Abstract

The cytosolic coat protein complex II (COPII) mediates vesicle formation from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and is essential for ER-to-Golgi trafficking. The minimal machinery for COPII assembly is well established. However, additional factors may regulate the process in mammalian cells. Here, a morphological COPII assembly assay using purified COPII proteins and digitonin-permeabilized cells has been applied to demonstrate a role for a novel component of the COPII assembly pathway. The factor was purified and identified by mass spectrometry as Nm23H2, one of eight isoforms of nucleoside diphosphate kinase in mammalian cells. Importantly, recombinant Nm23H2, as well as a catalytically inactive version, promoted COPII assembly in vitro, suggesting a noncatalytic role for Nm23H2. Consistent with a function for Nm23H2 in ER export, Nm23H2 localized to a reticular network that also stained for the ER marker calnexin. Finally, an in vivo role for Nm23H2 in COPII assembly was confirmed by isoform-specific knockdown of Nm23H2 by using short interfering RNA. Knockdown of Nm23H2, but not its most closely related isoform Nm23H1, resulted in diminished COPII assembly at steady state and reduced kinetics of ER export. These results strongly suggest a previously unappreciated role for Nm23H2 in mammalian ER export.

INTRODUCTION

Assembly of the coat protein complex II (COPII) coat at specialized regions of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), termed the transitional ER, fulfills two critical functions necessary for protein export from the ER (Bannykh and Balch, 1997). As it assembles, the coat sorts secretory cargo, cargo receptors, and transport factors into the bud, and it deforms the phospholipid bilayer into 60-nm ER-derived transport vesicles (Antonny and Schekman, 2001; Bonifacino and Glick, 2004). Three cytosolic factors and one integral membrane protein comprise the minimal machinery for vesicle formation from the ER (Barlowe et al., 1994): the Sar1p GTPase, which binds directly to the lipid surface of the ER to initiate COPII assembly (Nakano and Muramatsu, 1989; Barlowe et al., 1993); Sec12p, an integral ER membrane protein that facilitates exchange of GTP for GDP on Sar1p (Barlowe and Schekman, 1993); and two large heteromeric coat protein complexes, Sec23/24p (Hicke and Schekman, 1989) and Sec13/31p (Salama et al., 1993, 1997), which bind sequentially to ER exit sites once Sar1p has bound and been activated to the GTP-bound form (Matsuoka et al., 1998). Sar1p and Sec24p participate directly in the cargo selection process, forming prebudding complexes with cargo, cargo receptors, and vSNAREs (Aridor et al., 1998; Kuehn et al., 1998; Springer and Schekman, 1998; Votsmeier and Gallwitz, 2001; Miller et al., 2003; Mossessova et al., 2003), whereas membrane deformation and the completion of vesicle formation depend on the subsequent binding and polymerization of Sec13/31p (Matsuoka et al., 1998; Lederkremer et al., 2001; Matsuoka et al., 2001). Coat disassembly requires GTP hydrolysis on Sar1p that is stimulated by the coat itself: Sec23p is the GTPase activating protein (GAP) for Sar1p (Yoshihisa et al., 1993), and Sec13/31p further activates the GAP activity of Sec23p by 10-fold (Antonny et al., 2001).

Although a detailed understanding of the minimal ER export machinery has been achieved, key questions concerning the mammalian mechanism of COPII vesicle formation remain unanswered. The unresolved issues include 1) how the sites of vesicle formation at discrete, restricted subdomains of the ER are determined (Bannykh et al., 1996; Hammond and Glick, 2000; Stephens, 2003); 2) the lipid requirements for COPII assembly (Matsuoka et al., 1998; Pathre et al., 2003), whether the polymerization of Sec13/31p on the prebudding complex fully accounts for the membrane curvature and scission required to pinch off an ER-derived transport carrier; and 4) what role, if any, the cytoskeleton plays. These and other unanswered questions suggest the existence of unidentified factors and steps in mammalian COPII assembly.

Possibly relevant to the unresolved issues are the additional regulatory components that have been implicated in COPII assembly. The first is Sec16p, a multidomain protein found in yeast that interacts with multiple COPII subunits and has been hypothesized to function as a scaffold for coat assembly (Espenshade et al., 1995) as well as to stabilize the coat against the destabilizing affects of GTP hydrolysis (Supek et al., 2002). The second is Sed4p, a Sec12p homologue that may inhibit GTP hydrolysis on Sar1p (Saito-Nakano and Nakano, 2000). The third is Yip1p, an integral membrane protein required for COPII vesicle formation through an unknown mechanism (Tang et al., 2001; Heidtman et al., 2003). Finally p97, a member of the NSF family of AAA ATPases (Brunger and DeLaBarre, 2003), has been proposed to function together with its cofactor p47, in transitional ER biogenesis and/or ER export (Roy et al., 2000); however, its function in ER export is controversial (Dalal et al., 2004). Interestingly, although the minimal machinery for COPII vesicle formation is highly conserved, mammalian orthologues of Sec16p and Sed4p have not yet been identified.

Compared with the relative simplicity of the identified machinery for COPII vesicle formation, the multitude of factors implicated in the formation of clathrin-coated vesicles from the plasma membrane seems inordinately complex (Kirchhausen, 2000; Slepnev and De Camilli, 2000; Aridor and Traub, 2002; Conner and Schmid, 2003). It can be argued that the large number of factors required for endocytosis reflects a requirement for the sorting of a large number of cell surface receptors, as well as the fact that the plasma membrane poses special challenges for vesicle formation due to the unique properties of the organelle. However, it also can be argued that some of the additional players required for endocytosis reflect requirements that might be more general. For instance, membrane phosphoinositide production, thought to increase the avidity of coat adaptors to cargo at sites of vesicle formation, plays an important role not only at the plasma membrane (Wenk and De Camilli, 2004) but also at the trans-Golgi network (TGN) (Wang et al., 2003). In addition, dynamin and dynamin-like proteins are required for the final fission not only of multiple types of vesicles and carriers from the plasma membrane (Hinshaw, 2000) but also at the TGN as well as mitochondria and peroxisomes (Praefcke and McMahon, 2004). Finally, recent work shows that transient actin assembly and disassembly plays a critical role in the formation of coated vesicles not only from the plasma membrane (Schafer, 2002; Engqvist-Goldstein and Drubin, 2003) but also from the TGN (Carreno et al., 2004).

Because the minimal cytosolic machinery required for COPII assembly is well established, we reasoned that an in vitro morphological COPII assembly assay using purified COPII proteins and semiintact cells might provide a powerful system for the identification of additional membrane- or cytoskeleton-associated regulators. Here, we report the characterization and use of one such assay to purify and identify Nm23H2, one of eight isoforms of nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK) (Lacombe et al., 2000), as a factor that promotes COPII assembly and ER export in mammalian cells. Relevant to our findings, Nm23H1, an NDK isoform closely related to Nm23H2, has recently been implicated in endocytosis (Krishnan et al., 2001; Palacios et al., 2002) and hypothesized to play a central role during endocytosis to link Arf6 to the fission and actin machineries (Di Fiore and De Camilli 2001). Our identification of Nm23H2 as a positive factor for ER export raises the possibility that members of the NDK family may act at multiple points in the secretory and endocytic pathways to regulate vesicle formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Antibodies

Yeast COPII proteins, purified as described previously (Shimoni and Schekman 2002), and rabbit antiserum against yeast Sec24p (Shimoni et al., 2000), were kindly provided by R. Schekman (University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA). Digitonin, from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany), was maintained as a 20 mg/ml stock in dimethyl sulfoxide at –20°C. Defatted bovine serum albumin (BSA), the polyclonal antibody against Nm23H1, and all reagents used in the nucleoside diphosphokinase assay were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Affinity-purified rabbit antibody against mammalian Sec13p was kindly provided by B. L. Tang and W. Hong (National University of Singapore, Singapore). A rabbit serum against human Sec13p also was raised at Covance (Princeton, NJ) by using a GST-Sec13 fusion protein as antigen, depleted of glutathione S-transferase (GST) antibodies on a GST column, and affinity purified on a GST-Sec13 column. The Nm23H2 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (KM1121) was from Kamiya (Seattle, WA), the polyclonal antibody against βCOP was from ABR (Golden, CO), the polyclonal antibody against calnexin was from StressGen (Victoria, British Columbia, Canada), and the mAb against the 6-His eptitope was from QIAGEN (Valencia, CA). Fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Zymed Laboratories (South San Francisco, CA). OligofectAMINE and Opti-MEM were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Cell Culture

Normal rat kidney (NRK) cells and HeLa cells stably expressing GalNacT2-GFP (provided by J. White, Cancer Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA) were maintained in DMEM and minimal essential medium (MEM), respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

COPII Assembly Assay

NRK cells were grown to 50% confluence on 12-mm glass coverslips for at least 18 h before the assay. For the assay, each coverslip was placed briefly into one well of a 24-well plate containing 1 ml of permeabilization buffer [PB; 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 125 mM KOAc, 2.5 mM Mg(OAc)2, and 5 mM EGTA] before permeabilization. Each coverslip was then placed in 0.5 ml of PB + 30 μg/ml digitonin + 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) + 1 μg/ml pepstatin + 1 μg/ml leupeptin at room temperature (RT). After 6 min, each coverslip was transferred to 1 ml of ice-cold PB (or PB + 1 M KCl) containing 1 mM DTT. After one change of the same buffer, the cells were left on ice for an additional 20 min. After the incubation, each coverslip was washed with 1× 1 ml of ice-cold PB + 1 mM DTT, and 1× 1 ml of transport buffer [TB; 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 250 mM sorbitol, 70 mM KOAc, and 1 mM Mg(OAc)2] + 1 mM DTT. After draining the excess buffer onto a Kimwipe, each coverslip was placed on a Parafilm-lined petri dish, and 50 μl of the specified reaction mix was immediately placed onto each coverslip. Typically, the reaction mix, in TB + 1 mM DTT + 1 μg/ml pepstatin + 1 μg/ml leupeptin, contained 1 μg/ml Sar1p, 3 μg/ml Sec23/24p, 7 μg/ml Sec13/31p, and 1 mg/ml defatted BSA as a carrier protein, 500 μM guanosine 5′-O-(3-thio)triphosphate (GTPγS), and an ATP-regenerating system (0.5 mM ATP, 0.5 mM UTP, 50 μM GTP, 5 mM creatine phosphate, 25 μg/ml creatine phosphokinase, 0.05 mM EGTA, and 0.5 mM MgCl2). After 10 min at 32°C, the coverslips were placed in 3% paraformaldehyde and processed for indirect immunofluorescence as described previously using a rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody (Lee and Linstedt, 1999). HeLa cytosol was prepared as described previously (Lee and Linstedt, 2000).

