Abstract

A prospective study was performed of patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC), distinguishing between colonic and rectal location, to determine the factors that may provoke a delay in the first treatment (DFT) provided.

2749 patients diagnosed with CRC were studied. The study population was recruited between June 2010 and December 2012. DFT is defined as time elapsed between diagnosis and first treatment exceeding 30 days.

Excessive treatment delay was recorded in 65.5% of the cases, and was more prevalent among rectal cancer patients. Independent predictor variables of DFT in colon cancer patients were a low level of education, small tumour, ex-smoker, asymptomatic at diagnosis and following the application of screening. Among rectal cancer patients, the corresponding factors were primary school education and being asymptomatic.

We conclude that treatment delay in CRC patients is affected not only by clinicopathological factors, but also by sociocultural ones. Greater attention should be paid by the healthcare provider to social groups with less formal education, in order to optimise treatment attention.

Keywords: colorectal, cancer, delay, treatment, education

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major public health problem, with major impact on morbidity and mortality. It is the second most prevalent malignancy worldwide, and is also second in incidence and mortality in most developed countries. In Europe, five-year survival rates are 44-64%, and in Spain the EUROCARE-4 project calculated a survival rate of 61.5% [1]. As a result of population aging, together with diagnostic and therapeutic advances, the number of cancer patients has increased significantly, and this situation is placing great pressure on the cancer care system, reflecting the growing importance of this group of diseases as a public health problem.

Early diagnosis of cancer and hence early treatment is a fundamental objective in cancer care procedures. Although delays attributable to the health system constitute a small proportion of the biological life of a tumour, noticeable hospital delay (from first hospital visit to diagnosis or from diagnosis to treatment) may provoke stress and decrease the patient's quality of life. In fact, delays in initiating treatment are the leading cause of malpractice complaints [2].

While some studies indicate that treatment delay negatively affects the prognosis of patients with cancer, particularly CRC, others have found no such association [3, 4]. Moreover, it has been reported that delay is often attributable to tumour factors such as clinical stage and location, and not only to the health system, such as hospital admission procedures. The impact of treatment delay on survival, and the significance of the diverse factors involved, have yet to be determined [5]. Waiting time is a complex variable, which can reflect the patient's own behaviour, the clinical course, the functioning of the health system and tumour biology [6].

Taking into account the dearth of prospective studies designed to analyse treatment delay, with large cohorts of patients and distinguishing between colonic and rectal tumours, in this study we evaluate the degree to which treatment delay is influenced by the sociodemographic conditions of patients and by the clinical and pathological characteristics of the tumour.

RESULTS

Descriptive analysis

During the recruitment period, the 22 participating centres recruited 2,749 patients who met the criteria for inclusion. Of these, 330 (12%) were later excluded from the study because it was not possible to determine the treatment delay. Thus, the final patient sample was composed of 2,419 records. The sociodemographic and clinicopathological characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics for all cases and segmented by type of tumour.

| Total | Colon | Rectal | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 1539 | 63.6 | 1092 | 62.2 | 447 | 67.3 | 0.023 |

| Female | 880 | 36.4 | 663 | 37.8 | 217 | 32.7 | |

| Age | |||||||

| Mean - SD | 68.3 | ±10.9 | 68.8 | ±10.8 | 66.9 | ±11.0 | <0.001 |

| Marital status1 | |||||||

| Single | 150 | 7.6 | 100 | 6.9 | 50 | 9.1 | 0.048 |

| Married-Cohabiting | 1434 | 72.2 | 1028 | 71.4 | 406 | 74.2 | |

| Separated-Divorced | 100 | 5.0 | 76 | 5.3 | 24 | 4.4 | |

| Widowed | 302 | 15.2 | 235 | 16.3 | 67 | 12.2 | |

| Education profile2 | |||||||

| No education-Primary education | 1531 | 77.2 | 1114 | 77.1 | 417 | 77.2 | 1.000 |

| Secondary-University | 453 | 22.8 | 330 | 22.9 | 123 | 22.8 | |

| Currently in work3 | |||||||

| No | 1493 | 76.3 | 1072 | 75.3 | 421 | 78.7 | 0.135 |

| Yes | 465 | 23.7 | 351 | 24.7 | 114 | 21.3 | |

| BMI4 | |||||||

| Mean - SD | 27.7 | ±4.8 | 28.0 | ±4.9 | 27.1 | ±4.5 | <0.001 |

| Smoking habit5 | |||||||

| Never | 1109 | 47.8 | 831 | 49.6 | 278 | 43.3 | 0.008 |

| Current smoker | 302 | 13.0 | 201 | 12.0 | 101 | 15.7 | |

| Ex-smoker | 908 | 39.2 | 645 | 38.5 | 263 | 41.0 | |

| Family history of neoplasias6 | |||||||

| No | 1339 | 61.3 | 990 | 63.1 | 349 | 56.7 | 0.007 |

| Yes | 846 | 38.7 | 580 | 36.9 | 266 | 43.3 | |

| Family history of CRC7 | |||||||

| No | 1295 | 86.2 | 934 | 86.3 | 361 | 85.7 | 0.837 |

| Yes | 208 | 13.8 | 148 | 13.7 | 60 | 14.3 | |

| Specific signs and symptoms8 | |||||||

| Asymptomatic | 204 | 8.8 | 160 | 9.6 | 44 | 6.9 | <0.001 |

| Moderate signs and symptoms | 381 | 16.5 | 300 | 18.0 | 81 | 12.6 | |

| Severe signs and symptoms | 1724 | 74.7 | 1207 | 72.4 | 517 | 80.5 | |

| Type of tumour | |||||||

| Colon | 1755 | 72.6 | |||||

| Recto | 664 | 27.4 | |||||

| Size of tumour9 | |||||||

| Locally small (T0-T1-T2) | 681 | 28.8 | 376 | 21.9 | 305 | 47.0 | <0.001 |

| Locally large (T3-T4) | 1686 | 71.2 | 1342 | 78.1 | 344 | 53.0 | |

| Lymph nodes10 | |||||||

| Absent | 1464 | 62.7 | 1028 | 60.0 | 436 | 70.1 | <0.001 |

| Present | 871 | 37.3 | 685 | 40.0 | 186 | 29.9 | |

| Histological diagnosis11 | |||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 2152 | 89.6 | 1555 | 89.0 | 597 | 91.3 | 0.121 |

