Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: TRP, transient receptor potential; InsP3, inositol (1,4,5) trisphosphate; IP3R, InsP3 receptor; PLC, phospholipase C; DPP, deep pseudopupil; R, rhodopsin; M, metarhodopsin

Keywords: Phototransduction, TRP channels, Na/Ca exchanger, InsP3, Phospholipase C, Calcium imaging, Genetically encoded calcium indicators

Highlights

-

•

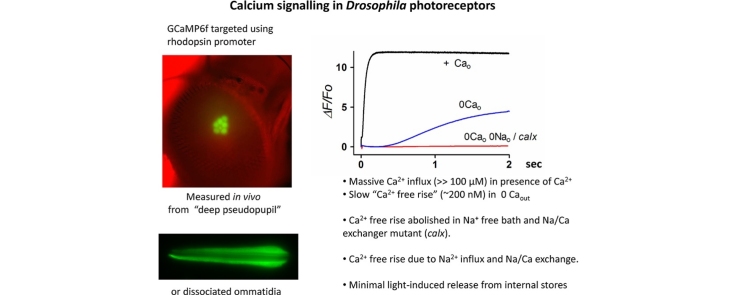

Fruitflies generated expressing GCaMP6f in photoreceptors using the opsin promoter.

-

•

Quantitative in vivo Ca2+ imaging in completely intact flies as well as dissociated cells.

-

•

Ca2+ rise in Ca2+ free bath abolished in Na+/Ca2+ exchanger mutants.

-

•

Ca2+ free rise due to re-equilibration of Na+/Ca2+ exchange following Na+ influx.

-

•

No significant light-induced release of Ca2+ from internal stores.

Abstract

Drosophila phototransduction is mediated by phospholipase C leading to activation of cation channels (TRP and TRPL) in the 30000 microvilli forming the light-absorbing rhabdomere. The channels mediate massive Ca2+ influx in response to light, but whether Ca2+ is released from internal stores remains controversial. We generated flies expressing GCaMP6f in their photoreceptors and measured Ca2+ signals from dissociated cells, as well as in vivo by imaging rhabdomeres in intact flies. In response to brief flashes, GCaMP6f signals had latencies of 10–25 ms, reached 50% Fmax with ∼1200 effectively absorbed photons and saturated (ΔF/F0 ∼ 10–20) with 10000–30000 photons. In Ca2+ free bath, smaller (ΔF/F0 ∼4), long latency (∼200 ms) light-induced Ca2+ rises were still detectable. These were unaffected in InsP3 receptor mutants, but virtually eliminated when Na+ was also omitted from the bath, or in trpl;trp mutants lacking light-sensitive channels. Ca2+ free rises were also eliminated in Na+/Ca2+ exchanger mutants, but greatly accelerated in flies over-expressing the exchanger. These results show that Ca2+ free rises are strictly dependent on Na+ influx and activity of the exchanger, suggesting they reflect re-equilibration of Na+/Ca2+ exchange across plasma or intracellular membranes following massive Na+ influx. Any tiny Ca2+ free rise remaining without exchanger activity was equivalent to <10 nM (ΔF/F0 ∼0.1), and unlikely to play any role in phototransduction.

1. Introduction

Phototransduction in Drosophila is mediated by a G-protein coupled phospholipase C (PLC) signalling cascade [1], [2], [3]. All key elements of the transduction cascade from the visual pigment rhodopsin (Rh1) to the “light-sensitive” channels are localised within ∼30000 microvilli forming a light-guiding “rhabdomere”. Absorption of a single photon by one rhodopsin molecule results in a discrete electrical event (quantum bump), believed to reflect activation of PLC and ion channels within just one microvillus. The macroscopic current response to brighter light is the summation of multiple quantum bumps generated stochastically by absorption of photons across the microvillar population [4], [5]. There are two distinct light-sensitive channels in Drosophila: TRP (transient receptor potential), which is the prototypical and defining member of the TRP ion channel superfamily [6], [7], and a homologue, TRP-like, or TRPL [8], [9], both belonging to the TRPC subfamily. Although, both are cation channels permeable to Ca2+, TRP, which dominates the light-induced current (LIC) is particularly selective for Ca2+ (PCa:PNa ∼50:1), whilst TRPL has a more modest PCa:PNa of ∼4:1 [10], [11]. As well as mediating a major fraction of the LIC [12], Ca2+ influx via these channels plays critical positive and negative feedback roles at multiple downstream targets and is essential for rapid kinetics and light adaptation [13], [14].

Measurements using fluorescent Ca2+ indicators in dissociated Drosophila photoreceptors reveal that the Ca2+ signal in response to blue excitation light is dominated by massive Ca2+ influx via the light-sensitive channels [15], [16], [17]. Studies in larger flies using low affinity indicators show that Ca2+ levels in the microvilli reach near mM levels in vivo [18], and modelling suggests similar levels are reached in Drosophila [12], [19]. In Ca2+ free solutions there is a much smaller (submicromolar) and slower rise in fluorescence, the origin and role of which is controversial [17], [20], [21], [22]. Because InsP3 is presumably generated in large amounts in response to the blue excitation, InsP3-induced Ca2+ release from internal stores would seem the obvious explanation. However, using the high affinity ratiometric indicator INDO-1, this Ca2+ free signal was reported to be unaffected in null mutants of the only InsP3 receptor (IP3R) gene in the Drosophila genome [21]. Challenging this, Kohn et al. [22] reported that the Ca2+ free rise measured using the genetically encoded indicator GCaMP6f was substantially reduced following RNAi knockdown of the IP3R and proposed that InsP3-induced Ca2+ release played a critical role in phototransduction.

In the present study, we generated flies expressing GCaMP6f [23] in R1-6 photoreceptors under direct control of the Rh1 (ninaE) promoter. We performed measurements in dissociated ommatidia allowing control of extracellular solutions, and also in vivo from completely intact flies by imaging the rhabdomeres in the “deep pseudopupil” (DPP) [24], [25], [26]. By using 2-pulse protocols we provide data on the time course and intensity dependence of Ca2+ signals in vivo in response to physiologically relevant stimuli. We paid particular attention to the origin of the Ca2+ rise under Ca2+ free conditions, and found that it was unaffected in IP3R mutants, but strictly dependent upon both Na+ influx and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger activity. We conclude that any light-induced release from internal stores is minimal (<10 nM), slow, and unlikely to play any direct role in phototransduction.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Flies

Flies (Drosophila melanogaster) were reared on standard medium [recipe in [27]] at 25 °C in a dark incubator. For dissociated ommatidia, newly eclosed (<2 h) adults were used; for in vivo deep pseudopupil measurements flies were 1–7 days old. GCaMP6f (cDNA obtained from Addgene) was cloned into the pCaSpeR4 vector which contains a mini-w+ gene as transfection marker and the ninaE (Rh1) promoter that drives expression exclusively in photoreceptors R1-6. The final construct (ninaE-GCaMP6f) was injected into w1118 embryos and transformants recovered on 2nd and 3rd chromosomes. The ninaE-GCaMP6f transgene was crossed into various genetic backgrounds including:

trp343 – null mutant lacking TRP channels [28],

trpl302 – null mutant lacking TRPL channels [9]

and trpl302;trp343 – double null mutant lacking all light-sensitive channels.

norpAP24 – null mutant of PLC [29].

calx1 – severe hypomorphic mutant of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (calx) with no detectable exchanger activity in the photoreceptors [30].

ninaE-calx/CyO – flies over-expressing a wild-type calx transgene under control of the Rh1-promoter [30].

(l(3)itpr90B.0 – larval lethal null mutant of InsP3 receptor: referred to as itpr [31].

To generate ninaE-GCaMP6f in whole eye IP3R null (itpr) mosaics:

ninaE-GCaMP6f/Cy;FRT82B, (l(3)itpr90B.0/TM6: were crossed to

yw;P{w+, ey-Gal4,UAS-FLP}/CyO;P{ry+,FRT82B}P{w+ GMR-hid},3CLR/TM6 – Bloomington stock 5253. Non-Cy and non-TM6 F1 then have itpr homozygote null mosaic eyes and ninaE-GCaMP6f [21], [32].

2.2. Electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings of photoreceptors from dissociated ommatidia from newly eclosed adult flies of either sex were performed as previously described [e.g. 33] on an inverted Nikon microscope (Nikon UK). Standard bath contained (in mM): 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 10 N-Tris-(hydroxymethyl)-methyl-2-amino-ethanesulphonic acid (TES), 4 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2, 25 proline and 5 alanine, pH 7.15. For Ca2+ free bath CaCl2 was omitted and 1 mM Na2EGTA added. The intracellular pipette solution was (in mM): 140 K gluconate, 10 TES, 4 Mg-ATP, 2 MgCl2, 1 NAD and 0.4 Na-GTP, pH 7.15. Chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Gillingham, UK). Recordings were made at room temperature (21 ± 1° C) at −70 mV (including correction for −10 mV junction potential) using electrodes of resistance 10–15 MΩ. Data were collected and analysed using an Axopatch 200 amplifier and pCLAMP v.9 or 10 software (Molecular Devices, Union City CA). Quantum bumps were analysed using Minianalysis software (Synaptosoft.com). Photoreceptors were stimulated via a green (522 nm) ultrabright light-emitting-diode (LED) controlled by a custom made LED driver; intensities were calibrated in terms of effectively absorbed photons by counting quantum bumps at low intensities.

