Abstract

The Pseudomonas aeruginosa genome contains several different multidrug resistance (MDR) efflux pumps. Overproduction of these pumps reduces susceptibility to a variety of antibiotics. Some recently published works have analyzed the effect of the overproduction of MDR efflux pumps on bacterial virulence. Here we have studied the effect of overproduction of the efflux pumps MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, MexEF-OprN, and MexXY on type III secretion (T3S) in P. aeruginosa. The type III secretion system (T3SS) is used by P. aeruginosa to deliver toxins directly into the cytoplasm of the host cell. Our data indicate that overexpression of either MexCD-OprJ or MexEF-OprN is associated with the impairment of T3S in P. aeruginosa. No effect on overexpression of either MexAB-OprM or MexXY was detected. The observed defect in T3S was due to a lack of expression of genes belonging to the T3SS regulon. Transcription of this regulon is activated by ExsA in response to environmental signals. Overexpression of this transcriptional regulator complemented the defect in T3S observed in the MexCD-OprJ- and MexEF-OprN-overproducing strains. Taken together, these results suggest that overproduction of either MexCD-OprJ or MexEF-OprN is associated with a reduction in the transcription of the T3SS regulon due to the lack of expression of the exsA gene, encoding the master regulator of the system. The relevance of potential metabolic and quorum-sensing imbalances due to overexpression of MDR pumps associated with this phenotype is also discussed.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the leading pathogens involved in nosocomial infections (39). In addition, P. aeruginosa infection is the major cause of morbidity and mortality of cystic fibrosis patients (17) and has an increasing role in AIDS-associated infections (39). One of the reasons for the prevalence of P. aeruginosa in hospital settings might be its characteristic low susceptibility to antibiotics. This low susceptibility is mainly the consequence of the presence of several genes encoding multidrug resistance (MDR) efflux pumps in the genome of this bacterial species. Active MDR pumps have been found in P. aeruginosa strains associated with clinical or environmental habitats (3). Expression of MDR pumps is usually down-regulated. However, mutants overexpressing those pumps are easily selectable both in vitro (4, 26) and in vivo in clinical posttherapy isolates (22, 38, 51), thus contributing to acquired antibiotic resistance of this bacterial pathogen. Work from our laboratory and others, using simple models such as Caenorhabditis elegans (43) or Dictyostelium discoideum (8), has previously demonstrated that overproduction of P. aeruginosa MDR pumps might reduce bacterial fitness and virulence. P. aeruginosa virulence relies on the production of different factors such as siderophores, hemolysins, or toxic compounds such as pyocianin or cyanide, among others. The expression of several of these determinants is triggered by quorum-sensing (QS) signals (47). Since MDR pumps can extrude an ample range of molecules, efflux of QS signals by MDR pumps might be one of the reasons for the reduced virulence of P. aeruginosa strains overproducing such antibiotic resistance determinants. Indeed, some MDR pumps, such as MexAB-OprM (34), MexEF-OprN (24), or MexGHI-OpdM (1), can extrude QS signals, thus reducing the expression of P. aeruginosa quorum-sensing-regulated virulence determinants. However, P. aeruginosa virulence does not rely only on quorum-sensing-regulated virulence determinants. Upon contact with its target mammalian cell, P. aeruginosa injects different exoproteins directly into the cell cytoplasm through a needle-like structure. This secretion mechanism has been termed the type III secretion system (T3SS) and is well conserved in different bacterial pathogens (21). T3SS effectors interfere with different signal pathways in the host eukaryotic cells and have a prominent role in the bacterial pathogenic process. In the case of P. aeruginosa (49), it has been described that exoenzyme S (ExoS) and exoenzyme T (ExoT) have ADP-ribosylating activity towards proteins of the Ras family (31). Exoenzyme Y (ExoY) is an adenylate cyclase (50), and exoenzyme U (ExoU) displays lipase activity in vitro (44). Expression of these genes is coordinately regulated by the activator protein ExsA (20, 48), the expression of exsA itself being triggered by ExsA in response to different environmental signals, including low calcium and direct contact with tissue culture cells.

Studies on the mechanisms of bacterial virulence have been traditionally done with wild-type antibiotic-susceptible bacterial strains. However, antibiotic usage has increased the incidence of antibiotic-resistant strains in pathogenic bacterial populations, and therefore the understanding of the relationship between antibiotic resistance and bacterial virulence stands as an important issue (5, 27) that has been addressed in just a few cases. As stated above, our group (43) and others (16, 24) have previously demonstrated that P. aeruginosa strains overproducing MDR pumps are defective in the production of quorum-sensing-regulated virulence determinants. To further investigate the relationship between virulence and antibiotic resistance in bacterial pathogens, in the present work we have studied the effect of overproducing the MDR pumps MexAB-OprM (37), MexCD-OprJ (36), MexEF-OprN (25), and MexXY (32) on type III secretion (T3S) in P. aeruginosa. Our results show that overexpression of MexEF-OprN and MexCD-OprJ is associated with a reduction in the transcription of the T3SS genes. In contrast, overexpression of either MexAB-OprM or MexXY did not produce any detectable effect on T3S.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, growth conditions, and DNA methods.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli and P. aeruginosa strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (6) or on LB agar plates at 37°C. LB broth containing 5 mM EGTA and 20 mM MgCl2 was used for analyzing type III secretion (12). Antibiotic susceptibilities were tested in Mueller-Hinton agar (6) plates containing different concentrations of antibiotics and with standard inocula of 104 cells/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| CC118(λpir) | CC118 lysogenized with λpir phage | 18 |

| TG1 | Host for DNA manipulations | 42 |

| HB101 | supE44 hsdS20(rB mB) recA13 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 galK2 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 | 42 |