| Mucinous carcinoma or other types | 249 | 10.4 | 192 | 11.0 | 57 | 8.7 | |

| Metastasis12 | |||||||

| Absent | 2057 | 91.9 | 1483 | 91.2 | 574 | 93.8 | 0.056 |

| Present | 181 | 8.1 | 143 | 8.8 | 38 | 6.2 | |

| Differentiation13 | |||||||

| Low grade | 1790 | 86.9 | 1333 | 86.4 | 457 | 88.2 | 0.336 |

| High grade | 270 | 13.1 | 209 | 13.6 | 61 | 11.8 | |

| Vascular invasion14 | |||||||

| Absent | 1764 | 86.4 | 1259 | 84.4 | 505 | 92.0 | <0.001 |

| Present | 277 | 13.6 | 233 | 15.6 | 44 | 8.0 | |

| Perineural invasion15 | |||||||

| Absent | 1627 | 81.4 | 1165 | 80.1 | 462 | 84.8 | 0.019 |

| Present | 373 | 18.7 | 290 | 19.9 | 83 | 15.2 | |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)16 | |||||||

| Normal (0-5) | 1328 | 68.7 | 917 | 67.5 | 411 | 71.6 | 0.083 |

| Abnormal (>5) | 605 | 31.3 | 442 | 32.5 | 163 | 28.4 | |

| Cancer antigen 19-917 | |||||||

| Normal (1-37) | 944 | 85.4 | 620 | 84.1 | 324 | 88.0 | 0.099 |

| Abnormal (>37) | 161 | 14.6 | 117 | 15.9 | 44 | 12.0 | |

| Prior screening18 | |||||||

| No | 1868 | 80.8 | 1330 | 79.1 | 538 | 85.4 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 443 | 19.2 | 351 | 20.9 | 92 | 14.6 | |

Losses: 1=433; 2=435; 3=461; 4=552; 5=100; 6=234; 7=916; 8=110.

Losses: 9=52; 10=84; 11=18; 12=181; 13=359; 14=378; 15=419; 16=486; 17=1314; 18=108

Treatment delays and types of treatment

For all tumours, the most common initial treatment was surgery (81.4%), followed by chemotherapy (13%) (p<0.001). For rectal tumours alone, surgery and chemotherapy were also the most common treatment options (40.5% and 39.5%, respectively).

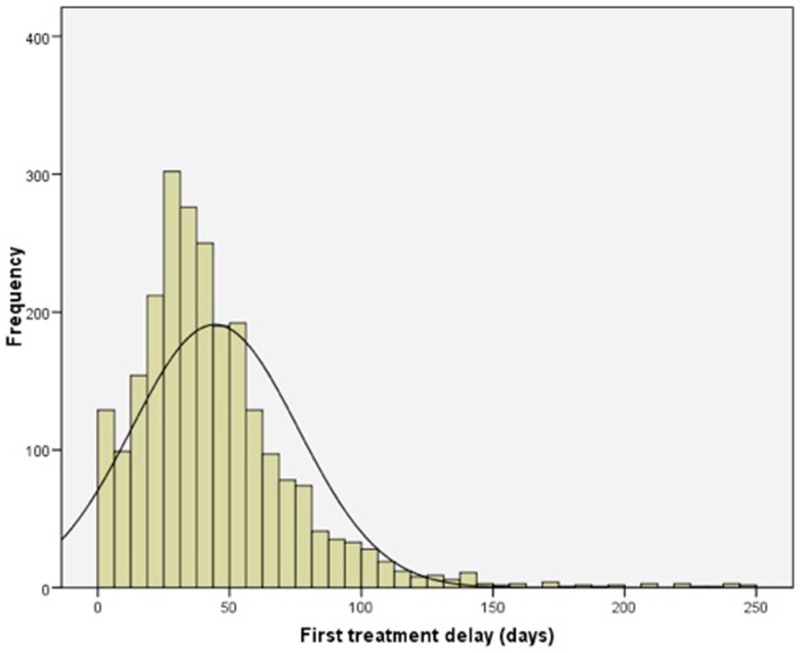

A histogram showing the distribution of treatment delay is shown in Figure 1. A delay to first treatment exceeding 30 days was recorded in 65.5% of cases [95% CI: 63.6-67.4], and this value was higher (p<0.001) for rectal tumours (74.4%) than for colon tumours (62.2%) (Table 2). Stratifying according to the first mode of treatment administered and by tumour location, there was a higher frequency of delay for surgical treatment for rectal tumours than for colon tumours (79.2% vs. 62.2%) (p<0.001). No significant differences were observed for the other treatment strategies.

Figure 1. Frequency histogram of delay (in days) to first treatment for patients with CRC.

Table 2. Type of first treatment and delays.

| Total | Colon | Rectal | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| First line of treatment | |||||||

| Surgery | 1968 | 81.4 | 1699 | 96.8 | 269 | 40.5 | <0.001 |

| Chemotherapy1 | 314 | 13.0 | 52 | 3.0 | 262 | 39.5 | |

| Radiotherapy | 137 | 5.7 | 4 | 0.2 | 133 | 20.0 | |

| Delay in first treatment | |||||||

| ≤30 days | 834 | 34.5 | 664 | 37.8 | 170 | 25.6 | <0.001 |

| >30 days | 1585 | 65.5 | 1091 | 62.2 | 494 | 74.4 | |

| Delay before surgery | |||||||

| ≤30 days | 699 | 35.5 | 643 | 37.8 | 56 | 20.8 | <0.001 |

| >30 days | 1269 | 64.5 | 1056 | 62.2 | 213 | 79.2 | |

| Delay before chemotherapy | |||||||

| ≤30 days | 96 | 30.6 | 20 | 38.5 | 76 | 29.0 | 0.235 |

| >30 days | 218 | 69.4 | 32 | 61.5 | 186 | 71.0 | |

| Delay before radiotherapy | |||||||

| ≤30 days | 39 | 28.5 | 1 | 25.0 | 38 | 28.6 | 1.000 |

| >30 days | 98 | 71.5 | 3 | 75.0 | 95 | 71.4 | |

1 With or without radiotherapy

Relation between treatment delay and the patients’ sociodemographic and clinicopathological characteristics

In our analysis of the relation between the presence of DFT and each of the sociodemographic variables, those that were significantly associated with greater DFT in patients with cancer of the colon were male sex, low level of education or no formal education, BMI (28±5.1), ex-smoker and asymptomatic at diagnosis. The most relevant tumour characteristics were small local extension and the absence of nodes, of metastasis and of perineural invasion. Treatment delays in patients with tumours presenting normal values for carcinoembryonic antigen and for cancer antigen 19-9 were greater than among patients presenting abnormal values for these parameters. Finally, the treatment delay in patients who had received prior screening was greater than among those who had not had this test (Table 3). For rectal tumours, the variables that were significantly related to a higher level of DFT were primary studies or no formal education, being asymptomatic and having had prior screening (Table 4).