2.3. GCaMP6f measurements

Fluorescence measurements were made as previously described [25], [34] on an inverted Nikon microscope (non-confocal) from dissociated ommatidia or in vivo by imaging the DPP in intact flies immobilised with low melting point wax in truncated plastic pipette tips. Excitation light (470 nm) was delivered from a blue power LED (Cairn Research UK) and fluorescence observed using 515 nm dichroic and OG515 long-pass filters. Fluorescent images were sampled and analysed at up to 500 Hz using an Orca 4 camera and HCImagelive software (Hamamtsu); but for most experiments fluorescence of whole ommatidia (via 40 x oil objective), or DPP (20 x air objective) was directly measured via a photomultiplier tube (Cairn Research UK), sampled at up to 2 kHz and analysed with pCLAMP software. Background fluorescence was subtracted using estimates from identical measurements from flies lacking fluorescent constructs, but with similar eye colour (most autofluorescence derives from screening pigment granules). Following each measurement the ommatidium/fly was exposed to intense, photo-equilibrating red (4 s, 640 nm ultra-bright LED) illumination to reconvert metarhodopsin (M) to rhodopsin (R), and allowed to dark adapt for at least one minute before the next measurement.

For Ca2+ free measurements, dissociated ommatidia (plated in standard bath) were briefly perfused with a Ca2+ free solution (0 Ca2+, 1 mM Na2EGTA see 2.2) or a Na+ and Ca2+ free solution in which NaCl was substituted for equimolar LiCl, KCl, CsCl or NMDGCl (1 mM K2EGTA and 4 mM MgCl2 also present). Ommatidia were individually perfused by a nearby (∼20 μm) puffer pipette and measurements made within ∼20–50 s of perfusion onset. Following M to R photoreconversion the cells were returned to normal (1.5 mM Ca2+) bath and dark-adapted for at least three minutes before the next measurement.

For 2-pulse experiments, green light was supplied by a green (λmax 522 nm) LED (for dissociated ommatidia) or for the DPP by a “warm-white” power LED (Cairn Research UK) filtered by a GG 475 filter (resulting λmax 546 nm). The green illumination was calibrated in terms of effectively absorbed photons by counting quantum bumps in whole-cell recordings or, for in vivo measurements from the DPP, by measuring the rate at which it converted M to R spectrophotometrically in the same set up, as previously described [26].

2.4. GCaMP6f calibration

Maximum and minimum fluorescence of GCaMP6f in situ was calibrated by exposing dissociated ommatidia to ionomycin (10 μM) and then perfusing alternately for several minutes with 10 mM K2EGTA 100 mM KCl 10 MOPS pH 7.2 (nominally 0 Ca2+) and 10 mM CaEGTA 100 mM KCl 10 MOPS (nominally 40 μM Ca2+) (solutions from Biotium Ca2+ calibration buffer kit). After background subtraction, ΔF/F0 with the saturating 40 μM Ca2+ solution (Fmax) was 23.5 ± 1.52 (mean ± S.E.M. n = 8), which is close to the published in vitro value of 25 [35]. For estimating absolute cytosolic Ca2+ levels [Cai] from ΔF/F0 values, we assumed our Fmax value of 23.5, the published Kd value (290 nM), and Hill slope (n = 2.7) [35] using the equation:

| [Cai] = {Kd. (ΔF/F0)1/n}/{Fmax − (ΔF/F0)}1/n | (1) |

3. Results

3.1. GCaMP6f Ca2+ signals under physiological conditions

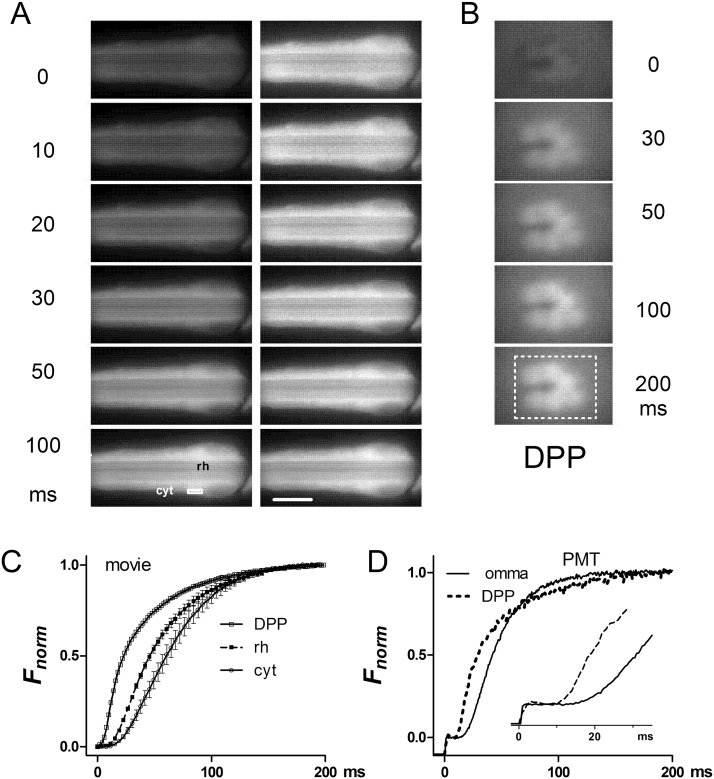

In order to monitor Ca2+ in Drosophila photoreceptors we expressed GCaMP6f directly under the control of the Rh1 opsin (ninaE) promoter (see methods), thereby driving expression specifically in the major photoreceptor class (R1-6). Whole-cell recordings from photoreceptors of these flies (ninaE-GCaMP6f) showed that their basic light responses were indistinguishable from wild-type (Fig. 1). Imaging of dissociated ommatidia revealed GCaMP6f diffusely distributed throughout the photoreceptors, with a weaker, though distinct signal in the rhabdomeres (Fig. 2, Fig. 5A). Other similarly sized GFP-tagged constructs (eg arrestin-GFP or PH-domain tagged GFPs) diffuse in and out of the microvilli within seconds [25], [26], so the weaker rhabdomere signal is presumably because of the small volume fraction of free cytosol in this membrane rich compartment rather than exclusion from rhabdomeres. High frame rate (100–500 Hz) movies showed a rapid increase in fluorescence (latency ∼10 ms) in response to the blue excitation, originating in the rhabdomeres and immediately adjoining cytosol, spreading outwards to the rest of the ommatidium with a lag of 10–20 ms to the outer edge of the cells (Fig. 2A,C; Movie 1). Fluorescence from the rhabdomeres can also be imaged in completely intact animals by focussing a low power objective in the depth of the eye to visualise the “deep pseudopupil” (DPP: Fig. 2 B) [24]. Rather than recording and analysing high frame rate movies, it is much more convenient to measure the fluorescence from either dissociated ommatidia or the DPP via a photomultiplier tube (PMT) using a portion of the field cropped by a diaphragm. Fig. 2D shows representative raw PMT traces of GCaMP6f fluorescence recorded in response to blue excitation light from a dissociated ommatidium and from the DPP in a completely intact fly. During a ∼10–20 ms latent period there is a clearly resolvable “pedestal”, which reflects GCaMP6f fluorescence corresponding to the initial dark-adapted Ca2+ concentration. After background correction (estimated from identical measurements in flies lacking GCaMP6f), the fluorescence rapidly rose to ΔF/F0 values >10 within ∼200 ms. Although the signals were broadly similar, responses recorded from the DPP were faster than those recorded in dissociated ommatidia, probably because the DPP samples fluorescence predominantly from the rhabdomeres, whilst the ommatidium signal is dominated by cytosolic GCaMP6f. Apart from the pedestal (F0) and Fmax values, these signals per se are relatively uninformative: firstly because the blue excitation light is a super-saturating, non physiological stimulus, and secondly because GCaMP6f, with a Kd of 290 nM in vitro [35] should be saturated by Ca2+ concentrations in excess of ∼1–2 μM, whilst [Ca2+] in the photoreceptor is believed to reach values close to 1 mM in the rhabdomere and 10–50 μM in the cell body [17], [18].

