Abstract

Approximately half of patients with heart failure (HF) have preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). There is no proven treatment that improves outcome. The pathophysiology of HFpEF is complex and includes left ventricular (LV) systolic and diastolic dysfunction, pulmonary vascular disease, endothelial dysfunction, and peripheral abnormalities. Multiple lines of evidence point to impaired nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (NO-cGMP) bioavailability as playing a central role in each of these abnormalities. In contrast to traditional organic nitrate therapies, an alternative strategy to restore NO-cGMP signaling is via inorganic nitrite. Inorganic nitrite, previously considered to be an inert byproduct of NO metabolism, functions as an important in vivo reservoir for NO generation, particularly under hypoxic and acidemic conditions. As such, inorganic nitrite becomes most active at times of greater need for NO signaling, as during exercise when LV filling pressures and pulmonary artery pressures increase. Herein, we present the rationale and design for the Inorganic Nitrite Delivery to Improve Exercise Capacity in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (INDIE-HFpEF) trial, which is a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled crossover study assessing the effect of inhaled inorganic nitrite on peak exercise capacity, conducted in the NHLBI-sponsored Heart Failure Clinical Research Network.

Clinical Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov; NCT02742129

Keywords: Heart Failure, Exercise, Clinical Trial, Nitric Oxide, HFpEF

Treatment for HFpEF is an Unmet Public Health Need

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) currently represents about half of all patients with heart failure.1 As the world's population ages and comorbidities associated with HFpEF become increasingly common, the prevalence is expected to continue to grow. Clinical trials performed to date have failed to identify an effective pharmacologic treatment for HFpEF.1, 2 Exercise intolerance, manifest by dyspnea, fatigue, and depressed aerobic capacity, is the cardinal symptomatic manifestation of HFpEF. Novel treatments that can improve exercise capacity in HFpEF are therefore urgently needed.

Pathophysiology of HFpEF

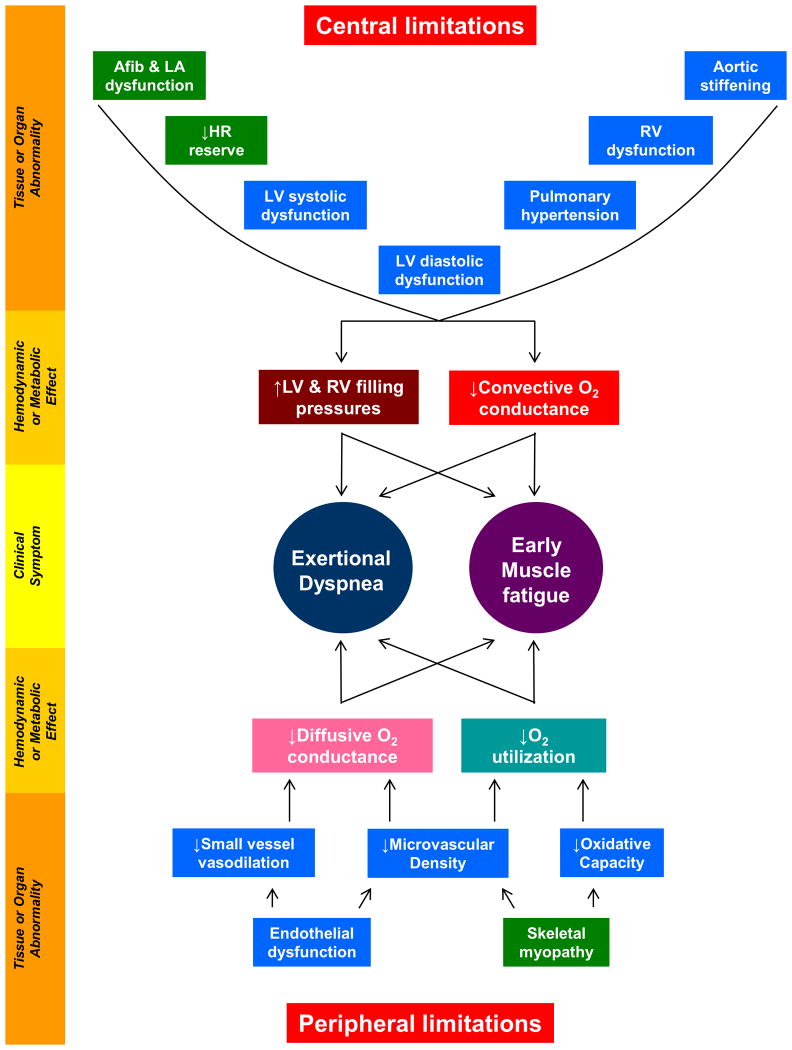

he pathophysiology of HFpEF is complex; abnormalities in left ventricular (LV) diastolic and systolic function, chronotropic incompetence, arterial stiffening, endothelial dysfunction, depressed vasodilator reserve, impaired right ventricular (RV)-pulmonary artery (PA) coupling, atrial dysfunction, and abnormalities in skeletal muscle have all been related to the HFpEF syndrome (Figure 1).3, 4 The extent to which these abnormalities exist in a given patient may vary, which complicates targeting of treatment. Exercise capacity is constrained in some HFpEF patients predominantly by central (cardiac) limitations,5-8 whereas in others the major limitation appears to reside in skeletal muscle and systemic vasculature (Figure 1).9-11

Figure 1. Pathophysiology of HFpEF.

Symptoms of dyspnea and fatigue in HFpEF originate from hemodynamic and metabolic perturbations that are both central and peripheral. Central limitations exist in the heart and great arteries and cause elevation in cardiac filling pressures and limited increases in cardiac output with exertion (decreased convective O2 conductance). Peripheral limitations exist in the peripheral vasculature and skeletal muscle and lead to impaired O2 delivery (diffusive O2 conductance) and utilization in the tissues. Tissue/organ-level abnormalities that are present in HFpEF patients that are expected to targeted/ameliorated with nitrite are colored in blue. Afib, atrial fibrillation; LA, left atrial; HR, heart rate; LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular.

