Xu et al. show that Etv2 is required for hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) proliferation and expansion after bone marrow transplantation and hematopoietic injury. c-Kit functions downstream of Etv2 in mediating HSPC proliferation and expansion.

Abstract

Recent studies have established that hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are quiescent in homeostatic conditions but undergo extensive cell cycle and expansion upon bone marrow (BM) transplantation or hematopoietic injury. The molecular basis for HSC activation and expansion is not completely understood. In this study, we found that key developmentally critical genes controlling hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) generation were up-regulated in HSPCs upon hematopoietic injury. In particular, we found that the ETS transcription factor Ets variant 2 (Etv2; also known as Er71) was up-regulated by reactive oxygen species in HSPCs and was necessary in a cell-autonomous manner for HSPC expansion and regeneration after BM transplantation and hematopoietic injury. We found c-Kit to be downstream of ETV2. As such, lentiviral c-Kit expression rescued Etv2-deficient HSPC proliferation defects in vitro and in short-term BM transplantation in vivo. These findings demonstrate that Etv2 is an important regulator of hematopoietic regeneration.

Introduction

The hematopoietic system is remarkably sensitive to injury, including radiation or chemotherapy. As such, radiation can lead to lymphocyte, neutrophil, erythrocyte, and platelet loss, disruption of tissue homeostasis, and organismal death from infection and/or hemorrhage. Thus, rapid and effective regeneration of the hematopoietic system in response to injury is requisite for successful restoration of the hematopoietic tissue homeostasis and organismal survival. To this end, recent studies have demonstrated that hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) rarely proliferate in steady states. However, they expand greatly after transplantation or injury to guarantee efficient restoration of the hematopoietic system (Sun et al., 2014; Busch et al., 2015; Säwén et al., 2016). As such, mechanistic understanding of such rapid hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) expansion would be beneficial for designing strategies achieving more efficient transplantation and hematopoietic regeneration.

ETS transcription factors have emerged as critical regulators of hematopoietic and vascular development (De Val and Black, 2009; Sumanas and Choi, 2016). In particular, Etv2 (also known as Er71 and etsrp) performs a nonredundant and indispensable function in hematopoietic and vessel development during embryogenesis, as Etv2 deficiency leads to a complete block in hematopoietic and vascular formation and embryonic lethality (Lee et al., 2008; Ferdous et al., 2009). Studies in zebrafish and Xenopus laevis have also demonstrated the critical function of etv2 in blood and vessel formation (Sumanas and Lin, 2006; Sumanas et al., 2008; Neuhaus et al., 2010; Salanga et al., 2010). Importantly, Etv2 is transiently expressed in the primitive streak, yolk sac blood islands, and large vessels including the dorsal aorta during embryogenesis (Lee et al., 2008; Kataoka et al., 2011; Rasmussen et al., 2011; Wareing et al., 2012). Etv2 expression becomes undetectable once endothelial and hematopoietic cell lineages have been formed during embryogenesis. As such, hematopoietic and/or endothelial deletion of Etv2 by using Tie2-Cre, VEC-Cre, or Vav-Cre leads to normal embryogenesis (Park et al., 2016), supporting the notion that Etv2 is only transiently required for the vessel and blood cell lineage formation. Consistently, Etv2 deletion by using Flk1-Cre leads to embryonic lethality because of insufficient hemangiogenic progenitor generation (Liu et al., 2015). Mechanistically, ETV2 positively activates genes critical for hematopoietic and endothelial cell lineage specification (Liu et al., 2012, 2015).

Despite its essential function in hematopoietic and vascular cell lineage development, studies investigating its role in adult hematopoiesis have been limiting. Notably, Etv2 deletion using the Mx1-Cre system and polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (pIpC) administration led to seemingly rapid loss of HSC number and their hematopoietic reconstitution potential (Lee et al., 2011). Although this study suggested its role in maintaining hematopoiesis in steady states, Tie2-Cre (hematopoietic and endothelial)– or Vav-Cre (hematopoietic)–mediated Etv2 deletion resulted in no appreciable hematopoietic phenotypes in steady states (Park et al., 2016). As the severe phenotype observed by Lee et al. (2011) could be caused by the combined effect between Etv2 loss and pIpC treatment, which perturbs steady-state hematopoiesis (Essers et al., 2009; Sato et al., 2009), we determined whether Etv2 might have an unexpected role in non–steady-state hematopoiesis. Specifically, we characterized hematopoietic regeneration in Etv2-deficient mice by using BM transplantation and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)–mediated hematopoietic injury models. Our study demonstrated that although Etv2 was not essential for homeostatic hematopoiesis, it was reactivated upon injury and was required for HSPC proliferation to rapidly restore the hematopoietic system. We identify reactive oxygen species (ROS) as an upstream factor that activates Etv2 in injury. Without Etv2, HSPCs failed to expand, and mice succumbed to hematopoietic failure and death, revealing a critical role of this factor in hematopoietic regeneration. Importantly, we identify c-Kit as a downstream target that could rescue proliferation defects of the Etv2-deficient HSPCs in vitro and in short-term BM transplantation in vivo.

Results and discussion

Etv2 is activated upon hematopoietic injury through ROS

We previously reported that mature blood (B220+, Mac1+, Gr1+, Ter119+, CD4+, and CD8+) and HSPC (c-KIT+Sca1+Lin− [KSL]) cell populations in Tie2-Cre;Etv2f/f (herein Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO) mice were present at similar levels compared with controls (Park et al., 2016). Additional analysis for the frequency and absolute number of the lineage negative (Lin−), c-Kit+Sca1−Lin− (LK; progenitor cell) and the CD150+CD48−KSL (KSL-SLAM [signaling lymphocytic activation molecule]; HSC) cell population in Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO BM revealed that they were also comparable with those of the littermate control mice (not depicted). Similarly, the common myeloid progenitor (CD34+CD16/32−LK), granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (CD34+CD16/32+LK), and megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitor (CD34−CD16/32+LK) cell populations were also comparable in Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO and control BM (not depicted). These findings support the notion that Etv2 was dispensable for maintaining homeostatic hematopoiesis.

