Djaoud et al. show that Epstein–Barr virus infection triggers two types of human innate immune response, one mediated by the combination of NK cells and γδ T cells and the other committed to a strong NK cell response with little involvement of γδ T cells.

Abstract

Most humans become infected with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), which then persists for life. Infrequently, EBV infection causes infectious mononucleosis (IM) or Burkitt lymphoma (BL). Type I EBV infection, particularly type I BL, stimulates strong responses of innate immune cells. Humans respond to EBV in two alternative ways. Of 24 individuals studied, 13 made strong NK and γδ T cell responses, whereas 11 made feeble γδ T cell responses but stronger NK cell responses. The difference does not correlate with sex, HLA type, or previous exposure to EBV or cytomegalovirus. Cohorts of EBV+ children and pediatric IM patients include both group 1 individuals, with high numbers of γδ T cells, and group 2 individuals, with low numbers. The even balance of groups 1 and 2 in the human population points to both forms of innate immune response to EBV having benefit for human survival. Correlating these distinctive responses with the progress of EBV infection might facilitate the management of EBV-mediated disease.

Introduction

EBV, an endemic herpesvirus, infects more than 90% of the human population worldwide. Usually contracted during early childhood, EBV is subsequently carried for life as an asymptomatic latent infection. However, if the primary infection is delayed, it can give rise to infectious mononucleosis (IM), a transient but often debilitating condition. More severe are the malignant diseases caused by EBV, the first human tumor virus identified (Epstein et al., 1964). These cancers include Burkitt lymphoma (BL), Hodgkin disease, and lymphomas associated with AIDS or transplantation (Young and Rickinson, 2004).

Main targets for EBV infection are epithelial cells and B lymphocytes. In vivo, EBV infection of B cells is controlled by the human host’s immune system. Consequently, only some EBV-infected cells survive to become long-lived memory B cells. In these cells, viral gene expression is turned off, giving a form of latent infection termed “latency 0.” When EBV-infected memory B cells divide, the Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) protein is expressed. It links viral episomes to host chromosomes, enabling the viral genome to be replicated along with that of the human host. This form of latent infection, termed “latency I,” also characterizes BL (Hochberg et al., 2004).

Induction of the lytic cycle in latently infected B cells requires expression of the viral immediate-early protein BZLF1 (Countryman et al., 1987). Although the physiological stimuli that trigger in vivo reactivation of EBV are poorly understood, reactivation of EBV in some BL cell lines can be achieved in vitro by cross-linking the BCR with anti-BCR antibodies (Takada et al., 1991).

In the infected human host, EBV induces a diverse cellular immune response. CD8 T cells, specific for lytic and latent viral antigens, are prominent in controlling EBV in vivo (Hislop et al., 2007). In establishing latent infection, EBV uses various mechanisms to prevent T cell recognition of infected cells. During the lytic cycle, EBV impedes expression of HLA class I and II (Keating et al., 2002), as well as translocation of viral peptides to the endoplasmic reticulum by transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP; Ressing et al., 2005). Studying mice with a humanized immune system (Chijioke et al., 2013) showed how NK cells can control primary EBV infection, by limiting viral load and preventing progression to EBV-induced malignancy. That the peripheral blood of IM patients contains abnormally high numbers of NK cells (Williams et al., 2005; Azzi et al., 2014) points to a crucial role for NK cells in the immune response to EBV.

Several studies on genetic disorders affecting T cells, NK cells, invariant NKT (iNKT) cells, or innate lymphoid cells have explored the potential protective effect of these immune compartments on viral infections including EBV (Sayos et al., 1998; van Montfrans et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014; Vély et al., 2016). However, an outstanding question is how the innate immune response to EBV differs between symptomatic and asymptomatic primary infections among healthy humans. In response to EBV, a preferential expansion of NKG2A+KIR− NK cells has been observed (Azzi et al., 2014; Hatton et al., 2016), but the phenotypic and functional diversity of these and other responding innate lymphocytes has yet to be explored in detail. To address this question, we studied the response of NK cells, γδ T cells, and other innate immune cells to BL cells.

Results

NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells proliferate in response to latently infected EBV+ B cells

Down-regulation of host HLA class I is a strategy EBV uses to evade virus-specific cytotoxic T cells (Ressing et al., 2005). A possible side effect of this ploy is that EBV-infected cells become more vulnerable to attack by NK cells, which actively respond to loss of autologous HLA class I. To explore this possibility, we studied the NK cell response to Akata, a BL cell line that is latently infected with EBV but can be induced to enter the lytic cycle by cross-linking its BCR with IgG-specific antibody. For the negative control, we used a derivative of Akata that is EBV−. The efficiency of EBV reactivation was determined by intracellular staining for the EBV protein BZLF1.

The response of human PBMCs to EBV− and EBV+ Akata cells, either preincubated or not with anti-IgG, was compared. To avoid bias caused by HLA class I or killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) ligand mismatch, we studied NK cells from three donors who shared the Bw4 and C1 epitopes with Akata, as well as individual HLA-A, -B, and -C allotypes (Table 1). With this experimental design, we could determine which cellular responses are specific to EBV and how latent and lytic EBV infections affect the response. From the results of a previous study (Williams et al., 2016), we expected that NK cell responses to lytic infection would be greater than those to latent infection.

Table 1. HLA-A, -B, and -C genotypes of the Akata cell line and donors 1, 2, and 3.

| Name | HLA-A | A Bw4 | HLA-B | B Bw4 | HLA-C | C1/C2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akata | A*24 | A*31 | + | − | B*35 | B*51 | + | + | C*03 | C*14 | C1 | C1 |

| Donor 1 | A*24 | A*02 | + | − | B*35 | B*51 | + | + | C*03 | C*15 | C1 | C2 |

| Donor 2 | A*24 | A*02 | + | − | B*52 | B*51 | + | + | C*12 | C*14 | C1 | C1 |

| Donor 3 | A*24 | A*24 | + | + | B*52 | B*51 | + | + | C*12 | C*14 | C1 | C1 |

Five million PBMCs from each donor were cultured with the two subclones of Akata, either preincubated or not with anti-IgG. After 10 d of culture, flow cytometry was used to assess the proliferation of B cells (CD20+), NK cells (CD20−CD3−CD56+), αβ T cells (CD3+γδTCR−), and γδ T cells (CD3+γδTCR+). Akata cells were killed in all cultures. NK cell proliferation was higher in cultures with latent EBV+ Akata cells than in cultures with EBV− Akata, whether preincubated or not with anti-IgG (P < 0.001), or in those with lytic EBV+ Akata (P < 0.001). Similar expansions of NK cells were seen for each donor, and the results were reproducible in three independent experiments. In all cultures with latent EBV+ Akata cells, the NK cell number rose by >60 fold, resulting in ∼30 million cells, accounting for ∼40% of all cells (Fig. 1, A and B).

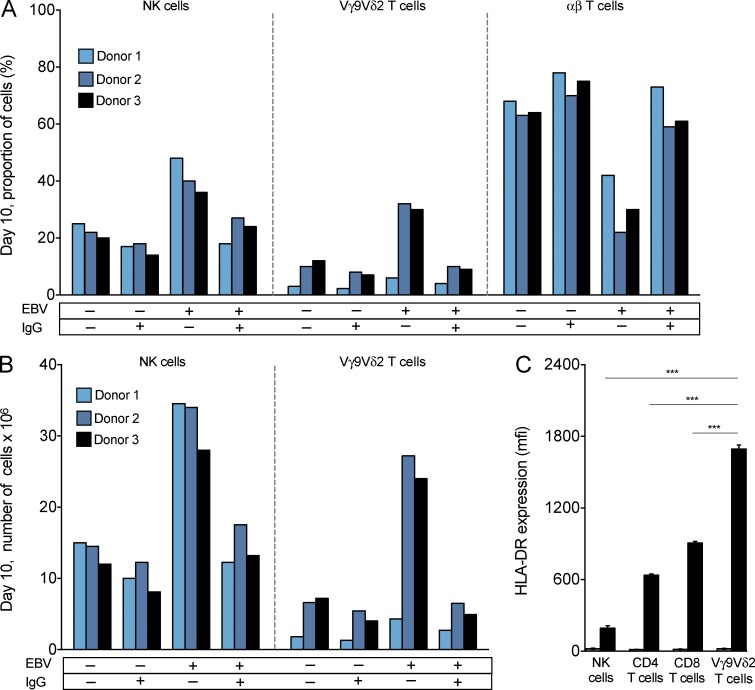

Figure 1.

NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells proliferate in response to latently infected EBV+ B cells. PBMCs were stimulated in culture for 10 d with IL2 and target cells. The targets were either EBV+ (denoted EBV +) or EBV− (denoted EBV −) Akata. They were either stimulated with anti-IgG (denoted IgG +) or not stimulated (denoted IgG −). (A) For day 10 cultures, histograms show the percentage of total cell number that were NK cells, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, and αβ T cells. Shown are the results from one experiment, representing three performed. (B) Histograms show the absolute numbers of NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in day 10 cultures. Shown are the results from one experiment, representing three performed. (C) Histogram comparing the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI ± SD; n = 4) for HLA-DR expression by NK cells, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, CD4 T cells, and CD8 T cells at day 0 (gray bars) and day 10 (black bars) of PBMC stimulation with latent EBV+ Akata and IL2. Shown are the results from one experiment, representing four performed, two on donor 2 PBMCs and two on donor 3 PBMCs. Statistical significance in the difference between pairs of cell types was tested using ANOVA. Statistically significant differences (***, P < 0.0001) were observed between Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and each of the other three cell types.

