Abstract

Background

To date, no study has compared the mortality of elderly patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD) treated with home hemodialysis (HD) versus kidney transplantation (KTx).

Design, Setting, Participants

Using data from elderly patients (≥65 years) who started home HD and who received KTx in the US between 2007-2011, we created a 1:1 propensity score (PS)-matched cohort of 960 elderly patients and examined the association between treatment modality and all-cause mortality via Cox proportional hazard and competing risk regression survival models using modality failure as a competing event.

Measurements

modality of renal replacement therapy.

Results

The mean±SD age of the PS-matched home HD and KTx elderly patients at baseline were 71±6 years and 71±5 years, 69% were male (both groups), 81% and 79% of patients were white and 11% and 12% were African American, respectively. Median follow-up time was 205 days (IQR: 78-364 days) for home HD patients and 795 days (IQR: 366-1,221 days) for KTx recipients. There were 97 deaths (20%, mortality rate 253 [207-309]/1000 patient-years) in the home HD group, and 48 deaths (10%, 45 [34-60]/1000 patient-years) in the KTx group. Compared to KTx recipients, elderly patients on home HD had almost 5-times higher mortality risk (Hazard Ratio(HR): 4.74, 95% confidence interval(CI): 3.25-6.91). Similar results were seen in competing risk regression analyses (SHR: 4.71, 95%CI: 3.27-6.79). Results were consistent across different types of kidney donors and subgroups divided by various recipient characteristics.

Conclusion

KTx is associated with greater survival than home HD in elderly patients with ESRD. Further studies are needed to assess whether KTx is also associated with other benefits such as better quality of life or lower hospitalization rates.

Keywords: home hemodialysis, kidney transplantation, mortality, elderly, survival

Introduction

The proportion of elderly people (≥65 years) with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) has increased continuously over time; in 1990, 2000 and 2010, 39%, 44% and 44% of all prevalent dialysis patients, and 4%, 10% and 20% of all kidney transplant (KTx) recipients were older than 65 years, respectively.1 KTx is generally regarded as the treatment of choice in ESRD irrespective of age,2-4 given evidence of greater survival5 and better quality of life6 as compared to maintenance dialysis treatment. Previous data suggest that the projected increases in the life spans of KTx patients compared to conventional dialysis were 2.8 and 1.1 years for patients aged 65-69 and 70-74 years, respectively.5 However, in 2010, the median KTx waiting time was almost 4 years in the entire nation and even longer in some states.7 These long waiting periods may sometimes be even longer in elderly patient and may have a detrimental impact on their opportunities to receive a KTx. In addition, the life expectancy of elderly patients with ESRD may be shorter than wait times for transplant and if the home hemodialysis provides similar or better survival than KTx then transplant programs may not need to bother with working them up and listing them. This also spares precious organs for younger patients with ESRD.

Previous studies have shown that home hemodialysis (home HD) provides better survival than in-center HD in ESRD patients.8-10 Two Canadian studies have also compared the survival of nocturnal home HD patients with KTx recipients,11-13 and in the most recent study, which compared 173 of these Canadian nocturnal home HD patients to 1,517 Canadian KTx recipients from the same institution, patients with a KTx had a lower risk of treatment failure and death compared with home HD patients.13 Most of these above mentioned KTx and home HD studies included ESRD patients with a mean age between 50-60 years, and studies regarding survival of elderly ESRD patients using home HD compared to other renal replacement therapies are lacking. Fast-growing dialysis therapies such as home HD may offer the same or even better survival advantages in elderly patient compared to deceased donor transplantation, the most common KTx in the elderly. Deceased donor KTx is unfortunately also associated with the burden of a major surgery, potential post-operative complications and life-long immunosuppressive therapy.14 Home HD may thus be a better alternative to deceased donor KTx in elderly patients.

We therefore hypothesized that in the elderly, the above-mentioned small life span advantage from KTx can disappear or even reverse when compared to home HD. To address this study question, we examined the survival of incident elderly home HD and KTx patients in a large, nationally representative contemporary cohort of patients from the United States.

Methods

Data Source and Cohort Definition

The study cohort was comprised of incident home HD patients who receieved treatment from one of the largest dialysis providers in the United States, and United States incident KTx recipients who were transplanted between January 1st 2007 and December 31st 2011. Pertinent data for the two groups were obtained from electronic medical records from the large dialysis provider and from the United States Renal Data System, respectively. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Committees of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA, University of California Irvine Medical Center, University of Washington, and University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

