Abstract

During Salmonella Typhimurium infection intestinal CX3CR1+ cells can either extend transepithelial cellular processes to sample luminal bacteria or, very early after infection migrate into the intestinal lumen to capture bacteria. However, up to date, the biological relevance of the intraluminal migration of CX3CR1+ cells remained to be determined. We addressed this by using a combination of mouse strains differing in their ability to carry out CX3CR1-mediated sampling and intraluminal migration. We observed that, the number of S. Typhimurium traversing the epithelium did not differ between sampling-competent/migration-competent C57BL/6 and sampling-deficient/migration-competent Balb/c mice. By contrast, in sampling-deficient/migration-deficient CX3CR1-/- mice the numbers of S. Typhimurium penetrating the epithelium were significantly higher. However, in these mice the number of invading S. Typhimurium was significantly reduced after the adoptive transfer of CX3CR1+ cells directly into the intestinal lumen, consistent with intraluminal CX3CR1+ cells preventing S. Typhimurium from infecting the host. This interpretation was also supported by a higher bacterial faecal load in CX3CR1+/gfp compared to CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice following oral infection. Furthermore, by using real time in vivo imaging we observed that CX3CR1+ cells migrated into the lumen moving through paracellular channels within the epithelium. Also, we reported that the absence of CX3CR1-mediated sampling did not affect antibody responses to a non-invasive S. Typhimurium strain that specifically targeted the CX3CR1-mediated entry route. These data showed that the rapidly deployed CX3CR1+ cell-based mechanism of immune-exclusion is a defence mechanism against pathogens that complements the mucous and secretory (s)IgA antibody-mediated system in the protection of intestinal mucosal surface.

Introduction

One of the main tasks of the epithelium overlying mucosal surfaces of the intestinal tract is to provide an effective barrier to microorganisms present in the intestinal lumen. Firstly, this is achieved by the presence of tight junctions that allow the passage of water and ions but provide an effective mechanical barrier to macromolecules and microbes (1). Secondly, a combination of thick flowing mucus and secretory (s)IgA bathing mucosal surfaces provide an efficient gel that sequestrates harmful microorganisms and prevent them from crossing the epithelial barrier in a process known as immune-exclusion (2, 3). Furthermore, it has been recently shown that a few hours after infection the epithelium-intrinsic NAIP/NLRC4 inflammasone drove the expulsion of infected epithelial cells to restrict S. Typhimurium replication in the mucosa (4). Ultimately, the aim of these protective mechanisms is to prevent pathogens from traversing/colonizing the intestinal mucosa. We have previously reported that intestinal challenge with S. Typhimurium induced, very shortly after infection the migration into the intestinal lumen of S. Typhimurium-capturing cells expressing the high affinity receptor CX3CR1 for the chemokine fractalkine (CX3CL1) into the intestinal lumen (5), a chemokine that although expressed by a variety of cells is produced at its highest level by the intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) of the ileum (6). The migration of CX3CR1+ cells following challenge with S. Typhimurium was restricted to the small intestine in a flagellin/MyD88-dependent manner and did not affect the integrity of the epithelial barrier (5). These observations prompted us to test the hypothesis that Salmonella-capturing CX3CR1+ cells migrate rapidly into the intestinal lumen to limit the number of pathogens crossing the epithelial barrier. Interestingly, in the occurrence of infection with S. Typhimurium, CX3CR1+ cells displayed a dual behaviour. Indeed, these cells can also directly sample bacteria by using cellular extensions that protrude between epithelial cells and shuttle them across the epithelium to initiate immune responses (7, 8). Importantly, the presence of the fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 appeared to be essential for both events (6, 9). However, while CX3CR1-mediated sampling plays a role in the generation of immune responses (7) the biological relevance of the intraluminal migration of the CX3CR1+ cells during the early stages of infection remained to be determined. We sought to address this issue by using a combination of mouse strains that differed in their ability to undergo CX3CR1-mediated direct sampling and intraluminal migration during S. Typhimurium infection. Indeed, while wild-type (wt) C57BL/6 mice responded to S. Typhimurium with CX3CR1-mediated sampling (8) and migration (5), wt Balb/c mice lacked the ability to sample luminal antigen via this route (sampling-deficient) (10) but were migration-competent (5). Furthermore these two mouse strains were complemented with CX3CR1-deficient mice that were both sampling- and migration-deficient (6, 9). We observed that the rapid Salmonella-induced intraluminal migration of CX3CR1+ cells reduced significantly the bacterial load in the intestinal tissue thus contributing effectively to the immune-exclusion provided by the mucous barrier and sIgA-based system.

Materials and methods

Mice

6-8 week old female CX3CR1gfp/gfp, Balb/c and C57BL/6 background (11) were used as CX3CR1-deficient mice and bred with wt Balb/c or C57BL/6 mice to obtain heterozygotes CX3CR1+/gfp. CX3CR1-/- (C57BL/6 background) were purchase from Taconic and 6-8 week old wt Balb/c and C57BL/6 were purchase from Charles River. Villin-Cre MyD88 (MyD88ΔIEC) (C57BL/6 background) were from the Welcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, UK (12). CX3CR1+/- and CX3CR1-/- on RAG-/- background (B6.129S7-Rag1tm1Mom/J, Jackson Laboratory) were obtained by an intercross between the knock-out mice. Mice on RAG-/- background were kept in SPF high barrier environment. Overall mice were kept under standardized conditions in groups of 3–5/cage. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Experiments were conducted under the guidelines of the Scientific Procedure Animal Act (1986) of the United Kingdom or at the University of Siena under the “Guiding Principles for Research Involving Animals and Human Beings”. Intestinal surgery was performed under terminal anaesthesia induced and maintained throughout the procedure by inhalation of isoflurane.

Bacteria

The S. Typhimurium SL1344 ΔinvA::kan mutant was constructed using the Lambda Red recombination system as described previously (13). Briefly, using primers invARedF (TGAAAAGCTGTCTTAATTTAATATTAACAGGATACCTATA) and invARedR (ATATCCAAATGTTGCATAGATCTTTTCCTTAATTAAGCCC) the entire coding sequence of invA was replaced by a flippase recognition target (FRT)-flanked Km cassette from template plasmid pKD4. Recombinants were selected for kanamycin resistance and verified by PCR. The mutation was subsequently transduced by P22 into a clean SL1344 parent background and into SL3261 (Aro-) to construct the double mutation.

Bacterial challenge

Isolated loops were injected with 1x107 non-invasive/non-replicating InvA-Aro- for intravital imaging experiment or invasive/non-replicating InvA+AroA- S. Typhimurium for collecting intraluminal CX3CR1+/gfp cells for phenotypic and quantitative analysis. Oral challenges were performed by gavages that were delivered five to ten minutes after administration of a solution of NaHCO3 (10% wt/vol/200μl). In order to monitor intraluminal migration of CX3CR1+ cell or bacterial load in the gut tissue within 5h after infection mice received a single oral dose of 1x107 of either InvA+AroA-, InvA-AroA- or InvA-AroA+ S. Typhimurium; to determine long-term (5 days post-infection) bacterial load mice received a single dose of 1x107 of InvA-Aro+ strain. To determine strain-specific susceptibility to S. Typhimurium infection mice received a single dose of 1x108 wt InvA+AroA+ S. Typhimurium; finally to investigate antibody responses to non-invasive S. Typhimurium mice received three doses of 1x108 InvA-Aro- at three day interval. In order to monitor intraluminal migration of CX3CR1+ cells and faecal bacterial load mice received a single oral dose of 1x107 of InvA+Aro- S. Typhimurium. To determine translocation of non-invasive InvA- S. Typhimurium two approaches were undertaken. For short term experiments mice (n=8-10mice/group) were orally administrated with a single dose of InvA-Aro- Salmonella and sacrificed at 30, 60, 180 and 270 minutes post-infection. For long term experiments mice received the same dose of InvA-Aro+ and were sacrificed 5 days post-infection. Tissues (small intestine and PPs for short term experiments; PP, MLN and spleen for long term experiments) were harvested weighted and treated with gentamicin (1h at 37C°). After repeated washings in PBS tissues were homogenized. Serial dilutions of the homogenates were plated on LB agar and incubated overnight at 37C°. To determine antibody responses to non-invasive Salmonella strain mice received 3 doses of 1x108 InvA-AroA- S. Typhimurium at 3 day interval.