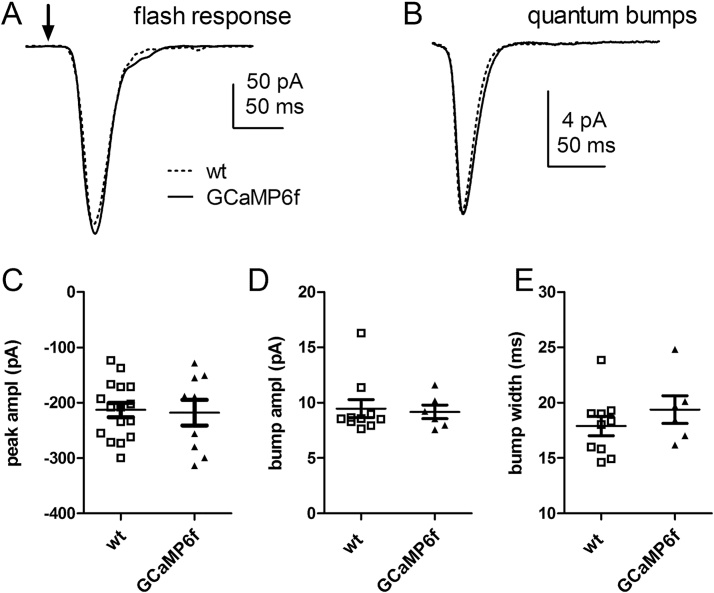

Fig. 1.

Light-induced currents from photoreceptors expressing GCaMP6f.

(A) Whole-cell recordings of light-induced current responses to brief (1 ms) flashes (arrow), containing ∼100 effectively absorbed photons in a wild-type photoreceptor and a photoreceptor from ninaE-GCamP6f fly (each an average of 3 responses, voltage-clamped at −70 mV). (B) Averaged quantum bumps (after aligning rising phases) from wild-type (n = 10 cells, ∼40-60 bumps per cell) and GCaMP6f expressing photoreceptors (n = 6 cells). (C) Peak amplitudes to test flashes in wild-type (n = 16) and GCaMP6f expressing photoreceptors (n = 9) were indistinguishable (P = 0.846, 2-tailed t-test). (D & E) bump amplitudes and half-widths in wild-type (n = 10) and GCaMP6f expressing photoreceptors (n = 6) also showed no significant differences (P = 0.78 and 0.32 respectively).

Fig. 2.

Live imaging of GCaMP6f.

(A) GCaMP6f fluorescence in a dissociated ommatidium (distal end) from ninaE-GCaMP6f fly: 6 frames from 250 Hz movie (4 ms exposures; see Movie 1) at t = 0 to 100 ms after turning on blue excitation. Images on left are raw images with brightness and contrast adjusted with respect to the same (brightest) frame; images on right are the same but with brightness and contrast individually auto-adjusted. Scale bar 10 μm (×40 oil immersion objective). (B) Frames from a similar movie of GCaMP6f in rhabdomeres imaged in the deep pseudopupil (DPP) of an intact living ninaE-GCaMP6f fly (x 20 air objective). (C) Time-courses from movies (as in A & B). In dissociated ommatidia, regions of interest from rhabdomeres (rh) and cytosol (cyt) towards edge of the ommatidium (white box in A) were selected. For DPP a rectangle encompassing all 6 rhabdomeres was selected. Mean ± S.E.M. n = 5-6 ommatidia. Traces normalised to facilitate comparison of time course: maximum ΔF/F0 values were in range 11–18 (see Fig. 3). (D) Normalised raw photomultiplier tube traces (PMT) sampled at 1 kHz, filtered at 0.5 kHz from ninaE-GCaMP6f flies. Representative single traces in response to supersaturating blue excitation are shown recorded from a dissociated ommatidium in normal bath (omma) and in vivo from the deep pseudopupil (DPP). Rising phases of the same traces shown in inset.

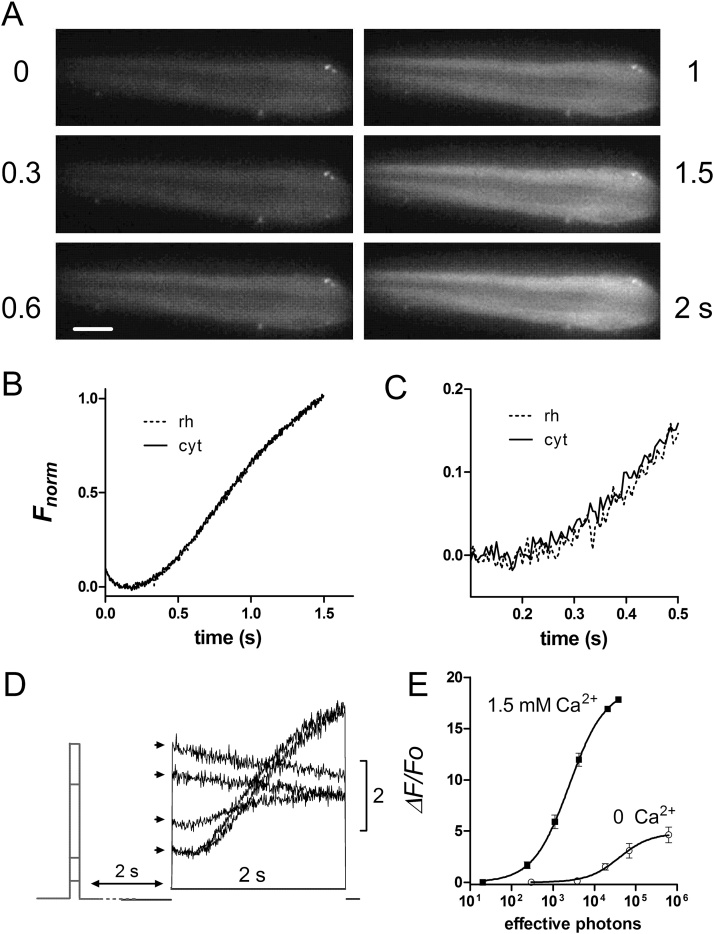

Fig. 5.

Image analysis and intensity dependence of Ca2+ free rises in dissociated ommatidia.

(A) Six frames (0–2s) from a 100 Hz (10 ms exposure) movie (see Movie 2) of wild-type ninaE-GCaMP6f ommatidium in Ca2+ free bath (0 Ca2+, 1 mM EGTA 120 mM Na+). Brightness and contrast in all frames auto-adjusted to the final (brightest) frame. Bright spots towards distal (right) end of the ommatidium are autofluorescent pigment granules. Scale bar 10 μm. (B) Average time-courses (n = 6 ommatidia) from regions of interest covering rhabdomeres (rh) and cytosol (cyt) show near perfect overlap. Traces normalised to facilitate comparison of time-course: maximum ΔF/F0 values were in range 2–5. (C) Rising phase on faster time base. (D) PMT fluorescence traces from a wild-type ninaE-GCaMP6f ommatidium, perfused with Ca2+ free bath (1 mM EGTA) for ∼30s. Brief (10 ms) green flashes of increasing intensity (0, 4000, 20000, 70000 and 600000 effective photons) were presented 2 s before the 2 s blue excitation. The instantaneous fluorescence “pedestals” (arrows) reflects the Ca2+ level reached in response to the green flashes. (D) Resulting F/log I function (mean ± S.E.M. n = 4) compared to data from ommatidia in normal bath (1.5 mM Ca2+ replotted from Fig. 3).

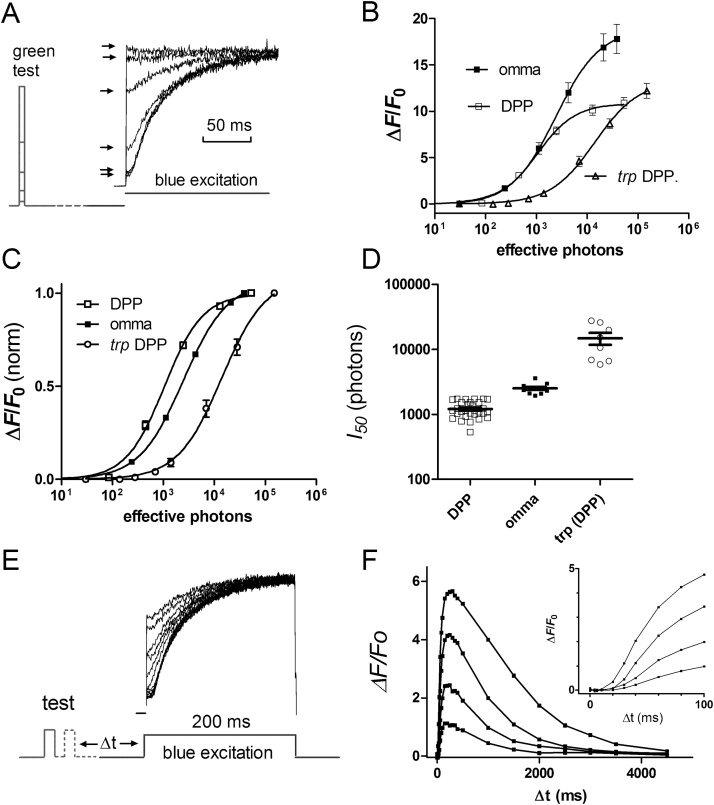

In order to measure the intensity dependence of the Ca2+ rise with respect to physiologically relevant intensities we used 2-pulse protocols in which brief (1–2 ms) calibrated flashes of green light were delivered 300 ms before measuring fluorescence (Fig. 3). The pedestals in these traces are still clearly resolvable but now reflect the Ca2+ level reached in response to the preceding test flash. The resulting F/log I functions had a steep intensity dependence with a threshold around 100 effectively absorbed photons, with 50% Fmax reached with intensities of ∼1000 photons (mean 1214 ± 64 S.E.M. n = 28) and saturating at intensities of 10000–30000 photons when measured in vivo from the DPP (Fig. 3 D). F/log I functions recorded from dissociated ommatidia were similar to those recorded in vivo from the DPP; however, the curves were slightly less steep and sensitivity ∼2-fold less (2516 ± 162 effective photons, n = 9 required to elicit 50% Fmax). The small difference in sensitivity may again reflect the predominantly rhabdomeric (DPP) vs cytosolic (dissociated ommatidium) source of the signals; but may also reflect the influence of the dissociation procedure, axial (DPP) as opposed to side-on (ommatidia) illumination, and/or the very different methods used to calibrate intensity; namely counting quantum bumps in whole-cell recordings from dissociated ommatidia, as opposed to measuring the metarhodopsin to rhodopsin photoisomerisation rate spectrophotometrically for the DPP (see methods 2.3).