| P. aeruginosa strains | ||

| PAO1-V | Clinical isolate | V. de Lorenzo |

| JFL30 | MexAB-OprM-hyperexpressing MDR mutant from PAO1-V | Present work |

| JFL28 | MexCD-OprJ-hyperexpressing MDR mutant from PAO1-V | Present work |

| JFL10 | MexXY-hyperexpressing MDR mutant from PAO1-V | Present work |

| PAO1-L | Clinical isolate | A. Lazdunski |

| JFL05 | MexEF-OprN-hyperexpressing MDR mutant from PAO1-L | Present work |

| R-1 | lasR mutant derived from PAO1-L | A. Lazdunski |

| PT462 | rhlR mutant derived from PAO1-L | T. Kohler |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEMT-Easy | Apr; vector for cloning of PCR products | Promega |

| pVLT35 | Smr; RSF1010-lacIq/Ptac hybrid broad-host-range expression vector, multiple cloning site of pUC18 | 14 |

| pJF03 | pVLT35 derivative plasmid that carries the wild-type exsA gene from P. aeruginosa PAO1 | Present work |

| pRK600 | CmroriColE1 RK2− Tra+, helper plasmid in triparental mating | 23 |

To analyze the mutations present in the transcriptional regulators of MDR pumps, the mexR, nfxB, mexT, and mexZ genes were PCR amplified with, respectively, the following pairs of primers: mexR-1 (5′-CGCCATGGCCCATATTGAG-3′) with mexR-2 (5′-GGCATTCGCCAGTAAGCGG-3′), nfxB-1 (5′-CGATCCTTCCTATTGCACG-3′) with nfxB-2 (5′-GCCAAGTGCCAGTATCG-3′), mexT-1 (5′-CGGTTGCAGCCTCTAGCC-3′) with mexT-2 (5′-CGATTTTCCCGTTGCGACG-3′), and mexZ-1 (5′-AGCGGCGCGACAGTAGCATA-3′) with mexZ-2 (5′-CCGAGGACCAGCGCAGGC-3′). The PCR mixture, containing a 0.5 μM concentration of each primer, 100 ng of chromosomal DNA, and DNA polymerase gel form (Biotools) was heated at 94°C for 3 min. This was followed by 32 cycles of 30 s at 94°C; 30 s at 53°C (nfxB), 55°C (mexT), 58°C (mexR), or 60°C (mexZ); and 60s at 72°C, with a final 10-min extension step at 72°C. The products of two independent PCRs were sequenced (both strands) for each of the genes.

Analysis of type III secreted proteins.

T3S was induced as previously described (12). In brief, P. aeruginosa was grown in LB broth for 16 h at 37°C with agitation. Cultures were then diluted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.1 in calcium-depleted medium (induction condition) containing 5 mM EGTA and 20 mM MgCl2 and grown again for 4 h. After centrifugation, 40 μl of culture supernatants (from cultures containing equivalent numbers of cells) were analyzed directly by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and the proteins were visualized with the PlusOne silver staining kit (Amersham Biosciences).

In-gel digestion of proteins and sample preparation for MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

Digestion of proteins in excised gel plugs (in gel) was performed as described previously (45) with minor modifications. The excised gel plugs were washed in water and acetonitrile prior to reduction with 10 mM dithiothreitol and alkylation with 55 mM iodoacetamide and thereafter were dried by vacuum centrifugation. The dried gel pieces were incubated with modified porcine trypsin (10 ng/μl, sequencing grade; Promega, Madison, Wis.) in 50 mM NH4HCO3 for 40 min, after which the supernatant was removed, 20 to 40 μl of 50 mM NH4HCO3 was added, and the digestion was continued at 37°C for 12 h. A 0.5-μl aliquot of the digestion supernatant was deposited onto the matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight (MALDI) probe (AnchorChip; Bruker Daltonics) and allowed to dry at room temperature. Then, 0.5 μl of matrix solution (saturated α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 30% [vol/vol] aqueous acetonitrile and 0.1% [vol/vol] trifluoroacetic acid) was added and again allowed to dry at room temperature.

Samples were measured on a Reflex III MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker-Franzen Analytic GmbH, Bremen, Germany) equipped with the SCOUT source in positive-ion reflector mode. The ion acceleration voltage was 20 kV. The equipment was first externally calibrated by employing protonated mass signals from a peptide mixture covering the 1,000- to 4,000-m/z range, and thereafter every spectrum was internally calibrated by using signals arising from trypsin autoproteolysis.

RT-PCR.

Bacterial cells growing in conditions that induce T3S (see above) were collected, spun down at 4°C, and frozen in dry ice. Total RNA was extracted with the phenol-guanidine thiocyanate mix Tri Reagent LS (Molecular Research Center, Inc.). Residual DNA was removed by treatment with the DNA-Free kit (Ambion). Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) assays were performed with Ready-To-Go RT-PCR beads (Amersham Biosciences) as indicated by the manufacturer. The amplifications were performed with primers specific for the selected genes (listed in Table 2) and two serial 10-fold dilutions of the RNA (1 and 0.1 μg). To ascertain that no residual DNA was present in the RNA preparations, PCRs were performed with the same primers and overall conditions, except that no reverse transcriptase was added. Expression of the rpsL gene was measured as an internal control that ensured that equal amounts of RNA were used in all of the RT-PCRs done. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 42°C, followed by 10 min at 95°C. This was followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 95°C; 30 s at 55°C (for mexC and mexE), 57°C (for mexA), 60°C (for exoT, rpsL, exsA, exsD, and mexX), 63°C (for aceB and exoS), or 65°C (for pcrV); and 1 min at 72°C, prior to the final 7-min elongation at 72°C.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for RT-PCR

