Abstract

B lymphocyte differentiation is coordinated with the induction of high-level Ig secretion and expansion of the secretory pathway. Upon accumulation of unfolded proteins in the lumen of the ER, cells activate an intracellular signaling pathway termed the unfolded protein response (UPR). Two major proximal sensors of the UPR are inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), an ER transmembrane protein kinase/endoribonuclease, and ER-resident eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) kinase (PERK). To elucidate whether the UPR plays an important role in lymphopoiesis, we carried out reconstitution of recombinase-activating gene 2–deficient (rag2–/–) mice with hematopoietic cells defective in either IRE1α- or PERK-mediated signaling. IRE1α-deficient (ire1α–/–) HSCs can proliferate and give rise to pro–B cells that home to bone marrow. However, IRE1α, but not its catalytic activities, is required for Ig gene rearrangement and production of B cell receptors (BCRs). Analysis of rag2–/– mice transplanted with IRE1α trans-dominant-negative bone marrow cells demonstrated an additional requirement for IRE1α in B lymphopoiesis: both the IRE1α kinase and RNase catalytic activities are required to splice the mRNA encoding X-box–binding protein 1 (XBP1) for terminal differentiation of mature B cells into antibody-secreting plasma cells. Furthermore, UPR-mediated translational control through eIF2α phosphorylation is not required for B lymphocyte maturation and/or plasma cell differentiation. These results suggest specific requirements of the IRE1α-mediated UPR subpathway in the early and late stages of B lymphopoiesis.

Introduction

B cell development is a highly regulated process whereby functional peripheral subsets are produced from HSCs. B cells sequentially rearrange their Ig heavy chains at the pro–B cell stage, undergo clonal expansion at the pre–B cell stage, rearrange their light chains to yield newly formed surface Ig+ B cells, and finally differentiate into plasma cells, the terminal effector cells that secrete large amounts of Igs (1–3). Although the developmental stages of B cell differentiation are well defined by specific transcriptional activation and silencing of genes that influence cellular identity, the molecular mechanisms regulating B lymphopoiesis, including induction of genes encoding recombination factors for Ig gene rearrangement, activation of factors involved in receiving and transducing intracellular and extracellular signals, and the mechanism used by plasma cells to handle the vast increase in Ig secretion, are largely unknown.

The unfolded protein response (UPR) is an intracellular signal transduction pathway from the ER to the nucleus that senses a variety of ER stress conditions, such as expression of unfolded or misfolded proteins, elevated secretory protein synthesis, and/or perturbation in calcium homeostasis (4–7). Inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) is a type I ER transmembrane Ser/Thr protein kinase/endoribonuclease that serves as a proximal UPR transducer in all eukaryotes (8–10). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, under ER stress, Ire1p homodimerization and trans-autophosphorylation activate its RNase activity to initiate an unconventional splicing reaction on HAC1 mRNA, which subsequently encodes a potent transcription factor that upregulates most UPR target genes (11, 12). In mammalian cells, there are 2 homologues of ire1 gene, ire1α and ire1β (13, 14). Whereas ire1α is expressed in most cells and tissues, ire1β expression is primarily restricted to the intestinal epithelial cells. Upon accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER, activated IRE1 initiates unconventional splicing of the mRNA encoding the basic leucine zipper–containing (b-ZIP–containing) transcription factor X-box–binding protein 1 (XBP1) to remove a 26-nucleotide intron and generate a switch in the translational-reading frame (15–17). Spliced XBP1 mRNA encodes a potent transcriptional activator that induces expression of UPR target genes. In addition, the cytoplasmic domain of activated IRE1α can recruit the adaptor protein TNF receptor–associated factor 2 (TRAF2), leading to programmed cell death through JNK signaling (18).

In mammals, the UPR has 2 additional proximal sensors: the activating transcription factor ATF6 and ER-resident eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α kinase (PERK). ATF6 is a type II ER transmembrane protein that undergoes ER stress–induced proteolysis to liberate its cytosolic domain, a b-ZIP–containing transcription factor (19–21). It has been suggested that IRE1α and ATF6 function in the same pathway to regulate the production and splicing of XBP1 mRNA, ultimately amplifying the UPR (15, 22). Under conditions that activate IRE1 and ATF6, PERK is also activated to phosphorylate eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 on its α subunit (eIF2α), thereby attenuating general protein translation (23–25). Paradoxically, phosphorylated eIF2α selectively increases translation of ATF4 mRNA, which encodes an activating transcription factor that is required for transcriptional induction of one-third of the UPR genes (25, 26). Upon ER stress, 2 arms of the UPR, transcriptional induction mediated by IRE1 and ATF6 and translational regulation mediated by PERK, are complementary for maintaining ER homeostasis and ensuring cell survival (17).

Although it is known that the UPR is required for cells to survive conditions of stress that result in protein unfolding and/or misfolding in the ER, it is less clear whether these signaling pathways have additional physiological roles. Since all proteins are translocated into the ER lumen in an unfolded state and require chaperone-assisted protein folding, it is possible that increased secretory protein synthesis associated with cells differentiating to specialized types is also a stress that activates UPR signaling. The identification of XBP1 as the substrate for mammalian IRE1 was the first indication that UPR signaling might regulate B cell differentiation, since it has been demonstrated that XBP1 is required for plasma cell differentiation (27). While induction of Ig heavy chain and light chain gene rearrangement and the assembly and transport of IgMμ to B cell receptors (BCRs) occurred normally, plasma cells were markedly absent in the recombinase-activating gene 2–deficient (rag2–/–) mice reconstituted by XBP1-deficient stem cells (27). Recent studies demonstrated that synthesis of ER chaperone proteins and activated ATF6 protein was increased in B lymphocytes upon LPS or IL-4 stimulation (28–30). However, expression of spliced XBP1, a classic marker of the UPR, was detected only after the increased synthesis of Ig chains during plasma cell differentiation (29, 30). Spliced XBP1 protein can restore production of Igs in XBP1-deficient B cells and can enhance secretion of Igs in normal B cells; this suggests an essential role for XBP1 in production of high-level Igs (30).

These studies support the hypothesis that B cell differentiation into plasma cells utilizes the UPR to accommodate the vast increase in Ig production (2, 31, 32). However, to date there is no compelling evidence that UPR signaling from the ER is required. Studies reporting that XBP1 is required for plasma cell differentiation have also generated several important questions concerning the physiological roles of the UPR in lymphocyte development. First, as a proximal UPR transducer and the protein required for splicing of XBP1 mRNA, is IRE1α directly activated and required for B cell differentiation? Does IRE1α execute alternative functions in addition to splicing of the XBP1 mRNA? Second, is UPR signaling involved in the early stage of B cell lymphopoiesis? Third, is the other known UPR subpathway, PERK-mediated translational control through eIF2α, also required for B cell differentiation? To answer these questions, we carried out systematic studies on roles of IRE1α in lymphocyte development by using the RAG2 complementation system (33). Through reconstitution of RAG2-deficient mice with IRE1α-deficient fetal hematopoietic cells, we demonstrated that IRE1α is essential for early lymphopoiesis at the stage of pro–B cells. Through reconstitution of RAG2-deficient mice with bone marrow cells expressing trans-dominant-negative mutant IRE1α, we demonstrated that IRE1α is also required at a late stage in B cell lymphopoiesis in which IRE1α-mediated splicing of the XBP1 mRNA is essential for the terminal differentiation of B cells into plasma cells.

Results

IRE1α is required for liver growth and embryonic development.

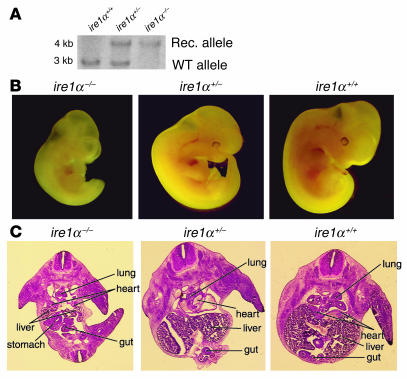

The murine ire1α gene in embryonic stem cells derived from the SVJ129 mouse was disrupted by deletion of exons 7–14 (22). Heterozygous stem cells containing the deleted ire1α allele were injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts to generate heterozygous IRE1α knockout (ire1α+/–) mice. While the ire1α+/– mice appeared normal, no homozygous ire1α–/– mice were obtained from extensive mating of heterozygous ire1α+/– mice. The ire1α+/– mice of the SVJ129/C57BL/6J–strain background were backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice and were then subjected to serial timed mating. Genotyping of embryos revealed that most homozygous ire1α–/– embryos died between 12.5 and 13 days of gestation (Table 1 and Figure 1A). By E13, the ire1α–/– embryos could be recognized by their small size, growth retardation, and pale coloration (Figure 1B). Histological inspection of ire1α–/– embryos identified that the fetal livers of the ire1α–/– mice were markedly reduced in size compared with the livers of WT littermates (Figure 1C). In addition, fetal liver cells in the ire1α–/– embryos at E12.5 were less densely packed (data not shown). We found that the fetal liver hypoplasia observed in the ire1α–/– mice was associated with defective expression of several acute-phase response genes that are required for liver development (K. Zhang and R.J. Kaufman, unpublished observations).

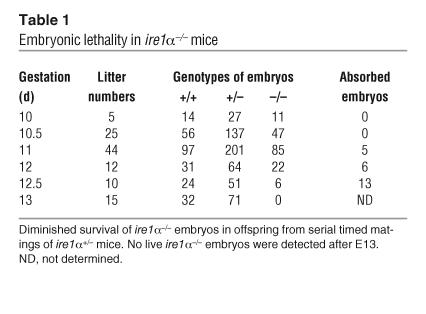

Table 1.

Embryonic lethality in ire1α–/– mice

Figure 1.

