Abstract

Rev1 is a deoxycytidyl transferase associated with DNA translesion synthesis (TLS). In addition to its catalytic domain, Rev1 possesses a so-called BRCA1 C-terminal (BRCT) domain. Here, we describe cells and mice containing a targeted deletion of this domain. Rev1B/B mice are healthy, fertile and display normal somatic hypermutation. Rev1B/B cells display an elevated spontaneous frequency of intragenic deletions at Hprt. In addition, these cells were sensitized to exogenous DNA damages. Ultraviolet-C (UV-C) light induced a delayed progression through late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle and many chromatid aberrations, specifically in a subset of mutant cells, but not enhanced sister chromatid exchanges (SCE). UV-C-induced mutagenesis was reduced and mutations at thymidine–thymidine dimers were absent in Rev1B/B cells, the opposite phenotype of UV-C-exposed cells from XP-V patients, lacking TLS polymerase η. This suggests that the enhanced UV-induced mutagenesis in XP-V patients may depend on error-prone Rev1-dependent TLS. Together, these data indicate a regulatory role of the Rev1 BRCT domain in TLS of a limited spectrum of endogenous and exogenous nucleotide damages during a defined phase of the cell cycle.

INTRODUCTION

Completion of DNA replication prior to mitosis is a critical phase in the cell cycle of eukaryotic cells. Blockage of the replication machinery by unrepaired DNA nucleotide damage, induced by endogenous or exogenous genotoxic agents, could result in the collapse of replication forks that may lead to DNA breaks and cellular lethality, when not properly resolved. To avert a replicational catastrophe, the cells are equipped with pathways that act to continue replication in the presence of persistent DNA damage (1). Whereas recombination-mediated DNA damage avoidance (DA) pathways are associated with an error-free replicational bypass of DNA lesions using the undamaged sister chromatid as a template, error-prone bypass is executed by TLS, which is characterized by the insertion of a nucleotide across the damaged nucleotide, followed by the subsequent resumption of replication. TLS is believed to be the major source of DNA damage-induced point mutations, underlying pathological processes like tumorigenesis but presumably also the physiological process of somatic hypermutation (SHM), a highly mutagenic process required for the somatic evolution of high affinity antibodies, occurring in antigen-stimulated B cells (2).

Most TLS polymerases belong to the conserved Y-family of DNA polymerases, including Escherichia coli polymerases IV and V, as well as the eukaryotic Rev1 protein and DNA polymerases pol η, pol ι, and pol κ (3). DNA polymerases from the Y-family are distributive and are able to replicate a variety of DNA template lesions in vitro, at the expense of a high rate of misincorporations, depending on the type of DNA lesion and the polymerase involved. Orthologs of Rev1 were identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Caenorhabditis elegans, chicken, mouse and man (3,4). In vitro, Rev1 proteins possess a unique template-dependent deoxycytidyl transferase activity opposite structurally diverse nucleotide damages, including abasic sites and uracil residues (5–11). Although in S.cerevisiae, REV1 is essential for the bypass of abasic sites also in vivo, its catalytic domain may be dispensable for this process (12,13), indicating an additional regulatory or structural role for the protein. Although in vivo TLS of UV-induced photoproducts requires REV1 (14), the protein does not incorporate a deoxycytosine opposite dipyrimidine photoproducts in vitro (11) and in vivo (15,16) in further support of such a catalysis-independent role. In agreement with an important regulatory role of the Rev1 protein in TLS also in vertebrates, Rev1-deficient chicken DT40 cells display reduced viability and are sensitive to a wide range of DNA-damaging agents (4). ‘Knock down’ of REV1 mRNA in human cells results in a hypomutable phenotype after UV treatment (17,18).

The presence of an N-terminal BRCT domain discriminates Rev1 from the other members of Y family of DNA polymerases (19). BRCT domains have been identified in several proteins involved in cell cycle regulation, DNA repair and DNA metabolism (20,21). BRCT domains were shown to bind proteins that are phosphorylated by DNA damage-activated protein kinases ATR and ATM, supportive of the involvement of these domains in regulating cellular DNA damage responses (22–24). The hypomutability of a S.cerevisiae mutant, containing an amino acid change in the REV1 BRCT domain, by short-wave UV-C-light, ionizing radiation, and 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4-NQO) supports a regulatory role for the REV1 BRCT domain in the cellular response to exogenous DNA damage in yeast (14,25–27).

To investigate a role for the Rev1 BRCT domain in regulating DNA damage responses in mammalian cells, we have generated mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells and mice with a targeted deletion in the Rev1 BRCT domain. These Rev1B/B ES cells show normal viability and are slightly sensitive to genotoxic agents. Rev1B/B mice were born in a Mendelian ratio, were normally fertile and did not display an obvious phenotype. Spontaneously occurring Hprt mutants in Rev1B/B ES cells contained predominantly gene deletions rather than base pair substitutions. Following exposure to UV-C light, Rev1B/B ES cells showed prolonged late S and G2 phases, induction of multiple chromatid breaks in a small subset of cells and a reduced frequency of Hprt mutants. This was accompanied by a complete loss of induced mutations at thymidine–thymidine (TT) dimer sites, implicating a role of the Rev1 BRCT domain in regulating TLS of photoproducts at these sites. SHM in the mutant mice was normal, indicating that the Rev1 BRCT domain is dispensable for TLS of abasic and uracil residues. Taken together, these results demonstrate a regulatory role for the BRCT domain of mammalian Rev1 in the mutagenic bypass of spontaneous and induced DNA lesions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gene targeting at Rev1

Genomic clones of the mouse Rev1 gene were isolated from a 129/SvEv PAC genomic library (Research Genetics). Gene targeting vectors pBRCT–hygro and pBRCT–puro, aimed at deleting of one or both alleles of the Rev1 BRCT domain were generated by replacing a 3 kb genomic fragment encoding exons 2 and 3 with pPGK–hygromycin, and pPGK–puromycin cassettes, respectively. A pPGK–TK cassette was introduced flanking the short arms of each vector, to enable counter selection with ganciclovir. The resulting Rev1 alleles were called Rev1B (hyg) and Rev1B (pur). Targeting vector pREV1–loxP was generated by introducing a cassette containing pPGK–neo and pPGK–TK, flanked by loxP sites between exons 3 and 4, as well as an additional loxP site 5′ of exon 2 (Figure 1D). This construct aimed at generating an exon 2 and 3-deleted Rev1 allele in the absence of intervening marker sequences (the Rev1L− allele), as well as at reverting the Rev1B (hyg) allele to wild type, resulting in the Rev1L+ allele. Site-specific recombination between loxP sites by introduction of the Cre recombinase, was performed as described (28). Culture, electroporation, selection and counter selection of subline IB10 of the 129/OLA-derived ES cell line E14 was performed according to established procedures.

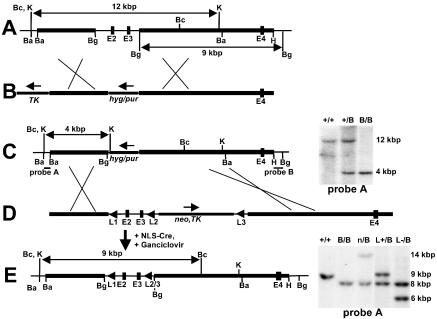

Figure 1.

