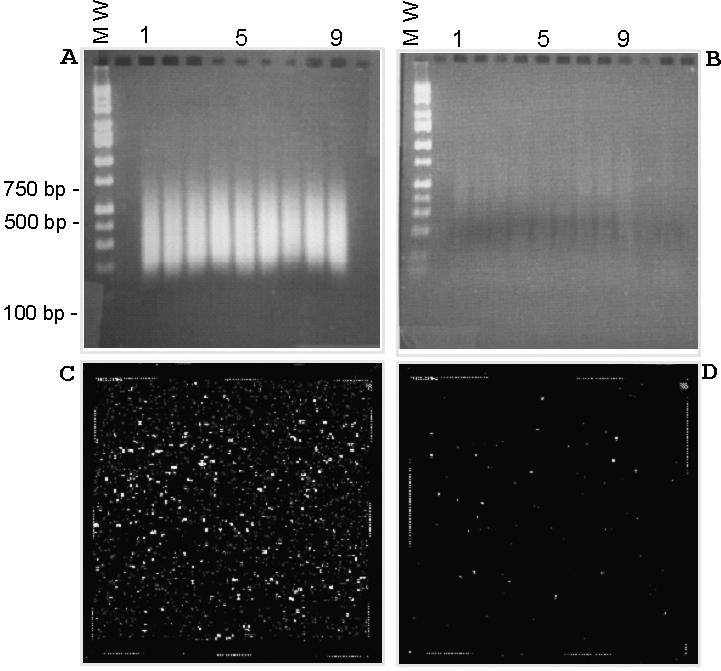

We initially used an array (designated p502) designed for WGSA in conjunction with EcoRI digestion or BglII digestion of human genomic DNA. The array contains probes for ∼3170 BglII SNPs and 4660 EcoRI SNPs. In order to test MARA, 250 WGSA EcoRI SNPs from this array were chosen in part because they exhibited reproducibly high call rates along with well-separated clusters representing all three genotype calls (AA, AB and BB) across a large collection of individuals (31). By pre-selecting robust SNPs that genotype accurately by allele-specific hybridization, we used genotype call rates as a surrogate for the presence (successful primer) or absence (unsuccessful primer) of MARA-generated target DNA. A total of 250 oligonucleotide primers were synthesized and combined, and then used in individual MARA reactions in conjunction with MseI digested, adapter-ligated genomic DNA (20 ng per reaction) from nine CEPH individuals. A small number of primers target amplicons containing more than one SNP tiled on the array, resulting in 28 additional SNPs to the original pool of 250 SNPs (278 total SNPs). Representative secondary universal amplification products are shown in Figure 2A. Each of the nine genomic DNA samples used in MARA show a reproducible smear from 150 to 550 bp when the 250 locus-specific primers are present. This result is consistent with the expected size distribution of products which ranges from 100 to 500 bp, with a mean size of 287 bp. As shown in Figure 2B, the yield of secondary amplification products is significantly reduced when the primary MARA reactions contain only adapter-ligated genomic DNA without the addition of locus-specific primers. Thus, MARA uncouples amplification of locus-specific sequences from a general, non-specific genome-wide amplification of input adapter-ligated restriction fragments. WGSA reactions using the restriction enzyme EcoRI were carried out as well for the nine individuals using the p502 array (4660 SNPs). Genotype calls for both MARA and WGSA target DNA preparations for all nine individuals were made using an automated algorithm (21). The hybridization results using target prepared by 250 primer-plex MARA were analyzed by discrimination score (DS) as well as call rate (percentage of successful genotype calls within a DNA sample). DS of a probe pair is the ratio of (PM − MM)/(PM + MM), where PM is the perfect match cell intensity and MM is the mismatch cell intensity, and thus serves as a measure of detection of DNA target sequences. Typically, if the DS for a SNP from a particular sample is <0.08, the specificity of the hybridization signal is considered weak. The accuracy of genotype calls using WGSA has previously been shown to be >99% (21,23), and thus an additional metric involved a comparison of MARA genotype calls with WGSA genotype calls in order to determine the concordancy of MARA calls with the alternative WGSA target preparation. The results of MARA 250 primer-plex are summarized in Table 1. A total of 99.4% of the SNPs targeted by locus-specific primers across nine individuals had a mean DS > 0.08. The targeted SNPs had a mean call rate of 96.2%, and mean concordance of 98.6% to WGSA genotype calls. In contrast, when locus-specific primers were omitted in the primary reaction, 6.6% (of the 258 SNPs) had a mean DS > 0.08. There was a mean call rate of 6.3%; however, only five of these SNPs were called across at least five of the nine DNA samples. These results show that the presence of locus-specific primers allows specific target sequences to be amplified, and in the absence of primers, only small quantities of non-specific products are generated.