Intravital Two-Photon microscopy

Intestinal loops were performed as described (5); mice were then placed on a mouse holder; the temperature of the animals was maintained by an enclosed microscope temperature control system (Life Imaging Services, Basel, Switzerland). Two-photon excitation was done with a Chameleon Ultra II Ti: Sapphire laser and Chameleon Compact OPO (Coherent Inc., USA), and the fluorescence emission was measured with four PMTs with filters for 420/50, 525/50, 595/40 and 655/40 nm. The microscope system and data acquisition were controlled by the Imspector Pro 4.0 software. Image analysis was done with the Fiji/ImageJ package.

Immunofluorescence and transmission electron microscopy

Immunohistochemistry was carried out on 10 μm sections as described in detail elsewhere (14, 15). Briefly, non-specific binding sites were quenched with 5% bovine serum albumin; sections were then incubated with rabbit anti-entactin antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) followed by Cy5-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) for 45 minutes. Sections were counterstained with TRITC-conjugated phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich) and analysed with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope. For TEM analysis, samples were processed according to standard procedure (16) and examined with a Philips 201 electron microscope.

Antibody responses

S. Typhimurium-specific IgG and IgA were detected in serum and faeces. Briefly, serum was obtained after 1h incubation at 37C° and collected after centrifugation. Faecal samples were weighted and resuspended in PBS in presence of proteases inhibitors; debris-free supernatants were then collected after centrifugation. ELISA plates (Costar) were coated with lysate from wt S. Typhimurium obtained as described by others (17). Plates were blocked and then incubated with dilutions of both serum and faecal solution. After washing plate were incubated with anti IgA- and anti IgG-biotinylated antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK); this was followed by incubation with Streptavidin Peroxidase (Abcam). Also, numbers of single IgA-antibody forming cells (AFC) were detected using a modified ELISPOT assay developed in our lab (18) in 96-well membrane ELISPOT plates (Whatman) coated with lysate from wt S. Typhimurium as above.

Flow cytometry and isolation of CX3CR1+ cells

Following bacterial challenge, luminal contents were carefully recovered by gently flushing the intestine with PBS. Intraluminal CX3CR1+/gfp cells were isolated and characterized by flow cytometry as described in details elsewhere (5). Samples were analysed by BD FACSAria II (BD Biosciences). The following antibodies were used: CD11c (HL3) (BD Biosciences), CD103 (M290) (BD Biosciences), CD103 (2E7) (eBioscience), F4/80 (BM8) (eBioscience), MHC II (M5/114.15.2) (eBioscience), SiglecF (E50-2440) (BD Biosciences). For the isolation of CX3CR1+ cells intestinal tissue from CX3CR1+/gfp mice were collected and tissues repeatedly treated with HBSS containing EDTA (2mM). After each treatment tissues were shaken and supernatant discarded. After each wash an aliquot from the supernatant was analysed by microscopy to detect the presence of IECs; EDTA treatment was stopped (usually after 3-4 treatments) when epithelial cells were not present in the supernatant. Tissues were then treated for 50 minutes in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS, 0.24mg/ml collagenase VIII (Sigma) and 40 U/ml DNase I (Roche) as described by others (19) ; after shaking cells suspensions were filtered and then purified by gradient separation as described before (5). Cells were sorted (>95% purity), suspended in PBS and injected into the intestinal lumen for pathogen exclusion assay.

Salmonella Typhimurium-exclusion assay

Experiments of adoptive transfer were performed to assess the ability of CX3CR1 cells to prevent S. Typhimurium from traversing the epithelial barrier. CX3CR1+/gfp and CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice were used as donors and gfp-labelled CX3CR1 cells were isolated as described above. CX3CR1-/- mice (6 mice/group) were used as recipients and they received a single oral dose of 1x107 invasive/non-replicating InvA+AroA- S. Typhimurium approximately 5-10 minutes after the delivery of a solution of NaHCO3 and then anesthetized. Initially four groups of mice were used. Group I was injected in the intestinal lumen with 0.5x103 CX3CR1+/gfp cells approximately 10 minutes after S. Typhimurium infection and sacrificed 30 minutes after infection; tissues were then removed, washed and homogenates plated on LB agar. Group II received the same number of CX3CR1+/gfp cells after 10 minutes; subsequently the number of intraluminal CX3CR1+/gfp cells was increased to 1x104 with a second injection 30 minutes after infection. Mice were sacrificed 90 minutes after the initial S. Typhimurium infection and tissues treated as for group I. In group III mice received a total of 4.5x104 S. Typhimurium in three injections administrated 10, 30 and 90 minutes after infection. This group of mice was sacrificed and tissue removed 120 minutes after infection. Group IV was treated as group I with the difference that the mice received 1x104 CX3CR1+/gfp cells after 10 minutes; mice were sacrificed 30 minutes post-infection. At each injection cells were equally divided into two injection sites approximately 1 cm and 3 cm from the pylorus. The same protocol was repeated in additional four groups of CX3CR1-/- mice (V-VIII) that received adoptive transfer of CX3CR1gfp/gfp cells

Permeability assay

Intestinal permeability to soluble (dextran) and particulate antigen (polystyrene micro particles) was measured in 6-8 week old CX3CR1gfp/gfp, CX3CR1+/gfp and syngeneic wt mice (4 mice/group). FITC-labelled dextran (FD4; Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in PBS at a concentration of 100 mg/ml and administered to each mouse (44 mg/100 g body weight) by oral gavage. Blood samples were collected after 6 hours and the plasma analysed for FD4 concentration using fluorescence spectrometer at an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and emission wavelength of 520 nm. Intestinal transport of polystyrene particles (Fluoresbrite YG Carboxylate Microspheres, 0.50µm) was assessed as described in detail elsewhere (20)

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SD and statistical comparison made by the Student’s unpaired t-test; p values were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Bacteria translocation is increased in mice lacking intraluminal migration of CX3CR1+ cell but not antigen-sampling via the indirect route