Targeted mutagenesis at the Rev1 BRCT domain. (A) The 5′ region of the genomic Rev1 locus containing exons 2, 3 and 4 (E2–E4). Horizontal bold sections, genomic regions homologous to the targeting vector. (B) Targeting vectors pBRCT–hygro and pBRCT–puro to delete the Rev1 gene exons 2 and 3 encoding most of the BRCT domain. Hyg, pPGK–hyg cassette. Pur, pPGK–pur cassette. TK, pPGK–thymidine kinase cassette. Arrows, direction of transcription. (C) Targeted Rev1B (hyg or pur) alleles. Probes A and B, DNA fragments used for analysis of gene targeting events. At the right side of the map, a Southern blot of genomic DNA of targeted ES cell lines, digested with KpnI, is depicted. +/+: wild-type ES cells. +/B: Rev1+/B (hyg) cells. B/B: Rev1B/B (hyg, pur) ES cells. (D) pREV1–loxP targeting vector used for constructing the marker-less Rev1L− allele and for restoration of the Rev1B (hyg) allele to wild type. L1: upstream loxP site. Neo, TK: pPGK–neomycin and pPGK–thymidine kinase cassettes, flanked by loxP sites (L2 and L3). (E) Rev1 genomic locus of the Rev1L+/B (pur) ES cell line. At the right side of the map, a Southern blot of genomic DNA of targeted ES cell lines, digested with BclI, is shown. Sizes of fragments representing the different Rev1 alleles are the following: 14 kb: Rev1B (neo/TK), 9 kb wild type, 8 kb Rev1B (pur), and 6 kb Rev1L-. +/+: wild-type ES cells. B/B: Rev1B/B ES cells. n/B: Rev1n/B (neo/TK, pur) ES cells.L+/B: Rev1L+/B (pur) ES cells. L−/B: Rev1L−/B (pur) ES cells. Ba, BamHI; Bc: BclI; Bg, BglII; H, HindIII; K, KpnI.

Identification of targeted recombinants

To analyze ES cell clones electroporated with pBRCT–hygro and pBRCT–puro, Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham Pharmacia) of blotted agarose gels with KpnI-digested DNA were hybridized with a probe externally to the left arm of the targeting vector (probe A, Figure 1C). Membranes with BglII-digested DNA were hybridized with a probe externally to the right arm of the targeting vector (probe B, Figure 1C). Targeting with pRev1–loxP was analyzed as follows: BclI-digested DNA was hybridized with a probe A, BglII-digested DNA with probe B.

Rev1 antibody preparation and immunoblotting

A DNA fragment encoding amino acid residues 772–1249 (the C-terminus) of mouse Rev1 was cloned in pET30 (Novagen) and expressed in E.coli. Rev1-containing inclusion bodies were isolated, washed with 4 M urea and used to immunize rabbits (Eurogentec). The resulting polyclonal antisera were affinity purified using the Rev1 protein fragment, excised from an immunoblot of a preparative polyacrylamide gel (29).

For the immunological detection of Rev1, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (30). Cellular proteins were separated by 6% SDS–PAGE followed by a transfer to PVDF membranes (Millipore). Incubation with affinity-purified Rev1 antibody and subsequent incubation with goat-anti rabbit-peroxidase secondary antibody (BioRad) was followed by an enhanced chemiluminescence detection (ECL+), according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Amersham Biosciences).

RNA isolation and RT–PCR

Total RNA was isolated from ES cells using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Mouse Rev1 cDNA was generated using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with oligonucleotide primer p15 (5′-GCTGGAAGGGCAATTACACT-3′) that anneals at 3034–3015 nt downstream of the putative translational start codon. Primers p17 (5′-AGAACGGAGAATGATGGC-3′) and pGFP2 (5′-GGCCCAGGATCCTCAGGTTTGCACACAGG-3′) were used to amplify a reaction product of 439 bp encompassing 25–464 nt from the translational start codon, containing exons 2–5 (partially). Primers p20 (5′-GTTGCATGGAGGTCAATACC-3′) and pTH2 (5′-AATACTGCCATTCCAG-3′) gave a reaction product of 1176 bp, representing 226–1402 nt downstream of the putative start codon, containing exons 4–8 (partially).

Exposure to genotoxic agents, cell cycle and cytogenetic analysis, clonal survival assays and Hprt mutagenesis

Methylnitrosourea (MNU) treatment: cells were exposed to MNU in medium without fetal calf serum (FCS) at 37°C for 60 min. Cells were washed once with ES culture medium. 4-NQO treatment: cells were exposed to 4-NQO (Sigma-Aldrich) in medium lacking FCS, at 37°C for 60 min. Cells were washed once with ES culture medium. UV-C treatment (Philips T.U.V. lamp, predominantly 254 nm) was performed under a thin layer of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Fresh medium was added after UV-C treatment.

For cell cycle analysis, the cells were seeded at a density of either 1.5 × 106 (untreated control) or 3 × 106 cells (treated cells) per 90 mm gelatin-coated culture dish and grown in a complete medium, containing 50% buffalo rat liver (BRL) cell-conditioned complete medium, 15 h before treatment with UV-C. At various time points after treatment, cells were collected by scraping and subsequently washed twice with cold PBS (4°C) and fixed in 70% cold ethanol. After removal of the fixative, cells were suspended in 500 μl of PBS containing propidium iodide (PI, 33 μg/ml). Cell cycle profiles were generated using a FACSCAN apparatus (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using ModFit LT software (Verity Software House).

For cytogenetic analysis, cells were treated with UV-C as above. After treatment, the cells were cultured in medium supplemented with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; 5 μM) for 24–32 h. Colcemid (0.1 μg/ml) was added to the medium 2 h before the cells were collected and washed in 75 mM KCl at room temperature. Cells were fixed in methanol:acetic acid (3:1). Metaphase spreads were stained according to the FPG technique (31).

Clonal survival and induction of mutations at the Hprt gene were determined as described previously (32).

Mutational spectra analysis of Hprt gene mutations from independently derived mutant clones was performed as described previously (33). Briefly, mouse Hprt cDNA was generated from total RNA of 6-thioguanine-resistant cell clones using the Hprt-specific primer hprt–cDNA (5′-GCAGCAACTGACATTTCTAAAAATAAA-3′). For some experiments, an internal control mouse Aprt cDNA was synthesized using an Aprt-specific primer sus2 (5′-GGGGTGTGACCATCTAGCCAG-3′). After an initial denaturation step of 10 min at 94°C, cDNA was amplified in a PCR reaction of 34 cycles (30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C and 90 s at 72°C) using HotGoldstar Taq polymerase (Eurogentec) and Hprt-specific primers hprt-mus1 and san2m13 (33), as well as Aprt-specific primers sus3 (5′-GTCTTCCCCGACTTCCCAAT-3′) and sus4 (5′-GCCAGGAGGTCATCCACAAT-3′), under conditions described by the manufacturer (Eurogentec). Amplified Hprt cDNA was subjected to automatic DNA sequence analysis (Applied Biosystems).

