Abstract

Radiation therapy for head and neck cancers leads to permanent xerostomia due to the loss of secretory acinar cells in the salivary glands. Regenerative treatments utilizing primary submandibular gland (SMG) cells show modest improvements in salivary secretory function, but there is limited evidence of salivary gland regeneration. We have recently shown that poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels can support the survival and proliferation of SMG cells as multicellular spheres in vitro. To further develop this approach for cell-based salivary gland regeneration, we have investigated how different modes of PEG hydrogel degradation affect the proliferation, cell-specific gene expression, and epithelial morphology within encapsulated salivary gland spheres. Comparison of non-degradable, hydrolytically-degradable, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-degradable, and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels showed that hydrogel degradation by any mechanism is required for significant proliferation of encapsulated cells. The expression of acinar phenotypic markers Aqp5 and Nkcc1 was increased in hydrogels that are MMP-degradable compared with other hydrogel compositions. However, expression of secretory acinar proteins Mist1 and Pip was not maintained to the same extent as phenotypic markers, suggesting changes in cell function upon encapsulation. Nevertheless, MMP- and mixed mode-degradability promoted organization of polarized cell types forming tight junctions and expression of the basement membrane proteins laminin and collagen IV within encapsulated SMG spheres. This work demonstrates that cellularly remodeled hydrogels can promote proliferation and gland-like organization by encapsulated salivary gland cells as well as maintenance of acinar cell characteristics required for regenerative approaches. Investigation is required to identify approaches to further enhance acinar secretory properties.

Keywords: Salivary gland, Hydrogel, Poly(ethylene glycol), Acinar cells, Degradation

1. Introduction

Saliva is produced by secretory acinar cells, which are the predominant cell type within salivary glands. The acinar cells are arranged in clusters surrounded by myoepithelial cells and drain saliva into a ductal tree leading to the oral cavity. Unidirectional movement of saliva requires proper apical and basolateral polarization of acinar and ductal cells within the gland.

For individuals with head and neck cancers, which are diagnosed in over 50,000 people in the U.S. annually, radiation therapy often causes extensive acinar cell loss. Subsequently, chronic dry mouth syndrome (i.e., “xerostomia”) severely undermines oral health and function [1,2]. Though some radioprotective strategies are under development [3–8], current treatments for this major quality of life issue are only palliative [9]. Therefore, regenerative and/or radioprotective approaches for the salivary gland are critically needed.

Direct injection of primary mouse submandibular gland (SMG) cells into irradiated glands has been shown to partially restore gland function [10–12]. However, there is little evidence of acinar cell regeneration and the healing response is variable, likely due to poor cell localization and persistence in the gland. Regeneration strategies are further complicated by loss of the acinar cell phenotype in vitro [13–15].

Hydrogels have been used for localized cell delivery in numerous tissue engineering strategies [16–22]. Hydrogels provide highly controllable platforms to study the mechanistic effects of extracellular matrix (ECM) and soluble factors on encapsulated cell populations. Furthermore, hydrogels can be used to control cell localization and persistence simply through modulation of hydrogel degradation [18]. SMG cells have been cultured in several types of hydrogels derived from natural (e.g., Matrigel, fibrin, hyaluronic acid, and laminin) and synthetic (e.g., poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)) materials [23–30]. Although natural materials support the viability, proliferation, and some SMG phenotypic characteristics such as apicobasal polarization, these hydrogels have limited chemical versatility and imbibe underlying biological cues [31], which could lead to undesirable side effects on cell phenotype and function. Matrigel suffers from significant batch-to-batch variability and potential tumorigenicity, limiting its use for cell transplantation [32,33]. In contrast, biologically inert and synthetically flexible PEG-based hydrogels provide control over the presentation of bioactive factors (e.g., adhesive ligands) and chemical and physical characteristics (e.g., degradability) of hydrogels [34–40].

We previously identified PEG hydrogels as a promising platform for primary salivary gland cell culture [28]. Specifically, we found that allowing SMG cell sphere formation prior to encapsulation and using thiol-ene versus chain-polymerized crosslinking promoted cell survival and proliferation for up to 14 days in vitro. Here, we have examined how different modes of PEG hydrogel degradation affect the proliferation, organization, and phenotype of encapsulated SMG cells.

2. Methods

2.1. PEG macromer synthesis

2.1.1. Materials

Dithiol-functionalized PEG (PEGDT, 3.4 kDa) was purchased from Laysan Bio, and 4-arm hydroxyl-functionalized PEG (PEG-OH, 20 kDa) was purchased from JenKem Technologies, USA. All other materials were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless specified otherwise. Synthesis of lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl phosphinate (LAP) was performed as described previously [41].

2.1.2. 4-arm PEG-NH2 synthesis

4-arm 20 kDa PEG-NH2 was synthesized from a 4-arm 20 kDa PEG with hydroxyl end groups on each arm (PEG-OH) using end group substitution via a mesylate intermediate. 10 g of 4-arm 20 kDa PEG-OH was dissolved in 200 mL toluene and the solution was evaporated to ∼100 mL by azeotropic distillation. The solution was cooled to room temperature, 50 mL of dichloromethane (DCM) was added, and the solution was placed on ice for 15 min with constant stirring. 4 M equivalents (meq) per OH of triethylamine (TEA) were added, followed by 4 meq per OH of methanesulfonyl chloride added dropwise. The solution was purged with N2 gas, allowed to react on ice overnight, vacuum filtered to remove salt precipitates, and concentrated to 20–30 mL using a Rotorvapor® RII rotovap (Buchi) at 60 °C. Concentrated 4-arm PEG-mesylate was precipitated in 10× volume of ice-cold diethyl ether, collected via filtration, and dried overnight under vacuum. Amine functionalization of mesylate-functionalized 4-arm PEG was performed by dissolving the entire PEG-mesylate product in 300 mL of 30% NH4OH, stirring for 3 days, and evaporating via exposure to atmosphere until the volume was reduced to ∼100 mL (over ∼4 days). The solution was raised to pH 13 using 1 M NaOH and 100 mL of DCM was added. After overnight separation, the aqueous fraction was extracted twice more and collected DCM was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. After filtration and concentration to 20-30 mL, the PEG product was precipitated in ∼300 mL of ice-cold diethyl ether and collected via filtration. Confirmation of both mesylate and amine functionalization was determined by 1H-NMR (>90% functionalization) performed on a Bruker Avance™ 400 MHz spectrometer: 4-arm PEG-mesylate (1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 4.2 ppm (ether protons adjacent to mesylate group, 8H, singlet), 3.5-3.9 ppm (PEG ether protons, 1817H, multiplet)); 4-arm PEG-NH2 (1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 3.0 ppm (ether protons adjacent to amine group, 8H, singlet), 3.5-3.9 ppm (PEG ether protons, 1817H, multiplet)).

2.1.3. 4-Arm PEG-Norbornene synthesis

4-arm 20 kDa PEG-OH and 4-arm 20 kDa PEG-NH2 were functionalized with norbornene (forming PEG-ester-norbornene or PEG-amide-norbornene) using N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) coupling as previously described [28,42]. Norbornene carboxylate (10 meq per PEG arm), DCC (5 meq), pyridine (1 meq), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) (0.5 meq) were dissolved in 100 mL DCM for ∼30 min at room temperature, and 5 g of 4-arm PEG dissolved in ∼50 mL DCM was added dropwise. The solution was stirred at room temperature overnight and vacuum filtered. The filtrate was precipitated in 1 L ice-cold diethyl ether. The precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration, twice dissolved in 75 mL DCM, and precipitated in ice-cold diethyl ether. Structure and percent functionalization (>90%) were determined by 1H-NMR: 4-arm PEG-ester-norbornene and 4-arm PEG-amine-norbornene (1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 6.0-6.3 ppm (norbornene vinyl protons, 8H, multiplet), 3.5-3.9 ppm (PEG ether protons, 1817H, multiplet)).

The final product was dialyzed against distilled, deionized water (ddH2O) for 24 h using 1000 g/mol molecular weight cut off (MWCO) dialysis tubing (Spectrum Labs) and lyophilized.

2.2. Peptide synthesis

The peptide GKKCGPQGIWGQCKKG (MMP-degradable peptide, Fig. 1) was synthesized by standard solid phase peptide synthesis on FMOC-Gly-Wang resin (EMD) using a Liberty 1 Microwave-Assisted Peptide Synthesizer (CEM) with UV monitoring as described previously ([28,43], Supplemental Methods). The central sequence of this peptide, GPQGIWGQ, has been shown to be degradable by multiple MMPs [44,45]. On-resin peptides (0.5 mmol) were deprotected and cleaved by the addition of a cleavage cocktail composed of 18.5 mL trifluoroacetic acid (Acros Organics), 0.5 mL triisopropylsilane, 0.5 mL ddH2O, and 0.5 mL 3,6 dioxa-1,8-octane dithiol (DODT) for 2 h. Cleaved peptide was collected as a filtrate via vacuum filtration and purified by precipitation in ice-cold diethyl ether (∼180 mL). The peptide was collected by centrifugation and washed twice in ice-cold diethyl ether. The peptide product was dried under vacuum overnight, dialyzed using 500 MWCO dialysis tubing (Spectrum Labs) for 48 h against ddH2O, and lyophilized. Peptide molecular weight was verified using a Bruker autoflex™ III smartbeam Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time of Flight (MALDI-ToF) mass spectrometer (Supplemental Methods). Peptide purity via this method is typically >90% as measured by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC, Shimadzu Prominence, Kromasil Eternity™ C18 column (4.6 × 50 mm) running a gradient from 5 to 95% acetonitrile in water (both containing 1% TFA)) [43,45,46]. After dissolving in ddH2O, actual peptide concentration was determined via absorbance at 205 nm measured on an Evolution™ UV-Vis detector (Thermo Scientific) to ensure accurate peptide crosslinker concentration for hydrogel synthesis [43,45–47]. Thiol functionalization of 85% was determined using Ellman's reagent (Alexis Biochemical) and a cysteine standard curve (Alfa Aesar) dissolved in Dulbecco's phosphate buffer saline (DPBS, Gibco) by measuring absorbance at 405 nm with a Tecan Infinite® M200 plate reader.