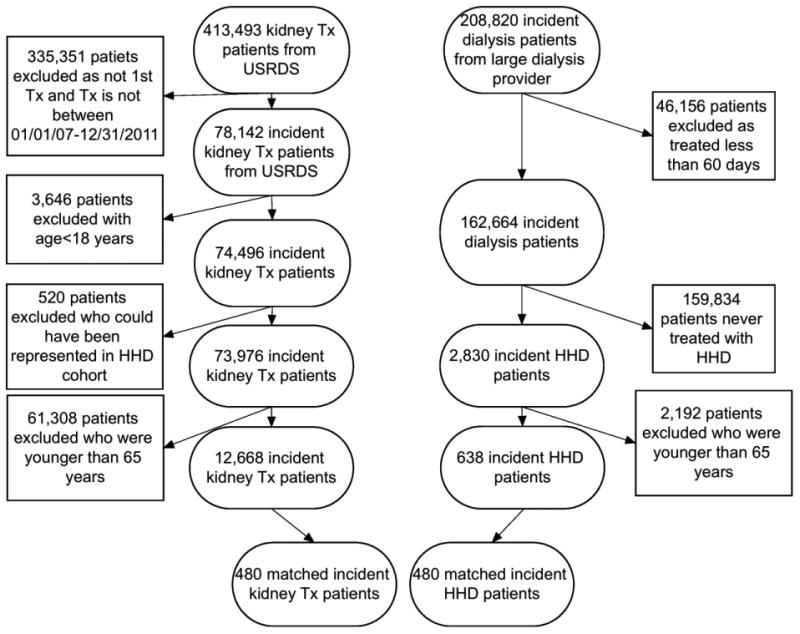

Home Hemodialysis cohort

The original source population was a cohort of 208,820 incident (newly initiated) dialysis patients. Patients were included in the cohort if they were ≥65 years old at the time of initiation of dialysis. Patients were excluded if they did not receive dialysis treatment for at least 60 days or did not have any treatment with home HD over their duration of follow up. The detailed description of dialysis modality assignment is discussed elsewhere.15 Our final elderly home HD cohort included 638 patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow chart of patients' selection.

Abbreviations: HHD: Home Hemodialysis; Tx: Kidney Transplant; USRDS: United States Renal Data System

Kidney transplant cohort

The United States Renal Data System includes all patients who received a KTx between 1963 and 2012. Patients ≥65 years old at time of transplant and who received their first kidney between January 1st 2007 and December 31st 2011 were included in our cohort. Patients were excluded if they were potentially also represented (based on age, race/ethnicity, date of transplant and gender) in the home HD cohort yielding a cohort with 12,668 KTx patients (Figure 1).

For the main analyses we created a 1:1 propensity score (PS) matched cohort consisting of 480 home HD and 480 KTx elderly patients (Figure 1).

Exposure, Covariates, Outcome

Data on age, gender, race/ethnicity, ESRD etiology and vintage, access type, primary insurance, body mass index, serum albumin, blood hemoglobin and coexisting conditions was obtained from the two data sources and refined. The following nine coexisting conditions were considered: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, alcohol abuse, atherosclerotic heart disease, other cardiac disease (pericarditis and cardiac arrhythmia), congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and malignancy. Exposure was defined as home HD versus KTx, and the outcome was all-cause mortality. Expanded criteria donors (ECD) were defined as: donors are normally aged 60 years or older, or over 50 years with at least two of the following conditions: history of hypertension, serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dl or cause of death from cerebrovascular accident. The Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) combines a variety of donor factors into a single number that summarizes the risk of graft failure after kidney transplant and it is currently used for donor allocation in United States.16

Statistical Analysis

Data were summarized using proportions, means ± SD, or median (interquartile range (IQR)) as appropriate. PS matching was used to account for baseline differences arising from dissimilarities in clinical and demographic characteristics of home HD and KTx patients. We created PS-matched cohorts for the overall cohort. STATA's “psmatch2” command suite was used to generate 1:1 PS-matched cohorts using nearest neighbor matching without replacement. The following variables were included in a logistic regression model to calculate the propensity scores: age, gender, race/ethnicity, primary insurance, type of vascular access at the time of transplantation/home HD, cause of ESRD, previous time with ESRD, body mass index, blood hemoglobin, serum albumin, comorbidities at baseline (diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, atherosclerotic heart disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, malignancy, and alcohol abuse). Home HD and KTx patients before and after matching were compared using standardized differences.17

Associations between renal replacement modalities (home HD vs. KTx) and all-cause mortality were assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and Cox proportional hazard models (for time to event analyses). Models in PS-matched cohorts were not additionally adjusted for covariates. For the main analyses, the start of the follow-up period was the start date of home HD modality or the date of kidney transplantation. Patients were followed until date of death, date of censoring [transfer to a different dialysis modality, kidney transplantation, transfer to a different facility or other reason for home HD patients; or date of allograft loss (re-transplantation, first date of dialysis) for KTx patients], or the end of the follow-up period (December 31st, 2011). In sensitivity analyses, we used an alternative censoring method where home HD patients were not censored at time of transfer to a different dialysis modality and continued to be followed until death, end of follow up, or other causes of censoring.

