Abstract

Parkinson’s disease has long been associated with redox imbalance and oxidative stress in dopaminergic neurons. The catecholaldehyde hypothesis proposes that 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL), an obligate product of dopamine catabolism, is a central nexus in a network of pathways leading to disease-state neurodegeneration, owing to its toxicity and potent ability to oligomerize α-synuclein, the main component of protein aggregates in Lewy bodies. In this work we examine the connection between reactive oxygen species and DOPAL autoxidation. We show that superoxide propagates a chain reaction oxidation, and that this reaction is dramatically inhibited by superoxide dismutase. Moreover, superoxide dismutase prevents DOPAL from forming dicatechol pyrrole adducts with lysine and from covalently crosslinking α-synuclein. Given that superoxide is a major radical byproduct of impaired cellular respiration, our results provide a possible mechanistic link between mitochondrial dysfunction and synuclein aggregation in dopaminergic neurons.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, amyloid disease, oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species, covalent crosslinking, mitochondrial impairment

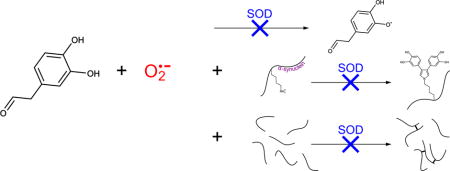

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is an incurable neurological disorder that affects the motor system and is associated with both environmental and genetic risk factors. Its symptoms are caused by the selective loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra region of the brain. A second, well-established pathological characteristic is the appearance in those neurons of Lewy bodies, proteinaceous aggregates that contain large amounts of the 140-residue, intrinsically disordered protein α-synuclein. Genetic mutations of α-synuclein also lead to early-onset forms of the disease, and these two involvements in PD have prompted extensive research into its physiological role and biophysical properties [1]. The triggers of its aggregation in the disease state remain unclear, but an emerging understanding is that while the protein forms large amyloid fibrils in vitro, small oligomers may be the more toxic and etiologically relevant species [2].

According to the catecholaldehyde hypothesis, the preferential susceptibility of dopaminergic neurons in PD is the result of the misregulation of pathways that lead to aberrant levels of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde [3]. 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL) is an obligate intermediate in dopamine catabolism – the product of monoamine oxidase, which converts the amine group of dopamine to an aldehyde – that helps end synaptic transmission and, along with neuromelanin synthesis [4], prevents potential oxidative stress caused by the accumulation of cytosolic dopamine [5]. DOPAL is far more chemically reactive than dopamine or its other metabolites, owing to its aldehyde group [6, 7]. Aldehydes are known to form adducts with nucleophilic groups in proteins and nucleic acids, and those adducts have been associated with several diseases [8]. In the case of DOPAL, the catechol group also contributes to the reactivity of the aldehyde [6, 9]. This peculiar property suggests that oxidation of the DOPAL catechol group to a semiquinone (loss of a single electron) or quinone (loss of two electrons) activates its aldehyde’s reactivity [9, 10]. The catecholaldehyde hypothesis is supported by the fact that DOPAL is highly toxic in vivo and in cultured neurons and leads to the loss of dopaminergic neurons when injected into the substantia nigra of rats [11–13]. DOPAL’s neuronal toxicity is accompanied by the accumulation of oligomeric forms of α-synuclein, and DOPAL also potently crosslinks α-synuclein in vitro [13–15].

Like many other neurodegenerative disorders, PD is primarily a disease of senescence, suggesting that its progression is caused or exacerbated by the accumulation of oxidative stress [16]. This idea has been bolstered by the finding that small molecule inhibitors of complex I of the electron transport chain in mitochondria replicate the pathological hallmarks of PD in animals and humans [17–20]. Impaired respiration leads to the production of the superoxide anion, a reactive oxygen species (ROS) resulting from a single electron reduction of molecular oxygen. The brain is particularly susceptible to oxidative stress, owing to its high resting rate of oxygen consumption and large amounts of iron and polyunsaturated fatty acids [16]. Cellular defense against ROS includes superoxide dismutase (SOD), a metalloenzyme that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide to either molecular oxygen or hydrogen peroxide, which cycle in concert with the oxidation state of its bound metal [21].

