Abstract

Mimicking biological structures such as fruits and seeds using molecules and molecular assemblies is a great synthetic challenge. Here we report peanut-shaped nanostructures comprising two fullerene molecules fully surrounded by a dumbbell-like polyaromatic shell. The shell derives from a molecular double capsule composed of four W-shaped polyaromatic ligands and three metal ions. Mixing the double capsule with various fullerenes (that is, C60, C70 and Sc3N@C80) gives rise to the artificial peanuts with lengths of ∼3 nm in quantitative yields through the release of the single metal ion. The rational use of both metal–ligand coordination bonds and aromatic–aromatic π-stacking interactions as orthogonal chemical glue is essential for the facile preparation of the multicomponent, biomimetic nanoarchitectures.

The complex, multicomponent structures often found in nature are difficult to mimic synthetically. Here, the authors assemble a molecular analogue of a peanut through coordinative and π-stacking interactions, in which a polyaromatic double capsule ‘pod’ held together by metal ions encapsulates fullerene ‘beans’.

Mimicking the fascinating shapes and functions of biological structures using simple molecules and artificial molecular assemblies is an ongoing challenge for synthetic chemists1. Mechanical bio-motions such as shuttling and rotation have been successfully imitated by interlocked supramolecules and stimuli-responsive molecules2,3,4,5,6,7,8. On the other hand, multilayered, multicomponent bio-structures such as fruits and seeds are so complicated that chemical mimicry of such structures is extremely difficult9,10,11,12. Peanuts are well known and relatively simple seeds comprising a couple of beans fully enclosed by a pod (Fig. 1a)13. There have been several synthetic reports on multicomponent nanostructures with two or three open cavities capable of binding relatively small ions and metal complexes, such as Cl−, PF6− and cisplatin14,15,16,17,18. However, imitation of the characteristic core–shell structures has yet to be accomplished on the nanoscale.

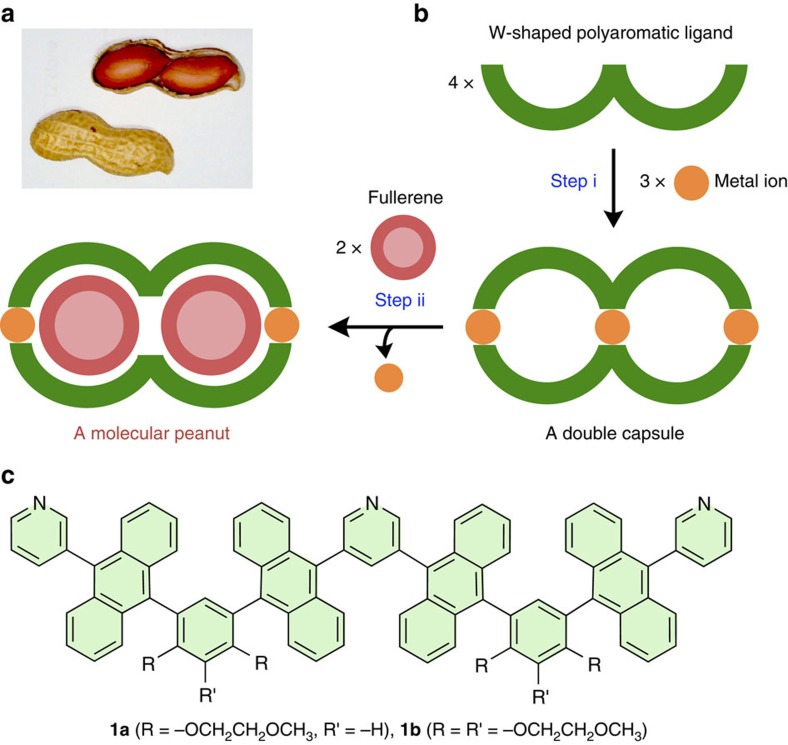

Figure 1. Design and synthetic strategy of a molecular peanut.

(a) Photograph of a peanut. (b) Schematic representation of the stepwise formation of (i) a molecular double capsule from W-shaped polyaromatic ligands and metal ions using coordination bonds and (ii) a molecular peanut from the double capsule and fullerene molecules using π-stacking interactions. (c) W-shaped polyaromatic ligands 1a and 1b designed herein.

Here we report the rational design and facile synthesis of peanut-shaped nanostructures constructed of polyaromatic frameworks. Our synthetic approach to the molecular peanuts is the use of both metal–ligand coordination bonds19,20,21,22 and aromatic–aromatic π-stacking interactions23,24 as orthogonal chemical ‘glue’ to connect multiple molecular components. For the precursor to the dumbbell-shaped polyaromatic ‘pod’, we first design a W-shaped polyaromatic ligand, which binds with metal ions through coordination bonds to form a molecular double capsule with two spherical cavities (Fig. 1b, step i). Next, efficient π-stacking interactions between the two polyaromatic cavities and two spherical fullerene ‘beans’ drive the formation of a molecular peanut (Fig. 1b, step ii). This step is accompanied by the release of the central metal hinge from the double capsule due to steric repulsion. We also report that the two closed cavities of the double capsule encapsulate two different, medium-sized molecules in a heterolytic manner.