Phenotype of ire1α–/– embryos. (A) Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA from yolk sacs of ire1α+/+, ire1α+/–, and ire1α–/– embryos. The WT and knockout embryos have a 3-kb WT ire1α allele and a 4-kb recombinant allele, respectively. The heterozygous embryo has both the WT and the recombinant alleles. Rec. allele, ire1α recombinant allele; WT allele, WT ire1α allele. (B) Morphology of ire1α–/–, ire1α+/–, and ire1α+/+ embryos. The ire1α–/–, ire1α+/–, and ire1α+/+ embryos were from the same littermates at E12.5. Magnification, ×10. (C) Histological analysis of ire1α–/–, ire1α+/–, and ire1α+/+ embryos at E12.5. Paraffin-embedded sections (5 μM) of embryos were stained with H&E and visualized at magnification ×20.

IRE1α-deficient fetal liver and aorta-gonad-mesonephros cells can proliferate and colonize hematopoiesis.

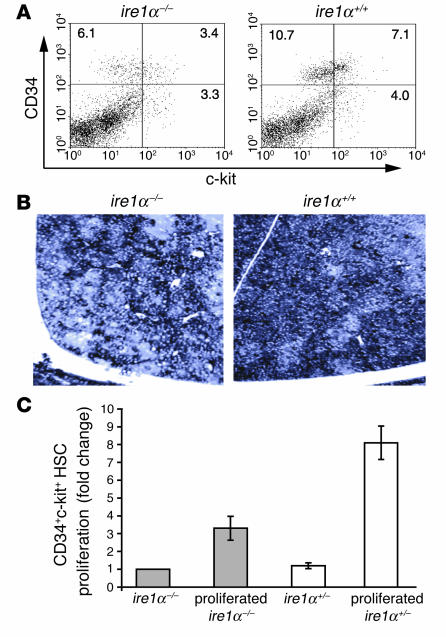

In mammals, definitive hematopoiesis starts in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) at E10.5 and thereafter shifts to the fetal liver before birth (34). Since ire1α–/– mice display liver hypoplasia and embryonic lethality between E12.5 and E13, in order to obtain sufficient cell mass, we studied the growth and differentiation of HSCs isolated from both AGM and fetal liver of E10.5–E12 embryos. CD34 and c-kit double-positive HSCs from AGM and/or fetal liver at E10.5–E12.5 can reconstitute the entire hematopoietic lineage in transplanted mice (35, 36). FACS analysis revealed that the ire1α–/– embryos have a significant CD34+ and/or c-kit+ hematopoietic cell population, suggesting that hematopoiesis could occur in ire1α–/– embryos (Figure 2A). However, the total number of CD34+c-kit+ HSCs in ire1α–/– embryos was approximately 2-fold lower than that in WT (ire1α+/+) embryos (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Characterization of ire1α–/– HSCs. (A) Phenotype of ire1α–/– HSCs from fetal liver and AGM. FACS analysis of CD34 and c-kit in cells from ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ fetal liver and AGM at E11. The ratio of the number of AGM cells to that of fetal liver cells used for FACS analysis was 2:1. Representative data from 1 of at least 3 separate experiments are shown. (B) BrdU labeling of ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ fetal livers at E11. The pregnant mouse was injected with 10 mg BrdU at 2 hours before isolation of embryos. Paraffin-embedded sections (5 μM) were stained with anti-BrdU antibody and visualized at ×100 magnification. The proliferating cells in the fetal livers that incorporated BrdU can be identified by dark staining. (C) Proliferation rates of ire1α–/– and ire1α+/– HSCs. Fetal liver cells from WT embryos at E14.5 were first cultured for 2 days to create a hepatic stromal layer. Similar amounts of ire1α–/– and ire1α+/– CD34 and c-kit double-positive HSCs from embryos at E11 were overlaid on the hepatic stromal layer and were cultured for 10 days. The proliferation rates of ire1α–/– and ire1α+/– HSCs were determined by quantification of neomycin gene copies in the genomic DNA isolated from the proliferated ire1α–/– and ire1α+/– cells. The proliferation rate of the ire1α–/– cells was defined as 1. The proliferation rates of other cells were compared with that of the ire1α–/– cells. Experiments were performed at least 3 times, and the SD is indicated.

The proliferative capacity of hematopoietic cells derived from ire1α–/– AGM and fetal livers was studied. BrdU labeling indicated a significant, although smaller, population of dividing cells in the ire1α–/– fetal livers at E11 compared with that in WT, suggesting that the ire1α–/– hematopoietic cells can migrate to the fetal liver and proliferate (Figure 2B). In order to quantitate the proliferation rates of ire1α–/–, ire1α+/–, and ire1α+/+ HSCs in vitro, fetal liver cells from WT embryos at E14.5 were first cultured for 2 days to create a hematopoietic microenvironment (37). Subsequently, equivalent numbers of CD34+c-kit+ cells sorted by flow cytometry from the AGM and fetal livers of the ire1α–/– or ire1α+/– embryos at E11 were overlaid. After 10 days of culture, round floating cells above the hepatic stromal layer were observed in plates overlaid with either ire1α–/– or ire1α+/– HSCs. Microscopic observation and FACS analysis of the hematopoietic cell surface markers CD34 and c-kit confirmed that these floating cells were hematopoietic cells. These floating hematopoietic cells were then collected for DNA extraction. Since both the ire1α–/– and the ire1α+/– cells carry the neomycin (Neo) resistance gene derived from the IRE1α targeting vector, a real-time PCR was designed to quantitate copies of the neo gene in the harvested genomic DNA (Figure 2C). The gene copy number reflects the proliferation rate of ire1α+/– or ire1α–/– hematopoietic cells. Ire1α+/– hematopoietic cells show no difference in proliferation rate compared with ire1α+/+ cells (data not shown). Therefore, subsequent studies used the proliferation rate of ire1α+/– hematopoietic cells in place of that of ire1α+/+ cells. After in vitro culture for 10 days, the proliferation rate of ire1α–/– HSCs was approximately 2.5 times lower than that of ire1α+/– HSCs (Figure 2C). However, the number of ire1α–/– HSCs did increase approximately 3-fold (Figure 2C).

IRE1α regulates Ig gene rearrangement and is thus required for production of BCRs.

To further investigate the role of IRE1α in B cell differentiation, AGM and fetal liver hematopoietic cells isolated from ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ embryos at E10.5–E12 were transplanted into lethally irradiated rag2–/– mice to reconstitute lymphocyte lineages. The lethally irradiated rag2–/– mice without transplantation or transplanted with media died within a few days after irradiation. In contrast, the lethally irradiated rag2–/– mice reconstituted with ire1α–/– or ire1α+/+ fetal hematopoietic cells survived as long as 4 weeks or even longer. Four weeks after transplantation, bone marrow cells were harvested from the reconstituted rag2–/– mice and subjected to FACS analysis of cell surface markers CD43, B220, heat-stable antigen (HSA), BP-1, IgM, TER119, and Mac-1. Whereas B220 is a general marker for B cells from the very early stage to the late stage, CD43 is expressed in HSCs, lymphoid progenitors, and early-stage B cells in the bone marrow but is not expressed in late-stage B cells (1, 38, 39). In the bone marrow of ire1α–/–rag2–/– chimeric mice, there was a comparable number of CD43+B220+ B lymphocyte precursor cells (approximately 7.1%) (Figure 3A), which suggests that ire1α–/– HSCs have no defect in commitment of lymphoid precursors. However, the percentage of the CD43–B220+ B cells was significantly decreased in the ire1α–/– reconstituted bone marrow, while CD43–B220+ B cells were a dominant B cell population in ire1α+/+ reconstituted bone marrow (Figure 3A).

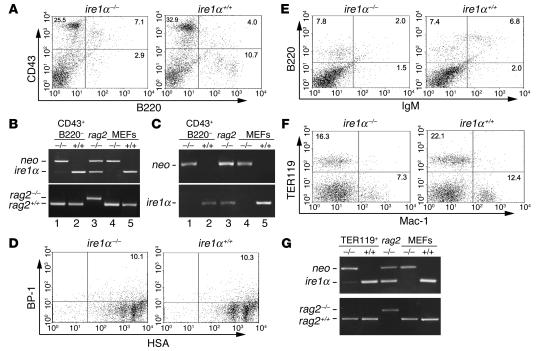

Figure 3.

Development of B cells is blocked at the early stage in the absence of IRE1α. (A) FACS analysis of cell surface markers CD43 and B220 in bone marrow cells from rag2–/– mice after 4 weeks of reconstitution with ire1α–/– or ire1α+/+ fetal liver and AGM cells. (B) Genotypes of the CD43+B220– cells sorted from the reconstituted bone marrow. The upper panel shows amplification of segments from the neo gene and the murine ire1α gene. The first 2 lanes show CD43+B220– cells sorted from the ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ reconstituted bone marrow. The third lane shows CD43+B220– cells sorted from nonirradiated rag2–/– mice. The fourth and fifth lanes show ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ MEFs, which served as controls for the genotype of ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ cells, respectively. The lower panel shows amplification of the rag2 gene WT (rag2+/+) and knockout (rag2–/–) alleles. Through calibration of the amplified gene alleles, the ratios of donor cells to recipient cells in both ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ reconstituted CD43+B220– populations were found to be more than 10:1. (C) RT-PCR analysis of expression of ire1α and neo genes in the CD43+B220– cells sorted from the reconstituted bone marrow. The samples are the same as described in B. (D–F) FACS analysis of cell surface markers BP-1 and HSA (D), B220 and IgM (E), and TER119 and Mac-1 (F) in ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ reconstituted bone marrow cells. (G) Genotypes of TER119+ cells sorted from the reconstituted bone marrow. The first 2 lanes show TER119+ cells sorted from the ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ reconstituted bone marrow. The third lane shows TER119+ cells from nonirradiated rag2–/– mice. The fourth and fifth lanes show ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ MEFs. Through calibration of the amplified gene alleles, the ratios of donor cells to recipient cells in both ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ reconstituted TER119+ populations were found to be more than 8:1. For A–G, experiments were performed at least 3 times and representative data are shown.

