Abstract

Tomato wilt pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici (Fol) is grouped into three races based on their pathogenicity to different host cultivars. Rapid detection and discrimination of Fol races in field soils is important to prevent tomato wilt disease. Although five types of point mutations in secreted in xylem 3 (SIX3) gene, which are characteristic of race 3, have been reported as a molecular marker for the race, detection of these point mutations is laborious. The aim of this study is to develop a rapid and accurate method for the detection of point mutations in SIX3 of Fol. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of SIX3 gene with the universal QProbe as well as two joint DNAs followed by annealing curve analysis allowed us to specifically detect Fol and discriminate race 3 among other races in about one hour. Our developed method is applicable for detection of races of other plant pathogenic fungi as well as their pesticide-resistant mutants that arise through point mutations in a particular gene.

Introduction

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici (Fol) is a causal agent of tomato wilt. Fol invades tomato roots, colonizes vessels and finally kills the host plants. Fol has three races, which are classified based on virulence on tomato cultivars carrying different resistant genes (Immunity: I)1. Cultural control of Fol race 3 is laborious because there is no commercial tomato cultivar that is resistant against the race. Tomato rootstock carrying I, I2 and I3 or soil disinfection are needed to control outbreak of race 3. Since its first occurrence in Australia in 1978, Fol race 3 has been reported from other areas including the United States, Mexico and Brazil2–8. In Japan, Fol race 3 was firstly isolated in Fukuoka prefecture in 19979, followed by its occurrences in Hokkaido, Kumamoto, Kochi, Aomori and other prefectures10, 11. Under these situations, stable tomato production requires earlier detection and discrimination of Fol races for the selection of appropriate resistant cultivars and rootstocks.

Fol has race-specific avirulence (AVR) genes. Recent studies have identified some of the small secreted proteins of Fol in tomato xylem (secreted in xylem: SIX) as products of AVR genes12–14. As SIX4, SIX3 and SIX1 were recognized by I/I-1, I2 and I3, each SIX protein was designated as AVR1, AVR2 and AVR3, respectively12–14. While Fol race 1, which harbors SIX4 (AVR1), cannot infect tomato cultivars possessing I or I-1(I/I-1) due to the recognition of SIX4 by I or I-1, races 2 and 3 can break this resistance by escaping recognition by I/I-1 based on the mutation in their SIX4 gene, such as deletions and transposon insertions in its open reading frame11, 13, 15. Fol races 1 and 2 cannot exhibit virulence on I/I-1 I2 tomato cultivars because I2 recognizes SIX3 (AVR2) expressed by both races. However, Fol race 3 can infect I/I-1 I2-harboring cultivars since a single point mutation (G121A, G134A or G137C) in its SIX3 gene evades I2-mediated resistance14. In addition to these three reported mutation types, two new types of a single point mutation (T122A or C146T) in the SIX3 have been recently found from Fol race 3 isolates in Japan (Akai et al., in preparation). Collectively, AVR genes of Fol have diverse types of mutations that cause race differentiation. Therefore, identifying mutation types of AVR genes of Fol is important for determination of its races.

PCR- or real-time PCR-mediated Fol race distinction method has been developed by targeting their AVR genes16, 17. This allowed discrimination between Fol race 1 and other races by detection of SIX4, as well as identification of Fol race 3 by primers that can detect either of the three types of single nucleotide substitutions (G121A, G134A or G137C) in SIX3. To improve rapidity and sensitivity of Fol race distinction, we have recently developed a loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) method targeting SIX4 unique to race 118. However, LAMP has never been applied to the discrimination of Fol race 3 from other races, which needs detection of point mutations in SIX3.

In order to detect single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) by LAMP, one approach is to use an inner primer possessing a specific 3′- or 5′-terminal nucleotide that anneals to the corresponding SNP site, which allows specific amplification of a target gene containing SNPs19–25. However, this method is costly, because it needs a different inner primer for detection of different types of mutations of the target gene.

Using quenching probe (QProbe) could be another approach for detection of SNPs by LAMP. QProbe is a single-stranded nucleotide, the 5′ end of which is a cytosine labeled with a fluorophore such as BODIPY or fluorescein26, 27. When QProbe hybridizes with its target nucleotide sequence, the fluorescence is quenched by electron transfer between the fluorophore and a guanine residue in the target. The fluorescence of QProbe is recovered upon its dissociation from the target. These properties of QProbe allow it to be used for SNP typing in combination with real-time PCR and subsequent melting curve analysis26. In other words, one can determine whether there are SNPs or not by analyzing melting temperature of QProbe, which will be lower with a target sequence containing a mismatch with the QProbe, compared to a perfect match sequence. However, detection of different SNPs in a relatively distant region of the same gene requires additional synthesis of the fluorescent QProbe, which is costly and time-consuming. To alleviate this problem, universal QProbe system has been developed28. This method uses a universal QProbe combined with a joint DNA, instead of a single, target region-specific QProbe. Nucleotide sequences of a universal QProbe can be fixed because a joint DNA is designed to contain two combined sequences complementary to both a target region and a universal QProbe. Therefore, this method is less time-consuming and more cost-effective.

In this study, we tried to apply the universal QProbe system to LAMP in order to detect five types point mutations of SIX3 in Fol race 3. This is the first report of the successful combination of LAMP and the universal QProbe, which achieved rapid discrimination of Fol race 3 from other two races.