Results

Design of a molecular peanut

To construct a peanut-shaped nanostructure, we specifically designed W-shaped tripyridine ligand 1 containing four anthracene rings and two meta-phenylene spacers bearing two or three hydrophilic methoxyethoxy pendants (Fig. 1c), on the basis of our previous synthesis of M2L4 polyaromatic capsules25,26,27,28,29,30. We expected that the W-shaped polyaromatic ligands assemble into an M3L4 double capsule (2) upon complexation with square-planar metal ions. In addition, the double capsule converts to molecular peanut assemblies (G2@3) with lengths of approximately 3 nm upon encapsulation of spherical polyaromatic compounds (that is, G=fullerenes C60 and C70 and metallofullerene Sc3N@C80) through demetallation from the central pyridine rings. The first and second steps occur spontaneously and quantitatively under the control of designed coordinative and π-stacking interactions, respectively. It should be noted that W-shaped ligand 1 exists as a mixture of 10 stereoisomers (see Supplementary Fig. 1) due to restricted rotation about the sterically hindered, pyridyl–anthryl and anthryl–phenyl bonds25,31. Thus double capsule 2 is favoured thermodynamically over possible >103 M3L4 isomers.

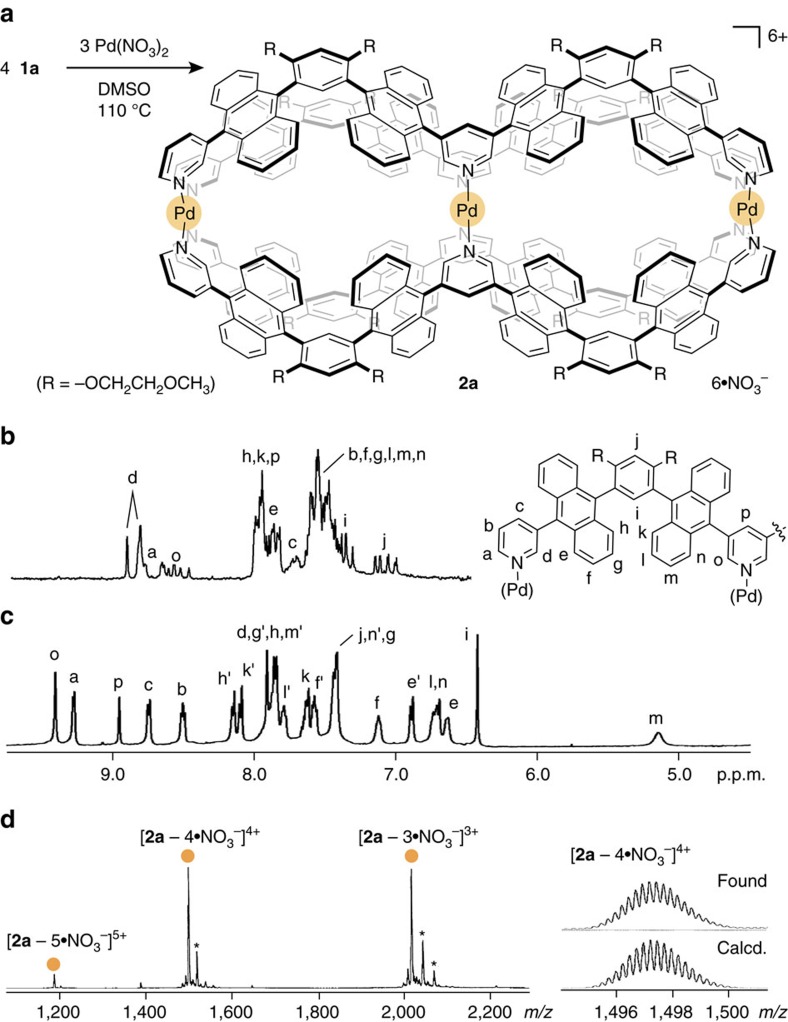

Quantitative formation of double capsules

W-shaped polyaromatic ligand 1a was prepared from a meta-bis(10-bromo-9-anthryl)benzene derivative25 by two-step Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions in 51% yield (see Supplementary Methods). The matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) spectrum showed a single peak at m/z=1,386.2, corresponding to 1a. In contrast, a complicated array of signals was observed in the 1H NMR spectrum (Fig. 2b) due to the presence of numerous stereoisomers of 1a (see Supplementary Fig. 1). The energies of 10 stereoisomers of 1a′ (R=-OCH3) are comparable (ΔE<0.1 kcal mol−1) in the ground state, as indicated by semiempirical calculations. When ligand 1a (1.7 μmol) was combined with Pd(NO3)2 (1.8 μmol) in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)-d6 (0.5 ml) at 110 °C for 12 h, double capsule 2a was formed quantitatively (Fig. 2a). The 1H NMR spectrum of the product exhibited relatively simple signals (Fig. 2c), confirming the conversion of ligand 1a into a highly symmetrical assembly. One set of pyridyl signals Ha,b,c and Ho,p is shifted downfield between 9.36 and 8.47 p.p.m., implying the formation of coordinative pyridyl-Pd(II) bonds. The proton signals of the phenylene moieties (Hi) and the anthracene moieties (Hm) are shifted upfield (Δδ=−0.93 and −2.35 p.p.m., respectively) due to efficient aromatic shielding, which indicates the formation of inner cavities defined by tightly packed polyaromatic frameworks. The electron-spray ionization (ESI)-TOF MS analysis confirmed the formation of M3L4 assembly 2a with a molecular weight of 6231.86 Da. Prominent molecular ion peaks were observed at m/z=1,497.2 and 2,016.9 assignable to the [2a–4·NO3−]4+ and [2a–3·NO3−]3+ species, respectively (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2. Quantitative formation and characterization of a double capsule.

(a) Schematic representation of the formation of double capsule 2a. (b) 1H NMR spectra (500 Hz, DMSO-d6, room temperature) of an isomeric mixture of ligand 1a and (c) double capsule 2a. (d) ESI-TOF MS spectrum (CH3OH) of 2a and the expansion and simulation of the [2a−4·NO3−]4+ signal (the DMSO adducts are marked with asterisks).