Generation of Rev1 BRCT-mutant mice and SHM analysis

Two independently derived Rev1+/B ES cell clones were injected into C57Bl/6 blastocysts to generate chimeric male mice that were crossed to C57Bl/6 females. To determine the germ-line transmission of the mutated allele, tail DNA was genotyped in a multiplex PCR reaction using Taq polymerase (Gibco) (35 cycles at 94°C for 60 s, 53°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 90 s), using primers BRCTKA1 (5′-CAATGATAGCCCAACTTGTG-3′) and BRCTKA3 (5′-ACTGAGTCACACTAGCCACG-3′) to identify the wild-type allele and primers BRCTKA1 and PGKJ1 (5′-GCTCATTCCTCCCACTCATG-3′) to identify the mutant allele. F2 heterozygous Rev1B/B mice were interbred to obtain homozygously mutant animals. Somatic hypermutation in memory B cells of non-immunized mice was determined as described previously (34).

RESULTS

Generation and characterization of Rev1 BRCT-mutant ES cells

To study the role of the BRCT domain of mouse Rev1 in mutagenesis and genome maintenance, ES cells containing a targeted deletion of the BRCT domain were generated. Exons encoding this part of the Rev1 protein were mapped (Figure 1A). Gene-targeting vectors pBRCT–hygro and pBRCT–puro (Figure 1B) were constructed to delete exons 2 and 3 from both alleles, coding for the N-terminal 60 amino acids of the protein, including conserved residues (10,21). One Rev1+/B (hyg) clone was used in a second round of gene targeting with pBRCT–puro (Figure 1B). Two resulting Rev1B/B (hyg, pur) ES cell clones, named Rev1B/B-254 and Rev1B/B-243, were used for the experiments described below.

To confirm that the phenotype of Rev1B/B cell lines was not affected by the intervening hygromycin and puromycin cassettes, we have generated an independent ES cell line carrying the biallelic exon 2 and 3 deletion in the absence of a marker gene in one of both Rev1 alleles. This line was called Rev1L−/B. To confirm that the phenotype of Rev1B/B ES cells is caused by the targeted Rev1 deletion, the Rev1B (hyg) allele of Rev1B/B-254 ES cells was reverted to wild type, resulting in Rev1-heterozygous control ES cell line Rev1L+/B (Figure 1D and E). Clones from all gene-targeting experiments were analyzed with external probes A (Figure 1C and E) and B (data not shown).

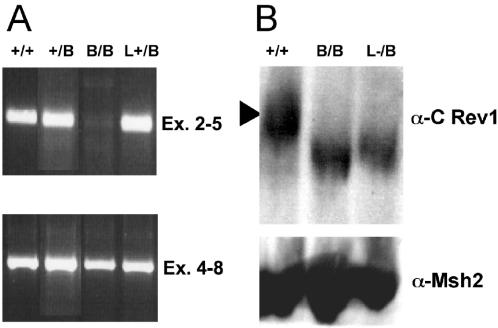

We investigated the expression of Rev1 in the Rev1B/B-254 ES cell line by RT–PCR. The results of this experiment indicated that Rev1B/B ES cells produce Rev1 transcripts only lacking the sequences encoded by exons 2 and 3 that have been deleted from the genome (Figure 2A). Western blot analysis of cell lysates using an antiserum raised against a C-terminal Rev1 fragment showed the presence of Rev1 protein with a slightly reduced molecular mass in the Rev1B/B and Rev1L−/B mutants (Figure 2B). As judged by the similar expression in the Rev1B/B and Rev1L−/B lines, the presence of the intervening marker in the Rev1B/B line did not affect the expression of the truncated protein. A similarly shortened protein was detected in cells transfected with a Rev1 cDNA expression construct carrying a 5′ deletion of 123 bp (including the translational start codon; data not shown). Thus, Rev1B/B ES cells express N-terminally truncated Rev1, most probably initiating within exon 4 at one, or both, of two downstream ATG codons at positions 211 and 214 (position 1 is at the adenine of the putative start codon ATG in exon 2). The protein lacks most of the BRCT domain and has the predicted molecular mass of 129 kDa (versus 137 kDa for the full-length protein).

Figure 2.

Analysis of Rev1 expression in ES cells. (A) PCR products of Rev1 cDNA of exons 2–5 (upper panel) and exons 4–8 (lower panel). (B) Western blot hybridized with an α-Rev1 antiserum (upper panel) or an α-Msh2 antiserum (lower panel). +/+, wild type; +/B, Rev1+/B (hyg); B/B, Rev1B/B (hyg, pur); L+/B, Rev1L+/B (pur); L−/B, Rev1L−/B (pur).

Increased DNA damaging sensitivity and specific defect in cell cycle progression of Rev1 BRCT-mutant ES cells

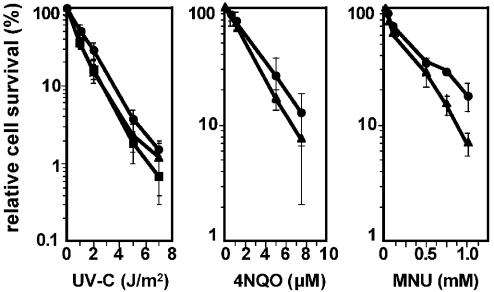

All ES cell lines generated in this study display wild-type growth and cloning efficiency (data not shown). Thus, the Rev1 BRCT domain is dispensable for normal cellular viability or growth. Clonal survival of Rev1B/B and wild-type ES cells was determined following exposure to different types of mutagens: short-wave UV-C light, inducing cyclobutane- and pyrimidine–pyrimidone dimers at adjacent pyrimidines (CPD and 6-4 PP, respectively); 4-NQO, predominantly generating adducts at guanines (35) and MNU, an agent that induces a variety of methylated nucleotides (36). Rev1B/B ES cells display a small but reproducible increased sensitivity to all agents (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Clonal cell survival of ES cells differing in Rev1 mutation. Cells were seeded on gelatin-coated plates and 15 h later exposed to UV-C, 4-NQO or MNU. Then, cell populations were seeded at clonal cell density to determine the clone forming ability. The clone forming ability of unexposed cells was set at 100%. Closed circle, wild type; closed triangle, Rev1B/B-254; closed square, Rev1B/B-243.