To exclude the possibility that the reconstituted pro–B cells were derived from the rag2–/– host bone marrow, we genotyped the CD43+B220– precursor cells sorted by flow cytometry. Multiplex PCR was used to amplify a 500-bp neo gene fragment from the targeting vector and a 200-bp fragment from exon 7 of the murine ire1α gene (Figure 3B). In the CD43+B220– cells from the ire1α–/– reconstituted bone marrow, the neo gene was readily amplified by the multiplex PCR, while the ire1α exon 7 fragment could only be detected in a very minor amount (Figure 3B, lane 1). In contrast, only the ire1α exon 7 fragment was amplified in the CD43+B220– cells from the ire1α+/+ reconstituted bone marrow (Figure 3B, lane 2). As a control, both the neo gene and the ire1α exon 7 fragments could be amplified in the nonirradiated rag2–/– bone marrow cells (Figure 3B, lane 3). These data suggested that the majority of the ire1α–/– reconstituted CD43+B220– precursor cells came from the ire1α–/– donor population. Furthermore, we amplified the WT and knockout alleles of the rag2 gene from the same DNA templates using a multiplex PCR as previously described (40). In agreement with the genotyping result for ire1α and neo genes, the ire1α–/– reconstituted CD43+B220– cells carried the WT allele and very few, if any, knockout alleles of the rag2 gene (Figure 3B, lower panel, lane 1). This result further confirmed that the majority of the CD43+B220– lymphocyte precursor cells detected in the ire1α–/–rag2–/– chimeric mice were derived from the ire1α–/– donor, not from the rag2–/– host. To demonstrate that the ire1α–/– cells successfully engrafted and survived well in the bone marrow, we isolated RNA from the same CD43+B220– precursor cells and examined expression of the neo and ire1α genes by RT-PCR (Figure 3C). Although the IRE1α transcript was not detected, the ire1α–/– reconstituted CD43+B220– cells expressed abundant Neo transcript (Figure 3C, lane 1), suggesting the notion that the ire1α–/– fetal hematopoietic cells survived well and were able to give rise to lymphoid precursors.

FACS analysis of cell surface markers HSA and BP-1 revealed a normal HSA+BP-1+ early B cell population present in ire1α–/– reconstituted bone marrow (Figure 3D). We then further investigated the presence of BCRs in the reconstituted bone marrow by assessing B220 and IgM cell surface markers. There was a distinct defect in the B220+IgM+ cell population in the ire1α–/– reconstituted bone marrow (Figure 3E), suggesting a requirement of IRE1α in BCR formation. Furthermore, we checked erythropoiesis, myelopoiesis, and thrombopoiesis in the reconstituted animals. The erythroid and myeloid lineages in the reconstituted bone marrow were examined by analysis of the cell surface markers TER119, for erythroid lineage, and Mac-1, for myeloid lineage (Figure 3F). The ire1α–/– reconstituted animals produced comparable erythroid and myeloid lineages in the bone marrow, although the percentages were relatively low compared with those in the ire1α+/+ reconstituted mice. Genotype analysis of the sorted TER119+ cells confirmed that the majority of erythrocytes from the ire1α–/–rag2–/– chimeric mice were derived from the ire1α–/– donor (Figure 3G). In addition, blood lineage counts were performed for the reconstituted mice (Supplemental Table 1; supplemental material available online with this article; doi:10.1172/JCI200521848DS1). The ire1α–/– reconstituted mice had comparable numbers of platelets in the blood, indicating that thrombocyte lineages could be reconstituted in the absence of IRE1α. All these results suggested that the ire1α–/– hematopoietic cells could give rise to pro–B cells as well as erythroid, myeloid, and thrombocyte lineages but had a distinct defect in BCR formation. Consistent with the defect in BCRs, no serum IgM or IgG1 was produced in the ire1α–/–rag2–/– chimeric mice after a long-term reconstitution (Supplemental Figure 1A). Interestingly, although the ire1α–/– cells could successfully home in the bone marrow, they failed to engraft in the peripheral lymphoid organs, including spleen and thymus (Supplemental Figure 1, B and C).

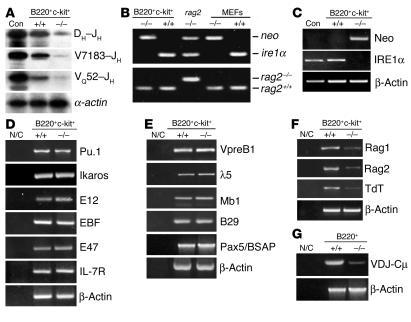

A critical step in the differentiation of pro–B cells is rearrangements of Ig genes (41, 42). The absence of CD43–B220+ and B220+IgM+ stages of B cells in the ire1α–/–rag2–/– mice implied a possible defect in Ig gene rearrangements in ire1α–/– pro–B cells. To investigate VDJ rearrangements in ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ reconstituted bone marrow, we sorted B220+c-kit+ cells, including pro–B cells and a small portion of early pre–B cells, from the reconstituted bone marrow cells by flow cytometry sorting (1). DNA and total RNA were extracted from the sorted cells for analysis of Ig gene rearrangements and induction of various genes, respectively. We first used primers to amplify a DNA ladder of rearranged D segments to assess DH–JH rearrangement as previously described (43–45). In the ire1α–/– reconstituted B220+c-kit+ cells, the level of DH–JH rearrangement was significantly decreased compared with that in the ire1α+/+ reconstituted B220+c-kit+ cells (Figure 4A). VH–DJH rearrangement was also assessed by amplification of J-proximal members of the 7183 and Q52 V gene families. While ire1α+/+ reconstituted B220+c-kit+ cells possessed significant V7183–JH and VQ52–JH rearrangements, very little V7183–JH or VQ52–JH rearrangement could be detected in the ire1α–/– reconstituted pro–B and early pre–B cells (Figure 4A). To confirm that these reconstituted B220+c-kit+ cells came from the donor populations, the sorted B220+c-kit+ cells were genotyped for the neo, ire1α, and rag2 genes. The neo gene fragment and the rag2 gene WT allele were detected in the ire1α–/– reconstituted B220+c-kit+ cells, while exon 7 of the ire1α gene and the rag2 gene knockout allele could barely be detected in these cells; this suggests that the ire1α–/– reconstituted B220+c-kit+ cells were derived from the ire1α–/– donor, not from the rag2–/– host (Figure 4B). In addition, expression of the ire1α and neo genes in the reconstituted B220+c-kit+ cells was examined by RT-PCR (Figure 4C). The ire1α–/– reconstituted cells expressed Neo but not IRE1α transcripts, suggesting that the ire1α–/– reconstituted B220+c-kit+ cells survived well. All these results reveal a severe impairment of VDJ recombination of Ig genes in the ire1α–/– reconstituted bone marrow cells.

Figure 4.

Impaired VDJ rearrangements in B lymphocytes in the absence of IRE1α. (A) Analysis of Ig gene rearrangement in reconstituted B220+c-kit+ cells. DNA was isolated from B220+c-kit+ cells sorted from ire1α+/+ and ire1α–/– reconstituted bone marrow. B220+ bone marrow cells sorted from a 4-week-old WT mouse served as a positive control (Con). To control variation in input DNA or amplification efficiency, a fragment from the α-actin gene was amplified. (B) Genotypes of the B220+c-kit+ cells sorted from the reconstituted bone marrow. The B220+c-kit+ cells were the same as in A. Through calibration of the amplified gene alleles, the ratios of donor cells to recipient cells in both ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ reconstituted B220+c-kit+ populations were found to be more than 15:1. (C) RT-PCR analysis of expression of ire1α and neo genes in the same B220+c-kit+ cells as in A. A fragment from β-actin transcript was amplified to control variation in input RNA and amplification efficiency. (D–F) Induction profiles of genes encoding factors required for very early stage B lymphopoiesis (D), genes encoding accessory proteins required for IgM complex (E), and genes encoding factors required for initiation of VDJ rearrangements (F). Total RNA was extracted from B220+ cells sorted from the ire1α+/+ and ire1α–/– reconstituted bone marrow. (G) Expression of VDJ-Cμ transcripts in ire1α+/+ and ire1α–/– reconstituted B220+ bone marrow cells. Total RNA was extracted from B220+ cells sorted from the ire1α+/+ and ire1α–/– reconstituted bone marrow. For A–G, experiments were performed at least 3 times and representative data are shown.