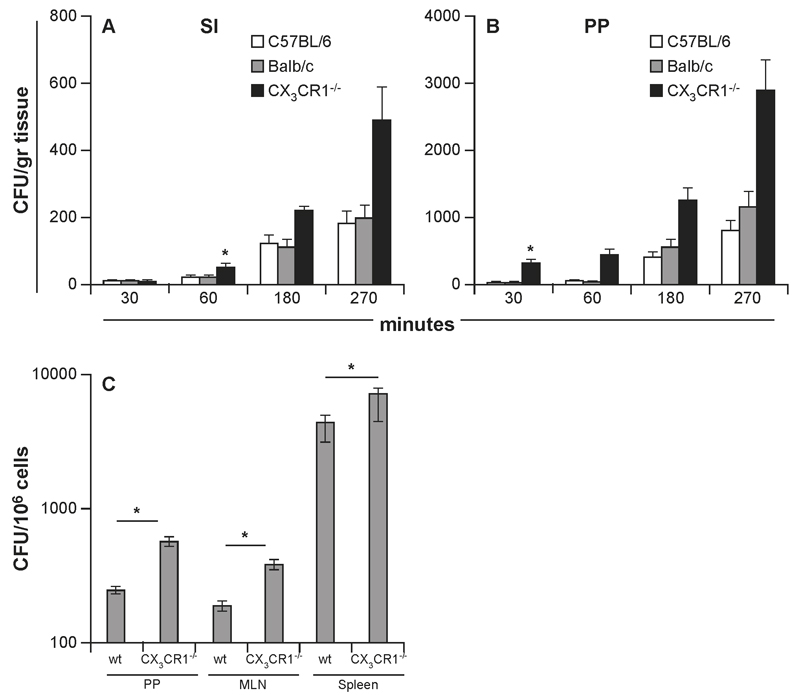

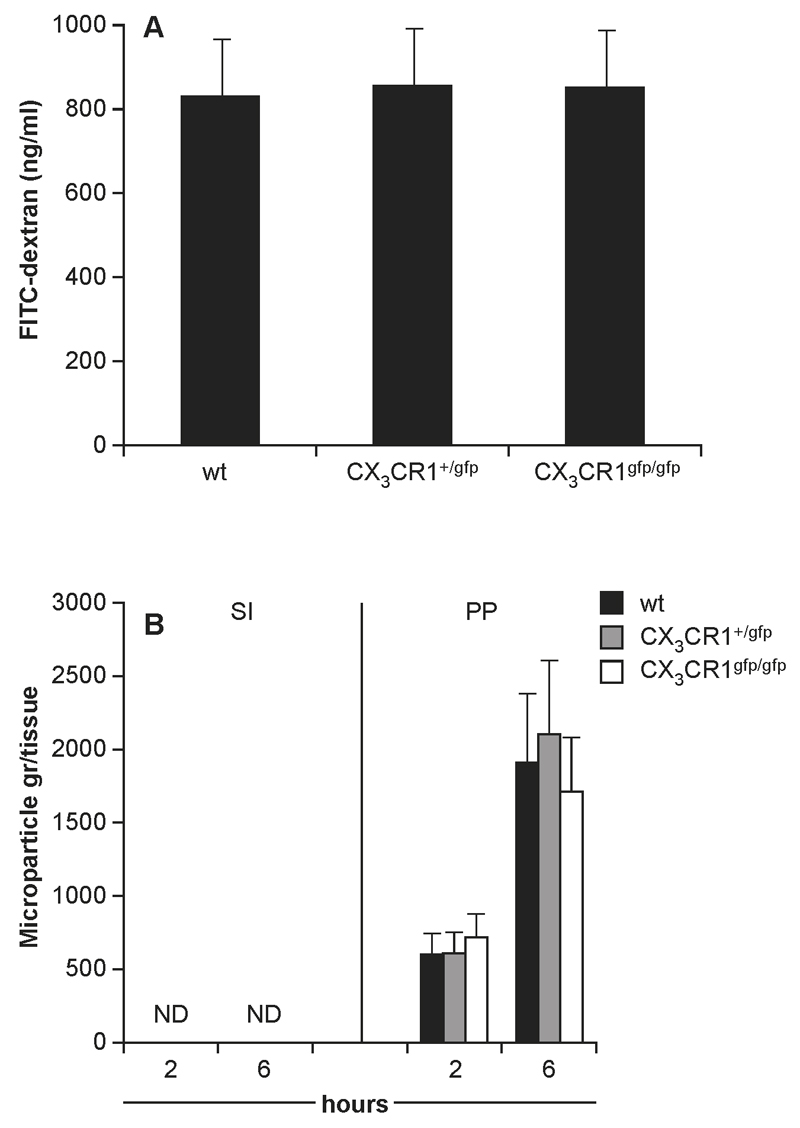

Translocation of InvA- S. Typhimurium was investigated in mouse strains either able (C57BL/6) (8) or unable (CX3CR1-/- or Balb/c) to sample luminal bacteria via the indirect route (6, 10; Supplemental Fig 1A-B). Following oral delivery of InvA- S. Typhimurium antigen sampling-competent/migration-competent C57BL/6 and sampling-deficient/migration-competent Balb/c had similar numbers of S. Typhimurium penetrating both the conventional epithelium of the small intestine (SI) and the specialized follicle-associated (FAE) epithelia of Peyer’s patches (PPs) (Fig. 1A-B) at any time point during the initial stages of the infection. By contrast, sampling-deficient/migration-deficient CX3CR1-/- mice showed significantly higher numbers of bacteria after 30 and 60 minutes post infection within the PPs and the small intestinal lamina propria that remained significantly higher throughout the experiment. In addition, the number of replicating InvA-AroA+ S. Typhimurium recovered from PP, mesenteric LN and spleen 5 days after oral delivery was higher in CX3CR1-/- mice compared to their wt counterparts (Fig 1C). Increased bacterial translocation across the gut epithelium in CX3CR1-deficient mice (both CX3CR1-/- and CX3CR1gfp/gfp) was not the result of increased permeability of the epithelial barrier as shown by using soluble tracer and microparticles (Fig. 2A-B). Indeed, serum levels of orally delivered fluorescent FITC-dextran (Fig 2A) and numbers of orally delivered FITC-labelled latex microparticles (Fig 2B) were similar to wt mice. Increased bacterial transport in the gut of CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice was also seen following infection with InvA+ S. Typhimurium. Confirming a previous report (6) CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice succumbed 7 days after oral delivery of lethal dose of invasive S. Typhimurium at a significantly faster rate compared to their CX3CR1+/gfp counterparts (Supplemental Fig. 2A) and showed higher bacterial load in their organs (Supplemental Fig. 2B). Also, to rule out that some effects of CX3CR1 deficiency on bacterial translocation might be related to altered activation of adaptive immune responses we assessed bacterial translocation in CX3CR1+/- and CX3CR1-/- on RAG-/- background. We observed that the RAG-/- background did not affect bacterial translocation (Supplemental Fig 2C). These results taken together would suggest that antigen-sampling via the indirect route does not play a significant role in S. Typhimurium up-take, at least at the initial stage of infection; instead it appeared that the lack of Salmonella-induced CX3CR1+ cells intraluminal migration favoured bacterial translocation.

Fig. 1. Role of CX3CR1-mediated sampling and migration in the uptake of non-invasive InvA- S. Typhimurium.

Typhimurium. Numbers of S. Typhimurium traversing the conventional (A) (small intestine, SI) and specialized (B) (Peyer’s patches, PP) epithelia did not differ in mouse strains that have been shown to be either sampling-competent/migration-competent (C57BL/6) or sampling-deficient/migration-competent (Balb/c). In contrast, S. Typhimurium uptake was significantly higher in CX3CR1-/- mice that were both sampling-deficient and migration-deficient (8 mice/group). Similarly higher numbers of S. Typhimurium were found to be higher in the GALT (PP and MLN) and spleen of CX3CR1-/- mice compared to wt mice (10 mice/group), 6 days after a single oral delivery of non-invasive-replicating InvA-Aro+ S. Typhimurium. Asterisk (*) indicates significant statistical difference.

Fig. 2. Intestinal permeability in CX3CR1-deficient mice.

