Abstract

The blood feeding requirements of insects are often exploited by pathogens for their transmission. This is also the case of the protozoan parasites of genus Plasmodium, the causative agents of malaria. Every year malaria claims the lives of a half million people, making its vector, the Anopheles mosquito, the deadliest animal in the world. However, mosquitoes mount powerful immune responses that efficiently limit parasite proliferation. Among the immune signaling pathways identified in the main malaria vector Anopheles gambiae, the NF-κB-like signaling cascades REL2 and REL1 are essential for eliciting proper immune reactions, but only REL2 has been implicated in the responses against the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Instead, constitutive activation of REL1 causes massive killing of rodent malaria parasites. In this review, we summarize our present knowledge on the REL2 pathway in Anopheles mosquitoes and its role in mosquito immune responses to diverse pathogens, with a focus on Plasmodium. Mosquito-parasite interactions are crucial for malaria transmission and, therefore, represent a potential target for malaria control strategies.

Keywords: Anopheles gambiae, Plasmodium, NF-κB signaling, IMD, REL2 pathway, malaria, vector biology, innate immunity

Introduction

Mosquitoes are vectors of human infectious diseases with immense importance for public health. Malaria, caused by the Plasmodium protozoa, is the deadliest disease transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes. Plasmodium development in the mosquito takes about 3 weeks. A series of mosquito factors affect malaria transmission, among them female longevity, nutritional fitness and efficient immune responses. The ookinete is by far the most fragile parasite stage, attracting the majority of immune responses. It swiftly develops from the sexually created zygote, and its task is to escape the dangerous gut environment by traversing the unicellular epithelium and to hide beneath the basal lamina that lines the mosquito midgut. If successful, ookinetes transform within the second day into vegetative protective oocysts that in a fortnight give rise to thousands of sporozoites that migrate and invade the salivary glands to be ready for a new transmission. Vector-parasite molecular interactions have been studied mostly in the laboratory model of infections of A. gambiae, the major malaria vector in the sub-Saharan Africa, with the rodent malaria parasite P. berghei. Although rodent and human parasites have similar invasion strategies in the insect vector, their elimination is mediated by two distinct nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) immune pathways, REL2/Imd and REL1/Toll. NF-κB, initially discovered for its DNA-binding activity to an immunoglobulin-κ light chain enhancer in B lymphocytes, emerged as the central regulator of immune responses in animal kingdom (Sen and Baltimore, 1986). In Anopheles, experimental activation of REL2 aborts development of P. falciparum ookinetes, while constitutive induction of REL1 kills rodent parasites (Frolet et al., 2006; Garver et al., 2009). However, in both cases the molecular mechanisms of parasite recognition and killing remain unknown. In this review, we discuss immune responses of A. gambiae, with a focus on the REL2 signaling pathway, which is believed to be the major regulator of mosquito immune responses against human malaria parasites.

Immune signaling and pathogen recognition

The Toll and Imd pathways in Drosophila regulate expression of hundreds of infection-inducible genes. While the Toll pathway, initially described in Drosophila embryonic development, is essential for defenses against Gram-positive bacteria and fungi (Lemaitre et al., 1996; Rutschmann et al., 2002), the Imd pathway orchestrates responses against Gram-negative bacteria and viruses (Kaneko et al., 2004; Costa et al., 2009).

