Abstract

The combination of cryo-microscopy and electron tomographic reconstruction has allowed us to determine the structure of one of the more complex viruses, intracellular mature vaccinia virus, at a resolution of 4–6 nm. The tomographic reconstruction allows us to dissect the different structural components of the viral particle, avoiding projection artifacts derived from previous microscopic observations. A surface-rendering representation revealed brick-shaped viral particles with slightly rounded edges and dimensions of ≈360 × 270 × 250 nm. The outer layer was consistent with a lipid membrane (5–6 nm thick), below which usually two lateral bodies were found, built up by a heterogeneous material without apparent ordering or repetitive features. The internal core presented an inner cavity with electron dense coils of presumptive DNA–protein complexes, together with areas of very low density. The core was surrounded by two layers comprising an overall thickness of ≈18–19 nm; the inner layer was consistent with a lipid membrane. The outer layer was discontinuous, formed by a periodic palisade built by the side interaction of T-shaped protein spikes that were anchored in the lower membrane and were arranged into small hexagonal crystallites. It was possible to detect a few pore-like structures that communicated the inner side of the core with the region outside the layer built by the T-shaped spike palisade.

Keywords: cryo-EM, virus structure, 3D reconstruction

Vaccinia virus (VV) is the best-characterized member of the Poxviridae family, which contains some of the largest, most complex, most challenging viruses (1). VV has been a classic subject for viral studies, but it has also been developed as an expression vector for foreign genes, as well as a live recombinant vaccine for infectious diseases and cancer (2–5). The detailed structure of the virus particle is only discernible by EM (6), and these studies using multiple approaches have generated a considerable amount of structural data, including conflicting interpretations in working models. A few general ideas are widely accepted: First, intact particles show a remarkable size, measuring some 360 nm in the largest dimension. Second, the shape of the virion departs from the general rounded or helical morphology of many viruses by adopting a brick shape. And, third, there are no evident symmetry elements in any part of the complex assembly.

The life cycle of VV consists of a number of steps that occur in the cytoplasm of the infected cell: virion entry, core release and early transcription, DNA replication, and virus assembly and release (1). When VV infects a susceptible cell, it induces 1 h postinfection the formation of a “viral factory,” a large cytoplasmic perinuclear structure where viral factors recruit and create complex interactions with cellular elements to build the replication complexes and assembly sites (7). Once genome replication is completed, assembly of VV particles occurs through a series of intermediate structures that result in the assembly of two different infectious viral forms (8). The spherical immature virus (IV), which forms from modified membranes (known as crescents) and the genomic DNA, matures into a brick-shaped structure in a process that involves a drastic reorganization and the proteolytic cleavage of several core proteins and the formation of disulfide bonds as key elements for a stable structure (9). A fraction of intracellular mature VV (IMV) becomes further enveloped by a double membrane derived from the trans-Golgi network or early tubular endosomes (10, 11) to form intracellular enveloped viruses. An important controversy has traditionally surrounded the origin and number of membranes that form VV crescents and IVs (12, 13). The initial idea of a de novo synthesis of a single, primary VV membrane (13–15) has been recently disfavored. Several studies support the proposal that the VV primary envelope would be a double membrane originated from tubular membranous elements of the secretory pathway, in particular the endoplasmic reticulum–Golgi intermediate compartment (16–18), or directly derived from the endoplasmic reticulum (19).

One of the origins of the controversial interpretation of the VV structure arises from the use of different preparation techniques. In this context, the most interesting approaches to avoid possible artifacts derived from sample preparation are cryo-hydrated methods. Cryo-preparation of VV dates back to 1994, with the work of Dubochet et al. (20). Their work revealed that virions appeared uniform, and the resulting model consisted of two layers: a regular internal palisade and a core containing the viral DNA.

Other subsequent studies, such as those by Roos et al. (21) and Griffiths et al. (22, 23), applied different sample preparation and visualization techniques, including immune labeling procedures (24). These contributions led to the proposal of models speculating on how subsequent assembly intermediates could be reflected in the final virion. Nevertheless, a number of questions remained open: (i) Are the varieties of shapes and the discrete transient features frequently reported genuine parts of intact virions? (ii) Is VV a stable assembly, or is it partially pleomorphic and prone to disruption under unfavorable conditions? (iii) How are the structural transitions of the viral particle during morphogenesis accommodated by these structural models?

