Abstract

Background

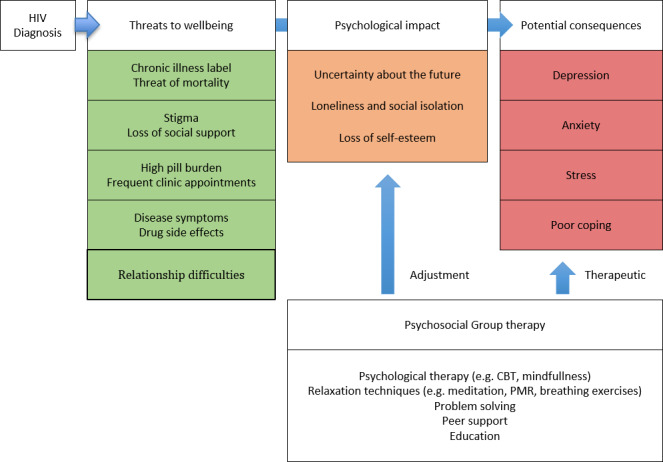

Being diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and labelled with a chronic, life‐threatening, and often stigmatizing disease, can impact on a person's well‐being. Psychosocial group interventions aim to improve life‐functioning and coping as individuals adjust to the diagnosis.

Objectives

To examine the effectiveness of psychosocial group interventions for improving the psychological well‐being of adults living with HIV/AIDS.

Search methods

We searched the following electronic databases up to 14 March 2016: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) published in the Cochrane Library (Issue 2, 2016), PubMed (MEDLINE) (1996 to 14 March 2016), Embase (1996 to 14 March 2016), and Clinical Trials.gov.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs that compared psychosocial group interventions with versus control (standard care or brief educational interventions), with at least three months follow‐up post‐intervention. We included trials that reported measures of depression, anxiety, stress, or coping using standardized scales.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened abstracts, applied the inclusion criteria, and extracted data. We compared continuous outcomes using mean differences (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), and pooled data using a random‐effects model. When the included trials used different measurement scales, we pooled data using standardized mean difference (SMD) values. We reported trials that we could not include in the meta analysis narratively in the text. We assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included 16 trials (19 articles) that enrolled 2520 adults living with HIV. All the interventions were multifaceted and included a mix of psychotherapy, relaxation, group support, and education. The included trials were conducted in the USA (12 trials), Canada (one trial), Switzerland (one trial), Uganda (one trial), and South Africa (one trial), and published between 1996 and 2016. Ten trials recruited men and women, four trials recruited homosexual men, and two trials recruited women only. Interventions were conducted with groups of four to 15 people, for 90 to 135 minutes, every week for up to 12 weeks. All interventions were conducted face‐to‐face except two, which were delivered by telephone. All were delivered by graduate or postgraduate trained health, psychology, or social care professionals except one that used a lay community health worker and two that used trained mindfulness practitioners.

Group‐based psychosocial interventions based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) may have a small effect on measures of depression, and this effect may last for up to 15 months after participation in the group sessions (SMD −0.26, 95% CI −0.42 to −0.10; 1139 participants, 10 trials, low certainty evidence). Most trials used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), which has a maximum score of 63, and the mean score in the intervention groups was around 1.4 points lower at the end of follow‐up. This small benefit was consistent across five trials where participants had a mean depression score in the normal range at baseline, but trials where the mean score was in the depression range at baseline effects were less consistent. Fewer trials reported measures of anxiety, where there may be little or no effect (four trials, 471 participants, low certainty evidence), stress, where there may be little or no effect (five trials, 507 participants, low certainty evidence), and coping (five trials, 697 participants, low certainty evidence).

Group‐based interventions based on mindfulness have not demonstrated effects on measures of depression (SMD −0.23, 95% CI −0.49 to 0.03; 233 participants, 2 trials, very low certainty evidence), anxiety (SMD −0.16, 95% CI −0.47 to 0.15; 62 participants, 2 trials, very low certainty evidence), or stress (MD −2.02, 95% CI −4.23 to 0.19; 137 participants, 2 trials, very low certainty evidence). No mindfulness based interventions included in the studies had any valid measurements of coping.

Authors' conclusions

Group‐based psychosocial interventions may have a small effect on measures of depression, but the clinical importance of this is unclear. More high quality evidence is needed to assess whether group psychosocial intervention improve psychological well‐being in HIV positive adults.

2 April 2019

Up to date

All studies incorporated from most recent search

All eligible published studies found in the last search (14 Mar, 2016) were included

Plain language summary

Does group therapy improve well‐being in people living with HIV?

Cochrane researchers conducted a review of the effects of group therapy for people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). After searching for relevant trials up to 14 March 2016, they included 16 trials reported in 19 articles that enrolled 2520 adults living with HIV. The included trials were conducted in the USA (12 trials), Canada (one trial), Switzerland (one trial), Uganda (one trial), and South Africa (one trial), and published between 1996 and 2016. Ten trials recruited men and women, four trials recruited homosexual men, and two trials recruited women only.

What is group therapy and how might if benefit people with HIV?

Group therapy aims to improve the well‐being of individuals by delivering psychological therapy in a group format, which can encourage the development of peer support and social networks. Group therapy often also incorporates training in relaxation techniques and coping skills, and education on the illness and its management.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) causes a chronic, life threatening, and often stigmatising disease, which can impact on a person's well‐being. Group therapy could help people living with HIV to adapt to knowing they have HIV, or recover from depression, anxiety, and stress.

What the research says

Group‐based therapy based on cognitive behavioural therapy may have a small effect on measures of depression, and this effect may last for up to 15 months after participation in the group sessions (low certainty evidence). This effect was apparent in groups who did not appear to be depressed on clinical scoring systems before the therapy started. The research also showed there may be little or no effect on measures of anxiety, stress, and coping (low certainty evidence).

Group‐based interventions based on mindfulness have been studied in two small trials, and have not demonstrated effects on measures of depression, anxiety or stress (all very low certainty evidence). No mindfulness based interventions included in the studies had any valid measurements of coping.

Overall, the review suggests that existing interventions have little to no effect in increasing psychological adjustment to living with HIV. More good quality studies are required to inform good practice and evidence.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) causes a chronic, life‐threatening disease, characterized by progressive destruction of the immune system and increasing susceptibility to infection and malignancy. Consequently, despite the availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), which has revolutionized treatment, a new diagnosis of HIV carries multiple threats to a person's psychological well‐being (Lawless 1996; Hudson 2001; Colbert 2010). Being labelled with a chronic illness, especially one associated with the stigma of HIV, and the accompanying need to take multiple daily medications with unpleasant side effects can lead to uncertainty about the future, relationship difficulties, social isolation, and loss of self esteem. Failure to adjust can in turn lead to clinical depression, anxiety, stress, and poor coping (Vanable 2006). Particularly, the prevalence of depression and suicide in people living with HIV/AIDS is very high (Cooperman 2005; Rezaee 2013; Bhatia 2014; Anagnostopoulos 2015).

Description of the intervention

Psychosocial group interventions, by definition, include some form of psychological therapy such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) delivered in a group format. However, many will also include additional components that may also have effects on psychological well‐being, such as: relaxation techniques and stress management; problem solving and coping skills; social or peer support; and education and empowerment (see Figure 1).

1.

Conceptual framework

How the intervention might work

Psychological well‐being is usually conceptualized as some combination of positive affective states such as happiness and functioning, with optimal effectiveness in individual and social life (Deci 2008). As summarized by Huppert 2009 (p.137): “Psychological well‐being is about lives going well. It is the combination of feeling good and functioning effectively”. By definition therefore, people with high psychological well‐being report feeling happy, capable, well‐supported, and satisfied with life.

Fundamentals to psychological well‐being for HIV‐positive people are positive coping strategies and perceived social support (Friedland 1996; Côté 2002; Turner‐Cobb 2002). As compared to individual therapy, group therapy is believed to confer a wider range of psychosocial benefits. In a well‐functioning group, members may give and receive motivational support and encouragement for self‐efficacy, and through shared experiences can empower each other to access services, adhere to treatment, and cope with stigma and stress (Kelly 1998; Metcalfe 1998; Moneyham 1998; Gielen 2001; Walker 2002; Peterson 2003). This is contrasted with the problem of stigma inherent in joining groups defined by HIV‐status (Roopnaraine 2012). Being in a group helps participants to feel they are not alone in dealing with their problems and also encourages relating to yourself and others in healthier ways. Group formats are also cost effective and resource effective, reaching more patients than individual or one‐on‐one therapies. This is advantageous, particularly in resource‐poor settings.

Why it is important to do this review

A positive diagnosis of HIV means a lifetime of medical treatment, but also dealing with the psychological effects of living with a chronic disease. Psychosocial interventions focus on stress management, coping, and self efficacy and have the potential to have a positive effect on peoples' mental health and treatment adherence. However, the evidence base of what works to improve the psychological well‐being of people living with HIV, particularly those in high‐risk groups and those living in resource‐poor settings, is lacking. In order to inform practice and research, this Cochrane Review can contribute to evidence on what types of psychosocial interventions are most effective to improve psychological well‐being for HIV‐positive adults. Certainty of the evidence is also important to define future studies, and whether findings are consistent and can be generalized across populations and settings.

Objectives

To examine the effectiveness of psychosocial group interventions for improving the psychological well‐being of adults living with HIV/AIDS.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs with at least three months follow‐up post‐intervention.

Types of participants

HIV‐positive adults with and without current psychological illness.

Types of interventions

Any psychosocial intervention delivered in a group format that aims to improve the psychological well‐being of people living with HIV. This might include the following types of interventions.

Interventions conducted in hospitals, clinics, or community settings.

Interventions delivered face‐to‐face or via telephone or video link.

Interventions focused on providing information and psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, stress appraisal and management, relaxation and mindfulness, adaptive and productive coping, assertiveness training and social support.

Interventions based on any theoretical approach.

The control intervention may be standard care, a waiting list for future intervention, or a brief educational/psychosocial intervention delivered in‐group or individual format.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Improved psychological well‐being of HIV‐positive people measured by decreases in depression scores using validated scales.

Secondary outcomes

Measures of anxiety using validated scales.

Measures of stress using validated scales.

Measures of coping using validated scales.

All outcomes must be measures at baseline, post‐intervention and at a time point at least three months after the intervention.