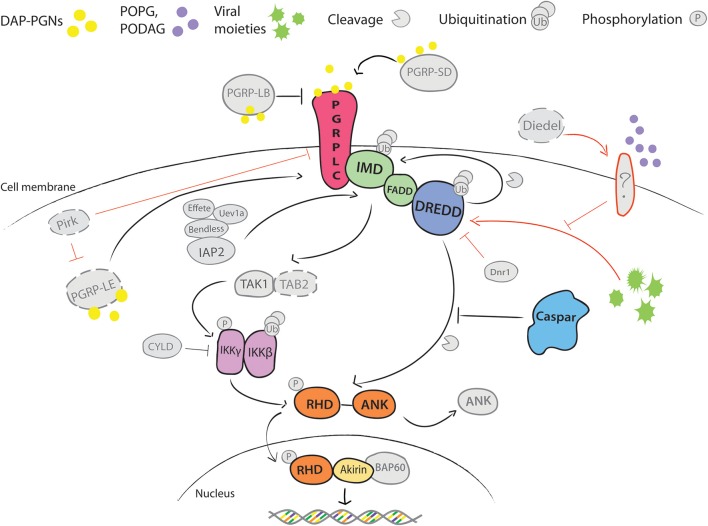

Immune activation is mediated by recognition of pathogen derived molecules, such as metabolites, nucleic acids, or cell wall components that are released during pathogen growth and division (Vance et al., 2009). Among microbial and host factors that induce Imd signaling, the best characterized is the DAP-type peptidoglycan (DAP-PGN), a cell wall component of Gram-negative bacteria. DAP-PGN recognition at the cell surface is mediated by transmembrane peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs) (Choe et al., 2002; Gottar et al., 2002; Figure 1). In contrast, activation of the Toll pathway is initiated by binding of circulating recognition complexes to the lysine-type PGNs or glucans (Gobert et al., 2003; Leulier et al., 2003). This binding triggers downstream serine protease cascades, leading to processing and binding of the endogenous factor Spaetzle to the transmembrane receptor Toll (Morisato and Anderson, 1994; Schneider et al., 1994). Activation of both pathways culminates in the phosphorylation and release of the NF-κB-like transcription factors Dif, Dorsal and Relish from the inhibitors, and their translocation into the nucleus. The release of the Imd transcription factor Relish involves Caspar, which in its inactive state prevents cleavage of the Relish inhibitory domain (Kim et al., 2006; Figure 1). Phosphorylation of Cactus, the negative regulator of the Toll pathway, leads to its degradation and release of the transactivators Dif and Dorsal (Wu and Anderson, 1998).

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of Imd pathway in Drosophila melanogaster. DAP-type PGNs trigger the activation of Imd signaling by direct interaction with the immune cell. Of Peptido-Glycan Recognition Proteins (PGRPs) that bind these pathogen-derived molecules, transmembrane PGRP-LC is the main receptor linked to activation of Imd pathway (Choe et al., 2002; Gottar et al., 2002). Its activity is enhanced in circulation by secreted PGRP-SD and intracellularly by the cytosolic PGRP-LE (Takehana et al., 2002; Iatsenko et al., 2016). Both proteins can directly bind DAP-PGNs and promote PGRP-LC activity. Another extracellular PGN-binding protein PGRP-LB antagonizes PGRP-LC activity by scavenging PGNs in circulation (Zaidman-Rémy et al., 2006). PGN binding induces conformational changes in PGRP-LC that promotes recruitment of the death domain-containing proteins Imd, FADD and DREDD caspase from the nucleus to the plasma membrane, and it is followed by subsequent polyubiquitination of DREDD by ubiquitin E3 ligase IAP2, cleavage of Imd by DREDD and exposure of K63 site for polyubiquitination by IAP2 and E2 conjugating enzymes Bendless, Effete and Uev1a (Paquette et al., 2010; Meinander et al., 2012). The K63-polyubiquitin chains, most likely, serve as activators of TAK1 kinase via the ubiquitin-binding domain of its regulatory protein TAB2 (Paquette et al., 2010). TAK1/TAB2 complex phosphorylates IKK complex, which consists of β and γ subunits. IKKβ further phosphorylates the NF-κB-like transcription factor Relish, while a regulatory IKKγ subunit regulates DREDD-mediated cleavage of Relish (Ertürk-Hasdemir et al., 2009). Relish consists of the Rel Homology Domain (RHD) and the inhibitory ankyrin-repeat rich domain (ANK) (Dushay et al., 1996). DREDD caspase cleaves the ANK domain from RHD. RHD translocates to the nucleus and initiates transcription of target genes. Caspar acts as a negative regulator of the pathway by inhibiting DREDD-dependent cleavage of Relish (Kim et al., 2006). Immunomodulatory cytokine Diedel restrains deleterious non-canonical activation of Imd in presence and absence of viral infection (Lamiable et al., 2016). Receptor that activates the pathway to viruses is not yet known However, epistasis analyses placed Diedel function between Imd and IKKγ, as mutants for both Diedel and Imd were more prone to spontaneous pathogenesis than Diedel/IKKγ double mutants (Lamiable et al., 2016). Additionally, activation of the pathway is held in check by other factors, including CYLD, Dnr1, and Pirk. Finally, transcriptional activity of Relish is regulated at the chromatin level through interactions with a nuclear co-factor Akirin and BAP60 component of Brahma chromatin remodeling complex. Akirin recruits BAP60 complex to promoters of a subset of Relish effector genes and hence regulates their transcription (Goto et al., 2008; Bonnay et al., 2014). Positive and inhibitory interactions are depicted with → and |–, respectfully; black—well established, and red—yet unknown interactions. Color coding highlights our current knowledge on the pathway in Anopheles gambiae. Confirmed pathway components are indicated in color. Components depicted in gray represent orthologs identified by genomic searches, but whose function was not experimentally validated. Components in gray with dashed lines are absent in A. gambiae.

The Imd role in Drosophila immunity has been recently extended to antiviral responses. Surprisingly, instead of protection, constitutive activation of the Imd pathway by depletion of a secreted cytokine-like molecule Diedel, enhances viral pathogenesis (Lamiable et al., 2016). Although the underlying mechanism is not entirely clear, in the absence of Diedel, viral infection triggers the pathway through an alternative, non-canonical cytoplasmic route by bypassing the function of the PGRP receptors (Lamiable et al., 2016). Similarly, non-canonical activation of this pathway was also reported in ticks that lack transmembrane PGRP-LC and death domain proteins, Imd and FADD, but feature a conserved ubiquitination module, Relish and Caspar (Figure 1). The tick pathway is induced by lipid components of membranes specific to PGN-deficient bacteria (Shaw et al., 2017). Importantly, the same lipids also induce the Imd pathway in Drosophila cell lines, suggesting that non-canonical activation of the Imd pathway may be evolutionarily conserved (Shaw et al., 2017).