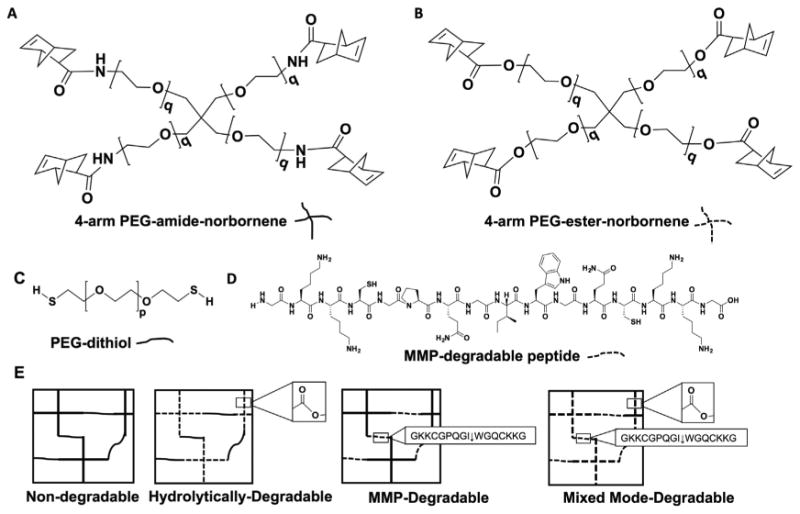

Fig. 1.

Macromer chemistry dictates the mode of degradation of PEG hydrogels. The composition of the four types of hydrogels used for SMG sphere encapsulations: non-degradable, hydrolytically-degradable, MMP-degradable, and mixed mode-degradable. 4-arm PEG norbornene q = 113 containing either a non-degradable amide (A) or hydrolytically-degradable ester (B). Dithiol crosslinkers used were either PEG-dithiol (p = 73, C) or the MMP-degradable peptide (D). (E) Exposure to ∼5 mW/cm2 365 nm light and the photoinitiator lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) results in thiol-ene mediated polymerization of hydrogel macromers in ∼3 min.

2.3. Assessing hydrogel degradation mechanism and rate

Non-degradable, hydrolytically-degradable, MMP-degradable, and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels were formed as depicted in Fig. 1. Briefly, solutions of 2 mM norbornene-functionalized 4-arm PEG macromer (PEG-ester-norbornene or PEG-amide-norbornene), 4 mM dithiol crosslinkers (PEGDT or MMP-degradable peptide), and 0.028 wt% of the photoinitiator LAP were prepared. The macromer solutions were pipetted into 1 mL syringes with the tips cut off (30 μL/syringe) and photopolymerized (∼5 mW/cm2, 365 nm, 3 min). Polymerized hydrogels were incubated in 1 mL DPBS at 37 °C for 24 h before adding 1 μg/mL Collagenase Type II (Gibco). This concentration was identified via the literature [44,48,49] and preliminary dose-dependent degradation experiments. Compression testing was performed on hydrogels as a measure of temporal degradation. Specifically, using a Q-Test/5 material test frame with a 5 N load cell (MTS), Young's modulus values were computed from resistant force measurements after compressing hydrogels to 95% of their uncompressed heights. Every 48 h, enzyme was replaced (to account for enzyme inactivation) and compression testing was performed.

2.4. SMG cell isolation and sphere formation

All procedures using mice were approved by the University of Rochester Committee for Animal Resources. Primary mouse SMG cells were isolated as described [28,50]. Female C57BL/6 mice ages 8-24 weeks were euthanized and SMGs were removed, mechanically disrupted, suspended in 5 mL of dissociation solution (Hank's Balanced Salt Solution without CaCl2 and MgCl2 (Gibco), 1 mg/mL Collagenase Type II (Gibco), and 5 μg/mL hyaluronidase (Appli-Chem)), and incubated at 37 °C for 40 min with gentle shaking. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation (400 RCF for 3 min), washed in 5 mL DPBS, re-pelleted (400 RCF for 3 min), and re-suspended in 0.05% Trypsin (Gibco) for 4 min at room temperature. Cells were mechanically disrupted by gentle pipetting, passed through a 40 μm mesh filter, pelleted with centrifugation (1400 RCF for 3 min), and re-suspended in 5 mL complete media (DMEM:F12 (1:1, Gibco)) with GlutaMAX™ (1×, Gibco), Antibiotic-Antimycotic solution (100 I.U./mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B, Gibco), N-2 supplement (1×, Invitrogen), 10 μg/mL insulin (Life Technologies), 1 μM dexamethasone, 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF, Life Technologies), and 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, Life Technologies). Cells were cultured at a density of ∼1.2 × 106cells/mL in non-tissue culture treated Petri dishes (5 mL total) and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 48 h to allow sphere formation.

2.5. SMG cell sphere encapsulation

SMG cell spheres were encapsulated within thiol-ene photopolymerized PEG hydrogels as described in Section 2.3. Additionally, laminin was incorporated into the macromer solutions at 0.1 mg/mL due to previous studies highlighting the efficacy of laminin in both salivary gland regeneration and tissue engineering approaches [27,28,51–53]. Briefly, SMG sphere cell number was determined using a hemocytometer. The number of cells per sphere (usually 2-15 cells per sphere) was approximated based upon the size of the sphere compared to the size of individual cells. SMG cell spheres were re-suspended in macromer solutions at ∼5 × 106cells/mL and pipetted into 1 mL syringes with the tips cut off (30 μL/syringe). Due to fast sedimentation of the spheres, each hydrogel was photopolymerized immediately (∼5 mW/cm2, 365 nm, 3 min). Polymerized hydrogels were placed in 1 mL of media in 24-well plates, which was exchanged every 2 days.

2.6. ATP analysis

At specified time points, hydrogels were incubated in 500 μL of 50% CellTiter-Glo® Reagent/50% DPBS for 45 min, and total hydrogel ATP levels were measured using the CellTiter-Glo® reagent (Promega), as described, to quantify the number of encapsulated cells [28]. Samples were stored at −80 °C. Upon analysis, samples were thawed and then added to 96-well plates (100 μL/well, 3 samples/hydrogel). Sample luminescence was measured on a Synergy™ Mx (BioTek) luminescence plate reader and compared to an ATP standard curve (EMD Millipore).

2.7. RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and qPCR

Suspension-cultured cells were pelleted (400 RCF for 3 min), re-suspended in 350 μL TRK Lysis Buffer (Omega Bio-tek) + β-mercaptoethanol (p-ME, 20 μL per 1 mL lysis buffer), and stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction. Hydrogel samples were snap frozen and stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction. Hydrogels were thawed, disrupted in 300 μL TRK Lysis Buffer + β-ME using a plastic pestle, and homogenized with a Tissue-Tearor™ (Biospec) for 60 s. 585 μL of nuclease-free water was added, and samples were further homogenized for 30 s before addition of 15 μL of 20 mg/mL Biotechnology Grade Proteinase K (VWR). Samples were incubated for 10 min at 55 °C and then centrifuged at 10,000 RCF for 2 min. RNA was precipitated in ethanol and RNA purification was performed on an E.Z.N.A.® purification column.

RNA concentration and quality was determined using a Nano-Vue™ UV-Vis spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare). Samples were reverse transcribed using the iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad). qPCR was performed on a CFX96™ Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) at an annealing temperature of 60 °C using SsoFast™ EvaGreen Super-mix (BioRad) with 500 nM of forward and reverse primers (Supplemental Table 1) and 2 ng of cDNA per sample. Each sample was run in triplicate for each gene with the exceptions of samples for Mmp2 and Mmp14, which were run in duplicate due to limiting amounts of sample cDNA. Gene expression was deemed undetectable if multiple tested samples were above the maximum threshold cycle value (CT = 40) and the average threshold cycle value was greater than 37 (average CT > 37). Gene expression was analyzed using the Pfaffl method with Rpl32 (LE32) as the housekeeping gene [54].

2.8. Fixation, embedding, and immunofluorescence of hydrogels and submandibular glands

2.8.1. Hydrogel Fixation, embedding, and sectioning

Hydrogels were incubated in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 45 min at room temperature with shaking. After PFA treatment, hydrogels were washed 3× with 1 mL DPBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C in 1 mL of 1% poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA, MW: 146,000-168,000) to improve hydrogel cryosectioning [55]. Hydrogels were embedded in optimal cutting temperature solution (OCT, Tissue-Tek) and frozen in liquid N2. 10 μm sections were cut using a HM 550 (Micron) cryostat and mounted on PermaFrost™ slides (Chase Scientific). Generally, sections were cut 250-900 μm inside the hydrogel.