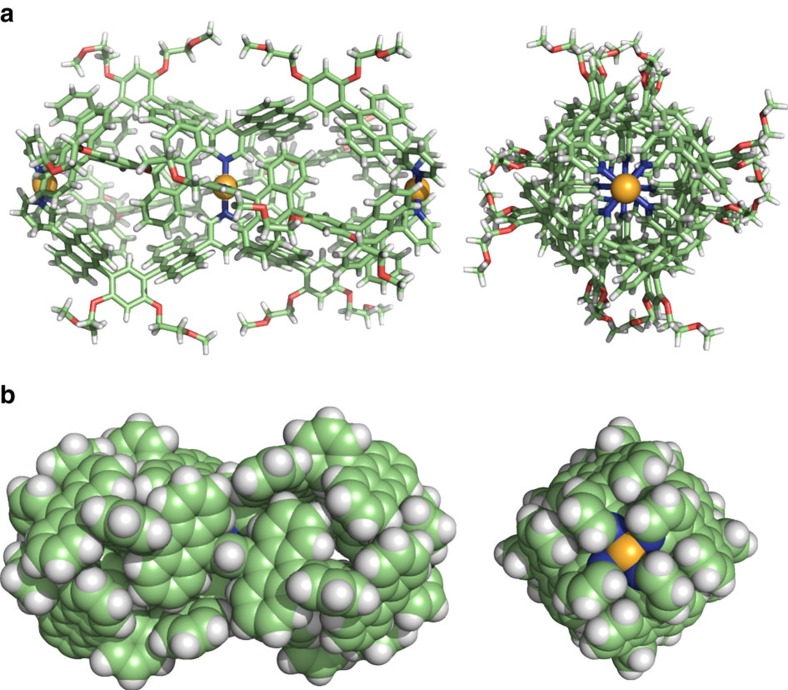

Unambiguous structural evidence of the M3L4 double capsule was provided by single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. Pale yellow crystals suitable for X-ray analysis grew upon slow diffusion of tetrahydrofuran and diethyl ether into a DMSO solution of 2a′ (the BF4− analogue of 2a) at room temperature for 1 week. The molecular structure of the double capsule reveals a 3.2 nm long dumbbell-shaped framework consisting of two polyaromatic spheres linked together (Fig. 3a,b). The shape closely resembles fullerene dimer C120 with a length of 1.6 nm (ref. 32). The distance between the two terminal Pd(II) hinges is 2.8 nm and each of the cavity diameter is ∼1.1 nm. Average dihedral angles between the pyridine rings and the nearby anthracene rings (77.0° and 62.0° at the central and terminal parts, respectively) indicate structural strain around the crowded, central pyridine rings. The structure has two identical cavities with an average volume of 500 Å3, each fully encircled by the eight anthracene panels in a twisted conformation (Fig. 3b). The flexible, 16 methoxyethoxy substituents assist in dissolution of the rigid polyaromatic shell of 2a in polar organic solvents. The solubility could be improved by further attachment of methoxyethoxy groups on the meta-phenylene spacers. Double capsule analogue 2b with 24 methoxyethoxy groups, prepared from ligand 1b (Fig. 1c) and Pd(II) ions (see Supplementary Methods), was soluble in DMSO (>60 mM), CH3CN (>30 mM) and 100:1 H2O/CH3CN (∼30 μM) solutions (see Supplementary Fig. 27).

Figure 3. Crystal structures of double capsule 2a’.

(a) The ball-and-stick representation of double capsule 2a’, which is the BF4 − analogue of 2a, (counterions and solvents are omitted for clarity) and (b) its space-filling representation (the peripheral substituents are replaced by hydrogen atoms).