REL2 pathway in A. gambiae

The vast knowledge that accumulated on the immune signaling in Drosophila has served as a blueprint for studying Anopheles mosquitoes. Sequencing of the A. gambiae genome benefited identification of the conserved components of the pathway (Christophides et al., 2002; Holt et al., 2002). However, in spite of considerable interest and potential importance in antiparasitic responses, surprisingly little is known about the targets of the Imd/REL2 pathway in Anopheles.

Genomic searches in A. gambiae identified three potential receptors: PGRP-SD, PGRP-LB and PGRP-LC. PGRP-SD has not been characterized, whereas functional analysis of PGRP-LB did not reveal its role in mosquito survival upon bacterial infections (Meister et al., 2009). Instead, the structure and function of PGRP-LC were characterized in a great detail (Meister et al., 2009). PGRP-LC encodes three splice variants (LC1-3) that differ in the organization of their extracellular PGN-binding domains. Structural modeling uncovered the potential of all three isoforms to bind both types of PGNs, highlighting a striking difference between the mosquito PGRP-LC with broad sensing capacities and the Drosophila PGRP-LC, which binds exclusively DAP-PGNs. The broad specificity of PGN binding of the Anopheles PGRP-LC was further substantiated by functional analyses that demonstrated equally critical role of the receptor in mosquito survival to Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (Meister et al., 2009). Although infections with both bacteria induced expression of genes encoding antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) Cecropin1 and Defensin1, their transcriptional induction was PGRP-LC independent (Meister et al., 2009), therefore, the mechanisms underlying the PGRP-LC-mediated resistance to bacteria remain to be elucidated.

PGRP-LC plays an important role in regulating proliferation of the mosquito microbiota after blood feeding (Meister et al., 2009) and may, in big part, explain the role of the pathway in modulating development of Plasmodium parasites. Indeed, similar to the phenotype of PGRP-LC silencing, clearing mosquito microbiota by antibiotics prior to infections increases Plasmodium loads, whereas feeding mosquitoes with bacteria boosts their resistance to Plasmodium in a PGRP-LC-dependent manner (Meister et al., 2009). Therefore, it is possible that the REL2 pathway is activated after blood feeding by massive bacterial proliferation, whereas Plasmodium parasites are simple bystanders in this process and do not directly induce mosquito immune responses. Further transcriptomics studies examined mosquito responses to infections with P. falciparum and P. berghei and identified species-specific patterns of gene expression (Dimopoulos et al., 2002; Dong et al., 2006). Nevertheless, a significant overlap observed in the responses to bacterial and Plasmodium infections provides further support to the hypothesis that REL2 modulation of Plasmodium development may be triggered by the PGRP-LC-mediated recognition of bacteria.

Regardless of the trigger, it is expected from the Drosophila model that conformational changes of PGRP-LC will recruit the death-domain containing receptor-adaptor complex (Imd, FADD and DREDD), which will, via the TAK1/TAB2 complex, activate the IKK signalosome and inhibit the negative regulator Caspar (Figure 1). Relish activation is achieved by phosphorylation by the IKK signalosome and by cleavage of the inhibitory ankirin domain by the DREDD caspase (Figure 1). Transcriptional activity of Relish at the promoters of some genes is further regulated by its nuclear co-factor Akirin. Using RNAi silencing and its effects on P. falciparum infections, most of the pathway components were functionally confirmed in A. gambiae, except for TAK1, whose depletion did not impact Plasmodium development (Meister et al., 2005; Garver et al., 2012; Ramphul et al., 2015).

Further studies of the REL2 pathway identified some mosquito-specific particularities. In contrast to Drosophila, REL2 in mosquitoes encodes three alternatively-spliced isoforms that were first identified in another mosquito species, Aedes aegypti (Shin et al., 2002; Antonova et al., 2009). In A. gambiae, Meister et al. (2005) described two REL2 forms: a long transcript (REL2-F) coding for the full-length protein consisting of Rel-homology domain (RHD) and ankyrin-rich repeat (ANK), and a short form (REL2-S) encoding only RHD. Although authors proposed that the isoforms regulate expression of distinct sets of genes, both isoforms regulate Plasmodium development (Garver et al., 2012). Currently, the molecular mechanisms underlying activation of REL2 in Anopheles remain unresolved. It is unknown whether REL2 requires proteolytic activation by CaspL1 (Anopheles ortholog of DREDD) and how Caspar inhibits its activation. Surprisingly, functional analyses by gene silencing suggested a genetic interaction between Caspar and REL2-S, whereas regulation of REL2-F was not investigated (Garver et al., 2012). These results are inconsistent with the proposed mechanism of Relish inhibition by Caspar in Drosophila, where Caspar binding to the inhibitory ankirin domain prevents its cleavage by DREDD. However, as REL2-S lacks the ANK domain, the inhibitory mechanism of Caspar in Anopheles remains unclear. Co-silencing of Caspar with Imd, FADD, CaspL1 or IKK2, rescued the negative effect of the single Caspar knockdown on parasite development, confirming the role of these components in activation of REL2. Of particular interest is the role of Akirin, the nuclear co-factor of REL2, which regulates chromatin conformation and provides access to the promoter regions of a set of effector genes in Drosophila (Goto et al., 2008; Bonnay et al., 2014). As Akirin contributes to antiparasitic responses (Da Costa et al., 2014), better understanding of its function and of its target genes should shed light on regulation of Plasmodium killing.