To explore the specific factors involved in the defect of VDJ recombination in the ire1α–/– B cells, the transcriptional induction of factors regulating early B lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation, including PU.1, Ikaros, E12, E47, EBF, and IL-7 receptor (46, 47), was investigated by semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis. The genes encoding PU.1, Ikaros, E12, E47, EBF, and IL-7 receptor were induced normally in ire1α–/– reconstituted B220+c-kit+ cells (Figure 4D). The genes encoding accessory proteins for the IgM molecular complex, including B29, Mb1, λ5, VpreB1, and the gene encoding the B cell–specific activator protein Pax5/BSAP, play critical roles in regulating VDJ recombination and pre-BCR formation (1, 3). These genes were also similarly induced in ire1α–/– and ire1α+/+ reconstituted B220+c-kit+ cells (Figure 4E). The VDJ recombination–activating genes rag1 and rag2 and the gene encoding the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) are highly induced in the pro–B and early pre–B cells and are essential for successful VDJ rearrangements, generating antibody diversity and formation of pre-BCRs (48, 49). Further inspection revealed a significantly lower expression of RAG1, RAG2, and TdT transcripts in the ire1α–/– reconstituted B220+c-kit+ cells (Figure 4F). The defect in expression of RAG1, RAG2, and TdT transcripts could account, at least partially, for the defective rearrangements of Ig genes in the ire1α–/– reconstituted lymphocytes. Note that expression of RAG1, RAG2, and TdT transcripts was not completely abolished in the ire1α–/– reconstituted cells, although expression of each was very low. The expression profiles for RAG1, RAG2, and TdT transcripts observed in the ire1α–/– reconstituted cells were different from those in the rag2–/– B cells (50), which provides further evidence that the reconstituted cells we investigated were not from the rag2–/– host population. In addition, we examined production of VDJ-Cμ transcript in the reconstituted B220+ bone marrow cells by RT-PCR amplification of a fragment spanning rearranged Ig heavy chain V region and exon 1 of IgM constant region (Cμ1) (51, 52). Consistent with the impaired VDJ rearrangements, the level of VDJ-Cμ transcripts in ire1α–/– reconstituted B220+ bone marrow cells was significantly lower than that in ire1α+/+ reconstituted B cells (Figure 4G).

The IRE1α cytoplasmic domain is required for BCR formation and plasma cell differentiation.

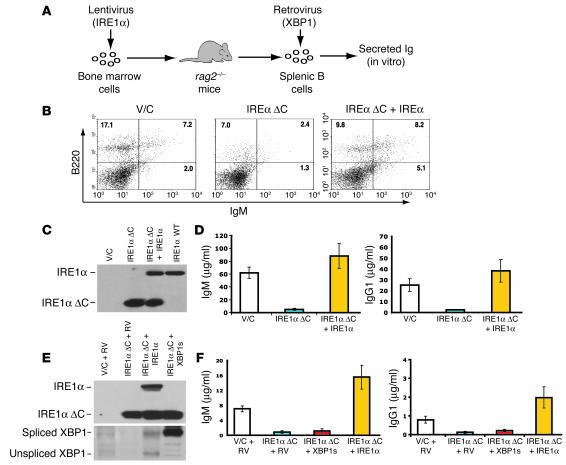

Since IRE1α is required in the early stage of B lymphopoiesis, we could not investigate possible roles of IRE1α in terminal B cell differentiation by the reconstitution of ire1α–/– fetal hematopoietic cells in rag2–/– mice. To test whether IRE1α plays a role in the terminal differentiation of B lymphocytes to plasma cells, we expressed a trans-dominant-negative mutant IRE1α protein (IRE1α °C) that lacks the cytoplasmic domain required for signaling in WT bone marrow cells. The overexpressed mutant IRE1α can dimerize with the WT endogenous IRE1α, thus functionally preventing IRE1α cytoplasmic domain signaling (53). For this approach, we generated bicistronic lentiviral vectors that express WT or mutant forms of IRE1α and GFP. The lentivirus-transduced bone marrow cells were sorted for GFP expression to generate populations stably expressing control vector, mutant IRE1α (IRE1α °C), and/or WT IRE1α protein. Bone marrow cells expressing dominant-negative IRE1α °C or expressing both WT and IRE1α °C proteins were transferred into lethally irradiated rag2–/– mice (Figure 5A). After 4 weeks of reconstitution, the reconstituted B cell population in the spleen was assessed by FACS analysis of cell surface markers B220 and IgM. FACS analysis revealed very few B220hi and/or IgM-positive B cells, and a defective BCR population (B220+IgM+), in the spleens of rag2–/– mice reconstituted with IRE1α °C bone marrow cells (Figure 5B). Importantly, coexpression of WT IRE1α in IRE1α °C bone marrow cells could rescue the defect of BCRs in the mice reconstituted with the IRE1α °C bone marrow cells (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

The IRE1α cytoplasmic domain is required for BCR formation and plasma cell differentiation. (A) Depiction of viral transduction and bone marrow cell transplantation. Lentivirus (IRE1α), lentivirus expressing IRE1α protein variants; Retrovirus (XBP1), retrovirus expressing spliced XBP1 protein. (B) FACS analysis of B220 and IgM in splenocytes from the reconstituted rag2–/– mice. (C) Western blot analysis of expression of the IRE1α transgenes in B220+ splenic B cells sorted from the reconstituted rag–/– mice as described in B. (D) Levels of serum IgM and IgG1 in the reconstituted rag2–/– mice. Blood samples were collected from the reconstituted rag2–/– mice at 1 month after transplantation. Levels of serum IgM and IgG1 were determined by ELISA and normalized to the number of GFP-positive B cells. (E) Western blot analysis of expression of IRE1α and XBP1 protein variants in primary splenic B cells after secondary viral transduction. (F) Levels of secreted IgM and IgG1 in LPS-stimulated B cells. The samples are labeled the same as described in E. Primary B cells after secondary viral transduction were treated with LPS (20 μg/ml) for 48 hours. Levels of secreted IgM and IgG1 in cultured medium were determined by ELISA. V/C, control virus–transduced; IRE1α °C, IRE1α cytoplasmic domain deletion; IRE1α °C + IRE1α, IRE1α °C plus WT IRE1α protein, RV, control retrovirus; XPB1s, retrovirus expressing spliced XBP1 protein. For B–F, experiments were performed at least 3 times and representative data and SD are shown.

To verify expression of IRE1α transgenes in the reconstituted splenic B cells, B220+ cells sorted from the reconstituted splenocytes were subjected to Western blot analysis using an antibody against the lumenal domain of IRE1α.Whereas the endogenous IRE1α protein in the reconstituted B cells was not detectable, the IRE1α °C protein was expressed in a large amount in the B cells reconstituted by the IRE1α °C bone marrow (Figure 5C). Moreover, significant amounts of IRE1α WT and °C proteins were detected in the B cells reconstituted by the bone marrow cells expressing both IRE1α °C and WT IRE1α (Figure 5C), thus confirming the validity of this dominant-negative reconstitution experimental system. These data suggest that IRE1α signaling through its cytoplasmic domain is required for BCR formation, consistent with the requirement of IRE1α in Ig gene rearrangements and BCR formation that was identified by the reconstitution with ire1α–/– fetal hematopoietic cells (Figures 3 and 4). Furthermore, levels of serum IgM and IgG1 in the reconstituted rag2–/– mice were determined and normalized to the quantity of GFP-positive B cells. Production of serum IgM and IgG1 in the rag2–/– mice reconstituted with IRE1α °C bone marrow cells was significantly decreased compared with production of serum IgM and IgG1 in control mice (Figure 5D). Coexpression of WT IRE1α in IRE1α °C bone marrow cells not only rescued the defect of BCRs (Figure 5B) but also restored and even increased production of secreted Igs in the reconstituted rag2–/– mice (Figure 5D). These results support the roles of the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain in B cell maturation and plasma cell differentiation.

Since XBP1 mRNA is the only known substrate of the IRE1α RNase in mammalian cells, we tested whether the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain functions in B cell development through splicing of the XBP1 mRNA. GFP-positive primary B cells were sorted from the spleens of rag2–/– mice reconstituted with control bone marrow cells, IRE1α °C bone marrow cells, or bone marrow cells expressing both IRE1α °C and WT IRE1α protein. These cells were then transduced with a GFP-expressing control retrovirus or with a retrovirus expressing both GFP and the spliced form of XBP1, as previously described (30) (Figure 5A). After secondary viral transduction, expression of IRE1α and XBP1 proteins in the transduced primary B cells was assessed by Western blot analysis. The splenic B cells after the secondary viral transduction expressed the IRE1α and XBP1 protein variants as expected (Figure 5E). The primary B cells after secondary viral transduction were stimulated with LPS and assayed for Ig production in vitro. After 48 hours of LPS treatment, levels of secreted IgM and IgG1 in the cultured medium were determined. Compared with the control cells infected with empty virus, IRE1α °C B cells were defective in production of secreted IgM and IgG1 in response to LPS (Figure 5F). Expression of spliced XBP1 only marginally restored production of the secreted Igs in IRE1α °C B cells. In contrast, levels of secreted IgM and IgG1 in the splenic B cells expressing both IRE1α °C and WT IRE1α were restored and were even increased upon LPS stimulation compared with those in the control (Figure 5F). Apparently, the differences in production of secreted IgM and IgG1 expression were not due to differences in transduction efficiency and/or XBP1 transgene expression, as shown by immunoblot analysis (Figure 5E). These results suggest that the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain provides an additional function different from XBP1 mRNA splicing in regulating B cell development.

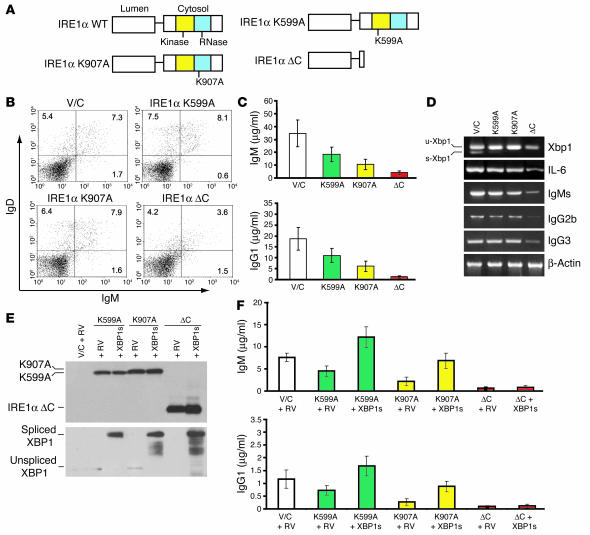

IRE1α kinase and RNase catalytic activities regulate Ig secretion through spliced XBP1.