As a significant proportion of home HD patients were transplanted during the follow-up period, there is a potentially significant degree of informative censoring due to the selective removal of a healthier group of transplant eligible home HD patients. We therefore performed a competing risk model analyses to take this into account. Our event of interest was all-cause mortality and the competing event was kidney transplantation in the home HD group and graft loss in the KTx group. In our study we used the Fine and Gray model,18 which extends the Cox proportional hazards model to competing-risks data by considering the subdistribution hazard.

Finally, we also performed sensitivity analysis using the entire cohort population (n=13,306). In this Cox proportional hazards model we adjusted for the following confounders: age, gender, race/ethnicity, primary insurance, type of vascular access at the time of transplantation/home HD, cause of ESRD, previous time with ESRD, body mass index, blood hemoglobin, serum albumin, comorbidities at baseline (diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, atherosclerotic heart disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, malignancy, and alcohol abuse).

Effect modification by different patient characteristics was tested in the association of treatment modality with all-cause mortality. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata MP version 13 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) and SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of home HD and KTx patients before and after matching are shown in Table 1. Before matching, home HD patients were older, more likely to be male, diabetic, and white, had a higher prevalence of atherosclerotic heart disease, congestive heart failure, and other cardiovascular disease and had a higher serum albumin and shorter total ESRD time before modality initiation. After PS matching, all baseline variables were well balanced between home HD and KTx patients (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the unmatched and the 1:1 propensity score-matched cohort.

| Unmatched | Matched | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home HD | Kidney Tx | Std. Diff. | Home HD | Kidney Tx | Std. Diff. | |

| (n =638) | (n = 12,668) | (n=480) | (n=480) | |||

| Age (years) | 72 ± 6 | 69 ± 4 | 0.547 | 71 ± 6 | 71 ± 5 | 0.052 |

| Female (%) | 30 | 37 | -0.141 | 31 | 31 | 0.005 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| Whites | 84 | 62 | 0.262 | 81 | 79 | 0.054 |

| African-American | 9 | 19 | -0.315 | 11 | 12 | -0.039 |

| Asian | 4 | 11 | -0.244 | 4 | 4 | -0.068 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 6 | -0.282 | 2 | 3 | -0.010 |

| Other | 2 | 2 | 0.045 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Primary insurance (%) | ||||||

| Medicare | 71 | 65 | 0.496 | 71 | 70 | 0.027 |

| Medicaid | 1 | 8 | -0.312 | 1 | 1 | -0.024 |

| Other | 28 | 27 | 0.197 | 28 | 29 | -0.023 |

| Comorbid States (%) | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 66 | 44 | 0.450 | 61 | 59 | 0.025 |

| Alcohol abuse | 0 | 0.4 | -0.089 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| History of cancer | 7 | 4 | 0.111 | 7 | 8 | -0.048 |

| Hypertension | 70 | 64 | 0.139 | 74 | 74 | 0.005 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2 | 3 | -0.071 | 3 | 2 | 0.043 |

| Artherosclerotic Heart Disease | 32 | 11 | 0.539 | 27 | 29 | -0.037 |

| Congestive heart failure | 51 | 10 | 1.000 | 40 | 43 | -0.072 |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 28 | 9 | 0.514 | 23 | 24 | -0.046 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 9 | 2 | 0.294 | 7 | 8 | -0.020 |

| Access Type at time of Home HD initiation/time of KTx (%) | ||||||

| AV Fistula | 51 | 16 | 0.815 | 47 | 48 | -0.017 |

| AV Graft | 9 | 2 | 0.302 | 7 | 10 | -0.106 |

| Central Venous Catheter | 22 | 28 | -0.148 | 25 | 21 | 0.079 |

| Other/unknown | 18 | 54 | -0.809 | 21 | 21 | 0 |

| Cause of ESRD (%) | ||||||

| Diabetes | 40 | 36 | 0.089 | 40 | 38 | 0.034 |

| Hypertension | 27 | 27 | 0.010 | 27 | 27 | 0.005 |

| Glomerulonephritis | 12 | 13 | -0.036 | 12 | 13 | -0.044 |

| Cystic kidney disease | 3 | 8 | -0.199 | 3 | 4 | -0.046 |

| Other reason | 18 | 16 | 0.078 | 18 | 18 | 0.011 |

| Laboratory Tests at time of Home HD initiation/time of KTx | ||||||

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 0.473 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 0.018 |

| Blood hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.0 ± 1.2 | 10.5 ± 1.6 | 0.405 | 10.9 ±1.2 | 10.9 ± 1.5 | -0.014 |

| Other | ||||||

| Total ESRD time before modality initiation (days) | 332 ± 330 | 975 ± 936 | -0.916 | 465 ± 354 | 383 ± 344 | -0.054 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 29 ± 6 | 28 ± 6 | 0.061 | 29 ± 6 | 28 ± 6 | 0.032 |

Abbreviations: AV: Arterio-Venosus; ESRD: End Stage Renal Disease; Home HD: home hemodialysis; Kidney Tx: Kidney Transplant; Std Diff: Standardized Difference