So far, abortion of Plasmodium development was observed only upon experimentally-induced activation of the NF-κB pathways. Therefore, species-specific elimination of Plasmodium parasites by REL2 and REL1 seems to be independent of parasite recognition and may be explained by the activation of distinct sets of effectors. It is also plausible, that Plasmodium species differ in their susceptibility to the immune defenses triggered by these pathways. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathway-specific parasite elimination may provide interesting insights into biology of Plasmodium species.

Effectors

Antimicrobial peptides are powerful effectors of innate immunity (Jenssen et al., 2006). They bind and directly kill a broad spectrum of pathogens by disrupting cell membrane integrity (Yeaman and Yount, 2003). Insect AMPs are synthesized by the fat body with some contribution of hemocytes, and are secreted into the hemolymph shortly after infection. In addition, some AMPs are also produced by epithelial cells in a tissue-specific manner (Tzou et al., 2000). Expression of the AMP genes Drosomycin and Diptericins in the fat body is regulated by Toll and Imd, respectively, whereas both pathways contribute to expression of other AMP genes (e.g. Defensin, Drosocin, Metchnikowin, Attacins, and Cecropins) (Ferrandon et al., 2007).

Several AMP genes have been identified in A. gambiae: Defensins (Def1-5), Cecropins (Cec1-4), Gambicin (Gamb), and Attacin (Holt et al., 2002; Mongin et al., 2004). Antimicrobial and antifungal activities of the recombinant Cec1, Gamb, and Def1 peptides were demonstrated in vitro against filamentous fungi (Cec1, Gamb, Def1), Gram-negative (Cec1, Gamb) and Gram-positive bacteria (Def,1 Cec1, Gamb) (Vizioli et al., 2000, 2001a,b). In vivo silencing of Def1 increases mosquito susceptibility to Gram-positive bacteria but does not affect development of P. berghei (Blandin et al., 2002). At the transcriptional level, however, expression of Def1 was upregulated by infections with human and rodent parasites (Tahar et al., 2002). Gambicin, the only mosquito-specific AMP, exhibited some activity against P. berghei ookinetes in vitro, whereas depletion of Gamb in vivo increased mosquito susceptibility to Gram-positive bacteria, P. berghei and, to a lower extent, to P. falciparum (Vizioli et al., 2001a; Dong et al., 2006). Interestingly, transgenic over-expression of Cec1 fused to the Shiva toxin inhibited development of P. berghei oocysts in A. gambiae (Kim et al., 2004). In spite of these results, the exact role of antimicrobial peptides in the mosquito defenses against Plasmodium is still incompletely understood.

Identification of the effectors of REL2 and REL1 is crucial for understanding the specificity of malaria killing in the mosquito. However, only a handful of immune genes in Anopheles have been assigned to either pathway. Frolet et al. (2006) did not observe any changes in the expression of AMP genes upon constitutive activation of REL1, leaving an open possibility of their regulation by REL2. In vitro studies provided some support of Cec1 and Gamb regulation by REL2 (Meister et al., 2005), but a more recent study in vivo suggested a dual regulation of AMP genes by both pathways (Garver et al., 2009).

The complement-like system emerged as a powerful arm of the mosquito immune responses to a broad spectrum of pathogens. The central component of this system, the thioester-containing protein 1 (TEP1), is a major determinant of malaria killing (Blandin et al., 2004; Garver et al., 2009; Molina-Cruz et al., 2012; Nsango et al., 2012). TEP1 binds to the surface of invading Plasmodium ookinetes and bacteria, and promotes their killing by lysis and phagocytosis, respectively (Blandin et al., 2004). TEP1 is a highly reactive protein and requires a complex of two leucine-rich repeat proteins [leucine-rich repeat immune protein 1 (LRIM1) and Anopheles Plasmodium-responsive leucine-rich repeat 1C (APL1C)] to prevent its precocious activation and precipitation (Frolet et al., 2006; Fraiture et al., 2009). TEP1 or LRIM1 co-silencing with Cactus completely reverts the refractory phenotype of Cactus knockdown in A. gambiae infections with P. berghei (Frolet et al., 2006). Silencing of TEP1 also results in higher intensities of P. falciparum infections (Garver et al., 2009), however, levels of TEP1 protection against P. falciparum vary with the genotype and genetic complexity of Plasmodium infections (Molina-Cruz et al., 2012; Nsango et al., 2012). Similar to AMPs, expression of the complement-like genes is regulated by both pathways (Frolet et al., 2006).