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| mexA-1 | 5′-CCTGCTGGTCGCGATTTCGG-3′ |

| mexA-2 | 5′-CCAGCAGCTTGTAGCGCTGG-3′ |

| mexC-1 | 5′-TTGGCTATGGCCATCGCGTT-3′ |

| mexC-2 | 5′-ATCGAAGTCCTGCTGGCTGA-3′ |

| mexE-1 | 5′-ATCCCACTTCTCCTGGCGCT-3′ |

| mexE-2 | 5′-GGTCGCCTTTCTTCACCAGT-3′ |

| mexX-1 | 5′-GCGATGCGGATTGCGGAACA-3′ |

| mexX-2 | 5′-TGGTCGCCCTATTCCTGCTG-3′ |

| rpsL-1 | 5′-GCAACTATCAACCAGCTG-3′ |

| rpsL-2 | 5′-GCTGTGCTCTTGCAGGTTGTG-3′ |

| exsA-1 | 5′-CGCTGCTGATGTCGGTCCT-3′ |

| exsA-2 | 5′-GCGTGCTGATGTCGGTCCT-3′ |

| exoT-1 | 5′-CATCGAGTGGCTGGGCAAAC-3′ |

| exoT-2 | 5′-TCTCCGCTGTCAAAGTCGCC-3′ |

| exoS-1 | 5′-AAGCGGTAGAGAGCGAGGTC-3′ |

| exoS-2 | 5′-GCCCTCTTCCACTGCGTTGA-3′ |

| pcrV-1 | 5′-CAAGCAGGGCATCAGGATCG-3′ |

| pcrV-2 | 5′-TGTCGTTGAGCAGGGTGGTC-3′ |

| exsD-1 | 5′-GGAGCAGGAAGACGATAAGC-3′ |

| exsD-2 | 5′-CCCAGTTCGGAGCACCAGC-3′ |

| aceB-1 | 5′-CTCTCGACCACCTGCTCCTG-3′ |

| aceB-2 | 5′-GCCGAAACACCAACTGGACCG-3′ |

Cloning of exsA.

The exsA gene was amplified by using the primers exsA-3 (5′-ATAAAATCGACTCCGTGCTCA-3′) and exsA-4 (5′-TTCTACTCATGCAGCCGCTA-3′). The PCR mixture, containing a 0.5 μM concentration of each primer, 100 ng of chromosomal DNA, and DNA polymerase gel form (Biotools), was heated at 94°C for 3 min; this was followed by 32 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 60s at 72°C, with a final 10-min extension step at 72°C. The PCR product obtained was purified with the Qiaquick purification PCR kit (Qiagen), cloned in the pGEMT-Easy vector (Promega), and recovered as an EcoRI fragment. The EcoRI fragment containing the exsA gene was cloned under the control of the Ptac promoter in the EcoRI site of the plasmid pVLT35, rendering plasmid pJF03. The insert was sequenced to ensure that it did not contain any mutation, and its orientation in the vector was confirmed by PCR with the primers Ptac (5′-GACAATTAATCATCGGCTCG-3′) and exsA-2. Plasmid pJF03 was then introduced in P. aeruginosa strains JFL28 and JFL05 by conjugation in triparental matings as described previously (15), using plasmid pRK600 as a helper for the transfer functions. Exconjugants were selected in minimal salts M9 (6) agar plates containing citrate (0.2%, wt/vol) and streptomycin (50 μg/ml). Expression of exsA from Ptac was induced with 3 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside).

Cytotoxicity assays.

The J774 macrophage cell line (10) was grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco). The macrophages were seeded in 96-well culture plates 20 h before infection at 104 cells/well. On the day of the experiment, the cells were carefully washed and infected with the P. aeruginosa strains at a multiplicity of infection of 50. Eight wells were infected with each bacterial strain. After 360 min of infection, cytotoxicity was evaluated with a cytotoxicity detection kit (LDH) in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer (Roche). One hundred percent cytotoxicity was estimated by lysing noninfected cells with 2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. Means and standard deviations were calculated with Microsoft Excel.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Obtainment of P. aeruginosa strains overexpressing MDR pumps.