Quantification of COPII Assembly

After fixing and staining using a rabbit serum against Sec24p and rhodamine- anti-rabbit IgG, Sec24p-positive structures were visualized using a Nikon fluorescence microscope equipped with a 40× oil immersion lens (numerical aperture [NA] 1.3), and images were captured using an 8 bit Hamamatsu charge-coupled device camera. Every image in an experiment was acquired using the same integration time. To quantify the total Sec24p fluorescence in peripheral structures, five representative fields (each containing 5–10 cells) from each sample coverslip were captured in Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA) and analyzed in NIH Image. Background was subtracted using the most common extracellular pixel value. Thresholding was performed using the original gray scale image of a number of captured images from the same experiment as the standard, to maximize inclusion of all discernible objects. A single background value and threshold value was applied to all of the images from a single experiment. The total fluorescence, in all resolvable objects <1 μm in diameter, in each field was quantified and divided by the number of cells to obtain the average peripheral fluorescence per cell.

Purification of Restorative Activity

One adult rabbit liver with a wet weight of 120 g was washed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), minced using a razor blade, and washed with 150 ml of buffer A [20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 150 mM KOAc, 1 mM Mg(OAc)2]. This and all other buffers used throughout the purification had 1 mM DTT, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin. After homogenization in 150 ml of buffer A by using a tissue grinder, the homogenate was subjected first to low-speed centrifugation in an SA600 rotor at 2500 rpm for 15 min, followed by centrifugation in a Ti70 rotor at 50,000 rpm for 90 min. The resulting supernatant, 120 ml containing 3.6 g of protein, was dialyzed against buffer A, cleared by centrifugation (50,000 rpm, Ti70, 60 min), and loaded onto a 70-ml DEAE-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) column in buffer A. The flowthrough, containing the majority of the activity, was precipitated with 50% ammonium sulfate. The supernatant, containing the majority of the activity, was further precipitated with 80% ammonium sulfate. The 50–80% precipitate, containing 1.2 g of protein and the majority of the activity, was resuspended in 120 ml of buffer B [50 mM MES, pH 6.5, 25 mM NaCl, 1 mM Mg(OAc)2], dialyzed against buffer B, cleared by centrifugation (50,000 rpm, Ti70, 60 min), and loaded onto a 25 ml of SP-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) column in buffer B. The majority of the activity, eluting with buffer B + 100 mM NaCl and containing 88 mg of protein, was precipitated with saturating ammonium sulfate and resuspended in 12 ml of buffer C [25 mM KHPO4, pH 6.8, and 1 mM Mg(OAc)2] and dialyzed against buffer C. After clearing by centrifugation (50,000 rpm, TLA100.3, 30 min), the dialysate was loaded onto a 15-ml hydroxyapatite HT (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) column in buffer C. After washing with buffer C + 125 mM KHPO4, 40 mg containing ∼50% of the activity was eluted with 250 mM KHPO4, and 10 mg containing ∼50% of the activity was eluted with 500 mM KHPO4. The 500 mM KHPO4 eluate, more highly enriched for the activity, was precipitated with saturating ammonium sulfate, resuspended in 6 ml of buffer D (20 mM Tris, pH 7.0, 0.1 mM EGTA, and 0.1 mM EDTA), and dialyzed against buffer D. After clearing by centrifugation (50,000 rpm, TLA100.3, 30 min), the dialysate, containing 5.5 mg, was loaded onto a 1.5-ml GTP agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) column in buffer D. After washing in buffer D, 0.8 mg containing the activity was eluted with buffer D + 5 mM GMP. The GMP eluate was dialyzed against buffer E [50 mM MES, pH 6.5, 25 mM NaCl, and 1 mM Mg(OAc)2] and loaded directly onto a 1-ml monoS HR5/5 column (Amersham Biosciences). The activity was eluted using a 20-ml linear gradient between buffer E and buffer E + 155 mM NaCl. The peak of activity, eluting between 75 and 115 mM NaCl and containing 0.2 mg, was concentrated to 0.2 ml in a C-30 Centricon (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and loaded directly onto an S200 HR10/30 gel filtration column (Amersham Biosciences). One-milliliter fractions were collected and analyzed for activity. Fifty microliters of each included fraction was precipitated with 25% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) by using 0.5% Triton X-100 as a carrier, resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by silver stain. For identification by mass spectrometry, fractions 13 and 14 were pooled, TCA precipitated, and resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE. The major copurifying ∼17- to 20-kDa polypeptide, as well as a minor ∼40-kDa polypeptide, was excised from the gel and trypsinized. Mass fingerprinting of tryptic peptides was carried out using a Voyager model DE-STR matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) instrument (PerkinElmerSciex Instruments, Boston, MA), and analysis of the tryptic mass fingerprint spectra was carried out using the Mascot data-mining program (Perkins et al., 1999). Protein assays were performed using the Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad).

Recombinant 6-His-Nm23H2

Human Nm23H2 was polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified from a HeLa cDNA pool by using the following primers: 5′CTAGCTAGCATGGCCAACCTGGAGCGCACC3′ and 5′GGAATTCTTATTCATAGACC CAGTCATGAGC3′. After digestion with NheI and EcoRI, the fragment was cloned into the NheI and EcoRI sites in pRSETB (Invitrogen), just downstream of the polyhistidine tag. The catalytically inactive version of Nm23H2(H118C) was generated using the QuikChange kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). For protein expression, plasmids were transformed into BL21plysS. Cells were grown at 25°C to mid-log phase (OD0.5). Expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside at 25°C. After 4 h, cells were harvested, washed in PBS, and frozen in liquid N2. Cells (from 1 liter) were lysed by thawing in 10 ml of lysis buffer, sonicated, and cleared by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 30 min (SA600). Each supernatant was added to 0.5 ml of Ni+2-NTA beads and incubated at 4°C for 2 h. After binding, beads were washed with 2 × 10 ml of lysis buffer followed by 2 × 10 ml of wash buffer. The protein was eluted in 0.5-ml fractions with elution buffer. All buffers were as specified by QIAGEN. Eluates were dialyzed into 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 150 mM KOAc, and 1 mM MgOAC.

Nucleoside Diphosphokinase Assay

Enzyme activity was assay spectrophotometrically precisely as described previously (Agarwal, 1978) by following the formation of ADP from ATP in a coupled pyruvate-lactate dehydrogenase system containing dTDP, NADH, phosphoenol pyruvate, lactate dehydrogenase, and pyruvate kinase. The rate of NADH oxidation was followed by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm. One unit of nucleoside diphophokinase activity was defined as the amount of activity required to oxidize 1 μm of NADH/min/ml.

Ammonium Sulfate Fractionation of Rat Liver Cytosol

Solid ammonium sulfate was added slowly to 30 ml of diluted rat liver cytosol (1 mg/ml) with constant stirring to 30% saturation. After 30 min at 4°C, the precipitate (0–30%) was collected by centrifugation (10 krpm, 30 min, SA600). Additional ammonium sulfate was added to the supernatant to 80% saturation, and the resulting precipitate (30–80%) was collected as described above. Each pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of buffer A + 1 mM DTT + protease inhibitors and dialyzed against the same buffer. The 0–30% fraction contained 10% of the starting protein, and the 30–80% fraction contained 90% of the starting protein. The 0–30% fraction was diluted with an equal volume of buffer and spiked with 1 μg/ml yeast Sar1p for the COPII assembly assay.

Short Interfering RNA Tranfections

Cells were transfected twice to achieve maximally effective knockdown. Approximately 3 × 105 HeLa cells stably expressing GalNacT2-GFP (Storrie et al., 1998) were seeded onto a 10-cm dish before the day of transfection. Thirty minutes before the transfection, cells were washed with PBS, and the medium was replaced with 8 ml of MEM containing 10% FBS but no antibiotics. For each 10-cm dish, 16 μl of siRNA (to achieve a final concentration of 50 nM) was added to a tube containing 800 μl of Opti-MEM. In a second tube, 32 μl of OligofectAMINE was added to 192 μl of Opti-MEM. The siRNA/Opti-MEM mixture was added dropwise to the OligofectAMINE/Opti-MEM mixture and incubated at RT. After 30 min, 640 μl of Opti-MEM was added to the siRNA/OligofectAMINE/Opti-MEM mixture and the final solution was added to the cells. Twenty-four hours after the first transfection, the cells were trypsinized and seeded in normal medium at the above-indicated confluence either into 35-mm dishes (for subsequent immunoblot analysis) or onto 12-mm glass coverslips in individual wells of a 24-well plate (for subsequent immunofluorescence analysis). After 24 h, the second transfection was performed. The procedure for the second transfection was precisely that described for the first, except that the volumes were adjusted accordingly. Fresh MEM + 10% FBS (one-third volume) was added to the cells each day after transfection, and the cells were always analyzed on the third day after the second transfection.

siRNA Synthesis

All siRNAs were generated using the siRNA construction kit from Ambion (Austin, TX). Two siRNAs (14 and 24) were made against the following target sequences in Nm23H2: AATCCAGCAGATTCAAAGCCA and AACTGGTTGACTACAAGTCTT, respectively. The control siRNAs used herein consisted of the sequence AAGGGCTTCAAGTTGGTGGCG or AAGAGCTAACAATTGCTGGAA.

Immunoblot Analysis

Each 35-mm dish was washed with PBS, and the cells were solubilized with 100 μl of lysis buffer (1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA). After scraping, the lysate was boiled for 10 min, passed five times through a 25-gauge needle, and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g. After determining the protein concentration in each lysate by using the bicinchoninic acid reagent (Pierce Chemical), 100 μg of each lysate was resolved by SDS-PAGE. Transfer and immunoblot conditions were as described previously (Lee and Linstedt, 1999). Antibody binding was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce Chemical), and image capture was with the Fuji-film LAS-3000 imaging system. The level of knockdown was quantified by comparison to a standard curve generated using known amounts of untreated lysate.