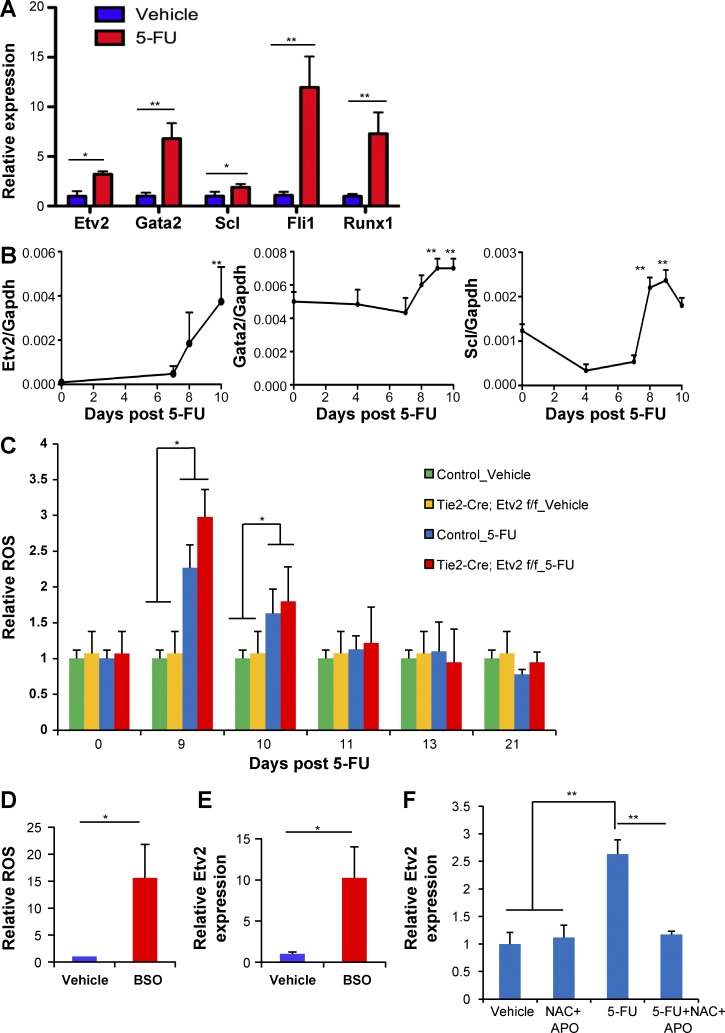

To determine whether Etv2 plays a role in nonhomeostatic conditions, we assessed whether its expression was activated in HSPCs after hematopoietic injury, assuming its activation would have a role in regeneration. In particular, we assessed BM response to 5-FU treatment, as it depletes cycling hematopoietic cells and activates quiescent HSCs to proliferate and self-renew. Upon 5-FU injury, cycling hematopoietic cells are rapidly lost (days 1–5), hematopoietic regeneration ensues (days 6–11), and then homeostasis is reestablished (after day 20). Unexpectedly, Etv2 expression was readily detected in HSPCs, not in more committed progenitor cells (Lin−c-Kit+Sca1−; not depicted), when examined 10 d after 5-FU injection (Fig. 1 A). Additional key transcription factors controlling HSPC generation in development, Gata2, Scl, Fli1, and Runx1, were also up-regulated (Fig. 1 A). Importantly, the kinetics of expression of these key genes, Etv2, Gata2, and Scl, coincided with that of the regeneration phase (Fig. 1 B). As tissue injury leads to ROS production and ROS is required for tissue regeneration (Gauron et al., 2013; Love et al., 2013), we determined whether 5-FU injury leads to ROS production and Etv2 activation in HSPCs. Remarkably, ROS levels were elevated in HSPCs during the regeneration phase after 5-FU treatment (days 9 and 10) but returned to normal levels by day 11 and remained low for the duration of the study (after day 13; Fig. 1 C). We saw slightly higher levels of ROS in Etv2-deficient HSPCs compared with controls at day 9, presumably because of proliferation defects in Etv2-deficient HSPCs leading to accumulation of the ROS generated (see the next section). Importantly, l-buthionine-S,R-sulfoximine (BSO), an inhibitor of glutathione biosynthesis, which leads to ROS production, increased intracellular ROS levels and Etv2 expression in HSPCs, suggesting that 5-FU injury leads to ROS production and Etv2 up-regulation in HSPCs (Fig. 1, D and E). Indeed, Etv2 expression remained low in HSPCs when N-acetyl cysteine (NAC; ROS scavenger) and apocynin (NADPH [nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced] oxidase inhibitor) were administered during recovery phase after 5-FU injury, demonstrating that ROS is upstream of Etv2 activation upon injury (Fig. 1 F).

Figure 1.

Etv2 is activated upon hematopoietic injury through ROS. (A) KSL cells were sorted from WT mice 10 d after vehicle (PBS) or 250 mg/kg 5-FU injection i.p. 20,000–40,000 pooled KSL cells from each sample were subjected to RNA extraction and real-time PCR. Data are shown as a relative expression of Etv2, Gata2, Scl, Fli1, and Runx1 normalized to the vehicle-treated control group. n = 9 from three independent experiments. (B) KSL cells were sorted at the indicated time points after 250 mg/kg 5-FU injection i.p. 20,000–40,000 pooled KSL cells (Etv2) or whole BM (Scl and Gata2) were subjected to RNA extraction and real-time PCR. Etv2, Gata2, and Scl expression normalized to GAPDH is shown. n = 4–6 from two independent experiments. (C) Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice or littermate control mice were injected with 250 mg/kg 5-FU i.p. or vehicle (PBS). DCFDA staining was performed on KSL cells from days 0, 9, 10, 11, 13, and 21 after 5-FU injection. Data are expressed as a relative ROS level normalized to the littermate control day-0 group. n = 6–9 from two independent experiments. (D and E) 40,000 KSL cells were cultured in a 24-well plate for 2 d with 10 µM BSO or vehicle, followed by DCFDA staining or real-time PCR analysis. Relative ROS levels and Etv2 expression in KSL cells were normalized to the vehicle control group. n = 6 from two independent experiments. (F) WT mice were injected with 250 mg/kg 5-FU i.p. or vehicle. Mice were treated with NAC and apocynin (APO) from days 4–10. 1 mg/ml NAC was added in the drinking water (changed every 3 d). 50 mg/kg apocynin was injected i.p. every day for 6 d starting from day 4. At day 10, 20,000–40,000 KSL cells were sorted for RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR. Data are expressed as a relative Etv2 expression normalized to the vehicle control group. n = 6 from two independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

Hematopoietic Etv2 but not endothelial Etv2 is critical for HSPC regeneration after 5-FU injury

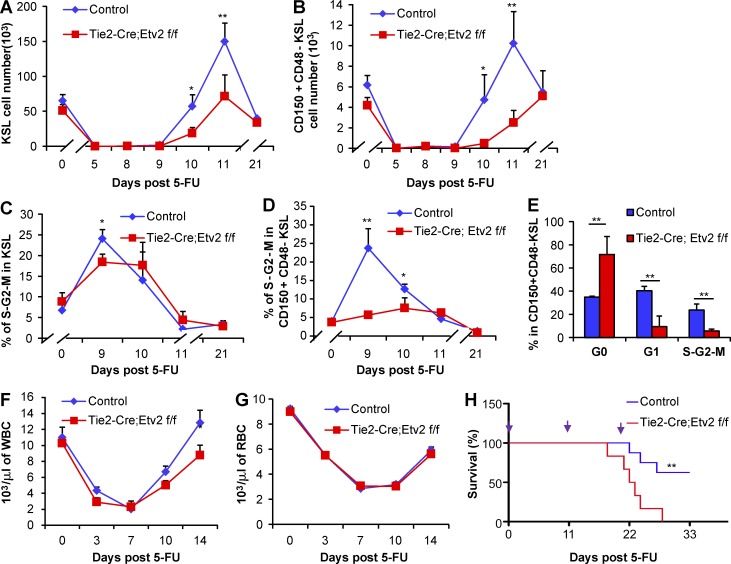

To evaluate the significance of the Etv2 activation in the regeneration capacity of HSPCs, we assessed the HSPC recovery potential in Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice after 5-FU injury (250 mg/kg). No significant difference in the BM cellularity was observed after 5-FU injection between control and CKO mice (not depicted). Whereas the KSL and CD150+CD48−KSL absolute cell number and frequency in control mice recovered by 11 d after 5-FU injury and reached homeostatic levels by day 21, Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO BM had reduced levels of HSPCs at days 10 and 11 (Fig. 2, A and B; Fig. S1). Despite the reduced HSPC recovery rate, HSPCs in Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice also reached the homeostatic levels by day 21 (Fig. 2, A and B). The reduced HSPC frequency during the recovery phase, days 10 and 11, suggested lower proliferation rate of HSPCs. Thus, we assessed whether Etv2 deletion impacted HSPC proliferation. Specifically, we performed Ki67 and DAPI staining to determine the cell cycle status of the Etv2-deficient HSPCs. The percentage of KSL cells in the S-G2-M phase was slightly less, but statistically significant, in Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice compared with control mice at day 9 after 5-FU injury (Fig. 2 C). By day 10, Etv2-deficient KSL cells had a similar percentage of cells in the S-G2-M phase compared with controls. Notably, the percentage of CD150+CD48−KSL cells in the S-G2-M phase was greatly reduced in Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice during the recovery period after 5-FU injury (Fig. 2 D). These cells were mainly in the quiescent state (Fig. 2 E), suggesting that Etv2 is required for promoting HSC proliferation and regeneration.

