Abstract

DNA methylation is associated with gene silencing in eukaryotic organisms. Although pathways controlling the establishment, maintenance and removal of DNA methylation are known, relatively little is understood about how DNA methylation influences gene expression. Here we identified a METHYL-CpG-BINDING DOMAIN 7 (MBD7) complex in Arabidopsis thaliana that suppresses the transcriptional silencing of two LUCIFERASE (LUC) reporters via a mechanism that is largely downstream of DNA methylation. Although mutations in components of the MBD7 complex resulted in modest increases in DNA methylation concomitant with decreased LUC expression, we found that these hyper-methylation and gene expression phenotypes can be genetically uncoupled. This finding, along with genome-wide profiling experiments showing minimal changes in DNA methylation upon disruption of the MBD7 complex, places the MBD7 complex amongst a small number of factors acting downstream of DNA methylation. This complex, however, is unique as it functions to suppress, rather than enforce, DNA methylation-mediated gene silencing.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.19893.001

Research Organism: A. thaliana

Introduction

DNA methylation is a highly conserved chromatin modification that is associated with gene silencing and plays critical roles in imprinting, transposon repression, and diverse developmental processes in eukaryotic organisms. In Arabidopsis, methylated regions of the genome can be separated into two main categories: (1) transposons and repeats that are heavily methylated at cytosines in all sequence contexts (namely CG, CHG and CHH where H indicates A, T or C), leading to gene silencing, and (2) body-methylated genes that harbor methylation exclusively in the CG context but remain highly expressed (Lister et al., 2008; Cokus et al., 2008). These global patterns of cytosine methylation reflect a balance between pathways controlling de novo methylation, maintenance methylation and demethylation (Law et al., 2010a; Matzke and Mosher, 2014).

De novo methylation of cytosines in all sequence contexts requires the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway (Law et al., 2010a; Matzke and Mosher, 2014), which utilizes both 24-nucleotide small interfering RNAs (24-nt siRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs to target the de novo methyltransferase, DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLTRANSFERASE 2 (DRM2), to repetitive regions of the genome. Production of both 24-nt siRNAs and non-coding RNAs requires specialized RNA polymerases (Haag and Pikaard, 2011; Zhou et al., 2015). Pol IV transcripts were recently identified (Blevins et al., 2015; Zhai et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015a) and these short non-coding RNAs are processed into 24-nt siRNAs in a one precursor, one siRNA fashion (Blevins et al., 2015; Zhai et al., 2015) and then loaded into the ARGONAUTE 4 (AGO4) clade of effector proteins. Pol V also generates non-coding RNAs at RdDM targets and these RNAs serve as a scaffold for the recruitment of many downstream RdDM factors, including siRNA-loaded AGO4 effector complexes and DRM2, ultimately leading to the deposition of DNA methylation and the establishment of gene silencing.

After the initial establishment of DNA methylation, several maintenance DNA methylation pathways are in place to ensure the faithful inheritance of DNA methylation patterns (Law et al., 2010a; Matzke and Mosher, 2014). Briefly, maintenance of CG methylation requires DNA METHYLTRANSFERASE 1 (MET1), whereas maintenance of CHG methylation (and some CHH methylation) relies on the activity of two related DNA methyltransferases, CHROMOMETHYLASE 2 and 3 (CMT2 and CMT3) (Stroud et al., 2014; Zemach et al., 2013). Finally, the remaining CHH methylation is maintained by DRM2 via the continuous action of the RdDM pathway.

Acting in opposition to the DNA methylation machinery are several DNA glycosylases, REPRESSOR OF SILENCING 1 (ROS1) and three paralogs: DEMETER (DME), DEMETER-LIKE 2 (DML2), and DEMETER-LIKE 3 (DML3). These glycosylases specifically remove methyl-cytosine bases, resulting in a net loss of DNA methylation (Zhu, 2009). While DME plays an essential role during plant reproduction, ROS1, DML2, and DML3 act in a semi-redundant manner to remove DNA methylation in vegetative tissue (Lister et al., 2008; Zhu, 2009; Penterman et al., 2007). These proteins tend to remove DNA methylation in regions that flank genes, and in ros1 dml2 dml3 (rdd) triple mutants a subset of these genes are silenced, leading to a model in which ROS1, DML2 and DML3 function to remove DNA methylation and prevent transcriptional gene silencing (Lister et al., 2008; Zhu, 2009; Penterman et al., 2007).

Finally, to interpret the patterns of DNA methylation, there are two large families of methyl-DNA binding proteins in plants, both of which are conserved in mammals: the SET AND RING ASSOCIATED (SRA) domain family, and the METHYL-CpG-BINDING domain (MBD) family (Defossez and Stancheva, 2011; Fournier et al., 2012). While specific roles for several SRA domain proteins in the establishment and/or maintenance of DNA methylation in plants and mammals have been determined (Johnson et al., 2007, 2008; Woo et al., 2008; Bostick et al., 2007; Sharif et al., 2007), roles for plant MBDs remain largely unknown. In mammals, MBD proteins function as part of large protein complexes associated with histone deacetylase and methyltransferase activities important for the establishment of repressive chromatin states (Jones et al., 1998; Nan et al., 1998; Fuks et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 1999). In Arabidopsis, there are 13 proteins that contain MBD domains (MBD1-13) (Grafi et al., 2007; Zemach and Grafi, 2007). Of these MBD proteins, early studies demonstrated that MBD5, MBD6 and MBD7 bind methylated DNA in vitro and localize to highly methylated, peri-centromeric regions of the genome in vivo, suggesting roles for these factors in gene silencing (Zemach and Grafi, 2003; Scebba et al., 2003; Ito et al., 2003; Zemach et al., 2005). A better understanding of how the MBD proteins bridge the gap between DNA methylation and gene regulation, however, is just beginning to emerge. For example, MBD6 and MBD10 play roles in nucleolar dominance and rDNA silencing (Preuss et al., 2008), whereas MBD7 has been implicated in DNA demethylation based on genetic connections with the DNA demethylase, ROS1 (Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2015).

Compared to the wealth of mechanistic detail regarding the proteins and pathways required to establish, maintain and even remove DNA methylation, relatively little is known about the events occurring downstream of DNA methylation. Previous genetic screens have identified MORPHEUS MOLECULE 1 (MOM1) (Amedeo et al., 2000; Won et al., 2012), and MICRORCHIDIA 1 and 6 (MORC1 and MORC6) (Moissiard et al., 2012; Lorković et al., 2012; Brabbs et al., 2013), as genes that are required for the silencing of methylated loci but that do not control the levels of DNA methylation (Amedeo et al., 2000; Won et al., 2012; Moissiard et al., 2012; Lorković et al., 2012). In addition, mutations in ARABIDOPSIS TRITHORAX-RELATED PROTEIN 5 and 6 (atxr5 and atxr6) (Jacob et al., 2009) were also found to release gene silencing without significantly altering the pattern of DNA methylation. These findings suggest that there are factors that function downstream (or independently) of DNA methylation to facilitate gene silencing though unknown mechanisms. On the other hand, only one factor, SU(VAR)3–9 HOMOLOG 1 (SUVH1) (Li et al., 2016), has been identified to act downstream of DNA methylation to enable the transcription of methylated loci.

In the present study, we demonstrate a role for MBD7 and its associated proteins (LOW IN LUCIFERASE EXPRESSION (LIL) and REPRESSOR OF SILENCING 5 (ROS5), two Alpha Crystallin Domain (ACD) proteins, as well as REPRESSOR OF SILENCING 4 (ROS4)), in the suppression of gene silencing at methylated luciferase (LUC) reporter transgenes. In addition, we show that MBD5 co-purifies with a distinct set of ACD proteins but, unlike MBD7, is not required for LUC expression, suggesting different roles for the MBD5 and MBD7 complexes. To gain mechanistic insights into the role of the MBD7 complex in regulating gene expression, the DNA methylation and LUC expression levels at the reporter transgenes were determined in mbd7, lil, ros4 and ros5 mutants. These analyses revealed that members of the MBD7 complex function to promote luciferase expression without significantly altering DNA methylation levels. Furthermore, genome-wide characterization of DNA methylation patterns in mbd7, lil, and rdd mutants revealed little to no overlapping changes in DNA methylation. Together, these findings support a role for the MBD7 complex in the suppression of gene silencing that is primarily downstream of DNA methylation. While several proteins have been identified that reinforce gene silencing downstream of DNA methylation, the MBD7 complex is unique in its ability to overcome the silencing effects of DNA methylation, enabling the expression of several transgenes despite high levels of promoter methylation.

Results

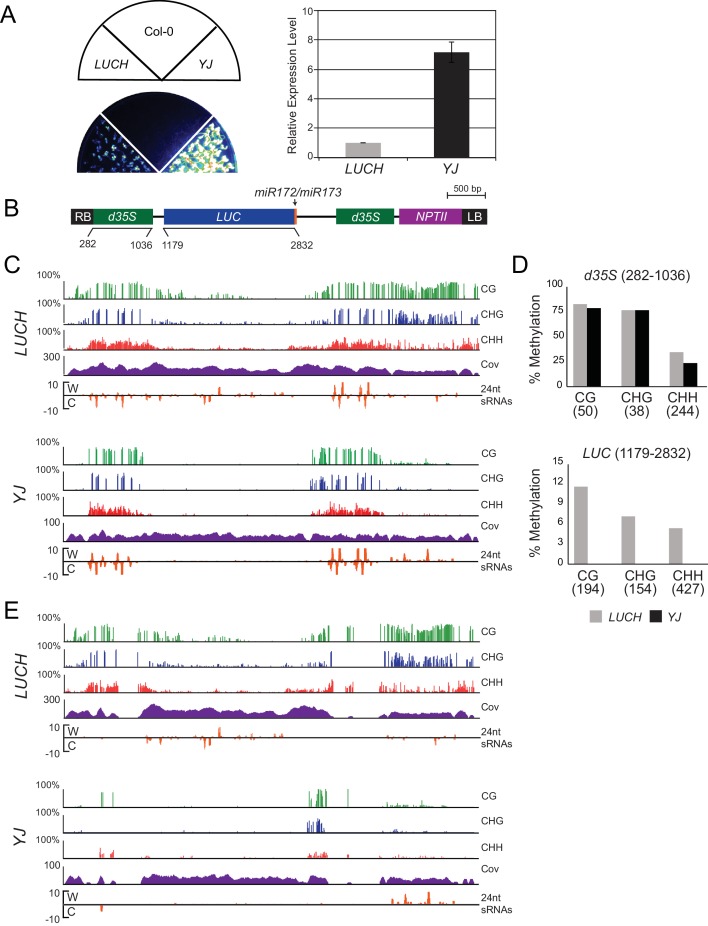

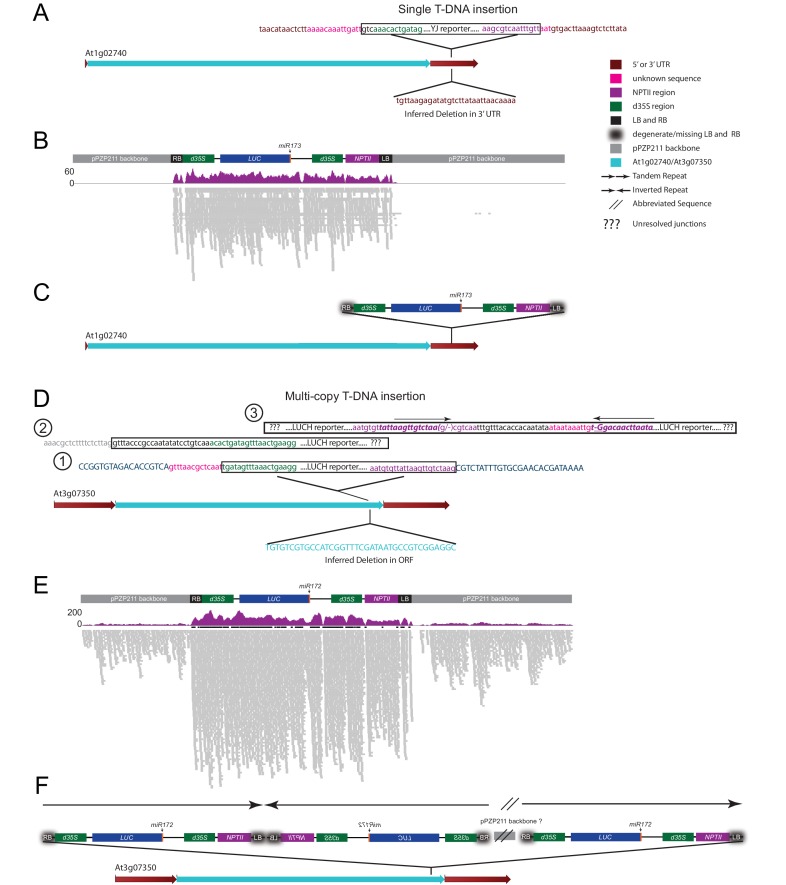

Characterization of two luciferase (LUC)-based transcriptional gene silencing reporters

To identify genes that suppress transcriptional gene silencing in Arabidopsis, forward genetic screens were conducted using two LUC-based reporters, LUCH (Won et al., 2012) and YJ (Li et al., 2016), that were introduced into the rdr6-11 mutant background to prevent post-transcriptional silencing. Here we compared the expression patterns and epigenetic features of the two LUC reporters, which differ in their basal levels of LUC expression despite harboring nearly identical transgenes that contain LUC genes driven by dual cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoters (d35S) (Figure 1—source data 1, Figure 1—figure supplements 1A,B). Given the known role of DNA methylation in regulating LUC expression at the LUCH reporter (Won et al., 2012), the DNA methylation and siRNA profiles for both LUCH and YJ reporters were determined by MethylC-sequencing (MethylC-seq) and small RNA sequencing (smRNA-seq), respectively (Supplementary file 1A-D), allowing either multi-mapping (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C) or unique reads (Figure 1—figure supplement 1E). At the d35S promoters, the two transgenes had similar patterns of 24-nt siRNAs and similar levels of DNA methylation in all sequence contexts (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C,D). However, in LUCH, DNA methylation extended beyond the d35S promoters into the LUC and NPTII coding regions (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C,D). One possible explanation for the difference in DNA methylation and LUC expression between YJ and LUCH reporters lies in the nature of the transgene insertions. Although both reporters segregate as single-copy insertions, analysis of the MethylC-seq data supports the conclusion that the YJ and LUCH reporters represent single and multi-copy insertions into a single genomic locus, respectively (Figure 1—figure supplement 2). In addition to their copy number, these transgenes also differ in their integration sites, which may further contribute to their DNA methylation and expression profiles. Despite these differences, both reporters share a common feature that distinguishes them from most endogenous methylated loci: they contain genes that harbor high levels of promoter methylation but are not fully silenced. This feature makes these reporters well suited to screen for proteins that suppress gene silencing at methylated loci.