Mortality in the PS matched cohort

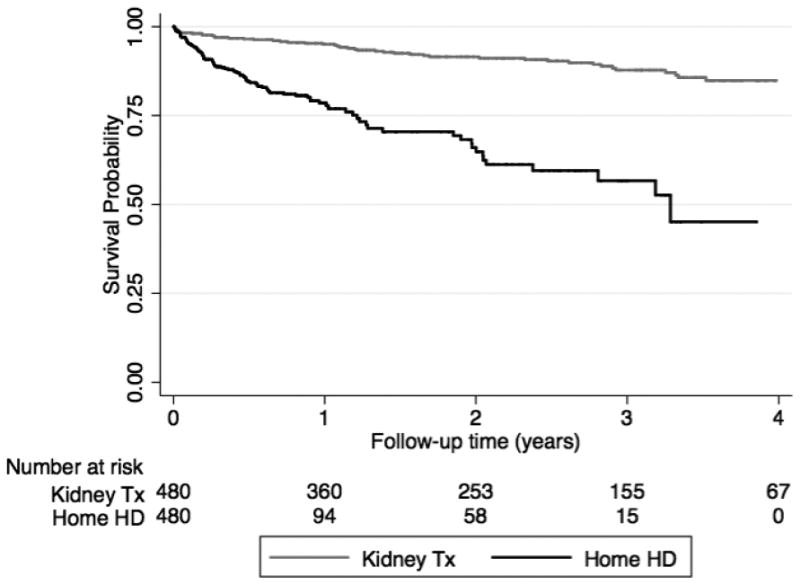

Median follow-up time was 205 days (IQR: 78-364 days) for home HD patients and 795 days (IQR: 366-1,221 days) for KTx recipients. There were 97 deaths (20%, mortality rate 253 [207-309]/1000 patient-years) in the home HD group, and 48 deaths (10%, 45 [34-60]/1000 patient-years) in the KTx group. Figure 2 shows the probability of 5-year survival of home HD and KTx patients in the PS matched group. Home HD patients had a 4.7 fold higher mortality risk compared to KTx patients (hazard ratio (HR): 4.74, 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.25-6.91) over the entire follow-up period. Similar results were seen in sensitivity analyses using alternative censoring (HR: 4.71, 95%CI: 3.25-6.84) (Figure S1) or competing risk regression (SHR: 4.71, 95%CI: 3.27-6.79) or in the entire cohort (Figure S3) after adjusment for important confounders (HR: 3.51, 95%CI: 2.82-4.36).

Figure 2. Association between renal replacement type (home hemodialysis (Home HD) versus kidney transplantation (Kidney Tx)) and mortality using Kaplan-Meiers curves in the propensity score matched cohort.

Abbreviations: Home HD: Home Hemodialysis; Kidney Tx: Kidney Transplant

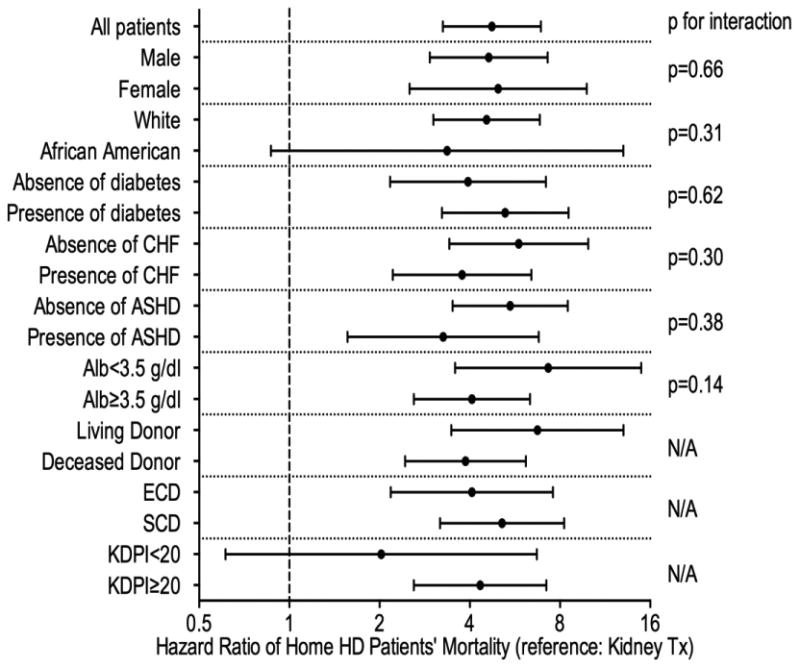

Mortality in the PS matched subcohorts

Figure 3 shows that home HD patients had higher mortality risk compared to KTx patients in all PS matched subcohorts, except in African-American patients and KTx recipients transplanted from donors with a KDPI<20. However, no significant effect modification was detected between different subgroups based on testing for interaction using interaction terms. Similar results were also seen in sensitivity analyses using alternative censoring (Figure S2) and in the entire cohort (Figure S4).