Figure 2.

(A) 250-plex 2° PCR products separated on a 2%, 1× TBE agarose gel. (B) Negative control (no locus-specific primers) 2° PCR products separated on a 2%, 1× TBE agarose gel. (C) p502 chip image using 250 primer-plex 2° PCR products as target derived from input genomic DNA NA10830 (D) p502 chip image using negative control 2° PCR products as target derived from input genomic DNA NA10830.

Table 1. 250- and 750-plex MARA.

| Sample | 250-plex | 750-plex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS > 0.08 (%) | Call rate (%) | Concord (%) | DS > 0.08 (%) | Call rate (%) | Concord (%) | |

| NA10848 | 100 | 97.5 | 96.7 | 99.4 | 94.8 | 97.2 |

| NA12671 | 98.6 | 97.1 | 100 | 98.9 | 95.1 | 99.2 |

| NA12672 | 99.6 | 97.1 | 97.8 | 99.6 | 95.0 | 98.2 |

| NA04477 | 99.3 | 94.6 | 99.2 | 99.3 | 95.7 | 98.8 |

| NA04479 | 98.9 | 94.6 | 97.7 | 98.5 | 95.7 | 98.4 |

| NA05995 | 99.3 | 96.4 | 99.6 | 99.1 | 95.3 | 99.4 |

| NA07057 | 100 | 97.1 | 98.5 | 99.3 | 95.9 | 98.4 |

| NA10830 | 98.9 | 94.6 | 99.2 | 99.1 | 96.1 | 99.4 |

| NA10831 | 100 | 97.1 | 98.5 | 98.3 | 95.0 | 98.8 |

| Average | 99.4 | 96.2 | 98.6 | 99.0 | 95.4 | 98.7 |

DS of a probe pair is the ratio of (PM − MM)/(PM + MM), where PM is the intensity of the perfect match cell and MM is the intensity of the mismatch cell. The DS threshold of 0.08 is higher than the threshold value of 0.03 used in WGSA as a detection filter to identify weak hybridization signals (31). ‘Concord’ refers to the concordancy of MARA genotype calls with WGSA genotype calls.

MARA 750-plex

The multiplexing level was increased above 250 primer-plex by the addition of 500 primers to the original MARA 250-plex reactions; 250 (set A) of these additional primers targeted SNPs tiled on the p502 array, while the remaining 250 primers (set B) were designed for MARA and are compatible with MseI restriction enzyme digested genomic DNA but did not target p502-specific SNPs. Thus, 750 primers were present in individual reactions, but only 500 of the primers generated target hybridizing to the p502 array. A small number of the additional p502 (set A) primers target amplicons containing more than one SNP tiled on the array, resulting in an additional 7 SNPs to the 250 SNP pool (257 total from Set A). Thus, a total of 535 SNPs (278 + 257) on the p502 array are interrogated by the 750 primer-plex MARA reactions. Reactions using 20 ng input genomic DNA were carried out across the nine individual genomic DNA samples. The results of MARA 750 primer-plex are summarized in Table 1. A total of 99.0% of the p502 SNPs targeted by locus-specific primers had a mean DS > 0.08, along with a mean call rate of 95.4% and mean concordance of 98.7% to WGSA genotype calls. In contrast, when locus-specific primers were omitted in the primary reaction, 4.0% of the 535 SNPs across nine individuals had a mean DS > 0.08, along with a mean call rate of 3.6%.