Quantitative formation of molecular peanuts

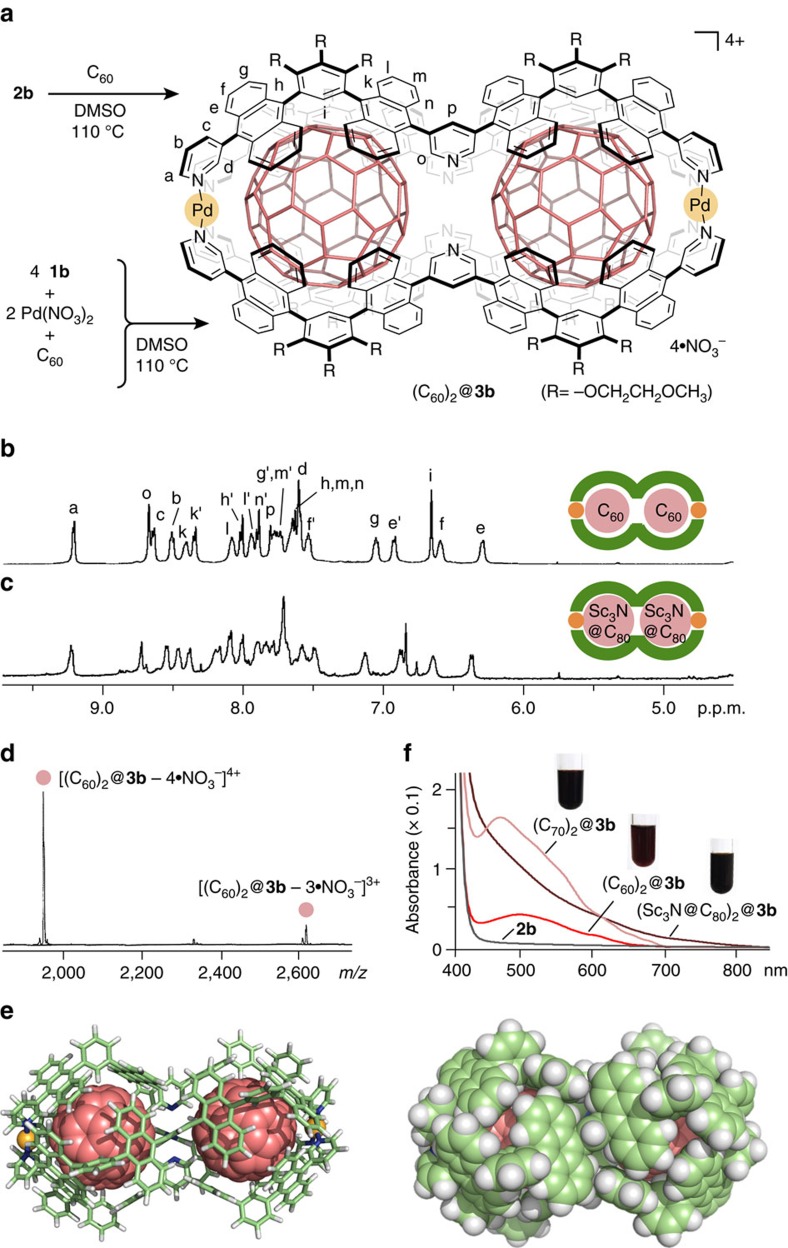

The conversion from double capsule 2b to molecular peanuts occurred quantitatively upon treatment with various fullerenes in hot DMSO solution. For example, when black C60 powder (7.0 equiv. based on 2b) suspended in a DMSO-d6 solution (0.4 ml) of 2b (0.1 μmol) was heated at 110 °C for 1 night, the colour of the solution changed from pale yellow to red, indicating the formation of a (C60)2@3b structure (Fig. 4a). In the 1H NMR spectrum, the aromatic signals of 2b fully converted to a single set of new signals (Fig. 4b). Notably, pyridine signals Ho and Hp were observed at 8.68 and 7.80 p.p.m., respectively, with large upfield shifts (Δδmax=−1.01 p.p.m.) as compared with those of 2b. The shifts suggest the removal of the central Pd(II) ion through the cleavage of the Pd(II)-pyridine coordination bonds. In contrast, the two terminal Pd(II) ions remained bound as indicated by the lack of changes for pyrdine signals Ha–c. The 13C NMR spectrum showed a single prominent signal for C60 at 139.3 p.p.m. (see Supplementary Fig. 36). The upfield shift (Δδ=−3.4 p.p.m.) relative to the carbon signal of free C60 in CDCl3 and the intensity support encapsulated fullerenes. The 1H diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) NMR spectrum showed a single band with a diffusion coefficient (D) of 6.31 × 10−11 m2 s−1 (see Supplementary Fig. 39), which indicates the product size being approximately 3.4 nm (sphere model). The ESI-TOF MS analysis definitely confirmed the M2L4·(C60)2 composition with a molecular weight of 8,041.44 Da. The main peaks at m/z=1,948.1 and 2,618.1 are assignable to [(C60)2@3b – n·NO3−]n+ species (n=4 and 3, respectively) (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4. Quantitative formation and characterization of molecular peanuts.

(a) Schematic representation of the formation of polyaromatic molecular peanut (C60)2@3b. 1H-NMR spectra (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, room temperature) of (b) (C60)2@3b and (c) (Sc3N@C80)2@3b. (d) ESI-TOF MS spectrum (DMSO) of (C60)2@3b. (e) Optimized structures of molecular peanut (C60)2@3b (R=−H; ball-and-stick and space-filling models, the peripheral substituents are replaced by hydrogen atoms for clarity). (f) Ultraviolet–visible spectra and photographs (DMSO, room temperature) of (C60)2@3b, (C70)2@3b, (Sc3N@C80)2@3b and 2b.

The optimized structure of (C60)2@3b (R=−H) by force-field calculations, on the basis of the detailed NMR and MS analyses, shows a peanut-shaped nanostructure (Fig. 4e), where two spherical C60 ‘beans’ (1.0 nm van der Waals diameter) accommodated in the cavity are fully covered with the dumbbell-like polyaromatic ‘pod’ of 3b. The closest distance between the two fullerene guests is 7.1 Å. The fullerenes effectively fill the capsule cavity and form extensive aromatic contacts with 16 anthracene panels of 3b (<3.4 Å). The relatively high stability of (C60)2@3b under high dilution conditions (∼5 μM in DMSO) (see Supplementary Fig. 34e,f) suggests that multiple π-stacking interactions between the host and guests stabilize the complex and most likely play a major role in binding (see Supplementary Fig. 63). Heating is essential for the (C60)2@3b formation. Presumably the elevated temperature helps the dissociation of the central Pd(II) ion, partial or full capsule disassembly and the dissolution of C60 in DMSO. It is noteworthy that molecular peanut (C60)2@3b could also be obtained quantitatively in one step by mixing ligand 1b and Pd(NO3)2 (in a 2:1 ratio) and excess C60 in DMSO at 110 °C for 12 h (Fig. 4a and see Supplementary Fig. 34c,d).

