Abstract

As the number of older patients with cancer is increasing, oncology disciplines are faced with the challenge of managing patients with multiple chronic conditions who have difficulty maintaining independence, who may have cognitive impairment, and who also may be more vulnerable to adverse outcomes. National and international societies have recommended that all older patients with cancer undergo geriatric assessment (GA) to detect unaddressed problems and introduce interventions to augment functional status to possibly improve patient survival. Several predictive models have been developed, and evidence has shown correlation between information obtained through GA and treatment-related complications. Comprehensive geriatric evaluations and effective interventions on the basis of GA may prove to be challenging for the oncologist because of the lack of the necessary skills, time constraints, and/or limited available resources. In this article, we describe how the Geriatrics Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center approaches an older patient with colon cancer from presentation to the end of life, show the importance of GA at the various stages of cancer treatment, and how predictive models are used to tailor the treatment. The patient’s needs and preferences are at the core of the decision-making process. Development of a plan of care should always include the patient’s preferences, but it is particularly important in the older patient with cancer because a disease-centered approach may neglect noncancer considerations. We will elaborate on the added value of co-management between the oncologist and a geriatric nurse practitioner and on the feasibility of adapting elements of this model into busy oncology practices.

INTRODUCTION

The country’s population is aging, and the burden of cancer is expected to increase along with the need for specialized services and for programs to address those needs.1,2 The clinical behavior of some tumors changes with age, and the aging process frequently brings physiologic changes that result in decline in organ function.3-5 Patients’ functional age may differ from their chronological age, and that difference needs to be integrated into the decision-making process for cancer treatment. Some older patients may be as fit as younger patients, others may have a marginal decline in physiologic reserve, and yet others may be frail.6 It is essential to identify those patients who are fit and potentially more resilient because they are more likely to benefit from standard treatment.7 Fit older adults have few comorbidities, no functional deficits, and few (if any) geriatric syndromes such as falls or dementia. In contrast, frail patients have multiple chronic conditions, have difficulty maintaining independence, may have cognitive impairment, and are far more vulnerable to adverse outcomes and toxicities from therapy. As a result, frail patients may not experience substantial lasting treatment benefits because of multiple factors that pose competing risks for morbidity and mortality.8

Patient-centered care has become a central aim for the nation’s health care system. The Institute of Medicine defines patient-centered care as “Providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”9 Patient-centered practices are especially important for the older patient with cancer whose care often involves multiple clinicians and the administration of potentially toxic therapy. For these patients, assessment of function, cognition, and other domains of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment are central to patient-centered care.10

The following case illustrates how patient-centered principles are incorporated into the care of older adults with cancer. As described in an accompanying article,11 Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) established a Geriatrics Service (GS) in the Department of Medicine, acknowledging that the care of older patients with cancer would be optimized by a specialty service. When treatment and supportive measures are appropriately tailored, control of the disease with an acceptable quality of life may be achieved. Interdisciplinary care and communication are needed to provide effective care with a patient-centered approach across cancer continuum.

THE CASE OF AN 88-YEAR-OLD PATIENT WITH COLON CANCER

The patient is an 88-year-old female with a medical history significant for hypertension, osteoarthritis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease who presented with abdominal pain and anemia. A colonoscopy showed a mass in the ascending colon. Pathology was consistent with moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. She presented for management to the MSKCC Colorectal Surgery Service. Hemicolectomy was considered the standard of care, and she was referred to the GS for preoperative evaluation.

Preoperative Management

Older surgical patients with cancer have unique vulnerabilities that require assessment beyond the traditional preoperative evaluation.12 The depleted physiologic reserve of an elderly patient is not always apparent, and established assessment tools such as Karnofsky performance status13 are not sufficiently sensitive to predict operative risk.14 Geriatricians use the geriatric assessment (GA), a multidisciplinary evaluation that often reveals information missed by routine history and physical examination alone. Its value in predicting surgical outcomes has been extensively reported.12,15-19 The American College of Surgeons, in collaboration with the American Geriatric Society, created best-practice guidelines to identify high-risk patients, prevent perioperative adverse outcomes, and achieve optimal care of the older surgical patient by performing preoperative GA.20 However, a recent study has shown that only 6% of surgeons routinely perform preoperative GA.21

