Abstract

The complement system has been thought to originate exclusively in the deuterostomes. Here, we show that the central complement components already existed in the primitive protostome lineage. A functional homolog of vertebrate complement 3, CrC3, has been isolated from a ‘living fossil', the horseshoe crab (Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda). CrC3 resembles human C3 and shows closest homology to C3 sequences of lower deuterostomes. CrC3 and plasma lectins bind a wide range of microbes, forming the frontline innate immune defense system. Additionally, we identified CrC2/Bf, a homolog of vertebrate C2 and Bf that participates in C3 activation, and a C3 receptor-like sequence. Furthermore, complement-mediated phagocytosis of bacteria by the hemocytes of horseshoe crab was also observed. Thus, a primitive yet complex opsonic complement defense system is revealed in the horseshoe crab, a protostome species. Our findings demonstrate an ancient origin of the critical complement components and the opsonic defense mechanism in the Precambrian ancestor of bilateral animals.

Keywords: complement, evolution, innate immunity, protostome

Introduction

Comparative studies have suggested common ancestries of innate defense mechanisms in both vertebrates and invertebrates (Hoffmann et al, 1999; Kimbrell and Beutler, 2001). It was proposed that germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) conduct non-self recognition (Medzhitov and Janeway, 2000, 2002; Gordon, 2002) by binding unique microbial cell surface components, which are popularly referred to as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Examples of PAMPs are endotoxin or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Gram-negative bacteria, lipoteichoic acid (LTA) of Gram-positive bacteria, and β-glucan of fungi. Recognition of PAMPs initiates various innate immune responses, such as the activation of opsonic and lytic complement pathways in vertebrates, the coagulation cascade in arthropods and, more generally, the phagocytosis of the pathogen, and the lysis of the pathogen by antimicrobial peptides. To date, known PRRs include membrane-integrated Toll receptors in Drosophila and Toll-like receptors in mammals, and many carbohydrate-binding lectins that circulate in the blood or hemolymph. However, the concept of PAMP and PRR was deemed to be inaccurate, while specific individual molecules rather than the ‘molecular patterns' are recognized in most instances (Beutler, 2004).

As an arthropod, the horseshoe crab is a unique ‘living fossil' that has been in continuous existence for up to 550 million years (Twenhofel and Shrock, 1935; Størmer, 1952). A comparative study of its innate immune defense mechanisms would contribute to further understanding of the evolution of innate immunity in both invertebrates and vertebrates. LPS- or β-D-glucan-induced coagulation cascade represents a potential defense mechanism in the horseshoe crab (Iwanaga, 2002), and has been employed as a standard sensitive method of endotoxin detection for decades (Ding and Ho, 2001). However, all the coagulation cascade components, known antimicrobial peptides, and most agglutinating lectins are confined within the horseshoe crab hemocytes. How the hemocytes are activated to release these defense molecules in vivo in response to various pathogen invasions remains largely unknown. Although early studies have shown that both the plasma and hemocytes are required for the bactericidal activity (Furman and Pistole, 1976; Pistole and Britko, 1978), the molecular mechanism of the pathogen scavenging pathway in horseshoe crabs remains a mystery to be solved (Kawabata and Tsuda, 2002). In order to define the frontline defense molecules in the horseshoe crab, we used live microbes as affinity matrix to isolate innate immune molecules from the cell-free hemolymph. Serendipitously, a vertebrate C3-characteristic protein, CrC3 (Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda C3), was identified together with several plasma lectins. Similar overall profiles of the ensemble of CrC3 and plasma lectins were found to bind all the representative microbes studied. In addition, we identified CrC2/Bf, a homolog of vertebrate complement 2 (C2) and factor B (Bf), which are trypsin-like serine proteases (Tryp_SP) that take part in proteolytic activation of C3. Furthermore, we show evidence for the production of a putative anaphylactic peptide upon activation of CrC3 by various pathogens. Together with the identification of a vertebrate C3 receptor homolog, a complement defense system homologous to that of deuterostomes is discovered in this ancient protostome lineage.

Complement system with opsonic and lytic effector pathways had been thought to exist exclusively in vertebrates. However, the identification of vertebrate C3 homologs with opsonic activity and potential C3 convertases in sea urchins and tunicates suggests an earlier development in the lower deuterostomes of complement system with only opsonic effector pathway, which plays an important role in innate immunity (for recent reviews, see Nonaka and Yoshizaki, 2004a, 2004b). Thus, the finding of homologs of the key components of vertebrate complement system in the horseshoe crab demonstrates an earlier origin of the complement system, in the ancestor of both protostomes and deuterostomes.

Results

Identification of bacteria-binding proteins using live bacteria as affinity matrix

To define the frontline recognition and defense molecules in the horseshoe crab, live Staphylococcus aureus served as ‘bacterial beads' to adsorb bacteria-binding proteins from the plasma. The plasma proteins that were associated with the bacteria were extracted with different buffers and analyzed by SDS–PAGE (Figure 1A and B). Urea effected higher extraction efficiency than acidic or alkaline buffers. The observed major protein bands of interest from urea extracts were in-gel digested with trypsin and further analyzed by mass spectrometry.

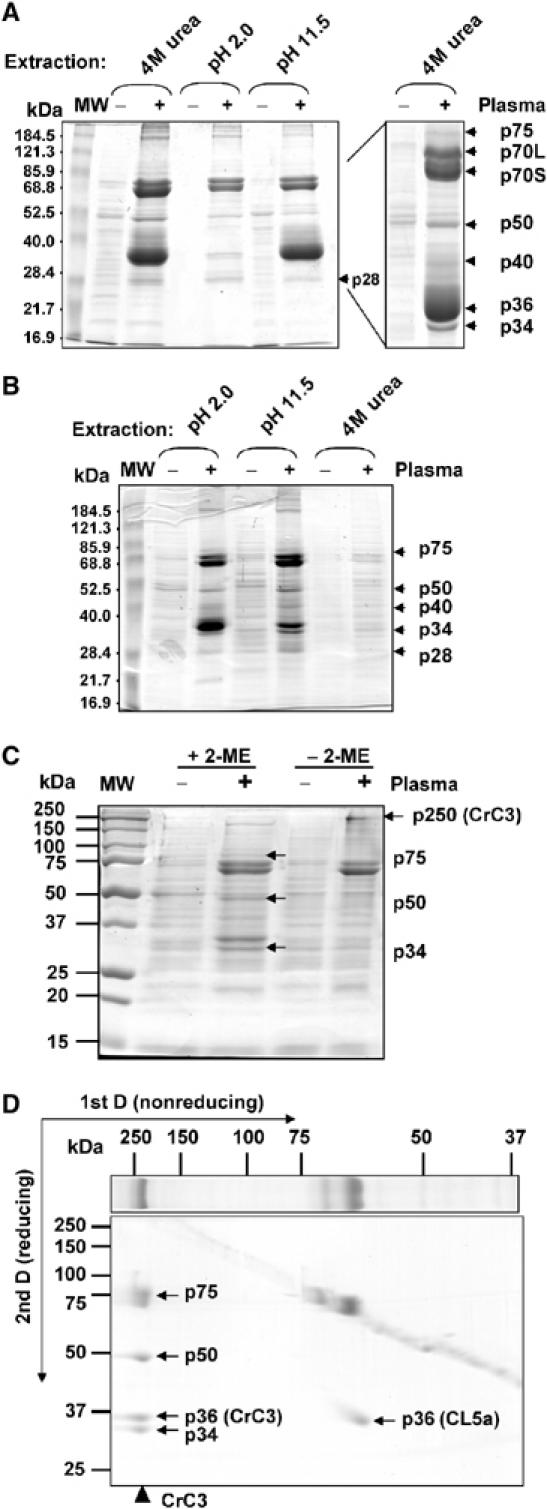

Figure 1.