In the present study, we have combined the advantages of cryo-preservation applied to the isolated IMV particles with those of 3D visualization using electron tomography. This method unambiguously reveals that the virus particle shows a homogeneous profile that fits well those models previously proposed in terms of size, shape, and lack of symmetry. The detailed virus structure appeared complex; it included two membranes, the presence of conspicuous lateral densities, a palisade layer with paracrystalline patches of spikes, some cavities separating both membranes, and the DNA condensed on fibers near the inner walls or the core. We also detected pore-like formations spanning through the viral core membrane, which could be responsible for the export of newly transcribed RNA to the cytoplasm in the early stages of infection.

Materials and Methods

Virus Preparation. VV strain Western Reserve was propagated in HeLa cells and titrated in BSC-40 cells. Purification of viral particles (IMVs) was performed by banding through 20%–45% sucrose gradients as described in ref. 25.

Sample Preparation for EM. VV wild-type strain (Western Reserve) was prepared for cryo-EM by rapid freezing in liquid ethane slush at a temperature of approximately –180°C, according to standard procedure (26) with small modifications. Briefly, an aliquot of 3 μl of the specimen, with a virus concentration of ≈5 × 108 virions per ml, was introduced on Quantifoil 2/2 (Quantifoil, Jena, Germany) and homemade holey EM grids, together with a similar aliquot of 10 nm of protein A-colloidal gold (Sigma), and incubated on the grid for 40–60 s. The grids were frozen and observed by using a CM300 electron microscope (FEI, Eindhoven, Germany) that was equipped with a field emission gun and post column energy filter (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA) and operated in the zero-loss mode (27) at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV. The tomographic tilt series was recorded in various conditions. The basic setup for the series was as follows (the deviations from the standard setup are shown in brackets): nominal magnification (position screen down), 14 kx = 0.82 nm/pixel [also 23 kx = 0.68 nm/pixel]; defocus, 8 μm [also 14 μm]; angular range covered, 120°–140°; increment, 2° [also 1.5°]; number of images per series, 60–96; scheme, linear [also Saxton]; illumination, 0.3–0.5 electrons per Å2 per image = 25–35 electrons per Å2 for the series; thickness of water film, 250–400 nm.

Reconstruction. From the recorded data sets, eight were selected, and the tomograms were computed by the means of the weighted back-projection method (28, 29) by using gold particles as fiducial markers. For the final analyses, both the single and double binning factors were applied to the tomograms, resulting in voxel sizes of 1.64 and 3.28 nm for the 14-kx data sets and 1.36 and 2.72 nm for the 23-kx data sets. The reconstructions and part of further processing were carried out by using the em image processing package (Max Planck Institute) (30). From the resulting tomograms, >30 particles were extracted, covering different orientations in relation to the beam and tilt axes.

Denoising and Segmentation of IMV Tomograms. Reconstructed IMV tomograms contained substantial noise. Denoising was then necessary to discern and interpret structural features. A combination of Gaussian filtering (31) and anisotropic nonlinear diffusion (AND) (32, 33) was used in this work. (For details, see the supporting information, which is published on the PNAS web site.) In Gaussian filtering, the standard deviation of the Gaussian function was set to 1.0. With regard to AND, the diffusion modes known as EED (edge-enhancing diffusion) and CED (coherence enhancement diffusion) were tightly coupled as described in ref. 33. The values of the parameters for CED and EED modes were C = 4 and K = 2, respectively; a local scale of σ = 2 was used in the CED mode, and five diffusion iterations were conducted. The masks were generated from the AND-denoised tomograms by means of threshold-based binary segmentation followed by a flooding algorithm to select connected areas and, finally, three cycles of morphological dilation operation (see detailed description in the supporting information).

Objective determination of a density threshold was required at several stages: masking, interpretation, and visualization of tomograms. An algorithm for optimal thresholding (31) was implemented in this work (see supporting information). This method assumes that the histograms of the foreground and background in tomograms follow Gaussian distributions. The optimal threshold is computed as the density value that maximizes the variance between those distributions.

Interpretation of the Tomograms and Data Analysis. Visualization of the filtered and masked tomogram was finally done by using amira (TGS Europe, Merignac, France). The volumes dissected from the tomograms were analyzed by following several approaches.