Oral delivery of a single dose of either FITC-dextran (A) or yellow-green fluorescent polystyrene microparticles (B) showed that intestinal permeability to both soluble and particulates tracers was not affect by the lack of functional fraktalkine receptor (4 mice/group). This demonstrates that the higher bacterial load in the intestine as shown in Fig 1 could not be attributed to an intrinsic “leaky” gut in CX3CR1-/- mice. Asterisk (*) indicates significant statistical difference

Intraluminal cell migration is triggered by epithelium-derived signals and it is higher in response to invasive S. Typhimurium

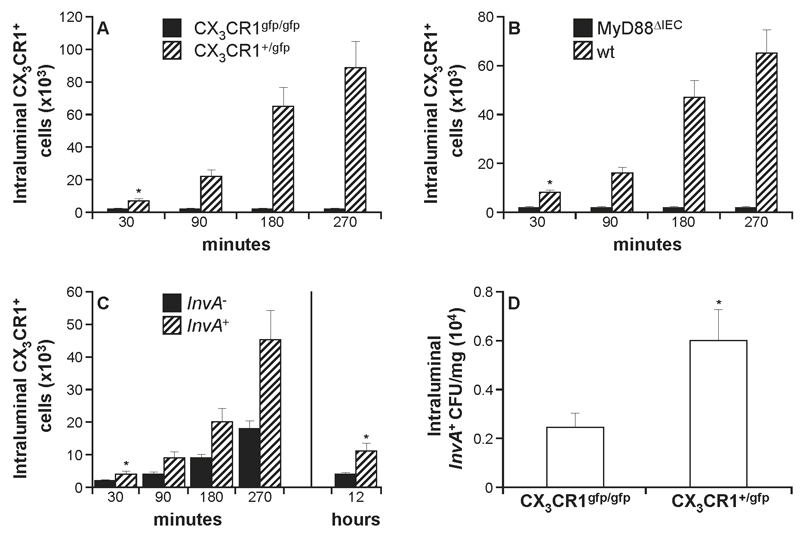

The potential critical role of intraluminal CX3CR1+ cells in controlling pathogen up-take prompted us to investigate this event in detail. First, we determined whether Salmonella-induced CX3CR1+ cell migration was abolished or simply delayed in CX3CR1-deficient mice. After the introduction of InvA- S. Typhimurium into isolated intestinal loops of CX3CR1+/gfp mice the number of CX3CR1+ cells appearing in the gut lumen 30 minutes post infection (Fig. 3A) reached 0.71x104 ± 1.2x103 which was approximately >30 fold higher than levels seen in CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice (1.3x102 ± 1x102). The numbers of intraluminal CX3CR1+ cells increased steadily between 90 and 270 minutes reaching 8.9x104±5x103. In contrast, no increase in the number of intraluminal CX3CR1+ cells was observed in CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice at any time point after infection showing that, the migration is completely abolished in mice lacking a functional fractalkine receptor. Furthermore, we assessed the role of epithelium-derived signals in the migration of CX3CR1+ cells in response to S. Typhimurium. To this end, MyD88ΔIEC mice that lacked the adaptor molecule MyD88 solely in the intestinal epithelial cells (IEC) were challenged with S. Typhimurium. The migration was completely suppressed in MyD88ΔIEC mice compared to syngeneic wt counterparts (1.5x102±1x102 and 6.5x104±1.1x104 respectively at 5h post infection) (Fig. 3B) thus showing that signals from IEC-associated TLRs are the triggering event. We then evaluated the migration of CX3CR1+ cells in response to oral delivery of S. Typhimurium strains that differed in their capacity to invade the host. Intraluminal migration in CX3CR1+/gfp mice (Fig. 3C), was significantly higher after infection with the invasive S. Typhimurium strain (4.3.x102±1.2x102) compared to non-invasive strain (2.1.x102 ± 1x102) already within 30 minutes post-infection. The number of intraluminal cells steadily increased with time and, after 5h it reached 4.4x104±9x103 and 1.7x104±1.2x103 cells for invasive and non-invasive S. Typhimurium, respectively. Migration was significantly reduced in response to both S. Typhimurium variants at 12h post-infection consistent with intraluminal migration of CX3CR1+ cells being restricted to the initial stage of infection. We previously reported that CX3CR1+ cells were the only intraluminal cell population harbouring intracellular S. Typhimurium shortly after infection (5) suggesting a possible role in Salmonella-exclusion. In agreement with this interpretation we observed that at 5h after infection migration-competent CX3CR1+/gfp mice had a significantly higher faecal (excluded) bacteria load compared to migration-deficient CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3. Regulation of S. Typhimurium-induced migration of CX3CR1+ cells.

The role of the fraktalkine CX3CR1 receptor in S. Typhimurium-induced migration was assessed in mice with a functional (CX3CR1+/gfp) or non-functional (CX3CR1gfp/gfp) receptor. Intraluminal migration of CX3CR1+ cells was absent in CX3CR1-deficient mice (A) (7-8 mice/group) that had been challenged with 1x107 InvA- S. Typhimurium The lack of the fraktalkine receptor completely abolished, and not simply delayed the pathogen-induced migration. IEC-derived signals are required for CX3CR1+ cells recruitment and migration; S. Typhimurium-dependent intraluminal recruitment of CX3CR1+ cells was also absent in mice with a target deletion of MyD88 in the IEC (MyD88ΔIEC mice) (B) (5-6 mice group). In (C) it is shown that intraluminal migration is significantly more pronounced in response to oral challenge (1x107) with invasive (InvA+) Salmonella variant. Migration appeared to be restricted at the initial stage of infection and it declined significantly 12h after infection for both invasive and non-invasive strains. The presence of intraluminal CX3CR1+ cells led to a significant increase in faecal bacterial load (D) compared to CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice 5 hours after oral delivery of invasive S. Typhimurium as in (C). Asterisk (*) indicates significant statistical difference.

