Abstract

Background/Aims

Studies concerning the efficacy and safety of single-balloon enteroscopy (SBE) compared with that of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) often appear to be conflicting. However, previous studies were performed by endoscopists who were less experienced in SBE compared with DBE.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of SBE and DBE data performed by a single enteroscopist, with expertise in SBE, using a prospective balloon-assisted enteroscopy registry from 2013 to 2015. Furthermore, we performed a comprehensive literature search and meta-analysis of available studies, including the current study, to clarify the efficacy and safety of SBE versus DBE.

Results

A total of 65 procedures in 44 patients with SBE and 74 procedures in 69 patients with DBE were analyzed. There were no significant differences in diagnostic yield (61.1% vs 77.3%, respectively, p=0.397), therapeutic yield (39.1% vs 31.8%, respectively, p=0.548), and complication rate (4.4% vs 2.3%, p=1.000). In the meta-analysis, which included four randomized controlled trials and three observational studies, there were no significant differences in the pooled relative risk and odds ratio for diagnostic and therapeutic yield and complications of SBE compared with those of DBE.

Conclusions

The performance of SBE appears to be similar to that of DBE in terms of diagnostic and therapeutic yield and complications.

Keywords: Single-balloon enteroscopy, Double-balloon enteroscopy, Balloon-assisted enteroscopy, Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Despite increasing experience, deep enteroscopy remains challenging for the evaluation of small bowel diseases.1 Balloon-assisted enteroscopy (BAE) is a novel endoscopic technique that allows deep insertion of the endoscope and permits small bowel mucosa evaluation. There are now two forms of BAE: double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) and single-balloon enteroscopy (SBE). DBE was developed in 2001 and has been considered the standard endoscopic technique for small-bowel visualization.2 However, the preparation and handling of the DBE system are complex. SBE was introduced as a simplified and less-complex BAE system.3

Previous randomized controlled trials (RTC) were conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of SBE versus DBE. The results of these RTCs tended to reveal a better diagnostic and therapeutic yield of DBE than SBE, even though they did not find statistical significance.4–7 However, previous RCTs were performed by less experienced endoscopists in SBE, compared to DBE.4,5,7 Although both DBE and SBE adopted the push and pull technique, the instruments used and technique details are different. Therefore, SBE requires a learning curve to achieve expertise, as like in DBE.8

A comparison of SBE versus DBE, performed by an endoscopist, who has more expertise in SBE than DBE, may be needed to get a balanced viewpoint in order to identify a diagnostic and therapeutic priority between SBE and DBE. This study aimed to compare the diagnostic yield, therapeutic yield, and complication rate of SBE versus DBE performed by a single endoscopist with more expertise in SBE than DBE. Furthermore, in order for a more generally applicable conclusion to be drawn, we performed meta-analyses that identified similar effects in various populations using RCTs and comparison studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study population

In a prospective BAE registry between May 2013 and February 2015, in the Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, we extracted the SBE and DBE data performed by a single experienced endoscopist (S.N.H.), who had carried out more than 100 procedures of SBE and just 10 cases of experience performing DBE, prior to the study period. The indication between the SBE or DBE was the same and was allocated to time intervals. DBE was performed prior to August 2014 and SBE was performed after September 2014. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients ≥15 years old who had undergone BAE, including DBE and SBE, (2) BAE was performed by the single experienced endoscopist, who had proficient experience in SBE and limited experience in DBE. The following patients were excluded: (1) age <15 years, (2) BAE was performed to evaluate the pathology of outside the small intestine, including balloon–assisted colonoscopy in patients with previously failed colonoscopy. Data collection and analysis protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center.

2. Balloon-assisted enteroscopy

There are two types of BAE systems: the DBE system, which uses two balloons; and the SBE system which employs only a single balloon. DBE was performed using a double-balloon enteroscope (EN-450T5/20; Fujinon Inc., Saitama, Japan) and the balloon is attached on the tip of the enteroscope and the over-tube. SBE was performed by a single-balloon enteroscope (SIF-Q180; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and the balloon is attached only to the overtube.