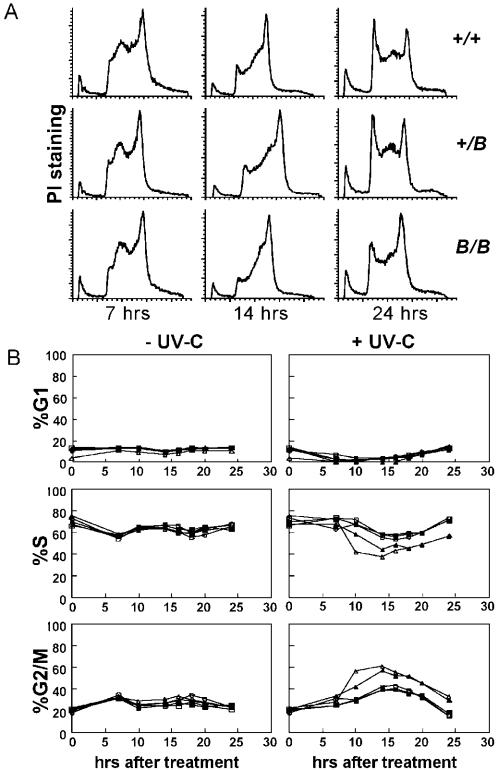

To provide further evidence for a role of the BRCT domain in response to DNA damage, we investigated the progress through the S phase of the cell cycle in UV-C-damaged mutant and wild-type cells. In all untreated ES cell lines, ∼70% of cells were in S phase and ∼15% of the cells were in either G1 or G2 phases; there was no difference in the cell cycle progression between wild-type and mutant cell lines (Figure 4B). Following exposure to 1 J/m2 of UV-C, the Rev1B/B and Rev1L−/B cells displayed a persistent accumulation specifically in late S and in G2 phases, when compared with the wild-type and the heterozygous Rev1+/B and Rev1L+/B lines (Figure 4A and B). Since early- and mid-S phases are unaffected in the mutant, the function of the BRCT domain of Rev1 is probably restricted to the late S phase.

Figure 4.

Cell cycle analysis of different ES cell lines generated in this study. (A) Cell cycle profiles of ES cells fixed 7, 14 and 24 h after exposure to UV-C (1 J/m2). +/+, wild type; +/B, Rev1+/; B/B, Rev1B/B. The x-axis, DNA content; y-axis, number of cells as determined by propidium iodide staining. (B) Modelled frequencies of G1-, S- and G2/M phase cells in unexposed (left panels) and in UV-C-exposed (right panels) cell populations. It is noted that many late S phase cells, visible in panel A, are inadvertently categorized as G2/M cells by the software. Open circle, wild type; closed triangle, Rev1B/B-254; open triangle, Rev1L−/B; open square, Rev1+/B; closed square, Rev1L+/B.

UV-C exposure of Rev1 BRCT-mutant cells induces many chromatid aberrations in a small subset of cells, without concomitant SCE

Arrested replication forks at sites of DNA damage may be rescued either by TLS or by error-free DA, which depends on the annealing of the arrested strand to the sister chromatid that subsequently acts as a template for DNA synthesis. Defects in TLS might result either in the enhancement of this template switching or in collapsed replication forks if template switching is not possible. The latter can result in a double-stranded DNA break (DSB) and consequent chromatid breaks, if the DSB is not properly repaired by homology-mediated DSB repair or by end-joining (37,38). To investigate the involvement of the Rev1 BRCT domain in TLS and a possible redundancy between TLS and DA, we measured the induction of chromatid breaks as well as SCE as an indication of both template switching and homology-mediated DSB repair. The induction of chromatid breaks and aberrations was studied in metaphase spreads of two Rev1B/B lines and wild-type ES cells. After UV-C exposure, nascent DNA was labeled with BrdU, enabling the specific selection of cells that had undergone one complete S phase after treatment for analysis of chromatid aberrations. In mutant cells, the time to complete one cell cycle was significantly extended, as judged by the reduced fraction of cells in the second cycle at 28 h after UV-C treatment (Table 1). This is probably caused by their accumulation at the late S- and G2 phases. To allow the comparison of chromatid aberrations in both genotypes, Rev1B/B cells were analyzed for chromatid aberrations at 32 h after UV-C treatment and wild-type cells at 28 h, at which time point, similar fractions of each cell line had undergone one complete replication cycle. After UV-C treatment, both tested Rev1B/B ES cell lines displayed a moderate (from 25 to 35% of all cells) increase in the number of cells with a low number of chromatid breaks and aberrations, when compared with wild-type ES cells (Table 1). More striking was the strong increase (from 3% to 13% of all cells) in the number of cells displaying many chromatid abnormalities (resulting from more than six breaks, Table 1 and Figure 5) and the increased number of aberrations in this subset of cells. Since most of the cells were in S phase during UV-C-irradiation, the limited number of cells with heavily damaged genomes again points to a temporally restricted role of the BRCT domain of Rev1 in the resolution of replication arrests by TLS.

Table 1.

Increased frequencies of chromatid-type of aberrations in Rev1B/B ES cells after the first cycle

| Cell linea | UV-C dose (J/m2) | Fixation time (h) | Cycle after treatment (%) | Cells with chromatid aberrationsb (%) | Multi aberrant cellsc (%) | Number of aberrations per 100 cellsd | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | B′e | Chexf | |||||

| WT | 0 | 24 | 7 | 93 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 254 | 0 | 24 | 11 | 89 | 0 | 3 | 0 | ND | ND |

| 243 | 0 | 24 | 10 | 90 | 0 | 4 | 0 | ND | ND |

| WT | 2 | 28 | 27 | 72 | 1 | 28 | 3 | 19 | 32 |

| 254 | 2 | 28 | 51 | 49 | 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 243 | 2 | 28 | 42 | 57 | 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| WT | 2 | 32 | 11 | 85 | 4 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 254 | 2 | 32 | 32 | 63 | 5 | 46 | 12 | 30 | 44 |

| 243 | 2 | 32 | 32 | 66 | 2 | 50 | 14 | 46 | 54 |

aWT, wild type; 254, Rev1B/B-254; 243, Rev1B/B-243.

bAll cells with one or more aberrations. Only cells in the first cycle after treatment were scored, as judged by BrdU incorporation.

cMulti-aberrations defined as more than two chromatid breaks and two exchanges or three chromatid exchanges. ND: Not determined.

dExcluding aberrations in multi aberrant cells.

eChromatid breaks.

fChromatid exchanges and ring chromatids.

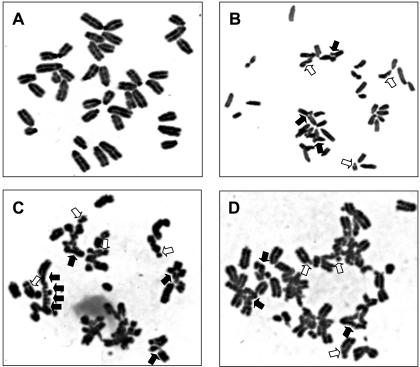

Figure 5.

Chromosome aberrations in UV-C-irradiated Rev1B/B-254 cells. (A) Cell not showing visible aberrations. (B–D) Cells containing multiple aberrations. In B and C, many chromosomes contain breaks and are undergoing chromatid exchanges. Some, but not all, of the chromatid breaks (open arrows) and chromatid exchanges (closed arrows) are indicated.

We analyzed second-division cells from the same experiment for the presence of SCE. The number of SCE in untreated cells was indistinguishable between untreated wild-type and mutant cells. Although after UV-C exposure the number of SCE per metaphase was increased in cells of both genotypes, no significant difference in the level of SCE induction was found between the wild-type and mutant cell lines tested (Table 2).

Table 2.