Vigorous γδ T cell responses to latent EBV+ Akata were observed for donors 2 and 3, but not for donor 1. The proliferating γδ T cells express the Vγ9Vδ2 receptor. In PBMCs, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells typically constitute <5% of CD3+ T cells. After 10 d of culture with latent EBV+ Akata, the number of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells increased >500-fold, giving >20 million cells, comprising >20% of all cells (Fig. 1, A and B). This impressive proliferation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in response to latent EBV+ Akata cells was both unexpected and never observed for the Vγ9Vδ2 T cells of donor 1. Nor was it observed in cultures with EBV− Akata or lytic EBV+ Akata. For each donor, reproducible results were obtained in three independent experiments. Inversely correlating with the proportions of NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, the proportion of αβ T cells was high in all cell cultures, except for those with latent EBV+ Akata (Fig. 1, A and B).

In conclusion, these results implicate NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells as major players in the innate immune defense against EBV. Moreover, latent EBV infection stimulates greater proliferation of NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells than lytic EBV infection.

Amplified Vγ9Vδ2 T cells activated by EBV express a high level of HLA-DR

Because antigen-activated T cells and NK cells are known to up-regulate HLA-DR expression (Salgado et al., 2002; Evans et al., 2011), we determined whether the NK and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells that respond to Akata also up-regulate HLA-DR. For proliferating populations of NK cells, CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, cell-surface HLA-DR was much increased on day 10 compared with day 0. The Vγ9Vδ2 T cells achieved significantly higher HLA-DR expression than other lymphocyte populations (Fig. 1 C), indicating that these Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are highly activated. Combining these data with additional flow cytometric analysis showed that activated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells have a surface phenotype that is CD3+HLA-DR+CD56+/− and CD4−CD8−CD16−CD19−CD21−. Oyoshi et al. (2003) described Vγ9Vδ2 T cell lines of similar phenotype, which they established from PBMCs of patients with chronic active EBV infection. That these lines were EBV infected suggested that our Akata-activated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells could be similarly infected. To assess this possibility, the EBV-activated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were assayed for presence of viral DNA encoding EBNA1. Whereas EBNA1 encoding DNA was successfully amplified from EBV+ Akata, it was not detected in any Vγ9Vδ2 T lymphocyte population or EBV− Akata (unpublished data). Thus, the in vitro–derived Vγ9Vδ2 T cell lines obtained in our experiments are not infected with EBV and therefore differ from those derived from patients with chronic active EBV infection.

To define in detail the surface phenotypes of the NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells that respond to EBV+ Akata, we performed mass cytometric analysis of unstimulated (day 0) and stimulated (day 10) cells, using a panel of 31 mAbs that target hematopoietic cell lineage markers and a variety of NK cell receptors (Table S1). The gating used to identify and distinguish NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells is shown in Fig. S1.

EBV-stimulated NK cells exhibit a phenotype of early differentiation that is independent of CMV status

IM patients have an expanded population of CD56dim NK cells that express CD94:NKG2A, the inhibitory HLA-E receptor, and lack self-reactive KIR (Azzi et al., 2014). On the other hand, individuals infected with CMV, another common endemic herpesvirus, have an expanded population of NK cells that coexpress CD94:NKG2C, the activating HLA-E receptor, and inhibitory KIR that recognize self HLA class I (Béziat et al., 2012; Foley et al., 2012; Djaoud et al., 2013). To see whether CMV infection influences the NK cell response to EBV, we compared the expression of NKG2A and C1-specific KIR2DL2/3 on Akata-activated NK cells from three donors: CMV+ donor 3 and CMV− donors 1 and 2 (Fig. 2 A).

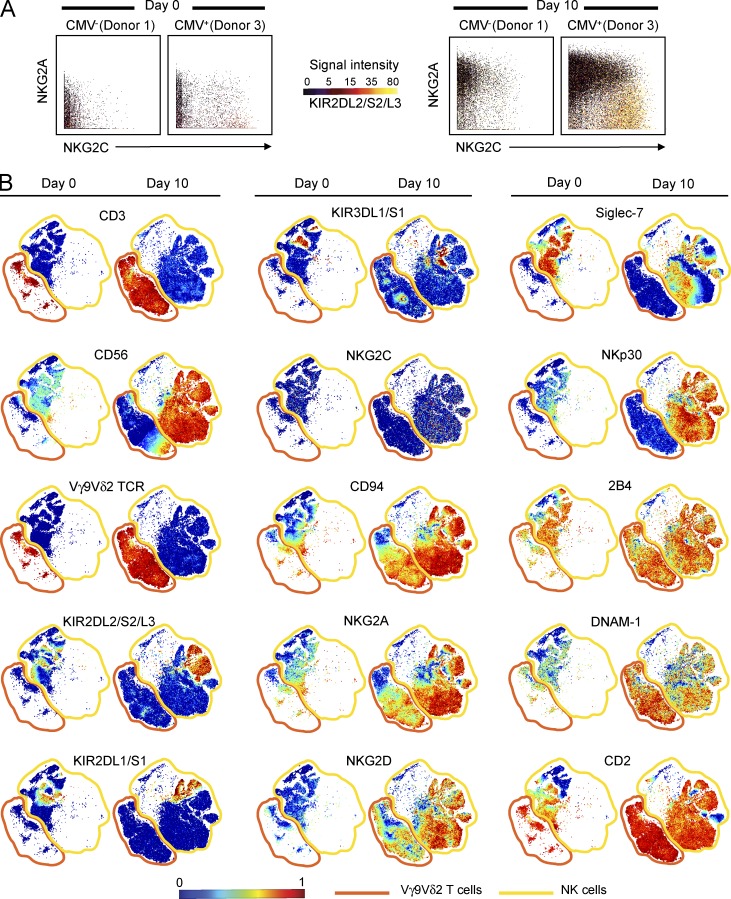

Figure 2.

EBV-stimulated NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells exhibit similar phenotypes of early differentiation. (A) Representative 3D plots showing the expression pattern of NKG2A, NKG2C, and KIR2DL3 by NK cells. NKG2A expression is given on the y axis, NKG2C expression on the x axis, and KIR2DL/3 expression by the color of the data points, as depicted under signal intensity. Analyzed are the day 0 and 10 cultures of PBMCs, from CMV− (donor 1) and CMV+ (donor 3) individuals, that were stimulated with Akata and IL2. Shown are the results from one experiment, representing three performed. (B) Representative viSNE maps of NK and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells at day 0 and NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells that proliferated during a 10-d stimulation of PBMCs with Akata cells and IL2. Each point in the viSNE map represents one cell; the points are colored to reflect the expression level of the indicated protein. Shown are the results from one experiment, representing three performed.

For all three donors, the major population of proliferating NK cells was the KIR−NKG2C−NKG2A+ cells. During the 10 d of culture with EBV, KIR−NKG2C−NKG2A+ NK cells increased their representation in the total NK cell population from 45 to 85% for donor 1, from 35 to 83% for donor 2, and from 25 to 80% for donor 3. Consistent with previous observations (Béziat et al., 2012; Foley et al., 2012; Djaoud et al., 2013), donor 3 had an expanded population of KIR+NKG2C+NKG2A− NK cells, the consequence of CMV infection, which was not present in donors 1 and 2. On day 0, KIR+NKG2C+NKG2A− NK cells were 10% of donor 3’s NK cells, and this increased to 13% on day 10. Challenge with EBV was thus seen to stimulate a modest activation and proliferation of donor 3’s KIR+NKG2C+NKG2A− NK cells. Although their representation increased by 3%, that of the KIR−NKG2C−NKG2A+NK cells increased by 55% (Fig. 2 A).

From this comparison of one CMV+ and two CMV− donors, we conclude that expansion of NKG2C+KIR+NK cells in response to CMV has no appreciable effect on a subsequent KIR−NKG2C−NKG2A+NK cell response to EBV.

EBV-stimulated NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells exhibit similar phenotypes

Surface expression of CD94:NKG2A and other NK cell receptors by NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from donors 2 and 3 (Table S1) was visualized using a 2D representation that provides resolution at the single-cell level. To do this, we constructed a visual stochastic network embedding (viSNE) map (Amir et al., 2013) for each receptor (Fig. 2 B). After a 10-d stimulation with EBV, the dominant subsets of NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells expressed high surface levels of inhibitory CD94:NKG2A and activating NKG2D, DNAM-1, and 2B4. In addition to these receptors, NK cells expressed a high level of the activating receptor NKp30. Almost all the cells were CD2bright and lacked the CD16 and CD57 markers of NK cell maturation (not depicted). Moreover, Siglec-7 expression of Akata-stimulated NK cells was decreased from that of unstimulated NK cells, but they showed no change in KIR expression. Although only ∼20% of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells expressed CD56, more than 90% of NK cells were CD56bright, a characteristic of immature NK cells (Fig. 2 B). Overall, the surface phenotype of these NK cells is remarkably similar to that of NK cells isolated from the peripheral blood of IM patients (Azzi et al., 2014). A key difference is that those cells are CD56dim, a characteristic of mature NK cells. This difference in maturity is consistent with the NK cells in our 10-d cultures in vitro, with EBV having had a much shorter exposure to the virus than the 28–56 d that occurs in vivo before symptoms of IM manifest and diagnosis can be made (Hoagland, 1955).

In conclusion, the similarities between the phenotypes of NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells activated by EBV+ Akata cells raise the possibility that these cell populations make a complementary innate immune response to EBV in donors 2 and 3.

