Abstract

Background

External segmentation and internal proglottization are important evolutionary characters of the Eucestoda. The monozoic caryophyllideans are considered the earliest diverging eucestodes based on partial mitochondrial genes and nuclear rDNA sequences, yet, there are currently no complete mitogenomes available. We have therefore sequenced the complete mitogenomes of three caryophyllideans, as well as the polyzoic Schyzocotyle acheilognathi, explored the phylogenetic relationships of eucestodes and compared the gene arrangements between unsegmented and segmented cestodes.

Results

The circular mitogenome of Atractolytocestus huronensis was 15,130 bp, the longest sequence of all the available cestodes, 14,620 bp for Khawia sinensis, 14,011 bp for Breviscolex orientalis and 14,046 bp for Schyzocotyle acheilognathi. The A-T content of the three caryophyllideans was found to be lower than any other published mitogenome. Highly repetitive regions were detected among the non-coding regions (NCRs) of the four cestode species. The evolutionary relationship determined between the five orders (Caryophyllidea, Diphyllobothriidea, Bothriocephalidea, Proteocephalidea and Cyclophyllidea) is consistent with that expected from morphology and the large fragments of mtDNA when reconstructed using all 36 genes. Examination of the 54 mitogenomes from these five orders, revealed a unique arrangement for each order except for the Cyclophyllidea which had two types that were identical to that of the Diphyllobothriidea and the Proteocephalidea. When comparing gene order between the unsegmented and segmented cestodes, the segmented cestodes were found to have the lower similarities due to a long distance transposition event. All rearrangement events between the four arrangement categories took place at the junction of rrnS-tRNA Arg (P1) where NCRs are common.

Conclusions

Highly repetitive regions are detected among NCRs of the four cestode species. A long distance transposition event is inferred between the unsegmented and segmented cestodes. Gene arrangements of Taeniidae and the rest of the families in the Cyclophyllidea are found be identical to those of the sister order Proteocephalidea and the relatively basal order Diphyllobothriidea, respectively.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2245-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Mitogenome, Caryophyllidean tapeworm, Parasitic Platyhelminthes, Proglottization, Segmentation

Background

Scolex type, external segmentation and internal proglottization are all important evolutionary characters of the Cestoda. The Amphilinidea and Gyrocotylidea (Cestodaria) that do not possess a scolex are early divergent lineages in this class. Tapeworms of the order Caryophyllidea (Platyhelminthes: Eucestoda) are typified by a monozoic body (neither internal proglottization nor external segmentation). The Spathebothriidea are polyzoic but externally unsegmented, and all other eucestodes demonstrate classic proglottization (segmented body parts each with a set of reproductive organs). Morphological analysis shows the Caryophyllidea to be the earliest divergent lineage of Eucestoda [1] although phylogenetic analysis based on LSU rDNA and SSU rDNA have indicated that the Spathebothriidea may be the earliest diverging eucestodes [2, 3]. However, recently, topology constructed using large fragments of mtDNA supports the Caryophyllidea as the most primitive eucestodes [4]. These results indicate the Caryophyllidea to be a key group for studying evolutionary relationships within the Eucestoda as well as with other parasitic Monogenea, Aspidogastrea and Digenea.

Owing to its maternal inheritance, a lack of recombination and a fast rate of evolution [5], the haploid mitochondrial genome has proven to be a useful marker for population studies, species identification and phylogenetics [6, 7]. Its genome-level characteristics, gene arrangements and the positions of mobile genetic elements also enable it to be a powerful tool for reconstructing evolutionary relationships [8–10]. Using gene sequences and gene arrangements from the complete mt genome, the phylogenies of some parasitic Platyhelminthes have been reconstructed [11–13]. However, due to a paucity of complete mt genomic information from these groups, very few parasitic flatworms have been included in these phylogenetic analyses. From the 16 orders of cestodes that exist, only four (Diphyllobothriidea, Bothriocephalidea, Proteocephalidea and Cyclophyllidea) are currently represented in the GenBank database, and as the ancestral taxa of the Eucestoda, no complete mitogenome from the Caryophyllidea has been sequenced.

Khawia sinensis Hsü, 1935, and Atractolytocestus huronensis Anthony, 1958, belong to the family Lytocestidae and are very common caryophyllideans in the intestine of the common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Both invasive tapeworms have a worldwide distribution and are translocated with the introduction of the common carp into countries around the world [14, 15]. Breviscolex orientalis Kulakovskaya, 1962, the only member of the family Capingentidae, is typically recorded in the cyprinids Hemibarbus barbus [16]. In addition, the Asian fish tapeworm Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (syn. Bothriocephalus acheilognathi), a segmented tapeworm of the Bothriocephallidea, is also an invasive parasite found worldwide.

This study has therefore generated the complete mitogenomes of three caryophyllideans, in addition to the Asian fish tapeworm in order to analyse the phylogenetic relationships of eucestodes and the differences in the gene arrangement between unsegmented and segmented eucestodes.

Methods

Specimen collection and DNA extraction

The following cestodes, K. sinensis and A. huronensis from the common carp (Cyprinus carpio), B. orientalis from Hemibarbus maculates and S. acheilognathi from the grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), were collected from a fishery (29°59′10.47″N, 115°47′37″E) in Hubei Province, China. The parasites were preserved in 80% ethanol and stored at 4 °C. Specimens were stained with carmine and identified morphologically using the scolex and testis [16]. Total genomic DNA was extracted from the posterior region of a single tapeworm using a TIANamp Micro DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was stored at -20 °C for subsequent molecular analysis. The morphological identification of specimens was verified by sequence analysis of the complete ITS1 rDNA region [17] and partial sequence of cox1 gene [18].

PCR and DNA sequencing

Partial sequences of the mtDNA from the four cestodes were initially amplified by PCR using degenerate primers (Additional file 1: Table S1). Using these fragments, specific primers were designed for subsequent PCR amplification (Additional file 1: Table S1). PCR reactions were conducted in a 20 μl reaction mixture, containing 7.4 μl molecular grade water, 10 μl 2 × PCR buffer (Mg2+, dNTP plus, Takara, Dalian, China), 0.6 μl of each primer, 0.4 μl rTaq polymerase (250 U/μl, Takara), and 1 μl DNA template. Amplification was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles at 98 °C for 10 s, 48–60 °C for 15 s, 68 °C for 1 min/kb, and a final extension at 68 °C for 10 min. PCR products were sequenced bidirectionally at Sangon Company (Shanghai, China) using the primer walking strategy.