Isolation and characterization of CrC3. Bacteria-binding proteins from horseshoe crab plasma were recovered by elution from S. aureus cells incubated with the horseshoe crab cell-free plasma (‘−', control S. aureus treated in saline; ‘+', S. aureus incubated with plasma), under different buffer conditions as indicated. (A) Profile of plasma proteins extracted from the bacteria at indicated conditions. Protein sample derived from ∼0.25 ml each of bacteria/plasma was loaded per lane (see Materials and methods). (B) Protein profiles of bacteria after extraction (∼0.25 ml of bacteria per lane). (C) Comparison of total protein profiles of S. aureus cells (‘−', untreated bacterial cells; ‘+', bacterial cells incubated with plasma), treated with triethanolamine (pH 11.5 (B)), that were solubilized in nonreducing condition (−2-ME) and reducing condition (+2-ME). Protein extract derived from ∼0.25 ml each of bacterial cells was loaded per lane. (D) 2D SDS–PAGE (nonreducing 1st D and reducing 2nd D) analysis of protein profile of S. aureus cells (treated with plasma) that were solubilized in nonreducing condition. CrC3 of ∼250 kDa (p250) observed in the 1st D was resolved into p75, p50, p36(CrC3), and p34 after reduction.

The proteins identified by either peptide mass fingerprint (PMF) and/or MS-MS sequencing are summarized in Table I. p36 and p40 were revealed to be the C. rotundicauda homologs of tachylectin 5a and 5b (TL5a and TL5b), respectively, of the horseshoe crab Tachypleus tridentatus (Iwanaga, 2002). These are the major agglutinating plasma lectins in horseshoe crabs. Thus, p36 and p40 were named as carcinolectins CL5a and CL5b, respectively. p28 matched the T. tridentatus plasma lectin 1, TPL1 (Chen et al, 2001). In addition to these known immune molecules, p34 and p75 (Figure 1) were found to contain peptide fragments homologous to vertebrate C3, while no significant match was found for p50 (Table I). Vertebrate C3 is a large protein of ∼200 kDa, with two chains bridged by disulfide bond and is further cleaved upon pathogen-mediated activation. To test if p34 and p75 are fragments from a similar precursor protein, we reanalyzed the SDS-extracted proteins from plasma-incubated S. aureus cells that were treated with triethanolamine, where most CL5s were removed. The protein profiles were compared by SDS–PAGE under the nonreducing and reducing conditions (Figure 1C), and further examined by 2D SDS–PAGE (Figure 1D, nonreducing 1st D and reducing 2nd D). The results clearly show that p34, p50, and p75 are derived from a protein with an apparent molecular weight ∼250 kDa (under nonreducing condition). In addition, another fragment of CrC3, p36(CrC3), which previously comigrated with p36 (CL5a), was also displayed in the 2D gel.

Table 1.

Identification of bacteria-binding proteins by MS

| PMF hit | Fragment sequences | Short nearly exact match | MS-BLAST hit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p28 | TPL1/TL1 | ND | N/A | N/A |

| p34 | No reliable hit | SVSFPVVPLK | Vertebrate C3s | No reliable hit |

| All othersa | No HSP | |||

| p36 | TL5a/TL5b | EFWLGNDR | TL5a/TL5b/ficolin A | TL5s, ficolin, fibrinogen |

| MDNDNGGWTLL | Fibrinogen beta chain | |||

| All others (not shown) | No HSP | |||

| p40 | TL5b/TL5a | ND | N/A | N/A |

| p50 | No reliable hit | TGVGGDLGAELAAAPR | Hypothetical protein | No reliable hit |

| LAAVGGGASAGFLDAAK | Hypothetical protein | |||

| All othersa | No HSP | |||

| p70S | Hemocyanin G | ND | N/A | N/A |

| p70L | Hemocyanin HR6 | YDELGN(LF)/(FL)PGGK | Hemocyanin subunits | Hemocyanin subunit HR6 |

| All others (not shown) | No HSP | |||

| p75 | ND | LGLLAVDEAVYLLR | Vertebrate C3s | Vertebrate C3s |

| All othersa | No HSP | |||

| HSP, high-score pairing; ND, not determined; N/A, not applicable; PMF, peptide mass fingerprint; TL, tachylectin. It should be noted that L is either leucine or isoleucine in the sequences interpreted from mass spectra. | ||||

| aPeptide sequences not shown in the table for p34, p50, and p75 are as follows: p34: NEKVELKATVDK, ELME(EM)ELVK, VTFKFPLNLKGGS(SG)AR, ETWLFDDVYVGPK, ASVAG(GA)NGGSAV(ASV, SVA, VSA, TGV)K, LLSLQLDPTNQGAK, HLYLLK, VGEFPVR, LNVVPEGA(AG)K (bold fragments were used as template for the design of degenerate primers for RT–PCR); p50: FGPVVETALENTEK, AAAYLELK, LLELDEK, EELQQLVDPR, PM(MP)PVSVLADR, LLSMATFQADK, TVGPHSTG(SA)LAAVGGGASAGFLDAAK, YNVPVPPEK,CLVSVLADR; and p75: TGDLLLLGTVPPPK, LGLLAVDEAVYLLR, LDA(GE)KETLSVLLVSGGK, LVVPHVYK, ETLLLVNPR, FGPVVETALF, AGNWFHK, LNLVEAT(TA)K. | ||||

Characterization of CrC3, a vertebrate C3 homolog

Based on the peptide sequences of p34 determined by mass spectrometry, degenerate primers were designed for RT–PCR to amplify a cDNA fragment of p250. Thereafter, 5′ and 3′ RACE was performed to isolate the full-length cDNA sequence (6069 bases, GenBank accession number AF517564), coding for a C3-characteristic precursor protein of 1737 amino-acid residues including a predicted secretion leader peptide of 21 amino acids (Supplementary Figure 1). BLAST homology search yielded closest matches of this sequence with C3 and C4 of vertebrates, C3 of lower deuterostome species, and α-2 macroglobulin (α2M) or thioester protein (TEP) of arthropods and worms. Thus, this protein was named CrC3 (C. rotundicauda C3). The CrC3 protein sequence matches most closely, at 35% similarity, the C3 of lancelet (BAB47146).

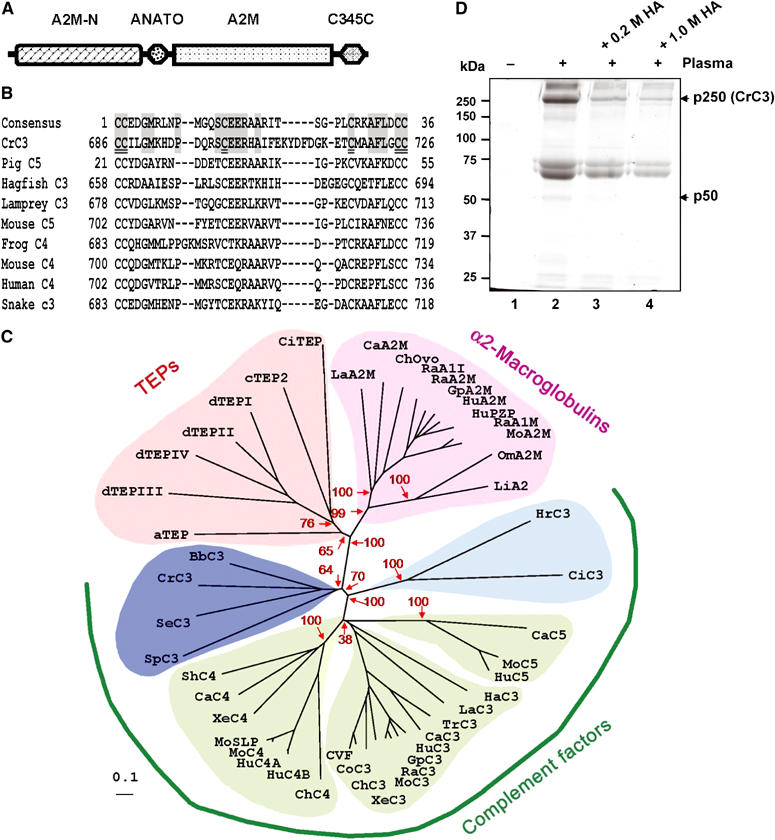

Consistently, conserved domain search indeed revealed a vertebrate C3/C4/C5-characteristic modular architecture of CrC3 (Figure 2A), which contains a central complement C3/C4/C5-specific anaphylatoxin domain (ANATO) and an extreme C-terminal C345C domain, in addition to the N-terminal A2M-N domain and C-terminal A2M domain shared by the whole TEP superfamily. Figure 2B shows the alignment of ANATO region of CrC3 with the most similar ANATO sequences found in the databases. The ANATO domain of CrC3 shows high sequence similarity to vertebrate C3/C4/C5 ANATOs, and contains all the six cysteine residues critical for C3/C4/C5 anaphylatoxin peptide structure.

Figure 2.