Polyaromatic molecular peanuts possessing higher fullerenes C70 and metallofullerenes Sc3N@C80 were also obtained exclusively by the same one-pot reaction in DMSO. The 1H NMR and ESI-TOF MS analyses provided the structural evidences of 1:2 host–guest complexes (C70)2@3b and (Sc3N@C80)2@3b. For example, the proton NMR pattern of (Sc3N@C80)2@3b is similar to that of (C60)2@3b except for inner phenylene signals Hi at 6.84 p.p.m. (Fig. 4c). The product composition of a 3b·(Sc3N@C80)2 with a large molecular weight (8,819.03 Da) was unequivocally identified by the ESI-TOF MS analysis (see Supplementary Fig. 48). The characteristic absorption bands derived from the accommodated fullerenes in 3b were clearly observed in the ultraviolet–visible spectra (Fig. 4f). The DMSO solutions of (C60)2@3b and (C70)2@3b showed broad absorption bands at λmax=501 and 476 nm, respectively, and that of (Sc3N@C80)2@3b exhibited a shoulder band around 500 nm. In the optimized structure of (Sc3N@C80)2@3b (R=−H), two molecules of the large spherical metallofullerene (1.1 nm van der Waals diameter) are again fully wrapped by the polyaromatic shell (see Supplementary Fig. 61). This intriguing core–shell–shell nanostructure remains intact even after several days under ambient conditions.

Selective formation of a heteroleptic complex

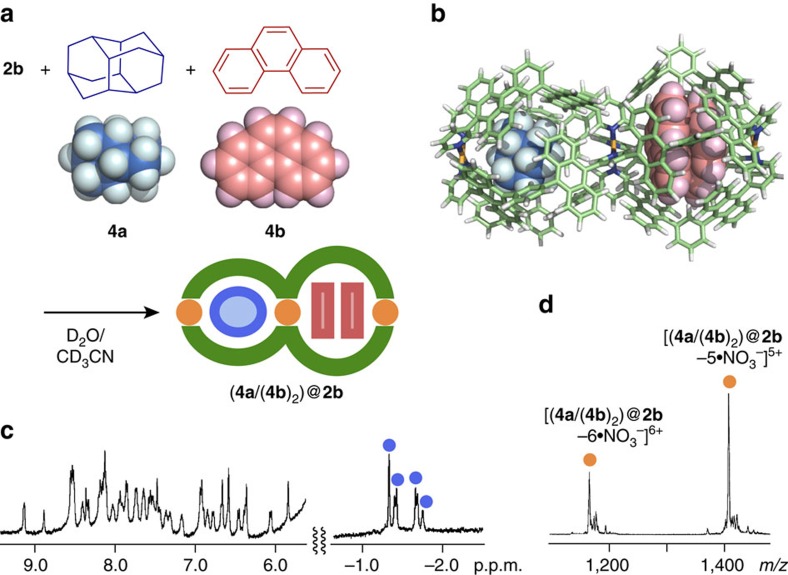

Selective heteroleptic encapsulation of medium-sized, aliphatic and aromatic compounds was observed within double capsule 2b. When excess amounts of hydrophobic diamantane (4a) and phenanthrene (4b) (100 equiv. each based on 2b) were suspended in a 100:1 D2O/CD3CN solution of 2b at 60 °C for 3 h, the two hydrophobic cavities of 2b separately bound one molecule of 4a and two molecules of 4b to generate 1:1:2 host–guest–guest’ complex (4a/(4b)2)@2b in nearly quantitative yield (Fig. 5a,b). The 1H NMR spectrum of the product clearly showed new signals derived from the encapsulated 4a in the range of −1.75 to −1.32 p.p.m. (Fig. 5c). The selective formation of a 2b·4a·(4b)2 composite was confirmed by the ESI-TOF MS spectrum displaying prominent peaks at m/z=1,412.9 and 1,781.6 (Fig. 5d). The NMR and MS spectra of the heteroleptic (4a/(4b)2)@2b complex are quite different from the spectra of homoleptic host–guest complexes (4a/4a)@2b and (4b/(4b)2)@2b, independently prepared from 2b with 4a or 4b, respectively, under similar aqueous conditions (see Supplementary Methods). ESI-TOF MS spectra of (4a/4a)@2b and (4b/(4b)2)@2b showed prominent peaks at, for example, m/z=1,379.3 [(4a/4a)@2b – 5·NO3−]5+ and 1,410.9 [(4b/(4b)2)@2b – 5·NO3−]5+, respectively (see Supplementary Figs 52 and 57).

Figure 5. Selective formation and characterization of a heteroleptic complex.

(a) Schematic representation of the selective formation of heteroleptic host-guest-guest’ complex (4a/(4b)2)@2b and (b) its optimized structure (the peripheral substituents are replaced by hydrogen atoms). (c) 1H NMR (500 MHz, 100:1 D2O/CD3CN, room temperature) and (d) ESI-TOF MS (H2O/CH3CN) spectra of (4a/(4b)2)@2b.

The unusual heteroleptic encapsulation most probably arises from the cooperative changes in volume of the linked cavities upon guest encapsulation, which is mechanistically different from a previous heteroleptic binding in three open cavities with different binding sites18. Optimized host–guest structures of 2b′ (R=−H) using force-field calculations showed that the volume of the second cavity increases by 6% to 530 Å3 upon encapsulation of aliphatic guest 4a (210 Å3) in the first cavity (see Supplementary Fig. 62). Correspondingly, the volume of the second cavity decreases slightly (−4%) upon encapsulation of aromatic guests (4b)2 (total 400 Å3) in the first cavity. This heteroleptic encapsulation is also in sharp contrast to the pairwise encapsulation of two different guests in a single host cavity28,33,34,35,36,37.

Discussion

We have created peanut-shaped polyaromatic nanostructures through stepwise and one-pot multicomponent self-assembly. The structures are composed of a dumbbell-like polyaromatic shell with metal hinges and two spherical polyaromatic molecules, such as fullerene C60 and metallofullerene Sc3N@C80. The unusual core–shell nanostructures, with lengths of approximately 3 nm and molecular weights of up to ∼8,820 Da, quantitatively form through multiple coordination bonds and π-stacking interactions as orthogonal chemical glue. This simple synthetic strategy should provide wide-ranging utilities for the facile preparation of advanced artificial nanoarchitectures inspired by complex natural systems.