Figure 2.

Impaired hematopoietic regeneration in Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice after 5-FU treatment. (A–H) Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice or littermate control mice were injected with 250 mg/kg 5-FU i.p. or vehicle. (A and B) At days 0, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 21 after 5-FU injection, the absolute number (per femur and tibia) of KSL or KSL-SLAM cells was determined by flow cytometry. n = 6 from two independent experiments. (C and D) At days 0, 9, 10, 11, and 21 after 5-FU injection, the percentage of G0, G1, and S-G2-M phases in KSL or KSL-SLAM (CD150+CD48z− KSL) was determined by flow cytometry using surface markers Ki67 and DAPI staining. n = 6 from two independent experiments. (E) Cell cycle analysis of KSL-SLAM cells is shown at day 9. n = 6 from two independent experiments. (F and G) Complete blood cell count was analyzed by a Hemavet 950FS hematology system at days 0, 3, 7, 10, and 14 after 5-FU injection to determine white blood cells (WBCs) and RBCs. n = 10 from two independent experiments. (H) Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice and littermate control mice were injected with 250 mg/kg 5-FU i.p. for three times at an 11-d interval, and survival was monitored daily. A Kaplan-Meier survival curve of mice after 5-FU injury is shown. Time points of 5-FU injections are indicated on top with purple arrows. n = 10 from two independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

The appreciable proliferation potential of the Etv2-deficient HSPC population (KSL; Fig. 2, A and C) suggested that peripheral blood (PB) might recover relatively normally in Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO after 5-FU injury. Indeed, complete blood cell count data showed no substantial differences of the PB cell recovery between Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO and control mice after 5-FU injection (Fig. 2, F and G). BM and PB lineage analysis also showed that the frequency of B cells (B220+), T cells (CD3+), and myeloid cells (Gr1+ and Mac1+) was comparable between Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO and littermate controls (not depicted). However, we noticed that white blood cell counts in Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKOs were lower at day 14 after 5-FU injury (Fig. 2 F). Moreover, about one half of the 5-FU–injected Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice, but not control mice, died after repeated blood drawing for PB analysis (not depicted). As the most primitive hematopoietic cell population displayed a notable defect in cell cycle/proliferation, it was possible that Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice might not manage stress requiring continued hematopoietic regeneration. Thus, we tested whether Etv2-deficient HSC proliferation defects could be manifested by repeated 5-FU injury. Specifically, we applied serial injection of 250 mg/kg 5-FU at an 11-d interval, an interval that showed maximal HSPC expansion in WT mice (Fig. 2, A–D), to continuously induce HSCs into cell cycle/proliferation. Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice started to die after the second 5-FU injection, and all mice died after the third 5-FU injection. In contrast, less than half of the control mice died after the third 5-FU injection (Fig. 2 H). At a less cytotoxic dose of 5-FU (150 mg/kg), 1 out of 10 Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice died after the third 5-FU injection, whereas none of the littermate control mice died (not depicted). At a lower 5-FU dose (150 mg/kg), ROS levels were not significantly elevated in HSPCs, and Etv2-deficient HSPCs proliferated comparably with those from littermate controls (not depicted). These data suggested that, at extreme hematopoietic stress conditions, Etv2-deficient HSPCs, being defective in proliferative potential, might not meet the demands of rapid restoration of the hematopoietic system.

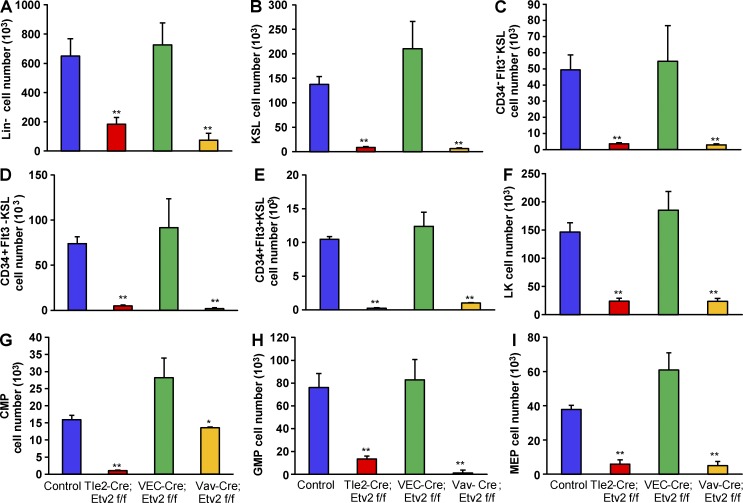

To determine that the effect of Etv2 on HSPC proliferation was hematopoietic cell intrinsic, we assessed the hematopoietic regeneration potential of Vav-Cre;Etv2f/f (Vav-Cre;Etv2 CKO) and VECadherin-Cre;Etv2f/f (VEC-Cre;Etv2 CKO) mice, which lack Etv2 in hematopoietic and endothelial cells, respectively (Park et al., 2016). Etv2 deletion was confirmed in BM CD45+ as well as KSL cells in both Vav-Cre;Etv2 and Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice but not in VEC-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice (not depicted). Additionally, complete Etv2 deletion was observed in CD31+CD45− endothelial cells isolated from Tie2-Cre;Etv2 or VEC-cre;Etv2 CKO lungs (not depicted). Etv2 deletion in KSL cells was not complete in Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice, even though these mice showed significantly diminished hematopoietic regeneration capacity. After 5-FU injury, BM cellularity was similar between control and CKO mice (not depicted). Importantly, Vav-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice displayed similar HSPC recovery defects compared with Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice. VEC-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice exhibited comparable HSPC recovery as control mice (Fig. 3). These data suggest that hematopoietic Etv2 but not endothelial Etv2 is required for HSPC regeneration after 5-FU injury.

Figure 3.