Bimodality and balance of the human Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response to EBV

That donors 2 and 3 made a Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response to Akata cells, whereas donor 1 did not (Fig. 1, A and B), points to a qualitative, bimodal variation in human immunity to EBV. We therefore extended the analysis to a cohort of 24 healthy donors. Thirteen donors (group 1) made vigorous NK cell and Vγ9Vδ2 T cell responses to EBV, whereas 11 donors (group 2) made only the NK cell response (Fig. 3, A–C). The differential Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response of group 1 and 2 donors does not correlate with HLA type (Table S2), CMV status, prior exposure to EBV, or sex. Three group 1 and two group 2 donors are CMV+; 12 group 1 and nine group 2 donors are EBV+; and five group 1 and four group 2 donors are females. No differences were detected in the NK cell responses of group 1 and 2 donors to EBV, and no significant expansion of other invariant T cells, such as Vδ1 T cells, mucosal-associated invariant T cells (MAIT), or iNKT cells, was observed (Fig. S2).

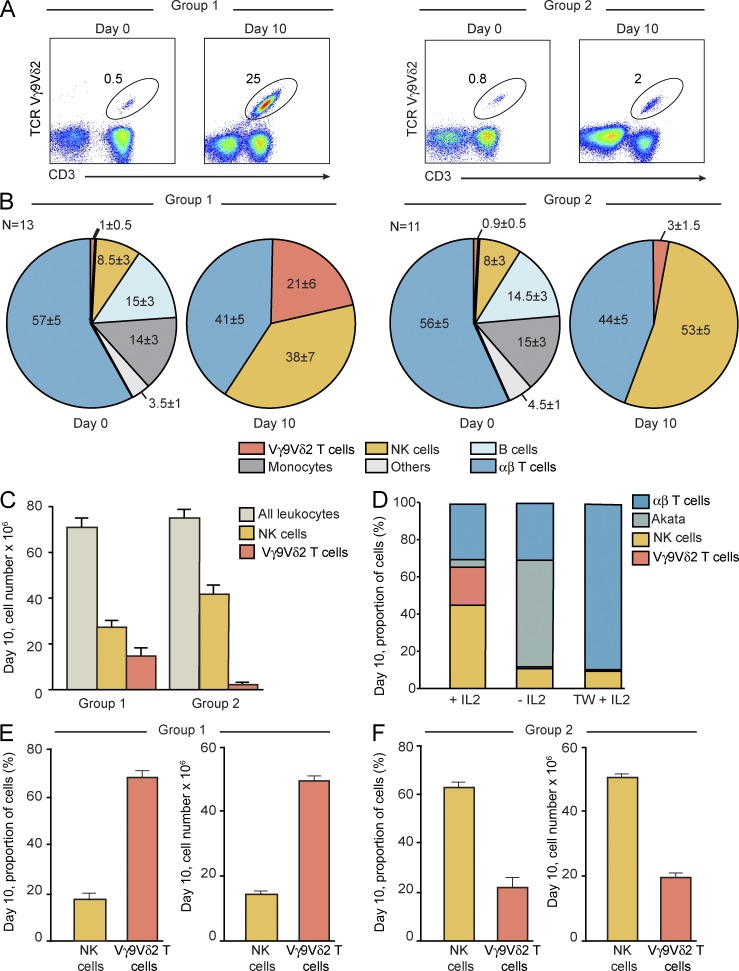

Figure 3.

Bimodality in the human Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response to EBV. (A) 2D plots showing the size of the Vγ9Vδ2 T cell subpopulation in total unstimulated PBMCs and PBMCs after 10 d of culture with Akata cells. Representative data are shown for one group 1 donor (left; n = 13) and one group 2 donor (right; n = 11). (B) Pie charts showing the relative numbers (percentage of total cells) of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, αβ T cells, NK cells, monocytes, B cells, and other cells in unstimulated PBMCs (day 0) and in PBMCs stimulated for 10 d with Akata cells (day 10). Mean values and SDs are given. For day 0 and day 10, the data for the group 1 donors (left; n = 13) and group 2 donors (right; n = 11) were analyzed separately. Statistically significant difference (P < 0.0001) was assessed between group 1 and group 2 Vγ9Vδ2 T cell proportions using ANOVA. (C) Histogram showing the absolute numbers of cells from cultures at day 10 for all leukocytes, NK cells, and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Mean values and SDs are given. The data for the group 1 donors (n = 13) and group 2 donors (n = 11) were analyzed separately. Statistically significant difference (P < 0.0001) was assessed between group 1 and group 2 Vγ9Vδ2 T cell numbers using ANOVA. (D) Histogram showing the proportions of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, αβ T cells, NK cells, and Akata cells after 10-d culture of PBMCs with Akata cells. Three conditions were used: presence of IL2, absence of IL2, and presence of IL2 with separation of PBMCs from Akata targets by a Transwell (TW) system. PBMCs from three group 2 donors were studied. Shown is one representative of three experiments performed. (E and F) Histograms showing the proportions and absolute numbers of NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells after 10-d culture of PBMCs, depleted of CD4 and CD8 T cells, with Akata cells and IL2. Mean values ± SD are given. PBMCs from three group 1 donors (E) and three group 2 donors (F) were studied.

To assess the role of IL2 in the NK cell and Vγ9Vδ2 T cell responses to Akata, PBMCs from group 1 donors were co-cultured in the presence or absence of IL2. In its presence, NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells proliferated, becoming >60% of the total cell number (Fig. 3 D). In the absence of IL2, lymphocyte activation was minimal, and Akata accounted for 60% of the proliferating cells (Fig. 3 D). To determine whether NK cell and Vγ9Vδ2 T cell responses to EBV depend on physical contact between PBMCs and Akata, cultures were made in a Transwell system that prevents such contact but supplies the cells with IL2. Under these conditions, neither NK cells nor Vγ9Vδ2 T cells proliferated (Fig. 3 D). Although the proportion of αβ T cells in these cultures increased, their absolute number did not (not depicted). These results demonstrate how both IL2 and physical contact between lymphocytes and EBV-infected target cells are necessary to initiate the activation of NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and their proliferation in response to EBV.

We also examined whether autologous CD4 and CD8 T cells are necessary for the activation of NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. To do this, PBMCs from group 1 and group 2 donors were depleted of CD4 and CD8 T cells and then co-cultured with Akata cells. The response of group 1 donors was dominated by Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, which accounted for ∼70% of the cells and exceeded 50 million in number. NK cells accounted for ∼20% of the day 10 cells in the cultures (Fig. 3 E). In contrast, the response of group 2 donors was dominated by NK cells, accounting for >45 million cells and >60% of the total cell number. Vγ9Vδ2 T cells accounted for ∼25% of the day 10 cells in the cultures of group 2 (Fig. 3 F). These results show that CD4 and CD8 T cells are not physically required for the NK cell and Vγ9Vδ2 T cell responses to EBV. This suggests that some EBV-induced antigens on the EBV-infected Akata cells are being directly recognized by the NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells.

Our results demonstrate how healthy humans divide into two groups whose Vγ9Vδ2 T cells respond in different ways to EBV. Group 1 makes a strong Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response to EBV, whereas group 2 makes a weak Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response. A striking result is that the study cohort comprises almost equal numbers of group 1 and group 2 donors. This even balance suggests there has been a selective advantage to maintaining both functional phenotypes in human populations.

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 1 donors proliferate in response to type I EBV infection

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells have been shown to respond to Daudi, an EBV+ BL cell line (Sturm et al., 1990). Because Daudi, like Akata, maintains a latency I type of EBV infection, we hypothesized that Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 1 donors would respond to this particular form of EBV latency. To test this possibility, we stimulated PBMCs from group 1 and group 2 donors with four different types of EBV-infected B cell lines: type I BL cell lines (Daudi, Akata, and Kem-I); the Wp-restricted BL cell line Sal that expresses only EBNA1, 3A, 3B, 3C, and a truncated form of EBNA-LP; type III BL cell lines (Raji and Jijoye), which express all latent EBV proteins; and a lymphoblastoid B cell line (LCL; type III). The EBV− erythroleukemic cell line K562 provided the negative control. As predicted, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 1 donors proliferated strongly in response to Daudi, Akata, and Kem-I (P < 0.0001). Group 1 Vγ9Vδ2 T cells also proliferated in response to Sal (P < 0.008) but did not respond to Raji, Jijoye, LCL, or K562 (Fig. 4 A). These results show that group 1 Vγ9Vδ2 T cells respond strongly to type I EBV latency and also to Wp-restricted EBV latency, but to a lesser extent.

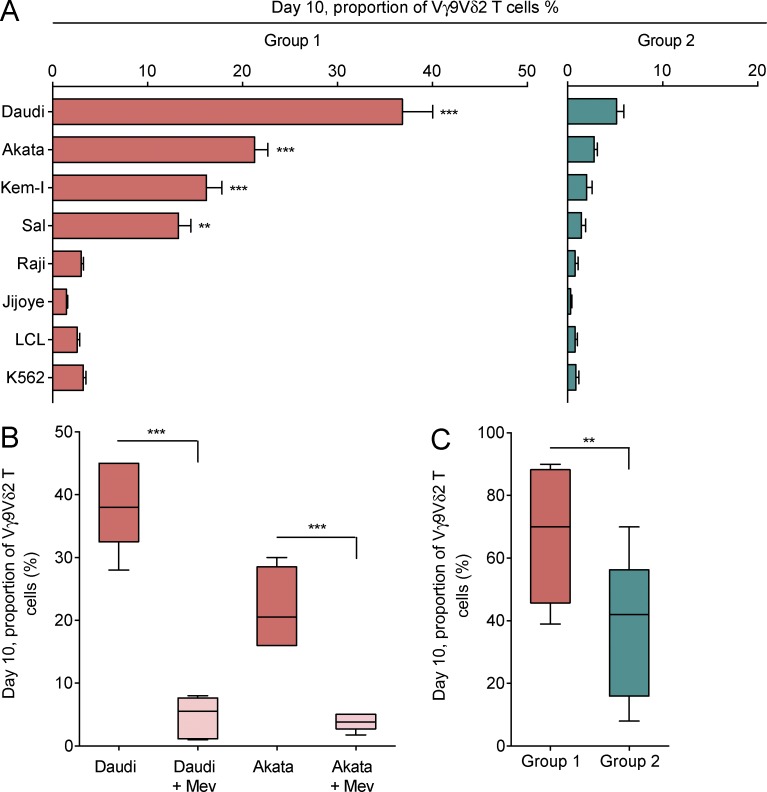

Figure 4.