Confocal Microscopy

Determination of steady state levels of COPII assembly and Golgi association of βCOP in siRNA-treated cells was performed using a 3-line LCI (spinning disk confocal scan head equipped with independent excitation and emission filter wheels; PerkinElmer Optoelectronics, Freemont, CA) mounted on an Axiovert 200 microscope with a 100× (1.4 NA) apochromat objective (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) and driven by the UltraVIEW software (PerkinElmer Optoelectronics). A 12-bit Hamamatsu Orca-ER camera was used to capture images. Identical exposure times and laser output levels were used for all samples within an experiment. Six optical sections covering the entire height of the cells (∼0.4-μm step size) through each field were captured and projected (maximum value) to generate single images. For analysis of COPII, the images were imported into and analyzed in NIH Image. After thresholding using a single threshold value for all images, the total object fluorescence in each field was determined and divided by the number of cells in the field. For analysis of βCOP, the projected images were merged and analyzed in Adobe Photoshop. The Golgi region of each cell was selected in the GalNacT2 channel by using the wand tool, and the ratio of βCOP/GalNacT2-GFP fluorescence was obtained accordingly.

RESULTS

An In Vitro Morphological Assay Using Purified COPII Proteins Reconstitutes COPII Assembly at ER Exit Sites in Mammalian Cells

In an effort to identify potentially novel, peripheral membrane components involved in COPII vesicle formation, we used an established morphological, permeabilized cell assay for COPII assembly (Plutner et al., 1992). This assay, using either crude cytosol or purified COPII proteins, has previously been demonstrated to generate cargo containing COPII vesicles at the EM level (Bannykh et al., 1996; Aridor et al., 1998). Nonetheless, before using the assay, we first established that the requirements of our assay recapitulated the established requirements. NRK cells grown on glass coverslips were permeabilized with 30 μg/ml digitonin and washed for 20 min at 4°C in the absence of nucleotides, as described previously (Plutner et al., 1992; Lee and Linstedt, 2000), to remove endogenous COPII components. The cells were subsequently incubated with purified COPII proteins in the presence of 0.5 mM GTPγS and an ATP-regenerating system at 32°C for 10 min. GTPγS, in 10-fold molar excess over the GTP present in the ATP-regenerating system, was used to lock Sar1p in the activated state so as to minimize subsequent Sec23/24p- and Sec13/31p-mediated disassembly of the coat (Antonny et al., 2001). In previously described assays, GTPγS did not inhibit COPII vesicle formation and fission, although it seemed to impair the final separation of vesicles from one another (Bannykh et al., 1996). Yeast COPII proteins were used in the assay because they provide a highly characterized and purified source of COPII (Shimoni and Schekman 2002), share a high degree of sequence similarity to their mammalian counterparts, and have been shown to form bona fide COPII vesicles from mammalian microsomes (Espenshade et al., 2002). The levels of COPII proteins used herein are below saturation levels but have been shown to efficiently drive vesicle formation from yeast ER microsomes (Barlowe et al., 1994).

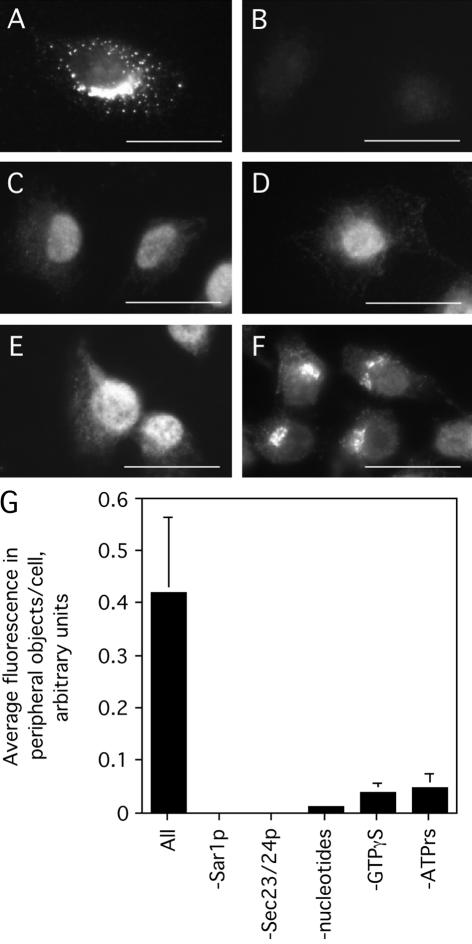

After paraformaldehyde-fixation, the assembly of exogenously added COPII at ER exit sites was visualized with a standard immunofluorescence procedure by using an antibody against yeast Sec24p. Under these conditions, COPII assembly was robust (Figure 1A). Strong staining was observed in the juxtanuclear region as well as at peripheral sites. This distribution is consistent with a previous EM analysis demonstrating roughly one-half of ER export complexes in NRK cells to be juxtanuclear and adjacent to the cis-face of the Golgi, and the other half to be distributed at peripheral ER exit sites (Bannykh et al., 1996). The Sec24p staining observed could be attributed to the exogenously added Sec24p because omission of Sec23/24p from the incubation abolished all detectable immunoreactivity with the Sec24p antibody (Figure 1B). As expected, only a background level of nuclear staining was observed when Sar1p was omitted (Figure 1C). Also as expected, no specific Sec24p-positive structures were generated in the absence of nucleotides (Figure 1D). GTPγS, presumably to lock Sar1p in the activated state, was essential for the accumulation of Sec24p-positive structures (Figure 1E). Finally, as predicted from previous studies (Aridor et al., 1998; Aridor and Balch, 2000), omission of ATP greatly reduced the overall extent of COPII assembly (Figure 1F). Quantification of the total fluorescence in peripheral objects per cell generated under each condition indicated a requirement in the COPII assembly assay for Sar1p, Sec23/24p, and GTPγS, as well as ATP (Figure 1G). Interestingly, although omission of the ATP-regenerating system resulted in a loss of peripheral Sec24p-positive structures, a low level of residual juxtanuclear staining that overlapped with the Golgi was consistently observed (Figure 1F). Whether this residual staining, significantly less than the juxtanuclear staining observed in the presence of ATP (Figure 1A), reflects a background level of COPII assembly or a subpopulation of ATP-independent ER exit sites remains unknown.

Figure 1.

A COPII assembly assay using purified COPII components. Digitonin-permeabilized NRK cells were incubated with 1 μg/ml Sar1p, 3 μg/ml Sec23/24p, 7 μg/ml Sec13/31p, 1 mg/ml defatted BSA, 500 μM GTPγS, and an ATP-regenerating system (ATP r.s.) for 10 min at 32°C (A). In B–F, Sec23/24p (B), Sar1p (C), all nucleotides (D), GTPγS only (E), or the ATP r.s. only (F) was omitted from the reaction. Cells were fixed and stained using a rabbit serum against Sec24p. Bar, 10 μm. (G) Quantification (see Materials and Methods), mean ± SEM, of the average peripheral fluorescence per cell (>25 cells) resulting from each omission

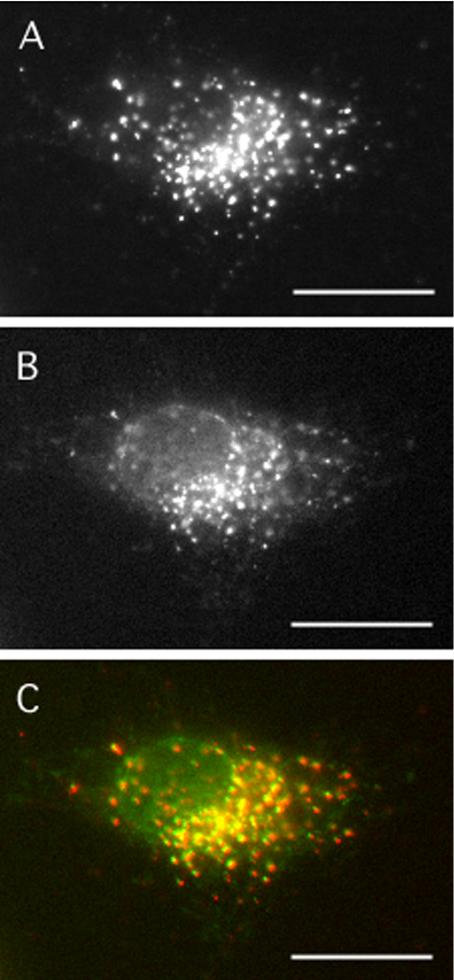

Finally, whether the COPII assembly that occurred in the assay was localized to bona fide ER exit sites was determined. To mark ER exit sites, NRK cells were treated with brefeldin A (BFA) and the kinase inhibitor H89 to redistribute Golgi proteins into the ER (Puri and Linstedt, 2003). Thereafter, cells were washed briefly into normal medium in the absence of drug. Under these conditions in intact cells, a subset of Golgi proteins emerge synchronously at peripheral ER exit sites, as marked by Sec13p staining, before participating in reformation of the Golgi apparatus (Puri and Linstedt, 2003). As expected, COPII assembly was robust in cells permeabilized at early times of Golgi emergence (Figure 2A), and nearly all Sec24p-positive structures generated in the assay were either coincident with or adjacent to structures containing giantin (Figure 2B, merged image in C). The relationship between giantin and the Sec24p-positive structures generated in the assay also was reminiscent of the previously reported relationship between giantin and Sec13p in intact cells upon BFA treatment and washout in the presence of nocodazole (Hammond and Glick, 2000). Thus, the majority of Sec24p-positive structures generated in the assay seem to be localized to bona fide ER exit sites.

Figure 2.

Purified COPII proteins assemble at bona fide ER exit sites. To collapse Golgi proteins into the ER, NRK cells were incubated with 2.5 μg/ml BFA for 20 min, followed by 2.5 μg/ml BFA + 100 μM H89 for 10 min. After five washes into normal medium at RT, cells were digitonin permeabilized and incubated with 1 μg/ml Sar1p, 3 μg/ml Sec23/24p, 7 μg/ml Sec13/31p, 1 mg/ml BSA, 500 μM GTPγS, and an ATP-regenerating system (ATP r.s.) for 20 min at 32°C. Cells were fixed and doubly stained using a rabbit serum against Sec24p (A) and a mAb against giantin (B). The merged image with Sec24p in red and giantin in green is shown (C). Bar, 10 μm.