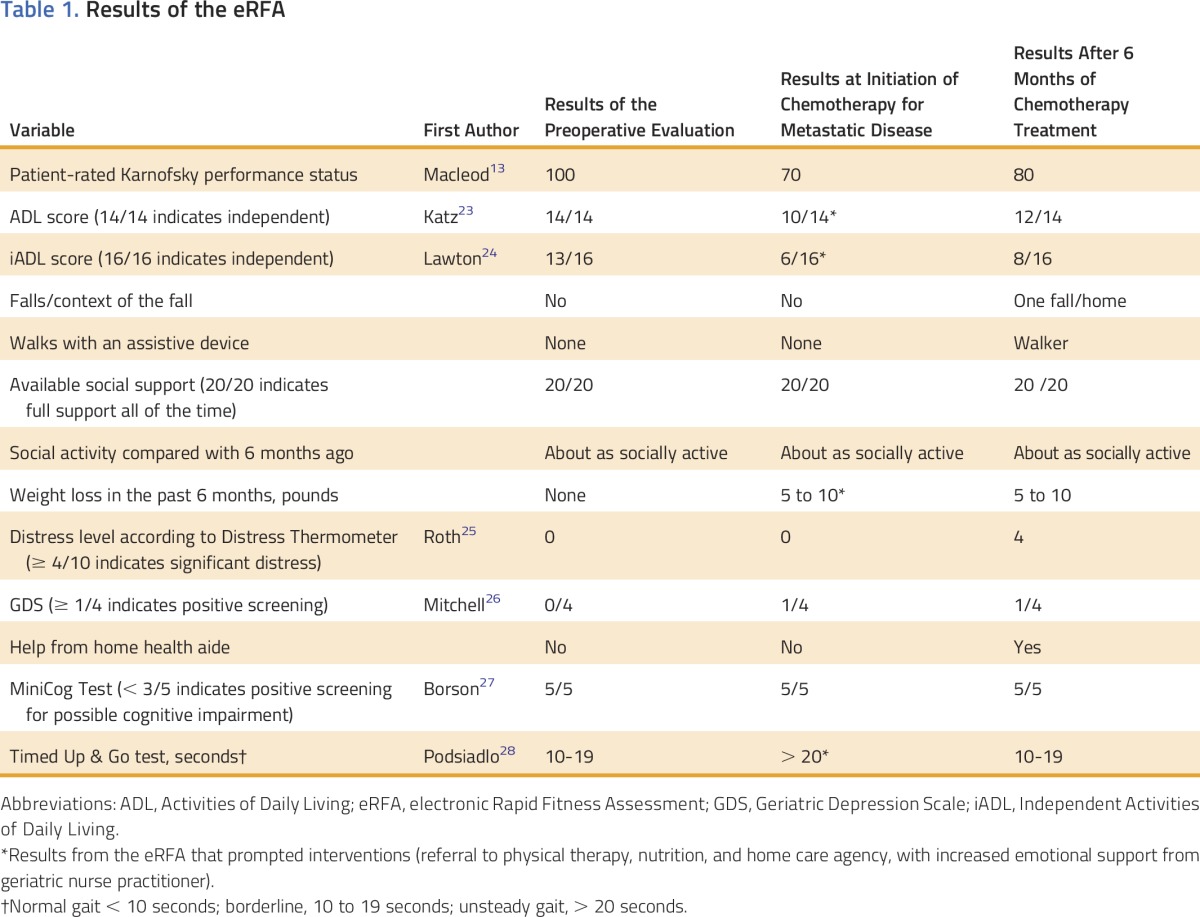

At MSKCC, we developed a brief electronic evaluation tool, named electronic Rapid Fitness Assessment (eRFA), that captures patient-reported data by using validated tools included in the GA.22 The eRFA has become the standard of care for all older adults evaluated in our geriatric clinics.

The patient underwent GA in addition to the usual preoperative evaluation. She was found to be a fit patient. She had few comorbidities and only one hospitalization for an appendectomy, and her only medications were two antihypertensives and a proton pump inhibitor. She had not experienced weight loss and was able to take care of herself. Screening for cognitive impairment was negative, and she had good social support. Vitals, physical examination, and laboratory data were unremarkable. Results of the eRFA are presented in Table 1. The patient underwent hemicolectomy.

