Abstract

Drosophila Dicer-2 efficiently and precisely produces 21-nucleotide (nt) siRNAs from long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) substrates and loads these siRNAs onto the effector protein Argonaute2 for RNA silencing. The functional roles of each domain of the multidomain Dicer-2 enzyme in the production and loading of siRNAs are not fully understood. Here we characterized Dicer-2 mutants lacking either the N-terminal helicase domain or the C-terminal dsRNA-binding domain (CdsRBD) (ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD, respectively) in vivo and in vitro. We found that ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 produces siRNAs with lowered efficiency and length fidelity, producing a smaller ratio of 21-nt siRNAs and higher ratios of 20- and 22-nt siRNAs in vivo and in vitro. We also found that ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 cannot load siRNA duplexes to Argonaute2 in vitro. Consistent with these findings, we found that ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 causes partial loss of RNA silencing activity in vivo. Thus, Dicer-2 CdsRBD is crucial for the efficiency and length fidelity in siRNA production and for siRNA loading. Together with our previously published findings, we propose that CdsRBD binds the proximal body region of a long dsRNA substrate whose 5′-monophosphate end is anchored by the phosphate-binding pocket in the PAZ domain. CdsRBD aligns the RNA to the RNA cleavage active site in the RNase III domain for efficient and high-fidelity siRNA production. This study reveals multifunctions of Dicer-2 CdsRBD and sheds light on the molecular mechanism by which Dicer-2 produces 21-nt siRNAs with a high efficiency and fidelity for efficient RNA silencing.

Keywords: Dicer, siRNA, dsRNA, RNA silencing, fidelity

INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are biologically important molecules that regulate gene expression. They are produced by the multidomain enzyme Dicer (Bernstein et al. 2001; Hutvagner et al. 2001; Ketting et al. 2001; Knight and Bass 2001). In human, both miRNAs and siRNAs are produced by the single Dicer (also called Dicer1 based on its sequence similarity to Drosophila Dicer-1). In contrast, in Drosophila, miRNAs and siRNAs are produced by two different Dicers; miRNAs are produced by Dicer-1 and siRNAs are produced by Dicer-2 (Lee et al. 2004). miRNAs are ∼22- to 24-nucleotides (nt) long produced from pre-miRNAs, whereas siRNAs are precisely 21 nt in length produced from long dsRNAs. Endogenous sources of long dsRNAs for siRNA production include viral RNAs, transposon RNAs, partially self-complementary hairpin RNAs, and convergent mRNAs (Czech et al. 2008; Ghildiyal et al. 2008; Kawamura et al. 2008; Okamura et al. 2008a,b). siRNAs function as a crucial antiviral and anti-transposon defense system in arthropods including Drosophila and other insects that transmit vector-borne diseases, as they lack acquired immunity (Bronkhorst and van Rij 2014; Fablet 2014; Karlikow et al. 2014; Wynant et al. 2014).

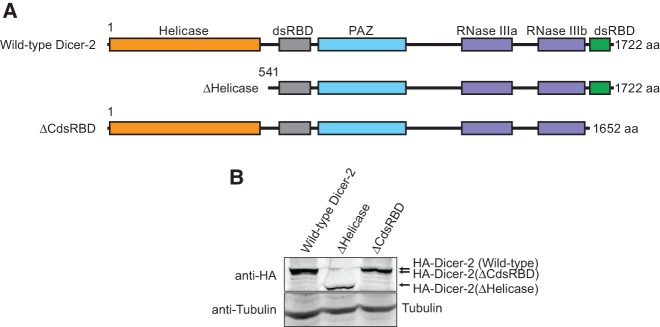

Drosophila Dicer-1 and Dicer-2 and human Dicer have a similar multidomain structure (Fig. 1A): an N-terminal helicase domain; a central, atypical dsRNA-binding domain (dsRBD, previously known as DUF283); a PAZ domain (named after Piwi, Argonaute, and Zwille); two RNase III domains; and a C-terminal dsRNA-binding domain (CdsRBD). The helicase domain of Drosophila Dicer-2, but not that of Drosophila Dicer-1 or human Dicer, binds and hydrolyzes ATP to translocate along long dsRNA substrates, allowing Dicer-2 to produce siRNAs processively from an end (Cenik et al. 2011; Welker et al. 2011; Sinha et al. 2015). The functions of CdsRBD are not well understood.

FIGURE 1.

Domain structures of Drosophila Dicer-2. (A) Domain structures of the wild-type and truncated mutant Drosophila Dicer-2 used in this study. (B) Anti-HA Western blot detecting the transgenic HA-Dicer-2 proteins in whole transgenic flies.

After their production, miRNAs and siRNAs are bound by Argonaute proteins, for which they act as sequence-specific guides. In Drosophila, the miRNA–Argonaute1 complexes repress mRNA translation and destabilize mRNA, while the siRNA–Argonaute2 complexes cleave their RNA targets. The difference in length between miRNAs (∼22–24 nt) and siRNAs (21 nt) in arthropods is important because the miRNA-effector protein Argonaute1 and the siRNA effector Argonaute2 preferentially bind ∼22- to 24-nt RNAs and 21-nt RNAs, respectively (Ameres et al. 2011). In fact, previous studies demonstrated that synthetic 21-nt siRNA duplexes are significantly more potent than synthetic 20- or 22-nt siRNA duplexes to silence a synthetic target mRNA in Drosophila embryo extract in vitro (Elbashir et al. 2001). Moreover, we recently reported that high-length fidelity in siRNA production by Dicer-2 is important for efficient RNA silencing activity in Drosophila (Kandasamy and Fukunaga 2016). These reports demonstrate the importance of the high-length fidelity in 21-nt siRNA production by Dicer-2.

How Dicer-2 efficiently and precisely produces siRNAs of exactly 21-nt length is unknown. Several models have been proposed to explain how Dicer enzymes define small RNA length (Zhang et al. 2004); the 3′ counting rule (MacRae et al. 2006, 2007), the 5′ counting rule (Park et al. 2011), and the loop counting rule (Gu et al. 2012). However, none of these studies explain how Drosophila Dicer-2, the unique Dicer enzyme dedicated for siRNA production, efficiently produces siRNAs of exactly 21-nt length with a remarkably high fidelity. We recently reported that recognition of the 5′ monophosphate of long dsRNA substrates by the unique phosphate-binding pocket in the Drosophila Dicer-2 PAZ domain is crucial for the high-length fidelity, but not the efficiency, in 21-nt siRNA production (Kandasamy and Fukunaga 2016). However, whether and how other domains of the multidomain Dicer-2 enzyme play roles in the efficiency and length fidelity in 21-nt siRNA production remains unknown.

In addition to the production of siRNAs, Dicer-2 also functions in the loading of siRNA duplexes to Argonatute2. Dicer-2 binds a partner protein R2D2 via its N-terminal helicase domain, and thus forms a RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex) loading complex (RLC) for siRNA loading (Liu et al. 2003; Hartig and Forstemann 2011). Whether and how other domains, especially CdsRBD, of Dicer-2 play roles in siRNA loading are unknown.

In this study, in order to examine the possible roles of CdsRBD of Dicer-2 in the efficient and high-fidelity production of siRNAs and loading of siRNAs, we characterized the Dicer-2 mutant lacking CdsRBD as well as the Dicer-2 mutant lacking the N-terminal helicase domain in vivo and in vitro. We found that CdsRBD is crucial for efficient and high-fidelity siRNA production and siRNA loading. Consistent with these findings, we found that CdsRBD is required for efficient RNA silencing activities in vivo.

RESULTS

Helicase domain and CdsRBD of Dicer-2 are crucial for efficient RNA silencing in vivo

To probe the roles of the N-terminal helicase domain and CdsRBD of Drosophila Dicer-2 in siRNA production, siRNA loading, and RNA silencing, we designed truncated Dicer-2 mutants, ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD (Fig. 1A). Full-length Dicer-2 is 1722 aa long. ΔHelicase (541–1722 aa) lacks the N-terminal 540 aa comprising the helicase domain, while ΔCdsRBD (1–1652 aa) lacks the C-terminal 70 aa comprising CdsRBD. We expressed these transgenic Dicer-2 proteins fused with an N-terminal HA tag in flies under a UAST promoter using the ubiquitous Act5C-Gal4 driver in the background of the endogenous dicer-2 null (dicer-2L811fsx = dicer-2null [Lee et al. 2004]). We also created the wild-type Dicer-2 rescue transgenic, as a positive control (Kandasamy and Fukunaga 2016). Expression of these transgenic Dicer-2 proteins was confirmed by Western blot (Fig. 1B)