Discordant SNP genotypes

The discordant genotype calls at the two multiplex levels were evaluated. The 250 primer-plex MARA reactions with nine DNA samples resulted in 2400 genotype calls (excluding no calls) that were compared with WGSA genotype calls. There were a total of 34 discordant calls that mapped to 10 distinct locus-specific primers, for an overall failure rate of <5% of the input primers. Two of these primers targeted more than one SNP. Of the 8 unique primers that each targeted only one SNP, there were no primers that gave a discordant genotype call across all nine samples; however one primer gave a discordant call in four of nine samples, three primers in three of nine samples, one primer in two of nine samples and three primers in only one of nine samples. Thus, the two primers which each target more than one SNP were responsible for 16 of the 34 total discordant calls. The 750 primer-plex MARA reactions with 9 DNA samples resulted in 4546 genotype calls (excluding no calls) that were compared with WGSA genotype calls. There were a total of 67 discordant calls that mapped to 32 distinct locus-specific primers, for an overall failure rate of <10% of the input primers targeting SNPs on the p502 array. A total of 29 of these 32 primers target only one SNP each. Of this set there were again no primers that gave a discordant genotype call across all 9 samples; however 2 primers gave a discordant call in 4 of 9 samples, 3 primers in 3 of 9 samples, 8 primers in 2 of 9 samples and 16 primers in only 1 of 9 samples. Thus, the 3 primers which each target more than one SNP were responsible for 18 of the 67 total discordant calls. A total of 9 of the 10 primers that failed in 250-plex MARA were also scored as failing in 750 primer-plex MARA. The single primer exception had only showed one discordant call across the 9 samples in 250-plex. For both multiplex levels, the mode of discordant calls was similar in that 94% (32/34) of the 250 primer-plex calls and 92% (56/61) of the 750 primer-plex calls were heterozygotes using WGSA target but homozygotes using MARA target.

MARA with chromosome 21 SNPS

In order to assess higher levels of multiplexing, a new array was designed containing 8936 SNPs from human chromosome 21, of which 4198 are defined as haplotype-defining SNPs (32). A total of 4365 oligonucleotides were designed for use in MARA in conjunction with Sau3AI restriction enzyme digested genomic DNA (60 ng per reaction), targeting a total of 4978 SNPs tiled on the array. The predicted in silico length of the amplification products ranged from a minimum of 120 bp to a maximum of 750 bp, with a median length of 400 bp. Multiplex reactions were carried out at 4365 primer-plex as well as using a random pooling of oligonucleotides into four separate groups of 1113-, 1140-, 1056- and 1056-plex [these reactions are referred to as ∼1100 primer-plex (x4) (Table 2)]. A total of seven DNA samples from the DNA Polymorphism Discovery Resource (28) were used and genotype calls were made using a likelihood based algorithm (X. Di, H. Matsuzaki, T. A. Webster, E. Hubbell, G. Liu, S. Dong, D. Bartell, J. Huang, R. Chiles, G. Yang et al., manuscript in preparation). This sample size of 14 chromosomes (seven DNA samples) has a 50% chance of detecting an allele with a frequency of 5%, and thus is sufficient to identify the majority of common variants. MARA genotype calls were compared with genotype calls from Perlegen Sciences that have been deposited into the public domain. The results for all 4978 SNPs are summarized in Tables 2 and 3 and are termed ‘pre-filter’ along with results for SNP subsets termed ‘post-filter’. The post-filter subsets of the 4978 SNPs were identified using selection criteria that required at least a 70% (5/7) call rate across the seven DNA samples. These filtering criteria led to subsets consisting of 3807 SNPs for the ∼1100-primer plex (x4) and 3908 SNPs for the 4365-primer plex MARA reactions. These two subsets showed considerable overlap with 3657 SNPs in common, representing 96% of the 1100-plex (x4) SNPs and 94% of the 4365-plex SNPs. The results show that the subsets, which represent 76.5% [1100-primer plex (x4)] and 78.5% (4365-primer plex) of the original targeted SNPs, have overall call rates >95% and concordances >99%. These SNP conversion rates also correspond closely to overall primer conversion rates. Thus, at both multiplex levels, over 3500 independent primers are generating specific target sequences. Table 4 contains an analysis of the MARA genotype calls and shows that the majority of the discordant calls were heterozygotes that were miscalled as homozygotes using MARA target. As a follow-up to this result, two trios were genotyped using 4365-plex MARA as an independent measure of genotype accuracy. Among the two trios, there were a total of 3270 SNPs in which each parent was homozygous for either the same or opposite genotype from one another (AA or BB). Assuming the parental genotype calls are correct, there were 26 SNPs (0.8%) in the two children with genotype calls inconsistent with Mendelian inheritance. Of these discordant SNPs, 23/26 (88.5%) were called homozygous although a heterozygous call was expected from parental genotypes. The remaining three discordant SNPs came from one trio, in which both parents were scored as AA homozygote but the child was scored as either AB or BB.