2.8.2. Submandibular gland fixation, embedding, and sectioning

SMGs were surgically removed and fixed overnight in 5 mL of 4% PFA. Whole glands were incubated in a sucrose gradient (30 min in 5%, 10%, and 15% sucrose) and incubated in 50:50 30% sucrose:OCT solution overnight. Samples were embedded in OCT, frozen with liquid N2, and sectioned as described above.

2.8.3. Immunofluorescence

Antigen retrieval via incubation for 10 min in HIER buffer (10 mM Tris base, 1 mM EDTA solution, 0.05% pH 9.0) was used for sections stained with primary antibodies for all tested proteins except keratin 5 (Krt5) (listed in Supplemental Table 2). Sections were first washed 3× in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min and blocked in 5 vol% normal donkey serum, 1 wt% Bovine Serum Albumin, and 0.1 vol% Triton™ X-100 for 1 h at room temperature then washed in PBS for 5 min. Primary antibodies were diluted in 1 wt% BSA and incubated on sections at 4 °C overnight. 1 wt% BSA solution served as a negative control. Sections were washed 3 × in PBS for 5 min and then incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies (Supplemental Table 2) in 1 wt% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. After 3 washes in PBS for 5 min, sections were stained with DAPI (1:500, Themo Scientific), rinsed, and mounted with Immu-Mount™ mounting solution (Shandon).

For double immunostaining, antigen retrieval, blocking, and staining for Nkcc1 was performed as described above (Supplemental Table 2). After overnight incubation, slides were stained with the secondary antibody (Supplemental Table 2), washed 3× in PBS, and then stained overnight with the additional primary antibodies (for ZO-1 or Krt5). Additional secondary antibody staining, DAPI staining, and mounting were performed as described above.

All samples were imaged using a FluoView™ FV1000 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope (Olympus). Single slices or 15 μm z-stacks with 2.5 μm spacing between slices were taken with either a 40 × or 100× oil immersion objective lens. Within each section, the middle of cell spheres was imaged. For each stain and sample, at least three spheres were imaged per section and at least three sections were analyzed per slide. Negative controls with only secondary antibodies were imaged to ensure no non-specific staining was detected. ImageJ was used to analyze stained SMG sphere diameters in the various hydrogel chemistries at day 14. Area values were obtained using the ImageJ polygon selection tool to outline sphere edges (sample sizes were 7-27 per hydrogel composition for analyses).

2.9. Statistical analysis

Two-way ANOVA with Sidak post-hoc analyses for multiple comparisons were performed using Prism software (GraphPad) with p < 0.05 as the threshold for statistical significance unless otherwise indicated in legends. All data are represented as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Hydrogel degradation

The effect of hydrogel degradation mechanism on encapsulated SMG cell sphere phenotype and function was explored. Varying macromer compositions of thiol-ene hydrogels result in different mechanisms of degradation. Hydrogels formed using 4-arm PEG-ester-norbornene and PEG-dithiol, as used in previous work [20], are degraded via ester hydrolysis (Fig. 1). Hydrogels can be rendered non-degradable when macromers are formed from amine-functionalized PEG, which results in a highly stable amide-norbornene (i.e., PEG-amide-norbornene) in place of the ester-norbornene (Fig. 1). MMP-degradable hydrogels are formed using PEG-amide-norbornene crosslinked via dithiol (cysteine) peptides that can be cleaved by cell-secreted matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (Fig. 1). Finally, hydrolytically- and enzymatically- or mixed mode-degradable hydrogels utilize PEG-ester-norbornene crosslinked by MMP-degradable peptides (Fig. 1).

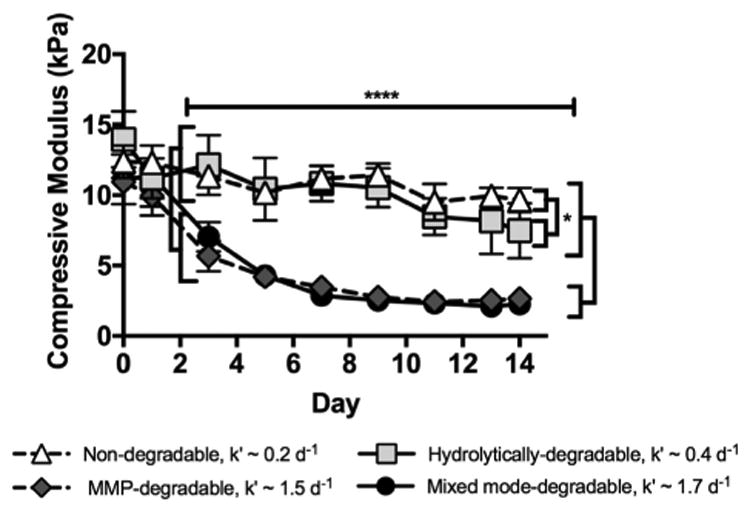

To characterize the mode of degradation expected based on underlying chemical composition and in the presence of cells, Young's modulus was measured over time using compression testing as a surrogate for hydrogel degradation. The compressive modulus of degradable hydrogels is known to decrease as crosslinks are cleaved [56]. Hydrogel degradation was performed in the presence of 1 μg/mL collagenase, which is a heterogeneous mixture of proteases capable of cleaving the MMP-degradable peptide crosslinker used here. After 48 h of collagenase degradation, modulus values of MMP-degradable and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels are lower than those of non-degradable and hydrolytically-degradable hydrogels. This result demonstrates that hydrogel degradation is dependent on MMP-degradable peptide incorporation. When comparing MMP-degradable and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels, compressive modulus values did not differ over 14 days. However, when comparing the rate constants of degradation, there is an increase for hydrogels with mixed mode- compared to MMP-degradability (k′mixed∼1.7 d−1 versus k′mmp∼1.5 d−1). For non-degradable and hydrolytically-degradable hydrogels, compressive modulus difference at day 14 was observed (Fig. 2), with a greater rate of degradation for the hydrolytically-degradable hydrogels (k′hydro ∼0.4 d−1 versus k′nondeg ∼0.2 d−1). These findings suggest that the ester bond hydrolysis of PEG-ester-norbornene is more subtle, indicating that differences in compressive modulus may be detected when comparing MMP-degradable and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels at time points beyond two weeks.

Fig. 2.

MMP-degradable and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels degrade upon treatment with collagenase (k′ = 1.5 and 1.7 d−1) while non-degradable and hydrolytically-degradable hydrogels exhibit modest degradation over the same time course (k′ = 0.2 and 0.4 d−1), as expected based on hydrogel composition. Degradation was measured over time using unconfined compression with 1 μg/mL collagenase treatment. N = 3–5; error bars denote ± standard deviation; * = p < 0.05, **** = p < 0.0001 when comparing hydrogels specified by brackets. Significant differences between hydrolytically-degradable hydrogels and MMP-degradable and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels at day 0 (p < 0.01) and between non-degradable hydrogels and MMP-degradable hydrogels at day 1 (p < 0.05), which are likely due to slight variability in hydrogel formulations, are not denoted due to space constraints.

3.2. Encapsulated SMG cell sphere proliferation, MMP expression, acinar cell maintenance, epithelial polarization, and size

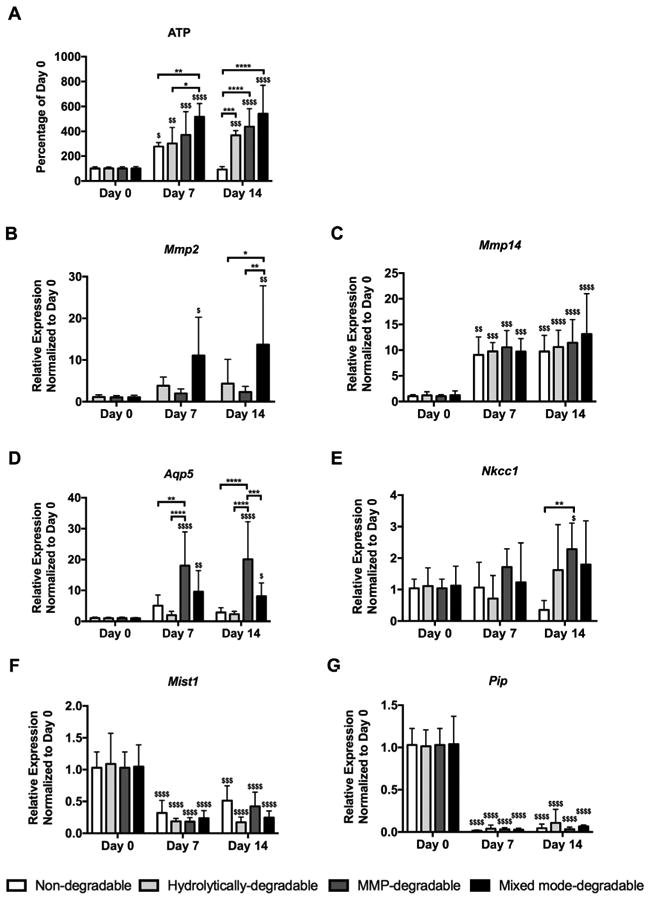

To investigate how hydrogel degradation mechanism affects the ability of SMG cells to proliferate as they degrade their microenvironment, ATP production and MMP gene expression were measured. Relative to other hydrogel types, non-degradable hydrogels showed decreased ATP, a surrogate measure for cell number, in encapsulated SMG cells at day 14 (Fig. 3A). Moreover, when compared to ATP levels of SMG cells at day 0 (i.e., spheres just prior to encapsulation), ATP levels at day 14 were increased in SMG cells encapsulated in hydrolytically-degradable, MMP-degradable, and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels (Fig. 3A). These results indicate that degradable hydrogels promote SMG cell proliferation.