In the early 1970’s, it was discovered that SOD inhibits the in vitro autoxidation of the catecholamine neurotransmitter epinephrine and the synthetic neurotoxin oxidopamine, also known as 6-hydroxydopamine [22, 23]. This is attributable to the role of superoxide as a propagating species in a chain reaction that efficiently oxidizes the hydroxylated rings to semiquinones and quinones, whereas the initiating event, oxidation of the rings by molecular oxygen, occurs only slowly. In the presence of SOD, superoxide is produced from molecular oxygen by the initiating oxidation reaction, but is cleared by enzymatic dismutation and thus unable to further contribute to the reaction [22, 23]. Remarkably, acceleration of oxidative decay by SOD was observed for the catecholaldehyde DOPAL [9]. In this study, we report that SOD acts as a potent enzymatic antioxidant for the catecholaldehyde when used at catalytic submicromolar concentrations, protecting against the production of dicatechol pyrrole lysine in reactions with DOPAL and lysine, and preventing the formation of DOPAL-mediated covalent oligomers of α-synuclein.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. DOPAL autoxidation

DOPAL was purchased from VDM Biochemicals and stocks were prepared in deuterated methanol and quantified as described previously [10]. Autoxidation studies were performed at 37 °C in phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.4 (PBS, KD Medical) with 100 μM DOPAL, 100 μM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA, Sigma-Aldrich) to chelate any contaminating metals – including adventitious copper that is known to be present in SOD preparations [24] – and 10% D2O. Spectra were collected on a 600 MHz Bruker Avance III spectrometer. Each 1D 1H NMR spectrum was collected with 292 scans, a signal acquisition time of 2.0 seconds, and a 9.97 second recycle delay, for a total data collection time of 1 hour.

Stocks of SOD1 from bovine erythrocytes (Sigma-Aldrich, product #: S7571) were prepared in PBS at 0.5 mg/ml, which corresponds to 15.4 μM of the active, dimeric form of the enzyme, and diluted to a working concentration of 50 nM in the reactions. Control reactions with inactivated SOD were heated at 95 °C for 5 minutes, then cooled to 37 °C prior to addition of DOPAL. Stocks of catalase (Sigma-Aldrich, product #: C9322) were prepared in PBS at 1 mg/ml, or 4.0 μM of the active, tetrameric enzyme, and diluted to a working concentration of 50 nM. Hydrogen peroxide was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (product #: 88597).

Assays with variable SOD concentrations replicated the conditions of Anderson et al [9]. Samples were prepared with 500 μM DOPAL in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.8 with 100 μM DTPA, and samples for NMR included 10% D2O. Stocks of SOD1 were prepared in this same buffer at a concentration of 5 mg/ml (154 μM) and diluted to the indicated working concentrations. Absorbance at 400 nm was monitored on a Cary 8454 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent) with the sample temperature maintained at 37 °C in a Peltier cell. Samples were blanked immediately prior to DOPAL addition, and spectra were recorded at three minute intervals without baseline correction. NMR data collection and DOPAL quantification was performed as described above for samples in PBS.

2.2. Lysyl adduct formation

Reactions with 2 mM DOPAL, 1.5 mM Nα-acetylated lysine (Sigma-Aldrich), and 100 μM DTPA were set up in PBS with 10% D2O and incubated at 37 °C in a 500 MHz Bruker Avance III spectrometer. A 4 hour time course was measured by collecting 1D 1H spectra with 142 scans, a signal acquisition time of 2.0 seconds, and a recycle delay of 3.97 seconds (15 minutes per spectrum). Dicatechol pyrrole lysine concentrations were calculated by integration of the well-resolved acetyl methyl signal and assigned to the midpoint of each measurement time [10]. Stocks of SOD1 from bovine erythrocytes were prepared at 5 mg/ml in PBS and diluted to a working concentration of 0.5 μM in the reactions. SOD was inactivated by heat treatment at 95 °C for 5 minutes prior to the addition of DOPAL. For reactions performed with ascorbate (Sigma-Aldrich) and 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (Sigma-Aldrich), stocks were made in PBS at concentrations of 100 mM and 1 M, respectively, and diluted to 10 mM in the assay.