Table 2. 1100-plex(×4) MARA.

| Sample | Pre-filter (4976 SNPs) | Post-filter (3807 SNPs) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Called SNPs | Call rate (%) | Perlegen SNPs (a/b) | Concord (%) | Called SNPs | Call rate (%) | Perlegen SNPs (a/b) | Concord (%) | |

| NA15215 | 4112 | 82.6 | 2916/2970 | 98.2 | 3590 | 94.3 | 2587/2600 | 99.5 |

| NA15223 | 4245 | 85.3 | 3033/3052 | 99.4 | 3689 | 96.9 | 2898/2915 | 99.4 |

| NA15245 | 4112 | 82.6 | 1837/1857 | 98.9 | 3627 | 95.3 | 1770/1788 | 99.0 |

| NA15236 | 4192 | 84.2 | 2676/2719 | 98.4 | 3671 | 96.4 | 2573/2612 | 98.5 |

| NA15510 | 4208 | 84.6 | 2824/2878 | 98.1 | 3647 | 95.8 | 2482/2500 | 99.3 |

| NA15213 | 4207 | 84.5 | 2945/3002 | 98.1 | 3663 | 96.2 | 2612/2635 | 99.1 |

| NA15590 | 4249 | 85.4 | 2822/2862 | 98.6 | 3701 | 97.2 | 2500/2512 | 99.5 |

| Average | 4189 | 84.2 | 2722/2763 | 98.5 | 3655 | 96.0 | 2489/2509 | 99.2 |

a/b refers to (number of concordant calls)/(total number of calls compared).

Table 3. 4365-plex MARA.

| Sample | Pre-filter (4976 SNPs) | Post-filter (3908 SNPs) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Called SNPs | Call rate (%) | Perlegen SNPs (a/b) | Concord (%) | Called SNPs | Call rate (%) | Perlegen SNPs (a/b) | Concord (%) | |

| NA15215 | 4187 | 84.1 | 2964/3013 | 98.4 | 3711 | 95.0 | 2664/2684 | 99.3 |

| NA15223 | 4448 | 89.4 | 3437/3484 | 98.7 | 3843 | 98.3 | 3022/3040 | 99.4 |

| NA15245 | 4299 | 86.4 | 2086/2135 | 97.7 | 3793 | 97.1 | 1870/1889 | 99.0 |

| NA15236 | 4355 | 87.5 | 3001/3086 | 97.3 | 3815 | 97.6 | 2670/2712 | 98.5 |

| NA15510 | 4240 | 85.2 | 2842/2892 | 98.3 | 3761 | 96.2 | 2546/2561 | 99.4 |

| NA15213 | 4278 | 86.0 | 2993/3059 | 97.8 | 3772 | 96.5 | 2683/2711 | 99.0 |

| NA15590 | 4271 | 85.8 | 2817/2860 | 98.5 | 3791 | 97.0 | 2530/2548 | 99.3 |

| Average | 4297 | 86.4 | 2877/2933 | 98.1 | 3784 | 96.8 | 2569/2592 | 99.1 |

a/b refers to (number of concordant calls)/(total number of calls compared).

Table 4. Genotype call cross-table.

| Perlegen | 1100-plex (x4) MARA | 4365-plex MARA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | AB | BB | NC | AA | AB | BB | NC | |

| AA | 7831 | 17 | 1 | 156 | 8056 | 17 | 0 | 105 |

| AB | 75 | 5939 | 25 | 429 | 85 | 6153 | 36 | 409 |

| BB | 1 | 22 | 3652 | 95 | 1 | 21 | 3776 | 65 |

Cross-table comparison of genotype calls from Perlegen Sciences (designated in bold) with subset of MARA genotype calls using two different primer multiplex levels during the first round of MARA.