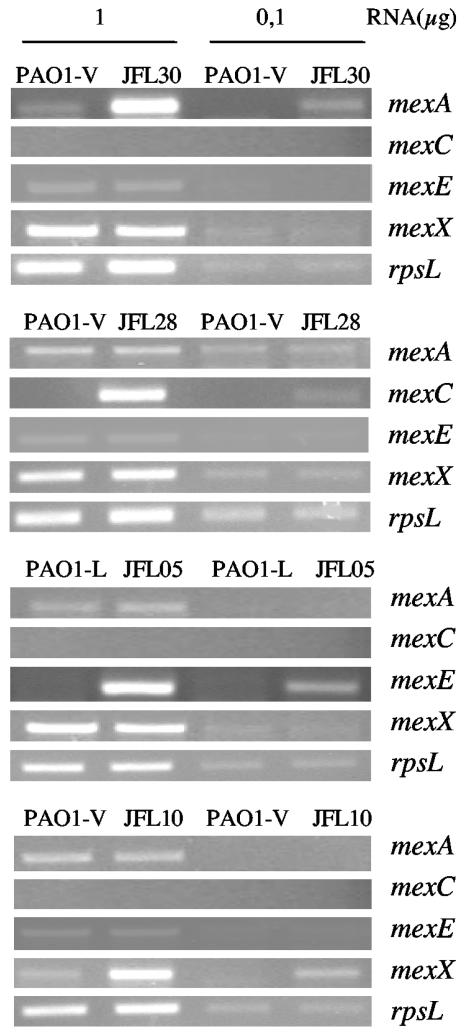

To analyze the effect of overexpression of MDR pumps on bacterial physiology, we needed to mimic as much as possible the type of mutants encountered in clinical settings after antibiotic treatment. To that end, single-step mutants hyperexpressing MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, MexEF-OprN, and MexXY were selected on antibiotic selective plates. Two wild-type P. aeruginosa PAO1 strains were used, namely, PAO1-L (from the laboratory of Andrée Lazdunsky) and PAO1-V (from the laboratory of Víctor de Lorenzo). In the course of our studies, we realized that strain PAO1-V has an internal deletion in the mexT gene, leading to a truncated version of MexT, the transcriptional activator of mexEF-oprN (our unpublished results). Due to this deletion, mexEF-oprN cannot be up-regulated in the PAO1-V strain. It has been described that mexEF-oprN overproduction might interfere with analysis of the effect of MDR pumps on the P. aeruginosa QS response (24). Therefore, the genetic background of PAO1-V is suitable for avoiding those problems and was used for obtaining mutants that overexpressed MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexXY. The PAO1-L strain was used for obtaining the MexEF-OprN-overexpressing mutant. Strain JFL30 was selected with 20 μg of tetracycline per ml (4). As shown in Table 3, this mutant strain has a lower susceptibility to quinolones, aztreonam, and cefpirome but not to imipenem, a phenotype that is compatible with overexpression of MexAB-OprM. The mutant strain JFL28 was selected with 8 μg of norfloxacin per ml and 500 μg of erythromycin per ml (26) and has a decreased susceptibility to cefpirome and quinolones but not to aztreonam (Table 3). This phenotype is compatible with MexCD-OprJ overexpression. The mutant strain JFL05 was selected with 600 μg of chloramphenicol per ml (24) and was less susceptible to imipenem, chloramphenicol, and quinolones (Table 3), a phenotype compatible with MexEF-OprN overexpression. Finally, strain JFL10 was selected on Mueller-Hinton agar plates containing 4 μg of gentamicin per ml and 1 μg of ofloxacin per ml (29). This mutant strain was less susceptible to quinolones and gentamicin (Table 3), a phenotype compatible with MexXY overproduction. The overexpression of the corresponding MDR system was confirmed by semiquantitative RT-PCR with primers specific for the mexA, mexC, mexE, and mexX genes as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 1, each of the mutant strains overexpressed just the MDR determinant predicted to be hyperexpressed on the basis of the aforementioned phenotypes of antibiotic susceptibility. To further characterize these mutant strains, the local regulator of each MDR pump was PCR amplified and sequenced. Consistent with the observed phenotypes, mexR (repressor of mexAB-oprM) from strain JFL30 carries a 1-bp deletion at the position 81, resulting in an out-of-frame sequence. nfxB (repressor of mexCD-oprJ) from strain JFL28 has a 1-bp deletion at the position 47, resulting in an out-of-frame sequence. mexT (activator of mexEF-oprN) from strain JFL05 contains an 8-bp deletion at the position 104 that renders an active form of MexT (28). Mutations in the mexZ gene (local repressor of mexXY-oprM) are not frequently found in MexXY-OprM-overproducing mutants (46). In agreement with this, we did not detect mutations in mexZ in strain JFL10.

TABLE 3.

Antibiotic susceptibilities of P. aeruginosa strains

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP | GEN | CHL | IMI | AZT | CEF | |

| PAO1-V | 0.25 | 2 | 64 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| JLF30 | 1 | 2 | 512 | 2 | 32 | 16 |

| JFL28 | 4 | 2 | 128 | 1 | 1 | 32 |

| JFL10 | 4 | 8 | 256 | 2 | 4 | 32 |

| PAO1-L | 0.25 | 2 | 64 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| JFL05 | 1 | 2 | 1,024 | 4 | 4 | 16 |

CIP, ciprofloxacin; GEN, gentamicin; CHL, chloramphenicol; IMI, Imipenem; AZT, aztreonam; CEF, cefpirome.

FIG. 1.

Expression of MDR genes by single-step multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa mutants. The amounts of mRNAs corresponding to the first genes (mexA, mexE, mexC, or mexX) of the four best-characterized MDR pumps of P. aeruginosa were measured by RT-PCR in strains PAO1-L (wild type) and its derivative JFL05 and in PAO1-V (wild type) and its derivatives JFL30, JFL28, and JFL10. Different amounts of RNA (1 or 0.1 μg) were used. Expression of the rpsL gene was used as a control to ensure that the amounts of RNAs from wild-type and mutant strains used for the RT-PCR assays were comparable.

Effect of overexpression of MDR pumps on type III secretion in P. aeruginosa.