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 1 donors proliferate in response to type I EBV infection. (A) PBMCs from six group 1 donors (orange) and six group 2 donors (green) were stimulated in culture for 10 d with IL2 and target cells. The targets were type I BL cell lines (Daudi, Akata, and Kem-I), the Wp-restricted BL cell line Sal, type III BL cell lines (Raji and Jijoye), and type III EBV-infected LCL and K562. Bar graphs give the proportion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells after the 10-d culture. Mean values ± SEM are also given. Statistically significant difference between each experimental target cell and the negative control, K562 cells, was assessed using ANOVA (**, P < 0.008; ***, P < 0.0001). (B) PBMCs from six group 1 donors were stimulated in culture for 10 d with IL2 and target cells. The targets were Daudi and Akata, either preincubated (light pink) or not preincubated (orange) for 24 h with 80 µM mevastatin (Mev). Boxes and whiskers represent the proportion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells after the 10-d culture. Statistical significance in the difference between experiment and control was assessed using ANOVA (***, P < 0.0001). (C) Boxes and whiskers represent the proportion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells after 10-d culture of PBMCs from eight group 1 donors (orange) and eight group 2 donors (green), in the presence of 100 µM IPP and IL2. Statistical significance in the difference between the two groups was assessed using the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (**, P < 0.01).

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells respond to pyrophosphate-containing compounds, collectively called phosphoantigens (pAgs; Chien et al., 2014). This raises the possibility that type I BL cells maintain high concentrations of endogenous pAgs, metabolites of the mevalonate pathway, and that these stimulate the Vγ9Vδ2 T cells of group 1 donors. To test this hypothesis, we stimulated PBMCs from group 1 donors with Akata and Daudi cells that were either preincubated or not with mevastatin, an inhibitor of the mevalonate pathway. Consistent with our hypothesis, Daudi and Akata cells preincubated with mevastatin failed to stimulate Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (Fig. 4 B).

We also examined whether the Vγ9Vδ2 T cells of group 2 donors are exhausted. To do this, we stimulated PBMCs from group 1 and group 2 donors with high concentrations of exogenous isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP). Although the Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 2 donors made a less effective response than those from group 1 donors (P < 0.01), their number had risen by ∼180-fold after 10 d in culture, accounting for a mean frequency of 38% of all the cells in the culture (Fig. 4 C). This clearly shows that group 2 Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are not exhausted or anergic.

Our results demonstrate that group 1 Vγ9Vδ2 T cells recognize and proliferate in response to type I EBV infection, which is characterized by high concentrations of endogenous pAgs in the infected cells. Moreover, we show that group 2 Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are not anergic and can respond to a strong stimulation with exogenous pAgs, although significantly less well than the Vγ9Vδ2 T cells of group 1 donors.

Activation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells by type I EBV infection involves CD277 and NKG2D

In responding to EBV, the Akata-activated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and NK cells increase their expression of a battery of activating receptors (Fig. 2 B). To assess the functional contribution of these various receptors, we examined the effect of specific antagonistic mAbs on Akata-mediated activation. Also examined was the effect of antibody specific for CD277 (also called BTN3A1), a member of the butyrophilin family and essential for pAg-mediated activation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (Harly et al., 2012; Vavassori et al., 2013; Sandstrom et al., 2014). CD277 is expressed by both effector and target cells, but its expression by either NK cells or Vγ9Vδ2 T cells was not significantly altered upon exposure to type I EBV infection. Aliquots of PBMCs from group 1 donors were treated with antagonistic mAbs specific for five activating receptors and CD277 or with control mouse IgG and then cultured with Akata for 10 d. To also assess the effect of CD277 on target cells, we preincubated Akata target cells with anti-CD277 or with control mouse IgG and then cultured them for 10 d with PBMCs.

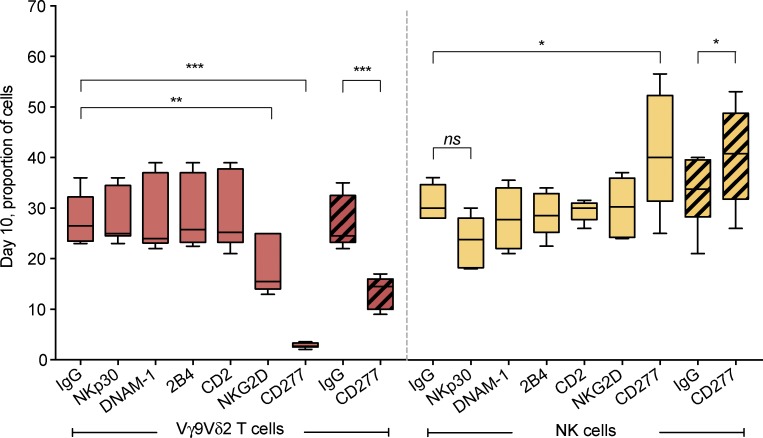

Control IgG and antagonistic antibodies specific for NKp30, DNAM-1, 2B4, and CD2 had no effect on Akata-mediated activation and proliferation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. In contrast, anti-NKG2D significantly reduced the Akata-mediated proliferation (P = 0.003), which was completely abrogated by anti-CD277 (P < 0.0001). Vγ9Vδ2 T cell proliferation was also significantly reduced when Akata were preincubated with anti-CD277 (P < 0.0001). These results demonstrate the importance of the activation of NKG2D on Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and CD277 on both Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and Akata (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

A role for CD277 and NKG2D in the activation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells by type I EBV infection. PBMCs from eight group 1 donors were preincubated with antagonistic mAbs against NKp30, DNAM-1, 2B4, CD2, NKG2D, CD277, or a control mouse IgG. They were then stimulated with Akata for 10 d in the presence of IL2. In other cultures, PBMCs alone were stimulated for 10 d with Akata cells preincubated with anti-CD277 or IgG control. Boxes and whiskers represent the proportion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (orange) and NK cells (yellow) after the 10-d culture with Akata cells. Hatched boxes and whiskers represent the proportion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (orange) and NK cells (yellow) after the 10-d culture with Akata cells preincubated with anti-CD277 or IgG control. Statistical significance of the difference between experiment and control was assessed using ANOVA (*, P = 0.01; **, P < 0.003; ***, P < 0.0001; ns, nonsignificant).

Whereas anti-CD277 effectively blocked Vγ9Vδ2 T cell activation, this antibody increased the proportion of NK cells. The effect was observed if either Akata or PBMCs were preincubated with anti-CD277 (P = 0.01). As no significant increase in the absolute number of NK cells was observed, this result could be a direct consequence of the decrease in the relative number of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in the cell cultures. Among the antagonistic mAbs against activating receptors, anti-NKp30 caused a slight inhibition of the NK cell response (P = 0.08), but mAbs specific for DNAM-1, 2B4, CD2, and NKG2D had no effect (Fig. 5).

In summary, our results demonstrate an essential role for CD277 and an important contribution from NKG2D in the Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response to type I EBV infection. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing a critical costimulatory role for CD277 (Harly et al., 2012; Vavassori et al., 2013; Sandstrom et al., 2014) and NKG2D (Das et al., 2001; Nedellec et al., 2010) in Vγ9Vδ2 T cell activation by pAgs.

Group 1 Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are functionally more potent in their response to type I EBV infection than group 2 Vγ9Vδ2 T cells