Results

Design of LAMP primer set and joint DNAs, and optimization of LAMP conditions

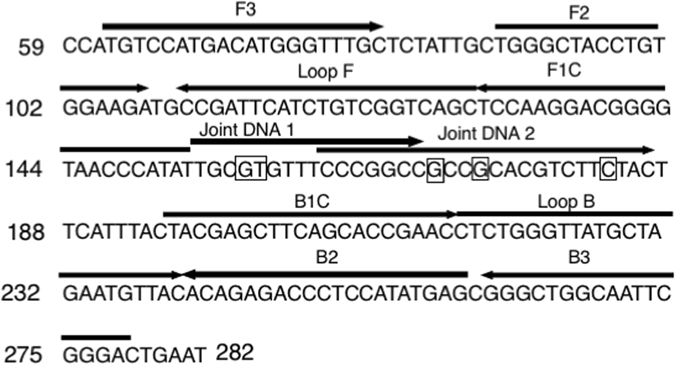

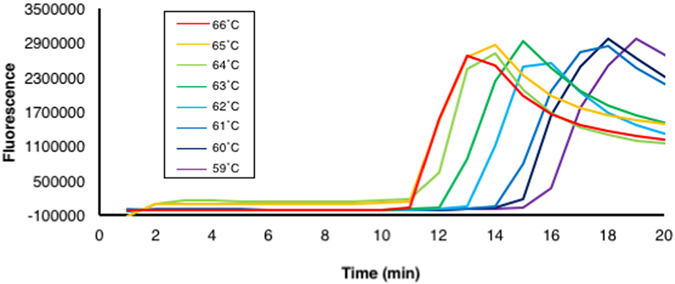

To distinguish Fol race 3 from other races by LAMP combined with the universal QProbe system, a primer set for a basic LAMP method was designed based on the SIX3 nucleotide sequence (GenBank accession number: AM234063.1) (Fig. 1, Table 1). Joint DNA1 and 2 were designed to hybridize to nt 113–129 and 127–149, respectively, with respect to a translation initiation codon of SIX3. Before determination of melting temperatures of the two joint DNAs combined with the universal QProbe, we examined optimal reaction temperature for LAMP by the SIX3 primer set without the QProbe and joint DNAs. When LAMP was performed with genomic DNA (gDNA) (30 ng) of Fol race 1 (MAFF 103036) in the range of 59 to 66 °C, the reaction at 65 or 66 °C showed the most rapid increase in the fluorescence intensity in about 10 min (Fig. 2). Thus, all subsequent LAMP assays were performed at 66 °C.

Figure 1.

Design of LAMP primers and joint DNAs Partial SIX3 nucleotide sequences (positions 59 to 282) used for designing LAMP primers and joint DNAs. Positions of the designed primers and joint DNAs are indicated by arrows. Point mutation sites are shown by an open box.

Table 1.

Melting temperatures of Joint DNAs.

| Strains | Origin | SIX3 mutation types | Annealing temperature (arithmetic mean °C ± standard deviation) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint DNA1 | Joint DNA2 | ||||

| Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 1 | MAFF 103036 | Japan | None | 59.3 ± 0.2 | 71.6 ± 0.5 |

| MAFF 305121 | Japan | None | 61.1 ± 1.2 | 72.4 ± 0.4 | |

| race 2 | JCM 12575 | Japan | None | 60.7 ± 1.0 | 71.7 ± 0.3 |

| 4287 | Spain | None | 60.4 ± 2.2 | 73.1 ± 0.3 | |

| race 3 | Chz1-A | Japan | G121A | 53.2* ± 0.4 | 72.3 ± 0.9 |

| KoChi-1 | Japan | G121A | 53.7* ± 1.1 | 70.2 ± 0.0 | |

| FolyA007 | Japan | T122A | 54.6* ± 1.0 | 71.9 ± 0.1 | |

| F240 | USA | G134A | 60.1 ± 1.0 | 65.5* ± 1.8 | |

| 40-1 | Japan | C146T | 61.6 ± 2.0 | 39.3* ± 0.5 | |

| KC0071 | Japan | C146T | 60.2 ± 0.0 | 40.3* ± 0.5 | |

| F. oxysporum f. sp. batatas | MAFF 103070 | Japan | — | — | — |

| F. oxysporum f. sp. conglutinans | Cong:1-1 | Japan | — | — | — |

| F. oxysporum f. sp. nicotianae | ATCC 15645 | Greece | — | — | — |

| F. oxysporum f. sp. radicis-lycopersici | MAFF 103044 | Japan | — | — | — |

| F. oxysporum | Fo304 | Japan | — | — | — |

| F. sacchari | FGSC 7611 | USA | — | — | — |

| Alternaria solani | AS2 | Japan | — | — | — |

| Verticillium dahliae | 910312a-3 | Japan | — | — | — |

| plasmid DNA | pSIX3 G137C | G137C | 59.7 ± 0.1 | 63.8* ± 0.5 | |

+, Detection −, no detection *, relatively low melting temperature of each joint DNA.

Figure 2.

Optimization of LAMP reaction temperature with the designed SIX3 primer sets. LAMP was performed with DNA of Fol race 1 at different temperatures from 59 to 66 °C for 20 min. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments.