Fig. 3.

Intensity and time dependence of GCaMP6f signals using 2-pulse protocols.

(A) 2 ms green flashes of different intensities were delivered 300 ms prior to blue excitation to measure GCaMP6f fluorescence from the DPP in completely intact ninaE-GCaMP6f flies. The pedestals (arrows) reflect the Ca2+ level in response to the green test flash (first response dark-adapted, i.e. without pre-flash). (B) resulting intensity dependence (F/log I function) after background correction, with respect to F0 during dark adapted “pedestal”. Data from trp (DPP) also included, along with results from dissociated wild-type ommatidia. (C) Same data normalised.

(D) Summary of sensitivity data: expressed in terms of number of effectively absorbed photons required to generate 50% Fmax. (E) 2-pulse protocol using brief (2 ms) flashes of the same intensity delivered with variable delay in order to measure the time course of GCaMP6f responses (in vivo from DPP). (F) Family of resulting impulse responses to flashes of increasing intensity (∼150,450,1250,5000 effective photons): inset shows the first 100 ms on a faster time base. In all experiments, after each blue excitation flash, M was reconverted to R by an intense, photo-equilibrating 4 s orange stimulus and the fly left in the dark for 1 min before the next test flash. Longer dark adaptation times result in slightly larger responses, but 1 min was chosen as a compromise to allow sufficient data collection (e.g. each time course trace in panel F required 24 repeated cycles- or ∼25 min – to record).

We also expressed GCaMP6f in trp343 null mutant flies lacking the dominant and more Ca2+ permeable of the two light-sensitive channels. Although maximum ΔF/F0 values to saturating illumination were similar to wild-type (12.1 ± 2.3 n = 8; DPP measurements), F/log I functions determined with 2-pulse protocols were ∼10–20 x less sensitive, with 50% Fmax obtained with brief flashes containing 14800 ± 3100 (n = 8) effective photons (Fig. 3).

In order to measure the time course of Ca2+ responses we used similar 2-pulse protocols, this time presenting repeated brief (2 ms) flashes whilst varying the delay of the blue excitation light. Depending on intensity, Ca2+ rises were observed with latencies of ∼10–25 ms, peaking in 200–300 ms and then returning to baseline over a period of 2–4 s with a half time (t½) of ∼900 ms with dimmer test flashes (Figs. 3E,F and 6C,D). With brighter flashes, recoveries became somewhat slower, and with saturating flashes (∼30,000 photons) ΔF/F0 remained high for 1–2 s, before recovering with a t½ of 3–4 s, still reaching baseline levels within ∼10 s (Fig. 3 and see also Fig. 7).

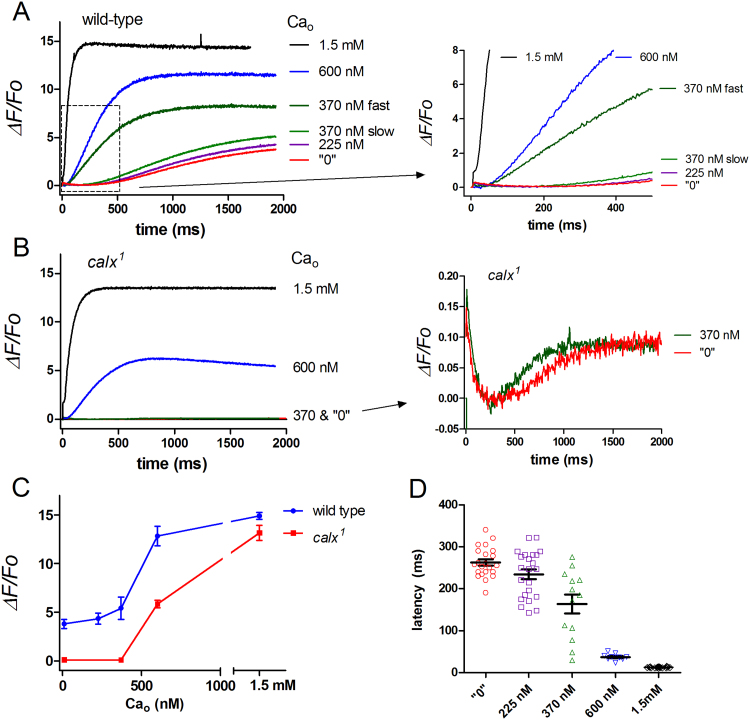

Fig. 6.

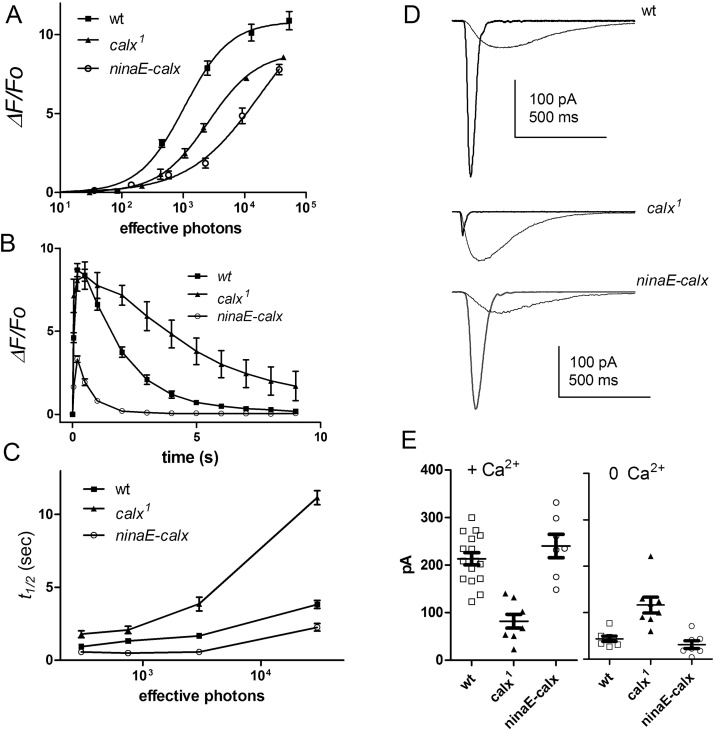

Effect of Na+/Ca2+ exchange on GCaMP6f signals in Ca2+ free solutions.

(A) GCaMP6f fluorescence traces in response to blue excitation in 0 Ca2+ bath (1 mM EGTA) in dissociated ommatidia expressing GCaMP6f in wild-type, calx1 mutants lacking exchanger activity and in ninaE-calx flies over-expressing the exchanger. Traces are mean ± S.E.M. n = 6-8 ommatidia. (B) calx1 GCaMP6f trace (mean ± S.E.M. n = 6) replotted at high gain. (C) maximum ΔF/Fo values (after 2 s) from wild-type, calx1 and ninaE-calx backgrounds in both normal bath (Ca2+) and Ca2+ free bath (0 Ca2+) with normal Na+. (D) wild-type, calx1 and ninaE-calx Ca2+ free ΔF/F0 values replotted on log10 plot along with 0 Ca2+ 0 Na+ data (Cs+ substitution) from wild-type and ninaE-calx.

Fig. 7.

Effects of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger expression under physiological conditions.

(A) GCaMP6f F/log I functions determined in vivo using 2-pulse DPP protocols (as in Fig. 3) in wild-type background (replotted from Fig. 3), calx1 mutants (n = 7) and ninaE-calx flies (n = 5) over-expressing the exchanger. (B) Time courses of responses to brief 2 ms flashes containing ∼3000 effective photons (DPP 2-pulse data: mean ± S.E.M. n = 5−6 flies) in wild-type, calx1 and ninaE-calx. (C) Time to 50% recovery (t½) of GCaMP6f signal as a function of intensity of flash (mean ± S.E.M. n = 4-9 flies) in wild-type, calx1 and ninaE-calx flies (from time courses as in B).