Table 3. Bivariate and multivariate analysis with DFT in patients with colon cancer.

| ≤30 days | >30 days | Crude analysis | Adjusted analysis* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | p | OR 95% CI | p | OR 95% CI | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 393 | 36.0 | 699 | 64.0 | 0.041 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 271 | 40.9 | 392 | 59.1 | 0.81 [0.67-0.99] | |||

| Age | ||||||||

| Mean - SD | 68.8 | ±11.3 | 68.8 | ±10.4 | 0.915 | 1.00 [0.99-1.01] | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 38 | 38.0 | 62 | 62.0 | 0.182 | 1.00 | ||

| Married-Cohabiting | 374 | 36.4 | 654 | 63.6 | 1.07 [0.70-1.64] | |||

| Separated-Divorced | 21 | 27.6 | 55 | 72.4 | 1.60 [0.84-3.06] | |||

| Widowed | 97 | 41.3 | 138 | 58.7 | 0.87 [0.54-1.41] | |||

| Education profile | ||||||||

| No education-Primary education | 388 | 34.8 | 726 | 65.2 | 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.008 | 1.00 |

| Secondary-University | 148 | 44.8 | 182 | 55.2 | 0.66 [0.51-0.84] | 0.69[0.52-0.91] | ||

| Currently in work | ||||||||

| No | 396 | 36.9 | 676 | 63.1 | 0.482 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 137 | 39.0 | 214 | 61.0 | 0.91 [0.71-1.17] | |||

| BMI | ||||||||

| Mean - SD | 27.2 | ±4.4 | 28.4 | ±5.1 | <0.001 | 1.06 [1.03-1.08] | ||

| Smoking habit | ||||||||

| Never | 332 | 40.0 | 499 | 60.0 | 0.017 | 1.00 | 0.028 | 1.00 |

| Current smoker | 83 | 41.3 | 118 | 58.7 | 0.95 [0.69-1.29] | 1.08[0.74-1.57] | ||

| Ex-smoker | 215 | 33.3 | 430 | 66.7 | 1.33 [1.07-1.65] | 1.40[1.09-1.80] | ||

| Family history of neoplasias | ||||||||

| No | 374 | 37.8 | 616 | 62.2 | 0.952 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 220 | 37.9 | 360 | 62.1 | 0.99[0.80-1.23] | |||

| Family history of CRC | ||||||||

| No | 323 | 34.6 | 611 | 65.4 | 0.212 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 59 | 39.9 | 89 | 60.1 | 0.80[0.56-1.14] | |||

| Specific signs and symptoms | ||||||||

| Asymptomatic | 40 | 25.0 | 120 | 75.0 | <0.001 | 1.00 | ||

| Moderate signs and symptoms | 132 | 44.0 | 168 | 56.0 | 0.42[0.28-0.65] | |||

| Severe signs and symptoms | 466 | 38.6 | 741 | 61.4 | 0.53[0.36-0.77] | |||

| Size of tumour | ||||||||

| Locally small (T0-T1-T2) | 96 | 25.5 | 280 | 74.5 | <0.001 | 1.00 | <0.001 | 1.00 |

| Locally large (T3-T4) | 555 | 41.4 | 787 | 58.6 | 0.49[0.37-0.63] | 0.51[0.37-0.69] | ||

| Lymph nodes | ||||||||

| Absent | 365 | 35.5 | 663 | 64.5 | 0.015 | 1.00 | ||

| Present | 283 | 41.3 | 402 | 58.7 | 0.78[0.64-0.95] | |||

| Histological diagnosis | ||||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 585 | 37.6 | 970 | 62.4 | 0.597 | 1.00 | ||

| Mucinous carcinoma | 76 | 39.6 | 116 | 60.4 | 0.92[0.68-1.25] | |||

| Metastasis | ||||||||

| Absent | 523 | 35.3 | 960 | 64.7 | 0.037 | 1.00 | ||

| Present | 63 | 44.1 | 80 | 55.9 | 0.69[0.49-0.98] | |||

| Differentiation | ||||||||

| Low grade | 490 | 36.8 | 843 | 63.2 | 0.223 | 1.00 | ||

| High grade | 86 | 41.1 | 123 | 58.9 | 0.83[0.62-1.12] | |||

| Vascular invasion | ||||||||

| Absent | 475 | 37.7 | 784 | 62.3 | 0.212 | 1.00 | ||

| Present | 98 | 42.1 | 135 | 57.9 | 0.83[0.63-1.11] | |||

| Perineural invasion | ||||||||

| Absent | 426 | 36.6 | 739 | 63.4 | 0.001 | 1.00 | ||

| Present | 137 | 47.2 | 153 | 52.8 | 0.64[0.50-0.83] | |||

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) | ||||||||

| Normal (0-5) | 324 | 35.3 | 593 | 64.7 | 0.010 | 1.00 | ||

| Abnormal (>5) | 188 | 42.5 | 254 | 57.5 | 0.74[0.58-0.93] | |||

| Cancer antigen 19-9 | ||||||||

| Normal (1-37) | 219 | 35.3 | 401 | 64.7 | 0.011 | 1.00 | ||

| Abnormal (>37) | 56 | 47.9 | 61 | 52.1 | 0.59[0.40-0.89] | |||

| Prior screening | ||||||||

| No | 547 | 41.1 | 783 | 58.9 | <0.001 | 1.00 | <0.001 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 89 | 25.4 | 262 | 74.6 | 2.06[1.59-2.68] | 1.79[1.32-2.43] | ||

| First line of treatment | ||||||||

| Surgery | 643 | 37.8 | 1056 | 62.2 | 0.869 | 1.00 | ||

| Chemotherapy | 20 | 38.5 | 32 | 61.5 | 0.97[0.55-1.72] | |||

| Radiotherapy | 1 | 25.0 | 3 | 75.0 | 1.83[0.19-17.6] | |||

* In multivariate logistic regression with a sample of 1,291 patients

Table 4. Bivariate and multivariate analysis with DFT in patients with rectal cancer.

