Abstract

The shared decision-making (SDM) model is one in which providers and consumers of health care come together as collaborators in determining the course of care. The model is especially relevant to youth mental health care, when planning a treatment frequently entails coordinating both youth and parent perspectives, preferences, and goals. The present paper first provides the historical context of the SDM model and the rationale for increasing our field's use of SDM when planning psychosocial treatments for youth and families. Having established the potential utility of SDM, the paper then discusses how to apply the SDM model to treatment planning for youth psychotherapy, proposing a set of steps consistent with the model and considerations when conducting SDM with youth and families.

Keywords: Shared Decision-Making, Treatment Planning, Children, Treatment

Planning treatment for youth psychopathology is a complex endeavor. Each case brings with it myriad decisions, including what is the problem, how best to treat the problem, who best to treat the problem, and who should be involved in treatment. At the same time, planning a treatment based on the evidence has never been easier as the field advances in areas of evidence-based assessment (Jensen-Doss, 2015; Youngstrom, 2013), evidence-based case conceptualizations (Christon, McLeod, & Jensen-Doss, 2015; McLeod, Jensen-Doss, & Ollendick, 2013), understanding of mechanisms of change (Doss, 2004), and the availability of empirically-supported treatment approaches (Southam-Gerow & Prinstein, 2014). However, though each of these approaches encourages the active involvement of patients in treatment planning, the application of theoretically-grounded approaches to such collaborations is rare, and specific guidelines to facilitate such collaborative relationships are largely absent. The shared decision-making (SDM) model is one in which providers and consumers of health care come together as collaborators in determining the course of care, at the start of and throughout treatment, providing a mechanism through which treatment providers and consumers can actively engage in treatment planning while using the evidence base to guide their decisions.

The vast majority of work on using SDM to plan treatments is found in the medical literature (Shay & Lafata, 2015), but the past decade has demonstrated a growing interest in applying SDM to mental health treatments (Wills & Holmes-Rovner, 2006). This is fortunate, as using SDM may help actualize the principles of evidence-based practice in psychology, which is the integration of the evidence base, clinician experience and expertise, and child and family characteristics, culture, and preferences (American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice, 2006). The present paper first provides the historical context of the SDM model and the rationale for increasing our field's use of SDM when planning psychosocial treatments for youth and families. Having established the potential utility of SDM, the paper then discusses how to apply the SDM model to treatment planning for youth psychotherapy, proposing a set of steps consistent with the model and considerations when conducting SDM with youth and families.

Shared Decision-Making

Definition and Historical Context

Broadly, the SDM model is one in which providers and consumers interact to make healthcare decisions collaboratively. Although theorists vary considerably on the specific elements of SDM, most agree that it entails the exchange of information, identification of consumer values and preferences, discussion of treatment options, and agreement on a treatment plan (see review by Clayman & Makoul, 2009). Other commonly cited elements of SDM include defining the roles of the provider and consumer early on in the treatment process, and checking and clarifying understanding (Charles, Gafni, & Whelan, 1997; Elwyn, Edwards, Kinnersley, & Grol, 2000), and some theorists specify that the discussion of treatment options should include a discussion of the benefits, risks, and costs of each option, the research evidence behind each option, or both (Coulter, 1997; Towle & Godolphin, 1999). In the present paper, we refer to the “SDM Model” broadly, anticipating that how SDM looks in practice will vary across treatment providers and consumers, especially in the context of youth psychotherapy, when working with a wide range of youth and families. The sample SDM protocol we present below reflects our adaptation of the model to youth psychotherapy, but is only one of many ways one might incorporate SDM into youth treatment planning.

Although the inclusion of patients' perspectives in treatment planning may seem commonplace now, including patients in the decision-making process is a notable departure from the majority of medical history. As an example, the first Code of Ethics of the American Medical Association advised patients to be fully obedient to a physician's directives, and not allow their own “crude opinions” to interfere with their adherence to the physician's treatment plan (American Medical Association, 1848). The paternalistic framework was dominant through the first half of the 20th century, in which the care provider is the sole expert and leader of the treatment process (Parsons, 1951). The original conceptualization of informed consent reflects this perspective; a patient would be fully informed of the diagnosis and treatment plan and asked to consent to it, yet the provider was still considered the sole expert in the treatment process, responsible for treatment decisions. The advent of SDM in the early 1980s (President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine, Biomedical, & Behavioral Research, 1982) began shifting the patient's role away from consenting to the provider-developed treatment plan, to planning treatment in conjunction with a provider. Efforts to advance the study of SDM and the implementation of SDM more widely since that time have been steadily growing through new research, national and international meetings, and the creation of groups devoted to furthering the practice of SDM (Blanc et al., 2014; O'Connor, Llewellyn-Thomas, & Stacey, 2005; Holmes-Rovner & Rovner, 2009; Edwards & Elwyn, 2001). Broader efforts promoting patient-centered care are also in alignment with SDM, such as the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (2003), the Institute of Medicine (2006) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2006).

Rationale

The rationale for SDM can be divided into a principles-based argument and an outcomes-based argument. The principles-based rationale is that SDM is inherently good because it is consistent with the value society has placed on patient autonomy and patient-centered care. Autonomy is exercised when one acts intentionally, with understanding, and without controlling influences that determine action (Beauchamp & Childress, 2001). Apart from any potential measurable benefits of SDM (e.g., improved clinical outcomes), SDM seeks to enable patients to exercise their autonomy and make decisions, ideally based on research evidence, that will raise the likelihood of outcomes they view as favorable, and decrease the likelihood of side effects they view as aversive. Although this is not an empirical argument for SDM, it is important to note the substantial support leading organizations have given to an SDM approach, suggesting the consensus that SDM is in line with societal and professional values. These organizations include the National Institute of Mental Health (1999), the Institute of Medicine (2001), the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010), and the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics (Mercurio et al., 2008).