Hematopoietic but not endothelial deletion of Etv2 impairs HSPC recovery after 5-FU treatment. (A–I) Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO, VEC-Cre;Etv2 CKO, Vav-Cre;Etv2 CKO, or littermate control mice were injected with 250 mg/kg 5-FU i.p. After 11 d, BM mononuclear cells were subjected to flow cytometry by using HSPC surface markers to determine absolute cell number (per femur and tibia) of different hematopoietic compartments. (A) Lin− cells. (B) KSL (c-Kit+Sca1+Lin−) cells. (C) Long-term HSCs (CD34−Flt3− KSL). (D) Short-term HSCs (CD34+Flt3− KSL). (E) Multipotent progenitor (CD34+Flt3+ KSL) cells. (F) LK (c-Kit+Sca1−Lin−) cells. (G) Common myeloid progenitor (CMP; CD34+CD16/32− LK) cells. (H) Granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (GMP; CD34+CD16/32+ LK) cells. (I) Megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitor (MEP; CD34−CD16/32− LK) cells. n = 4–6 from two independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

Hematopoietic Etv2 but not endothelial Etv2 is essential for hematopoietic reconstitution after transplantation

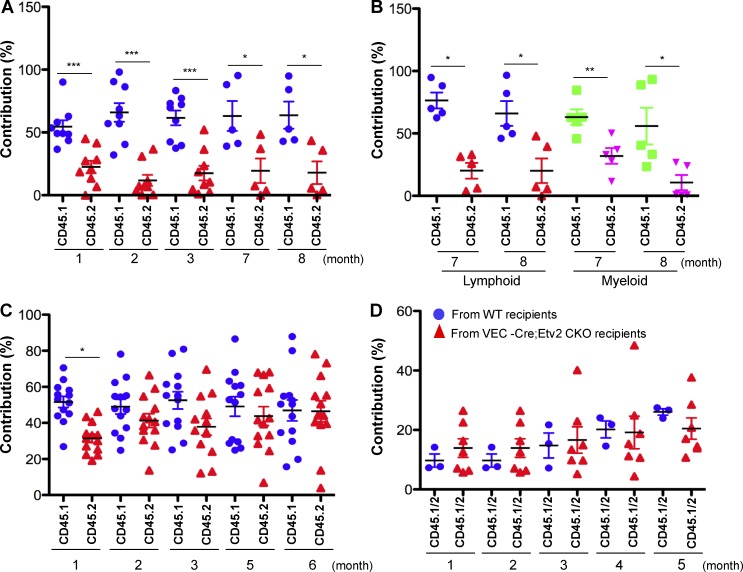

To further validate the hematopoietic cell–intrinsic role of Etv2 in HSPC regeneration, we used BM transplantation, which stimulates continuous long-term proliferation of HSPCs (Sun et al., 2014; Busch et al., 2015; Säwén et al., 2016), to assess Etv2-deficient HSPCs for their hematopoietic reconstitution potential. Specifically, we performed competitive transplantation experiments by mixing KSL cells from Vav-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice (CD45.2) and WT mice (CD45.1) at a 1:1 ratio and injecting them into lethally irradiated recipients (CD45.1 × 45.2). Vav-Cre;Etv2 CKO KSL cells (CD45.2) showed very low PB contribution compared with competitive controls (Fig. 4, A and B). Vav-Cre;Etv2 CKO BM cells from the primary recipients showed similar defects in hematopoietic reconstitution in secondary transplantation (not depicted). Whole BM transplantation using Vav-Cre;Etv2 CKO (CD45.2) and WT (CD45.1) mice (1:1 ratio) again showed very low PB contribution from Vav-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice compared with controls (not depicted). Etv2-deficient HSPCs displayed similar homing ability compared with WT HSPCs when injected retroorbitally and analyzed 4 h and 2 d after transplantation (not depicted). These data indicated that hematopoietic Etv2 was required for hematopoietic reconstitution after transplantation.

Figure 4.

Hematopoietic but not endothelial deletion of Etv2 results in decreased hematopoietic reconstitution capacity. (A and B) 10,000 KSL cells from Vav-Cre;Etv2 CKO or littermate control mice (both are CD45.2) were transplanted along with 106 competitor BM cells (CD45.1) into lethally irradiated WT recipient mice (CD45.1 × CD45.2). PB from recipients was analyzed for donor-derived contribution by determining the percentage of CD45.1+ and CD45.2+ PB leukocyte or lymphoid (B220+/CD3+ or myeloid Gr1+) at the indicated time points after transplantation. n = 5–8 from two independent transplantations. (C) 106 BM cells from VEC-Cre;Etv2 CKO or littermate control mice (both are CD45.2) were transplanted along with 106 competitor BM cells (CD45.1) into lethally irradiated WT recipient mice (CD45.1 × CD45.2). PB from recipients was analyzed for donor-derived contribution by determining the percentage of CD45.1+ and CD45.2+ PB leukocytes at the indicated time points after transplantation. n = 10–13 from three independent transplantations. (D) 2 × 106 WT BM cells (CD45.1 × CD45.2) were transplanted into lethally irradiated WT or VEC-Cre;ETV2 CKO recipients (both are CD45.2). 6 mo after transplantation, 2 × 106 BM cells (CD45.1 × CD45.2) recovered from WT or VEC-Cre;ETV2 CKO recipients were transplanted along with 5 × 105 competitor BM cells (CD45.1) into lethally irradiated recipient mice (CD45.2). PB was analyzed for donor-derived contribution by determining the percentage of CD45.1+CD45.2+ PB leukocytes at the indicated time points after transplantation. n = 3–6 from two independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To enforce the notion that Etv2 was required for the HSC-intrinsic manner, we performed competitive hematopoietic reconstitution studies by using VEC-Cre;Etv2 CKO BM (CD45.2) and WT BM (CD45.1) cells (1:1 ratio) and lethally irradiated recipient mice (CD45.1 × 45.2). PB analysis showed that VEC-Cre;Etv2 CKO BM cells (CD45.2) had comparable contribution to PB compared with controls (Fig. 4 C). To further validate that endothelial Etv2 was dispensable for HSPC regeneration potential, we additionally performed transplantation studies using WT BM (CD45.1 × 45.2) as the donor and lethally irradiated WT (CD45.2) or VEC-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice (CD45.2) as recipients. 6 mo later, WT donor BM (CD45.1 × 45.2) was recovered from the WT or VEC-Cre;Etv2 CKO–recipient mice, mixed with fresh WT BM (CD45.1) in a ratio of 4:1, and transplanted into lethally irradiated recipients (CD45.2). PB analysis showed that WT BM (CD45.1 × 45.2) recovered from the VEC;Etv2 CKO mice had similar contribution compared with the WT BM (CD45.1 × 45.2) recovered from the WT mice (Fig. 4 D). These data demonstrate that endothelial Etv2 was not required for maintaining HSPC function.

c-KIT signaling is downstream of ETV2 in promoting HSPC proliferation and recovery from 5-FU injury