3. Insertion technique

The insertion route was determined based on the clinical manifestation, capsule endoscopy or imaging study. DBE and SBE is performed by a 2-person, an endoscopist and an assistant, and was often underwent under fluoroscopic guidance. The procedure can be performed via the mouth (anterograde) or through the anus (retrograde). A push and pull technique was adopted in both DBE and SBE. The enteroscope advance through the small intestine by alternately inflating and deflating balloons, and bringing the small intestine to the endoscopist by pleating the intestine over an overtube, just like pulling a curtain over a rod. However, the insertion technique differed between DBE and SBE, because of the difference in instruments utilized.9 The depth of insertion into the small bowel (SB) was calculated according to the methods described previously.10 When the overtube is advanced toward the tip of the enteroscope, the balloon on the tip of the enteroscope is inflated and anchored to maintain a stable position in DBE, whereas SBE is anchored enteroscope using its flexible tip.

A total enteroscopy means successful visualization of entire small intestine. Total enteroscopy using unilateral approach alone was possible; however, bilateral approaches are often used to observe the entire small intestine. During enteroscopy, therapeutic interventions and biopsies were performed during BAE, when it is indicated.

4. BAE-related factors

The diagnostic yield, depth of maximal insertion, insertion and total procedure time, attempt and success of total enteroscopies and therapeutic intervention, and complications were measured or collected. The indications for BAE were categorized as follow: obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB), abnormal imaging findings, unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms and/ or signs, neoplastic lesion or polyposis, SB obstruction, therapeutic intervention, and others.

Any BAE-associated complications were referred as event-associated BAE procedures, which included postprocedure elevated amylase and perforation. Postprocedure elevated amylase was diagnosed when the serum amylase levels reached at least two times the upper normal limit without pancreatic-type abdominal pain.

5. Literature search

A literature search was conducted using MEDLINE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) for potentially relevant articles published before December 2015. The following terms were used for the key words search, small bowel enteroscopy, deep enteroscopy, balloon-assisted enteroscopy, single-balloon enteroscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy. A total of 173 articles were identified using this search strategy. Abstracts of articles from the literature search were individually evaluated independently for possible inclusion by the two authors. Studies meeting the following criteria were included: (1) English-language, (2) full manuscript publication, (3) studies subjected to adult population, and (4) study design: clinical trials including RCT and observational study with comparison of diagnostic yield, total enteroscopy rate, therapeutic yield, and complication rate between SBE and DBE. Complete texts were obtained for articles that were potentially relevant. Recursive searches of the reference sections of selected studies were performed manually to identify other potentially relevant articles. The results were combined and cross-checked, and any differences were resolved by reviewing the article and settled by consensus. In total, 167 articles were excluded from the initial literature pool, and the full manuscripts of the remaining four RCTs4–7 and two observational studies11,12 were reviewed in detail.

6. Statistical analysis

Chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used to compare proportions and t-test was used to compare means between two groups. Two-tailed p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using MedCalc software version 11.6 (MedCalc, Mariakerke, Belgium). The diagnostic yield was calculated by the ratio of the number of procedures with significant BAE findings to total procedures. The therapeutic yield was calculated by the ratio of procedures with intervention to total procedures. The diagnostic and therapeutic yield was presented in 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

For the meta-analysis, risk ratios (RR) were retrieved from the published RTCs and odds ratios (OR) were retrieved from published observational studies. As clinical heterogeneity of study participants, study designs, and definitions were present among the studies selected for the meta-analysis, a random-effects model was applied. The pooled estimates were calculated using the inverse variance weighted estimation method. A test for heterogeneity across the studies was also performed. A p-value <0.10 indicated statistically significant heterogeneity across studies. The meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager version 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).