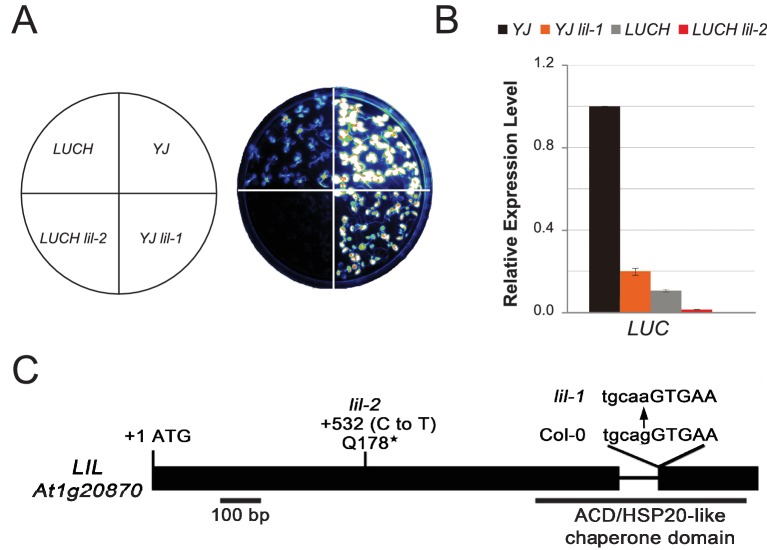

LIL suppresses silencing at two LUC reporters

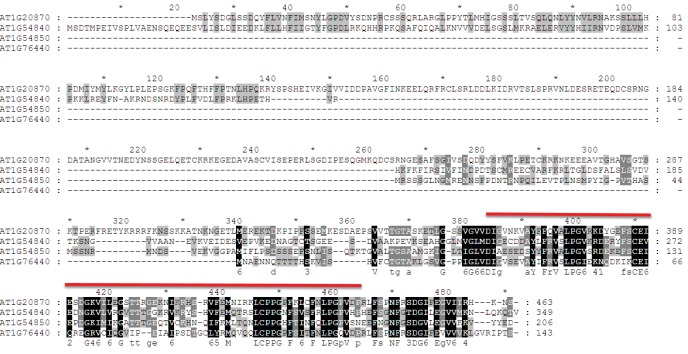

To identify factors that suppress gene silencing at the LUC reporters, two independent genetic screens using either the YJ or the LUCH reporter line, were performed. Two mutants with reduced luciferase luminescence, one in each reporter background, were identified (Figure 1A) and RT-qPCR analysis confirmed reduced LUC expression in these mutant backgrounds relative to their respective controls (Figure 1B). Map-based cloning and candidate gene sequencing revealed that the same gene (At1g20870) was disrupted in both mutants. The alleles isolated from the YJ and LUCH screens are hereafter referred to as lil-1 and lil-2 (LIL, LOW IN LUCIFERASE EXPRESSION), respectively. The lil-1 allele contains a G-to-A mutation, which disrupts the single splice acceptor site of At1g20870 (Figure 1C). Although lil-2 was isolated from a T-DNA mutagenesis screen, this allele does not contain a T-DNA insertion, but instead contains a C-to-T mutation that introduces a premature stop codon (Figure 1C). LIL is predicted to encode a 51.9 kDa protein containing a carboxy-terminal Alpha Crystallin Domain (ACD) or Heat Shock Protein 20 like (HSP20-like) chaperone domain (Figure 1C). Among the 25 Arabidopsis ACD-containing proteins, LIL and three paralogs form one clade (Scharf et al., 2001) (alignments shown in Figure 1—figure supplement 3). Two members of this clade, LIL (also known as INCREASED DNA METHYLATION 3 (IDM3) [Lang et al., 2015] or INCREASED DNA METHYLATION 2-LIKE 1 (IDL1) [Li et al., 2015b]) and ROS5 (Zhao et al., 2014)/IDM2 (Qian et al., 2014) (At1g54840) were recently found to prevent DNA hyper-methylation and enable gene expression at other reporter transgenes and select genomic loci, demonstrating they also act to suppress gene silencing (Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b; Zhao et al., 2014; Qian et al., 2014).

Figure 1. LIL promotes expression of methylated LUC reporters.

(A) Luciferase (LUC) luminescence in YJ, YJ lil-1, LUCH and LUCH lil-2 seedlings as diagramed on the left. (B) Quantification of LUC transcript levels by RT-qPCR. Transcript levels were normalized to UBIQUITIN5 with the expression level of LUC in the YJ control set to one. Error bars indicate the standard deviation from two biological replicates. (C) LIL gene structure showing the positions of the two isolated mutations relative to the exons (black bars) and a single intron (black line). Lower and upper case letters represent intron and exon sequences, respectively. The region encoding the conserved ACD or HSP20-like chaperone domain is indicated below.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.19893.002

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Characterization of the LUCH and YJ luciferase (LUC) reporter lines.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Investigation of transgene copy number.

Figure 1—figure supplement 3. Sequence alignment of LIL and its paralogs.

LIL is associated with MBD7

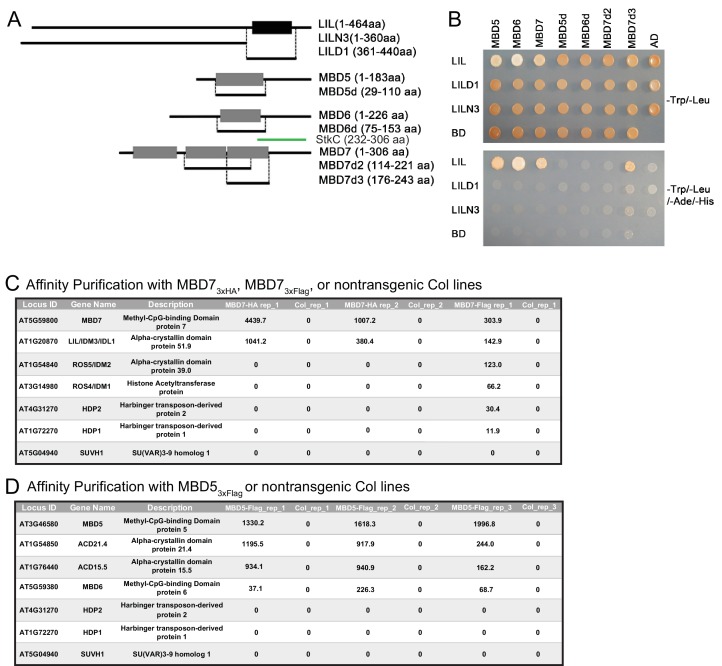

To gain insight into the function of LIL, a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screen was conducted to identify LIL-interacting proteins. Using full-length LIL as bait and an Arabidopsis cDNA library as prey, LIL was found to interact with three MBD proteins: MBD5, MBD6 and MBD7 (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A,B). To map the interaction domains of these proteins, select subdomains were subjected to additional Y2H assays (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A,B). Using either the N-terminal portion of LIL (LILN3) or the ACD/HSP20 domain alone (LILD1), no interactions were observed with the full length MBD proteins (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A,B). However, an interaction was detected between the last MBD domain of MBD7 (MBD7d3) and the full length LIL protein (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A,B). Previously, Lang et al. (2015) mapped the interaction domain between LIL and MBD7 to the C-terminal sticky-c (StkC) domain (Zemach et al., 2009) of MBD7 and found that the three MBD domains of MBD7 alone were not sufficient to mediate an interaction with LIL. However, the MBD7d3 construct used here represents an extended version of the third MBD domain that has minimal overlap with the StkC domain, suggesting that the interaction between MBD7 and LIL can be mediated by several regions of the MBD7 protein, namely, the StkC domain (Lang et al., 2015), as well as the last MBD domain (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A,B).

In a parallel effort, epitope-tagged versions of MBD5 and MBD7, expressed under the control of their endogenous promoters, were affinity purified and found to associate with distinct sets of ACD domain proteins by Mass Spectrometry (Figure 2—figure supplement 1C,D). Specifically, a 3x-Flag-tagged version of MBD5 (pMBD5::MBD5-3x-Flag) was shown to co-purify with ACD15.5 (At1g76440) and ACD21.4 (At1g54850) as well as low amounts of MBD6 (Figure 2—figure supplement 1D), while purification of a 3x-HA tagged version of MBD7 (pMBD7::MBD7-3xHA) revealed a specific interaction with LIL (Figure 2—figure supplement 1C). As MBD7 had previously been shown to also associate with ROS4, ROS5 (Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2015), and HARBINGER TRANSPOSON-DERIVED PROTEIN 1 (HDP1) and HDP2 (Duan et al., 2017), additional purifications using a 3x-Flag-tagged version of MBD7 (pMBD7::MBD7-3xFlag) were conducted and these experiments yielded peptides corresponding to LIL as well as all the aforementioned MBD7-associated proteins (Figure 2—figure supplement 1C). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that MBD5 and MBD7 associate with different subsets of ACD proteins to form distinct MBD-ACD protein complexes, the roles and compositions of which are just beginning to be explored.