The IRE1α cytoplasmic domain contains functional protein kinase and RNase domains that are structurally and functionally linked (11, 54). We therefore asked whether the IRE1α kinase and/or RNase catalytic activities are required for B lymphocyte differentiation. To answer this question, we reconstituted rag2–/– mice with bone marrow cells expressing single missense trans-dominant-negative mutants that are defective in IRE1α kinase or RNase catalytic activities (Figure 6A). The IRE1α kinase dominant-negative mutant (IRE1α K599A) and the RNase dominant-negative mutant (IRE1α K907A) were made by substitution of Ala for Lys599 or Lys907, respectively, in IRE1α (13, 53). Through lentiviral transduction, bone marrow cells expressing the IRE1α kinase mutant or RNase mutant were obtained and were subsequently transplanted into lethally irradiated rag2–/– mice. Surprisingly, in contrast to the rag2–/– mice reconstituted with bone marrow cells expressing the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain deletion (IRE1α °C), a normal IgM+IgD+ mature B cell population was detected in the spleens of rag2–/– mice reconstituted with bone marrow cells expressing either the IRE1α kinase mutant (K599A) or the IRE1α RNase mutant (K907A) (Figure 6B). These results indicate that VDJ recombination and class-switch recombination can occur normally in the IRE1α kinase or RNase mutant B cells, but not in the B cells that lack the whole IRE1α cytoplasmic domain. However, inspection of serum Igs revealed that levels of secreted IgM and IgG1 in IRE1α kinase or RNase mutant mice were approximately 2–3 times lower than those in controls (Figure 6C). Therefore, the defects in serum Igs in IRE1α kinase or RNase mutant mice are apparently not due to a decrease in the numbers of BCRs and/or mature B cells (Figure 6B); this suggests a specific requirement for the IRE1α kinase and RNase activities in the production of secreted Igs.

Figure 6.

IRE1α kinase and RNase activities regulate the production of Ig through spliced XBP1. (A) Depiction of IRE1α trans-dominant-negative vectors. IRE1α K599A, IRE1α kinase mutant; IRE1α K907A, IRE1α RNase mutant. (B) FACS analysis of IgD and IgM in splenocytes from reconstituted rag2–/– mice. (C) Levels of serum IgM and IgG1 in the reconstituted rag2–/– mice. Blood samples were collected from the reconstituted rag2–/– mice at 1 month after transplantation. Levels of serum IgM and IgG1 were determined by ELISA and normalized to the number of GFP-positive B cells. (D) XBP1 splicing and induction of IL-6, secretory IgM, IgG2b, and IgG3 transcripts during plasma cell differentiation in the absence of the IRE1α kinase, RNase, or cytoplasmic domain. GFP and B220 double-positive splenic B cells were sorted from the reconstituted rag2–/– mice and subsequently stimulated with LPS (20 μg/ml) for 48 hours in vitro. Total RNA was isolated from the LPS-treated B cells and subjected to semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis. IgMs, secretory IgM transcript; u-Xbp1, unspliced xbp1 transcript; s-Xbp1, spliced xbp1 transcript. (E) Western blot analysis of expression of IRE1α and XBP1 protein variants in primary B cells after secondary viral transduction. (F) Spliced XBP1 restores Ig production in the IRE1α kinase or RNase mutant B cells, but not in the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain–deleted B cells. Primary B cells after secondary viral transduction were treated with LPS (20 μg/ml) for 48 hours. Levels of secreted IgM and IgG1 in cultured supernatants of the indicated stimulated B cells were determined by ELISA. For B–F, experiments were performed at least 3 times and representative data and SD are shown.

Induction of XBP1, IL-6, IgG2b, IgG3, and secretory IgM transcripts is critical for terminal differentiation of B cells. Therefore, we investigated induction of these genes in LPS-stimulated B cells that express the IRE1α dominant-negative mutants. GFP-positive primary B cells sorted from the reconstituted spleen were treated with LPS in vitro for 48 hours. Induction of XBP1, IL-6, IgG2b, IgG3, and secretory IgM transcripts was analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Compared with cells infected with control virus, the spliced form of XBP1 mRNA was significantly reduced in both IRE1α kinase and RNase mutant, as well as IRE1α °C B cells (Figure 6D). This demonstrates that the dominant-negative forms of IRE1α did effectively inhibit XBP1 mRNA splicing. Class-switch recombination, which was judged by induction of germ-line IgG2b and IgG3 transcripts, occurred to a similar degree in IRE1α kinase mutant, RNase mutant, and control B cells under LPS treatment (Figure 6D). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in induction of IL-6 and production of secretory IgM transcripts in the kinase or RNase mutant B cells. These results indicated that IRE1α catalytic activities are not likely to regulate the Ig production at the transcriptional level (Figure 6D). Interestingly, induction of IL-6, germline IgG2b and IgG3, and secretory IgM transcripts was significantly lower in B cells that lacked the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain than in B cells defective in IRE1α kinase or RNase (Figure 6D). These results support the notion that the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain may have an additional function(s) other than its kinase or RNase activity in regulating B cell differentiation.

To determine whether spliced XBP1 serves as the substrate of IRE1α in plasma cell differentiation, GFP-positive splenic B cells were sorted from the mice reconstituted with the IRE1α dominant-negative mutant bone marrow cells, and then transduced by control retrovirus or retrovirus overexpressing the spliced XBP1 protein. Expression of IRE1α and XBP1 protein variants in the B cells after secondary viral transduction was assessed by Western blot analysis (Figure 6E). Due to a defect in IRE1α autophosphorylation, the IRE1α K599A kinase mutant protein migrated slightly faster than the IRE1α K907A RNase mutant protein (Figure 6E). In the cells infected by retrovirus expressing spliced XBP1 protein, both the IRE1α variants and the spliced XBP1 proteins were successfully expressed, confirming validity of this experimental system. The primary B cells after secondary viral transduction were stimulated with LPS, and levels of secreted IgM and IgG1 in the cultured medium were determined after 48 hours of treatment. Under LPS treatment, expression of spliced XBP1 mRNA restored, and even increased, the levels of secreted IgM and IgG1 in IRE1α kinase and RNase mutant B cells in vitro, suggesting that IRE1α kinase and RNase activities regulate the production of Igs through spliced XBP1 (Figure 6F). In contrast, expression of spliced XBP1 failed to restore serum IgM or IgG1 in B cells that lacked the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain (Figure 6F), further confirming that the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain functions in B cell development through an additional mechanism(s) different from splicing of XBP1 mRNA.

IRE1α-mediated, not PERK-eIF2α–mediated, UPR signaling is required for B cell differentiation.

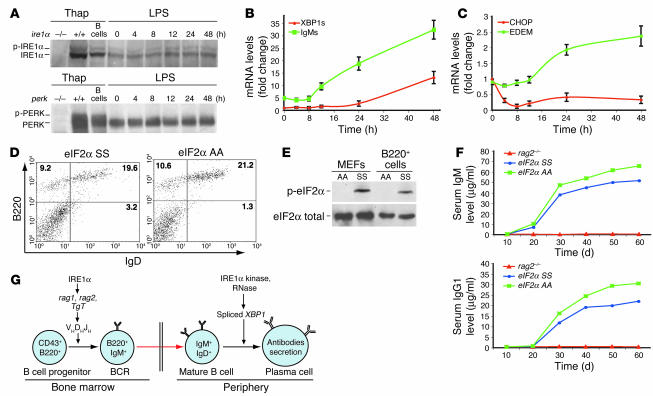

In addition to the UPR-activated IRE1α- and ATF6-mediated transcriptional induction, the ER-resident kinase PERK phosphorylates eIF2α to attenuate mRNA translation for maintaining ER homeostasis in response to stress (24). A recent study showed activation of ATF6 during plasma cell differentiation (28). Whether PERK-eIF2α UPR signaling is required for B cell differentiation is an important question for understanding of the physiological role of the UPR in B lymphopoiesis. To answer this question, B220+ primary B cells were treated with LPS for various time periods. Expression and activation of IRE1α and PERK proteins in LPS-treated B cells were analyzed by IP–Western blot analysis using an anti-IRE1α antibody and an anti-PERK antibody (Figure 7A). As controls for IRE1α and PERK IP–Western blot analysis, we included cell lysates from WT, ire1α–/–, and perk–/– murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), and primary B cells that were treated with thapsigargin, a reagent known to activate UPR transducers (7). Phosphorylated IRE1α was observed from the early stage and slightly increased over 12 hours of LPS treatment during antigen-stimulated plasma cell differentiation (Figure 7A). However, no significant difference in PERK activation was detected in primary B cells after 4–48 hours of LPS treatment (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