Another interesting multi-member protein family with potential roles in mosquito immune responses is the family of fibrinogen related proteins (FBNs or FREPs). It comprises 59 members in A. gambiae, 37 in A. aegypti and 14 in D. melanogaster (Christophides et al., 2002; Dong and Dimopoulos, 2009). Only few FBNs have been functionally characterized. Silencing of FBN9, FBN22 and FBN39 impairs mosquito survival upon bacterial infections; depletion of FBN8, FBN9, FBN30, and FBN39 increases mosquito susceptibility to Plasmodium parasites, while silencing of FBN1 decreases parasite loads (Dong and Dimopoulos, 2009; Li et al., 2013; Simões et al., 2017). Little is known about regulation of FBN expression, except for FBN9, whose expression is regulated by REL2 (Garver et al., 2009). FBN9 binds to malaria parasites and bacteria, thereby exposing them for killing by an as yet unknown mechanism (Dong and Dimopoulos, 2009). Surprisingly, transgenic expression of FBN9 in the fat body driven by a blood feeding-inducible promoter did not enhance mosquito resistance to P. falciparum (Simões et al., 2017). This unexpected result highlights the importance of tissue-specific REL2 regulation, which has not been addressed yet.

Cellular immune responses

Several independent reports implicated REL2 pathway in the immune responses of hemocytes, the mosquito blood cells. Transcripts encoding the pathway components were identified in the hemocyte-enriched transcriptome and their expression levels were further upregulated by blood meal and by P. berghei ookinetes (Baton et al., 2009). Furthermore, hemocytes synthesize proteins whose expression is regulated by the REL2 pathway (e.g., AMPs, TEP1, LRIM1, and FBN9) (Levashina et al., 2001; Baton et al., 2009). Some of these proteins (TEP1, TEP3, PGRP-LC, and LRIM1) also contribute to the efficient phagocytosis of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Moita et al., 2005). In Drosophila, hemocytes also serve as messengers in inter-organ communication. For example, an amplitude of systemic immune responses induced by localized infections is diminished in hemocyte-depleted fruit fly mutants, revealing hemocyte contribution to the amplification of the fat-body mediated immune responses (Charroux and Royet, 2009; Wu et al., 2012). The reactive oxygen species that act as local triggers of hemocyte activation, also efficiently activate the Imd pathway (Foley and O'Farrell, 2003; Wu et al., 2012), further supporting the potential role of this pathway in hemocyte activation.

Melanization

The Anopheles REL2 pathway negatively regulates melanization, a process of melanin deposition in defense mechanisms (such as wound healing or pathogen killing), metamorphosis and tanning during development. Silencing of PGRP-LC and of both REL2 isoforms not only renders mosquitoes more susceptible to Plasmodium but also induces melanization of P. berghei ookinetes (Meister et al., 2005, 2009; Frolet et al., 2006). The reverse is observed in Drosophila, where the intracellular receptor PGRP-LE is absolutely required for melanization (Takehana et al., 2004). REL1 pathway, on the other hand, promotes melanization in both insect species (Ligoxygakis et al., 2002; Frolet et al., 2006). Surprisingly, simultaneous activation of the REL1 pathway by Cactus knockdown and inhibition of the REL2 pathway by REL2 silencing abolishes Plasmodium melanization, revealing the complexity in the regulation of this immune reaction and a potential cross-talk between the two pathways (Frolet et al., 2006).

Conclusions

Although a significant progress has been achieved in identifying the components of the REL2 pathway in mosquitoes, many questions remain unanswered. Little is known about the role of post-translational modifications, such as ubiquitination and phosphorylation, which act as important pathway regulators in Drosophila. Moreover, completely unexplored areas are the contributions of the epigenetic modifications acting at the promoter level to fine tune immune responses. Understanding how chromatin conformations modulate expression patterns of effector genes may offer new insights into the complexity and specificity of REL2-mediated immune responses to a broad range of pathogens. However, even before considering the complexity of epigenetic modifications, it is pivotal to characterize the REL2-specific effectors, which are currently only vaguely known; and to address the questions of Plasmodium recognition and pathway activation upon infection in order to properly understand the parasite-host interaction and Plasmodium killing in the mosquito.

Recent studies in ticks and Drosophila discovered a non-canonical cytoplasmic route of pathway activation that bypasses the PGRP receptor-adaptor complex. These observations open new research avenues regarding receptor(s) and molecular mechanisms of pathway activation. The conservation of this non-canonical route in the evolutionarily distant organisms, such as ticks and Drosophila, may suggest that PGN recognition by PGRPs and further signal transduction by the death-domain module, appeared later in evolution, after separation of arachnids from insects. Instead, the core pathway from the ubiquitination module via Caspar to Relish seems to be broadly conserved across arthropods. Better understanding of the REL2 immune pathway in the malaria mosquitoes should advance our knowledge of conserved mechanisms of innate immunity and may identify new targets for vector-mediated malaria control.