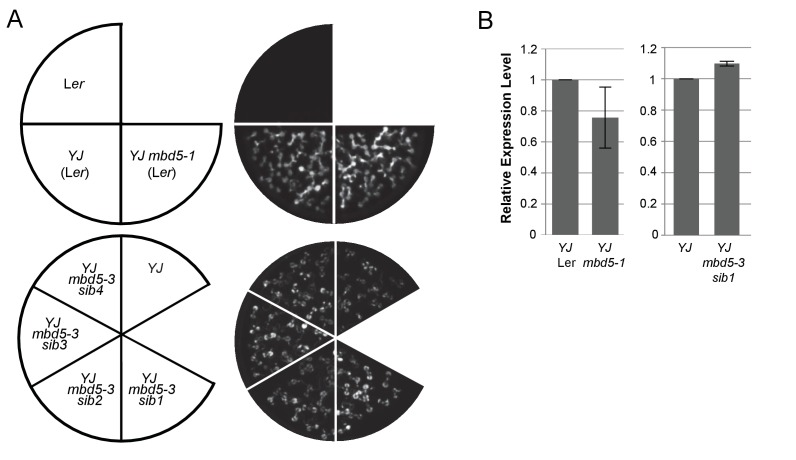

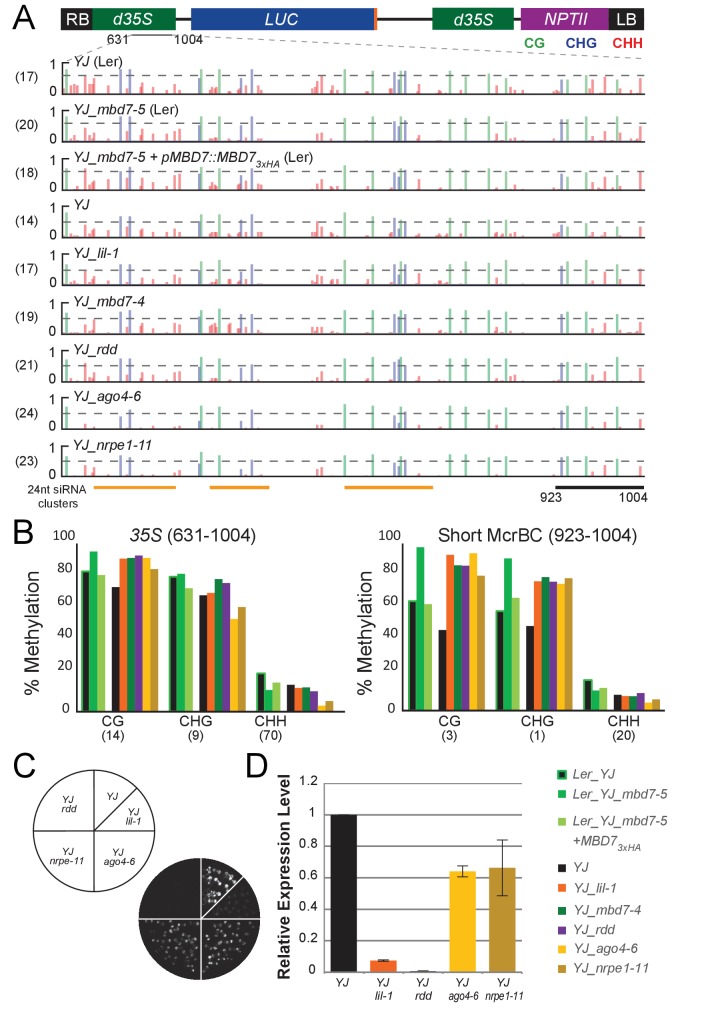

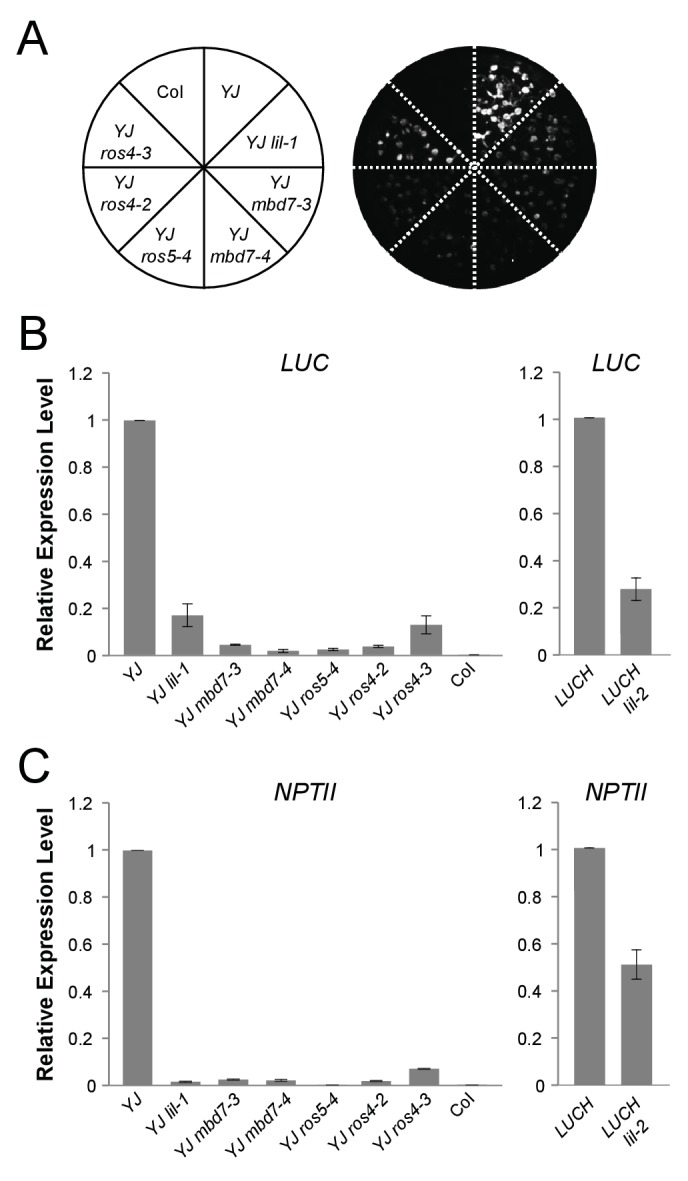

MBD7–associated factors suppress silencing at the LUC reporter

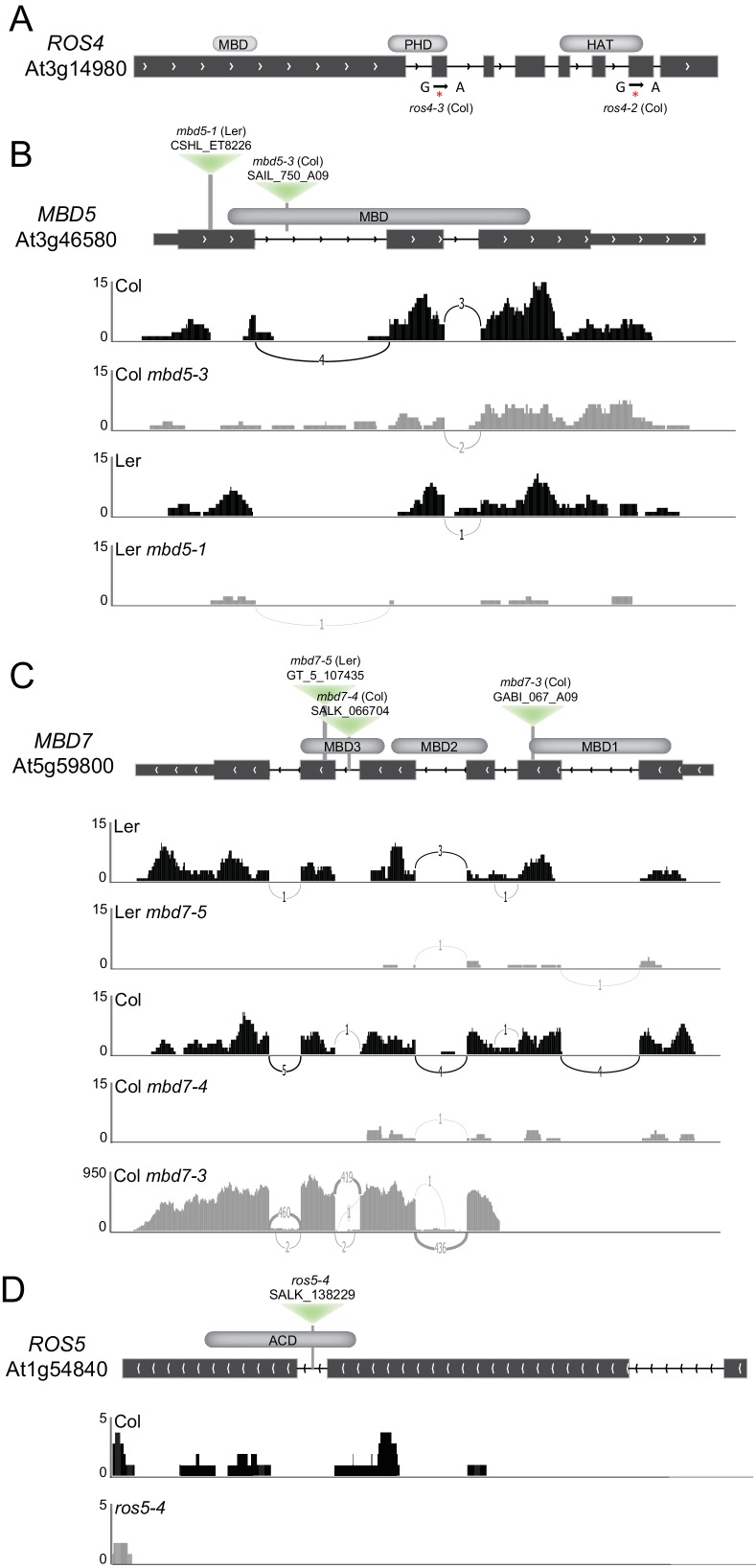

To determine the roles of the MBD5 and MBD7 complexes in the regulation of gene expression, mutant alleles in the various components were obtained (Figure 2—figure supplement 2) and their effect on LUC expression was determined. For these experiments, two alleles of ROS4 (ros4-2 and ros4-3) were recovered from the YJ reporter screen and the following additional mutant lines were crossed into the YJ reporter background in either the Col or Ler ecotypes (see Materials and methods): mbd5-1, mbd5-3, mbd7-3, mbd7-4, mbd7-5, and ros5-4. The mbd5 mutations had no effect on LUC expression at the YJ reporter (Figure 2—figure supplement 3A,B). Conversely, in the mbd7, ros4, and ros5 mutants, LUC expression was reduced to similar levels as observed in lil-1 (Figure 2A,B). In addition, expression of the d35S-driven NPTII gene present in both YJ and LUCH reporters was also reduced in these mutants (Figure 2C). These findings are consistent with the co-purification of these factors by Mass Spectrometry and demonstrate a role for the MBD7 complex, but not MBD5, in promoting the expression of the LUC reporter.

Figure 2. mbd7, ros4, and ros5 mutants phenocopy lil-1 at the YJ transgene.

(A) Luciferase (LUC) luminescence in 10-day-old seedlings as diagramed on the left. (B) Quantification of LUC or (C) NPTII transcript levels by RT-qPCR. Transcript levels were normalized to UBIQUITIN5 with the expression level of LUC or NPTII in the YJ or LUCH controls set to one. Error bars indicate the standard deviation from two biological replicates.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Yeast two-hybrid and affinity purification analyses.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. Isolation and characterization of ros4, mbd5, mbd7, and ros5 mutants.

Figure 2—figure supplement 3. mbd5 mutants do not exhibit reduced LUC expression.

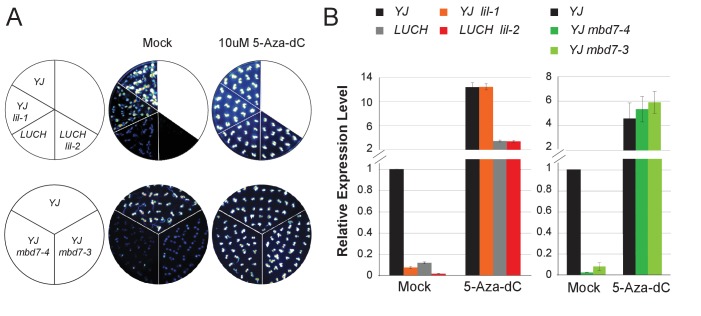

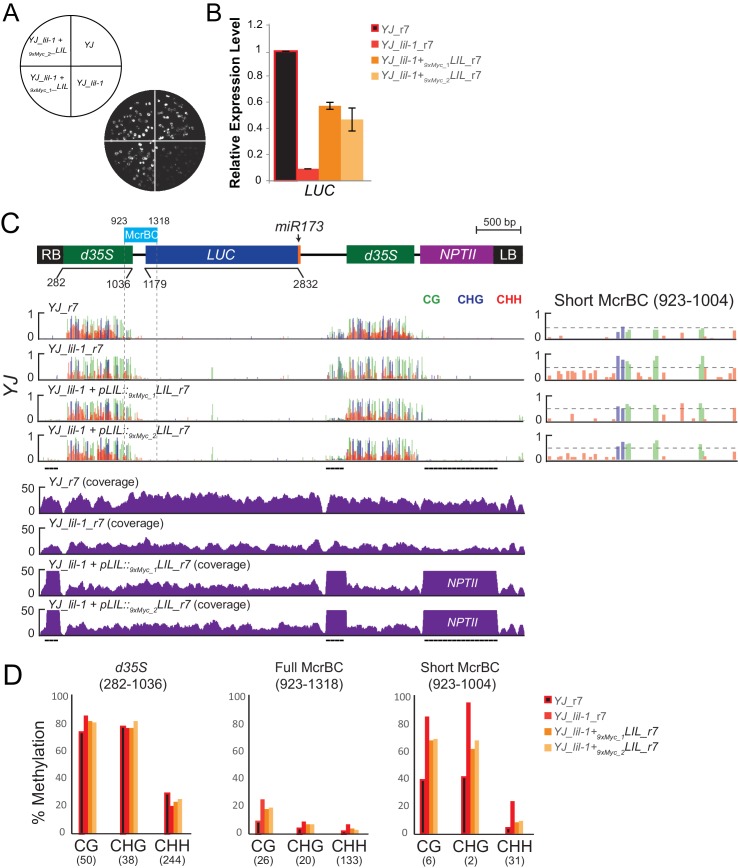

The MBD7-LIL complex regulates LUC expression at the transcriptional level

Previous analyses have shown that both the YJ (Li et al., 2016) and LUCH (Won et al., 2012) reporters are regulated by DNA methylation such that treatment with the cytosine methylation inhibitor 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-Aza-dC) results in increased LUC expression. To determine if DNA methylation is necessary for the phenotypes observed upon disruption of the MBD7 complex, we assessed the effects of 5-Aza-dC treatment on LUC expression in several alleles of lil and mbd7 and found the levels of LUC expression in these mutants were indistinguishable from their respective controls (Figure 3A,B). Thus, LIL and MBD7 are only necessary for the expression of the LUC reporters when they harbor DNA methylation, affirming their roles in the transcriptional, rather than post-transcriptional, regulation of LUC expression.

Figure 3. MBD7 and LIL regulate LUC expression in a DNA methylation-dependent manner.

(A) Luciferase luminescence of mock or 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-Aza-dC)-treated seedlings as diagramed on the left. (B) Quantification of LUC transcript levels by RT-qPCR. LUC transcript levels were normalized to UBIQUITIN5 with the expression level of LUC in the YJ control set to one. Error bars indicate the standard deviation from three biological replicates for the mbd7 datasets and three technical replicates for the lil dataset.