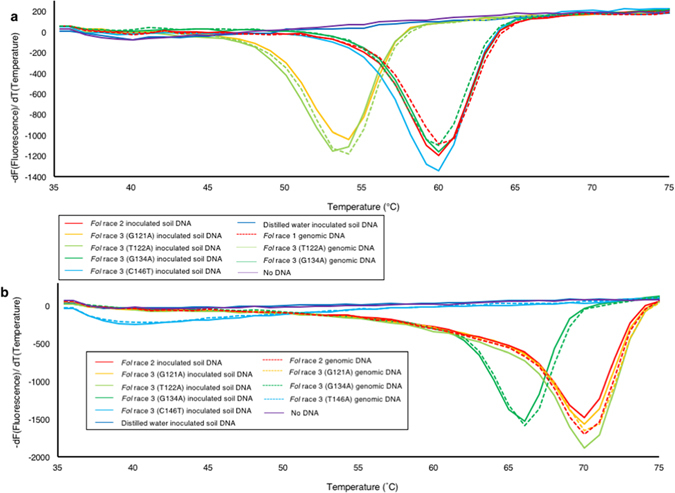

Detection of a point mutation in SIX3 by LAMP reaction with the universal QProbe system

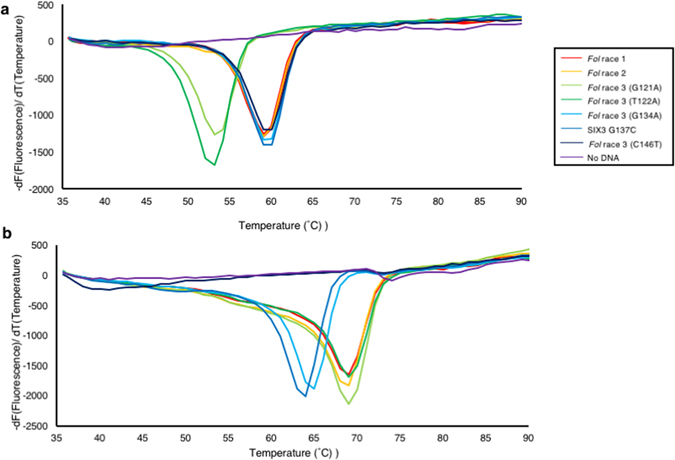

To test the specificity of the designed primer set and joint DNAs, we performed LAMP reactions with the QProbe and Joint DNA 1 or 2 using gDNA (30 ng) of two isolates of Fol race 1, two of Fol race 2, six of Fol race 3 harboring a single point mutation (two for G121A, one T122A, one G134A or two T146A) in SIX3, four of other f. spp., and one of nonpathogenic Fusarium oxysporum, and two of other fungal species. We also tested plasmid DNA (3 ng) containing a SIX3 sequence with another type of single point mutation (G137C), which has not been found in Japan at present. Melting curve analysis following 60 min of LAMP reaction with Joint DNA 1 showed that the negative derivative of fluorescence over temperature produced a single peak at about 60 °C when gDNA of Fol race 1, race 2, race 3 (G134A or C146T) or the plasmid DNA (G137C) was used as a template (Fig. 3a, Table 2). On the other hand, a single peak at about 53 °C was observed when gDNA of Fol race 3 with a mutation type G121A or T122A was used as a template (Fig. 3a, Table 2). Melting curve analysis following LAMP reaction with Joint DNA 2 produced a single peak at about 70 °C when using gDNA of Fol race 1, race 2, or race 3 with a mutation type G121A or T122A, and a single peak at about 65 °C when using Fol race 3 with a mutation type G134A or plasmid DNA with a G137C mutation in SIX3 (Fig. 3b, Table 2). In this case with Joint DNA 2, a weak single peak at about 40 °C was produced when gDNA of Fol race 3 with a mutation type C146T was used as a template. It should be noted that, because we successfully observed a clear peak at 60 °C with Joint DNA 1 when C146T was used as a template, this weak peak observed with Joint DNA 2 might be due to weak annealing of the amplified product of SIX3 of Fol race 3 (C146T) with Joint DNA 2, but not due to failure of amplification. In contrast, no peak was observed by melting curve analysis with Joint DNA 1 or 2 when gDNA of the other f. spp. or non-pathogenic isolates of F. oxysporum, that of other fungal species, or water was used as a template, suggesting that the SIX3 primers are highly specific and do not generate any amplification products when LAMP reaction does not contain DNA of Fol. These results indicated that our LAMP method with the universal QProbe system could not only distinguish between Fol race 3 and other races and species, but also specifically identify Fol race 3 harboring C146T in SIX3.

Figure 3.

Melting temperature of joint DNAs combined with the universal QProbe. Melting curve analysis with Joint DNA 1 (a) or Joint DNA 2 (b) was performed from 35 to 90 °C following 60 min of LAMP reactions using genomic DNAs of Fol isolates of different races as a template. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments.

Table 2.

Primers and joint DNAs used in this study.

| Primer | Sequences 5′-3′ | Use | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIX3-F3 | TGTCCATGACATGGGTTTGC | SIX3 detection | This study |