2.3. Protein crosslinking

N-terminally acetylated wild-type α-synuclein (Ac-WT aS) was obtained by bacterial co-expression of a codon-optimized synuclein construct and the NatB acetyltransferase [25, 26]. The protein was expressed and purified as described previously [10]. Reactions contained 2 mM DOPAL, 100 μM Ac-WT aS, and 100 μM DTPA in PBS, and SOD was added at a 0.5 μM working concentration. The reactions were incubated at 37 °C in the dark, and aliquots were drawn at the indicated times and subjected to SDS-PAGE on 1.5 mm NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen). Gels were stained with InstantBlue (Expedeon) and protein bands were detected at 700 nm on an Odyssey scanner (LI-COR Biosciences).

3. Results

3.1. Superoxide stimulates DOPAL autoxidation

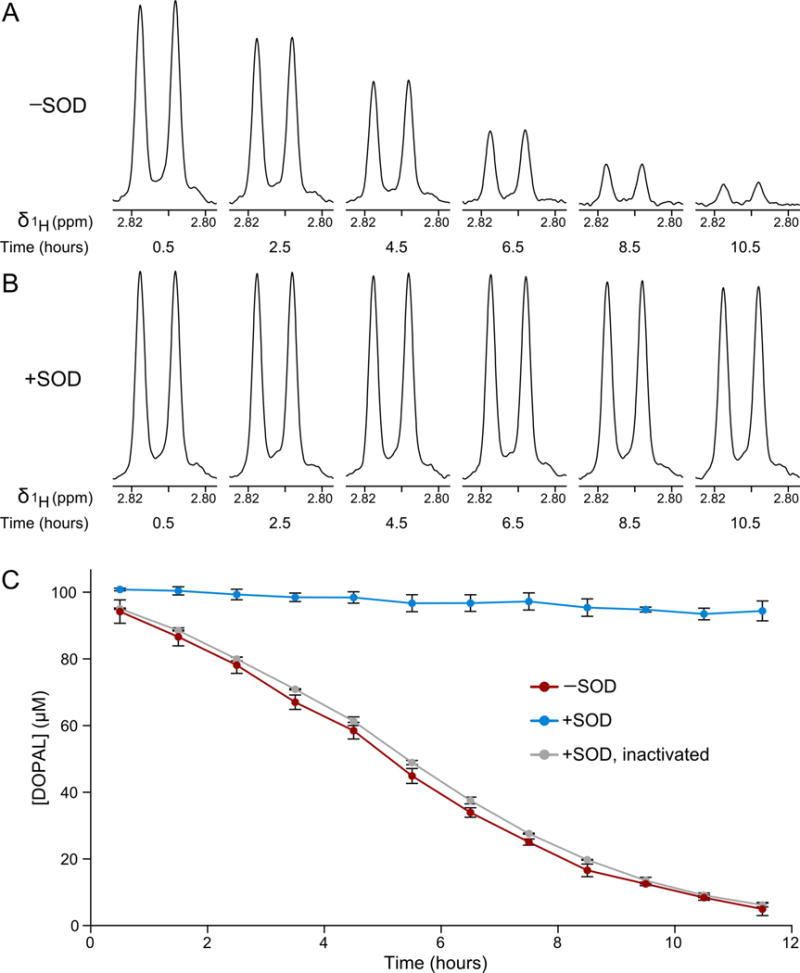

To study its autoxidation, we incubated samples of 100 μM DOPAL in PBS and followed the loss of its proton signals by 1D 1H NMR (Figure 1A). In aqueous solution, DOPAL exists in an equilibrium between the aldehyde and a hydrated, gem-diol form, with relative populations of 30% and 70%, respectively [9]. Figure 1A illustrates the major, gem-diol signal for the DOPAL alpha protons. DOPAL is progressively oxidized over the course of the incubation, and almost entirely degraded after 12 hours.

Figure 1.

Superoxide dismutase inhibits DOPAL autoxidation. (A) The loss of DOPAL by autoxidation in H2O PBS was followed in 1D 1H NMR spectra. In (A) and (B), the alpha proton signals of the major, gemdiol form of DOPAL are shown. (B) The same DOPAL signal was monitored with SOD present. (C) DOPAL concentrations were calculated based on integrated signal intensities of the alpha proton in reactions with DOPAL alone (red), with SOD (blue), and with SOD inactivated by heat treatment (gray). Reactions were performed in triplicate and error bars represent standard deviations.