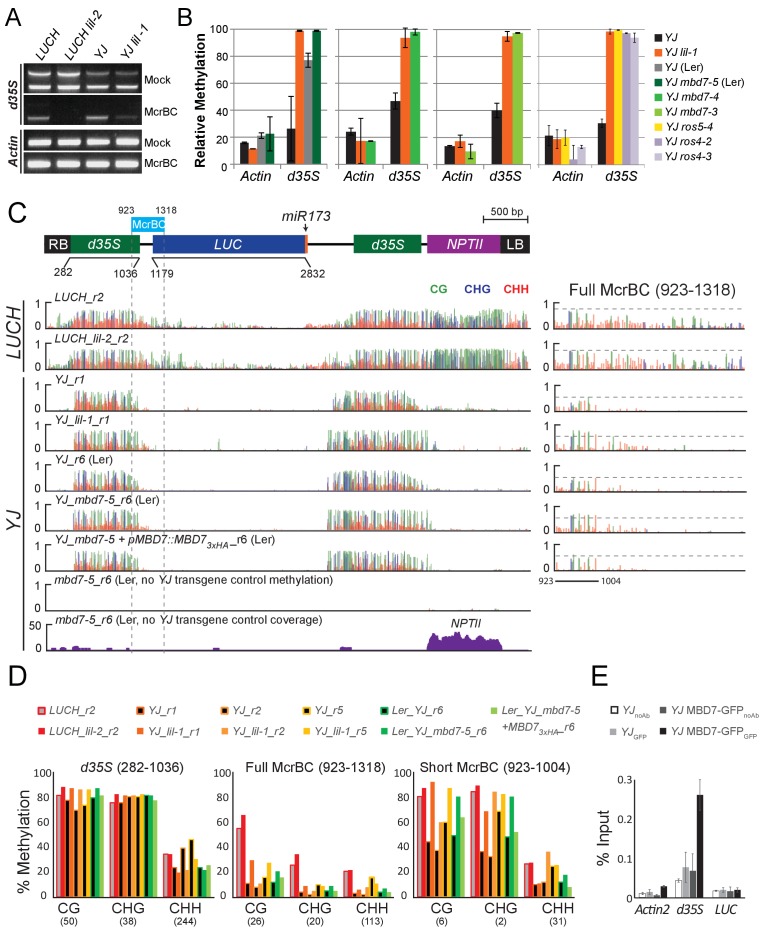

Disruption of the MBD7 complex results in minimal effects on DNA methylation at the LUC reporters

To determine whether the decreased LUC expression observed upon disruption of the MBD7 complex is associated with an increase in DNA methylation, methyl-DNA cutting assays and MethylC-seq experiments were conducted. For the methylation cutting assays, genomic DNA was either mock treated or digested with the McrBC restriction enzyme followed by PCR amplification. Since McrBC specifically cuts methylated DNA, hyper-methylated targets are expected to exhibit reduced levels of PCR amplification. Using this assay, amplification of the d35S promoter was reduced in both lil mutants relative to their respective controls, indicating that mutations in LIL increased the level of DNA methylation at the d35S promoter (Figure 4A; gel based). Similar results were obtained for lil-1, mbd7, ros4, and ros5 mutants when qPCR was performed to quantify DNA levels from mock or McrBC treated samples (Figure 4B; qPCR). Together, these analyses reveal a correlation between disruption of the MBD7 complex and an increase in DNA methylation at the d35S promoter driving LUC expression, but they do not reveal the location or extent of hyper-methylation.

Figure 4. Disruption of the MBD7 complex results in subtle, but reproducible hyper-methylation at the d35S promoter.

Cytosine methylation analysis by McrBC-PCR (A) and McrBC-qPCR (B) using mock or McrBC treated genomic DNA from the indicated genotypes. In (A), two tandem copies of the 35S sequence result in two PCR bands. ACTIN1, which lacks methylation, was used as the internal loading control. In (B), the relative methylation levels are plotted and the error bars indicate the standard deviation from two biological replicates. (C) A diagram of the YJ reporter drawn to scale relative to the browser tracks shown directly below. The light blue box indicates the region amplified for the McrBC assay. This region is expanded in the far right panel. DNA methylation tracks show the DNA methylation level (0–1, where 1 = 100% methylated) in the CG (green), CHG (blue), and CHH (red) sequence contexts at cytosines covered by at least five reads. The LUCH_r2 and YJ_r1 tracks correspond to those shown in Figure 1—figure supplement 1. The YJ mbd7-5 + pMBD7::MBD7-3xHA_r6 (Ler) line corresponds to the ‘ins1a’ line characterized in Figure 4—figure supplement 1. The coverage track for mbd7-5_r6 (bottom) shows the number of reads (y-axis) mapped to the transgene, demonstrating that sequence homology between the T-DNA in the mbd7-5 mutant and the LUC reporter is largely limited to the NPTII drug resistance gene. To facilitate visual assessment of the changes in DNA methylation, dashed horizontal lines are set relative to the maximal CG methylation at the 3’ end of the d35S promoter in the control LUCH and YJ reporters. (D) Quantification of the average percent methylation across the entire d35S promoter (282–1036), the Full McrBC region (923–1318) or a Short MrcBC region (923–1004) within the YJ transgene in the lines presented in (C). Each sample is appended with an ‘r#’ to indicate samples that were processed and sequenced together. Identical genotypes with different r#’s indicate biological replicates (e.g., YJ_r1, YJ_r2, and YJ_r5 are biological replicates). The number of cytosines in each sequence context within the quantified regions is indicated in parentheses. Note that the two d35S promoters driving LUC and NPTII are 94% identical in sequences, thus the DNA methylation data includes both multi-mapping and unique reads. (E) ChIP-qPCR showing enrichment of MBD7-GFP at the d35S promoter driving LUC expression at the YJ reporter. The data represents the average enrichment from three biological replicates as a percentage of the input and the error bars represent the standard deviation between replicates.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Complementation of the mbd7-5 phenotype with MBD7-3xHA.

To quantitatively determine the changes in methylation occurring across the entirety of the LUC reporters upon disruption of the MBD7 complex, the patterns of DNA methylation were determined at single nucleotide resolution by bisulfite sequencing using the MethylC-seq method (Urich et al., 2015) in mbd7 and lil mutants (Supplementary file 1A, 1B and 1E). These transgene analyses were limited to the lil-1 and lil-2 alleles, which are point mutations, and the mbd7-5 allele, which is the only mbd7 allele where the T-DNA insertion does not share sequence homology with the d35S promoters present in the LUC reporters (Figure 4C, see ‘no YJ transgene control tracks’). At the LUC reporters, quantification of the average methylation levels across the d35S promoter (282–1036 nt) revealed a surprisingly modest but consistent increase in DNA methylation in the CG context in lil-2, mbd7-5, and three biological replicates of lil-1 (Figure 4D). Further inspection of the DNA methylation profiles revealed that this hyper-methylation is largely restricted to a small region at the 3’ end of the d35S promoter, which is within the region amplified in the McrBC-PCR methyl-cutting assays (Figure 4C; right panels). Quantification of DNA methylation at this region was assessed either in its entirety (923–1318), to best evaluate the change in methylation at the LUCH reporter, or in a more limited region (923–1004) that encompasses most of the methylation observed in the YJ reporter. In the lil-2 mutant, a slight increase in CG and CHG methylation, but no change in CHH methylation, was observed at the LUCH reporter (Figure 4D; Full McrBC). For the lil-1 replicates and mbd7-5, a more prominent increase in CG and CHG methylation was observed, and these DNA methylation defects were significantly reversed by introduction of an MBD7-3xHA construct that rescues the LUC expression phenotype at the YJ reporter (Figure 4D short McrBC and Figure 4—figure supplement 1A, respectively). As these findings reveal a correlation between the presence of a functional MBD7 complex and the DNA methylation status of the YJ reporter, several chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments were conducted to determine whether the MBD7 complex associates with this reporter. While no enrichment was observed with either the 3xHA or 3xFlag tagged MBD7 proteins expressed under their native promoters, enrichment was observed at the d35S promoter using a previously characterized MBD7-GFP line driven by a 35S promoter (Wang et al., 2015) (Figure 4E). Taken together, these methylation and ChIP analyses are consistent with the hyper-methylation phenotype observed in the methyl-cutting assays and suggest a direct role for the MBD7 complex in regulating expression at the YJ reporter.

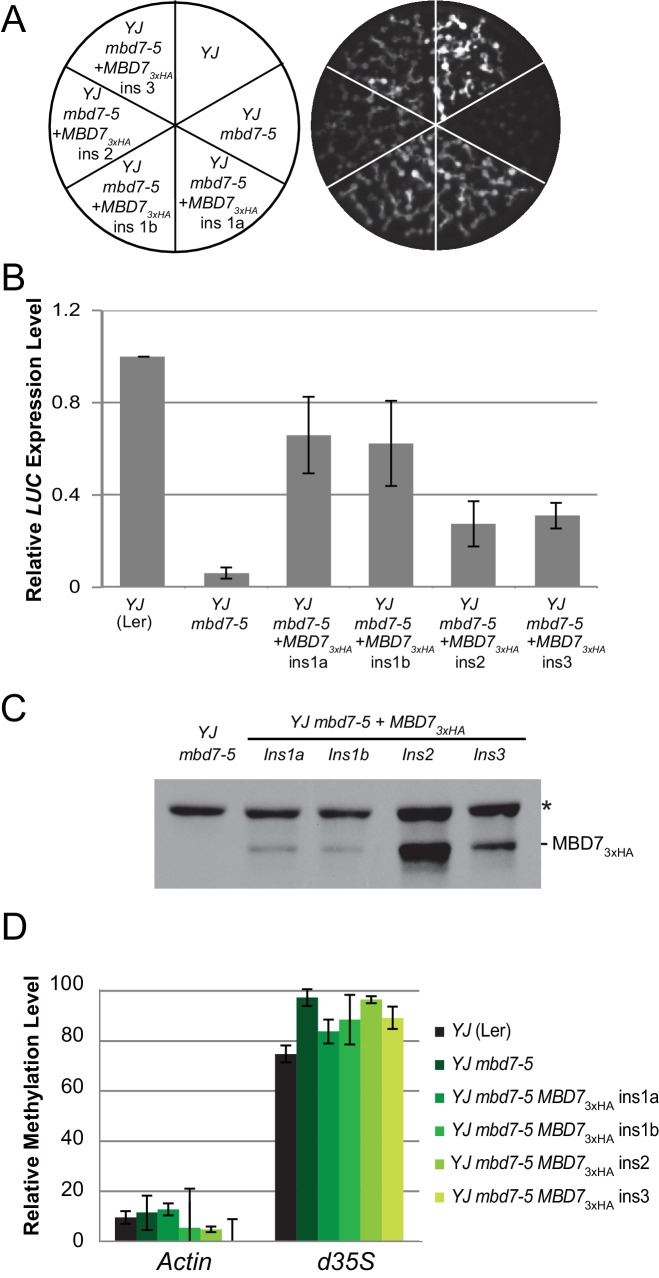

Genetic uncoupling of the hyper-methylation and LUC expression phenotypes at the YJ reporter

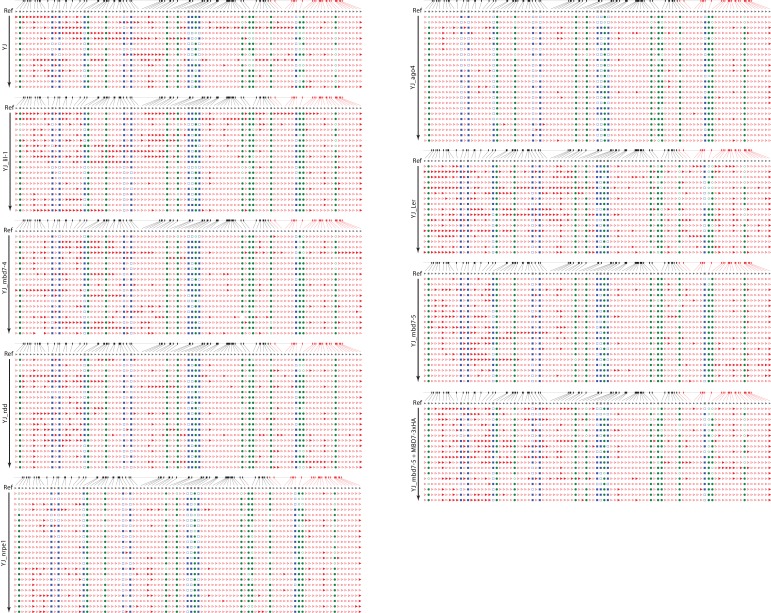

Given the limited changes in DNA methylation observed at the LUC reporters in the lil and mbd7 mutants (especially compared to the striking reduction in LUC expression), we sought to better understand how alterations in DNA methylation influence LUC expression at the YJ reporter. We therefore manipulated the methylation pattern of the d35S promoter using known DNA methylation mutants and then assessed the effect on LUC expression. We chose two strong RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) mutants, ago4 and nrpe1, and the triple demethylase mutant, rdd. Unfortunately, the T-DNAs in these mutants have significant sequence homology with the d35S promoter in the YJ transgene (Supplementary file 1A). Thus, to specifically assess DNA methylation at the d35S promoter driving the LUC gene, without interference from the 94% identical d35S promoter driving NPTII expression (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C,E) or the similar d35S promoters present in the T-DNA insertion mutant backgrounds, traditional bisulfite conversion assays coupled with Sanger sequencing were conducted. For comparison, a full set of alleles in the Col ecotype (lil-1, mbd7-4, ago4-6, nrpe1-11, and rdd) and the complementation data set in the Ler ecotype, all in the YJ rdr6-11 background, were included.

First, we compared results from traditional bisulfite sequencing in the lil and mbd7 mutants with those from MethylC-seq. The DNA methylation levels observed at the 35S promoter by traditional bisulfite sequencing are represented in browser track format (Figure 5A and Supplementary file 1D: YJ_tradBS_WigTracks) and show similar patterns of methylation in the lil and mbd7 mutants when compared to the MethylC-seq data (Figure 4C,D), in that hyper-methylation (primarily in the CG and CHG contexts) was detected at the 3’ end of the promoter (Figure 5A,B). Also consistent with the MethylC-seq data, the increased methylation observed in the mbd7-5 mutant was restored to a more wild-type level upon introduction of the pMBD7::MBD7-3xHA transgene (Figure 5A,B). These findings demonstrate that the two methods of bisulfite sequencing gave similar results. However, unlike the MethylC-seq data (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C,E), the traditional bisulfite sequencing definitively shows that the changes in DNA methylation observed in the lil and mbd7 mutants occur at the 35S promoter driving LUC expression. Furthermore, the traditional bisulfite sequencing offers the added benefit of determining whether the average percent methylation across the 35S promoter represents a uniform distribution of methylation or a bimodal distribution (i.e., some promoters showing high methylation levels and others showing low methylation levels). These analyses revealed a uniform distribution of methylation at the YJ reporter (Figure 5—figure supplement 1). Thus, it does not appear that there is a significant population of fully unmethylated (or even specifically 3’ unmethylated) 35S promoters that give rise to the observed LUC expression.