Fig. 3.

MMP-degradable hydrogels promote SMG sphere proliferation and expression of acinar cell markers Aqp5 and Nkcc1 while secretory markers Pip and Mist1 are reduced. (A) ATP levels normalized to day 0 were used to measure proliferation of encapsulated SMG cells. Quantitative PCR was used to measure gene expression, relative to LE32 (housekeeping gene), of Mmp2 (B), Mmp14 (C), Aqp5 (D), Nkcc1 (E), Mist1 (F), and Pip (G) of SMG cell spheres at day 0 (pre-encapsulation) and days 7 and 14 (post-encapsulation). N = 5–10 per hydrogel type per time point; error bars denote ± standard deviation; compared to day 0, $ = p < 0.05, $$ = p < 0.01, $$$ = p < 0.001, $$$$ = p < 0.0001; comparing hydrogel types denoted by brackets, * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001, **** = p < 0.0001.

Quantitative PCR was performed to assess the temporal expression of Mmp2 and Mmp14 within hydrogels. These MMPs were chosen due to expression in adult [57-59] or embryonic [60] salivary gland tissue and activity towards the MMP-degradable peptide crosslinker used here or similar, collagen-derived peptide crosslinkers [44]. Furthermore, MMP14 activates pro-MMP2 to active MMP2 [60], providing impetus to investigate expression of the two enzymes in tandem. When compared to SMG cells at day 0, SMG cells encapsulated in mixed mode-degradable hydrogels exhibited >11-fold Mmp2 expression at days 7 and 14 (Fig. 3B). At day 14, Mmp2 expression was also increased by cells in mixed mode-degradable hydrogels compared to hydrolytically-degradable and MMP-degradable hydrogels (Fig. 3B). Conversely, Mmp2 expression was not detectable in non-degradable hydrogels at days 7 or 14, suggesting that degradation is necessary for maintaining Mmp2 expression by SMG cells. Mmp14 expression was increased (>9-fold) irrespective of hydrogel composition at days 7 and 14 (Fig. 3C).

Next, acinar cell maintenance in SMG spheres was assessed via gene expression of several acinar cell markers, including the water channel aquaporin-5 (Aqp5), the ion exchanger Na+-K+-2Cl− Nkcc1 (Slc12a2), the transcription factor Mist1 (Bhlha15), and the secretory glycoprotein prolactin-induced protein (Pip). When compared to SMG cells at day 0, SMG cells in MMP-degradable and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels showed increased (>7-fold) Aqp5 expression at days 7 and 14 (Fig. 3D). Aqp5 expression was also increased in MMP-degradable hydrogels relative to all other hydrogels at day 14 (Fig. 3D). Nkcc1 expression was increased in MMP-degradable hydrogels versus non-degradable hydrogels at day 14 (Fig. 3E). When compared to SMG cells at day 0, Nkcc1 expression was increased (∼2-fold) in MMP-degradable hydrogels and maintained in all other hydrogel types through 14 days (Fig. 3E). Unlike Aqp5 and Nkcc1, Mist1 (Fig. 3F) and Pip (Fig. 3G) expression were decreased in SMG cells within all hydrogel types at days 7 and 14. To ensure Mist1 downregulation was not due to polymerization conditions, expression was analyzed further. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 1A, there was no significant effect on Mist1 expression in SMG spheres 1 day after exposure to polymerization conditions. Furthermore, we observed a decrease in Mist1 expression by cells in suspension culture by day 14 (Supplemental Fig. 1B) similar to that seen in encapsulated cells. Thus, decreased expression of Mist1 and Pip, which are specifically markers of secretory acinar cells, suggests that Aqp5- and Nkcc1-expressing cells in SMG spheres in all hydrogels have limited functional capacity.

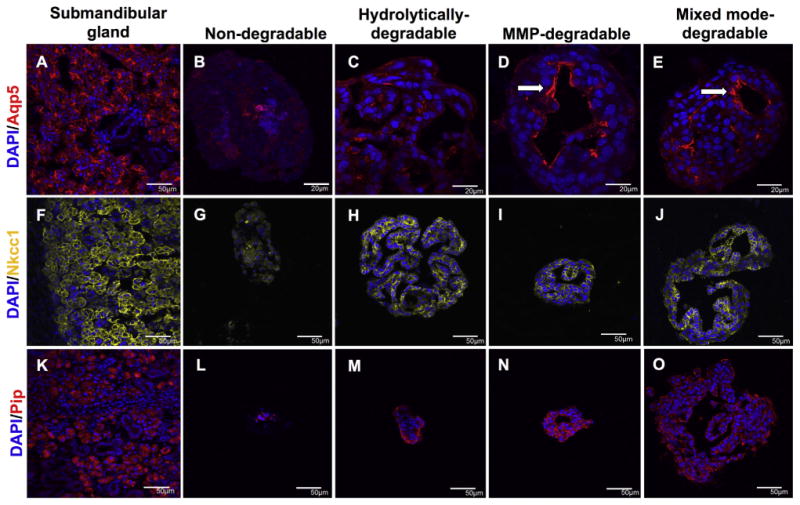

To evaluate morphological changes in encapsulated SMG cell spheres and spatial distribution of acinar cell markers, immunohistochemistry was performed. In hydrolytically-degradable hydrogels, encapsulated spheres initially appeared as uniform clusters of cells at day 0 and expanded and developed luminal spaces by day 14 (Supplemental Fig. 2). Lumens form by day 14 within degradable hydrogels only and the largest are found within MMP- and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels (Fig. 4 and Supplemental Fig. 3). In the salivary gland, Aqp5 is localized at the apical membrane of acinar cells (Fig. 4A). Aqp5 staining is weak and shows random spatial distribution in SMG cell spheres in hydrolytically-degradable hydrogels at day 14 (Fig. 4C). In contrast, Aqp5 fluorescence is intense and apically localized in MMP-degradable (Fig. 4D) and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels (Fig. 4E) at day 14. Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor 3 (IP3R3) is a regulator of intracellular Ca2+ signaling and, like Aqp5, localizes at the apical membrane of acinar cells (Supplemental Fig. 4A). IP3R3 staining, like that of Aqp5, is intense and apically concentrated in MMP-degradable (Supplemental Fig. 4C) and mixed mode-degradable (Supplemental Fig. 4D) hydrogels. In the salivary gland, Nkcc1 is localized at the basolateral membrane of acinar cells (Fig. 4F). Nkcc1 remains basolaterally localized in SMG cell spheres in all degradable hydrogels at day 14 (Fig. 4H-J). Interestingly, while there is some Pip staining in cells encapsulated in all hydrogel types at day 14 (Fig. 4L-O), it seems to be fairly nonspecific, especially when compared to control salivary glands (Fig. 4K). To summarize, the acinar cell markers Aqp5, IP3R3, and Nkcc1, but not Pip, demonstrated apicobasal polarization similar to the gland when encapsulated within MMP-degradable and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels.

Fig. 4.

MMP-degradability promotes the apicobasal localization of acinar cell markers in SMG cell spheres. Immunohistochemistry was used to analyze Aqp5 (red, A-E), Nkcc1 (yellow, F-J), and Pip (red, K-O) in submandibular glands (A,F,K) and SMG cell spheres encapsulated in non-degradable (B,G,L), hydrolytically-degradable (C,H,M), MMP-degradable (D,I,N), and mixed mode-degradable (E,J,O) hydrogels at day 14. Arrows indicate apical localization. DAPI counterstain was used to visualize nuclei (blue). Scale bars represent either 50 μm (A, F-O) or 20 μm (B-E). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

To further evaluate the effects of hydrogel chemistry on spheres, immunofluorescent images taken at day 14 were used to quantitate sphere diameters and extrapolate to areas, assuming spherical geometry. As shown in Table 1, hydrogel degradation had a large impact on sphere diameters and areas, with ∼1.5–2-fold increases in diameters and ∼3–5-fold increases in areas. Furthermore, significantly increased diameters and areas were found for mixed mode-degradable versus MMP-degradable hydrogels. Overall these data suggest the mechanism of degradation affects encapsulated SMG sphere size and area and this effect is likely due to increased proliferation.

Table 1.

Maximum diameter and mean area of SMG cell spheres in hydrogels with different degradation mechanisms at day 14.

| Hydrogel Type | Sample Size | Max Diameter (μm) | Area (μm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-degradable | 7 | 93 ± 27 | 3,512 ± 1,368 |

| Hydrolytically-degradable | 22 | 165 ±53* | 16,661 ± 10,713* |

| MMP-degradable | 15 | 135 ± 38* | 10,999 ± 4,897* |

| Mixed mode-degradable | 27 | 177 ±54*,# | 19,204 ± 10,542*,# |

N = 7-27; ± denotes standard deviation; a one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons testing was used for analysis,

= p < 0.05 versus non-degradable hydrogels,

= p < 0.05 versus MMP-degradable hydrogels.