(D) Whole-cell recordings of light-induced currents in response to 1 ms flashes containing ∼100 effective photons in normal bath (rapid responses) and in Ca2+ free (1 mM EGTA) bath in wild-type, calx1 and ninaE-calx photoreceptors (averages of 3 responses). (E) Summary of data: peak amplitudes in normal bath (left, + Ca2+) and Ca2+ free bath (right, 0 Ca2+). Ca2+ free responses were significantly (P < 0.001) larger in calx1 mutants, and slightly (though not significantly: P = 0.23) decreased in ninaE-calx; whilst calx1 responses were significantly (P < 0.001) smaller than wild-type in the presence of Ca2+.

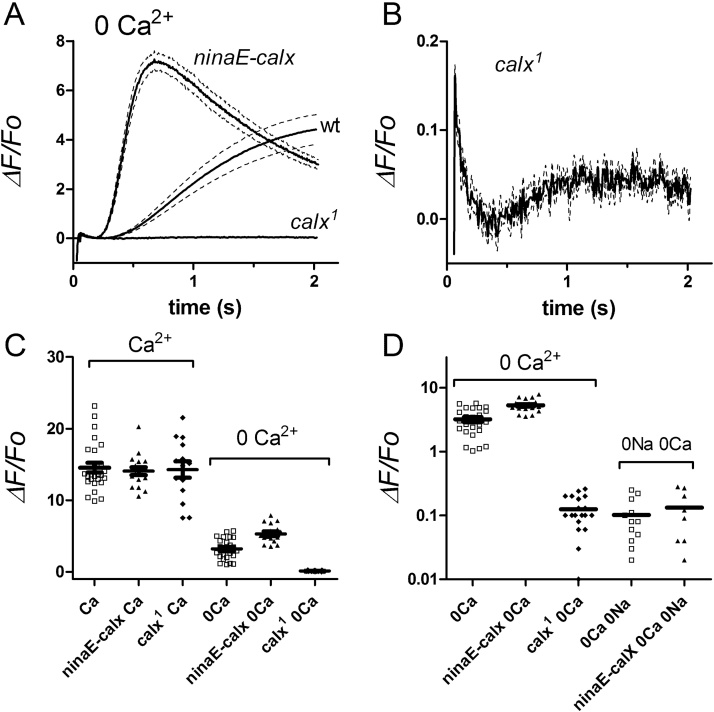

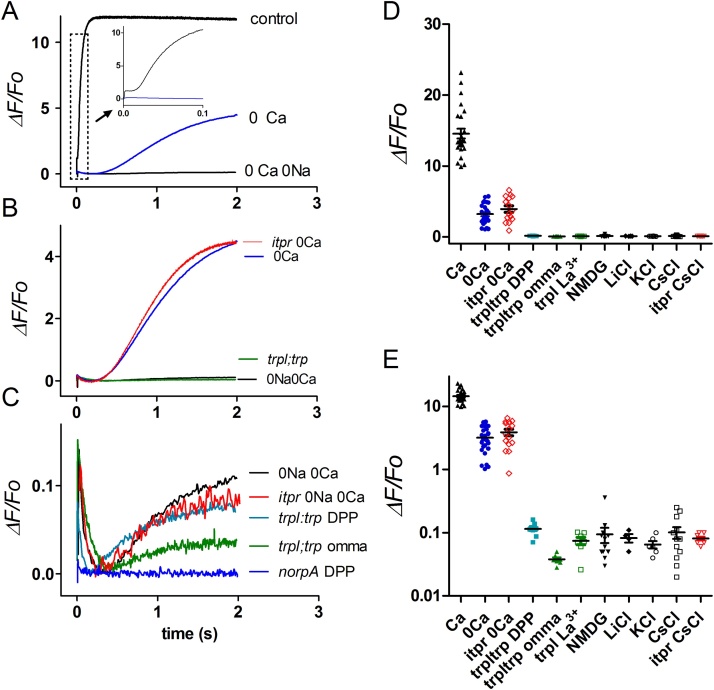

3.2. Ca2+ signals in Ca2+ free solutions

In dissociated ommatidia perfused with Ca2+ free solutions (0 Ca2+, 1 mM EGTA) there is a smaller and slower rise in Ca2+, the source and role of which is controversial [16], [17], [20], [21], [22]. In ninaE-GCaMP6f flies, this “Ca2+ free” signal can be recorded with excellent signal-to-noise ratio and reached ΔF/Fo values of ∼1-6 (mean ∼3.2 ± 0.3 n = 24) after 2 s, which is now well within the dynamic range of GCaMP6f. Importantly, there was no detectable rise until at least ∼200 ms after light onset (Fig. 4), which would be too slow to have any influence on the rising phase of the electrical light response. In high frame rate movies (100–200 Hz), the Ca2+ appeared to rise more or less simultaneously across the ommatidium without any indication of a localised initial “release”, although the slow time course means that short time differences (10–20 ms) would not be reliably resolved (Fig. 5A–C; Movie 2). Assuming a resting baseline [Ca2+]i of 50 nM in Ca2+free bath [17], a Kd for GCaMP6f of 290 nM, and Hill slope of 2.7 [35], the maximum ΔF/Fo values would be equivalent to a modest rise to ∼100–210 nM Ca2+. We measured the intensity dependence of the Ca2+ free response using 2-pulse paradigms, presenting brief (10 ms) calibrated flashes 2 s before the blue excitation. Now, approximately 40000 effectively absorbed photons (>1 per microvillus) were required to elicit a 50% rise, which is ∼20–40 x more than for responses in physiological (Ca2+ containing) solutions or in vivo (Fig. 5D,E).

Fig. 4.

Dependence of GCaMP6f signals on Ca2+ and Na+ influx.

(A–C): Fluorescence signals (PMT) measured from dissociated ommatidia expressing GCaMP6f. Traces are averages of 4–10 traces plotted as ΔF/Fo (using F0 values measured in Ca2+ free bath from same ommatidia). In control bath (1.5 mM CaCl2) values in excess of 10 were reached within 0.1 s (see inset of boxed area on expanded scale). In Ca2+ free (0 Ca2+, 1 mM Na2EGTA) bath there was a slow rise to ∼4, but with no detectable increase for at least 200 ms. In Ca2+ and Na+ free solutions (average of data recorded in 130 mM CsCl, LiCl, KCl or NMDG Cl, all with 1 mM K2EGTA 0 Ca2+ and 4 mM MgCl2), this slow response was almost eliminated leaving a slow rise to a ΔF/Fo of only ∼0.1. (B) and (C) show same traces on different scales, with data from trpl;trp flies recorded in control bath solution (omma) and in vivo using the DPP, as well. Neither 0Ca or 0Ca 0Na responses were affected in null IP3R mutants (itpr). Note the initial transient decrease (origin uncertain), which is as large as the subsequent slow increase. These residual signals were both effectively eliminated in null PLC mutants (norpA DPP, n = 6). (D) and (E) Maximum ΔF/Fo values (2 s after light onset) in dissociated ommatidia in different bath solutions, and trpl;trp measured in vivo using the DPP). Data from wild-type background unless otherwise indicated (trpl;trp trpl plus La3+, and itpr). Same data plotted on linear (D) and log10 scales (E).

GCaMP6f signals in Ca2+ free bath were also characterised by an initial small transient decrease in fluorescence (ΔF/F0 ∼ 0.1). The source of this is uncertain [22], but it was absent in norpAP24 null PLC mutants (Fig. 4C), and had a similar time course to the pH drop measured using pH-sensitive dyes [34]. Because GCaMP6f fluorescence, like other GFP-based probes, is suppressed at acid pH (Hardie R.C. unpublished), one possibility is that it reflects pH sensitivity of GCaMP6f fluorescence in response to protons released by the PLC reaction[34].

Light-induced release from internal (InsP3-sensitive) Ca2+ stores would seem the most obvious explanation for the Ca2+ free signal; however, we found that it was completely unaffected in null mutants (mosaics) of the only InsP3 receptor gene (itpr) in the Drosophila genomes (Fig. 4B). This is in agreement with a previous study using Ca2+ indicator dyes in itpr mutants [21], but contrary to a recent study using GCaMP6f, where the Ca2+ rise in Ca2+ free solution was reported to be attenuated following IP3R RNAi knockdown [22]. It is difficult to reconcile these apparently contradictory results; however, we note that the signals we recorded in Ca2+ free solutions were slower than those reported by these authors in control ommatidia, but had similar time-courses to their responses in IP3R-RNAi flies. These authors used whole bath perfusion with a lower concentration of EGTA (0.5 mM) than our standard Ca2+ free solution (1 mM EGTA). We therefore also repeated measurements using 0.5 mM EGTA both in puffer pipettes and also after whole bath perfusion, but again in every case (n = 17 ommatidia in 6 flies) only slow (∼200 ms latency) responses were observed. Very occasionally (<5% of more than 100 ommatidia) we did see a more rapid Ca2+ signal; however, it was immediately clear that this was due to failure to adequately perfuse the ommatidium with Ca2+ free solution (e.g. a blocked puffer pipette). We can only speculate that a similar explanation may account for the rapid signals reported by Kohn et al. [22].