Table 1.

Results of the eRFA

Surgical Treatment in the Older Patient With Cancer

More than half of patients with colorectal cancer are older than age 65 years, and approximately 70% have early-stage disease in which surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment.29 Age alone should not be an indication for less-than-standard therapy. However, elderly patients may present with significant comorbidities, such as cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, which influence postoperative mortality and morbidity.30 Careful patient selection for surgical procedures is important because frail elderly patients are at higher risk for complications compared with their fit counterparts.14 Several models for predicting postoperative morbidity and mortality in the general population and in the elderly have been developed (eg, Physiologic and Operative Severity Score for the Enumeration of Mortality and Morbidity [POSSUM]).31 The Preoperative Assessment of Cancer in the Elderly (PACE) is a valuable tool for the decision-making process concerning the candidacy of elderly patients with cancer for surgical intervention.19,32

At MSKCC, in addition to eRFA, we use the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program risk calculator to estimate the chance of an unfavorable outcome.33 The patient’s risk for postoperative adverse outcomes was average. However, she had a three times higher risk for being discharged to a nursing home or rehabilitation facility compared with an average-risk person (22.1% v 8.1%). The risk was discussed with the patient and her family members who were willing to provide the necessary support.

Postoperative Management

The patient’s postoperative recovery was uneventful. Her length of stay was 5 days. The GS managed the patient with the Colorectal Surgery Service postoperatively. Measures for the prevention of delirium were encouraged; the physical therapist was able to get her walking on postoperative day 1. The importance of incentive spirometry was discussed with the patient and her family. Given the rate of recovery and availability of support at home, the patient was discharged without additional services. Surgical pathology showed T2N0M0, and none of the 25 resected lymph nodes were positive.

Postoperatively, older patients are at increased risk for additional complications often referred to as “hazards of hospitalization,” which include delirium, malnutrition, pressure ulcers, falls, restraint use, functional decline, adverse drug effects, and death.34 One third of hospitalized older adults develop a new disability, and at least 20% of older patients develop delirium during hospitalization.35 Postoperative delirium increases length of stay, costs, morbidity, and mortality.36 It is a risk factor for institutionalization that, in turn, may not be an acceptable change in quality of life for the patient and is an enormous source of apprehension for the patient’s family. Older patients with cancer and their families should be educated about the possibility of postoperative delirium so that they can be psychologically prepared.

At MSKCC, the inpatient GS focuses on adequate pain management through education of the patient and his or her family about patient-controlled analgesia, correct and frequent use of incentive spirometry, early mobilization, and delirium risk reduction interventions.35

Home Management

After being discharged, the patient returned to her home in another state. Approximately a year later, she presented to a local oncologist with peritoneal metastatic disease. She was treated with capecitabine 500 mg twice per day. She presented to an emergency room in her town with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting and was found to have a small bowel obstruction as a result of progression of disease at the ileocolic anastomosis. A stent was placed, and she was referred for hospice care. The family decided to seek a second opinion from the MSKCC Gastrointestinal Oncology Service.

At the time of the evaluation, the patient was recovering slowly from recent stent placement. Her appetite was poor and she had lost 7 to 10 pounds; albumin level was 2.4 g/dL. Her gait was unstable. Computed tomography showed peritoneal tumor implants and pulmonary metastatic lesions. The consulting MSKCC oncologist had extensive discussions with the patient regarding life expectancy as a result of cancer in the context of her overall life expectancy, patient’s goals and values regarding management of the cancer, and the risks and benefits of chemotherapy.37 Because the patient’s goals were consistent with wanting anticancer therapy, she was referred to the GS for advice on co-management of symptoms and supportive care. A GA was obtained through the eRFA (Table 1). On the basis of those results, the patient was referred to a nutritionist and physical therapist.

