LETTER

We read with interest the continental drift hypothesis by Casadevall et al. (1) as a possible speciation driver within the Cryptococcus species complexes, adding greatly to the ongoing discussion of speciation between these complexes (2, 3). We further propose that this mechanism may also have had speciation effects within these complexes, most notably within Cryptococcus gattii, where at least four major molecular types/species are recognized (VGI, VGII, VGIII, and VGIV). It is likely that with hundreds of thousands of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mutations separating the major C. gattii molecular types (4), their temporal separation is in the tens of millions of years (5, 6). C. gattii was originally considered a tropical pathogen, being endemic to Australia, Asia, Africa, and South America, with random cases appearing in North America and Europe (7, 8); it is either nonendemic or newly endemic to these latter continents due to global movement of C. gattii microhabitats, such as eucalypts (e.g., Eucalyptus camaldulensis) and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) (9, 10).

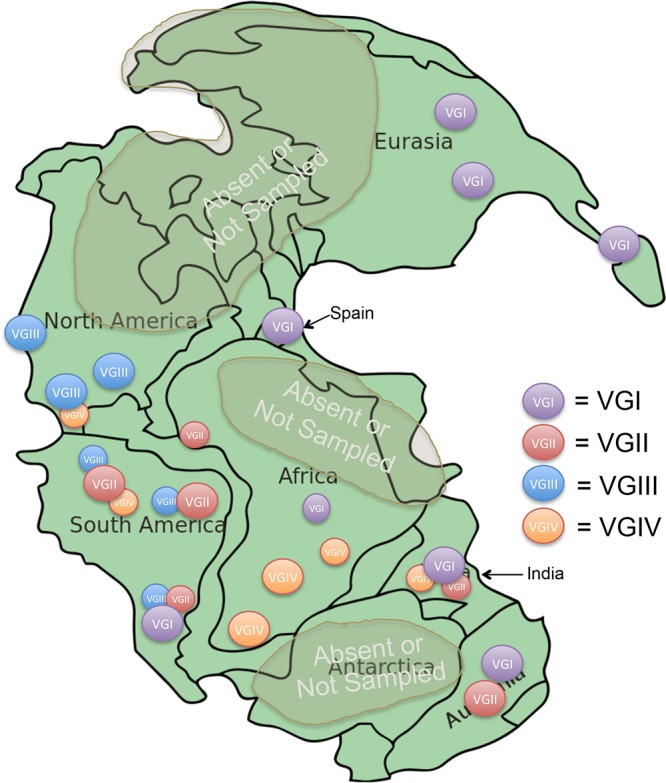

Based on global genotype data, we noted that the molecular types appear to have hemispheric and continental associations (Fig. 1). Asian C. gattii isolates are predominantly VGI, with a low-level VGII presence in most Asian countries (11). VGIV has only been reported in India (12), and VGIII appears to be absent in Asia, except in Thailand (13). Conversely, VGIV is the dominant C. gattii molecular type in Africa (11). Only VGI and VGII have been identified in Australia, one of the first places where C. gattii was found in the environment and therefore previously considered to be a possible birthplace of C. gattii (14, 15). There are limited to no reported findings of VGIII in Australia or Africa. In Europe, except for Spain, where a significant number of VGI strains have been identified, isolates are largely clinical or associated with nonnative trees (9, 11). Most United States cases are traveler associated or are due to recent translocations of the fungus from regions of endemicity. Beyond the emergence of VGII out of Brazil into the Pacific Northwest (4, 16, 17), VGIII emergent events have occurred in California (18) and the southeastern United States (19), and VGIII also dominates among isolates from Mexico (20, 21). South America has a high degree of disease, primarily in three countries: Brazil and Columbia have predominantly VGII (22), with lower levels of VGI and VGIII (17) and, rarely, VGIV, whereas isolates in Argentina are primarily VGI (11). Numerous isolations from native Amazonian rain forest trees far removed from human interactions suggest an ancestral location for C. gattii (23–25).

FIG 1 .

A Pangea representation of present day geographically dominant C. gattii populations. Note that nonendemic isolations and more recent emerged populations are not displayed. (Image adapted from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pangaea_continents.png.)