Sequence analyses

The complete mt sequences were assembled manually and aligned against the mitogenome sequences of other published cestodes using the program MAFFT 7.149 [19] to determine the gene boundaries. Protein-coding genes (PCGs) were inferred with the help of BLASTX [20] and SeqBuilder module in the Lasergene7 software package (DNASTAR), employing the genetic code 9, the echinoderm and flatworm mitochondrial. The majority of tRNAs were identified by comparing the results of tRNAscan-SE [21], ARWEN [22], MITOs [23] and DOGMA [24]. However, tRNA Phe and tRNA Gln from B. orientalis and tRNA Gln from A. huronensis were visually compared with the sequences from other cestodes. The location of the two ribosomal RNA genes, rrnL and rrnS, were explored through alignment with other available mt cestodes sequences, and their ends were assumed to extend to the boundaries of their flanking genes. The 5′ end of the rrnL gene in S. acheilognathi however, was determined by the result of alignments. MitoTool [25], a home-made program, was primarily used to parse the annotated mt genome into a Word document format, and generate *.sqn file for GenBank submission and a *.csv file for Table 1. Mitotool was furthermore employed to unify the name of all 36 genes (12 PCGs, 2 rRNAs and 22 tRNAs) and locate all NCR positions (setting threshold of 50 bp) within the mitogenomes of the selected cestodes. Finally, the fasta file containing the nucleotide sequences and gene order for all 36 genes (12 PCGs, 2 rRNAs and 22 tRNAs) was extracted from the GenBank files, processed and used to generate Additional file 2: Table S2 and Additional file 3: Table S3. Repetitive regions within the NCRs were found using a local version of a Tandem Repeats Finder [26]. The alignments located in highly repetitive regions (HRRs) were shaded and labelled using TEXshade software [27]. The secondary structure of each consensus repeat unit was predicted by Mfold software [28], and codon usage and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) were computed with MEGA 5 [29]. CREx program [30] was then utilised to calculate the rearrangement events and to conduct pairwise comparisons of gene orders from all of the cestodes using common intervals measurement.

Table 1.

The annotated mitochondrial genome of the four cestodes

| Gene | Position | Size | Intergenic nucleotides | Codon | Anti-codon | Gene | Position | Size | Intergenic nucleotides | Codon | Anti-codon | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | Start | Stop | From | To | Start | Stop | ||||||||

| (A) Atractolytocestus huronensis | (B) Breviscolex orientalis | ||||||||||||||

| cox3 | 1 | 643 | 643 | ATG | T | 1 | 643 | 643 | ATG | T | |||||

| tRNA-His(H) | 644 | 705 | 62 | GTG | 644 | 707 | 64 | GTG | |||||||

| cytb | 707 | 1792 | 1086 | 1 | ATG | TAA | 708 | 1793 | 1086 | ATG | TAA | ||||

| nad4L | 1792 | 2052 | 261 | -1 | ATG | TAG | 1793 | 2053 | 261 | -1 | ATG | TAA | |||

| nad4 | 2013 | 3245 | 1233 | -40 | ATG | TAG | 2014 | 3246 | 1233 | -40 | ATG | TAG | |||

| tRNA-Gln(Q) | 3247 | 3307 | 61 | 1 | TTG | 3247 | 3313 | 67 | TTG | ||||||

| tRNA-Phe(F) | 3304 | 3367 | 64 | -4 | GAA | 3306 | 3369 | 64 | -8 | GAA | |||||

| tRNA-Met(M) | 3364 | 3425 | 62 | -4 | CAT | 3364 | 3424 | 61 | -6 | CAT | |||||

| atp6 | 3427 | 3942 | 516 | 1 | ATG | TAA | 3427 | 3942 | 516 | 2 | ATG | TAG | |||

| nad2 | 3943 | 4818 | 876 | GTG | TAG | 3942 | 4814 | 873 | -1 | GTG | TAG | ||||

| tRNA-Val (V) | 4819 | 4879 | 61 | TAC | 4817 | 4876 | 60 | 2 | TAC | ||||||

| tRNA-Ala (A) | 4878 | 4938 | 61 | -2 | TGC | 4875 | 4936 | 62 | -2 | TGC | |||||

| tRNA-Asp(D) | 4942 | 5002 | 61 | 3 | GTC | 4940 | 5002 | 63 | 3 | GTC | |||||

| nad1 | 5003 | 5896 | 894 | ATG | TAG | 5005 | 5898 | 894 | 2 | ATG | TAG | ||||

| tRNA-Asn(N) | 5896 | 5959 | 64 | -1 | GTT | 5898 | 5960 | 63 | -1 | GTT | |||||

| tRNA-Pro(P) | 5962 | 6021 | 60 | 2 | TGG | 5963 | 6024 | 62 | 2 | TGG | |||||

| tRNA-Ile(I) | 6021 | 6084 | 64 | -1 | GAT | 6024 | 6087 | 64 | -1 | GAT | |||||

| tRNA-Lys(K) | 6085 | 6143 | 59 | CTT | 6088 | 6147 | 60 | CTT | |||||||

| nad3 | 6144 | 6491 | 348 | GTG | TAG | 6148 | 6498 | 351 | GTG | TAG | |||||

| tRNA-Ser(S1) | 6489 | 6545 | 57 | -3 | GCT | 6497 | 6552 | 56 | -2 | GCT | |||||

| tRNA-Trp(W) | 6547 | 6608 | 62 | 1 | TCA | 6555 | 6618 | 64 | 2 | TCA | |||||

| cox1 | 6613 | 8166 | 1554 | 4 | ATG | TAG | 6625 | 8166 | 1542 | 6 | ATG | TAG | |||

| tRNA-Thr(T) | 8157 | 8217 | 61 | -10 | TGT | 8157 | 8219 | 63 | -10 | TGT | |||||

| 16S | 8218 | 9171 | 954 | 8220 | 9166 | 947 | |||||||||

| tRNA-Cys(C) | 9172 | 9230 | 59 | GCA | 9167 | 9230 | 64 | GCA | |||||||

| 12S | 9231 | 9931 | 701 | 9231 | 9937 | 707 | |||||||||

| tRNA-Leu(L1) | 9932 | 9995 | 64 | TAG | 9938 | 10,002 | 65 | TAG | |||||||

| tRNA-Ser(S2) | 9998 | 10,059 | 62 | 2 | TGA | 10,009 | 10,072 | 64 | 6 | TGA | |||||