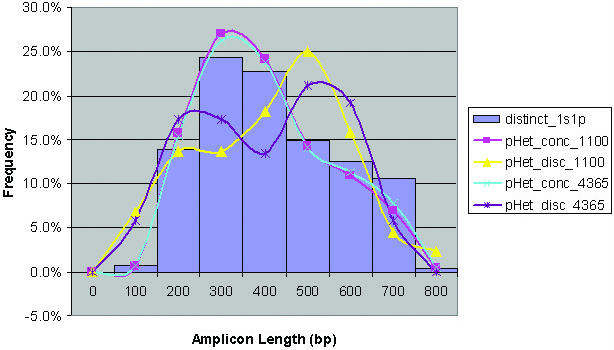

Several parameters were evaluated in an attempt to determine whether there were any differences between SNPs (and corresponding primers) that belonged to the filtered subset and those that did not. There were no observable differences between the groups with regard to G:C% of the primers, G:C% of the probes tiled on the array, and G:C% and length of the Sau3AI genomic DNA restriction fragments. We also attempted to determine whether there were differences between known heterozygous SNPs from the filtered subset that were concordant versus discordant with known reference genotype calls. There was a difference in the length of the extension products, with a higher relative percentage of the SNPs belonging to the discordant group present on extension products in the range of 600–800 bp (Figure 3). In summary, the chromosome 21 MARA results show that ∼75% of the input primers function at multiplex levels >1000 bp. Interestingly, the overall primer conversion rates do not differ significantly between 1100 primer-plex (x4) and 4365 primer-plex, suggesting that non-specific primer–primer interactions at the higher multiplex level may not solely be responsible for failed target generation.

Figure 3.

Histogram of amplicon sizes (shown in blue) expected with 4365-plex MARA and Sau3AI digested genomic DNA. Amplicons do not include the 42 bp contributed by the genomic DNA adapter. The amplicon size distribution for heterozygous SNPs that are concordant and discordant from 4365-plex and 1100-plex (x4) MARA is shown. Only primers that map to single SNPs were used for analysis. Extension product lengths corresponding to SNPs that are concordant [1100-plex (x4) are pink (square) and 4365-plex are blue (cross)] and discordant [1100-plex (x4) are yellow (triangle) and 4365-plex are purple (asterisk)] are shown.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we describe a highly multiplexed DNA target preparation method termed MARA. The key finding of this report is that multiplexing of over 4000 independent primers showed a subset of ∼75% of the input total which demonstrated high SNP call rates and concordance across multiple individuals. When MARA is combined with a method for highly parallel allele discrimination, such as high-density DNA oligonucleotide array hybridization, it affords a level of locus-specific SNP genotyping that is not readily accessible through traditional target preparation methods such as multiplex PCR. The basis for the target preparation with MARA is annealing of a single adapter containing locus-specific primer to a restriction fragment ligated to a distinct adapter sequence. As the primer is elongated through the end of the restriction fragment, the adapter is copied to the 3′ end of the extension product. Thus, unique locus-specific products are all in a form that allows re-amplification in a universal secondary reaction using a pair of common primers. Importantly, unwanted generic amplification of all input genomic DNA restriction fragments is uncoupled from amplification of selected fragments harboring SNPs of interest that are targeted with locus-specific primers, resulting in a reduced-complexity DNA fraction containing sequences of interest. Improvements in the MARA biochemistry that lead to longer extension products should provide additional flexibility with subsequent primer design.