Methods

General

NMR: Bruker AVANCE-HD500 (500 MHz), ESI-TOF MS: Bruker micrOTOF II, ultraviolet–visible: JASCO V-670DS, FT-IR: JASCO FT/IR-4200, X-ray: Rigaku XtaLAB Pro P200, Elemental analysis: LECO CHNS-932 VTF-900, Molecular Force-field Calculation: Materials Studio (version 5.5.3, Accelrys Software Inc.). Solvents and reagents: TCI Co., Ltd., Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Kanto Chemical Co., Inc., Sigma-Aldrich Co., and Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. Compounds 6a,b and their precursors (5a,b) (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figs 2–6 and 19–22) were synthesized according to previously reported procedures25,38.

Synthesis of ligand 1a

Compound 6a (0.968 g, 1.32 mmol), 3,5-pyridinediboronic acid bis(pinacol) ester (0.229 g, 0.690 mmol), K3PO4 (1.50 g, 7.07 mmol) and Pd(PPh3)4 (113 mg, 97.4 μmol) were added to a 50 ml glass flask filled with N2. Dry dimethylformamide (30 ml) was added to the flask and then the mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 2 days. The resultant solution was concentrated under reduced pressure. After addition of water, the crude product was extracted with CHCl3. The obtained organic layer was dried over MgSO4, filtrated and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by gel permeation chromatography to afford ligand 1a as a yellow powder (0.467 g, 0.337 mmol, 51% yield) (see Supplementary Figs 7–10b). Ligand 1b was also prepared by the same way (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figs 23–26).

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, room temperature): δ 8.94–8.58 (m, 6H), 8.06–7.29 (m, 39H), 7.18–7.11 (m, 2H), 4.17–4.12 (m, 8H), 3.43–3.32 (m, 8H), 2.99–2.77 (m, 12H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3, room temperature): δ 158.5 (Cq), 152.0 (CH), 151.2 (CH), 149.0 (CH), 142.1 (CH), 139.6 (CH), 137.1 (CH), 135.2 (Cq), 134.8 (Cq), 134.6 (Cq), 132.6 (Cq), 132.3 (Cq), 130.5 (Cq), 130.4 (Cq), 127.5 (CH), 127.4 (CH), 126.4 (CH), 125.8 (CH), 125.6 (CH), 125.2 (CH), 123.5 (CH), 120.5 (CH), 100.2 (CH), 71.0 (CH2), 69.3 (CH2), 59.1 (CH3). FT-IR (KBr, cm−1): 3,022; 2,926; 2,877; 2,819; 1,505; 1,484; 1,377; 1,313; 1,265; 1,191; 1,170; 1,152; 1,128; 1,103; 1,025; 766, 688, 609. MALDI-TOF MS (dithranol): m/z Calcd. for C95H75N3O8: 1,386.56, Found 1,386.24 [M]+. HR MS (ESI, CH2Cl2/CH3OH): m/z Calcd. for C95H75N3O8: 1,387.5660, Found 1,387.5662 [M+H]+.

Formation of double capsule 2a

W-shaped ligand 1a (2.4 mg, 1.7 μmol), a DMSO-d6 solution (25 mM) of Pd(NO3)2 (70 μl, 1.8 μmol), which prepared in situ from PdCl2(DMSO)2 and AgNO3, and DMSO-d6 (0.5 ml) were added to a glass test tube and then the mixture was stirred at 110 °C for 12 h. The quantitative formation of double capsule 2a was confirmed by NMR, MS and X-ray crystallographic analyses (see Supplementary Figs 11–18). The diffusion coefficient (D) of 2a in DMSO-d6 was estimated to be 6.31 × 10−11 by the 1H DOSY NMR analysis, which indicates the formation of a 3.4 nm-sized structure (sphere model). Double capsule 2a′, which is a BF4− analogue of 2a, was also obtained by using Pd(BF4)2 (see Supplementary Fig. 11b). The single crystals for X-ray crystallographic analysis were obtained by slow diffusion of tetrahydrofuran and diethyl ether into a DMSO solution of 2a′ at room temperature for a week (see Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 60). Double capsule 2b was prepared by the same way (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figs 27–33).

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, room temperature): δ 9.36 (s, 2H), 9.24 (d, J=5.5 Hz, 2H), 8.92 (s, 1H), 8.71 (d, J=7.5 Hz, 2H), 8.47 (dd, J=7.5, 5.5 Hz, 2H), 8.12 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 2H), 8.06 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.88 (s, 2H), 7.83–7.76 (m, 8H), 7.63–7.53 (m, 4H), 7.41–7.39 (m, 6H), 7.10 (br, 2H), 6.87 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.72-6.67 (m, 4H), 6.61 (br, 2H), 6.41 (s, 2H), 5.19 (br, 2H), 4.37–4.18 (m, 8H), 4.36–3.14 (m, 8H), 2.99–2.76 (m, 12H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, room temperature): δ 158.3 (Cq), 158.0 (Cq), 152.7 (CH), 152.3 (CH), 151.0 (CH), 147.4 (CH), 144.2 (CH), 139.0 (Cq), 136.6 (Cq), 136.1 (Cq), 135.5 (CH), 135.3 (Cq), 132.1 (Cq), 131.6 (CH), 131.5 (Cq), 129.6–123.9, 117.9 (Cq), 117.7 (Cq), 99.8 (CH), 70.2 (CH2), 70.0 (CH2), 68.2 (CH2), 67.9 (CH2), 58.0 (CH3). DOSY NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K): D=6.31 × 10−11 m2 s−1. FT-IR (KBr, cm−1): 3,061; 2,926; 2,880; 2,817; 1,602; 1,504; 1,440; 1,379; 1,315; 1,267; 1,192; 1,126; 1,104; 1,028; 944, 769, 687. ESI-TOF MS (CH3CN): m/z 1,185.4 [2a – 5·NO3−]5+, 1,497.2 [2a – 4·NO3−]4+, 2,016.9 [2a – 3·NO3−]3+.