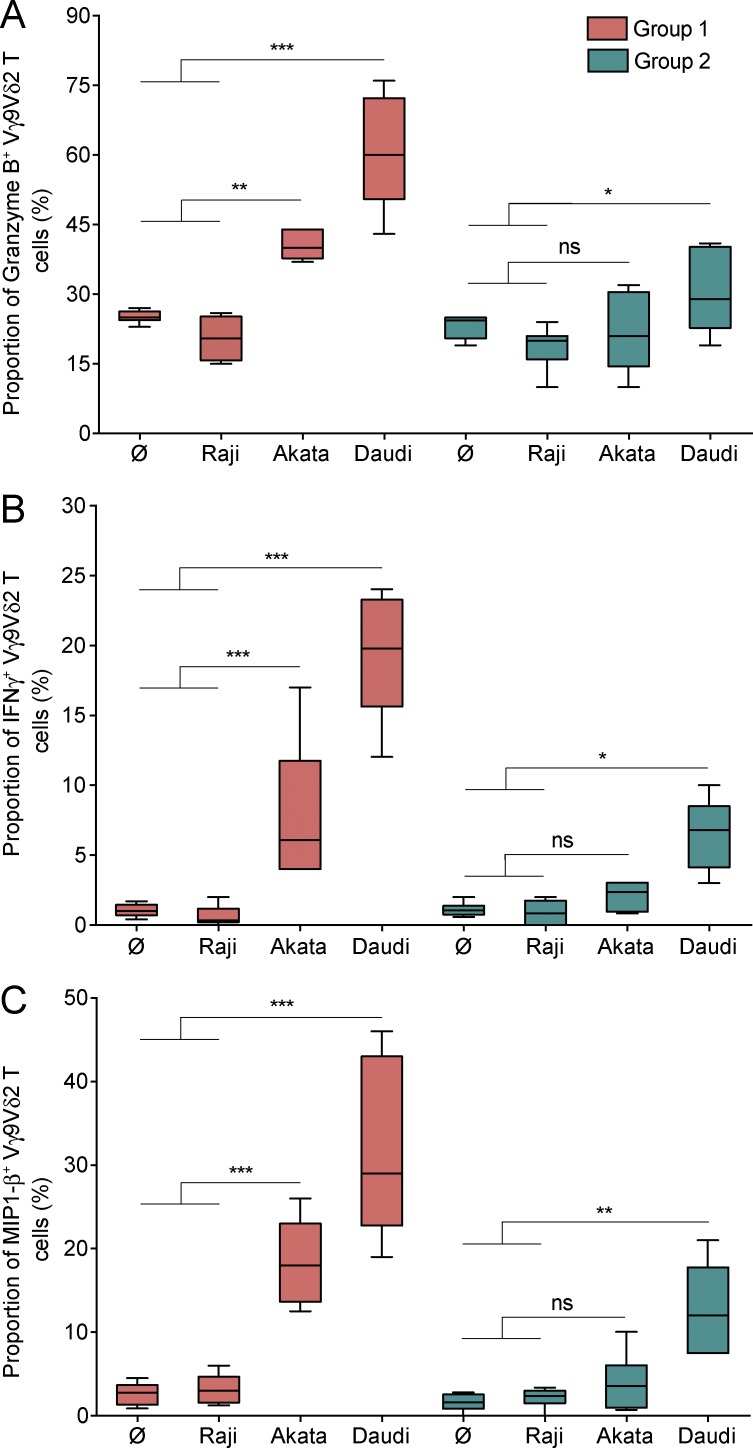

We investigated whether Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 1 donors make stronger functional responses to type I EBV infection than Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 2 donors, as well as exhibiting more extensive proliferation. To do this, we stimulated PBMCs from group 1 and group 2 donors with Akata and Daudi cells in a 24-h culture. As negative controls, PBMCs were also cultured alone or with type III EBV-infected Raji cells. Cytotoxic activity of the Vγ9Vδ2 T cells was assessed by flow cytometry to measure the intracellular production of granzyme B (Fig. 6 A). With this approach, we similarly evaluated the capacity of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells to produce a major cytokine, IFNγ (Fig. 6 B), and a major chemokine, MIP1-β (Fig. 6 C), of γδ T cells.

Figure 6.

Group 1 Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are functionally more potent in their response to type I EBV infection than group 2 Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. PBMCs from six group 1 donors and six group 2 donors were incubated in culture either alone (Ø) or in the presence of target cells. The targets were Raji (a negative control), Akata, and Daudi. (A) Boxes and whiskers represent the proportion of granzyme B+ Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 1 donors (orange) and group 2 donors (green) after 24-h culture. (B) Boxes and whiskers represent the proportion of IFNγ+ Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 1 donors (orange) and group 2 donors (green) after 24-h culture. (C) Boxes and whiskers represent the proportion of MIP1-β+ Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 1 donors (orange) and group 2 donors (green) after 24-h culture. Statistical significance of the difference between experiment and control was assessed using ANOVA (*, P ≤ 0.04; **, P < 0.004; ***, P ≤ 0.0006; ns, nonsignificant).

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 1 donors made stronger responses to Akata and Daudi than Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 2 donors, as assessed by granzyme B production (P < 0.004 for Akata and P < 0.0001 for Daudi; Fig. 6 A). Similar differences between group 1 and group 2 donors were observed for IFNγ production (P < 0.0006 for Akata and P < 0.0001 for Daudi; Fig. 6 B) as well as for MIP1-β production (P < 0.0001 for both Akata and Daudi; Fig. 6 C). The results from these three functional assays demonstrate that Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 1 donors exhibit a more effective immune response to type I EBV infection than the Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 2 donors (Fig. 6). In conclusion, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 1 donors have greater capacity for both proliferation and effector response than the corresponding cells from group 2 donors.

Bimodality in the human Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response to EBV in vivo

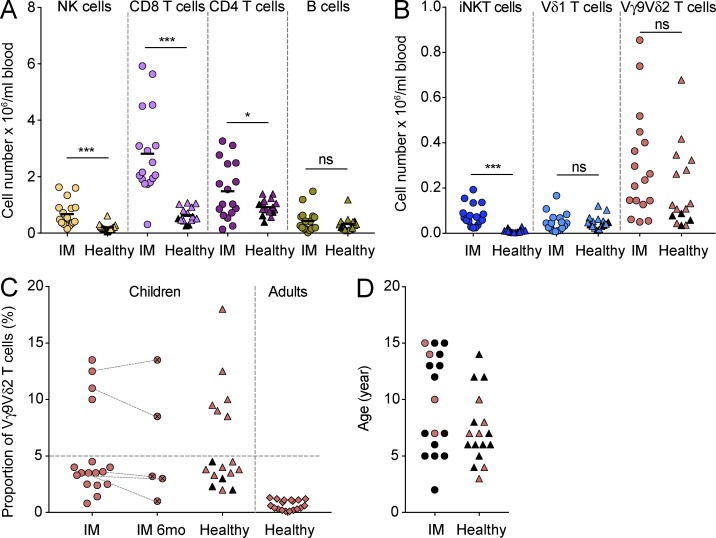

During acute IM, infected memory B cells accumulate in the blood and exhibit a phenotype similar to BL with type I EBV infection (Hochberg et al., 2004). We therefore investigated whether the dichotomous Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response to EBV observed in vitro also occurs in vivo. We assessed frequencies and total cell numbers of NK cells, CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, B cells, iNKT cells, Vδ1 T cells, and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in the peripheral blood of 17 healthy children and 17 children experiencing acute IM. Consistent with previous observations (Williams et al., 2005; Hislop et al., 2007; Azzi et al., 2014), we found that the blood of children with acute IM had high numbers of NK cells (P = 0.0005) and CD8 T cells (P < 0.0001). To lesser extent, the CD4 T cell numbers were also increased in the IM patients (P = 0.04). No significant changes in B cell number were observed in children with acute IM (Fig. 7 A). Overall, iNKT cell numbers were increased in children with IM (P < 0.0001), but there were no differences between patients and controls in the numbers of γδ T cells bearing Vδ1 TCR chains (Fig. 7 B). In contrast, high numbers of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, exceeding 5% of total lymphocytes, were seen in four IM patients and six healthy EBV+ controls. The absolute numbers of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were similarly increased in these individuals (Fig. 7, B and C). Furthermore, there was no correlation between the proportions of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and NK cells in children with acute IM. It is important to note that IM patients have higher numbers of PBMCs than controls because of their acute infection and the inflammation it causes. Consequently, the number of IM patients having a high absolute number of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells is even greater than that of the four bona fide group 1 patients (Fig. 7 B).

Figure 7.

Bimodality in the human Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response to EBV in vivo. (A) Scatter plots represent the absolute numbers of NK cells (yellow), CD8 T cells (light violet), CD4 T cells (dark violet), and B cells (green) in peripheral blood of children experiencing acute IM (circles) and healthy children (triangles). EBV− healthy children are indicated by black triangles. Mean values are given. Statistical significance in the difference between IM and healthy children was assessed using the unpaired Student’s t test (*, P = 0.04; ***, P ≤ 0.0005; ns, nonsignificant). (B) Scatter plots represent the absolute numbers of iNKT cells (dark blue), Vδ1 T cells (light blue), and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (orange) in peripheral blood of children experiencing acute IM (circles) and healthy children (triangles). EBV− healthy children are indicated by black triangles. Statistical significance in the difference between IM and healthy children was assessed using the unpaired Student’s t test (***, P < 0.0001; ns, nonsignificant). (C) Scatter plots represent the proportion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in peripheral blood of children experiencing acute IM (circles), children at 6 mo after the diagnosis of IM (crossed circles), healthy children (triangles), and healthy adults (diamonds). EBV− healthy children are indicated by black triangles. (D) Scatter plots represent the age of children experiencing acute IM (circles) and healthy children (triangles). Children who exhibited high proportions of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are indicated in orange.

We found that the cohorts of healthy EBV+ children and acute IM patients both include group 1 individuals with high number and proportion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and group 2 individuals with low number and proportion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. The cohort of healthy EBV+ children included a larger number of group 1 individuals (46%; n = 6) than the cohort of acute IM patients (23.5%; n = 4). The EBV+ healthy children, all 10 years old or younger (Fig. 7 D), were likely to have been infected with EBV without subsequent development of IM. Consistent with this interpretation, the group 1 IM patients followed longitudinally maintained high frequencies of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells 6 mo after diagnosis of acute IM and clearance of EBV-related symptoms (Fig. 7 C). Moreover, such high Vγ9Vδ2 T cell frequencies were not observed among EBV+ healthy adults who fully controlled EBV and for whom Vγ9Vδ2 T cells never exceeded 5% of total lymphocytes (Fig. 7 C).

Discussion

In making an innate immune response to EBV, human individuals form two distinctive groups that differ according to the types of lymphocytes recruited to the response. Group 1 individuals make both an NK cell and a Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response. In contrast, group 2 individuals make only an NK cell response, but it is a stronger one than that made by group 1 individuals. Of the 24 blood donors we studied, 13 are in group 1 and 11 are in group 2, indicating that the human population divides evenly into these two groups. In the context of the human immune response to EBV, there is bimodality in the Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response, in which around half the population is responsive and the other half is not. At the level of the species and its constituent populations, the balance of these two functional phenotypes argues for both of them having functional benefit and selective advantage.

The qualitative difference in the γδ T cell response of group 1 and group 2 individuals does not correlate with sex. Neither is it caused by a deficiency of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in the group 2 donors, because in all individuals Vγ9Vδ2 T cells represent ∼0.5–1.5% of the PBMCs. Nor does the difference correlate with prior exposure to EBV, because a large majority of the donors we studied (21 of 24) were EBV infected. Thus, some other mechanism must underlie this intriguing difference in the innate immune response to EBV. To our knowledge, no differential human γδ T cell immune response to EBV, or any other infection or cancer, has been previously described.