The second, outcomes-based argument, proposes that SDM may improve treatment processes, treatment outcomes, or both. Actively including clients in the treatment planning process through SDM, regardless of the treatment approach chosen, may enhance client alliance and engagement in the treatment activities, which in turn may lead to more favorable outcomes (Loh, Leonhart, Wills, Simon, & Härter, 2007). Loh and colleagues (2007) found that training physicians to utilize SDM in the primary care of depression increased client participation in, adherence to, and satisfaction with treatment, though there was no clear effect on depression severity. It is also possible planning treatments using the SDM process results in the selection of treatments that are better matched to individual patient needs. For example, incorporating caregiver and youth perspectives into treatment planning may result in focusing the treatment on problems that are more central to a youth's functioning (even if those problems are not neatly defined by a clinical diagnosis), and selecting a treatment approach that better fits a family's culture and plays on a family's strengths. There is research outside of the mental health field demonstrating patients often choose less risky treatments when they are provided with more complete information (Hawker et al., 2001), and that outcomes may be enhanced when using SDM (Shay & Lafata, 2015).

Research evaluating the efficacy of SDM for youth mental health treatment is sparse, and though we argue that ideally SDM will incorporate youth in the decision-making process as well, existing research has not yet studied child-focused SDM for youth mental health (Feenstra et al., 2014). Of the research looking at conducting SDM with parents, Brinkman and colleagues trained pediatricians in using SDM techniques with caregivers of children newly diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), finding that caregivers meeting with the pediatricians after they had been SDM-trained were more knowledgeable and less conflicted about treatment options compared to the caregivers who met with the pediatricians prior to the SDM training (Brinkman et al., 2013). Clinical outcomes were not significantly different between the groups, however. Golnik and colleagues (2012), in their study of caregivers of youth with autism, reported a direct and significant correlation between the amount of SDM the caregivers reported and their satisfaction with their child's healthcare. Research on the incorporation of SDM in adult mental health care, though still limited, is more established and has shown beneficial changes in treatment adherence, satisfaction, knowledge, involvement in decision-making, and some clinical outcomes (Simon, Wills, & Harter, 2009; Stacey et al., 2014).

The complexities of treatment planning for youth psychotherapy present unique challenges to conducting SDM, yet these same complexities are precisely why SDM is especially relevant to youth psychotherapy. Frequent disagreement between youths and caregivers about the presenting problem and treatment goals (Yeh & Weisz, 2001; De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005), in addition to disagreements between youths, caregivers, and their clinicians (Hawley & Weisz, 2003), suggest that a process to foster agreement – or at least compromise – among clinicians, caregivers and youth may ensure that each person's perspective is considered. Beyond being “good practice,” working towards a commonly agreed upon treatment plan may also address some of the ethical and legal issues associated with treatment consent and assent for youth psychotherapy, especially in instances of disagreement (Weithorn & Campbell, 1982; Redding, 1993). More fully incorporating caregiver and youth perspectives in treatment planning may also assist in addressing treatment problems that are not reflected in a pre-treatment diagnostic assessment, as diagnostic profiles may not accurately reflect the most pressing problems (Weisz et al., 2011). Planning youth treatment also requires personalization to address the presenting problem using developmentally appropriate techniques (Holmbeck, Devine, & Bruno, 2010; Weisz & Hawley, 2002). SDM is especially indicated when increased patient commitment to comply with treatment tasks is needed (Montori, Gafni, & Charles, 2006), and this is common in evidence-based approaches for youth psychotherapy, which typically has treatments lasting multiple sessions and requiring out-of-session practice (Weisz & Kazdin, 2010). Lastly, in non-mental health treatment, it has been demonstrated that youth throughout middle childhood and adolescence do want to be involved in treatment decisions (Coyne, 2006; Kelsey, Abelson-Mitchell, & Skirton, 2007), and are capable of being involved in such decisions (Weithorn & Campbell, 1982; Redding, 1993; Alderson, Sutcliffe, & Curtis, 2006).

In addition, youth and caregivers have been shown to have preferences regarding the treatment approach. For example, several studies have found that youth and/or caregivers prefer psychosocial interventions over medication for a range of conditions including depression (Jaycox et al., 2006), obsessive-compulsive disorder (Lewin, McGuire, Murphy, & Storch, 2014), anxiety (Brown, Deacon, Abramowitz, Dammann, & Whiteside, 2007), and ADHD (Brinkman & Epstein, 2011; Johnston, Hommersen, & Seipp, 2008). There is not yet research exploring whether caregivers and youth have preferences regarding one psychosocial treatment approach versus other psychosocial treatment approaches. Preferences, which can be viewed as the result of one's values applied to the available information (Wills & Holmes-Rovner, 2006), are likely to change as the caregiver and youth learn more about the available treatment options. Given the well-documented malleability of preferences, and the large degree to which preferences may change based on the way in which the information about treatment options is presented (Reyna, Nelson, Han, & Pignone, 2015), using SDM to plan treatment may also align preferences with the most effective treatment plan, potentially enhancing engagement while satisfying the ethical imperative of patient autonomy.