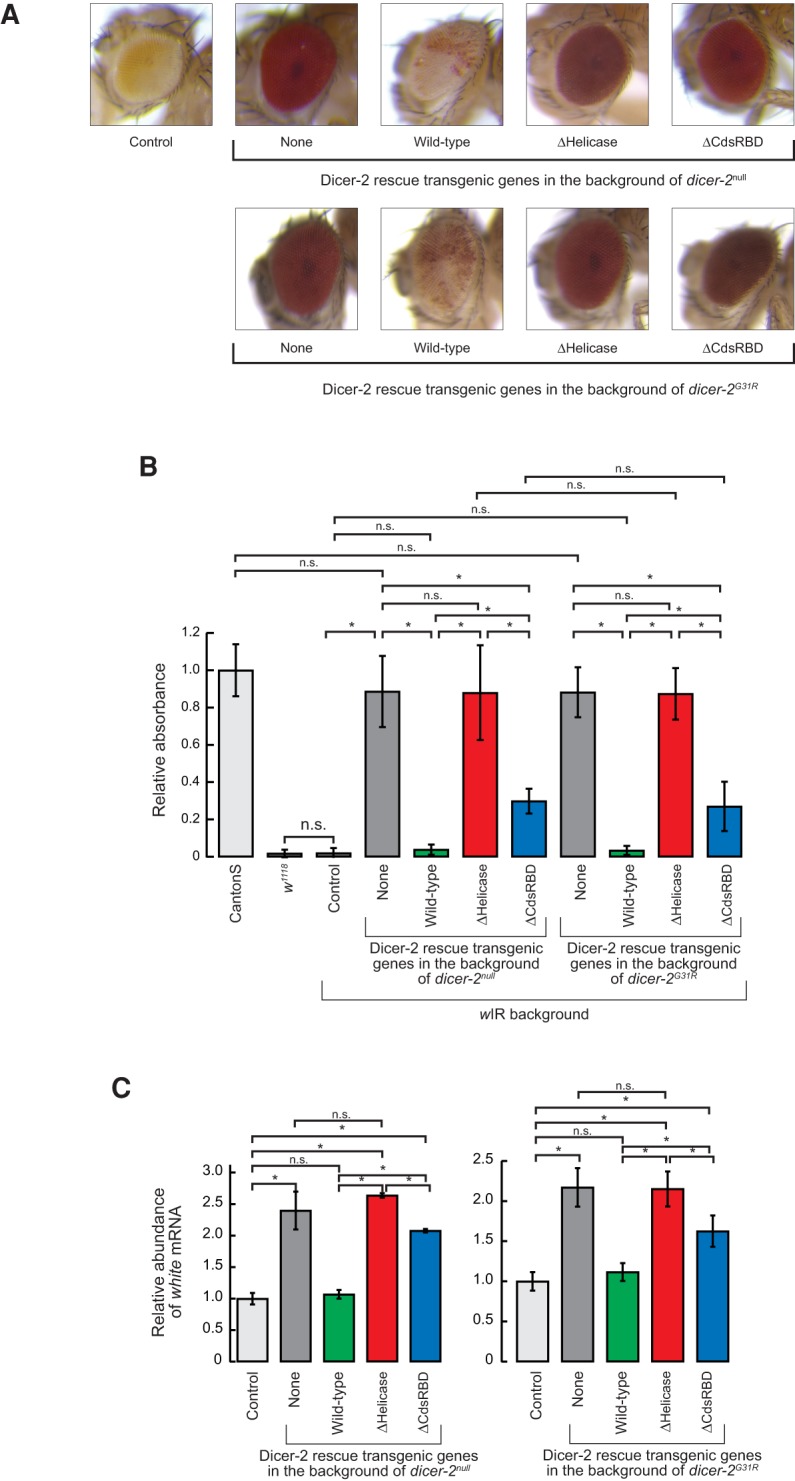

We found that RNA silencing activity is lost in ΔHelicase flies and lowered in ΔCdsRBD flies. We used the GMR-wIR (white inverted repeat) transgene reporter system (Lee and Carthew 2003) to assay in vivo siRNA production and RNA silencing. GMR-wIR generates an inverted repeat hairpin RNA encompassing white exon 3 sequence in eyes. Wild-type Dicer-2 processes the wIR hairpin with high fidelity into 21-nt siRNAs, which in turn silence expression of the white gene encoding an ABC transporter essential for the entry of red pigment precursor into cells, resulting in white or light orange eyes instead of red eyes. Control flies containing wild-type endogenous dicer-2 had light orange eyes, showing that they have high RNA silencing activity (Fig. 2A). In contrast, dicer-2null flies had red eyes, showing that the RNA silencing activity is lost in dicer-2null flies. The RNA silencing activity in dicer-2null flies was rescued by the wild-type Dicer-2 transgene as expected (Fig. 2A). Using this eye color-based RNA silencing assay system, we examined how truncation of the helicase domain and CdsRBD in Dicer-2 affects RNA silencing in vivo. We found that ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD flies had red eyes, showing that the RNA silencing activity is lost or lowered in these flies (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

N-terminal helicase domain and C-terminal dsRBD of Dicer-2 are important for efficient RNA silencing in vivo. (A) Images of the eyes of the female wild-type and mutant Dicer-2 rescue transgenic flies in the background of the endogenous dicer-2null or dicer-2G31R in the presence of white inverted repeat (wIR). (Top) wIR; dicer-2null, Act5C-Gal4/dicer-2null; UAST-HA-Dicer-2 (wild-type or mutant)/+. (Bottom) wIR; dicer-2null, Act5C-Gal4/dicer-2G31R; UAST-HA-Dicer-2 (wild-type or mutant)/+. Control flies are wIR; dicer-2null, Act5C-Gal4/CyO; +. (B) Measurement of eye pigment chemically extracted from hand-dissected fly eyes. Of note, 480-nm absorbance normalized to mean of CantonS samples was shown. Data are mean ± SD (n = 5). (*) P-value <0.05. (C) Levels of white mRNA normalized by rp49 in the flies with dicer-2null or dicer-2G31R background relative to the mean of the control flies, determined by qRT-PCR. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). (*) P-value <0.05. Data for the control, dicer-2null, and wild-type rescue are from Kandasamy and Fukunaga (2016).

By quantitating the RNA silencing activity, we found that the RNA silencing activity is completely lost in ΔHelicase and is significantly lowered in ΔCdsRBD flies. In order to quantitate the RNA silencing activity, we chemically extracted red eye pigment from fly eyes and measured their absorbance. The control flies that have endogenous wild-type dicer-2 had only very low absorbance compared to Canton S flies that do not have the wIR transgene and thus have red eyes, showing that the control flies have high RNA silencing activity (Fig. 2B). dicer-2null flies exhibited significantly higher absorbance, as high as the Canton S red eye control, showing that dicer-2null flies completely lack the RNA silencing activity. Wild-type Dicer-2 transgene rescue flies had very low absorbance, revealing that the RNA silencing activity was fully rescued. ΔHelicase flies had absorbance values as high as dicer-2null flies, revealing that the RNA silencing activity was not rescued at all. In contrast, ΔCdsRBD flies exhibited moderately increased absorbance, which was statistically significantly higher compared to the control and wild-type Dicer-2 rescue flies, but was lower compared to dicer-2null and ΔHelicase flies. These results revealed that the RNA silencing activity is significantly lowered but not completely lost in ΔCdsRBD flies. Expressing ΔHelicase or ΔCdsRBD mutant Dicer-2 in the flies with endogenous wild-type dicer-2 background did not reduce the RNA silencing activity (Supplemental Fig. S1), revealing that these mutant Dicer-2 do not exhibit detectable dominant negative effects on the RNA silencing activity.

Quantitation of the level of white mRNA in flies by qRT-PCR also showed that the RNA silencing activity is completely lost in ΔHelicase flies and significantly lowered in ΔCdsRBD flies. dicer-2null flies had significantly higher levels of white mRNA than the control flies (Fig. 2C; Kandasamy and Fukunaga 2016). Wild-type Dicer-2 rescue flies had low levels of white mRNA, which was not significantly different from those in the control flies. ΔHelicase flies exhibited high levels of white mRNA as dicer-2null flies (Fig. 2C). ΔCdsRBD flies exhibited moderately higher levels of white mRNA; significantly higher than wild-type Dicer-2 rescue flies but lower than ΔHelicase flies. We concluded that the RNA silencing activity is completely lost in ΔHelicase flies and significantly lowered in ΔCdsRBD flies. These results indicate that the helicase domain and CdsRBD are essential and important, respectively, for the RNA silencing activity in vivo.

The loss of the RNA silencing activity in ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD flies is at least partly due to defects in siRNA production. Besides siRNA production, Dicer-2 also transfers siRNAs to Argonaute2 by binding to R2D2 via its N-terminal helicase domain (Liu et al. 2003; Hartig and Forstemann 2011). ATP-binding mutant Dicer-2 (Dicer-2G31R) retains the ability to transfer siRNAs to Argonaute2, whereas it cannot produce siRNAs (Lee et al. 2004; Forstemann et al. 2007; Cenik et al. 2011; Fukunaga et al. 2014). To test whether the RNA silencing deficiency in ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD flies is at least partly due to defects in siRNA production, we performed the same eye color assay as above, but this time, in the background of endogenous ATP-binding mutant dicer-2 (dicer-2G31R) (Lee et al. 2004), instead of dicer-2null. If the loss of the RNA silencing activity in ΔHelicase or ΔCdsRBD flies was solely due to defects in siRNA loading to Argonaute2, but not due to defects in siRNA production, then coexpression of ATP-binding mutant dicer-2 (dicer-2G31R) and transgenic ΔHelicase or ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 would rescue the RNA silencing activity. We found that this was not the case. The eye colors of ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD flies in the background of endogenous ATP-binding mutant dicer-2 (dicer-2G31R) were red, similar to those in the background of dicer-2null (Fig. 2A). The absorbance of the chemically extracted red eye pigment was similar to those in the background of dicer-2null (Fig. 2B). The quantitation of the levels of white mRNA by qRT-PCR also produced similar results to those in the background of dicer-2null (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that the RNA silencing deficiency in ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD flies is at least partly due to defects in the production of siRNAs.