There are several flexible components of MARA that include the design of oligonucleotide primers and the choice of the restriction enzyme for genomic DNA digestion. One of the inherent limitations in any locus-specific genotyping platform is the requirement for oligonucleotide design and synthesis. In standard multiplex PCR, the number of potential PCR products in a reaction of n primer pairs grows as 2n2 + n (33). Thus, minimizing or all together eliminating the tendency for primer cross-reactivity is at the center of the challenge of multiplex PCR. Padlock probe reactions which convert a linear probe into a circular probe significantly overcome this issue, however, these probes are typically quite long (over 100 bases) and probe quality has a major influence on assay performance (15,34). MARA requires a minimum of only one locus-specific primer per SNP, and thus while the potential for non-specific primer–target and primer–primer interactions is present, the total number of primers used for target preparation is reduced as compared with multiplex PCR. With MARA, allele discrimination is achieved by hybridization to arrays containing SNP-specific complementary sequences rather than a universal array which requires the use of tags or zip codes attached to the primers for genotype de-convolution (15,35). Thus, the requirement for absolute specificity of primer annealing to target sequences in genomic DNA is alleviated. This allows the range of annealing temperatures to be expanded using a ‘touchdown’ format during the primary reaction, increasing the likelihood that any given primer will bind specifically to genomic DNA (36,37). The theoretical sequence complexity of target DNA generated by MARA is approximately equal to the average length of the amplification products multiplied by the level of primer multiplexing. In the case of the 4365-plex MARA, this is ∼2 Mb. The high-density genotyping arrays are capable of handling DNA targets that are ∼300 Mb of sequence complexity (22). Thus, even if the primers contribute to non-specific amplification products, the complexity should not reach a level that would affect array hybridization.

Owing to the constraints of primer design coupled with the use of a particular restriction enzyme, it is conceivable that any given set of SNPs will not be fully accessible via MARA. However, when assessing access to the chromosome 21 SNPs with Sau3AI, a large number of SNPs were able to pass primer design. For example, <12% of the total SNPs arrayed were not present on Sau3AI restriction fragments that met the criteria required for primer design. Of the SNPs that remained, at least 75% had a minimum of one primer that was able to be designed when taking into account that the maximum length of the MARA product should remain below 750 bp. Access to the SNP set may also be improved by increasing the length of the MARA products or by using a combination of restriction enzymes for the initial genomic DNA digestion. For example, there is ∼5% increase in the total number of accessible SNPs if the length of the products is increased from 750 to 1000 bp. Improvements to the biochemistry in terms of cycling parameters or the choice of DNA polymerase could conceivably improve the length of the products. Taken together, these results suggest that the primer design requirements in conjunction with restriction enzyme choices for genomic DNA digestion are not limiting components of MARA, and thus access to most SNPs can be accommodated through careful consideration of these parameters.

When the total MARA chr 21 genotype calls were filtered into subsets based on call rate, the concordancy of the calls increased to over 99%. Among these calls, the primary type of discordance was a known heterozygous call that was called as a homozygote by MARA. This type of genotyping error is less costly in association studies than the misclassification of a more common homozygote as a less common homozygote (38), which occurred at a very low frequency with MARA. When the length of the extension products containing heterozygous SNPs is analyzed, there is a greater proportion of discordant calls in the larger size range (600 to 800 bp) as compared with concordant calls. This result may indicate that when the extension product becomes long, the concentration of full-length primary extension products may decrease due to the decreased amplification efficiency, resulting in a higher likelihood that there will be an imbalanced representation of the two alleles during the primary reaction. This imbalance could be preserved during the secondary amplification, and thus contribute to the reduced ability to detect some heterozygotes.