| SIX3-B3 | CAGTCCCGAATTGCCAGC | This study | |

| SIX3-FIP | TATGGGTTACCCCGTCCTTGGA-TGGGCTACCTGTGGAAGA | This study | |

| SIX3-BIP | ACGAGCTTCAGCACCGAACC-CGCTCATATGGAGGGTCTCT | This study | |

| SIX3-LF | GCTGACCGACAGATGAATCGG | This study | |

| SIX3-LB | TCTGGGTTATGCTAGAATGTTACAC | This study | |

| Joint DNA 1 | TGCGTGTTTCCCGGCC - UQprobe* | This study | |

| Joint DNA 2 | CCCGGCCGCCGCACGTCTTCTAC - UQprobe* | This study | |

| SIX3 F | TATATTACCGACCATCTTGCCTAAACATTTACCA | SIX3 mutagenesis | This study |

| SIX3 R | GCCAAGGGGAACTGCCACAG | This study | |

| G137CF | TGCGTGTTTCCCGGCCGCCCCACGTCTTCTACTTCATTTACTA | This study | |

| G137CR | AAATGAAGTAGAAGACGTGGGGCGGCCGGGAAACACGCAAT | This study | |

| SIX4 F | ACTCGTTGTTATTGCTTCGG | SIX4 detection | Inami et al.11 |

| SIX4 R | CGGAGTGAAGAAGAAGCTAA | Inami et al.11 | |

| SIX4-F3 | TCCAGTTGGAGCAAGTTGG | Ayukawa et al.18 | |

| SIX4-B3 | TGCCCGTCTCTGCGATAG | Ayukawa et al.18 | |

| SIX4-FIP | GCCTCCTTGTCATCTACCGCATTTGGGGTGATAGAGAGCCTG | Ayukawa et al.18 | |

| SIX4-BIP | ATGGCAAAGTTGTCACGCGTGTTGGGCCTTGAGTCGAATG | Ayukawa et al.18 | |

| SIX4-LF | GACGGAGAGCAAGTAGCGT | Ayukawa et al.18 | |

| SIX4-LB | CAGGAAAGCCAGGAATAGGACGA | Ayukawa et al.18 |

*3′ ends of joint DNAs consist of UQprobe-G complementary sequences

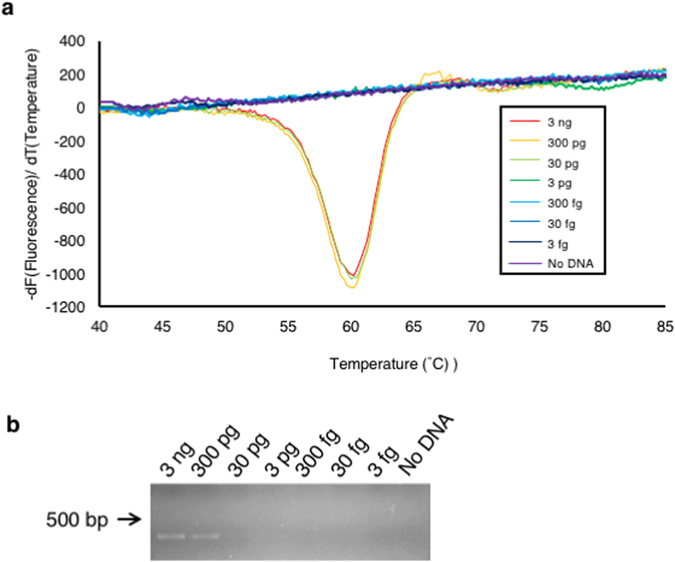

Comparative sensitivity test of LAMP and PCR

To compare the sensitivity of our LAMP method with the conventional PCR, LAMP reaction with the QProbe and the Joint DNA 1, as well as the conventional PCR using outer primers of the LAMP primer set, was performed using a 10-fold dilution series of Fol race 1 gDNA, from 3 ng to 3 fg, as a template. In the melting curve analysis following LAMP reaction, the derivative of fluorescence over temperature produced a peak at about 60 °C when 3 ng to 30 pg of DNA was used, while it does not produce any peaks when 3 pg or less DNA was used (Fig. 4a). However, with a template of 3 ng to 300 pg of gDNA, the conventional PCR with the outer primers of LAMP produced amplification products of SIX3 (Fig. 4b). These results showed that the sensitivity of our LAMP method with the QProbe and the joint DNA was 10-fold higher than that of PCR.

Figure 4.

Comparison of relative sensitivity of LAMP with the universal QProbe and conventional PCR (a) Melting curve analysis following LAMP reaction with serial tenfold dilutions of genomic DNA of Fol race 1 (3 ng to 3 fg) using Joint DNA 1. (b) Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products amplified from the same dilutions of genomic DNA with SIX3-F3 and SIX3-B3 primers.

Detection of Fol race 3 from artificially infested soil

To examine the utility of our LAMP method for typing of Fol races in the soil, DNA extracted from artificially Fol-infested soil was used for LAMP reaction with the QProbe and the joint DNA. Melting temperature of Joint DNA 1 combined with the QProbe was about 54 °C when DNA from soil infested with Fol race 3 (with a mutation type G121A or T122A) was used as a template for LAMP reaction, which was lower than that observed when DNA from soil infested with race 3 isolates with other mutation types (G134A and C146T) was used (about 60 °C) (Fig. 5a). On the other hand, melting temperature of Joint DNA 2 combined with the QProbe was about 66 and 40 °C when using DNA extracted from soil infested with Fol race 3 of a mutation type G134A and T146A, respectively (Fig. 5b). Accordingly, our method could detect Fol race 3 and distinguish it from other races even when using the artificially infested soil DNA.

Figure 5.

Typing of Fol races in artificially infested soil by LAMP using the universal QProbe with joint DNAs. Melting curve analysis of LAMP products using the QProbe combined with Joint DNA 1 (a) and Joint DNA 2 (b). Genomic DNAs of Fol or artificial infested soil DNAs by Fol were used as a template. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments.

Detection of Fol race 3 from naturally infested soil

We compared the reliability of our method with that of conventional PCR using soil DNA from two fields (Soil DNAs 1 and 2), which have a history of tomato wilt occurrence by Fol race 3 (KoChi-1; G121A in SIX3) in 2012 and 2013 (Table 3). Melting temperatures between the LAMP products of both Soil DNA 1 and 2 and the Joint DNA 1 and 2 with the QProbe were in good agreement with that obtained when fungal gDNA of KoChi-1 was used (Table 3). These results suggested that Soil 1 and 2 are infested with Fol race 3 isolates carrying G121A or T122A. In contrast, a peak of the derivative of fluorescence over melting temperature was not produced when Soil DNA 3 and 4, which were extracted from rhizosphere soil of healthy tomato plants, were used as a template (Table 3). On the other hand, the conventional PCR with SIX3 outer primers did not generate amplification from any of the four soil DNAs (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. S1), suggesting that LAMP is more sensitive than the conventional PCR when soil DNA was used as a template.

Table 3.