3.3. SMG cell sphere duct/myoepithelial cell characterization

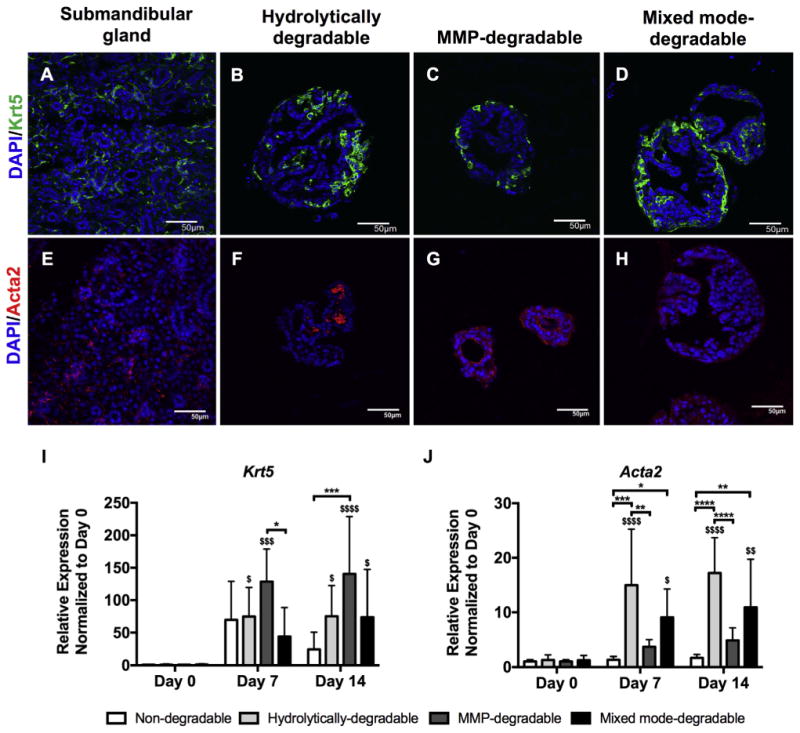

To better understand the non-acinar cell phenotypes in encapsulated SMG cell spheres, keratin-5 (Krt5, a duct and myoepthelial marker) and alpha smooth muscle actin (Acta2, myoepithelial marker) expression were evaluated by immunohistochemistry and quantitative PCR. Comparison between the two markers can distinguish between duct and myoepithelial cells. In contrast to the intense staining of Krt5 in cells at the periphery of SMG cell spheres (Fig. 5B-D), Acta2 staining was weak and disorganized (Fig. 5F-H) in degradable hydrogels at day 14. Further, in degradable hydrogels at day 14, there was substantially higher Krt5 gene expression relative to Acta2 versus day 0 controls (>73-fold versus <18-fold) (Fig. 5I, J). Taken together, immunohistochemistry and quantitative PCR results suggest that Krt5-positive cells are predominantly duct cells within encapsulated SMG cell populations.

Fig. 5.

Krt5-positive cells in degradable hydrogels are mainly ductal. Immunohistochemistry was used to analyze Krt5 (green, A-D) and Acta2 (red, E-H) in submandibular glands (A,E) and SMG cell spheres encapsulated in hydrolytically-degradable (B,F), MMP-degradable (C,G), and mixed mode-degradable (D,H) hydrogels at day 14. DAPI counterstain was used to visualize nuclei (blue). Scale bars represent 50 μm. Quantitative PCR was used to measure gene expression, relative to LE32 (housekeeping gene), of Krt5 (I) and Acta2 (J) in SMG cell spheres at day 0 (pre-encapsulation) and days 7 and 14 (post-encapsulation). N = 5–7 per hydrogel type per time point; error bars denote ± standard deviation; compared to day 0, $ = p < 0.05, $$ = p < 0.01, $$$ = p < 0.001, $$$$ = p < 0.0001; comparing hydrogel types denoted by brackets, * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001, **** = p < 0.0001. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

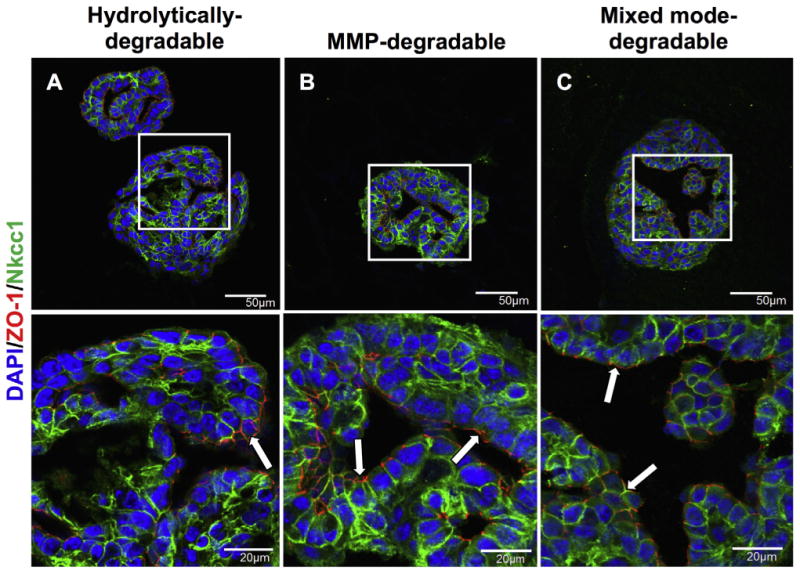

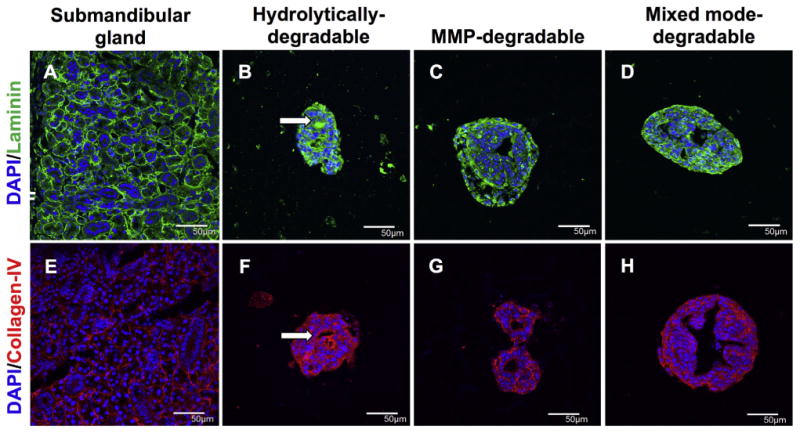

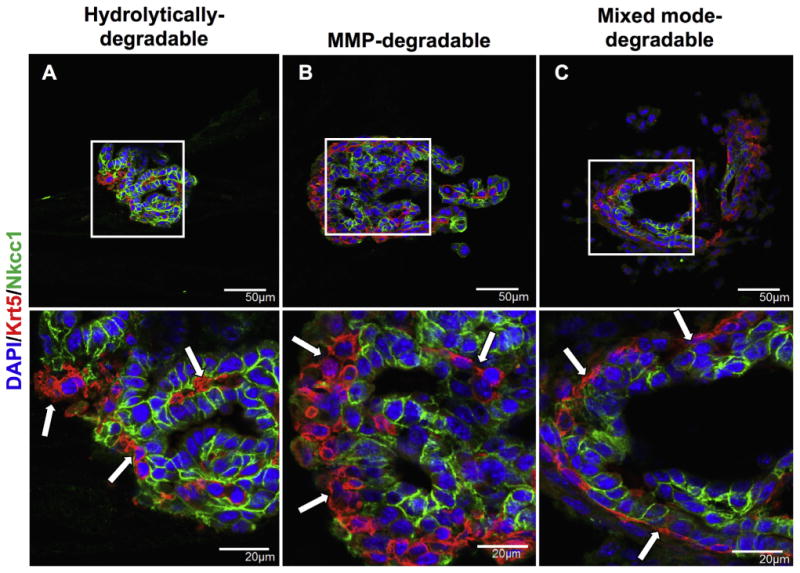

3.4. Assessing apicobasal organization of SMG spheres

To further assess epithelial polarization in encapsulated SMG cell spheres, the spatial distribution of tight junctions and basement membrane proteins were examined through immunohistochemistry. Tight junctions (TJs) act as intermembrane barriers, preventing lateral movement of apically and basolaterally localized membrane proteins as well as the leakage of ions [61]. ZO-1 is a component of the TJ protein complex and is localized in the apical region of acinar and duct cells (Supplemental Fig. 4E). ZO-1 was double stained with Nkcc1 to study tight junction formation and apicobasolateral polarity with respect to large, isolated lumens formed by day 14 in all degradable hydrogels (Fig. 6). MMP-degradable (Fig. 6B) and mixed mode-degradable (Fig. 6C) hydrogels demonstrate apically localized ZO-1 and basolaterally localized Nkcc1 surrounding lumens. In contrast, ZO-1 was seen at the outer periphery of SMG cell spheres and lumens appeared to stain randomly for ZO-1 or Nkcc1 in hydrolytically-degradable hydrogels (Fig. 6A). Like TJs, basement membrane proteins are important for promoting apicobasal polarity [62] but are basolaterally localized in the salivary gland (Fig. 7A, E). In SMG cell spheres, the basement membrane proteins laminin and collagen IV showed apical localization with respect to lumens of SMG cell spheres in hydrolytically-degradable hydrogels at day 14 (Fig. 7B, F). In contrast, basolateral localization of laminin and collagen IV was maintained in MMP-degradable (Fig. 7C, G) and mixed mode-degradable (Fig. 7D, H) hydrogels at day 14. Finally, at day 14 in MMP- and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels, Krt5-positive cells localized to the periphery of spheres, the site of the laminin and collagen IV basement membrane components, and Nkcc1-positive cells were juxtaposed to lumens (Fig. 8). We speculate that this may result from preferential localization of basal duct and possibly myoepithelial cells to sites near intact basement membrane. Collectively, these results indicate that hydrogel MMP-degradability promotes encapsulated SMG cell tight junction formation and apicobasal polarity with respect to ZO-1, Nkcc1, Krt5, and basement membrane proteins.