Figure 3. Mortality risk of home hemodialysis patients compared to kidney transplant recipients in groups of patients with different recipient and donor characteristics using the propensity score matched cohort.

Abbreviations: Alb: Serum Albumin; ASHD: Arthero-Sclerotic Heart Disease; CHF: Congestive Heart Failure; ECD: Extended Criteria Donor; Home HD: home hemodialysis; KDPI: Kidney Donor Profile Index; Kidney Tx: Kidney Transplant; N/A: Not Applicable; SCD: Standard Criteria Donor

Discussion

In this contemporary cohort of incident elderly home HD patients and elderly KTx recipients in the United States, we examined the association between type of renal replacement modality with all-cause mortality. Patients who received a KTx had significantly better survival regardless of recipient or donor characteristics.

There is an ongoing discussion about what the ideal renal replacement therapy (RRT) is for elderly ESRD patients, ranging from conservative treatment (no RRT) to kidney transplantation.19 Large epidemiological studies from different countries have shown that there is no significant difference in survival20-22 or quality of life23, 24 in elderly patients being treated with hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis. However, in United States, higher risk for death was showed in sub-groups of elderly patients treated with peritoneal dialysis compared to hemodialysis.25 Nevertheless, some studies suggest that compared to dialysis patients, elderly KTx recipients, and in particular recipients of expanded criteria deceased (ECD) donor kidneys, have greater survival.2-5, 26, 27 Moreover, a recent study showed that age is a strong, independent risk factor for death after KTx. Although lower mortality was observed with living kidney transplantation among elderly recipients, living-donor rates decrease with increasing recipient age.28

It has been argued that transplantation may offer substantial clinical benefits to older patients at a reasonable financial cost, especially if transplantation waiting times were short.5, 29-37 In a recent study including 2000 deceased-donor KTx recipients older than 70 years, elderly KTx recipients had a 41% lower mortality risk compared to elderly patients who remained on the KTx waitlist.3 Unfortunately, one of the largest studies comparing KTx recipients to waitlist patients in 230,000 dialysis patients did not include patients older than 70 years, but did show that mortality risk was significantly lower in KTx recipients (3.8 vs. 6.3/100 patient-years).5 KTx in the elderly can increase risk of infectious complications,38 and risk of early mortality due to a higher burden of comorbidity39. Older age may also be associated with different adaptive immuninity and pharmacokinetics,40 which can have negative effects on post-transplant survival.

Compared to the European system (elderly recipients are prioritized for elderly donor kidneys (“old for old” program)), where an effective allocation system has been developed and used for elderly patients;41 the new allocation system in the US penalizes older recipients, as their Estimated Post Transplant Survival (EPTS) score cannot be low. For example, the EPTS score of a 70 years old candidate without diabetes waiting for the first pre-emptive transplant is 55% (based on a reference population as of 9/30/2013), excluding this candidate from receiving the best quality donor kidney. Our results indicate that KTx is associated with a better chance of survival compared to home HD in elderly patients with ESRD, consequently KTx may still be the best choice of treatment regardless of age in patients with ESRD.

To the best of our knowledge no study has compared to date survival in elderly patient treated with home HD with that of KTx recipients. Home HD may provide certain advantages in elderly ESRD patients, including improved blood pressure control,42-45 reductions in total peripheral resistance and plasma norepinephrine levels,46 reduction in left ventricular mass,42, 45, 47, 48 better anemia49 and phosphorus control,45, 50-52 and better control of sleep disorders,53 which might diminish the previously described survival difference between KTx and regular dialysis patients.

In our study, despite all the potential benefits of home HD, elderly home HD patients had an almost 5-times higher risk of mortality compared to their KTx counterparts. Similar results were found in almost all subgroups of patients. Even elderly KTx recipients with ECD donors and severe comorbidity showed better survival than home HD patients with similar comorbidities. Prior studies in Canadian patients similarly showed a survival benefit of KTx compared to home HD.11, 13 However, the mean±SD age of the recent Canadian study was 45±13 years indicating that only few home HD patients were older than 65 years13, and therefore these results may not be applicable to elderly ESRD patients from the United States. Our study results confirm that KTx should remain the treatment of choice for elderly patients with ESRD, even compared to home HD.

Our study should be noted for a number of strengths. It is the first comparison of mortality for elderly home HD patients and KTx recipients from the United States. Secondly, our study used a PS-matched approach to balance measured confounders and to address potential confounding by indication and selection bias. We additionally performed sensitivity analyses with an alternate censoring method by continuing to follow patients after home HD therapy ended and also performed competing risk regression analyses to take into account so-called informative censoring, or the selective earlier censoring of healthier transplant eligible home HD patients. We also confirmed our primary result in sensitivity analyses performed in the entire cohort. Finally, we also examined associations across different subgroups of patients to test for potential effect modification by donor and recipient characteristics. Our results were consistent and robust across subgroups and in sensitivity analyses.