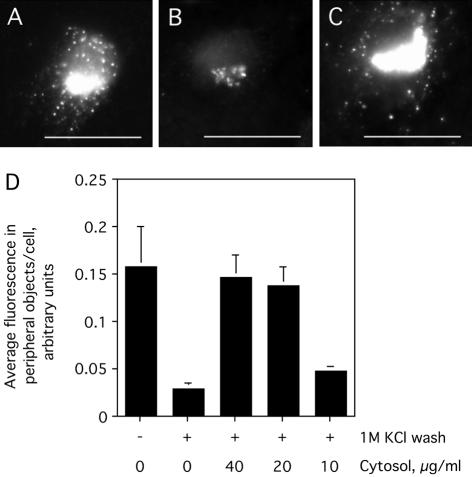

A Salt-Extractable Activity Facilitates COPII Vesicle Formation at Peripheral ER Exit Sites

Having validated the assay for COPII assembly, we next asked whether the removal of peripherally associated factors would impact the subsequent assembly of purified COPII at ER exit sites. Indeed, COPII assembly was dramatically reduced when the permeabilized cells were first washed with 1 M KCl (compare Figure 3B to A), although a low level of residual juxtanuclear Sec24p staining, similar to that seen in the absence of ATP (Figure 1F), was consistently observed in salt-washed cells (Figure 3B). Importantly, the salt wash did not irreversibly inactivate ER exit sites, because COPII assembly at both peripheral and juxtanuclear sites was restored to the levels in control, nonsalt-washed cells (Figure 3A), by the addition of diluted HeLa cell cytosol (Figure 3C). The salt wash inhibition as well as the extent of restoration of peripheral COPII assembly by varying cytosol concentrations is shown (Figure 3D). Provision of a relatively low dilution of cytosol (20 μg/ml) was sufficient to fully restore COPII assembly. Together, these observations suggested a positive role for a previously undescribed cytosolic factor, peripherally associated with membrane and/or cytoskeletal elements, in mammalian COPII assembly.

Figure 3.

Salt-wash inhibition of COPII assembly and restoration by a cytosolic factor. Digitonin-permeabilized NRK cells were washed with 70 mM KOAc (A) or 1 M KCl (B and C) and incubated with purified COPII proteins (as in Figure 1), 500 μM GTPγS, and an ATP-regenerating system (ATP r.s.) in the absence (A and B) or presence (C) of 40 μg/ml HeLa cytosol. After incubation for 10 min at 32°C, cells were fixed and stained using antibodies against Sec24p. Bar, 10 μm. Quantification of the average peripheral fluorescence per cell (>25 cells), mean ± SEM, under each of the indicated conditions is shown (D).

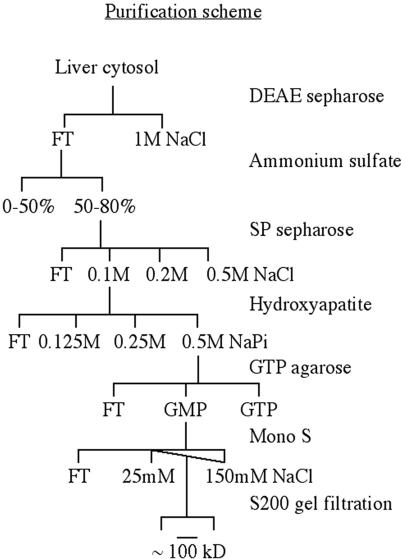

Purification of the Restorative Activity and Its Identification as Nm23H2

To identify the putative salt-extractable factor(s), we undertook its purification from rabbit liver cytosol. One unit per milliliter was defined as the lowest dilution of the activity that would enable purified COPII proteins to assemble at ER exit sites of digitonin-permeabilized and salt-washed cells in the presence of both GTPγS and an ATP-regenerating system. Sequential chromatography over DEAE-Sepharose, SP-Sepharose, hydroxyapatite, GTP agarose, and monoS led to a nearly 10,000-fold purification of the restorative activity with respect to protein (Figure 4 and Table 1).

Figure 4.

Purification procedure used to isolate the restorative activity from cytosol.

Table 1.

Purification of restorative activity from cytosol

| Step | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (u) | Specific activity (u/mg) | Fold purification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytosol | 3600 | 15,120 | 4.2 | 1 |

| DEAE/AS | 1200 | 30,000 | 10 | 2.4 |

| SP | 88 | 33,000 | 750 | 178 |

| HA | 10 | 18,000 | 1800 | 428 |

| GTP | 0.8 | 16,200 | 20,250 | 4821 |

| monoS | 0.2 | 8100 | 40,500 | 9642 |

The cytosolic activity required for COPII assembly in salt-washed cells was purified by sequential chromatography as described in Figure 4 and Materials and Methods.

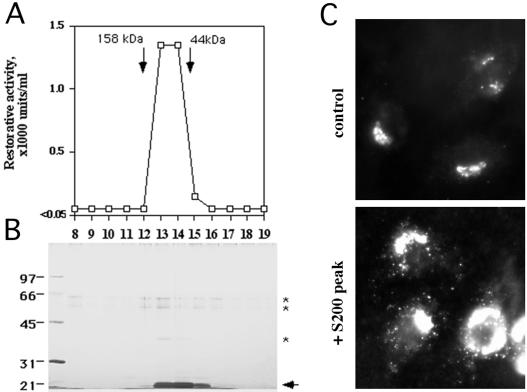

The peak of activity from the monoS column was subjected to a final sizing step on an S200 gel filtration column. The activity profile is shown in Figure 5A, and the extent to which the S200 peak restored COPII assembly in salt-washed cells can be seen in Figure 5C. The addition of the purified S200 peak (Figure 5C, bottom) significantly stimulated, at both peripheral and juxtanuclear exit sites, the generation of Sec24p-positive structures over the control that lacked the restorative activity (top). SDS-PAGE and silver stain analysis of the active fractions after the S200 step (Figure 5B) showed only one major polypeptide of 17–20 kDa (arrowhead), near the dye front, copurifying with the restorative activity. A minor polypeptide of ∼40 kDa (asterisk) whose abundance was comparable with that of the contaminating keratins present in all fractions (asterisks at ∼55 and ∼65 kDa) also was observed. The polypeptides were trypsinized and resolved by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, and the resulting mass spectra were analyzed using Mascot (Perkins et al., 1999). The ∼40-kDa low-abundance polypeptide was most likely a copurifying contaminant because it corresponded to ornithine transcarbamoylase, an enzyme whose localization in cells is restricted to mitochondria. In contrast, the major 17- to 20-kDa polypeptide corresponded to Nm23H2, a ubiquitous, cytosolic and membrane-associated isoform of NDK. The masses of nine tryptic peptides, covering 67% of the protein sequence, corresponded, with a Mowse probability score of 144 (where >54 is considered significant), to those predicted for Nm23H2. No other protein, including Nm23H1, the other major cytosolic and membrane-associated isoform of NDK, which is 88% identical to Nm23H2 at the amino acid level (Lacombe et al., 2000), was identified from the 17- to 20-kDa region of the gel.

Figure 5.

Purification of the restorative activity from cytosol. The monoS peak (see Materials and Methods; Figure 4 and Table 1) was further fractionated on an S200 gel filtration column (A), and the resulting fractions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and silver stained (B). The major copurifying polypeptide at 17 to 20 kDa is indicated by the arrowhead, and contaminating keratins at ∼55–65 kDa, as well as a minor copurifying polypeptide at ∼40 kDa, are indicated by asterisks. The positions at which the gel filtration markers migrated on the column are indicated (A). (C) Digitonin-permeabilized and salt-washed NRK cells incubated with purified COPII proteins (as in Figure 1), 500 μM GTPγS, and an ATP-regenerating system (ATP r.s.) in the absence (control) or presence (+ 2 U/ml the S200 peak) of fraction 14. After 10 min at 32°C, cells were fixed and stained using antibodies against Sec24p.

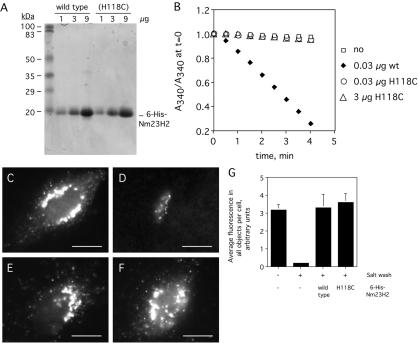

For corroboration that Nm23H2 was in fact responsible for the restorative activity in the S200 peak fractions, an N-terminally 6-His–tagged recombinant version of human Nm23H2 (6-His-Nm23H2) was expressed, purified (Figure 6A), and tested for its ability to restore COPII assembly to salt-washed cells. Indeed, 6-His-Nm23H2 fully restored COPII assembly to digitonin-permeabilized and salt-washed cells (compare Figure 6E to salt-washed cell in D, quantified in G), although the specific activity of the recombinant protein was markedly lower than that of the mammalian protein. The lower specific activity of the recombinant protein may be attributable to the presence of the 6-His tag at the N terminus of the recombinant protein or to a mammalian posttranslational modification of Nm23H2 that is absent on the bacterially produced recombinant protein. Nonetheless, our results support our conclusion that Nm23H2 is sufficient to restore assembly of purified COPII onto salt-washed cells under the conditions of our assay.

Figure 6.

Recombinant wild-type and catalytically inactive 6-His-Nm23H2 both facilitate COPII assembly in vitro. (A) One, 3, and 9 μg of purified wild-type 6-His-Nm23H2 as well as the catalytically inactive version Nm23H2 (H118C) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. (B) A standard coupled assay that measures the nucleoside diphosphokinase-dependent oxidation of NADH (see Materials and Methods) was performed on wild-type and (H11C) versions of 6-His-Nm23H2. The relative decrease in NADH absorbance over time is plotted for each. (C–G) Both wild-type and (H118C) versions of Nm23H2 facilitate COPII assembly. Digitonin-permeabilized NRK cells washed with low (C) or high (D–F) salt were incubated with purified COPII proteins (as in Figure 1), 500 μM GTPγS, and an ATP-regenerating system (ATP r.s.) in the absence (C and D) or presence of 0.05 mg/ml wild-type 6-His-Nm23H2 (E) or 0.05 mg/ml 6-His-Nm23H2 (H118C). After 10 min at 32°C, cells were fixed and stained using antibodies against Sec24p. Bar, 5 μm. Quantification of the average total Sec24 object fluorescence per cell (>25 cells), mean ± SEM, under each of the indicated conditions is shown (G).