Search methods for identification of studies

The HIV/AIDS Information Specialist, Joy Oliver, assisted the review author team to identify trials for inclusion in the review.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases up to 14 March 2016 using the search strategy presented in Appendix 1: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) published in the Cochrane Library (Issue 2, 2016), PubMed (MEDLINE) (1996 to 14 March 2016), and Embase (1996 to 14 March 2016). We also checked Clinical Trials.gov using the search terms in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference list of all papers that matched our inclusion criteria and contacted the first authors to identify any other trial analyses that were published.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (IVDH and NA) independently screened the abstracts of all citations identified by the literature search to see if any met the inclusion criteria. If an abstract was potentially relevant, or it was unclear whether it was relevant or not, we accessed the full‐text paper and read it carefully to see if it the trial met the inclusion criteria. Regarding multiple reports of the same trial, we linked these, collated the data available in the reports, and presented these as one trial. We listed all excluded studies and their reasons for exclusion in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. We constructed a PRISMA study flow diagram to illustrate the study selection process.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (IVDH and NA) independently extracted data from the included trials using a standardized data extraction form that included the following characteristics: citation of authors and year, the type of trial design, population characteristics and trial setting, eligibility criteria, type of intervention, treatment and control group duration and components, all relevant outcomes with measures (scales), time assessment points, percentage lost to follow‐up and results, see Appendix 3.

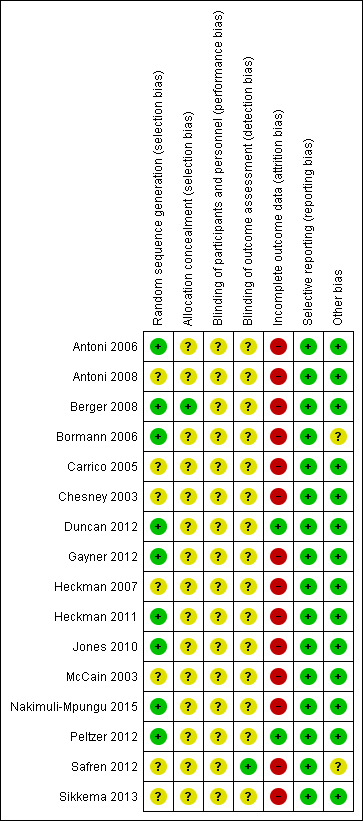

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (IVDH and NA) independently assessed the risk of bias of all trials included in the review using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2008; Higgins 2011). We resolved any discrepancies through discussion and by consulting the third review author, and if necessary we contacted the trial authors for clarification.

We followed the guidance to assess whether the included trials took adequate steps to reduce the risk of bias across the following six domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding (of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors); incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias.

For sequence generation and allocation concealment, we reported the methods that the included trials used. For blinding, we described who was blinded and the blinding method. For incomplete outcome data, we reported the percentage of participants lost to follow‐up. For selective outcome reporting, we stated any discrepancies between the methods used and the results in terms of the outcomes measured or the outcomes reported. For other biases, we described any other trial features that could have affected the trial result (for example, if the trial was stopped early, or how the use of a wait‐list group may bias results because waiting‐list controls might be biased because of resentment at not receiving an intervention, changes in disease state over time, and an absence of engagement in care. However, blinding and randomization will balance out this bias risk.

We categorized our risk of bias judgements as either 'low', 'high', or 'unclear'. Where risk of bias was unclear, we attempted to contact the trial authors for clarification and resolved any differences of opinion through discussion.

Measures of treatment effect

We reported results using mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and used standardized mean difference (SMD) values when we pooled trials using different scales.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis in all trials was the individual (HIV‐positive adult). For complicated designs, such as cluster‐RCTs, we planned to use the cluster as the unit of analysis, and planned to account for clustering by adjusting the analysis to the same level as the individual following the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008; Higgins 2011).

When trials had more than two treatment arms we took care to avoid double counting of participants in the control group.

Dealing with missing data

Our primary analysis was a complete‐case analysis, which included only the participants with data at each time point.

We considered the potential for bias due to missing data in our GRADE evaluation of the certainty of the evidence, by considering the size of losses to follow‐up, and any differential losses between groups.

We contacted trial authors for clarification regarding missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We described clinical heterogeneity between trials by summarizing key characteristics of the trial design, intervention, population, and outcome measures in tables.

We assessed statistical heterogeneity by looking at forest plots to examine the presence of overlapping CIs and using the Chi² test using a P value of 0.10 to determine statistical significance. We quantified heterogeneity using the I² statistic, which describes the percentage of variability in the effect estimates and we applied the standard categorization of heterogeneity to interpret the statistic i.e. low heterogeneity = I² statistic value of 0% to 25%; moderate heterogeneity = I² statistic value of 26% to 50% and high heterogeneity = I² statistic value of greater than 50%.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to use funnel plots to look for evidence of publication bias. However, there were few included trials to facilitate this.

Data synthesis

We summarized and analysed the included trials in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) (Review Manager 2014).

We analysed trials with different underlying psychological theories separately, and stratified the primary analysis by time point: baseline, end of the group session, and longest follow‐up.

When pooling studies was considered appropriate we used a random‐effects approach due to the clinical heterogeneity between trials.

We created a 'Summary of findings' for each comparison including the four main outcomes: depression, anxiety, stress, and coping. For each effect estimate we evaluated our confidence in the effect by considering each of the five GRADE criteria: risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias. When we found sufficient problems to downgrade the overall certainty of the evidence we justified these decisions using footnotes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We explored possible causes of statistical heterogeneity by conducting sub group analyses by: primary focus of the intervention, outcome scale used, the control intervention, and gender. We only performed these subgroup analyses when there were sufficient trials to make it meaningful.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not plan to perform any sensitivity analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

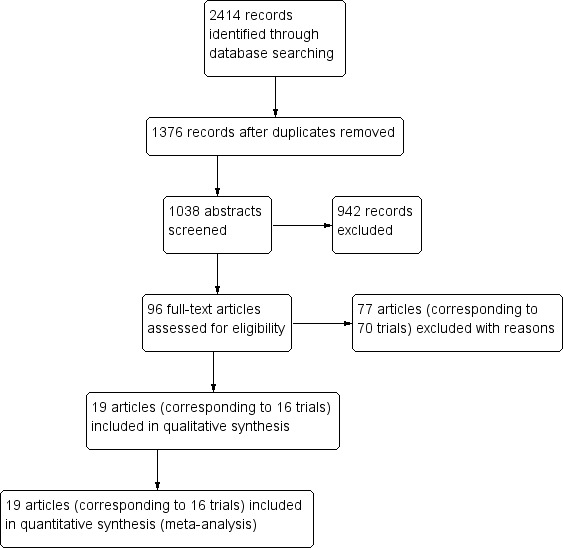

We searched the available literature up to 14 March 2016 and identified 2414 citations from the electronic database searches. After discarding 1376 duplicates, we screened 1038 articles by title and abstract. We selected abstracts that potentially matched our inclusion criteria, and also articles where it was unclear whether or not they fulfilled the inclusion criteria, for full‐text assessment. We excluded 942 articles and identified 96 full‐text articles for further assessment. After full‐text assessment of these articles. we excluded 77 articles. These corresponded to 70 studies after we collated them, which we listed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. Nineteen articles met the inclusion criteria. We collated multiple reports on the same trial, which gave 16 included trials. We have illustrated the study selection process in Figure 2.

2.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

Sixteen randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that included 2520 HIV‐positive adults met the inclusion criteria of this Cochrane Review. Four trials exclusively recruited homosexual men (Chesney 2003; Carrico 2005; Antoni 2006; Gayner 2012), and two trials recruited women only (Antoni 2008; Jones 2010). The remaining trials recruited both men and women, with four specifying they were all on antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Berger 2008; Duncan 2012; Peltzer 2012; Safren 2012), one trial recruited only those with a history of childhood sexual abuse (Sikkema 2013), one recruited injection drug users (Safren 2012), one recruited those over 50 years old (Heckman 2011), and one recruited participants with major depression (Nakimuli‐Mpungu 2015). All trials excluded pregnant women (see Table 3).

1. Description of populations.

| Trial | Country | Age (years) | On antiretroviral therapy (ART) | General population or subgroup | Mood disorders | |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |||||

| Antoni 2006 | USA | 18 to 65 | Yes | Homosexual men | None stated | Current psychosis or panic disorder |

| Antoni 2008 | USA | 18 to 60 | Not stated | Women with evidence of CIN1 | None stated | Current major psychiatric illness |

| Berger 2008 | Switzerland | 18 to 65 | Yes | General population | None stated | Current major psychiatric disorder |

| Carrico 2005 | USA | Not stated | No (recruited largely during the era prior to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART; 1992 to 1997) |

Homosexual men | None stated | Current major psychiatric illness |

| Jones 2010 | USA | > 18 | Not stated | Minority women | None stated | Untreated major psychiatric illness |

| McCain 2003 | USA | > 18 | Yes | General population | None stated | Significant psychiatric illness |

| Safren 2012 | USA | 18 to 65 | Yes | Prior intravenous drug users | Current depressive mood disorder | Untreated or unstable major mental illness |

| Heckman 2007 | USA | Not stated | Not stated | Rural population | No inclusion or exclusion criteria related to psychological functioning were employed | No inclusion or exclusion criteria related to psychological functioning were employed |

| Heckman 2011 | USA | > 50 | Not stated | Individuals over the age of 50 | BDI‐II score is minimum 10 | Exclude severe depression or cognitive impairment |

| Sikkema 2013 | USA | Not stated | Not stated | History of child sexual abuse | Not stated | Not stated |

| Peltzer 2012 | South Africa | > 18 | Yes | Individuals with ART adherence problem/new antiretroviral (ARV) medication users (6 to 24 months of ARV use) | Not stated | Not stated |

| Chesney 2003 | USA | 21 to 60 | No | Homosexual men | Reported depressed mood 10 or higher on CES‐D scale | Major depressive disorder or other psychotic disorders |

| Bormann 2006 | USA | 18 to 65 | Not stated | Adult men and women (50% homosexual) | Not stated | Cognitive impairment of active psychosis |

| Duncan 2012 | USA | Not specified | Yes | Adult men and women who reported distress associated with side effects from ART treatment | Reporting a level of side effect‐related bother for the previous 30 days at or above eight (corresponding to the 40th percentile in another sample) on the side effect and symptom distress scale | Severe cognitive impairment, active psychosis, or active substance abuse |

| Gayner 2012 | Canada | Not specified | Not stated | Homosexual men | None stated | Active current major depression, substance abuse, or significant cognitive deficit |

| Nakimuli‐Mpungu 2015 | Uganda | > 19 | Not stated | Both men and women | People with major depression on Mini Psychiatric Interview Scale | The trial excluded individuals with a severe medical disorder such as pneumonia or active tuberculosis, psychotic symptoms, and hearing or visual impairment. |

Abbreviations: ART: antiretroviral therapy; ARV: antiretroviral.