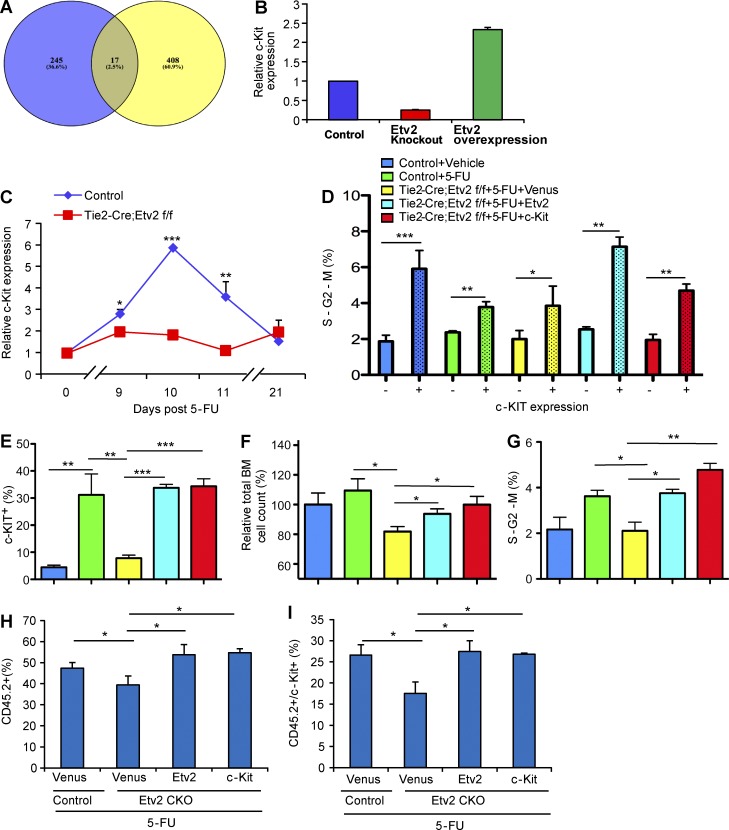

To understand the molecular mechanisms by which Etv2 regulates HSC regeneration, we examined previously published chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-Seq) and microarray data (Liu et al., 2012, 2015) focusing on the genes in the regulation of cell proliferation categories. A great fraction of the ETV2 ChIP-Seq peaks were associated with genes annotated as regulation of cell proliferation by gene ontology (McLean et al., 2010), whose expression also changed by ETV2 status (Fig. 5 A). Among these, c-Kit expression was greatly up-regulated by enforced Etv2 expression, whereas its expression was significantly decreased by Etv2 deficiency (Fig. 5 B). ChIP-Seq data also identified potential ETV2 binding sites in the c-Kit locus (Fig. S2), suggesting that c-Kit is downstream of ETV2. Thus, we determined whether ETV2-mediated c-Kit up-regulation was required for hematopoietic regeneration after BM injury. FACS analyses of the recovering BM after 5-FU injury demonstrated that c-KIT expression was dramatically up-regulated in Lin− cells during the regeneration phase in control mice (Fig. 5 C). Notably, its expression returned to normal levels once the hematopoietic system was restored, i.e. day 21. However, c-KIT expression levels in Lin− cells remained low during the recovery phase in Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO BM (Fig. 5 C). Baseline c-KIT expression in steady state was similar (not depicted). In culture, c-KIT+ cells had much higher proliferation rate than c-KIT− cells (Fig. 5 D). This suggested that Etv2 deficiency leads to defects in c-Kit up-regulation and c-KIT–mediated HSPC proliferation. To determine whether Etv2-mediated c-KIT up-regulation was indeed required for HSPC proliferation and hematopoietic regeneration after BM injury, we tested whether c-Kit expression could rescue the HSPC proliferation defects of the Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO BM. To this end, Tie2-Cre;Etv2 BM cells were isolated 8 d after 5-FU injury and infected with Etv2 or c-Kit lentivirus, and c-KIT expression, proliferation, and cell cycle of the infected cells were analyzed. As expected, Etv2 lentiviral infection dramatically rescued the frequency and numbers of c-KIT+ cells (Fig. 5, E–G). Moreover, c-Kit lentiviral infection also led to increased c-KIT+ cell frequency and numbers from the Etv2-deficient BM. To determine whether the rescue of the cell-surface phenotype, c-KIT+ cells, indeed reflected the functional rescue of the proliferation defects, we assessed BM cell recovery as well as the cell-cycle status of the c-Kit–infected cells. BM cell recovery and proliferation were significantly improved by Etv2 or c-Kit expression in Etv2-deficient BM (Fig. 5, E–G). Moreover, Etv2-deficient BM cells yielded a much higher percentage of cells in the S-G2-M phase after Etv2 or c-Kit lentiviral infection (Fig. 5 G). As expected, highly proliferating cells, i.e. cells in the S-G2-M phase, were enriched within c-KIT+ cells generated by Etv2 or c-Kit expression (Fig. 5 D). To determine whether c-Kit could rescue Etv2-deficient HSC defects in vivo, we collected Etv2-deficient BM cells 7 d after 5-FU injury (CD45.2), infected them with Venus, Etv2, or c-Kit lentivirus, transplanted them into lethally irradiated recipient mice (CD45.1) together with mock-infected WT BM (CD45.1), and then analyzed them 3 d later for the total BM contribution and c-KIT+ cells generated. As shown (Fig. 5, H and I; and Fig. S3), total donor contribution (CD45.2+) as well as CD45.2+c-KIT+ cells were increased by either Etv2 or c-Kit expression compared with Venus control. These data collectively support the notion that c-KIT–mediated HSPC proliferation was integral to ETV2-mediated BM recovery after injury.

Figure 5.

c-Kit is an ETV2 downstream target and responsible for ETV2-mediated HSPC recovery after 5-FU treatment. (A) Among 121 genes that were identified as putative direct targets of ETV2 in differentiated embryonic stem cells by Liu et al. (2015), 17 genes, including c-Kit, were annotated as genes related to regulation of cell proliferation. P-value was estimated using hypergeometric distribution. (B) Relative c-Kit expression levels, determined by microarray, in control, Etv2−/−, or Etv2-overexpressing embryoid body (in vitro differentiated embryonic stem) cells is shown (Liu et al., 2012). n = 2. (C) Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO or littermate control mice were injected with 250 mg/kg 5-FU i.p. At days 0, 9, 10, 11, and 21, flow cytometry with surface marker staining was performed to determine c-KIT expression levels on Lin− cells after 5-FU injury. Data are expressed as a relative c-KIT expression normalized to the littermate control day-0 group. n = 3–5 from two independent experiments. (D–G) Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO or littermate control mice were injected with 250 mg/kg 5-FU. BM mononuclear cells were collected 8 d later and infected with Venus, Etv2, or c-Kit lentivirus for 1 d, followed by cell count and flow cytometry analysis. Cell count was determined by using the CCK8 kit. Five different experimental groups are shown. Blue, control (no 5-FU); green, control + 5-FU; yellow, Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO + 5-FU + lentivirus-Venus (Venus expressing control lentivirus); cyan, Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO + 5-FU + lentivirus Etv2; and red, Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO + 5-FU + lentivirus c-Kit. (D) The percentage of c-KIT− and c-KIT+ cells in the S-G2-M phase in each group is shown. n = 9 from three independent experiments. (E) The frequency of c-KIT–positive cell population in each group is shown. n = 9 from three independent experiments. (F) The relative percentage of the cell counts in each group normalized to control (no 5-FU injury) is shown. n = 9 from three independent experiments. (G) The percentage of cells in the S-G2-M phase in each group is shown. n = 9 from three independent experiments. (H and I) Tie2-Cre;Etv2f/f or littermate control mice (CD45.2) were injected with 250 mg/kg 5-FU i.p. 7 d after injection, and 20,000 BM mononuclear cells were isolated and seeded onto a V-shape 96-well plate and infected with either lenti-Venus, -Etv2, or –c-Kit. Littermate control BM mononuclear cells were infected with lenti-Venus only. On the second day, cells were transplanted into 9 Gy–irradiated recipient mice (CD45.1) together with 20,000 mock-infected WT BM cells (CD45.1). Donor contribution (CD45.2) and c-Kit–positive cells from BM were analyzed by flow cytometry with surface marker and CD45.1 and CD45.2 3 d after transplantation. n = 6 from two independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

In the present study, we uncover the unexpected role of Etv2 in hematopoietic regeneration. Upon hematopoietic injury, we discover that ROS levels are transiently increased in HSPCs and that Etv2 becomes transiently reactivated in HSPCs. Inhibition of ROS was sufficient to block Etv2 activation in HSPCs upon injury. Etv2 was necessary to ensure efficient hematopoietic regeneration after hematopoietic injury. As such, we propose that although Etv2 is dispensable for maintaining HSCs in steady states, it is required for emergency hematopoiesis. Surprisingly, despite its critical role in vascular regeneration (Park et al., 2016), we found that Etv2 was dispensable in the endothelial cell niche for maintaining HSCs in the steady state or injury.