3.3. GCaMP6f signals in Ca2+ and Na+ free solutions

In an early study using the ratiometric indicator INDO-1 we reported that extracellular Na+ was required in order for a significant light-induced rise of cytosolic Ca2+ in Ca2+ free solutions [17]. Here we confirmed and extended this finding using GCaMP6f. Following perfusion of dissociated ommatidia by puffer pipette with EGTA buffered Ca2+ free and Na+ free solution, the initial transient decrease in fluorescence remained, but the subsequent rise was almost eliminated (Fig. 4). This was true whether Na+ was substituted for a range of similarly permeant monovalent cations (Li+ Cs+ or K+) or an essentially non-permeant cation (NMDG+).

Previously we suggested that the requirement of extracellular Na+ for a substantial Ca2+ free rise might reflect re-equilibration of Na+/Ca2+ exchange following the massive Na+ influx associated with these stimuli [17]. However, Cook and Minke [20] argued that only a Na+ gradient, and not Na+ influx, was necessary and suggested some other Na+ dependent process was required for release from internal stores. To test the requirement for Na+ influx, as opposed to a Na+ gradient we expressed GCaMP6f in trpl;trp double null mutants lacking all light-sensitive channels [9], [10], and hence all light-induced Na+ and Ca2+ influx, irrespective of the extracellular solution. Now, even in the presence of normal external Na+ and Ca2+, the GCaMP6f signal was at least as severely reduced as in wild-type ommatidia bathed in Ca2+ and Na+ free solutions, leaving again a tiny slow rise to a maximum ΔF/Fo of <0.1 after 1–2 s (Fig. 4). In trpl;trp mutants, measurements without Ca2+ or Na+ influx could also be made in vivo from completely intact flies by measuring GCaMP6f fluorescence from the DPP. Even after prolonged (>3 h) dark adaptation, these measurements yielded similar results, with at most a tiny rise similar to that recorded in dissociated ommatidia (Fig. 4C).

We considered the possibility that the lack of a significant Ca2+ rise in trpl;trp mutants might be because potential light-sensitive internal Ca2+ stores were permanently depleted due the chronic lack of a Ca2+ influx pathway in the double mutant. To test for this we recorded GCaMP6f signals from ommatidia in trpl mutants in physiological solutions. The light responses in trpl are mediated exclusively by TRP channels and although almost indistinguishable from wild-type under physiological conditions, can be completely blocked by the TRP channel blocker, La3+ [9]. Correspondingly, the Ca2+ influx GCaMP6f signal prior to La3+ application in trpl flies was similar to wild-type (ΔF/Fo > 10); however, following perfusion with La3+ (100 μM, 20–30 s application by puffer pipette) in the same ommatidia, only a tiny slow rise similar to that seen in Ca2+ and Na+ free solutions, or in trpl;trp double mutants remained (Fig. 4D,E).

Although it seemed reasonable to suspect that the tiny residual rise in trpl;trp or Na+ and Ca2+ free solutions might finally represent the rise due to InsP3-induced Ca2+ release, even this signal was still retained in ommatidia from itpr null mosaic eyes (Fig. 4C–E). The origin of this residual signal therefore remains uncertain. Given that it is of similar size to the initial transient decrease, it might also represent relaxation of this transient, and one cannot be confident that it still reflects a Ca2+ signal. Both the transient decrease and the subsequent slow rise/relaxation do however, seem to be PLC-dependent as neither signal could be detected in the null PLC mutant norpAP24 (Fig. 4C).

In summary, these results indicate that Na+ influx, and not simply extracellular Na+, is required for a significant light-induced rise in Ca2+ in Ca2+ free solutions. The maximum residual fluorescence increase in the absence of Na+ or Ca2+ influx (ΔF/Fo ∼ 0.1) would reflect a Ca2+ rise of the order of ∼10 nM. This signal developed slowly, was only detectable with very bright stimuli, was unaffected by the IP3R null mutation, and because of its tiny size one cannot even be confident it represents a Ca2+ signal.

3.4. Genetic manipulation of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger

If the normal Ca2+ free rise is due to re-equilibration of Na+/Ca2+ exchange following Na+ influx [17], we predicted that the rise should be prevented or reduced in mutants of the exchanger (encoded by the calx gene). We therefore expressed GCaMP6f in the severe calx hypomorph, calx1, which has no detectable exchanger activity [30]. As predicted, on perfusion with EGTA buffered Ca2+ free solution we were no longer able to detect any light-induced increase in GCaMP6f fluorescence in calx1 mutants beyond a tiny residual signal similar to that seen in Ca2+ and Na+ free solutions in wild-type backgrounds (Fig. 6). By contrast, the Ca2+ rise in vivo (DPP) or from dissociated ommatidia in normal bath (i.e. 1.5 mM Ca2+) in calx1 flies was broadly similar to that in wild-type flies; however, reflecting the pivotal role of the exchanger in Ca2+ extrusion, recovery to baseline in the dark was much slower, particularly following brighter flashes (Fig. 7B–D). Sensitivity (from in vivo 2-pulse F/log I functions) was also approximately 2–3 x lower than in wild-type (Fig. 7A).

In order to exclude the possibility that the loss of signal in Ca2+ free solutions was due to profound loss of responsivity, we made whole-cell recordings from calx1 mutants. As previously reported [30], in normal physiological Ringer (1.5 mM Ca2+), calx1 mutants showed an attenuated LIC, presumably due to the inhibitory effects of Ca2+. However, in Ca2+ free solutions, responses in calx1 were actually significantly larger than in wild-type (Fig. 7E,F). We also considered the possibility that a potential Ca2+ free rise in calx mutants was masked by a higher resting Ca2+ level. However, with respect to F0 in Ca2+ free solutions, maximum ΔF/F0 values in calx flies in the presence of Ca2+ were similar to wild-type values (Fig. 6). Assuming Fmax was saturated in both cases, this means that F0–and hence resting Ca2+ in Ca2+ free solutions – was also similar in wild-type and calx.

We also expressed GCaMP6f in ninaE-calx flies, which over-express a wild-type calx transgene in photoreceptors R1-6, resulting in a 5–8 fold increase in Na+/Ca2+ exchanger activity [30]. We reasoned that if the light-induced Ca2+ rise in Ca2+ free solutions was due to re-equilibration of the exchanger in response to Na+ influx, it would be paradoxically accelerated in these flies; but if the rise was due to release from intracellular stores, then increasing the exchanger activity would only suppress the observed rise, because any released Ca2+ would be more rapidly extruded from the cell. Strikingly, in these flies the rise in Ca2+ in EGTA buffered Ca2+ free bath was indeed dramatically accelerated (Fig. 6A). The increase in rate of rise (∼7 fold) closely mirrored the increase in the exchanger current activity in ninaE-calx flies (5-fold faster, 8-fold larger in response to rapid Na+ substitution [30]), suggesting the rise may be directly attributable to exchanger activity. On average, the maximum ΔF/F0 values reached were also significantly higher (5.3 ± 0.3 n = 17, P < 0.001 2-tailed t-test) than in otherwise wild-type flies. The accelerated Ca2+ free rise in ninaE-calx flies was still dependent upon Na+ influx because it was no longer seen after perfusion with Ca2+ and Na+ free solutions (Na+ substituted for Cs+), leaving instead a tiny residual rise similar to that in wild-type Ca2+ and Na+ controls (Fig. 6D). Finally, we asked whether the accelerated Ca2+ free rise might be explained by an unanticipated increase in responsivity; however, in whole-cell recordings from ninaE-calx photoreceptors in Ca2+ free solutions, sensitivity to light was if anything reduced compared to wild-type (Fig. 7 E,F), though this did not reach statistical significance on this sample (n = 7).

In marked contrast, under physiological conditions (using 2-pulse in vivo DPP measurements), over-expression of the exchanger in ninaE-calx flies had the predictable and opposite effect of suppressing Ca2+ rises in the F/log I function and also accelerating recovery to baseline (Fig. 7A–C); again supporting the dominant role of the exchanger in Ca2+ extrusion under physiological conditions.

In summary, our results show that the Ca2+ rise observed in Ca2+ free solutions is not only strictly dependent upon Na+ influx, but also strictly dependent on the activity level of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Although we cannot completely exclude the possibility that the role of the exchanger is indirect, the fact that the Ca2+ free rise is accelerated in flies over-expressing the exchanger, yet still directly (and acutely) dependent upon Na+ influx strongly suggests that the rise can be attributed to the activity of the exchanger in response to massive Na+ influx, as originally proposed [17].