| ≤30 days | >30 days | Crude analysis | Adjusted analysis* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | p | OR95% CI | p | OR95% CI | p | OR95% CI | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 109 | 24.4 | 338 | 75.6 | 0.303 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 61 | 28.1 | 156 | 71.9 | 0.82[0.57-1.19] | |||

| Age | ||||||||

| Mean - SD | 65.9 | ±11.2 | 67.2 | ±11.0 | 0.168 | 1.01[0.99-1.03] | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 9 | 18.0 | 41 | 82.0 | 0.145 | 1.00 | ||

| Married-Cohabiting | 111 | 27.3 | 295 | 72.7 | 0.58[0.27-1.24] | |||

| Separated-Divorced | 2 | 8.3 | 22 | 91.7 | 2.41[0.48-12.17] | |||

| Widowed | 18 | 26.9 | 49 | 73.1 | 0.60[0.24-1.47] | |||

| Education profile | ||||||||

| No education-Primary education | 97 | 23.3 | 320 | 76.7 | 0.025 | 1.00 | 0.020 | 1.00 |

| Secondary-University | 41 | 33.3 | 82 | 66.7 | 0.61[0.39-0.94] | 0.56[0.34-0.91] | ||

| Currently in work | ||||||||

| No | 107 | 25.4 | 314 | 74.6 | 0.845 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 30 | 26.3 | 84 | 73.7 | 0.95[0.60-1.53] | |||

| BMI | ||||||||

| Mean - SD | 26.9 | ±4.1 | 27.1 | ±4.7 | 0.699 | 1.01[0.96-1.05] | ||

| Smoking habit | ||||||||

| Never | 71 | 25.5 | 207 | 74.5 | 0.989 | 1.00 | ||

| Current smoker | 26 | 25.7 | 75 | 74.3 | 0.99[0.59-1.67] | |||

| Ex-smoker | 66 | 25.1 | 197 | 74.9 | 1.02[0.69-1.51] | |||

| Family history of neoplasias | ||||||||

| No | 88 | 25.2 | 261 | 74.8 | 0.757 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 70 | 26.3 | 196 | 73.7 | 0.94[0.66-1.36] | |||

| Family history of CRC | ||||||||

| No | 91 | 25.2 | 270 | 74.8 | 0.386 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 12 | 20.0 | 48 | 80.0 | 1.35[0.87-2.65] | |||

| Specific signs and symptoms | ||||||||

| Asymptomatic | 4 | 9.1 | 40 | 90.9 | 0.009 | 1.00 | 0.031 | 1.00 |

| Moderate signs and symptoms | 15 | 18.5 | 66 | 81.5 | 0.44[0.14-1.42] | 0.67[0.16-2.74] | ||

| Severe signs and symptoms | 146 | 28.2 | 371 | 71.8 | 0.25(0.09-0.72) | 0.31[0.09-1.07] | ||

| Size of tumour | ||||||||

| Locally small (T0-T1-T2) | 78 | 25.6 | 227 | 74.4 | 0.998 | 1.00 | ||

| Locally large (T3-T4) | 88 | 25.6 | 256 | 74.4 | 1.00[0.70-1.42] | |||

| Lymph nodes | ||||||||

| Absent | 116 | 26.6 | 320 | 73.4 | 0.292 | 1.00 | ||

| Present | 42 | 22.6 | 144 | 77.4 | 1.42[0.83-1.86] | |||

| Histological diagnosis | ||||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 152 | 25.5 | 445 | 74.5 | 0.660 | 1.00 | ||

| Mucinous carcinoma | 13 | 22.8 | 44 | 77.2 | 1.16[0.61-2.20] | |||

| Metastasis | ||||||||

| Absent | 138 | 24.0 | 436 | 76.0 | 0.751 | 1.00 | ||

| Present | 10 | 26.3 | 28 | 73.7 | 0.89[0.42-1.87] | |||

| Differentiation | ||||||||

| Low grade | 106 | 23.2 | 351 | 76.8 | 0.175 | 1.00 | ||

| High grade | 19 | 31.1 | 42 | 68.9 | 0.67[0.37-1.20] | |||

| Vascular invasion | ||||||||

| Absent | 127 | 25.1 | 378 | 74.9 | 0.490 | 1.00 | ||

| Present | 9 | 20.5 | 35 | 79.5 | 1.31[0.61-2.79] | |||

| Perineural invasion | ||||||||

| Absent | 112 | 24.2 | 350 | 75.8 | 0.042 | 1.00 | 0.051 | 1.00 |

| Present | 29 | 34.9 | 54 | 65.1 | 0.60[0.36-0.98] | 0.57[0.32-1.00] | ||

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) | ||||||||

| Normal (0-5) | 105 | 25.5 | 306 | 74.5 | 0.722 | 1.00 | ||

| Abnormal (>5) | 44 | 27.0 | 119 | 73.0 | 0.93[0.61-1.40] | |||

| Cancer antigen 19-9 | ||||||||

| Normal [1−37] | 70 | 21.6 | 254 | 78.4 | 0.133 | 1.00 | ||

| Abnormal [>37] | 14 | 31.8 | 30 | 68.2 | 0.59[0.30-1.17] | |||

| Prior screening | ||||||||

| No | 148 | 27.5 | 390 | 72.5 | 0.025 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 15 | 16.3 | 77 | 83.7 | 1.95[1.09-3.49] | |||

| First line of treatment | ||||||||

| Surgery | 56 | 20.8 | 213 | 79.2 | 0.067 | 1.00 | ||

| Chemotherapy | 76 | 29.0 | 186 | 71.0 | 0.64[0.43-0.96] | |||

| Radiotherapy | 38 | 28.6 | 95 | 71.4 | 0.66[0.41-1.06] | |||

* In multivariate logistic regression with a sample of 433 patients

After adjusting for variables found to be statistically significant in the crude analysis, the multivariate analysis revealed the following to be independent protective factors against increased DFT: having university studies, for colon cancer [OR = 0.69; 95% CI 0.52-0.91] and for rectal cancer [OR = 0.56; 95% CI 0.34-0.91]; later tumour stage, for colon tumours, T3-T4, [OR = 0.51; 95% CI 0.37-0.69]; and for rectal tumours, the presence of severe [OR = 0.31; 95% CI 0.09-1.07] or moderate symptoms [OR = 0.67; 95% CI 0.16-2.74], compared with asymptomatic patients. However, DFT was greater in the patients with colon cancer who were ex-smokers [OR = 1.40; 95% CI 1.09-1.80] and in those who had had prior screening [OR = 1.79; 95% CI: 1.32-2.43] (Tables 3 and 4).

DISCUSSION

Our study highlights the existence of delayed implementation of the first treatment among 65.5% of the population diagnosed with CRC. This finding lies within the 40-70% range of treatment delay previously reported [7].