Fig. 6.

MMP-degradability promotes formation of tight junctions and apicobasal polarization. Immunohistochemistry was used to analyze co-stained ZO-1 (red) and Nkcc1 (green) in SMG cell spheres encapsulated in hydrolytically-degradable (A), MMP-degradable (B), and mixed mode-degradable (C) hydrogels at day 14. DAPI counterstain was used to visualize nuclei (blue) and arrows highlight areas of ZO-1 staining. Scale bars represent either 50 μm (top row) or 20 μm (bottom row). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 7.

MMP-degradability promotes basolateral localization of basement membrane proteins. Immunohistochemistry was used to analyze laminin (green, A-D) and collagen-IV (red, E-H) in submandibular glands (A,E) and SMG cell spheres encapsulated in hydrolytically-degradable (B,F), MMP-degradable, and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels (D,H) at day 14. Arrows indicate apical localization. DAPI counterstain was used to visualize nuclei (blue). Scale bars represent 50 μm. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 8.

MMP-degradability promotes the localization of Nkcc1-positive acinar cells at the lumen and Krt5-positive duct/myoepithelial cells at the periphery of SMG cell spheres. Immunohistochemistry was used to analyze co-stained Krt5 (red) and Nkcc1 (green) in hydrolytically-degradable (A), MMP-degradable (B), and mixed mode-degradable (C) hydrogels at day 14. DAPI counterstain was used to visualize nuclei (blue) and arrows are used to accentuate the organizational differences in Krt5 staining. Scale bars represent either 50 μm (top row) or 20 μm (bottom row). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

We have previously shown that mouse SMG cell spheres can be encapsulated within PEG hydrogels with excellent viability [28]. Here we have examined how hydrogel degradation mechanism affects encapsulated SMG cell phenotype and function. We report that hydrogel degradation increases cell proliferation and sphere size, and that the mechanism of hydrogel degradation profoundly affects the phenotype and organization of cells within encapsulated SMG spheres. Our data show that encapsulation of SMG cells within hydrogels cellularly remodeled through incorporation of enzymatically degradable crosslinks results in cellular organization akin to the native salivary gland. Specifically, the apicobasolateral organization of tight junctions and polarized protein expression by secretory acinar cells reflect patterns seen in the intact salivary gland. These results indicate that cell-dictated matrix remodeling enhances the maintenance of polarized cell types within the hydrogels, which is a critical hurdle for salivary gland regenerative strategies.

This is the first study that examines how degradation modulates the behavior of primary SMG cells in vitro. Through careful consideration of PEG macromer chemistries, we have definitively isolated the role of hydrolytic, enzymatic, and combinations of the two degradation mechanisms (i.e., mixed mode degradation) on SMG cell phenotype and function. A significant number of previous studies utilized PEG hydrogels with MMP-degradability that are also susceptible to hydrolysis [36,38,42,63,64]. Such hydrogels are equivalent to the mixed mode-degradable hydrogels employed here. By designing hydrogels degradable only via cell-produced MMPs by deconvoluting hydrolytic- and MMP-degradation mechanisms, SMG cell organization is enhanced. Studies of salivary gland cell-ECM interactions performed using embryonic salivary gland tissue have shown the importance of salivary gland MMPs during development [53,60,62,65–67]. Adult salivary gland cells have also been shown to express multiple MMPs [59,68], which can degrade the peptide crosslinker employed here as cellular assembly ensues.

Hydrogel degradation can impact the function of a variety of hydrogel-encapsulated cell types. Naturally derived polymers, which have inherent cell-dictated degradability, have been found to enhance proliferation of salivary gland cells or spheres [10,12,24,27,30]. A link between increased hydrogel degradability and cell proliferation has also been established in studies using pancreatic cell lines and osteoblasts encapsulated within PEG hydrogels [64,69,70]. Similarly, MMP-degradable PEG hydrogels supported the function of encapsulated primary hepatocytes [71]. Encapsulation of pancreatic cell lines in MMP-degradable hydrogels not only increased proliferation, but also increased expression of epithelial markers β-catenin and E-cadherin when compared to hydrolytically-degradable controls [64]. Thus, the ability to degrade the surrounding matrix is critical to promote function of cultured cells in vitro.

Acinar cells are critical to restoring the function of irradiated salivary glands, but in vitro culture of primary acinar cells results in loss of the secretory cell phenotype. When cultured in 2D or encapsulated in hyaluronic acid hydrogels, spheres derived from human parotid gland are mainly comprised of keratin 5- and keratin 14-expressing duct/myoepithelial cells [30]. In contrast, expression of secretory acinar cell markers, including Aqp5, alpha amylase, and ZO-1, is enhanced within human parotid cell spheres cultured on photopatterned PEG hydrogels with nanofibrous PCL microwells [29]. The primary SMG cell population utilized in our study was heterogeneous, and the data suggest that the cells within the encapsulated spheres remain heterogeneous as they express acinar and duct cell markers. However, the sphere population was increasingly biased to the acinar cell phenotype through cellular degradability of hydrogels. Namely, MMP- and mixed mode-degradable hydrogels maintained higher SMG expression of acinar cell markers Aqp5 and Nkcc1 over 14 days of culture and showed polarized expression of Nkcc1 and ZO-1 proteins.

Although our results suggest that SMG cells retained characteristics similar to those in native salivary gland, we observed substantial reductions in expression of the acinar cell-specific transcription factor Mist1. Mist1 expression is required for acinar cells to maintain their polarity and secretory phenotype [72]. The expression of Mist1 is known to be reduced in response to acute injury or stress in pancreatic acinar cell populations [73,74]. We speculate that the downregulation of Mist1 might be a result of stress associated with in vitro culture. The concomitant decrease in expression of the secreted protein Pip in all hydrogels is consistent with loss of the secretory phenotype in acinar cells that still express Aqp5 and Nkcc1.

In the adult mouse salivary glands, acinar cells are replaced by self-duplication to maintain tissue homeostasis and after injury [75]. Ideally, proliferating acinar cells could be harnessed for regenerative strategies. However, loss of the acinar cell phenotype and Mist1 expression under in vitro conditions presents a hurdle to any approach utilizing primary salivary gland cells. Thus, a major focus of salivary gland tissue engineering approaches must be the promotion and/or maintenance of the acinar cell phenotype. During embryonic development, soluble factors such as acetylcholine, FGF-7, FGF-10, and TGF-β have been shown to play a critical role in organogenesis and epithelial morphogenesis of the salivary gland [76–79]. These soluble factors could be explored as a means to restore Mist1 expression in vitro. Supplementation of ascorbic acid in cultures of primary SMGs on silk fibroin hydrogels resulted in increased secretory granule formation, although Mist1 expression was not examined [80].

Biochemical and biophysical matrix cues can also be exploited to enhance acinar cell phenotype within tissue engineering approaches. Studies have shown the importance of numerous ECM proteins, especially basement membrane proteins, for salivary gland development [81]. In particular, laminin is vital for cell organization [51], proliferation [81], and α6β1 integrin mediated cell migration [82]. In this work, we did not investigate matrix proteins as a variable but included laminin in all hydrogels explored due to demonstrated efficacy for salivary gland tissue engineering approaches. Specifically, culture of salivary gland cells on fibrin hydrogel surfaces in the presence of laminin-111 protein and peptide derivatives was shown to promote lumen formation [27,52]. Further, a perlecan mimetic peptide used in hyaluronic acid hydrogels for the culture of primary salivary gland cells enhanced expression of polarized proteins and acinar cell markers [23–25].

5. Conclusion

We have examined the effects of different mechanisms of hydrogel degradation on encapsulated SMG cell populations. Incorporation of MMP-degradable peptide crosslinkers results in increased Aqp5 and Nkcc1 expression compared to SMG cells cultured in hydrolytically-degradable or non-degradable hydrogels. However, Mist1 and Pip expression was reduced irrespective of hydrogel degradation mechanism. Overall, these data suggest that while acinar cell phenotype is maintained in MMP-degradable hydrogels, functional secretion may not be. Nonetheless, SMG cells encapsulated within mixed mode- or MMP-degradable hydrogels showed polarized localization of basement and secretory membrane proteins as well as cellular organization within the spheres. These results highlight the role played by hydrogel degradability and the complex 3D cellular interactions maintained within spheres in vitro. In sum, PEG hydrogels are a promising platform to further study and control the interactions required for regeneration of functional salivary gland tissue.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

Regenerative strategies to replace damaged salivary glands require the function and organization of acinar cells. Hydrogel-based approaches have shown promise to control cell function and phenotype. However, little is known about how specific parameters, such as the mechanism of hydrogel degradation (e.g., hydrolytic or enzymatic), influence the viability, proliferation, organization, and phenotype of salivary gland cells. In this work, it is shown that hydrogel-encapsulated primary salivary gland cell proliferation is dependent upon hydrogel degradation. Hydrogels crosslinked with enzymatically degradable peptides promoted the expression of critical acinar cell markers, which are typically downregulated in primary cultures. Furthermore, salivary gland cells encapsulated in enzymatically- but not hydrolytically-degradable hydrogels displayed highly organized and polarized salivary gland cell markers, which mimics characteristics found in native gland tissue. In sum, results indicate that salivary gland

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by NIH R01DE022949, R56DE025098, F30CA183320, and the University of Rochester Medical Scientist Training Program grant (T32 GM7356). The authors would like to thank Dr. Donald Elbert for sharing the PEG amine chemistry protocol, Dr. David Yule for supplying IP3R3 antibody, Dr. Yvonne Myal for supplying Pip antibody, the Center for Musculoskeletal Research and Dr. James McGrath for use of their facilities, Dr. Linda Callahan and the URMC Imaging Core Facility for their help with confocal imaging, Dr. George Porter and Dr. Gisela Beutner for providing mice for submandibular glands, and Rachel Centner for animal husbandry. We would also like to thank Dominic Malcolm, Maureen Newman, and Prof. Lisa DeLouise for their assistance in editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data: Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2016.12.049.