| tRNA-Leu(L2) | 10,060 | 10,123 | 64 | TAA | 10,075 | 10,136 | 62 | 2 | TAA | ||||||

| NCR1 | 10,124 | 10,996 | 873 | 10,137 | 10,344 | 208 | |||||||||

| cox2 | 10,997 | 11,569 | 573 | GTG | TAA | 10,345 | 10,920 | 576 | ATG | TAG | |||||

| tRNA-Glu(E) | 11,570 | 11,640 | 71 | TTC | 10,921 | 10,987 | 67 | TTC | |||||||

| nad6 | 11,641 | 12,099 | 459 | GTG | TAG | 10,988 | 11,446 | 459 | GTG | TAG | |||||

| tRNA-Tyr(Y) | 12,106 | 12,171 | 66 | 6 | GTA | 11,454 | 11,517 | 64 | 7 | GTA | |||||

| tRNA-Arg(R) | 12,173 | 12,226 | 54 | 1 | TCG | 11,519 | 11,574 | 56 | 1 | TCG | |||||

| nad5 | 12,227 | 13,783 | 1557 | GTG | TAG | 11,577 | 13,124 | 1548 | 2 | GTG | TAA | ||||

| tRNA-Gly(G) | 13,784 | 13,847 | 64 | TCC | 13,124 | 13,186 | 63 | -1 | TCC | ||||||

| NCR2 | 13,848 | 15,130 | 1283 | 13,187 | 14,011 | 825 | |||||||||

| (C) Khawia sinensis | (D) Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (CN) | ||||||||||||||

| cox3 | 1 | 637 | 637 | ATG | T | 1 | 655 | 655 | ATG | T | |||||

| tRNA-His(H) | 638 | 699 | 62 | GTG | 656 | 730 | 75 | GTG | |||||||

| cytb | 701 | 1822 | 1122 | 1 | ATG | TAA | 734 | 1831 | 1098 | 3 | ATG | TAG | |||

| nad4L | 1804 | 2064 | 261 | -19 | ATG | TAG | 1833 | 2093 | 261 | 1 | GTG | TAG | |||

| nad4 | 2025 | 3257 | 1233 | -40 | ATG | TAA | 2054 | 3304 | 1251 | -40 | GTG | TAG | |||

| tRNA-Gln(Q) | 3258 | 3318 | 61 | TTG | 3304 | 3367 | 64 | -1 | TTG | ||||||

| tRNA-Phe(F) | 3315 | 3378 | 64 | -4 | GAA | 3363 | 3426 | 64 | -5 | GAA | |||||

| tRNA-Met(M) | 3374 | 3436 | 63 | -5 | CAT | 3423 | 3486 | 64 | -4 | CAT | |||||

| atp6 | 3440 | 3955 | 516 | 3 | ATG | TAA | 3490 | 4005 | 516 | 3 | ATG | TAG | |||

| nad2 | 3960 | 4832 | 873 | 4 | ATG | TAG | 4006 | 4878 | 873 | ATG | TAG | ||||

| tRNA-Val (V) | 4835 | 4894 | 60 | 2 | TAC | 4883 | 4948 | 66 | 4 | TAC | |||||

| tRNA-Ala (A) | 4893 | 4954 | 62 | -2 | TGC | 4958 | 5019 | 62 | 9 | TGC | |||||

| tRNA-Asp(D) | 4960 | 5024 | 65 | 5 | GTC | 5025 | 5087 | 63 | 5 | GTC | |||||

| nad1 | 5025 | 5918 | 894 | ATG | TAG | 5092 | 5985 | 894 | 4 | ATG | TAA | ||||

| tRNA-Asn(N) | 5918 | 5984 | 67 | -1 | GTT | 5991 | 6055 | 65 | 5 | GTT | |||||

| tRNA-Pro(P) | 5988 | 6047 | 60 | 3 | TGG | 6060 | 6122 | 63 | 4 | TGG | |||||

| tRNA-Ile(I) | 6047 | 6110 | 64 | -1 | GAT | 6128 | 6193 | 66 | 5 | GAT | |||||

| tRNA-Lys(K) | 6117 | 6177 | 61 | 6 | CTT | 6198 | 6259 | 62 | 4 | CTT | |||||

| nad3 | 6178 | 6523 | 346 | ATG | T | 6264 | 6608 | 345 | 4 | ATG | TAA | ||||

| tRNA-Ser(S1) | 6524 | 6578 | 55 | TCT | 6607 | 6665 | 59 | -2 | GCT | ||||||

| tRNA-Trp(W) | 6579 | 6641 | 63 | TCA | 6666 | 6729 | 64 | TCA | |||||||

| cox1 | 6646 | 8196 | 1551 | 4 | ATG | TAG | 6742 | 8328 | 1587 | 12 | ATG | TAG | |||

| tRNA-Thr(T) | 8187 | 8247 | 61 | -10 | TGT | 8342 | 8404 | 63 | 13 | TGT | |||||

| NCR1 | 8405 | 8528 | 124 | ||||||||||||

| 16S | 8248 | 9193 | 946 | 8529 | 9494 | 966 | |||||||||

| tRNA-Cys(C) | 9194 | 9251 | 58 | GCA | 9495 | 9555 | 61 | GCA | |||||||

| 12S | 9252 | 9960 | 709 | 9556 | 10,285 | 730 | |||||||||

| tRNA-Leu(L1) | 9961 | 10,023 | 63 | TAG | cox2 | 10,286 | 10,858 | 573 | ATG | TAA | |||||

| tRNA-Ser(S2) | 10,025 | 10,087 | 63 | 1 | TGA | E | 10,862 | 10,924 | 63 | 3 | TTC | ||||

| tRNA-Leu(L2) | 10,089 | 10,150 | 62 | 1 | TAA | nad6 | 10,928 | 11,383 | 456 | 3 | ATG | TAA | |||

| NCR1 | 10,151 | 10,699 | 549 | L1 | 11,402 | 11,465 | 64 | 18 | TAG | ||||||

| cox2 | 10,700 | 11,273 | 574 | ATG | T | L2 | 11,468 | 11,531 | 64 | 2 | TAA | ||||

| tRNA-Glu(E) | 11,272 | 11,332 | 61 | -2 | TTC | Y | 11,539 | 11,602 | 64 | 7 | GTA | ||||