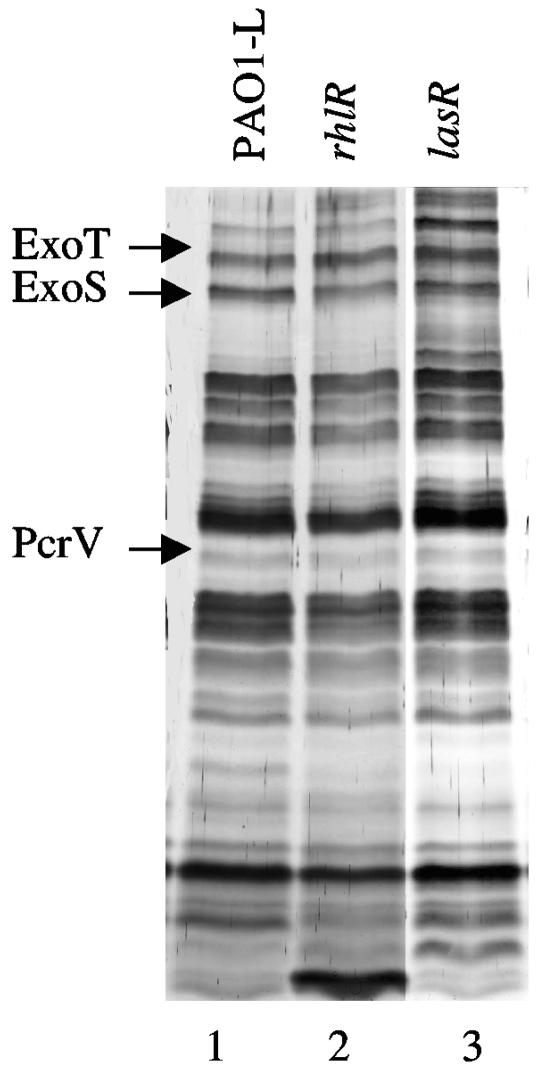

Bacteria were grown under conditions that stimulate T3S (12), and the proteins secreted by the wild-type and the MDR mutant strains were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. A few changes could be observed upon comparison of the SDS-PAGE profiles. The experiment was repeated three times, and the bands whose intensities consistently changed in the three experiments were analyzed. The bands of interest were excised from the gel and digested with trypsin, and the masses of the generated peptides were determined by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to obtain the protein's peptide mass fingerprint. The peptide fingerprint obtained for each band was matched against those derived from a virtual digestion of each protein encoded by P. aeruginosa PAO1 (www.pseudomonas.com). This approach allowed us to find that the bands with the most relevant modifications in intensity corresponded to the T3S proteins ExoT, ExoS, and PcrV. As shown in Fig. 2, expression of these three proteins was significantly reduced in mutant strains JFL05 (overexpresses MexEF-OprN) and JFL28 (overexpresses MexCD-OprJ). This reduction was not observed in the strains overexpressing MexAB-OprM or MexXY. Since strain PAO-V, from which JFL28 was obtained, has a deletion in mexT (see above), the effect on T3S of MexCD-OprJ overexpression cannot be attributed to an undesired overexpression of MexEF-OprN.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of the proteins secreted by P. aeruginosa strains that overproduce MDR efflux pumps. The proteins secreted by the indicated strains while growing exponentially under conditions that stimulate T3S (see Materials and Methods) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Lane 1, wild-type strain PAO1-V; lane 2, single-step mutant overexpressing MexAB-OprM; lane 3, single-step mutant overexpressing MexCD-OprJ; lane 4, single-step mutant overexpressing MexXY-OprM; lane 5, wild-type strain PAO1-L; lane 6, single-step mutant overexpressing MexEF-OprN. Proteins expressed at lower levels in the strains that overproduce MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN, identified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (see text), are indicated with arrows.

Type III secretion is not affected by quorum sensing at the exponential growth phase.

It has been described previously that overexpression of the MDR efflux pumps MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexEF-OprN reduces the expression of QS-regulated virulence factors (16, 24, 43). In fact, MexAB-OprM (34) and MexEF-OprN (24) can extrude QS signals, thus contributing to regulate QS homeostasis. Although the supernatants used for measuring T3S were obtained from exponential-phase cultures in which QS signaling is unlikely, it might still be conceivable that the effect of MDR efflux pump overproduction in T3S could be mediated by quorum-sensing. In fact, a recent work has stated that T3S is down-regulated in P. aeruginosa biofilms and that the expression of exoS in stationary phase might be regulated by quorum sensing (19). QS in P. aeruginosa is mediated mainly by two different, yet interconnected, circuits. One is the las pathway, controlled by the LasR transcriptional regulator (33). The other is the rhl pathway, which is transcriptionally regulated by RhlR (7). Both systems are connected through a third intercellular signaling element, the P. aeruginosa quinolone signal (35). We analyzed proteins secreted under conditions that stimulate T3S in lasR and rhlR mutant strains that are defective in the las and rhl QS pathways, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3, no differences were detected in the bands corresponding to ExoT, ExoS, and PcrV when comparing wild-type with QS mutant strains. This indicates that the defect in T3S detected in the MexEF-OprN and MexCD-OprJ mutants cannot be attributed to a putative defect in QS signaling in these strains.

FIG. 3.

Proteins secreted by strains having an impaired quorum-sensing signaling pathway. The effect of mutations in QS control on the profile of secreted proteins was evaluated by using P. aeruginosa mutants with mutations in the rhl and las QS pathways. Lane 1, PAO1-L (wild-type strain); lane 2, R-1 (rhlR derivative of PAO1-L); lane 3, PT462 (lasR derivative of PAO1-L). The arrows indicate the positions of the proteins whose expression decreased upon overexpression of the MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN MDR pumps.

Overexpression of MDR pumps challenges type III secretion at the transcriptional level.

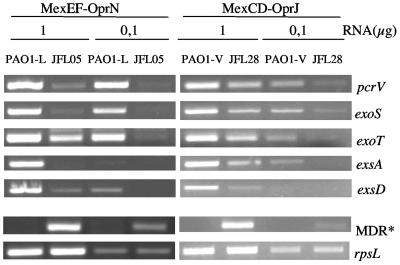

The defect in T3S observed in the mutant strains overproducing MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN could be due either to a specific reduction in the secretion of some proteins or to a reduced transcription of the genes encoding T3S proteins. To analyze this possibility, RNAs were obtained from strains PAO1-V (wild type), JFL28 (overexpressing MexCD-OprJ), PAO1-L (wild type), and JFL05 (overexpressing MexEF-OprN) grown under conditions that stimulate T3S, and the expression of genes encoding T3S factors was measured by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Expression of rpsL (constitutive expression) (46) and either mexC or mexE (overexpressed) was also measured as a control. As shown in Fig. 4, expression of the genes exoT, exoS, and pcrV, encoding T3S proteins, was clearly lower in the strain overproducing MexEF-OprN than in its wild-type isogenic parental strain. Expression of these genes was also decreased, although to a lesser extent, in the strain overexpressing MexCD-OprJ. Control reactions performed in parallel with the same RNA preparations showed that expression of the rpsL gene was similar in all cases and that expression of the MDR genes was increased in the mutant strains (Fig. 4). Therefore, the results presented suggest that the effect on T3S associated with MDR overexpression in P. aeruginosa occurs at the transcriptional level. As stated above, expression of the T3S regulon is triggered by the ExsA activator. Thus, we compared exsA transcription in the strains overexpressing MexCD-OprJ or MexEF-OprN and their isogenic wild-type strains. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analyses (Fig. 3) showed that exsA expression was lower in the strains overexpressing the MDR pumps than in the wild-type strains. This suggests that the strains overexpressing MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN are unable to trigger esxA expression in response to the signal that activates T3S.

FIG. 4.

Expression of T3SS genes by strains that overproduce MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN. The amounts of mRNAs corresponding to different genes of the T3SS regulon (exoT, exoS, pcrV, exsA, or exsD) were measured by RT-PCR in strains PAO1-L (wild type), JFL05 (derivative of PAO1-L overexpressing MexEF-OprN), PAO1-V (wild-type), and JFL28 (derivative of PAO1-V overexpressing MexCD-OprJ). Different amounts of RNA (1 or 0.1 μg) were used. Expression of the rpsL gene was used as a control to ensure that the amounts of RNAs from wild-type and mutant strains used for the RT-PCR assays were comparable. Expression of the first gene of each MDR pump operon (either mexA or mexE) was also analyzed by RT-PCR (indicated as MDR*).

Expression of ExsA from a heterologous promoter suppresses the effect of MDR overexpression on type III secretion.