Twelve trials were conducted in the USA (Chesney 2003; McCain 2003; Carrico 2005; Antoni 2006; Bormann 2006; Heckman 2007; Antoni 2008; Jones 2010; Heckman 2011; Duncan 2012; Safren 2012; Sikkema 2013), Canada (Gayner 2012), and one in Switzerland (Berger 2008), one in Uganda (Nakimuli‐Mpungu 2015) and one in South Africa (Peltzer 2012). Recruitment was from hospitals, clinics, drop‐in centres, or community settings.

Therapy was conducted with groups of four to 15 people every week for up to 12 weeks. All were face‐to‐face interventions except in Heckman 2007 and Heckman 2011 in which they were delivered by telephone. All interventions were delivered by postgraduate trained health, psychology, or social care professionals, except one which used lay health workers (Peltzer 2012). Sessions lasted 90 to 135 minutes, and the period of follow‐up varied from three to 15 months. The control groups ranged from wait‐list, standard care or treatment as usual, information or education only, or a brief form of the intervention (30 minutes or one day).

We subgrouped the interventions by their underlying psychological theory, although all the interventions were multifaceted.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (13 trials): a psychotherapeutic approach that addresses dysfunctional emotions, maladaptive behaviours, and cognitive processes through a number of goal‐oriented, problem‐focused, action‐orientated procedures. The name refers to therapy based upon a combination of basic behavioral and cognitive principles and research. Most therapists working with patients dealing with anxiety and depression use a blend of cognitive and behavioral therapy. Six trials focused particularly on stress management (McCain 2003; Carrico 2005; Antoni 2006; Antoni 2008; Berger 2008; Sikkema 2013), three on coping (Chesney 2003; Heckman 2007; Heckman 2011), one on self‐efficacy (Jones 2010), one on adherence and depression (Safren 2012), one on depression (Nakimuli‐Mpungu 2015), and one on adherence (Peltzer 2012).

Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (three trials): a structured group programme that employs mindfulness meditation to enhance awareness of irrational thoughts and negative affect (Duncan 2012; Gayner 2012), and includes a spirituality approach that involves repeating a mantram‐sacred word or phrase (Bormann 2006).

The trials reported a variety of scales for depression, anxiety, stress, and coping (Table 4; Table 5; Table 6). We pooled these data using standardized mean differences, before presenting a subgroup analysis using the same assessment scale.

2. Depression scales reported by trials.

| Scale | Number of items (depression) | Scale for each item1 | Total score (depression) | Interpretation | Description2 | Trials |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI/BDI‐II) (Beck 1988) | 21 | 0 (I do not) to 3 (I do and I can't stand it) | 0 to 63 | 0 to 13: minimal 14 to 19: mild 20 to 28: moderate 29 to 63: severe |

Participants rate the intensity of depressive feelings over the preceding 1 or 2 weeks | Carrico 2005; Antoni 2006; Heckman 2007; Jones 2010; Duncan 2012; Peltzer 2012; Safren 2012 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond 1983) | 7 | 0 (not at all) to 3 (very often) | 0 to 21 | 0 to 7: normal 8 to 10: borderline 11 to 21: depression |

Participants rate the frequency of depressive thoughts and behaviours over the preceding 4 weeks | Berger 2008; Gayner 2012 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (Yesavage 1982) | 30 | 0 (no) to 1 (yes) | 0 to 30 | 0 to 9: normal 10 to 19: mild 20 to 30: severe |

Participants report the presence or absence of depressive thoughts and behaviours | Heckman 2011 |

| The Centre for Epidemiological Studies‐Depression Scale (CES‐D) (Radloff 1977) | 20 | 0 (not at all) to 3 (all of the time) | 0 to 60 | 0 to 15: normal 16 to 60: depression Cut off is 16 |

Participants rate the frequency of depressive symptoms, feelings, and behaviours over the past week | Chesney 2003; Bormann 2006 |

| Self Reported Questionnaire (SRQ‐20) (Sheehan 1997) | 20 | 0 (no) to 1 (yes) | 0 to 20 | 0 to 5: normal 6 to 20: depression |

Participants report the presence or absence of depressive symptoms, thoughts, and behaviours | Nakimuli‐Mpungu 2015 |

| Profile of Mood States (POMS) Depression (D) (McNair 1971) |

15 | 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) | 0 to 60 | Higher scores indicate worsening depression | Participants rate adjectives describing their mood states over the past week | Antoni 20063 |

| Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979) | 10 | 0 (normal) to 6 (severe) | 0 to 60 | 0 to 6: normal 7 to 19: mild 20 to 34: moderate > 34: severe |

A physician assessment based on a clinical interview covering depression symptoms | Safren 20123 |

1The exact responses may vary between items. 2The descriptions in this table represent our best understanding of the scale derived from the description provided by the included studies and other information available through Internet searches. The exact scale used in the trials may have differed. 3These papers presented more than one measure of depression. In the main analysis only Beck Depression Inventory was presented. The additional measures are presented in Analysis 1.2 and had similar findings.

3. Anxiety scales reported by the included trials.

| Scale | Number of items (anxiety) | Score for each item1 | Total score (anxiety) | Interpretation | Description2 | Trials |

| Profile of Mood States

(POMS) Anxiety (A) (McNair 1971) |

9 | 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) | 0 to 36 | Higher scores indicate worsening anxiety | Participants rate adjectives describing their mood states over the past week | Antoni 2006 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond 1983) | 7 | 0 (not at all) to 3 (very often) | 0 to 21 | 0 to 7: normal 8 to 10: borderline 11 to 21: anxiety |

Participants rate the frequency of anxiety feelings and behaviours over the preceding 4 weeks | Berger 2008; Gayner 2012 |

| State Trait‐Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger 2010) | 20 | 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much so) | 20 to 80 | A cut point of 39 to 40 has been suggested to detect clinically significant symptoms | Participants rate the frequency and intensity of anxiety feelings at this moment (state), and more generally (trait) | Chesney 2003; Bormann 2006; Jones 2010 |

1The exact responses may vary between items. 2The descriptions in this table represent our best understanding of the scale derived from the description provided by the included studies and other information available through Internet searches. The exact scale used in the trials may have differed.

4. Stress scales reported by trials.

| Scale | Number of items | Score for each item1 | Total score | Interpretation | Description2 | Trials |

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen 1983) | 10 | 0 (never) to 4 (very often) | 0 to 40 | Higher scores indicate higher perceived stress | Participants rate the frequency of stress related thoughts and feelings in the preceding 4 weeks | Chesney 2003; Bormann 2006; Duncan 2012 |

| Dealing with Illness Scale ‐ Stress subscale (DIS) (McCain 1992) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Higher scores reflect higher stress | Participants rate the desirability or undesirability and personal impact of experienced events | McCain 2003 |

| HIV‐Related Life‐Stress Scale (Sikkema 2000) | 19 | 1 (not a problem) to 5 (most serious problem) | 1 to 5 | Higher scores indicate higher stress | Participants rate the severity of each HIV‐related potential stressor | Heckman 2007 |

| Life Experiences Survey (LES) (Sarason 1978) | 10 | 0 (not at all stressed) to 3 (extremely stressful) | 0 to 3 | 0 = not at all stressed 1 = mildly stressed 2 = moderately stressed 3 = extremely stressed |

Participants rate the extent to which an event commonly experienced by HIV‐positive women had been stressful | Antoni 2008 (a 10‐item abbreviated version) |

| Impact of Event Scale (IES) (Horowitz 1979) |

15 | 0 (not at all) to 4 (often) | 0 to 75 | Higher scores indicate higher impact | Participants rate the frequency of intrusive or avoidant thoughts and experiences over the preceding 7 to 28 days (the authors describe this scale as measuring 'psychological distress' or 'traumatic stress') | McCain 2003; Gayner 2012; Sikkema 2013 |

1The exact responses may vary between items. 2The descriptions in this table represent our best understanding of the scale derived from the description provided by the included studies and other information available through Internet searches. The exact scale used in the trials may have differed.

Excluded studies

We excluded a total of 70 trials (77 articles) after full‐text assessment and listed the reasons for exclusion in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. Some studies were not RCTs or did not report on RCT data, and most studies did not include group interventions; this was not apparent when we only assessed the abstract. Other trials did not have at least a three‐month post‐intervention follow‐up assessment. Safren 2009 invited the control to cross‐over to the intervention after three months but had no post‐intervention three‐month follow‐up. For example, we excluded Wyatt 2004 as we did not receive any response from the study author about what data they included in the post‐intervention period, that is whether the data presented in this trial was the three‐month or six‐month follow‐up data; it remains unclear. Latkin 2003 and Yu 2014 did not have HIV‐positive populations. Six trials did not measure our specified outcomes. One trial, Laperriere 2005, presented a subgroup analysis from a larger trial. Prado 2012 had a sample of adolescents and not adults. Sacks 2011 did not report on effects for the group intervention.

We excluded seven trials conducted in Africa: Papas 2011 in Western Kenya measured reductions in alcohol use in people on antiretroviral (ARV) treatment using a CBT intervention so did not include a specified outcomes, Olley 2006 in Nigeria measured psychological distress, risky sexual behaviour, and self‐disclosure of HIV using an individual psychoeducation intervention rather than a group intervention, Mundell 2011 measured rates of disclosure and active and avoidant coping in pregnant and recently diagnosed HIV‐positive women in South Africa participating in structured up support groups, but this was not an RCT. Petersen 2014's trial on a group‐based counselling intervention for depression in South Africa did not have a three‐month follow‐up postintervention. Petersen 2014 also had a very small sample size. Kunutsor 2011's trial was based in Uganda but was a treatment supporter intervention and not a group intervention, and Jones 2005's trial among HIV positive women in Zambia did not have a control group. Kaaya 2013's trial in Tanzania measured prenatal HIV disclosure and depression, however we excluded it because there was no three‐month post‐intervention follow‐up.