The results of our study should be interpreted in light of some potential limitations. First, we acknowledge that our sample size and event numbers in elderly home HD patients are small. However, to the best of our knowledge ours is the largest cohort of elderly home HD patients assembled to date and compares outcomes to a large cohort of elderly KTx recipients. Second, home HD data were derived from facilities operated by a single dialysis provider. However, patients from this provider constitute almost one-third of all patients undergoing maintenance dialysis in the United States. Third, the median follow-up time in home HD patients was relatively short. The main reason for this was that our home HD patients were transferred to other dialysis modalities after a relative short period of time. Further studies are needed to identify the cause of this observed phenomenon. Fourth, due to unavailable data, we were not able to analyze potential differences between hospitalization rate or quality of life outcomes in these patients. Furthermore, we did not have data regarding the home HD patients' wait-list status, and consequently we were not able to perform subgroup analysis in this subcohort. Fifth, our result may not be applicable to populations outside the US, as the nocturnal home hemodialysis practice is significantly different in Australia, Canada or Europe. Moreover, the dialysis and transplant outcomes are inferior in the US compared to Europe. Lastly, despite the fact that we were able to PS match our cohorts for many confounding factors, our study results may still have been subjected to residual confounding due to unmeasured or unknown confounders.

Conclusion

In conclusion, KTx is associated with a better chance of survival compared to home HD in elderly patients with ESRD. Further studies are needed to assess whether KTx also provides better quality of life or lower hospitalization rates compared to home HD in elderly patients with ESRD.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Association between renal replacement type (home hemodialysis (Home HD) versus kidney transplantation (Kidney Tx)) and mortality using Kaplan-Meiers curves in the propensity score matched cohort and using alternative censoring method

Abbreviations: Home HD: Home Hemodialysis; Kidney Tx: Kidney Transplant

Figure S2: Mortality risk of home hemodialysis patients compared to kidney transplant recipients in groups of patients with different recipient and donor characteristics using the propensity score matched cohort and alternative censoring method

Abbreviations: Alb: Serum Albumin; ASHD: Arthero-Sclerotic Heart Disease; CHF: Congestive Heart Failure; ECD: Extended Criteria Donor; Home HD: home hemodialysis; KDPI: Kidney Donor Profile Index; Kidney Tx: Kidney Transplant; N/A: Not Applicable; SCD: Standard Criteria Donor

Figure S3: Association between renal replacement type (home hemodialysis (Home HD) versus kidney transplantation (Kidney Tx)) and mortality using Kaplan-Meiers curves in the entire patients' cohort (n=13,306)

Abbreviations: Home HD: Home Hemodialysis; Kidney Tx: Kidney Transplant

Figure S4: Mortality risk of home hemodialysis patients compared to kidney transplant recipients in groups of patients with different recipient and donor characteristics using the entire patients' cohort (n=13,306)

Abbreviations: Alb: Serum Albumin; ASHD: Arthero-Sclerotic Heart Disease; CHF: Congestive Heart Failure; ECD: Extended Criteria Donor; Home HD: home hemodialysis; KDPI: Kidney Donor Profile Index; Kidney Tx: Kidney Transplant; N/A: Not Applicable; SCD: Standard Criteria Donor

Acknowledgments

The abstract of the paper is accepted for poster presentation at the ASN and also for ASN news release.

Funding Sources: The work in this manuscript has been performed with the support of grant R21AG047306 and R01DK95668 (MZM, KKZ, CPK and RM).

Sponsor's Role: The research was independent from the Sponsor (NIH). The Sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of paper

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

Disclosures: CPK and KKZ are employees of the Department of Veterans affairs. Opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors' and do not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The results of this paper have not been published previously in whole or part.

Author Contributions: The contribution of the authors is detailed as follows:

Miklos Z Molnar contributed to analysis of the data, interpretation of data and writing the manuscript.

Vanessa Ravel contributed to analysis of the data.

Elani Streja contributed to analysis of the data and writing the manuscript.

Csaba P Kovesdy contributed to interpretation of data and writing the manuscript.

Matthew B. Rivara contributed to interpretation of data and writing the manuscript.

Rajnish Mehrotra contributed to analysis of the data, contributed to interpretation of data and writing the manuscript.

Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh contributed to analysis of the data, contributed to interpretation of data and writing the manuscript.