PERK-eIF2α UPR signaling is not required for plasma cell differentiation. (A) IP–Western blot analysis of expression and activation of IRE1α and PERK in primary B cells upon LPS stimulation. B220+ primary B cells from the spleens of 2-month-old WT mice were cultured in vitro in the presence of LPS (20 μg/ml) for the indicated time intervals. To generate controls for IRE1α and PERK proteins, WT, ire1α–/–, and perk–/– MEFs and primary B cells were treated with thapsigargin (Thap; 0.2 μM) for 3 hours. Equivalent amounts of cellular lysates were applied for each sample. p-, phosphorylated. (B–C) Kinetics of induction of spliced XBP1 and secreted IgM transcripts (B) and EDEM and CHOP transcripts (C) in primary B cells upon LPS treatment. Primary B cells were isolated from spleens of WT adult mice and were then stimulated with LPS (20 μg/ml) in vitro for the indicated time intervals. Levels of transcripts were determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. (D) FACS analysis of B220 and IgD in splenocytes from rag2–/– mice reconstituted with WT (eIF2α SS) or eIF2α phosphorylation–defective (eIF2α AA) fetal liver cells. Fetal hematopoietic liver cells (4 × 106) from E13.5 embryos were used for transplantion. (E) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated and total eIF2α proteins in the reconstituted B cells. B220+ cells were sorted from the spleens of rag2–/– mice reconstituted with eIF2α AA or SS fetal liver and then treated with 0.2 μM thapsigargin for 3 hours. Thapsigargin-treated eIF2α AA and SS MEFs were used as controls. (F) Levels of serum IgM and IgG1 in the rag2–/– mice reconstituted with eIF2α SS or eIF2α AA fetal liver cells. Blood samples were collected from the reconstituted rag2–/– mice at 1 month after transplantation. Levels of serum IgM and IgG1 were determined by ELISA. (G) The proposed model depicts that IRE1α is required for both the early and the late stages of B lymphocyte development. At the very early stage, IRE1α plays a role in the induction of the rag1, rag2, and TdT genes; thus IRE1α is required for VDJ recombination and BCR formation. At the late stage, IRE1α kinase and RNase activities regulate the terminal differentiation of B cells to plasma cells through splicing of XBP1 mRNA.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis showed that secretory IgM transcripts and subsequently spliced XBP1 mRNA were increased from 8 hours of LPS treatment and reached the highest level after 48 hours of treatment (Figure 7B). These results suggest that IRE1α is activated prior to the increase in secretory IgM transcripts and XBP1 mRNA splicing upon LPS stimulation (Figure 7, A and B). Induction of 2 UPR target genes, which encode ER-associated degradation–enhancing mannosidase-like protein (EDEM) and the proapoptotic transcription factor CHOP (also known as GADD153), respectively, was also investigated (Figure 7C). While induction of the chop gene did not change or perhaps slightly decreased with LPS treatment, induction of EDEM, which depends on the IRE1α-XBP1 UPR pathway and contributes to quality control of production of glycoproteins (55–57), was increased after 12 hours of LPS treatment (Figure 7C). The induction patterns of EDEM and secretory IgM transcripts in LPS-treated B cells indicate that EDEM was induced after increased synthesis of Ig heavy chain; this supports a role of IRE1α-XBP1 UPR signaling in quality control of the high-rate production of Igs during plasma cell differentiation. However, the induction pattern of the chop gene, a downstream target of the PERK-eIF2α UPR pathway, implies that the PERK-eIF2α UPR arm may not be activated upon terminal B cell differentiation, consistent with the IP and Western blot analysis of PERK activation in LPS-stimulated B cells (Figure 7A).

We previously generated a knock-in mouse with a defect in eIF2α phosphorylation by mutating the Ser51 phosphorylation site in the endogenous eIF2α gene to a non-phosphorylatable Ala residue (25). To directly investigate whether PERK-eIF2α UPR signaling is required for B lymphopoiesis, fetal hematopoietic liver cells were isolated from the homozygous eIF2α knock-in mutant (Ser51/Ala) embryos at E13.5, and transplanted into the lethally irradiated rag2–/– mice. A normal B220+IgD+ mature B cell population was detected in the spleens of rag2–/– mice reconstituted with homozygous eIF2α knock-in fetal liver cells (Figure 7D). To confirm that the reconstituted splenic B cells were derived from the eIF2α knock-in (eIF2α AA) or WT (eIF2α SS) donor population, the reconstituted B220+ cells were sorted and then stimulated with thapsigargin in vitro. Phosphorylated and total eIF2α protein in the thapsigargin-treated B cells was examined by Western blot analysis (Figure 7E). As control, phosphorylated and total eIF2α protein from thapsigargin-treated eIF2α AA and SS MEFs was included. In the eIF2α AA reconstituted B cells, phosphorylated eIF2α protein was completely absent, which supports the notion that these reconstituted B cells came from the eIF2α knock-in donor population (Figure 7E). Furthermore, production of secreted Ig antibodies was investigated. The rag2–/– mice reconstituted with homozygous eIF2α knock-in fetal liver cells produced normal levels of serum IgG1 and IgM (Figure 7F), suggesting that UPR-mediated translational control through eIF2α is not required for terminal B cell differentiation.

Discussion

We have delineated the physiological roles of IRE1α in the early and late stages of B lymphopoiesis. Our results demonstrate the following: (a) ire1α–/– HSCs can proliferate and reconstitute hematopoiesis and pro–B cells; (b) ire1α–/– pro–B cells are severely defective in VDJ recombination of Ig genes and do not express BCRs; (c) IRE1α regulates expression of the recombination-activating genes rag1, rag2, and the gene encoding TdT in pro–B cells; (d) the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain is required for BCR formation and plasma cell differentiation; (e) the kinase and RNase activities of the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain specifically regulate production of secretory Igs through splicing of XBP1 mRNA; (f) the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain executes an additional function in early B cell differentiation, not dependent on XBP1 mRNA splicing; and (g) IRE1α-mediated, not PERK-eIF2α–mediated, UPR signaling is required for B cell differentiation.

A previous study noted that homozygous ire1α–/– embryos die between days 9.5 and 11.5 of gestation (18). We also observed lethality at E10.5 in homozygous ire1α–/– embryos of a strain with an SVJ129/C57BL/6J mixed background. By backcrossing ire1α+/– SVJ129/C57BL/6J mice with C57BL/6J mice, we obtained ire1α+/– mice with more C57BL/6J strain background. These ire1α+/– mice were used to generate ire1α–/– embryos that could survive until E12.5. This background enabled us to collect enough definitive hematopoietic cells from ire1α–/– embryos for reconstitution experiments. A comparable number of CD34+c-kit+ HSCs could be detected in the AGM region and fetal liver of ire1α–/– embryos (Figure 2, A and B). These ire1α–/– cells colonized hematopoiesis in vitro (Figure 2C) and reconstituted lymphocyte progenitors and pro–B and early pre–B cells in vivo (Figure 3A), thus providing validity for the investigation of roles of IRE1α in the early stage of lymphocyte differentiation. The ire1α–/– fetal hematopoietic cells were able to differentiate into CD43+B220+ pro–B and early pre–B cells but were defective in BCR expression in the reconstituted rag2–/– mice (Figure 3, A and E). Inspection of Ig gene rearrangements revealed a decreased level of DH–JH heavy chain rearrangements and severe defects in proximal VDJ rearrangements (V7183–JH and VQ52–JH) in the ire1α–/– pro–B and early pre–B (B220+c-kit+) cells (Figure 4A). Apparently, the defects of Ig gene rearrangements in the ire1α–/– cells became increasingly severe as the rearrangements progressed through DH–JH to VH–DJH. Furthermore, the impaired VDJ rearrangements in ire1α–/– cells were not due to defective lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation, induction of Ig-specific transcription factors, or expression of IgM molecule accessory proteins (Figure 4, D and E). However, IRE1α-deficient B220+c-kit+ cells had significantly reduced expression of the lymphocyte DNA recombination–activating genes rag1 and rag2 and the gene encoding TdT (Figure 4F). The defective expression of rag1 and rag2 genes could account, at least partially, for the defect in Ig gene rearrangement in ire1α–/– pro–B and early pre–B cells that subsequently results in defective BCRs (Figure 3E). This result implies that IRE1α may regulate the transcriptional efficiency of rag1, rag2, and TdT genes at the point when Ig gene rearrangements initiate.

The role of IRE1α in B cell differentiation was further studied by reconstitution of bone marrow cells expressing trans-dominant-negative mutant forms of IRE1α in rag2–/– mice. The rag2–/– mice reconstituted with bone marrow cells expressing an IRE1α cytoplasmic domain deletion showed a significant decrease in B220+IgM+ B cells in the spleen (Figure 5B), consistent with our observations from fetal hematopoietic cell reconstitution that support the hypothesis that IRE1α is required for BCR formation. Moreover, deletion of the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain decreased production of serum IgM and IgG1 more than 10-fold in reconstituted rag2–/– mice. The defects in BCRs and secreted Ig in mice expressing the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain deletion were rescued by expression of WT IRE1α (Figure 5, B and D); this suggests essential requirements for the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain in early B lymphopoiesis to form BCRs and in terminal B cell differentiation to form plasma cells.

IRE1α has a kinase domain and an RNase domain in the cytosol. Accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER induces IRE1α trans-autophosphorylation to activate its RNase activity (11, 54). In the absence of IRE1α kinase or RNase catalytic activity, B cells progressed through VDJ recombination and class-switch recombination (Figure 6, B and D) but had a distinct defect in production of secreted Ig (Figure 6C). The kinase or RNase dominant-negative mutant B cells formed a normal IgM+IgD+ mature B cell population in the reconstituted rag2–/– mice and expressed normal levels of secretory IgM, IgG2b, and IgG3 transcripts upon LPS treatment, suggesting that the defect of secreted Igs in the IRE1α kinase or RNase dominant-negative reconstituted mice was not due to a decrease in the number of BCRs and/or mature B cells (Figure 6, B and D). Importantly, spliced XBP1 completely restored, and even increased, Ig production in IRE1α kinase or RNase mutant B cells (Figure 6F), indicating that IRE1α kinase and RNase specifically regulate plasma cell differentiation through spliced XBP1. In contrast to the phenotype of B cells that lack IRE1α kinase or RNase activities, B cells with the deletion of the whole IRE1α cytoplasmic domain were defective in BCR formation, and this defect was not rescued by expression of spliced XBP1 (Figure 5, B and F, and Figure 6, B and F). These results suggest that, in addition to its role in regulating production of secreted Igs through the kinase and RNase activities, the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain may regulate BCR formation through a different mechanism independent of XBP1 mRNA splicing.