Despite this pathophysiologic heterogeneity, elevation in LV filling pressures during exercise represents a unifying pathophysiologic mechanism that limits exercise tolerance, contributes to increased morbidity and mortality, and serves as a credible therapeutic target.8, 12-14 In patients with advanced HFpEF, LV filling pressures are high at rest and during exercise, but in earlier stage HFpEF patients, they become elevated only during the stress of exercise.5, 12, 15 Indeed, abnormalities in stress reserve during exercise, which are present in both ventricles, the systemic and pulmonary circulations, and in the peripheral tissues (Figure 1), are pathognomonic in HFpEF.5, 10-12, 15, 16 A therapy that reduces cardiac filling pressures, restores cardiac and vascular reserve, and enhances peripheral oxygen delivery and utilization in skeletal muscle would therefore be expected to greatly improve exercise capacity and symptoms of effort intolerance in patients with HFpEF, despite interindividual phenotypic heterogeneity.

Evidence for deranged NO signaling in HFpEF

While the cellular mechanisms underlying HFpEF are not completely understood, evidence points to abnormalities in the nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (NO-cGMP) pathway as playing a major role.1, 2, 17, 18 As many as 90% of patients with prevalent HFpEF display at least one comorbidity associated with endothelial dysfunction and reduced NO-cGMP availability, including advanced age, obesity, diabetes/metabolic syndrome, hypertension and kidney disease.1 This systemic NO-cGMP deficiency in HFpEF is believed to contribute to elevation in LV filling pressures, abnormalities in convective and diffusive O2 delivery from the heart to the tissues, and abnormalities in RV-PA coupling.1, 2

Evidence for impaired NO-cGMP signaling in patients with HFpEF was first identified in the peripheral systemic vasculature, evidenced by impaired endothelium-mediated vasodilation as compared to healthy age-matched controls.16 Impairments in endothelial function are correlated with greater symptoms of dyspnea and fatigue on exercise, lower peak oxygen consumption (VO2) and reduced blood flow to the periphery.16 This may partly explain the inability to deliver and utilize O2 in the tissues in many HFpEF patients.9-11 Impairment in peripheral (systemic) endothelium-dependent vasodilation is also correlated with pulmonary vascular disease in patients with HFpEF,19 which ultimately leads to development of RV dysfunction and increased risk of death.20, 21

Direct myocardial tissue studies have identified low cGMP levels, decreased cGMP-dependent protein kinase (or protein kinase G, PKG) activity and reduced nitrite concentration in HFpEF.22, 23 This is believed to play a key role in the elevation in LV filling pressures in HFpEF, possibly via decreased PKG phosphorylation of the sarcomeric spring protein titin, which makes cardiomyocytes stiffer.22, 24, 25 Renal dysfunction, which is common in HFpEF, is also associated with inflammation, reduced NO-cGMP signaling, myocardial dysfunction, and accelerated progression in arterial stiffening and endothelial dysfunction.26 Finally, recent studies have shown impairment in coronary microvascular structure and function that are related in large part to abnormalities in NO-cGMP bioavailability in HFpEF, which may limit O2 delivery and utilization in the heart as well as the periphery.27-29

Trials Targeting NO-cGMP Deficiency in HFpEF

In a single center study, the phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitor sildenafil (which increases cGMP via decreased breakdown) improved hemodynamics, RV function and gas exchange in subjects with HFpEF with significant LV hypertrophy and evidence of combined pre- and post-capillary pulmonary hypertension (PH).30 However, the larger, multicenter RELAX trial observed no effect of sildenafil on exercise capacity, quality of life (QOL), or neurohormone levels in a broader population of HFpEF patients.31 This may have been related to reductions in LV contractility.32 A subsequent trial again confirmed no benefit of PDE5 inhibitors in HFpEF with PH.33

While these data may be interpreted to speak against the NO-cGMP hypothesis, van Heerebeek et al. observed that NO-cGMP deficiency in HFpEF was not related to excess cGMP catabolism by PDE5 but rather insufficient NO production.22 The oldest and most direct method to increase NO levels is administration of organic nitrates. Acute infusion of nitroprusside significantly reduces filling pressures and PA pressure in patients with HFpEF, but also causes more hypotension and increased risk of stroke volume reduction when compared to patients with HFrEF.34 In the NEAT trial, isosorbide mononitrate did not improve submaximal exercise capacity or QOL, and tended to decrease chronic activity levels assessed by accelerometry in subjects with HFpEF.35

The Inorganic Nitrate-Nitrite Pathway to Restore NO in HFpEF

An alternative strategy to enhance NO-cGMP signalling is via the inorganic nitrate-nitrite-NO pathway. Nitrate and nitrite anions were previously considered to be inert byproducts of endogenous NO metabolism, but these species are now known to function as an important in vivo reservoir for NO generation.36-38 Nitrite is reduced to NO in a one-step reaction catalyzed by a number of proteins including hemoglobin and myoglobin. This reaction is enhanced in the setting of hypoxia and acidosis, conditions that develop during exercise. Patients with HFpEF characteristically develop pulmonary venous and arterial hypertension during exercise, even when resting hemodynamics are normal.1, 3, 5, 12 Thus, nitrite may serve as a means of providing increased NO signaling in the heart and periphery precisely at the time of greatest need, with less risk for potentially deleterious reductions in stroke volume or blood pressure at rest.8, 13, 39

Plasma nitrite levels may be increased through direct administration, or indirectly by providing inorganic nitrate, which acts as a prodrug that must be reduced to nitrite by commensal bacteria in the mouth following salivary secretion, since humans lack the ability to reduce nitrate to nitrite.36-38 Nitrite levels can increase from dietary intake, particularly green leafy vegetables and beetroot. This is one of the mechanisms hypothesized to underlie the favorable effects of the Mediterranean diet on blood pressure.37 Greater concentrations may be administered pharmacologically.