Recent studies have established that ROS is critical for tissue regeneration. In particular, in the Xenopus tadpole tail regeneration model, tail amputation leads to rapid ROS production, which activates Wnt/β-catenin and FGF20 signaling and tail regeneration (Love et al., 2013). In the zebrafish fin–amputation regeneration model, ROS is again rapidly produced in regenerating tissue and triggers compensatory proliferation of stump epidermal cells (Gauron et al., 2013). ROS positively regulate mouse spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal through stress kinases p38 MAPK and JNK pathways (Morimoto et al., 2013). ROS is also required for neuroregeneration in newts and planarian (Hameed et al., 2015; Pirotte et al., 2015). Intriguingly, ROS role in HSCs seem controversial (Ito et al., 2006; Ludin et al., 2014; Walter et al., 2015; Itkin et al., 2016). In particular, activation of the ROS–p38 MAPK pathway appears to be detrimental for HSCs (Ito et al., 2006; Walter et al., 2015). However, a conditional p38α deletion study has revealed that it is necessary for HSC regeneration in stress response (Karigane et al., 2016). It is important to note that ROS levels were transiently elevated in HSPCs during regeneration phase, which might be the key to successful HSC regeneration. Future studies will require detailed mechanistic understanding of ROS and Etv2 activation in relationship to p38 MAPK that contributes to hematopoietic regeneration.

KIT ligand and c-KIT interaction between the stromal niche and HSCs is critical for maintaining HSPCs in adults (Geissler et al., 1988; Huang et al., 1990; Matsui et al., 1990; Thorén et al., 2008; Kimura et al., 2011; Ding et al., 2012). Importantly, c-KIT levels on HSCs determine the outcome of the HSC fate (Grinenko et al., 2014; Shin et al., 2014). Specifically, HSCs expressing high levels of c-KIT cannot contribute to long-term hematopoietic reconstitution, as they proliferate more robustly and differentiate upon transplantation. However, HSCs with low levels of c-KIT were able to contribute to long-term hematopoietic reconstitution. Our data suggest that c-Kit is downstream of ETV2 and responsible for HSPC proliferation during hematopoietic recovery. In particular, c-KIT expression remained low in Etv2-deficient HSPCs during recovery, and the c-Kit gene delivery could rescue proliferation defects of Etv2-deficient HSPCs in vitro and in short-term BM transplantation in vivo. However, c-Kit gene delivery failed to rescue the long-term repopulation potential of Etv2-deficient HSPCs (unpublished data). This outcome is reminiscent of the studies by Shin et al. (2014) and Grinenko et al. (2014), which demonstrated that high c-KIT expression leads to deficits in long-term reconstitution potential. Presumably, lentiviral c-Kit expression in Etv2 KO KSL cells that resulted in high c-KIT expression levels might have caused rescue failure of the long-term repopulation potential. Alternatively, it is also possible that additional ETV2 downstream signaling might be required for rescue of long-term repopulation potential. Future studies on the relationship between ROS and Etv2 activation as well as c-Kit regulation mechanisms are warranted. In conclusion, our research may provide a novel potential target for improving hematopoietic recovery after chemotherapy and hematopoietic transplantation.

Materials and methods

Mice

The generation of Tie2-Cre;Etv2f/f, VEC-Cre;Etv2f/f, and Vav-Cre;Etv2f/f mice has been previously described (Park et al., 2016). In brief, Tie2-Cre;Etv2f/+, VEC-Cre;Etv2f/+, or Vav-Cre;Etv2f/+ mice were mated with Etv2f/f to obtain Tie2-Cre;Etv2f/f, VEC-Cre;Etv2f/f, or Vav-Cre;Etv2f/f mice. Cre+;Etv2f/+, Cre−;Evt2f/+, or Cre−;Etv2f/f littermates were used as controls. Animal husbandry, generation, and handling were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington University School of Medical in St. Louis. Information on genotyping primers was previously described (Park et al., 2016).

Competitive BM transplantation

Recipient mice were lethally irradiated (9.5 Gy; single dose) 1 d before cell transplantation. For primary competitive transplantation, 106 donor BM cells or 104 donor sorted HSPCs (KSL) cells (all are CD45.2) from Vav-Cre;Etv2 CKO or VEC-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice were transplanted along with 106 BM cells or 104 sorted KSL cells as competitor cells from WT mice (CD45.1). The cell suspensions in a 100-µl volume of PBS were injected into lethally irradiated recipients (CD45.1 × CD45.2) through the retroorbital sinus. In assessing Etv2 for its endothelial niche requirements, 2 × 106 WT BM cells (CD45.1 × CD45.2) were transplanted into lethally irradiated WT recipients or VEC-Cre;Etv2 CKO recipients (both are CD45.2). 6 mo after primary transplantation, BM was recovered from the primary recipients, and then, 2 × 106 BM cells (CD45.1 × CD45.2) from primary recipients were transplanted along with 5 × 105 competitor BM cells (CD45.1) through the retroorbital sinus. PB from recipients was analyzed for donor-derived hematopoiesis by determining the percentage of CD45.1+, CD45.2+, or CD45.1+/CD45.2+ PB leukocytes every 4 wk.

5-FU treatment

Control or Etv2 CKO mice were injected i.p. with a single dose of 5-FU (150 mg/kg or 250 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich) or vehicle control (sterile PBS). In serial 5-FU experiments, mice were injected (250 mg/kg each time) for three times at an interval of 11 d. Survival was monitored daily.

Complete blood cell count with differential

PB was obtained by retroorbital collection from WT or Tie2-Cre;Etv2 CKO mice at days 0, 3, 7, 10, and 14 after one dose of 250-mg/kg 5-FU injection i.p. Whole PB cell counts were analyzed using a hematology system (Hemavet 950FS; Drew Scientific).

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

BM cells were prepared by centrifuging femur and tibia at 12,000 g for 1 min. All collected cells were treated with ACK red blood cell lysis buffer (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific) before analyses. mAbs against c-Kit (2B8), Sca1 (D7), CD3e (17A2), B220 (RA3-6B2), Ter119 (TER-119), Gr1 (RB6-8C5), CD16/32 (93), CD34 (RAM34), Flt3 (A2F10), CD150 (c15-12f12.2), CD48 (HM48-1), CD45.1 (A20), CD45.2 (104), and Ki67 (B56) were purchased from BD, BioLegend, or eBioscience. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using an LSRFortessa X-20 or FACSCANTO II flow cytometer (BD).