Prediction of Chemotherapy Toxicity in the Older Patient With Cancer

Over the last decade, GA has been found to influence treatment decisions, such as the reduction of the intensity of chemotherapy or providing additional supportive care.38,39 The GA helps to better tailor individualized treatment to an older patient who might otherwise be at greater toxicity risk. For these reasons, the International Society of Geriatric Oncology recommends that the findings from GA should be incorporated into oncology treatment decisions.39

How comprehensive and detailed a GA should be depends on the intended use and the available resources. For risk stratification before chemotherapy, brief tools based on GA are efficient in determining a patient’s predicted risk of toxicity from chemotherapy. The Cancer and Aging Research Group developed and recently validated a predictive model that includes GA variables and patient demographic and clinical variables and predicts grade 3 to 5 toxicity with administration of chemotherapy.40,41

By using the Cancer and Aging Research Group instrument, her predicted risk for level 3 to 5 chemotherapy toxicity for dose-reduced single agent, standard-dose single agent, dose-reduced doublet, and standard-dose doublet chemotherapy was 58%, 72%, 72%, and 82%, respectively. In accordance with a shared decision with the patient and family, she was treated initially with dose-reduced single agent: fluorouracil 600 mg/m2 intravenous continuous infusion and 200 mg/m2 as an intravenous push. At the same time, the patient was observed regularly by the GS Nurse Practitioner (GNP) for supportive care.

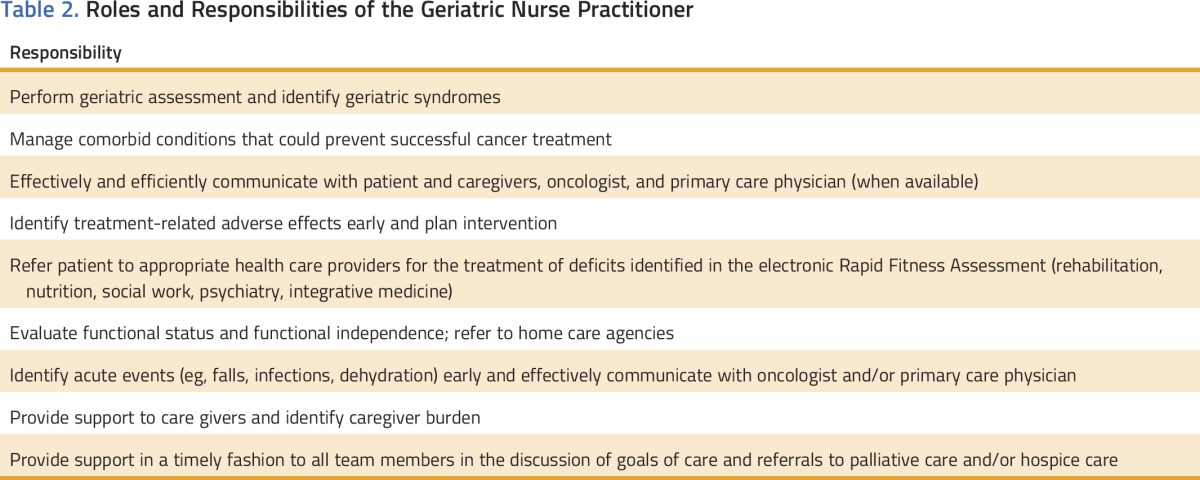

Oncologist and GNP Collaborative Care Model

At MSKCC, we developed an oncologist and GNP collaborative care model to provide care to older patients who have multiple comorbidities while they are undergoing cancer treatment. This model involves the patient to the extent of his or her ability, the patient’s personal support system, the oncologist, and a GNP who communicates with the patient’s local primary care provider (PCP) if one is available. The plan of care is developed jointly to establish goals that are synergistic and patient centered. The number of practicing geriatricians in the United States is limited, and their specialized knowledge must be leveraged to help as many patients as possible.42 GNPs are well positioned to fill the need for geriatric care in the population of patients with cancer. At MSKCC, GNPs are involved in four types of interventions: education, prevention, supportive care, and symptom management. They focus on early assessment of symptoms, timely interventions, proactive follow-up, and coordination of care (Table 2).

Table 2.