For the density measurements within the subsequent layers of the virion, small subvolumes comprising ≈1,000 voxels each were extracted. Usually, 10–12 subvolumes were selected from each of the following layers in the virus: the outer and inner membranes (side views), lateral bodies, palisade layer at side and top views, nucleoproteins, and the electron translucent (void) space within the core. The averaged densities of each layer were presented normalized to the density in the background, measured in frozen buffer in the vicinity of the viruses.

The palisade layer containing the spikes was analyzed for the shape and distribution of the crystalline arrangements by using the crosscorrelation procedure. A number of small insets dissected from the top views of the palisade, containing, on average, 18 spikes each, were merged into an averaged volume. This volume resulted in the first reference, with which the entire volume of the virus was scanned, resulting in a crosscorrelation pattern showing the positions with the best fit to the hexagonal arrangement that were improved by iteration.

Results

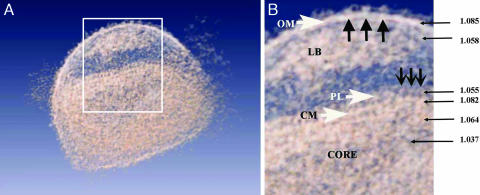

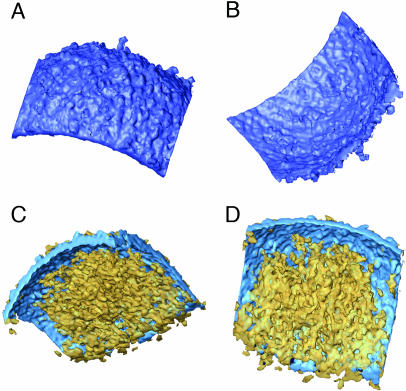

Tomographic Reconstruction of IMVs. Purified IMV were rapidly frozen and observed by cryo-EM. Typical images revealed an apparent heterogeneity in shape (dimensions of ≈200–360 nm in different directions). Brick-shaped viral particles with an internal core were clearly distinguished (Fig. 1A). Tilt series were obtained by using energy filtering to remove the inelastically scattered electrons (see Materials and Methods). From the different tomographic series, eight were selected, based on their overall quality, for further processing. Direct visualization of the sections from the 3D reconstructed tomograms (Fig. 1B) revealed a consistent morphology, based on several layers enclosing an internal core with a lower density area in the inner region (Fig. 1C). Surface-rendering representation revealed viral particles with a surprising homogeneous morphology, with an overall shape of a barrel slightly compressed along the longitudinal axes and dimensions of ≈350–370 × 250 × 270 nm. The outer surface of the viral particles presented a moderated corrugation (Fig. 2 A and B), with features consistent with protrusions of irregular shape extending ≈3–5 nm from the viral surface. No special ordering of these corrugations was found in any of the reconstructions. Translucent visualization of the reconstructed volume allowed us to recognize those features described previously using thin sections of fixed material as the dumbbell-shaped core (Fig. 2C; compare with Fig. 1C). Nevertheless, the availability of the whole reconstructed volume showed that this shape evolves, at different viewing angles, to a more continuous outline closely following the outer surface of the virion (Fig. 2 C and D).

Fig. 1.

Isolated VV particles (IMV) preserved by rapid freezing and viewed by cryo-EM. (A) Cryo-electron micrograph. A typical projection image comprising several particles at different orientations is shown. (B) An x–y section through the tomographic reconstruction of the same area in A. (C) One of the particles depicted in four subsequent x–y sections; each section is 24 nm thick and 24 nm apart from each other (no denoising procedure was applied). (Scale bar: 200 nm.)

Fig. 2.

Volumetric representation of the reconstructed viral particles. (A and B) Surface rendering highlighting the outer shape and size of the virion. Two orthogonal views along perpendicular axes are shown. (C and D) Translucent representation of the reconstructed virion showing the complex internal structure of the core. The dumbbell-shaped core as seen in one orientation (C) evolves to a morphology that closely follows the outer membrane (D). x, y, and z axes are shown to facilitate identification of the spatial orientation of the respective views.

General Architecture of IMV. The tomograms of such large, multicomponent assemblies as VV particles are difficult to interpret because of their inherent structural complexity, which is further obscured by noise derived from the data acquisition procedures. Therefore, denoising is required to increase the signal-to-noise ratio up to a point that segmentation of consistent structural features can be obtained. We have applied a combination of Gaussian filtering and anisotropic nonlinear diffusion to take advantage of these methods' best properties (see Materials and Methods and supporting information). Tomograms filtered by following the scheme described above were more easily interpretable because of the removal of the noise (Fig. 3A). Features barely visible in raw tomograms were now evident, revealing a consistent structure of the IMV particles (Fig. 3B): an outer layer consisting of a membrane with protrusions, the volumes below the membrane filled with aggregates of heterogeneous material (previously described as “lateral bodies”), and a complex core composed of two distinct layers enclosing dense areas containing fibrous material and an inner region with lower density.