In conclusion, multiplex levels for SNP genotyping that are higher than typically achieved through standard multiplex PCR have been demonstrated using MARA in conjunction with allele-specific hybridization on high-density DNA arrays. In reactions >4000 primer-plex targeting SNPs from human chromosome 21, over 75% of the input primers were producing target sequences that led to SNP call rates of over 95% and concordances of over 99% using multiple DNA samples. Since the efficiency of the primers in MARA did not decrease as the level of multiplexing increased from 1000- to greater than 4000-plex, it is conceivable that MARA could function at the level of 10 000-plex, and when coupled with high-density arrays could enable locus-specific SNP genotyping for a number of applications. These include such diverse applications as whole genome scans using htSNPs, gene-based SNPs, or pathway specific SNPs as well as fine mapping of previously identified regions of linkage or association using chromosome-specific or investigator-defined SNP panels. Thus, the development of molecular methods, such as MARA for highly multiplexed locus-specific target DNA preparation, has a number of possible cost-effective applications to harness the genetic power of SNPs.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Jennifer Tom and Julia Yeh for technical assistance, Jing Huang, Hajime Matsuzaki and Gangwu Mei for bioinformatic analysis, and Kyle Cole and Dione Kampa for helpful suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Botstein D., White,R.L., Skolnick,M. and Davis,R.W. (1980) Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 32, 314–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venter J.C., Adams,M.D., Myers,E.W., Li,P.W., Mural,R.J., Sutton,G.G., Smith,H.O., Yandell,M., Evans,C.A., Holt,R.A. et al. (2001) The sequence of the human genome. Science, 291, 1304–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lander E.S., Linton,L.M., Birren,B., Nusbaum,C., Zody,M.C., Baldwin,J., Devon,K., Dewar,K., Doyle,M., FitzHugh,W. et al. (2001) Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature, 409, 860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibbs R.A., Belmont,J.W., Hardenbol,P., Willis,T.D., Yu,F., Yang,H., Ch'ang,L.-Y., Huang,W., Liu,B., Shen,Y. et al. (2003) The International HapMap Project. Nature, 426, 789–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Syvanen A.C. (2001) Accessing genetic variation: genotyping single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nature Rev. Genet., 2, 930–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwok P.Y. (2001) Methods for genotyping single nucleotide polymorphisms. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet., 2, 235–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwok P.Y. and Chen,X. (2003) Detection of single nucleotide polymorphisms. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol., 5, 43–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards M.C. and Gibbs,R.A. (1994) Multiplex PCR: advantages, development, and applications. PCR Methods Appl., 3, S65–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henegariu O., Heerema,N.A., Dlouhy,S.R., Vance,G.H. and Vogt,P.H. (1997) Multiplex PCR: critical parameters and step-by-step protocol. BioTechniques, 23, 504–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brownie J., Shawcross,S., Theaker,J., Whitcombe,D., Ferrie,R., Newton,C. and Little,S. (1997) The elimination of primer-dimer accumulation in PCR. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3235–3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shuber A.P., Grondin,V.J. and Klinger,K.W. (1995) A simplified procedure for developing multiplex PCRs. Genome Res., 5, 488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broude N.E., Driscoll,K. and Cantor,C.R. (2001) High-level multiplex DNA amplification. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev., 11, 327–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broude N.E., Zhang,L., Woodward,K., Englert,D. and Cantor,C.R. (2001) Multiplex allele-specific target amplification based on PCR suppression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 206–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapero M.H., Leuther,K.K., Nguyen,A., Scott,M. and Jones,K.W. (2001) SNP genotyping by multiplexed solid-phase amplification and fluorescent minisequencing. Genome Res., 11, 1926–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardenbol P., Baner,J., Jain,M., Nilsson,M., Namsaraev,E.A., Karlin-Neumann,G.A., Fakhrai-Rad,H., Ronaghi,M., Willis,T.D., Landegren,U. et al. (2003) Multiplexed genotyping with sequence-tagged molecular inversion probes. Nat. Biotechnol., 21, 673–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao K.V., Stevens,P.W., Hall,J.G., Lyamichev,V., Neri,B.P. and Kelso,D.M. (2003) Genotyping single nucleotide polymorphisms directly from genomic DNA by invasive cleavage reaction on microspheres. Nucleic Acids Res., 31, e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardon L.R. and Abecasis,G.R. (2003) Using