Comparison of molecular detection for Fol race 3 from field soil of Kochi prefecture.

| Sample | Sampled date | Symptom | Location | LAMP with the universal QProbe | LAMP | PCR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melting temperature (arithmetic mean °C ± standard deviation) | ||||||||

| Joint DNA 1 | Joint DNA 2 | SIX4 | SIX3 | SIX4 | ||||

| DNA of KoChi-1 | — | — | — | 53.5 ± 0.2 | 70.1 ± 0.3 | + | + | + |

| Soil DNA 1 | 2012.5 | Yes | N33°31′92″ E133°21′97.1″ | 53.4 ± 0.4 | 70.0 ± 0.1 | + | — | + |

| Soil DNA 2 | 2013.5 | Yes | N33°31′50.28″ E133°22.01′66″ | 53.8 ± 0.2 | 69.7 ± 0.4 | + | — | — |

| Soil DNA 3 | 2012.11 | No | N33°31′92″ E133°21′97.1″ | — | — | — | — | — |

| Soil DNA 4 | 2014.11 | No | N33°31′50.28″ E133°22.01′66″ | — | — | +a | — | — |

+, detection −, no detection a, LAMP products were obtained only once in three replicates.

To further characterize the race 3 isolates detected from the Soil 1 and 2, we tried to detect their SIX4 gene, because we have previously reported that the SIX4 gene of the original KoChi-1 isolate is disrupted by a transposon insertion11. For this purpose, we employed the conventional LAMP developed in the previous study18, as well as the conventional PCR. LAMP products with the SIX4 primer set were obtained in three independent reactions when Soil DNA 1 and DNA 2 were used as a template (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. S1). By contrast, a PCR product of SIX4 was only obtained from the Soil DNA 1 (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. S1), whose molecular size (about 1500 bp) was almost the same as a PCR product of the SIX4 of the original KoChi-1 isolate, which was inserted with a Hormin transposon (Supplementary Fig. S1). These results by the conventional LAMP and PCR suggested the existence of race 3 isolates KoChi-1 in the tested soil, which supported the results of LAMP using the universal QProbe system.

Discussion

We developed a novel LAMP method with the universal QProbe for detecting five different types of point mutations in SIX3, which is characteristic of race 3 of the tomato wilt fungus (Fol), and could distinguish race 3 from races 1 and 2. Our method is more accurate and rapid for detecting Fol race 3 than other methods based on conventional PCR. PCR targeting polygalacturonase genes or rDNA intergenic spacer region did not completely discriminate Fol race 3 from other races or f. spp.17, 29, because phylogeny based on these genes does not strictly correlate with races of Fol. Although Lievens et al.16 have developed a PCR-mediated method for detecting Fol race 3 based on point mutations in SIX3, a race-determining gene, it can only detect three (G121A, G134A and G137C) out of the five types of point mutations found in race 3. Besides, this PCR-mediated detection takes two to three hours. Our LAMP method followed by a melting curve analysis presented that amplification by LAMP is specific for Fol and that the melting temperature of QProbe allows discrimination between race 3 and other races in about one hour. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that our method, and also PCR, may accidentally detect SIX3 homologous gene in another f. sp. Indeed, a SIX3 homologous gene has been identified from f. sp. cepae isolated from onion30. Although this SIX3 homologous gene had a high degree of sequence homology with SIX3 of Fol, there were a few different nucleotides in regions where our joint DNAs can anneal; the SIX3 sequence of f. sp. cepae contains three nucleotide residues different from that of Fol at nts. 121, 138 and 139 (G, C and A in Fol and C, G and C in f. sp. cepae). It is therefore highly likely that we can differentiate f. sp. cepae from Fol by our melting curve analysis, which will yield lower melting temperature with gDNA of f. sp. cepae than Fol.

Furthermore, the LAMP method developed in this study is more efficient and versatile to detect several types of point mutations than conventional LAMP. Conventional LAMP with the special inner primers, 5′- or 3′-end of which corresponds to a point mutation site, is able to specifically amplify target nucleotide sequences containing the mutation19–25. However, in this method, one needs to design each specific inner primer for different types of nucleotide substitutions. Moreover, this method based on a specific inner primer cannot be combined with loop primers, which accelerate LAMP reaction, due to the unspecific amplification of target genes22, 24, 25. By contrast, the method presented in this study exploits loop primers and two joint DNAs, instead of primers specific to each mutation, which can detect five types of point mutations with higher sensitivity. However, it should be also noted that, when we used DNA of Fol race 3 (SIX3 mutation type: C146T) for LAMP reaction with Joint DNA 2, we observed small peak at about 40 °C. Our Qprobe-mediated melting curve analysis is preceded by DNA amplification with conventional LAMP, which used the same primer set regardless of the Joint DNA used for the melting curve analysis. Because a single peak of a derivative of fluorescence was observed when using DNA of Fol race 3 (C146T) and Joint DNA 1, it is certain that the primer set used for LAMP works and amplification of DNA is successful. This will also be the case with analysis using Joint DNA 2. Considering that a peak height of the derivative depends on amount of joint DNA combined with amplification product, we estimate that, although amplification step is successful, Joint DNA 2 is not easy to bind to the amplification products containing C146T mutation. In principle, our method can detect single point mutations introduced in a partial SIX3 sequence covered by two joint DNAs (nucleotide positions 118 to 149). In addition, our method probably allows simultaneous detection of genomic DNAs of Fol race 3 isolates and those of Fol isolates of other races in a single tube based on difference in melting temperature; two peaks corresponding to race 3 and other races will be observed. Indeed, melting curve analysis with QProbe has been applied for homozygous or heterozygous SNP genotyping28. Accordingly, LAMP method with the universal QProbe can replace conventional PCR method to detect Fol race 3.