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, which represent only 1–4% of peripheral blood T cells in healthy adults, are increased in number in patients infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other pathogens. This proliferation occurs when the Vγ9Vδ2 T cells recognize microbial pAgs (Chen, 2013). Here, we show that Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from group 1 donors are strongly activated by type I EBV infection, which is characterized by high concentrations of endogenous pAgs in the infected cells. That the Daudi cell line elicits a more vigorous stimulation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells than other type I BL cell lines is probably a result of its lack of β2-microglobulin, which causes complete down-regulation of cell-surface HLA class I (Nilsson et al., 1974). Consequently, the Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, which lack inhibitory KIR but express high surface levels of CD94:NKG2A, are not inhibited through the interaction of this inhibitory receptor with its HLA-E ligand. We also demonstrate that group 2 Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are not anergic. They do respond to a strong stimulation with exogenous pAgs, although to lesser extent than the Vγ9Vδ2 T cells of group 1 donors.

Consistent with these in vitro data is our study and comparison of cohorts of healthy EBV+ children and pediatric IM patients. Both cohorts included a balance of group 1 individuals with high numbers of peripheral blood Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, and group 2 individuals, with low numbers. Given their very young age, the group 1 EBV+ healthy children are likely to carry an asymptomatic EBV infection. Although the size of these cohorts is small, that the cohort of EBV+ healthy children included a larger number of group 1 individuals suggests that Vγ9Vδ2 T cells play a beneficial role in the innate immune response to EBV.

In a previous study, Vγ9Vδ2 T cell clones cultured from the PBMCs of a kidney transplant recipient all made a robust response to Daudi cells. In contrast, only a few of the Vγ9Vδ2 T clones cultured from human fetal tissue responded to Daudi. To explain this difference, the authors proposed a mechanism of γδ T cell selection by pAgs, which acts after birth in peripheral tissues to increase the representation of Daudi-reactive Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (Davodeau et al., 1993). In the context of this model, group 2 donors could have fewer Vγ9Vδ2 TCRs that recognize the pAgs presented by type I EBV-infected B cells. Consequently, characterization of the structure and diversity of the γδ TCRs of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells stimulated by type I EBV infection could be an important next step toward understanding why approximately half the human population cannot make a Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response. We find that CD277 and NKG2D play essential roles in the Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response to type I EBV infection, suggesting that polymorphism in the CD277 and NKG2D genes could be genetic factors that contribute to the differential response to EBV of group 1 and group 2 donors. Further investigation will be needed to determine the contributions made by CD277 on target cells and effector cells in the Vγ9Vδ2 T cell response to type I EBV infection.

That NK cells have a beneficial role in the human innate immune response to EBV infection is a concept now generally accepted (Williams et al., 2005; Pappworth et al., 2007; Chijioke et al., 2013; Azzi et al., 2014). In previous investigations, NK cells were seen to be more effective killers of B cells with lytic EBV infection than B cells with latent EBV infection (Pappworth et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2016). In contrast, we find that Akata cells with lytic infection induce less NK cell proliferation than Akata cells with latent infection. During early phases of lytic infection, Akata both down-regulates HLA class I expression and up-regulates expression of the ligands for activating NK cell receptors. This intriguing difference between effector function and proliferation could be caused by a hierarchy of signaling pathways, which allows cytolysis to be induced in the absence of NK-cell division. Consistent with this mechanism, our experiments to stimulate PBMCs with HLA-deficient K562 cells, an iconic NK cell target, induced a low proliferation of NK cells (unpublished data).

NK cells responding to Akata increase their surface expression of activating receptors and exhibit the characteristic CD56brightCD94:NKG2AhighKIR− phenotype of early NK cell differentiation. These results complement and extend previous studies of an increased number of immature NK cells in the blood of IM patients (Williams et al., 2005; Azzi et al., 2014). The phenotype of the Akata-stimulated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells is remarkably similar to that of the Akata-stimulated NK cells. This suggests that both NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells recognize EBV-induced costimulatory ligands, possibly activating NK cell receptor and γδ T cell receptor ligands, which drive their selection and proliferation.

Unexpectedly, our study uncovered a phenotypic dimorphism in the human innate immune response to EBV. Approximately one-half of the population responds to EBV with NK cells and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, whereas the other half responds with NK cells alone. Increasing evidence points to the contribution of γδ T cells to innate immunity against viral infection. In vitro pAg-stimulated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells can prevent EBV-induced malignancy in humanized mice (Xiang et al., 2014). After birth, age-related increases in the number and frequency of human peripheral blood Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (Parker et al., 1990) might explain why primary EBV infection in very early childhood is usually asymptomatic. The striking difference we see in the human innate immune response to EBV in vitro could explain both the clinical course and outcome of primary EBV infections, as well as the susceptibility of immunocompromised individuals to EBV-induced malignancy. Because Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are known to respond to other herpesviruses, notably herpes simplex virus (Bukowski et al., 1994) and CMV (Daguzan et al., 2016), a crucial and intriguing question is whether the bimodality of the human innate immune response is specific to EBV or pertains to other herpesviruses.

Materials and methods

Cells and cell culture

Blood samples were collected from healthy adult volunteer donors and purchased as anonymized LRS chambers from the Stanford Blood Center. PBMCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque PLUS; GE Healthcare) as recommended by the manufacturer and cryopreserved in FBS (Gemini) supplemented with 10% DMSO (EMD Millipore).

Samples from 17 pediatric patients diagnosed with acute IM and 17 healthy children undergoing elective tonsillectomy at the University Children’s Hospital of Zurich were collected as described (Azzi et al., 2014). All participants provided informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the institutional ethics committee approved all protocols used (KEK-ZH Nr. St 40/05).

Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed, suspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Corning Cellgro), and centrifuged for 5 min at 1,500 rpm. Cell pellets were resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS and kept at 37°C overnight. This period of culture allowed the PBMCs to recover from the freeze-thaw before subjecting them to in vitro experimentation.

The EBV+ and EBV− Akata cell lines were provided by J. Sample (Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA). EBV+ Akata maintains a type I EBV infection and can be induced to enter the EBV lytic cycle by cross-linking of its BCR. Akata (Takada et al., 1991), Daudi (Klein et al., 1968), and Kem-I (Gregory et al., 1990) are type I BL cell lines. Sal is a Wp-restricted BL cell line (Kelly et al., 2002). Kem-I and Sal were provided by S. Kenney (University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI). LCLs were generated by infecting freshly isolated PBMCs with the B95.8 strain of EBV as described (Neitzel, 1986). Raji (Pulvertaft, 1964) and Jijoye (Kohn et al., 1967) are type III BL cell lines, which were purchased from ATCC. K562 is an EBV− HLA class I–deficient erythroleukemia cell line. All cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing heat-inactivated FBS (10%), l-glutamine (5 mM), and streptomycin/penicillin (100 IU/100 µg/ml; Thermo Fisher Scientific). All cell lines were confirmed to be EBV− or EBV+, using a PCR-based assay that tests for the presence of DNA encoding EBNA1 (Yap et al., 2007). All cell cultures were performed at 37°C, unless stated otherwise.

Induction of the EBV lytic cycle in Akata cells

Akata cells (107) were incubated with polyclonal goat anti–human F(ab) IgG (1%; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 3 h at 37°C. To remove unbound antibody, the cells were diluted in RPMI 1640, centrifuged for 5 min at 1,500 rpm, and subsequently resuspended at 106 cells/ml in fresh RPMI 1640 containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS.

Assay of cellular proliferation in response to EBV

Five million PBMCs were cultured with target cells at an effector-to-target cell ratio of 10:1, in a 24-well plate. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing heat-inactivated FBS (5%), heat-inactivated human AB serum (5%; Sigma Aldrich), l-glutamine (2 mM), streptomycin/penicillin (100 IU/100 µg/ml), and recombinant human IL2 (200 IU/ml). The IL2 was obtained from M. Gately (Hoffmann-La Roche) through the AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. Cells were passaged upon reaching confluence and were supplemented with fresh medium every 2 d for a period of 10 d. Transwell experiments, which investigated the need for direct contact between effector cells and target cells, were performed in 24-well plates. The Akata target cells were placed in Transwell inserts (0.4 µM; Corning) and PBMCs, the source of effector cells, were cultured in the wells beneath the inserts.

In some experiments, Akata and Daudi cells were preincubated for 24 h with 80 µM mevastatin (Sigma-Aldrich). For stimulations with 100 µM exogenous IPP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), 200,000 PBMCs per well were cultured in 96-well plates and passaged upon reaching confluence. In blocking experiments, PBMCs were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with a control IgG or a blocking mAb at a concentration of 10 µg/ml, before the addition of target cells. Blocking antibodies were specific for NKp30 (210845; R&D Systems), DNAM-1 (DX11; BD Biosciences), 2B4 (eBioPP35; eBioscience), CD2 (RPA-2.10; BioLegend), NKG2D (149810; R&D Systems), and CD277 (103.2; Compte et al., 2004). In some experiments, anti-CD277 was used to block CD277 on Akata cell targets.

Functional assays

500,000 PBMCs were cultured alone or in the presence of Akata, Daudi, or Raji (negative control) cells at an effector to target cell ratio of 10:1. Cells were cultured for 24 h in a 96-well plate in RPMI 1640 containing heat-inactivated FBS (5%), heat-inactivated human AB serum (5%), l-glutamine (2 mM), streptomycin/penicillin (100 IU/100 µg/ml), and recombinant human IL2 (200 IU/ml). Brefeldin A (BD) was added to the cultures for the last 4 h. Cells were then stained for flow cytometry analysis, which measured the frequency of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells expressing granzyme B+, IFNγ+, and MIP1-β+.