Studies have been conducted to evaluate the prognostic influence of diagnostic and treatment delays on different types of cancer, and to determine the significant factors in this process. However, conflicting results have been obtained, due in part to differences in the characteristics of the populations analysed; furthermore, in most cases, the cohorts have been examined retrospectively and there have been differences in the time intervals studied [8]. This is a controversial issue, and it remains to be clarified. Unlike these earlier studies, our own research is based on a large number of patients recruited prospectively. We define excessive delay between diagnosis and treatment as a period exceeding 30 days, following previous recommendations and reports in this respect [9, 10, 11, 12, 13]

Unlike other studies on diagnostic and treatment delays in patients with CRC, our study population is distributed according to the location of the tumour (colon or rectal), in view of the well-known differences in the pathogenesis of each. We found DFT to be significantly greater for rectal tumours, as was also reported in the case of delay attributable to the patient [14]. Analysis of the delay according to the type of first treatment applied showed that this difference persisted when the first treatment was surgery, but not when it was chemotherapy or radiotherapy. This association is consistent with the findings of other studies, which have related the delay in surgical treatment for advanced stage (according to the Dukes system) rectal tumours, but not for tumours of the colon [15], probably because in localised and locally-advanced rectal tumours, and unlike for colon cancer, other diagnostic tests are required prior to treatment, such as pelvic magnetic resonance imaging and rectal endoscopic ultrasound examination [16]. Another difference between the two types of cancer was the relationship between DFT and the digestive symptoms diagnosed; a shorter DFT was only observed in patients with rectal cancer and moderate to severe symptoms, compared with mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic patients. Possibly the more pronounced and alarming symptoms resulting from rectal tumours, i.e. bleeding and pain, compared to the less specific and subacute ones provoked by colon tumours, lead patients with rectal cancer to seek a medical consultation at an earlier stage, thus expediting the diagnostic-therapeutic circuit. The physician prescribing the treatment will probably give preference to symptomatic patients, who are at increased risk of presenting complications from the tumour and therefore have a worse prognosis. It should also be taken into account that some patients with advanced tumours do not state the actual date of onset of their symptoms, or minimise it, due to a feeling of guilt at not having consulted the doctor sooner, and this too can exacerbate the DFT [17–19].

Studies of CRC have evaluated the relationship between tumour stage and diagnostic and therapeutic delays, and have found no association between these parameters [20]. Although some studies have shown that the DFT is shorter for patients presenting advanced stages of the disease [21], others have concluded the opposite [22]. Nevertheless, these conclusions cannot be generalised for tumours of the colon and rectum as if they were a single entity; on the contrary, they must be analysed independently, in view of the different natural history presented in each case [23, 24]. Thus, some retrospective studies have shown that advanced rectal tumours present an increased risk of DFT, in comparison with the initial stages, while no such differences were found for cancers of the colon [15]. On the other hand, in our own study, tumour stages T1-T2 experienced greater DFT than more advanced stages, but only in tumours of the colon. This difference might arise from the lower priority assigned to treatment for early-stage cancers, when symptoms are usually less apparent and hence delay the start of the therapeutic process. In a study of breast cancer, our group evaluated the different periods of delay, noting that higher tumour stages were associated with a shorter DFT, which was associated with a lower disease-free survival time. This outcome is probably produced by the priority granted by doctors to patients whose symptoms are more severe [6], which contradicts the traditional view that greater delay is associated with decreased survival time. This inverse correlation between treatment delay and survival has been described previously in studies of the endometrium and the lung [22, 25].

In our analysis of clinicopathological characteristics with known prognostic value and associated with increased tumour aggressiveness, the degree of histological differentiation and of lymphovascular invasion presented no relation to DFT. However, they were found to be related to distant metastases, lymph node involvement, perineural invasion and elevated tumour markers, all of which decrease the risk of severe DFT. However, when a multivariate analysis was performed, and other variables were taken into account, these differences did not persist, probably because the variables in question are more dependent on the biological behaviour of the tumour and on its intrinsic aggressiveness than on the period of treatment delay, as suggested by Symonds in a study of cervical cancer [26]. In other tumours, such as breast cancer, a significant association has also been described between the presence of more aggressive features and a shorter delay in initiating treatment; such features may include the non expression of hormone receptors, or non response to hormonal treatments in tumours that do express hormone receptors. These findings suggest that treatment may be expedited when the physician is aware of the extent of the tumour [6].

Among the sociocultural factors analysed, the lack of formal education or only having had primary education significantly increases the risk of DFT, for both rectal and colon tumours. Interestingly, this association, which has not received much previous research attention, influences DFT independently of other factors. One explanation for this might be that these patients do not understand the instructions received during the diagnosis-therapy process, and may also fail to keep the medical appointments necessary for a definitive tumour treatment to be undertaken. This population group, with a low cultural level, might also delay the start of treatment for fear of future treatments and distrust of the benefit derived from them. This possibility was raised in a recent study in which DFT was associated with a lack of knowledge of symptoms suggestive of cancer, and with the patient's unwillingness to visit the doctor, among other factors [27]. For these reasons, we believe that among certain population groups, with unhealthy living habits and a low educational profile, the risk of severe DFT is greater. In this respect, a retrospective study was conducted to obtain an ecological estimation of the socioeconomic status of patients with cancer (European Deprivation Index). No such relationship with DFT or with diagnostic delay was found, although it should be noted that this study included different types of cancer, with only 116 CRC [28].

Retrospective studies have evaluated social factors that might influence treatment delay, noting that black and/or elderly patients with rectal cancer were subject to greatest delay in initiating adjuvant chemotherapy [29]. In another study, of bowel cancer [30], elderly and/or unmarried patients were found to be most subject to this delay. Other studies evaluating prehospital delay have also found that lower socioeconomic level and lower education level are relevant factors. [14, 31].

Another feature of our population which the univariate analysis showed to be associated with increased treatment delay was a high BMI (>28) in patients with colon cancer. This relation would be explained, in part, by the complication of abdominal examination in the presence of a large pannus. One of the main causes of obesity in the West is an unhealthy living habit in terms of diet and exercise; this, too, is associated with a low socio-cultural level, which as mentioned previously is an independent predictor of treatment delay. The remaining demographic variables analysed–sex, age at diagnosis, family history of cancer, marital status and occupation–bore no significant relation with DFT.

The relationship between treatment delay and ex-smokers is a complex one. Elderly ex-smokers probably have more limitations of the respiratory function and require a larger number of tests before surgery. On the other hand, a patient who gives up smoking will probably believe him/herself at less risk of serious disease than a continuing smoker, and this factor, too, may influence communication with the doctor after diagnosis. In this respect, Mosher et al., in a study of patients diagnosed with lung cancer, reported that most ex-smokers rejected psychological therapy [32].

Our results show that a prior positive screening, in which faecal occult blood is detected, is associated with a greater risk of treatment delay; this relation has not been reported in previous studies. A priori, it seems illogical that a patient who has received CRC screening before any treatment is undertaken should suffer a delay for this reason. However, probably due to the person's asymptomatic state at the time of the consultation, no preference is expressed (unlike the case of a patient with manifest symptoms and at increased risk of complications from the tumour, requiring prompt treatment). Nevertheless, we considered the possible existence of confounding and of interaction with the other variables, and always obtained the same relationship between prior screening and subsequent treatment delay. Neither were there any interaction terms to be retained in the final model (data not shown).