In patients without HF, acute or short-term administration of inorganic nitrite (or its precursor, inorganic nitrate) has been shown to modestly reduce blood pressure, improve endothelial function, selectively dilate conduit vessels, decrease vascular stiffness and reduce arterial wave reflections.40-45 Inorganic nitrate and nitrite improve skeletal muscle microvascular conductance during exercise46 and increase capillary O2 tension facilitating O2 diffusion into muscle cells.47 Nitrite increases mitochondrial efficiency in skeletal muscle48 and improves insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake.49 A recent study in human HFrEF demonstrated improvements in muscle power with acute inorganic nitrate administration.50 Each of these salutary effects of inorganic nitrate/nitrite would be expected to improve the peripheral limitations that constrain exercise capacity in some patients with chronic HFpEF (Figure 1).4, 9-11

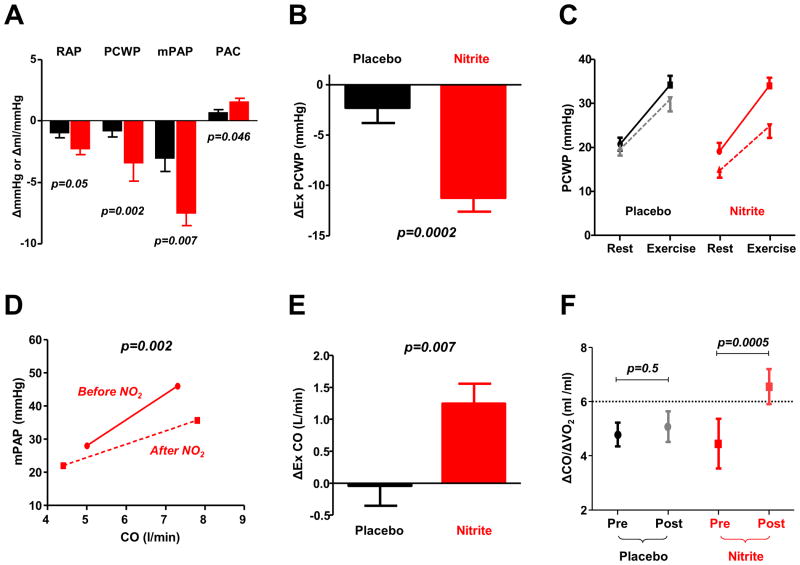

In addition to these peripheral benefits of nitrite, there is even more compelling evidence for favorable central cardiac effects. In mice with RV or LV failure secondary to pulmonary or systemic pressure overload, nitrite administration improves ventricular structure and function.51, 52 These positive results have recently been translated to humans. In a double blind randomized controlled trial, intravenous infusion of sodium nitrite was shown to modestly reduce biventricular filling pressures and PA pressures at rest, but dramatically reduce filling pressures and PA pressure during exercise in subjects with HFpEF (Figure 2).8 Compared to placebo, nitrite enabled greater improvements in forward cardiac output, stroke volume and stroke work during exercise, with marked reduction in exercise-induced elevations in PA pressure and improvement in the PA pressure-flow relationship. Similar hemodynamic benefits were noted with intravenous nitrite in an open label study conducted in HFrEF patients.53 Orally administered inorganic nitrate, which is converted to active molecule nitrite, has been shown to improve exercise duration and systemic vascular function when administered as a single dose or with repeated doses over 1-2 weeks in patients with HFpEF.54-56

Figure 2. Hemodynamic effects of nitrite in HFpEF.

[A] Acute administration of inhaled and intravenous nitrite leads to reductions in right atrial pressure (RAP), pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), and mean pulmonary artery (PA) pressure (mPAP) at rest, with improvement in PA compliance (PAC). [B, C] Reductions in PCWP during exercise are significantly greater because of greater conversion of nitrite to NO during stress. [D] Nitrite administration decreases the slope of the PA pressure-flow relationship, with lower PA pressure for any cardiac output (CO), while improving CO reserve during exercise [E, F], measured by the increase in CO, or the increase in CO relative to total body O2 consumption (ΔCO/ΔVO2). Figures adapted with permission from references 8 and 13.

Rationale for Nitrite and the Inhaled Delivery Route

Both inorganic nitrate and nitrite can be given orally, but it is not clear that the plasma levels achieved with oral administration will be sufficient to see hemodynamic benefits observed in the invasive studies, since intravenous administration leads to nitrite levels that are an order of magnitude higher than those achieved with oral formulations.8, 13, 42 To circumvent the problems associated with the need for parenteral administration, an inhaled, nebulized form of nitrite has been developed and tested in two small, single-center acute trials in subjects with HFpEF.13, 57 As compared to placebo, inhaled nitrite was shown to reduce biventricular filling pressures and decreases PA pressures, both at rest and during exercise, similar to what was observed with the intravenous formulation (Figure 2).8, 13

The nebulized method of drug delivery is a particularly novel aspect of the trial in that this route of administration has not been tested in a multicenter HF trial. Inhaled, nebulized administration leverages the enormous surface area available at the alveolar-capillary interface to allow for efficient, rapid, systemic delivery of drugs that have traditionally been available only via parenteral administration.13 Plasma nitrite concentrations achieved with single dose inhaled nitrite are similar to slightly higher than what is observed with intravenous nitrite.8, 13 Pulmonary artery compliance was improved with inhaled nitrite (Figure 3), and while pulmonary vascular resistance did not change, there was a tendency toward vasodilation in patients with the highest baseline resistance.13, 57 Inhaled nitrite was well-tolerated with no hypotension or clinically significant methemoglobinemia observed in either study.13, 57

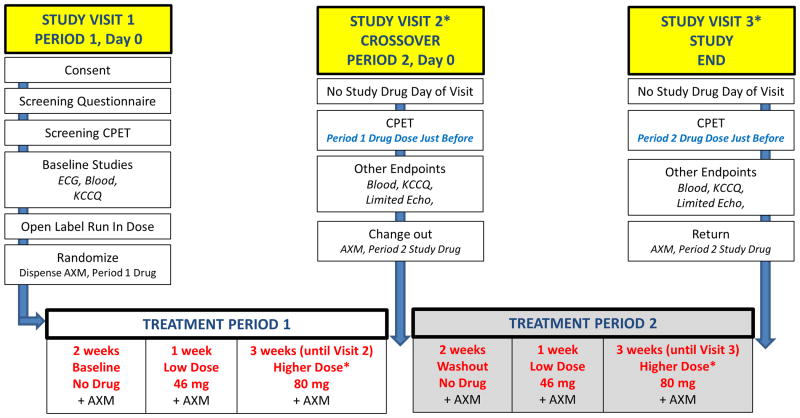

Figure 3. INDIE Study Flow Diagram.

See text for details. CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise test; ECG, electrocardiogram; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; AXM, accelerometer; echo, echocardiogram. A follow up phone call (not depicted) will be performed 2 weeks following the final visit to assess for adverse events. *Subjects not tolerating higher dose study drug will continue on low dose for final 3 weeks.