| nad6 | 11,333 | 11,791 | 459 | ATG | TAA | S2 | 11,620 | 11,685 | 66 | 17 | TGA | ||||

| tRNA-Tyr(Y) | 11,797 | 11,859 | 63 | 5 | GTA | NCR2 | 11,686 | 11,851 | 166 | ||||||

| tRNA-Arg(R) | 11,872 | 11,925 | 54 | 12 | TCG | 11,852 | 11,909 | 58 | TCG | ||||||

| nad5 | 11,926 | 13,476 | 1551 | ATG | TAA | 11,913 | 13,478 | 1566 | 3 | ATG | TAA | ||||

| tRNA-Gly(G) | 13,476 | 13,537 | 62 | -1 | TCC | 13,484 | 13,547 | 64 | 5 | TCC | |||||

| NCR2 | 13,538 | 14,620 | 1083 | NCR3 | 13,548 | 14,046 | 499 | ||||||||

Phylogenetic analyses

Phylogenetic analysis was carried out using the mitogenomes generated from the four cestodes as part of this study as well as those of the 50 cestodes available from GenBank (Additional file 2: Table S2). Two trematodes, Dicrocoelium chinensis (NC_025279) and Dicrocoelium dendriticum (NC_025280), were used as outgroups. Another program written in-house, BioSuite [31], was employed to align all of the genes in batches using integrated MAFFT, wherein codon-alignment mode was used for the 12 PCGs, and normal alignment mode for the remaining genes (2 rRNAs and 22 tRNAs). The alignments were then concatenated to generate well-supported Phylip and nexus format files for use in the phylogenetic analysis software. Both the maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) were used to reconstruct phylogenetic trees, and selection of the most appropriate evolutionary models for the dataset was carried out using ModelGenerator v0.8527 [32]. Based on the Akaike information criterion, GTR + I + G was chosen as the optimal model for nucleotide evolution. ML analysis was performed by RaxML GUI [33] using an ML + rapid bootstrap algorithm with 1000 replicates. BI analysis was performed in MrBayes 3.2.1 [34] with default settings and 1 × 107 Metropolis-coupled MCMC generations. The tree was then annotated using iTOL (a web-based tool) [35] with the help of several dataset files generated by MitoTool.

Results

Genome organisation and base composition

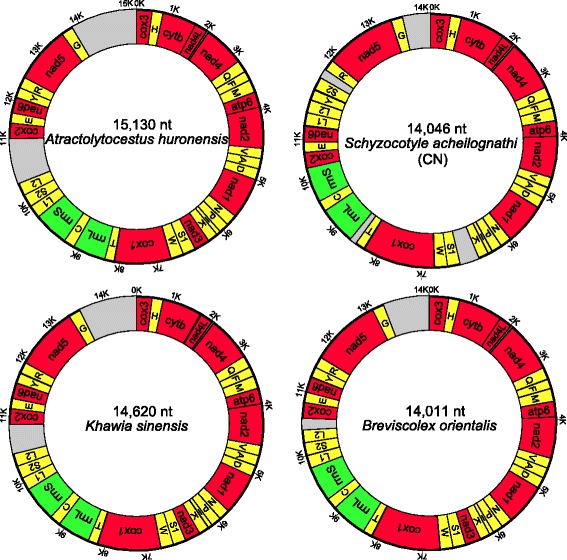

The mitogenomes of A. huronensis (GenBank accession number: KY486754), B. orientalis (KY486752), K. sinensis (KY486753) and S. acheilognathi (CN) (KX589243) are circular double-stranded DNA molecules. The size of these mitogenomes was 15,130 bp in A. huronensis, 14,620 bp in K. sinensis, 14,011 bp in B. orientalis, and 14,046 bp in S. acheilognathi (CN) (Fig. 1). The mitogenome of A. huronensis was the largest of all those available for cestodes (Additional file 2: Table S2, Fig. 2). The length of the S. acheilognathi (CN) mitogenome was about 140 bp longer than previously published due to the presence of a longer NCR between nad5 and cox3 [36]. Similar to other flatworm mitogenomes [11], which lacked the atp8 gene, and encoded all the genes on the same strand, all of those generated in this study contained the standard 36 elements: 12 PCGs (atp6, cytb, cox1–3, nad1–6 and nad4L), 22 tRNA genes and two rRNA genes (Fig. 1). Intriguingly, A-T content of the three Caryophyllidea species (K. sinensis, A. huronensis and B. orientalis) was the lowest of all published cestode mitogenomes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Map of the mitochondrial genomes of Atractolytocestus huronensis, Breviscolex orientalis, Khawia sinensis and Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (China, CN). The 12 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 22 tRNA and two rRNA genes are depicted as well as the non-coding regions (NCRs)

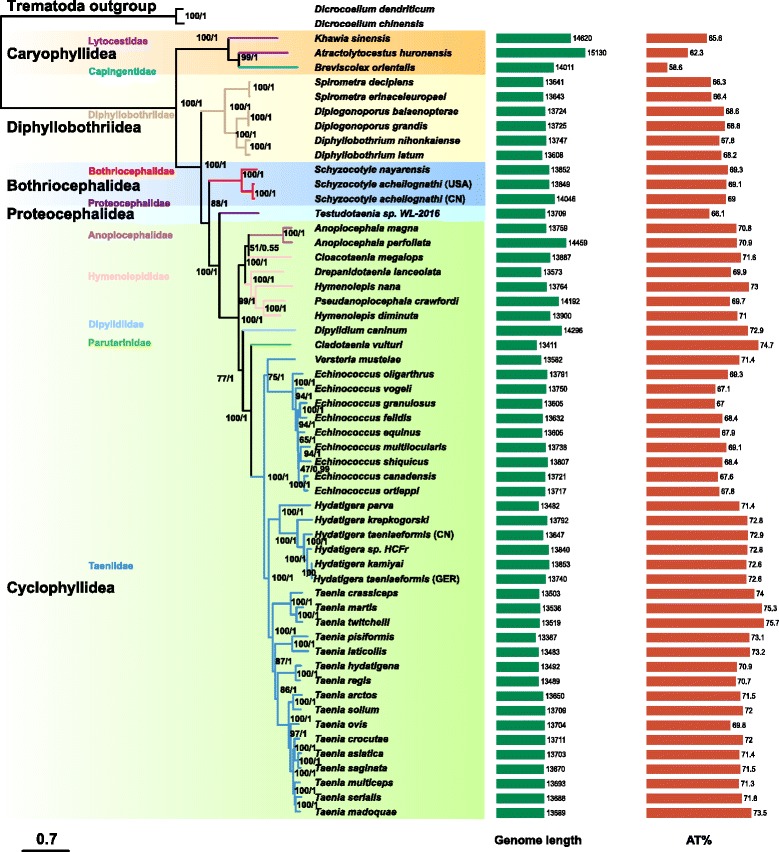

Fig. 2.