Roles and Responsibilities of the Geriatric Nurse Practitioner

Treatment Course

The patient tolerated dose-reduced fluorouracil well. Through visits and/or phone calls with the GNP, several issues were addressed: treatment-related adverse effects (oral ulcers, rash, nausea), uncontrolled hypertension, constipation, anorexia and weight loss, vitamin D deficiency, osteoporosis, and functional status. Her level of function improved and she was even able to visit her out-of-state family. After 10 months of receiving fluorouracil, scans showed progression of disease, and her treatment was switched to dose-reduced irinotecan. Two months later, her disease showed progression, and after discussion with the patient and her family, they agreed to treatment with dose-reduced regorafenib. With the supportive care provided by the GNP, the patient had no hospitalizations for 14 months after she presented to the MSKCC Gastrointestinal Oncology Service with metastatic disease. Two months into treatment with regorafenib, she was admitted to the hospital and was diagnosed with a small bowel obstruction. Palliative care was consulted and hospice care was offered. The patient died comfortably at home 4 weeks later.

Maintaining and improving functional activity and quality of life of older patients with cancer is essential during their course of treatment. Although the oncologist is mainly focused on managing the cancer and addressing toxicity as a result of chemotherapy, the GNP is focused on other aspects of well-being for older patients with cancer (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Practical strategies are needed to recognize the unique status of each older patient with cancer and effectively manage his or her cancer in the context of multiple noncancer-related issues. In this case study, we have described an example of the implementation of the model of care for older adults that has been adopted by the GS at MSKCC. This model of care is on the basis of the following three principles.

Chronological Age May Differ From Functional Age

First, both chronological and functional age must be evaluated, the difference must be recognized, and the functional age must be integrated into the decision-making process to avoid undertreatment of fit older adults or overtreatment of frail patients with limited life expectancy. GA has slowly been embraced by the oncology community.10 National and international societies have recommended that all older patients with cancer undergo GA to detect unaddressed problems and to introduce interventions to augment functional status and possibly improve their survival. However, the optimal approach to the care of this population is not yet completely established.37,43 In older, noncancer patients, GA with subsequent management on the basis of the assessment findings has been shown to improve a variety of outcomes, such as reducing functional decline and the use of health care resources.44 However, in the older adult with cancer, the role of GA is less well established, and clinical trials are necessary to develop the evidence base needed to support its use in routine oncology care.45

Patient-Centered Care

Caring for older patients with cancer is frequently complex, both medically as a result of comorbidities and polypharmacy and psychosocially as a result of variable social support and financial constraints. These issues may be the cause of failure in cancer treatment. The first step in the cancer treatment decision-making process is asking the question “Is the patient at moderate or high risk of dying or suffering from cancer considering his or her overall life expectancy?”37 Neurocognitive disorders, such as dementia and delirium, are accompanied by a high degree of morbidity and mortality and need to be considered before treatment starts. Ethical considerations emerge when cognitive dysfunction is detected. Understanding the ways in which comorbid cognitive dysfunction impacts both cancer and noncancer-related outcomes is essential in guiding treatment decisions.37,46

High-quality, patient-centered care is of vital importance to patients and families. Development of a plan of care should always include the patient’s preferences, but it is particularly important in the older patient with cancer because a disease-centered approach may neglect noncancer considerations.47,48

Communication

The care of older patients with cancer often requires input from multiple disciplines. To avoid fragmented care, all providers involved must develop and monitor the treatment plan. The MSKCC GS adopted a model of care that incorporates the concept of care shared by various disciplines but stresses the key role of the oncologist and PCP or geriatrician.49 A team captain is necessary to ensure that the patient and family receive a single message. Early in the course of therapy the captain is usually the oncologist, with transition to the geriatrician or PCP as treatment trends toward its conclusion, whether it be successful or unsuccessful.49

A GNP can be an invaluable asset in a busy oncology practice. Physicians’ interest in a career in geriatric medicine continues to wane at a time when the health care needs of older adults are increasing. GNPs have helped fill the physician gap in the United States.50 The roles and responsibilities depicted in Table 2 promote holistic care and reduce unnecessary use of resources by responding proactively to patient needs while providing a unique nursing perspective.51