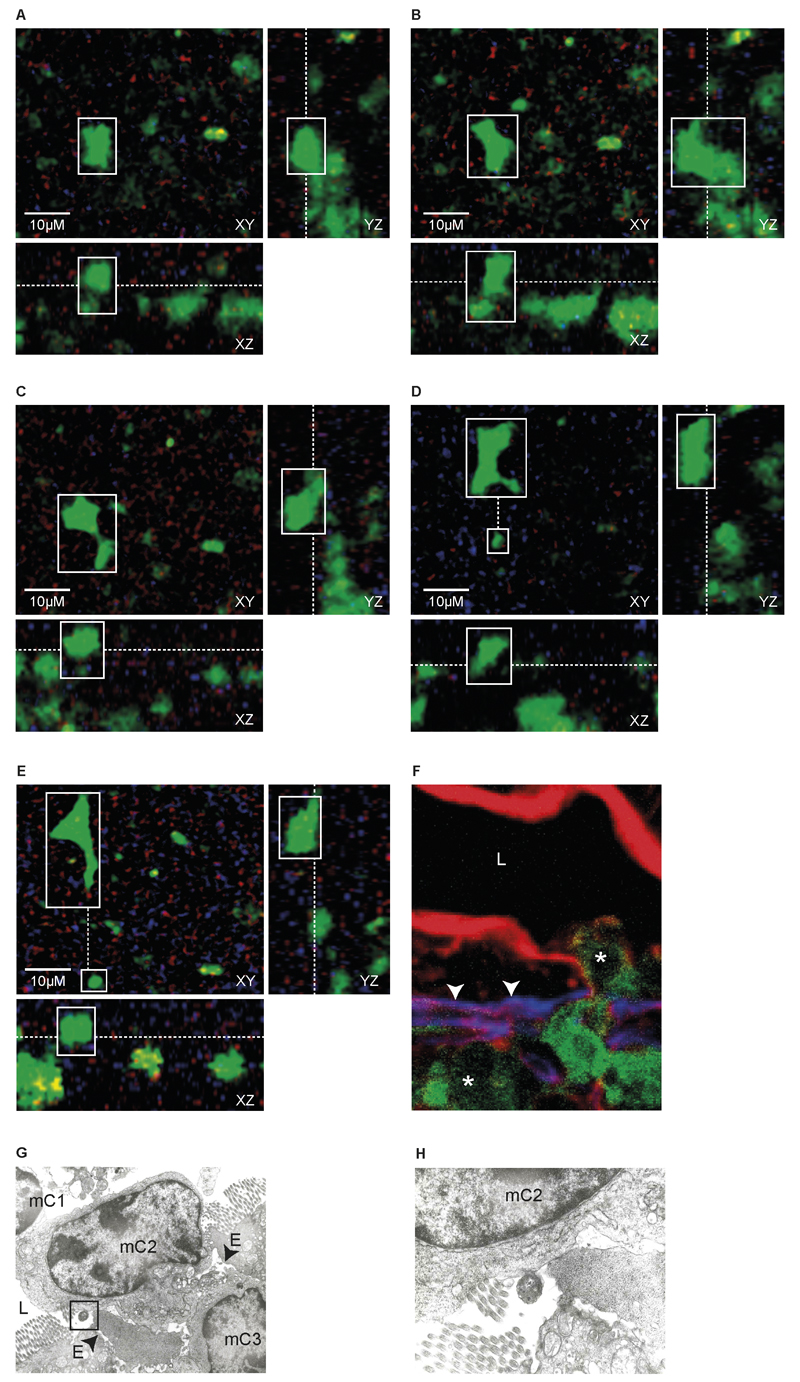

Salmonella-induced migration of CX3CR1+ cells occurred through paracellular channels in the epithelium

Then intravital two-photon microscopy was used to study in detail the transepithelial migration of CX3CR1+ cells in CX3CR1+/gfp mice shortly (3h) after the introduction of InvA- S. Typhimurium into isolated ileal loops. First, the still image (orthogonal cross-sections through the 3D stacks in successive time-frames) (Fig. 4A-E) of the in vivo real time video (Supplemental Movie 1) showed a fluorescent CX3CR1+/gfp cell protruded into the intestinal lumen from the surface of the intestinal epithelium (Fig. 4A) and progressed further into the lumen (Fig. 4B-C) before moving away from the entry site (Fig. 4D-E). It also appeared that the imaged cell was immediately followed by another CX3CR1+/gfp cell migrating via the same opening in the epithelium (Fig. 4D-E, Supplemental Movie 1). This migratory pattern was also investigated by both immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4F) and TEM (Fig. 4G-H). Figure 4G also showed three cells migrating (mC1-3) in single file through paracellular channel into the lumen, one of which (mC2) was in close contact with S. Typhimurium (Fig 4H). The migration of CX3CR1+ cell is unidirectional; after collecting intraluminal CX3CR1+/gfp cells and reintroducing them into freshly isolated intestinal ileal loop we never observed CX3CR1+/gfp cells traversing the epithelial barrier to migrate back into the intestinal tissue. The majority of intraluminal CX3CR1+/gfp cells (Fig. 5) at 5h post-infection displayed the phenotype of gut resident macrophages MHCII+ F4/80+ CD11c+ CD103- SiglecF- that in steady-state situations do not migrate to mesenteric lymph-node, display poor T cell stimulatory capability and possess high phagocytic activity both in vitro and in vivo (19, 21).

Fig. 4. CX3CR1+ cells passage into the intestinal lumen occurred through paracellular spaces.

Still images from in vivo real time video (Supplemental video 1): images of orthogonal cross-sections through the 3D stacks in successive time-frames. Detailed views show the movement of a fluorescent CX3CR1+/gfp cell following challenge with Salmonella. In (A) the CX3CR1+/gfp cell (white box) is protruding from the epithelial surface; the outward movement being more pronounced in (B). In C the migrating cell keeps protruding into the lumen until it completed its migration and moved away (dotted line) from the entry site (small white box) (D, E). The migrating cells is immediately followed by another CX3CR1+/gfp cells protruding into the lumen from the same opening (D,E, small white box). Images on YZ plan (A-E) allow seeing that, once into the lumen the cell progresses in a non-linear (side-to-side) pattern on the epithelial surface. Scale bar = 10 μm. Migration pattern was further investigated by immunofluorescence microscopy (F) and TEM (G, H). In (F), CX3CR1+/gfp cells (asterisks) migrate into the intestinal lumen (L) across the basal membrane (arrow heads), identified by anti-entactin antibody (blue) and then the epithelium identified with phalloidin (red). In (G and H) a series of cells (mC1-3) moved into the lumen (L) via the paracellular space (arrow heads) between adjacent enterocytes (E) through the same paracellular channel. Also, in (G) one migrating cell (mC2) is in close contact with Salmonella (box) (detail in H).

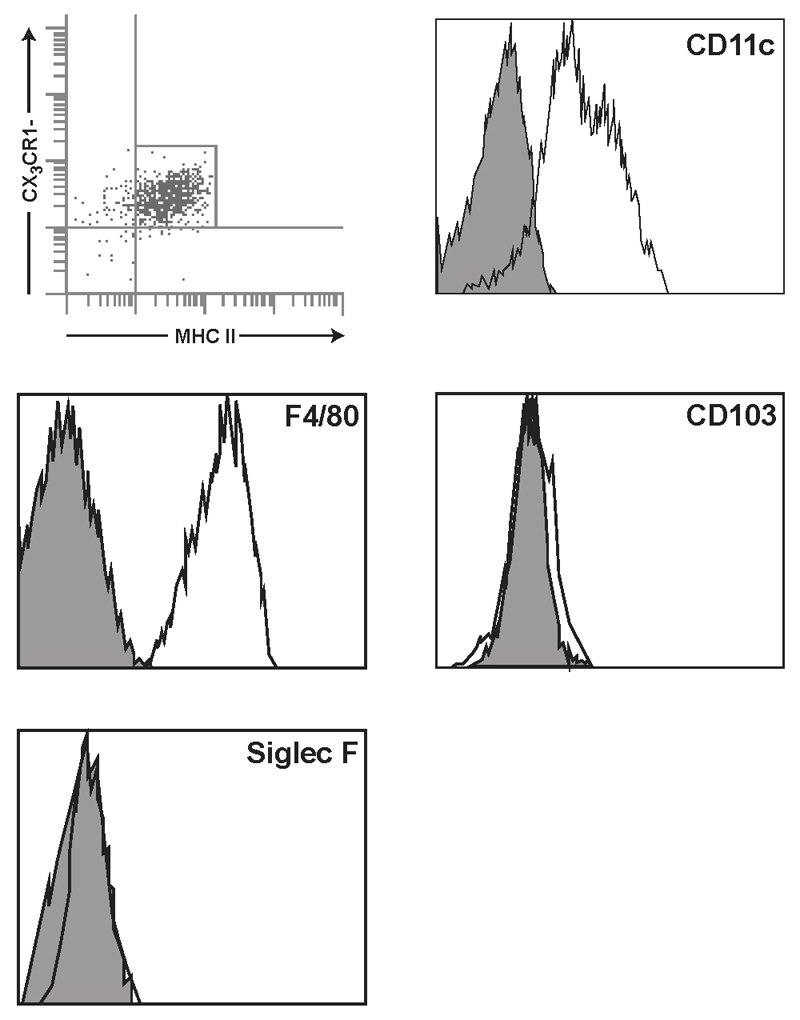

Fig. 5. Phenotypic analysis of intraluminal CX3CR1+ cell population.