haplotype blocks to map human complex trait loci. Trends Genet., 19, 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabriel S.B., Schaffner,S.F., Nguyen,H., Moore,J.M., Roy,J., Blumenstiel,B., Higgins,J., DeFelice,M., Lochner,A., Faggart,M. et al. (2002) The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science, 296, 2225–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang D.G., Fan,J.B., Siao,C.J., Berno,A., Young,P., Sapolsky,R., Ghandour,G., Perkins,N., Winchester,E., Spencer,J. et al. (1998) Large-scale identification, mapping, and genotyping of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the human genome. Science, 280, 1077–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong S., Wang,E., Hsie,L., Cao,Y., Chen,X. and Gingeras,T.R. (2001) Flexible use of high-density oligonucleotide arrays for single-nucleotide polymorphism discovery and validation. Genome Res., 11, 1418–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy G.C., Matsuzaki,H., Dong,S., Liu,W.M., Huang,J., Liu,G., Su,X., Cao,M., Chen,W., Zhang,J. et al. (2003) Large-scale genotyping of complex DNA. Nat. Biotechnol., 21, 1233–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuzaki H., Dong,S., Loi,H., Di,X., Liu,G., Hubbell,E., Law,J., Berntsen,T., Chadha,M., Hui,H. et al. (2004) Genotyping over 100 000 SNPs on a pair of oligonucleotide arrays. Nature Methods, 1, 109–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuzaki H., Loi,H., Dong,S., Tsai,Y.-Y., Fang,J., Law,J., Di,X., Liu,W.-M., Yang,G., Liu,G. et al. (2004) Parallel genotyping of over 10 000 SNPs using a one-primer assay on a high density oligonucleotide array. Genome Res., 14, 414–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fodor S.P., Read,J.L., Pirrung,M.C., Stryer,L., Lu,A.T. and Solas,D. (1991) Light-directed, spatially addressable parallel chemical synthesis. Science, 251, 767–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pease A.C., Solas,D., Sullivan,E.J., Cronin,M.T., Holmes,C.P. and Fodor,S.P. (1994) Light-generated oligonucleotide arrays for rapid DNA sequence analysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 5022–5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fodor S.P., Rava,R.P., Huang,X.C., Pease,A.C., Holmes,C.P. and Adams,C.L. (1993) Multiplexed biochemical assays with biological chips. Nature, 364, 555–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rozen S. and Skaletsky,H. (2000) Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol., 132, 365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collins F.S., Brooks,L.D. and Chakravarti,A. (1998) A DNA polymorphism discovery resource for research on human genetic variation. Genome Res., 8, 1229–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henke W., Herdel,K., Jung,K., Schnorr,D. and Loening,S.A. (1997) Betaine improves the PCR amplification of GC-rich DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3957–3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baskaran N., Kandpal,R.P., Bhargava,A.K., Glynn,M.W., Bale,A. and Weissman,S.M. (1996) Uniform amplification of a mixture of deoxyribonucleic acids with varying GC content. Genome Res., 6, 633–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu W.M., Di,X., Yang,G., Matsuzaki,H., Huang,J., Mei,R., Ryder,T.B., Webster,T.A., Dong,S., Liu,G. et al. (2003) Algorithms for large-scale genotyping microarrays. Bioinformatics, 19, 2397–2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patil N., Berno,A.J., Hinds,D.A., Barrett,W.A., Doshi,J.M., Hacker,C.R., Kautzer,C.R., Lee,D.H., Marjoribanks,C., McDonough,D.P. et al. (2001) Blocks of limited haplotype diversity revealed by high-resolution scanning of human chromosome 21. Science, 294, 1719–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landegren U. and Nilsson,M. (1997) Locked on target: strategies for future gene diagnostics. Ann. Med., 29, 585–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baner J., Isaksson,A., Waldenstrom,E., Jarvius,J., Landegren,U. and Nilsson,M. (2003) Parallel gene analysis with allele-specific padlock probes and tag microarrays. Nucleic Acids Res., 31, e103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan J.B., Chen,X., Halushka,M.K., Berno,A., Huang,X., Ryder,T., Lipshutz,R.J., Lockhart,D.J. and Chakravarti,A. (2000) Parallel genotyping of human SNPs using generic high-density oligonucleotide tag arrays. Genome Res., 10, 853–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hecker K.H. and Roux,K.H. (1996) High and low annealing temperatures increase both specificity and yield in touchdown and stepdown PCR. BioTechniques, 20, 478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Don R.H., Cox,P.T., Wainwright,B.J., Baker,K. and Mattick,J.S. (1991) ‘Touchdown’ PCR to circumvent spurious priming during gene amplification. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang S.J., Gordon,D. and Finch,S.J. (2004) What SNP genotyping errors are most costly for genetic association studies? Genet. Epidemiol., 26, 132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]