Helicase domain is required for siRNA production and CdsRBD is important for efficient and high-fidelity siRNA production in vivo

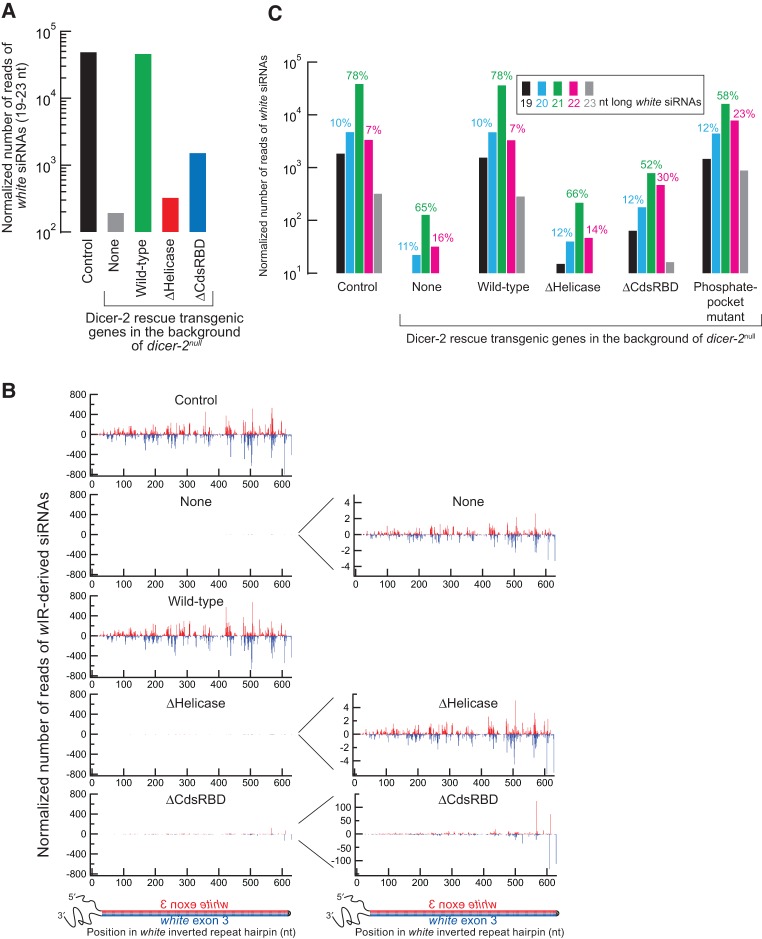

We found that siRNA production is completely lost in ΔHelicase and is lowered in ΔCdsRBD flies. In order to test directly the hypothesis that ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD flies have defects in siRNA production, we high-throughput sequenced small RNA libraries prepared from hand-dissected heads (Supplemental Table S1). The wIR-derived 19- to 23-nt siRNAs were highly observed in the control flies and their abundance (normalized by the total non-rRNA-mapping reads, a majority of which are miRNA reads) was severely reduced in dicer-2null flies, as expected (Fig. 3A; Kandasamy and Fukunaga 2016). The siRNAs were produced from the entire hairpin of wIR RNA (Fig. 3B; Kandasamy and Fukunaga 2016). The siRNA abundance was rescued in wild-type Dicer-2 rescue flies (Fig. 3A,B; Kandasamy and Fukunaga 2016). In contrast, the siRNA abundance was not rescued in ΔHelicase flies, exhibiting background levels similar to dicer-2null flies, revealing that ΔHelicase Dicer-2 cannot produce siRNAs in vivo. This finding is consistent with their complete loss of RNA silencing activity in vivo (Fig. 2). In contrast, in ΔCdsRBD flies, the siRNA abundance was severely reduced but was higher than the background level (1.5% of the wild-type level after subtraction of the background level observed in dicer-2null flies) (Fig. 3A,B), revealing that ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 has lowered activity to produce siRNAs in vivo. This finding is consistent with their partial loss of the RNA silencing activity in vivo (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 3.

C-terminal dsRBD of Dicer-2 is important for high-fidelity 21-nt siRNA production in vivo. Sequencing results of small RNAs prepared from female fly heads are shown. The reads were normalized by the sequencing depth. (A) Normalized number of reads of 19- to 23-nt wIR-derived siRNAs. (B) Abundance and 5′ position of wIR-derived siRNAs. Antisense siRNAs are shown in red, sense in blue. Graphs on the right have different y-axis scales. (C) Length distribution of wIR-derived siRNAs. Data for the control, dicer-2null, wild-type rescue, phosphate-binding pocket mutant are from Kandasamy and Fukunaga (2016).

We found that ΔCdsRBD flies produce siRNAs with increased length heterogeneity, meaning that they have lowered length fidelity in 21-nt siRNA production. In order to examine whether and how CdsRBD truncation affected length fidelity in siRNA production, we analyzed length heterogeneity of wIR-derived siRNAs. In both the control and wild-type Dicer-2 rescue flies, most of the wIR-derived siRNAs were 21 nt, comprising 78% of all the wIR-derived reads, while only 10% and 7% were 20 and 22 nt, respectively (Fig. 3C; Kandasamy and Fukunaga 2016), showing high fidelity in 21-nt siRNA production by wild-type Dicer-2. Please note that the graphs in Figure 3A and C are shown in a log scale. We noticed that the background wIR-derived reads observed in dicer-2null and ΔHelicase flies, which are more than two orders of magnitude fewer than the authentic siRNA reads in the control and wild-type Dicer-2 rescue flies, also showed a peak at 21 nt (Fig. 3C). We speculate that these low abundance, background reads were likely derived from nonspecific wIR RNA degradation. We speculate that nonspecific degradation of wIR RNA hairpin produces random sized RNA products and among them 21-nt products were preferentially bound by Argonaute2 and stabilized resulting as a peak at 21 nt in the length distribution. Supporting this speculation, the previous study showed that single-stranded RNAs that have a similar length to authentic small silencing RNAs can be loaded to Argonaute proteins albeit with a much lower efficiency compared with authentic small RNA duplexes (Okamura et al. 2013). Interestingly, the length distribution of wIR-derived siRNAs in ΔCdsRBD flies was distinct from those of the background level reads or those of the authentic wIR-derived siRNAs in the control and wild-type Dicer-2 rescue flies. In ΔCdsRBD flies, the ratio of the 21-nt wIR-derived siRNAs was reduced (52%), whereas those of 20 and 22 nt were increased (12% and 30%, respectively), compared with the other flies (Fig. 3C). These results showed that the length fidelity in siRNA production in ΔCdsRBD flies was lowered. The lowered length fidelity in 21 nt siRNA production observed in ΔCdsRBD flies is similar to that observed in the phosphate-binding pocket mutant Dicer-2 (H743A, R752A, R759A, R943A, and R956A) flies that we reported recently (Fig. 3C; Kandasamy and Fukunaga 2016). In the phosphate-binding pocket mutant Dicer-2 flies, the ratio of the 21-nt wIR-derived siRNAs was reduced (58%), whereas those of 20 and 22 nt were increased (12% and 23%, respectively). We concluded that ΔCdsRBD flies produced siRNAs with lower efficiency and lower length fidelity and therefore that CdsRBD of Dicer-2 is important for efficient and high-fidelity siRNA production in vivo. The decrease in both efficiency and fidelity in siRNA production likely underlies, at least partly, the lowered RNA silencing activity in ΔCdsRBD flies (Fig. 2).

ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD flies show no change in miRNA abundance and length

ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD flies showed no change in miRNA abundance and length, and therefore, transgenic expression of ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 does not alter miRNA production in vivo. In previous studies, we found that recombinant wild-type Dicer-2 cleaves pre-miRNAs in vitro into small RNAs that are shorter than authentic miRNAs produced by Dicer-1, although such miscleavage does not occur in fly ovaries in vivo (Cenik et al. 2011; Fukunaga and Zamore 2014; Fukunaga et al. 2014). We wondered whether ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 lost substrate specificity and cleave pre-miRNAs into miRNAs with altered length compared with authentic miRNAs produced by Dicer-1 in vivo. To test this possibility, we analyzed the abundance and mean length of each miRNA in the small RNA libraries prepared from fly heads. Neither abundance nor length of miRNAs was altered in dicer-2null compared with the control flies (top panels in Supplemental Fig. S2A,B), showing that the loss of endogenous Dicer-2 does not affect the abundance or length of miRNAs in heads, consistent with our previous findings from ovaries (Fukunaga et al. 2014). As expected, wild-type Dicer-2 rescue flies did not show any change in the abundance or length of miRNAs compared to dicer-2null (second panels in Supplemental Fig. S2A,B). Similarly, neither ΔHelicase nor ΔCdsRBD flies exhibited a change in the abundance or length of miRNAs compared with dicer-2null (third and fourth panels in Supplemental Fig. S2A,B). Therefore, we concluded that transgenic expression of ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 does not alter miRNA production in vivo.