CrC3 is a homolog of vertebrate C3. (A) Schematic modular organization of CrC3, a standard modular structure of vertebrate C3/C4/C5. The scheme is drawn as revealed by conserved domain search at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi. Conserved domain database references: A2M_N (pfam01835.11), N-terminal region of the TEP super family; ANATO (pfam01821.11; smart00104.10), anaphylatoxin-like domain; A2M (pfam00207.11), the C-terminal region of the α2M/TEP/C3/C4/C5 family; and C345C, an additional module at the extreme C-terminus of C3/C4/C5 (pfam01759.11, smart00643.10). (B) Alignment of C3/C4/C5-characteristic ANATO region of CrC3 with the most homologous sequences in frog C4 (BAA11188.1), hagfish C3 (P98094), human C4 (P01028), lamprey C3 (Q00685), mouse C4 (P01029), mouse C5 (P06684), pig C5 (1C5A), and snake C3 (Q01833). The six most-conserved cysteine residues critical for maintaining the structure of C345a peptides through three pairs of disulfide bonds are double-underlined. (C) Phylogeny of CrC3 and related TEPs. The scale bar corresponds to 0.1 estimated amino-acid substitutions per site. The confidence scores (in %) of a bootstrap test of 1000 replicates are indicated in red for major branching nodes. Selected proteins are: aTEP, Anopheles TEP-I; dTEPI, Drosophila TEP1; dTEPII, Drosophila TEP2; dTEPIII, Drosophila TEP3; dTEPIV, Drosophila TEP4; cTEP, Caenorhabditis TEP2; SeC3, cnidaria C3-like protein; BbC3, Amphioxus C3; SpC3, sea urchin C3; HrC3, Halocynthia C3; CiC3, Ciona C3; HaC3, hagfish C3; LaC3, lamprey C3; TrC3, trout C3; CaC3, carp C3-H1; XeC3, Xenopus C3; ChC3, chicken C3; CoC3, cobra C3; CVF, cobra venom factor; HuC3, human C3; GpC3, guinea pig C3; RaC3, rat C3; MoC3, mouse C3; CaC4, carp C4; ShC4, shark C4; ChC4, chicken C4; XeC4, Xenopus C4; MoC4, mouse C4; MoSPL, mouse sex limited protein (M21576); HuC4A, human C4A (K02403); HuC4B, human C4B (U24578); CaC5, carp C5; MoC5, mouse C5; HuC5, human C5; LiA2M, horseshoe crab α2M; LaA2M, lamprey α2M; ChOvo, chicken ovostatin; RaA1I, rat alpha1-inhibitor; HuPZP, human pregnancy zone protein; GpA2M, guinea pig α2M; HuA2M, human α2M; RaA2M, rat α2M; RaA1M, rat alpha1-macroglobulin; MoA2M, mouse α2M; CiTEP, Ciona intestinalis TEP; OmA2M, Ornithodoros (soft tick) α2M. For further information including database accession numbers, see Supplementary Table 1. (D) HA inhibits the attachment of CrC3 to bacteria. HA was added into the plasma to a final concentration of 0.2 or 1.0 M. S. aureus cells were incubated with naïve plasma or plasma supplemented with HA (see Materials and methods) at room temperature for ∼15 min. Washed bacterial cells were lysed in SDS–PAGE loading buffer and analyzed by nonreducing SDS–PAGE. ‘−', untreated bacterial cells; ‘+', bacterial cells incubated with horseshoe crab plasma with/without HA supplemented; protein samples derived from ∼50 μl bacteria (OD600 nm ∼0.5) or bacteria/plasma were loaded per lane.

Vertebrate complement C3/C4/C5, pan-protease inhibitor α2Ms in both vertebrates and invertebrates, and nonclassical α2M-type TEPs including insect and worm TEPs (Azumi et al, 2003) form a TEP superfamily, and possibly share a common ancient ancestor. C3 is deemed to be the ortholog of C3/C4/C5, while gene duplication brought about the appearance of paralog C4 and C5 in vertebrates (Zarkadis et al, 2001). A phylogenetic tree constituting CrC3 and evolutionarily related TEPs was constructed using the neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). For comparison, all C3/C4/C5 and α2M/TEP in a recent phylogenetic analysis (Levashina et al, 2001), and 10 more sequences including newly identified C3-like sequences (cnidaria, amphiox, sea urchin), were used for the phylogenetic analysis (Supplementary Table 1). Figure 2C shows an unrooted tree constructed with correction for multiple substitutions. The topologies of all the previously analyzed proteins in the phylogenetic tree appear identical as in the published trees (Levashina et al, 2001; Azumi et al, 2003), except that the C4 subgroup appears to divert from C3 before C5 subgroup. However, the confidence score of C5-diverging node is very low (38%). Without correction for multiple substitutions, the unrooted tree shows that C5 diverges before C4 (Supplementary Figure 2). This difference made by the correction most likely indicates the different evolutionary constraint and molecular evolution rate of C5 and C4 from that of C3, due to the functional divergence. In the unrooted trees, the CrC3 forms a clade with C3s of the lower deuterostome lineage (the amphiox C3 and the sea urchin C3), and the cnidaria C3-like protein (AAN86548.1), which was recently deposited into database (Dishaw et al, unpublished). The phylogenetic analysis clearly shows that CrC3 shares a common ancestor with deuterostome complement proteins. In other words, C3 diverged very early from α2M/TEP, before the protostome–deuterostome split. The C3-like sequence of cnidaria, a primitive animal with radial symmetry (Radiata), may represent the ancient Precambrian C3 ancestor, from which deuterostome C3 and protostome C3 are derived.

To test whether CrC3 binds to the bacterial surface through covalent crosslink (ester bond or amide bond) like that of vertebrate C3, we studied the effect of hydroxylamine (HA) on the CrC3 attachment. HA is a small nucleophilic molecule that can penetrate into proteins and deactivate the buried thioester. The addition of HA significantly inhibited the attachment of CrC3 (p250) to bacteria (Figure 2D). This indicates that the thioester of native CrC3 is very important for its binding to bacterial surface, possibly through covalent ester bond linkage. In addition, the previously visible minimal attached fragment, p50 (vertebrate C3dg counterpart), also became undetectable when the HA concentration increased from 0.2 to 1.0 M.

Thus, CrC3 is a homolog of vertebrate C3, in both sequence and function. Southern and Northern blot analysis was also carried out to further characterize CrC3. Widespread spatial expression of CrC3 shown by Northern blot analysis (Supplementary Figure 3) implies the importance of CrC3 to the innate immune defense against pathogen infection. Interestingly, Southern genomic blot analysis suggests more than one copy of the CrC3 gene in the horseshoe crab genome (Supplementary Figure 3B). Screening the hepatopancreas cDNA library showed isoforms of the CrC3 cDNAs (unpublished data). Multiplicity of C3 seems to be an evolutionary strategy used by many organisms, especially bony fish where the C3 isoforms were shown to have different reactivities to various activating surfaces (Sunyer et al, 1998).