Flow cytometry analysis of intraluminal cells in CX3CR1+/gfp (Balb/c background) 5 hours following intestinal challenge with 1x107 InvA- Salmonella. The vast majority of the cell population rapidly recruited into the intestinal lumen showed the phenotype of resident (stationary) macrophage with poor T cell stimulatory activity and high phagocytic activity. These cells were CD11C+F4/80+MHCII+ but did not express the canonical marker for gut-derived dendritic cell (DCs), CD103; also, these cells lacked the neutrophil marker SiglecF

Lack of CX3CR1-mediated sampling did not affect antibody responses to S. Typhimurium

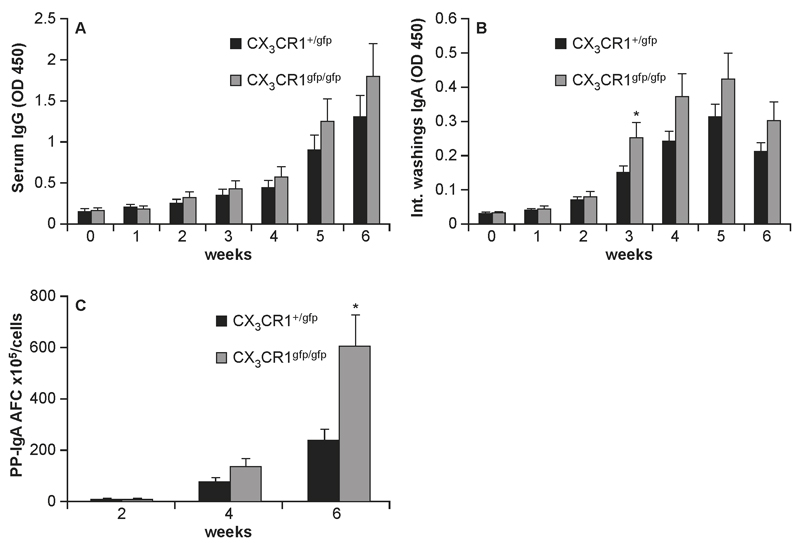

It has been suggested that antigen-sampling mediated by CX3CR1+ cells in the lamina propria, also called the indirect route (22) plays a significant role in the generation of mucosal and systemic immune responses. However, so far a direct evidence of this was still lacking. Thus, we assessed mucosal and systemic antibody responses to InvA-AroA- S. Typhimurium that specifically targets CX3CR1-mediated entry route (22) in CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice that lack a functional CX3CR1 receptor. We observed that the levels of serum IgG was consistently higher in CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice compared to CX3CR1+/gfp mice starting at week 2 post-infection (Fig. 6A) although it did not reach statistical significance. Instead, sIgA production in CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice, albeit significantly lower than the one induced by invasive/non-replicating InvA+AroA- S. Typhimurium (data not shown) was significantly higher compared to wt mice (Fig. 6B) starting from week 3 post-infection. The higher S. Typhimurium-specific IgA response in CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice was confirmed by assessing the numbers of antibody forming cells (AFC) in the PPs (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6. Humoral immunity to non-invasive Salmonella in CX3CR1-/- mice.

Mice (9-10 mice/group) received 3 consecutive doses of 1x107 of non-invasive/non-replicating InvA-AroA- Salmonella at 3 day interval. Levels of serum IgG (A) and intestinal IgA (B) Salmonella-specific antibodies were determined by ELISA. Both responses appeared to be higher in CX3CR1gfp/gfp compared to CX3CR1+/gfp mice although only intestinal levels of IgA were significantly different starting from week 3 after infection (*). Higher mucosal IgA immunity in CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice was further confirmed by monitoring numbers of AFC in PPs at weeks 2, 4 and 6 post-infection (C). Asterisk (*) indicates significant statistical difference.

The presence of CX3CR1+ cells in the intestinal lumen significantly reduced the number of S. Typhimurium penetrating the epithelial barrier

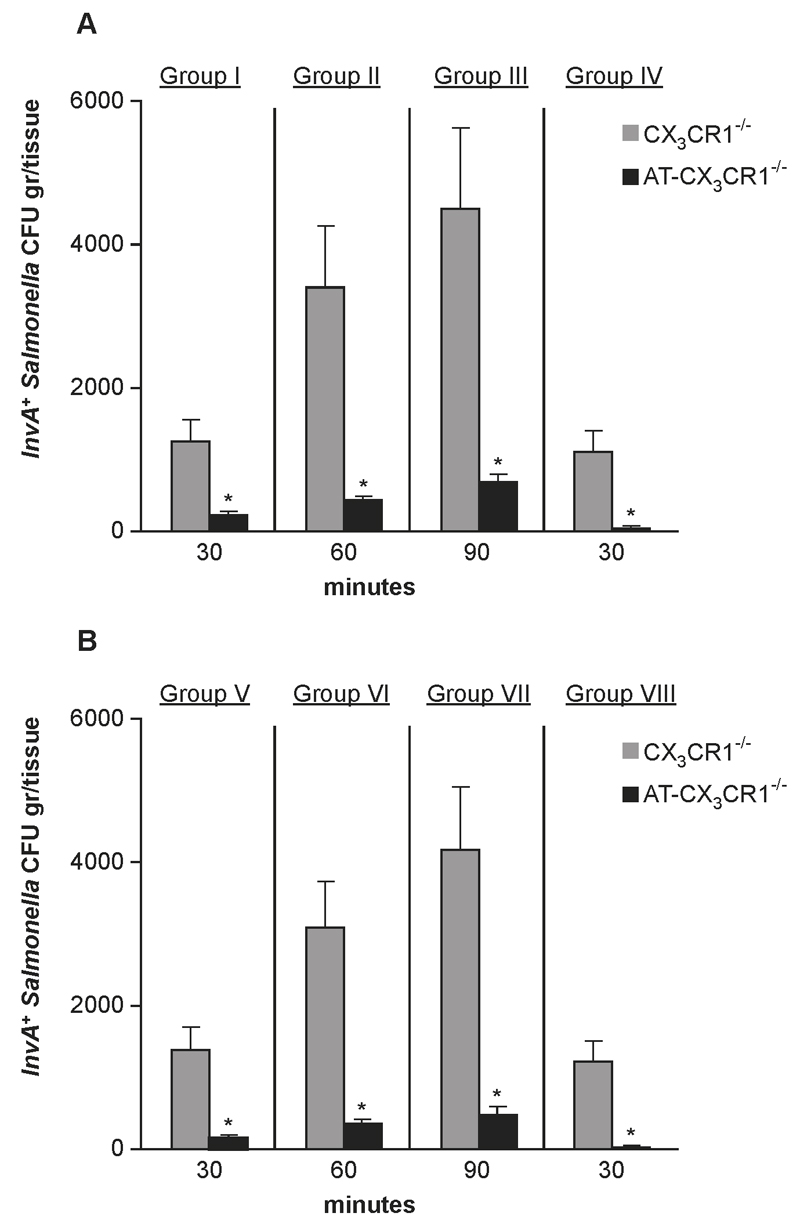

Finally, we tested the hypothesis that intraluminal CX3CR1+ cells contributed to immune-exclusion of S. Typhimurium. At various intervals, shortly following oral delivery of 1x107 InvA+AroA- S. Typhimurium, CX3CR1+ cells isolated from CX3CR1+/gfp donors were injected into the intestinal lumen of migration-deficient CX3CR1-/- mice (details of protocol in Supplemental Fig. 3). Four groups of mice were used and the number of adoptively transferred cells at any given time point was based on time course experiment carried out previously (Fig. 3C). The adoptive transfer of intraluminal CX3CR1+ cells in CX3CR1-/- mice significantly reduced the number of InvA+ S. Typhimurium traversing the epithelial barrier (Fig. 7A). In the presence of 0.5x103 CX3CR1+ cells the number of tissue CFU of InvA+ S. Typhimurium declined (from 1.2x103±3.3x102 to 2.1x102±1.4x102) at 30 minutes post-infection (group I). Similarly, significant reductions in bacterial load in the intestinal tissues were observed in group II and III. Finally, group IV was passively transferred, fifteen minutes after S. Typhimurium administration with a number of CX3CR1+ cells (1x104) that far exceeded the number of CX3CR1+ cells found in the small intestine at the beginning of the infection. In this case, the presence of intraluminal CX3CR1+ cells almost completely abolished Salmonella invasion of intestinal tissue (CFU tissue <40). Importantly, when CX3CR1gfp/gfp were used in experiments of adoptive transfer (Figure 7B) we observed that these cells afforded a similar level of protection against S. Typhimurium invasion compared to CX3CR1+/gfp cells. This demonstrated that transepithelial migration and no other intrinsic defects of CX3CR1-/- cells is the critical event in immune-exclusion against S. Typhimurium. Taken together these results demonstrated that CX3CR1+ cells that migrate rapidly into the lumen represented a rapidly deployed protective response that prevents harmful microbes such as S. Typhimurium from infecting the host.