Fol race 3 isolates have been reported to have various types of mutations in their SIX3 gene. Besides the five types of single point mutation subjected in this study, two new mutation types of SIX3 have been recently found in Fol race 3 isolates from Australia31. One is deletion of a threonine residue at 50 of SIX3. Our method is likely to detect this mutation because an amino acid residue at 50 (nucleotide positions 148 to 150) is included in a region covered by joint DNA 2 (nucleotide positions 127 to 149). Another mutation is a complete loss of SIX3 31. This may not be detected by our method, but combination of SIX3 primers and other LAMP primer sets would enable us to detect this mutation. One of the most promising candidates of these primer sets is a combination of SIX5 and SIX1. SIX5 has been discovered only from Fol and f. sp. cepae while SIX1 from other f. sp. except f. sp. cepae 30, 32. Although these genes are useful to discriminate Fol from other ff. spp., we should repeatedly verify the usefulness of our SIX3-based system and modify it to cover as many race 3 isolates as possible because SIX3 mutation plays a key role in the occurrence of race 3 in Fol.

Now that we have developed discrimination method of Fol race 3 isolates from those of other races, all races of Fol isolates can be identified by LAMP. Our present method is unable to distinguish race 1 and race 2, but we have previously developed conventional LAMP to discriminate Fol race 1 from other races by detection of SIX4, which is unique to Fol race 118. Combination of both our LAMP methods can identify almost all Fol races. However, it should be noted that Fol race 2 isolate Chiba-5 harboring transposon-inserted SIX4 is indistinguishable by our LAMP methods15. We have discriminated transposon-inserted SIX4 of Fol race 3 isolate KoChi-1 from SIX4 of Fol race 1 using LAMP primers targeting the transposon-insertion site18. However, the transposon-insertion site of Chiba-5 is different from that of KoChi-115. Chiba-5 could be also distinguished from Fol race 1 by designing a new set of LAMP primers that binds to the transposon-insertion site in SIX4 of Chiba-5.

Our LAMP assay is applicable for diagnosis of tomato wilt using crude DNA from soil. The LAMP with the universal QProbe enabled us to detect Fol race 3 from Soil DNA1 and 2 with a history of tomato wilt but not from rhizosphere soils of healthy tomato plants. In contrast, PCR with SIX3 primers showed no amplification from all soil DNAs tested including DNA1 and 2, which demonstrated superiority of our method. As point mutations in an avirulence gene change races of the plant pathogen, those in a gene targeted by fungicides confer resistance to the drug in several fungal species33, 34. LAMP with the universal QProbe presented in this study could lead to the development of novel SNP discrimination methods for understanding plant pathogens in the field.

Materials and Methods

Fungal strains and culture conditions

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici (Fol) and other fungal species used in this study are listed in Table 1. These isolates were grown on potato sucrose agar (PSA) medium at 25 °C under dark conditions. For DNA isolation and preparation of Fol-infested soil, all isolates were grown on potato sucrose broth (PSB) at room temperature with shaking at 120 spm.

Sampling soil from field

Soils infested with Fol race 3 were sampled from two fields (latitude, N33°31′92″; longitude, E133°21′97.1″; altitude 19 m and latitude, N33°31′50.28″; longitude, E133°22.01′66″; altitude 22 m) in Hidaka, Kochi in May in 2012 or 2013. Rhizosphere soils of healthy tomato plants were sampled from the same fields in January in 2013 or 2014. Fol race 2 resistant cultivar Momotaro Fight (Takii Seed, Kyoto, Japan) had been grown in the fields since 2011. All soils were stored at 4 °C before DNA isolation.

Preparation of artificial infested soil by Fol

To prepare soil artificially infested with Fol, soil (10 g) (Nippi engei baido No. 1, Nihon Hiryo, Tokyo, Japan) autoclaved for 20 min twice with the interval of 1 h were inoculated with 1 ml of Fol bud cell (microconidia) suspension (107 cells/ml) in 50 ml tubes. The tubes were vortexed vigorously and the soil were air-dried in a petri dish at room temperature overnight.

DNA isolation

DNA isolation from fungal mycelium was performed as described before35. Briefly, fungal mycelia were ground in liquid nitrogen and mixed with 5 ml of DNA extraction buffer (0.7 M NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% [w/v] SDS, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5). After vortexing for 2 min, 2 ml of PCI (phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol, 25:24:1, v/v) was added and mixed by inverting the tube for 2 min. After centrifuging at 2,470 × g for 10 min, supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of PCI and re-centrifuged. Supernatant were mixed with an equal volume of chloroform and followed by centrifugation 2,470 × g, and then DNAs in the supernatant were precipitated in 99.5% ethanol with 0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.0), and centrifuged at 2,470 g to harvest the DNAs. DNA pellet was washed by 1 ml of 70% ethanol. DNA was dissolved with distilled water and stored at −30 °C before use. DNA concentration was determined by Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

For DNA isolation from soil, Fast-DNA® Spin kit for soil (Bio101, Vista, CA, USA) with skim milk was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the methods described in the previous report36, 37.

Design of a LAMP primer set and joint DNAs

A primer set for LAMP reaction were designed based on the SIX3 (GenBank accession number: AM234063.1) gene sequence of Fol using the PrimerExplorer V4 software (http://primerexplorer.jp). The primer set comprised two outer primers (SIX3-F3 and SIX3-B3), two inner primers (SIX3-FIP and SIX3-BIP), and two loop primers (LF and LB). Nucleotide sequence of all primers were presented in Table 1. Two joint DNAs, Joint DNA 1 and Joint DNA 2, whose 3′-end binds to UQprobe-G, were designed for binding to two partial regions of SIX3 sequences, nts. 113–129 or 127–149, respectively, with respect to the first nucleotide of its translation initiation codon. Positions of all primers were shown in Fig. 1. All primers and joint DNA were synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich (Tokyo, Japan). Nucleotide sequences of UQprobe-G is protected by Patent No. US7427672 B2, EP1661905 A1 and JP4731324.