Risk of bias in included studies

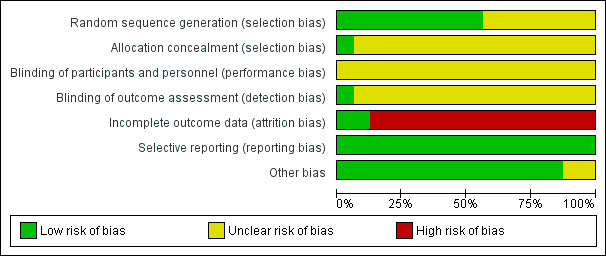

For a summary of the 'Risk of bias' assessments see Figure 3 and Figure 4.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included trial

4.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all included trials

Allocation

We only included 'randomized' trials. However, only Berger 2008 provided enough detail of the methods to be considered at low risk of selection bias. All other included trials were at unclear risk of selection bias.

Blinding

True blinding of participants to the types of interventions evaluated in this review is rarely possible. Trial authors did not describe blinding sufficiently. However, it is possible to blind those conducting the analysis but only one trial described the methods to achieve this and we judged it to be at low risk of detection bias (Safren 2012). All other trials were at unclear risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Fourteen trials reported high levels of loss to follow‐up in at least one treatment arm over the duration of the trial (greater than 20%), or differential losses between groups, which had the potential to bias the results. Consequently we only judged two included trials to be at low risk of attrition bias (Duncan 2012; Peltzer 2012).

Selective reporting

We found no evidence of selective reporting and we considered all included trials as at low risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Bormann 2006 and Safren 2012 noted some imbalances in potential confounders between the intervention and control groups at baseline. We judged these trials to be at unclear risk of bias. All other included trials were at low risk of other sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. 'Summary of findings' table 1.

| Group therapy (cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)) versus control for improving psychological well‐being in adults living with HIV | |||||

| Patient or population: adults living with HIV Settings: any setting Intervention: group therapy based on CBT | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI)* | Number of participants (trials) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Control | Group therapy (CBT) | ||||

| Depression score Follow‐up: 6 to 15 months | The mean scores in the control groups at the end of follow‐up ranged from normal to moderately depressed | The mean score in the intervention groups was: 0.26 standard deviations (SDs) lower (0.42 lower to 0.10 lower) | 1139 (10 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

low1,2,3,4 due to indirectness and risk of bias |

There may be a small benefit which lasts for up to 15 months |

|

Anxiety score Follow‐up: 6 to 15 months |

The mean scores in the control groups at the end of follow‐up ranged from normal to clinically anxious | The mean score in the intervention groups was: 0.12 SDs lower (0.31 lower to 0.06 higher) | 471 (4 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

low2,5,6,7 due to indirectness and risk of bias |

There may be little or no effect on mean anxiety scores |

|

Stress score Follow‐up: 6 to 15 months |

The mean score in the control groups at the end of follow‐up were variable | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.04 SDs lower (0.23 lower to 0.15 higher) | 507 (5 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

low2,5,6,7 due to indirectness and risk of bias |

There may be little or no effect on mean stress scores |

|

Coping score Follow‐up: 6 to 15 months |

The mean score in the control groups at the end of follow‐up were variable | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.04 SDs higher (0.11 lower to 0.19 higher) | 697 (5 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

low2,5,6,7 due to indirectness and risk of bias |

There may be little or no effect on mean coping scores |

| Studies used a variety of different scales to measure depression, anxiety and stress. Consequently, trials were pooled using a standardized mean difference. Examples of how large this effect would be on standardized measurement scales are given in the review main text and abstract. Abbreviations: CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1Downgraded by 1 for serious risk of bias: most of the trials did not adequately described a method of allocation concealment, and so trials are at unclear or high risk of selection bias. Loss of follow‐up was generally more than 20% and attrition bias may be present. 2No serious inconsistency: statistical heterogeneity between trials was low. 3Downgraded by 1 for serious indirectness: most trials were from high‐income settings (USA, Canada, and Switzerland), and in five trials the mean depression score at baseline was in the normal (not depressed) range. Only five trials evaluated groups with measurable levels of depression and in these trials the effects were inconsistent. 4No serious imprecision: the effect is small but statistically significant. The clinical significance is unclear. 5Downgraded by 1 for serious risk of bias: most of the trials did not adequately described methods to prevent selection bias. 6Downgraded by 1 for serious indirectness: although effects were not seen in these few trials, we cannot exclude the possibility of effects in some populations. 7No serious imprecision: the effect size is close to zero with a narrow 95% CI.

Summary of findings 2. 'Summary of findings' table 2.

| Group therapy (mindfulness) compared to control for improving psychological well‐being in adults living with HIV | |||||

| Patient or population: adults living with HIV Settings: any setting Intervention: group therapy based on mindfulness | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Number of participants (trials) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Control | Group therapy (Mindfulness) | ||||

|

Depression score Follow‐up: 4 to 6 months |

The mean scores in the control groups at the end of follow‐up were in the range of normal to mild depression | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.23 standard deviations (SDs) lower (0.49 lower to 0.03 higher) | 233 (3 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝

very low1,2,3,4 due to risk of bias, indirectness, and imprecision |

We don't know if there is a benefit on depression scores |

|

Anxiety score Follow‐up: 4 to 6 months |

The mean scores in the control group at the end of follow‐up were in the range of normal to mild anxiety | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.16 SDs lower (0.47 lower to 0.15 higher) | 162 (2 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝

very low1,3,4 due to risk of bias, indirectness, and imprecision |

We don't know if there is an effect on mean anxiety scores |

|

Stress score Follow‐up: 4 to 6 months |

The mean scores in the control group at the end of follow‐up were in the range of mild stress | The mean score in the intervention groups was 2.02 points lower (4.23 lower to 0.19 higher) | 137 (2 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝

very low1,3,4 due to risk of bias, indirectness, and imprecision |

We don't know if there is an effect on mean stress scores |

|

Coping score Follow‐up: no coping was measured by mindfulness intervention trials |

— | — | 0 (0 trials) |

— | — |

| Studies used a variety of different scales to measure depression, anxiety and stress. Consequently, trials were pooled using a standardized mean difference. Examples of how large this effect would be on standardized measurement scales are given in the review main text and abstract. Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; SD: standard deviation. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1Downgraded by 1 for serious risk of bias: none of the trials adequately described a method of allocation concealment, and so trials are at unclear or high risk of selection bias. Loss of follow‐up was generally more than 20% and attrition bias may be present. 2No serious inconsistency: statistical heterogeneity between trials was low. 3Downgraded by 1 for serious indirectness: these three trials were conducted in the USA and Canada in people with scores in the range of mild to moderate depression. The results are not easily generalized to other settings or populations. 4Downgraded by 1 for serious imprecision: the 95% CI are wide and includes both potentially important effects and no effect.

See 'Summary of findings' table 1 (Table 1) and 'Summary of findings' table 2 (Table 2). We have presented the findings by intervention type.

Comparison 1: Group therapy (CBT) versus control

See 'Summary of findings' table 1 (Table 1).

Thirteen trials evaluated group therapy sessions based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) techniques. Ten trials were delivered face‐to‐face (Chesney 2003; McCain 2003; Carrico 2005; Antoni 2006; Antoni 2008; Berger 2008; Jones 2010; Peltzer 2012; Nakimuli‐Mpungu 2015) and two were delivered by telephone (Heckman 2007; Heckman 2011). The primary focus of CBT was stress reduction or coping (nine trials), self‐efficacy (one trial), depression (one trial), adherence (one trial), and adherence and depression (one trial). Eight trials described additional relaxation components such as progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) or meditation, four explicitly described methods to facilitate peer/group support, and six described specific educational components. Most sessions lasted between 50 and 135 minutes, were conducted weekly for between eight and 12 weeks, and included between four and 12 participants (Table 7).

5. Description of cognitive‐behavioural interventions.

| Trial | Group size | Session duration (mins) | Session frequency | Intervention | Comparison | |||||

| Underlying theory | Primary focus | Components | ||||||||

| Skills training | Relaxation techniques | Peer support2 | Education2 | |||||||

| McCain 2003 | 6 to 10 | 90 | Weekly for 8 weeks | Cognitive‐behavioural | Stress management | Cognitive restructuring coping skills |

Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR)/meditation/yoga | Not described | Not described | No intervention ‐ waitlist group |

| Carrico 2005 | 4 to 9 | 135 | Weekly for 10 weeks | Cognitive‐behavioural | Stress management | Cognitive restructuring, coping skills, anger management, use of social network | PMR/meditation | Not described | Not described | No intervention ‐ waitlist group |

| Antoni 2006 | 4 to 9 | 135 | Weekly for 10 weeks | Cognitive‐behavioural | Stress management | Cognitive restructuring, coping skills | PMR/meditation | Not described | Medication adherence | 1 hour medication adherence training (MAT) |

| Antoni 2008 | 4 to 6 | 135 | Weekly for 10 weeks | Cognitive‐behavioural | Stress management | Cognitive restructuring, coping skills, assertiveness, anger management, use of social network | PMR/meditation | Not described | Not described | Condensed 1 day CBSM workshop |

| Berger 2008 | 4 to 10 | 120 | Weekly for 12 weeks | Cognitive‐behavioural | Stress management | Cognitive strategies | PMR | Group dynamic exercises | HIV related topics | No intervention ‐ 30‐minute health check by physician |

| Sikkema 2013 | 10 | 90 | Weekly for 15 weeks | Cognitive theory of stress and coping | Traumatic stress | Cognitive appraisal, coping skills | 'relaxation strategies' | Not described | Not described | Attention control ‐ HIV standard therapeutic support group |

| Chesney 2003 | 8 to 10 | 90 | Weekly for 10 weeks | Cognitive theory of stress and coping | Coping/stress | Appraising stressors, coping skills, stress management | 'relaxation guidance' | Skill building group exercises | Psychoeducation around models of coping | No intervention ‐ waitlist group |