Figure 5. Genetic uncoupling of the DNA methylation and LUC expression phenotypes at the YJ reporter.

(A) Diagram of the YJ transgene indicating the region examined by traditional bisulfite sequencing (631–1004). DNA methylation tracks show the DNA methylation level (0–1, where 1 = 100% methylated) in the CG (green), CHG (blue) and CHH (red) sequence contexts. The tracks represent the average methylation at each position. The number of clones per genotype is indicated in parentheses to the left of each track. The orange bars below the methylation tracks denote regions that produce 24-nt siRNA clusters. The dashed horizontal lines spanning the methylation tracks are set relative to the maximal CG methylation at the 3’ end of the d35S promoter in the YJ reporter to facilitate visual assessment of the changes in DNA methylation in the mutant backgrounds. (B) Quantification of the average percent methylation across the second 35S promoter (631–1004) or a shorter region at the 3’ end of the 35S promoter (923–1004) within the YJ transgene in the lines presented in (A). The number of cytosines in each sequence context within the quantified regions is indicated in parentheses. Note that these numbers differ from those presented in Figure 4 since the traditional bisulfite sequencing only captures methylation on one strand. (C) Luciferase luminescence of 10-day-old seedlings as diagramed on the left. (D) Quantification of LUC transcript levels by RT-qPCR. LUC transcript levels were normalized to UBIQUITIN5 with the expression level of LUC in the YJ control set to one. Error bars indicate the standard deviation from two biological replicates.

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Traditional bisulfite sequencing at the YJ reporter.

We next determined the DNA methylation patterns and LUC expression levels at the YJ reporter in mutants affecting de novo DNA methylation (ago4 and nrpe1) or DNA demethylation (the triple demethylase mutant, rdd). These analyses suggest that the hyper-methylation at the 3’ end of the d35S promoter and LUC silencing phenotypes can be genetically uncoupled. At the level of DNA methylation, decreases in non-CG methylation were observed in the ago4-6 and nrpe1-11 mutants predominantly at regions of the promoter producing large amounts of 24-nt siRNAs, as predicted for components of the RNA-directed DNA methylation pathway (Figure 5A; ‘24-nt siRNA clusters’). Conversely, all three mutants (ago4-6, nrpe1-11 and rdd) showed a hyper-methylation phenotype similar to that observed in the lil and mbd7 mutants at the 3’ end of the 35S promoter (Figure 5A,B and Figure 5—figure supplement 1). These findings are consistent with: (1) previously identified genetic connections between LIL, MBD7 and ROS1 (Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2015; Won et al., 2012), and (2) studies showing that mutants affecting the establishment of DNA methylation (including ago4 and nrpe1) cause down-regulation of ROS1 (He et al., 2011) via a methylation sensor element in the ROS1 promoter (Williams et al., 2015; Lei et al., 2015). Notably, although the ago4-6, nrpe1-11 and rdd mutants exhibit similar hyper-methylation phenotypes in the CG and CHG contexts at the 3’ end of the 35S promoter, LUC expression is much higher in the ago4 and nrpe1 mutants than in the rdd mutant (Figure 5C,D). While compensatory effects on gene expression due to decreased non-CG methylation at other regions of the d35S promoter in the ago4 and nrpe1 mutants cannot be fully excluded, these findings suggest that the hyper-methylation at the 3’ end of the d35S promoter region alone is not sufficient to cause gene silencing. Taken together, these analyses reveal that at the YJ reporter the MBD7 complex can regulate gene expression in a manner that is largely downstream of DNA methylation.

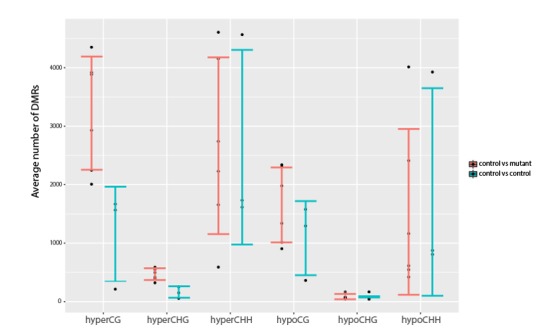

Genome-wide profiling shows that mbd7 and lil mutants have minimal effects on DNA methylation

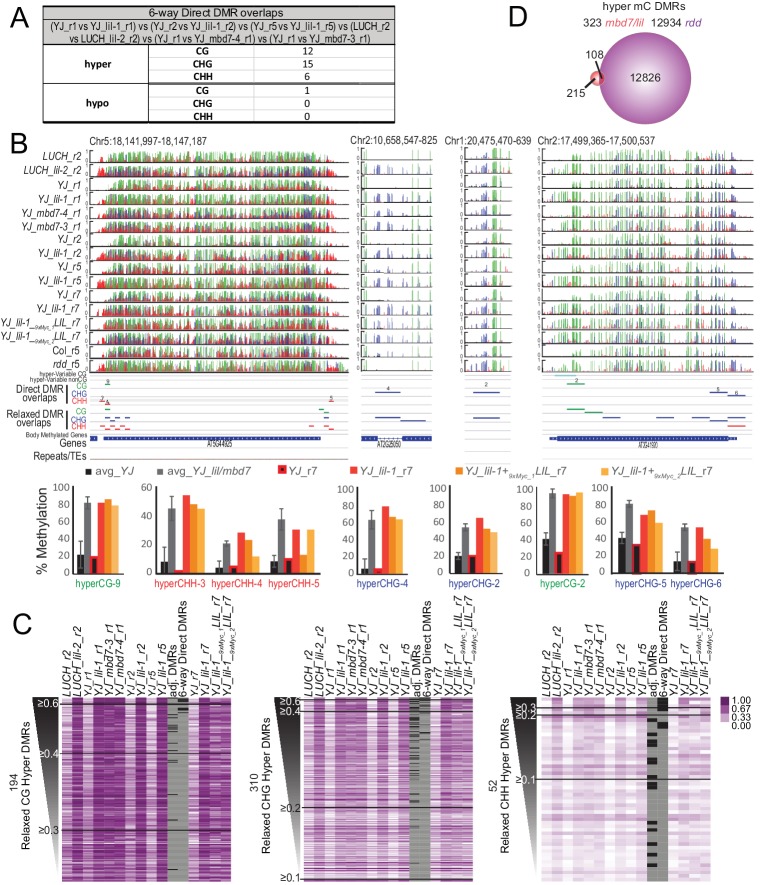

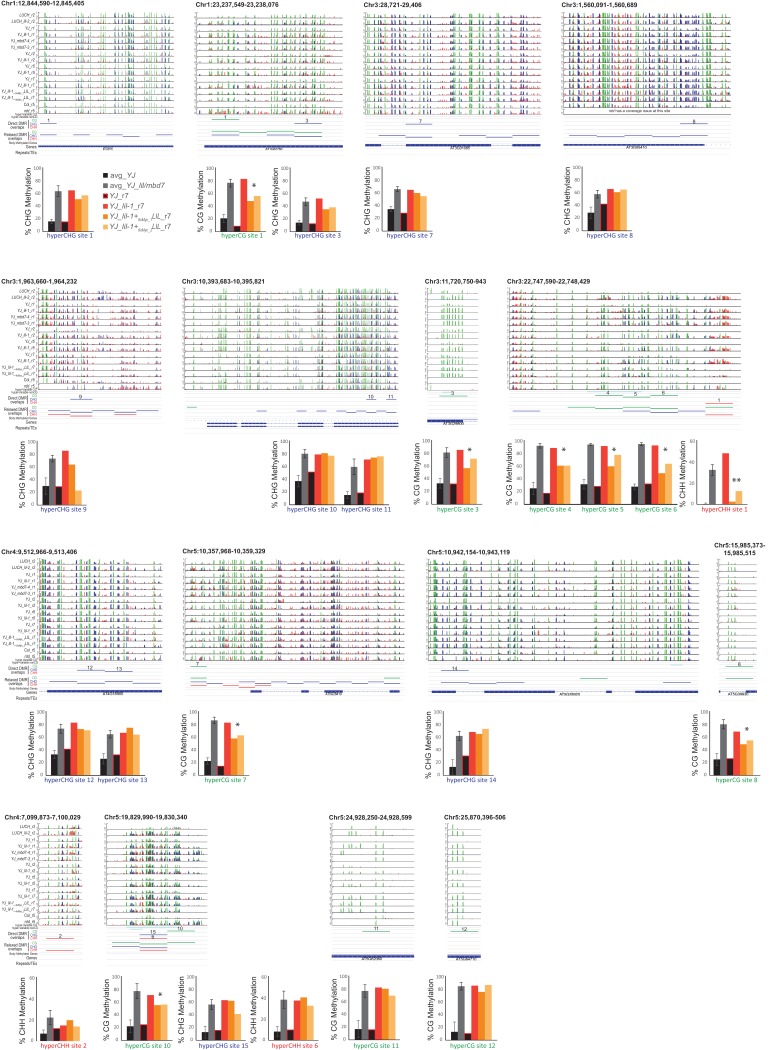

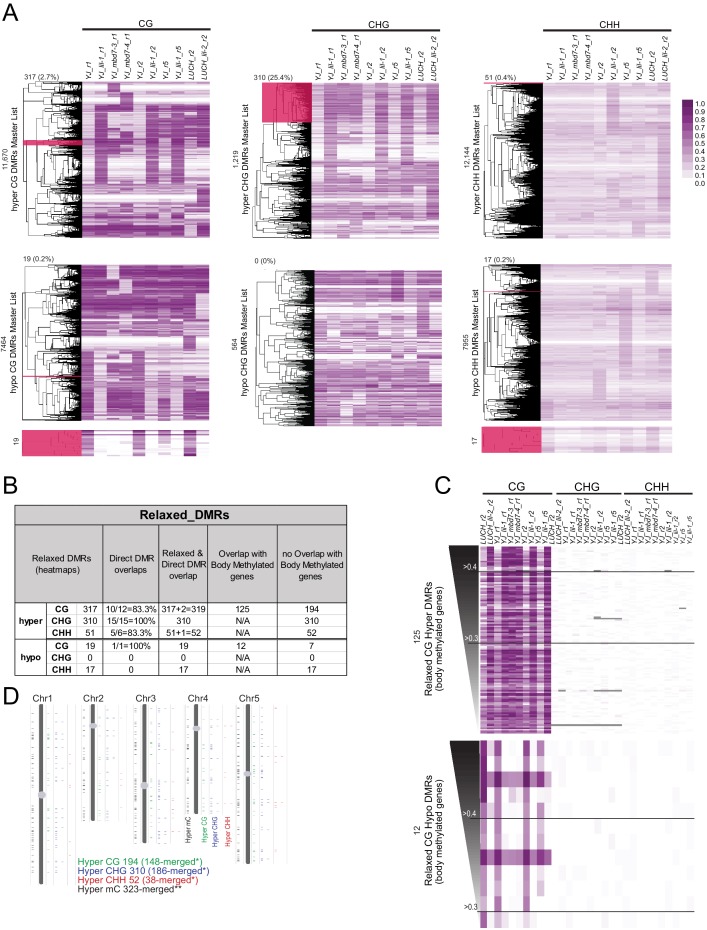

To investigate the role of the MBD7 complex in regulating DNA methylation and to further characterize the relationship between this protein complex and other pathways known to regulate DNA methylation, bisulfite sequencing experiments were conducted. Specifically, the MethylC-seq method (Urich et al., 2015) was employed to determine the methylation profiles of paired sets of mutant and control lines at an average of ~30x coverage with ≥97% conversion rates (Supplementary file 1E and 1F). Altogether, methylation was profiled in two alleles of LIL (lil-1 and lil-2 in the YJ and LUCH backgrounds, respectively), two alleles of MBD7 (mbd7-3 and mbd7-4, both in the YJ background), and the triple DNA demethylase mutant (rdd introgressed into the Col background (Penterman et al., 2007)). In addition, three biological replicates of lil-1 (lil-1_r1, lil-1_r2, and lil-1_r5), each with their own controls, were profiled (Supplementary file 1E). Using this MethylC-seq data, differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were called using methods very similar to those described in Stroud et al. (2013). In both DMR calling pipelines, an initial set of DMRs were called using the same requirements: an absolute change in methylation of ≥40% for CG, ≥20% for CHG, and ≥10% for CHH with an FDR < 0.01 between the mutant and control samples across 100 bp, non-overlapping regions of the genome. However, the two methods used analogous, though not identical, approaches to account for natural variation in DNA methylation, which is known to occur even amongst siblings of the same ecotype (Schmitz et al., 2011; Becker et al., 2011). While Stroud et al. (2013) sequenced three biological replicates of a wild-type sample and only included DMRs observed between a given mutant and all three wild-type controls, we instead included a control sample for each biological replicate and/or each mutant allele and then only included DMRs conserved between these replicates. Although thousands of DMRs were identified in each of the lil-1 and mbd7 datasets, mostly in the CG and CHH contexts (Supplementary file 2A), the vast majority of these DMRs were not in common between the different alleles or even between biological replicates (Supplementary file 2B-F, see orange highlighted comparisons). Indeed, when the DMRs from the three lil-1 replicates were compared with the DMRs identified in lil-2, mbd7-3 and mbd7-4, only 33 hyper and one hypo DMRs remained (Figure 6A, Supplementary file 2F; 6-way DMR overlaps, and Supplementary file 2G-J), and these regions converged on 20 loci (19 displayed hyper-methylation and one showed hypo-methylation [Figure 6B and Figure 6—figure supplement 1]). Thus, while numerous DMRs can be identified between any single mbd7 or lil mutant vs. control (Supplementary file 2A), very few genomic targets show consistent changes in DNA methylation upon disruption of the MBD7 complex, indicating that these changes may represent natural variation in methylation.