For cell sorting, BM cells were stained with mAbs against CD3, B220, Gr1, and Ter119 lineage markers, followed by negative selection of lineage-negative cells using a magnetic-activated cell-sorting kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Lin−-enriched BM cells were stained with mAbs against lineage markers (CD3, B220, Gr1, and Ter119), c-Kit, and Sca1, and KSL cells were sorted using a FACSAria II flow cytometer (BD).

For cell cycle analysis, BM cells were stained using mAbs against c-Kit, Sca1, CD48, CD150, and lineage markers and fixed/permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD). Then, cells were stained with Ki67 and DAPI and analyzed using an LSR Fortessa X-20 or FACSCANTO II flow cytometer. Ki67−DAPI− cells were considered to be in G0, Ki67+DAPI− cells in G1, and Ki67+DAPI+ cells in S-G2-M.

KSL cell culture and ROS detection

Sorted KSL cells were cultured in 24-well tissue culture plates (20,000 cells/well) in media containing StemSpan serum-free base medium (STEMCELL Technologies), 10% serum (Hyclone), KitL (1% supernatant), Flt3L (1% supernatant), IL-3 (1% supernatant), and thrombopoietin (10 ng/ml; R&D Systems) in the presence or absence of 200 µM BSO (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 d. ROS levels were measured by flow cytometry using 1–5 µM 2′-7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA; Sigma-Aldrich) staining. Median of fluorescence intensity was used to assess the relative ROS content.

Lentiviral production and infection

293FT cells were transfected with CSII-EF-MCS-IRES-VENUS, pHIV-MND-IRES–c-Kit, or CSII-EF-MCS-IRES-Etv2, pCAG-HIVgp, and pCMV-VSV-G-RSV-Rev (4:3:1) by using the calcium phosphate method. c-Kit lentiviral vector was obtained from G. Challen (Washington University, St. Louis, MO). 16 h after transfection, the media was changed, and cells were cultured for an additional 48 h. Subsequently, supernatant was harvested and concentrated using a Lenti-X-Concentrator (Takara Bio Inc.). The virus titer was determined by the Lenti-X p24 Rapid Titer kit (Takara Bio Inc.). Virus titer was ∼3 × 107 infectious units per milliliter. 105 BM cells were seeded into a 24-well plate and infected with 106 virus particles mixed with 8 µg/ml polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich).

Quantitative RT-PCR

KSL cells sorted from control or 5-FU–treated mice were pooled and used (two to three were pooled as a sample). An RNeasy Micro kit (QIAGEN) was used for RNA extraction according to the manufacturer’s instruction. cDNA was prepared by using qScipt cDNA SuperMix (Quanta Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR primers for Etv2, Gata2, Scl, Fli1, Runx1, β-actin, and Gapdh used in this study are described in our previous studies (Liu et al., 2015; Park et al., 2016).

Statistical analysis

Student t test (Prism5; GraphPad Software) was used for statistical analysis of most in vitro and in vivo experiments. For survival analysis, log-rank test or Gehan-Breslow-Wilson test was used for statistical analysis. A p-value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows representative FACS analysis for HSPC subsets. Fig. S2 shows two potential ETV2 binding sites and the corresponding sequence within the c-Kit locus. Fig. S3 shows representative FACS analysis of c-Kit expression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Choi laboratory members for constructive criticism and discussion. We thank Dr. Grant Challen for the c-Kit lentiviral vector.

This work was supported by the American Cancer Society (grant RSG-14-049-01-DMC) and the National Institutes of Health (grants R01HG007354, R01HG007175, R01ES024992, U01CA200060, and U24ES026699 to D. Li and T. Wang; T32 training grant 5 T32 CA 9547-29 to C.-X. Xu; and grants R01HL63736 and R01HL55337 K. Choi).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: C.-X. Xu and K. Choi conceived and designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. C.-X. Xu with the help of T.J. Lee, N. Sakurai, K. Krchma, and F. Liu performed experiments and analyzed data. D. Li and T. Wang helped with microarray and ChIP-Seq data analysis.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- 5-FU