Maximum-likelihood tree inferred from 36 genes (12 protein-coding genes, 2 rRNAs and 22 tRNAs) of mitochondrial genomes of 54 cestode species from five orders, using two trematoda species as outgroups. Scale-bar represents the estimated number of substitutions per site. Bootstrap/posterior probability support values of ML/BI analysis are shown above the nodes. The bar graph (corresponding to tip labels in the tree) of the mitogenome length and A-T content are shown on the right of the tree

Protein-coding genes and codon usage

The size of the 12 PGCs ranged from 258 bp (nad4L) to 1554 bp (nad5) for the three caryophyllideans, but from 258 bp (nad4L) to 1584 bp (cox1) for S. acheilognathi (CN) (Additional file 3: Table S3). Only two types of start codons (ATG and GTG) were inferred from the sequence data of the four cestodes. GTG was used as a start codon for the following genes: nad2, nad3, cox2, nad5 and nad6 in A. huronensis, nad2, nad3, nad5 and nad6 in B. orientalis and nad4, nad4L in S. acheilognathi (CN). The rest of the PCGs of the aforementioned cestodes and all of the PCGs of K. sinensis used ATG as a start codon. From the three predicted stop codons, TAG, TAA and the abbreviated stop codon T, TAG was the most frequently occurring stop codon, followed by TAA and finally T. The unusual stop codon T encoded for cox3 in A. huronensis, B. orientalis and S. acheilognathi (CN) and cox2, cox3 and nad3 in K. sinensis (Table 1). RSCU for the four cestode mtDNAs calculated using the echinoderm mt genetic code are presented in Additional file 4: Figure S1. Overall, the three most commonly used T-rich codons for the three Caryophyllidea cestodes (A. huronensis, B. orientalis and K. sinensis) were Val (GTT), Leu (TTG) and Phe (TTT) compared with Tyr (TAT), Leu (TTG) and Phe (TTT) for S. acheilognathi (CN).

Transfer and ribosomal RNA genes

All 22 tRNAs from the mt genome of each Caryophyllidea species were concatenated. This created a total concatenated length of 1363 bp, 1378 bp, 1354 bp and 1404 bp for A. huronensis, B. orientalis, K. sinensis and S. acheilognathi (CN), respectively (Additional file 3: Table S3). Each tRNA identified from these four species, could be folded into the traditional cloverleaf structure, with the exception of tRNA Ser(AGN) and tRNA Arg in B. orientalis, K. sinensis and S. acheilognathi (CN) and tRNA Ser(AGN), tRNA Arg and tRNA Cys in A. huronensis, which all lacked DHU arms (Additional file 5: Figure S2). All tRNAs had the standard anti-codons found in flatworms (Table 1), except tRNA Ser(AGN) in K. sinensis which had an anti-codon of TCT. The two ribosomal RNA genes, rrnL and rrnS were flanked by tRNA Thr and cox2 and separated by tRNA Cys. This was identical in all the cestodes for which a mitogenome was available (Additional file 6: Figure S3). The boundary of the rrnL gene for S. acheilognathi (CN) was redefined, being approximately 100 bp shorter than that of previously published mitogenomes. This is due to the difference in defining the boundary (Additional file 7: Figure S4) [36]. Thus, there was an additional 124 bp NCR located between tRNA Thr and rrnL. Additionally, to conduct phylogenetic analysis and linear order comparison (see later), we proposed a reasonable tRNA Gln annotation to a recently reported mitogenome from Testudotaenia sp. WL-2016 (KU761587) based upon alignments with other cestodes.