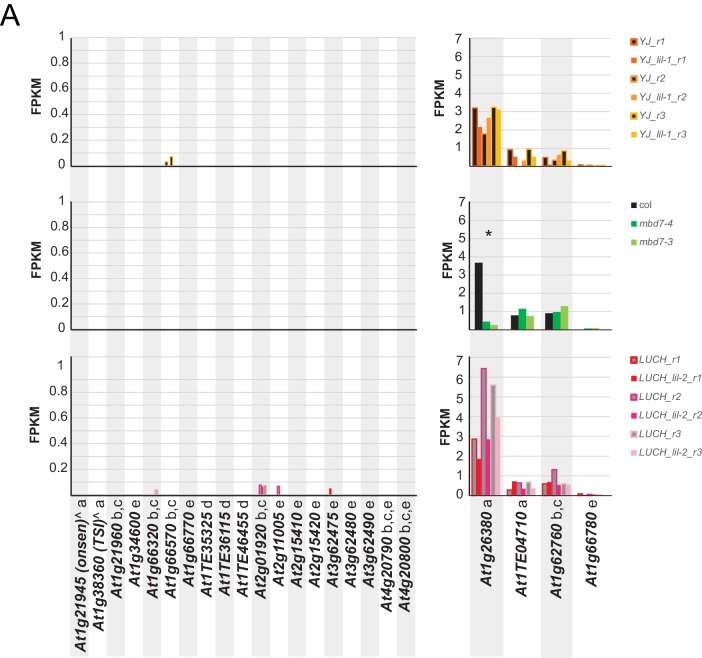

Figure 6. Genomic DMRs identified in the lil and mbd7 mutants.

(A) Table summarizing DMRs that overlap among all the lil and mbd7 datasets ‘6-way Direct DMR overlaps’. (B) Screenshots showing the DNA methylation levels (0–1, where 1 = 100% methylated, with CG, CHG and CHH contexts in green, blue and red, respectively) at several DMRs in the genotypes indicated on the left. Below the DNA methylation tracks are the following additional features: (1) hyper-variable DMRs in the CG and non-CG contexts from Schmitz et al. (2011), (2) hyper DMRs in the CG, CHG and CHH contexts that overlap amongst all the lil and mbd7 datasets (‘Direct DMR overlaps’), (3) an expanded set of DMRs identified as detailed in (C) and in Figure 6—figure supplement 2 (‘Relaxed DMR overlaps’), (4) body methylated genes as described in Takuno and Gaut (2012), and (5) TAIR10 annotated genes and repeats. The percent methylation over each DMR is quantified in the bar graphs below. The average levels of methylation in controls vs. the mbd7 and lil DMRs are shown in black and grey, respectively. The error bars represent the standard deviation to capture the level of variation between samples. The levels of methylation in the MycLIL complementation data set are also indicted. (C) Heatmaps showing the methylation levels at DMRs called using a relaxed set of criteria (e.g., DMRs where all of the samples show hyper-methylation in the CHG context, but some are slightly below the required 20% change cutoff). The hyper DMRs are ranked from most to least robust and changes in methylation ≥0.6, ≥0.4, ≥0.3, ≥0.2 and≥0.1 are indicated. The DMRs indicated in panel A (‘6-way_Direct DMRs’) and the less stringent DMRs that map to genomic regions adjacent to the direct DMRs (‘adj. DMRs’) are demarcated by black boxes on the heatmaps. (D) Venn diagram showing the hyper mC DMRs (see Materials and methods) shared between the mbd7 and lil mutants (red) that overlap with DMRs identified in the rdd triple mutant (purple).

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. Visualization and quantification of DNA methylation at the direct overlap DMRs.

Figure 6—figure supplement 2. Identification of a more relaxed set of DMRs conserved amongst the mbd7 and lil datasets.

Figure 6—figure supplement 3. Complementation of the lil-1 phenotype with 9xMyc-LIL.

Figure 6—figure supplement 4. Gene expression at previously characterized loci in mbd7 and lil mutants.

Acknowledging that requiring a direct overlap in DMRs between all six samples is quite stringent, a more relaxed set of DMRs was generated to determine whether a larger number of genomic targets dependent on the MBD7 complex would emerge. For these analyses, the methylation levels across the totality of DMRs identified in any of the various lil and mbd7 mutants were first determined (Supplementary file 2K-P; MasterDMRLists). DMRs that behaved similarly in all samples were then identified via a clustering analysis and filtered to remove body-methylated genes, which as a group are known to display a higher degree of natural variation in DNA methylation levels (Schmitz et al., 2011) (Supplementary file 2Q-U; Relaxed_DMR_lists and Figure 6—figure supplement 2). This yielded a set of 194 CG hyper DMRs, 310 CHG hyper DMRs and 52 CHH hyper DMRs (Figure 6C and Figure 6—figure supplement 2). Notably, many of these hyper DMRs are located adjacent to the original set of 33 high stringency DMRs (Figure 6C; high stringency DMRs from Figure 6A and DMRs located adjacent to these regions are indicated with black bars in the heatmaps). This demonstrates that both methodologies are converging on a similar, small set of genomic loci that are hyper-methylated in both mbd7 and lil mutants. When changes in methylation regardless of the sequence context were combined, these DMRs converged on 323 genomic regions that are distributed across the five chromosome arms (Figure 6—figure supplement 2D and Supplementary file 2V and 2W; hyper_mC_merged). Notably, only a third of these regions overlap with regions hyper-methylated in the rdd mutant background, representing a tiny fraction of the total rdd targets (Figure 6D). Thus, although there are clear genetic connections between MBD7, LIL and ROS1 in the regulation of several transgenic reporters (Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2015), as a general rule, the demethylation pathway does not appear to function in a manner that depends solely on either MBD7 or LIL.

To further investigate the functional relevance of the mbd7 and lil hyper DMRs, we determined whether the observed increases in DNA methylation could be complemented by re-introduction of a functional LIL protein. Using stable transgenic plant lines expressing an N-terminal Myc-tagged LIL protein under the control of its endogenous promoter (pLIL::9xMyc-LIL), complementation was first confirmed by assessing the LUC expression and DNA methylation phenotypes at the YJ reporter (Figure 6—figure supplement 3). Then, the global patterns of DNA methylation in the YJ_r7 and YJ lil-1_r7 parental lines, as well as two sibling complementing lines (YJ_lil-1+ 9xMyc_1LIL and YJ_lil-1+ 9xMyc_2LIL), were determined using the MethylC-seq method (Supplementary file 1E). In general, the complementing lines more closely resemble the YJ lil-1_r7 mutant line than the YJ_r7 control (Figure 6C), suggesting minimal complementation overall. Although the possibility of partial complementation at some loci cannot be excluded, even at the most robust set of DMRs, only 1 of 33 DMRs returned to control levels of DNA methylation (Figure 6—figure supplement 1, hyper-CHH site 1. Of the remaining sites, eight showed consistent but modest decreases in DNA methylation (indicated by a single asterisks in Figure 6—figure supplement 1). However, 5 of these directly overlapped with known hyper-variable regions (Schmitz et al., 2011). These findings demonstrate that re-introduction of LIL is not able to efficiently correct the observed hyper-methylation defects, which further supports the notion that these changes represent variation in methylation rather than a direct effect of the lil mutation.

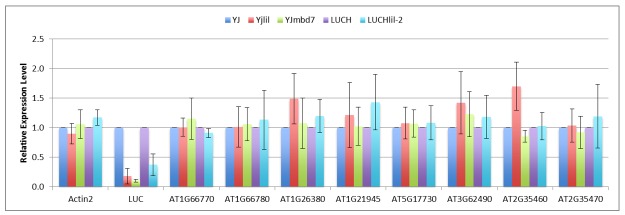

Transcriptome profiling of mbd7 and lil mutants

To further investigate the role of the MBD7 complex in gene regulation, we assessed the effects of the lil and mbd7 mutants on gene expression by transcriptome profiling. Similar to the approach taken for the DNA methylation profiling, two alleles of LIL (lil-1 and lil-2 in the YJ and LUCH backgrounds, respectively) and two alleles of MBD7 (mbd7-3 and mbd7-4) were compared to their corresponding controls (Supplementary file 3). Among these mutants, no overlapping mis-regulated genes were identified between the lil and mbd7 alleles (Supplementary file 3) and only one of the genes previously identified as a target of MBD7 complex (i.e. down-regulated genes associated with hyper DMRs in the Columbia ecotype (Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b; Qian et al., 2014; Duan et al., 2017; Qian et al., 2012)) was consistently down-regulated in any of the mutants tested (Figure 6—figure supplement 4). As some common alleles of mbd7 were used in these studies and similar developmental stages were utilized, the factors leading to the differing results remain unclear. However, perhaps differences in growth conditions and/or the differing sensitivities and normalization procedures of the assays used to assess gene expression levels (i.e. mRNA-seq vs qPCR), as well as the already low expression levels of the down-regulated genes under our conditions, represent contributing factors (Figure 6—figure supplement 4).

Given the absence of detectable endogenous targets transcriptionally regulated by the MBD7 complex, it is likely that this complex functions redundantly with other MBD-ACD complexes and/or is required only under specific conditions. Nonetheless, our findings demonstrate that this complex has the ability to regulate gene expression in a manner largely downstream of DNA methylation at LUC reporters. Firstly, we found that loss of the MBD7-LIL complex results in the silencing of these reporter constructs with minimal changes in DNA methylation. Secondly, we demonstrated that hyper-methylation at the 3’ end of the d35S promoter in the YJ reporter does not appear to be sufficient to cause gene silencing (Figure 5). As such, the MBD7 complex joins a small number of factors including MOM1, MORC1, MORC6, ATXR5, and ATXR6, that can act primarily downstream of DNA methylation. However, unlike these other downstream effectors, which function to reinforce gene silencing, MBD7 and LIL represent the first anti-silencing complex placed downstream of DNA methylation, functioning to enable gene expression despite high levels of promoter DNA methylation.

Discussion

In this study, we identified two MBD-containing protein complexes and demonstrated a role for the MBD7 complex in promoting the expression of methylated transgenes. Furthermore, we found that while mutations in components of the MBD7 complex led to increased DNA methylation at the d35S promoter driving LUC expression, this methylation alone did not appear to be sufficient to cause LUC silencing. These findings, along with genome-wide analyses showing that only a small number of loci displayed a consistent hyper-methylation phenotype in mbd7 and lil mutants, support an alternative hypothesis regarding the role of the MBD7 complex. Rather than functioning as part of the DNA demethylation pathway, as has been previously hypothesized (Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2015), our results suggest that the MBD7 complex may function in a manner largely downstream of DNA methylation. As very few proteins have been characterized that function downstream of DNA methylation, further characterization of this complex offers the potential to gain much needed insight into the mechanisms by which DNA methylation affects gene expression. Below, we summarize the current knowledge regarding the function and composition of MBD complexes from this and several previous studies (Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2014; Qian et al., 2014, 2012; Li et al., 2012). In addition, we highlight what is known about other factors that influence gene regulation downstream of DNA methylation.

The MBD7 complex and the DNA demethylation machinery

The first anti-silencing factors discovered in Arabidopsis were a family of DNA glycosylases that recognize and remove methylated cytosine bases, leading to the release of gene silencing in a locus-specific manner (Zhu, 2009). Recently, additional anti-silencing factors have been identified through genetic screens and biochemical approaches revealing unanticipated connections between proteins that bind methylated DNA (MBD7 [Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2015] and ROS4/IDM1 [Qian et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012]) and proteins with alpha crystallin domains (ACDs) (LIL/IDL1/IDM3 [Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b] and ROS5/IDM2 [Wang et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2014; Qian et al., 2014]) in regulating the expression of methylated genes. As part of these screening efforts, the methylation status of one endogenous locus (At1g26400) and four reporter transgenes have been characterized. In all these cases, similar changes in DNA methylation and gene expression were observed in mutants of the demethylation machinery (either ros1 single, or rdd triple mutants) or the MBD7 complex (mbd7, lil, ros4, and ros5 mutants). Given this consistent genetic connection, previous studies have concluded that the various MBD and ACD proteins function in a common demethylation pathway with ROS1 to prevent hyper-methylation and enable gene expression, despite the fact that only modest increases in DNA methylation were observed (Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2014; Qian et al., 2014, 2012; Li et al., 2012). Here we show that the observed hyper-methylation and gene expression defects can be genetically uncoupled at the YJ reporter since LUC expression levels remain high in ago4 and nrpe1 mutants despite hyper-methylation patterns that are identical to those observed in mbd7, lil, or rdd mutant backgrounds. Furthermore, we show that on a genome-wide scale, the genetic connections between MBD7, LIL, and the demethylase machinery are no longer observed. Not only are there very few loci that show a consistent hyper-methylation phenotype across the various mbd7 and lil datasets, but these loci represent a tiny fraction of the hyper-methylated loci in rdd mutants. Thus, while we cannot fully rule out a role for the MBD7 complex as a highly locus-specific regulator of the DNA demethylation pathway, nor do we know the extent to which other MBD-ACD complexes might function redundantly with the MBD7 complex and mask its role at endogenous targets and/or connections with the demethylase machinery, we currently favor a model based on our extensive transgene analysis in which the MBD7 complex functions largely downstream of DNA methylation to promote gene expression through a yet unknown mechanism.