| Heckman 2007 | 6 to 8 | 90 | Weekly for 8 weeks | Transactional model of stress and coping | Coping | Appraising stressors, coping skills, use of personal and social resources | No | Not described | Not described | No intervention ‐ usual care |

| Heckman 2011 | 6 to 810 | 90 | Weekly for 12 weeks | Transactional model of stress and coping | Coping | Appraising stressors, coping skills, use of personal and social resources | No | Not described | Not described | No intervention ‐ individual therapy upon request (ITUR) |

| Jones 2010 | Not stated | 120 | Weekly for 10 weeks | Cognitive‐behavioural | Self‐efficacy | Cognitive restructuring, stress management, coping skills, anger management, use of social network | 'relaxation' | Expressive supportive therapy | HIV/mental health topics | Attention control group |

| Nakimuli‐Mpungu 2015 | 10 to 12 | 120 to 180 | Weekly for 8 weeks | Cognitive‐behavioural, social learning theory, and the sustainable livelihoods framework | Depression | Coping skills, problem solving skills, dealing with stigma, income‐generation | Not described | Group rituals | Triggers, symptoms, and treatment of depression. | Active control group |

| Safren 2012 | Not stated | 50 mins | Weekly for 9 weeks | Cognitive‐behavioural | Adherence/ depression | Cognitive restructuring, problem solving, activity scheduling | PMR/diaphragmatic breathing | Not described | Adherence, depression | Enhanced treatment as usual (ETAU) |

| Peltzer 2012 | 10 | 60 mins | Monthly for 3 months | Cognitive‐behavioural | Adherence | Not specifically described | Not described | Buddy system to increase social support | Knowledge of HIV and HIV‐related medication | No intervention ‐ standard care |

Abbreviations: HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PMR: progressive muscle relaxation. 1The interventions used in McCain 2003, Carrico 2005, Antoni 2006, Antoni 2008, Berger 2008, and Jones 2010 appear to be very similar. 2Although peer support and education were often not well described in these papers, these aspects are inevitable with group therapy and are likely to be an important factor in any observed effect regardless of the therapeutic theory.

Fourteen trials were from high‐income settings (USA, Canada, and Switzerland). Two trials were from low‐ or middle‐income settings: South Africa (Peltzer 2012), and Uganda (Nakimuli‐Mpungu 2015). Five trials were conducted among general populations, three trials with homosexual men, one trial with women from minority groups, one trial with women with an abnormal cervical smear, one trial among prior intravenous drug users, one trial among people with a history of being abused, and one trial among people with adherence problems (see Table 3).

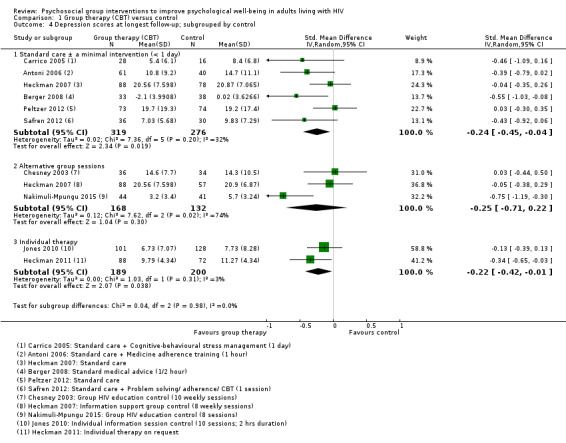

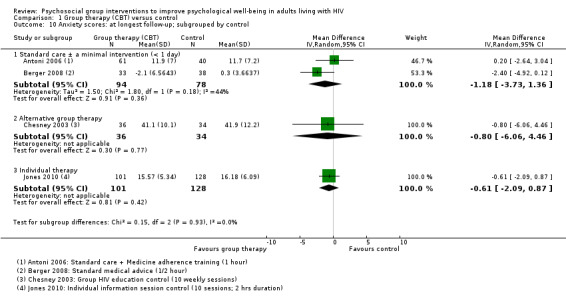

Depression scores

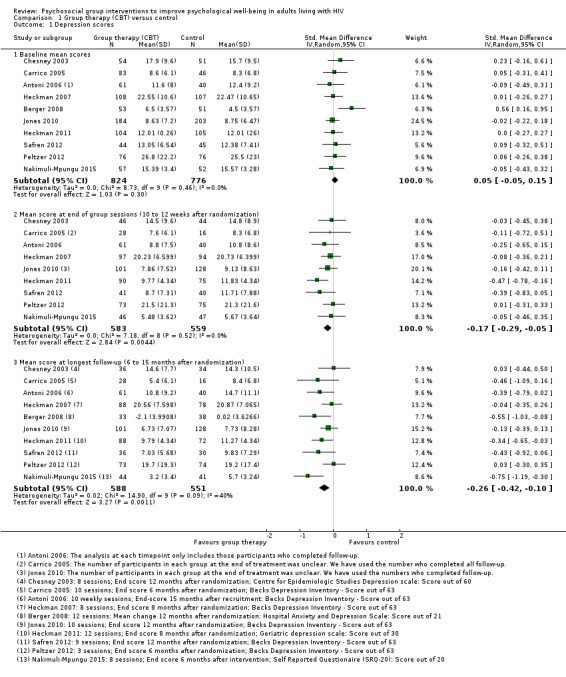

Overall, there was a small reduction in mean depression scores at the end of the group sessions (standardized mean difference (SMD) −0.17, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.29 to −0.05; 1142 participants, 9 trials; low certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1), and this appeared to be maintained for up to 15 months after randomization (SMD −0.26, 95% CI −0.42 to −0.10; 1139 participants, 10 trials, low certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group therapy (CBT) versus control, Outcome 1 Depression scores.

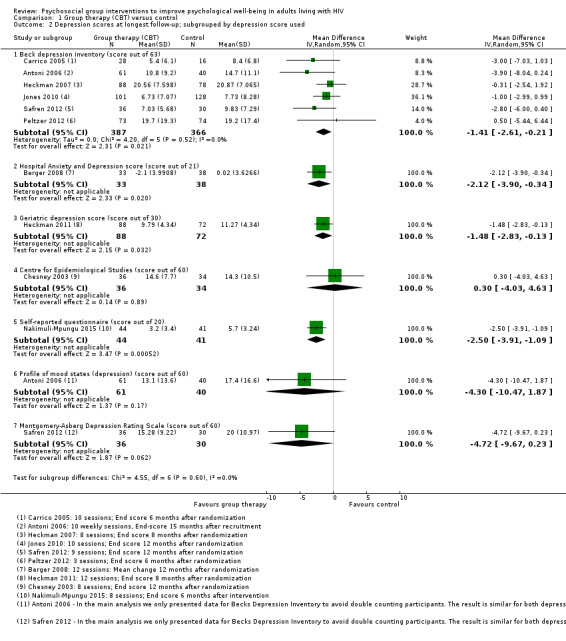

The most commonly used depression score was Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (used by six trials), which scores depression out of 63. The overall effect was a reduction of around 1.4 points (mean difference (MD) −1.41, 95% CI −2.61 to −0.21; 753 participants, 6 trials, Analysis 1.2). See Table 4 for a description of the different depression scores that the included trials used.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group therapy (CBT) versus control, Outcome 2 Depression scores at longest follow‐up; subgrouped by depression score used.

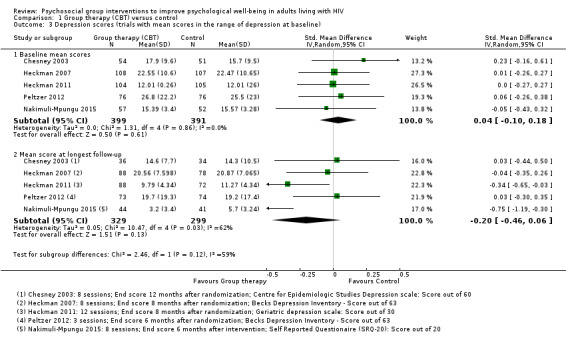

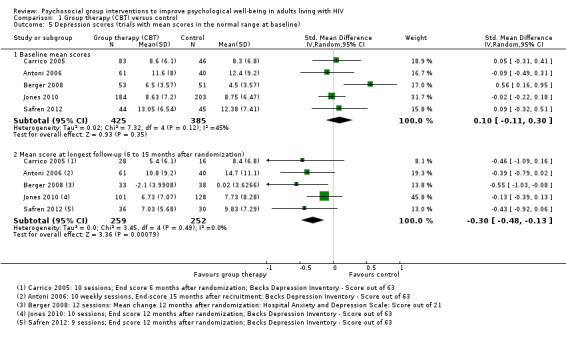

Mean depression scores at baseline were in the depressive range in five trials. Over the duration of these trials, there was a modest improvement in mean score in both the intervention and control groups, but only two trials showed increased benefit with the intervention (Analysis 1.3). In the remaining five trials mean depression scores were in the normal range at baseline, and there was a small but consistent reduction in mean score with the intervention (Analysis 1.5).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group therapy (CBT) versus control, Outcome 3 Depression scores (trials with mean scores in the range of depression at baseline).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group therapy (CBT) versus control, Outcome 5 Depression scores (trials with mean scores in the normal range at baseline).