RESULTS

During the study period, 73 DBE procedures (37 anterograde approaches and 36 retrograde approaches) in 69 patients and 65 SBE procedures (39 anterograde approaches and 26 retrograde approaches) in 44 patients, were performed (Table 1). The mean age of the enrolled patients was 50.4±49.5 years and 73 patients were male (52.9%). OGIB was the most common indication in both groups, followed by neoplastic lesion or polyposis, abnormal finding of imaging studies, unexplained symptoms and/or signs, and others. There were no significant differences observed for age, gender, insertion route, and indication between the DBE and SBE groups.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Enrolled Patients

| DBE group (n=73) | SBE group (n=65) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 50.6±17.9 | 50.1±22.0 | 0.894 |

| Male/female | 35/38 | 38/27 | 0.236 |

| Insertion route | 0.279 | ||

| Oral approach | 37 | 39 | |

| Anal approach | 36 | 26 | |

| Indications | 0.296 | ||

| Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding | 43 | 31 | |

| Abnormal finding of imaging studies | 7 | 6 | |

| Unexplained GI symptoms and/or sign | 3 | 5 | |

| Neoplastic lesion or polyposis | 15 | 12 | |

| Others | 0 | 3 |

Data are presented as mean±SD.

DBE, double-balloon enteroscopy; SBE, single-balloon enteroscopy; GI, gastrointestinal.

1. BAE procedure-related factors

Table 2 shows the insertion depth and procedure times of the anterograde and retrograde approaches in the DBE and SBE group. In the anterograde approach, there was no significant difference in the depth of insertion between the DBE and SBE group (198±69 cm vs 177±99 cm, p=0.273); however, the insertion and total procedure time of SBE was shorter than that of DBE (43±20 minutes vs 29±18 minutes, p=0.002 and 77±24 minutes vs 48±27 minutes, p<0.001, respectively). In the retrograde approach, there was no significant difference in the depth of insertion, the insertion, and total procedure time, although the insertion and total procedure time of SBE showed a shorter tendency in the SBE group.

Table 2.

Insertion Depth and Procedure Times of Anterograde and Retrograde Approaches in the DBE and SBE Groups

| Anterograde approach | Retrograde approach | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| DBE group | SBE group | p-value | DBE group | SBE group | p-value | |

| Depth of insertion, cm | 198±69 | 177±99 | 0.273 | 141±68 | 123±53 | 0.278 |

| Insertion time, min | 43±20 | 29±18 | 0.002 | 52±20 | 42±24 | 0.076 |

| Total procedure time, min | 77±24 | 48±27 | <0.001 | 78±28 | 64±38 | 0.098 |

Data are presented as mean±SD.

DBE, double-balloon enteroscopy; SBE, single-balloon enteroscopy.

Total enteroscopy was attempted in 20 patients in the DBE group and was successful in seven patients (35.0%). In the SBE group, total enteroscopy was attempted in 16 patients and was successful in two patients (12.5%); however, there was no significant difference between groups (p=0.245).

2. Diagnostic yields

The diagnostic yields of SBE and DBE are summarized in Table 3. The overall diagnostic yield of DBE was 67.1% (55.0% to 77.4%), and of SBE was 64.6% (50.8% to 74.9%). There was no significant difference in diagnostic yield between DBE and SBE groups (p=0.857). Inflammatory lesions were the most common finding in both groups, which included Crohn’s disease, intestinal tuberculosis, stenosis, radiation enteritis, protein losing enteropathy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced enteropathy, Behçet’s enteritis, anastomosis site ulcer, and eosinophilic enteritis. In the DBE group, neoplastic lesions were second most common finding and followed by vascular lesions, diverticular lesions, other lesions, and lesions in stomach, duodenum, or colon. In the SBE group, other lesions were the second most common finding, which included recent suspected small intestinal bleeding without bleeding focus, prominent ampulla of Vater, graft-versus-host disease, extrinsic compression, amyloidosis, and enteroscopy-assisted endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Neoplastic lesions, lesions of the stomach, duodenum, or colon, vascular lesions, and diverticular lesions followed. When we included BAE performed for OGIB, the diagnostic yield of DBE was 55.8% (40.0% to 70.6%), whereas that of SBE was 58.1% (39.2% to 74.9%). There was no significant difference in diagnostic yields of patients with OGIB between DBE and SBE groups (p=1.000).