Nm23H2 Facilitates COPII Assembly Independent of Its Nucleotide-synthesizing Activity

The Nm23H1 and Nm23H2 isoforms of NDK are ubiquitous, cytosolic, as well as reportedly membrane- and cytoskeleton-associated hexameric proteins whose best studied function is to catalyze the transfer of the γ phosphate of ATP to nucleoside diphosphates (Lascu and Gonin, 2000), thereby generating nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs). The NDK enzymes have historically been associated with the maintenance of cellular NTP pools. Thus, a trivial explanation for our identification of Nm23H2 was that NDK was required indirectly, to provide a source of NTP that was otherwise limiting in the assay. A definitive test of a role for its catalytic activity could be achieved by assaying the ability of a catalytically inactive version of Nm23H2 to facilitate COPII assembly. Previous studies have demonstrated that alteration of a critical histidine residue at amino acid position 118 to cysteine results in a version of Nm23H2 that can oligomerize, bind nucleotides and that exhibits identical thermal stability to the unaltered version, but that is catalytically inert (Dumas et al., 1992). Thus, 6-His-Nm23H2 (H118C) was expressed, purified (Figure 6A), and tested for its ability to catalyze phosphate transfer as well as its ability to promote COPII assembly. As expected, 6-His-Nm23H2 (H118C) was devoid of catalytic activity, possessing <1% of the nucleoside diphosphokinase activity of the wild-type protein (Figure 6B). Nevertheless, it restored COPII assembly to digitonin-permeabilized and salt-washed cells at the same concentrations and to the same extent as the wild-type protein (compare Figure 6F to E, quantified in G). Thus, the ability of Nm23H2 to facilitate COPII assembly in vitro does not seem to require its nucleoside diphosphokinase activity.

Nm23H2 Is Localized to an ER-like Network

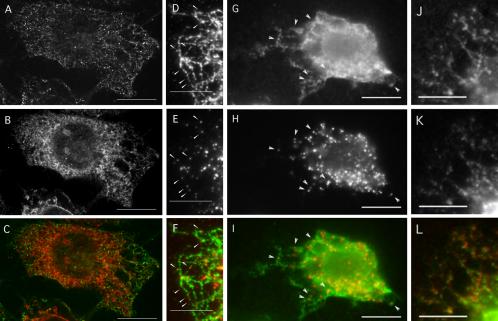

Based on the above-mentioned results, Nm23H2 might be expected to localize, at least partly, to sites of COPII assembly. Although Nm23H2 has been reported to localize to the ER and cytoskeletal fractions in specific cell types by a variety of techniques (Roymans et al., 2000; Barraud et al., 2002), immunofluorescence staining of either NRK or HeLa cells by using an antibody against Nm23H2 yielded only a diffuse cytoplasmic pattern (our unpublished data). Possibly, the cytoplasmic pool obscured any subcellularly localized protein in these cells. We therefore examined the localization of Nm23H2 with respect to COPII proteins under conditions that would remove the cytoplasmic pool of Nm23H2. For this purpose, NRK cells were digitonin permeabilized just before fixation, stained with an antibody against Nm23H2, and viewed by confocal microscopy (Figure 7A). Interestingly, Nm23H2 exhibited a filamentous/tubular pattern reminiscent of the ER. To test for coincidence with the ER, the permeabilized cells were costained with an antibody against the ER marker calnexin (Figure 7B). The ER network, as indicated by calnexin staining, did not consist of the continuous tubules observed in intact cells, possibly because the detection of calnexin was suboptimal and/or the morphology of the ER reticulum was compromised by the fixation conditions. Nonetheless, it was clear that the overall Nm23H2 network at least partially aligned with the ER network.

Figure 7.

Both endogenous and recombinant Nm23H2 are localized to an ER-like network along which a subset of COPII assembly sites generated in vitro align. (A–C) Nm23H2 localizes to a tubular/filamentous network that may in part be associated with the ER. NRK cells were digitonin permeabilized, fixed immediately in paraformaldehyde, doubly stained with an Nm23H2 mAb (A, green in merged image C) and a polyclonal antibody against calnexin (B, red in merged image C), and viewed by confocal microscopy. A single optical section from each individual, as well as the merged, channels is shown. Bar, 10 μm. (D–F) A subset of in vitro COPII assembly sites align along Nm23H2 tubules/filaments. Digitonin-permeabilized NRK cells were incubated with HeLa cytosol (4 mg/ml) in the presence of 500 μM GTPγS and an ATP-regenerating system (ATP r.s.) After 10 min at 32°C, cells were fixed and doubly stained using a mAb against Nm23H2 (D, green in merged image F) and a polyclonal antibody against Sec13p (E, red in merged image F). Arrowheads indicate a subset of COPII structures that overlap with or are adjacent to an Nm23H2 tubule/filament in the periphery of the cell. Bar, 5 μm. (G–L) 6-His-Nm23H2 localizes to an ER-like network. Digitonin-permeabilized NRK cells were incubated with rat liver cytosol (3 mg/ml), 0.025 mg/ml 6-His-Nm23H2, 500 μM GTPγS, and an ATP r.s. After 10 min at 32°C, cells were fixed and doubly stained either for the 6-His epitope (G) and Sec13p (H) or the 6-His epitope (J) and calnexin (K). The merged image for 6-His (G), green, and Sec13p (H), red, is shown in I. The merged image for 6-His (J), green, and calnexin (K), red, is shown in L. Bar, 5 μm.

Under the conditions of the previous experiment, COPII staining is not maintained (Lee and Linstedt, 2000), presumably due to GTP hydrolysis on Sar1p and disassembly of preexisting ER export complexes during permeabilization. To investigate the potential relationship between the Nm23H2 tubular/filamentous network and COPII assembly sites, digitonin-permeabilized NRK cells were further incubated with HeLa cytosol in the presence of GTPγS and an ATP-regenerating system, as described previously, to generate stable ER export complexes (Plutner et al., 1992; Bannykh et al., 1996; Lee and Linstedt, 2000). On fixation, the semiintact cells were doubly stained using antibodies against Nm23H2 and Sec13p. Again, Nm23H2 exhibited a reticular, tubular/filamentous pattern (Figure 7D). And as expected, COPII assembly was robust (Figure 7E). Under these conditions, some, though not all, of the COPII assembly sites, as indicated by the arrowheads, were located adjacent to or on top of an Nm23H2 filament/tubule (merged image in Figure 7F).

The above-mentioned results were consistent with the existence of a mechanism of targeting Nm23H2 to the ER, where it would be in position to facilitate COPII assembly. To provide further support for this hypothesis and to rule out the possibility that the apparent ER localization might be due to nonspecific cross-reactivity of the Nm23H2 antibody with an unrelated ER protein(s), the localization of the recombinant 6-His-Nm23H2 was examined, under similar conditions as in the above-mentioned experiment, using an antibody specific for the 6-His epitope. For this, digitonin-permeabilized NRK cells were incubated with rat liver cytosol plus nucleotides, in the presence of 6-His-Nm23H2. On fixation, the cells were doubly stained with an antibody specific for the 6-His epitope (Figure 7G) and an antibody against Sec13p (Figure 7H). As seen above with the Nm23H2 antibody, the 6-His epitope antibody decorated an ER-like reticular network (Figure 7G) along which COPII assembly sites were positioned (Figure 7H, merged image in I). The ER-like pattern could be attributed to the presence of the 6-His-Nm23H2 protein because only background nuclear staining was observed in its absence (our unpublished data). That the reticular pattern exhibited by 6-His-Nm23H2 was most likely the ER was confirmed by preparing cells as in the above-mentioned experiment (Figure 7, G–I) but costaining instead with the 6-His antibody (Figure 7J) and the calnexin antibody (Figure 7K, merged image in L). In sum, these results suggest that a pool of Nm23H2 is localized to the ER, in a position that would allow it to participate in COPII assembly and ER export.

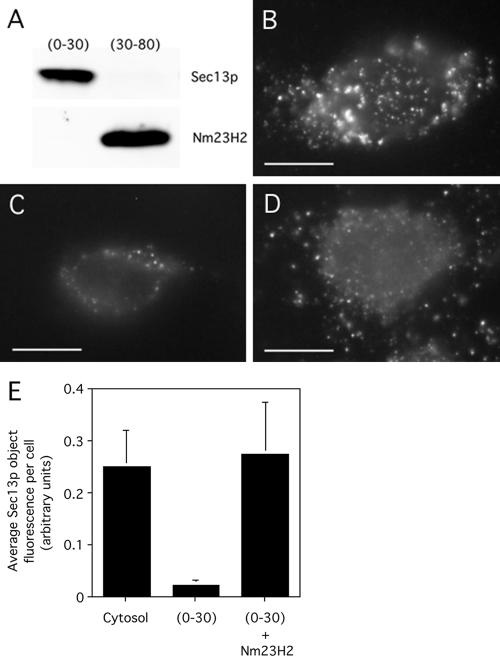

Nm23H2 Facilitates the Assembly of Mammalian Sec23/24p and Sec13/31p In Vitro

The use of yeast rather than mammalian COPII proteins in the COPII assembly assay used to identify Nm23H2 raised the concern that the role of Nm23H2 might be specific to the yeast proteins. The generality of a function for Nm23H2 in in vitro COPII assembly could be tested either by immunodepleting Nm23H2 from mammalian cytosol or by using purified mammalian COPII proteins in the assay. Unfortunately, the Nm23H2 antibody was ineffective in immunodepleting Nm23H2 from mammalian cytosol (our unpublished data); furthermore, we did not have the purified mammalian proteins in hand. Therefore, we used an alternative fractionation method to separate Nm23H2 from the bulk of COPII in mammalian cytosol. We took advantage of the fact that both Sec23/24p and Sec13/31p precipitate out of mammalian cytosol at 30% ammonium sulfate (AS) (Aridor et al., 1998), whereas Nm23H2 requires 50–80% AS (this study). Thus, to prepare a fraction of mammalian cytosol that contained COPII but not Nm23H2, we precipitated rat liver cytosol with 30% ammonium sulfate. As shown in Figure 8A (lane 1), the bulk of Sec13/31p, and presumably Sec23/24p (Aridor et al., 1998), was indeed in the 0–30% fraction, whereas the majority of Nm23H2 was present in the 30–80% fraction (Figure 8A, lane 2). Because the fractionation behavior of mammalian Sar1p has not previously been reported, we spiked the 0–30% fraction with yeast Sar1p to ensure that Sar1p was not limiting in this fraction. Sar1p is the most highly conserved COPII component between yeast and mammals: 67% identical compared with 21, 20, 48, and 53% for Sec31p, Sec24p, Sec23p, and Sec13p, respectively (Shen, 1993; Shaywitz, 1995; Paccaud, 1996; Shugrue, 1999; Tang, 1999). Significantly, incubation of digitonin-permeabilized and salt-washed cells with the 0–30% fraction lacking Nm23H2 yielded reduced COPII assembly (Figure 8C) compared with cells incubated with whole cytosol (Figure 8B). Importantly, under these conditions, addition of 6-His-Nm23H2 to the 0–30% fraction restored the assembly of mammalian COPII proteins onto salt-washed cells (Figure 8D, quantified in E). Thus, Nm23H2 promotes the assembly of both the Sec23/24p and Sec13/31p constituents of the mammalian COPII machinery.