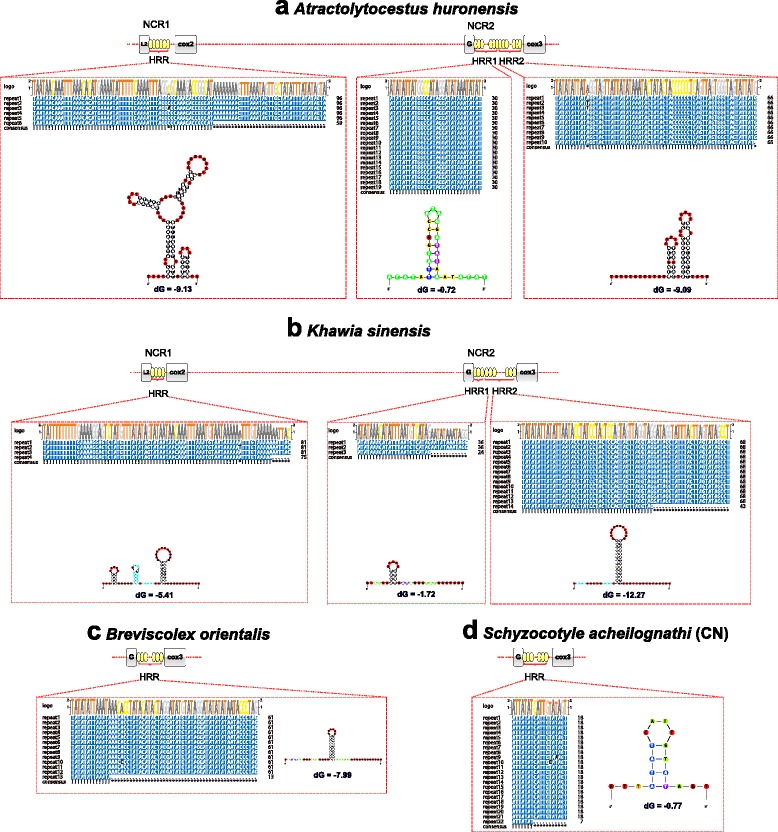

Non-coding regions

The position of the NCR in all cestodes was identified with a threshold value of 50 bp. The majority of cestodes contained two NCRs, except for Pseudanoplocephala crawfordi [37], Taenia crocutae [38], Taenia solium [39] and S. acheilognathi (CN) all of which had three NCRs, and Hydatigera taeniaeformis which has just one NCR. These NCRs occurred in the junctions of rrnS-tRNA Arg (P1) and nad5-cox3 (P2) (Additional file 6: Figure S3). The length of the major NCRs were 873 bp (NCR1) and 1283 bp (NCR2) in A. huronensis, 549 bp (NCR1) and 1083 bp (NCR2) in K. sinensis, 208 bp (NCR1) and 825 bp (NCR2) in B. orientalis and 124 bp (NCR1), 166 bp (NCR2) and 499 bp (NCR3) in S. acheilognathi (CN). The concatenated size (2156 bp) of all NCRs from A. huronensis was the longest of all the cestodes (Additional file 3: Table S3). Various highly repetitive regions (HRRs) were detected in NCRs from the four cestode species, and the consensus repeats were capable of forming stem loop structures (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Highly repetitive regions (HRRs) and their secondary structures of the consensus repeat units in the major non-coding regions (NCRs) of the mitochondrial genomes of Atractolytocestus huronensis (a), Khawia sinensis (b), Breviscolex orientalis (c) and Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (China, CN) (d). Thermodynamic value (dG) is shown under the secondary structure

Phylogeny and gene order

Both phylogenetic trees (BI and ML) demonstrated high statistical support for branch topology, especially on the order level (BP ≥ 85, BPP = 1). Since the two trees had the same topology, only the latter was shown (Fig. 2). The most derived Cyclophyllidea cestodes, together with the Proteocephalidea (represented by Testudotaenia sp. WL-2016), constitute a reciprocal monophyletic group with the Bothriocephalidea. This clade formed a sister-group to the Diphyllobothriidea, and all clades exhibited a sister-group relationship with the basal Caryophyllidea (Fig. 2). Breviscolex orientalis belonging to the family Capingentidae clustered into a well-supported clade with A. huronensis from the family Lytocestidae inferred by a maximum possible nodal support (BP = 100, BPP = 1) which formed a sister-group relationship with another Lytocestidae species, K. sinensis.

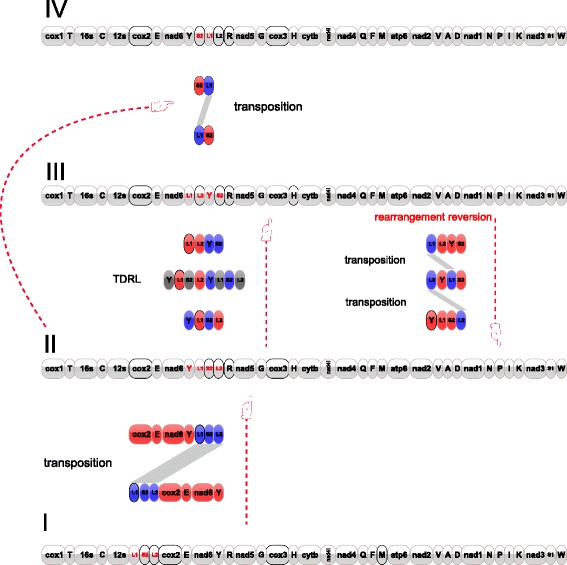

Amongst the 54 mitogenomes across the five orders, each order had a unique arrangement except for the Cyclophyllidea which had two types: group 1 (represented by the Taeniidae) was identical to the Diphyllobothriidea, and group 2 (represented by the Hymenolepididae, Anoplocephalidae, Dipylidiidae and Paruterinidae) was identical to the Proteocephalidea. These corresponded to four mt gene arrangement categories: I, Caryophyllidea; II, Diphyllobothriidea and group 1; III, Bothriocephalidea; IV, Proteocephalidea and group 2 (Fig. 4). Pairwise analysis between the four gene arrangement categories indicated similarities (common intervals algorithm) in the gene order between unsegmented and segmented cestodes to be lower than within segmented cestodes (Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Rearrangement events predicted by CREx to explain gene order changes among the four mitogenome arrangements categories, Caryophyllidea (I), Diphyllobothriidea and Cyclophyllidea group 2 (II), Bothriocephalidea (III), Proteocephalidea and Cyclophyllidea group 1 (IV). L1, tRNA Leu(CUN); L2, tRNA Leu(UUR), S2, tRNA Ser(UCN); E, tRNA Glu; Y, tRNA Tyr; TDRL, tandem-duplication-random-loss

Table 2.

Pairwise comparisons of mitochondrial DNA gene orders among the four categories of mitogenome arrangements (see Fig. 4)

| I | II | III | IV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1254 | |||

| II | 832 | 1254 | ||

| III | 818 | 992 | 1254 | |

| IV | 828 | 1122 | 996 | 1254 |

Scores indicate the similarity between gene orders, where “1254” represents an identical gene order

Discussion

In the phylogenetic analysis employed in this study, the Caryophyllidea was resolved as the sister taxon to all other eucestodes in line with previous studies. Although only five orders of cestodes are included in the phylogenetic analysis, the evolutionary relationships remain consistent with the results generated through morphological examination [1] and sequence data obtained from large fragments of mtDNA [4].

The mitogenome gene order of the cestodes was extremely conservative. Amongst the 54 mitogenomes across the five orders, only four gene arrangement categories were found. With respect to the three types of gene arrangements (II, III and IV) in the segmented cestodes, all the rearrangement operations are acted on the four closely linked tRNA genes (tRNA Leu(CUN)-tRNA Ser(UCN)-tRNA Leu(UUR)-tRNA Tyr) (Fig. 4). When compared with the category I in the unsegmented cestodes, there probably exists a long distance transposition event (the three tRNA genes tRNA Leu(CUN)-tRNA Ser(UCN)-tRNA Leu(UUR) translocate to the 3′ end of the four genes cox2-tRNA Glu-Nad6-tRNA Tyr) (Fig. 4), which may be the main cause of the low similarity value. According to the results of CREx program, the gene rearrangements from category II to category III and IV undergo a tandem-duplication-random-loss (TDRL) event and a simple transposition event, respectively. A TDRL event can provide directional information, allowing the inference of the ancestral state from the comparison of only two taxa because reversing the rearrangement would require more than a single operation [40]. Based on this assumption on TDRL event (Fig. 4), category II may be the ancestral state of the two categories II and III. Two categories of mt gene order were also found in the most derived Cyclophyllidea owing to the transposition of two tRNA genes [41]. However, the two types of gene arrangements are identical to those of the sister order Proteocephalidea and the relatively basal order Diphyllobothriidea.