References

- 1.Jensen SB, Pedersen AM, Vissink A, Andersen E, Brown CG, Davies AN, Dutilh J, Fulton JS, Jankovic L, Lopes NN, Mello AL, Muniz LV, Murdoch-Kinch CA, Nair RG, Napenas JJ, Nogueira-Rodrigues A, Saunders D, Stirling B, Von Bultzingslowen I, Weikel DS, Elting LS, Spijkervet FK, Brennan MT, Salivary S. Gland Hypofunction/Xerostomia, G. Oral Care Study, O. Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer /International Society of Oral, A systematic review of salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia induced by cancer therapies: management strategies and economic impact. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1061–1079. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0837-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vissink A, Jansma J, Spijkervet FK, Burlage FR, Coppes RP. Oral sequelae of head and neck radiotherapy. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:199–212. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arany S, Benoit DS, Dewhurst S, Ovitt CE. Nanoparticle-mediated gene silencing confers radioprotection to salivary glands in vivo. Mol Ther. 2013;21:1182–1194. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arany S, Xu Q, Hernady E, Benoit DS, Dewhurst S, Ovitt CE. Pro-apoptotic gene knockdown mediated by nanocomplexed siRNA reduces radiation damage in primary salivary gland cultures. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:1955–1965. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotrim AP, Sowers A, Mitchell JB, Baum BJ. Prevention of irradiation-induced salivary hypofunction by microvessel protection in mouse salivary glands. Mol Ther. 2007;15:2101–2106. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limesand KH, Barzen KA, Quissell DO, Anderson SM. Synergistic suppression of apoptosis in salivary acinar cells by IGF1 and EGF. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:345–355. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marmary Y, Adar R, Gaska S, Wygoda A, Maly A, Cohen J, Eliashar R, Mizrachi L, Orfaig-Geva C, Baum BJ, Rose-John S, Galun E, Axelrod JH. Radiation-induced loss of salivary gland function is driven by cellular senescence and prevented by IL6 modulation. Cancer Res. 2016;76:1170–1180. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin KL, Hill GA, Klein RR, Arnett DG, Burd R, Limesand KH. Prevention of radiation-induced salivary gland dysfunction utilizing a CDK inhibitor in a mouse model. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e51363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassolato SF, Turnbull RS. Xerostomia: clinical aspects and treatment. Gerodontology. 2003;20:64–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2003.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lombaert IM, Brunsting JF, Wierenga PK, Faber H, Stokman MA, Kok T, Visser WH, Kampinga HH, de Haan G, Coppes RP. Rescue of salivary gland function after stem cell transplantation in irradiated glands. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nanduri LS, Baanstra M, Faber H, Rocchi C, Zwart E, de Haan G, van Os R, Coppes RP. Purification and ex vivo expansion of fully functional salivary gland stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;3:957–964. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maimets M, Rocchi C, Bron R, Pringle S, Kuipers J, Giepmans BN, Vries RG, Clevers H, de Haan G, van Os R, Coppes RP. Long-term in vitro expansion of salivary gland stem cells driven by Wnt Signals. Stem Cell Rep. 2016;6:150–162. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quissell DO, Redman RS, Mark MR. Short-term primary culture of acinar-intercalated duct complexes from rat submandibular glands. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1986;22:469–480. doi: 10.1007/BF02623448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redman RS, Quissell DO, Barzen KA. Effects of dexamethasone, epidermal growth factor, and retinoic acid on rat submandibular acinar-intercalated duct complexes in primary culture. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1988;24:734–742. doi: 10.1007/BF02623642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quissell DO, Redman RS, Barzen KA, McNutt RL. Effects of oxygen, insulin, and glucagon concentrations on rat submandibular acini in serum-free primary culture. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1994;30A:833–842. doi: 10.1007/BF02639393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman MD, Benoit DS. Emerging ideas: engineering the periosteum: revitalizing allografts by mimicking autograft healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:721–726. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2695-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman MD, Xie C, Zhang X, Benoit DS. The effect of mesenchymal stem cells delivered via hydrogel-based tissue engineered periosteum on bone allograft healing. Biomaterials. 2013;34:8887–8898. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffman MD, Van Hove AH, Benoit DS. Degradable hydrogels for spatiotemporal control of mesenchymal stem cells localized at decellularized bone allografts. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:3431–3441. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lam J, Lowry WE, Carmichael ST, Segura T. Delivery of iPS-NPCs to the stroke cavity within a hyaluronic acid matrix promotes the differentiation of transplanted cells. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24:7053–7062. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201401483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han S, Hoffman MD, Proctor AR, Vella JB, Mannoh EA, Barber NE, Kim HJ, Jung KW, Benoit DS, Choe R. Non-invasive monitoring of temporal and spatial blood flow during bone graft healing using diffuse correlation spectroscopy. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0143891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han S, Johansson J, Mireles M, Proctor AR, Hoffman MD, Vella JB, Benoit DS, Durduran T, Choe R. Non-contact scanning diffuse correlation tomography system for three-dimensional blood flow imaging in a murine bone graft model. Biomed Opt Exp. 2015;6:2695–2712. doi: 10.1364/BOE.6.002695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman MD, Benoit DS. Emulating native periosteum cell population and subsequent paracrine factor production to promote tissue engineered periosteum-mediated allograft healing. Biomaterials. 2015;52:426–440. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pradhan S, Liu C, Zhang C, Jia X, Farach-Carson MC, Witt RL. Lumen formation in three-dimensional cultures of salivary acinar cells. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pradhan-Bhatt S, Harrington DA, Duncan RL, Jia X, Witt RL, Farach-Carson MC. Implantable three-dimensional salivary spheroid assemblies demonstrate fluid and protein secretory responses to neurotransmitters. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:1610–1620. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pradhan-Bhatt S, Harrington DA, Duncan RL, Farach-Carson MC, Jia X, Witt RL. A novel in vivo model for evaluating functional restoration of a tissue-engineered salivary gland. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:456–461. doi: 10.1002/lary.24297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCall AD, Nelson JW, Leigh NJ, Duffey ME, Lei P, Andreadis ST, Baker OJ. Growth factors polymerized within fibrin hydrogel promote amylase production in parotid cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:2215–2225. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maruyama CL, Leigh NJ, Nelson JW, McCall AD, Mellas RE, Lei P, Andreadis ST, Baker OJ. Stem cell-soluble signals enhance multilumen formation in SMG cell clusters. J Dent Res. 2015;94:1610–1617. doi: 10.1177/0022034515600157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shubin AD, Felong TJ, Graunke D, Ovitt CE, Benoit DS. Development of poly (ethylene glycol) hydrogels for salivary gland tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015 doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shin HS, Kook YM, Hong HJ, Kim YM, Koh WG, Lim JY. Functional spheroid organization of human salivary gland cells cultured on hydrogel-micropatterned nanofibrous microwells. Acta Biomater. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srinivasan PP, Patel VN, Liu S, Harrington DA, Hoffman MP, Jia X, Witt RL, Farach-Carson MC, Pradhan-Bhatt S. Primary Salivary Human Stem/Progenitor Cells Undergo Microenvironment-Driven Acinar-Like Differentiation in Hyaluronate Hydrogel Culture. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016 doi: 10.5966/sctm.2016-0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toole BP. Hyaluronan: from extracellular glue to pericellular cue. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:528–539. doi: 10.1038/nrc1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noel A, De Pauw-Gillet MC, Purnell G, Nusgens B, Lapiere CM, Foidart JM. Enhancement of tumorigenicity of human breast adenocarcinoma cells in nude mice by matrigel and fibroblasts. Br J Cancer. 1993;68:909–915. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes CS, Postovit LM, Lajoie GA. Matrigel: a complex protein mixture required for optimal growth of cell culture. Proteomics. 2010;10:1886–1890. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin CC, Anseth KS. Cell-cell communication mimicry with poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels for enhancing beta-cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6380–6385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014026108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKinnon DD, Kloxin AM, Anseth KS. Synthetic hydrogel platform for three-dimensional culture of embryonic stem cell-derived motor neurons. Biomater Sci Uk. 2013;1:460–469. doi: 10.1039/c3bm00166k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin TY, Ki CS, Lin CC. Manipulating hepatocellular carcinoma cell fate in orthogonally cross-linked hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2014;35:6898–6906. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benoit DS, Schwartz MP, Durney AR, Anseth KS. Small functional groups for controlled differentiation of hydrogel-encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Mater. 2008;7:816–823. doi: 10.1038/nmat2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson SB, Lin CC, Kuntzler DV, Anseth KS. The performance of human mesenchymal stem cells encapsulated in cell-degradable polymer-peptide hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3564–3574. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grim JC, Marozas IA, Anseth KS. Thiol-ene and photo-cleavage chemistry for controlled presentation of biomolecules in hydrogels. J Control Release. 2015;219:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang Y, Chen J, Deng C, Suuronen EJ, Zhong Z. Click hydrogels, microgels and nanogels: emerging platforms for drug delivery and tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2014;35:4969–4985. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fairbanks BD, Schwartz MP, Bowman CN, Anseth KS. Photoinitiated polymerization of PEG-diacrylate with lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate: polymerization rate and cytocompatibility. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6702–6707. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fairbanks BD, Schwartz MP, Halevi AE, Nuttelman CR, Bowman CN, Anseth KS. A versatile synthetic extracellular matrix mimic via thiol-norbornene photopolymerization. Adv Mater. 2009;21:5005–5010. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Hove AH, Beltejar MJG, Benoit DS. Development and in vitro assessment of enzymatically-responsive poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels for the delivery of therapeutic peptides. Biomaterials. 2014;35:9719–9730. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patterson J, Hubbell JA. Enhanced proteolytic degradation of molecularly engineered PEG hydrogels in response to MMP-1 and MMP-2. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7836–7845. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Hove AH, Antonienko E, Burke K, Brown E, 3rd, Benoit DS. Temporally tunable, enzymatically responsive delivery of proangiogenic peptides from poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2015;4:2002–2011. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Hove AH, Antonienko E, Burke K, Brown E, 3rd, Benoit DS. Enzymatically-responsive pro-angiogenic peptide-releasing poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels promote vascularization in vivo. J Control Release. 2015;217:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anthis NJ, Clore GM. Sequence-specific determination of protein and peptide concentrations by absorbance at 205 nm. Protein Sci. 2013;22:851–858. doi: 10.1002/pro.2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turturro MV, Christenson MC, Larson JC, Young DA, Brey EM, Papavasiliou G. MMP-sensitive PEG diacrylate hydrogels with spatial variations in matrix properties stimulate directional vascular sprout formation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.West JL, Hubbell JA. Polymeric biomaterials with degradation sites for proteases involved in cell migration. Macromolecules. 1999;32:241–244. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rugel-Stahl A, Elliott ME, Ovitt CE. Ascl3 marks adult progenitor cells of the mouse salivary gland. Stem Cell Res. 2012;8:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kadoya Y, Kadoya K, Durbeej M, Holmvall K, Sorokin L, Ekblom P. Antibodies against domain E3 of laminin-1 and integrin alpha 6 subunit perturb branching epithelial morphogenesis of submandibular gland, but by different modes. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:521–534. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.2.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nam K, Jones JP, Lei P, Andreadis ST, Baker OJ. Laminin-111 peptides conjugated to fibrin hydrogels promote formation of lumen containing parotid gland cell clusters. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17:2293–2301. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rebustini IT, Patel VN, Stewart JS, Layvey A, Georges-Labouesse E, Miner JH, Hoffman MP. Laminin alpha5 is necessary for submandibular gland epithelial morphogenesis and influences FGFR expression through beta1 integrin signaling. Develop Biol. 2007;308:15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruan JL, Tulloch NL, Muskheli V, Genova EE, Mariner PD, Anseth KS, Murry CE. An improved cryosection method for polyethylene glycol hydrogels used in tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2013;19:794–801. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2012.0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anseth KS, Metters AT, Bryant SJ, Martens PJ, Elisseeff JH, Bowman CN. In situ forming degradable networks and their application in tissue engineering and drug delivery. J Control Release. 2002;78:199–209. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00500-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW. Expression of SIBLINGs and their partner MMPs in salivary glands. J Dent Res. 2004;83:664–670. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perez P, Goicovich E, Alliende C, Aguilera S, Leyton C, Molina C, Pinto R, Romo R, Martinez B, Gonzalez MJ. Differential expression of matrix metalloproteinases in labial salivary glands of patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2807–2817. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)43:12<2807::AID-ANR22>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamachika S, Nanni JM, Nguyen KH, Garces L, Lowry JM, Robinson CP, Brayer J, Oxford GE, da Silveira A, Kerr M, Peck AB, Humphreys-Beher MG. Excessive synthesis of matrix metalloproteinases in exocrine tissues of NOD mouse models for Sjogren's syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:2371–2380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oblander SA, Zhou Z, Galvez BG, Starcher B, Shannon JM, Durbeej M, Arroyo AG, Tryggvason K, Apte SS. Distinctive functions of membrane type 1 matrix-metalloprotease (MT1-MMP or MMP-14) in lung and submandibular gland development are independent of its role in pro-MMP-2 activation. Develop Biol. 2005;277:255–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baker OJ. Tight junctions in salivary epithelium. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:278948. doi: 10.1155/2010/278948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sequeira SJ, Larsen M, DeVine T. Extracellular matrix and growth factors in salivary gland development. Front Oral Biol. 2010;14:48–77. doi: 10.1159/000313707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin CC, Raza A, Shih H. PEG hydrogels formed by thiol-ene photo-click chemistry and their effect on the formation and recovery of insulin-secreting cell spheroids. Biomaterials. 2011;32:9685–9695. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raza A, Ki CS, Lin CC. The influence of matrix properties on growth and morphogenesis of human pancreatic ductal epithelial cells in 3D. Biomaterials. 2013;34:5117–5127. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nelson DA, Larsen M. Heterotypic control of basement membrane dynamics during branching morphogenesis. Develop Biol. 2015;401:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ekblom P, Ekblom M, Fecker L, Klein G, Zhang HY, Kadoya Y, Chu ML, Mayer U, Timpl R. Role of mesenchymal nidogen for epithelial morphogenesis in vitro. Development. 1994;120:2003–2014. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.7.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rebustini IT, Myers C, Lassiter KS, Surmak A, Szabova L, Holmbeck K, Pedchenko V, Hudson BG, Hoffman MP. MT2-MMP-dependent release of collagen IV NC1 domains regulates submandibular gland branching morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2009;17:482–493. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muramatsu T, Ohta K, Asaka M, Kizaki H, Shimono M. Expression and distribution of osteopontin and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-3 and-7 in mouse salivary glands. Eur J Morphol. 2002;40:209–212. doi: 10.1076/ejom.40.4.209.16689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Benoit DS, Durney AR, Anseth KS. Manipulations in hydrogel degradation behavior enhance osteoblast function and mineralized tissue formation. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1663–1673. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Raza A, Lin CC. The influence of matrix degradation and functionality on cell survival and morphogenesis in PEG-based hydrogels. Macromol Biosci. 2013;13:1048–1058. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201300044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stevens KR, Miller JS, Blakely BL, Chen CS, Bhatia SN. Degradable hydrogels derived from PEG-diacrylamide for hepatic tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2015;103:3331–3338. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Direnzo D, Hess DA, Damsz B, Hallett JE, Marshall B, Goswami C, Liu Y, Deering T, Macdonald RJ, Konieczny SF. Induced Mist1 expression promotes remodeling of mouse pancreatic acinar cells. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:469–480. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jia D, Sun Y, Konieczny SF. Mist1 regulates pancreatic acinar cell proliferation through p21 CIP1/WAF1. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1687–1697. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Karki A, Humphrey SE, Steele RE, Hess DA, Taparowsky EJ, Konieczny SF. Silencing Mist1 gene expression is essential for recovery from acute pancreatitis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0145724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aure MH, Konieczny SF, Ovitt CE. Salivary gland homeostasis is maintained through acinar cell self-duplication. Dev Cell. 2015;33:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Knox SM, Lombaert IM, Haddox CL, Abrams SR, Cotrim A, Wilson AJ, Hoffman MP. Parasympathetic stimulation improves epithelial organ regeneration. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1494. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Patel VN, Hoffman MP. Salivary gland development: a template for regeneration. Semin Cell Dev Biol 25–. 2014;26:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Knox SM, Lombaert IM, Reed X, Vitale-Cross L, Gutkind JS, Hoffman MP. Parasympathetic innervation maintains epithelial progenitor cells during salivary organogenesis. Science. 2010;329:1645–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1192046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Peters SB, Nelson DA, Kwon HR, Koslow M, DeSantis KA, Larsen M. TGFbeta signaling promotes matrix assembly during mechanosensitive embryonic salivary gland restoration. Matrix Biol. 2015;43:109–124. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang BX, Zhang ZL, Lin AL, Wang H, Pilia M, Ong JL, Dean DD, Chen XD, Yeh CK. Silk fibroin scaffolds promote formation of the ex vivo niche for salivary gland epithelial cell growth, matrix formation, and retention of differentiated function. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21:1611–1620. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sequeira SJ, Larsen M, DeVine T. Extracellular matrix and growth factors in salivary gland development. Front Oral Biol. 2010;14:48–77. doi: 10.1159/000313707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hsu JC, Koo H, Harunaga JS, Matsumoto K, Doyle AD, Yamada KM. Region-specific epithelial cell dynamics during branching morphogenesis. Develop Dynam. 2013;242:1066–1077. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.