Fig. 3.

General overview of the virus in a translucent model. (A) Section through a denoised and surface-rendered virion showing all of the virus structural elements described in the text. The boxed area is enlarged in B. (B) Schematic view of major domains: ruffles (large black arrows) on the outer membrane (OM), lateral bodies (LB), repeating units (small black arrows) in the palisade (PL), and core membrane (CM). The numbers indicate the relative density values of the corresponding regions marked by the arrows.

The outer layer of the virions was fully consistent with a lipidic membrane (5–6 nm thick, with an average density of 1.085; for a definition, see Materials and Methods), but the surfaces of this membrane are different at both sides. The outer surface exhibited higher corrugations (Fig. 4A) due to the nonperiodic presence of extensions (3–5 nm high) that were consistent with integral protein extensions, probably corresponding to the outer receptor-binding viral components. The inner side of the outer membrane was smoother and revealed neither any extension nor apparent holes (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Outer membrane and lateral bodies; denoised and surface-rendered views of the outer membrane fragments (blue) are shown. (A and B) Outer, rough aspect (A) and inner, smooth surface (B). (C and D) Lateral bodies (yellow) attached to the inner side of the outer membrane.

A fairly conspicuous feature found in almost all of the reconstructed particles was the presence of one or, most frequently, two lateral bodies built up by a heterogeneous material without apparent ordering or repetitive features (Fig. 4 C and D). These lateral densities have close contact with the core (as analyzed on the sections through the reconstructions (Fig. 1 B and C). However, in the rare cases when the outer membrane swells and detaches from the core, the lateral densities always remain attached to the outer membrane (Fig. 3).

The internal core revealed a complex architecture (Figs. 1, 2, 3). It was composed of two layers, with an overall thickness of ≈18–19 nm. The inner layer was continuous, and it was consistent with a lipidic membrane both in thickness (5–6 nm) and in its general continuous aspect (average density of 1.082 arbitrary units, similar to the value found for the outer viral membrane). The core outer layer was discontinuous (average density of 1.055, arbitrary units) and presented periodicities that fit to the existence of a periodic palisade that connected the inner with the outer layer (Fig. 3 A and B). The more likely interpretation of this assembly is that the outer, discontinuous core layer is built by the side interaction of T-shaped protein spikes (8 nm in length and 5 nm wide) that are anchored in the lower membrane.

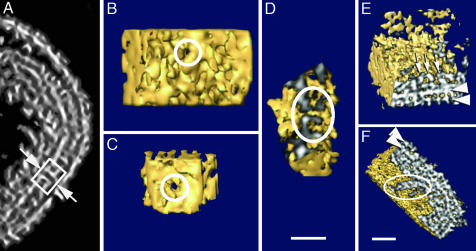

To determine more precisely the arrangement of the spikes in the palisade layer, we used an extensive crosscorrelations search for the hexagonally arranged lattices (Fig. 5). As a reference, we used several small inserts of the spikes (Fig. 5B) averaged into a common volume. This reference was scanned throughout the entire volume of the reconstructed virion. The resulting maps are visible in Fig. 5C as a top view of one reconstructed face of the viral core. The hexagonal patches varied slightly in size and shape and usually comprised 15–24 spikes (18 spikes on average). The patches were randomly oriented in the plane of the core, laterally interconnected to each other, and occupied some 75–80% of the core surface, irrespective of the arrangement and presence of the covering spikes. The areas between the hexagonal patches appeared free also of individual spikes, and the core membrane that underlies the spikes seemed to be intact and continuous.

Fig. 5.

The spikes and palisade layer at the outer surface of the virus core. (A) An x–y section through the reconstruction cutting through the front view of the palisade layer. (B) Small area containing several spikes' crystallites in top view that, after averaging and symmetrizing, generated the reference for a crosscorrelation search, together with the corresponding diffraction pattern. (C) A top view through the correlation map showing distribution of the spikes and small crystallites. The correlation peaks are bright (high crosscorrelation values) and correspond to the electron densities of spikes seen as black in A and B.