References

- 1.US Renal Data System, USRDS 2012 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson DW, Herzig K, Purdie D, et al. A comparison of the effects of dialysis and renal transplantation on the survival of older uremic patients. Transplantation. 2000;69:794–799. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200003150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao PS, Merion RM, Ashby VB, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Kayler LK. Renal transplantation in elderly patients older than 70 years of age: results from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2007;83:1069–1074. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000259621.56861.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savoye E, Tamarelle D, Chalem Y, Rebibou JM, Tuppin P. Survival benefits of kidney transplantation with expanded criteria deceased donors in patients aged 60 years and over. Transplantation. 2007;84:1618–1624. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000295988.28127.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1725–1730. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molnar-Varga M, Molnar MZ, Szeifert L, et al. Health-related quality of life and clinical outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:444–452. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Renal Data System, 2014 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall MR, Hawley CM, Kerr PG, et al. Home hemodialysis and mortality risk in Australian and New Zealand populations. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:782–793. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinhandl ED, Liu J, Gilbertson DT, Arneson TJ, Collins AJ. Survival in daily home hemodialysis and matched thrice-weekly in-center hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:895–904. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011080761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nesrallah GE, Lindsay RM, Cuerden MS, et al. Intensive hemodialysis associates with improved survival compared with conventional hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:696–705. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011070676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pauly RP, Gill JS, Rose CL, et al. Survival among nocturnal home haemodialysis patients compared to kidney transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2915–2919. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pauly RP. Nocturnal home hemodialysis and short daily hemodialysis compared with kidney transplantation: emerging data in a new era. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2009;16:169–172. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tennankore KK, Kim SJ, Baer HJ, Chan CT. Survival and hospitalization for intensive home hemodialysis compared with kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2113–2120. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013111180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saxena R, Yu X, Giraldo M, et al. Renal transplantation in the elderly. Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41:195–210. doi: 10.1007/s11255-008-9489-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuttykrishnan S, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Arah OA, et al. Predictors of treatment with dialysis modalities in observational studies for comparative effectiveness research. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao PS, Schaubel DE, Guidinger MK, et al. A comprehensive risk quantification score for deceased donor kidneys: the kidney donor risk index. Transplantation. 2009;88:231–236. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ac620b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28:3083–3107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fine J, Gray R. A proportional hazards model for subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of American Statistical Association. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger JR, Hedayati SS. Renal replacement therapy in the elderly population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1039–1046. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10411011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamping DL, Constantinovici N, Roderick P, et al. Clinical outcomes, quality of life, and costs in the North Thames Dialysis Study of elderly people on dialysis: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2000;356:1543–1550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Couchoud C, Moranne O, Frimat L, Labeeuw M, Allot V, Stengel B. Associations between comorbidities, treatment choice and outcome in the elderly with end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:3246–3254. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jassal SV, Trpeski L, Zhu N, Fenton S, Hemmelgarn B. Changes in survival among elderly patients initiating dialysis from 1990 to 1999. CMAJ. 2007;177:1033–1038. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris SA, Lamping DL, Brown EA, Constantinovici N North Thames Dialysis Study G. Clinical outcomes and quality of life in elderly patients on peritoneal dialysis versus hemodialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2002;22:463–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown EA, Johansson L, Farrington K, et al. Broadening Options for Long-term Dialysis in the Elderly (BOLDE): differences in quality of life on peritoneal dialysis compared to haemodialysis for older patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:3755–3763. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehrotra R, Chiu YW, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Bargman J, Vonesh E. Similar outcomes with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:110–118. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oniscu GC, Brown H, Forsythe JL. How great is the survival advantage of transplantation over dialysis in elderly patients? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:945–951. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giessing M, Budde K, Fritsche L, et al. “Old-for-old” cadaveric renal transplantation: surgical findings, perioperative complications and outcome. Eur Urol. 2003;44:701–708. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karim A, Farrugia D, Cheshire J, et al. Recipient age and risk for mortality after kidney transplantation in England. Transplantation. 2014;97:832–838. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000438026.03958.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jassal SV, Krahn MD, Naglie G, et al. Kidney transplantation in the elderly: a decision analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:187–196. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000042166.70351.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong G, Howard K, Chapman JR, et al. Comparative survival and economic benefits of deceased donor kidney transplantation and dialysis in people with varying ages and co-morbidities. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnuelle P, Lorenz D, Trede M, Van Der Woude FJ. Impact of renal cadaveric transplantation on survival in end-stage renal failure: evidence for reduced mortality risk compared with hemodialysis during long-term follow-up. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:2135–2141. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9112135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Port FK, Wolfe RA, Mauger EA, Berling DP, Jiang K. Comparison of survival probabilities for dialysis patients vs cadaveric renal transplant recipients. JAMA. 1993;270:1339–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ojo AO, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Mauger EA, Williams L, Berling DP. Comparative mortality risks of chronic dialysis and cadaveric transplantation in black end-stage renal disease patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;24:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rabbat CG, Thorpe KE, Russell JD, Churchill DN. Comparison of mortality risk for dialysis patients and cadaveric first renal transplant recipients in Ontario, Canada. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:917–922. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V115917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meier-Kriesche HU, Ojo AO, Port FK, Arndorfer JA, Cibrik DM, Kaplan B. Survival improvement among patients with end-stage renal disease: trends over time for transplant recipients and wait-listed patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1293–1296. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1261293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oniscu GC, Brown H, Forsythe JL. Impact of cadaveric renal transplantation on survival in patients listed for transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1859–1865. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gill JS, Tonelli M, Johnson N, Kiberd B, Landsberg D, Pereira BJ. The impact of waiting time and comorbid conditions on the survival benefit of kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2345–2351. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meier-Kriesche HU, Ojo A, Hanson J, et al. Increased immunosuppressive vulnerability in elderly renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2000;69:885–889. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200003150-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kauffman HM, McBride MA, Cors CS, Roza AM, Wynn JJ. Early mortality rates in older kidney recipients with comorbid risk factors. Transplantation. 2007;83:404–410. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000251780.01031.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang E, Segev DL, Rabb H. Kidney transplantation in the elderly. Semin Nephrol. 2009;29:621–635. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frei U, Noeldeke J, Machold-Fabrizii V, et al. Prospective age-matching in elderly kidney transplant recipients--a 5-year analysis of the Eurotransplant Senior Program. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:50–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan CT, Floras JS, Miller JA, Richardson RM, Pierratos A. Regression of left ventricular hypertrophy after conversion to nocturnal hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2235–2239. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lockridge RS, Jr, Spencer M, Craft V, et al. Nightly home hemodialysis: five and one-half years of experience in Lynchburg, Virginia. Hemodial Int. 2004;8:61–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1492-7535.2004.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGregor DO, Buttimore AL, Lynn KL, Nicholls MG, Jardine DL. A Comparative Study of Blood Pressure Control with Short In-Center versus Long Home Hemodialysis. Blood Purif. 2001;19:293–300. doi: 10.1159/000046957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rocco MV, Lockridge RS, Jr, Beck GJ, et al. The effects of frequent nocturnal home hemodialysis: the Frequent Hemodialysis Network Nocturnal Trial. Kidney Int. 2011;80:1080–1091. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chan CT, Harvey PJ, Picton P, Pierratos A, Miller JA, Floras JS. Short-term blood pressure, noradrenergic, and vascular effects of nocturnal home hemodialysis. Hypertension. 2003;42:925–931. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000097605.35343.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Susantitaphong P, Koulouridis I, Balk EM, Madias NE, Jaber BL. Effect of frequent or extended hemodialysis on cardiovascular parameters: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:689–699. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Culleton BF, Walsh M, Klarenbach SW, et al. Effect of frequent nocturnal hemodialysis vs conventional hemodialysis on left ventricular mass and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1291–1299. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.11.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chan CT, Liu PP, Arab S, Jamal N, Messner HA. Nocturnal hemodialysis improves erythropoietin responsiveness and growth of hematopoietic stem cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:665–671. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008050498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jaber BL, Lee Y, Collins AJ, et al. Effect of daily hemodialysis on depressive symptoms and postdialysis recovery time: interim report from the FREEDOM (Following Rehabilitation, Economics and Everyday-Dialysis Outcome Measurements) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:531–539. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walsh M, Manns BJ, Klarenbach S, Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn B, Culleton B. The effects of nocturnal compared with conventional hemodialysis on mineral metabolism: A randomized-controlled trial. Hemodial Int. 2010;14:174–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2009.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pellicano R, Strauss BJ, Polkinghorne KR, Kerr PG. Body composition in home haemodialysis versus conventional haemodialysis: a cross-sectional, matched, comparative study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:568–573. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hanly PJ, Pierratos A. Improvement of sleep apnea in patients with chronic renal failure who undergo nocturnal hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:102–107. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101113440204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Association between renal replacement type (home hemodialysis (Home HD) versus kidney transplantation (Kidney Tx)) and mortality using Kaplan-Meiers curves in the propensity score matched cohort and using alternative censoring method