Integration with Case Conceptualization Models and Evidence-Based Treatments

The implementation of SDM in the context of youth psychotherapy supports the use of empirically grounded principles of case conceptualization and evidence-based treatments. Although research evaluating the effectiveness of specific case conceptualization models is sparse, there is general consensus that developing research-informed hypotheses about the root causes, immediate antecedents, and maintaining factors of a client's psychological difficulties is necessary to design an empirically-supported treatment plan. In most discussions of case conceptualization models, the default agent constructing the case conceptualization is the clinician. In an SDM model, the clinician's expertise is still used to organize the assessment information into a theoretically-grounded understanding of the case, but the caregiver and youth take a more active role in identifying the priorities to target and the approaches to target those priorities. This may also increase the provision of culturally competent treatment (Whitley, 2009). Models of culturally competent case conceptualization and treatment frequently include principles of SDM, though the principles are rarely labeled as such. As an example, when caregivers and youths are more actively engaged in the treatment planning process, the treatment plan will not only reflect the clinician's assumptions about a family's cultural values, practices, affiliation, and identity, but the family's own understanding and application of their culture to the treatment (Pina, Villalta, & Zerr, 2009). In this way, the process of SDM may facilitate the creation of shared narratives, in which clinician and family perspectives are integrated and aligned (Lakes, López, & Garro, 2006). Although cultural differences between the clinician and client(s) are the focus of most work on culturally competent care, there is also considerable evidence that there are likely differences in acculturation and ethnic identity within families (see Bornstein & Cote, 2006). SDM may help the clinician address these differences through active discussion, clarifying how each family member's acculturation and ethnic identity may impact his or her perspective on symptoms, treatment goals, and treatment choices. Thus, SDM supports the delivery of culturally competent care.

At first blush, an SDM approach may seem risky for proponents of evidence-based treatment. If the research is clear about which treatment is best for a client's problem, shouldn't that be the end of the discussion? An alternate view is that SDM facilitates the integration of the evidence base into the clinician–client discussion, along with emphasizing the importance of including the client in defining the problem to be targeted, as clinician and client perspectives may differ (e.g., Zimmerman et al., 2006). This is consistent with more recent conceptualizations of the EBPP model, in which rather than a “three legged-stool” in which the evidence base supports EBPP equally along with clinical expertise and client characteristics (Spring, 2007), the evidence base is filtered through clinical expertise and client characteristics (Tolin, 2014). SDM provides a process to filter the evidence in a structured way to evaluate the degree to which the most supported treatments fit with the conceptualization of the client's symptoms, but also the client's values, preferences, and goals. Elwyn and colleagues (2014) conceptualize a continuum between SDM and motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2012), in which SDM processes are predominant when there are multiple reasonable options, and motivational interviewing (a therapeutic style intended to help clients resolve ambivalence toward needed behavior change; Miller & Rollnick, 2012) is used when there is only one reasonable treatment option. Both SDM and motivational interviewing assist youth and caregivers in acknowledging and understanding problems that may exist, and then choosing and committing to a plan to change. In this way, SDM joins motivational interviewing as a technique to help youth and caregivers proceed along the stages of change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 2005). However, though SDM may be most useful in cases of equipoise – when there are multiple treatment options with relatively equal effectiveness and treatment decisions may be based more on family preferences, values, and goals – SDM may also be helpful when there is one clear treatment “winner.” There may be other choice points within a “winner” treatment that can incorporate SDM, such as decisions about specific treatment goals, treatment participants, and other aspects of treatment that are malleable.

The integration of the SDM model and evidence-based treatments is further supported by the novel, ongoing research on adaptive interventions (see Almirall & Chronis-Tuscano, 2016). By providing data to answer treatment planning questions – for example, “What is the best treatment to try first?” and “What treatment should be next in line should the first treatment not lead to an adequate response?” – adaptive interventions research provides valuable information that can be used in the SDM process for initial and ongoing treatment planning. Conversely, SDM may provide those developing adaptive interventions with a theoretically-grounded method of incorporating client perspectives into the sequences of decision rules that guide the interventions.

Shared Decision-Making for Youth Psychotherapy

Sample SDM Protocol for Youth Psychotherapy

Conducting SDM in youth psychotherapy may take many forms, though at its core, an SDM process must, at a minimum: 1) include the youth, the caregiver, or both in a decision making process with the clinician, with the possibility of including other stakeholders as well; 2) facilitate sharing information bi-directionally, with the clinician sharing information about psychopathology and treatment options, and receiving information about the youth's symptoms, and the youth and caregivers' preferences, values, and goals; and 3) determine the course of action collaboratively, through a process of discussion, compromise, and agreement (Charles et al., 1997). Decision aids - tools that assist those involved in making health care decisions – may be used to support the decision making process (Durand et al., 2015), by providing information about disorders and treatment, or by specifying pros and cons of different choices and guiding clinicians and clients through the process of making a decision. The International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration has specified criteria to meet the standards of a high quality decision aid (e.g., using a systematic development process, containing up-to-date scientific evidence, presenting information clearly; Durand et al., 2015). Several organizations offer collections of decision aids, such as the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/) and Option Grids (http://www.optiongrid.org/), though formal decision aids are not necessary to conduct SDM. Unfortunately, decision aids for youth mental health remain limited.

Typically, an SDM session would occur after a diagnostic assessment (McLeod et al., 2013), and clinicians committed to using an SDM approach to treatment planning may incorporate new assessment measures and/or intake interview topics into their intake protocol to facilitate treatment planning (e.g., perspectives on top problems, preferences on who should participate in treatment planning and actual treatment). Before engaging in SDM with caregivers and youth, the clinician could also learn more about how the family typically makes decisions (e.g., kids are actively involved in family decisions vs. parents make authoritarian decisions). The SDM process would likely change based not only on the preferences of caregivers and youth (some may have more motivation to collaborate on treatment planning than others), but also on the developmental status of the youth. For example, an adolescent may be the primary decision maker when determining the target problems and the amount of caregiver participation in treatment, whereas a school-age child may learn about his/her options and share his/her perspectives, but leave decision making to his/her caregiver and therapist. Youth with a greater ability to acknowledge difficulties when they exist, understand treatment options and the concept that some options are better than others, and articulate their preferences may participate more fully in SDM. Ideally, all youth will be involved in SDM as much as they are willing and able.