The DOPAL concentrations, determined by integration of the NMR signals, are plotted versus time in Figure 1C. Integrals were calculated using the sum of the gem-diol and aldehyde signal intensities for the alpha protons at each time point. The alpha proton signal was found to provide a more useful measure of the DOPAL concentration than its aromatic signals, as the aromatic region of the 1D 1H NMR spectrum becomes contaminated by heterogeneous breakdown products over the course of the incubation. The integrated intensities of the alpha protons were referenced to a spectrum of 100 μM DOPAL in identical buffer that was thoroughly degassed by sonication under vacuum and the head space of its NMR tube flushed with nitrogen gas prior to acquisition in order to prevent oxidation, and the calculated DOPAL concentrations were assigned to the midpoint of each measurement time.

The effect of SOD on DOPAL autoxidation was tested by adding 50 nM of SOD1, the cytosolic form of the enzyme, from bovine erythrocytes. In contrast to the first reaction, DOPAL was very stable with SOD present, with less than 10% lost in 12 hours (Figure 1B). Comparison of the initial rates of decay in the two reactions shows that SOD inhibits the DOPAL autoxidation rate by 94%, similar to the 91% and 93% inhibition observed for epinephrine and 6-hydroxydopamine, respectively [22, 23]. To verify that the inhibition of DOPAL autoxidation results from the enzymatic activity of SOD, we ran a control reaction that was heated at 95 °C for 5 minutes in order to inactivate the SOD, then cooled back to 37 °C prior to addition of DOPAL. In this case, the autoxidation mirrored the reaction without SOD (Figure 1C).

The dismutation of superoxide produces hydrogen peroxide, another reactive oxygen species that may contribute to DOPAL degradation. To assess its contribution, we tested samples with 50 nM catalase, which catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water and molecular oxygen. Unlike SOD, catalase failed to slow DOPAL autoxidation (Figure S1 in the Supplementary Material). We next tested the effect of directly adding 100 μM hydrogen peroxide to the DOPAL sample. Again, there was no significant impact on the DOPAL autoxidation (Figure S1).

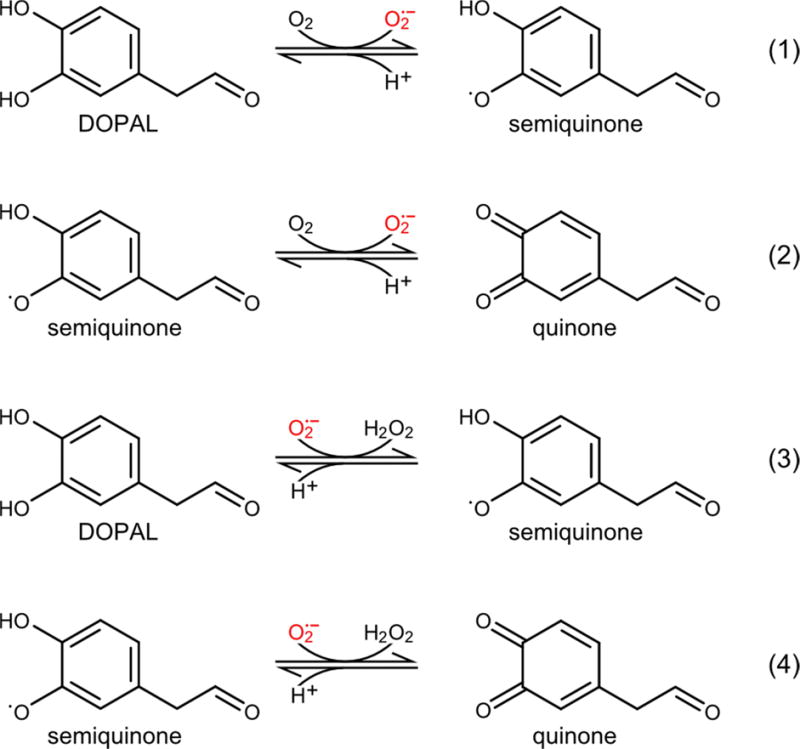

The powerful inhibitory effect of SOD on DOPAL autoxidation can be explained by the reactions in Figure 2, which are analogous to those previously proposed for epinephrine and 6-hydroxydopamine [22, 23]. In reactions 1 and 2, DOPAL is converted first to a semiquinone radical and then to a quinone, in two single-electron oxidations performed by molecular oxygen. In reactions 3 and 4, these same oxidations are carried out by the superoxide radical, which is produced in reactions 1 and 2. In the presence of SOD, this superoxide is efficiently dismutated to hydrogen peroxide and molecular oxygen, such that reactions 3 and 4 do not significantly contribute to DOPAL degradation. The residual, very slow decay of DOPAL in the presence of SOD may approximate the initiating step of oxidation by molecular oxygen in reaction 1. In the absence of SOD, reactions 2 and 3 constitute the propagation steps of a superoxide-mediated chain reaction that leads to the rapid decomposition of the catecholaldehyde.