Figure 8.

Nm23H2 facilitates the assembly of mammalian cytosolic COPII in vitro. Ammonium sulfate precipitation was used to fractionate Nm23H2 from COPII proteins in rat liver cytosol (see Materials and Methods). (A) The 0–30% fraction and the 30–80% fraction were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed by immunoblot by using antibodies against Sec13p and Nm23H2. (B–D) Digitonin-permeabilized and salt-washed cells were incubated with unfractionated cytosol (3 mg/ml) (B), the 0–30% fraction (0.3 mg/ml) in the presence of 1 μg/ml yeast Sar1p (C), or the 0–30% fraction (0.3 mg/ml) in the presence of 1 μg/ml yeast Sar1p and 0.1 mg/ml 6-His-Nm23H2 (D). After incubation for 10 min at 32°C, cells were fixed and stained using antibodies against Sec13p. Bar, 5 μm. Quantification of the total fluorescence in Sec13p objects per cell (>25 cells), mean ± SEM, under each of the indicated conditions is shown (E).

Nm23H2 Stimulates COPII Assembly and ER Export In Vivo

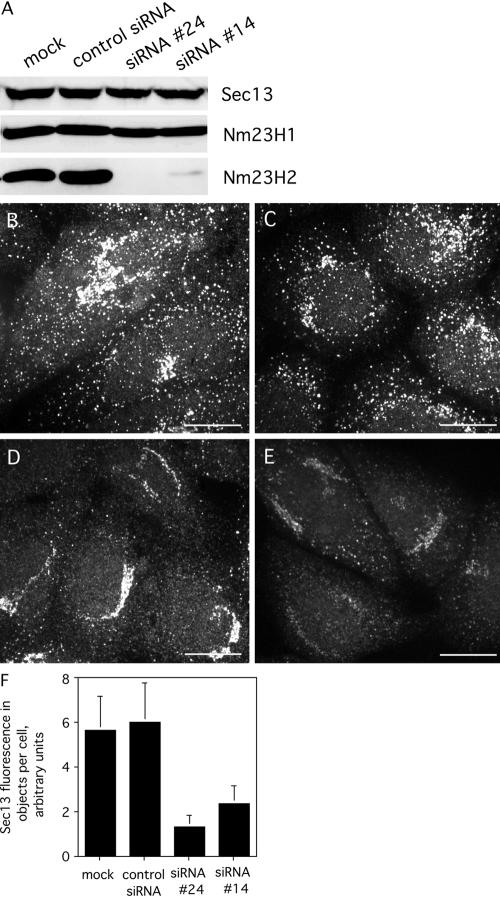

To further investigate the potential role of Nm23H2 in mammalian COPII assembly, as well as to determine whether the ability of Nm23H2 to facilitate COPII assembly in vitro reflected a physiological role for the NDK isoform in COPII assembly in vivo, we performed siRNA-mediated knockdown of Nm23H2 in HeLa cells (Elbashir et al., 2001). A sequential, double transfection of HeLa cells (Motley et al., 2003) with either of two independent siRNAs directed against Nm23H2 proved highly effective in knocking down the expression level of the Nm23H2 protein (Figure 9A). The resulting level of Nm23H2, as detected by an isoform-specific antibody, was either at about the detection limit of 4% in the case of siRNA #14 or below the detection limit in the case of siRNA #24. In contrast, cells sequentially transfected with no siRNA or a control siRNA did not show a discernable reduction of Nm23H2. Importantly, the knockdown was isoform specific, because the level of Nm23H1, the NDK isoform most similar to Nm23H2 (Lacombe et al., 2000), was unaffected in the same cells. Similarly, the protein levels of the COPII subunit Sec13 were unaffected by the siRNA treatment (Figure 9A).

Figure 9.

Depletion of Nm23H2 protein reduces COPII assembly in vivo. (A) Equal protein loadings of homogenates from HeLa cells mock-transfected, transfected with a control siRNA, Nm23H2 siRNA #24, or Nm23H2 siRNA #14, as described under Materials and Methods, were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting by using antibodies against the indicated proteins. (B–E) Cells mock transfected (B), tranfected with a control siRNA (C), siRNA#24 (D), or siRNA #14 (E) were fixed and stained using affinity-purified antibodies against Sec13p. Projected images from confocal acquisitions are shown. Bar, 10 μm. (F) Images from B–E were captured and quantified as described (Materials and Methods). The fluorescence in all discernable objects per cell (50 cells) is shown, mean + SD.

To analyze the consequence of Nm23H2 knockdown on COPII assembly, the steady-state levels of COPII at ER exit sites, as marked by Sec13 staining, were examined by confocal microscopy. Cells either mock transfected (Figure 9B) or transfected with a control siRNA (Figure 9C) exhibited a typically robust COPII pattern that was similar to that seen in untreated cells. In contrast, cells with undetectable Nm23H2 (SiRNA #24) (Figure 9D) or low but detectable Nm23H2 (siRNA #14) (Figure 9E) exhibited a significantly diminished steady-state level of Sec13 in both peripheral and juxtanuclear structures, although the reduction in peripheral structures was more pronounced. Quantification of the average total fluorescence in all objects per cell (n = 50), including both peripheral and juxtanuclear structures, revealed an ∼78% (siRNA #24) or 60% (siRNA #14) reduction in object fluorescence in cells lacking Nm23H2 (Figure 9F). These results indicated that Nm23H2 may not be essential for, but nonetheless facilitates, COPII assembly in vivo.

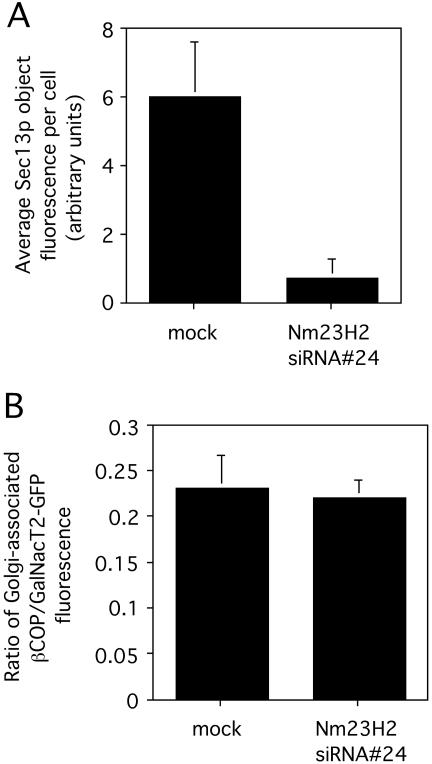

To exclude the possibility that the observed reduction in COPII assembly induced by Nm23H2 silencing might be due to a nonspecific effect of lowering cellular GTP pools, we asked whether the association of the COPI coat with the Golgi, also a GTP-dependent process (Donaldson et al., 1992), was perturbed in Nm23H2 siRNA-treated cells. GalNacT2-GFP, stably expressed in the HeLa cell line (Storrie et al., 1998) used for these siRNA treatments, was used as a marker for the Golgi. Cells, mock-transfected or transfected with Nm23H2 siRNA #24, were fixed and stained with an antibody against Sec13p or an antibody against βCOP, and viewed by confocal microscopy. The βCOP fluorescence associated with the Golgi (n = 25), as marked by GalNacT2-GFP, was measured and normalized to the Golgi-associated GalNacT2-GFP fluorescence. Quantification of the results indicated that although Nm23H2 silencing negatively affected COPII assembly (Figure 10A), it had no discernable effect on the level of COPI association with the Golgi (Figure 10B). Thus, the COPII defects induced by Nm23H2 silencing in vivo were not a general consequence of GTP depletion, but they seemed specific to assembly of the COPII coat.

Figure 10.

Depletion of Nm23H2 protein does not inhibit the association of COPI with the Golgi. HeLa cells stably expressing GalNacT2-GFP were mock-transfected or transfected with Nm23H2 siRNA #24. Cells were fixed and stained either using an antibody against Sec13p (A) or an antibody against βCOP (B) and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Projected images were captured and quantified as described (Materials and Methods). (A) The Sec13p fluorescence in all discernable objects per cell is shown (>25 cells), mean ± SD. (B) The ratio of βCOP fluorescence (rhodamine) in the Golgi region to GalNacT2-GFP fluorescence in the Golgi region of each cell (>25 cells), mean ± SD is shown.

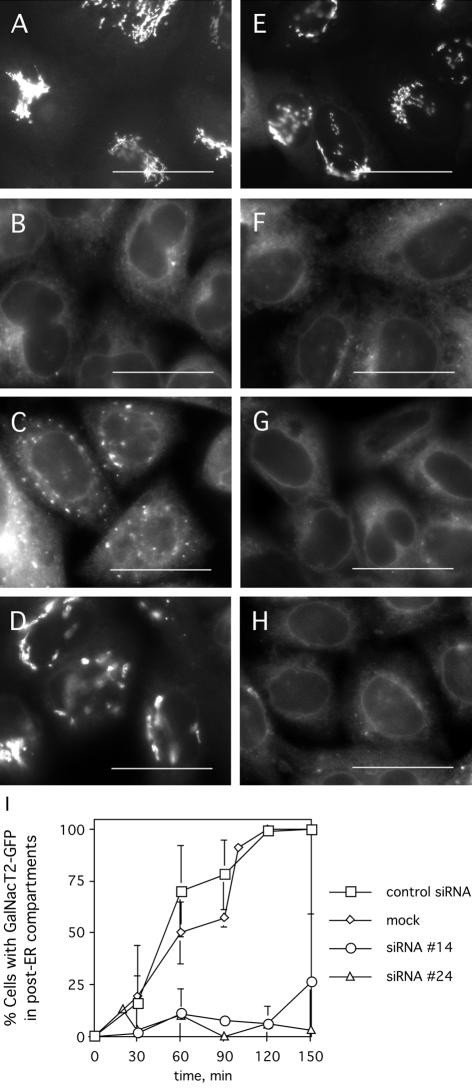

To determine whether the above-mentioned reduction in COPII assembly due to Nm23H2 silencing might be associated with a transport defect, the kinetics of ER export was next examined. ER export kinetics were assessed by measuring the rate of exit of GalNacT2-GFP from the ER upon BFA treatment and washout (Lippincott-Schwartz et al., 1989) (Figure 11). As expected, a 20-min treatment with BFA led to the complete redistribution of GalNacT2-GFP from the Golgi (Figure 11A) to the ER in mock-transfected cells (Figure 11B). Subsequent ER export, as evidenced by the emergence of GalNacT2-GFP from the ER into post-ER compartments, was observed in >25% of the mock-transfected cells by 40 min of washing out the BFA (Figure 11C). By 100 min, >90% of the cells exhibited a nearly normal Golgi pattern of GalNacT2-GFP (Figure 11D).