Systematic analysis of the tomographic volumes also revealed unexpected features in the presumptive lipidic membrane of the core: Within otherwise intact and continuous membranes, a small number of channel-like formations were detected, revealing a consistent morphology (Fig. 6). In five different tomograms, we found between two and six pores per virion, although, at this resolution, we might be missing some others because of their difficult identification. Sections showing side views of representative pores reveal that they span both the inner membrane and the palisade layer, and they clearly interconnect the lumen of the core with the volume ensuing between viral membranes (Fig. 6A). The lumen within all detected pores appeared fully open, regardless of whether they were viewed toward the inside of the virion (i.e., at the side of the palisade; Fig. 6B) or viewed toward the outside, from the core lumen (Fig. 6C). On the sections perpendicular to the membrane (Fig. 6D), we measured the average diameter of the channel to be ≈7 nm, surrounded by a rigid, cylindrical, or spool-like structure 6–7 nm in thickness, with an outer diameter of ≈20 nm.

Fig. 6.

Pores in the inner membrane and core morphology. (A) Section through a representative denoised tomogram that cuts through the pore in the inner membrane (arrows); the box encircles the entire structure. (B and C) Surface-rendered volumes of the pores along the lumen axes (circles), as viewed from outside and inside the virus core, respectively. (D) A side section of the pore (circle) as visualized in the surface-rendered tomogram. (E and F) Different sections of a 3D core reconstructed area. The sectioned surfaces have been shadowed to highlight the features of the palisade and the membrane (arrowheads), as well as the threaded fibers (white arrows in A and outlined in B). (Scale bars: 50 nm.)

The material filling the space inside the core separated into two distinct phases (Figs. 1C and 2C). The denser fraction, which condensed just below the membrane, had an average density of ≈1.064 (Fig. 6E) and eventually exhibited a fiber-like morphology, but without any detectable periodicity (Fig. 6F). These curly condensations at the inner facet of the core probably represent the presumptive nucleoprotein complexes of the virion, suggesting the ordered compaction of this material. Although the aggregates found in this region were closely apposed to the core membrane, there were no consistent connections between the fibers and either the membrane or the pores. The remaining volume within the core was filled with the material with much lower relative density, on average 1.037 arbitrary units. Because the viral particles were preserved by rapid freezing, it is fairly unlikely that such separation of phases would be the result of artifactual precipitation and exclusion of core material; more likely, the separation of phases represents distinct regions of the core.

Discussion

Cryo-electron tomography has proven its power in gaining unique views into large biological structures that lack any obvious symmetry (reviewed in ref. 34). It is particularly suited for studying the arrangements with a complexity ranging up to that of the parts of intact cells (35); it is also a powerful method toward completing the visualization of macromolecular assemblies that have already been partially characterized by using either the established EM methods or x-ray crystallography, as demonstrated with the recently reported 3D structure study on the herpes simplex virus (36).

The combination of cryo-microscopy and electron tomographic reconstruction of such a complex virus as VV allows us to settle decades of disputes on the eventual genuine character of a number of morphological features described over the years. The most prominent features derived from the tomographic reconstructions are a uniform size and shape of the particles, comprising a brick-shaped structure with the fixed dimensions of 360 × 270 × 250 nm, the presence of two membranes, lateral densities at both sides of the dumbbell core (whose membrane has a palisade composed of a layer of spikes), and electron-dense aggregations of DNA within the core. The apparent discrepancy found in the abundant literature reporting the shape of the cores from rounded to dumbbell-shaped (14, 20, 21) is explained by following the 3D volume of the reconstructed core (Figs. 1 and 2). Depending on the point of view, it offers profiles corresponding to the reported 2D projections, thus correlating those variations to the different section planes through the virions, as suggested in ref. 37.

Although the issue of the existence of one or two membranes in IMVs is fundamental in understanding VV morphogenesis and entry in cells (38), a conclusive compromise has never been achieved. Analysis of all reconstructed particles in our tomograms supports the presence of two membranes, as postulated in recent studies (18, 22, 23). The outer viral membrane envelops the entire virion and presents a rough appearance on the outer side. Nevertheless, it does not show any additional structural features, such as tubules or grooves. The inner viral membrane outlines the boundaries of the core, and it is partially decorated with the palisade of spikes. Although cryo-preserved samples studied by Dubochet et al. (20) revealed the hexagonal packing of the palisade spikes in projection, our reconstructions provide the distribution of the small crystalline patches corresponding with the clear side views of the palisade layer in the single projections.