Therapeutic Advantages of Inorganic Nitrite compared to Organic Nitrates

Patients with HFpEF display marked ventricular-vascular stiffening that renders them more susceptible to hypotension and/or reduction in stroke volume with excessive vasodilation.34, 58 This has the potential to cause dizziness, orthostatic intolerance, syncope and prerenal azotemia from decreased renal perfusion pressure. This may partially explain why organic nitrate therapy caused a paradoxical decrease in activity levels in the NEAT trial,35 and why sildenafil caused worsening renal function compared to placebo in the RELAX trial.31 These adverse effects related to excessive vasodilatation should theoretically be lower with inorganic nitrite, since increases in NO production will be more pronounced during exercise, with less risk of hemodynamic embarrassment at rest.8, 13

There are other potential key advantages of inorganic nitrite. Unlike the organic nitrates, there is no tolerance with inorganic nitrite.59 Neurohormonal and sympathetic activation associated with organic nitrates can lead to plasma volume expansion and vasoconstrictor responses, counteracting their beneficial effects on vascular tone, a phenomenon termed ‘pseudo-tolerance’. This has not been described with nitrite. Finally, bioactivation of organic nitrates increases oxidative stress and worsens endothelial dysfunction, potentially exacerbating processes that are considered to play fundamental roles in the pathophysiology of HFpEF.1, 2, 34, 60, 61 In contrast, inorganic nitrate and nitrite have been shown to improve endothelium-dependent vasodilation in humans.43, 45

Design of the INDIE trial

This body of evidence forms the basis for the INDIE-HFpEF trial (Inorganic Nitrite Delivery to Improve Exercise Capacity in HFpEF), which is being conducted within the NHLBI-sponsored Heart Failure Clinical Research Network (HFCRN). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the steering committee of the HFCRN as well as the independent protocol review committee and data safety and monitoring board of the network. The INDIE trial is a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study to evaluate the effect of inhaled inorganic nitrite on aerobic capacity (peak oxygen consumption, VO2) after four weeks of treatment. Approximately 100 participants are being enrolled in this 2*2 crossover study. In addition to exercise capacity, the INDIE trial is examining the effects of nitrite on chronic daily activity levels assessed by accelerometry, HF severity by NYHA class and QOL, LV filling pressures assessed by echocardiography and natriuretic peptide levels, other exercise indices, and safety and tolerability.

The primary hypothesis of the INDIE-HFpEF trial is that inorganic nitrite, compared to placebo, will improve peak VO2 in subjects with chronic HFpEF. The significance of this study is that it is testing the hypothesis that nitrite therapy improves aerobic capacity, a patient centric and clinically-relevant endpoint, in patients with HFpEF. If the experimental evidence obtained supports our hypothesis, this would provide the rationale to pursue a pivotal, longer-duration phase 3 trial of inorganic nitrate/nitrite therapy to improve clinical outcomes in HFpEF.

Entry criteria

Strict inclusion criteria for HFpEF are required for eligibility, including LV ejection fraction≥50%, NYHA class II or greater symptoms, and a diagnosis of HFpEF defined by (a) previous HF hospitalization (b) invasive hemodynamics, (c) echocardiographic evidence of diastolic dysfunction, or (d) NT-proBNP based criteria (Table 1). Subjects are required to display objective evidence of impaired exercise capacity. Given the common problem of multi-morbidity in HFpEF and the myriad of competing causes for exertional intolerance, participants are required to identify that their primary limitation to exercise is due to cardiac limitations rather than pain, unsteadiness, or motivation in a questionnaire. Patients treated with NO-cGMP enhancing therapies such as organic nitrates or phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, recent HF hospitalization, hypotension, history of low EF, severe anemia, kidney or liver disease, alternative causes of HF (e.g. pericardial disease, cardiomyopathies, valvular heart disease) or alternative causes dyspnea (e.g. severe pulmonary disease) are excluded (Table 1).

Table 1. Entry Criteria for the INDIE-HFpEF Trial.

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

| 1. Age ≥ 40 years |

| 2. Symptoms of dyspnea (NYHA class II-IV) without evidence of a non-cardiac or ischemic explanation for dyspnea |

| 3. EF ≥ 50% as determined on imaging study within 12 months of enrollment with no change in clinical status suggesting potential for deterioration in systolic function |

4. One of the following:

|

5. Heart failure is primary factor limiting activity as indicated by answering #2 to the following question: My ability to be active is most limited by:

|

| 6. Peak VO2 ≤75% predicted with peak respiratory exchange ratio≥1.0 on CPET |

| 7. No chronic nitrate therapy or not using intermittent sublingual nitroglycerin (requirement for >1 SL nitroglycerin per week) within last 6 months |

| 8. No daily use of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors or soluble guanylyl cyclase activators and willing to withhold prn use of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors for duration of study |

| 9. Ambulatory (not wheelchair / scooter dependent) |

| 10. Body size allows wearing of the accelerometer belt as confirmed by ability to comfortably fasten the test belt provided for the screening process (belt designed to fit persons with BMI 20-40 kg/m2 but belt may fit some persons outside this range) |

| 11. Willingness to wear the accelerometer belt for the duration of the trial |

| 12. Willingness to provide informed consent |

| Key exclusion criteria |

| 1. Recent (<1 month) hospitalization for heart failure |

| 2. Ongoing requirement for PDE5 inhibitor, organic nitrate or soluble guanylyl cyclase activators |

| 3. Hemoglobin <8.0 g/dl within 30 days prior to randomization |

| 4. GFR <20 ml/min/1.73 m2 within 30 days prior to randomization |

| 5. Systolic blood pressure <115 mmHg seated or <90 mmHg standing just prior to test dose |

| 6. Resting heart rate>110 just prior to test dose |

| 7. Documentation of previous EF<45% |

| 8. Acute coronary syndrome, PCI or CABG within 3 months |

| 9. Hypertrophic or Infiltrative cardiomyopathy (amyloid) |

NYHA-New York Heart Association, EF-Ejection Fraction, PCWP-Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure, LVEDP-Left Ventricular End Diastolic Pressure, VO2-Oxygen Consumption, CPET-Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing, PDE5-Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor, GFR-glomerular filtration rate, PCI-Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, CABG-Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting,

Study Design

Potentially eligible patients undergo a screening visit with a baseline cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) to verify eligibility with both a peak VO2≤75% predicted with adequate effort, defined by respiratory exchange ratio≥1.0 (Visit 1, Figure 3).62 Following screening CPET, eligible subjects receive an open label, single-dose run-in of inhaled, nebulized sodium nitrite (80 mg) to assess tolerability. Symptoms and orthostatic vital signs are monitored every 15 minutes for one hour. The development of hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90mmHg seated or standing), light-headedness, or other inability to tolerate the run-in dose is categorized as a run-in failure, and those patients are not randomized. Participants successfully completing the run-in are then randomized to placebo first (with subsequent crossover to inorganic nitrite) or inorganic nitrite first (with subsequent crossover to placebo). A permuted block randomization method stratified by site is being used.