Fig. 7. CX3CR1+ cell-mediated pathogen-exclusion.

CX3CR1-/- mice (6 mice/group) were infected with a single oral dose (1x107) of invasive/non-replicating InvA+Aro-Salmonella. Salmonellae infecting the intestinal tissue were determined in the absence (CX3CR1-/-, grey bars) or presence (AT-CX3CR1-/-, black bars) of CX3CR1+/gfp (A) or CX3CR1gfp/gfp (B) cells that were adoptively transferred (AT) directly into the intestinal lumen. A significant decline of S. Typhimurium CFU gr/tissue was observed in group I (A) 30 minutes after infection following adoptive transfer of 0.5x103 CX3CR1+/gfp cells. Significant reduction in the number of pathogens invading the host was also seen in group II and III that received increasing numbers of CX3CR1+ that were determined according to the time course study shown in Fig 3C. In group IV the introduction in the lumen of a larger, non-physiologically high number of intraluminal CX3CR1+ cells (1x104) of higher (20 fold increase compared to the number of cells usually found in the gut 15 minutes after infection) nearly completely abolished S. Typhimurium infection. A similar pattern was observed in parallel experiments when CX3CR1gfp/gfp cells were used for the adoptive transfer (Group V-VIII) (B) showing that the lack of transepithelial migration and no other intrinsic defects of CX3CR1-/- cells is critical for immune exclusion of S. Typhimurium. Asterisk (*) indicates significant statistical difference.

Discussion

The presence of epithelial tight junctions, a thick layer of mucus and secretion of sIgA ensures that harmful microorganisms do not breach the intestinal epithelium. Here we demonstrated that when this barrier is breached by invading pathogenic bacteria the host rapidly responds by sending into the intestinal lumen pathogen (S. Typhimurium)-capturing CX3CR1+ cells to limit the number of bacteria penetrating the epithelial barrier. The rapid migration is triggered by the initial interaction of pathogens with IEC since this migration is absent in mice lacking the adaptor molecules MyD88 solely within the epithelium. Interaction of S. Typhimurium and the IEC-associated TLR may lead to two different events. CX3CR1+ cells can directly sample bacteria and shuttle them across the epithelium (6); alternatively these cells could also move through the epithelium and migrate into the lumen where they capture S. Typhimurium (5). However, while it was suggested that CX3CR1-sampling was relevant to mounting antigen-specific responses the role and biological relevance of the rapid migration of S. Typhimurium-capturing CX3CR1+ cells in the lumen remained to be determined. CX3CR1-mediated sampling and migration showed significant differences. The most notable being that, while CX3CR1-migration in response to S. Typhimurium takes place irrespective of the mouse strain, such as C57BL/6 and Balb/c (5) the ability to sample luminal bacteria via the indirect route may or may not be present according to the genetic make-up of the host (7, 8, 10), an observation that led to the conclusion that CX3CR1-mediated sampling is not a universal phenomenon (23). We exploited this feature to investigate the biological relevance of these two CX3CR1-mediated events during the initial stage of S. Typhimurium infection. We observed that, in spite of lacking the ability to sample bacteria via the indirect route, Balb/c mice showed very similar intestinal uptake of non-invasive S. Typhimurium, that specifically targets the indirect route compared to sampling-competent wt C567BL/6. This observation is of particular relevance when examined in the context of S. Typhimurium uptake in CX3CR1-deficient mice that lacked both CX3CR1-sampling (6) and -intraluminal migration (9). We observed that CX3CR1-deficient mice showed a significantly higher bacterial load both at mucosal level and systemically compared to both C57BL/6 and Balb/c. Increased pathogen uptake in CX3CR1-deficient mice did not depend on intrinsic alteration of the integrity of the epithelial barrier in both CX3CR1-/- and CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice since permeability to either soluble or particulate tracers was similar to what observed in their wt counterparts. Overall these results would suggest that sampling via the indirect route does not play a significant role in S. Typhimurium up-take through the intestinal epithelium, at least during the early stage of infection. Instead, they point to the lack of rapid intraluminal migration of CX3CR1+ cells as the critical factor favouring bacterial translocation. This hypothesis is further strengthened by the observation that intraluminal migration of CX3CR1+ cells in CX3CR1+/gfp mice was associated with increased faecal bacterial counts compared to migration-deficient CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice. Importantly, others have shown that CX3CR1-/- displayed increased translocation of commensal bacteria to MLN (24), thus suggesting that intraluminal migration of CX3CR1+ cell might also play a role in controlling the access of commensal microbes to the intestinal tissue. Furthermore, CX3CR1-deficient mice are more susceptible to S. Typhimurium infection, as seen by us and others (6); however, the reason for this remained to be determined. One possibility was that the lack of CX3CR1-mediated sampling led to an impaired immunity to S. Typhimurium. We observed that CX3CR1-deficient mice developed a systemic IgG response comparable to wt control and surprisingly, a significantly higher intestinal antibody response (IgA) to a non-invasive S. Typhimurium that targets the indirect route and is characterized by poor mucosal antigenic properties (22). It is likely that the latter observation could be attributed to the higher number of S. Typhimurium reaching the PPs, the inductive sites of IgA-mediated immunity, in CX3CR1-deficient mice. Taken together these results strongly suggested that increased susceptibility to S. Typhimurium infection in CX3CR1-deficient mice was due, at least partly to the lack of protection afforded by CX3CR1-mediated pathogen exclusion in the early stage of infection. As a parallel observation, these data also confirmed previous reports suggesting that S. Typhimurium type III secretion system (InvA) facilitates up-take by FAE-microfold (M) cells but its absence does not totally compromise the ability of S. Typhimurium to target this entry route (25, 26). Intraluminal migration of CX3CR1+ cells is unidirectional and once into the lumen they do not traverse back the intestinal epithelium. Determining the fate of intraluminal S. Typhimurium-capturing CX3CR1+ cells was prompted by the important finding that in mice T. gondii-infected neutrophils that had migrated into the intestinal lumen during the infection can move back into the intestinal tissue at a later stage (one week post-infection) (27). The observation that CX3CR1+/gfp in contrast to infected neutrophils undertake a one way journey suggested that, neutrophils may be intrinsically different from CX3CR1+ cells in their ability to traverse back the epithelium. Alternatively, it is possible that in contrast to S. Typhimurium, T. gondii might trigger the secretion/expression of cytokine/surface molecules in infected cells that favour this event. Finally, we demonstrated that the migration of CX3CR1+ cells into the lumen very early during S. Typhimurium infection contributed substantially to pathogen-exclusion. Direct introduction of these cells into the lumen of migration-deficient CX3CR1-/- mice shortly after oral delivery of invasive S. Typhimurium significantly reduced the number of pathogens traversing the epithelial barrier. Furthermore, although at this time we cannot rule out the possibility that other cell types may participate to this protective response at a later stage in infection, the previous observation that CX3CR1+ cells was the only intraluminal cell population harbouring intracellular S. Typhimurium (5) implied that these cells are the main player in the exclusion of S. Typhimurium in the very early stage of infection. Previous study showed that intraluminal CX3CR1+ cells internalized S. Typhimurium (5); thus, intracellular killing is the most likely mechanism underlying S. Typhimurium-exclusion in the gut although at present other mechanisms such as production of anti-microbial products cannot be rule out. Here, we would like to propose that the CX3CR1-mediated pathogen-exclusion is part of a defensive strategy that includes multiple effector mechanisms acting synergistically. First, the mucous and IgA that are constantly produced in large amount in the gut provide a preventive barrier that in a steady state situation controls and limits the access of microbes to the intestinal epithelium. When this defensive barrier is breached, IEC-derived signals readily trigger the intraluminal migration of CX3CR1+ cells that are present in large number in the subepithelial area where they form an intricate cell network (19, 21). This strategy, implemented in the initial stage of the infection blocks further pathogen penetration and, in so doing may prevent the onset of infection by limiting the number of the offending pathogens that can trespass the epithelial barrier. At later stage this strategy is followed, if necessary by an additional defensive mechanism represented by the NAIP/NLRC4 inflammasone-mediated expulsion of infected enterocytes (4) to restrict/control S. Typhimurium replication/colonization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank P. Mastroeni, D. Pickard for S. Typhimurium strains; O. Pabst and A. Mowat for CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice and K. Hughes for the MyD88∆IEC mice. We also thank A. Walker and P. Pople for computer artwork and R. Gichev for his technical help.