Levels of SCE in Rev1B/B and wild-type ES cells

| Cells | UV-C-treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 J/m2 | 2 J/m2 | |

| Wild type | 10.6 ± 3.4a | 48.0 ± 15.7 |

| Rev1B/B-254 | 12.9 ± 4.3 | 51.1 ± 18.1 |

| Rev1B/B-243 | 14.2 ± 4.1 | 54.6 ± 21.9 |

aNumber of SCE per cell ± standard error.

Involvement of the Rev1 BRCT domain in spontaneous and DNA damage-induced mutagenesis

To investigate whether the Rev1 BRCT domain is involved in the TLS of endogenous DNA damage, we analyzed the spontaneous mutagenesis at Hprt in Rev1B/B cell lines. Although no significant differences in the spontaneous mutant frequency were found between the different cell lines (Figure 6), analysis of RT–PCR products of Hprt mRNA from the spontaneous mutants revealed clear differences between mutant and wild-type cell lines. Thus, we were able to obtain Hprt cDNA from only 37% of the mutants (9/24), although Aprt was readily amplified from all the mutants in a multiplex RT–PCR reaction with Hprt (data not shown). This is in contrast with wild-type cells where we obtained Hprt RT–PCR product in 70% of all spontaneous Hprt-mutant clones. Limited analysis of genomic deletions by performing PCR of Hprt exons 3, 7 and 8 in the spontaneous Hprt mutants revealed the presence of deletions in one or more of these exons in 33% of all spontaneous Rev1B/B Hprt mutants, as opposed to 20% of the wild-type Hprt mutants. In agreement, substitution mutations and single nucleotide frameshifts, indicative of TLS events, were found in only 13% of the Rev1B/B Hprt mutant clones when compared with 40% of the wild-type clones.

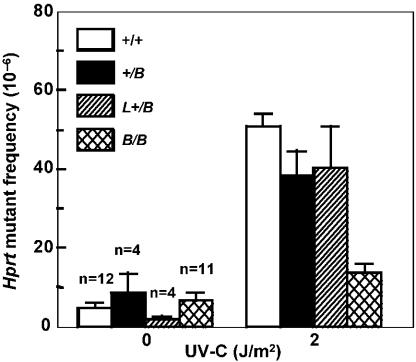

Figure 6.

Hprt mutant frequencies in ES cells. Following treatment, cells were cultured for 6 days before selection of 6-thioguanine-resistant clones. +/+, wild type; +/B, Rev1+/B; L+/B, Rev1L+/B; B/B, Rev1B/B-254.

To examine the role of the BRCT domain of Rev1 in mutagenesis induced by exogenous DNA damage, various mutant and wild-type ES cell lines were exposed to UV-C light followed by determination of mutant frequencies at Hprt. All homozygous Rev1 BRCT mutant ES cell lines that were generated in this study showed an approximately 3-fold reduction in the UV-C-induced Hprt mutant frequency when compared with the Rev1-proficient cell lines tested (Figure 6; data not shown). Of note, Rev1L−/B cells, containing the BRCT deletion in one Rev1 allele in the absence of a marker gene, behaved similarly to the other Rev1B/B cell lines (data not shown), validating the phenotype. We further investigated the involvement of the Rev1 BRCT domain in the bypass of UV-C-induced pyrimidine dimers by performing a mutational spectra analysis of independent Hprt mutants from wild-type ES cells and from Rev1B/B ES cells, exposed to 2 J/m2 of UV-C (Table 3; Supplementary Table). The fraction of base pair substitutions at dipyrimidine sites in the non-transcribed strand, as opposed to the transcribed strand appeared slightly, but not significantly, higher in wild-type cells (49%) than in the Rev1B/B ES cells (35%). Although GC to AT transitions at dipyrimidine sites dominated the single base pair substitutions in both cell populations, there are no transversions found in the Rev1-mutant line. Moreover, no single base pair substitutions at TT dipyrimidine sites were found in UV-C-exposed Rev1B/B ES cells, in contrast to wild-type cells, in which 24% of the base pair substitutions were localized at TT sites (Table 3; Supplementary Table). This result is statistically significant (P ≤ 0.02, χ2 test) and indicates that in vivo UV photoproducts at TT dimers are specific substrates for the error-prone TLS mediated by the BRCT domain of Rev1.

Table 3.

Summary of Hprt gene mutations of UV-C-exposed Rev1B/B-254 and wild type cells

| Target | Wild type | Rev1B/B | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutations at dipyrimidine sites | |||

| Single base pair substitutions | 45 | 20 | |

| Transitions | |||

| GC > AT | CCTa | 11 | 6 |

| TCCa | 10 | 6 | |

| CT | 2 | 1 | |

| CC | 3 | 4 | |

| TC | 3 | 3 | |

| AT > GC | CTTa | 2 | 0 |

| TC | 1 | 0 | |

| Transversions | |||

| GC > TA | TC | 1 | 0 |

| TCCa | 1 | 0 | |

| AT > CG | CTTa | 1 | 0 |

| AT > TA | TT | 10 | 0 |

| Double base pair substitutions | 5 | 6 | |

| Mutations at non-dipyrimidine sites | |||

| Single base pair substitutions | 0 | 3 | |

| Transversions | |||

| GC > TA | 0 | 1 | |

| AT > CG | 0 | 1 | |

| AT > TA | 0 | 1 | |

| Double base pair substitutions | 1 | 1 | |

| Othersb | 30 | 40 | |

aMutations present in tripyrimidine sequences do not allow to define the dimer site of the UV-C-induced lesion.

bMutants that either display a frameshift, lack one or more exons in the Hprt mRNA, express no Hprt mRNA or contain no mutation in the coding region.

SHM is normal in Rev1 BRCT-mutant mice

Two independent Rev1+/B ES cell clones were used to generate chimeric mice. Both clones yielded germ line transmission of the mutated allele. After intercrossing of the heterozygous F2, homozygous Rev1B/B offspring was obtained in normal Mendelian ratios: 53 wild-type, 110 heterozygous and 50 homozygous offsprings. Rev1B/B mice were healthy, displayed no overt abnormalities and had no obvious pathology (the oldest mice were 19-months-old, the median age was 14 months). In addition, both male and female Rev1B/B mice displayed normal fertility; offspring of these mice, crossed to Rev1+/B mice segregated according to Mendel.

Uracil and abasic nucleotides are excellent substrates for Rev1 in vitro and, in yeast, in vivo (5–7,10,14). In germinal center B cells of vertebrates, uracil and abasic sites are generated by the activation-induced deoxycytidine deaminase and base excision repair, respectively, and their formation plays an essential role in SHM. This highly mutagenic process occurs in the genomic region, encoding the variable region of an immunoglobulin protein in antigen-stimulated germinal center B cells and is hypothesized to depend on TLS (2). To test the role of the Rev1 BRCT domain in SHM in mammals, SHM was analyzed in mice of mixed background (129/Ola × C57Bl/6; 1:3 ratio) by sequencing functionally rearranged Vλ1 genes from memory B cells of ∼5 to 10-months-old wild-type and Rev1B/B mice. The frequency of SHM was similar for both genotypes (Table 4). Moreover, the pattern of SHM in germinal center B cells, with respect to (i) the frequency and ratio of transitions versus transversions (Table 4) and (ii) the distribution of base pair substitutions along the rearranged Vλ1 gene (data not shown) appeared to be normal in Rev1B/B mice. In conclusion, deleting the Rev1 BRCT domain does not interfere with the viability of the cell or of the organism and has no effect on SHM. In addition, these data suggest that the BRCT domain of Rev1 is not involved in regulating a bypass at uracil and abasic residues in vivo.