The first two weeks are drug free periods during which subjects wear accelerometers in order to establish baseline activity levels in the absence of intervention (Figure 3). After this period, subjects begin study drug treatment with either low dose inhaled, nebulized nitrite (46 mg) or low dose inhaled, nebulized placebo, administered 3 times daily, at a minimum of 4 hours apart, with the first dose starting at the beginning of the active part of the day (for example, 8:00, 12:00, and 16:00). Study drug is administered using the Philips I-neb AAD nebulizer over 10-15 minutes for each dose.63 The I-neb is a small, battery-powered, lightweight, portable and virtually silent drug delivery device designed to deliver a precise, reproducible dose of drug (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The nebulizer device used for nitrite delivery (Philips I-neb AAD).

After 1 week at 46 mg study drug, subjects increase to full dose study drug (80mg inhaled nitrite or placebo) using the same dosing frequency, which is continued for 3 weeks. If significant headaches occur, participants are encouraged to treat them with acetaminophen. If participants cannot tolerate the 46 mg dose, they discontinue study drug but continue with all study procedures and visits. If participants cannot tolerate the 80 mg dose, they return to the previously tolerated 46 mg dose and continue all study procedures and visits.

At the conclusion of Study Phase 1, participants return for Study Visit 2 (Figure 3). Following study procedures including physical exam, blood work and echocardiography, subjects receive a dose of Phase 1 study drug followed immediately by maximal effort CPET for assessment of the primary endpoint. This ensures that exercise is performed at the time of maximal plasma nitrite concentrations. Accelerometers are returned and changed, Phase 1 study drug is returned and Phase 2 study drug is dispensed.

Following Study Visit 2, participants wear the accelerometer devices daily but take no study drug for 14 days (washout period, Figure 3). Because of the short duration of administration (4 weeks) and the half-life of nitrite (35-40 min), this should ensure that there is no period or carryover effect. On day 15 following Study Visit 2, subjects begin treatment with Phase 2 study drug at 46 mg 3 times daily for one week, followed by an increase to 80 mg 3 times daily for 3 weeks, following the same protocol as Study Phase 1.

At the conclusion of Study Phase 2 subjects return for Study Visit 3, which includes endpoint assessments as outlined for Study Visit 2 (Figure 3). Accelerometers and unused study drug are returned and participants are asked to indicate the study phase during which they felt better. A final phone visit is conducted 2 weeks after Study Visit 3 to assess adverse effects and clinical stability.

Methods to ensure adequate study drug delivery

At the first study visit, participants receive extensive teaching using the nebulizer device, using of a practice system that provides real-time feedback. Participants are required to demonstrate proficiency by the conclusion of the visit. Online videos and enduring materials are provided for additional instruction at home. The device itself is programmed to provide study drug only during an adequate mouth inhalation, ensuring complete delivery. A readout is displayed on the device at the conclusion of a treatment indicating successful delivery, and no study drug liquid remains in the cartridge. There are frequent phone calls built into the protocol with study staff to verify that there are not problems with drug delivery using the device, with troubleshooting contingency plans.

Co-administration of inorganic nitrite with an organic nitrate, such as nitroglycerin, is prohibited by entry criteria because of the potential concern for hypotension. If a participant should require emergent administration of nitroglycerin, for example with an acute coronary syndrome, the risks of combined NO activation will need to be weighed by caring physicians and investigators on a case-by-case basis.

Choice of the primary endpoint

The primary endpoint is peak VO2 after 4 weeks treatment with inhaled, nebulized nitrite as compared to peak VO2 after 4 weeks treatment with inhaled, nebulized placebo. The choice of peak VO2 as an endpoint is particularly relevant to the HFpEF population because it is an objective and reproducible measure of exercise capacity. The rationale for targeting exercise tolerance is that this is the cardinal symptomatic manifestation of HFpEF and is a patient-centric and accepted endpoint in HF in general.

The mechanism of action of nitrite is well-suited to an exercise endpoint, because NO delivery is facilitated by the conditions that develop in vivo during exercise and hemodynamic improvements have been demonstrated to be most dramatic at this time in previous studies.8, 13 The use of CPET for both screening and endpoint assessment ensures that patients are capable of reaching adequate effort, with objective limitation in aerobic capacity caused by central and peripheral limitations that prior studies indicate should be improved with nitrite treatment.

Secondary Outcomes and Analyses

Additional CPET measures including exercise duration, ventilatory efficiency as measured by the slope of minute ventilation relative to CO2 elimination, and VO2 at the ventilatory threshold are being determined as key secondary endpoints. Because nitrite may improve the efficiency of O2 utilization at the level of the mitochondria,48 it is conceivable that exercise duration could be improved more than peak VO2. Chronic daily activity will be assessed using hip worn accelerometers. This will provide highly granular data into the effect of nitrite on daily activity levels assessed by average daily accelerometry units.35

Quality of life will be assessed by Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) and HF severity will be determined by NYHA class.64 Effects of nitrite on LV filling pressures will be assessed at trough nitrite concentrations (i.e. prior to study drug dose) using echocardiography (E/e' ratio, left atrial volume index and estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure) and plasma NT-proBNP levels. Patient preference for study phase (nitrite or placebo) will be determined along with tolerability and adverse events. Renal function will be assessed by cystatin-C and nitrite effect by plasma cGMP levels will assess the biological effect of nitrite.

Prespecified subgroup analyses will be performed to evaluate the effects of inhaled nitrite according to age, sex, presence or absence of key comorbidities (atrial fibrillation, diabetes, kidney disease), symptoms (chest pain vs no chest pain), presence or absence of elevated NT-proBNP (>400pg/ml vs. ≤400 pg/ml), baseline activity levels assessed by accelerometry prior to study drug, and the presence of PH by echocardiography (>60 mmHg vs <60 mmHg). Safety and tolerability will be assessed along with plasma methemoglobin levels. The primary adverse effects expected related to inhaled nitrite include cough, throat irritation, headache, and dizziness. Each of these will be captured as relevant safety endpoints.