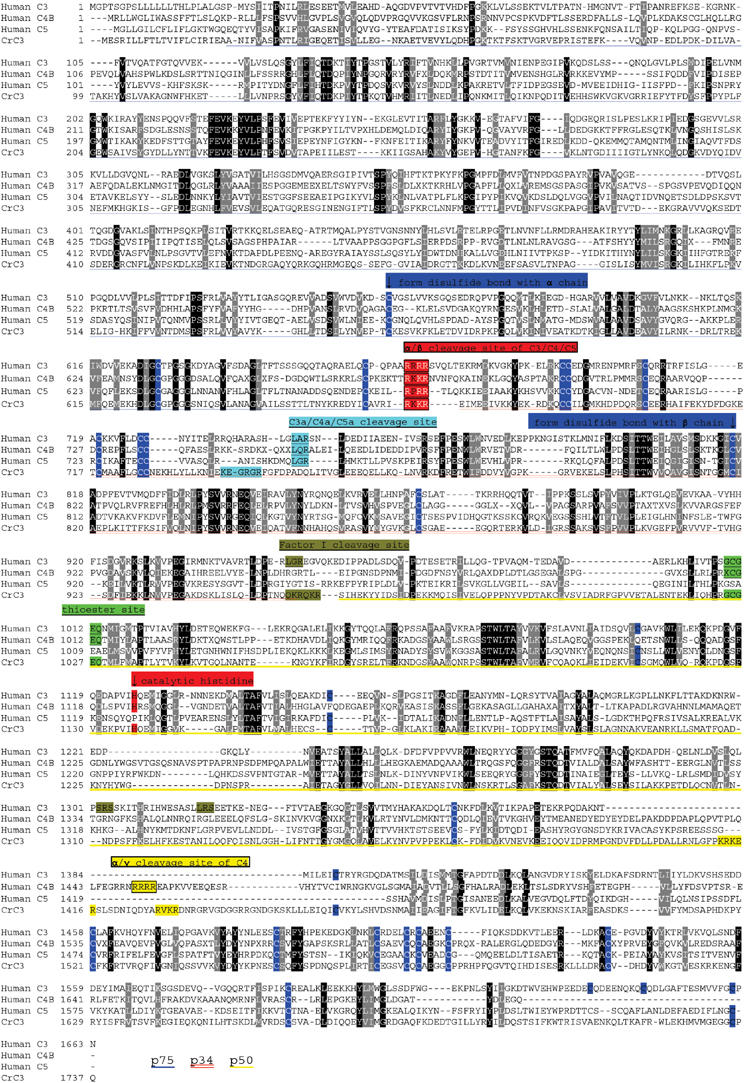

CrC3 exhibits characteristic features of human C3

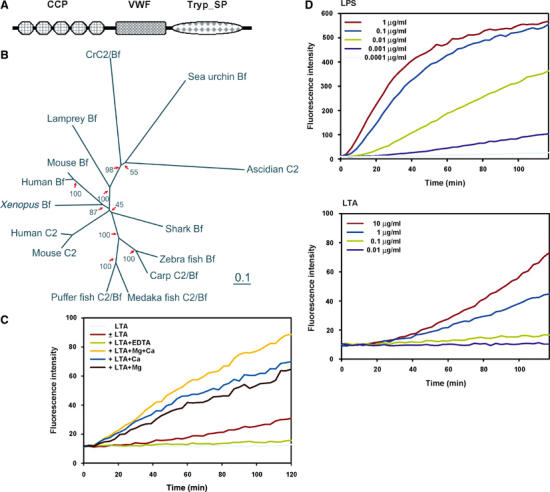

To date, human C3/C4/C5 has been studied in great detail. Thus, we show a full-sequence alignment of CrC3 and human C3/C4B/C5 (Figure 3). A C3/C4/C5-characteristic α/β joint process site, RKKR (666–669), is located upstream of the ANATO domain. A canonical thioester motif, GCGEQ (1024–1028), and the conserved catalytic His1137 were found to align perfectly. All of the vertebrate species studied to date have both C3 and C4 with a catalytic His residue, while most α2M/TEPs have an Asn at the ‘catalytic' position of C3 and C4 (Dodds and Law, 1998). C5, which functions as an initiator of lytic membrane attack complex (MAC) formation, and does not require covalent binding to the target pathogen surface, has lost its thioester site in evolution. It is observed that with the exception of one pair of Cys residues at the extreme C-terminus (Cys1637, Cys1646), all Cys in the human C3 are conserved in CrC3, suggesting that CrC3 has a similar disulfide bond bridging pattern as that of human C3. However, the vertebrate C3 convertase-cleavage site, LXR (Nonaka and Yoshizaki, 2004a), is not found in CrC3. Instead, a potential site, EGR, which is very similar to the QGR in the ascidian C3, is observed. A three-chain structure of mature CrC3 is predicted based on the observation of two α/γ cleavage site-like motifs; the α chain was further cleaved to p34 and p50 upon activation, with the observation of a four-chain structure of CrC3 recovered from bacteria. The calculated distances predict that CrC3 is closer to human C3 than to C4 and C5, supporting the orthology of C3 in C3/C4/C5.

Figure 3.

Sequence comparison of CrC3 and the human C3, C4, and C5. The multiple sequence alignment of CrC3 with human C3 (P01024)/C4B (U24578)/C5 (P01031) was produced with ClustalX. All the cysteine residues of human C3 (except that in the thioester site GCGEQ) and conserved cysteines in the other sequences are highlighted. Other characteristic sites, including proteolytic cleavage sites, thioester sites, catalytic His sites, are also annotated accordingly. The inferred regions of p75, p50, and p34 in the CrC3 sequence are marked.

Binding of CrC3 and lectins (CL5s) to representative microbes

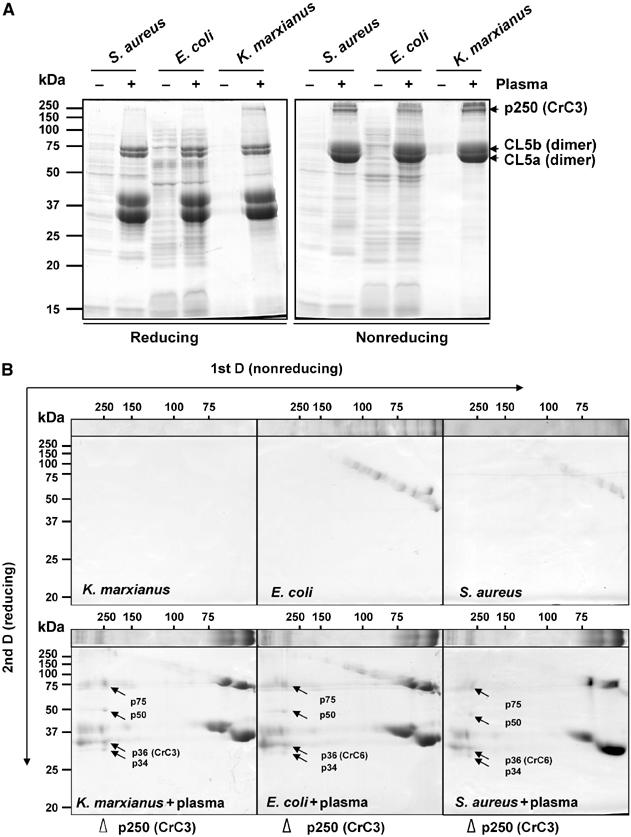

To test whether the binding of CrC3 and plasma lectins to S. aureus represents a general mechanism of recognition and opsonization of microbes in the horseshoe crab, we compared profiles of plasma proteins associated to Escherichia coli and Kluyveromyces marxianus to the profile of proteins associated with S. aureus. The bound proteins were directly extracted from the microbial cells and analyzed by SDS–PAGE under reducing and nonreducing conditions (Figure 4A). Indeed, similar overall patterns of adsorbed proteins were observed with S. aureus, E. coli, and K. marxianus. The major proteins observed are CrC3 (p250), CL5a, and CL5b.

Figure 4.

Similar profiles of plasma proteins bound to representative microbes. The major proteins that bind Gram-positive bacteria S. aureus, Gram-negative bacteria E. coli, and fungus K. marxianus are CL5a, CL5b, and CrC3. CrC3 bound to all microbes is fragmented into p75, p50, p36(CrC3), and p34. (A) Comparison of protein profiles of three microbes (untreated or treated with horseshoe crab plasma) under reducing and nonreducing conditions of solubilization (±2-ME). Protein samples derived from ∼0.2 ml each of microbial cells/plasma were loaded per lane. (B) 2D SDS–PAGE (nonreducing 1st D and reducing 2nd D) analysis of protein extracts from E. coli and K. marxianus that were incubated with horseshoe crab plasma.

Under nonreducing condition, CL5a and CL5b were mostly in dimeric forms, while reducing condition monomerized them, as reported for TL5a and TL5b (Gokudan et al, 1999). CL5a and CL5b appear to function synergistically in the recognition of various pathogens, which is similar to the report of widespread agglutination spectrum of TL5s. We have identified various isoforms of CL5a and CL5b by molecular cloning (unpublished results), and differential ligand specificity of these isoforms is speculated. The covalent dimerization of CL5a and CL5b, and the fragmentation of CrC3 (p250) were further confirmed by the 2D gel analysis (Figure 4B). The CrC3 attached to all the tested microbes were resolved into four fragments (p75, p50, p36, p34) under reducing condition (Figure 4B). The cleavage of CrC3 and dissociation of some of its fragments from the pathogen surface is also evidenced by the frequent observation of a greater intensity of p50, the minimal attached fragment, over that of p34 and p75 in the reducing SDS–PAGE analysis of total protein extracts or eluents from the microbes. In conclusion, the attachment of CL5s and CrC3 to the surfaces of different groups of invading microbes and subsequent proteolytic cleavage of CrC3 represent the frontline recognition/opsonization mechanism.