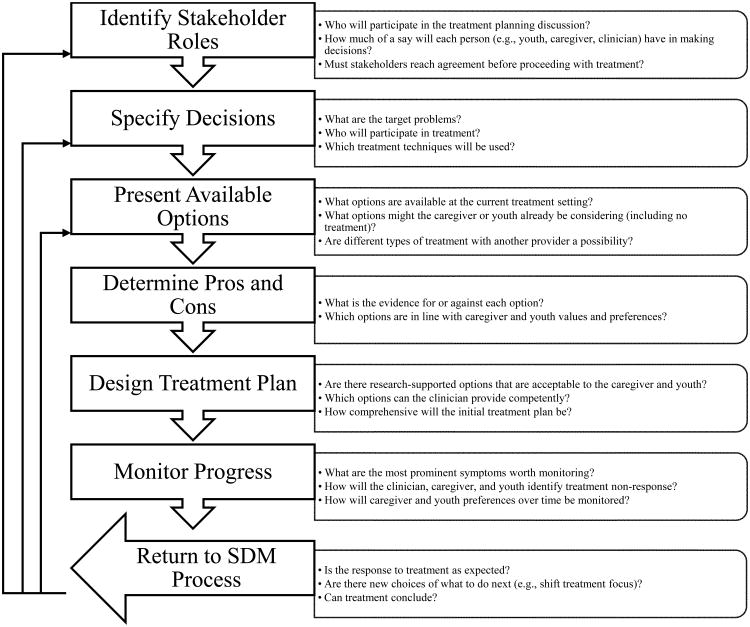

Although conducting SDM does not require a protocol, we present a sample SDM protocol below (and depicted in Figure 1), based on the essential and ideal elements of SDM as defined by multiple SDM theorists (see review by Clayman & Makoul, 2009). These steps may also be familiar to clinicians trained in problem-solving approaches.

Figure 1. Sample Shared Decision-Making Protocol.

Sample SDM Protocol

Discuss preferred roles in treatment planning. Whereas many caregivers and youth may value inclusion in the treatment planning process, others may prefer the clinician make treatment decisions independently. In these cases, it is important to discuss a caregiver and youths' rationale to ensure that their deference to the clinician is not reflecting a more traditional, paternalistic understanding of the patient's role in health care. Caregivers and youth may also disagree about how much of a say each of them should (and will) have in making decisions.

Specify decisions to be made. What decisions are possible will depend on the clinician and setting. Decisions may include which problems to target in treatment, which family members will participate in treatment, what type of communication caregivers will have with the clinician, how much confidentiality caregivers will allow the clinician to maintain with the youth, and what type of treatment to use (or which skills to focus on).

Present the available options for each decision. A multitude of choices may overwhelm the decision makers and interfere with high-quality decision making (Chernev, Böckenholt, & Goodman, 2015). To simplify the process, the top few choices for each decision should be presented. Which choices are considered “top” will, ideally, be based on the case conceptualization and the available research evidence. If a caregiver or youth requests an option that was not included, it should be added to the list for consideration as well, even if the likelihood of making that choice is negligible (e.g., wanting a treatment that is not available or counter-indicated). Options to be considered may also include seeking services with another provider who can offer indicated interventions not offered by the clinician, or “watchful waiting,” in which the decision is not to start treatment.

Determine pros and cons of each option. Research support (or lack thereof) is a central pro (or con) for any option, but there may be times when there is not a clear “winner” according to the available research, or an option that has less strong research support is a better fit with the case conceptualization or the family's values and goals. Some decisions may have to be made without guidance from the research literature and may be more based on clinician, caregiver, and youth opinion (e.g., how the clinician will communicate with caregivers, which problem to target first). Elicitation of the pros and cons from each decision maker's perspective will highlight differences between the choices and facilitate decisions that are consistent with a family's values.

Design preliminary treatment plan. In this step, the clinician and family discuss the pros and cons of each option and formulate an initial treatment plan. To simplify the process, similar to the process for selecting which options to present, in cases where caregivers and youth lack strong preferences, the default option would be the option with the most research support that is consistent with the case conceptualization, and that is able to be provided in the service setting. In cases where research support is unavailable or unclear, the default option would be the approach most familiar and most practiced by the clinician and service setting, as long as there are no research findings to suggest that such an approach is likely to be inert or lead to negative effects.

Implement progress monitoring. Ongoing progress monitoring is key to evidence-based practice and also to SDM. The effectiveness of the treatment plan is continually evaluated through targeted assessment measures so that adjustments could be made should progress be stalled, or the youth's presentation becomes more severe. Caregiver and youth preferences may also change as the course of treatment continues and the effectiveness of their decisions becomes clearer. An SDM approach can be used throughout treatment when needed to revise the treatment plan, and clinicians may wish to hold regular “SDM check ins.”

Challenges to SDM Implementation

Availability of treatment options

SDM is only relevant when there are multiple options from which the clinician and client can choose; limited availability of treatment options can present a challenge to applying SDM in youth psychotherapy. Even when a clinician's skill set or the setting's services are severely limited, though, there are still many choices to be made, such as whether treatment should be pursued, what the focus of treatment will be, who will be included in treatment, and whether additional services will be sought. Clinicians who provide treatments consisting of different skills and techniques (e.g., cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, exposure) may work with clients to decide which skills to include and how to arrange the skills in a treatment plan. This is especially applicable to the formulation of treatment plans based on modular treatments (i.e., treatments containing free-standing modules which could be selected and arranged to be responsive to client needs). Modular treatments offer greater adaptability for applied contexts, and have been shown to be more effective than standard manualized treatments when outcomes are assessed at posttreatment (Chorpita, Daleiden, & Weisz, 2005; Weisz et al., 2012). Clinicians and clients may also benefit from a collaborative discussion on how to track treatment progress (Boswell, Kraus, Miller, & Lambert, 2013), such as what outcomes to assess, who will provide ratings, and how frequently to assess progress.