CdsRBD, but not helicase domain, is crucial for high-fidelity siRNA production in vitro

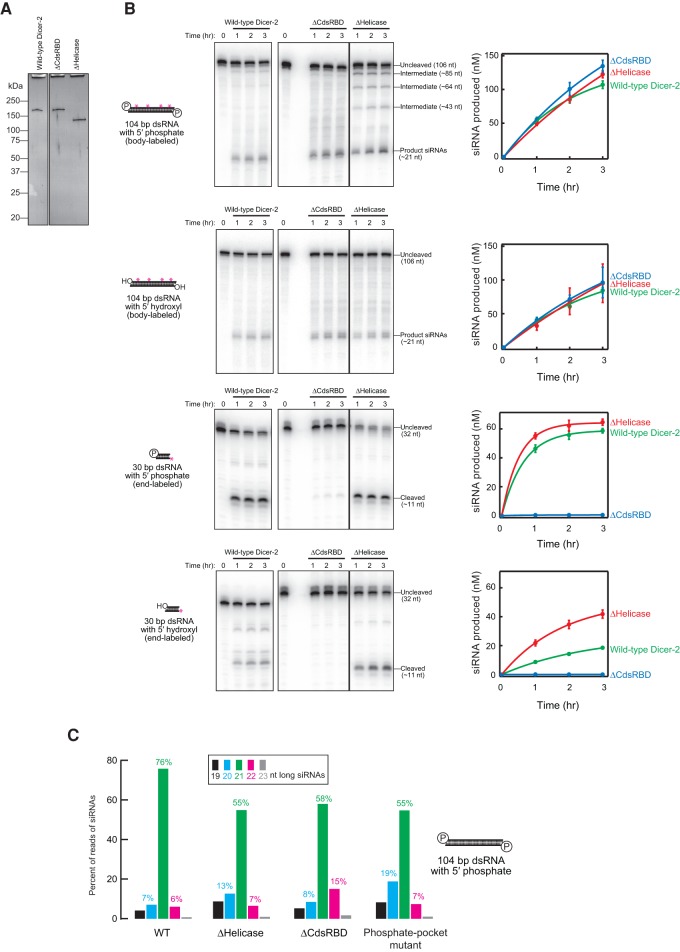

In order to directly test whether ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 lost the high fidelity required to produce 21-nt siRNAs precisely, we performed in vitro RNA processing assay using recombinant Dicer-2 proteins (Fig. 4A). Before analyzing the length heterogeneity of siRNAs produced, we first analyzed the efficiency in siRNA production. Both ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 exhibited similar processing efficiency for 5′ monophosphate and 5′ hydroxyl long (104 bp) dsRNA substrates compared to wild-type Dicer-2 (Fig. 4B). However, more intermediate products were observed during the processing of 5′ monophosphate, 104-bp dsRNA by ΔHelicase Dicer-2, while the wild-type and ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 did not detectably produce such intermediate products. Thus, ΔHelicase Dicer-2 processes the dsRNA in a distributive manner while wild-type and ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 process the dsRNA in a processive manner. This finding is consistent with the previous studies reporting that wild-type Dicer-2 translocates on a long dsRNA and thus produces siRNAs in a processive manner and that ATP and the ATPase activity of the helicase domain of Dicer-2 are required for the processive siRNA production (Cenik et al. 2011; Welker et al. 2011).

FIGURE 4.

C-terminal dsRBD of Dicer-2 is important for high-fidelity 21-nt siRNA production by purified recombinant proteins in vitro. (A) Silver-staining of the purified recombinant proteins (28 ng) run on a SDS–PAGE gel. (B) In vitro dicing assay using the purified recombinant proteins. As long dsRNA, body-labeled 104-bp dsRNAs with 2-nt 3′ overhang and either 5′ monophosphate or 5′ hydroxyl were tested. As short dsRNA, 5′ labeled 30-bp dsRNAs with 2-nt 3′ overhang and either 5′ monophosphate or 5′ hydroxyl were tested. The other end of the 30-bp dsRNAs was blocked by two deoxynucleotides (Cenik et al. 2011). Representative gel images (left panels) and quantification of the signals (right panels) are shown. Data are mean ± SD for three independent trials. (C) Length distribution of siRNAs produced from 104-bp dsRNA with 2-nt 3′ overhang and 5′ monophosphate by recombinant Dicer-2 proteins in test tube revealed by high-throughput sequencing. Data for the wild-type and phosphate-binding pocket mutant are from Kandasamy and Fukunaga (2016).

ΔHelicase Dicer-2 showed similar and higher processing efficiencies for 5′ monophosphate and 5′ hydroxyl short (30 bp) dsRNA substrates, respectively, compared to wild-type Dicer-2. In contrast, ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 exhibited almost complete loss of the activities to process these short (30 bp) dsRNA substrates. These results showed that the helicase domain is dispensable for efficient dsRNA processing in vitro by the recombinant proteins and that CdsRBD is dispensable for efficient long dsRNA processing, while it is essential for short dsRNA processing.

We found that CdsRBD ensures high-fidelity production of 21-nt siRNA in vitro. In order to examine the length fidelity in siRNA production by ΔHelicase and ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2, we prepared and sequenced libraries of the small RNAs produced in vitro from the 104-bp dsRNA with 5′ monophosphate ends by the recombinant Dicer-2 proteins (Supplemental Table S2). Consistent with our in vivo findings that siRNAs in ΔCdsRBD flies have increased length heterogeneity (Fig. 3), we found that siRNAs produced by recombinant ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 in vitro showed increased length heterogeneity (Fig. 4C). ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 produced fewer 21-nt siRNAs and higher numbers of 20 and 22 nt siRNAs than wild-type Dicer-2 in vitro (Fig. 4C). As high as 76% of siRNAs produced by wild-type Dicer-2 were 21 nt, while only 7% and 6% were 20 and 22 nt, respectively (Fig. 4C; Kandasamy and Fukunaga 2016). In contrast, only 58% of siRNAs produced by ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 were 21 nt, whereas the ratios of 20 and 22 nt were increased to 8% and 15%, respectively. Thus, ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 lost the high fidelity to produce 21-nt siRNAs in vitro. Similarly, the increase of the length heterogeneity was also observed previously in the siRNAs produced by phosphate-binding pocket mutant Dicer-2 in vitro (Fig. 4C; Kandasamy and Fukunaga 2016).

Higher production of the longer, 22-nt siRNAs by ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 compared to wild-type Dicer-2 was especially notable both in vivo (Fig. 3C) and in vitro (Fig. 4C). Thus, ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 lost the high fidelity to produce 21-nt siRNAs both in vivo and in vitro. We concluded that CdsRBD is crucial for high fidelity in 21-nt siRNA production.

Similar to ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 and phosphate-binding pocket mutant Dicer-2, ΔHelicase Dicer-2 also produced siRNAs with increased length heterogeneity in vitro compared to wild-type Dicer-2 (Fig. 4C). Only 55% of siRNAs produced by ΔHelicase Dicer-2 were 21 nt, while the ratios of 20 and 22 nt were 13% and 7%, respectively. This in vitro finding supports the idea that, like ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 and the phosphate-binding pocket mutant Dicer-2, ΔHelicase Dicer-2 also lost the high fidelity in siRNA production. However, since this ΔHelicase mutant cannot produce siRNAs above the background level in vivo (Fig. 3), the physiological relevance of this in vitro finding remains currently unknown.