Table 4.

Number and percentage of nucleotide exchanges in Vλ1 genes of memory B cells from wild-type and Rev1B/B mice

| Wild type | Rev1B/B | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To | A | G | C | T | % | A | G | C | T | % |

| From | ||||||||||

| A | – | 75 | 31 | 30 | 43.0 | – | 63 | 38 | 50 | 42.2 |

| G | 61 | – | 12 | 15 | 27.8 | 51 | – | 19 | 20 | 25.1 |

| C | 6 | 10 | – | 52 | 21.5 | 8 | 14 | – | 64 | 24.0 |

| T | 12 | 5 | 7 | – | 7.6 | 8 | 5 | 18 | – | 8.7 |

| % | 25.0 | 28.5 | 15.8 | 30.7 | 100 | 18.7 | 22.9 | 20.9 | 37.4 | 100 |

DISCUSSION

Based on the important role of the BRCT domain of REV1 in mutagenesis in yeast, we have generated ES cells and mice carrying a truncation of the Rev1 BRCT domain. Using these tools, we investigated the role of the BRCT domain of Rev1 in mutagenesis, including SHM, and in DNA damage responses. The Rev1B/B ES cells display a normal growth and cloning efficiency and most probably have retained deoxycytidyl transferase activity (10,14), as well as the C-terminal binding to other TLS polymerases (39–41). In contrast, Rev1-deficient chicken DT40 cells display a strongly reduced viability (4), indicating that a complete loss of Rev1 in vertebrate cells has a severe impact on cellular viability. Thus, although clearly involved in cell cycle responses to exogenous DNA damage and in mutagenesis, the BRCT domain of Rev1 is not essential for normal viability.

Compared with wild-type cells, Rev1B/B ES cells and Rev1-deficient DT40 cells (4) showed a prolonged late S and G2-phases following UV-C exposure. In fibroblasts from XP-V patients, lacking a functional TLS Pol η that is responsible for bypass of CPDs, UV-C treatment induces a similarly extended S-phase (37,42).

In most of the Rev1 BRCT mutant cells, like in Rev1-deficient chicken DT40 cells and in human Pol η-deficient fibroblasts (4,37,43,44), UV-C induced a similar frequency of SCE and chromatid aberrations as in wild-type cells. Only in a limited number (13%) of Rev1B/B cells, many arrested replication forks do collapse, as evidenced by the abnormally high number of chromatid aberrations that is induced by UV-C. This phenotype supports the temporarily limited requirement, likely during the late S phase, of the Rev1 BRCT domain for regulating TLS. In addition, these data indicate that arrested replication forks at this stage of the cell cycle are refractory to repair by DA (45). Conversely, arrested replication forks that normally are resolved by DA can be shuttled into a (mutagenic) TLS pathway since ‘knocking down’ hMms2, an ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme involved in DA, results in the enhancement of UV-C-induced mutagenesis (46). Moreover, in mouse embryos and chicken DT40 cells deficient for the Rev3 TLS polymerase (47,48) and in UV-C-exposed Pol η-deficient fibroblasts (37), chromatid-type aberrations and translocations accumulate. This underscores the relevance of TLS in maintaining genome stability in the presence of DNA damage. Recently, the UV-C-induced S phase arrest in mammalian cells was attributed to the inhibition of initiation of replication by the ATR-dependent checkpoint (49,50). In S.cerevisiae, this checkpoint mainly affects the late-firing replication origins (51). BRCT domains bind proteins phosphorylated by ATR (and ATM) of which ATR is essential for the replicational stress response following exposure to DNA damaging agents (22–24). It is therefore tempting to speculate that the Rev1 BRCT domain is involved in regulating an ATR-mediated TLS response, predominantly during the late S phase.

Most spontaneous Hprt mutants of Rev1B/B ES cells have lost the expression of Hprt mRNA. This was due to the frequent presence of intragenic deletions. These deletions are probably caused by the mutagenic end joining of DNA breaks originating at sites of stalled replication forks at sites of endogenous DNA damage. This provides further evidence for the involvement of the Rev1 BRCT domain in DNA damage bypass and for the induction of DSB at collapsed replication forks in the mutant. In the mutant cells, nucleotide substitution- and −1 frameshift mutagenesis is reduced but not absent, indicating that the BRCT domain of Rev1 is important for TLS of a subset of endogenous DNA lesions in vivo (also see below).

UV-C light induced 3-fold less mutations in all Rev1 mutant cell lines compared with wild-type cells, in agreement with a role of the BRCT domain of Rev1 in DNA damage-induced TLS and mutagenesis. Similarly, the rev1-1 yeast strain, carrying a mutation in the REV1 BRCT domain, is hypomutable by UV-C (25,26); specifically, TLS on (6-4) PP photoproducts is lost (14). Our mutational spectra analysis on UV-C-induced Hprt mutants of wild-type ES cells confirms published data, showing that deoxycytosine is very rarely inserted opposite UV-C-induced pyrimidine dimers in wild-type S.cerevisiae and mammalian cells (15,16,52). Our data entail a noncatalytic role for Rev1 in the TLS of UV-C-induced DNA damage. Of note, we found that Rev1B/B ES cells have lost all UV-C-induced transversions at TT dipyrimidine sites. This implies an essential role for the Rev1 BRCT domain in allowing error-prone TLS of photoproducts at TT sites. Remarkably, in Pol η-deficient fibroblasts derived from XP-V patients, the UV-C-induced frequency of AT to TA transversions at TT dimer sites is strongly increased (52,53). Thus, the frequency and spectrum of UV-C-induced mutations in our Rev1B/B cells and in XP-V-derived cells are complementary. This indicates that the elevated UV-induced mutagenesis in these patients, underlying the early onset of skin cancer, may be dependent on a compensatory Rev1 BRCT domain-dependent pathway of TLS.

It is unclear which TLS pathway is responsible for the residual UV-C-induced mutagenesis in Rev1B/B ES cells. Since the C-terminus of mammalian Rev1 interacts with TLS pols η, ι and κ and with Rev7 (39–41), Rev1 may regulate the activity of either of these polymerases. Although our Rev1B/B cells (129/Ola background) are defective for pol ι due to a nonsense codon mutation in exon 2 (54), preliminary results suggest that pol ι does not play a role in UV-induced damage responses (H. Vrieling, data not shown). Pol κ is unable to bypass CPDs or (6–4) PPs in vitro (55). Therefore, pol ζ, which can weakly bypass pyrimidine dimers in vitro (27,56), is a candidate for inducing a residual mutagenesis in our Rev1B/B cells. Of note, murine cells deficient for Rev3, encoding the catalytic subunit of pol ζ, are extremely sensitive to UV-C light (57; unpublished results), implying a role in the bypass of UV-C-induced DNA damage.