Statistical considerations

The primary analysis will be conducted on an intention-to-treat basis, including all patients that were randomized regardless of adherence to therapy. The primary endpoint analysis will involve a mixed model with fixed effect terms for the sequence, period and treatment. When available, the baseline value of the variable will be included in the model. A random effect term will be included to account for the correlated measurements within each participant. Given the short half-life of the drug (40 minutes), the two-week washout period, and the assumed lack of remodeling effects with this duration of treatment, we anticipate no significant carry-over or residual effect from Phase 1 to Phase 2. Interim data analysis for efficacy and futility will not be conducted due to relatively small size, short duration, and crossover structure of this clinical trial. Safety data, summarized at the treatment level, will be assessed approximately every 6 months by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)-appointed DSMB.

The within-patient standard deviation for peak VO2 in HFpEF is roughly 2 ml/min/kg.31 A 1.2 ml/min/kg increase in peak VO2 is considered to be clinically meaningful for a particular patient.31 Assuming a 2 ml/min/kg standard deviation, a total of 90 participants would provide 80% power to detect a difference of 0.6 ml/min/kg in peak VO2. These calculations are based on a 2*2 factorial design and assume a 2-sided 0.05 (or 1-sided 0.025) type I error rate. The total sample size of 100 participants allows for approximately 10% incomplete data due to missed tests, death, and withdrawal of consent. In the NEAT study, the within-patient standard deviation for the KCCQ overall summary score was approximately 14 points.35 A clinically-significant difference is considered to be ≥5 points and a moderately large clinical difference is considered to be ≥10 points.65 Assuming a 14 point standard deviation, a total of 70 participants will provide >80% power to detect a clinically-significant difference of 5 points in the KCCQ overall summary score.

Discussion

Considering the central cardiac and peripheral abnormalities that constrain exercise capacity in HFpEF, the abundant evidence that these abnormalities are related in large part to deficient NO-cGMP signaling, and the ability in short-term single-center studies to improve pathophysiological markers of disease severity in HFpEF, we are testing the hypothesis that treatment with inhaled, nebulized nitrite will improve exercise capacity in patients with HFpEF. The INDIE-HFpEF study represents a critical next step to determine whether the inorganic nitrate-nitrite-NO pathway will serve as a viable therapeutic option for people suffering with HFpEF. Its novel drug delivery via an inhaler provides a unique and patient-controlled system of rapid absorption that may be applicable to other parenterally active medicines used in HF patients. Targeted NO delivery at the time of greatest need may allow for optimal hemodynamic improvement during stress, with less risk for hemodynamic compromise at rest. Given the lack of established drug therapies in HFpEF, completing the INDIE trial will address an important unmet public health need and help inform whether larger scale pivotal trials testing inorganic nitrite intervention are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (co-coordinating center: U10 HL084904 and regional clinical centers: U10 HL110312, U109 HL110337, U10 HL110342, U10 HL110262, U10 HL110297, U10 HL110302, U10 HL110309, U10 HL110336, and U10 HL110338) and by a restricted research grant from Mast Therapeutics.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Hernandez reports research support from Merck, Novartis, Luitpold, and consulting honoraria from Amgen, Bayer, and Novartis. Dr. Braunwald reports grant support from Duke University for his role as Chair of the NHLBI Heart Failure Network. Dr. Borlaug has received research support in the form of a restricted research grant from Mast Therapeutics. All other authors report no disclosures.