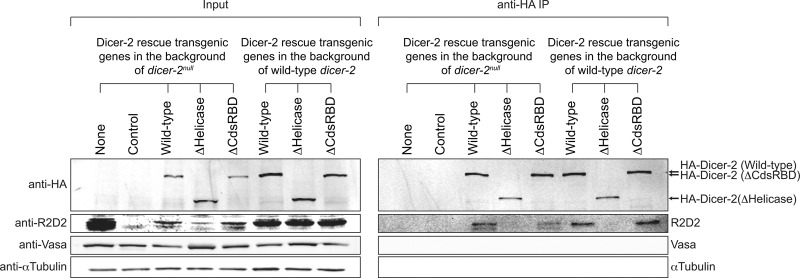

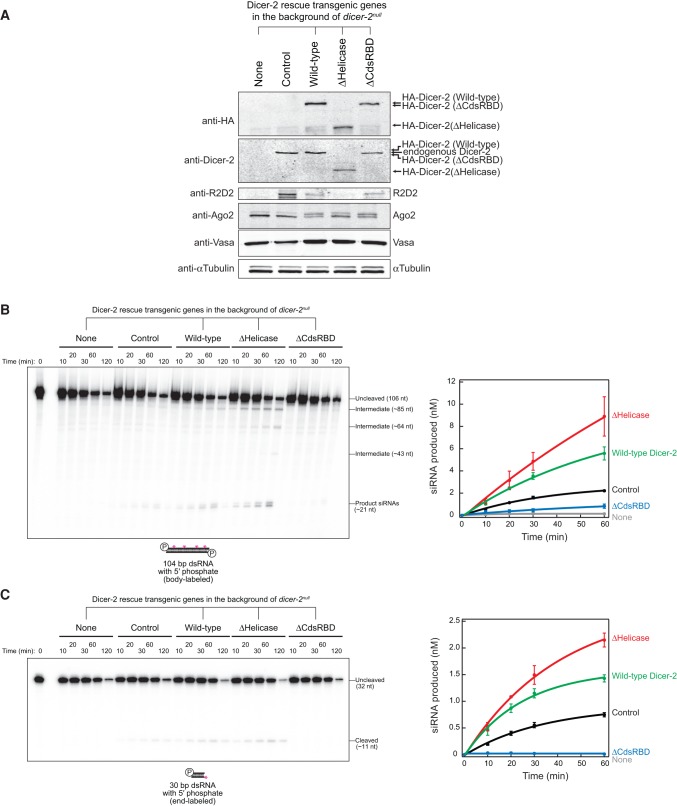

Helicase domain, but not CdsRBD, is crucial for binding with R2D2

Next, we tested whether the helicase domain and CdsRBD of Dicer-2 are crucial for the interaction with R2D2 in vivo. We performed anti-HA immunoprecipitation of the HA-tagged transgenic Dicer-2 proteins using ovary lysates of the control flies, dicer-2null flies, wild-type Dicer-2 rescue flies, ΔHelicase flies, and ΔCdsRBD flies (Fig. 5). Vasa and αTubulin, which do not bind Dicer-2, served as loading controls in the inputs and as negative controls for coimmunoprecipitation. R2D2 was coimmunoprecipitated similarly between the wild-type Dicer-2 rescue ovary lysate and ΔCdsRBD ovary lysate, revealing that CdsRBD is dispensable for the binding with R2D2. The R2D2 level was severely reduced in the ΔHelicase input ovary lysate (as in the dicer-2null input ovary lysate), and R2D2 was not detected in the immunoprecipitation fraction of ΔHelicase. The previous studies showed that the binding between Dicer-2 and R2D2 is crucial for the stability of R2D2 (Liu et al. 2003) and that ΔHelicase Dicer-2 cannot bind R2D2 in S2 cells (Hartig and Forstemann 2011). Thus, our results indicated that ΔHelicase Dicer-2 cannot bind R2D2 in vivo either. To test this idea further, we performed the same anti-HA immunoprecipitation using ovary lysates expressing the HA-tagged transgenic wild-type, ΔHelicase, and ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 proteins in the background of the wild-type dicer-2, in which R2D2 was stably present (Fig. 5). Again, R2D2 was coimmunoprecipitated with the HA-tagged transgenic wild-type and ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2, but not with ΔHelicase Dicer-2. Therefore, we concluded that the wild-type and ΔCdsRBD, but not ΔHelicase, Dicer-2 can bind R2D2, revealing that the helicase domain, but not CdsRBD, is crucial for the binding with R2D2 in vivo.

FIGURE 5.

N-terminal helicase domain, but not C-terminal dsRBD, of Dicer-2 is crucial for interaction with R2D2. HA-tagged transgenic Dicer-2 proteins in ovary lysate were immunoprecipitated by anti-HA beads and the copurified proteins were examined by Western blotting. αTubulin and Vasa served as loading controls and were not coimmunoprecipitated with HA-Dicer-2 proteins. The results were reproduced with three biologically replicated samples and representative images are shown.

CdsRBD, but not helicase domain, is crucial for efficient siRNA production in ovary lysate in vitro

Next, we tested processing of long (104 bp) and short (30 bp) dsRNAs with 5′ monophosphate ends into siRNAs in ovary lysates of the control flies, dicer-2null flies, wild-type Dicer-2 rescue flies, ΔHelicase flies, and ΔCdsRBD flies in vitro. First, we confirmed protein expression in the ovary lysates used in this assay by Western blotting (Fig. 6A). Anti-Dicer-2 Western revealed that the levels of our transgenic proteins were comparable to that of the endogenous Dicer-2. The control ovary lysate containing the endogenous wild-type dicer-2, but not the dicer-2null ovary lysate, exhibited processing of both 104 bp and 30 bp dsRNA substrates into siRNAs as expected (Fig. 6B,C). The wild-type Dicer-2 rescue ovary lysate showed efficient processing of these dsRNAs. ΔHelicase ovary lysate also exhibited efficient processing of both dsRNAs, consistent with the assay results using the purified recombinant proteins (Fig. 4B). ΔHelicase ovary lysate produced more intermediates substrates from 104-bp dsRNA (Fig. 6B), again consistent with the recombinant protein assay results (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 6.

C-terminal dsRBD, but not N-terminal helicase domain, of Dicer-2 is important for siRNA production in ovary lysate in vitro. (A) Western blotting of the ovary lysates used in the in vitro assays in Figures 6 and 7. Anti-HA antibody detects HA-tagged transgenic Dicer-2 proteins, while anti-Dicer-2 antibody detects the transgenic proteins and the endogenous wild-type Dicer-2. αTubulin and Vasa served as loading controls. (B,C) In vitro dicing assay using the fly ovary lysates. (B) Body-labeled 104-bp dsRNA with 2-nt 3′ overhang and 5′ monophosphate and (C) 5′ labeled 30-bp dsRNAs with 2-nt 3′ overhang and 5′ monophosphate were tested. The other end of the 30-bp dsRNA was blocked by two deoxynucleotides (Cenik et al. 2011). Representative gel images (left panels) and quantification of the signals (right panels). Plotted until the 60-min time points (since at 120 min, significant nonspecific degradation of the substrates were observed) are shown. Data are mean ± SD for three independent trials.

ΔCdsRBD ovary lysate showed severely reduced but above the background level (in the dicer-2null ovary lysate) processing of 104-bp dsRNA (Fig. 6B), consistent with the siRNA levels in ΔCdsRBD flies in vivo (Fig. 3). In contrast, ΔCdsRBD ovary lysate showed no detectable activity to process 30 bp dsRNA (Fig. 6C).

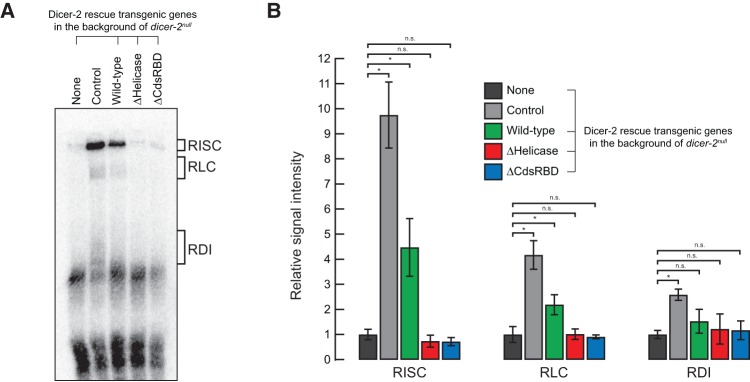

Helicase domain and CdsRBD are crucial for siRNA loading to Argonaute2 in ovary lysate in vitro

Finally, in order to test whether the helicase domain and CdsRBD of Dicer-2 play roles in siRNA loading to Argonaute2, we tested the siRNA loading activity in the ovary lysates (the same lysates as used in Fig. 6) in vitro using a radiolabeled synthetic siRNA duplex. The levels of Argonaute2 protein were similar among the ovary lysates (Fig. 6). Similar to the control ovary lysate, the wild-type Dicer-2 rescue ovary lysate formed RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex, composed of Argonaute2 bound with siRNA) and RLC (RISC-loading complex, composed of Dicer-2 and R2D2 bound with siRNA), while the dicer-2null ovary lysate could not (Fig. 7). In contrast, neither ΔHelicase nor ΔCdsRBD ovary lysate detectably formed RISC and RLC. Therefore, we concluded that both the helicase domain and CdsRBD are required for siRNA loading to Argonaute2. The helicase domain of Dicer-2 was required for the binding with R2D2 (Fig. 5; Hartig and Forstemann 2011), which is a component of RLC (Liu et al. 2003). Therefore, loss of the binding with R2D2 is at least one of the reasons why ΔHelicase Dicer-2 cannot load siRNA to Argonaute2. In contrast, since ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 could bind R2D2 (Fig. 5), its loss of the siRNA loading activity suggests a direct role of CdsRBD in the siRNA loading process.

FIGURE 7.

Both N-terminal helicase domain and C-terminal dsRBD of Dicer-2 are important for siRNA loading to Argonaute2 in ovary lysate in vitro. (A) Representative gel image of in vitro siRNA loading assay using ovary lysate. (B) Quantification of the signals in the gels normalized to the background signals in the ovary lysate of dicer-2null without any rescue gene (negative control). Data are mean ± SD for four independent trials. (*) P-value <0.05.

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that the N-terminal helicase domain of Dicer-2 is crucial for efficient RNA silencing in vivo (Fig. 2), efficient siRNA production in vivo (Fig. 3), high-fidelity and processive siRNA production by the recombinant protein in vitro (Fig. 4), interaction with R2D2 (Fig. 5), processive siRNA production in ovary lysate in vitro (Fig. 6), and siRNA loading to Argonaute2 in ovary lysate in vitro (Fig. 7). The helicase domain was dispensable for efficient siRNA production by the recombinant protein in vitro (Fig. 4) and in ovary lysate in vitro (Fig. 6), while it was required for siRNA production in vivo (Fig. 2).