Relatedly, depending on the treatment options available, and the culture of the clinician and setting, some settings and clinicians may favor unstructured SDM processes, in which clinicians and clients engage in a discussion that abides by the core tenets of SDM without a formal guide or protocol. This would be analogous to conducting cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with or without a manual. We are unaware of any research findings suggesting that conducting high-quality CBT requires using a manual, but established protocols and the manuals that describe them may help clinicians deliver the treatment adherently.

Availability of research on treatment effectiveness

This challenge to SDM implementation is two-fold: 1) information regarding a treatment's effectiveness, which is often a key factor in clinician and client decision making, is only as strong as the research conducted on that treatment, and there are a wide range of treatment approaches being used in mental health service settings (McLeod & Weisz, 2010) not all of which have been evaluated through formal research studies, and 2) even when there are research findings for a given treatment approach, clinician access to the research base is often restricted (e.g., journal subscriptions required) and familiarizing oneself with the research is time-intensive (e.g., reading primary articles may not be feasible for a community clinician with high caseloads). Regarding the lack of treatment effectiveness research, this is a challenge that is present for clinicians unilaterally planning treatments as well as those using an SDM approach. Even without extensive data on treatment options, we argue that clients should still be involved in the decision process, basing decisions on the same amount of information that is available to the clinicians. Regarding clinician access to research findings, several initiatives have sought to aggregate the research on treatment effectiveness by either providing publically-available lists of the evidence behind different treatment approaches (e.g., the Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology's Evidence Base Update Series; Southam-Gerow & Prinstein, 2014), by aggregating research findings to facilitate literature searches (www.tripdatabase.com), by identifying the empirical support for individual treatment techniques (e.g., contingency management) for specific target problems (Chorpita & Daleiden, 2009), or through the creation of research-based clinical guidelines (e.g., National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2016; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2016). Although research findings on a wide range of treatment techniques may be limited, information on which treatments have not been evaluated through formal research may also be helpful for decision makers to know. As research advances, initiatives to create ready-to-use decision aids have also been growing (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 2015), along with processes to certify these decision aids (Durand et al., 2015), to facilitate the process of informing and guiding decision makers.

Willingness of clinicians to incorporate client input into treatment plan

Most clinicians may already incorporate client perspectives into their case conceptualization and treatment plan, though, at least in non-mental health contexts, observational studies suggest involving clients in an SDM process is rare (Couet et al., 2015) without corresponding data for the frequency of SDM in mental health services. Transitioning from a clinician-driven model to an SDM model would require a shift in the way that client preferences, values, and goals are incorporated into the treatment plan, however. Two important conditions that are frequently misunderstood in relation to SDM should be regularly clarified with clinicians: 1) SDM is collaborative by nature and the treatment plan is not based solely on client preference, and 2) the clinician sets the boundaries for what choices are acceptable. If, as a result of SDM, a client wants an approach the clinician is not able to provide (e.g., due to lack of training, clinician's judgment that the approach is counter-indicated), the clinician can and should provide feedback to the client on the their perspective and, if needed, appropriate referrals. We would argue that having this discussion earlier on in the therapy process is much preferable to discovering a fundamental disagreement further along in treatment, when such a disagreement might lead to poorer treatment outcomes due to decreased engagement in treatment or premature termination.

Disagreement on treatment-related decisions between caregivers and youths

SDM in youth psychotherapy differs from many other forms of SDM in that there are multiple consumers (youths and caregivers). Caregivers and youths frequently disagree on what the target problem is and what the treatment should be (Yeh & Weisz, 2001), and difficulties resolving disagreements among caregivers and youths present a barrier to effective collaboration with the clinician. Disagreements that may be glossed over in traditional, clinician-led treatment planning need to be explicitly acknowledged and addressed during the SDM process. Although a comprehensive discussion of possible techniques to resolve disagreement is beyond the scope of this paper, clinicians may help foster agreement between caregivers and youths by using common negotiation and mediation strategies, such as facilitating communication, reconceptualizing the disagreement and framing the problem differently, identifying shared values and/or goals, and working to develop creative solutions that will meet the needs of both caregivers and youths (Carnevale & Pruitt, 1992; Kressel, 2014). Work on navigating disagreements, such as in the Collaborative & Proactive Solutions (CPS) approach (Ollendick et al., 2015), has shown that with clinician support, caregivers and youth are often able to work together, even when they are seeking treatment for familial conflict and youth oppositional behaviors, and learning how to solve problems collaboratively may offer clinical benefits (Ollendick et al., 2015; Wade, Michaud, & Brown, 2006). In cases where agreement cannot be reached (or would require more time than is available), the clinician can propose a treatment plan, ideally including target problems and treatment components that are responsive to both caregiver and youth concerns. The degree to which the treatment plan reflects caregiver or youth input will likely vary based on the presenting problem, the developmental level of the child, and the research supporting different treatment approaches. Progress monitoring can then be used to evaluate and revise this plan as needed. Divergent perspectives among various participants, though not a new challenge, may be a more potent challenge when engaging families in shared decision-making. However, we choose to see this disagreement problem as an opportunity. Participant perspectives, whether or not they converge, provide valuable data to be used in the treatment planning process (De Los Reyes, 2011).