Although it has been shown that delayed diagnosis and treatment does not appear to increase the risk of death in patients with symptomatic CRC, among the asymptomatic population early diagnosis and treatment may play a role in reducing morbidity and mortality [33]. The results presented should be considered with caution, and are subject to further analysis to determine whether, in the screened population, the greater delay observed impacts on survival.

The delay before cancer treatment is started is an important factor to be evaluated. This delay, which is a criterion of health care quality, should be prevented and reduced as far as possible in order to avoid the psychologically negative impact it may cause to patients. Numerous studies have shown that treatment delay is associated with certain clinical factors in CRC, but the present study is the first to establish that DFT depends not only on clinicopathological characteristics of the tumour, or on deficiencies of the healthcare system, but also on sociocultural characteristics of the population. We conclude, therefore, that more attention should be paid to health education regarding the initial symptoms related to this disease, especially among less educated social groups. The physician responsible for the patient's treatment, too, must be aware that these patients require special attention.

Finally, more multicentre studies should be conducted, in other countries and where different healthcare plans are used, in order to generalise the findings of our study. Another valuable area for future research would be to determine whether treatment delay also impacts on survival, as this association has not been clarified in recent reviews of the question [6, 34].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This prospective, multicentre observational study was conducted in coordination with 22 public-sector hospitals in six regions of Spain (Andalusia, Canary Islands, Catalonia, Madrid, Valencia and the Basque Country) [35].

The patients were recruited prospectively and consecutively at each of the participating hospitals between June 2010 and December 2012. The study population included patients diagnosed with new colon or rectum cancer, stage I-IV and surgically treated, whether urgently or scheduled. All patients were included, whether or not they had previously received treatment, and a follow up study of five years was scheduled. Data were compiled directly from patients and also from their medical history.

Study definitions

Excessive treatment delay was defined as an interval exceeding 30 days from pathological diagnosis to first treatment, in accordance with national guidelines and previous reports [10–13, 15]. First treatment was taken to be surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, biological therapy or best supportive care. Date of diagnosis was the date when histological confirmation of the process was obtained, unless this coincided with the date of the intervention. In this case, we used as first date of diagnosis the suspected diagnosis [35].

The anatomical location of the tumour and the histology findings were coded in accordance with the International Classification for Oncology (ICD-O). Staging classification was based on the TNM recommendations of the International Union Against Cancer, 7th edition.

The following inclusion criteria were applied:

Patients diagnosed with cancer of the colon (up to 15 cm above the anal margin) or of the rectum (between the anal margin and 15 cm above it), to which curative and/or palliative surgical treatment was applied for the first time.

Signed informed consent provided.

The exclusion criteria were:

Patients diagnosed with cancer of the colon or rectum in situ.

Unresectable tumours.

Mental or physical disorders that prevented the patient from answering the questionnaires.

Terminal patients

The project was evaluated by the corresponding Research Committees and Clinical Research Ethics Committees at the hospitals. Informed consent was requested of the patients before surgery. Current legislative requirements regarding personal data (any information concerning individuals who were identified or identifiable) were followed at all times. All personal data were processed in such a way that the information obtained could not be associated with identified or identifiable persons (Protection of Personal Data Act, 15/1999, 13-12).

Study variables

Data were compiled regarding the patients’ medical history: Sex, age, body mass index, prior screening, date of first contact with the hospital, first diagnosis, start of treatment, and the various types of first treatment considered (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, biological therapy or best supportive care). The date of diagnosis was taken as the date when the first histopathological report identifying the presence of cancer, was issued, except patients treated at the same time as they were diagnosed that we used as first date of diagnosis the suspected diagnosis date. The following laboratory and pathological factors were also recorded: tumour location (rectum or colon), degree of histological differentiation, tumour stage T and lymph node N (determined by the TNM clinical staging system), lymphovascular and perineural invasion, presence of metastasis, status of tumour markers such as carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 and serial carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA). [36]

The following variables were self-reported by the patient: family history of colorectal cancer and other tumors, marital status, occupation at the time of the study, education profile, smoking habit and symptoms prior to surgery, date of onset of symptoms.

Statistical design

A descriptive analysis was performed, with measures of central tendency and dispersion for the quantitative variables and frequency distributions for the qualitative ones. Differences were determined by bivariate analysis, segmenting by type of tumour and by time elapsed to first treatment, using the Student t test for quantitative variables and the chi-square test for qualitative ones. Finally, the treatment delay variable was used to perform a multivariate logistic regression analysis, using the variables with a value of p<0.1, together with the patient's age and sex. The level of statistical significance used in these analyses was p<0.05.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by grants from REDISSEC (RD12/0001/0010), Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (13/0013) and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Author contributions

MR, JMQ and IZ conceived the project. CS, NF, TT, MB, collected all the data. FR and UA did the statistical analyses. IZ wrote the first draft and revised drafts of the manuscript. MR, JMQ, TT, MMMS-V, EB, AE, MB, AR critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

The final version of the manuscript was approved by all the authors.

MR, JMQ, MMMS-V, EB, NF, AE, AF, AR and MB had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. MR is the guarantor for the study

CARESS-CCR Study Group

Jose María Quintana López1, Marisa Baré Mañas2, Maximino Redondo Bautista3, Eduardo Briones Pérez de la Blanca4, Nerea Fernández de Larrea Baz5, Cristina Sarasqueta Eizaguirre6, Antonio Escobar Martínez7, Francisco Rivas Ruiz8, Maria M. Morales-Suárez-Varela9, Juan Antonio Blasco Amaro10, Isabel del Cura González11, Inmaculada Arostegui Madariaga12, Amaia Bilbao González7, Nerea González Hernández1, Susana García-Gutiérrez1, Iratxe Lafuente Guerrero1, Urko Aguirre Larracoechea1, Miren Orive Calzada1, Josune Martin Corral1, Ane Antón-Ladislao1, Núria Torà13, Marina Pont13, María Purificación Martínez del Prado14, Alberto Loizate Totorikaguena15, Ignacio Zabalza Estévez16, José Errasti Alustiza17, Antonio Z Gimeno García18, Santiago Lázaro Aramburu19, Mercè Comas Serrano20, Jose María Enríquez Navascues21, Carlos Placer Galán21, Amaia Perales22, Iñaki Urkidi Valmaña23, Jose María Erro Azkárate24, Enrique Cormenzana Lizarribar25, Adelaida Lacasta Muñoa26, Pep Piera Pibernat26, Elena Campano Cuevas27, Ana Isabel Sotelo Gómez28, Segundo Gómez-Abril29, F. Medina-Cano30, Antonio Rueda31, Julia Alcaide31, Arturo Del Rey-Moreno32, Manuel Jesús Alcántara33, Rafael Campo34, Alex Casalots35, Carles Pericay36, Maria José Gil37, Miquel Pera37, Pablo Collera38, Josep Alfons Espinàs39, Mercedes Martínez40, Mireia Espallargues41, Caridad Almazán42, Paula Dujovne Lindenbaum43, José María Fernández-Cebrián43, Rocío Anula Fernández44, Julio Ángel Mayol Martínez44, Ramón Cantero Cid45, Héctor Guadalajara Labajo46, María Heras Garceau46, Damián García Olmo46, Mariel Morey Montalvo47.