These findings may suggest unknown mechanism(s) and/or factor(s) present in vivo but missing in our in vitro conditions that prevent ΔHelicase Dicer-2 from producing siRNAs. For example, the N-terminal region of Dicer-2 containing the helicase domain is required and sufficient for the localization of Dicer-2 to the cytoplasmic granules called D2 bodies together with R2D2 in S2 cells (Nishida et al. 2013). The D2 bodies promote correct loading of siRNAs to Argonaute2 and prevent their misloading to Argonaute1 (Nishida et al. 2013). Although it is unknown whether D2 bodies exist in flies in vivo and whether they are required for efficient siRNA production, it is interesting to speculate that ΔHelicase Dicer-2 cannot efficiently produce siRNAs in vivo because it cannot be localized to D2 bodies.

The complete loss of RNA silencing in ΔHelicase flies in the background of dicer-2null (Fig. 2) can be explained by both loss of siRNA production (in vivo) and loss of siRNA loading by ΔHelicase Dicer-2. The complete loss of RNA silencing in ΔHelicase flies in the background of dicer-2G31R (Fig. 2) can be explained by the loss of siRNA production (in vivo) by ΔHelicase Dicer-2.

The mouse physiological DicerO isoform that is produced using an alternative transcription start site in oocytes and lacks the N-terminal helicase domain (=ΔHelicase) has higher activity to produce siRNAs than the full-length Dicer, enabling high RNA silencing activity in oocytes (Flemr et al. 2013). Human ΔHelicase Dicer has higher processing activity for short (35 bp) dsRNA than wild-type human Dicer in vitro, while its processing activity for pre-miRNA was unaltered (Ma et al. 2008). Also, human ΔHelicase Dicer has higher activity to produce siRNAs derived from long dsRNAs (257 bp dsRNA) and viruses resulting in higher RNA silencing activity against reporters and viruses than wild-type human Dicer in human 293T cells without a change in the activity to produce miRNAs from pre-miRNAs (Kennedy et al. 2015). These results suggest an inhibitory role of the mammalian Dicer helicase domains. In contrast, truncation of the helicase domain of Drosophila Dicer-1 reduced its activity to cleave pre-miRNAs into miRNAs in vitro (Ye et al. 2007; Tsutsumi et al. 2011). Thus, helicase domains of different Dicer proteins may have distinct regulatory roles, which warrant future studies.

Our study showed that CdsRBD of Dicer-2 is crucial for efficient RNA silencing in vivo (Fig. 2), efficient and high-fidelity siRNA production in vivo (Fig. 3), high fidelity siRNA production from long dsRNA and efficient siRNA production from short dsRNAs by the recombinant protein in vitro (Fig. 4), efficient siRNA production in ovary lysate in vitro (Fig. 6), and siRNA loading to Argonaute2 in ovary lysate in vitro (Fig. 7). CdsRBD was dispensable for efficient siRNA production from long dsRNAs by the recombinant protein in vitro (Fig. 4B), while it was crucial for efficient siRNA production from the same long dsRNA substrate in ovary lysate in vitro (Fig. 6B) and for efficient siRNA production in vivo (Fig. 2). These findings may suggest unknown mechanism(s) and/or factor(s) present in vivo and in ovary lysate but missing in our in vitro recombinant protein assay that prevents ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 from producing siRNAs from long dsRNAs. The partial loss of the RNA silencing activity in ΔCdsRBD flies in the background of dicer-2null (Fig. 2) can be explained by the loss of efficient and high-fidelity siRNA production (in vivo) and loss of siRNA loading by ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2. The partial loss of the RNA silencing activity in ΔCdsRBD flies in the background of dicer-2G31R (Fig. 2) can be explained by the loss of efficient and high-fidelity siRNA production (in vivo) by ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2. Similar to our findings, a human Dicer truncated mutant lacking CdsRBD (ΔCdsRBD) has lower processing rates for short substrate dsRNAs (35-bp dsRNA and pre-miRNA) than wild-type Dicer in vitro (Ma et al. 2008). Isolated CdsRBD of human Dicer binds pre-miRNAs and short and long (12, 16, 22, 33, 44, and 500 bp) dsRNAs, suggesting that CdsRBD contributes directly to substrate RNA binding (Provost et al. 2002; Wostenberg et al. 2012).

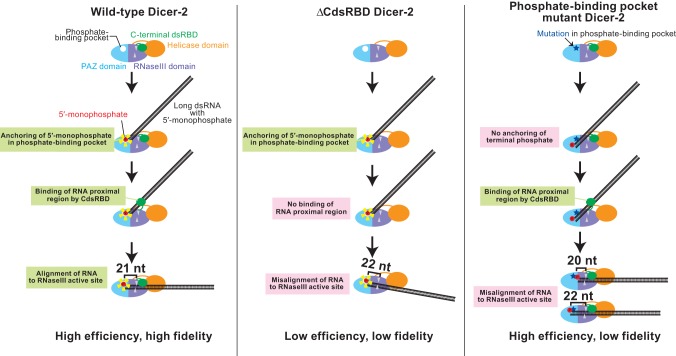

Based on the findings in this and our recent studies (Kandasamy and Fukunaga 2016), we propose the following model by which Drosophila Dicer-2 CdsRBD plays crucial roles in the efficient and high-fidelity production of 21-nt siRNA (Fig. 8). The phosphate-binding pocket in the PAZ domain binds the 5′ monophosphate of a long dsRNA substrate, thereby anchoring the end of the RNA substrate (Kandasamy and Fukunaga 2016). At this initial binding stage, the proximal body region of the RNA substrate does not interact with Dicer-2 and therefore is not aligned with Dicer-2. Upon binding of CdsRBD to the proximal body region of the long dsRNA substrate, the RNA is now aligned to the RNase III active site in the RNase III domain. The distance between the phosphate-binding pocket and the RNase III active site corresponds to that of the 21-nt pitch in the A-form dsRNA duplex. By this mechanism, Dicer-2 precisely measures the length of siRNAs, ensuring high-length fidelity in 21-nt siRNA production. During the processive production of multiple siRNAs from a single long dsRNA substrate, Dicer-2 repeatedly uses this 5′ monophosphate-anchoring and body-alignment mechanism to ensure high-fidelity 21-nt siRNA production as it translocates along the length of the dsRNA. This model aligns well with the structural model of Drosophila Dicer-2 determined by electron microscopy (Lau et al. 2012). This model is also consistent with the structural studies of human Dicer that revealed its structural rearrangement between nonproductive and productive conformations (Taylor et al. 2013). Considering our findings that ΔHelicase also exhibited lower-fidelity production of siRNAs in vitro (Fig. 4C), the helicase domain may also function to ensure high fidelity in siRNA production, probably by binding the proximal body region of the RNA and by aligning the RNA to the RNase III active site, together with CdsRBD. However, currently we do not have supporting in vivo data to include the roles of the helicase domain in our model.

FIGURE 8.

Models for efficient and high-fidelity siRNA production by Dicer-2. The phosphate-binding pocket in the Dicer-2 PAZ domain anchors the 5′ monophosphate of long dsRNA. Then C-terminal dsRBD binds the proximal body region of the long dsRNA and aligns the RNA to the RNase III active sites. The distance between the anchoring phosphate-binding pocket and RNase III active sites correspond to 21-nt length, allowing high-fidelity 21-nt siRNA production. In the absence of C-terminal dsRBD, dsRNA is misaligned, resulting in lower-efficiency and lower-fidelity production of siRNAs. In the absence of the phosphate-binding pocket, the RNA terminal end is not properly anchored, resulting in lower-fidelity production of siRNAs. The models align well with the previous structural model of Dicer-2 (Lau et al. 2012).

Our model can explain why ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2 exhibits lowered efficiency and length fidelity in siRNA production. In ΔCdsRBD Dicer-2, after anchoring the 5′ monophosphate in the phosphate-binding pocket, the RNA body region is misaligned in the RNase III domains due to the lack of the interaction between CdsRBD and the body region of the RNA. RNAs that are largely misaligned render their bodies inaccessible to RNase III active sites for cleavage. The observed reduced siRNA production in ΔCdsRBD flies in vivo (Fig. 3) and in ovary lysate in vitro (Fig. 6) can be explained by the loss of the proper alignment of dsRNA substrates to the RNase III active site, leaving most of the RNA substrates uncleaved. Only minor misalignment of dsRNA substrates can result in cleavage of the RNAs in the RNase III active site, and the minor misalignment lowers the length fidelity in siRNA production. Because only slightly misaligned RNA substrates, but not largely misaligned ones, can be cleaved, the siRNAs produced differ by only a few nucleotides to 21 nt. Especially, the minor misalignment of RNAs that causes a higher production of 22-nt siRNAs is predominant, considering the increased 22 nt siRNA ratio both in vivo (Fig. 3C) and in vitro (Fig. 4C).

In the phosphate-binding pocket mutant Dicer-2 (H743A, R752A, R759A, R943A, and R956A), the end of a long dsRNA substrate cannot be properly anchored to the PAZ domain. Instead, it may be weakly bound to the 3′ binding pocket in the PAZ domain. CdsRBD binds the body region of the misanchored RNA substrate and aligns it to the RNase III active site, resulting in the production of low-fidelity siRNAs that differ by only a few nucleotides from 21 nt with normal efficiency.