Figure 11.

Depletion of Nm23H2 protein leads to reduced kinetics of GalNacT2-GFP export from the ER. HeLa cells stably expressing GalNacT2-GFP and mock transfected, transfected with a control siRNA, siRNA #24, or siRNA #14, were incubated with 5 μg/ml BFA for 20 min. Thereafter, cells were washed into normal medium and fixed at various times to assess the extent of reemergence of GalNacT2-GFP into post-ER compartments. A representative time course, before the BFA treatment (A and E), and at 0 min (B and F), 40 min (C and G), or 100 min (D and H) after the BFA washout, for mock-transfected cells (A–D) and cells transfected with siRNA #24 (E–H) is shown. Bar, 20 μm. (I) A quantification of the percentage of cells with GalNacT2-GFP in post-ER compartments at each time point for each transfection condition is shown. More than 150 cells were analyzed at each time point. The results represent mean ± SD.

The kinetics of ER export contrasted sharply in the absence of Nm23H2. Although Nm23H2 silencing did not noticeably affect either the steady-state localization of GalNacT2-GFP to the Golgi (Figure 11E) nor the BFA-induced redistribution of GalNacT2-GFP into the ER (Figure 11F), GalNacT2-GFP remained ER-localized in a higher percentage of cells transfected with either Nm23H2 siRNA at every time point. GalNacT2-GFP had emerged from the ER in <10% of the cells at 40 min (Figure 11G) and <25% of the cells showed evidence of GalNacT2-GFP in post-ER compartments at 100 min (Figure 11H). Quantification of the results (Figure 11I) indicated a significant delay in ER export induced by Nm23H2 silencing. However, GalNacT2-GFP eventually emerged out of the ER by 200–300 min, even in cells lacking detectable Nm23H2 (our unpublished data).

That ER export was significantly delayed but not completely blocked was consistent with the partial, rather than complete, loss of COPII at ER exit sites observed in cells lacking Nm23H2 (Figure 9F). The kinetic delay also explains the observation that GalNacT2-GFP retains its steady-state Golgi localization in cells lacking detectable Nm23H2; a complete block in ER export would be expected to result in the slow redistribution of Golgi proteins to the ER (Ward, 2001). Consistent with this explanation, the partial inhibition of ER export induced by Nm23H2 silencing did perturb the steady-state localization of ERGIC-53, a protein that cycles more rapidly (t1/2 of ∼30 min) through the ER to achieve its steady-state localization in the endoplasmic reticulum intermediate compartment (ERGIC) (Cole et al., 1998). ERGIC-53 was partially redistributed to the ER (∼70% loss of ERGIC-53 object fluorescence) in Nm23H2-silenced cells (our unpublished data). Together, our results support an in vivo facilitating role for Nm23H2 in COPII assembly and ER export.

DISCUSSION

Not only was Nm23H2 identified as a facilitator of COPII assembly in an in vitro assay but also its role in the process has been corroborated in vivo. The idea that evolution has drawn on preexisting, abundant metabolic enzymes as a source of novel functions is a common recurring theme (Gerhart and Kirschner, 1997). A particularly illustrative example is glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), which seems to have evolved into a multifunctional protein through incremental changes in amino acid sequence that were neutral with respect to its housekeeping function but that endowed the altered versions with new, unrelated functions. In this regard, the NDK family may have provided an even richer source of novel functions because although GAPDH is encoded by a single gene (Piechaczyk et al., 1984), the NDK family consists of eight distinct genes (Nm23H1–H8), each differing in tissue distribution and subcellular localization. Nearly all NDK isoforms contain the set of highly conserved residues critical for nucleotide binding and hydrolysis, but these common elements are interspersed with variable regions in the different isoforms, leading to the speculation that the variable regions may be responsible for functions unrelated to nucleotide synthesis (Lacombe et al., 2000). Indeed, the reduction in COPII assembly and ER export kinetics caused by Nm23H2 silencing occurred even in the presence of normal levels of Nm23H1, the NDK isoform most closely related to Nm23H2. The apparent inability of Nm23H1 to take the place of Nm23H2 under these conditions raises the possibility that the ability of Nm23H2 to aid in COPII assembly might be isoform specific. A definitive test of isoform specificity awaits the test of Nm23H1 and other NDK isoforms in the in vitro COPII assembly assay. If, however, Nm23H1 turns out to be inactive in the COPII assembly assay, then the 18 amino acid residues that differ between Nm23H2 and Nm23H1 (Lacombe et al., 2000) would be predicted to mediate interactions that confer the specific ability of Nm23H2 to facilitate COPII assembly.

The mechanism by which Nm23H2 promotes COPII assembly in mammalian cells remains to be determined. Our finding that the catalytically inactive version of Nm23H2 is fully functional in the in vitro COPII assembly assay rules out the trivial possibility that it promotes assembly indirectly by affecting NTP pools. Rather, Nm23H2 is more likely to play a structural role in the process. Under the conditions of the in vitro COPII assembly assay, Nm23H2 was found to decorate an ER-like filamentous/tubular network. An intriguing possibility is that Nm23H2 participates in the formation of a proteinaceous scaffold along which ER exit sites are organized. However, if Nm23H2 localization to sites of COPII assembly is important for its function in ER export, it must be a transient association because not all COPII assembly sites generated in vitro in the presence of GTPγS colocalized with an Nm23H2-containing structure.

It is noteworthy that the residual COPII assembly that occurs both in vivo and in vitro in the apparent absence of Nm23H2 is predominantly juxtanuclear. There are several possible explanations for this observation. One is that the juxtanuclear exit sites differ from the peripheral sites in their requirements for COPII assembly. According to this explanation, COPII assembly at all exit sites would require Sar1p, Sec23/24p, and GTPγS, but only the peripheral sites would further depend on Nm23H2. An alternative explanation is that Nm23H2 facilitates COPII assembly at both juxtanuclear and peripheral ER exit sites but that the residual Golgi-adjacent structures are more readily detectable in the morphological assay. This could reflect the higher density of Golgi-adjacent ER buds compared with those at peripheral sites (Bannykh et al., 1996).

That residual COPII assembly and ER export occurred in cells lacking detectable Nm23H2 could be attributed either to an incomplete knockdown of Nm23H2 expression by the siRNA treatment or to a facilitating, but nonessential, role for Nm23H2 in COPII assembly and ER export. A definitive resolution of this issue awaits a more complete mechanistic understanding of Nm23H2 function; that is, whether it functions as part of the core reaction mechanism or whether it plays a regulatory role. If Nm23H2 plays a nonessential role in COPII vesicle formation in mammalian cells, it may reflect added layers of control over the highly conserved process of COPII assembly. Perhaps consistent with this possibility, deletion of yeast NDK, which is encoded by a single gene, does not result in any obvious growth defects (Fukuchi et al., 1993). Besides implying that even yeast cells have other mechanisms for maintaining NTP pools, the apparent lack of a required role for NDK in COPII assembly in yeast raises the possibility that a role for NDK in COPII-coated vesicle formation may have evolved more recently to allow higher eukaryotic cells to regulate ER export both spatially and temporally in response to variety of physiological cues. Indeed, COPII assembly is inhibited at mitosis in mammalian (Farmaki et al., 1999; Hammond and Glick, 2000) but not yeast cells (Salama et al., 1997). And, in contrast to the ATP requirement and putative protein kinase requirement demonstrated for COPII assembly from mammalian ER membranes (Aridor et al., 1998; Aridor and Balch, 2000; Lee and Linstedt, 2000), COPII vesicle formation from yeast microsomes does not require ATP (Barlowe et al., 1994).

Finally, our results reveal an unexpected parallel between ER export and endocytosis. Significantly, Nm23H1, the NDK isoform most similar to Nm23H2 (88% identical), has been implicated in clathrin- and dynamin-mediated endocytosis. Mutant hypomorphic alleles of Nm23H1 were identified as enhancers of the Drosophila shibirets mutant in dynamin (Krishnan et al., 2001) and overexpression of a catalytically inactive version of Nm23H1 blocked Arf6-GTP–stimulated internalization of E-cadherin in mammalian epithelial cells (Palacios et al., 2002). Moreover, Nm23H1 physically interacts with Arf6-GTP (Palacios et al., 2002) and dynamin (Baillat et al., 2002), as well as tiam1, a GTP exchange factor for Rac1 (Otsuki et al., 2001). These data have led to the suggestion that Nm23H1 plays a central role in endocytosis, linking pathways regulating both vesicle fission and actin dynamics to the activation of Arf6 (Di Fiore and De Camilli, 2001). It is worth noting, however, that the putative function of Nm23H2 during ER export may not precisely parallel that of Nm23H1 in endocytosis because, in contrast to Nm23H1, Nm23H2 apparently does not require catalytic activity to perform its vesicle formation function.

Future work on Nm23H2, including the identification of the precise step in the COPII assembly pathway that relies on Nm23H2, as well as the identification of its binding partners in the process, promises to reveal novel mechanistic insight into how COPII-mediated vesicle formation from the ER is orchestrated in mammalian cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by the support of A. Linstedt (Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA) and the generous contribution of many COPII reagents by R. Schekman and B. Lesch (University of California, Berkeley). Thanks to S. Dowd and J. Minden (Carnegie Mellon University) for help with mass spectrometry; G. Apodaca (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) for providing rabbit liver; S. Puri and M. Puthenveedu for advice on siRNA methodologies; and S. Puri, M. Puthenveedu; and A. Linstedt for improving the manuscript. This work was supported by a Berkman Foundation fellowship to T.H.L., a Samuel and Emma Winters Foundation fellowship to T.H.L.; an anonymous contribution to T.H.L.; and a grant from the National Institutes of Health to A.D.L.

Article published online ahead of print in MBC in Press on December 9, 2004 (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0785).