There are perhaps more gene arrangements in other orders of cestodes; however, due to the limited amount of mitogenome data available so far, we can only but speculate. The rearrangement events that have been observed among the four arrangement categories in this study all took place in P1 as mentioned above (Fig. 4), revealing a rearrangement hot spot. Interestingly, P1 is furthermore the position in which one or two NCRs frequently occurred, and in which highly repetitive regions (HRRs) also are found within the NCRs. Whether an association exists between the rearrangement hot spot and the NCRs is something that requires further investigation to ascertain whether they may be important in the evolution of cestodes.

The phylogenetic relationship between B. orientalis and A. huronensis was found to be closer than that of A. huronensis and K. sinensis, which conflicts with classic systematics. On the basis of the paramuscular position of the vitelline follicles, B. orientalis is placed into the family Capingentidae Kulakovskaya, 1962, being the only member of this family found in the Palaearctic region. However, the fibres of the longitudinal musculature are situated mostly in the inner region of the vitelline field or entirely medullary to it, which is similar to the topography present in the Lytocestidae which possess cortically situated vitelline follicles [42]. Breviscolex orientalis has a cuneiform scolex, as do both species of Caryophyllaeides Nybelin, 1922 in the Lytocestidae [16]. These results suggest that the morphological characters of B. orientalis are closer to those of the Lytocestidae. Despite the similar result found in this study, relocation of B. orientalis, the only member of the family Capingentidae, into the family Lytocestidae, needs more molecular support.

Conclusions

Among the four arrangement categories, the rearrangement events are detected in P1 where the NCRs with highly repetitive regions (HRRs) are common. A putative long-distance transposition event is detected between the unsegmented and segmented cestodes. The TDRL event suggests that the mt gene arrangement of the Diphyllobothriidea is the ancestral state relative to Bothriocephalidea. Gene arrangements of the Taeniidae and the rest of the families in the Cyclophyllidea are found to be identical to those of the sister order Proteocephalidea and the relatively basal order Diphyllobothriidea, respectively.

Additional files

Primers used to amplify and sequence the mitochondrial genome of the cestodes Atractolytocestus huronensis, Khawia sinensis, Breviscolex orientalis and Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (CN). (XLSX 26 kb)

Characteristics of the 54 cestode mitochondrial genomes as well as two trematode outgroups in this study. (XLSX 20 kb)

Skewness and A + T content (%) of the protein-coding genes (PCGs), tRNAs, rRNA genes, each codon position of PCGs and non-coding region of the mitochondrial genome of the cestodes Atractolytocestus huronensis, Khawia sinensis, Breviscolex orientalis and Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (CN). (XLSX 16 kb)

The relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values of the complete mitochondrial genome of the cestodes Atractolytocestus huronensis, Khawia sinensis, Breviscolex orientalis and Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (CN). (PDF 122 kb)

Secondary structure (lacking DHU arms) of the tRNA genes of the cestodes Atractolytocestus huronensis, Khawia sinensis, Breviscolex orientalis and Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (CN). (PDF 472 kb)

Mitochondrial gene order (include non-coding regions) of the 54 cestode species in this study. (PDF 3548 kb)

The sequence alignment of the first 200 bp of the 16S rRNA gene from the 54 cestode species in this study. (PDF 635 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. P. Nie for some suggestions to improve the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31,272,695, 31,572,658, 31,302,222), the Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System (CARS-46-08) and the major scientific and technological innovation project of Hubei Province (2015ABA045).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the GenBank international nucleotide sequence repository under accession numbers KY486752– KY486754, KX589243.

Authors’ contributions

WXL designed the experiments, performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript. DZ performed the laboratory work and the phylogenetic analysis. KB analysed the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2245-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Wen X. Li, Email: liwx@ihb.ac.cn

Dong Zhang, Email: dongzhang0725@gmail.com.

Kellyanne Boyce, Email: K.boyce@edu.salford.ac.uk.

Bing W. Xi, Email: xibw@ffrc.cn

Hong Zou, Email: zouhong@ihb.ac.cn.

Shan G. Wu, Email: wusgz@ihb.ac.cn

Ming Li, Email: liming@ihb.ac.cn.

Gui T. Wang, Email: gtwang@ihb.ac.cn

References

- 1.Hoberg EP, Mariaux J, Justine JL, Brooks DR, Weekes PJ. Phylogeny of the orders of the Eucestoda (Cercomeromorphae) based on comparative morphology: historical perspectives and a new working hypothesis. J Parasitol. 1997;83(6):1128–1147. doi: 10.2307/3284374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olson PD, Caira JN. Evolution of the major lineages of tapeworms (Platyhelminthes: Cestoidea) inferred from 18S ribosomal DNA and elongation factor-1α. J Parasitol. 1999;85(6):1134–59. [PubMed]