Antibodies and analysis by flow cytometry

Anti-BZLF1 (BZ1), conjugated to AF488 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), was provided by M. Rowe (Young et al., 1991). This antibody was used to assess EBV reactivation after BCR cross-linking.

Cells proliferating after 10 d of culture with EBV+ or EBV− Akata cells and unstimulated control cells were assessed by flow cytometry using the following five mouse mAb conjugates (BioLegend): anti-CD3 (UCHT1-PerCP), anti-CD56 (HCD56-PE), anti-TCRVδ2 (B6-FITC), anti-CD14 (HCD14-PE), and anti-CD20 (2H7-APC). For functional assays, PBMCs were stained using anti-CD3 (UCHT1-PerCP) and anti-TCRVδ2 (B6-FITC). Cells were then fixed and permeabilized using Fixation/Permeabilization Solution kit (BD) as recommended by the manufacturer. Vγ9Vδ2 T cell function was assessed using mAbs specific for granzyme B (GB11-Alexa Fluor 647; BioLegend), IFNγ (Β27−ΠΕ; BioLegend), and MIP1-β (D21-1351-PE; BD). Data were collected with an Accuri C6 instrument (BD) and analyzed using FlowJo software version 10.1.

B cell purification and detection of EBV genomic DNA

B cells were purified from the PBMCs of healthy volunteer donors using the Dynabeads Isolation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as recommended by the manufacturer. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood B cells and cell lines using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (QIAGEN). A region of the EBNA1 gene was amplified by PCR (forward primer: 5′-GGTAGAAGGCCATTTTTCCAC-3′; reverse primer: 5′-CTCCATCGTCAAAGCTGCAC-3′) as described (Yap et al., 2007).

Conjugation of antibodies for use in mass cytometry

A panel of 31 antibodies was used for the analysis of cells by mass cytometry (Table S1). Metal-ion conjugates of these antibodies were prepared using the Maxpar Antibody Labeling kit (Fluidigm) as recommended by the manufacturer. Conjugated antibodies were diluted in a proprietary “PBS Antibody Stabilization solution” (Candor Bioscience GmbH) to concentrations between 0.1 and 0.3 mg/ml and stored at 4°C. Each metal-conjugated antibody was titrated to give optimal staining of PBMCs. Staining was performed on cryopreserved cells that had been thawed, washed and allowed to recover by overnight culture at 37°C.

Mass cytometry: Staining, data collection, and data analysis

Unstimulated PBMCs and cells proliferating after 10 d of culture were stained with a panel of 31 mAbs (Table S1) as described (Newell et al., 2012; Horowitz et al., 2013). Cells were also stained with Cell-ID Intercalator-Ir (Ir191 and Ir193) and Cell-ID Cisplatin (Pt195) to assess DNA content and cell viability. Mass cytometry data were obtained with a CyTOF 2 instrument (Fluidigm) in the Stanford Shared FACS Facility. The data were analyzed using Cytobank software.

Depletion of CD4 and CD8 T cells from PBMCs

Depletion of CD4 and CD8 T cells from PBMCs was achieved by using the Dynabeads Isolation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as recommended by the manufacturer.

HLA genotyping and CMV serology

HLA-A, -B, and -C genotypes for blood donors were determined by PCR-based sequence-specific oligonucleotide probes, using a Luminex 100 instrument (Luminex Corp.). The assays were performed with LABType SSO reagents (One Lambda). HLA-A, -B, and -C genotypes for Akata were determined using next generation sequencing–based methodology, as previously described (Norman et al., 2016). The CMV status of the donors was determined serologically at the Stanford Blood Center.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using Prism software. P-values were calculated using one-way ANOVA or unpaired Student’s t test, as appropriate. P-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows the sequential gating strategy to identify NK and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from unstimulated PBMCs. Fig. S2 shows that Vδ1 T cells, MAIT cells, and iNKT cells do not significantly respond to EBV infection. Table S1 shows a mass cytometry antibody panel. Table S2 shows HLA-A, -B, and -C genotypes of donors 4–24.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Martin Rowe for advice and for providing the BZ1 antibody, Jeffery Sample for advice and for providing the EBV+ and EBV− Akata cells, Erin Adams for advice, Emily Wroblewski and Pierre-Jean Matteï for critical reading of the manuscript, and Brandon Carter and Marty Bigos for maintaining the CyTOF 2 machine.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 AI22039 to P. Parham.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: Z. Djaoud conceived the project and designed the experiments. Z. Djaoud, A. Horowitz, N. Nemat-Gorgani, and P.J. Norman performed the experiments. T. Azzi, D. Nadal, and C. Münz collected and provided the samples from healthy children and IM pediatric patients. D. Olive generated and provided the 103.2 antibody. Z. Djaoud, L.A. Guethlein, C. Münz, and P. Parham interpreted the data. Z. Djaoud and P. Parham wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- BL