References

- Agarwal, R. P., Robison, B., and Parks, R. E. (1978). Nucleoside diphosphokinase from human erythrocytes. Meth. Enzymol. 51, 376-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonny, B., Madden, D., Hamamoto, S., Orci, L., and Schekman, R. (2001). Dynamics of the COPII coat with GTP and stable analogues. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 531-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonny, B., and Schekman, R. (2001). ER export: public transportation by the COPII coach. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 438-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aridor, M., and Balch, W. E. (2000). Kinase signaling initiates coat complex II (COPII) recruitment and export from the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35673-35676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aridor, M., Bannykh, S. I., Rowe, T., and Balch, W. E. (1995). Sequential coupling between COPII and COPI vesicle coats in endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport. J. Cell Biol. 131, 875-893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aridor, M., and Traub, L. M. (2002). Cargo selection in vesicular transport: the making and breaking of a coat. Traffic 3, 537-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aridor, M., Weissman, J., Bannykh, S., Nuoffer, C., and Balch W. E. (1998). Cargo selection by the COPII budding machinery during export from the ER. J. Cell Biol. 141, 61-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillat, G., Gaillard, S., Castets, F., and Monneron, A. (2002). Interactions of phocein with nucleoside-diphosphate kinase, Eps15, and Dynamin I. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18961-18966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannykh, S. I., and Balch, W. E. (1997). Membrane dynamics at the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi interface. J. Cell Biol. 138, 1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannykh, S. I., Rowe, T, and Balch, W. E. (1996). The organization of endoplasmic reticulum export complexes. J. Cell Biol. 135, 19-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlowe, C., d'Enfert, C., and Schekman, R. (1993). Purification and characterization of SAR1p, a small GTP-binding protein required for transport vesicle formation from the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 873-879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlowe, C., Orci, L., Yeung, T., Hosobuchi, M., Hamamoto, S., Salama, N., Rexach, M. F., Ravazzola, J., Amherdt, M., and Shekman, R. (1994). COPII: a membrane coat formed by Sec proteins that drive vesicle formation from the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 77, 895-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlowe, C., and Schekman, R. (1993). SEC12 encodes a guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor essential for transport vesicle budding from the ER. Nature 365, 347-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraud, P., Amrein, L., Dobremez, E., Dabernat, S., Masse, K., Larou, M., Daniel, J. Y., and Landry, M. (2002). Differential expression of nm23 genes in adult mouse dorsal root ganglia. J. Comp. Neurol. 444, 306-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino, J. S., and Glick, B. S. (2004). The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell 116, 153-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger, A. T., and DeLaBarre, B. (2003). NSF and p97/VCP: similar at first, different at last. FEBS Lett. 555, 126-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreno, S., Engqvist-Goldstein, A. E., Zhang, C. X., McDonald, K. L., and Drubin, D. G. (2004). Actin dynamics coupled to clathrin-coated vesicle formation at the trans-Golgi network. J. Cell Biol. 165, 781-788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner, S. D., and Schmid, S. L. (2003). Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature 422, 37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello, F., Schulze, R. A., Heemeyer, F., Meyer, H. E., Lutz, S., Jakobs, K. H., Niroomand, F., and Wieland, T. (2003). Activation of heterotrimeric G proteins by a high energy phosphate transfer via nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK) B and Gbeta subunits. Complex formation of NDPKB with Gbeta gamma dimers and phosphorylation of His-266 IN Gbeta. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7220-7226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, S., Rosser, M. F., Cyr, D. M., and Hanson, P. I. (2004). Distinct roles for the AAAATPases NSF and p97 in the secretory pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 637-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fiore, P. P., and De Camilli, P. (2001). Endocytosis and signaling. An inseparable partnership. Cell 106, 1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, J. G., Cassel, D., Kahn, R. A., and Klausner, R. D. (1992). ADP-ribosylation factor, a small GTP-binding protein, is required for binding of the coatomer protein beta-COP to Golgi membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 6408-6412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir, S. M., Harborth, J., Lendeckel, W., Yalcin, A., Weber, K., and Tuschl, T. (2001). Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature 411, 494-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engqvist-Goldstein, A. E., and Drubin, D. G. (2003). Actin assembly and endocytosis: from yeast to mammals. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 287-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espenshade, P., Gimeno, R. E., Holzmacher, E., Teung, P., and Kaiser, C. A. (1995). Yeast SEC16 gene encodes a multidomain vesicle coat protein that interacts with Sec23p. J. Cell Biol. 131, 311-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espenshade, P. J., Li, W. P., and Yabe, D. (2002). Sterols block binding of COPII proteins to SCAP, thereby controlling SCAP sorting in ER. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 11694-11699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki, T., Ponnambalam, S., Prescott, A. R., Clausen, H., Tang, B. L., Hong, W., and Lucocq, J. M. (1999). Forward and retrograde trafficking in mitotic animal cells. ER-Golgi transport arrest restricts protein export from the ER into COPII-coated structures. J. Cell Sci. 112, 589-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuchi, T., Nikawa, J., Kimura, N., and Watanabe, K. (1993). Isolation, overexpression and disruption of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae YNK gene encoding nucleoside diphosphate kinase. Gene 129, 141-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart, J., and Kirschner, M. (1997). Cells, Embryos, and Evolution. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science.

- Hammond, A. T., and Glick, B. S. (2000). Dynamics of transitional endoplasmic reticulum sites in vertebrate cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 3013-3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidtman, M., Chen, C. Z., Collins, R. N., and Barlowe, C. (2003). A. role for Yip1p in COPII vesicle biogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 163, 57-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke, L., and Schekman, R. (1989). Yeast Sec23p acts in the cytoplasm to promote protein transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi complex in vivo and in vitro. EMBO J. 8, 1677-1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw, J. E. (2000). Dynamin and its role in membrane fission. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 483-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippe, H. J., Lutz, S., Cuello, F., Knorr, K., Vogt, A., Jakobs, K. H., Wieland, T., and Niroomand, F. (2003). Activation of heterotrimeric G proteins by a high energy phosphate transfer via nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK) B and Gbeta subunits. Specific activation of Gsalpha by an NDPKBGbeta-gamma complex in H10 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7227-7233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano, F., Tanaka, A. R., Yamauchi, S., Kondo, H., and Murata, M. (2004). Cdc2 kinase-dependent disassembly of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) exit sites inhibits ER-to-Golgi vesicular transport during mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 4289-4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhausen, T. (2000). Three ways to make a vesicle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1, 187-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, K. S., Rikhy, R., Rao, S., Shivalkar, M., Mosko, M., Narayanan, R., Etter, P., Estes, P. S., and Ramaswami, M. (2001). Nucleoside diphosphate kinase, a source of GTP., is required for dynamin-dependent synaptic vesicle recycling. Neuron 30, 197-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn, M. J., Herrmann, J. M., and Schekman, R. (1998). COPII-cargo interactions direct protein sorting into ER-derived transport vesicles. Nature 391, 187-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe, M. L., Milon, L., Munier, A., Mehus, J. G., and Lambeth, D. O. (2000). The human Nm23/nucleoside diphosphate kinases. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 32, 247-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lascu, I., and Gonin, P. (2000). The catalytic mechanism of nucleoside diphosphate kinases. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 32, 237-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederkremer, G. Z., Cheng, Y., Petre, B. M., Vogan, E., Springer, S., Schekman, R., Walz, T., and Kirchhausen, T. (2001). Structure of the Sec23p/24p and Sec13p/31p complexes of COPII. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 10704-10709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T. H., and Linstedt, A. D. (1999). Osmotically induced cell volume changes alter anterograde and retrograde transport, Golgi structure, and COPI dissociation. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 1445-1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T. H., and Linstedt, A. D. (2000). Potential role for protein kinases in regulation of bidirectional endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi transport revealed by protein kinase inhibitor H89. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 2577-2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippincott-Schwartz, J., Yuan, L. C., Bonifacino, J. S., and Klausner, R. D. (1989). Rapid redistribution of Golgi proteins into the ER in cells treated with brefeldin A: evidence for membrane cycling from Golgi to ER. Cell 56, 801-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka, K., Orci, L., Amherdt, M., Bednarek, S. Y., Hamamoto, S., Schekman, R., and Yeung, T. (1998). COPII-coated vesicle formation reconstituted with purified coat proteins and chemically defined liposomes. Cell 93, 263-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka, K., Orci, L., Amherdt, M., Bednarek, S. Y., Hamamoto, S., Schekman, R., and Yeung, T. (2001). Surface structure of the COPII-coated vesicle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 13705-13709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, E. A., Beilharz, T. H., Malkus, P. N., Lee, M. C., Hamamoto, S., Orci, L., and Schekman, R. (2003). Multiple cargo binding sites on the COPII subunit Sec24p ensure capture of diverse membrane proteins into transport vesicles. Cell 114, 497-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossessova, E., Bickford, L. C., and Goldberg, J. (2003). SNARE selectivity of the COPII coat. Cell 114, 483-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motley, A., Bright, N. A., Seaman, M. N., and Robinson, M. S. (2003). Clathrin-mediated endocytosis in AP-2-depleted cells. J. Cell Biol. 162, 909-918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, A., and Muramatsu, M. (1989). A novel GTP-binding protein, Sar1p, is involved in transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus. J. Cell Biol. 109, 2677-2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel, W., Brugger, B., and Wieland, F. T. (2002). Vesicular transport: the core machinery of COPI recruitment and budding. J. Cell Sci. 115, 3235-3240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuki, Y., Tanaka, M., Yoshii, S., Kawazoe, N., Nakaya, K., and Sugimura, H. (2001). Tumor metastasis suppressor nm23H1 regulates Rac1 GTPase by interaction with Tiam1.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 4385-4390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paccaud, J. P., Reith, W., Carpentier, J. L., Ravazzola, M., Amherdt, M., Schekman, R., and Orci, L. (1996). Cloning and functional characterization of mammalian homologues of the COPII component Sec23. Mol. Biol. Cell 7, 1535-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, F., J. K. Schweitzer, Boshans, R. L., and D'Souza-Schorey, C. (2002). ARF6-GTP recruits Nm23–H1 to facilitate dynamin-mediated endocytosis during adherens junctions disassembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 929-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathre, P., Shome, K., Blumental-Perry, A., Bielli, A., Haney, C. J., Alber, S., Watkins, S. C., Romero, G., and Aridor, M. (2003). Activation of phospholipase D by the small GTPase Sar1p is required to support COPII assembly and ER export. EMBO J. 22, 4059-4069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, D. N., Pappin, D. J., Creasy, D. M., and Cottrell, J. S. (1999). Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis 20, 3551-3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piechaczyk, M., Blanchard, J. M., Riaad-El Sabouty, S., Dani, C., Marty, L., and Jeanteur, P. (1984). Unusual abundance of vertebrate 3-phosphate dehydrogenase pseudogenes. Nature 312, 469-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]