Figure 2.

Reaction scheme for the oxidative decomposition of DOPAL. In reaction 1, DOPAL is oxidized by molecular oxygen to produce semiquinone and superoxide radicals. In reaction 2, the DOPAL semiquinone is oxidized again to a quinone and a second superoxide radical. In reactions 3 and 4, these same DOPAL oxidations are catalyzed by the superoxide radical. Reactions 3 and 4 are suppressed by SOD, which dismutates the superoxide produced in reactions 1 and 2. Reactions 2 and 3 comprise the propagation steps of a chain reaction in which the superoxide radical catalyzes the oxidative degradation of DOPAL.

3.2. SOD prevents DOPAL from forming lysyl adducts

DOPAL forms adducts with proteins by reacting with the terminal sidechain amine groups of lysine residues [6, 10, 27]. Recently, we quantitatively characterized the adducts formed in reactions between DOPAL and either N-terminally acetylated, wild-type α-synuclein (Ac-WT aS) or Nα-acetylated lysine (Ac-Lys). Under physiological conditions in reactions monitored by NMR and LC-MS, the predominant product was a dicatechol pyrrole lysine (DCPL), formed by two DOPAL molecules reacting with the lysine sidechain amine through their aldehyde moieties [10]. A surprising feature of this adduct is its pyrrole ring, which contains the lysine Nε and the carbons of the two DOPAL alkyl chains, and requires the formation of a carbon-carbon bond between the aldehyde-adjacent DOPAL carbons.

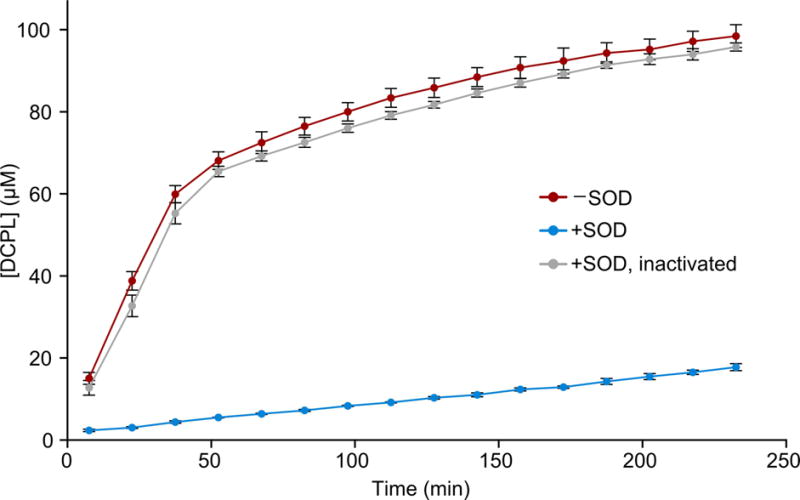

To determine how superoxide-mediated autoxidation affects DOPAL reactivity, we followed the production of DCPL in reactions with 2 mM DOPAL and 1.5 mM Ac-Lys in PBS at 37 °C by 1D 1H NMR (Figure 3). Without SOD, DCPL is formed at a fast and linear initial rate, followed by a plateauing at later time points, as observed previously [10]. The addition of SOD dramatically reduces the rate of DCPL formation, and this effect is again reversed by inactivation of the SOD by heat treatment. Comparing the initial, linear rates of product formation in the reactions with and without SOD shows that the enzyme inhibits DCPL production by 95%, very close to the value observed for the SOD-based inhibition of DOPAL autoxidation (94%). DCPL formation is also inhibited by addition of the radical scavenger ascorbate (Figure S2 in the Supplementary Material), whereas 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO), which has a rate constant toward superoxide that is ~107 times lower than ascorbate [28, 29], has no effect (Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Superoxide dismutase slows dicatechol pyrrole lysine formation. The DCPL concentration was followed by integrated signal intensities in 1D 1H NMR spectra for reactions between Ac-Lys and DOPAL alone (red), with SOD (blue), and with SOD inactivated by heat treatment (gray). Concentrations are averaged over three independent replicates with error bars representing standard deviations.