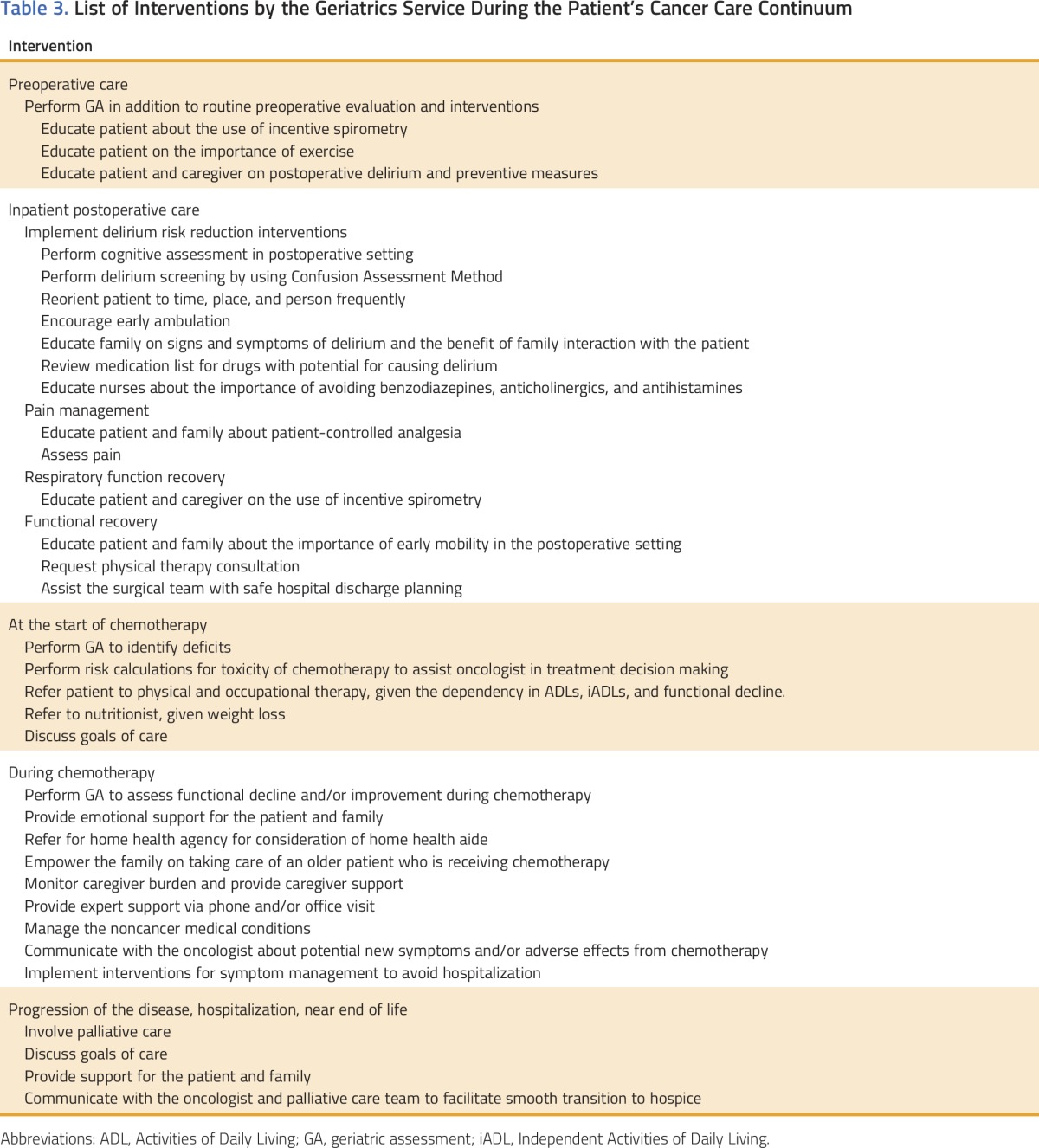

FEASIBILITY

The feasibility (eg, financial, space, manpower) of this model of care in other academic or community institutions, large or small group practices, or individual practitioner settings is frequently questioned. MSKCC invested its resources because of the number of older patients with cancer seen each year.11 However, oncologists in all other practice settings encounter the same difficulties in caring for older adults with cancer (eg, comorbidities, cognitive impairment, lack of social support). Table 3 lists the GS interventions incorporated into the care of the patient we discussed in this article. They are numerous and require a significant investment in resources. However, not all need to be implemented. Choosing the one or two feasible for a particular practice may have a large impact. For example, small interventions such as watching the patient walk (the Timed Up and Go test takes less than 20 seconds)28 could be the difference between early recognition of gait disturbance with referral to physical therapy and a fall that could jeopardize cancer treatment and patient survival. Screening of cognitive impairment by performing a MiniCog test (2 to 3 minutes)27 could be the basis for the education of the patient and his or her family about the possibility of worsening cognition or functional dependency as a result of treatment and will allow them to make a more informed decision.

Table 3.

List of Interventions by the Geriatrics Service During the Patient’s Cancer Care Continuum

We are also frequently confronted with the question: What would I do with the results of these evaluations? Not all communities have allied health professionals that the patient can be referred to. However, awareness of the issues will lead to a search for local solutions, better decision making, better communication, and improved patient satisfaction.

In conclusion, data show that age by itself should not be the main decision factor for treatment in older patients with cancer. Proper selection of patients by consideration of functional age results in outcomes similar to those in younger patients. Keeping a patient-centered mindset and enabling older patients to be involved in choices are crucial to providing effective and efficient care. Communication among members of the care team is the key to avoiding fragmented care, unnecessary expense, and unwanted outcomes. Targeted interventions could result in significant improvements in the quality of life of the older patient with cancer throughout the cancer continuum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by Core Grant No. P30 CA008748 from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Collection and assembly of data: Armin Shahrokni, Soo Jung Kim, Beatriz Korc-Grodzicki

Data analysis and interpretation: Armin Shahrokni, Soo Jung Kim, Beatriz Korc-Grodzicki

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

How We Care for an Older Patient With Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jop/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Armin Shahrokni