Discrepancies between SDM choices and the evidence base

There may be situations where SDM results in choosing a treatment with less research support. This may be completely appropriate, as a treatment approach that did not fare as well in group comparisons may still be a better fit for an individual family. Even if the clinician believes that a treatment with a stronger evidence based would be preferable, a treatment with less support may still be preferable to no treatment at all (should a family refuse to participate in a research-supported but non-preferred treatment), and with an engaged client, there remains the possibility of revising the treatment plan if the client is not making steady progress. The frequency with which SDM results in choices with less research support is an empirical question that has not yet been answered.

Future Directions

Expanding the evidence base on SDM for youth psychotherapy

Beyond the need for more research on how to conduct SDM with more than one treatment consumer (e.g., how to handle disagreement), there are considerable gaps in the literature in the area of SDM and youth psychotherapy. The limited research on SDM for youth mental health that does exist focuses predominantly on helping caregivers choose between psychopharmacological approaches (Brinkman et al., 2013). Understanding the risks and benefits of different medications is qualitatively distinct from the differences between psychosocial therapeutic approaches. Similar to medications, contrasting two psychotherapies includes discussion of their relative risks and benefits (e.g., likelihood of treatment non-response or worsening versus success, associated financial costs). However, though caregivers and youths may readily understand the tasks associated with medication options (e.g., taking a pill at specified times of the day, receiving required blood tests and monitoring), understanding the tasks associated with different psychotherapy options is more complex (e.g., different skills to learn, number of sessions, amount of work outside of session, involvement from caregivers). Understanding the options may require a certain amount of psychoeducation, and determining how much psychoeducation is needed is an important empirical question. In addition, research on helping those with poor numeracy understand risk and potential for success (Zikmund-Fisher, Mayman, & Fagerlin, 2014) is needed, as well as more research on how to help caregivers and youths orient to the idea of participating actively in treatment planning, and to choose (and understand the differences) between psychosocial approaches by providing developmentally appropriate information for caregivers and youth to encourage evidence-based choices. Research on psychoeducational approaches with youth and caregivers has shown that, in addition to the possibility of developing more informed mental health care consumers, it may lead to clinical benefits as well (e.g., Fristad, Verducci, Walters, & Young, 2009).

Implementing SDM in usual care settings

Implementation of SDM practices in usual care settings remains a considerable challenge. Even with active encouragement to engage in SDM, observational studies suggest low levels of SDM in both non-mental health (Elwyn et al., 2003; Guimond et al., 2003) and mental health contexts (Loh et al., 2006; Young, Bell, Epstein, Feldman, & Kravitz, 2008; Brinkman et al., 2011). And efforts to increase the uptake of SDM by healthcare professionals have largely neglected mental health care providers (Légaré et al., 2010). Recent years have seen advances, however. In 2010, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration convened stakeholders for an interdisciplinary meeting on SDM in mental health care practice settings. And the Ottawa Health Research Institute Implementation Toolkit (https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/implement.html), the Evidence-Based Behavioral Practice training modules (www.ebbp.org), and the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation's SDM resources (www.informedmedicaldecisions.org) provide resources to help providers incorporate SDM into their practices. It will be especially important in future research efforts to evaluate the ability of clinicians to implement SDM independently with diverse populations, settings, and cultures, as the generalizability of the current SDM research remains unclear.

Conclusion

Planning treatments for youth may never be a straightforward endeavor – coordinating multiple decision makers in resource-limited contexts with a constantly evolving evidence base is not easy – but there are ways to strengthen the process of planning treatments. In our view, actively involving caregivers and youths in treatment planning fits with our values as a profession (American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice, 2006) and may improve the effectiveness of the treatment planning process. A responsive treatment plan developed through a shared decision-making approach may lead to more personalized, effective uses of existing evidence-based treatments, while engaging families in the treatment process.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant K23-MH 101238 (DAL).

Contributor Information

David A. Langer, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Boston University

Amanda Jensen-Doss, Department of Psychology, University of Miami.