A previous study reported that the cytoplasmic domain of activated IRE1α recruits the adaptor protein TRAF2, leading to activation of JNK (18). Deletion of TRAF2 produced a defect in B cell lymphopoiesis (58), similar to that reported here for deletion of the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain. Whether the IRE1α cytoplasmic domain recruits TRAF2 or a similar factor that provides an essential role in early B lymphopoiesis remains to be investigated. Although we have not elucidated the detailed mechanism for this signaling pathway, we believe that the identification of a novel role for the UPR sensor IRE1α in stimulating Ig gene rearrangements provides an important novel mechanism for signaling across intracellular compartments. The growth arrest and DNA damage (GADD) response overlaps with the UPR and that agents that activate GADD gene expression also activate the UPR (59). Elucidating the mechanism for the defect of Ig gene rearrangements in the ire1α–/– pro–B cells may provide fundamental insight into how DNA damage, a process that activates DNA recombination and DNA repair, may be sensed through the UPR.

Our studies have also elucidated activation of IRE1α-mediated UPR signaling during plasma cell differentiation. Recent analysis of XBP1 mRNA splicing during plasma cell differentiation implied that the induction of Ig heavy chain synthesis elicits IRE1α activation (28–30). Indeed, we demonstrated that LPS treatment of primary B cells increased secretory IgM transcripts prior to an increase in EDEM expression, which requires the IRE1α-XBP1 portion of the UPR pathway (Figure 7, B and C). However, direct analysis revealed that IRE1α activation occurred from the early stage of plasma cell differentiation, at a time prior to the increase in Ig synthesis and splicing of XBP1 mRNA (Figure 7, A and B). These findings suggest that IRE1α may signal to initiate plasma cell differentiation prior to high-level Ig production. Alternatively, it is possible that incomplete or out-of-frame rearranged Ig genes encode proteins that cannot correctly fold and then subsequently activate the IRE1α-mediated UPR pathway at early stages of B cell development.

Mammalian cells have evolved additional sensors to transduce UPR signaling. In addition to the UPR pathway mediated by IRE1 and ATF6, the ER-localized protein kinase PERK is also activated to phosphorylate eIF2α to maintain ER homeostasis under stress (24). The luminal domains of PERK and IRE1 respond to ER stress by a common mechanism that may involve dissociation of these sensors from the protein chaperone BiP (60). Indeed, the luminal domains of PERK and IRE1α are functionally interchangeable (61). Interestingly, while IRE1α-mediated signaling was indispensable for B cell differentiation, fetal hematopoietic cells with a defect in eIF2α phosphorylation, the downstream effector of the PERK-mediated UPR signaling pathway, were able to reconstitute mature B cells and serum Ig expression in rag2–/– mice (Figure 7, D and F). These results demonstrate that the PERK-eIF2α arm of the UPR is not required for B lymphocyte differentiation and suggest that UPR components are selectively required in differentiation of specialized cells. It is important to note that the results support the hypothesis that the physiological UPR is distinct from the UPR triggered by pharmacological agents or conditions that severely disrupt homeostasis of the ER.

Our studies have elucidated that IRE1α is required for development of early-stage B lymphocytes and for terminal differentiation of B cells into plasma cells through 2 different mechanisms (Figure 7G). Our study has raised several immediate and important questions. First, how does IRE1α regulate induction of rag1, rag2, and TdT genes during VDJ recombination of Ig genes? Does this process require transmitting a signal from the lumen of the ER? Since VDJ recombination occurs normally in xbp1–/– B cells (27), the IRE1α requirement for activation of gene recombination events does not require XBP1 splicing. Therefore, what are the downstream effectors of IRE1α in regulation of early B cell differentiation? Our results show that the cytoplasmic domain, but not the kinase or RNase catalytic activities, is required and suggest that IRE1α functions as a molecular scaffold required for transcriptional activation of rag1, rag2, and TdT genes. In this context, it is interesting to note that the majority of IRE1α is localized to the inner leaflet of the nuclear envelope (22), a location that has access to the transcriptional machinery. Intriguingly, the yeast IRE1α homologue interacts with the transcriptional activator ADA5, a component of the SAGA histone acetyltransferase complex (62). Therefore, IRE1α may be directly acting to assemble transcription complexes. Second, our studies support the idea that IRE1α is activated prior to the increase in expression of IgM transcripts upon plasma cell differentiation. What is the sensing mechanism for activating IRE1α upon antigen stimulation of mature B cells? As a proximal transducer of the UPR to maintain homeostasis in the ER, IRE1α may play multiple roles in B lymphocyte differentiation depending on the status of Ig folding, transport, and secretion that occur at different stages of B cell development. Given the unique ability to isolate lymphocytes at specific stages of Ig synthesis, folding, assembly, and transport from the ER, the developmental process of lymphopoiesis is an ideal system for investigating physiological roles of IRE1α and the UPR.

Methods

Mice.

The generation of ire1α+/– mice on the mixed background of SVJ129 and C57BL/6J was previously described (22). Briefly, targeting vector BS-mIRE1α was constructed to delete exons 7–14 of the murine ire1α gene. The targeting vector was introduced into R1 ES cells derived from SVJ129 mice by electroporation. The ES cell clones were injected into blastocysts harvested from pregnant C57BL/6J mice and transferred to pseudopregnant females, thus producing chimeric offspring. Rag2–/– mice [C.129S6(B6)-RAG2tm1] at the age of 6–8 weeks were purchased from Taconic and maintained in pathogen-free facilities in accordance with the guidelines of the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals at the University of Michigan.

Isolation, transplantation, and culture of fetal liver and AGM cells.

Heterozygous ire1α+/– mice were crossed to produce embryos that were removed at E10.5–E12. The hematopoietic tissue from the AGM region and fetal liver was isolated as previously described (63). For each embryo, the yolk sac was collected for genotyping, and fetal hematopoietic tissues were disrupted into a cell suspension. Fetal hematopoietic cells (4 × 106 to 10 × 106) were transplanted into lethally irradiated (900 rad) rag2–/– mice through tail vein injection. The ratio of the number of AGM cells to that of fetal liver cells used for transplantation was 2:1. Primary culture of the AGM and fetal liver cells was performed as described previously (35, 37). In brief, fetal liver cells isolated from WT embryos at E14.5 were used as hematopoietic stromal cells. The cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 15% FCS in the presence of various cytokines: 100 ng/ml SCF, 1 ng/ml bFGF (GIBCO; Invitrogen Corp.), 10 ng/ml murine leukemia inhibitory factor (mLIF), and 10 ng/ml murine oncostatin M. Two days later, the AGM region and fetal liver from either WT or IRE1α knockout embryos at E10.5–E12 were dissociated into a single-cell suspension by trypsin digestion and then overlaid onto the hematopoietic stromal cells. After 10 days of incubation, nonadherent hematopoietic cells spontaneously generated in cultures were harvested and analyzed for proliferation rates or expression of cell surface markers.

BrdU labeling of fetal liver cells.

For in vivo labeling of mouse fetal liver cells, pregnant mice were injected i.p. with 10 mg BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS. Embryos were harvested after 2 hours of injection and fixed in Carnoy’s fixative buffer. After embedding in paraffin and sectioning, detection of BrdU-labeled cells was performed according to the manufacturer’s procedures (BD Biosciences — Pharmingen).

Flow cytometry analysis and sorting.

Single-cell suspensions from AGM, fetal liver, bone marrow, or spleen were prepared as previously described (63). Cells were stained with PE- or FITC-conjugated antibodies to CD34, c-kit, B220, HSA, BP-1, IgM, IgD, CD4, CD8, TER119, and Mac-1 (BD Biosciences — Pharmingen), and then analyzed with FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and WinMDI software. The B220+ primary B cells, CD43+B220– progenitor cells, and B220+c-kit+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry from splenocytes or bone marrow cells.

Lentivirus transduction of bone marrow cells and transplantation.

The human IRE1α dominant-negative plasmids, IRE1α °C, IRE1α K599A, and IRE1α K907A, were constructed as previously described (13, 53). IRE1α cDNA and dominant-negative DNA fragments were subcloned into the bicistronic GFP-expressing lentiviral vector FG12-CMV, provided by Maria Soengas (Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Michigan). The FG12-CMV vector was constructed by cloning of the CMV promoter into the lentiviral vector FG12 at the XbaI and XhoI sites (64, 65). The retrovirus vector overexpressing spliced XBP1 was kindly provided by Laurie Glimcher (School of Public Health, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts, USA). We used calcium phosphate–mediated transfection of viral vector DNA into HEK-293 T cells to produce lentivirus (65). Briefly, HEK-293 T cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FCS and penicillin/streptomycin for 24–36 hours. The cells were cotransfected with appropriate amounts of vector plasmid, the HIV-1 lentiviral packing constructs pRSVREV (66) and pMDLg/pRRE (66), and the VSV-G–expressing plasmid pHCMVG (67). Bone marrow cells were isolated from WT mice (C57BL/6J) at the age of 5–8 weeks and precultured in DMEM containing 15% FBS, 10 ng/ml IL-3, 50 ng/ml IL-6, and 100 ng/ml SCF for at least 48 hours. The bone marrow cells were then infected by lentivirus in the presence of 6 μg/ml polybrene. After infection, bone marrow cells expressing GFP were sorted by flow cytometry. Approximately 5 × 106 GFP-positive cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated rag2–/– mice by tail vein injection. Retrovirus expressing spliced XBP1 protein was produced and used to infect B cells as previously described (30).

ELISA.

Blood serum samples were obtained via tail snipping from the reconstituted rag2–/– mice. Serum IgM and IgG1 levels of reconstituted mice or secreted IgM and IgG1 from cultured B cells were quantified by duplicated ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bethyl Laboratories Inc). Levels of secreted IgM and IgG1 in the virally transduced B cells were normalized to the quantity of GFP-positive B cells.

Genotyping and quantification of rag2–/– and ire1α–/– cells in the reconstituted populations and organs.