Author contributions

All authors listed, have made substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Maiara Severo for critical reading of the manuscript. SZ is supported by a fellowship from German Research Foundation (DFG), GRK 2046.

References

- Antonova Y., Alvarez K. S., Kim Y. J., Kokoza V., Raikhel A. S. (2009). The role of NF-κB factor REL2 in the Aedes aegypti immune response. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39, 303–314. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baton L., Robertson A., Warr E., Strand M. R., Dimopoulos G. (2009). Genome-wide transcriptomic profiling of Anopheles gambiae hemocytes reveals pathogen-specific signatures upon bacterial challenge and Plasmodium berghei infection. BMC Genomics 10:257. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandin S., Moita L. F., Köcher T., Wilm M., Kafatos F. C., Levashina E. (2002). Reverse genetics in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae: targeted disruption of the Defensin gene. EMBO Rep. 3, 852–856. 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandin S., Shiao S. H., Moita L. F., Janse C. J., Waters A. P., Kafatos F. C., et al. (2004). Complement-like protein TEP1 is a determinant of vectorial capacity in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Cell 116, 661–670. 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00173-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnay F., Nguyen X., Cohen-berros E., Troxler L., Batsche E., Camonis J., et al. (2014). Akirin specifies NF-κB selectivity of Drosophila innate immune response via chromatin remodeling. EMBO J. 33, 1–14. 10.15252/embj.201488456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charroux B., Royet J. (2009). Elimination of plasmatocytes by targeted apoptosis reveals their role in multiple aspects of the Drosophila immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 9797–9802. 10.1073/pnas.0903971106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe K. M., Werner T., Stoven S., Hultmark D., Anderson K. V. (2002). Requirement for a Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein (PGRP) in Relish Activation and Antibacterial Immune Responses in Drosophila. Science 296, 359–362. 10.1126/science.1070216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophides G. K., Zdobnov E., Barillas-Mury C., Birney E., Blandin S., Blass C., et al. (2002). Immunity-related genes and gene families in Anopheles gambiae. Science 298, 159–165. 10.1126/science.1077136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A., Jan E., Sarnow P., Schneider D. (2009). The Imd pathway is involved in antiviral immune responses in Drosophila. PLoS ONE 4:e7436. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa M., Pinheiro-Silva R., Antunes S., Moreno-Cid J., Custódio A., Villar M., et al. (2014). Mosquito Akirin as a potential antigen for malaria control. Malar. J. 13, 470. 10.1186/1475-2875-13-470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimopoulos G., Christophides G. K., Meister S., Schultz J., White K. P., Barillas-Mury C., et al. (2002). Genome expression analysis of Anopheles gambiae: responses to injury, bacterial challenge, and malaria infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 8814–8819. 10.1073/pnas.092274999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y., Aguilar R., Xi Z., Warr E., Mongin E., Dimopoulos G. (2006). Anopheles gambiae immune responses to human and rodent Plasmodium parasite species. PLoS Pathog. 2:e52. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y., Dimopoulos G. (2009). Anopheles fibrinogen-related proteins provide expanded pattern recognition capacity against bacteria and malaria parasites. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 9835–9844. 10.1074/jbc.M807084200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dushay M. S., Asling B., Hultmark D. (1996). Origins of immunity: Relish, a compound Rel-like gene in the antibacterial defense of Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 10343–10347. 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertürk-Hasdemir D., Broemer M., Leulier F., Lane W. S., Paquette N., Hwang D., et al. (2009). Two roles for the Drosophila IKK complex in the activation of Relish and the induction of antimicrobial peptide genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 9779–9784. 10.1073/pnas.0812022106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandon D., Imler J.-L., Hetru C., Hoffmann J. A. (2007). The Drosophila systemic immune response: sensing and signalling during bacterial and fungal infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 862–874. 10.1038/nri2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley E., O'Farrell P. H. (2003). Nitric oxide contributes to induction of innate immune responses to gram-negative bacteria in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 17, 115–125. 10.1101/gad.1018503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraiture M., Baxter R. H. G., Steinert S., Chelliah Y., Frolet C., Quispe-Tintaya W., et al. (2009). Two mosquito LRR proteins function as complement control factors in the TEP1-mediated killing of Plasmodium. Cell Host Microbe 5, 273–284. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frolet C., Thoma M., Blandin S., Hoffmann J., Levashina E. (2006). Boosting NF-κB-dependent basal immunity of Anopheles gambiae aborts development of Plasmodium berghei. Immunity 25, 677–685. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garver L. S., Bahia A. C., Das S., Souza-Neto J., Shiao J., Dong Y., et al. (2012). Anopheles Imd pathway factors and effectors in infection intensity-dependent anti-plasmodium action. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002737. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garver L. S., Dong Y., Dimopoulos G. (2009). Caspar controls resistance to Plasmodium falciparum in diverse anopheline species. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000335. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobert V., Gottar M., Matskevich A. A., Rutschmann S., Royet J., Belvin M., et al. (2003). Dual activation of the Drosophila Toll pathway by two pattern recognition receptors. Science 302, 2126–2130. 10.1126/science.1085432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto A., Matsushita K., Gesellchen V., El Chamy L., Kuttenkeuler D., Takeuchi O., et al. (2008). Akirins are highly conserved nuclear proteins required for NF-κB-dependent gene expression in drosophila and mice. Nat. Immunol. 9, 97–104. 10.1038/ni1543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottar M., Gobert V., Michel T., Belvin M., Duyk G., Hoffmann J., et al. (2002). The Drosophila immune response against Gram-negative bacteria is mediated by a peptidoglycan recognition protein. Nature 416, 640–644. 10.1038/nature734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt R., Subramanian G., Halpern A., Sutton G., Charlab R., Nusskern D., et al. (2002). The genome sequence of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Science 298, 129–149. 10.1126/science.1076181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iatsenko I., Kondo S., Mengin-Lecreulx D., Lemaitre B. (2016). PGRP-SD, an extracellular pattern-recognition receptor, enhances peptidoglycan-mediated activation of the drosophila Imd pathway. Immunity 45, 1013–1023. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenssen H., Hamill P., Hancock R. E. W. (2006). Peptide antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19, 491–511. 10.1128/CMR.00056-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T., Goldman W. E., Mellroth P., Steiner H., Fukase K., Kusumoto S., et al. (2004). Monomeric and polymeric gram-negative peptidoglycan but not purified LPS stimulate the Drosophila IMD pathway. Immunity 20, 637–649. 10.1016/S1074-7613(04)00104-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Lee J. H., Lee S. Y., Kim E., Chung J. (2006). Caspar, a suppressor of antibacterial immunity in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16358–16363. 10.1073/pnas.0603238103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W., Koo H., Richman A. M., Seeley D., Vizioli J., Klocko A. D., et al. (2004). Ectopic expression of a Cecropin transgene in the human malaria vector Anopheles gambie (Diptera: Culicidae): Effects on susceptibility to Plasmodium. Med. Entomol. 41, 447–455. 10.1603/0022-2585-41.3.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamiable O., Kellenberger C., Kemp C., Troxler L., Pelte N., Boutros M., et al. (2016). Cytokine Diedel and a viral homologue suppress the IMD pathway in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 201516122. 10.1073/pnas.1516122113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre B., Nicolas E., Michaut L., Reichhart J. M., Hoffmann J. A. (1996). The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spatzle/Toll/Cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell 86, 973–983. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80172-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leulier F., Parquet C., Pili-Floury S., Ryu J.-H., Caroff M., Lee W.-J., et al. (2003). The Drosophila immune system detects bacteria through specific peptidoglycan recognition. Nat. Immunol. 4, 478–484. 10.1038/ni922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levashina E. A., Moita L. F., Blandin S., Vriend G., Lagueux M., Kafatos F. C. (2001). Conserved role of a complement-like protein in phagocytosis revealed by dsRNA knockout in cultured cells of the mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Cell 104, 709–718. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)09026-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Wang X., Zhang G., Githure J. I., Yan G., James A. (2013). Genome-block expression-assisted association studies discover malaria resistance genes in Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 20675–20680. 10.1073/pnas.1321024110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligoxygakis P., Pelte N., Ji C., Leclerc V., Duvic B., Belvin M., et al. (2002). A serpin mutant links Toll activation to melanization in the host defence of Drosophila. EMBO J. 21, 6330–6337. 10.1093/emboj/cdf661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinander A., Runchel C., Tenev T., Chen L., Kim C.-H., Ribeiro P. S., et al. (2012). Ubiquitylation of the initiator caspase DREDD is required for innate immune signalling. EMBO J. 31, 2770–2783. 10.1038/emboj.2012.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister S., Agianian B., Turlure F., Relógio A., Morlais I., Kafatos F. C., et al. (2009). Anopheles gambiae PGRPLC-Mediated Defense against Bacteria Modulates Infections with Malaria Parasites. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000542. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister S., Kanzok S. M., Zheng X.-L., Luna C., Li T.-R., Hoa N. T., et al. (2005). Immune signaling pathways regulating bacterial and malaria parasite infection of the mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 11420–11425. 10.1073/pnas.0504950102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moita L. F., Wang-Sattler R., Michel K., Zimmermann T., Blandin S., Levashina E., et al. (2005). In vivo identification of novel regulators and conserved pathways of phagocytosis in A. gambiae. Immunity 23, 65–73. 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Cruz A., DeJong R. J., Ortega C., Haile A., Abban E., Rodrigues J., et al. (2012). PNAS Plus: Some strains of Plasmodium falciparum, a human malaria parasite, evade the complement-like system of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E1957–E1962. 10.1073/pnas.1121183109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongin E., Louis C., Holt R. A., Birney E., Collins F. H. (2004). The Anopheles gambiae genome: an update. Trends Parasitol. 20, 49–52. 10.1016/j.pt.2003.