X-ray crystal data of 2a’

C380H300BF4N12O32Pd3, Mr=5,952.61, tetragonal, P4/ncc, a=b=26.5390(8) Å, c=71.806(7) Å, V=50,574(5) Å3, Z=4, ρcalcd=0.782 g cm−3, F(000)=12,396, T=93 K, reflections collected/unique 152,900/25,558 (Rint=0.0690), R1=0.1060 (I>2σ(I)), wR2=0.3855, GOF=1.204. All the diffraction data were collected on a diffractometer (λ(CuKα)=1.54187 Å). The contribution of the electron density associated with greatly disordered counterions and solvent molecules, which could not be modelled with discrete atomic positions, were handled using the SQUEEZE routine in PLATON.

Formation of molecular peanut (C60)2@3b

Route 1: Double capsule 2b (0.7 mg, 0.1 μmol), fullerene C60 (0.5 mg, 0.7 μmol) and DMSO-d6 (0.4 ml) were added to a glass test tube and then the mixture was stirred at 110 °C for 12 h. The quantitative formation of (C60)2@3b was confirmed by NMR, MS and ultraviolet–visible analyses. Route 2: A DMSO-d6 solution (50 mM) of Pd(NO3)2 (42 μl, 2.1 μmol), ligand 1b (6.0 mg, 3.9 μmol), fullerene C60 (3.0 mg, 4.2 μmol) and DMSO-d6 (0.5 ml) were added to a glass test tube and then the mixture was stirred at 110 °C for 6 h. The quantitative formation of (C60)2@3b was confirmed by NMR, MS and ultraviolet–visible analyses (see Supplementary Figs 34,36–40a and 49). Host–guest complexes (C60)2@3a, (C70)2@3b and (Sc3N@C80)2@3b were obtained quantitatively by the same way (see Supplementary Figs 35 and 40b–49).

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, room temperature): δ 9.21 (d, J=6.0 Hz, 2H), 8.68 (s, 2H), 8.64 (d, J=6.5 Hz, 2H), 8.51 (dd, J=6.5, 6.0 Hz, 2H), 8.41 (br, 2H), 8.35 (d, J=8.0 Hz, 2H), 8.09 (br, 2H), 8.02 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.95 (br, 2H), 7.90 (d, J=9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.81–7.73 (m, 5H), 7.65–7.59 (m, 8H), 7.54 (br, 2H), 7.06 (br, 2H), 6.93 (d, J=7.5 Hz, 2H), 6.66 (s, 2H), 6.60 (br, 2H), 6.30 (d, J=7.0 Hz, 2H), 4.41–4.31 (m, 4H), 4.00–3.90 (m, 4H), 3.85–3.79 (m, 4H), 3.74 (t, J=4.5 Hz, 4H), 3.33 (s, 6H), 3.08 (t, J=5.0 Hz, 4H), 2.87 (t, J=4.0 Hz, 4H), 2.69 (s, 6H), 2.55 (s, 6H). ESI-TOF MS (CH3CN) of (C60)2@3b: m/z 1,948.1 [(C60)2@3b – 4·NO3−]4+, 2,618.1 [(C60)2@3b – 3·NO3−]3+.

Formation of heteroleptic complex (4a/(4b)2)@2b

Diamantane (4a; 0.7 mg, 3.7 μmol) and phenanthrene (4b; 0.5 mg, 2.8 μmol) were added to a 100:1 D2O:CD3CN solution (0.6 ml) of double capsule 2b (1.7 mg, 0.22 μmol) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The quantitative formation of a (4a/(4b)2)@2b complex was confirmed by NMR and ESI-TOF MS analyses (see Supplementary Figs 58,59 and 62).

ESI-TOF MS (H2O:CH3CN=100:1): m/z 1,166.9 [(4a/(4b)2)@2b –6·NO3−]6+, 1,412.9 [(4a/(4b)2)@2b – 5·NO3−]5+, 1,781.6 [(4a/(4b)2)@2b–4·NO3−]4+, 2,396.1 [(4a/(4b)2)@2b – 3·NO3−]3+.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the Supplementary Information files and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. CCDC-529139 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for the structure reported in this article. The data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Yazaki, K. et al. Polyaromatic molecular peanuts. Nat. Commun. 8, 15914 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15914 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant No. JP25104011/JP26288033/JP17H05359), SERB, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India (Project No. SB/S1/IC-05/2014) and ‘Support for Tokyotech Advanced Researchers (STAR)’. K.Y. and S.P. thank the JSPS and CSIR, India, respectively, for a Research Fellowship. We thank Tokyo Tech and IIT Madras for encouragement through MoU.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions K.Y., D.K.C. and M.Y. designed the work, carried out research, analysed data and wrote the paper. M.A. and S.P. were involved in the work discussion. T.K. and H.S. contributed to crystallographic analysis. M.Y. is the principal investigator. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