Of interest are possible remnant populations from prior contiguous Pangea regions. For example, India was a contiguous landmass with southern Africa (R. W. Schlische; http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~schlisch/103web/Pangeabreakup/breakupframe.html). It is possible that a common ancestor to VGIV was endemic to such a region prior to the break off of the Indian Subcontinent. Other interesting phylogeographic features include African VGII being found only in Senegal, a previous land partner with Brazil (17), and the presence of apparently endemic European C. gattii primarily only on the Iberian Peninsula, Europe’s Pangea connection to Africa (R. A. Krulwich; http://www.npr.org/blogs/krulwich/2013/09/12/221874851/a-most-delightful-map.

This is not to suggest that the above endemic foci are all due to separation of contiguous endemic populations during the breakup of Pangea, nor does this represent an exhaustive listing of all isolations of C. gattii around the world. It is however an additional viewpoint in favor of the continental drift dispersal hypothesis.

Footnotes

For the author reply, see https://doi.org/10.1128/mSphere.00242-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Casadevall A, Freij JB, Hann-Soden C, Taylor J. 2017. Continental drift and speciation of the Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii species complexes. mSphere 2:e00103-17. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00103-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagen F, Khayhan K, Theelen B, Kolecka A, Polacheck I, Sionov E, Falk R, Parnmen S, Lumbsch HT, Boekhout T. 2015. Recognition of seven species in the Cryptococcus gattii/Cryptococcus neoformans species complex. Fungal Genet Biol 78:16–48. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennett JE, Wickes BL, Meyer W, Cuomo CA, Wollenburg KR, Bicanic TA, Castaneda E, Chang YC, Chen J, Cogliati M, Dromer F, Ellis D, Filler SG, Fisher MC, Harrison TS, Holland SM, Kohno S, Kronstad JW, Lazera M, Levitz SM, Lionakis MS, May RC, Ngamskulrongroj P, Pappas PG, Perfect JR, Rickerts V, Sorrell TC, Walsh TJ, Williamson PR, Xu J, Zelazny AM, Casadevall A. 2017. The case for adopting the “species complex” nomenclature for the etiologic agents of cryptococcosis. mSphere 2:e00357-16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00357-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engelthaler DM, Hicks ND, Gillece JD, Roe CC, Schupp JM, Driebe EM, Gilgado F, Carriconde F, Trilles L, Firacative C, Ngamskulrungroj P, Castañeda E, Lazera MS, Melhem MS, Pérez-Bercoff A, Huttley G, Sorrell TC, Voelz K, May RC, Fisher MC, Thompson GR, Lockhart SR, Keim P, Meyer W. 2014. Cryptococcus gattii in North American Pacific Northwest: whole population genome analysis provides insights into species evolution and dispersal. mBio 5:e01464-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01464-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ngamskulrungroj P, Gilgado F, Faganello J, Litvintseva AP, Leal AL, Tsui KM, Mitchell TG, Vainstein MH, Meyer W. 2009. Genetic diversity of the Cryptococcus species complex suggests that Cryptococcus gattii deserves to have varieties. PLoS One 4:e5862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharpton TJ, Neafsey DE, Galagan JE, Taylor JW. 2008. Mechanisms of intron gain and loss in Cryptococcus. Genome Biol 9:R24. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis DH, Pfeiffer TJ. 1990. Natural habitat of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii. J Clin Microbiol 28:1642–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennett JE. 1984. High prevalence of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii in tropical and subtropical regions. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A 257:213–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chowdhary A, Rhandhawa HS, Prakash A, Meis JF. 2012. Environmental prevalence of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in India: an update. Crit Rev Microbiol 38:1–16. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2011.606426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montagna MT, Viviani MA, Pulito A, Aralla C, Tortorano AM, Fiore L, Barbuti S. 1997. Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii in Italy. Note II. Environmental investigation related to an autochthonous clinical case in Apulia. J Mycol Med 7:93–96. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cogliati M. 2013. Global molecular epidemiology of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii: an atlas of the molecular types. Scientifica 2013:675213. doi: 10.1155/2013/675213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grover N, Nawange SR, Naidu J, Singh SM, Sharma A. 2007. Ecological niche of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii and Cryptococcus gattii in decaying wood of trunk hollows of living trees in Jabalpur City of Central India. Mycopathologia 164:159–170. doi: 10.1007/s11046-007-9039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaocharoen S, Ngamskulrungroj P, Firacative C, Trilles L, Piyabongkarn D, Banlunara W, Poonwan N, Chaiprasert A, Meyer W, Chindamporn A. 2013. Molecular epidemiology reveals genetic diversity amongst isolates of the Cryptococcus neoformans/C. gattii species complex in Thailand. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7:e2297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrnes EJ III, Li W, Lewit Y, Ma H, Voelz K, Ren P, Carter DA, Chaturvedi V, Bildfell RJ, May RC, Heitman J. 2010. Emergence and pathogenicity of highly virulent Cryptococcus gattii genotypes in the northwest United States. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000850. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixit A, Carroll SF, Qureshi ST. 2009. Cryptococcus gattii: an emerging cause of fungal disease in North America. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis 2009:840452. doi: 10.1155/2009/840452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kidd SE, Hagen F, Tscharke RL, Huynh M, Bartlett KH, Fyfe M, MacDougall L, Boekhout T, Kwon-Chung KJ, Meyer W. 2004. A rare genotype of Cryptococcus gattii caused the cryptococcosis outbreak on Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:17258–17263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402981101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagen F, Ceresini PC, Polacheck I, Ma H, van Nieuwerburgh F, Gabaldón T, Kagan S, Pursall ER, Hoogveld HL, van Iersel LJ, Klau GW, Kelk SM, Stougie L, Bartlett KH, Voelz K, Pryszcz LP, Castañeda E, Lazera M, Meyer W, Deforce D, Meis JF, May RC, Klaassen CH, Boekhout T. 2013. Ancient dispersal of the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus gattii from the Amazon rainforest. PLoS One 8:e71148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Springer DJ, Billmyre RB, Filler EE, Voelz K, Pursall R, Mieczkowski PA, Larsen RA, Dietrich FS, May RC, Filler SG, Heitman J. 2014. Cryptococcus gattii VGIII isolates causing infections in HIV/AIDS patients in Southern California: identification of the local environmental source as arboreal. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004285. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lockhart SR, Roe CC, Engelthaler DM. 2016. Whole-genome analysis of Cryptococcus gattii, southeastern United States. Emerg Infect Dis 22:1098–1101. doi: 10.3201/eid2206.151455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olivares LR, Martínez KM, Cruz RM, Rivera MA, Meyer W, Espinosa RA, Martínez RL, Santos GM. 2009. Genotyping of Mexican Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii isolates by PCR-fingerprinting. Med Mycol 47:713–721. doi: 10.3109/13693780802559031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Springer DJ, Phadke S, Billmyre B, Heitman J. 2012. Cryptococcus gattii, no longer an accidental pathogen? Curr Fungal Infect Rep 6:245–256. doi: 10.1007/s12281-012-0111-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Escandón P, Sánchez A, Martínez M, Meyer W, Castañeda E. 2006. Molecular epidemiology of clinical and environmental isolates of the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex reveals a high genetic diversity and the presence of the molecular type VGII mating type a in Colombia. FEMS Yeast Res 6:625–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Firacative C, Torres G, Rodríguez MC, Escandón P. 2011. First environmental isolation of Cryptococcus gattii serotype B, from Cúcuta, Colombia. Biomedica 31:118–123. doi: 10.1590/S0120-41572011000100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fortes ST, Lazéra MS, Nishikawa MM, Macedo RC, Wanke B. 2001. First isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from a native jungle tree in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest. Mycoses 44:137–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2001.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazéra MS, Cavalcanti MA, Trilles L, Nishikawa MM, Wanke B. 1998. Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii—evidence for a natural habitat related to decaying wood in a pottery tree hollow. Med Mycol 36:119–122. doi: 10.1080/02681219880000191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]