References

- 1.Shah SJ, Kitzman DW, Borlaug BA, van Heerebeek L, Zile MR, Kass DA, Paulus WJ. Phenotype-specific treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A multiorgan roadmap. Circulation. 2016;134:73–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paulus WJ, Tschope C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borlaug BA. The pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:507–515. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Upadhya B, Haykowsky MJ, Eggebeen J, Kitzman DW. Exercise intolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: More than a heart problem. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2015;12:294–304. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borlaug BA, Kane GC, Melenovsky V, Olson TP. Abnormal right ventricular-pulmonary artery coupling with exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3293–3302. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos M, Opotowsky AR, Shah AM, Tracy J, Waxman AB, Systrom DM. Central cardiac limit to aerobic capacity in patients with exertional pulmonary venous hypertension: Implications for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:278–285. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abudiab MM, Redfield MM, Melenovsky V, Olson TP, Kass DA, Johnson BD, Borlaug BA. Cardiac output response to exercise in relation to metabolic demand in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:776–785. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borlaug BA, Koepp KE, Melenovsky V. Sodium nitrite improves exercise hemodynamics and ventricular performance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1672–1682. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhella PS, Prasad A, Heinicke K, Hastings JL, Arbab-Zadeh A, Adams-Huet B, Pacini EL, Shibata S, Palmer MD, Newcomer BR, Levine BD. Abnormal haemodynamic response to exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1296–1304. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhakal BP, Malhotra R, Murphy RM, Pappagianopoulos PP, Baggish AL, Weiner RB, Houstis NE, Eisman AS, Hough SS, Lewis GD. Mechanisms of exercise intolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: The role of abnormal peripheral oxygen extraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:286–294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, John JM, Stewart KP, Morgan TM, Kitzman DW. Determinants of exercise intolerance in elderly heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borlaug BA, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, Lam CS, Redfield MM. Exercise hemodynamics enhance diagnosis of early heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:588–595. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.930701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borlaug BA, Melenovsky V, Koepp KE. Inhaled sodium nitrite improves rest and exercise hemodynamics in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Res. 2016;119:880–886. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adamson PB, Abraham WT, Bourge RC, Costanzo MR, Hasan A, Yadav C, Henderson J, Cowart P, Stevenson LW. Wireless pulmonary artery pressure monitoring guides management to reduce decompensation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:935–944. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.001229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maeder MT, Thompson BR, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Kaye DM. Hemodynamic basis of exercise limitation in patients with heart failure and normal ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:855–863. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Lam CS, Flood KS, Lerman A, Johnson BD, Redfield MM. Global cardiovascular reserve dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greene SJ, Gheorghiade M, Borlaug BA, Pieske B, Vaduganathan M, Burnett JC, Jr, Roessig L, Stasch JP, Solomon SD, Paulus WJ, Butler J. The cgmp signaling pathway as a therapeutic target in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000536. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddy YN, Borlaug BA. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2016;41:145–188. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrero M, Blanco I, Batlle M, Santiago E, Cardona M, Vidal B, Castel MA, Sitges M, Barbera JA, Perez-Villa F. Pulmonary hypertension is related to peripheral endothelial dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:791–798. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melenovsky V, Hwang SJ, Lin G, Redfield MM, Borlaug BA. Right heart dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3452–3462. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohammed SF, Hussain I, Abou Ezzeddine OF, Takahama H, Kwon SH, Forfia P, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Right ventricular function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A community-based study. Circulation. 2014;130:2310–2320. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Heerebeek L, Hamdani N, Falcao-Pires I, Leite-Moreira AF, Begieneman MP, Bronzwaer JG, van der Velden J, Stienen GJ, Laarman GJ, Somsen A, Verheugt FW, Niessen HW, Paulus WJ. Low myocardial protein kinase g activity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2012;126:830–839. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.076075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franssen C, Chen S, Unger A, Korkmaz HI, De Keulenaer GW, Tschope C, Leite-Moreira AF, Musters R, Niessen HW, Linke WA, Paulus WJ, Hamdani N. Myocardial microvascular inflammatory endothelial activation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4:312–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bishu K, Hamdani N, Mohammed SF, Kruger M, Ohtani T, Ogut O, Brozovich FV, Burnett JC, Jr, Linke WA, Redfield MM. Sildenafil and b-type natriuretic peptide acutely phosphorylate titin and improve diastolic distensibility in vivo. Circulation. 2011;124:2882–2891. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.048520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zile MR, Baicu CF, Ikonomidis JS, Stroud RE, Nietert PJ, Bradshaw AD, Slater R, Palmer BM, Van Buren P, Meyer M, Redfield MM, Bull DA, Granzier HL, LeWinter MM. Myocardial stiffness in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: Contributions of collagen and titin. Circulation. 2015;131:1247–1259. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Unger ED, Dubin RF, Deo R, Daruwalla V, Friedman JL, Medina C, Beussink L, Freed BH, Shah SJ. Association of chronic kidney disease with abnormal cardiac mechanics and adverse outcomes in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:103–112. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohammed SF, Hussain S, Mirzoyev SA, Edwards WD, Maleszewski JJ, Redfield MM. Coronary microvascular rarefaction and myocardial fibrosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2015;131:550–559. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Empel VP, Mariani J, Borlaug BA, Kaye DM. Impaired myocardial oxygen availability contributes to abnormal exercise hemodynamics in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001293. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srivaratharajah K, Coutinho T, deKemp R, Liu P, Haddad H, Stadnick E, Davies RA, Chih S, Dwivedi G, Guo A, Wells GA, Bernick J, Beanlands R, Mielniczuk LM. Reduced myocardial flow in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002562. pii: e002562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guazzi M, Vicenzi M, Arena R, Guazzi MD. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A target of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition in a 1-year study. Circulation. 2011;124:164–174. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.983866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Redfield MM, Chen HH, Borlaug BA, Semigran MJ, Lee KL, Lewis G, Lewinter MM, Rouleau JL, Bull DA, Mann DL, Deswal A, Stevenson LW, Givertz MM, Ofili EO, O'Connor CM, Felker GM, Goldsmith SR, Bart BA, McNulty SE, Ibarra JC, Lin G, Oh JK, Patel MR, Kim RJ, Tracy RP, Velazquez EJ, Anstrom KJ, Hernandez AF, Mascette AM, Braunwald E. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1268–1277. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borlaug BA, Lewis GD, McNulty SE, Semigran MJ, LeWinter M, Chen H, Lin G, Deswal A, Margulies KB, Redfield MM. Effects of sildenafil on ventricular and vascular function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:533–541. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoendermis ES, Liu LC, Hummel YM, van der Meer P, de Boer RA, Berger RM, van Veldhuisen DJ, Voors AA. Effects of sildenafil on invasive haemodynamics and exercise capacity in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction and pulmonary hypertension: A randomized controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2565–2573. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartzenberg S, Redfield MM, From AM, Sorajja P, Nishimura RA, Borlaug BA. Effects of vasodilation in heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction implications of distinct pathophysiologies on response to therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Redfield MM, Anstrom KJ, Levine JA, Koepp GA, Borlaug BA, Chen HH, LeWinter MM, Joseph SM, Shah SJ, Semigran MJ, Felker GM, Cole RT, Reeves GR, Tedford RJ, Tang WH, McNulty SE, Velazquez EJ, Shah MR, Braunwald E. Isosorbide mononitrate in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2314–2324. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanderpool R, Gladwin MT. Harnessing the nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway for therapy of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2015;131:334–336. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Omar SA, Webb AJ, Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E. Therapeutic effects of inorganic nitrate and nitrite in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. J Intern Med. 2016;279:315–36. doi: 10.1111/joim.12441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:156–167. doi: 10.1038/nrd2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paulus WJ, van Heerebeek L. Ancient gunpowder and novel insights team up against heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1683–1686. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cosby K, Partovi KS, Crawford JH, Patel RP, Reiter CD, Martyr S, Yang BK, Waclawiw MA, Zalos G, Xu X, Huang KT, Shields H, Kim-Shapiro DB, Schechter AN, Cannon RO, 3rd, Gladwin MT. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1498–1505. doi: 10.1038/nm954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kapil V, Khambata RS, Robertson A, Caulfield MJ, Ahluwalia A. Dietary nitrate provides sustained blood pressure lowering in hypertensive patients: A randomized, phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Hypertension. 2015;65:320–327. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kapil V, Milsom AB, Okorie M, Maleki-Toyserkani S, Akram F, Rehman F, Arghandawi S, Pearl V, Benjamin N, Loukogeorgakis S, Macallister R, Hobbs AJ, Webb AJ, Ahluwalia A. Inorganic nitrate supplementation lowers blood pressure in humans: Role for nitrite-derived no. Hypertension. 2010;56:274–281. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.153536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rammos C, Hendgen-Cotta UB, Sobierajski J, Bernard A, Kelm M, Rassaf T. Dietary nitrate reverses vascular dysfunction in older adults with moderately increased cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1584–1585. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Omar SA, Fok H, Tilgner KD, Nair A, Hunt J, Jiang B, Taylor P, Chowienczyk P, Webb AJ. Paradoxical normoxia-dependent selective actions of inorganic nitrite in human muscular conduit arteries and related selective actions on central blood pressures. Circulation. 2015;131:381–389. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009554. discussion 389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeVan AE, Johnson LC, Brooks FA, Evans TD, Justice JN, Cruickshank-Quinn C, Reisdorph N, Bryan NS, McQueen MB, Santos-Parker JR, Chonchol MB, Bassett CJ, Sindler AL, Giordano T, Seals DR. Effects of sodium nitrite supplementation on vascular function and related small metabolite signatures in middle-aged and older adults. J Appl Physiol. 2016;120:416–425. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00879.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glean AA, Ferguson SK, Holdsworth CT, Colburn TD, Wright JL, Fees AJ, Hageman KS, Poole DC, Musch TI. Effects of nitrite infusion on skeletal muscle vascular control during exercise in rats with chronic heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H1354–1360. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00421.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Colburn TD, Ferguson SK, Holdsworth CT, Craig JC, Musch TI, Poole DC. Effect of sodium nitrite on local control of contracting skeletal muscle microvascular oxygen pressure in healthy rats. J Appl Physiol. 2017;122:153–160. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00367.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Larsen FJ, Schiffer TA, Borniquel S, Sahlin K, Ekblom B, Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E. Dietary inorganic nitrate improves mitochondrial efficiency in humans. Cell Metab. 2011;13:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lai YC, Tabima DM, Dube JJ, Hughan KS, Vanderpool RR, Goncharov DA, St Croix CM, Garcia-Ocana A, Goncharova EA, Tofovic SP, Mora AL, Gladwin MT. Sirt3-amp-activated protein kinase activation by nitrite and metformin improves hyperglycemia and normalizes pulmonary hypertension associated with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2016;133:717–731. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coggan AR, Leibowitz JL, Spearie CA, Kadkhodayan A, Thomas DP, Ramamurthy S, Mahmood K, Park S, Waller S, Farmer M, Peterson LR. Acute dietary nitrate intake improves muscle contractile function in patients with heart failure: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:914–920. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhushan S, Kondo K, Polhemus DJ, Otsuka H, Nicholson CK, Tao YX, Huang H, Georgiopoulou VV, Murohara T, Calvert JW, Butler J, Lefer DJ. Nitrite therapy improves left ventricular function during heart failure via restoration of nitric oxide-mediated cytoprotective signaling. Circ Res. 2014;114:1281–1291. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.301475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zuckerbraun BS, Shiva S, Ifedigbo E, Mathier MA, Mollen KP, Rao J, Bauer PM, Choi JJ, Curtis E, Choi AM, Gladwin MT. Nitrite potently inhibits hypoxic and inflammatory pulmonary arterial hypertension and smooth muscle proliferation via xanthine oxidoreductase-dependent nitric oxide generation. Circulation. 2010;121:98–109. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.891077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ormerod JO, Arif S, Mukadam M, Evans JD, Beadle R, Fernandez BO, Bonser RS, Feelisch M, Madhani M, Frenneaux MP. Short-term intravenous sodium nitrite infusion improves cardiac and pulmonary hemodynamics in heart failure patients. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:565–571. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zamani P, Rawat D, Shiva-Kumar P, Geraci S, Bhuva R, Konda P, Doulias PT, Ischiropoulos H, Townsend RR, Margulies KB, Cappola TP, Poole DC, Chirinos JA. Effect of inorganic nitrate on exercise capacity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2015;131:371–380. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012957. discussion 380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eggebeen J, Kim-Shapiro DB, Haykowsky M, Morgan TM, Basu S, Brubaker P, Rejeski J, Kitzman DW. One week of daily dosing with beetroot juice improves submaximal endurance and blood pressure in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Failure. 2016;4:428–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zamani P, Tan VX, Soto-Calderon H, Beraun M, Brandimarto J, Trieu L, Varakantam S, Doulias PT, Townsend RR, Chittams J, Margulies KB, Cappola TP, Poole DC, Ischiropoulos H, Chirinos JA. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of inorganic nitrate in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Res. 2017;120:1151–1161. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simon MA, Vanderpool RR, Nouraie M, Bachman TN, White PM, Sugahara M, Gorcsan J, 3rd, Parsley EL, Gladwin MT. Acute hemodynamic effects of inhaled sodium nitrite in pulmonary hypertension associated with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JCI insight. 2016;1:e89620. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Borlaug BA, Kass DA. Ventricular-vascular interaction in heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2008;4:23–36. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dejam A, Hunter CJ, Tremonti C, Pluta RM, Hon YY, Grimes G, Partovi K, Pelletier MM, Oldfield EH, Cannon RO, 3rd, Schechter AN, Gladwin MT. Nitrite infusion in humans and nonhuman primates: Endocrine effects, pharmacokinetics, and tolerance formation. Circulation. 2007;116:1821–1831. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.712133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oelze M, Knorr M, Kroller-Schon S, Kossmann S, Gottschlich A, Rummler R, Schuff A, Daub S, Doppler C, Kleinert H, Gori T, Daiber A, Munzel T. Chronic therapy with isosorbide-5-mononitrate causes endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and a marked increase in vascular endothelin-1 expression. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3206–3216. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thomas GR, DiFabio JM, Gori T, Parker JD. Once daily therapy with isosorbide-5-mononitrate causes endothelial dysfunction in humans: Evidence of a free-radical-mediated mechanism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1289–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fletcher GF, Balady G, Froelicher VF, Hartley LH, Haskell WL, Pollock ML. Exercise standards. A statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association. Writing group. Circulation. 1995;91:580–615. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.2.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rix PJ, Vick A, Attkins NJ, Barker GE, Bott AW, Alcorn H, Jr, Gladwin MT, Shiva S, Bradley S, Hussaini A, Hoye WL, Parsley EL, Masamune H. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and tolerability of nebulized sodium nitrite (air001) following repeat-dose inhalation in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2015;54:261–272. doi: 10.1007/s40262-014-0201-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Joseph SM, Novak E, Arnold SV, Jones PG, Khattak H, Platts AE, Davila-Roman VG, Mann DL, Spertus JA. Comparable performance of the kansas city cardiomyopathy questionnaire in patients with heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:1139–1146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Flynn KE, Pina IL, Whellan DJ, Lin L, Blumenthal JA, Ellis SJ, Fine LJ, Howlett JG, Keteyian SJ, Kitzman DW, Kraus WE, Miller NH, Schulman KA, Spertus JA, O'Connor CM, Weinfurt KP. Effects of exercise training on health status in patients with chronic heart failure: Hf-action randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1451–1459. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]