4. Discussion

Although Ca2+ signals in Drosophila photoreceptors were first studied over 20 years ago using Ca2+ indicator dyes [15], [16], [17], only one, recent study had used genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators [22]. These authors measured signals from dissociated ommatidia using the Gal4-UAS system [36], combining UAS-GCaMP6f with GMR-Gal4, which drives expression throughout the retina including all photoreceptor classes as well as accessory cells such as pigment and cone cells [37]. GMR-Gal4 expression also causes significant abnormalities in photoreceptor structure and physiology (Bollepalli M, Kuipers M, Liu C-H, Asteriti S, Hardie RC unpublished results)[38]. In the present study, we generated flies in which GCaMP6f expression was driven directly via the Rh1 (ninaE) promoter ensuring exclusive expression in R1-6 photoreceptors with wild-type morphology and physiology. The excellent signal-to-noise ratio of recordings in ninaE-GCaMP6f flies was distinctly superior to that in GMR-Gal4/UAS-GCaMP6f flies, and in many cases the maximum ΔF/F0 ratio approached or exceeded 20 (cf ∼3 using GMR-Gal4/UAS-GCaMP6f [22]). This is close to the maximum value (23.5) determined by in situ calibrations (see methods 2.4) or in vitro [35]. Although the blue excitation light used for measuring GCaMP6f fluorescence is a super-saturating stimulus, 2-pulse paradigms allowed sensitive and accurate measurements of intensity and time dependence of signals in response to stimuli in the physiological range. Recordings in vivo from the DPP of intact flies are simple to perform and can be readily maintained over many hours, making this approach a valuable, and completely non-invasive tool for assessing in vivo photoreceptor performance. Even in the more vulnerable dissociated ommatidia preparation, multiple repeatable measurements could be made for up to at least an hour from the same ommatidium as long as metarhodopsin was reconverted to rhodopsin by long wavelength light after each measurement.

4.1. Ca2+ signals under physiological conditions

In vivo (DPP) or in dissociated ommatidia bathed in physiological solutions, the GCaMP6f signal reached 50% Fmax at intensities equivalent to ∼1000–2500 effectively absorbed photons. It is believed that the elementary single photon response (quantum bump) is generated by activation of Ca2+ permeable channels (TRP and TRPL) within a single microvillus and that the consequent Ca2+ rise in the affected microvillus reaches near mM levels [18], [19]. Because such levels inevitably saturate GCaMP6f (Kd 290 nM, saturating at 1–2 μM), to a first approximation the ΔF/F0 values under physiological conditions are probably best interpreted as the proportion of microvilli “flooded” with Ca2+. In total, the rhabdomere contains ∼30000 microvilli, meaning that 50% Fmax is reached when only ∼3–8% of the microvilli have been activated by a photon. This implies that the Ca2+ influx into a single microvillus must spread to at least the immediately neighbouring microvilli within the timeframe of the response. In ninaE-calx flies over-expressing the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, or in trp mutants lacking the major Ca2+ permeable channel, 50% Fmax was only obtained with flashes containing ∼ 12000-15000 effective photons, which should activate ∼50% of the microvilli, suggesting that in these flies Ca2+ is largely prevented from spreading to neighbouring microvilli under the same conditions.

The dark-adapted “pedestal” level can be used to gain an estimate of the resting Ca2+ concentration in dissociated ommatidia (in physiological solutions) assuming in vitro calibration data [35]. With reference to F0 measured in Ca2+ free solution in the same ommatidia, the mean dark-adapted value in normal bath was 0.77 ± 0.14 (mean ± S.E.M. n = 11), which would be equivalent to ∼80 nM (assuming Kd = 290 nM and Fmax 23.5 and Eq. (1) see methods 2.4). This value was significantly lower in ninaE-calx flies over-expressing the exchanger (0.19 ± 0.04 n = 11 equivalent to ∼50 nM) and higher in calx1 mutants (1.94 ± 0.24 n = 14 equivalent to ∼120 nM).

The recovery of GCaMP6f fluorescence to baseline is likely to be a reasonably accurate reflection of the falling Ca2+ levels during response recovery, although the initial decrease (from initial ∼mM levels to low μM levels) will still be subject to saturation effects. With relatively dim flashes (up to ∼1000 effectively absorbed photons) the GCaMP6f signal in wild-type backgrounds fell to near baseline within ∼2–3 s with a half time (t ½) of ∼1 s (Figs. 3, 7). This is slower than the GCaMP6f off-rate (∼200 ms), and thus likely to approximate the true time-course of Ca2+ recovery. The recovery was significantly accelerated in ninaE-calx flies (∼500 ms), and slowed in calx1 mutants (∼2 s increasing to >10 s following brighter flashes; Fig. 7), consistent with a dominant role of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in Ca2+ extrusion [30]. Nevertheless, even after bright flashes, given sufficient dark-adaptation time (∼30–60 s), resting [Ca2+] in calx1 mutants fell to levels close to those in dark-adapted wild-type photoreceptors, reflecting either residual function of the exchanger in this hypomorphic mutant and/or alternative extrusion mechanism(s).

4.2. Origin of the Ca2+ rise under Ca2+ free conditions

The smaller signals recorded in Ca2+ free bath fall within the dynamic range of GCaMP6f and allow estimates of the absolute Ca2+ levels reached under these conditions (e.g. ΔF/F0 of 6 corresponds to ∼200 nM). We used these signals to investigate the long disputed origin of the light-induced rise in cytosolic Ca2+ in Ca2+ free solutions. Originally, using INDO-1, we found that this Ca2+ free rise was dependent upon extracellular Na+ and suggested that the rise might be due to re-equilibration of Na+/Ca2+ exchange in response to the massive light-induced Na+ influx that persists under these conditions [17]. This was challenged by Cook and Minke [20] who confirmed the requirement of external Na+ for a significant Ca2+ rise in Ca2+ free solutions, Na2+, but reported that a rise still occurred in Ca2+ free bath in the presence of Na+ when the photoreceptors were voltage clamped at the Na+ equilibrium potential to prevent Na+ influx. They concluded that a Na+ gradient − but not influx − was required, that the Ca2+ free rise reflected release from internal stores, and that the requirement of extracellular Na+ reflected involvement of some other Na+ dependent process, such as Na/H transport. But how this might affect release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores is far from clear. A more recent study from the same lab reported that the Ca2+ free rise was attenuated following RNAi knockdown of the IP3R [22]. However, this is difficult to reconcile with an earlier study using INDO-1, where the rise was found to be unaffected in null IP3R mosaic eyes [21] and confirmed again here using GCaMP6f (Fig. 4).

In the present study we used a variety of approaches to investigate the source of this Ca2+ free signal further. We first confirmed that it was all but abolished in the absence of external Na+, whether substituted for Li+, Cs+, K+ or NMDG+. Importantly, we found that the rise was also effectively eliminated in trpl;trp double mutants both in vivo and in dissociated ommatidia despite the presence of normal extracellular solutions containing both Na+ and Ca2+. Although it might be argued that, for some reason, PLC activity (and hence InsP3 generation) was compromised in trpl;trp mutants, convincing evidence indicates that net PLC activity is in fact greatly enhanced in trpl;trp due to the lack of Ca2+ and PKC dependent inhibition of PLC. Thus the rate and intensity dependence of PIP2 hydrolysis, measured using GFP-tagged PIP2 binding probes are greatly enhanced in trpl;trp mutants [26], as are the PLC-induced photomechanical contractions [39], and the acidification due to the protons released by the PLC reaction [34]. Overall, therefore these results strongly suggest that Na+ influx is indeed required for the Ca2+ free rise. Crucially, the involvement of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in this rise was confirmed by finding that it was essentially eliminated in an exchanger mutant (calx1), but greatly accelerated in ninaE-calx photoreceptors over-expressing the exchanger (Fig. 6).

The question remains, how Na+/Ca2+ exchanger activity could generate such a sizeable Ca2+ signal (∼100–200 nM) in cells perfused with EGTA buffered solutions, when free Ca2+ in the bath should be reduced to low nM levels. We do not have an unequivocal answer to this, and assuming the standard equation for the Na+/Ca2+ exchange equilibrium

| (2) |

it would seem difficult for reverse Na+/Ca2+ exchange to raise Ca2+ into the range we observed. However, at least three, not mutually exclusive factors might result in higher cytosolic Cai levels than predicted. Firstly, external Ca2+ might be relatively resistant to buffering in the intra-ommatidial space, and specifically the extremely narrow spaces between the microvilli or their bases, where the exchanger is believed to be localised [30], [40]. For example, with 500 nM Cao remaining, Eq. (2) predicts 130 nM Cai would be reached with 70 mM Nai, 110 mM Nao and the cell depolarised to 0 mV (values that could realistically be reached with the huge inward Na+ currents flowing under these conditions). Although one might also expect Ca2+ influx via the light-sensitive channels at such Cao concentrations, experiments buffering external Ca2+ at different concentrations with EGTA showed that direct Ca2+ influx signals could only be detected once external Ca2+ was raised above ∼400 nM (Suppl. Fig. 1). Secondly, resting cytosolic Ca2+ concentration is determined not only by the exchanger, but also by any other Ca2+ fluxes, which might include tonic leakage from intracellular compartments such as endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or mitochondria. Massive Na+ influx would compromise the ability of the exchanger to counter any such fluxes. A third possibility is that, contrary to conventional dogma, the exchanger might also be expressed on intracellular membranes of endoplasmic reticulum or other Ca2+ containing compartments and that Na+ influx leads to re-equilibration of Na+/Ca2+ exchange across these.