In recent years, we have gained some knowledge about the first steps of VV infection (39, 40). Many lines of evidence indicate that VV completely uncoats the outer membrane before getting internalized into the cytoplasm (23, 41) and that the virus enters the cell through a virus–cell fusion event (42, 43). The existence of two membranes in IMVs was conceptually disfavored because it would represent the release of a “coated, enveloped” viral particle into the cytoplasm, instead of a naked, functional core (13). However, our data indicate that the IMV inner core wall is, in fact, a deeply modified membrane, and the presence of open pores in this layer makes it possible that the internal content of the core would be in direct contact with the cytoplasm early in infection.

The existence of some kind of fenestration(s) in the VV core wall was postulated in previous studies that focused on the early viral RNA transcription, demonstrated to happen within apparently completely encapsulated cores (44). It was also possible to reconstitute the early transcription in vitro with apparently intact cores after depletion of the outer membrane (45, 46). The 3D tomographic reconstruction of frozen, hydrated VV presented here clearly shows pore-like formations in the intact cores. The pores appear uniform in shape and size, with a lumen diameter of 7 nm. These pore-like structures could therefore be directly involved in the mRNA extrusion into the cytoplasm of infected cells.

In the tomographic reconstructions, the contents of the core separate in two phases. The denser phase shows threaded fibers distributed unevenly that most probably correspond to protein–DNA complexes. The genome of wild-type VV consists of ≈190 kb, which is slightly larger than the genome of the herpes simplex virus (152 kb). However, the volume available within the VV core is ≈20 times bigger than that available within the herpes core. Thus, it seems likely that VV DNA concentrates near the core wall, whereas the lower density volume is free of DNA and occupied by some other material, presumably soluble enzymes and factors that very likely stay beyond the resolution of our tomographic reconstructions.

Finally, the lateral densities below the viral outer membrane, largely assigned to fixation or staining artifacts, appear as a clear, consistent feature in the space between the outer membrane and the core. Normally, two of these peculiar assemblies coexist in each virion, and it is tempting to speculate that these are special areas for the storage of viral components required for the infection process.

A principal enquiry regarding the resolution in resulting tomograms is difficult to assess by standard methods, which have been developed mainly for “single-particle” approaches (36). Moreover, unlike the researchers in the cited study with herpes simplex virus, we are lacking any substructure in the virion that might serve as a reference for resolution assessment. The Fourier analysis of the 8-nm spikes arranged in small hexagonal arrays generate structure factor intensities at a resolution just beyond 5 nm (Fig. 5). We maintain that neither the imaging conditions nor the alignment and reconstruction protocols would limit the resolution up to 5 nm, and when the averaging between any unordered elements is attempted, we may expect visualization of details with at least such resolution.

In addition to allowing the study of structural changes produced during VV maturation, we also believe cryo-electron tomography can enable researchers to gain 3D views into thin layers of infected cells that would allow the study of different steps of the vaccinia life cycle.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Friedrich Förster for help with the template matching procedures. This work was supported by Grants BMC2002-00996 (to J.L.C.), BIO2001-2269 and QLK2-CT-2002-01867 (to M.E.), BMC2003-01630 and CAM07B/0039/2002 (to C.R.), and TIC2002-00228 and HFSP2003-ST00107 (to J.J.F.). We acknowledge the support of EU Contract LSHG-CT-2004-502828.

Abbreviations: VV, vaccinia virus; IMV, intracellular mature VV.

References

- 1.Moss, B. (2001) Fields Virology (Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins, Philadelphia).

- 2.Panicali, D. & Paoletti, E. (1982) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79, 4927–4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackett, M., Smith, G. L. & Moss, B. (1992) Biotechnology 24, 495–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moss, B. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 11341–11348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwack, H., Harig, H. & Kaufman, H. Z. (2003) Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 6, 161–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker, T. S. & Johnson, J. E. (1997) Structural Biology of Viruses (Oxford Univ. Press, New York).