Table 3.

Diagnostic Yield of Small Intestinal Diseases in the DBE and SBE Groups

| Enteroscopic finding | Any indication | Obscure GI bleeding | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| DBE group (n=73) | SBE group (n=65) | p-value | DBE group (n=43) | SBE group (n=31) | p-value | |

| Significant finding | 49 (67.1) | 42 (64.6) | 0.857 | 24 (55.8) | 18 (58.1) | 1.000 |

| Inflammatory lesion | 20 | 13 | 7 | 5 | ||

| Vascular lesion | 11 | 3 | 9 | 3 | ||

| Neoplastic lesion | 12 | 7 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Lesions in stomach, duodenum, or colon | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Diverticular lesion | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Other lesion | 2 | 12 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Negative finding | 24 (32.9) | 24 (36.9) | 19 (44.2) | 13 (41.9) | ||

Data are presented number (%).

DBE, double-balloon enteroscopy; SBE, single-balloon enteroscopy; GI, gastrointestinal.

3. Therapeutic yields

The therapeutic yields of SBE and DBE are summarized in Table 4. Therapeutic interventions during DBE were performed during 31 procedures (42.5%, 31.2% to 54.6%) and during SBE, 23 procedures (35.4%, 24.2% to 48.3%). There was no significant difference in therapeutic yields between DBE and SBE groups (p=0.485). The most common therapeutic intervention was endoscopic hemostasis and followed by polypectomy in the DBE group, followed by balloon dilation. When we included BAE performed for OGIB, the diagnostic yield of DBE was 39.5% (25.4% to 55.6%), whereas that of SBE was 35.5% (19.8% to 54.6%). There was no significant difference in therapeutic yields in patients with OGIB between the DBE and SBE groups (p=0.810).

Table 4.

Therapeutic Yield in the DBE and SBE Groups

| Therapeutic intervention | Any indication | Obscure GI bleeding | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| DBE group (n=73) | SBE group (n=65) | p-value | DBE group (n=43) | SBE group (n=31) | p-value | |

| Any intervention | 31 (42.5) | 23 (35.4) | 0.485 | 17 (39.5) | 11 (35.5) | 0.810 |

| Hemostasis | 15 | 8 | 15 | 8 | ||

| Polypectomy | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Balloon dilation | 5 | 7 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Tattooing | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | ||

| ERCP assist | 0 | 3 | - | - | ||

| Biopsy | 22 (30.1) | 10 (15.4) | 13 (30.2) | 2 (6.5) | ||

| No intervention | 42 (57.5) | 42 (64.6) | 26 (60.5) | 20 (64.5) | ||

Data are presented number (%).

DBE, double-balloon enteroscopy; SBE, single-balloon enteroscopy; GI, gastrointestinal; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

4. Complication rate

There were significant BAE-associated complications reported in four procedures (2.9%) (Table 5). In the DBE group, two post-procedure elevated amylase occurred (2.7%, 0.4% to 10.4%). In the SBE group, two complications, which included one postprocedure elevated amylase and one perforation, occurred (3.1%, 0.5% to 11.6%). There was no significant difference between the groups.

Table 5.

Complication Rates in the DBE and SBE Groups

| Complication | Any indication | Obscure GI bleeding | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| DBE group (n=73) | SBE group (n=65) | p-value | DBE group (n=43) | SBE group (n=31) | p-value | |

| Presence | 2 (2.7) | 2 (3.1) | 1.000 | 2 (4.7) | 0 | 0.506 |

| Postprocedure elevated amylase | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Perforation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Absence | 71 (97.3) | 63 (96.9) | 41 (95.3) | 31 (43.1) | ||

Data are presented number (%).

DBE, double-balloon enteroscopy; SBE, single-balloon enteroscopy; GI, gastrointestinal.