- Unidad de Investigación. Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Galdakao-Bizkaia / Red de Investigación en Servicios de Salud en Enfermedades Crónicas – REDISSEC.

- Epidemiologia Clínica y Cribado de Cancer, Corporació Sanitaria Parc Taulí, Sabadell / Red de Investigación en Servicios de Salud en Enfermedades Crónicas – REDISSEC.

- Servicio de Laboratorio. Hospital Costa del Sol, Málaga / REDISSEC.

- Unidad de Epidemiología. Distrito Sevilla, Servicio Andaluz de Salud.

- Area of Environmental Epidemiology and Cancer. National Epidemiology Centre. Instituto de Salud Carlos III. Consortium for Biomedical Research in Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública, CIBERESP). Madrid. Spain.

- Unidad de Investigación. Hospital Universitario Donostia /Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Biodonostia, Donostia – REDISSEC.

- Unidad de Investigación. Hospital Universitario Basurto, Bilbao / REDISSEC.

- Servicio de Epidemiología. Hospital Costa del Sol, Málaga – REDISSEC.

- Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Univesity of Valencia / CIBER de Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP) / CSISP-FISABIO, Valencia.

- Unidad de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias, Agencia Laín Entralgo, Madrid.

- Unidad Apoyo a Docencia-Investigación. Dirección Técnica Docencia e Investigación. Gerencia Adjunta Planificación. Gerencia de Atención Primaria de la Consejería de Sanidad de la Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid.

- Departamento de Matemática Aplicada, Estadística e Investigación Operativa, UPV- REDISSEC.

- Epidemiologia Clínica y Cribado de Cancer, Corporació Sanitaria Parc Taulí, Sabadell / REDISSEC.

- Servicio de Oncología. Hospital Universitario Basurto, Bilbao.

- Servicio de Cirugía General. Hospital Universitario Basurto, Bilbao.

- Servicio de Anatomía Patológica. Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Galdakao.

- Servicio de Cirugía General. Hospital Universitario Araba, Vitoria-Gasteiz.

- Servicio de Gastroenterología. Hospital Universitario de Canarias, La Laguna.

- Servicio de Cirugía General. Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Galdakao.

- IMAS-Hospital del Mar, Barcelona.

- Servicio de Cirugía General y Digestiva. Hospital Universitario Donostia.

- Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Biodonostia, Donostia.

- Servicio de Cirugía General y Digestiva. Hospital de Mendaro.

- Servicio de Cirugía General y Digestiva. Hospital de Zumárraga.

- Servicio de Cirugía General y Digestiva. Hospital del Bidasoa.

- Servicio de Oncología Médica. Hospital Universitario Donostia.

- Instituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla. Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla.

- Servicio de Cirugía. Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme, Sevilla.

- Servicio de Cirugía General y Aparato Digestivo. Hospital Dr. Pesset, Valencia.

- Servicio de Cirugía General y Aparato Digestivo. Agencia Sanitaria Costa del Sol, Marbella.

- Servicio de Oncología Médica. Agencia Sanitaria Costa del Sol, Marbella.

- Servicio de Cirugía. Hospital de Antequera.

- Coloproctology Unit, General and Digestive Surgery Service, Corporació Sanitaria Parc Taulí, Sabadell.

- Digestive Diseases Department, Corporació Sanitaria Parc Taulí, Sabadell.

- Pathology Service, Corporació Sanitaria Parc Taulí, Sabadell.

- Medical Oncology Department, Corporació Sanitaria Parc Taulí, Sabadell / REDISSEC.

- General and Digestive Surgery Service, Parc de Salut Mar, Barcelona.

- General and Digestive Surgery Service, Althaia- Xarxa Assistencial Universitaria, Manresa.

- Catalonian Cancer Strategy Unit, Department of Health, Institut Català d'Oncología.

- Medical Oncology Department, Institut Català d'Oncología.

- Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia –AquAS- and REDISSEC.

- Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia –AQuAS-, CIBER de Epidemiología y Salud Pública –CIBERESP.

- Servicio de Cirugía General y del Aparato Digestivo, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid.

- Servicio de Cirugía General y Aparato Digestivo, Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos, Madrid.

- Servicio Cirugía General y del Aparato Digestivo, Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía, San Sebastián de los Reyes, Madrid.

- Servicio de Cirugía General y del Aparato Digestivo, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid.