- 7.Cairns, J. (1960) Virology 11, 603–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Payne, L. G. & Norrby, E. (1978) J. Virol. 27, 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senkevich, T. G., White, C. L., Koonin, E. V. & Moss, B. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 12068–12073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tooze, J., Hollinshead, M., Reis, B., Radsak, K. & Kern, H. (1993) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 60, 163–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmelz, M., Sodelk, B., Ericsson, M., Wolffe, J., Shida, H., Hiller, G. & Griffiths, G. (1994) J. Virol. 68, 130–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krinjse-Locker, J., Scheleich, S., Rodriguez, D., Goud, B., Snijder, E. J. & Griffiths, G. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 14950–14958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hollinshead, M., Vanderplasschen, A., Smith, G. L. & Vaux, D. J. (1999) J. Virol. 73, 1503–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dales, S. (1963) J. Cell Biol. 18, 51–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dales, S. & Mosbach, E. H. (1968) Virology 35, 564–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sodeik, B., Doms, R. W., Ericsson, M., Hiller, G., Machamer, C. E., van't Hof, W., van Meer, G., Moss, B. & Griffiths, G. (1993) J. Cell Biol. 121, 521–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez, J. R., Risco, C., Carrascosa, J. L., Esteban, M. & Rodriguez, D. (1997) J. Virol. 71, 1821–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Risco, C., Rodríguez, J. R., López-Iglesias, C., Carrascosa, J. L., Esteban, M. & Rodríguez, D. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 1839–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Husain, M. & Moss, B. (2003) J. Virol. 77, 11754–11766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubochet, J., Adrian, M., Richter, K., Garces, J. & Wittek, R. (1994) J. Virol. 68, 1935–1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roos, N., Cyrklaff, M., Cudmore, S., Blasco, R., Krijnse-Locker, J. & Griffiths, G. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 2343–2355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffiths, G., Wepf, R., Wendt, T., Locker, J. K., Cyrklaff, M. & Roos, N. (2001) J. Virol. 75, 11034–11055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffiths, G., Roos, N., Schleich, S. & Locker, J. K. (2001) J. Virol. 75, 11056–11070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cyrklaff, M., Roos, N., Gross, H. & Dubochet, J. (1994) J. Microsc. (Oxford) 175, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esteban, M. (1984) Virology 133, 220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adrian, M., Dubochet, J. Lepault, J. & McDowall, A. W. (1984) Nature 308, 32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Jong, A. F., Rees, J., Busing, W. M. & Lücken, U. (1996) Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 65, 194–194. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoppe, W. & Hegerl, R. (1980) Topics in Current Physics: Computer Processing of Electron Microscope Images (Springer, Berlin).

- 29.Radermacher, M. (1992) Electron Tomography: Three-Dimensional Imaging with the Transmission Electron Microscope (Plenum, New York).

- 30.Hegerl, R. (1996) J. Struct. Biol. 116, 30–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sonka, M., Hlavac, V. & Boyle, R. (1999) Image Processing, Analysis, and Machine Vision (PWS, Pacific Grove, CA).

- 32.Frangakis, A. S. & Hegerl, R. (2001) J. Struct. Biol. 135, 239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fernandez, J. J. & Li, S. (2003) J. Struct. Biol. 144, 152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baumeister, W. (2002) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12, 679–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Medalia, O., Weber, I., Frangakis, A. S., Nicastro, D., Gerisch, G. & Baumeister W. (2002) Science 298, 1209–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grünewald, K., Desai, P., Winkler, D. C., Heymann, J. B., Belnap, D., Baumeister, W. & Steven, A. C. (2003) Science 302, 1396–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peters, D. (1956) Nature 4548, 1453–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith, G. L., Vanderplasschen, A. & Law, M. (2002) J. Gen. Virol. 83, 2915–2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pedersen, K., Snijder E. J., Schleich S., Roos N., Griffiths G. & Locker J. K. (2000) J. Virol. 74, 3525–3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mallardo, M., Leithe, E., Schleich, S., Roos, N., Doglio, L. & Krijnse-Locker, J. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 5167–5183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holowczak, J. A. (1972) Virology 50, 216–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Armstrong, J. A., Metz, D. H. & Young, M. R. (1973) J. Gen. Virol. 21, 533–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Janeczko, R. A., Rodriguez, J. F. & Esteban, M. (1987) Arch. Virol. 92, 135–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mallardo, M., Schleich, S. & Krijnse-Locker, J. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 3875–3891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kates, J. & Beeson, J. (1970) J. Mol. Biol. 50, 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pelham, H. R. B., Sykes, J. M. M. & Hunt, T. (1978) Eur. J. Biochem. 82, 199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.