5. Meta-analysis

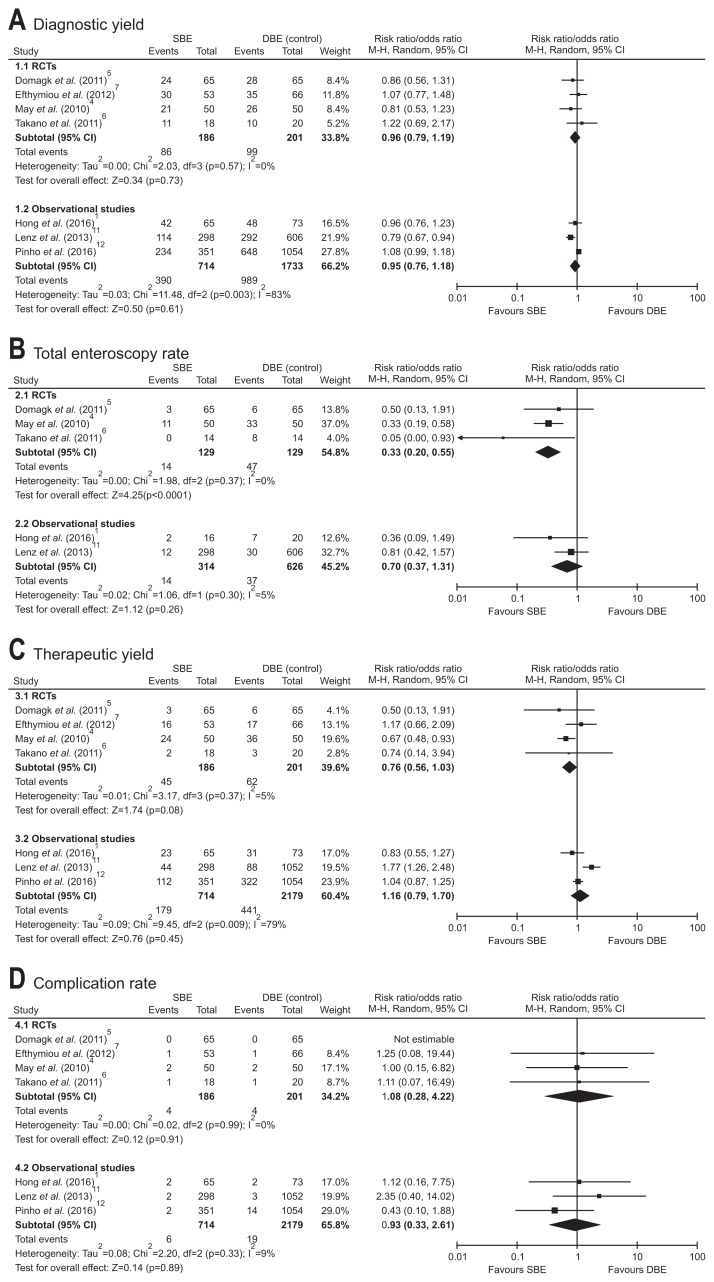

For the meta-analysis, we included four RCTs with a total of 387 patients4–7 and three observational studies, including present analysis with a total of with 2,447 patients (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1).11,12 The pooled RR for diagnostic yield, total enteroscopy rate, therapeutic yield, and complication rate of SBE compared to DBE was 0.96 (95% CI, 0.79 to 1.19), 0.33 (95% CI, 0.20 to 0.55), 0.76 (95% CI, 0.56 to 1.03), and 1.08 (95% CI, 0.28 to 4.22), respectively (Fig. 1). There was no significant heterogeneity between the included studies. The pooled OR for diagnostic yield, total enteroscopy rate, therapeutic yield, and complication rate of SBE compared to DBE was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.76 to 1.18), 0.70 (95% CI, 0.37 to 1.31), 1.16 (95% CI, 0.79 to 1.70), and 0.93 (95% CI, 0.33 to 2.61), respectively (Fig. 1). There was significant heterogeneity in diagnostic yield and therapeutic yield between the included studies (p=0.003 and p=0.009, respectively). The pooled estimates for diagnostic yield, therapeutic yield, and complication rate of SBE was similar to those of DBE. However, the total enteroscopy rate obtained from RCTs data was significantly lower in SBE compared to that in DBE (p<0.001); however, there was no significant differences in total enteroscopy rate obtained from observational studies (p=0.260). The funnel plot of the four studies appeared to be symmetrical (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Forest plot for (A) the diagnostic yield, (B) the total enteroscopy rate, (C) the therapeutic yield, and (D) the complication rate of single-balloon enteroscopy (SBE) compared with double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE). RCT, randomized controlled trial.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of SBE, compared to DBE. Despite the available evidence from prospective RCTs, examiner bias could not be completely ruled out, because most endoscopists performing BAE in previous RCTs were more familiar with DBE than SBE. Previous meta-analysis performed by including only RCTs, showed that, in terms of total enteroscopy rate, there are statistically significant benefits from DBE when compared with SBE.13,14 Because DBE was introduced earlier than SBE and BAE is operator-dependent procedure,2,8 that result is as it should be for earlier RCTs. As the experience of SBE has been accumulated, a large-scale comparative studies were reported using registry database. Present study and meta-analysis from large-scale comparative studies showed similar total enteroscopy rate between DBE and SBE. Indubitably, DBE and SBE were similar with terms of diagnostic and therapeutic yield and complications.