In summary, we found that CdsRBD of Drosophila Dicer-2 is crucial for efficient and high-fidelity 21-nt siRNA production and for siRNA loading to Argonaute2. Our studies provide insight into the molecular mechanism by which Drosophila Dicer-2 achieves a remarkably high fidelity and efficiency in 21-nt siRNA production to enable efficient RNA silencing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly strains

P[HA-Dicer-2] rescuing transgenes containing an N-terminal HA tag and domain truncation were generated by subcloning the coding sequence of dicer-2 into a pUASTattB plasmid vector. The transgenes were integrated at position 68E1 on the third chromosome, using the BDRC fly strain 24485. The mini-white gene (w+mC) derived from the integrated plasmids and the RFP gene originally present in the fly strain to mark the landing site were removed by using a Cre-Lox system.

Eye pigment measurement

Images of fly eyes were taken using a Leica M125 stereomicroscope. For measurement of eye pigment, the heads of 10 females of each genotype were manually dissected. For each genotype, five samples of two heads each were homogenized using a plastic pestle in 100 µL of 10 mM HCl in ethanol. The homogenates were incubated at 25°C overnight, warmed to 50°C for 5 min, and clarified by centrifugation at 21,000g at room temperature for 5 min. The optical density at 480 nm of the supernatant was measured using NanoDrop2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). We used two-tailed Student's t-test for all the statistical analyses in this paper.

qRT-PCR

RNA was prepared from hand-dissected fly heads using miRVana (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After being treated with Turbo DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using an oligo(dT) primer and AMV Reverse Transcriptase (NEB). qPCR was performed using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix on CFX96 and analyzed using CFX Manager (Bio-Rad). The primers used were as follows: white, 5′-GTGGCCAATGTGTCAACGTC-3′ and 5′-GAGGTATACTGGCACCGAGC-3′; rp49, 5′-CTGCCCACCGGATTCAAG-3′ and 5′-GGAAGCTCCGTTGTGCTCTA-3′.

In vitro Dicing assay

Uniformly 32P-radiolabeled 104-bp RNAs were prepared by T7 RNA polymerase transcription in the presence of α-32P UTP (800 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer). Thirty-bp RNAs were 5′ 32P-radiolabeled using [γ-32P] ATP (6000 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB). All RNAs were gel-purified. The sequences of the strands 1 and 2 of the 104-bp dsRNAs are 5′-GGGCCACAAGUUCAGCGUGUCCGGCGAGGGCGAGGGCGAUGCCACCUACGGCAAGCUGACCCUGAAGUUCAUCUGCACCACCGGCAAGCUGCCCGUGCCCUGGCCC-3′ and 5′-GCCAGGGCACGGGCAGCUUGCCGGUGGUGCAGAUGAACUUCAGGGUCAGCUUGCCGUAGGUGGCAUCGCCCUCGCCCUCGCCGGACACGCUGAACUUGUGGCCCAA-3′. The sequences of the strands 1 and 2 of the 30-bp dsRNAs are 5′-GGAGGUAGUAGGUUGUAUAGUAGUAAGACC-3′ and 5′-GGUCUUACUACUAUACAACCUACUACCUCCAC-3′, where deoxynucleotides to block one end are italicized and underlined.

Ovary lysates were prepared by homogenizing hand-dissected ovaries in lysis buffer (30 mM Hepes-KOH pH 7.4, 100 mM KOAc, 2 mM MgOAc, 0.5 mM PMSF, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail. Of note, 100× protease inhibitor cocktail contains 120 mg/mL 1 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride [AEBSF], 1 mg/mL Aprotinin, 7 mg/mL Bestatin, 1.8 mg/mL E-64, and 2.4 mg/mL Leupeptin) followed by centrifugation of the lysates at 21,000g at 4°C for 10 min. The protein concentrations in the supernatant were measured using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After the measurement of the protein concentrations, ovary lysates were diluted to 2.1 mg/mL total protein with lysis buffer and 100 mM DTT solution was added to the final 1 mM DTT concentration. The ovary lysates were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use.

N-terminally 6xHis-tagged recombinant Dicer-2 proteins were expressed and purified from Sf9 cells using Ni-sepharose and HitrapQHP (GE Healthcare). Silver staining was performed using Silver Stain Plus Kit (Bio-Rad).

Dicing reactions were performed with 100 nM radiolabeled RNA substrate, 1 mM ATP, 0.5 U/µL Optizyme RNase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and either ovary lysate (1.05 mg/mL total protein concentration) or 6 nM purified recombinant Dicer-2 protein at 25°C as previously described (Fukunaga et al. 2014). The reaction was stopped by transferring aliquots into RNA loading buffer (98% [v/v] formamide, 5 mM EDTA, 0.05% [w/v] bromophenol blue, and 0.05% xylene cyanol). The reaction time course samples were run on urea-PAGE gels. Dried gels were exposed to image plates and analyzed with FLA-9500 and ImageQuant (GE Healthcare).

In vitro RISC loading assay

Guide strand RNA (5′-UGAGGUAGUAGGUUGUAUAGU-3′) was 5′ 32P-radiolabeled using [γ-32P] ATP (6000 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB) and gel-purified. siRNA duplex was prepared by mixing the 5′ 32P-radiolabeled guide strand RNA and an unlabeled passenger strand RNA (5′-UAUACAACCUACUACCUCCUU-3′). RISC loading reactions were performed with 8 nM radiolabeled siRNA duplex, 1 mM ATP, 0.5 U/µL Optizyme RNase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and ovary lysate (1.45 mg/mL total protein concentration) at 25°C. After 30 min, 0.23-fold volume of heparin mix solution (60 mM potassium phosphate, 3 mM magnesium chloride, 3% PEG8000, 8% glycerol, 4 mg/mL heparin) was added to the reaction samples and they were transferred on ice. The reaction samples were run on native PAGE gel (4% PAGE in 1× TBE buffer) at 4°C. Dried gels were exposed to image plates and analyzed with FLA-9500 and ImageQuant (GE Healthcare).

Coimmunoprecipitation

Ovary lysates were prepared by homogenizing hand-dissected ovaries in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 5% glycerol, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail. Of note, 100× protease inhibitor cocktail contains 120 mg/mL 1 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride [AEBSF], 1 mg/mL Aprotinin, 7 mg/mL Bestatin, 1.8 mg/mL E-64, and 2.4 mg/mL Leupeptin) followed by centrifugation of the lysates at 21,000g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was used for anti-HA immunoprecipitation using Pierce Anti-HA Magnetic Beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at room temperature for 1 h. After washing the beads with lysis buffer, the proteins were eluted with 100 mM Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0), and the eluates were neutralized by mixing with a 15% volume of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.5).

Western blot

Whole fly lysates were prepared by homogenizing the adult flies in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1% [v/v] NP-40, 0.1% [w/v] SDS, 0.5% [w/v] sodium deoxycholate,1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM PMSF). The homogenates were clarified by centrifugation at 21,000g at 4°C for 10 min, and the supernatant was used for Western blot. Ovary lysates and the immunoprecipitation samples were prepared as above. Mouse anti-HA (Sigma, H3663), rabbit anti-Tubulin (Sigma, T3526), rabbit anti-α-Tubulin (Abcam, ab52866), rat anti-Vasa (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), mouse anti-Dicer-2 (Miyoshi et al. 2009), mouse anti-R2D2 (Nishida et al. 2013), mouse anti-Ago2 (Miyoshi et al. 2005) (kind gifts from Dr. Mikiko Siomi and Dr. Haruhiko Siomi), and rabbit anti-R2D2 (Liu et al. 2003) (kind gift from Dr. Qinghua Liu), were used as primary antibodies. IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse IgG, IRDye 800CW goat anti-rat IgG, IRDye 800CW goat anti-rabbit IgG, and IRDye 680RD goat anti-rabbit IgG (Licor) were used as secondary antibodies. The membrane was scanned on an Odyssey imaging system (Licor).

Small RNA sequencing

Small RNA libraries were prepared, sequenced on Hiseq4000 (Illumina), and analyzed using piPipes, as previously described (Fukunaga et al. 2012, 2014; Han et al. 2015a,b). The sequencing statistics of the small RNAs are summarized in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2. The GEO accession numbers for the small RNA libraries reported in this paper are GSE84532 and GSE94803.

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Richard Carthew (Northwestern University) for fly strains of white-inverted repeat (wIR), dicer-2null, and dicer-2G31R. We are grateful to Drs. Mikiko Siomi (University of Tokyo) and Haruhiko Siomi (Keio University) for mouse monoclonal antibodies for Dicer-2, R2D2, and Ago2. We are grateful to Dr. Qinghua Liu (UT Southwestern) for rabbit polyclonal antibody for R2D2. We are grateful to Dr. Bo Han (PacBio) and Dr. Junko Tsuji (University of Massachusetts Medical School) for their help in the bioinformatics analysis. We are grateful to Susan Liao at the Fukunaga laboratory for her comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant (15SDG23220028) from the American Heart Association and start-up funds provided by the Department of Biological Chemistry at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine to R.F.