Abbreviations: Home HD: Home Hemodialysis; Kidney Tx: Kidney Transplant

Figure S2: Mortality risk of home hemodialysis patients compared to kidney transplant recipients in groups of patients with different recipient and donor characteristics using the propensity score matched cohort and alternative censoring method

Abbreviations: Alb: Serum Albumin; ASHD: Arthero-Sclerotic Heart Disease; CHF: Congestive Heart Failure; ECD: Extended Criteria Donor; Home HD: home hemodialysis; KDPI: Kidney Donor Profile Index; Kidney Tx: Kidney Transplant; N/A: Not Applicable; SCD: Standard Criteria Donor

Figure S3: Association between renal replacement type (home hemodialysis (Home HD) versus kidney transplantation (Kidney Tx)) and mortality using Kaplan-Meiers curves in the entire patients' cohort (n=13,306)

Abbreviations: Home HD: Home Hemodialysis; Kidney Tx: Kidney Transplant

Figure S4: Mortality risk of home hemodialysis patients compared to kidney transplant recipients in groups of patients with different recipient and donor characteristics using the entire patients' cohort (n=13,306)

Abbreviations: Alb: Serum Albumin; ASHD: Arthero-Sclerotic Heart Disease; CHF: Congestive Heart Failure; ECD: Extended Criteria Donor; Home HD: home hemodialysis; KDPI: Kidney Donor Profile Index; Kidney Tx: Kidney Transplant; N/A: Not Applicable; SCD: Standard Criteria Donor