3.3. SOD inhibits DOPAL-mediated α-synuclein crosslinking in vitro

DOPAL covalently crosslinks α-synuclein in vitro and in neuronal cells, and this capability underlies its central role in the catecholaldehyde hypothesis for PD neurodegeneration [3]. We next assessed the impact of SOD on this crosslinking by setting up reactions with 2 mM DOPAL and 100 μM Ac-WT aS in PBS at 37 °C and following oligomer formation by SDS-PAGE (Figure 4). In the absence of SOD, robust formation of protein oligomers was observed over the course of 4 hours (Figure 4A). In contrast, addition of 0.5 μM SOD nearly completely prevented oligomer formation (Figure 4A). Again, heat treatment of the reaction prior to DOPAL addition reversed the effect, implicating the SOD enzymatic activity as the inhibitory agent (Figure 4B). Disulfide formation does not contribute to DOPAL-induced crosslinking of α-synuclein, as the protein does not contain cysteine.

Figure 4.

Superoxide dismutase inhibits DOPAL-mediated α-synuclein crosslinking. (A) DOPAL was incubated with N-terminally acetylated α-synuclein and the formation of covalent oligomers was monitored by SDS-PAGE. Addition of SOD drastically reduced crosslinking. (B) The reactions in (A) were repeated but with the SOD inactivated by heating, which restored the crosslinking potency of DOPAL.

3.4. DOPAL oxidation at high SOD concentrations

A prior study reported that high concentrations of SOD stimulated DOPAL oxidation [9], as measured by the absorbance of light at 400 nm. We were able to replicate these observations (Figure S3A in the Supplementary Material); however, we also found that the UV-Vis spectra were extensively impacted by light scattering (Figure S3B), which hindered further analysis. Instead, we again tracked the decay of DOPAL by 1D 1H NMR spectra (Figure S3C). The autoxidation of DOPAL is faster than in PBS due to the higher pH used by Anderson et al. (7.8 vs 7.4). As expected, addition of 50 nM SOD effectively inhibited DOPAL autoxidation. However, at higher concentrations of SOD, the rate of DOPAL decay increased, and at the highest SOD concentration measured here (40 μM of the active enzyme, or 80 μM of monomeric SOD), the oxidation rate exceeded the rate of native autoxidation (Figure S3C). We also considered the fact that SOD is known to produce oxygen radicals using hydrogen peroxide as a substrate [30, 31]. This explanation was also discounted, as in reactions with 20 μM SOD, the addition of 500 μM hydrogen peroxide did not accelerate DOPAL oxidation nor did the addition of 1 μM catalase inhibit DOPAL oxidation (data not shown).

SOD has remarkable catalytic efficiency, with a reaction rate towards superoxide that is diffusion limited. Evaluating the role of superoxide in an in vitro system – as done here and elsewhere [22, 23] – requires only minute concentrations of SOD to achieve maximal enzymatic clearance of the superoxide radical. The stimulation of DOPAL oxidation observed at high SOD concentrations likely results from an undescribed secondary SOD activity that competes with the protective effect of superoxide dismutation.

4. Discussion

The role of superoxide as a propagating species in the autoxidation of catechol-bearing compounds is well established [22, 23]. Here, we extend this observation to DOPAL, an obligate intermediate of dopamine catabolism and a highly reactive toxin unique to dopaminergic neurons that crosslinks α-synuclein in those cells. More interestingly, our results make it clear that DOPAL oxidation is a critical driver of its reactivity toward proteins and its ability to covalently crosslink them. This finding explains prior work by Doorn et al. demonstrating that the DOPAL catechol group activates the reactivity of its aldehyde [6], and lends support to the mechanism proposed for the formation of DCPL adducts, in which a critical step is the oxidation of the DOPAL catechol ring to a quinone and isomerization to a quinone methide, in order to activate the aldehyde-adjacent carbon for nucleophilic attack by a second DOPAL molecule [10]. It is also consistent with previous reports that DOPAL reactivity is inhibited by the radical scavenger ascorbate and other antioxidants [6, 27].