References

- Alderson P, Sutcliffe K, Curtis K. Children as partners with adults in their medical care. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2006;91(4):300–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.079442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almirall D, Chronis-Tuscano A. Adaptive Interventions in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2016;45(4):383–395. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1152555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice Parameters 2016 [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association. Code of ethics of the American Medical Association, adopted May 1847. Philadelphia, PA: T.K. and P.G. Collins; 1848. Article II Obligations of patients to their physicians; pp. 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice. Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist. 2006;61(4):271–285. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. 5th. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc X, Collet T, Auer R, Fischer R, Locatelli I, Iriarte P, et al. Cornuz J. Publication trends of shared decision making in 15 high impact medical journals: A full-text review with bibliometric analysis. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2014;14(71):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-14-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Cote LR, editors. Acculturation and parent–child relationships: Measurement and development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boswell JF, Kraus DR, Miller SD, Lambert MJ. Implementing routine outcome monitoring in clinical practice: benefits, challenges, and solutions. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research. 2013;25(1):6–19. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.817696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman WB, Hartl J, Poling LM, Shi G, Zender M, Sucharew H, et al. Epstein JN. Shared decision-making to improve attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder care. Patient Education and Counseling. 2013;93(1):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman WB, Hartl J, Rawe LM, Sucharew H, Britto MT, Epstein JN. Physicians' shared decision-making behaviors in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder care. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165(11):1013–1019. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman WB, Epstein JN. Treatment planning for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Treatment utilization and family preferences. Patient Preference and Adherence. 2011;5:45–56. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S10647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AM, Deacon BJ, Abramowitz JS, Dammann J, Whiteside SP. Parents' perceptions of pharmacological and cognitive-behavioral treatments for childhood anxiety disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(4):819–828. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale PJ, Pruitt DG. Negotiation and mediation. Annual Review of Psychology. 1992;43(1):531–582. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.43.020192.002531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (Or it takes at least two to tango) Social Science & Medicine. 1997;44(5):681–692. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernev A, Böckenholt U, Goodman J. Choice overload: A conceptual review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2015;25(2):333–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2014.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Weisz JR. Modularity in the design and application of therapeutic interventions. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2005;11(3):141–156. doi: 10.1016/j.appsy.2005.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):566–79. doi: 10.1037/a0014565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christon LM, McLeod BD, Jensen-Doss A. Evidence-based assessment meets evidence-based treatment: An approach to science-informed case conceptualization. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2015;22(1):36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clayman ML, Makoul G. Conceptual variation and iteration in shared decision-making: The need for clarity. In: Edwards A, Elwyn G, editors. Shared decision-making in health care. 2nd. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Couet N, Desroches S, Robitaille H, Vaillancourt H, Leblanc A, Turcotte S, et al. Legare F. Assessments of the extent to which health-care providers involve patients in decision making: A systematic review of studies using the OPTION instrument. Health Expectations. 2015;18(4):542–561. doi: 10.1111/hex.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter A. Partnerships with patients: The pros and cons of shared clinical decision-making. Journal of Health Services Research. 1997;2(2):112–121. doi: 10.1177/135581969700200209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne I. Consultation with children in hospital: Children, parents' and nurses' perspectives. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2006;15(1):61–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A. Introduction to the special section: More than measurement error: Discovering meaning behind informant discrepancies in clinical assessments of children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(1):1–9. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(4):483–509. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD. Changing the way we study change in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11(4):368–386. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durand M, Witt J, Joseph-Williams N, Newcombe RG, Politi MC, Sivell S, Elwyn G. Minimum standards for the certification of patient decision support interventions: Feasibility and application. Patient Education and Counseling. 2015;98(4):462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A, Elwyn G. Evidence-based patient choice: Inevitable or impossible? Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P, Grol R. Shared decision making and the concept of equipoise: The competences of involving patients in healthcare choices. The British Journal of General Practice. 2000;50:892–899. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G, Edwards A, Wensing M, Hood K, Atwell C, Grol R. Shared decision making: Developing the OPTION scale for measuring patient involvement. Quality & Safety in Health Care. 2003;12(2):93–9. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G, Dehlendorf C, Epstein RM, Marrin K, White J, Frosch DL. Shared decision making and motivational interviewing: Achieving patient-centered care across the spectrum of health care problems. Annals of Family Medicine. 2014;12(3):270–275. doi: 10.1370/afm.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feenstra B, Boland L, Lawson ML, Harrison D, Kryworuchko J, Leblanc M, Stacey D. Interventions to support children's engagement in health-related decisions: A systematic review. BMC Pediatrics. 2014;14(1):109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Verducci JS, Walters K, Young ME. Impact of multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy in treating children aged 8 to 12 years with mood disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66(9):1013–1021. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golnik A, Maccabee-Ryaboy N, Scal P, Wey A, Gaillard P. Shared decision making: Improving care for children with autism. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2012;50(4):322–331. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-50.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimond P, Bunn H, O'Connor AM, Jacobsen MJ, Tait VK, Drake ER. Validation of a tool to assess health practitioners' decision support and communication skills. Patient Education and Counseling. 2003;50(3):235–45. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, Williams JI, Harvey B, Glazier R, et al. Badley EM. Determining the need for hip and knee arthroplasty: The role of clinical severity and patients' preferences. Medical Care. 2001;39(3):206–216. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200103000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley KM, Weisz JR. Child, parent and therapist (dis)agreement on target problems in outpatient therapy: The therapist's dilemma and its implications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):62–70. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN, Devine KA, Bruno EF. Developmental issues and considerations in research and practice. In: Weisz JR, Kazdin AE, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. 2nd. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes-Rovner M, Rovner D. International collaboration in promoting shared decision-making: A history and prospects. In: Edwards A, Elwyn G, editors. Shared decision-making in health care. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Institute of Medicine; Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions. Institute of Medicine; Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Asarnow JR, Sherbourne CD, Rea MM, LaBorde AP, Wells KB. Adolescent primary care patients' preferences for depression treatment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2006;33(2):198–207. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Doss A. Practical, evidence-based clinical decision making: Introduction to the special series. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2015;22(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C, Hommersen P, Seipp C. Acceptability of Behavioral and Pharmacological Treatments for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Relations to Child and Parent Characteristics. Behavior Therapy. 2008;39(1):22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey J, Abelson-Mitchell N, Skirton H. Perceptions of young people about decision making in the acute healthcare environment. Paediatric Nursing. 2007;19(6):14–18. doi: 10.7748/paed.19.6.14.s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kressel K. The mediation of conflict: Context, cognition, and practice. In: Coleman PT, Deutsch M, Marcus EC, editors. The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice. 3rd. San Francisco, CA, US: Jossey-Bass; 2014. pp. 817–848. [Google Scholar]