- Burkitt lymphoma

- IM

- infectious mononucleosis

- iNKT cell

- invariant NKT cell

- KIR

- killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor

- LCL

- lymphoblastoid B cell line

- MAIT cell

- mucosal-associated invariant T cell

- pAg

- phosphoantigen

References

- Amir A.D., Davis K.L., Tadmor M.D., Simonds E.F., Levine J.H., Bendall S.C., Shenfeld D.K., Krishnaswamy S., Nolan G.P., and Pe’er D.. 2013. viSNE enables visualization of high dimensional single-cell data and reveals phenotypic heterogeneity of leukemia. Nat. Biotechnol. 31:545–552. 10.1038/nbt.2594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzi T., Lünemann A., Murer A., Ueda S., Béziat V., Malmberg K.-J., Staubli G., Gysin C., Berger C., Münz C., et al. 2014. Role for early-differentiated natural killer cells in infectious mononucleosis. Blood. 124:2533–2543. 10.1182/blood-2014-01-553024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béziat V., Dalgard O., Asselah T., Halfon P., Bedossa P., Boudifa A., Hervier B., Theodorou I., Martinot M., Debré P., et al. 2012. CMV drives clonal expansion of NKG2C+ NK cells expressing self-specific KIRs in chronic hepatitis patients. Eur. J. Immunol. 42:447–457. 10.1002/eji.201141826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski J.F., Morita C.T., and Brenner M.B.. 1994. Recognition and destruction of virus-infected cells by human gamma delta CTL. J. Immunol. 153:5133–5140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.W. 2013. Multifunctional immune responses of HMBPP-specific Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in M. tuberculosis and other infections. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 10:58–64. 10.1038/cmi.2012.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien Y.H., Meyer C., and Bonneville M.. 2014. γδ T cells: First line of defense and beyond. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32:121–155. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chijioke O., Müller A., Feederle R., Barros M.H.M., Krieg C., Emmel V., Marcenaro E., Leung C.S., Antsiferova O., Landtwing V., et al. 2013. Human natural killer cells prevent infectious mononucleosis features by targeting lytic Epstein-Barr virus infection. Cell Reports. 5:1489–1498. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.11.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compte E., Pontarotti P., Collette Y., Lopez M., and Olive D.. 2004. Frontline: Characterization of BT3 molecules belonging to the B7 family expressed on immune cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 34:2089–2099. 10.1002/eji.200425227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Countryman J., Jenson H., Seibl R., Wolf H., and Miller G.. 1987. Polymorphic proteins encoded within BZLF1 of defective and standard Epstein-Barr viruses disrupt latency. J. Virol. 61:3672–3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daguzan C., Moulin M., Kulyk-Barbier H., Davrinche C., Peyrottes S., and Champagne E.. 2016. Aminobisphosphonates synergize with human cytomegalovirus to activate the antiviral activity of Vγ9Vδ2 cells. J. Immunol. 196:2219–2229. 10.4049/jimmunol.1501661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das H., Groh V., Kuijl C., Sugita M., Morita C.T., Spies T., and Bukowski J.F.. 2001. MICA engagement by human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells enhances their antigen-dependent effector function. Immunity. 15:83–93. 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00168-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davodeau F., Peyrat M.A., Hallet M.M., Gaschet J., Houde I., Vivien R., Vie H., and Bonneville M.. 1993. Close correlation between Daudi and mycobacterial antigen recognition by human gamma delta T cells and expression of V9JPC1 gamma/V2DJC delta-encoded T cell receptors. J. Immunol. 151:1214–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djaoud Z., David G., Bressollette C., Willem C., Rettman P., Gagne K., Legrand N., Mehlal S., Cesbron A., Imbert-Marcille B.-M., and Retière C.. 2013. Amplified NKG2C+ NK cells in cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection preferentially express killer cell Ig-like receptor 2DL: Functional impact in controlling CMV-infected dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 191:2708–2716. 10.4049/jimmunol.1301138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M.A., Achong B.G., and Barr Y.M.. 1964. Virus particles in cultured lymphoblasts from Burkitt’s lymphoma. Lancet. 283:702–703. 10.1016/S0140-6736(64)91524-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J.H., Horowitz A., Mehrabi M., Wise E.L., Pease J.E., Riley E.M., and Davis D.M.. 2011. A distinct subset of human NK cells expressing HLA-DR expand in response to IL-2 and can aid immune responses to BCG. Eur. J. Immunol. 41:1924–1933. 10.1002/eji.201041180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley B., Cooley S., Verneris M.R., Pitt M., Curtsinger J., Luo X., Lopez-Vergès S., Lanier L.L., Weisdorf D., and Miller J.S.. 2012. Cytomegalovirus reactivation after allogeneic transplantation promotes a lasting increase in educated NKG2C+ natural killer cells with potent function. Blood. 119:2665–2674. 10.1182/blood-2011-10-386995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory C.D., Rowe M., and Rickinson A.B.. 1990. Different Epstein-Barr virus-B cell interactions in phenotypically distinct clones of a Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line. J. Gen. Virol. 71:1481–1495. 10.1099/0022-1317-71-7-1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harly C., Guillaume Y., Nedellec S., Peigné C.-M., Mönkkönen H., Mönkkönen J., Li J., Kuball J., Adams E.J., Netzer S., et al. 2012. Key implication of CD277/butyrophilin-3 (BTN3A) in cellular stress sensing by a major human γδ T-cell subset. Blood. 120:2269–2279. 10.1182/blood-2012-05-430470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton O., Strauss-Albee D.M., Zhao N.Q., Haggadone M.D., Pelpola J.S., Krams S.M., Martinez O.M., and Blish C.A.. 2016. NKG2A-expressing natural killer cells dominate the response to autologous lymphoblastoid cells infected with Epstein-Barr virus. Front. Immunol. 7:607 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hislop A.D., Taylor G.S., Sauce D., and Rickinson A.B.. 2007. Cellular responses to viral infection in humans: Lessons from Epstein-Barr virus. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25:587–617. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland R.J. 1955. The transmission of infectious mononucleosis. Am. J. Med. Sci. 229:262–272. 10.1097/00000441-195503000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg D., Middeldorp J.M., Catalina M., Sullivan J.L., Luzuriaga K., and Thorley-Lawson D.A.. 2004. Demonstration of the Burkitt’s lymphoma Epstein-Barr virus phenotype in dividing latently infected memory cells in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:239–244. 10.1073/pnas.2237267100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A., Strauss-Albee D.M., Leipold M., Kubo J., Nemat-Gorgani N., Dogan O.C., Dekker C.L., Mackey S., Maecker H., Swan G.E., et al. 2013. Genetic and environmental determinants of human NK cell diversity revealed by mass cytometry. Sci. Transl. Med. 5:208ra145 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating S., Prince S., Jones M., and Rowe M.. 2002. The lytic cycle of Epstein-Barr virus is associated with decreased expression of cell surface major histocompatibility complex class I and class II molecules. J. Virol. 76:8179–8188. 10.1128/JVI.76.16.8179-8188.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly G., Bell A., and Rickinson A.. 2002. Epstein-Barr virus-associated Burkitt lymphomagenesis selects for downregulation of the nuclear antigen EBNA2. Nat. Med. 8:1098–1104. 10.1038/nm758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein E., Klein G., Nadkarni J.S., Nadkarni J.J., Wigzell H., and Clifford P.. 1968. Surface IgM-kappa specificity on a Burkitt lymphoma cell in vivo and in derived culture lines. Cancer Res. 28:1300–1310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn G., Mellman W.J., Moorhead P.S., Loftus J., and Henle G.. 1967. Involvement of C group chromosomes in five Burkitt lymphoma cell lines. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 38:209–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.-Y., Chaigne-Delalande B., Su H., Uzel G., Matthews H., and Lenardo M.J.. 2014. XMEN disease: A new primary immunodeficiency affecting Mg2+ regulation of immunity against Epstein-Barr virus. Blood. 123:2148–2152. 10.1182/blood-2013-11-538686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedellec S., Sabourin C., Bonneville M., and Scotet E.. 2010. NKG2D costimulates human Vγ9Vδ2 T cell antitumor cytotoxicity through protein kinase Cθ-dependent modulation of early TCR-induced calcium and transduction signals. J. Immunol. 185:55–63. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neitzel H. 1986. A routine method for the establishment of permanent growing lymphoblastoid cell lines. Hum. Genet. 73:320–326. 10.1007/BF00279094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell E.W., Sigal N., Bendall S.C., Nolan G.P., and Davis M.M.. 2012. Cytometry by time-of-flight shows combinatorial cytokine expression and virus-specific cell niches within a continuum of CD8+ T cell phenotypes. Immunity. 36:142–152. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson K., Evrin P.E., and Welsh K.I.. 1974. Production of beta 2-microglobulin by normal and malignant human cell lines and peripheral lymphocytes. Transplant Rev. 21:53–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman P.J., Hollenbach J.A., Nemat-Gorgani N., Marin W.M., Norberg S.J., Ashouri E., Jayaraman J., Wroblewski E.E., Trowsdale J., Rajalingam R., et al. 2016. Defining KIR and HLA class I genotypes at highest resolution via high-throughput sequencing. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99:375–391. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyoshi M.K., Nagata H., Kimura N., Zhang Y., Demachi A., Hara T., Kanegane H., Matsuo Y., Yamaguchi T., Morio T., et al. 2003. Preferential expansion of Vγ9-JγP/Vδ2-Jδ3 γδ T cells in nasal T-cell lymphoma and chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection. Am. J. Pathol. 162:1629–1638. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64297-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappworth I.Y., Wang E.C., and Rowe M.. 2007. The switch from latent to productive infection in Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells is associated with sensitization to NK cell killing. J. Virol. 81:474–482. 10.1128/JVI.01777-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker C.M., Groh V., Band H., Porcelli S.A., Morita C., Fabbi M., Glass D., Strominger J.L., and Brenner M.B.. 1990. Evidence for extrathymic changes in the T cell receptor gamma/delta repertoire. J. Exp. Med. 171:1597–1612. 10.1084/jem.171.5.1597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulvertaft J.V. 1964. Cytology of Burkitt’s tumour (African lymphoma). Lancet. 283:238–240. 10.1016/S0140-6736(64)92345-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressing M.E., Keating S.E., van Leeuwen D., Koppers-Lalic D., Pappworth I.Y., Wiertz E.J.H.J., and Rowe M.. 2005. Impaired transporter associated with antigen processing-dependent peptide transport during productive EBV infection. J. Immunol. 174:6829–6838. 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado F.J., Lojo J., Fernández-Alonso C.M., Viñuela J., Cordero O.J., and Nogueira M.. 2002. Interleukin-dependent modulation of HLA-DR expression on CD4 and CD8 activated T cells. Immunol. Cell Biol. 80:138–147. 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01055.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom A., Peigné C.-M., Léger A., Crooks J.E., Konczak F., Gesnel M.-C., Breathnach R., Bonneville M., Scotet E., and Adams E.J.. 2014. The intracellular B30.2 domain of butyrophilin 3A1 binds phosphoantigens to mediate activation of human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Immunity. 40:490–500. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayos J., Wu C., Morra M., Wang N., Zhang X., Allen D., van Schaik S., Notarangelo L., Geha R., Roncarolo M.G., et al. 1998. The X-linked lymphoproliferative-disease gene product SAP regulates signals induced through the co-receptor SLAM. Nature. 395:462–469. 10.1038/26683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm E., Braakman E., Fisch P., Vreugdenhil R.J., Sondel P., and Bolhuis R.L.. 1990. Human V gamma 9-V delta 2 T cell receptor-gamma delta lymphocytes show specificity to Daudi Burkitt’s lymphoma cells. J. Immunol. 145:3202–3208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada K., Horinouchi K., Ono Y., Aya T., Osato T., Takahashi M., and Hayasaka S.. 1991. An Epstein-Barr virus-producer line Akata: Establishment of the cell line and analysis of viral DNA. Virus Genes. 5:147–156. 10.1007/BF00571929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Montfrans J.M., Hoepelman A.I.M., Otto S., van Gijn M., van de Corput L., de Weger R.A., Monaco-Shawver L., Banerjee P.P., Sanders E.A.M., Jol-van der Zijde C.M., et al. 2012. CD27 deficiency is associated with combined immunodeficiency and persistent symptomatic EBV viremia. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129:787–793.e6. 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavassori S., Kumar A., Wan G.S., Ramanjaneyulu G.S., Cavallari M., El Daker S., Beddoe T., Theodossis A., Williams N.K., Gostick E., et al. 2013. Butyrophilin 3A1 binds phosphorylated antigens and stimulates human γδ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 14:908–916. 10.1038/ni.2665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vély F., Barlogis V., Vallentin B., Neven B., Piperoglou C., Ebbo M., Perchet T., Petit M., Yessaad N., Touzot F., et al. 2016. Evidence of innate lymphoid cell redundancy in humans. Nat. Immunol. 17:1291–1299. 10.1038/ni.3553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams H., McAulay K., Macsween K.F., Gallacher N.J., Higgins C.D., Harrison N., Swerdlow A.J., and Crawford D.H.. 2005. The immune response to primary EBV infection: A role for natural killer cells. Br. J. Haematol. 129:266–274. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05452.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L.R., Quinn L.L., Rowe M., and Zuo J.. 2016. Induction of the lytic cycle sensitizes Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells to NK cell killing that is counteracted by virus-mediated NK cell evasion mechanisms in the late lytic cycle. J. Virol. 90:947–958. 10.1128/JVI.01932-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Z., Liu Y., Zheng J., Liu M., Lv A., Gao Y., Hu H., Lam K.-T., Chan G.C.-F., Yang Y., et al. 2014. Targeted activation of human Vγ9Vδ2-T cells controls Epstein-Barr virus-induced B cell lymphoproliferative disease. Cancer Cell. 26:565–576. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap Y.-Y., Hassan S., Chan M., Choo P.K., and Ravichandran M.. 2007. Epstein-Barr virus DNA detection in the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 136:986–991. 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L.S., and Rickinson A.B.. 2004. Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 4:757–768. 10.1038/nrc1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L.S., Lau R., Rowe M., Niedobitek G., Packham G., Shanahan F., Rowe D.T., Greenspan D., Greenspan J.S., Rickinson A.B., et al. 1991. Differentiation-associated expression of the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 transactivator protein in oral hairy leukoplakia. J. Virol. 65:2868–2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.