4 This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), UK, Institute Strategic Programme Grant (BB/J004529/1: The Gut Health and Food Safety-ISP) (to CN) and intramural funds from University of Siena, Italy (to EB).

Abbreviations

- IEC

intestinal epithelial cell

- PP

Peyers patch

- MLN

mesenteric lymph node

- lp

lamina propria

References

- 1.Turner JR. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:799–809. doi: 10.1038/nri2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mantis NJ, Rol N, Corthésy B. Secretory IgA's complex roles in immunity and mucosal homeostasis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:603–611. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansson ME, Ambort D, Pelaseyed T, Schütte A, Gustafsson, Edmund EA, Subramani DB, Holmén-Larsson JM, Thomsson KA, Bergström JH, van der Post S, et al. Composition andfunctional role of the mucus layers in the intestine. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:3635–41. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0822-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sellin ME, Müller AA, Felmy B, Dolowschiak T, Diard M, Tardivel A, Maslowski KM, Hardt WD. Epithelium-intrinsic NAIP/NLRC4 inflammasome drives infected enterocyte expulsion to restrict Salmonella replication in the intestinal mucosa. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arques JL, Hautefort I, Ivory K, Bertelli E, Regoli M, Clare S, Hinton JC, Nicoletti C. Salmonella induces flagellin- and MyD88-dependent migration of bacteria-capturing dendritic cells into the gut lumen. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:579–587. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niess JH, Brand S, Gu X, Landsman L, Jung S, Jung S, McCormick BA, Vyas JM, Boes M, Ploegh HL, Fox JG, et al. CX3CR1-mediated dendritic cell access to the intestinal lumen and bacterial clearance. Science. 2005;307:254–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1102901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rescigno M, Urbano M, Valzasina B, Francolini M, Rotta G, Bonasio R, Granucci F, Kraehenbuhl JP, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Dendritic cells express tight junction proteins and penetrate gut epithelial monolayers to sample bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:361–367. doi: 10.1038/86373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chieppa M, Rescigno M, Huang AY, Germain RN. Dynamic imaging of dendritic cell extension into the small bowel lumen in response to epithelial cell TLR engagement. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2841–2852. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicoletti C, Arques JL, Bertelli E. CX3CR1 is critical for Salmonella-induced migration of dendritic cells into the intestinal lumen. Gut Microbes. 2010;1:131–134. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.3.11711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallon-Eberhard A, Landsman L, Yogev N, Verrier B, Jung S. Transepithelial pathogen uptake into the small intestinal lamina propria. J Immunol. 2006;176:2465–2469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung S, Aliberti J, Graemmel P, Sunshine MJ, Kreutzberg GW, Sher A, Littman DR. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4106–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4106-4114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skoczek DA, Walczysko P, Horn N, Parris A, Clare S, Williams MR, Sobolewski A. Luminal microbes promote monocyte-stem cell interactions across a healthy colonic epithelium. J Immunol. 2014;193:439–451. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowley G, Skovierova H, Stevenson A, Rezuchova B, Homerova D, Lewis C, Sherry A, Kormanec J, Roberts M. The periplasmic chaperone Skp is required for successful S. Typhimurium infection in a murine typhoid model. Microbiology. 2011;157:848–858. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.046011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Man AL, Bertelli E, Rentini S, Regoli M, Briars G, Marini M, Watson AW, Nicoletti C. Age-associated modifications of intestinal permeability and innate immunity in human small intestine. Clin Sci (London) 2015;129:515–527. doi: 10.1042/CS20150046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Bella A, Regoli M, Nicoletti C, Ermini L, Fonzi L, Bertelli E. An appraisal of intermediate filament expression in adult and developing pancreas: vimentin is expressed in alpha cells of rat and mouse embryos. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57:577–586. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.952861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Regoli M, Borghesi C, Bertelli E, Nicoletti C. A morphological study of the lymphocyte traffic in Peyer's patches after an in vivo antigenic stimulation. Anat Rec. 1994;239:47–54. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092390106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wigley P, Hulme S, Powers C, Beal R, Smith AL. Temporal dynamics of the cellular, humoral and cytokine responses in chickens during primary and secondary infection with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Avian Pathol. 2004;33:25–33. doi: 10.1080/03079450310001636282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicoletti C, Borghesi C. Detection of autologous anti-idiotypic antibody-forming cells by a modified enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) Res Immunol. 1992;14:919–925. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(92)80115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz O, Jaensson E, Persson EK, Liu X, Worbs T, Agace WW, Pabst O. Intestinal CD103+, but not CX3CR1+, antigen sampling cells migrate in lymph and serve classical dendritic cell functions. J Exp Med. 2009;206:3101–3114. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Man AL, Lodi F, Bertelli E, Regoli M, Pin C, Mulholland F, Satoskar AR, Taussig MJ, Nicoletti C. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor plays a role in the regulation of microfold (M) cell-mediated transport in the gut. J Immunol. 2008;181:5673–5680. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bain CC, Scott CL, Uronen-Hansson H, Gudjonsson S, Jansson O, Grip O, Guilliams M, Malissen B, Agace WW, Mowat AM. Resident and pro-inflammatory macrophages in the colon represent alternative context-dependent fates of the same Ly6Chi monocyte precursors. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:498–510. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinoli C, Chiavelli A, Rescigno M. Entry route of Salmonella typhimurium directs the type of induced immune response. Immunity. 2007;27:975–984. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwasaki A. Mucosal dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:381–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medina-Contreras O, Geem D, Laur O, Williams IR, Lira SA, Nusrat A, Parkos CA, Denning TL. CX3CR1 regulates intestinal macrophage homeostasis, bacterial translocation, and colitogenic Th17 responses in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4787–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI59150. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez-Argudo I, Jepson MA. Salmonella translocates across an in vitro M cell model independently of SPI-1 and SPI-2. Microbiology. 2008;154:3887–94. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/021162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jepson MA, Clark MA. The role of M cells in Salmonella infection. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:1183–1190. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coombes JL, Charsar BA, Han SJ, Halkias J, Chan SW, Koshy AA, Striepen B, Robey EA. Motile invaded neutrophils in the small intestine of Toxoplasma gondii-infected mice reveal a potential mechanism for parasite spread. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E1913–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220272110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.