- 3.Waeschenbach A, Webster BL, Bray RA, Littlewood DTJ. Added resolution among ordinal level relationships of tapeworms (Platyhelminthes: Cestoda) with complete small and large subunit nuclear ribosomal RNA genes. Mol Phyogenet Evol. 2007;45(1):311–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waeschenbach A, Webster BL, Littlewood DTJ. Adding resolution to ordinal level relationships of tapeworms (Platyhelminthes: Cestoda) with large fragments of mtDNA. Mol Phyogenet Evol. 2012;63(3):834–847. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballard JWO, Whitlock MC. The incomplete natural history of mitochondria. Mol Ecol. 2004;13(4):729–744. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.02063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huyse T, Buchmann K, Littlewood DTJ. The mitochondrial genome of Gyrodactylus derjavinoides (Platyhelminthes: Monogenea) - a mitogenomic approach for Gyrodactylus species and strain identification. Gene. 2008;417(1–2):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zarowiecki MZ, Huyse T, Littlewood DTJ. Making the most of mitochondrial genomes - markers for phylogeny, molecular ecology and barcodes in Schistosoma (Platyhelminthes: Digenea) Int J Parasitol. 2007;37(12):1401–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boore JL, Brown WM. Big trees from little genomes: mitochondrial gene order as a phylogenetic tool. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8(6):668–674. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(98)80035-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boore J. The use of genome-level characters for phylogenetic reconstruction. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21(8):439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masta SE, McCall A, Longhorn SJ. Rare genomic changes and mitochondrial sequences provide independent support for congruent relationships among the sea spiders (Arthropoda, Pycnogonida) Mol Phyogenet Evol. 2010;57(1):59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le TH, Blair D, McManus DP. Mitochondrial genomes of parasitic flatworms. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18(5):206–213. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(02)02252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Littlewood DTJ, Lockyer AE, Webster BL, Johnston DA, Le TH. The complete mitochondrial genomes of Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma spindale and the evolutionary history of mitochondrial genome changes among parasitic flatworms. Mol Phyogenet Evol. 2006;39(2):452–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park JK, Kim KH, Kang S, Kim W, Eom KS, Littlewood DTJ. A common origin of complex life cycles in parasitic flatworms: evidence from the complete mitochondrial genome of Microcotyle sebastis (Monogenea: Platyhelminthes). BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Oros M, Hanzelova V, Scholz T. The cestode Atractolytocestus huronensis (Caryophyllidea) continues to spread in Europe: new data on the helminth parasite of the common carp. Dis Aquat Org. 2004;62(1–2):115–119. doi: 10.3354/dao062115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oros M, Hanzelová V, Scholz T. Tapeworm Khawia sinensis: review of the introduction and subsequent decline of a pathogen of carp, Cyprinus carpio. Vet Parasitol. 2009;164(2):217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oros M, Scholz T, Hanzelová V, Mackiewicz JS. Scolex morphology of monozoic cestodes (Caryophyllidea) from the Palaearctic region: a useful tool for species identification. Folia Parasitol. 2010;57(1):37–46. doi: 10.14411/fp.2010.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Králová-Hromadová I, Štefka J, Špakulová M, Orosová M, Bombarová M, Hanzelová V, et al. Intra-individual internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) and ITS2 ribosomal sequence variation linked with multiple rDNA loci: a case of triploid Atractolytocestus huronensis, the monozoic cestode of common carp. Int J Parasitol. 2010;40(2):175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Littlewood D, Waeschenbach A, Nikolov P. In search of mitochondrial markers for resolving the phylogeny of cyclophyllidean tapeworms (Platyhelminthes, Cestoda) - a test study with Davaineidae. Acta Parasitol. 2008;53(2):133–144. doi: 10.2478/s11686-008-0029-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(5):955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laslett D, Canback B. ARWEN: a program to detect tRNA genes in metazoan mitochondrial nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(2):172–175. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernt M, Donath A, Juhling F, Externbrink F, Florentz C, Fritzsch G, et al. MITOS: improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol Phyogenet Evol. 2013;69(2):313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wyman SK, Jansen RK, Boore JL. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(17):3252–3255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang D. MitoTool software. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(2):573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beitz E. T(E)Xshade: shading and labeling of multiple sequence alignments using (LTEX)-T-A 2(epsilon) Bioinformatics. 2000;16(2):135–139. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernt M, Merkle D, Ramsch K, Fritzsch G, Perseke M, Bernhard D, et al. CREx: inferring genomic rearrangements based on common intervals. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(21):2957–2958. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang D. BioSuite software. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keane TM, Creevey CJ, Pentony MM, Naughton TJ, McLnerney JO. Assessment of methods for amino acid matrix selection and their use on empirical data shows that ad hoc assumptions for choice of matrix are not justified. BMC Evol Biol. 2006;6:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silvestro D, Michalak I. raxmlGUI: a graphical front-end for RAxML. Org Divers Evol. 2011;12(4):335–337. doi: 10.1007/s13127-011-0056-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61(3):539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brabec J, Kuchta R, Scholz T, Littlewood DTJ. Paralogues of nuclear ribosomal genes conceal phylogenetic signals within the invasive Asian fish tapeworm lineage: evidence from next generation sequencing data. Int J Parasitol. 2016;46(9):555–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao GH, Wang HB, Jia YQ, Zhao W, Hu XF, Yu SK, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of Pseudanoplocephala crawfordi and a comparison with closely related cestode species. J Helminthol. 2016;90(5):588–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Terefe Y, Hailemariam Z, Menkir S, Nakao M, Lavikainen A, Haukisalmi V, et al. Phylogenetic characterisation of Taenia tapeworms in spotted hyenas and reconsideration of the “out of Africa” hypothesis of Taenia in humans. Int J Parasitol. 2014;44(8):533–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakao M, Sako Y, Ito A. The mitochondrial genome of the tapeworm Taenia solium: a finding of the abbreviated stop codon U. J Parasitol. 2003;89(3):633–635. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2003)089[0633:TMGOTT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perseke M, Fritzsch G, Ramsch K, Bernt M, Merkle D, Middendorf M, et al. Evolution of mitochondrial gene orders in echinoderms. Mol Phyogenet Evol. 2008;47(2):855–864. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo A. The complete mitochondrial genome of the tapeworm Cladotaenia vulturi (Cestoda: Paruterinidae): gene arrangement and phylogenetic relationships with other cestodes. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:475. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1769-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scholz T, Shimazu T, Olson PD, Nagasawa K. Caryophyllidean tapeworms (Platyhelminthes: Eucestoda) from freshwater fishes in Japan. Folia Parasitol. 2001;48(4):275–288. doi: 10.14411/fp.2001.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Primers used to amplify and sequence the mitochondrial genome of the cestodes Atractolytocestus huronensis, Khawia sinensis, Breviscolex orientalis and Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (CN). (XLSX 26 kb)

Characteristics of the 54 cestode mitochondrial genomes as well as two trematode outgroups in this study. (XLSX 20 kb)

Skewness and A + T content (%) of the protein-coding genes (PCGs), tRNAs, rRNA genes, each codon position of PCGs and non-coding region of the mitochondrial genome of the cestodes Atractolytocestus huronensis, Khawia sinensis, Breviscolex orientalis and Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (CN). (XLSX 16 kb)

The relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values of the complete mitochondrial genome of the cestodes Atractolytocestus huronensis, Khawia sinensis, Breviscolex orientalis and Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (CN). (PDF 122 kb)

Secondary structure (lacking DHU arms) of the tRNA genes of the cestodes Atractolytocestus huronensis, Khawia sinensis, Breviscolex orientalis and Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (CN). (PDF 472 kb)

Mitochondrial gene order (include non-coding regions) of the 54 cestode species in this study. (PDF 3548 kb)

The sequence alignment of the first 200 bp of the 16S rRNA gene from the 54 cestode species in this study. (PDF 635 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the GenBank international nucleotide sequence repository under accession numbers KY486752– KY486754, KX589243.