We have generated Rev1B/B mice, derived from Rev1+/B ES cells. These mice display no overt phenotype and have normal SHM, a process that strongly depends on the generation of uracil and abasic sites via deamination of cytosine at the non-transcribed strand of transcriptionally active variable regions of immunoglobulin genes in germinal center B cells (2). Normal nucleotide exchange patterns of SHM in Rev1B/B mice appear to be in contrast with the important role of the Rev1-BRCT motif in regulating TLS of abasic sites in yeast (14). Possibly, the catalytic domain of Rev1, which probably has normal activity in the Rev1B/B mutant, performs normal TLS of abasic sites and uracil residues, in the absence of the regulatory BRCT domain. In contrast to the BRCT domain of Rev1, its catalytic domain might be involved in SHM since chicken DT40 Rev1-deficient cells show almost no non-templated SHM (4). However, in these cells, most SHM is induced by copying of immunoglobulin pseudogenes into rearranged variable light and heavy variable regions via gene conversion, indicating that non-templated SHM by Rev1 plays only a minor role (4). Alternatively, in our Rev1B/B mutant, one or more of the other TLS polymerases might take over the function of Rev1 in SHM although, in view of the unique and limited deoxycytidyl transferase activity of Rev1, this is expected to result in an altered SHM spectrum.

We predict that exogenous DNA damage-induced mutagenesis, and carcinogenesis, is reduced in Rev1B/B mice. Therefore, these mice will be a valuable tool to investigate the feasibility of inhibition of the Rev1 pathway to counteract the malignant consequences of exposure to mutagens, including chemotherapeutics.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at NAR Online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Suzie Berry, Firouz Darroudi and Angela de Kleynen for technical assistance, Drs C. Lawrence and P. Gibbs for providing Rev1 cDNA sequences before publication and Leon Mullenders for stimulating discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. This study was financially supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (Project no RUL 2001-2517). This work is dedicated to the late Jan Eeken. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the Dutch Cancer Society (Project no RUL 2001–2517).