Author contributions: R.F. was responsible for conceptualization; S.K.K., L.Z., and R.F. were responsible for methodology; the investigation was performed by S.K.K., L.Z. and R.F.; S.K.K., L.Z., and R.F. wrote the manuscript; R.F. acquired the funding and supervised the work.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.059915.116.

REFERENCES

- Ameres SL, Hung JH, Xu J, Weng Z, Zamore PD. 2011. Target RNA-directed tailing and trimming purifies the sorting of endo-siRNAs between the two Drosophila Argonaute proteins. RNA 17: 54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. 2001. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature 409: 363–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronkhorst AW, van Rij RP. 2014. The long and short of antiviral defense: small RNA-based immunity in insects. Curr Opin Virol 7: 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenik ES, Fukunaga R, Lu G, Dutcher R, Wang Y, Tanaka Hall TM, Zamore PD. 2011. Phosphate and R2D2 restrict the substrate specificity of Dicer-2, an ATP-driven ribonuclease. Mol Cell 42: 172–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech B, Malone CD, Zhou R, Stark A, Schlingeheyde C, Dus M, Perrimon N, Kellis M, Wohlschlegel JA, Sachidanandam R, et al. 2008. An endogenous small interfering RNA pathway in Drosophila. Nature 453: 798–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir SM, Martinez J, Patkaniowska A, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. 2001. Functional anatomy of siRNAs for mediating efficient RNAi in Drosophila melanogaster embryo lysate. EMBO J 20: 6877–6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fablet M. 2014. Host control of insect endogenous retroviruses: small RNA silencing and immune response. Viruses 6: 4447–4464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemr M, Malik R, Franke V, Nejepinska J, Sedlacek R, Vlahovicek K, Svoboda P. 2013. A retrotransposon-driven dicer isoform directs endogenous small interfering RNA production in mouse oocytes. Cell 155: 807–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstemann K, Horwich MD, Wee L, Tomari Y, Zamore PD. 2007. Drosophila microRNAs are sorted into functionally distinct argonaute complexes after production by dicer-1. Cell 130: 287–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga R, Zamore PD. 2014. A universal small molecule, inorganic phosphate, restricts the substrate specificity of Dicer-2 in small RNA biogenesis. Cell Cycle 13: 1671–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga R, Han BW, Hung JH, Xu J, Weng Z, Zamore PD. 2012. Dicer partner proteins tune the length of mature miRNAs in flies and mammals. Cell 151: 533–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga R, Colpan C, Han BW, Zamore PD. 2014. Inorganic phosphate blocks binding of pre-miRNA to Dicer-2 via its PAZ domain. EMBO J 33: 371–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghildiyal M, Seitz H, Horwich MD, Li C, Du T, Lee S, Xu J, Kittler EL, Zapp ML, Weng Z, et al. 2008. Endogenous siRNAs derived from transposons and mRNAs in Drosophila somatic cells. Science 320: 1077–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S, Jin L, Zhang Y, Huang Y, Zhang F, Valdmanis PN, Kay MA. 2012. The loop position of shRNAs and pre-miRNAs is critical for the accuracy of dicer processing in vivo. Cell 151: 900–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han BW, Wang W, Li C, Weng Z, Zamore PD. 2015a. Noncoding RNA. piRNA-guided transposon cleavage initiates Zucchini-dependent, phased piRNA production. Science 348: 817–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han BW, Wang W, Zamore PD, Weng Z. 2015b. piPipes: a set of pipelines for piRNA and transposon analysis via small RNA-seq, RNA-seq, degradome- and CAGE-seq, ChIP-seq and genomic DNA sequencing. Bioinformatics 31: 593–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig JV, Forstemann K. 2011. Loqs-PD and R2D2 define independent pathways for RISC generation in Drosophila. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 3836–3851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner G, McLachlan J, Pasquinelli AE, Balint E, Tuschl T, Zamore PD. 2001. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science 293: 834–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandasamy SK, Fukunaga R. 2016. Phosphate-binding pocket in Dicer-2 PAZ domain for high-fidelity siRNA production. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113: 14031–14036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlikow M, Goic B, Saleh MC. 2014. RNAi and antiviral defense in Drosophila: setting up a systemic immune response. Dev Comp Immunol 42: 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura Y, Saito K, Kin T, Ono Y, Asai K, Sunohara T, Okada TN, Siomi MC, Siomi H. 2008. Drosophila endogenous small RNAs bind to Argonaute 2 in somatic cells. Nature 453: 793–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy EM, Whisnant AW, Kornepati AV, Marshall JB, Bogerd HP, Cullen BR. 2015. Production of functional small interfering RNAs by an amino-terminal deletion mutant of human Dicer. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112: E6945–E6954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketting RF, Fischer SE, Bernstein E, Sijen T, Hannon GJ, Plasterk RH. 2001. Dicer functions in RNA interference and in synthesis of small RNA involved in developmental timing in C. elegans. Genes Dev 15: 2654–2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight SW, Bass BL. 2001. A role for the RNase III enzyme DCR-1 in RNA interference and germ line development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 293: 2269–2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau PW, Guiley KZ, De N, Potter CS, Carragher B, MacRae IJ. 2012. The molecular architecture of human Dicer. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19: 436–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Carthew RW. 2003. Making a better RNAi vector for Drosophila: use of intron spacers. Methods 30: 322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Nakahara K, Pham JW, Kim K, He Z, Sontheimer EJ, Carthew RW. 2004. Distinct roles for Drosophila Dicer-1 and Dicer-2 in the siRNA/miRNA silencing pathways. Cell 117: 69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Rand TA, Kalidas S, Du F, Kim HE, Smith DP, Wang X. 2003. R2D2, a bridge between the initiation and effector steps of the Drosophila RNAi pathway. Science 301: 1921–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma E, MacRae IJ, Kirsch JF, Doudna JA. 2008. Autoinhibition of human dicer by its internal helicase domain. J Mol Biol 380: 237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRae IJ, Zhou K, Li F, Repic A, Brooks AN, Cande WZ, Adams PD, Doudna JA. 2006. Structural basis for double-stranded RNA processing by Dicer. Science 311: 195–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRae IJ, Zhou K, Doudna JA. 2007. Structural determinants of RNA recognition and cleavage by Dicer. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14: 934–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K, Tsukumo H, Nagami T, Siomi H, Siomi MC. 2005. Slicer function of Drosophila Argonautes and its involvement in RISC formation. Genes Dev 19: 2837–2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K, Okada TN, Siomi H, Siomi MC. 2009. Characterization of the miRNA-RISC loading complex and miRNA-RISC formed in the Drosophila miRNA pathway. RNA 15: 1282–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida KM, Miyoshi K, Ogino A, Miyoshi T, Siomi H, Siomi MC. 2013. Roles of R2D2, a cytoplasmic D2 body component, in the endogenous siRNA pathway in Drosophila. Mol Cell 49: 680–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Balla S, Martin R, Liu N, Lai EC. 2008a. Two distinct mechanisms generate endogenous siRNAs from bidirectional transcription in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15: 581–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Chung WJ, Ruby JG, Guo H, Bartel DP, Lai EC. 2008b. The Drosophila hairpin RNA pathway generates endogenous short interfering RNAs. Nature 453: 803–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Ladewig E, Zhou L, Lai EC. 2013. Functional small RNAs are generated from select miRNA hairpin loops in flies and mammals. Genes Dev 27: 778–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JE, Heo I, Tian Y, Simanshu DK, Chang H, Jee D, Patel DJ, Kim VN. 2011. Dicer recognizes the 5′ end of RNA for efficient and accurate processing. Nature 475: 201–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provost P, Dishart D, Doucet J, Frendewey D, Samuelsson B, Radmark O. 2002. Ribonuclease activity and RNA binding of recombinant human Dicer. EMBO J 21: 5864–5874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha NK, Trettin KD, Aruscavage PJ, Bass BL. 2015. Drosophila dicer-2 cleavage is mediated by helicase- and dsRNA termini-dependent states that are modulated by Loquacious-PD. Mol Cell 58: 406–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DW, Ma E, Shigematsu H, Cianfrocco MA, Noland CL, Nagayama K, Nogales E, Doudna JA, Wang HW. 2013. Substrate-specific structural rearrangements of human Dicer. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20: 662–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi A, Kawamata T, Izumi N, Seitz H, Tomari Y. 2011. Recognition of the pre-miRNA structure by Drosophila Dicer-1. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 1153–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker NC, Maity TS, Ye X, Aruscavage PJ, Krauchuk AA, Liu Q, Bass BL. 2011. Dicer's helicase domain discriminates dsRNA termini to promote an altered reaction mode. Mol Cell 41: 589–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wostenberg C, Lary JW, Sahu D, Acevedo R, Quarles KA, Cole JL, Showalter SA. 2012. The role of human Dicer-dsRBD in processing small regulatory RNAs. PLoS One 7: e51829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynant N, Santos D, Vanden Broeck J. 2014. Biological mechanisms determining the success of RNA interference in insects. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 312: 139–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X, Paroo Z, Liu Q. 2007. Functional anatomy of the Drosophila microRNA-generating enzyme. J Biol Chem 282: 28373–28378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Kolb FA, Jaskiewicz L, Westhof E, Filipowicz W. 2004. Single processing center models for human Dicer and bacterial RNase III. Cell 118: 57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.