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisato D., Anderson K. V. (1994). The spätzle gene encodes a component of the extracellular signaling pathway establishing the dorsal-ventral pattern of the Drosophila embryo. Cell 76, 677–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nsango S. E., Abate L., Thoma M., Pompon J., Fraiture M., Rademacher A., et al. (2012). Genetic clonality of Plasmodium falciparum affects the outcome of infection in Anopheles gambiae. Int. J. Parasitol. 42, 589–595. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette N., Broemer M., Aggarwal K., Chen L., Husson M., Reichhart J., et al. (2010). Caspase mediated cleavage, IAP binding and ubiquitination: linking three mechanisms crucial for Drosophila NF-κB signaling. Mol. Cell 37, 172–182. 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.036.Caspase [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramphul U. N., Garver L. S., Molina-Cruz A., Canepa G. E., Barillas-Mury C. (2015). Plasmodium falciparum evades mosquito immunity by disrupting JNK-mediated apoptosis of invaded midgut cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 1273–1280. 10.1073/pnas.1423586112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutschmann S., Kilinc A., Ferrandon D. (2002). Cutting edge: the toll pathway is required for resistance to gram-positive bacterial infections in Drosophila. J. Immunol. 168, 1542–1546. 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider D. S., Jin Y., Morisato D., Anderson K. V. (1994). A processed form of the Spätzle protein defines dorsal-ventral polarity in the Drosophila embryo. Development 120, 1243–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen R., Baltimore D. (1986). Inducibility of κ immunoglobulin enhancer-binding protein NF-κB by a posttranslational mechanism. Cell 47, 921–928. 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90807-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D. K., Wang X., Brown L. J., Chávez A. S. O., Reif K. E., Smith A. A., et al. (2017). Infection-derived lipids elicit an immune deficiency circuit in arthropods. Nat. Commun. 8:14401. 10.1038/ncomms14401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S. W., Kokoza V., Ahmed A., Raikhel A. S. (2002). Characterization of three alternatively spliced isoforms of the Rel/NF-κB transcription factor Relish from the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 9978–9983. 10.1073/pnas.162345999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simões M. L., Dong Y., Hammond A., Hall A., Crisanti A., Nolan T., et al. (2017). The Anopheles FBN9 immune factor mediates Plasmodium species-specific defense through transgenic fat body expression. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 67, 257–265. 10.1016/j.dci.2016.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahar R., Boudin C., Thiery I., Bourgouin C. (2002). Immune response of Anopheles gambiae to the early sporogonic stages of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Embo J. 21, 6673–6680. 10.1093/emboj/cdf664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takehana A., Katsuyama T., Yano T., Oshima Y., Takada H., Aigaki T., et al. (2002). Overexpression of a pattern-recognition receptor, peptidoglycan-recognition protein-LE, activates imd/relish-mediated antibacterial defense and the prophenoloxidase cascade in Drosophila larvae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 13705–13710. 10.1073/pnas.212301199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takehana A., Yano T., Mita S., Kotani A., Oshima Y., Kurata S. (2004). Peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP)-LE and PGRP-LC act synergistically in Drosophila immunity. EMBO J. 23, 4690–4700. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzou P., Ohresser S., Ferrandon D., Capovilla M., Reichhart J. M., Lemaitre B., et al. (2000). Tissue-specific inducible expression of antimicrobial peptide genes in Drosophila surface epithelia. Immunity 13, 737–748. 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00072-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance R. E., Isberg R. R., Portnoy D. A. (2009). Patterns of pathogenesis: discrimination of pathogenic and nonpathogenic microbes by the innate immune system. Cell Host Microbe 6, 10–21. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizioli J., Bulet P., Charlet M., Lowenberger C., Blass C., Muller H. M., et al. (2000). Cloning and analysis of a cecropin gene from the malaria vector mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Insect. Mol. Biol. 9, 75–84. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00164.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizioli J., Bulet P., Hoffmann J. A., Kafatos F. C., Müller H.-M., Dimopoulos G. (2001a). Gambicin: a novel immune responsive antimicrobial peptide from the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12630–12635. 10.1073/pnas.221466798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizioli J., Richman A. M., Uttenweiler-Joseph S., Blass C., Bulet P. (2001b). The defensin peptide of the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae: antimicrobial activities and expression in adult mosquitoes. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 31, 241–248. 10.1016/S0965-1748(00)00143-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. P., Anderson K. V. (1998). Regulated nuclear import of Rel proteins in the Drosophila immune response. Nature 392, 93–97. 10.1038/32195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S. C., Liao C. W., Pan R. L., Juang J. L. (2012). Infection-induced intestinal oxidative stress triggers organ-to-organ immunological communication in Drosophila. Cell Host Microbe 11, 410–417. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeaman M. R., Yount N. Y. (2003). Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharmacol. Rev. 55, 27–55. 10.1124/pr.55.1.2.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidman-Rémy A., Hervé M., Poidevin M., Pili-Floury S., Kim M. S., Blanot D., et al. (2006). The Drosophila Amidase PGRP-LB Modulates the Immune Response to Bacterial Infection. Immunity 24, 463–473. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]