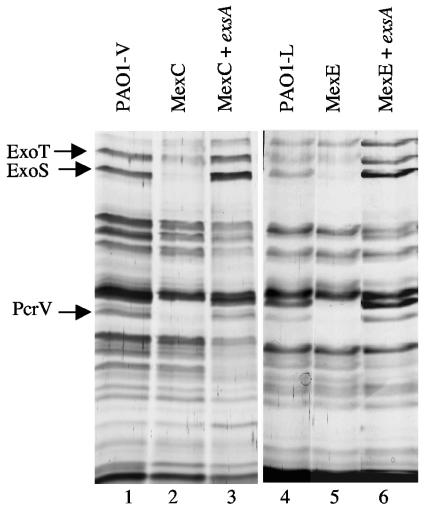

Our data indicate that the defect in secretion detected in the P. aeruginosa strains overexpressing the MexCD-OprJ or MexCD-OprN pump might be due to a low-level expression of exsA compared to that in the wild-type parental strains. To confirm this possibility, the exsA gene was PCR amplified and cloned in the vector pVLT35 to render pJF03. In this plasmid, expression of the cloned exsA gene is under control of the heterologous Ptac promoter. The strains overexpressing MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN were transformed with the exsA expression plasmid pJF03, and T3S was compared to that in the parental strains. As shown in Fig. 5, secretion of ExoT, ExoS, and PcrV was restored to the normal levels in the mutant strains when exsA was expressed form the Ptac promoter. This result strongly supports the hypothesis that the lack of exsA expression is responsible for the effect of MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN on T3S in P. aeruginosa. To ensure that this defect was not due to secondary mutations present in exsA, the genes from strains JFL05 and JFL28 were PCR cloned and sequenced. No mutation was found in the exsA sequence in either of the strains. T3S is triggered in vivo by contact with the target mammalian cell and in vitro by growing bacteria in media with low calcium and high magnesium levels. In both cases ExsA is the master transcriptional activator of the system. Nevertheless, the mechanism by which the extracellular calcium concentration (or the contact with host cell) is translated into the activation of exsA transcription is unknown. It has been described that ExsD, a negative regulator of the T3S regulon, blocks the activity of ExsA (30). We thus measured exsD expression to determine whether it is increased in the MDR mutants compared to the wild-type strains, causing the low exsA expression. As shown in Fig. 4, exsD is expressed at lower levels in the MDR mutants than in the wild-type strains. Thus, a role of this protein in the observed decrease in T3S seems unlikely.

FIG. 5.

Effect of ExsA expression on the proteins secreted by strains overexpressing the MDR pumps MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN. The proteins secreted by cells grown under conditions that stimulate T3S were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Lane 1, PAO1-V (wild type); lane 2, JFL28 (derivative of PAO1-V overexpressing MexCD-OprJ); lane 3, JFL28 containing plasmid pJF03 (overexpresses exsA) grown in the presence of 3 mM IPTG; lane 4, PAO1-L (wild type); lane 5, JFL05 (derivative of PAO1-L overexpressing MexEF-OprN); lane 6, JFL05 containing plasmid pJF03 (overexpresses exsA) grown in the presence of 3 mM IPTG. The bands corresponding to the T3S proteins ExoT, ExoS, and PcrV are indicated.

MDR overexpression is associated with a reduction of P. aeruginosa cytotoxicity.

T3S has a relevant role in P. aeruginosa cytotoxicity (9, 12, 13) To validate our in vitro data with a physiologically relevant model, we measured the cytotoxicities of the MexCD-OprJ- and MexEF-OprN-overproducing mutants in comparison with the wild-type strains by using the macrophage cell line J774 (10). Under the conditions tested, strain PAO1-V produced 78% ± 7% cell lysis and the MexCD-OprJ-overproducing isogenic mutant strain JFL28 was clearly less cytotoxic (39% ± 6%). Similarly, the MexEF-OprN-overproducing strain JFL05 was less cytotoxic (7% ± 3%) than its isogenic wild-type strain PAO1-L (44% ± 4%). Expression of exsA from a heterologous promoter (see above) in strains JFL28 and JFL05 increased cytotoxicity to 91% ± 9% and 83% ± 12%, respectively, indicating that exsA can complement both in vitro (see above) and in vivo the defects on T3S and cytotoxicity associated with overexpression of the MexCD-OprJ or MexEF-OprN efflux pump. Clinical P. aeruginosa isolates are either cytotoxic or cytoinvasive. However, it has been found that noncytotoxic cystic fibrosis isolates can be converted to cytotoxic isolates simply by expressing the exsA gene from a heterologous promoter (10). Since mutants overproducing MDR pumps can be selected by antibiotic treatment, it would be interesting to know whether there is an association between MDR overproduction and reduced cytotoxicity in P. aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolates.

Metabolic imbalance and T3S in P. aeruginosa MDR-overproducing mutants.

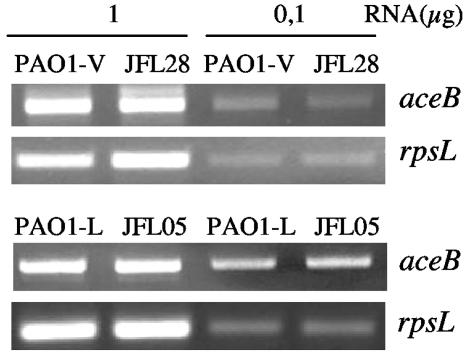

Two recent articles have reported that P. aeruginosa T3S can be affected by mutations in metabolic genes. A search of new genes involved in T3SS-dependent cytotoxicity toward human polymorphonuclear neutrophils demonstrated that the T3SS requires an intact aceAB operon (11), which encodes the E1 and E2 subunits of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). Those authors suggested that the most likely explanation is that the E1 or E2 subunit of PDH could play a role in regulation of T3S gene expression. A role of PDH in transcriptional regulation was first demonstrated in Azotobacter vinelandii, in which the E1 subunit of PDH is an activator of NADPH:ferredoxin reductase transcription in response to oxidative stress (40). Our group has previously shown that overexpression of MDR pumps can challenge bacterial metabolism (2). It might thus be possible that aceAB expression could be altered in the MexCD-OprJ- and MexEF-OprN-overproducing mutants, and these changes could be the reason for the lack of expression of T3SS in them. We have compared the expression of aceB in the MDR mutants and wild-type parental strains by semiquantitative RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 6, the levels of aceAB RNAs were the same in the wild-type strains and in the strains overproducing MexCD-OprJ or MexEF-OprN. Thus, the defect in T3SS transcription is not due to a reduced expression of aceAB in these mutant strains.