- REDISSEC. Unidad de Apoyo a la Investigación, Gerencia de Atención Primaria de Madrid, Madrid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Verdecchia A, Francisci S, Brenner H, Gatta G, Micheli A, Mangone L, Kunkler I, Group EW. Recent cancer survival in Europe: a 2000-02 period analysis of EUROCARE-4 data. Lancet Oncol. 2007(8):784–796. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews BT, Bates T. Delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer: medico-legal implications. Breast. 2000(9):223–37. doi: 10.1054/brst.1999.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esteva M, Ramos M, Cabeza E, Llobera J, Ruiz A, Pita S, Segura J, Cortes J, Gonzalez-Lujan L, DECCIRE research group Factors influencing delay in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer: a study protocol. BMC Cancer. 2007(7):86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pita Fernández S, Pértega Díaz S, López Calviño B, González Santamaría P, Seoane Pillado T, Arnal Monreal F, Maciá F, Sánchez Calavera MA, Espí Macías A, Valladares Ayerbes M, Pazos A, Reboredo López M, González Saez L, et al. Diagnosis delay and follow-up strategies in colorectal cancer. Prognosis implications: a study protocol. BMC Cancer. 2010(10):6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macià F, Pumarega J, Gallén M, Porta M. Time from (clinical or certainty) diagnosis to treatment onset in cancer patients: the choice of diagnostic date strongly influences differences in therapeutic delay by tumor site and stage. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013(66):928–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redondo M, Rodrigo I, Pereda T, Funez R, Acebal M, Perea-Milla E, Jiménez E. Prognostic implications of emergency admission and delays in patients with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2009(17):595–9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramos M, Esteva M, Cabeza E, Campillo C, Llobera J, Aguiló A. Relationship of diagnostic and therapeutic delay with survival in colorectal cancer: a review. Eur J Cancer. 2007(43):2467–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramos M, Esteva M, Cabeza E, Llobera J, Ruiz A. Lack of association between diagnostic and therapeutic delay and stage of colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008(44):510–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pérez G, Porta M, Borrell C, Casamitjana M, Bonfill X, Bolibar I, Fernández E, INTERCAT Study Group Interval from diagnosis to treatment onset for six major cancers in Catalonia, Spain. Cancer Detect Prev. 2008(32):267–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero Gómez M, Alonso Redondo E, Borrego Dorado I, Briones Pérez de la Blanca E, Campos Rico A, Carlos Gil AM, de las Peñas Cabrera MD, del Río Urend S, Dotor Gracia M, Espinosa Bosch M, Fernández Ávila JJ, Fernández Echegaray R, Galindo Galindo A, et al. Sevilla- Consejería de Salud. 2ª. 2011. Cáncer colorrectal: proceso asistencial integrado. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bleicher RJ, Ruth K, Sigurdson ER, Beck JR, Ross E, Wong YN, Patel SA, Boraas M, Chang EI, Topham NS, Egleston BL. Time to Surgery and Breast Cancer Survival in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2016(2):330–339. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guzman-Laura KP, Bolibar RI, Alepuz MT, Gonzalez D, Martin M. Impact on the care and time to tumor stage of a program of rapid diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2011(103):13–19. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082011000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, Tomlinson JS, Stewart AK, Talamonti MS, Hynes DL, Winchester DP, Bentrem DJ. Wait times for cancer surgery in the United States: trends and predictors of delays. Ann Surg. 2011(253):779–85. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318211cc0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell E, Macdonald S, Campbell NC, Weller D, Macleod U. Influences on pre-hospital delay in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2008(98):60–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korsgaard M, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT, Laurberg S. Treatment delay is associated with advanced stage of rectal cancer but not of colon cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006(30):341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glimelius B, Tiret E, Cervantes A, Arnold D, ESMO Guidelines Working Group Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013(24):vi81–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernández E, Porta M, Malats N, Belloc J, Gallén M. Symptom-to-diagnosis interval and survival in cancers of the digestive tract. Dig Dis Sci. 2002(47):2434–2440. doi: 10.1023/a:1020535304670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curless R, French J, Williams GV, James OF. Comparison of gastrointestinal symptoms in colorectal carcinoma patients and community controls with respect to age. Gut. 1994(35):1267–1270. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.9.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roncoroni L, Pietra N, Violi V, Sarli L, Choua O, Peracchia A. Delay in the diagnosis and outcome of colorectal cancer: a prospective study. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 1999(25):173–178. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1998.0622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramos M, Esteva M, Cabeza E, Llobera J, Ruiz A. Lack of association between diagnostic and therapeutic delay and stage of colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008(44):510–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim IY, Kim BR, Kim YW. Factors Affecting Use and Delay (>/=8 Weeks) of Adjuvant Chemotherapy after Colorectal Cancer Surgery and the Impact of Chemotherapy-Use and Delay on Oncologic Outcomes. PloS one. 2015(10):e0138720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myrdal G, Lambe M, Hillerdal G, Lamberg K, Agustsson T, Stahle E. Effect of delays on prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Thorax. 2004;59:45–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith G, Carey FA, Beattie J, Wilkie MJ, Lightfoot TJ, Coxhead J, Garner RC, Steele RJ, Wolf CR. Mutations in APC, Kirsten-ras, and p53--alternative genetic pathways to colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002(99):9433–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122612899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB, Littlejohns P, Ramirez AJ. Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet. 1999(353):1119–26. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)02143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crawford SC, Davis J A, Siddiqui NA, De_Caestecker L, Gillis CR, Hole D, Penney G. The waiting time paradox: population based retrospective study of treatment delay and survival of women with endometrial cancer in Scotland. BMJ. 2002(325):196. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Symonds P, Bolger B, Hole D, Mao JH, Cooke T. Advanced-stage cervix cancer: rapid tumour growth rather than late diagnosis. British journal of cancer. 2000(83):566. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abu-Helalah MA, Alshraideh HA, Da'na M, Al-Hanaqtah M, Abuseif A, Arqoob K, Ajaj A. Delay in presentation, diagnosis and treatment for colorectal cancer patients in Jordan. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2016(47):36–46. doi: 10.1007/s12029-015-9783-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moriceau G, Bourmaud A, Tinquaut F, Oriol M, Jacquin JP, Fournel P, Magné N, Chauvin F. Social inequalities and cancer: can the European deprivation index predict patients’ difficulties in health care access? a pilot study. Oncotarget. 2015(7):1055–65. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheung WY, Neville BA, Earle CC. Etiology of delays in the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy and their impact on outcomes for Stage II and III rectal cancer. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2009(52):1054–63. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a51173. discussion 64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hershman D, Hall MJ, Wang X, Jacobson JS, McBride R, Grann VR, Neugut AI. Timing of adjuvant chemotherapy initiation after surgery for stage III colon cancer. Cancer. 2006(107):2581–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macleod U, Mitchell ED, Burgess C, MacDonald S, Ramirez AJ. Risk factors for delayed presentation and referral of symptomatic cancer: evidence for common cancers. Br J Cancer. 2009(101):s92–s101. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosher CE, Winger JG, Hanna N, Jalal SI, Fakiris AJ, Einhorn LH, Birdas TJ, Kesler KA, Champion VL. Barriers to mental health service use and preferences for addressing emotional concerns among lung cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2014(23):812–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pruitt SL, Harzke AJ, Davidson NO, Schootman M. Do diagnostic and treatment delays for colorectal cancer increase risk of death? Cancer Causes Control. 2013(24):961–977. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0172-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murchie P, Raja EA, Brewster DH, Campbell NC, Ritchie LD, Robertson R, Samuel L, Gray N, Lee AJ. Time from first presentation in primary care to treatment of symptomatic colorectal cancer: effect on disease stage and survival. Br J Cancer. 2014(111):461–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quintana JM, Gonzalez N, Anton-Ladislao A, Redondo M, Bare M, Fernandez de_Larrea N, Briones E, Escobar A, Sarasqueta C, Garcia-Gutierrez S, Aguirre U, REDISSEC-CARESS/CCR group Colorectal cancer health services research study protocol: the CCR-CARESS observational prospective cohort project. BMC Cancer. 2016(16):435. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2475-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clinical practice guidelines for the use of tumor markers in breast and colorectal cancer. Adopted on May 17, 1996 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 1996(14):2843–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.10.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]