In previous RCTs, DBE showed the tendency of deeper insertion depth and higher total enteroscopy rate than SBE, which thought by better anchoring the intestine using the balloon on the enteroscope tip in DBE compared with the angled tip in SBE.13 However, the balloon on the enteroscope tip in DBE is smaller than balloon on overtube and tended to be easy to slip along over the small bowel wall. Furthermore, some insertion technique of SBE, such as additional left-right angulation and suction to hold the small bowel during advancement of the splinting tube, was introduced and may improve performance of SBE.15 Therefore, we’d like to focus on an additional consideration is the less experience with performing SBE compared with DBE, as it is a newer technique among BAE. When we reviewed the previous RCTs in detail, endoscopists enrolled in RCT performed by Takano et al.6 had more experience with DBE than with SBE. The endoscopist had experience of 248 DBEs and 10 SBEs. The endoscopists enrolled in RCT performed by May et al.4 had experience in DBE, each of whom had previously performed at least 50 DBE procedures; however, training in the SBE technique had been provided for only 2 months beforehand. Although the endoscopists enrolled in the RCT performed by Domagk et al.5 were more experienced in the SBE technique, endoscopists in each trial center had experienced over 50 SBE procedures before the study and acknowledged that the endoscopists were more experienced in DBE. The RCT performed by Efthymiou et al.7 did not mentioned the experience of SBE of the enrolled endoscopist. The insertion technique and manipulation of instruments for SBE are newer and quite different from that of DBE, some differences may be due to the “learning curve” of SBE, which might be comparable to the earlier reported learning curve of the DBE technique.14 Furthermore, the RCT was conducted in a clinical setting, which had a gap with real-time practice.

On the other hand, the large-scale observational studies reflect real-time practice. The endoscopists enrolled in our study and large-scale comparative studies to assess the efficacy and safety of SBE compared to DBE had a sufficient experience in the SBE technique. Our meta-analysis using observational studies included three studies with a total of with 2,447 patients. There was no significant difference in the total enteroscopy rate between the SBE and DBE. Our view is that the results of meta-analysis using a large observational study might have a more favorable reflection of real-time practice.9

In the terms of efficacy, DBE and SBE showed no significant differences in diagnostic and therapeutic yields in this study and meta-analysis. In the terms of safety, the complication rate of DBE and SBE should be evaluated. The most serious complications of BAE are acute pancreatitis, bleeding, and perforations,9 which showed no significant difference between the DBE and SBE. In the combined data for RCTs, we found only four complications in each of the 186 patients that underwent SBE and 201 patients underwent DBE, respectively. In addition, in the combined data for observational studies, we found only six complications in 714 patients that underwent SBE and 19 complications in the 2,179 patients that underwent DBE, respectively. These complications were lower, which suggests that deep enteroscopy, using either SBE or DBE, is a safe procedure.