Genotyping of rag2–/– cells was as previously described (40). The primer sequences were as follows: Rag A, 5′-GGGAGGACACTCACTTGCCAG-3′; Rag B, 5′-AGTCAGGAGTCTCCATCTCAC-3′; Neo A, 5′-CGGCGGGAGAACCTGCGTGCAA-3′. Multiplex PCR was designed to genotype the ire1α–/– cells by amplifying exon 7 of the murine ire1α gene and neo gene from the targeting vector. PCR primers 5′-TCCCACTTTGTGTCCAATGGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTCTTGGCCTCTGTCTCCTT-3′ (reverse) were used to amplify a 200-bp fragment from exon 7 of the murine ire1α gene, and the primers 5′-AGGATCTCCTGTCATCTCACCTTGCTCCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAGAACTCGTCAAGAAGGCGATAGAAGGCG-3′ (reverse) were used to amplify a 500-bp neo gene sequence. For quantification of the donor and recipient cells in the sorted populations from the reconstituted mice, 4 gene alleles, neo(+), ire1α(+), rag2(+), and rag2(–), were calibrated based on the multiplex PCR assay results. Genomic DNAs from the ire1α–/– hematopoietic cells (donor) and rag2–/– bone marrow cells (recipient) were mixed according to ire1α–/– to rag2–/– ratios of 15:1, 10:1, 8:1, 4:1, 2:1, 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8, 1:10, and 1:15. The mixed DNAs were used as templates for amplifying the neo(+), ire1α(+), rag2(+), and rag2(–) alleles. The amplified DNA band for each allele was quantified to establish references to calibrate ratios of donor to recipient cells in the sorted populations based on the multiplex PCR assay results. Southern blot analysis was also used to genotype the IRE1α knockout mice and embryos and to quantify engraftment of the ire1α–/– cells in the bone marrow, spleen, and thymus. Genomic DNA (10–15 μg) from tails or yolk sac was digested with BamHI and then resolved by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels and transferred to Hybond membranes according to standard procedures (68). The membranes were hybridized with a 32P-labeled 0.5-kb BamHI/XhoI fragment that is outside and adjacent to the end of the short arm of the IRE1α targeting vector. The WT and ire1α knockout mice or embryos were distinguished by a 3-kb ire1α WT allele and a 4-kb ire1α recombinant allele, respectively. To detect amounts of ire1α–/– or ire1α+/– cells in the reconstituted organs, 15 μg genomic DNA from reconstituted bone marrow, thymus, or spleen was digested with BamHI for Southern blot using the same probe as described above. The rates of engraftment of the ire1α–/– or ire1α+/– cells were determined by quantification of ire1α recombinant allele in the genomic DNA isolated from the reconstituted organs.

Ig gene rearrangement assay and semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis.

For analysis of Ig gene rearrangements, B220+c-kit+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry from the reconstituted bone marrow. The B220+ bone marrow cells sorted from bone marrow of the WT mouse served as a positive control. DNA and total RNA were isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Corp.). DNA purified from the sorted cells was used to amplify rearranged D–JH, V7183–JH, and VQ52–JH for Ig gene rearrangement analysis as previously reported (43, 45, 69). The following primers were used in these experiments: 5′-ACAAGCTTCAAAGCACAATGCCTGGCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTCTCAGCCGGCTCCCTCAGGG-3′ (reverse) were used to amplify DH–JH; 5′-GCAGCTGGTGGAGTCTGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACAAGCTTCAAAGCACAATGCCTGGCT-3′ (reverse) were used to amplify V7183–JH; and 5′-TCCAGACTGAGCATCAGCAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACAAGCTTCAAAGCACAATGCCTGGCT-3′ (reverse) were used to amplify VQ52–JH. PCR amplification products were detected and quantified by Southern blot hybridization with 32P-labeled DNA fragments corresponding to the appropriate Ig constant region as previously described (45, 69). Total RNA isolated from the B220+c-kit+ or B220+ bone marrow cells or from the reconstituted splenic B cells was used to examine induction of various genes in the early stage and late stage of B cells by semiquantitative RT-PCR. The primers for detecting VDJ-Cμ transcript were 5′-CGCGCGGCCGCTGCAGCAGCCTGGGGCTGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGAATGGGCACATGCAGATCTC-3′ (reverse). The primers for detecting secretory IgMμ transcript were 5′-TGTGTGTACTGTGACTCACAGGGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGGGAGACATTGTACAGTGTGGGT-3′ (reverse). The other primers used for semiquantitative RT-PCR in Figure 4, B–F, and Figure 7C were as previously reported (22, 27, 30, 70, 71).

IP–Western blot analysis.

For analysis of expression and phosphorylation of IRE1α or PERK protein, total cell lysates were prepared from primary B cells or MEFs using NP-40 lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% SDS) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche Diagnostics GmbH), 0.1 mM sodium vanadate, and 1 mM sodium fluoride. Cell lysates were collected from the primary splenic B cells (B220+) that were treated with 20 μg/ml LPS for various time periods. IP–Western blot analysis of IRE1α protein in the LPS-treated B cells were performed using an antibody against the lumenal domain of human IRE1α as previously described (22). WT and ire1α–/– MEFs and WT primary B cells were treated with 0.5 μM thapsigargin for IRE1α protein controls in the IP–Western blot. The same B cell lysates used for IRE1α IP–Western blot were immunoprecipitated by a polyclonal rabbit anti-PERK PITK-289 antibody (kindly provided by Yuguang Shi, Lilly Research Laboratories, Eli Lilly and Co., Indianapolis, Indiana, USA), and then subjected to Western blot analysis using the same antibody. WT and perk–/– MEFs (kindly provided by David Ron, New York University, New York, New York, USA) and WT primary B cells were treated with thapsigargin for the controls in the PERK IP–Western blot analysis. Western blot analysis of phosphorylated eIF2α was performed using an eIF2α Ser51 phosphospecific antibody (BioSource International). Western blot analysis of total eIF2α protein was performed as previously described (25). The antibody for XBP1 Western blot analysis was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.

Real-time PCR.

Total cellular RNA was prepared using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Corp.) as recommended by the manufacturer. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using a random primer (Applied Biosystems). The reaction mixture, containing SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), was run in a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR primer sequences were designed by Primer Express (Applied Biosystems).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank L. Glimcher, D. Ron, Y. Shi, and M. Soengas for various reagents, D. Fang and T. Rutkowski for their critical reading of the manuscript, and the members of the Kaufman laboratory for their important input. Portions of this work were supported by NIH grant DK42394 (to R.J. Kaufman).

Footnotes

See the related Commentary beginning on page 224.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: AGM, aorta-gonad-mesonephros; BCR, B cell receptor; b-ZIP, basic leucine zipper; EDEM, ER-associated degradation–enhancing mannosidase-like protein; eIF2α, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α; HSA, heat-stable antigen; IRE1, inositol-requiring enzyme 1; MEF, murine embryonic fibroblast; Neo, neomycin; PERK, ER-resident eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α kinase; RAG, recombinase-activating gene; TdT, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase; TRAF2, TNF receptor–associated factor 2; UPR, unfolded protein response; XBP1, X-box–binding protein 1.Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Hardy RR, Hayakawa K. B cell development pathways. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001;19:595–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calame KL. Plasma cells: finding new light at the end of B cell development. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:1103–1108. doi: 10.1038/ni1201-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meffre E, Casellas R, Nussenzweig MC. Antibody regulation of B cell development. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1:379–385. doi: 10.1038/80816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox JS, Walter P. A novel mechanism for regulating activity of a transcription factor that controls the unfolded protein response. Cell. 1996;87:391–404. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harding HP, Calfon M, Urano F, Novoa I, Ron D. Transcriptional and translational control in the Mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2002;18:575–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.011402.160624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sitia R, Braakman I. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum protein factory. Nature. 2003;426:891–894. doi: 10.1038/nature02262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaufman RJ. Stress signaling from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: coordination of gene transcriptional and translation controls. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1211–1233. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nikawa JI, Yamashita S. IRE1 encodes a putative protein kinase containing a membrane-spanning domain and is required for inositol phototrophy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 1992;6:1441–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox JS, Shamu CE, Walter P. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell. 1993;73:1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90648-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mori K, Ma W, Gething MJ, Sambrook J. A transmembrane protein with a cdc2+/CDC28-related kinase activity is required for signalling from the ER to the nucleus. Cell. 1993;74:743–756. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90521-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shamu CE, Walter P. Oligomerization and phosphorylation of the Ire1p kinase during intracellular signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus. EMBO J. 1996;15:3028–3039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawahara T, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced mRNA splicing permits synthesis of transcription factor Hac1p/Ern4p that activates the unfolded protein response. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997;8:1845–1862. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.10.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tirasophon W, Welihinda AA, Kaufman RJ. A stress response pathway from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus requires a novel bifunctional protein kinase/endoribonuclease (Ire1p) in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1812–1824. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang XZ, et al. Cloning of mammalian Ire1 reveals diversity in the ER stress responses. EMBO J. 1998;17:5708–5717. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–891. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calfon M, et al. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature. 2002;415:92–96. doi: 10.1038/415092a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen X, et al. Complementary signaling pathways regulate the unfolded protein response and are required for C. elegans development. Cell. 2001;107:893–903. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00612-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urano F, et al. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haze K, Yoshida H, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:3787–3799. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye J, et al. ER stress induces cleavage of membrane-bound ATF6 by the same proteases that process SREBPs. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1355–1364. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen J, Chen X, Hendershot L, Prywes R. ER stress regulation of ATF6 localization by dissociation of BiP/GRP78 binding and unmasking of Golgi localization signals. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee K, et al. IRE1-mediated unconventional mRNA splicing and S2P-mediated ATF6 cleavage merge to regulate XBP1 in signaling the unfolded protein response. Genes Dev. 2002;16:45–66. doi: 10.1101/gad.964702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]