LAMP assay

LAMP reaction with the universal QProbe system was carried out with the previously described methods with slight modifications38. Briefly, the LAMP reaction mixture (25 µl) contained 1.4 mM each dNTP, 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.8), 10 mM KCl, 8 mM MgSO4, 10 mM (NH4) 2SO4, 0.1% Tween 20, and 0.8 M betaine, 0.2 µM each of F3 and B3 primers, 1.6 µM each of FIP and BIP primers, 0.8 µM each of Loop F and Loop B primers, 0.14 µM of UQprobe-G (J-Bio21, Tokyo, Japan), 0.4 µM of Joint DNA 1 or 2, Bst DNA polymerase (8 U) (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) and DNA (30 ng) as a template. LAMP reaction at 66 °C, as well as a subsequent melting curve analysis from 30 or 35 °C to 95 °C with a decrement of 0.2 °C per second, were performed by Genie II (OptiGene, Horsham, UK). Conventional LAMP reactions with SIX4 primer set were conducted as described in a previously report18, with the Fluorescent detection reagent (Eiken Kagaku, Tokyo, Japan) as a fluorescent dye instead of UQprobe-G. Conventional LAMP reaction with SIX3 primer set mixture, which contains above-mentioned except UQprobe-G and joint DNAs was incubated at 59–66 °C for 60 min followed by 10 min of incubation at 98 °C with Genie II (OptiGene) to detect and monitor fluorescence.

PCR reaction

PCR reaction was performed in a reaction volume (10 µl) containing 1.25 units of Ex Taq polymerase (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan), 0.5 µM each primer, 1 × Ex Taq buffer, 0.2 mM each dNTP and fungal genomic DNA (30 ng) using TaKaRa PCR Thermal Cycler Dice (TaKaRa). PCR conditions with SIX3 LAMP outer primers was as follows: initial denature at 94 °C for 2 min, 30 cycle of denaturation at 98 °C for 30 s, annealing at 59 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 6 min. PCR with the SIX4 primer set was conducted as described in the previous report11. PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV irradiation.

Plasmid construct

To generate SIX3 gene containing a single point mutation (G137C), two PCR fragments harboring the mutation were amplified by using Fol race 1 gDNA (30 ng) and primers SIX3 F, SIX3 R, G137CF and G137CR, which were designed for introducing the mutation in the PCR product (Table 1). PCR condition was: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 60.7 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were purified by Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The purified PCR products (3 ng) were ligated by recombinant PCR39. Constitution of PCR mixture was the same as above. The PCR conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, annealing at 98 °C for 10 s and extension at 63 °C for 30 s and final extension at 72 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 7 min. PCR product was cloned into pGEM-T easy vector (Promega), which was subsequently transformed into Escherichia coli Hit DH5α (RBC Bioscience, Taipei, Taiwan). Resultant transformants were selected by colony PCR with SIX3 F and SIX3 R primers followed by plasmid DNA extraction from the isolates with Wizard Plus SV PureYield Minipreps DNA Pulification System (Promega). Sequencing to confirm the mutation was performed with BigDye terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing system kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as followed by previous report40 and 3130 × 1 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We appreciate technical advice provided by Nippon Gene. We thank J-Bio21 for designing joint DNAs. We are grateful to tomato farmers in Kochi prefectures for providing field soil and to Ryo Ishikawa (Sumika green) for providing AS2. This study was partly supported by Grants-in-Aid from The Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences (JSPS) for TA (18380030, 26304025, 16H02536).

Author Contributions

Y.A. designed experiments with the help of K.K. and T.A.; Y.A. and S.H. performed experiments; Y.A., S.H., N.F., K.K. and T.A. analyzed data; and Y.A. and K.K. wrote the paper; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-04084-y