Identification of CrC2/Bf and PAMP-triggered Tryp_SP activity in the horseshoe crab plasma

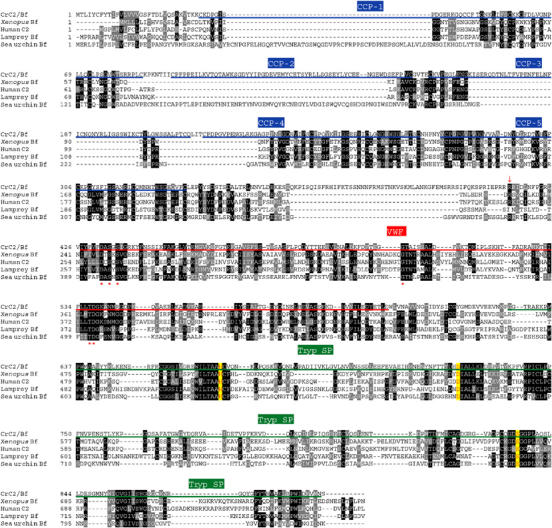

Among the cDNA sequences identified by subtractive hybridization of the cDNAs of hepatopancreas from naïve and bacteria-challenged horseshoe crab (Ding et al, in preparation), a cDNA fragment with sequence homology to vertebrate Bf and C2 was isolated. Thereafter, 3′ and 5′ RACE was carried out to obtain the full-length C2/Bf homologous sequence, which is referred to as CrC2/Bf. The complete cDNA of CrC2/Bf is 3093 bp (GenBank accession number AY647279), coding for a polypeptide of 889 amino-acid residues including a secretion signal peptide (Supplementary Figure 4). Database search of homologs showed its highest homology to the sea urchin C2/Bf. Sequence alignment of CrC2/Bf with the homologs in the sea urchin, lamprey, Xenopus, and human shows the putative cleavage site for factor D like that in vertebrate C2/Bf, the Mg-binding motif (Tuckwell et al, 1997), and the catalytic triad residues involved in the serine protease domain are well conserved (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Multiple alignment of CrC2/Bf and related proteins selected. The deduced amino-acid sequence of CrC2/Bf was aligned with C2 and/or Bf from Xenopus, human, lamprey, and sea urchin. For the database accession numbers of the selected sequences and information on various domains (CCP, VWF, and Tryp_SP), refer to the legend of Figure 6. The predicted active sites for serine protease activity are shown in yellow boxes, and factor D cleavage site is shown by a downward arrow. Consensus Mg2+-binding sites are marked (*).

The conserved domain architecture search of this protein indeed shows a C2/Bf-like structure. C2 is the serine protease part of C3-activating convertase complex in both the lectin pathway and classical pathway, while Bf is the serine protease counterpart in the alternative pathway in mammals. Bf and C2 are very similar and are believed to diverge in the jawed vertebrates and often referred to as C2/Bf (or Bf/C2). Ancestral C2/Bf possibly performs the functions of both C2 and Bf of mammals (Zarkadis et al, 2001). In contrast to vertebrate C2/Bf, which contains three complement control protein (CCP) modules, the CrC2/Bf harbors five CCP modules (Figure 6A) like that of C2/Bf of lower deuterostomes (ascidian and erchinoderm), which is regarded as the ancient form of C2/Bf (Smith et al, 1999, 2001). The CCP modules mediate complement binding (Hourcade et al, 1995). An unrooted phylogenetic tree constituting CrC2/Bf and proteins from CrC2/Bf family was constructed (Figure 6B). CrC2/Bf forms a clade with C2/Bf of the ascidian and the echinoderm. Presence of additional CCP modules at the N-terminus of the invertebrate C2/Bf proteins is clearly reflected in the phylogenetic tree, where the protein members harboring additional modules form a separate branch including CrC2/Bf. The similarity in sequence and structure organization of CrC2/Bf to that of the family of vertebrate C2/Bf proteins indicates that CrC2/Bf shares a common ancestor with that of deuterostomes.

Figure 6.

Identification of CrC2/Bf and PAMP molecule-triggered Tryp_SP activity. (A) Conserved domain architecture of CrC2/Bf revealed by database search at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi. Database references: complement control protein module (CCP), smart00033, pfam00084; von Willebrand factor type A domain (VWF), smart00327, pfam00092; trypsin-like serine protease (Tryp_SP), smart00020, pfam00089. (B) Unrooted phylogenetic tree of CrC2/Bf with other C2s and Bfs. The scale bar corresponds to 0.1 estimated amino-acid substitutions per site. The bootstrap test scores (in %) of 1000 replicates are indicated at the major branch nodes. Database accession numbers of the compared sequences are: human C2, AAB97607; human Bf, CAA51389; mouse C2, AAA37381; mouse Bf, P04186; Xenopus Bf, BAA06179; zebra fish Bf, AAC05096; carp C2/Bf, BAA34707; medaka fish, BAA12207; shark Bf, BAB63203; puffer fish C2/Bf, CAD21938; sea urchin Bf, AAC79682; ascidian C2, AAK00631; lamprey Bf, BAA027630. (C) PAMP molecules (LPS and LTA) trigger a Tryp_SP activity in the horseshoe crab plasma. The enzymatic assay was carried out as follows: 5 μl of plasma was added in replacement of the recombinant factor C into a 100 μl reaction volume of PyroGene™ Endotoxin Detection System (BioWhittaker™). LPS or LTA resuspended in pyrogen-free water was added into the reaction at different concentrations. The fluorescence intensity of the reaction was monitored for 2 h at excitation/emission wavelength of 380/440 nm (both at 2.5 nm slit) with plate reader using Luminescence Spectrometer LS50B (Perkin Elmer). The fluorescence intensity is corelational to the amount of substrate cleaved by the activated Tryp_SP activity. (D) LTA-triggered Tryp_SP activity requires Ca2+ and Mg2+. Enzymatic assays were carried out as above, with the addition of EDTA, CaCl2, or MgCl2 at 10 mM.

In vertebrates, the activation of complement system is mediated by a cascade of Try_SPs in different pathways, which merge at the proteolytic activation of C3. Thus, we tested for the activation of similar activity in the horseshoe crab plasma by PAMP molecules, LPS and LTA. Indeed, a Tryp_SP activity was triggered by both LPS and LTA (Figure 6C) in a concentration-dependent manner. It is notable that LPS stimulates the protease activity more rapidly and to a greater extent than LTA. In addition, it is observed that EDTA almost completely inhibited the activation of the Try_SP activity (Figure 6D), while addition of Mg2+, Ca2+, or both collectively increased the apparent activity (it should be noted that Mg2+ and Ca2+ are already present in the plasma, although diluted in the control reaction). It is known that the activity of vertebrate C2/Bf requires Mg2+ as a cofactor, while Ca2+ is required for the carbohydrate binding of TL5s (the counterpart of CL5s in Carcinoscorpius).

The role of activated Try_SP in CrC3 activation is speculated, with the participation of CrC2/Bf. Further studies are needed to clarify if CrC2/Bf functions as C2 (in the lectin pathway) or Bf (in the alternative pathway) or both, and the presence of an upstream protease (mannan-binding protein-associated serine protease, MASP) as CrC2/Bf activator.