- 5-fluorouracil

- ChIP-Seq

- chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing

- HSC

- hematopoietic stem cell

- HSPC

- hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell

- NAC

- N-acetyl cysteine

- PB

- peripheral blood

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- SLAM

- signaling lymphocytic activation molecule

References

- Busch K., Klapproth K., Barile M., Flossdorf M., Holland-Letz T., Schlenner S.M., Reth M., Höfer T., and Rodewald H.R.. 2015. Fundamental properties of unperturbed haematopoiesis from stem cells in vivo. Nature. 518:542–546. 10.1038/nature14242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Val S., and Black B.L.. 2009. Transcriptional control of endothelial cell development. Dev. Cell. 16:180–195. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L., Saunders T.L., Enikolopov G., and Morrison S.J.. 2012. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 481:457–462. 10.1038/nature10783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essers M.A., Offner S., Blanco-Bose W.E., Waibler Z., Kalinke U., Duchosal M.A., and Trumpp A.. 2009. IFNα activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature. 458:904–908. 10.1038/nature07815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous A., Caprioli A., Iacovino M., Martin C.M., Morris J., Richardson J.A., Latif S., Hammer R.E., Harvey R.P., Olson E.N., et al. 2009. Nkx2-5 transactivates the Ets-related protein 71 gene and specifies an endothelial/endocardial fate in the developing embryo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:814–819. 10.1073/pnas.0807583106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauron C., Rampon C., Bouzaffour M., Ipendey E., Teillon J., Volovitch M., and Vriz S.. 2013. Sustained production of ROS triggers compensatory proliferation and is required for regeneration to proceed. Sci. Rep. 3:2084 10.1038/srep02084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler E.N., Ryan M.A., and Housman D.E.. 1988. The dominant-white spotting (W) locus of the mouse encodes the c-kit proto-oncogene. Cell. 55:185–192. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90020-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinenko T., Arndt K., Portz M., Mende N., Günther M., Cosgun K.N., Alexopoulou D., Lakshmanaperumal N., Henry I., Dahl A., and Waskow C.. 2014. Clonal expansion capacity defines two consecutive developmental stages of long-term hematopoietic stem cells. J. Exp. Med. 211:209–215. 10.1084/jem.20131115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed L.S., Berg D.A., Belnoue L., Jensen L.D., Cao Y., and Simon A.. 2015. Environmental changes in oxygen tension reveal ROS-dependent neurogenesis and regeneration in the adult newt brain. eLife. 4:e08422 10.7554/eLife.08422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang E., Nocka K., Beier D.R., Chu T.Y., Buck J., Lahm H.W., Wellner D., Leder P., and Besmer P.. 1990. The hematopoietic growth factor KL is encoded by the Sl locus and is the ligand of the c-kit receptor, the gene product of the W locus. Cell. 63:225–233. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90303-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itkin T., Gur-Cohen S., Spencer J.A., Schajnovitz A., Ramasamy S.K., Kusumbe A.P., Ledergor G., Jung Y., Milo I., Poulos M.G., et al. 2016. Distinct bone marrow blood vessels differentially regulate haematopoiesis. Nature. 532:323–328. 10.1038/nature17624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K., Hirao A., Arai F., Takubo K., Matsuoka S., Miyamoto K., Ohmura M., Naka K., Hosokawa K., Ikeda Y., and Suda T.. 2006. Reactive oxygen species act through p38 MAPK to limit the lifespan of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Med. 12:446–451. 10.1038/nm1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karigane D., Kobayashi H., Morikawa T., Ootomo Y., Sakai M., Nagamatsu G., Kubota Y., Goda N., Matsumoto M., Nishimura E.K., et al. 2016. p38α activates purine metabolism to initiate hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell cycling in response to stress. Cell Stem Cell. 19:192–204. 10.1016/j.stem.2016.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka H., Hayashi M., Nakagawa R., Tanaka Y., Izumi N., Nishikawa S., Jakt M.L., Tarui H., and Nishikawa S.. 2011. Etv2/ER71 induces vascular mesoderm from Flk1+PDGFRα+ primitive mesoderm. Blood. 118:6975–6986. 10.1182/blood-2011-05-352658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y., Ding B., Imai N., Nolan D.J., Butler J.M., and Rafii S.. 2011. c-Kit-mediated functional positioning of stem cells to their niches is essential for maintenance and regeneration of adult hematopoiesis. PLoS One. 6:e26918 10.1371/journal.pone.0026918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D., Park C., Lee H., Lugus J.J., Kim S.H., Arentson E., Chung Y.S., Gomez G., Kyba M., Lin S., et al. 2008. ER71 acts downstream of BMP, Notch, and Wnt signaling in blood and vessel progenitor specification. Cell Stem Cell. 2:497–507. 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D., Kim T., and Lim D.S.. 2011. The Er71 is an important regulator of hematopoietic stem cells in adult mice. Stem Cells. 29:539–548. 10.1002/stem.597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Kang I., Park C., Chang L.W., Wang W., Lee D., Lim D.S., Vittet D., Nerbonne J.M., and Choi K.. 2012. ER71 specifies Flk-1+ hemangiogenic mesoderm by inhibiting cardiac mesoderm and Wnt signaling. Blood. 119:3295–3305. 10.1182/blood-2012-01-403766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Li D., Yu Y.Y., Kang I., Cha M.J., Kim J.Y., Park C., Watson D.K., Wang T., and Choi K.. 2015. Induction of hematopoietic and endothelial cell program orchestrated by ETS transcription factor ER71/ETV2. EMBO Rep. 16:654–669. 10.15252/embr.201439939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love N.R., Chen Y., Ishibashi S., Kritsiligkou P., Lea R., Koh Y., Gallop J.L., Dorey K., and Amaya E.. 2013. Amputation-induced reactive oxygen species are required for successful Xenopus tadpole tail regeneration. Nat. Cell Biol. 15:222–228. 10.1038/ncb2659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludin A., Gur-Cohen S., Golan K., Kaufmann K.B., Itkin T., Medaglia C., Lu X.J., Ledergor G., Kollet O., and Lapidot T.. 2014. Reactive oxygen species regulate hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal, migration and development, as well as their bone marrow microenvironment. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 21:1605–1619. 10.1089/ars.2014.5941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui Y., Zsebo K.M., and Hogan B.L.. 1990. Embryonic expression of a haematopoietic growth factor encoded by the Sl locus and the ligand for c-kit. Nature. 347:667–669. 10.1038/347667a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean C.Y., Bristor D., Hiller M., Clarke S.L., Schaar B.T., Lowe C.B., Wenger A.M., and Bejerano G.. 2010. GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat. Biotechnol. 28:495–501. 10.1038/nbt.1630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto H., Iwata K., Ogonuki N., Inoue K., Atsuo O., Kanatsu-Shinohara M., Morimoto T., Yabe-Nishimura C., and Shinohara T.. 2013. ROS are required for mouse spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 12:774–786. 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus H., Müller F., and Hollemann T.. 2010. Xenopus er71 is involved in vascular development. Dev. Dyn. 239:3436–3445. 10.1002/dvdy.22487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C., Lee T.J., Bhang S.H., Liu F., Nakamura R., Oladipupo S.S., Pitha-Rowe I., Capoccia B., Choi H.S., Kim T.M., et al. 2016. Injury-mediated vascular regeneration requires endothelial ER71/ETV2. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 36:86–96. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirotte N., Stevens A.S., Fraguas S., Plusquin M., Van Roten A., Van Belleghem F., Paesen R., Ameloot M., Cebrià F., Artois T., and Smeets K.. 2015. Reactive oxygen species in planarian regeneration: An upstream necessity for correct patterning and brain formation. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015:392476 10.1155/2015/392476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen T.L., Kweon J., Diekmann M.A., Belema-Bedada F., Song Q., Bowlin K., Shi X., Ferdous A., Li T., Kyba M., et al. 2011. ER71 directs mesodermal fate decisions during embryogenesis. Development. 138:4801–4812. 10.1242/dev.070912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salanga M.C., Meadows S.M., Myers C.T., and Krieg P.A.. 2010. ETS family protein ETV2 is required for initiation of the endothelial lineage but not the hematopoietic lineage in the Xenopus embryo. Dev. Dyn. 239:1178–1187. 10.1002/dvdy.22277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Onai N., Yoshihara H., Arai F., Suda T., and Ohteki T.. 2009. Interferon regulatory factor-2 protects quiescent hematopoietic stem cells from type I interferon–dependent exhaustion. Nat. Med. 15:696–700. 10.1038/nm.1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Säwén P., Lang S., Mandal P., Rossi D.J., Soneji S., and Bryder D.. 2016. Mitotic history reveals distinct stem cell populations and their contributions to hematopoiesis. Cell Reports. 14:2809–2818. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J.Y., Hu W., Naramura M., and Park C.Y.. 2014. High c-Kit expression identifies hematopoietic stem cells with impaired self-renewal and megakaryocytic bias. J. Exp. Med. 211:217–231. 10.1084/jem.20131128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumanas S., and Choi K.. 2016. ETS transcription factor ETV2/ER71/Etsrp in hematopoietic and vascular development. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 118:77–111. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2016.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumanas S., and Lin S.. 2006. Ets1-related protein is a key regulator of vasculogenesis in zebrafish. PLoS Biol. 4:e10 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumanas S., Gomez G., Zhao Y., Park C., Choi K., and Lin S.. 2008. Interplay among Etsrp/ER71, Scl, and Alk8 signaling controls endothelial and myeloid cell formation. Blood. 111:4500–4510. 10.1182/blood-2007-09-110569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Ramos A., Chapman B., Johnnidis J.B., Le L., Ho Y.J., Klein A., Hofmann O., and Camargo F.D.. 2014. Clonal dynamics of native haematopoiesis. Nature. 514:322–327. 10.1038/nature13824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorén L.A., Liuba K., Bryder D., Nygren J.M., Jensen C.T., Qian H., Antonchuk J., and Jacobsen S.E.. 2008. Kit regulates maintenance of quiescent hematopoietic stem cells. J. Immunol. 180:2045–2053. 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter D., Lier A., Geiselhart A., Thalheimer F.B., Huntscha S., Sobotta M.C., Moehrle B., Brocks D., Bayindir I., Kaschutnig P., et al. 2015. Exit from dormancy provokes DNA-damage-induced attrition in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 520:549–552. 10.1038/nature14131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wareing S., Mazan A., Pearson S., Göttgens B., Lacaud G., and Kouskoff V.. 2012. The Flk1-Cre-mediated deletion of ETV2 defines its narrow temporal requirement during embryonic hematopoietic development. Stem Cells. 30:1521–1531. 10.1002/stem.1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.