Further support for the notion that the primary function of the MBD7 complex is downstream of DNA methylation comes from a comparison of the reporter transgenes used to identify components of this complex. While all these reporters contained 35S promoters driving the expression of genes that are repressed in mutants of the MBD7 complex, no commonalities in the hyper-methylated regions were identified. For the YJ and LUCH reporters, hyper-methylation is restricted to the 3’ end of the d35S promoter driving LUC expression (Figures 4C and 5A). Interestingly, this hyper-methylation corresponds to two TGACG motifs previously shown be bound by a tobacco protein in a methylation sensitive manner (Kanazawa et al., 2007). However, this same region does not appear to be hyper-methylated in the d35S promoters present in the SUC2 or NPTII reporters. At the SUC reporter the hyper-methylation is instead observed at the 5’ end of the 35S promoter (Lang et al., 2015) and the hyper-methylation at the NPTII reporter is downstream of the NPTII gene, in the NOS terminator region (Wang et al., 2015). Thus, as there is no clear consensus region that is hyper-methylated amongst these reporters, we posit that the hyper-methylation patterns may represent indirect effects caused by disruption of the MBD7 complex rather than locus specific regulation of DNA methylation.

Composition of MBD and ACD/HSP20-like complexes

In the present study, MBD5 and MBD7 were found to associate with distinct sets of alpha crystallin domain (ACD)-containing proteins. Furthermore, MBD7 and its associated proteins, but not MBD5, were found to suppress the silencing of methylated luciferase (LUC) reporter transgenes, suggesting different roles for the MBD5 and MBD7 complexes. In addition to these purifications, each component of the MBD7 complex (MBD7, ROS4/IDM1, LIL/IDL1/IDM3, and ROS5/IDM2) has now been individually affinity purified and the co-purifying factors and their approximate relative abundances have been determined using Mass Spectrometry (Figure 2—figure supplement 1 and refs [Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b]). With the exception of our 3xHA tagged MBD7 purification, all these Mass Spectrometry experiments yielded peptides corresponding to all four factors. However, in Lang et al. (2015) the purification of MBD7 yielded the most peptides matching LIL/IDM3, with relatively fewer hits to IDM1 and ROS5/IDM2, suggesting there may be a stable sub-complex of MBD7 and LIL/IDM3 in addition to the larger MBD7 complex. Taken together, these data demonstrate the existence of multiple MBD complexes, expanding the number of known MBD-ACD complexes, and revealing a functional difference between MBD5 and MBD7 complexes.

As a complement to the affinity purifications, many of the pair-wise interactions between the various MBD and ACD proteins have been determined using Y2H assays (Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2014; Qian et al., 2014). In several cases, subdomains important for these interactions have been mapped, revealing additional insights into the organization of these protein complexes. For example, the two ACD domain-containing proteins (LIL/IDL1/IDM3, and ROS5/IDM2) interact directly with each other (Li et al., 2015b), with MBD7 (Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2015) and with ROS4/IDM1(Li et al., 2015b; Zhao et al., 2014; Qian et al., 2014), whereas MBD7 and ROS4/IDM1 fail to show a direct interaction (Lang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015b). This suggests the ACD-domain proteins may function to bridge the association between MBD7 and ROS4/IDM1. Furthermore, the interaction domains between ROS4/IDM1 and either LIL/IDL1/IDM3 or ROS5/IDM2 map to different regions of the ROS4/IDM1 protein (Li et al., 2015b; Zhao et al., 2014) suggesting that both these ACD domain proteins could interact with ROS4/IDM1 at the same time. Similarly, Lang et al. and this study show that two adjacent regions in MBD7 are each sufficient to interact with LIL/IDL1/IDM3 (Figure 2—figure supplement 1). Thus, one can envision scenarios in which the two ACDs could compete for binding to the interaction domains in ROS4/IDM1 or MBD7, or cooperatively bind given their affinities for each other. Beyond these pair-wise interactions, Zhao et al. (2014) demonstrated that ROS5/IDM2 forms higher-order structures that migrate at ~670 kDa after gel filtration, consistent with a 16-mer complex. This finding demonstrates that at least ROS5/IDM2, and possibly other ACD proteins, have the ability to oligomerize in a manner similar to canonical HSP20 proteins (Scharf et al., 2001). Although it remains unclear which interactions and structural features are required for the function of the MBD7 complex, the fact that loss of any component abolishes activity suggests a close tie between structure and function.

Regulation of gene expression downstream of DNA methylation

While our understanding of the mechanisms through which gene expression is regulated downstream of DNA methylation remains quite limited, several factors have been shown to release gene silencing while having minimal effects on DNA methylation. Many of these factors, including MORC1, MORC6, ATXR5 and ATXR6, influence chromatin organization on a gross scale, such that loss of these factors results in de-compaction of peri-centromeric heterochromatin (i.e., chromocenters) (Moissiard et al., 2012; Jacob et al., 2009) and the selective up-regulation of genes and transposons located within these regions (Moissiard et al., 2012; Jacob et al., 2009). On the other hand, MOM1 appears to act on a finer scale to influence gene expression without significantly perturbing chromatin compaction (Mittelsten Scheid et al., 2002; Probst et al., 2003). In mbd7 and lil mutants, no obvious defects in chromocenter formation were observed, suggesting the MBD7 complex may act at a local level to enable the expression of methylated genes, perhaps antagonizing the function of MOM1, which has been shown to regulate expression at the LUCH reporter (Won et al., 2012). Alternatively, since there are several other MBD proteins known to bind methylated DNA (e.g., MBD5 and MBD6 (Zemach and Grafi, 2003; Scebba et al., 2003; Ito et al., 2003; Zemach et al., 2005)) and several other ACD proteins closely related to LIL/IDL1/IDM3 and ROS5/IDM2 (Scharf et al., 2001) (Figure 1—figure supplement 3), these factors may act redundantly to regulate chromatin structure on a more global level.

Moving forward, it will be important to continue exploring the composition, dynamics, and regulatory roles of the various MBD and ACD complexes, and to begin investigating the genetic relationships between these complexes. Such experiments have the potential to uncover genomic targets regulated by these complexes in a redundant manner, and perhaps identify specific roles for these complexes during development. Finally, it will also be important to assess the relative contributions of the enzymatic and structural features associated with these complexes in modulating the local chromatin environment. This will provide further mechanistic insights into how different MBD and ACD complexes function together to regulate the expression of methylated regions of the genome.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and transgenic lines

Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia-0 (Col) and Landsberg erecta (Ler) ecotype plants were used in the present study. The LUC-based reporters LUCH (Won et al., 2012) and YJ (Li et al., 2016) are in the rdr6-11 mutant background (Peragine et al., 2004) in all lines used for this study and were originally generated in the Col background. The lil-1, ros4-2 and ros4-3 mutants were recovered from an EMS screen in the YJ background while the lil-2 mutant was recovered from a T-DNA screen in the LUCH background. The following additional mutants were introduced into the YJ background (Col ecotype) by crossing: mbd7-3 (GABI_067_A09) (Kleinboelting et al., 2012) (formerly named mbd7-1 in (Li et al., 2015b) and renamed to avoid duplicate allele names with other publications (Lang et al., 2015)), mbd7-4 (SALKseq_080774) (unpublished), mbd5-3 (SAILseq_750_A09) (unpublished), ros5-4 (SALK_138229 also kown as idm2-2 (Qian et al., 2014; Alonso et al., 2003), ago4-6 (Alonso et al., 2003), nrpe1-11 (Pontier et al., 2005), and ros1-3 dml2-1 dml3-1 (Penterman et al., 2007). Finally, mbd5-1 (CSHL_ET8226) (Sundaresan et al., 1995) and mbd7-5 (GT_5_107435) (Sundaresan et al., 1995), which are in the Ler ecotype, were crossed into the YJ reporter that was introgressed into the Ler ecotype through 5 backcrosses.

To generate the MBD5-3xFlag, MBD7-3xHA, and MBD7-3xFlag transgenes, the genomic regions of MBD5 and MBD7, including their endogenous promoter regions, were amplified by PCR using the primer pairs JP3845/JP3891 and JP5523/JP5525, respectively (Supplementary file 4). The PCR products were cloned into the pENTR/D/TOPO vector per manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). A carboxy terminal 3xFlag or 3xHA tag (described in [Law et al., 2011]) was added at an AscI site present in the pENTR/D/TOPO backbone downstream of the MBD5 or MBD7 inserts. The resulting plasmids were recombined into a modified version of the pEG302 plasmid as described in Johnson et al. (2008) using a Gateway LR clonase kit (Invitrogen) and transformed into Col or YJ mbd7-5 plants using the floral dip method.

To generate the pLIL:9xMyc-LIL transgene, the genomic region of LIL encompassing the promoter and coding sequence up to the stop codon was amplified by PCR using primers HSP20-proF1 and HSP20-R3 from Col genomic DNA. The genomic fragment was cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO (Invitrogen, K2400-20) to result in pENTR/D-TOPO-LIL. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the Stratagene kit XL II with this clone using primers HSP20-mut3 and HSP20-mut4 to introduce a KpnI site near the start codon of LIL. A 9xMyc-BLRP fragment was released from the pCR2.1::KpnI 9×Myc-BLRP plasmid (Law et al., 2010b) by KpnI digestion and cloned into the KpnI site of the pENTR/D-TOPO-LIL plasmid to result in an N-terminal fusion of 9xMyc to LIL. The insert in the entry vector was then recombined into pGWB204 (Nakagawa et al., 2007) using a Gateway LR Clonase kit (Invitrogen, 11791–019) and transformed into YJ lil-1 plants using the floral dip method.

LUCH and YJ genetic screens

Mutant populations in the YJ and LUCH backgrounds were generated via ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) or T-DNA mutagenesis, respectively. For EMS mutagenesis, 1 ml of seeds (around 10,000 seeds) were washed with 0.1% Tween 20 for 15 min, treated with 0.2% EMS for 12 hr and washed three times with 10 ml water for 1 hr with gentle agitation. For T-DNA mutagenesis, pEarleygate303 was modified to remove the Gateway cassette then transformed into the LUCH line. Mutants with lower LUC activity, based on LUC live imaging, were isolated in the M2 generation of the EMS population and the T2 generation of the T-DNA population. The isolated mutants were backcrossed to the respective parental lines two times before further analysis.

Mapping of the ros4-2 and ros4-3 mutations

The YJ ros4-2 and YJ ros4-3 mutants were isolated from the YJ EMS screen and crossed to the corresponding YJ lines in the Ler background to generate the F2 mapping populations. For YJ ros4-2, 28 F2 plants with reduced LUC activity were used for rough mapping, and the mutation was linked to the center of the upper arm of chromosome 3. SSLP and dCAPS markers were designed using identified polymorphisms between the Col and Ler accessions (http://arabidopsis.org/browse/Cereon/index.jsp). Fine mapping narrowed the region to a 280 kb window spanning the K15M2, F4B12, K7L4, MJK13, MQD17 and MSJ11 BAC clones. Candidate gene sequencing uncovered a G-to-A mutation that introduced a premature stop codon in the seventh exon of At3g14980, and the mutation was subsequently referred to as ros4-2. For YJ ros4-3, 27 F2 plants with reduced LUC activity were used for rough mapping, and linkage to the same mapping region of ros4-2 was observed. Sequencing of At3g14980 revealed a G-to-A mutation that introduced a premature stop codon in the second exon.

Mapping of the lil-1 and lil-2 mutations

The YJ lil-1 and LUCH lil-2 mutants were isolated from the YJ EMS screen and the LUCH T-DNA screen, respectively, and crossed to the corresponding LUC lines in the Ler background to generate the F2 mapping populations. For YJ lil-1, 32 F2 plants with reduced LUC activity were used for rough mapping, and the mutation was linked to the center of the upper arm of chromosome 1. SSLP and dCAPS markers were designed using identified polymorphisms between the Col and Ler accessions (http://arabidopsis.org/browse/Cereon/index.jsp). Fine mapping narrowed the region to a 160 kb window spanning the F5M15, F2D10 and F9H16 BAC clones. Candidate gene sequencing uncovered a G-to-A mutation in the splice acceptor site of At1g20870, and the mutation was subsequently referred to as lil-1. For LUCH lil-2, 27 F2 plants with reduced LUC activity were used for rough mapping, and linkage to the same mapping region of lil-1 was observed. Sequencing of At1g20870 revealed a C-to-T mutation that introduced a premature stop codon in the first exon.

Yeast two-hybrid screen

The full-length coding sequence of LIL was amplified with primers HSP20T7fl F and HSP20T7fl R and cloned into the bait vector pGBKT7 at the NdeI and BamHI sites to be fused in-frame with the sequence encoding the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (BD). The Arabidopsis cDNA library cloned into the prey vector pGADT7-RecAB was constructed by Clontech. All experiments using the yeast two-hybrid system were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech, Matchmaker GAL4 Two-Hybrid System 3 and Libraries User Manual, PT3247-1). The bait plasmid pGBKT7-LIL and the prey library DNA were co-transformed into the yeast strain AH109. The resulting progeny were first selected on SD/-Leu/-Trp/-His/-Ade plates then tested for β-galactosidase activity to eliminate false positives. Plasmids harboring positive prey cDNAs were isolated and sequenced to ensure that the cDNAs had been fused in-frame with the sequence encoding the GAL4 AD domain.