- Lakes K, López SR, Garro LC. Cultural competence and psychotherapy: Applying anthropologically informed conceptions of culture. Psychotherapy. 2006;43(4):380–396. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Légaré F, Ratté S, Stacey D, Kryworuchko J, Gravel K, Graham ID, Turcotte S. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. The Cochrane Library. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin AB, McGuire JF, Murphy TK, Storch EA. Editorial Perspective: The importance of considering parent's preferences when planning treatment for their children-the case of childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55(12):1314–1316. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh A, Leonhart R, Wills CE, Simon D, Härter M. The impact of patient participation on adherence and clinical outcome in primary care of depression. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007;65(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh A, Simon D, Hennig K, Hennig B, Härter M, Elwyn G. The assessment of depressive patients' involvement in decision making in audio-taped primary care consultations. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;63(3):314–318. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Jensen-Doss A, Ollendick TH. Case conceptualization, treatment planning, and outcome monitoring. In: McLeod BD, Jensen-Doss A, Ollendick TH, editors. Diagnostic and behavioral assessment in children and adolescents: A clinical guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Weisz JR. The Therapy Process Observational Coding System for Child Psychotherapy Strategies scale. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(3):436–443. doi: 10.1080/15374411003691750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercurio MR, Adam MB, Forman EN, Ladd RE, Ross LF, Silber TJ. American Academy of Pediatrics policy statements on bioethics: Summaries and commentaries: Part 1. Pediatrics in Review. 2008;29(1) doi: 10.1542/pir.29-1-e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. Guilford press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Montori VM, Gafni A, Charles C. A shared treatment decision-making approach between patients with chronic conditions and their clinicians: The case of diabetes. Health Expectations. 2006;9(1):25–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016 Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/

- National Institute of Mental Health. Bridging science and service: A report by the National Advisory Mental Health Council Clinical Treatment and Services Research Workgroup. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor A, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Stacey D. IPDAS Collaboration Background Document: International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration. 2005 Retrieved from http://ipdas.ohri.ca/IPDAS_Background.pdf.

- Ollendick TH, Greene RW, Austin KE, Fraire MG, Halldorsdottir T, Allen KB, Cunningham NR. Parent management training and collaborative & proactive solutions: A randomized control trial for oppositional youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1004681. online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Patient decision aids. 2015 Retrieved from https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZlist.html.

- Parsons T. Illness and the role of the physician: A sociological perspective. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1951;21(3):452–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1951.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Public Law. 2010:111–148. Retrieved from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf.

- Pina AA, Villalta IK, Zerr AA. Exposure-based cognitive behavioral treatment of anxiety in youth: An emerging culturally-prescriptive framework. Behavioral Psychology. 2009;17(1):111–135. [Google Scholar]

- President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine, Biomedical & Behavioral Research. Making Health Care Decisions Volume One: Report 1982 [Google Scholar]

- President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achieving the promise: Transforming mental health care in America. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. No. SMA-03-3832. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. The transtheoretical approach. In: Norcross JC, Goldfried MR, editors. Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration. Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Redding RE. Children's competence to provide informed consent for mental health treatment. Washington and Lee Law Review. 1993;50(2):696–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyna VF, Nelson WL, Han PK, Pignone MP. Decision making and cancer. American Psychologist. 2015;70(2):105–118. doi: 10.1037/a0036834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Medical Decision Making. 2015;35(1):114–131. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14551638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D, Wills CE, Harter M. Shared decision-making in mental health. In: Edwards A, Elwyn G, editors. Shared decision-making in health care: Achieving evidence based patient choice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 269–272. [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Prinstein MJ. Evidence base updates: The evolution of the evaluation of psychological treatments for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(1):1–6. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.855128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring B. Evidence-based practice in clinical psychology: What it is, why it matters; what you need to know. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;63(7):611–631. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey D, Legare F, Col N, Bennett C, Barry M, Eden K, et al. Wu J. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National consensus statement on mental health recovery. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Shared decision-making in mental health care: Practice, research, and future directions. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2010. No. SMA-09-4371. [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF. Beating a dead dodo bird: Looking at signal vs. noise in cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2014;21(4):351–362. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Towle A, Godolphin W. Framework for teaching and learning informed shared decision making. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed) 1999;319:766–771. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade SL, Michaud L, Brown TM. Putting the pieces together: preliminary efficacy of a family problem-solving intervention for children with traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2006;21(1):57–67. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200601000-00006. doi:00001199-200601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Frye A, Ng MY, Lau N, Bearman SK, et al. Hoagwood KE. Youth top problems: Using idiographic, consumer-guided assessment to identify treatment needs and to track change during psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79(3):369–380. doi: 10.1037/A0023307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Palinkas LA, Schoenwald SK, Miranda J, Bearman SK, et al. Gibbons RD. Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: A randomized effectiveness trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):274–82. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Hawley KM. Developmental factors in the treatment on adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(1):21–43. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Kazdin AE. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weithorn L, Campbell SBC. The competency of children and adolescents to make informed treatment decisions. Child Development. 1982;53(6):1589–1598. doi:0.2307/1130087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley R. The implications of race and ethnicity for shared decision-making. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2009;32(3):227–230. doi: 10.2975/32.3.2009.227.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills CE, Holmes-Rovner M. Integrating decision making and mental health interventions research: Research directions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13(1):9–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh M, Weisz JR. Why are we here at the clinic? Parent–child (dis) agreement on referral problems at outpatient treatment entry. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(6):1018–25. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young HN, Bell RA, Epstein RM, Feldman MD, Kravitz RL. Physicians' shared decision-making behaviors in depression care. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(13):1404–1408. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom EA. Future directions in psychological assessment: Combining evidence-based medicine innovations with psychology's historical strengths to enhance utility. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42(1):139–159. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.736358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Mayman G, Fagerlin A. Patient numeracy: What do patients need to recognize, think, or do with health numbers? In: Anderson BL, Schulkin J, editors. Numerical reasoning in judgments and decision making about health. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2014. pp. 80–104. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB, Posternak MA, Friedman M, Attiullah N, Boerescu D. How should remission from depression be defined? The depressed patient's perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):148–150. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]