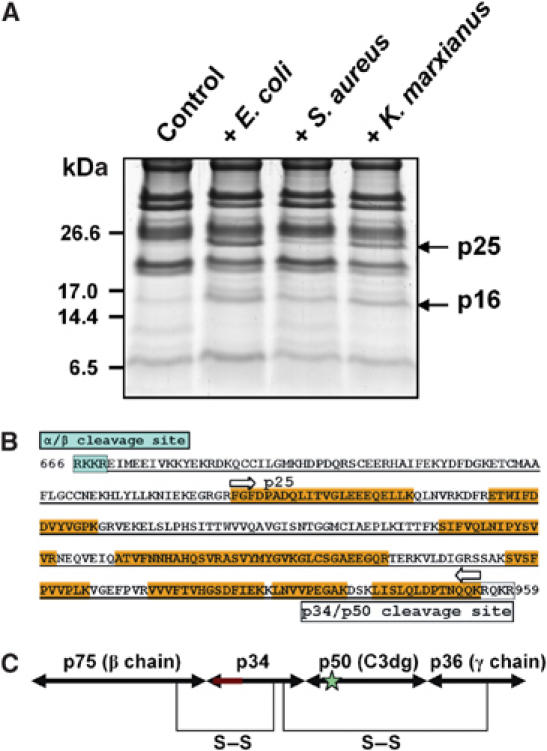

Pathogen-induced proteolytic production of anaphylactic peptide counterpart

Proteolytic activation of vertebrate C3/C4/C5 is accompanied by the release of proinflammatory anaphylactic peptides (C3a, C4a, and C5a). The finding of CrC3, CrC2/Bf, and PAMP-triggered trypsin-like activity led to our effort to determine whether a corresponding peptide, CrC3a, is released upon activation of CrC3. By comparing the C18 column-extracted polypeptides from the solution phase of naïve and microbe-incubated plasma samples, we isolated an induced protein of ∼25 kDa (p25) (Figure 7A). By mass spectroscopy (MS), p25 was identified to correspond to p34 devoid of the putative CrC3 anaphylactic peptide region, a vertebrate C3c fragment counterpart (Figure 7B). This suggests the proteolytic production of the peptide homolog of vertebrate C3a/C4a/C5a. Figure 7C shows the localization of the characterized fragments on CrC3, with the predicted interchain disulfide bridging pattern analogous to human C3. p75 is the β-chain counterpart of mature vertebrate C3. p50 appears to be the counterpart of the human C3dg with the thioester site, which is the terminal cleavage product of the attached C3b after proteolytic fragmentation by factor I (Davis et al, 1984). The potential p34/p50 cleavage site, the counterpart of human C3c/C3dg cleavage site of factor I, is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 7.

Smaller fragment (p25) of CrC3 appeared in the horseshoe crab plasma after incubation of plasma with representative microbes. (A) Profiles of polypeptides extracted through C18 minicolumn, from naïve and pathogen-treated plasma samples. Extracted polypeptides were resolved by tricine–SDS–PAGE. The samples derived from ∼0.5 ml each of plasma were loaded per lane. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue. The apparent pathogen-induced polypeptides (p25 and p16) were excised, in-gel digested with trypsin, and identified by MS. p25 was found to be a fragment of CrC3, while p16 was found to be a coagulin homolog. The implication of induction of p16 is not clear yet. (B) Position of p25 (C3c counterpart) in the predicted p34 region (underlined) of CrC3 (showing only the 666–959 position of the amino-acid sequence; see Figure 3). The peptide sequences from p25, which were identified by MS-MS, are highlighted in yellow. (C) An inferred organization of four CrC3 fragments constituting the complete CrC3 molecule. The predicted anaphylactic peptide region on p34 is marked red; the thioester site on p50 is marked with a star. The interchain disulfide bridging pattern is predicted based on the alignment of CrC3 with human C3.

It should be noted that p34 recovered from microbial surfaces retained the predicted ANATO domain, covering the vertebrate counterpart of anaphylactic peptide and C3c region. Thus, it appears that not all CrC3 molecules are further cleaved to release a homolog of C3a/C4a/C5a, indicating that the cleavage of the peptide is not required for the CrC3 attachment, unlike that in vertebrate system. Possibly, the cleavage at p34/p50 joint site rather than the C3a cleavage site by pathogen-triggered serine protease(s) causes the exposure of the thioester site for binding of CrC3 to the microbe. Further proteolytic processing of activated CrC3 releases CrC3a, a putative inflammation signal peptide.

Discussion

Hitherto, there is no documented consensus for the definition of the complement system (Nonaka and Yoshizaki, 2004a). The mammalian complement system, which was known first, is activated in three distinct activation pathways: classical, alternative, and the more recently identified lectin pathway (for most recent reviews and references cited therein, see Fujita et al, 2004; Nonaka and Yoshizaki, 2004a, 2004b). All the pathways merge at the key event, the proteolytic activation of the central component C3 to C3b, which covalently tags foreign microorganisms for engulfment by phagocytes. C3b deposit also triggers the lytic pathway, the MAC formation leading to the lysis of the pathogen. The antibody-mediated classical activation pathway and lytic terminal pathway only exist in the jawed vertebrates with adaptive immunity. In lower deuterostomes, only the opsonic phagocytosis has been reported.

Thus far, it is believed that the complement system originated in the deuterostome lineage, given the agreeable definition of the complement system with the presence of C3 and C3-opsonic phagocytosis (Nonaka and Yoshizaki, 2004a). It should be noted that complement-characteristic domains such as CCP, Netrin/C345C, von Willebrand factor (VWF), CUB, and Try_SP are not solely found in the complement components. However, it is the new combinations of these domains that rendered the appearance of procomplement components, which is believed to occur in the deuterostome lineage (Nonaka and Yoshizaki, 2004a). The functional evolution and integration of the primitive complement components led to the development of the ancient opsonic complement system. A minimal primitive complement system was proposed to contain lectin–protease (MASP) complex, C3, and its receptor (Fujita et al, 2004). In this proposal, MASP directly activates C3 instead of C2 or Bf, the C3-activating protease part in the modern complement activation pathways. Although C2/Bf was identified in the sea urchin and ascidian, the sophisticated mechanism of the alternative pathway to recognize a broad spectrum of pathogens is deemed to have developed more recently, while the possibility of a simple role of C2/Bf-like protein, as an amplifier of C3 deposition, cannot be excluded completely.

The findings in this study, including the homologs of vertebrate C3 and C2/Bf, the concurrent binding of CrC3 and plasma lectins (CL5s) to various microbes, and the LPS- and LTA-triggered Tryp_SP activity, suggest the existence in a primitive protostome lineage, of a sophisticated C3-centered opsonic defense system homologous to the complement system in the deuterostomes. TL5s/CL5s are structural homologs of vertebrate ficolin (Kairies et al, 2001), one of the two lectins (ficolin and MBL) that recognize foreign pathogens and initiate the activation of complement system in the lectin pathway (Gadjeva et al, 2001; Matsushita et al, 2001; Matsushita and Fujita, 2002). Another complement-like serine protease that might participate in the complement system of the horseshoe crab is the coagulation factor C (Cf) in the hemocytes (Muta et al, 1991; Ding et al, 1993). Cf is known to exhibit sequence homology to the complement factor C1r and C1s (Krem et al, 1999), and contains five CCP modules like CrC2/Bf, the sea urchin C2/Bf, and ascidian C2/Bf. Five CCP modules are believed to be present in the ancestral form of the vertebrate Bf/C2 (Zarkadis et al, 2001). More recently, we reported a Cf isoform, which is highly expressed in the hepatopancreas and possibly secreted into the plasma (Wang et al, 2003). Further supportive evidence for the existence of an opsonic complement system in the horseshoe crab comes from a C3 receptor cDNA sequence (Bui et al, unpublished data) that codes for a protein homologous to the receptor for C3dg in humans, which mediates phagocytosis by recognizing pathogen-attached C3dg. Finally, we also observed the in vivo and in vitro phagocytosis of S. aureus by the hemocytes of the horseshoe crab (Supplementary Figure 5). In vitro experiments also showed that the phagocytosis is inhibited by a complete cocktail of protease inhibitors and by EDTA, further supporting the lectin pathway activation of C3 opsonization. Taken together, our studies demonstrate the ancient origin of the key components of the complement system in the common ancestor of protostome and deuterostome. Whether these components were already integrated into a functional primitive complement system or separately in the two successor lineages remains to be determined. Interestingly, our recent studies (unpublished data) show the association of CrC2/Bf with the plasma lectin GBP (galactoside-binding protein), suggesting that CrC2/Bf may function as a vertebrate MASP counterpart, thus again supporting the lectin pathway of activation.

At this juncture, it is not clear whether CrC3 binds to microbial surfaces by covalent crosslink at the thioester site. However, the inhibition of the CrC3 attachment by HA showed the functional role of the thioester site in CrC3. Retrieval of fragments of CrC3 from the ‘bacterial beads' incubated with plasma does not preclude the possibility of covalent crosslinkage of CrC3 to the microbes. First, the ester bond is subject to spontaneous hydrolysis. The t1/2 reported of ester hydrolysis is 8 h for C3b-IgG and C3b-glycerol (Sahu and Pangburn, 1995). Second, the activated CrC3 may bind to the pathogen surface regardless of covalent crosslink. In this case, the exposed thioester of CrC3 would more likely be hydrolyzed rapidly by water than react with the hydroxyl or amine group nearby (Sepp et al, 1993; Gadjeva et al, 1998). Thus, the extracted CrC3 may represent the portion that is noncovalently attached to the microbial surface.