To identify the interaction domains, the alpha crystallin/Hsp20 domain of LIL was amplified with primers HSP20T7D1F and HSP20T7D1R and cloned into pGBKT7 as the bait LILD1. The LIL sequence 5’ to the alpha crystallin/Hsp20 domain was amplified with primers HSP20T7N3F and HSP20T7N3R and cloned into pGBKT7 as the bait LILN3. Full-length or truncated MBD5, MBD6 and MBD7 cDNAs were cloned into pGADT7. Full-length MBD5 coding sequence was amplified with primers MBD5ADfl F and MBD5ADfl R; Full-length MBD6 coding sequence was amplified with primers MBD6ADfl F and MBD6ADfl R; Full-length MBD7 coding sequence was amplified with MBD7ADfl F and MBD7ADfl R. The methyl-CpG-binding domain of MBD5 was amplified with primers EcoRI-MBD5d and MBD5d-BamHI and cloned into pGADT7 as prey MBD5d. Similarly, the methyl-CpG-binding domain of MBD6 was amplified with MBD6d-BamHI and EcoRI-MBD6d and cloned into pGADT7 as prey MBD6d. For MBD7, the second methyl-CpG-binding domain, including partial sequence of the third methyl-CpG-binding domain, was amplified with EcoRI-MBD7d2 and MBD7d2-BamHI and cloned into pGADT7 as prey MBD7d2. The third methyl-CpG-binding domain of MBD7 was amplified with EcoRI-MBD7d3 and MBD7d3-BamHI and cloned into pGADT7 as prey MBD7d3. Sequences of primers used in the plasmid construction can be found in Supplementary file 4. Colonies containing both bait and prey plasmids were selected by growing yeast on selective dropout medium lacking Trp and Leu (SD/-Trp/-Leu) at 30°C. They were subsequently plated on selective dropout medium lacking Trp, Leu, Ade and His (SD/-Trp/-Leu/-Ade/-His) and grown at 30°C to test interactions between bait and prey.

Affinity purification and Mass Spectrometry

Affinity purification and Mass Spectrometry of MBD5 and MBD7 were performed largely as described in Law et al. (2010b). Briefly, for each replicate of MBD5, approximately 14 g of flower tissue from MBD5-3xFlag transgenic T4 plants, or from wild type Col plants, were ground in liquid nitrogen. For replicates one and two, the tissue was re-suspended in 75 mL of lysis buffer 1 (LB1: 50 mM Tris pH7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.1% NP-40, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 µg/µL pepstatin, 1 mM PMSF and one protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, 14696200)), while replicate three was re-suspended in 75 mL of low salt lysis buffer 2 (LB2: LB1 replacing 150 mM NaCl with 100 mM NaCl). In all three cases, immunoprecipitation utilized 250 μL of 50% M2 FLAG-agarose slurry (Sigma, A2220) and proteins were eluted from the beads by competition with 3xFLAG peptide (Sigma, F4799).

For replicates one and two of MBD7, approximately 10 or 15 g of flower tissue from MBD7-3xHA transgenic T4 plants or from wild type Col plants, respectively, were ground in liquid nitrogen and re-suspended in either 50 mL of LB1 (replicate 1) or 75 mL of a triton lysis buffer 3 (LB3: LB1 replacing 0.1% NP-40 with 1% Triton X-100) (replicate 2). Immunoprecipitation utilized 250 μL of 50% HA-conjugated slurry (Roche, 11815016001) and proteins were eluted from the beads by competition with HA peptide (Thermo, 26184). For the third replicate of MBD7, approximately 10 g of flower tissue from MBD7-3xFLAG transgenic plants or from wild type Col plants were ground in liquid nitrogen and re-suspended in 50 mL of lysis buffer 1 (LB1). Immunoprecipitation utilized 250 μL of 50% Anti-FLAG M2 Magnetic bead slurry (Sigma, M8823) and proteins were eluted from the beads by competition with 3xFlag peptide (Sigma, F4799). Eluted proteins were TCA precipitated and subjected to Mass Spectrometry as described in Law et al. (2010b).

Luciferase imaging

For Figure 1, Figure 3 and Figure 1—figure supplement 1, seeds were surface-sterilized and planted on half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) media supplemented with 0.8% agar and 1% sucrose then stratified at 4°C for three days. Plants were grown in a growth incubator at 23°C under continuous light. 10-day-old seedlings were used for all of the experiments. Luciferase live imaging was performed as previously described (Won et al., 2012).

For Figure 2 (YJ lines), Figure 5, Figure 2—figure supplement 3, Figure 4—figure supplement 1, and Figure 6—figure supplement 3, seeds were surface-sterilized and planted on Linsmaier and Skoog (LS) media (Caissen, LSP03) supplemented with 0.8% agar, then stratified at 4°C for three days. Plants were grown in a growth incubator at 23°C under short day conditions (8 hr light, 16 hr dark). 10-day-old seedlings were used for all of the experiments. Luciferase live imaging was performed using a CCD camera (Andor, iKon-M 934) and PlantLab software (BioImaging Solutions).

5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine treatment and Luciferase imaging

For 5-Aza-dC (Sigma, A3656) treatment, plants were grown on Murashige and Skoog (MS) media containing 0.8% agar, 1% sucrose and 7 μg/ml 5-Aza-dC for 2 weeks. Luciferase live imaging was performed as previously described (Won et al., 2012).

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

For Figures 1 and 2 (LUCH lines), Figure 3 and Figure 1—figure supplement 1, RNA was extracted from a pool of 10-day-old seedlings using TRI reagent (Molecular Research Center, TR118) and treated with DNaseI (Roche, 04716728001). cDNA was synthesized using RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Scientific, EP0441) and oligo-dT primer (Thermo Scientific, SO131). RT-qPCR was performed on a Bio-Rad C1000 thermal cycler equipped with a CFX detection module using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, 170–0082). For Figure 2 (YJ lines), Figure 5, Figure 2—figure supplement 3, Figure 4—figure supplement 1, and Figure 6—figure supplement 3, RNA was extracted from a pool of 10-day-old seedlings using Zymo Research Quick-RNA Miniprep Kit (Zymo, R1054S). cDNA was synthesized using Applied Biosystems High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, 4368814). RT-qPCR was performed on a Bio-Rad CFX384 Real-Time System using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, 172–5124). Quantification of transgene expression was performed in biological triplicate, unless otherwise indicated. All experiments were conducted per the manufacturers’ instructions. The primers used in the study are listed in Supplementary file 4.

McrBC-PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from a pool of 10-day-old seedlings using the CTAB method (Rogers and Bendich, 1985). Three units of McrBC (New England Biolabs, M0272) were used to treat 200–500 ng of DNA at 37°C for 25 min to overnight. A mock experiment was performed in parallel using DNA that had not been treated with McrBC. Either regular PCR or quantitative PCR using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, 172–5124) was performed to determine the level of methylation. For both regular PCR and qPCR, ACTIN1, which lacks cytosine methylation, was used as the internal loading control. The relative methylation was calculated as 100–100 × 2Ct(mock) - Ct(treated), such that higher relative levels of PCR amplification correspond to higher levels of methylation. The primers used in the study are listed in Supplementary file 4.

Western blotting

Western blot analysis of MBD7-3xHA transgenic lines was performed using 0.1 g of flower tissue. Tissue was mechanically disrupted and homogenized in cold IP buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% Glycerol, 0.1% NP40) with protease inhibitors. The lysate was resolved on a 10% Bis-Tris Criterion XT Gel (Bio-Rad, 345–0112) then transferred to a PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, 10600023) and probed with anti-HA-Peroxidase (Roche, 12013819001) (1:2000). MBD7-3xHA was detected by autoradiography using ECL2 Western Blotting Substrate (Pierce, 80196).

Western blot analysis of 9xMyc-LIL transgenic lines was performed using 0.3 g of 10-day-old seedlings. Tissue was mechanically disrupted and homogenized in cold IP buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% Glycerol, 0.1% NP40) with protease inhibitors. 9xMyc-LIL was immunoprecipitated using Dynabeads Protein G (Invitrogen, 10004D) incubated with monoclonal anti-Myc Tag antibody (Millipore, 05–724). The immunoprecipitate was resolved on a 10% TGX Mini-Protean Gel (Bio-Rad, 456–8035), transferred to a PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, 10600023) and probed with a monoclonal anti-Myc primary antibody (Millipore, 05–724) (1:4000) and a HRP-conjugated Goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (BioRad, 170–6516) (1:5000). 9xMyc-LIL was detected by autoradiography using ECL2 Western Blotting Substrate (Pierce, 80196).

Traditional bisulfite sequencing

Approximately 2 μg of genomic DNA, extracted using the CTAB method from 10-day-old seedlings, was bisulfite-treated using the MethylCode Bisulfite Conversion Kit (Invitrogen, MEV50). Amplification of specific genomic loci was performed using transgene-specific primers (Supplementary file 4; d35S2 tBS Forward and d35S2 tBS Reverse), KAPA HiFi HotStart Uracil+ ReadyMix PCR Kit (KAPA Biosystems, KK2801) and the following PCR conditions: 95°C for 5 min; 98°C for 30 s; 2 cycles of 98°C for 30 s, 66.5°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min; 2 cycles of 98°C for 30 s, 65.5°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min; 2 cycles of 98°C for 30 s, 64.5°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min; 2 cycles of 98°C for 30 s, 63.5°C for 1 min; 32 cycles of 98°C for 30 s, 62.5°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min; and 72°C for 15 min. PCR products were run on a 2% agarose gel and ~500 bp bands were purified using the QIAGEN Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, 28704). Purified PCR products were cloned into the pCRII-TOPO vector using the Invitrogen ZeroBlunt TOPO PCR cloning kit (Invitrogen, 450245). The resulting plasmids were transformed into One-Shot TOP10 Chemically Competent E. coli cells (Invitrogen, C404003). Sequencing was performed from bacterial glycerol stocks of 24 different colonies using the M13 Forward (−21) primer. A small number of clonal sequences as well as sequences with regions of potential non-conversion were removed from the analysis. Sequences were aligned to a reference using the CLC Main Workbench (www.clcbio.com) and visualized using cymate. The percent methylation (number of methylated cytosines divided by the total number of cytosines) was calculated for each cytosine. The average percent methylation was reported for specific ranges within the 35S sequence.

Small RNA library construction, sequencing, and bioinformatics analysis

Total RNA was size-fractionated by electrophoresis and RNAs 15 to 40 nt in length were purified and subjected to library construction. Small RNA libraries were prepared using the TruSeq Small RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, RS-200–0012) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and sequenced with Illumina's HiSeq2000 platform at the UCR Institute for Integrative Genome Biology (IIGB) genomic core facility. 3’ adapter sequences were trimmed from the raw reads using custom Perl scripts (Source code 1). Reads <18 nt after adapter trimming or corresponding to rRNA, tRNA, snRNAs and snoRNAs were discarded. The remaining reads were aligned to the TAIR10 Arabidopsis genome or the YJ/LUCH transgene sequence using bowtie allowing for perfect match only and multiple mapping (-v 0 –m 1000) or unique mapping (-v 0 –m 1).

MethylC-seq library construction and sequencing

MethylC-seq libraries corresponding to the ‘_r2, _r5, and_B’ series (Supplementary file 1E) were prepared as follows: Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, 69104). One microgram of genomic DNA was sonicated into fragments 150 to 300 bp in length using a Diagenode Bioruptor, followed by purification with the PureLink PCR Purification Kit (Invitrogen, K3100-01). DNA ends were repaired using the End-It DNA End-Repair Kit (Epicentre, ER0720), and the DNA fragments were purified using the Agencourt AMPure XP-PCR Purification system (Beckman Coulter, A63880). The purified DNAs were adenylated at the 3’ end using the polymerase activity of Klenow Fragment (3’→5’ exo-) (New England Biolabs, M0212), followed by purification using the Agencourt AMPure XP-PCR Purification system. The methylated adapters in the TruSeq DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, FC-121–2001) were ligated to the DNA fragments using T4 DNA Ligase (New England Biolabs, M0202). After purification using AMPure XP beads, less than 400 ng DNA was subjected to bisulfite conversion using the MethylCode Bisulfite Conversion Kit (Invitrogen, MECOV-50). PfuTurbo Cx Hotstart DNA polymerase (Agilent, 600414) and the following PCR conditions were used for amplification: 95°C for 2 min; 9 cycles of 98°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s and 72°C for 4 min; and 72°C for 10 min.

All the remaining MethylC-seq libraries (Supplementary file 1E) were prepared following a slightly modified protocol as detailed in Urich et al. (2015). Genomic DNA was extracted from 10-day-old seedlings using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, 69104). 2 μg of genomic DNA was sonicated into 200 bp fragments using a Covaris S2 Sonicator, followed by purification with Sera-Mag Magnetic SpeedBeads (ThermoScientific, 65152105050250). DNA ends were repaired using the End-It DNA End-Repair Kit (Epicentre, ER81050), and the DNA fragments were purified using Sera-Mag Magnetic SpeedBeads. The purified DNAs were adenylated at the 3’ end using the polymerase activity of Klenow Fragment (3’→5’ exo-) (New England Biolabs, M0212), followed by purification using Sera-Mag Magnetic SpeedBeads. The methylated adapters in the NEXTflex Bisulfite-Seq Barcodes Kit (BIOO Scientific, 511911) were ligated to the DNA fragments using T4 DNA Ligase (New England Biolabs, M0202). After purification using Sera-Mag Magnetic SpeedBeads, the DNA was subjected to bisulfite conversion using the MethylCode Bisulfite Conversion Kit (Invitrogen, MECOV-50). KAPA HiFi HotStart Uracil+ ReadyMix PCR Kit (KAPA Biosystems, KK2801) and the following PCR conditions were used for amplification: 95°C for 2 min; 98°C for 30 s; 4 cycles of 98°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s and 72°C for 4 min; and 72°C for 10 min. After purification using Sera-Mag Magnetic SpeedBeads, the libraries were pooled and then sequenced and processed by the Next Generation Sequencing Core at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

Illumina sequencing