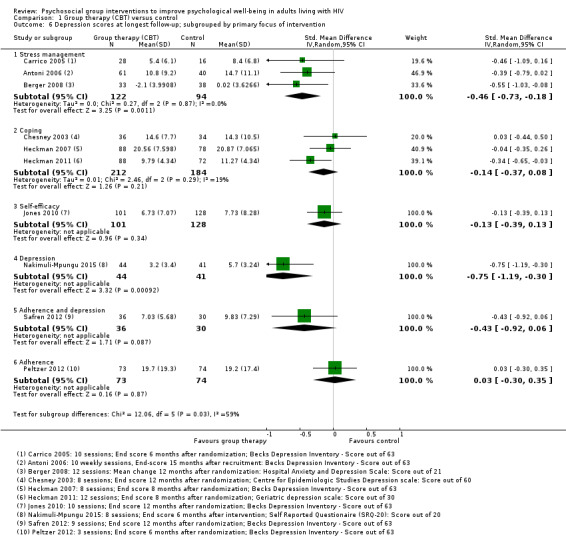

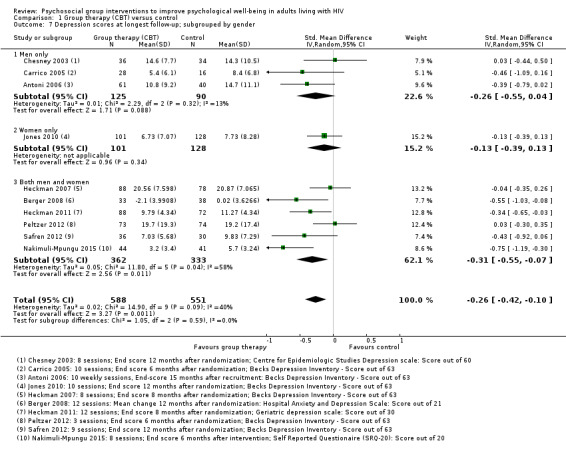

We conducted additional subgrouping by the type of control group used (Analysis 1.4), the primary focus of the intervention (Analysis 1.6), and gender (Analysis 1.7). The most consistent effects on depression were from three trials that focused on stress management interventions (SMD −0.46, 95% CI −0.73 to −0.18; 216 participants, 3 trials).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group therapy (CBT) versus control, Outcome 4 Depression scores at longest follow‐up; subgrouped by control.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group therapy (CBT) versus control, Outcome 6 Depression scores at longest follow‐up; subgrouped by primary focus of intervention.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group therapy (CBT) versus control, Outcome 7 Depression scores at longest follow‐up; subgrouped by gender.

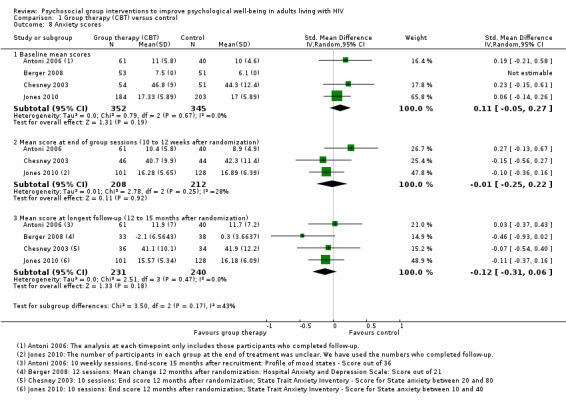

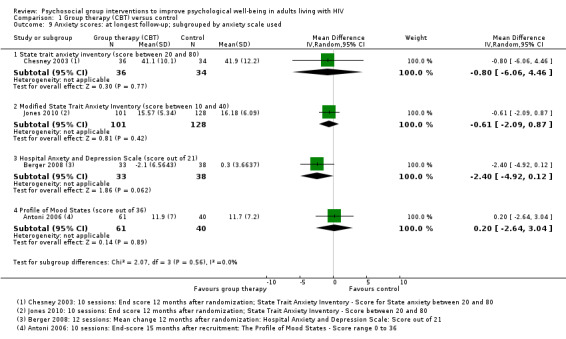

Anxiety scores

Four trials assessed measures of anxiety, and overall there was no effect apparent at the end of the group sessions (SMD −0.01, 95% CI −0.25 to 0.22; 420 participants, 3 trials, low certainty evidence), or at 12 to 15 months after randomization (SMD −0.12, 95% CI −0.31 to 0.06; 471 participants, 4 trials, low certainty evidence; Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group therapy (CBT) versus control, Outcome 8 Anxiety scores.

All four trials used different anxiety scales, and only one trial (using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) reported a statistically significant effect (see Table 5 and Analysis 1.9). This study was conducted in Switzerland among the general population, and baseline and end anxiety scores were in the normal range (Berger 2008). Only the participants recruited by Chesney 2003 appeared to have substantial anxiety at baseline, and although there was a small improvement in both groups over the course of the trial, there were no differences between groups at any time point.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group therapy (CBT) versus control, Outcome 9 Anxiety scores: at longest follow‐up; subgrouped by anxiety scale used.

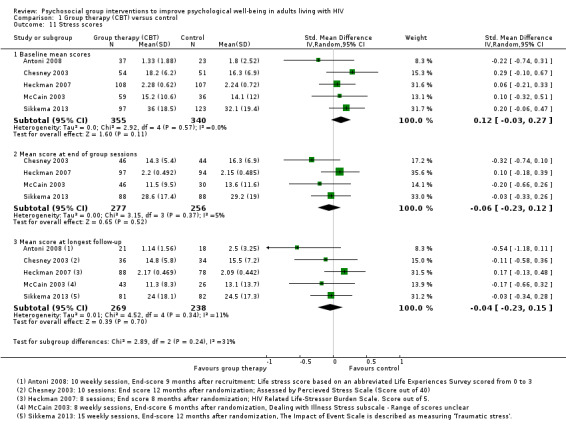

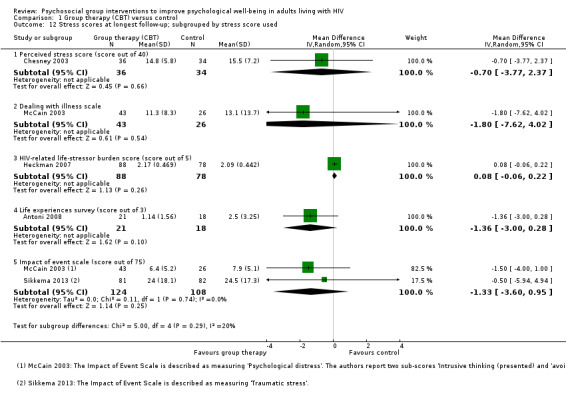

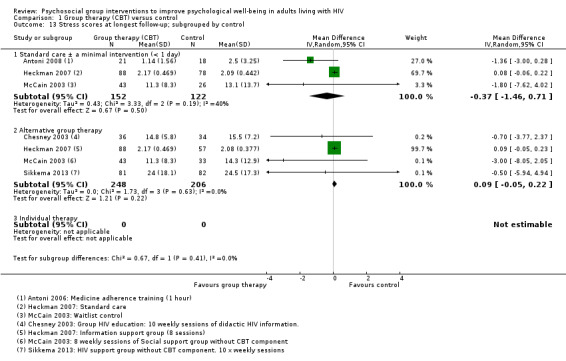

Stress scores

Five trials assessed measures of stress, and overall there was no effect apparent at the end of group sessions (SMD −0.06, 95% CI −0.23 to 0.12; four trials, 533 participants, low certainty evidence, Analysis 1.11), or at the end of follow‐up (SMD −0.04, 95% CI −0.23 to 0.15; five trials, 507 participants, low certainty evidence, Analysis 1.11). Only Antoni 2008, which was conducted among HIV‐positive women with a recent abnormal cervical smear, found a statistically significant effect at any time point. For a description of the stress scores used see Table 6 and Analysis 1.12.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group therapy (CBT) versus control, Outcome 11 Stress scores.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group therapy (CBT) versus control, Outcome 12 Stress scores at longest follow‐up; subgrouped by stress score used.

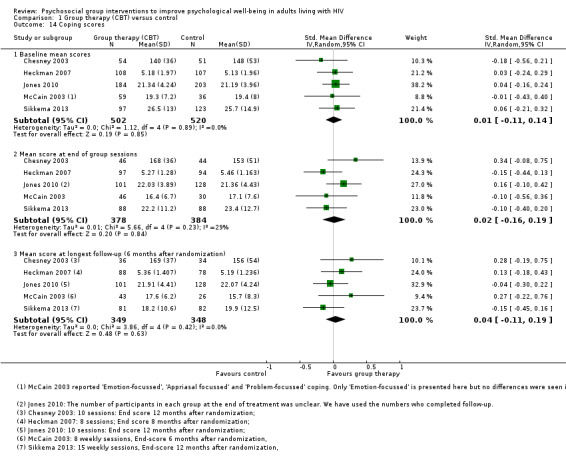

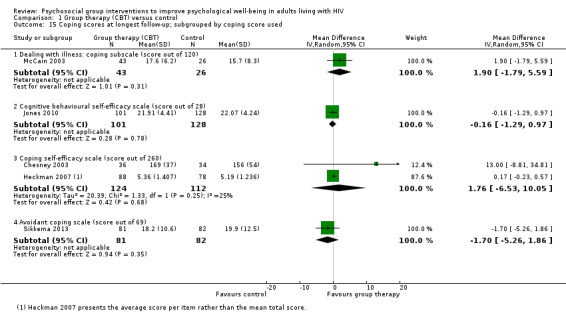

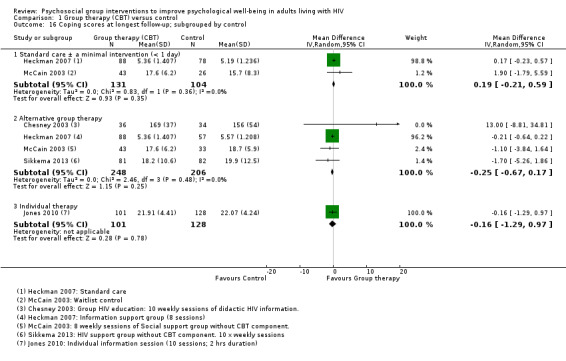

Coping scores

Five trials reported some measure of coping with no effects seen at the end of group therapy (SMD 0.02, 95% CI −0.16 to 0.19; 762 participants, 5 trials; low certainty evidence, Analysis 1.14), or at the end of follow‐up (SMD 0.04, 95% CI −0.11 to 0.19; 697 participants, 5 trials; low certainty evidence; Analysis 1.14). In all measures of coping, higher scores reflected increased coping (see Table 8 and Analysis 1.15).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group therapy (CBT) versus control, Outcome 14 Coping scores.