FIG. 6.

Expression of the aceAB operon in strains that overproduce MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN. The expression of the aceB gene in strains PAO1-V (wild type), JFL28 (derivative of PAO1-V overexpressing MexCD-OprJ), PAO1-L (wild type), and JFL05 (derivative of PAO1-L overexpressing MexEF-OprN) was measured by RT-PCR. Two different amounts of RNA (1 or 0.1 μg) were used. Expression of the rpsL gene was used as a control to ensure that the amounts of RNAs from the strains compared were similar.

A different search for mutations affecting T3S in P. aeruginosa showed that overproduction of hutT, a gene encoding a histidine transporter, is associated with a decrease in the expression of the T3S gene exoS (41). The mutant strain was also impaired in growth at the expense of histidine as the sole carbon source. We have determined that the growth of the strains overproducing MexCD-OprJ or MexEF-OprN at the expense of histidine is not impaired (data not shown). Consequently, a role of hutT in the defect of T3SS transcription in our mutant strains is unlikely.

In summary, the results presented here indicate that the transcriptional activation of the T3S regulon is reduced in mutants overexpressing either the MexCD-OprJ or MexEF-OprN MDR pump, making these mutants less cytotoxic. This phenotype is associated with low expression of exsA under conditions that trigger T3S. Since MDR pumps can extrude a wide range of compounds belonging to different structural families, it might be possible that MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN are extruding the intracellular signal that allows ExsA to activate transcription of the T3SS genes. Identification of this signal has so far remained elusive. Alternatively, T3S impairment in these mutant strains could be due to the metabolic challenge associated with MDR overexpression or to a direct effect of the MDR regulators.

The results presented here, together with the observed interference of the overexpression of MDR pumps in quorum-sensing regulation (16, 24, 43), emphasizes the importance of a proper regulation of these efflux systems so as not to compromise P. aeruginosa fitness and virulence.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrée Lazdunsky, Víctor de Lorenzo, and Thilo Köhler for providing P. aeruginosa strains. We are grateful to Patricia Sánchez for help with sequence analysis.

This work has been supported by grants BIO2001-1081 and BMC2003-00063 from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology (MCYT) and by grant QLRT-2000-01339 from the EU. J.F.L. was the recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from the MCYT.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aendekerk, S., B. Ghysels, P. Cornelis, and C. Baysse. 2002. Characterization of a new efflux pump, MexGHI-OpmD, from Pseudomonas aeruginosa that confers resistance to vanadium. Microbiology 148:2371-2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso, A., G. Morales, R. Escalante, E. Campanario, L. Sastre, and J. L. Martinez. 2004. Overexpression of the multidrug efflux pump SmeDEF impairs Stenotrophomonas maltophilia physiology. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:432-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso, A., F. Rojo, and J. L. Martinez. 1999. Environmental and clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa show pathogenic and biodegradative properties irrespective of their origin. Environ. Microbiol. 1:421-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alonso, A., E. Campanario, and J. L. Martinez. 1999. Emergence of multidrug-resistant mutants is increased under antibiotic selective pressure in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 145:2857-2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson, D. I., and B. R. Levin. 1999. The biological cost of antibiotic resistance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:489-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atlas, R. M. 1993. Handbook of microbiological media. CRC Press, Inc., London, United Kingdom.