This study has some limitations. First, although this study used a prospective registry of all procedures, the databases were not designed for this study and the analysis was performed retrospectively. Consequently, this can induce some minor variations. Second, compared with previous RCTs, the number of cases was not small, but the absolute number of included cases was limited. Third, this study was performed by a single center by a single experienced endoscopist. The results may not be generalizable to other settings and less experienced endoscopists for BAE. Furthermore, the study endoscopists are familiar with SBE, and the potential exists for a learning curve effect on the outcomes for DBE. The experience with DBE was considerably less before study commencement. Thus, the outcomes achieved with DBE could possibly improve with increasing experience. To overcome this limitation, we performed a meta-analysis that included observational retrospective studies.

Our observed findings can be implied in future research. Additional high-quality RCTs to confirm the superiority of both methods in respect to the clinical benefits and outcomes should be needed; future studies also consider reporting the long-term follow-up result of each method. Our results demonstrate that SBE and DBE, in terms of diagnostic and therapeutic yield, and complications, are not significantly different, and either one is a reasonable option for small bowel diagnostic and therapeutics.

Supplementary Data

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea, which is funded by the South Korean government (NRF-2014R1A2A1A11052136).

Footnotes

See editorial on page 451.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hong SN, Kim ER, Ye BD, et al. Indications, diagnostic yield, and complication rate of balloon-assisted enteroscopy (BAE) during the first decade of its use in Korea. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:443–449. doi: 10.1111/den.12593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, et al. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:216–220. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.112181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawamura T, Yasuda K, Tanaka K, et al. Clinical evaluation of a newly developed single-balloon enteroscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1112–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.03.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.May A, Färber M, Aschmoneit I, et al. Prospective multicenter trial comparing push-and-pull enteroscopy with the single- and double-balloon techniques in patients with small-bowel disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:575–581. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domagk D, Mensink P, Aktas H, et al. Single- vs. double-balloon enteroscopy in small-bowel diagnostics: a randomized multicenter trial. Endoscopy. 2011;43:472–476. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takano N, Yamada A, Watabe H, et al. Single-balloon versus double-balloon endoscopy for achieving total enteroscopy: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:734–739. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Efthymiou M, Desmond PV, Brown G, et al. SINGLE-01: a randomized, controlled trial comparing the efficacy and depth of insertion of single- and double-balloon enteroscopy by using a novel method to determine insertion depth. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:972–980. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehdizadeh S, Ross A, Gerson L, et al. What is the learning curve associated with double-balloon enteroscopy? Technical details and early experience in 6 U.S. tertiary care centers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:740–750. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ASGE Technology Committee. Chauhan SS, Manfredi MA, et al. Enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:975–990. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Möschler O, May A, Müller MK, Ell C German DBE Study Group. Complications in and performance of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE): results from a large prospective DBE database in Germany. Endoscopy. 2011;43:484–489. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenz P, Roggel M, Domagk D. Double- vs. single-balloon enteroscopy: single center experience with emphasis on procedural performance. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:1239–1246. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1673-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinho R, Mascarenhas-Saraiva M, Mão-de-Ferro S, et al. Multi-center survey on the use of device-assisted enteroscopy in Portugal. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:264–274. doi: 10.1177/2050640615604775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wadhwa V, Sethi S, Tewani S, et al. A meta-analysis on efficacy and safety: single-balloon vs. double-balloon enteroscopy. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2015;3:148–155. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gov003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipka S, Rabbanifard R, Kumar A, Brady P. Single versus double balloon enteroscopy for small bowel diagnostics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:177–184. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teshima CW, May G. Small bowel enteroscopy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:269–275. doi: 10.1155/2012/571235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.