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Takken FLW, Rep M. The arms race between tomato and Fusarium oxysporum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2010;11:309–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grattidge R, O’Brien R. G Occurrence of a third race of Fusarium wilt of tomatoes in Queensland. Plant Dis. 1982;66:165. doi: 10.1094/PD-66-165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volin RB, Jones JP. A New race of Fusarium wilt of tomato in Florida and sources of resistance. Proc. Fla. State. Hort. Soc. 1982;95:267–270. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chellemi DO, Dankers HA. First report of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 3 on tomato in Northwest Florida and Georgia. Plant Dis. 1992;76:861. doi: 10.1094/PD-76-0861D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marlatt ML, Correll JC, Kaufmann P, Cooper PE. Two genetically distinct populations of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 3 in the United States. Plant Dis. 1996;80:1336–1342. doi: 10.1094/PD-80-1336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valenzuela-Ureta JG. First report of Fusarium wilt race 3, caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici, of tomato in Mexico. Plant Dis. 1996;80:105. doi: 10.1094/PD-80-0105A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reis A, Costa H, Boiteux LS, Lopes CA. First report of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 3 on tomato in Brazil. Fitopatol. bras. 2005;30:426–428. doi: 10.1590/S0100-41582005000400017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reis A, Boiteux LS. Outbreak of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 3 in commercial fresh-market tomato fields in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Hortic. Bras. 2007;25:451–454. doi: 10.1590/S0102-05362007000300025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masunaga T, Shiomi H, Komada H. Identification of race 3 of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici isolated from tomato in Fukuoka prefecture. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 1998;64:435. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwaya K, Yamashita K, Iwaya T. Occurrence of Fusarium wilt of tomato caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 3 in Aomori prefecture. Annu. Rep. Piant Prot. North Japan. 2008;59:68–70. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inami K, et al. A genetic mechanism for emergence of races in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici: Inactivation of avirulence gene AVR1 by transposon insertion. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rep M, et al. A small, cysteine-rich protein secreted by Fusarium oxysporum during colonization of xylem vessels is required for I-3-mediated resistance in tomato. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;53:1373–1383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houterman PM, Cornelissen BJC, Rep M. Suppression of plant resistance gene-based immunity by a fungal effector. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000061. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houterman PM, et al. The effector protein Avr2 of the xylem-colonizing fungus Fusarium oxysporum activates the tomato resistance protein I-2 intracellularly. Plant J. 2009;58:970–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kashiwa, T. et al. A new biotype of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 2 emerged by a transposon-driven mutation of avirulence gene AVR1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 363, fnw132 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Lievens B, Houterman PM, Rep M. Effector gene screening allows unambiguous identification of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici races and discriminationfrom other formae speciales. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009;300:201–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inami K, et al. Real-time PCR for differential determination of the tomato wilt fungus, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici, and its races. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2010;76:116–121. doi: 10.1007/s10327-010-0224-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayukawa Y, et al. Detection and differentiation of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 1 using loop-mediated isothermal amplification with three primer sets. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2016;63:202–209. doi: 10.1111/lam.12597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang C, et al. Establishment and application of a real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification system for the detection of CYP2C19 polymorphisms. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26533. doi: 10.1038/srep26533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikeda S, Takabe K, Inagaki M, Funakoshi N, Suzuki K. Detection of gene point mutation in paraffin sections using in situ loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Pathol. Int. 2007;57:594–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badolo A, et al. Development of an allele-specific, loop-mediated, isothermal amplification method (AS-LAMP) to detect the L1014F kdr-w mutation in Anopheles gambiae s. l. Malar. J. 2012;11:227. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan Y, et al. Development and application of loop-mediated isothermal amplification for detection of the F167Y mutation of carbendazim-resistant isolates in Fusarium graminearum. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:7094. doi: 10.1038/srep07094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Badolo A, et al. Detection of G119S ace-1R mutation in field-collected Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes using allele-specific loop-mediated isothermal amplification (AS-LAMP) method. Malar. J. 2015;14:477. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0968-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duan, Y. et al. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for the rapid detection of the F200Y mutant genotype of carbendazim-resistant isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Dis. 100 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Duan Y, et al. Development of a rapid and high-throughput molecular method for detecting the F200Y mutant genotype in benzimidazole-resistant isolates of Fusarium asiaticum. Pest Manag. Sci. 2016;72:2128–2135. doi: 10.1002/ps.4243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crockett AO, Wittwer CT. Fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotides for real-time PCR: using the inherent quenching of deoxyguanosine nucleotides. Anal. Biochem. 2001;290:89–97. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurata S, et al. Fluorescent quenching-based quantitative detection of specific DNA/RNA using a BODIPY FL-labeled probe or primer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e34. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.6.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tani H, et al. Universal Quenching Probe System: Universal quenching probe system: flexible, specific, and cost-effective real-time polymerase chain reaction method. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:5678–5685. doi: 10.1021/ac900414u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirano Y, Arie T. PCR-based differentiation of Fusarium oxysporum ff. sp. lycopersici and radicis-lycopersici and races of F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2006;72:273–283. doi: 10.1007/s10327-006-0287-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sasaki K, Nakahara K, Tanaka S, Shigyo M, Ito S. Genetic and pathogenic variability of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cepae isolated from onion and Welsh onion in Japan. Phytopathology. 2015;105:525–32. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-14-0164-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chellappan, B. V, Fokkens, L., Houterman, P. M., Rep, M. & Cornelissen, B. J. C. Multiple evolutionary trajectories have led to the emergence of races in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. AEM. 02548–16, doi:10.1128/AEM.02548-16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Thatcher LF, Gardiner DM, Kazan K, Manners JM. A highly conserved effector in Fusarium oxysporum is required for full virulence on Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant. Microbe. Interact. 2012;25:180–90. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-08-11-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma Z, Michailides TJ. Advances in understanding molecular mechanisms of fungicide resistance and molecular detection of resistant genotypes in phytopathogenic fungi. Crop Prot. 2005;24:853–863. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2005.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joosten MHAJ, Cozijnsen TJ, De Wit PJGM. Host resistance to a fungal tomato pathogen lost by a single base-pair change in avirulence gene. Nature. 1994;367:384–386. doi: 10.1038/367384a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kashiwa T, et al. An avirulence gene homologue in the tomato wilt fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 1 functions as a virulence gene in the cabbage yellows fungus F. oxysporum f. sp. conglutinans. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2013;79:412–421. doi: 10.1007/s10327-013-0471-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takada-Hoshino Y, Matsumoto N. An improved DNA extraction method using skim milk from soils that strongly adsorb DNA. Microbes Environ. 2004;19:13–19. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.19.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morimoto S, Hoshino YT. Methods for analysis of soil communities by PCR-DGGE (1): Bacterial and fungal communities (Methods) Soil Microorg. 2008;62:63–68. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujita N, et al. Rapid sex identification method of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) in the vegetative stage using loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Planta. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00425-016-2618-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heckman KL, Pease LR. Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:924–932. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Platt AR, Woodhall RW, George AL. Improved DNA sequencing quality and efficiency using an optimized fast cycle sequencing protocol. Biotechniques. 2007;43:58–62. doi: 10.2144/000112499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.