6. Coping scales reported by trials.

| Scale | Number of items | Score for each item1 | Total score | Interpretation | Description2 | Trials |

| Coping Self‐Efficacy Scale (CSES) (Chesney 2006) | 26 | 0 (cannot do at all) to 10 (certain can do) | 0 to 260 | Higher scores indicate better coping skills | Participants rate the extent to which they believe they could perform behaviours important to adaptive coping | Chesney 2003; Heckman 2007 |

| Cognitive Behavioral Self Efficacy (CB‐SE) (Ironson 1987) | 7 | 0 (not at all) to 4 (all of the time) | 0 to 28 | Higher scores indicate higher self‐efficacy | Participants rate their certainty that they could perform certain skills related to AIDS, and antiretroviral medication adherence | Jones 2010 |

| Dealing with Illness Scale ‐ coping subscale (DIS) (McCain 1992) | 40 | 0 (never used) to 3 (regularly used) | 0 to 120 | Higher scores reflect more frequent use of the various coping strategies. | The DIS is a 40‐item coping subscale modelled on the Revised Ways of Coping Checklist. Participants rate the frequency that thoughts or behaviours have been used to deal with problems and stresses over the past month. | McCain 2003 |

| 'Avoidant Coping Scale' Created from 23 items taken from 'The ways of Coping Questionnaire' and 'the Coping with AIDS Scale' (Sikkema 2013) |

23 | 0 (not at all) to 3 (used a great deal) | 0 to 69 | Higher scores reflect more frequent use of coping strategies | Participants rate how often they have used avoidant strategies for coping | Sikkema 2013 |

1The exact responses may vary between items. 2The descriptions in this table represent our best understanding of the scale derived from the description provided by the included studies and other information available through Internet searches. The exact scale used in the trials may have differed.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group therapy (CBT) versus control, Outcome 15 Coping scores at longest follow‐up; subgrouped by coping score used.

Comparison 2: Group therapy (mindfulness) versus control

Three trials evaluated face‐to‐face group therapy sessions based on mindfulness stress reduction (Bormann 2006; Duncan 2012; Gayner 2012). The interventions included mindfulness meditation, with one intervention including mantram repetition and one described additional educational components. Group sessions lasted between 135 and 180 minutes, and were conducted weekly for eight to 10 weeks, plus one day retreat, The group size was eight to 18 participants across trials (see Table 9).

7. Description of mindfulness interventions.

| Trial | Group size | Session duration (mins) | Session frequency | Intervention | Comparison | |||

| Primary focus | Secondary components | |||||||

| Relaxation techniques | Peer support | Education | ||||||

| Duncan 2012 | Not stated | 150 to 180 | Weekly for 8 weeks plus 1 day retreat | Mindfulness‐stress reduction | Mindfulness meditation | Not described | Stress physiology and reactivity | No intervention ‐ waitlist group |

| Gayner 2012 | 14 to 18 | 180 | Weekly for 8 weeks plus 1 day retreat | Mindfulness‐stress reduction | Mindfulness meditation | Not described | Not described | No intervention ‐ treatment as usual (TAU) group offered at end of intervention |

| Bormann 2006 | 8 to 15 | 90 | Weekly for 5 weeks, then 4 automated phone calls, then a final session in week 10 | Mindfulness‐stress reduction | Mantram repetition | Not described | Not described | Attention control |

All trials were conducted in high‐income settings. One trial was conducted among homosexual men in Canada (Gayner 2012), one trial was among men and women experiencing some side effects or distress in the USA (Duncan 2012), and the other included trial was among men and women (50%) who were homosexual (Bormann 2006) (see Table 3).

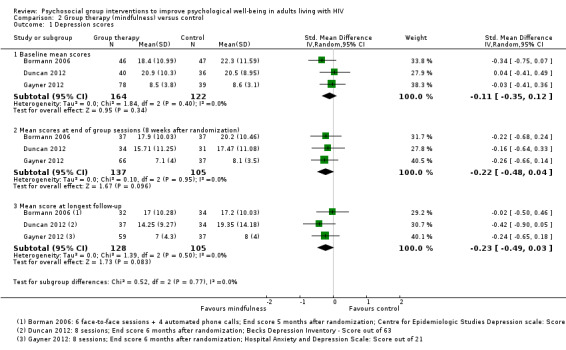

Depression scores

Individually, none of these trials reported statistically significant effects on mean depression scores. The pooled effect suggests a modest reduction in mean scores at the end of the group sessions (SMD −0.22, 95% CI −0.48 to 0.04; 242 participants, 3 trials; very low certainty evidence, Analysis 2.1), and at six months postrandomization (SMD −0.23, 95% CI −0.49 to 0.03; 233 participants, 3 trials;very low certainty evidence; Analysis 2.1), but the 95% CIs were wide and included no effect.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Group therapy (mindfulness) versus control, Outcome 1 Depression scores.

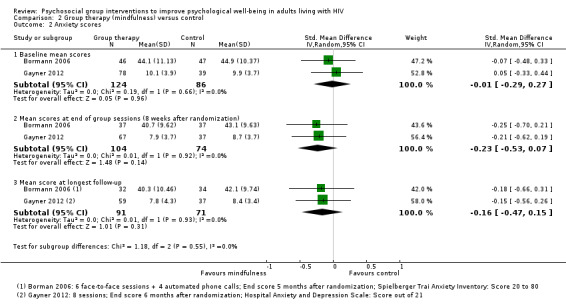

Anxiety scores

Bormann 2006 and Gayner 2012 measured anxiety scores using different measurement scales. There were no statistically significant differences in the mean scores at the end of the group sessions (SMD −0.23, 95% CI −0.53 to 0.07; 178 participants, 2 trials, very low certainty evidence; Analysis 2.2), or at six months (SMD −0.16, 95% CI −0.47 to 0.15; 162 participants, 2 trials, very low certainty evidence; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Group therapy (mindfulness) versus control, Outcome 2 Anxiety scores.

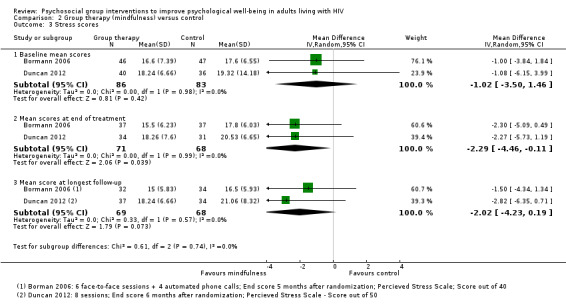

Stress scores

Bormann 2006 and Duncan 2012 measured stress scores using the perceived stress score, A small statistically significant difference was present at the end of group sessions (MD −2.29, 95% CI −4.46 to −0.11; 139 participants, 2 trials; very low certainty evidence), but not at six months postrandomization (MD −2.02, 95% CI −4.23 to 0.19; 137 participants, 2 trials, very low certainty evidence; Analysis 2.3). The effect size was around 2 points on a 40‐point scale.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Group therapy (mindfulness) versus control, Outcome 3 Stress scores.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Group‐based psychosocial interventions based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) may have a small effect on measures of depression, and this effect may last for up to 15 months after participation in the group sessions (low certainty evidence). Most trials used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) which has a maximum score of 63, and the mean score in the intervention groups was around 1.4 points lower at the end of follow‐up. This small benefit was consistent across five trials where participants had a mean depression score in the normal range at baseline, but trials where the mean score was in the depression range at baseline effects were less consistent. Fewer trials reported measures of anxiety (low certainty evidence), stress (low certainty evidence), and coping (low certainty evidence), and there was no clear evidence of effects.

Group‐based interventions based on mindfulness have not demonstrated effects on measures of depression (very low certainty evidence), anxiety (very low certainty evidence), or stress (very low certainty evidence).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Most of the trial interventions were based on cognitive‐behavioural approaches, which were delivered in similar ways (with similar group sizes, similar trained facilitators, and similar numbers of sessions). Most included trials were conducted in high‐income settings (USA, Canada, and Switzerland). Two trials of CBT were conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries, which is where the prevalence of HIV is highest; over 95% of HIV infections are in low‐ and middle‐income countries, two‐thirds of them in sub‐Saharan Africa (Boyle 2016). One trial was conducted among an urban population in Uganda and measures of depression improved significantly in both the intervention and control groups over the course of the study (greater than 10 points on a 20‐point scale) with only small differences between groups (2.5 points). The small effects in the Uganda trial are unlikely to be cost‐effective where resources and trained staff are scarce. The trial conducted among depressed adults on ART in South Africa showed no effects between the two groups for depression.

One of the main aims of this Cochrane Review was to evaluate whether effects seen at the end of group sessions persisted, or were lost, and our findings do seem to suggest that improvements at the end of group session are sustained for up to 15 months. However, as over half the included trials had mean scores at baseline within the normal range (not depressed), the clinical significance of this effect is unclear. In trials that did contain people with measurable depression the effects were inconsistent and there were too few trials to explore why some interventions seemed to have a benefit and some did not.

The included trials used a variety of measurement scales to assess each outcome which made pooling of studies and comparison across population groups difficult.

Quality of the evidence

We rated the certainty of the evidence for a small effect on measures of depression with CBT group therapy as 'low' meaning we can only have low confidence in the observed effect. We downgraded the evidence from high to low due to 'risk of bias': as most studies were at unclear risk of selection bias and high risk of attrition bias, and due to 'indirectness' of the evidence (with most trials being from high income settings), and the difficulty in generalising the findings to other settings and population groups. We also rated the evidence of no effect on anxiety, stress, and coping as 'low' for the same reasons.

For mindfulness‐based group interventions, we rated all outcomes as 'very low' meaning we are very uncertain about the observed effect. We downgraded the evidence for 'risk of bias' due to deficiencies in the study methods, 'indirectness' due to the difficulty generalising the findings to other populations and settings, and 'imprecision' as the effect is towards benefit but the 95% CI are wide and include no effect.

Potential biases in the review process

The inclusion criteria of this Cochrane Review may increase the possibility of poor reproducibility due to many subjective decisions regarding which studies and populations to include. We included all HIV‐positive populations (both genders) and we had no exclusion criteria regarding settings when we selected studies for inclusion. However, we minimized this potential bias by including stringent follow‐up time criteria and only RCTS.

We only assessed peer‐reviewed published trials, which may have led to exclusion of trials in grey literature and presented at conferences. Having no knowledge of unpublished studies may have limited the assessment of the strength of the body of evidence in the review. Another limitation is that we only included papers that reported in English, thus disregarding high quality trials that may have been published in other languages.

We selected only trials that used validated scales, which is a strength of the review. We amended specified outcomes by only including psychological outcomes and no longer behavioural outcomes after we realized that there were poor or invalidated assessments for behavioural outcomes in the first set of literature search results (June 2013). Our decision to change specified outcomes after seeing the results for included studies could have lead to biased and misleading interpretation if the importance of the outcome (primary or secondary) is changed on the basis of those results. We have provided transparency in the reporting of changes in outcome specification to reduce this risk of bias.