- 7.Brint, J. M., and D. E. Ohman. 1995. Synthesis of multiple exoproducts in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is under the control of RhlR-RhlI, another set of regulators in strain PAO1 with homology to the autoinducer-responsive LuxR-LuxI family. J. Bacteriol. 177:7155-7163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cosson, P., L. Zulianello, O. Join-Lambert, F. Faurisson, L. Gebbie, M. Benghezal, D. C. Van, L. K. Curty, and T. Kohler. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence analyzed in a Dictyostelium discoideum host system. J. Bacteriol. 184:3027-3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dacheux, D., I. Attree, C. Schneider, and B. Toussaint. 1999. Cell death of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils induced by a Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolate requires a functional type III secretion system. Infect. Immun. 67:6164-6167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dacheux, D., I. Attree, and B. Toussaint. 2001. Expression of ExsA in trans confers type III secretion system-dependent cytotoxicity on noncytotoxic Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolates. Infect. Immun. 69:538-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dacheux, D., O. Epaulard, A. De Groot, B. Guery, R. Leberre, I. Attree, B. Polack, and B. Toussaint. 2002. Activation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system requires an intact pyruvate dehydrogenase aceAB operon. Infect. Immun. 70:3973-3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dacheux, D., J. Goure, J. Chabert, Y. Usson, and I. Attree. 2001. Pore-forming activity of type III system-secreted proteins leads to oncosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 40:76-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dacheux, D., B. Toussaint, M. Richard, G. Brochier, J. Croize, and I. Attree. 2000. Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolates induce rapid, type III secretion-dependent, but ExoU-independent, oncosis of macrophages and polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 68:2916-2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Lorenzo, V., L. Eltis, B. Kessler, and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Analysis of Pseudomonas gene products using lacIq/Ptrp-lac plasmids and transposons that confer conditional phenotypes. Gene 123:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Lorenzo, V., and K. N. Timmis. 1994. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in gram-negative bacteria with Tn5- and Tn10-derived minitransposons. Methods Enzymol. 235:386-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans, K., L. Passador, R. Srikumar, E. Tsang, J. Nezezon, and K. Poole. 1998. Influence of the MexAB-OprM multidrug efflux system on quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 180:5443-5447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Govan, J. R., and V. Deretic. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol. Rev. 60:539-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrero, M., V. de Lorenzo, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6557-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogardt, M., M. Roeder, A. M. Schreff, L. Eberl, and J. Heesemann. 2004. Expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoS is controlled by quorum sensing and RpoS. Microbiology 150:843-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hovey, A. K., and D. W. Frank. 1995. Analyses of the DNA-binding and transcriptional activation properties of ExsA, the transcriptional activator of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S regulon. J. Bacteriol. 177:4427-4436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hueck, C. J. 1998. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:379-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jalal, S., O. Ciofu, N. Hoiby, N. Gotoh, and B. Wretlind. 2000. Molecular mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:710-712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler, B., V. de Lorenzo, and K. N. Timmis. 1992. A general system to integrate lacZ fusions into the chromosomes of gram-negative eubacteria: regulation of the Pm promoter of the TOL plasmid studied with all controlling elements in monocopy. Mol. Gen. Genet. 233:293-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohler, T., C. van Delden, L. K. Curty, M. M. Hamzehpour, and J. C. Pechere. 2001. Overexpression of the MexEF-OprN multidrug efflux system affects cell-to-cell signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 183:5213-5222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohler, T., M. Michea-Hamzehpour, U. Henze, N. Gotoh, L. K. Curty, and J. C. Pechere. 1997. Characterization of MexE-MexF-OprN, a positively regulated multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 23:345-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohler, T., M. Michea-Hamzehpour, P. Plesiat, A. L. Kahr, and J. C. Pechere. 1997. Differential selection of multidrug efflux systems by quinolones in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2540-2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez, J. L., and F. Baquero. 2002. Interactions among strategies associated with bacterial infection: pathogenicity, epidemicity, and antibiotic resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:647-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maseda, H., K. Saito, A. Nakajima, and T. Nakae. 2000. Variation of the mexT gene, a regulator of the MexEF-OprN efflux pump expression in wild-type strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 192:107-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masuda, N., E. Sakagawa, S. Ohya, N. Gotoh, H. Tsujimoto, and T. Nishino. 2000. Contribution of the MexX-MexY-OprM efflux system to intrinsic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2242-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCaw, M. L., G. L. Lykken, P. K. Singh, and T. L. Yahr. 2002. ExsD is a negative regulator of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion regulon. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1123-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGuffie, E. M., D. W. Frank, T. S. Vincent, and J. C. Olson. 1998. Modification of Ras in eukaryotic cells by Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S. Infect. Immun. 66:2607-2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mine, T., Y. Morita, A. Kataoka, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 1999. Expression in Escherichia coli of a new multidrug efflux pump, MexXY, from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:415-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Passador, L., J. M. Cook, M. J. Gambello, L. Rust, and B. H. Iglewski. 1993. Expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes requires cell-to-cell communication. Science 260:1127-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearson, J. P., C. Van Delden, and B. H. Iglewski. 1999. Active efflux and diffusion are involved in transport of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cell-to-cell signals. J. Bacteriol. 181:1203-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pesci, E. C., J. B. J. Milbank, J. P. Pearson, S. McKnight, A. S. Kende, E. P. Greenberg, and B. H. Iglewski. 1999. Quinolone signaling in the cell-to-cell communication system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11229-11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poole, K., N. Gotoh, H. Tsujimoto, Q. Zhao, A. Wada, T. Yamasaki, S. Neshat, J. Yamagishi, X. Z. Li, and T. Nishino. 1996. Overexpression of the mexC-mexD-oprJ efflux operon in nfxB-type multidrug-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 21:713-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poole, K., K. Krebes, C. McNally, and S. Neshat. 1993. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: evidence for involvement of an efflux operon. J. Bacteriol. 175:7363-7372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pumbwe, L., and L. J. V. Piddock. 2000. Two efflux systems expressed simultaneously in multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2861-2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quinn, J. P. 1998. Clinical problems posed by multiresistant nonfermenting gram-negative pathogens. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:S117-S124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rengstrom, K., S. Sauge-Merle, K. Chen, and B. K. Burgess. In Azotobacter vinelandii, the E1 subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex binds fpr promoter region DNA and ferredoxin I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12389-12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Rietsch, A., M. C. Wolfgang, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2004. Effect of metabolic imbalance on expression of type III secretion genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 72:1383-1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 43.Sanchez, P., J. F. Linares, B. Ruiz-Diez, E. Campanario, A. Navas, F. Baquero, and J. L. Martinez. 2002. Fitness of in vitro selected Pseudomonas aeruginosa nalB and nfxB multidrug resistant mutants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:657-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato, H., D. W. Frank, C. J. Hillard, J. B. Feix, R. R. Pankhaniya, K. Moriyama, V. Finck-Barbancon, A. Buchaklian, M. Lei, R. M. Long, J. Wiener-Kronish, and T. Sawa. 2003. The mechanism of action of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa-encoded type III cytotoxin, ExoU. EMBO J. 22:2959-2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shevchenko, A., M. Wilm, O. Vorm, and M. Mann. 1996. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68:850-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sobel, M. L., G. A. McKay, and K. Poole. 2003. Contribution of the MexXY multidrug transporter to aminoglycoside resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3202-3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whiteley, M., K. M. Lee, and E. P. Greenberg. 1999. Identification of genes controlled by quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:13904-13909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yahr, T. L., and D. W. Frank. 1994. Transcriptional organization of the trans-regulatory locus which controls exoenzyme S synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 176:3832-3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yahr, T. L., L. M. Mende-Mueller, M. B. Friese, and D. W. Frank. 1997. Identification of type III secreted products of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S regulon. J. Bacteriol. 179:7165-7168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yahr, T. L., A. J. Vallis, M. K. Hancock, J. T. Barbieri, and D. W. Frank. 1998. ExoY, an adenylate cyclase secreted by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:13899-13904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ziha-Zarifi, I., C. Llanes, T. Kohler, J. C. Pechere, and P. Plesiat. 1999. In vivo emergence of multidrug-resistant mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa overexpressing the active efflux system MexA-MexB-OprM. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:287-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]