References

- Kinbara K. & Aida T. Toward intelligent molecular machines: directed motions of biological and artificial molecules and assemblies. Chem. Rev. 105, 1377–1400 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkai S., Nakaji T., Ogawa T., Shigematsu K. & Manabe O. Photoresponsive crown ethers. 2. Photocontrol of ion extraction and ion transport by a bis(crown ether) with a butterfly-like motion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103, 111–115 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Bissell A., Córdova E., Kaifer A. E. & Stoddart J. F. A chemically and electrochemically switchable molecular shuttle. Nature 369, 133–137 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Kelly T. R., De Silva H. & Silva R. A. Unidirectional rotary motion in a molecular system. Nature 401, 150–152 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koumura N., Zijlstra R. W. J., Van Delden R. A., Harada N. & Feringa B. L. Light-driven monodirectional molecular rotor. Nature 401, 152–155 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez M. C., Dietrich-Buchecker C. & Sauvage J.-P. Towards synthetic molecular muscles: contraction and stretching of a linear rotaxane dimer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 3284–3287 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh D. A., Wong J. K. Y., Dehez F. & Zerbetto F. Unidirectional rotation in a mechanically interlocked molecular rotor. Nature 424, 174–179 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Molero M. C., Dietrich-Buchecker C. & Sauvage J.-P. Towards artificial muscles at the nanometric level. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 1613–1616 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima S. Direct observation of the tetrahedral bonding in graphitized carbon black by high resolution electron microscopy. J. Cryst. Growth 50, 675–683 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Kroto H. W. Carbon onions introduce new flavour to fullerene studies. Nature 359, 670–671 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. W., Monthioux M. & Luzzi D. E. Encapsulated C60 in carbon nanotubes. Nature 396, 323–324 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Hirahara K. et al. One-dimensional metallofullerene crystal generated inside single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 5384–5387 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalker T. & Wilson R. F. (eds). Peanuts: Genetics, Processing, and Utilization Academic Press and AOCS Press (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Baxter P. N. W., Lehn J.-M., Kneisel B. O., Baum G. & Fenske D. The designed self-assembly of multicomponent and multicompartmental cylindrical nanoarchitectures. Chem. Eur. J. 5, 113–120 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Bandi S., Pal A. K., Hanan G. S. & Chand D. K. Stoichiometrically controlled revocable self-assembled ‘spiro’ versus quadruple-stranded ‘double-decker’ type coordination cages. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 13122–13126 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone M. D., Schwarze E. K., Clever G. H. & Pfeffer F. M. Modular synthesis of linear bis- and tris-monodentate fused [6]polynorbornane-based ligands and their assembly into coordination cages. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 3948–3955 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandi S. et al. Double-decker coordination cages. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2816–2827 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Preston D., Lewis J. E. M. & Crowley J. D. Multicavity [PdnL4]2n+ cages with controlled segregated binding of different guests. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 2379–2386 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smulders M. M. J., Riddell I. A., Browne C. & Nitschke J. R. Building on architectural principles for three-dimensional metallosupramolecular construction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 1728–1754 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook T. R. & Stang P. J. Recent developments in the preparation and chemistry of metallacycles and metallacages via coordination. Chem. Rev. 115, 7001–7045 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Wang Y.-X. & Yang H.-B. Supramolecular transformations within discrete coordination-driven supramolecular architectures. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 2656–2693 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita D. et al. Self-assembly of tetravalent Goldberg polyhedra from 144 small components. Nature 540, 563–566 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter C. A., Lawson K. R., Perkins J. & Urch C. J. Aromatic interactions. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 651–669 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Klosterman J. K., Yamauchi Y. & Fujita M. Engineering discrete stacks of aromatic molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1714–1725 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi N., Li Z., Yoza K., Akita M. & Yoshizawa M. An M2L4 molecular capsule with an anthracene shell: encapsulation of large guests up to 1 nm. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11438–11441 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Kishi N., Yoza K., Akita M. & Yoshizawa M. Isostructural M2L4 molecular capsules with anthracene shells: synthesis, crystal structures, and fluorescent properties. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 8358–8365 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashina M., Sei Y., Akita M. & Yoshizawa M. Safe storage of radical initiators within a polyaromatic nanocapsule. Nat. Commun. 5, 4662 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashina M. et al. Preparation of highly fluorescent host-guest complexes with tunable color upon encapsulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 9266–9269 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K. et al. An M2L4 molecular capsule with a redox switchable polyradical shell. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 15031–15034 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa M. & Yamashina M. Coordination-driven nanostructures with polyaromatic shells. Chem. Lett. 46, 163–171 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- Bringmann G. et al. Atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral biaryl compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 5384–5427 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.-W., Komatsu K., Murata Y. & Shiro M. Synthesis and X-ray structure of dumb-bell-shaped C120. Nature 387, 583–586 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Heinz T., Rudkevich D. M. & Rebek J. Jr Pairwise selection of guests in a cylindrical molecular capsule of nanometre dimensions. Nature 394, 764–766 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-J. et al. Selective inclusion of a hetero-guest pair in a molecular host: formation of stable charge-transfer complexes in cucurbit[8]uril. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40, 1526–1529 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa M., Tamura M. & Fujita M. AND/OR bimolecular recognition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 6846–6847 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa M., Tamura M. & Fujita M. Diels-Alder in aqueous molecular hosts: unusual regioselectivity and efficient catalysis. Science 312, 251–254 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada T., Yoshizawa M., Sato S. & Fujita M. Minimal nucleotide duplex formation in water through enclathration in self-assembled hosts. Nat. Chem. 1, 53–56 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi N. et al. Facile catch and release of fullerenes using a photoresponsive molecular tube. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 12976–12979 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the Supplementary Information files and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. CCDC-529139 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for the structure reported in this article. The data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.