No relationship to disclose

Soo Jung Kim

No relationship to disclose

George J. Bosl

No relationship to disclose

Beatriz Korc-Grodzicki

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Hurria A, Naylor M, Cohen HJ. Improving the quality of cancer care in an aging population: Recommendations from an IOM report. JAMA. 2013;310:1795–1796. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, et al. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: Burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolignano D, Mattace-Raso F, Sijbrands EJ, et al. The aging kidney revisited: A systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;14:65–80. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janssens JP, Pache JC, Nicod LP. Physiological changes in respiratory function associated with ageing. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:197–205. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13a36.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geiger H, de Haan G, Florian MC. The ageing haematopoietic stem cell compartment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:376–389. doi: 10.1038/nri3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balducci L. Frailty: A common pathway in aging and cancer. Interdiscip Top Gerontol. 2013;38:61–72. doi: 10.1159/000343586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baijal P, Periyakoil V. Understanding frailty in cancer patients. Cancer J. 2014;20:358–366. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd CM, McNabney MK, Brandt N, et al. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: An approach for clinicians—American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:E1–E25. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2001. http://www.nap.edu/books/0309072808/html/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korc-Grodzicki B, Holmes HM, Shahrokni A. Geriatric assessment for oncologists. Cancer Biol Med. 2015;12:261–274. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2015.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korc-Grodzicki B, Tew WP, Hurria A, et al: Development of a geriatric service in a cancer center: Lessons learned. J Oncol Pract 13:107-112, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson TN, Eiseman B, Wallace JI, et al. Redefining geriatric preoperative assessment using frailty, disability and co-morbidity. Ann Surg. 2009;250:449–455. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b45598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schag CC, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA. Karnofsky performance status revisited: Reliability, validity, and guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:187–193. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kristjansson SR, Nesbakken A, Jordhøy MS, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment can predict complications in elderly patients after elective surgery for colorectal cancer: A prospective observational cohort study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;76:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim KI, Park KH, Koo KH, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment can predict postoperative morbidity and mortality in elderly patients undergoing elective surgery. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56:507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revenig LM, Canter DJ, Taylor MD, et al. Too frail for surgery? Initial results of a large multidisciplinary prospective study examining preoperative variables predictive of poor surgical outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:665–670.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson TN, Wu DS, Pointer LF, et al. Preoperative cognitive dysfunction is related to adverse postoperative outcomes in the elderly. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.PACE participants. Audisio RA, Pope D, et al. Shall we operate? Preoperative assessment in elderly cancer patients (PACE) can help: A SIOG surgical task force prospective study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chow WB, Rosenthal RA, Merkow RP, et al. Optimal preoperative assessment of the geriatric surgical patient: A best practices guideline from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:453–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghignone F, van Leeuwen BL, Montroni I, et al. The assessment and management of older cancer patients: A SIOG surgical task force survey on surgeons’ attitudes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shahrokni A, Vickers AJ, Mahmouzadeh S, et al. Assessing the clinical feasibility of electronic Rapid Fitness Assessment (eRFA): A novel geriatric assessment tool for the oncology setting. J Clin Oncol. 2016 (suppl; abstr 10011);34 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: Activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31:721–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb03391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, et al. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: A pilot study. Cancer. 1998;82:1904–1908. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980515)82:10<1904::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell AJ, Bird V, Rizzo M, et al. Which version of the geriatric depression scale is most useful in medical settings and nursing homes? Diagnostic validity meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:1066–1077. doi: 10.1097/jgp.0b013e3181f60f81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, et al. The Mini-Cog: A cognitive ‘vital signs’ measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:1021–1027. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<1021::aid-gps234>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haux R, Hein A, Kolb G, et al. Information and communication technologies for promoting and sustaining quality of life, health and self-sufficiency in ageing societies: Outcomes of the Lower Saxony Research Network Design of Environments for Ageing (GAL) Inform Health Soc Care. 2014;39:166–187. doi: 10.3109/17538157.2014.931849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermans E, van Schaik PM, Prins HA, et al. Outcome of colonic surgery in elderly patients with colon cancer. J Oncol. doi: 10.1155/2010/865908 [epub ahead of print on June 13, 2010]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Richards CH, Leitch FE, Horgan PG, et al. A systematic review of POSSUM and its related models as predictors of post-operative mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1511–1520. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tran Ba Loc P, du Montcel ST, Duron JJ, et al. Elderly POSSUM, a dedicated score for prediction of mortality and morbidity after major colorectal surgery in older patients. Br J Surg. 2010;97:396–403. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, et al. Development of an American College of Surgeons National Surgery Quality Improvement Program: Morbidity and mortality risk calculator for colorectal surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:1009–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:219–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1157–1165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Michaels M, et al. Delirium is independently associated with poor functional recovery after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:618–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN): NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Older Adult Oncology, Version 2.2016. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/senior.pdf

- 38.Caillet P, Laurent M, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Optimal management of elderly cancer patients: Usefulness of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1645–1660. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S57849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2595–2603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3457–3465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hurria A, Mohile S, Gajra A, et al. Validation of a prediction tool for chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2366–2371. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Besdine R, Boult C, Brangman S, et al. Caring for older Americans: The future of geriatric medicine. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:S245–S256. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Extermann M, Aapro M, Bernabei R, et al. Use of comprehensive geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: Recommendations from the task force on CGA of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;55:241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmer RM. Geriatric assessment. Med Clin North Am. 1999;83:1503–1523. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Magnuson A, Allore H, Cohen HJ, et al. Geriatric assessment with management in cancer care: Current evidence and potential mechanisms for future research. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karuturi M, Wong ML, Hsu T, et al. Understanding cognition in older patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dodson JA. Moving from disease-centered to patient goals-directed care for patients with multiple chronic conditions: Patient value-based care. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:9–10. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2015.0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nardi EA, Wolfson JA, Rosen ST, et al. Value, access, and cost of cancer care delivery at academic cancer centers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:837–847. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen HJ. A model for the shared care of elderly patients with cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:S300–S302. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02518.x. (suppl 2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Golden AG, Silverman MA, Issenberg SB. Addressing the shortage of geriatricians: What medical educators can learn from the nurse practitioner training model. Acad Med. 2015;90:1236–1240. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stahlke Wall S, Rawson K. The nurse practitioner role in oncology: Advancing patient care. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2016;43:489–496. doi: 10.1188/16.ONF.489-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]