In our study, all tested microbes induce the production of p25, a vertebrate C3c fragment counterpart (Figure 7), which suggests proteolytic production of the homolog of the vertebrate C3a/C4a/C5a. Although the current approach has not extracted sufficient level of the putative CrC3a, possibly due to the instability of the peptide, further effort in the direct isolation of this putative peptide and analysis of its potential role in infection/proinflammation signaling are pertinent toward a definitive comparison with the vertebrate system.

The α2M in the horseshoe crab was speculated to have C3-like activity engaging a hemolytic mechanism (Enghild et al, 1990). However, the hemolytic activity was later attributed to a plasma lectin, limulin (Armstrong et al, 1998; Swarnakar et al, 2000). As a well-known broad-spectrum protease inhibitor in the horseshoe crab plasma, α2M possibly participates in the control of pathogen-triggered trypsin-like serine protease activity. While the complement system has become highly advanced and complex in mammals, it would not be surprising that the putative ancestral counterpart, which may constitute components not functionally integrated, had become obsolete in insects, in view of the lack of C3-like and C2/Bf-like genes in the sequenced genome of Drosophila melanogaster and Anopheles gambiae. Nevertheless, a nonclassical α2M-type TEP in mosquito A. gambiae (aTEP-1) was shown to promote the phagocytosis of Gram-negative bacteria (Levashina et al, 2001). It appears that in the mosquito, an opsonization mechanism has separately evolved out of the TEP. It would be pertinent to investigate whether this opsonization represents a widely deployed defense mechanism in insects or in even wider lineage range.

Although the in vivo functions of various isolated horseshoe crab lectins remain to be determined, the findings presented here provide an important platform to ultimately map the functional integration of the pathogen recognition and subsequent activation of defense mechanisms such as phagocytosis observed in this study, coagulation, and clearance of microbial invaders.

Materials and methods

Horseshoe crab hemolymph and microbial organisms

Horseshoe crabs, C. rotundicauda, were partially bled by cardiac puncture (Ding et al, 1993). Hemolymph was collected in sterile Falcon tubes in ice and centrifuged at 150 g for 10 min at 4°C. Cell-free plasma was transferred to new sterile tubes and further clarified by centrifugation at 30 000 g for 30 min. S. aureus (ATCC 25923), E. coli (ATCC 25922), and marine fungal isolate K. marxianus were used in this study. E. coli and S. aureus were cultured in Mueller Hinton Broth and K. marxianus was grown in 2% glucose, 2% bactopeptone, and 1% yeast extract (pH 5.6). For saturated cultures, S. aureus, E. coli, and K. marxianus were grown with shaking at 230 r.p.m. overnight at 37°C. For fresh cultures, 1:100 dilutions of overnight cultures were further shaken until the density of the cultures reached an OD600 nm of ∼0.5.

Characterization of immune proteins in the horseshoe crab plasma using live microbes as affinity matrix

For recovery of S. aureus-binding proteins, overnight culture of S. aureus was used. The ‘bacterial beads' were washed with 0.9% NaCl by repeated centrifugation at 12 000 g for 2 min each. The washed cells were thoroughly resuspended in a small volume of saline (<1/10 of original volume) and added to the plasma at the density of the original culture. After incubation with rotation at room temperature for ∼20 min, the ‘bacteria beads' were pelleted and washed three times with saline. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in a small volume of saline and subjected to extraction for 10–15 min with mild agitation in 1/5 the volume of original culture, under different conditions: (a) 4 M urea, in 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0; (b) 0.1 M citric acid, pH 2.0; and (c) 0.15 M triethylamine, pH 11.5. As control, bacterial cells were incubated in saline and subjected to the same treatments. Extracted proteins were concentrated by acetone precipitation and resuspended either in 4 M urea or directly in 1 × SDS–PAGE loading buffer. For the analysis of total protein extract of microbial cells that were incubated with horseshoe crab plasma, fresh cultures were used at 1:1 (v/v) with plasma, as described above. The washed cells were directly resuspended in SDS–PAGE loading buffer at 1/10 volume of original culture and boiled. To study the role of the internal thioester in CrC3 attachment, HA was added directly from 50% stock solution in water (∼16.84 M) into the plasma before incubation with washed bacterial cells (fresh culture). After SDS–PAGE analysis, the gels were stained with Coomassie blue R-250. Bands of interest were excised for further analysis.

Peptide extraction from naïve plasma and pathogen-treated plasma

C18 minicolumns (Amersham Biosciences) were used for the extraction of peptides, using the protocol provided. A 5 ml portion each plasma (naïve or pathogen-treated) was centrifuged to remove microbial cells, and applied to C18 minicolumn (containing 100 mg matrix). The bound peptides were eluted with 0.5 ml of 50% acetonitrile followed by 0.5 ml of 100% acetonitrile. The combined eluents were dried by vacuum and dissolved in 4 M urea. The peptide preparations were analyzed by tricine–SDS–PAGE (Schagger and von Jagow, 1987), and the gel was stained with Coomassie blue. The apparent pathogen-induced bands were excised for in-gel trypsin digestion and MS identification.

Protein identification by mass spectroscopy

In-gel trypsin digestion of recovered protein bands and subsequent extraction and desalting of peptides were carried out as described (Shevchenko et al, 1997). Peptide samples were subjected to either PMF analysis by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight with PerSeptive Biosystems Voyager DE-STR mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems), or peptide sequencing by tandem-MS-MS with Q-TOF2 mass spectrometer (Micromass). Database search of PMF was performed using MS-Fit at http://prospector.ucsf.edu/ucsfhtml4.0/msfit.htm . All complete or partial peptide sequences obtained by MS-MS were used for BLAST and MS-BLAST search (Shevchenko et al, 2001). BLAST searches for short-and-nearly-exact matches of peptide sequences were carried out at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). MS-BLAST search for homologs of a ‘pseudoprotein' constructed from peptide sequences was carried out at http://dove.embl-heidelberg.de/Blast2/msblast.html.

2D SDS–PAGE

Samples treated with SDS–PAGE loading buffer without reducing agent were resolved on a 1-mm-thick 7.5% SDS–PAGE gel in duplicate. At the end of the run, one lane of interest was excised for second-dimension resolution under reducing condition, and the rest of the gel was stained with Coomassie blue R-250 for comparison and alignment with markers. The excised lane was briefly washed with water and soaked in SDS–PAGE loading buffer with 1% 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) at 37°C for 1 h with agitation. Thereafter, the gel was overlaid on the stacking gel of a fresh 1.5-mm-thick SDS–PAGE gel of 10%, with the well filled up with loading buffer containing 1% 2-ME, and resolved into the second dimension. All the gels were stained by Coomassie blue.

Molecular characterization of CrC3 and CrC2/Bf

Hepatopancreas RNA was used for RT–PCR and RACE to procure CrC3 cDNA. Degenerate primers for RT–PCR were 5′-TT(C/T)GA(C/T)GA(C/T)GTITA(C/T)GTIG GICC(A/C/G/T)AA-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-TT(A/C/G/T)GCICC(C/T)TCIGGIAC(A/C/T /G)AC(C/T)TC-3′ (reverse primer), which were designed based on the p34 peptide sequences ETWLFDDVYVGPK and LNVVPEGAK, respectively. The RT–PCR product was cloned and sequenced. Thereafter, primary and nested RACE primers were designed to amplify the 5′ and 3′ ends of the cDNA using the SMART RACE kit (ClonTech). Specific amplified bands were gel-purified, cloned into TA cloning vector pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen), and sequenced. The full sequence of the CrC3 cDNA was obtained by assembling, in silico, the sequences of degenerate RT–PCR product and 5′ and 3′ RACE products. A cDNA fragment of CrC2/Bf, obtained from subtractive hybridization of hepatopancreas cDNA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected and naïve horseshoe crab, was used for the design of primers for 5′ and 3′ RACE of hepatopancreas cDNA. The full-length sequence of CrC2/Bf was obtained by assembling the RACE sequences in silico.