Despite increasing amounts of circumstantial evidence linking PD etiology to mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, a direct mechanistic connection to α-synuclein aggregation has proven elusive [32]. Recently, it was reported that certain post-translationally-modified forms of α-synuclein – including small, covalent oligomers – can bind to and disrupt the mitochondrial protein import machinery, causing impaired respiration and inducing oxidative stress [33]. Such a pathway highlights the fact that DOPAL-mediated α-synuclein oligomers could both initiate PD mechanisms and result from them. Given that superoxide is a major product of impaired mitochondrial respiration, our results suggest a possible connection to synuclein oligomerization, mediated by DOPAL and thus specific to dopaminergic neurons, that warrants further study in biological systems.

Supplementary Material

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) inhibits the autoxidation of DOPAL

SOD prevents DOPAL from forming dicatechol pyrrole lysine adducts

SOD inhibits DOPAL-mediated crosslinking of a-synuclein

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Mulvihill (University of Kent) for the NatB acetyltransferase construct, Yunden Jinsmaa and David Goldstein (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke) for helpful discussions and preliminary experimental work, and Sarah Monti (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute) for insightful comments. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Abbreviations

- Ac-Lys

Nα-acetylated lysine

- Ac-WT aS

N-terminally acetylated, wild-type α-synuclein

- DCPL

dicatechol pyrrole lysine

- DOPAL

3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde

- DTPA

diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.4

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Chemical compounds studied in this article 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (PubChem CID: 119219)