Whatever the exact mechanism, our results indicate that the Ca2+ rise in Ca2+ free bath is strictly dependent upon both Na+ influx and the activity level of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, but unaffected in null IP3R mutants. Its time-course, with no detectable rise for ∼200 ms, also appears much too slow to play any role in initiating the light response, which has a latency of ∼10 ms and peaks within ∼100–200 ms in response to bright illumination even under Ca2+ free conditions [34][e.g. 34]. The residual GCaMP6f signal remaining in the absence of Na+ influx and/or in the absence of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger activity − whether achieved by Na+ substitution, trpl;trp or calx mutants − was also still observed in IP3R mutants and was so small that it is questionable whether it reflects a Ca2+ signal. Because of the rapid inhibition of PLC by Ca2+ influx under physiological conditions [13], [34], [41] any presumptive PLC-mediated Ca2+ release under physiological conditions would be even less. Together with a study in which we found no phototransduction defects in null IP3R mutants (Bollepalli M,Kuipers M, Liu C-H, Asteriti S, Hardie RC unpublished results), these results suggest that InsP3-induced Ca2+ release plays no significant role in Drosophila phototransduction.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests

Author contributions

RCH conceived and designed the research, wrote the paper and performed and analysed Ca2+ imaging experiments. SA performed and analysed Ca2+ imaging and whole-cell electrophysiology experiments. C-HL performed molecular biology and fly genetics. SA and C-HL commented on the MS.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Marten Postma for comments on the MS. This project received funding from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/M00706/1 and BB/J009253/1; RCH, C-HL) and Horizon 2020 “European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No (658818-FLYghtCaRe RCH, SA).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ceca.2017.02.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Montell C. Drosophila visual transduction. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardie R.C., Juusola M. Phototransduction in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2015;34C:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz B., Minke B. Drosophila photoreceptors and signaling mechanisms. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2009;3:2. doi: 10.3389/neuro.03.002.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song Z., Postma M., Billings S.A., Coca D., Hardie R.C., Juusola M. Stochastic, adaptive sampling of information by microvilli in fly photoreceptors. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:1371–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson S.R., Reuss H., Hardie R.C. Single photon responses in Drosophila photoreceptors and their regulation by Ca2+ J. Physiol. Lond. 2000;524:179–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardie R.C., Minke B. The trp gene is essential for a light-activated Ca2+ channel in Drosophila photoreceptors. Neuron. 1992;8:643–651. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90086-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montell C., Rubin G.M. Molecular characterization of Drosophila trp locus, a putative integral membrane protein required for phototransduction. Neuron. 1989;2:1313–1323. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips A.M., Bull A., Kelly L.E. Identification of a Drosophila gene encoding a calmodulin-binding protein with homology to the trp phototransduction gene. Neuron. 1992;8:631–642. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90085-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niemeyer B.A., Suzuki E., Scott K., Jalink K., Zuker C.S. The Drosophila light-activated conductance is composed of the two channels TRP and TRPL. Cell. 1996;85:651–659. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reuss H., Mojet M.H., Chyb S., Hardie R.C. In vivo analysis of the Drosophila light-sensitive channels, TRP and TRPL. Neuron. 1997;19:1249–1259. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu C.H., Wang T., Postma M., Obukhov A.G., Montell C., Hardie R.C. In vivo identification and manipulation of the Ca2+ selectivity filter in the Drosophila Transient Receptor Potential Channel. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:604–615. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4099-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu B., Postma M., Hardie R.C. Fractional Ca2+ currents through TRP and TRPL channels in Drosophila photoreceptors. Biophys. J . 2013;104:1905–1916. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu Y., Oberwinkler J., Postma M., Hardie R.C. Mechanisms of light adaptation in Drosophila photoreceptors. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1228–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Tousa J.E. Ca2+ regulation of Drosophila phototransduction. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2002;514:493–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peretz A., Suss-Toby E., Rom-Glas A., Arnon A., Payne R., Minke B. The light response of Drosophila photoreceptors is accompanied by an increase in cellular calcium: effects of specific mutations. Neuron. 1994;12:1257–1267. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90442-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ranganathan R., Bacskai B.J., Tsien R.Y., Zuker C.S. Cytosolic calcium transients: spatial localization and role in Drosophila photoreceptor cell function. Neuron. 1994;13:837–848. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardie R.C. INDO-1 measurements of absolute resting and light-induced Ca2+ concentration in Drosophila photoreceptors. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:2924–2933. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-09-02924.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oberwinkler J., Stavenga D.G. Calcium transients in the rhabdomeres of dark- and light-adapted fly photoreceptor cells. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:1701–1709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01701.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Postma M., Oberwinkler J., Stavenga D.G. Does Ca2+ reach millimolar concentrations after single photon absorption in Drosophila photoreceptor microvilli? Biophys. J . 1999;77:1811–1823. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77026-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook B., Minke B. TRP and calcium stores in Drosophila phototransduction. Cell Calcium. 1999;25:161–171. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1998.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raghu P., Colley N.J., Webel R., James T., Hasan G., Danin M., Selinger Z., Hardie R.C. Normal phototransduction in Drosophila photoreceptors lacking an InsP3 receptor gene. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2000;15:429–445. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohn E., Katz B., Yasin B., Peters M., Rhodes E., Zaguri R., Weiss S., Minke B. Functional cooperation between the IP3 receptor and phospholipase C secures the high sensitivity to light of Drosophila photoreceptors in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:2530–2546. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3933-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen T.W., Wardill T.J., Sun Y., Pulver S.R., Renninger S.L., Baohan A., Schreiter E.R., Kerr R.A., Orger M.B., Jayaraman V., Looger L.L., Svoboda K., Kim D.S. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franceschini N., Kirschfeld K. Les phenomenes de psedoupille dans l'oeil compose de Drosophila. Kybernetik. 1971;9:159–182. doi: 10.1007/BF02215177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satoh A.K., Xia H., Yan L., Liu C.H., Hardie R.C., Ready D.F. Arrestin translocation is stoichiometric to rhodopsin isomerization and accelerated by phototransduction in Drosophila photoreceptors. Neuron. 2010;67:997–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardie R.C., Liu C.H., Randall A.S., Sengupta S. In vivo tracking of phosphoinositides in Drosophila photoreceptors. J. Cell Sci. 2015;128:4328–4340. doi: 10.1242/jcs.180364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Randall A.S., Liu C.H., Chu B., Zhang Q., Dongre S.A., Juusola M., Franze K., Wakelam M.J., Hardie R.C. Speed and sensitivity of phototransduction in Drosophila depend on degree of saturation of membrane phospholipids. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:2731–2746. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1150-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott K., Sun Y.M., Beckingham K., Zuker C.S. Calmodulin regulation of Drosophila light-activated channels and receptor function mediates termination of the light response in vivo. Cell. 1997;91:375–383. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80421-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pearn M.T., Randall L.L., Shortridge R.D., Burg M.G., Pak W.L. Molecular, biochemical, and electrophysiological characterization of Drosophila norpA mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:4937–4945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang T., Xu H., Oberwinkler J., Gu Y., Hardie R.C., Montell C. Light activation, adaptation, and cell survival Functions of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger CalX. Neuron. 2005;45:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venkatesh K., Hasan G. Disruption of the IP3 receptor gene of Drosophila affects larval metamorphosis and ecdysone release. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:500–509. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stowers R.S., Schwarz T.L. A genetic method for generating Drosophila eyes composed exclusively of mitotic clones of a single genotype. Genetics. 1999;152:1631–1639. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardie R.C., Martin F., Cochrane G.W., Juusola M., Georgiev P., Raghu P. Molecular basis of amplification in Drosophila phototransduction. Roles for G protein, phospholipase C, and diacylglycerol kinase. Neuron. 2002;36:689–701. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang J., Liu C.H., Hughes S.A., Postma M., Schwiening C.J., Hardie R.C. Activation of TRP channels by protons and phosphoinositide depletion in Drosophila photoreceptors. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badura A., Sun X.R., Giovannucci A., Lynch L.A., Wang S.S. Fast calcium sensor proteins for monitoring neural activity. Neurophotonics. 2014;1:025008. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.1.2.025008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brand A.H., Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hay B.A., Maile R., Rubin G.M. P element insertion-dependent gene activation in the Drosophila eye. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:5195–5200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kramer J.M., Staveley B.E. GAL4 causes developmental defects and apoptosis when expressed in the developing eye of Drosophila melanogaster. Genet. Mol. Res. 2003;2:43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hardie R.C., Franze K. Photomechanical responses in Drosophila photoreceptors. Science. 2012;338:260–263. doi: 10.1126/science.1222376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oberwinkler J., Stavenga D.G. Calcium imaging demonstrates colocalization of calcium influx and extrusion in fly photoreceptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:8578–8583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hardie R.C., Raghu P., Moore S., Juusola M., Baines R.A., Sweeney S.T. Calcium influx via TRP channels is required to maintain PIP2 levels in Drosophila photoreceptors. Neuron. 2001;30:149–159. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.