Phylogenetic analysis

Multiple sequence alignments were produced with Clustal X using Gonnet series protein weight matrix for the phylogenetic analyses of CrC3 and CrC2/Bf. Unrooted phylogenetic trees were constructed using neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987), based on the alignments. Bootstrap tests at 1000 replicates were carried out to examine the validity of the branching topologies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Figure 2

Supplementary Figure 3

Supplementary Figure 4

Supplementary Figure 5

Supplementary Table 1

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Q Lin and Ms Xianhui Wang for help with mass spectrometry, and Ms AN Yong for artwork with Figure 2C. This work was supported by a grant from the Agency for Science Technology and Research (A*STAR), Singapore.

References

- Armstrong PB, Melchior R, Swarnakar S, Quigley JP (1998) Alpha2-macroglobulin does not function as a C3 homologue in the plasma hemolytic system of the American horseshoe crab, Limulus. Mol Immunol 35: 47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azumi K, De Santis R, De Tomaso A, Rigoutsos I, Yoshizaki F, Pinto MR, Marino R, Shida K, Ikeda M, Ikeda M, Arai M, Inoue Y, Shimizu T, Satoh N, Rokhsar DS, Du Pasquier L, Kasahara M, Satake M, Nonaka M (2003) Genomic analysis of immunity in a Urochordate and the emergence of the vertebrate immune system: ‘waiting for Godot'. Immunogenetics 55: 570–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B (2004) Innate immunity: an overview. Mol Immune 40: 845–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SC, Yen CH, Yeh MS, Huang CJ, Liu TY (2001) Biochemical properties and cDNA cloning of two new lectins from the plasma of Tachypleus tridentatus: Tachypleus plasma lectin 1 and 2+. J Biol Chem 276: 9631–9639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AE III, Harrison RA, Lachmann PJ (1984) Physiologic inactivation of fluid phase C3b: isolation and structural analysis of C3c, C3d,g (alpha 2D), and C3g. J Immunol 132: 1960–1966 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding JL, Ho B (2001) A new era in pyrogen testing. Trends Biotechnol 19: 277–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding JL, Navas MAA, Ho B (1993) Two forms of factor C from the amoebocytes of Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda: purification and characterization. Biochim Biophys Acta 1202: 149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds AW, Law SK (1998) The phylogeny and evolution of the thioester bond-containing proteins C3, C4 and alpha 2-macroglobulin. Immunol Rev 66: 15–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enghild JJ, Thogersen IB, Salvesen G, Fey GH, Figler NL, Gonias SL, Pizzo SV (1990) Alpha-macroglobulin from Limulus polyphemus exhibits proteinase inhibitory activity and participates in a hemolytic system. Biochemistry 29: 10070–10080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T, Matsushita M, Endo Y (2004) The lectin-complement pathway—its role in innate immunity and evolution. Immunol Rev 198: 185–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman RM, Pistole TG (1976) Bactericidal activity of hemolymph from the horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus. J Invertebr Pathol 28: 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadjeva M, Dodds AW, Taniguchi-Sidle A, Willis AC, Isenman DE, Law SK (1998) The covalent binding reaction of complement component C3. J Immunol 161: 985–990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadjeva M, Thiel S, Jensenius JC (2001) The mannan-binding-lectin pathway of the innate immune response. Curr Opin Immunol 13: 74–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokudan S, Muta T, Tsuda R, Koori K, Kawahara T, Seki N, Mizunoe Y, Wai SN, Iwanaga S, Kawabata S (1999) Horseshoe crab acetyl group-recognizing lectins involved in innate immunity are structurally related to fibrinogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 10086–10091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S (2002) Pattern recognition receptors: doubling up for the innate immune response. Cell 111: 927–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JA, Kafatos FC, Janeway CA Jr, Ezekowitz RA (1999) Phylogenetic perspectives in innate immunity. Science 284: 1313–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hourcade DE, Wagner LM, Oglesby TJ (1995) Analysis of the short consensus repeats of human complement factor B by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem 270: 19716–19722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanaga S (2002) The molecular basis of innate immunity in the horseshoe crab. Curr Opin Immunol 14: 87–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kairies N, Beisel HG, Fuentes-Prior P, Tsuda R, Muta T, Iwanaga S, Bode W, Huber R, Kawabata S (2001) The 2.0-Å crystal structure of tachylectin 5A provides evidence for the common origin of the innate immunity and the blood coagulation systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 13519–13524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata S, Tsuda R (2002) Molecular basis of non-self recognition by the horseshoe crab tachylectins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1572: 414–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrell DA, Beutler B (2001) The evolution and genetics of innate immunity. Nat Rev Genet 2: 256–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krem MM, Rose T, Di Cera E (1999) The C-terminal sequence encodes function in serine proteases. J Biol Chem 274: 28063–28066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levashina EA, Moita LF, Blandin S, Vriend G, Lagueux M, Kafatos FC (2001) Conserved role of a complement-like protein in phagocytosis revealed by dsRNA knockout in cultured cells of the mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Cell 104: 709–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita M, Endo Y, Hamasaki N, Fujita T (2001) Activation of the lectin complement pathway by ficolins. Int Immunopharmacol 1: 359–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita M, Fujita T (2002) The role of ficolins in innate immunity. Immunobiology 205: 490–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R, Janeway CA Jr (2000) Innate immune recognition: mechanisms and pathways. Immunol Rev 173: 89–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R, Janeway CA Jr (2002) Decoding the patterns of self and nonself by the innate immune system. Science 296: 298–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muta T, Miyata T, Misumi Y, Tokunaga F, Nakamura T, Toh Y, Ikehara Y, Iwanaga S (1991) Limulus factor C. An endotoxin-sensitive serine protease zymogen with a mosaic structure of complement-like, epidermal growth factor-like, and lectin-like domains. J Biol Chem 266: 6554–6561 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka M, Yoshizaki F (2004a) Primitive complement system of invertebrates. Immunol Rev 198: 203–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka M, Yoshizaki F (2004b) Evolution of the complement system. Mol Immunol 40: 897–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistole TG, Britko JL (1978) Bactericidal activity of amoebocytes from the horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus. J Invertebr Pathol 31: 376–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu A, Pangburn MK (1995) Tyrosine is a potential site for covalent attachment of activated complement component C3. Mol Immunol 32: 711–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4: 406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schagger H, von Jagow G (1987) Tricine–sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem 166: 368–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepp A, Dodds AW, Anderson MJ, Campbell RD, Willis AC, Law SK (1993) Covalent binding properties of the human complement protein C4 and hydrolysis rate of the internal thioester upon activation. Protein Sci 2: 706–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A, Sunyaev S, Loboda A, Bork P, Ens W, Standing KG (2001) Charting the proteomes of organisms with unsequenced genomes by MALDI-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry and BLAST homology searching. Anal Chem 73: 1917–1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Mann M (1997) Peptide sequencing by mass spectrometry for homology searches and cloning of genes. J Protein Chem 16: 481–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LC, Azumi K, Nonaka M (1999) Complement systems in invertebrates. The ancient alternative and lectin pathways. Immunopharmacology 42: 107–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LC, Clow LA, Terwilliger DP (2001) The ancestral complement system in sea urchins. Immunol Rev 180: 16–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Størmer L (1952) Phylogeny and taxonomy of fossil horseshoe crabs. J Paleontol 26: 630–639 [Google Scholar]

- Sunyer JO, Zarkadis IK, Lambris JD (1998) Complement diversity: a mechanism for generating immune diversity? Immunol Today 19: 519–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarnakar S, Asokan R, Quigley JP, Armstrong PB (2000) Binding of alpha2-macroglobulin and limulin: regulation of the plasma haemolytic system of the American horseshoe crab, Limulus. Biochem J 347: 679–685 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckwell DS, Xu Y, Newham P, Humphries MJ, Volanakis JE (1997) Surface loops adjacent to the cation-binding site of the complement factor B von Willebrand factor type A module determine C3b binding specificity. Biochemistry 36: 6605–6613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenhofel WH, Shrock RR (1935) Invertebrate Paleontology. New York: McGraw-Hill [Google Scholar]

- Wang LH, Ho B, Ding JL (2003) Transcriptional regulation of a Limulus factor C: repression of an NFκB motif modulates its responsiveness to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Biol Chem 278: 49428–49437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarkadis IK, Sarrias MR, Sfyroera G, Sunyer JO, Lambris JD (2001) Cloning and structure of three rainbow trout C3 molecules: a plausible explanation for their functional diversity. Dev Comp Immunol 25: 11–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Figure 2

Supplementary Figure 3

Supplementary Figure 4

Supplementary Figure 5

Supplementary Table 1