Even when review authors have a common understanding of the selection criteria, random error or mistakes may result from individual errors in reading and reviewing studies. We reduced this potential bias by ensuring that all review authors read the papers and extracted data independently, and then came to mutual agreements.

We noted issues regarding poor reporting in the papers and we were unable to obtain all relevant data due to the lack of responses from study authors about missing data or clarification of data.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

To our knowledge, no published systematic review has assessed the psychological impact of psychosocial group interventions for HIV positive adults.

The findings of this Cochrane Review are in contrast to a narrative review (Brown 2011), as well as older meta‐analysis syntheses (Crepaz 2008; Scott‐Sheldon 2008), of the effect of various group interventions on outcomes for improved mental health. These report on how stress management and cognitive behavioural interventions and mindfulness‐based interventions are effective in improving various psychological states in people living with HIV. However, Crepaz 2008 did not assess the randomization method, allocation concealment, and blinding used by the trials, thus making data extraction and quality assessment less rigorous. Scott‐Sheldon 2008's meta‐analytic review of RCTs of stress‐management interventions showed significant overall impact on mental health, whereas Brown 2011's narrative critique of the effectiveness of mindfulness based intervention is the only review of the effectiveness of mindfulness‐based interventions on mental health that we found. However, the Brown 2011 review is undermined by inclusion of trials that did not fit our stringent inclusion criteria that trials must have had longer than three months follow‐up in order to show sustained effects, and did not include a meta‐analysis. Similar to our Cochrane Review, current published reviews on this subject mainly include trials in high‐income settings, which makes a strong case for high quality research to be funded and motivated for marginalized populations where HIV is most prevalent.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Group‐based psychosocial interventions may have a small but sustained effect on measures of depression. However, the clinical importance of this is unclear as we only consistently observed the small effect in trials where the mean score of participants in both the intervention and control groups was in the normal range (not depressed) for the duration of the trial.

Implications for research.

Further trials that include people with signs of depression, stress, or poor coping at baseline will provide evidence of improving psychological adjustment and coping for those who need it most.

Further randomized studies should also meet current standards in reporting of methods as outlined in the CONSORT statement and take appropriate steps to reduce the risk of bias.

To enable a clear understanding of the results, and facilitate future meta‐analyses, it would also be useful if this research field utilized a common set of outcome scales rather than the ad‐hoc selection that is seen across the included studies.

Additionally, evidence is lacking where HIV prevalence is the highest. This indicates a need for strengthening trial research capacity in low‐ and middle‐income settings.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Anne‐Marie Stephani and Paul Garner of the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group (CIDG), and Elizabeth Pienaar and Tamara Kredo of Cochrane South Africa for their valuable encouragement and help with this review.

David Sinclair is supported by the Effective Health Care Research Consortium. This Consortium and the editorial base of the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group is funded by UK aid from the UK Government for the benefit of low‐ and middle‐income countries (Grant: 5242). The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect UK government policy.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

| Search set | CENTRAL | MEDLINE | Embase |

| 1 | MeSH descriptor: [HIV Infections] explode all trees | (HIV Infections[MeSH] OR HIV[MeSH] OR hiv[tiab] OR hiv‐1*[tiab] OR hiv‐2*[tiab] OR hiv1[tiab] OR hiv2[tiab] OR hiv infect*[tiab] OR human immunodeficiency virus[tiab] OR human immunedeficiency virus[tiab] OR human immuno‐deficiency virus[tiab] OR human immune‐deficiency virus[tiab] OR ((human immun*[tiab]) AND (deficiency virus[tiab])) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome[tiab] OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome[tiab] OR acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome[tiab] OR acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome[tiab] OR ((acquired immun*[tiab]) AND (deficiency syndrome[tiab])) OR "sexually transmitted diseases, Viral"[MeSH:NoExp])) | 'human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus':ab,ti OR 'human immuno+deficiency virus':ab,ti OR 'human immunedeficiency virus':ab,ti OR 'human immune+deficiency virus':ab,ti OR hiv:ab,ti OR 'hiv‐1':ab,ti OR 'hiv‐2':ab,ti OR 'acquired immunodeficiency syndrome':ab,ti OR 'acquired immuno+deficiency syndrome':ab,ti OR 'acquired immunedeficiency syndrome':ab,ti OR 'acquired immune+deficiency syndrome':ab,ti |

| 2 | MeSH descriptor: [HIV] explode all trees | (randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized [tiab] OR placebo [tiab] OR drug therapy [sh] OR randomly [tiab] OR trial [tiab] OR groups [tiab]) NOT (animals [mh] NOT humans [mh]) | (psychosocial NEXT/1 intervention*):ab,ti OR 'social support'/syn OR 'social support':ab,ti OR (social NEXT/1 network*):ab,ti OR (support NEXT/1 system*):ab,ti OR 'self help'/syn OR ('self‐help' NEXT/1 group*):ab,ti OR (support NEXT/1 group*):ab,ti OR 'educational therapy':ab,ti OR 'psychotherapy'/syn OR psychotherapy:ab,ti OR 'group therapy'/syn OR 'group therapy':ab,ti OR 'behavior therapy':ab,ti OR 'behaviour therapy':ab,ti OR 'family therapy':ab,ti OR 'group interventions':ab,ti OR 'cognitive therapy':ab,ti OR 'cognition therapy':ab,ti OR (psychological NEXT/1 adjustment*):ab,ti OR 'psychological adaptation':ab,ti OR (adaptive NEXT/1 behavior*):ab,ti OR (adaptive NEXT/1 behaviour*):ab,ti OR (coping NEXT/1 behavio*):ab,ti OR (coping NEXT/1 intervention*):ab,ti OR (coping NEXT/1 strateg*):ab,ti OR (coping NEXT/1 skill*):ab,ti |

| 3 | hiv or hiv‐1* or hiv‐2* or hiv1 or hiv2 or HIV INFECT* or HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS or HUMAN IMMUNEDEFICIENCY VIRUS or HUMAN IMMUNE‐DEFICIENCY VIRUS or HUMAN IMMUNO‐DEFICIENCY VIRUS or HUMAN IMMUN* DEFICIENCY VIRUS or ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME or ACQUIRED IMMUNEDEFICIENCY SYNDROME or ACQUIRED IMMUNO‐DEFICIENCY SYNDROME or ACQUIRED IMMUNE‐DEFICIENCY SYNDROME or ACQUIRED IMMUN* DEFICIENCY SYNDROME | (psychosocial intervention*[tiab] OR social support[mh] OR social network*[tiab] OR social support[tiab] OR support system[tiab] OR support systems[tiab] OR self‐help groups[mh] OR self‐help group[tiab] OR self‐help groups[tiab] OR support group[tiab] OR support groups[tiab] OR educational therapy[tiab] OR psychotherapy[mh] OR psychotherapy[tiab] OR behavior therapy[tiab] OR behaviour therapy[tiab] OR family therapy[tiab] OR group therapy[tiab] OR group interventions[tiab] OR cognitive therapy[tiab] OR cognition therapy[tiab] OR adaptation, psychological[mh] OR psychological adjustment[tiab] OR psychological adjustments[tiab] OR psychological adaptation[tiab] OR adaptive behavior[tiab] OR adaptive behaviors[tiab] OR adaptive behaviour[tiab] OR adaptive behaviours[tiab] OR coping behavio* [tiab] OR coping intervention*[tiab] OR coping strateg*[tiab] OR coping skill*[tiab]) | #1 AND #2 |

| 4 | MeSH descriptor: [Lymphoma, AIDS‐Related] this term only | (#1 AND #2 AND #3) | 'randomized controlled trial'/de OR 'randomized controlled trial' OR random*:ab,ti OR trial:ti OR allocat*:ab,ti OR factorial*:ab,ti OR placebo*:ab,ti OR assign*:ab,ti OR volunteer*:ab,ti OR 'crossover procedure'/de OR 'crossover procedure' OR 'double‐blind procedure'/de OR 'double‐blind procedure' OR 'single‐blind procedure'/de OR 'single‐blind procedure' OR (doubl* NEAR/3 blind*):ab,ti OR (singl*:ab,ti AND blind*:ab,ti) OR crossover*:ab,ti OR cross+over*:ab,ti OR (cross NEXT/1 over*):ab,ti |

| 5 | MeSH descriptor: [Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Viral] this term only[DW1] | Search (((#1 AND #2 AND #3))) | 'animal'/de OR 'animal experiment'/de OR 'invertebrate'/de OR 'animal tissue'/de OR 'animal cell'/de OR 'nonhuman'/de |

| 6 | #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 | — | 'human'/de OR 'normal human'/de OR 'human cell'/de |

| 7 | MeSH descriptor: [Social Support] explode all trees | — | #5 AND #6 |

| 8 | MeSH descriptor: [Self‐Help Groups] explode all trees | — | #5 NOT #7 |

| 9 | MeSH descriptor: [Psychotherapy] explode all trees | — | #4 NOT #8 |

| 10 | MeSH descriptor: [Adaptation, Psychological] explode all trees | — | #3 AND #9 |

| 11 | "psychosocial intervention*":ti,ab,kw or "social support":ti,ab,kw or (social next network*):ti,ab,kw or (support next system*):ti,ab,kw or (self‐help next group*):ti,ab,kw or (support next group*):ti,ab,kw or educational therapy:ti,ab,kw or psychotherapy:ti,ab,kw or "behavior therapy":ti,ab,kw or "behaviour therapy":ti,ab,kw or "family therapy":ti,ab,kw or "group therapy":ti,ab,kw or "group interventions":ti,ab,kw or "cognitive therapy":ti,ab,kw or "cognition therapy":ti,ab,kw or (psychological next adjustment*):ti,ab,kw or "psychological adaptation":ti,ab,kw or "adaptive behavior":ti,ab,kw or "adaptive behaviour":ti,ab,kw or "coping behavior":ti,ab,kw or "coping behaviour":ti,ab,kw or "coping skills":ti,ab,kw or "coping strategies":ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | — | #3 AND #9 |

| 12 | #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 | — | — |

| 13 | #6 and #12 | — | — |

Appendix 2. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

Search strategy: (psychosocial OR "social support" OR "coping skills" OR "self‐help groups" OR "cognitive therapy") AND hiv | Interventional Studies | received from 01/01/1996 to 03/14/2016

Appendix 3. Data extraction form