REFERENCES

- 1.Broomfield S., Hryciw T., Xiao W. DNA postreplication repair and mutagenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 2001;486:167–184. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Z., Woo C.J., Iglesias-Ussel M.D., Ronai D., Scharff M.D. The generation of antibody diversity through somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1–11. doi: 10.1101/gad.1161904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohmori H., Friedberg E.C., Fuchs R.P.P., Goodman M.F., Hanaoka F., Hinkle D., Kunkel T.A., Lawrence C.W., Livneh Z., Nohmi T., Prakash L., Prakash S., Todo T., Walker C.G., Wang Z., Woodgate R. The Y-family of DNA polymerases. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:7–8. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simpson L.J., Sale J.E. Rev1 is essential for DNA damage tolerance and non-templated immunoglobulin gene mutation in a vertebrate cell line. EMBO J. 2003;22:1654–1664. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson J.R., Lawrence C.W., Hinkle D.C. Deoxycytidyl transferase activity of yeast REV1 protein. Nature. 1996;382:729–731. doi: 10.1038/382729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin W., Xin H., Zhang Y., Wu X., Yuan F., Wang Z. The human REV1 gene encodes for a DNA template-dependent dCMP transferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4468–4475. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haracska L., Prakash S., Prakash L. Yeast Rev1 protein is a G template-specific DNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:15546–15551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masuda Y., Takahashi M., Tsunekuni N., Minami T., Sumii M., Miyagawa K., Kamiya K. Deoxycytidyl transferase activity of the human REV1 protein is closely associated with the conserved polymerase domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:15051–15058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008082200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masuda Y., Kamiya K. Biochemical properties of the human REV1 protein. FEBS Lett. 2002;520:88–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02773-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masuda Y., Takahashi M., Fukuda S., Sumii M., Kamiya K. Mechanisms of dCMP transferase reactions catalyzed by mouse Rev1 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:3040–3046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y., Wu X., Rechkoblit O., Geacintov N.E., Taylor J.-S., Wang Z. Response of human REV1 to different DNA damage: preferential dCMP insertion opposite the lesion. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1630–1638. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson R.E., Torres-Ramos C.A., Izumi T., Mitra S., Prakash S., Prakash L. Identification of APN2, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog of the major human AP endonuclease HAP1, and its role in the repair of abasic sites. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3137–3143. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haracska L., Unk I., Johnson R.E., Johansson E., Burgers P.M.J., Prakash S., Prakash L. Roles of yeast DNA polymerases δ and ζ and of Rev1 in the bypass of abasic sites. Genes Dev. 2001;15:945–954. doi: 10.1101/gad.882301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson J.R., Gibbs P.E.M., Nowicka A.M., Hinkle D.C., Lawrence C.W. Evidence for a second function for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rev1p. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;37:549–554. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibbs P.E.M., Kilbey B.J., Banerjee S.W., Lawrence C.W. The frequency and accuracy of replication past a thymidine-thymidine cyclobutane dimer are very different in Sacchoromyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:2607–2612. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2607-2612.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbs P.E.M., Borden A., Lawrence C.W. The T-T pyrimidine (6-4) pyrimidinone UV photoproduct is much less mutagenic in yeast than in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;11:1919–1922. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.11.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbs P.E.M., Wang X.-D., Li Z., McManus T.P., McGregor W.G., Lawrence C.W., Maher V.M. The function of the human homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae REV1 is required for mutagenesis induced by UV light. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:4186–4191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark D.R., Zacharias W., Panaitescu L., McGregor W.G. Ribozyme-mediated REV1 inhibition reduces the frequency of UV-induced mutations in the human HPRT gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4981–4988. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerlach V.L., Aravind L., Gotway G., Schultz R.A., Koonin E.V., Friedberg E.C. Human and mouse homologs of Escherichia coli DinB (DNA polymerase IV), members of the UmuC/DinB superfamily. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:11922–11927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callebaut I., Mornon J.-P. From BRCA1 to RAP1: a widespread BRCT module closely associated with DNA repair. FEBS Lett. 1997;400:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huyton T., Bates P.A., Zhang X., Sternberg M.J.E., Freemont P.S. The BRCA1 C-terminal domain: structure and function. Mutat. Res. 2000;460:319–332. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(00)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manke I.A., Lowery D.M., Nguyen A., Yaffe M.B. BRCT repeats as phosphopeptide-binding modules involved in protein targeting. Science. 2003;302:636–639. doi: 10.1126/science.1088877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez M., Yu X., Chen J., Songyang Z. Phosphopeptide binding specificities of BRCT domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:52914–52918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu X., Silva Chini C.C., He M., Mer G., Chen J. The BRCT domain is a phospho-protein binding domain. Science. 2003;302:639–642. doi: 10.1126/science.1088753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemontt J.F. Mutants of yeast defective in mutation induced by ultraviolet light. Genetics. 1971;68:21–33. doi: 10.1093/genetics/68.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larimer F.W., Perry J.R., Hardigree A.A. The REV1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: isolation, sequence, and functional analysis. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:230–237. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.230-237.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawrence C.W. Cellular roles for DNA polymerase ζ and Rev1 protein. DNA Repair. 2002;1:425–435. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao Y., Weaver D.T. Conditional gene targeted deletion by Cre recombinase demonstrates the requirement for the double-strand break repair Mre11 protein in murine embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2985–2991. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.15.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg I.M. Protein Analysis and Purification: Benchtop Techniques. Boston, Cambridge: Birkhäuser; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J., Fritsch E.F., Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perry P., Wolff S. New Giemsa method for the differential staining of sister chromatids. Nature. 1974;251:156–158. doi: 10.1038/251156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Sloun P.P.H., Jansen J.G., Weeda G., Mullenders L.H.F., Van Zeeland A.A., Lohman P.H.M., Vrieling H. The role of nucleotide excision repair in protecting embryonic stem cells from the genotoxic effects of UV-induced DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3276–3282. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.16.3276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wijnhoven S.W.P., Kool H.J.M., van Oostrom C.T.M., Beems R.B., Mullenders L.H.F., van Zeeland A.A., van der Horst G.T.J., Vrieling H., van Steeg H. The relationship between benzo[a]pyrene-induced mutagenesis and carcinogenesis in repair-deficient Cockayne syndrome group B mice. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5681–5687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobs H., Fukita Y., van der Horst G.T.J., de Boer J., Weeda G., Essers J., de Wind N., Engelward B., Samson L., Verbeek S., Ménissier de Murcia J., de Murcia G., te Riele H., Rajewsky K. Hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes in memory B cells of DNA repair-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:1735–1743. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.11.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu L.J., Baxter J.R., Wang M.Y., Harper B.L., Tasaka F., Kohda K. Induction of covalent DNA modifications and micronucleated erythrocytes by 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide in adult and fetal mice. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6192–6198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beranek D.T. Distribution of methyl and ethyl adducts following alkylation with monofunctional alkylating agents. Mutat. Res. 1990;231:11–30. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(90)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cordeiro-Stone M., Frank A., Bryant M., Oguejiofor I., Hatch S.B., McDaniel L.D., Kaufman W.F. DNA damage responses protect xeroderma pigmentosum variant from UV-C-induced clastogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:959–965. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Limoli C.L., Giedzinski E., Bonner W.M., Cleaver J.E. UV-induced replication arrest in the xeroderma pigmentosum variant leads to DNA double-strand breaks, γ-H2AX formation, and Mre11 relocalization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:233–238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231611798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo C., Fischhaber P.L., Luk-Paszyc M.J., Masuda Y., Zhou J., Kamiya K., Kisker C., Friedberg E.C. Mouse Rev1 protein interacts with multiple DNA polymerases involved in translesion DNA synthesis. EMBO J. 2003;22:6621–6630. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohashi E., Murakumo Y., Kanjo N., Akagi J.-I., Masutani C., Hanaoka F., Ohmori H. Interaction of hREV1 with three human Y-family DNA polymerases. Genes Cells. 2004;9:523–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tissier A., Kannouche P., Reck M.-P., Lehmann A., Fuchs R.P.P., Cordonnier A. Co-localization in replication foci and interaction of human Y-family members, DNA polymerase polη and REV1 protein. DNA Repair. 2004;3:1503–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bullock S.K., Kaufmann W.K., Cordeiro-Stone M. Enhanced S phase delay and inhibition of replication of an undamaged shuttle vector in UV-C-irradiated xeroderma pigmentosum variant. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:233–241. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Weerd-Kastelein E.A., Keijzer W., Rainaldi G., Bootsma D. Induction of sister chromatid exchanges in xeroderma pigmentosum cells after exposure to ultraviolet light. Mutat. Res. 1977;45:252–261. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(77)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cleaver J.E., Afzal V., Feeney L., McDowell M., Sandinski W., Volpe J.P.G., Busch D.B., Coleman D.M., Ziffer D.W., Yu Y., Nagasawa H., Little J.B. Increased ultraviolet light sensitivity and chromosomal instability related to p53 function in the xeroderma pigmentosum variant. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1102–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osborn A.J., Elledge S.J., Zou L. Checking on the fork: the DNA-replication stress-response pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:509–516. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Z., Xiao W., McCormick J.J., Maher V.M. Identification of a protein essential for a major pathway used by human cells to avoid UV-induced DNA damage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:4459–4464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062047799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Sloun P.P.H., Varlet I., Sonneveld E., Boei J.J.W.A., Romeijn R.J., Eeken J.C.J., de Wind N. Involvement of mouse Rev3 in tolerance of endogenous and exogenous DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:2159–2169. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2159-2169.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sonoda E., Okada T., Zhao G.Y., Tateishi S., Araki K., Yamaizumi M., Yagi T., Verkaik N., van Gent D.C., Takata M., Takeda S. Multiple roles of Rev3, the catalytic subunit of pol ζ in maintaining genome stability in vertebrates. EMBO J. 2003;22:3188–3197. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heffernan T.P., Simpson D.A., Frank A.R., Heinloth A.N., Paules R.S., Cordeiro-Stone M., Kaufmann W.K. An ATR- and Chk1-dependent S checkpoint inhibits replicon initiation following UV-C-induced DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:8552–8561. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8552-8561.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miao H., Seiler J.A., Burhans W.C. Regulation of cellular and SV40 origins of replication by Chk1-dependent intrinsic and UV-C radiation-induced checkpoints. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:4295–4304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santocanale C., Diffley J.F.X. A Mec1- and Rad53-dependent checkpoint controls late firing origins of DNA replication. Nature. 1998;359:615–618. doi: 10.1038/27001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y.-C., Maher V.M., Mitchell D.L., McCormick J.J. Evidence from mutation spectra that the UV hypermutability of xeroderma pigmentosum variant cells reflect abnormal, error-prone replication on a template containing photoproducts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:4276–4283. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stary A., Kannouche P., Lehmann A.R., Sarasin A. Role of DNA Polymerase η in the UV mutation spectrum in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:18767–18775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McDonald J.P., Frank E.G., Plosky B.S., Rogozin I.B., Masutani C., Hanaoka F., Woodgate R., Gearhart P.J. 129-derived strains of mice are deficient in DNA polymerase ι and have normal immunoglobulin hypermutation. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:635–643. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohashi E., Ogi T., Kusumoto R., Iwai S., Masutani C., Hanaoka F., Ohmori H. Error-prone bypass of certain DNA lesions by the human DNA polymerase κ. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1589–1594. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo D., Wu X., Rajpal D.K., Taylor J.-S., Wang Z. Translesion synthesis by yeast DNA polymerase zeta from templates containing lesions of ultraviolet radiation and acetylaminofluorene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2875–2883. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.13.2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zander L., Bemark M. Immortalized mouse cell lines that lack a functional Rev3 gene are hypersensitive to UV irradiation and cisplatin treatment. DNA Repair. 2004;3:743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.