References

- 1.Lashuel HA, Overk CR, Oueslati A, Masliah E. The many faces of alpha-synuclein: from structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:38–48. doi: 10.1038/nrn3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winner B, Jappelli R, Maji SK, Desplats PA, Boyer L, Aigner S, Hetzer C, Loher T, Vilar M, Campioni S, Tzitzilonis C, Soragni A, Jessberger S, Mira H, Consiglio A, Pham E, Masliah E, Gage FH, Riek R. In vivo demonstration that alpha-synuclein oligomers are toxic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4194–4199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100976108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein DS, Kopin IJ, Sharabi Y. Catecholamine autotoxicity. Implications for pharmacology and therapeutics of Parkinson disease and related disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;144:268–282. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulzer D, Bogulavsky J, Larsen KE, Behr G, Karatekin E, Kleinman MH, Turro N, Krantz D, Edwards RH, Greene LA, Zecca L. Neuromelanin biosynthesis is driven by excess cytosolic catecholamines not accumulated by synaptic vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11869–11874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke WJ, Li SW, Chung HD, Ruggiero DA, Kristal BS, Johnson EM, Lampe P, Kumar VB, Franko M, Williams EA, Zahm DS. Neurotoxicity of MAO metabolites of catecholamine neurotransmitters: role in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurotoxicology. 2004;25:101–115. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rees JN, Florang VR, Eckert LL, Doorn JA. Protein reactivity of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, a toxic dopamine metabolite, is dependent on both the aldehyde and the catechol. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:1256–1263. doi: 10.1021/tx9000557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rees JN, Florang VR, Anderson DG, Doorn JA. Lipid peroxidation products inhibit dopamine catabolism yielding aberrant levels of a reactive intermediate. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:1536–1542. doi: 10.1021/tx700248y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Negre-Salvayre A, Coatrieux C, Ingueneau C, Salvayre R. Advanced lipid peroxidation end products in oxidative damage to proteins. Potential role in diseases and therapeutic prospects for the inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:6–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson DG, Mariappan SV, Buettner GR, Doorn JA. Oxidation of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, a toxic dopaminergic metabolite, to a semiquinone radical and an orthoquinone. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:26978–26986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.249532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werner-Allen JW, DuMond JF, Levine RL, Bax A. Toxic Dopamine Metabolite DOPAL Forms an Unexpected Dicatechol Pyrrole Adduct with Lysines of alpha-Synuclein. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:7374–7378. doi: 10.1002/anie.201600277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattammal MB, Haring JH, Chung HD, Raghu G, Strong R. An endogenous dopaminergic neurotoxin: implication for Parkinson’s disease. Neurodegeneration. 1995;4:271–281. doi: 10.1016/1055-8330(95)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke WJ, Li SW, Williams EA, Nonneman R, Zahm DS. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde is the toxic dopamine metabolite in vivo: implications for Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Brain Res. 2003;989:205–213. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03354-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein DS, Sullivan P, Cooney A, Jinsmaa Y, Sullivan R, Gross DJ, Holmes C, Kopin IJ, Sharabi Y. Vesicular uptake blockade generates the toxic dopamine metabolite 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde in PC12 cells: relevance to the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2012;123:932–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jinsmaa Y, Sullivan P, Gross D, Cooney A, Sharabi Y, Goldstein DS. Divalent metal ions enhance DOPAL-induced oligomerization of alpha-synuclein. Neurosci Lett. 2014;569:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burke WJ, Kumar VB, Pandey N, Panneton WM, Gan Q, Franko MW, O’Dell M, Li SW, Pan Y, Chung HD, Galvin JE. Aggregation of alpha-synuclein by DOPAL, the monoamine oxidase metabolite of dopamine. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:193–203. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chinta SJ, Andersen JK. Redox imbalance in Parkinson’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1780. 2008:1362–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Betarbet R, Sherer TB, MacKenzie G, Garcia-Osuna M, Panov AV, Greenamyre JT. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1301–1306. doi: 10.1038/81834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langston JW, Ballard P. Parkinsonism induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP): implications for treatment and the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Can J Neurol Sci. 1984;11:160–165. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100046333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fornai F, Schluter OM, Lenzi P, Gesi M, Ruffoli R, Ferrucci M, Lazzeri G, Busceti CL, Pontarelli F, Battaglia G, Pellegrini A, Nicoletti F, Ruggieri S, Paparelli A, Sudhof TC. Parkinson-like syndrome induced by continuous MPTP infusion: convergent roles of the ubiquitin-proteasome system and alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3413–3418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409713102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanner CM, Kamel F, Ross GW, Hoppin JA, Goldman SM, Korell M, Marras C, Bhudhikanok GS, Kasten M, Chade AR, Comyns K, Richards MB, Meng C, Priestley B, Fernandez HH, Cambi F, Umbach DM, Blair A, Sandler DP, Langston JW. Rotenone, paraquat, and Parkinson’s disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:866–872. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCord JM, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein) J Biol Chem. 1969;244:6049–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Misra HP, Fridovich I. The role of superoxide anion in the autoxidation of epinephrine and a simple assay for superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:3170–3175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heikkila RE, Cohen G. 6-Hydroxydopamine: evidence for superoxide radical as an oxidative intermediate. Science. 1973;181:456–457. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4098.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein S, Fridovich I, Czapski G. Kinetic properties of Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase as a function of metal content–order restored. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:937–941. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson M, Coulton AT, Geeves MA, Mulvihill DP. Targeted amino-terminal acetylation of recombinant proteins in E. coli. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masuda M, Dohmae N, Nonaka T, Oikawa T, Hisanaga S, Goedert M, Hasegawa M. Cysteine misincorporation in bacterially expressed human alpha-synuclein. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1775–1779. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Follmer C, Coelho-Cerqueira E, Yatabe-Franco DY, Araujo GD, Pinheiro AS, Domont GB, Eliezer D. Oligomerization and Membrane-binding Properties of Covalent Adducts Formed by the Interaction of alpha-Synuclein with the Toxic Dopamine Metabolite 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL) J Biol Chem. 2015;290:27660–27679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.686584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finkelstein E, Rosen GM, Rauckman EJ, Spin trapping Kinetics of the reaction of superoxide and hydroxyl radicals with nitrones. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1980;102:4994–4999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nandi A, Chatterjee IB. Scavenging of superoxide radical by ascorbic acid. Journal of Biosciences. 1987;11:435–441. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramirez DC, Gomez-Mejiba SE, Corbett JT, Deterding LJ, Tomer KB, Mason RP. Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase-driven free radical modifications: copper- and carbonate radical anion-initiated protein radical chemistry. Biochem J. 2009;417:341–353. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yim MB, Chock PB, Stadtman ER. Copper, zinc superoxide dismutase catalyzes hydroxyl radical production from hydrogen peroxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:5006–5010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaltieri M, Longhena F, Pizzi M, Missale C, Spano P, Bellucci A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and alpha-Synuclein Synaptic Pathology in Parkinson’s Disease: Who’s on First? Parkinsons Dis. 2015;2015:108029. doi: 10.1155/2015/108029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di Maio R, Barrett PJ, Hoffman EK, Barrett CW, Zharikov A, Borah A, Hu X, McCoy J, Chu CT, Burton EA, Hastings TG, Greenamyre JT. alpha-Synuclein binds to TOM20 and inhibits mitochondrial protein import in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:342ra378. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.